Tariq Ali's Blog, page 3

July 7, 2016

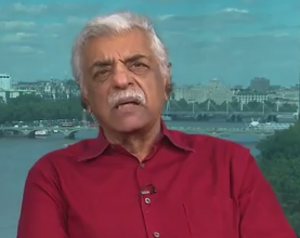

Capitalism will collapse because banks & political elite ‘allow poor to rot’

“The elites who have run the United States and western Europe have proven incapable of offering even the smallest palliatives to their populations. They have allowed the poor to rot ? regardless of skin color ? and grow,” Ali said. “And so what we have is a protest against this center elite, which I call the extreme center because whether it’s social democratic or conservative, they unite to crush.”

Presumptive Republican nominee Donald Trump has become a perfect example of this protest against the extreme center, he tells Hedges.

“They’ve found in Trump someone who airs their most crazed fantasies at the same time who attacks the banks, at the same time attacks these new treaties which are being carried through and promises some palliatives to the poorest section of the white working class,” Ali said.

The right and the far right are growing around the world, while the left has been weak. That is part of the reason that Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders wasn’t able to succeed, even though he also offers an independent voice to the working class.

“I don’t think that there’s anything on the radical left at the moment ? of course, these things are volatile, things can happen,” he said.

Ali cited an appeal that actress Rosario Dawson made to Sanders supporters as to why Trump is so popular at a widely attended rally in New York City at the end of March.

Both Hedges and him think that capitalism is heading towards a collapse and the banks and political elites are doing everything they can to stop it. An example of what they are willing to do to keep the status quo is what happened in the European Union when Greece was on the brink of default.

“Greece is kind of the perfect case study of the myopic thinking on the part of international elites, where they are squeezing everything they can out of this country, knowing full well that it’s ultimately not sustainable,” Hedges said in his first episode of ‘On Contact’ on RT America. “A lot of people in Greece are suffering, and a lot more are going to suffer.”

“They will, yeah,” Ali responded, adding that poor people in Greece were already suffering.

“The figures coming out of Greece were horrific: malnutrition in Greece, people dying for lack of food, people using barter to survive, pensions going down and down and down ? in a poor country,” Ali said. “At the same time as the ship owners, a plutocracy which has owned that country, carries on ? there’s no problems, as far as they’re concerned at all. They don’t pay taxes, they register their ship somewhere else, and even when they don’t, they don’t think it’s their duty.”

Hedges asked if Greece was destroyed to make an example of it, comparable to what then Secretary of State Henry Kissinger did to Chile and Salvador Allende during the Cold War: “The banking system has to destroy Greece … to send a message to countries like Portugal, Spain, Ireland, whose economy is a mess, which is don’t try this,” the RT America host said.

Ali agreed with the analogy.

“This was a message to other countries where there is no armed struggle, no guerrilla warfare: ‘Don’t try coming to power like this and nationalizing industries and rapping us on the knuckles [because] this is how we’ll deal with you’,” he said. “That is what was done to Greece by the European Union and, you know, one has to be honest here… it’s had its effect. It’s pushed people back. The Spanish radical group Podemos stepped backwards. And so it’s had its effect.”

The journalist and author warned that the collapse is coming because the elite refuses to plan for the future.

“They do know that collapse is coming, and they’re trying to make sure that it doesn’t affect them. So the German banks are not prepared to allow the politicians to take any risks by bailing out Greece or bailing out other countries in trouble,” Ali said. “It was one thing bailing themselves out, the banks and the hedge fund system via the banks, but anything else, they say, is unacceptable because it will bring the collapse closer and our interest is to defend the banking system. It’s short-sighted, and they live for today as we know; capitalism and capitalists, by and large, don’t think of the long-term.”

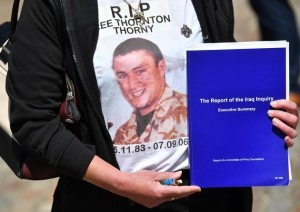

“Time for action, I think…” On Chilcot and the Establishment

If you read the FT editorial today its very clear. Chilcot has redeemed the British Establishment. They have washed their hands clean and removed the blood stains. True, but the bloodshed in Iraq requires justice. The Americans banned the Iraqi Heathy Ministry from counting the Iraqi dead. That was an official decision by the gang-leaders of the Occupation.

The West will never try its own in any court, but at the very least Blair should be treated like a pariah all over the world. And the demand for a trial should be accelerated and globalised. His badly-ghosted books transferred by activists to the Crime section of Waterstones. As for Ann Clwyd she is beneath contempt. The death of a million or so Iraqis doesn’t bother her too much. Why doesn’t she demand NATO bombing of Turkey that has been far more brutal to the Kurds than Saddam. They were never denied their language and schools in Iraq! They are still being killed today. What is Clwyd doing? Justifying her past just like her Dear Leader. These are people without shame. Arab lives mean nothing to them. Blair was, of course, on the ‘international community’s’ payroll for reading out Mossad press releases in Jerusalem as a sop for not being in Downing Street. Blood money…. It was precisely to break from the Iraq syndrome that Cameron sent British bombers to Syria . They were not needed and have barely done anything, thank God, but it was a manouevre to make future wars easier. The Blairites led by Benn voted for this atrocity, but the only war they will ever fight is against Corbyn. Time for action, I think…

Tariq Ali on the Chilcot Report

Tariq Ali on Donald Trump’s Claim “I Alone Can Solve” Rise in Islamic Militancy

May 11, 2016

Il partito laburista salvato dai ragazzi

l termine inglese firebrand (agitatore) sembra essere stato coniato per Tariq Ali. Classe 1943, da studente sosteneva contraddittori con Henry Kissinger, ispirava canzoni ormai classiche agli Stones e John Lennon, diventava confidente di Malcom X, e potremmo continuare. Da leader del ’68 – all’epoca in forza a un trotzkismo permanentemente rivoluzionario – è poi diventato un intellettuale pubblico, tra i fondatori della New Left e autore di una ventina di libri fra saggi, drammi, romanzi. Il fatto che poi, in Gran Bretagna – terra degli empiristi pragmatici per eccellenza – la parola «intellettuale» sia vista con sospetto trova conferma nel suo essere pakistano di nascita. Al suo libro dell’anno scorso, The Extreme Centre, requisitoria politica di un partito laburista stretto in un patto scellerato col grande business, ha appena fatto seguito una lunga analisi del fenomeno Jeremy Corbyn sulla London Review of Books. Nella sua casa di Highgate, non lontano da dove è sepolto Marx, parliamo di Corbyn, di Brexit, di socialdemocrazia europea e del nuovo sindaco laburista della capitale, Sadiq Khan.

l termine inglese firebrand (agitatore) sembra essere stato coniato per Tariq Ali. Classe 1943, da studente sosteneva contraddittori con Henry Kissinger, ispirava canzoni ormai classiche agli Stones e John Lennon, diventava confidente di Malcom X, e potremmo continuare. Da leader del ’68 – all’epoca in forza a un trotzkismo permanentemente rivoluzionario – è poi diventato un intellettuale pubblico, tra i fondatori della New Left e autore di una ventina di libri fra saggi, drammi, romanzi. Il fatto che poi, in Gran Bretagna – terra degli empiristi pragmatici per eccellenza – la parola «intellettuale» sia vista con sospetto trova conferma nel suo essere pakistano di nascita. Al suo libro dell’anno scorso, The Extreme Centre, requisitoria politica di un partito laburista stretto in un patto scellerato col grande business, ha appena fatto seguito una lunga analisi del fenomeno Jeremy Corbyn sulla London Review of Books. Nella sua casa di Highgate, non lontano da dove è sepolto Marx, parliamo di Corbyn, di Brexit, di socialdemocrazia europea e del nuovo sindaco laburista della capitale, Sadiq Khan.

Mr Ali, l’elezione di Sadiq Khan a sindaco di Londra ha strappato applausi a scena aperta nelle tribune liberal.

L’elezione di un sindaco musulmano a Londra, figlio di un autista d’autobus di prima generazione, ha attirato molta attenzione. Hillary Clinton ne è entusiasta, e così Manuel Valls. La ragione è che Khan è un blairiano e profondamente ostile a Corbyn. I tories gli hanno mosso una campagna cattiva e razzista che si è tra- sformata in un sensazionale boomerang. L’ex presidente del partito conservatore, la baronessa Warsi (anche lei figlia di un immigrato pakistano autista d’autobus) l’ha criticata duramente. L’attuale mini- stro conservatore per il commercio (Sajid Javid, ndr) è anche lui figlio di un autista d’autobus pakistano. Le origini di classe non influenzano automaticamente la politica. E Khan è già diventato il portabandiera della destra Labour.

E invece l’elezione del compagno Corbyn chi se la sarebbe mai aspettata? È stato un modo per il Labour per disintos- sicarsi da Tony Blair?

Nessuno naturalmente, tantomeno lui. La prima volta che lo incontrai dopo la sua elezione mi abbracciò e mi disse: “Ma tu avresti mai immaginato che un giorno sarei diventato il leader del partito laburista?” Risposi di no. E lui: “Nemmeno io!” Non avevamo considerato non tanto la rabbia dei giovani, quanto il desiderio di sentire qualcuno nel partito laburista che parlasse per loro. Nel mondo anglofono si è creato questo fenomeno: Corbyn in Gran Bretagna e Sanders negli Stati uniti, sessantenni che attraggono più giovani degli altrettanto giovani e telegenici candidati ufficiali dei rispettivi partiti. Ero convinto che Blair avesse il partito ancora completamente sotto controllo. Invece, importare l’americanata delle primarie pensando di attirare i moderati ha provocato esattamente il contrario. 200.000 nuovi iscritti al partito laburista sono una cosa assolutamente stupefacente. La cosa eccezionale avere il leader più a sinistra del partito in un momento storico in cui delle politiche modestamente socialdemocratiche sono considerate poco meno che delle eccentricità. Tutto dipende dalla mobilitazione giovanile qui, in America e in tutta Europa. Mi chiedo che cosa aspet- tino i giovani francesi e italiani a mobilitarsi quando la loro vita è un chiaro prodotto della crisi e dell’assoluta incapacità dei loro leader di risolverla.

È la prima volta in tempi recenti che un partito socialdemocratico ha vissuto il rivolgimento di un grosso movimento politico e sociale che vi fluisce trasformandolo dall’interno.

Qualcosa che non è successo in nessun’altra parte d’Europa. In Italia c’è il Movimento Cinque Stelle, in Grecia c’è Syriza che è implosa, in Spagna vedremo cosa succede con Podemos, in Germania Die Linke, in Scandinavia vari altri partiti. E dall’altra parte c’è soltanto un’estrema destra che continua a rafforzarsi, mentre qui è stata fino adesso debole: a parte il fenomeno Ukip, che è diverso da Le Pen: sono soprattutto conservatori di destra scontenti e lettori del Daily Mail.

Non sono stati recepiti i segnali del referendum scozzese di due anni fa, quando il 55% votò No all’indipendenza?

Il terremoto politico scozzese ha avuto un effetto notevolissimo qui in Inghilterra, dovuto alla totale mancanza di un’alternativa politica mainstream. Nessuno è stato capace di riconoscerlo, né i laburisti né i conservatori. L’afflusso di giovani accorsi a votare al referendum scozzese è stato gravemente sottovalutato. E quando si muovono, i giovani cambiano veramente le cose.

La Gran Bretagna ha da sempre il partito socialista più moderato d’Europa, monarchico e già filocolonialista. Con Blair ha sdoganato il neoliberismo nella si- nistra europea. Si sta forse redimendo indicandole un nuovo ritorno alla social- democrazia, ora che il giocattolo dell’economia si è rotto?

Quello che è successo nel partito laburista riflette molte cose: prima di tutto che non c’è granché d’altro, l’estrema sinistra ha commesso un suicidio politico. E poi c’è un sistema elettorale che rende assai difficile l’esistenza di un terzo partito. La cosa incoraggiante è la presenza dei giovani, che ho notato per la prima volta in trent’anni, in un periodo durante il quale la politica, non soltanto la politica mainstream, si è atrofizzata. Blair non ha fatto altro che continuare il thatcherismo, legittimandolo col sorriso. Ma a dargli la sua aura in tutta Europa sono state le sue tre vittorie. “Così possiamo vincere anche noi, abbandonando il passato,” si dissero i vari leader che lo ammiravano, Schroeder, Veltroni e perfino Hollande. Ricordo con orrore Walter Veltroni qualche anno fa usare lo slogan di Obama Yes we can in una piazza romana. Dopo la crisi del 2008 il modello mediatico di Blair, la sua disinvoltura con le celebrità, il suo vincere senza sforzo sono diventati impossibili. Il blairismo è stata un’operazione estremamente abile ed efficace, c’è voluto molto tempo perché apparisse per quel che era.

Corbyn è il leader più a sinistra che il partito laburista abbia mai avuto in tutta la sua storia. Cercheranno di eliminarlo prima delle elezioni?

Non credo che la base del partito lo permetterebbe. Con quel mandato lui non ha certo intenzione di lasciare. E più rimane, più diventa difficile liberarsene. Tutto dipende da quello che succederà nel 2020, se vincerà o no. Il bello è che il suo programma, che in realtà è moderatamente socialdemocratico, sembra estremista. Ricordo che in uno dei suoi recenti discorsi, Jeremy disse che il partito avrebbe abolito le tasse universitarie reintroducendo l’istruzione superiore gratuita. Gli studenti gli si fecero attorno sbigottiti, chiedendogli se veramente un tempo non ci fossero state tasse universitarie.

La “special relationship” con gli Usa è il cardine della politica estera britannica e tra le cose che distanzia maggiormente Corbyn da molti parlamentari laburisti.

La cosiddetta special relationship è uno straordinario costrutto mito-ideologico. Per questo il dibattito sul Trident (il rinnovo dell’arsenale nucleare, motivo di netta rottura fra Corbyn e il partito parlamentare, Plp, ndr) sarà estremamente importante. Se la maggioranza del Plp sostenesse Corbyn sarebbe un importante punto di svolta. Cambiare indirizzo in politica estera è qualcosa che nessun leader laburista ha mai tentato. Attlee e Bevin (rispettivamente primo ministro e ministro degli esteri nel primo governo laburista del secondo dopoguerra, ndr) furono fieri sostenitori della Nato e del bombardamento su Hiroshima.

A questo proposito, nel suo recente saggio sulla «London review of books», lei ha definito come “in mala fede” (disin- genuous) l’applauditissimo discorso in parlamento con cui Hilary Benn (deputato laburista, ex ministro degli esteri ombra) giustificava i bombardamenti in Siria.

Veramente lo avevo definito “raccapricciante e moralmente disgustoso.” Avevo anche aggiunto quanto fosse spassoso vedere i conservatori applaudire quei passaggi che citavano Hitler e la guerra civile di Spagna, quando i loro stessi nonni o genitori erano stati appeasers. Tutti i loro predecessori erano stati sostenitori di Franco.

Come vede la questione Brexit, così trasversale dal punto di vista politico?

Credo che vincerà di stretta misura chi vuole rimanere, e poi ci sarà un forte aumento dell’euroscetticismo, un po’ come in Scozia con il separatismo. Da internazionalista, considero l’istituzione europea fondamentalmente non democratica. Tutte le antiche speranze che l’Unione Europea diventasse una federazione socialdemocratica capace di resistere allo sconfinamento statunitense sono tramontate da un pezzo, lasciando spazio a un allargamento geopolitico indiscriminato dettato dagli americani. Oggi l’Ue non è che un apparato per la rapida diffusione del neoliberismo, talvolta con metodi pressoché autoritari, basta vedere come sono intervenuti in Grecia, Irlanda, Portogallo, e anche in Italia. L’ironia è che sin dall’avvento del thatcherismo c’è stato un grosso spostamento della linea del partito laburista a favore dell’Europa unita. Storicamente il movimento laburista era contrario all’Ue, la considerava un’unione bancaria: la tesi opposta era che la si potesse cambiare dall’interno, rendendola socialmente più equa. L’Ue sarebbe poi puntualmente divenuta dominio dei banchieri. Ma quando Thatcher salì al potere, i sindacati divennero filo-europeisti. Oggi quei tempi sembrano molto lontani, la Scozia vuol usare l’Unione Europea con un ponte per uscire dal Regno, e quindi in grande maggioranza voterà per la permanenza. Quello che succederà in Inghilterra sarà dunque decisivo. Con l’uscita allo scoperto di Boris Johnson, il partito conservatore è ormai alla guerra civile. Corbyn è personalmente contrario sia all’Ue che alla Nato, cose impossibili da far digerire alla componente parlamentare. Concederà un voto secondo coscienza. Lasciare l’umore anti-Ue in monopolio alla destra è secondo me un errore: il vero problema in molte parti d’Europa è il fallimento della sinistra nell’opporsi a certe politiche dell’Ue. Personalmente, sono per uscire dall’Europa per ragioni del tutto opposte a quelle della destra.

March 29, 2016

Democracy Now interview on the Lahore Bombings

AMY GOODMAN:Welcome back to Democracy Now!, Tariq. Can you talk about what happened in Lahore?

AMY GOODMAN:Welcome back to Democracy Now!, Tariq. Can you talk about what happened in Lahore?

TARIQ ALI: Hi, Amy.

Amy, basically, what has been going on in Pakistan now for two to three decades is that madrassas, religious schools, have been created in large parts of the country, used as transmission belts. Added to that, there are camps, which are supposedly educational camps for some of these groups, which exist in different parts of the country, not just on the Afghan border, and it’s not a secret that in parts of the Punjab, the country’s largest and most important province economically and politically, in the southern part of this province, there have been a number of camps set up by these groups which have not been dealt with or investigated seriously by successive governments. And the prime minister of Pakistan, Nawaz Sharif, every time there is a terrorist outbreak, says exactly the same thing: This will never happen again, this will not be allowed. He’s beginning to sound like a broken gramophone record from old times. No one takes him seriously, which is why I think the Army and the Rangers are moving in to try and see what can be done. But even they face a very difficult task, because many, many years ago, during the first Afghan War against the Russians, backed by the United States, all these groups were created. A whole number of religious schools, or madrassas, were set up, where the curriculum was very militant, in terms of, you know, suggesting violence against unbelievers, etc. So what we are now witnessing is the result of all those dragon seeds that were sewn over three decades ago and which many politicians at the time in the frontier province near Afghanistan warned would make Pakistan uninhabitable unless something was done. Well, it wasn’t done, and we now have another outrage in Lahore.

The one thing, Amy, which I think it’s important to understand, is that purely on the theological front, it is utterly grotesque of any group claiming to be Muslim to suggest that there is Qur’anic or institutional hostility to Christianity within Islamic writings. Jesus is one of the most revered of prophets in the Muslim pantheon. The only woman mentioned and praised and regarded as honorable in the Qur’an is Maryam, Mary, Jesus’s mother. There are more references to her in the Qur’an than in the New Testament, to show that these religions are linked to each other; they grew out of each other; they believe in the same book, the Old Testament; and they are all monotheistic. So, theologically, there is absolutely nothing to justify this.

This is a political assault on the country’s culture, its life, to try and create a jihadi, Islamic State-type republic. And this group, this splinter group, has expressed its admiration for the Islamic State, or Daesh, and regard themselves as its followers in Pakistan. So we’re now seeing the internationalization of a conflict that began in Iraq and created this group, now attracting others because it carries out these terrorist attacks in the Middle East and, of course, in Paris and in Brussels. It’s part and parcel of the same problem.

AMY GOODMAN: So, this group, the Jamaat-ul-Ahrar, that claimed responsibility, a faction of the TTP, the Tehrik-i-Taliban—what is even the Tehrik-i-Taliban? You say it is connected to ISIS, to the so-called Islamic State?

TARIQ ALI: Well, I don’t know whether it is connected in a concrete way, but it’s certainly influenced by ISIS and regards this group with some admiration, because they’re doing things. They don’t talk about what they’re doing, but they talked about doing things. It’s a form of very strong Sunni fundamentalism, which is disregarded and alienates most Sunnis in the world, which regards a particular type of Islam, a variant of Wahhabism, which is the only one acceptable. The demands of these people, when they actually bother to make them, is a state governed exclusively by Sharia. But Sharia has many interpretations. There is no single interpretation of the Sharia or Islamic law. Some of it already exists in the country.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Tariq, the significance of this taking place in Punjab?

TARIQ ALI: Very much so. This is the area where the bulk of the recruits for the Pakistan Army, the Pakistan police force and the Rangers come from. This is the most populous province in the country. And if they’re boasting, as their leader did yesterday—”Yes, we’ve decided to take the war to the Punjab”—the question is raised: How come that the government, the provincial government, the central government, were not aware of this? We know, and it’s not a secret either in Pakistan or in Europe or anywhere else, that these groups are infiltrated by intelligence people who keep a watchful eye on them. They have people in there who report to them. What did they report? That there were attacks going to take place? We know now that some months ago the Lahore Literature Festival was not allowed to use a particular government venue because they said that they were fearful of terrorist attacks. So one assumes they were aware that this group was up to something. And it’s a complete breakdown of the intelligence networks if they couldn’t predict these attacks. I don’t believe it myself. I believe that the Muslim League of Nawaz Sharif, elements within it, didn’t want to take action against these groups, because they have indirect or possibly even direct links with them. They don’t want to upset the province, which is their power base. And now they’ve seen the result.

AMY GOODMAN: Tariq Ali, I also want to ask you about what’s happening in the capital of Islamabad. Thousands of Islamists are staging a sit-in outside the Parliament there to protest last month’s execution of Mumtaz Qadri, who assassinated reformist politician and Punjab Governor Salman Taseer five years ago. You grew up with the Punjab governor, Salman Taseer?

TARIQ ALI: Yes, I did. We were schoolfellows and very close friends, though we lost contact later on, except occasionally. But he was—on these questions, he was very open-minded. And the reason they targeted him was a poor woman, a Christian woman, was accused of blasphemy, on the basis of nil evidence, locked up in a prison. There was a big row about it in Pakistan. The press raised the issue. And Salman Taseer, as governor of the Punjab, decided to make a symbolic point, and he actually went into the prison and sat next to the woman and talked to her. This was regarded as blasphemy itself, and the religious group involved decided to punish him. He was shot dead by Mumtaz Qadri, who was one of his specially trained bodyguards, put into place in the police force to defend him. And all the other guards stood quietly and watched as this guy pumped bullets into Taseer. The judges were scared to convict him, so he was in limbo for some time, sentenced to death. No one would carry it out. The judge who finally said that the sentence had to be carried out has fled the country and is now in Dubai. So, this is his supporters, of the killer, the assassin, who are demonstrating against what was done to him on the 40th day after his funeral, which is a day for prayer and religious meditation, etc. And they organized this demonstration, demanding that Qadri be declared a martyr and a whole number of other totally ridiculous demands which no serious government could even think of accepting. And yet ministers, etc., have been talking and negotiating with them.

So, the country is in a total mess, Amy. I can’t stress this too much. And people don’t like talking about it, but unless and until the country’s social structure improves and people see an alternative, both on the level of education, health facilities, housing, there’s going to be a huge vacuum, which some of these Islamist groups fill. And I think it has to be pointed out that this is not only poor people who are behaving like this—they can sometimes be duped. This is a middle-class phenomenon. You have all over Pakistan, including in Lahore, the capital of the Punjab, very articulate, young, middle-class women preachers preaching a message of hate to middle-class people. They have nothing else. Their life is empty, so they go on this turn. And there have been many cases of a woman taking her three children from a pro-ISIS family and departing to Syria. No one knows what’s happened to her, when she’s coming back or not. The government is aware of all this. If I am sitting in London, they know it much better than me. And unless something is done to change the country from the top, nothing is going to change. This will carry on, and in a few months or a few years we’ll see the politicians repeating the same old nonsense.

March 1, 2016

Tariq Ali Against Trident—CND Rally, 27th February 2016

Tariq Ali spoke at Britain’s biggest anti-nuclear march in a generation yesterday alongside Jeremy Corbyn, Giles Fraser and party leaders at a rally organised by the CND. Thousands of protesters gathered in London, some travelling from as afar as Australia to protest against the renewal of Trident.

“There is no practical, utilitarian or financial justification for Trident but we need it because it upgrades Britain’s position in the world. I think it downgrades Britain’s position in the world […] If it really wants to upgrade its moral position in the world it needs to get rid of Trident,” he said.

“Were we to elect a Labour government under the leadership of Corbyn and his colleagues, there is a possibility that this demand first put up in the late 1950s will become a reality. All of this depends not simply on the political leaders, but on us. What are we going to do?”

February 26, 2016

Corbyn’s Progress

The UK state – its economy, its culture, its fractured identities and party system – is in a much deeper crisis than many want to accept. Its governors, at least in public, remain in semi-denial. English politicians assumed that the threat to the unitary state had been seen off after they got the result they wanted in the Scottish independence referendum. The results of last year’s general election suggested otherwise. The SNP now exercises a virtual monopoly of Scottish representation in the House of Commons and most opinion polls indicate a small majority in favour of Scottish independence. The impact of this on the crisis of Labourism, old and new, should not be underestimated. It is the most dramatic change in the UK party system since the foundation of the Labour Party itself.

The UK state – its economy, its culture, its fractured identities and party system – is in a much deeper crisis than many want to accept. Its governors, at least in public, remain in semi-denial. English politicians assumed that the threat to the unitary state had been seen off after they got the result they wanted in the Scottish independence referendum. The results of last year’s general election suggested otherwise. The SNP now exercises a virtual monopoly of Scottish representation in the House of Commons and most opinion polls indicate a small majority in favour of Scottish independence. The impact of this on the crisis of Labourism, old and new, should not be underestimated. It is the most dramatic change in the UK party system since the foundation of the Labour Party itself.

Add to this the following facts: 11.3 million votes obtained 331 seats for the Conservatives; 9.3 million got Labour 232 MPs, the Liberal Democrats with 2.4 million went down to eight, while the Greens and UKIP gained a single MP each for a million plus and 3.8 million votes respectively. A blatantly rigged electoral mechanism is not a cause for celebration; whatever else it may be, this is clearly not a representative democracy. Ed Miliband resigned immediately as leader following his defeat and the caretaker leader, Harriet Harman, decided not to oppose the Tories on the basic tenets of their austerity policies: she knew that a post-2015 Labour government would have done the same. The Labour Party that lost the election was conformist and visionless: it had forgotten what it meant to mount an opposition.

The new system for Labour leadership elections that Miliband introduced in 2014 was meant as a conciliatory gesture. He had been accused of winning the leadership only with the support of the hated trade unions, so he instituted a one member, one vote system, with one vote for any Labour voter or supporter who – though not a party member – was prepared to part with £3 (the French Socialists had used a similar method to elect Hollande). It was a step forward for democratisation, but the new rules also had the overwhelming support of the Parliamentary Labour Party. Most of them assumed that if outsiders had any effect at all it would be to help seal the status quo. And so it might have been had New Labour managed to come up with a halfway credible candidate. In order to preserve the fiction that the PLP remained a broad church that favoured diversity and loved a good debate, a few Blairites gave their vote to support a candidate from the minuscule parliamentary left. This strategy had worked before: last time round David Miliband nominated Diane Abbott as a candidate. In 2015 they hoped a left candidate would take away support from Andy Burnham, who was what passed for leftish, leaving the door open for Liz Kendall or Yvette Cooper.

Enter Jeremy Corbyn stage left. He may not be a charismatic figure, but he could never be mistaken for a PR confection. I have shared numerous platforms with him over the past forty years and on key issues he has remained steadfast. During the leadership debates he came across as uninterested in point-scoring and oblivious to media hostility. The Guardian came out for Yvette Cooper, the Mirror for Andy Burnham. Absolutely nobody, including Corbyn himself, thought that he could win. The campaign was intended just to show that there was an alternative to the neoliberal leadership that had ruled the country for the last three decades. What appealed to the young and to the many who had left the party in disgust during the Blair/Brown years – what appealed to the people who turned the campaign into a genuine social movement – was precisely what alienated the political and media cliques. Corbyn’s campaign generated a mass movement that renewed the base of the Labour Party – nearly two hundred thousand new members and counting – and led to his triumph. He won almost as many votes as all his opponents put together. Blair’s misjudged appeals (‘Hate me as much as you want, but don’t vote Corbyn’) and Brown’s out-of-touch attacks accusing Corbyn of being friendly with dictatorships (he was referring to Venezuela, rather than Saudi Arabia or Kazakhstan, states favoured by the New Labour elite) only won Corbyn more support. The Blairite cohort that dominates the Guardian’s opinion pages – Jonathan Freedland, Polly Toynbee et al – had zero impact on the result, desperate though they were to trash Corbyn. They were desperate enough even to give space – twice – to Blair himself, in the hope of rehabilitating him. Naturally, the paper lost many readers, including me.

Corbyn’s victory was not based on ultra-leftism. His views reflected what many in the country felt, and this is what anti-Corbyn Labour found difficult to grasp. Corbyn spelled it out himself in one of the TV debates:

We also as a party have to face up to something which is an unpleasant truth, that we fought the 2015 election on very good policies included in the manifesto but fundamentally we were going to be making continuing cuts in central government expenditure, we were going to continue underfunding local government, there were still going to be job losses, there were still going to be people suffering because of the cuts we were going to impose by accepting an arbitrary date to move into budget surplus, accepting the language of austerity. My suggestion is that the party has to challenge the politics of austerity, the politics of increasing the gap between the richest and the poorest in society and be prepared to invest in a growing economy rather than accepting what is being foisted on us by the banking crisis of 2008 to 2009. We don’t have to set this arbitrary date, which in effect means the poorest and most vulnerable in our society pay for the banking crisis rather than those that caused it.

How could any Labour MP disagree with that? What they really hated was his questioning of the private sector. John Prescott had been allowed to pledge the renationalisation of the railways at the 1996 Labour Party Conference, but after Blair’s victory the following year the subject was never raised again. Until now.

When I asked him when he first realised he might actually win, Corbyn’s response was characteristic of the activist that he remains: ‘It was in Nottingham during the last weeks of campaigning … you know Nottingham. Normally we think that fifty or sixty people at a meeting is a good turnout. I got four hundred and there were people outside who couldn’t get in. I thought then we might win this one.’ The crowds grew and grew, making clear that Corbyn was capable of mobilising and inspiring large numbers of people, and making clear too how flimsy the support was, outside the media, for the other candidates.

Subscribe now

His election animated English politics. His horrified enemies in the PLP immediately started to plot his removal. Lord Mandelson informed us that the PLP wouldn’t destroy their new leader immediately: ‘It would be wrong,’ he wrote, ‘to try and force this issue from within before the public have moved to a clear verdict.’ Blair, angered by this outburst of democracy in a party that he had moulded in his own image, declared that the Labour Party would be unelectable unless Corbyn was removed. Brown kept relatively quiet, perhaps because he was busy negotiating his very own private finance initiative with the investment firm Pimco (Ben Bernanke and the former ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet are also joining its ‘global advisory board’). Simultaneously, his ennobled former chancellor, Lord Darling, was on his way to work for Morgan Stanley in Wall Street. Blair, an adviser to J.P. Morgan since 2008, must have chuckled. At last, a New Labour reunion in the land of the free. All that ‘light-touch’ regulation was bearing rich fruit. Virtually every senior member of the Blair and Brown cabinets went to work for a corporation that had benefited from their policies. The former health secretary Alan Milburn, for example, is on the payroll of several companies involved in private healthcare and is currently working for Cameron as the chair of his Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission. It was not just the Iraq War that was responsible for the growing public disenchantment with New Labour.

The establishment decided to wheel out the chief of defence staff, Sir Nicholas Houghton. Interviewed on 8 November, he confided to a purring Andrew Marr that the army was deeply vexed by Corbyn’s unilateralism, which damaged ‘the credibility of deterrence’. On the same show, Maria Eagle, a PLP sniper with a seat on the front bench as the shadow defence secretary, essentially told Marr that she agreed with the general. Just another day in the war against Corbyn. The Sunday Times had previously run an anonymous interview with ‘a senior serving general’. ‘Feelings are running very high within the armed forces,’ the general was quoted as saying, about the very idea of a Corbyn government. ‘You would see … generals directly and publicly challenging Corbyn over … Trident, pulling out of Nato and any plans to emasculate and shrink the size of the armed forces … There would be mass resignations at all levels … which would effectively be a mutiny. You can’t put a maverick in charge of a country’s security.’ If anything expressed the debasement of Britain’s political culture it was the lack of reaction to this military interference in politics. When Corbyn tried to complain, a former Tory grandee, Ken Clarke, declared that the army was not answerable to Parliament, but to the queen. Anything but Corbyn: even a banana monarchy.

In December, Cameron sought parliamentary approval for sending British planes to bomb Islamic State in Syria. From his point of view, a happy possible side effect of the predictably successful vote was that it might make Corbyn’s position as leader untenable. Having been shafted by Maria Eagle he was about to be stabbed in the front by Hilary Benn, whose disingenuous speech – Hitler, with the Spanish Civil War thrown in for good measure – was loudly cheered by Tory and hardcore Blairite MPs. (What a pity that the two-hour row between Hilary Benn and his father over the Iraq War, of which Hilary was an ardent supporter, was never taped and transcribed in Tony Benn’s printed diaries – though he did talk about it to friends.) But this, too, failed to unseat Corbyn. The Labour leader – wrongly, in my opinion – permitted a free vote on the insistence of close colleagues. (John McDonnell, the shadow chancellor, insisted it was a ‘matter of conscience’.) In the end 66 Labour MPs voted with the Tories to bomb targets in Syria. Some of them had been given presentations by the Ministry of Defence designed to convince them that there would be no collateral damage. But the majority of the PLP opposed the bombings and voted with Corbyn. Frustrated yet again, the media sought to attribute the failure of more Labour MPs to vote for the bombing to the ‘bullying’ of Stop the War, an organisation of which Corbyn had been the chair since the death of Tony Benn. For a week or so it was open season on the antiwar coalition. One effect was to scare the Greens and cause the party’s former leader Caroline Lucas to resign from the STW committee. Was this really her own decision or was it the idea of the inept Natalie Bennett, fearful that Green supporters were being carried away by the pied piper from Islington? Corbyn himself was unmoved: he told the audience at a STW fundraising dinner that he was proud of the work the organisation had done from the time of the Afghan war onwards, and that he was proud to serve as its chair.

Later in the week of the Syria vote, the Oldham by-election, which had, again, been talked up as a possible disaster for Corbyn (George Eaton in the New Statesman claimed to have been told by ‘an insider’ that ‘defeat was far from unthinkable’) was instead a resounding victory. All this left Corbyn’s enemies on the defensive. A reshuffle early in the New Year removed Eagle and a few others, but Benn was left in place, a reflection of the political difficulties confronting Corbyn. Any attempts to change the political balance of the shadow cabinet have been greeted with threats of mass resignations. How long can Labour MPs carry on this war on their own leader? Corbyn will not be bullied or demoralised into standing down. The snipers will use any ammunition to achieve their goal. Bad local election results in May? Blame Corbyn. Sadiq Khan, the Labour candidate in the London mayoral elections, stresses how business-friendly he is – probably more than the Conservatives’ Zac Goldsmith, who, being wealthy himself, doesn’t have to suck up to the CBI. If Khan wins he’ll be touted as another new challenger for the leadership. If he loses it will, of course, be Corbyn’s fault. As for the elections to the Scottish Parliament, the opinion polls suggest a huge SNP triumph. Corbyn’s fault? Of course. The zombies running Scottish Labour presided over the 2015 meltdown, the worst defeat since Labour was founded. But when they lose this time, it will be Corbyn who is to blame. I doubt very much if this particular claim will stick: too crude and too late.

Even though there is no constitutional mechanism to get rid of a Labour leader through a vote of no confidence by the PLP, there is little doubt that were such a vote to take place, Corbyn would call a new leadership contest. Would he need to repeat the business of getting enough PLP sponsors or could he, as the incumbent, run again automatically? This is a grey area and would probably require a NEC vote that he would win. The rule change would have to be ratified by the Labour Party Conference. His high ratings among party members suggest that Corbyn would win again. What then? A separate grouping of Blairites à la SDP? The latter boasted a few well-known and intelligent social democrats – Roy Jenkins, Shirley Williams, David Owen, Peter Jenkins and Polly Toynbee – but they were still destroyed by the electoral system and had to stave off obscurity by a political transplant, merging with the Liberals, an experiment that ended in disaster in 2015. Were they to try the same, the Blairites would fare much worse, even if one of their number vacated a safe seat to make room for David Miliband.

*

While the mood in Scotland shifted leftwards, the centre of politics in England has moved so far to the right since the 1980s that even though the Corbyn/McDonnell economic programme is not very radical – what it offers on the domestic front is a little bit of social democracy to strengthen the welfare state and a modest, fiscally manipulated form of income distribution – it is nevertheless a break with the consensus established by Thatcher, Blair/Brown and Cameron. The thoughts and habits that have dominated the culture for almost four decades – private better than public, individual more important than society, rich more attractive than poor, a symbiosis of big money and small politics – constitute a serious obstacle. Many who concentrate their fire on Corbyn’s supposed unelectability shy away from its corollary: under the present dispensation there is no room for any progressive alternative. The dogmatic vigour with which the EU and its Troika push back any attempts by the left to shift the obstacle has contributed to a disturbing growth of the right in France, the Netherlands and now Germany, as well as to the election of hard-right governments in Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Croatia. This is in part a result of the refusal to tolerate even a modicum of social democracy.

The creation of Momentum, which explains itself as ‘a network of people and organisations to continue the energy and enthusiasm of Jeremy Corbyn’s campaign’, united old Bennites long asleep in the Labour Party and young activists drawn to the leadership campaign. Corbyn likes to boast that his own local constituency party has 3300 members and 2000 registered supporters – more than five thousand in all, in a constituency where the Labour vote is nearly 30,000. One in six Labour voters is a party member. This is an astonishing and exemplary figure but one not matched elsewhere. A body like Momentum could help to build support by working within existing campaigns against war and austerity, registering voters, encouraging school leavers and students to become politically active, regularly debating opposing views (and not just on social networks). Only a movement of the sort that elected Corbyn as leader can send him to Downing Street. The effect of the Scottish example on many in England should not be underestimated. Even media cynics were staggered by the degree of politicisation in Scotland and the debates and discussions taking place everywhere before the referendum. The tens of thousands who flocked to join Corbyn’s Labour Party were not that different from those who moved to support the SNP. The SNP’s parliamentary cohort in Westminster provides solid support to the Labour left on a number of issues and will, no doubt, do so again when the Tories bring the projected renewal of Trident to the Commons in April, giving their allies in the PLP another opportunity to destabilise Corbyn, or so they hope.

In Scotland there is a large majority in favour of the removal of nuclear missiles from Scottish shores. Elsewhere in the UK, public opinion is more evenly divided and fluctuates depending on the way the question is posed. A number of retired generals have questioned Trident’s utility, and in his memoirs even Blair admitted that in terms of both cost (£31 billion, with another £10 billion in reserve and lifetime costs predicted to exceed £180 billion) and utility, both ‘common sense and practical argument’ dictated getting rid of it. He was opposed to doing so because it would be ‘too big a downgrading of our status as a nation’. There is no other reason. Britain needs Trident as a symbol – and to be a notch above or below the Germans, depending on one’s point of view. Those who dream of an English finger on the nuclear trigger inhabit a fantasy world: the finger will always be American. That’s why the notion, recently discussed in relation to the EU and Brexit, that the Commons would vote through a motion declaring that the UK is a sovereign state caused much merriment abroad. Everybody knows that Britain has been a vassal state since 1956. Brexit (which I favour for good socialist reasons) can’t restore sovereignty. The only truly sovereign state in the Western world is the United States. It’s worth noting that the SNP is for Nato. So was Syriza in better times. So is Podemos, one of whose leaders recently declared that Nato could help democratise the Spanish Army. To each their illusions.

Corbyn’s radicalism lies not so much in what he is proposing on the domestic front – for that is increasingly the common sense of many economists and others, including the self-declared democratic socialist Bernie Sanders – but in his desire to change foreign policy. His criticism of the absurdly high level of military expenditure is echoed by some prominent US economists in relation to their own country. Joseph Stiglitz (a Corbyn adviser on the economy) and Linda Bilmes have argued that America’s spending on wars since 2003, estimated now at nearly $8 trillion, is crippling the country. ‘A trillion dollars,’ they note,

could have built eight million additional housing units, could have hired some 15 million additional public school teachers for one year; could have paid for 120 million children to attend a year of Head Start; or insured 530 million children for healthcare for one year; or provided 43 million students with four-year scholarships at public universities. Now multiply those numbers by three.

There are a number of US historians and analysts – those of the realist school – who aren’t shy in their criticism of their country’s foreign policy. (Trump’s recent assault on Bush over the Iraq War owes much to their work.) John Mearsheimer at Chicago, Stephen Walt at Harvard, Barry Posen at MIT and Christopher Layne in Texas are joined by a former four-star general, Andrew Bacevich. Their thinking continues to evolve. In American Empire, Bacevich argued against the previous realist view that US Cold War policy was a defensive response to Soviet ambitions and insisted that its expansion of conflict to Eurasia in the 1940s was part of a drive to establish global hegemony. Yet such opinions when voiced by Corbyn and his circle are denounced as anti-American, extremist, a threat to Britain etc. Corbyn has long been hostile to both Nato and the EU as presently constituted, but his views on these matters are so alien to the PLP that they have for the time being been shelved.

During the Blair/Brown period the Labour Party unlearned social democracy of the Crosland variety, no matter anything resembling the classical model of early socialism. Corbyn knows it’s vital that the party relearns social democracy. It once seemed a hopeless task. Now, amazingly, they have a chance. The statistics about global inequality desperately need someone who can explain them in terms that can anger, mobilise and inspire people. If Corbyn can do this, it would mark an important shift in English politics.

January 21, 2016

Royaume-Uni: Etre ou ne pas être européen?

Pourquoi les Britanniques se sont-ils mis en tête d’organiser un référendum sur leur appartenance à l’Union européenne ? “L’Obs” a interrogé deux intellectuels de la gauche outre-Manche, le sociologue Anthony Giddens et l’historien Tariq Ali

Pourquoi les Britanniques se sont-ils mis en tête d’organiser un référendum sur leur appartenance à l’Union européenne ? “L’Obs” a interrogé deux intellectuels de la gauche outre-Manche, le sociologue Anthony Giddens et l’historien Tariq Ali

C’est en janvier 2013 au siège de Bloomberg, au coeur de la City de Londres, que David Cameron lance sa bombe : la promesse, s’il est réélu en 2015, d’un « référendum pour ou contre le maintien du Royaume-Uni au sein de l’Union européenne » d’ici à la fin de 2017. Dernière lubie d’une arrogante Grande-Bretagne qui pousserait à son terme la logique de son « splendide isolement » ? Le Premier ministre conservateur jure alors le contraire : « Je ne veux pas quitter l’Union européenne, je veux la réformer. » Il s’engage à mener des négociations avec Bruxelles pour remettre en question certaines règles communautaires – ou plutôt pour permettre, dans la pure tradition anglaise, à Londres de s’en afranchir. Le Parti travailliste renile aussitôt le danger derrière ce projet né sous la pression des eurosceptiques du Parti conservateur et de l’Ukip, l’extrême droite britannique, qui marquent à la culotte le Premier ministre. Car ceux-là n’espèrent rien de moins que le « Brexit », la sortie de l’Union, désignée par ce mot-valise formé à partir de « British » et d’« exit ». En mai dernier, David Cameron remporte la première manche en se faisant réélire. Depuis, il croise le fer avec ses partenaires européens. Sa shopping list a été accueillie fraîchement à Bruxelles. Le Premier ministre demande à « approfondir le marché unique » sur trois axes essentiels : ouverture à de nouveaux secteurs, réduction de la réglementation et multiplication des accords commerciaux avec des pays hors UE. Il souhaite également protéger la City et la livre sterling contre la prééminence des pays de la zone euro. Jaloux de sa souveraineté, il refuse en outre de se soumettre à l’exigence de construire l’« union toujours plus étroite » inscrite dans le traité de Rome et veut renforcer le système qui permet à plusieurs Parlements de se regrouper pour bloquer des décisions de Bruxelles. Mais c’est le volet immigration qui est le plus controversé car il porte atteinte à la libre circulation et à la non-discrimination : parti en guerre contre le « tourisme social », David Cameron réclame la suspension pendant quatre ans des aides sociales pour les Européens s’installant au Royaume-Uni. « Si nous ne pouvons pas obtenir un accord, ce qui selon moi n’arrivera pas, alors nous devrons repenser si l’UE est faite pour nous. Et, comme je l’ai déjà dit, je n’écarte rien », menace-t-il. Acculé par les eurosceptiques, qui trouvent sa liste de réclamations trop courte, et les sondages qui donnent le vote « out » à deux doigts des 50%, le Premier minister doit montrer qu’il se bat pour arracher des concessions. Car la question divise bel et bien la société, la droite comme la gauche, la sphère économique comme les intellectuels. Les businessmen proeuropéens s’opposent au lobby Business for Britain, les chercheurs du groupe Historians for History contrent les arguments des Historians for Britain. Nous avons choisi d’interroger deux grands intellectuels de gauche, le sociologue Anthony Giddens et l’historien Tariq Ali. Le premier appartient au Parti travailliste et votera « in » ; le second, igure de la gauche radicale, mettra un bulletin « out » dans l’urne. Mais ni l’un ni l’autre n’osent se prononcer sur l’issue du référendum. Car, désormais, « la thèse selon laquelle le “Brexit” n’arrivera pas et ne pourra pas arriver est fausse », avertit l’ancien ministre travailliste des Afaires européennes Denis MacShane. « Les Britanniques se rapprochent très rapidement du moment où il leur faudra dire “bye bye, Europe”. »

Par Anthony Giddens

Pourquoi faut-il selon vous rester dans l’Union européenne?

Parce que le Royaume-Uni est un pays européen par sa situation géographique. Mais aussi parce que je suis convaincu que seul un projet collectif peut nous permettre d’aborder cette période extrêmement imprévisible de l’histoire mondiale : chaos au Moyen-Orient, ralentissement de l’économie mondiale, arrêt de la croissance des Brics [le Brésil, la Russie, l’Inde, la Chine et l’Afrique du Sud, NDLR]… Je crois encore en l’Union européenne, bien qu’elle soit confrontée aux problèmes structurels les plus graves depuis sa création. C’est la plus grande économie du monde, elle a apporté une paix historique, elle a encore beaucoup de potential. Et, pour préserver ces acquis, je pense qu’il faut au contraire encore plus de coordination. Pour sauver la zone euro, il faut davantage d’ intégration fiscale, plus de partage des risques entre ses membres et d’autres mécanismes structurels, nécessaires au fonctionnement d’une zone à monnaie unique. La crise des migrants montre elle aussi que plus de coordination est nécessaire : les pays européens doivent impérativement se doter d’une politique des frontières commune. Face au déficit de légitimité démocratique, il faut modifier le fonctionnement de l’Union, en élisant par exemple directement ses dirigeants. Mais, alors que la tendance est au repli nationaliste, a-t-on encore le temps d’aller vers plus d’intégration?

Votre point de vue est en e_et loin d’être partagé par la majorité de vos concitoyens…

J’aurais souhaité que le Royaume-Uni soit plus intégré dans l’Union, mais il considère depuis toujours qu’il occupe une position spéciale en Europe. Dans la presse, on ne lit jamais « le Royaume-Uni et le reste de l’Europe », mais toujours « le Royaume- Uni et l’Europe ». Cela vient de notre passé d’empire et de notre langue qui entretient notre proximité avec les Etats-Unis. La plupart des Britanniques s’intéressent peu à l’Union. A l’époque du discours prononcé par Cameron à l’agence Bloomberg, en 2013, une étude avait montré qu’ils ne la classaient alors qu’au dixième rang de leurs priorités.

Qu’est-ce qui inluera alors sur l’issue du vote?

Ce référendum est particulier car il est dû au moins autant, si ce n’est plus, à des considérations politiques qu’à une renégociation de notre relation à l’Union européenne. Il tire ses origines de la progression de l’Ukip et des torys eurosceptiques. David Cameron l’a utilisé avec succès comme une manoeuvre dilatoire qui lui a permis de gagner les élections. Maintenant, il paie les pots cassés, car la majorité des Britanniques s’y intéresse surtout parce qu’il y est question d’immigration – plus précisément, d’immigration d’Europe de l’Est. La plus sensible des demandes de Cameron à Bruxelles est précisément celle des aides sociales aux migrants. C’est préoccupant car ce sera peut-être ce point qui, à la fin, décidera du résultat. Pour de nombreux électeurs, l’UE signifie « immigration ». Et ils assimilent les migrants à la perte d’identité. Ces derniers deviennent malgré eux les réceptacles des sentiments de détresse et d’impuissance face à des décisions sur lesquelles les Britanniques n’ont aucune prise. Cette question est pour eux d’autant plus importante qu’elle afecte un pays déjà fragilisé par une autre crise identitaire, provoquée par le nationalisme écossais.

L’Union européenne survivrait-elle sans le Royaume-Uni?

Ce serait une perte sérieuse pour l’UE, au moment où elle traverse une série de graves crises. Lorsque j’ai écrit mon livre sur son avenir, il y a trois ans, il n’y avait que la crise de l’euro. Aujourd’hui s’y ajoutent celle des réfugiés, les relations diiciles avec la Russie, la montée du populisme… Si le Royaume-Uni s’en allait, non seulement une période d’incertitude s’ouvrirait, le temps de définir ses nouvelles relations avec les Européens, mais ce serait aussi la première fois qu’un pays quitterait l’Union. Jusqu’ici, les Etats rêvaient de rejoindre l’UE. Aujourd’hui, certains menacent d’en sortir. Elle est réellement en danger.

Et le Royaume-Uni sans l’UE ?

Les anti et proeuropéens tiennent des discours totalement opposés. Les premiers assurent que nous serons enfin libres, débarrassés des réglementations européennes, que nous pourrons commercer avec le reste du monde… Les seconds disent ce que je dis. Mais je ne fais pas partie de ceux qui pensent que le Royaume-Uni ne pourrait pas s’en sortir en dehors de l’Union européenne. Il se trouverait un nouveau rôle, mais beaucoup moins important. Il conserverait un grand nombre de relations économiques avec l’Europe. Ce ne serait probablement plus le Royaume-Uni, mais le « Royaume désuni » car les Ecossais, majoritairement proeuropéens, voteraient leur indépendance. Son statut au Conseil de Sécurité et dans toutes les organisations internationales serait remis en question. Les Etats-Unis perdraient tout intérêt pour lui. Mais il pourrait aussi se réinventer comme nation commerçante. Ce serait très di_érent de la Grande-Bretagne des années 1950 dont rêve Nigel Farage, le leader de l’Ukip. Il y aurait non pas moins, mais plus d’immigration parce qu’on ne pourrait vivre replié sur soi. Il lui faudrait imaginer un nouveau modèle, car ce pays est di_érent de la Suisse et de la Norvège. Mais je ne pense pas que David Cameron souhaite en arriver là. S’il y avait eu un référendum quand il a pronounce son discours à Bloomberg, les Britanniques auraient voté contre le « Brexit ». Aujourd’hui, je n’en suis pas sûr. Ce ne sont ni le bon moment ni les bonnes raisons de tenir un tel scrutin. Mais nous voilà piégés.

Par Tariq Ali

Vous avez annoncé que vous voteriez contre le maintien du Royaume-Uni dans l’Union européenne. Pourquoi?

Je n’avais pas prévu de participer à ce référendum car ce débat me semblait inutile. Mais, après avoir vu la Grèce, l’Irlande, le Portugal étranglés par l’austérité, j’ai décidé de voter contre l’Union. C’est une institution antidémocratique – le Parlement a des pouvoirs très limités, et toutes les décisions sont prises par le conseil des ministres – et une machine bureaucratique au service du néolibéralisme. Elle alimente la désa_ection des citoyens pour les élites politiques et la poussée de l’extrême droite en Europe. L’Union a besoin d’un choc pour changer. Le « Brexit » serait un choc. J’aurais aimé que la gauche se lance dans une campagne pour l’Europe, mais contre l’Union européenne, afin de montrer que nous sommes critiques envers l’UE pour des raisons qui n’ont rien à voir avec le chauvinisme de la droite et de l’extrême droite anglaises antieuropéennes. Si Jeremy Corbyn [le nouveau leader radical du Labour, NDLR] s’était déclaré pour le « Brexit », cela aurait donné lieu à une immense campagne à gauche car nous sommes nombreux à partager cette opinion.

Pourquoi Corbyn a-t-il décidé de s’opposer au « Brexit »?

Jeremy n’a jamais été un grand supporter de l’UE, qu’il considère comme une machine capitaliste. Il a dit qu’il était très insatisfait de son fonctionnement actuel et que nous allions devoir lutter de l’intérieur. Mais il a préféré s’en tenir là pour garder uni le Parti travailliste. C’est dangereux. On risque de se retrouver en Grande-Bretagne dans une situation semblable à celle de la France : l’Ukip, l’extrême droite anglaise, s’impose comme le seul parti représentant la colère des citoyens contre l’élite politique et les institutions européennes. C’est une situation étrange : l’euroscepticisme est principalement porté par l’Ukip, mais la gauche est très nerveuse aussi. Cependant, la majorité de la population ne se sent pas concernée par l’Union européenne.

D’où vient ce manque d’intérêt?

Le Royaume-Uni s’est toujours comporté comme un pays atlantiste plutôt qu’européen. Est-ce parce qu’il est séparé géographiquement du continent ? Est-ce parce que l’Empire britannique a entretenu l’illusion qu’il n’avait pas besoin de l’Europe pour .tre une grande puissance ? Initialement, la gauche comme la droite .taient oppos.es . l’id.e de faire partie de l’Europe. C’est le Parti conservateur, sous Edward Heath, qui a fait entrer le Royaume-Uni dans le march. Commun en 1973. Il esp.rait ainsi ne pas tomber compl.tement sous l’influence américaine. Cela n’a jamais vraiment marché. Puis, dans les années Thatcher, ce sont les syndicats qui se sont intéressés à l’Europe : c’était l’époque où Jacques Delors parlait d’Europe sociale. Mais cet état d’esprit a disparu. Les élites politiques lointaines de l’UE, le chômage, les migrants européens, que l’Ukip accuse de prendre le travail des Britanniques… Tout cela crée un sentiment antieuropéen.

Ce référendum porte donc bel et bien sur l’Europe?

La majorité des Britanniques se fiche de la manière don’t l’Union fonctionne. C’est principalement un débat sur l’économie et partiellement sur l’identité. L’identité britannique étant fracturée puisque l’Ecosse est déjà presque partie, c’est laquestion de l’identité anglaise qui se pose. Mais comment la définir dans un pays qui a des millions de migrants ? Ce r.f.rendum est r.v.lateur de la crise que traverse l’Etat britannique dans sa structure m.me.

Que serait l’Union européenne sans le Royaume-Uni?

Le « Brexit » signifierait le début de la fin pour l’Union telle qu’elle est aujourd’hui. L’Allemagne profiterait de ce départ pour la reconstruire à son image. L’Europe a toujours été une construction franco-allemande, mais Berlin ne regarde plus Paris commeun allié sérieux. Or la puissance française repose sur le fait que l’Allemagne la reconnaisse comme son égale.

Et le Royaume-Uni sans l’Union européenne?

En cas de « Brexit », je pense c’est le modèle norvégien qui s’imposerait. Sur le plan commercial, ça ne changerait donc pas grand-chose : le Royaume-Uni continuerait à travailler avec l’UE, il signerait avec elle des accords spécifiques qui le contraindraient à accepter bon nombre de ses règlements. La City de Londres resterait au centre de la finance européenne. On serait toujours dans l’Otan comme la Norvège. En revanche, cela mettrait un coup d’arrêt à l’immigration européenne, puisqu’il faudrait un visa de travail. Et l’Ecosse, proeuropéenne, voterait pour se séparer du Royaume-Uni afin de rester dans l’Europe. En vérité, l’élite britannique a la trouille de sortir de l’Union européenne. Je crois qu’elle va se lancer dans une campagne de peur à coups d’arguments fallacieux : on va nous marteler que ce sera terrible pour notre économie. Mais je ne pense pas pour autant que le « Brexit » rendrait le Royaume-Uni meilleur. Cela conduirait seulement le pays à se regarder tel qu’il est : une petite île du nord de l’Europe qui ne joue dans la cour des grands que parce qu’elle est liée aux Etats-Unis. Mais si l’on reste dans l’Union européenne, rien ne changera.

January 12, 2016

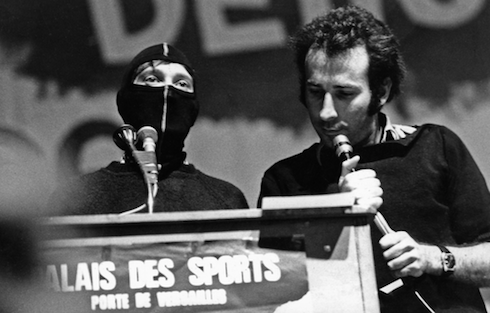

A Letter from Atlantis: Remembering Daniel Bensaid

This essay is taken from the introduction to Daniel Bensaid’s An Impatient Life , published by Verso Books.

Successful revolutions always try to reproduce themselves. They usually fail. Napoleon carried the Enlightenment on the end of a bayonet, but English reaction, Spanish nationalism and Russian absolutism, finally defeated him. The triumphant Bolsheviks, disgusted by social-democratic capitulation at the advent of the First World War, orchestrated a split within the working class and formed the Communist International to extend the victory in Petrograd to the entire world. They were initially more successful than the French. Premature uprisings wrecked the revolution in Germany, destroying its finest leaders – Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and many others – and driving the German landed and bourgeois elite into Hitler’s embrace. In Spain, a united front of the European fascist powers (passively assisted by Britain and France) brought Franco to power. In France and Italy, the Communist platoons grew into huge battalions during the Second World War and excercised an unchallenged hegemony within the working class for three decades, but without any meaningful strategy to dismantle capital- ism. Here the close alliance with the narrowly defined needs of the Soviet state precluded any such possibility. Communists in China and Vietnam proved more successful, for a while. The Cuban revolution, the last till now, was no exception. Its leaders, too, were convinced that careful organisation and a handful of armed cadres could succeed anywhere in South America. It was a tragic error, costing the lives of Che Guevara and hundreds of others across the continent.

The Stalinisation of the Soviet Union and the execution of most of Lenin’s closest comrades led to the creation of dissident Communist groupuscules self-defined as Trotskyists. From Europe to China, these included some of the finest minds in their respective countries. South America, by contrast, tended to produce slightly eccentric equivalents. Britain had never experienced a mass Communist party. It made up for this by producing some of the most virulent sects within the Trotskyist framework. The late historian E.P. Thompson had one of these in mind when he described English Trotskyists as little more than stunted opposites of Stalinism, who had in their own practice reproduced the structures pioneered by those they claimed to oppose.

In France, where dissidence fermented inside the ideological vats of the Parti Communiste Français, the results were different. The intellectual and political culture was rigid, but its influence on the French left-wing intelligentsia as a whole provoked debates and discussions that were on a higher theoretical level than elsewhere (with the exception of Italy). After the Cuban revolution and during the Algerian war of independence, many young intellectuals inside the student wing of the PCF began to find its politics stifling. This led to the creation of the Jeunesse Communiste Révolutionnaire and its merger with the least sectarian wing of Trotskyism, led by Pierre Frank and Ernest Mandel. Reading this book brought back many nice memories of comrades who formed the core of the JCR, some of whom are still good friends. The first half of these memoirs also constitutes the intellectual history of the 68 generation. It’s amazing now to be reminded how many of those active in the political and cultural establishment of contemporary France were once on the far left. The JCR’s big rival within the Trotskyist world was the Organisation Communiste Internationaliste, combining a rigid sectarianism with an elastic opportunism. Some of its central figures were asked by Mitterrand to join the Socialist Party. He needed them to combat the PCF and its residual Stalinism. Who better to approach than the OCI? And so Jospin became the prime minister of France. Running into Krivine at some occasion, Jospin shook his hand warmly and whispered in his ear: ‘I always told your lot that we would take power before you’.

It is not easy to write in times of defeat, in an epoch where the triumph of Capital (the real thing, not the great book) has frightened the young away from posing an effective challenge via a carefully considered alternative. Those who assumed, stupidly, that with the fall of the Soviet Union the road was clear for a real, pure socialism, gravely underestimated the tectonic shift. Bensaïd was not one of this crowd. He grappled with real problems till the very end of his life. Ernest Mandel’s optimism of the will and optimism of the intellect had created within the ranks of the European far left a belief that revolution was on the horizon. The events of 1968 fuelled such a view. We were all believers. As Daniel writes, it was this belief that burnt out the large Spanish group of Trotskyists. They were demo- bilised by the peaceful transition from a right-wing republic to a social-democratic monarchy. The country in Europe that came closest to a revolution was Portugal, but here too, a clever social democrat outwitted (DB might have called it débordemont– unity in action to outflank and overtake) the groups to his left.

Reading much of this material today is like delving into the archives of Atlantis. With official Communism dead, how could its Trotskyist offspring survive? There were two solutions: the first was to launch a new broader party of the left, the second to retreat into a bubble of its own making and insist that everyone sing from the same hymn-sheet.

So much for the politics, what of the author? Daniel Bensaïd was one of the most gifted European Marxist intellectuals of his generation. Born in Toulouse in 1946, he was schooled at the Lycées Bellevue and Fermat, but the formative influence was that of his parents and their milieu. His father, Haïm Bensaïd, was a Sephardic Jew from a poor family in Algeria who moved from Mascara to Oran, where he got a job as a waiter in a café and after a short spell discovered his real vocation. He trained to be a boxer, becoming the welterweight cham- pion of North Africa.

Daniel’s mother, Marthe Starck, was a strong and energetic Frenchwoman from a working-class family in Blois. At eighteen she moved to Oran. She met the boxer. They fell in love. The French colonswere deeply shocked and tried hard to persuade her not to marry a Jew. She was, they warned, bound to get VD and have abnormal children. But Marthe was a strong-willed women and, as Bensaïd records in his memoirs, capable of taking on anyone, including, much later, her son’s collaborationist headmaster when he attempted to discipline the boy for his anti-fascist opinions.

With France occupied by the German fascists and the bulk of the country’s elite in collaborationist mode, with its own capital at Vichy, the French administration fell into line. As a Jew, Daniel’s father was arrested and held at the Drancy internment camp pending deportation to Auschwitz. But unlike his two brothers, he survived, thanks largely to his wife who had an official Vichy certificate stating her ‘non-membership of the Jewish race’. In this affecting book, Daniel notes that these barbarities had taken place on French soil only a few decades prior to 1968. Le Bar des Amis, he writes, was a cosmopolitan location. Spanish refugees, Italian anti- fascists, former Resistance fighters, workers, post workers, railway workers. The local Communist Party branch held meetings there. Given his mother’s fierce Republican and Jacobin views (when a relative, after watching a syrupy French TV programme on the British monarchy, expressed doubts regarding the guillotining of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, Marthe did not speak to him for ten years), it would have been odd if young Bensaïd had become a monarchist. His father died of cancer in 1960.

Angered by the massacre of demonstrators at the Métro Charonne in 1961 (ordered by Maurice Papon, chief of police and former Nazi collaborator), Daniel joined the Union of Communist Students. But he soon became irritated by party orthodoxy and joined a left opposition within the Union organised by Henri Weber (currently a Socialist Party senator in the upper house) and Alain Krivine. The Cuban revolution and Che Guevara’s odyssey did the rest. The dissidents were expelled from the Party in 1966. That same year, Bensaïd was admitted to the École Normale Superieure in Saint-Cloud and moved to Paris. Here he helped found the Jeunesse Communiste Révolutionnaire (JCR), young dissidents inspired by Che and Trotsky, which later morphed into the Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire (LCR).

In 1968, together with Daniel Cohn-Bendit, he formed the 22 March Movement in Nanterre, the organisation that helped to deto- nate the uprising which shook France in May–June of that year. Bensaïd was at his best explaining ideas to large crowds of students and workers. He could hold an audience spellbound, as I witnessed in his native Toulouse in 1969 when we shared a platform at a rally of ten thousand people to support Alain Krivine’s presidential campaign. His penetrating analysis was never presented in a patronising way, whatever the composition of the audience. His ideas derived from classical Marxism – Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, Luxemburg, as was typical in those days – but his way of looking at and presenting them was his own. His philosophical and political writings have a lyrical ring – at particularly tedious central committee meetings he was seen immersed in Proust – and resist easy translation into English.

As a leader of the LCR and the Fourth International to which it was affiliated, he travelled a great deal to South America, especially Brazil, and played an important part in helping to organise the Workers Party (PT) that subsequently came to power under Lula. An imprudent sexual encounter shortened his life. He contracted HIV and for the last sixteen years of his life was dependent on medicine to keep him going, but with fatal side effects: a cancer that finally killed him.

Physically, he was a shadow of his former self, but the intellect was not affected and he produced over a dozen books on politics and philosophy. He wrote of his Jewishness and that of many other comrades, emphasising how this cultural identity had never led him, nor most of them, to follow the path of a blind and unthinking Zionism that was also deeply reactionary. For former Communists turned Zionists, it was Israel now that had to be supported, right or wrong. DB disliked identity politics and his last two books – Fragments mécréants (An Unbeliever’s Discourse) and Eloge de la politique profane (In Praise of Secular Politics) – explained how this had become a substitute for serious critical thought. He was France’s leading Marxist public intellectual, much in demand on talk shows and frequently writing essays and reviews for Le Monde and Libération. At a time when a large section of the French intelligentsia had shifted its terrain and embraced neoliberalism, Bensaïd remained steadfast. Even in the sixties he had avoided the clichés of left-talk; instead, he thought creatively, often questioning the verities of the far left. What would he have made of the travails of the Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste – sectarian and economistic, reduced to warring factions, incapable of linking to a larger movement?

If there was a weakness in Daniel it was this: even when he knew that mistakes (some of them serious) were being committed by his organisation, he would never stand up and contest the will of the majority. Whatever else, neither Lenin nor Trotsky were reticent in pointing out, when necessary, that what was being proposed was politically unacceptable. I did put this to him once. He smiled but did not reply. Perhaps he thought that in a climate where Marxism was under heavy siege, it was best to be emollient within his organisation. His project was clear: to help create a non-dogmatic, non-religious, non-bullshit Marxism. This was not an easy task in bad times, but as Sebastian Budgen, one of his friends from a younger generation, noted in a moving obituary:

Perhaps most importantly for him, Daniel also doggedly pursued a project of developing Marxist theory by cross-fertilising it with other radical currents (such as those influenced by Pierre Bourdieu and Alain Badiou), and by seeking to transmit in a critical, open but unapologetic manner the wealth of Marxism’s past to a younger generation he hoped would forge a future for it.

The last time I met Daniel, a few years ago in his favourite café in the Latin Quarter, he was in full flow. The disease had not sapped his will to live or think. Politics was his life-blood. We talked about the social unrest in France and whether it would be enough to bring about serious change. He shrugged his shoulders. ‘Perhaps not in our lifetimes, but we carry on fighting. What else is there to do?’ This was the spirit that animated his life as it does this book, making it one of the more intelligent and unrepentant accounts of the French far left.

Tariq Ali's Blog

- Tariq Ali's profile

- 798 followers