Rob Ryser's Blog: excerpts from The Wall at newquoin.com, page 3

December 10, 2011

The Heart of Direct Action

the slow-burning fuel of cool …

NEW YORK — Not long ago, Americans knew cool.

Cool was rebellious and harmonious. It was timeless and new. It was individual and universal.

Everyone bought into being cool. Cool was something nobody could buy. It was only something people could be.

It was hard to be cool. Cool was art and art was cool.

But then Americans forgot cool.

Someone said that if we became consumers, we could ask a lot less of our characters and get a lot more for our appearances.

Someone said that if we would fret less about life and liberty and focus more on the pursuit of happiness we could trade brand awareness for self-awareness.

Or maybe we didn't need someone to tell us what we had already decided. Either way, off we went with the corporations, leaving cool behind in the pursuit of comfort.

We don't need anyone to tell us that there is no peace in comfort, or that there is no purpose in possessions, or that there is no meaning in money. There is restlessness, meaninglessness and despair. We know this. But we are mired too deep in materialism to exit the same easy way that we arrived. Not only are fewer and fewer Americans cool, but fewer and fewer Americans want to be cool.

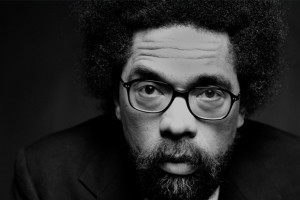

The Princeton philosopher Cornel West in a recent published interview speaks of our market driven society being obsessed with buying and selling and power and pleasure and property. He observes that there is virtually no non-market values that we have anymore and virtually no non-market activity that we do. As a result, he says, love and justice are pushed to the margin. He calls it spiritual malnutrition tied to a moral constipation

The Princeton philosopher Cornel West in a recent published interview speaks of our market driven society being obsessed with buying and selling and power and pleasure and property. He observes that there is virtually no non-market values that we have anymore and virtually no non-market activity that we do. As a result, he says, love and justice are pushed to the margin. He calls it spiritual malnutrition tied to a moral constipationOccupy Wall Street was a cool demonstration.

But if we want more from our culture and more for our country we have to ask more of ourselves like we did when we knew cool. We need to end this charade. We need to stop degrading ourselves as customers and conformists and start thinking of ourselves as creators and custodians of cool.

We need to avoid the tourist traps of culture where art has melted into that mass of homogenized product that the 2011 IAM Conference called "predictable pleasure in commodified form."

Instead we need to find the edges of society and the corners of culture where things are cool. It is in the sacrifices of culture and in the wounds of culture where we find the slow burning fuel of cool that can right society's wrongs and renew people's spirits and ignite cultural awakening.

Instead we need to find the edges of society and the corners of culture where things are cool. It is in the sacrifices of culture and in the wounds of culture where we find the slow burning fuel of cool that can right society's wrongs and renew people's spirits and ignite cultural awakening.For such a renaissance it will take a revolution. And before revolution can begin, people need to revive the sense of who they really are.

There is no one way to do this, of course, but one way to do this is to read serious literary fiction. Serious doesn't mean stiff or stuffy. It means kick-ass. Literary doesn't mean elitist or intellectual. It means heavy-duty art.

Literature that is concerned with revelation and transformation and outlasting fashion is the most profitable kind of reading we can do, because it is committed to an end that endures suffering and death. Literary fiction does not sell out by filling life's cracks with wax or by sugar-coating intractable problems with the fraud of formulas.

Formulas are great when they work in medicine or technology but in art, the uniform application of rules falls as flat as it does in the spiritual life.

There is nothing wrong with reading commercial fiction for entertainment. But if we are hungry, pop fiction won't feed us. Pop feeds on itself. If we are sick and tired and bored, fashion fiction won't renew us. Fashion is not passion.

Our connection to the culture and our purpose in the family and our duty to society and our value as individuals has nothing to do with brand names or prime time laugh tracks or disposable products or mass markets.

Yet we reinforce these superficial attachments each time we look for art in the market.

The best way to change our world is to change ourselves. And one of the most direct ways to change ourselves is to read enduring literature.

The heart of direct action is art.

November 8, 2011

The Orbit of Essential Ideas

Connections in unexpected places: Dostoevsky, the Bible and "Demons" versus Joyce, feminine domination and "Ulysses."

When I decided I was going to force read James Joyce's masterpiece novel Ulysses for the good I thought it would do me, in spite of my distaste for what I had heard about it, I never imagined that it would lead to a website.

But it did.

The Wall and NewQuoin.com are alive today because of a connection where I least expected it.

This surprise find had nothing to do with James Joyce the master, or Ulysses the masterpiece. Instead, I was blown away by a short legal decision printed in the front of the novel by a U.S. District Court judge in Manhattan named Woolsey who had to rule whether the masturbation scene and the fem-dom fantasy in Ulysses constituted pornography – "dirt for dirt's sake" as he put it – and should be banned from sale in America.

What blew me away was Woolsey's statement that he could not judge Ulysses alone on its own without also taking into account the other books that had been written about Ulysses, which had become its satellites.

[image error] offended he was. It was sacrilege to him.

"No novelist has ever explored a man's soul as deeply as Dostoevsky." – E.M. Forster

I will never forget the Headmaster's answer, even though I did not understand it then two decades ago. The Headmaster matter-of-factly said:

"Well, you can't understand Dostoevsky without understanding the Bible."

The student's face fell. His shoulders dropped. That was the end of his inquiry. And if he asked another question the rest of the tour, I didn't hear it. As much as the Bible was reviled by the Soviet state, the novelist Dostoevsky was a man of deep Orthodox faith and a Russian hero. At the time I had neither heard of Dostoevsky nor read the Bible, but I knew the Headmaster was telling the truth.

Since then, I have read the Bible systematically and religiously. And I have read Dostoevsky systematically and religiously. I can't imagine trying to make sense of a master like Dostoevsky or a masterpiece like Demons or Brothers Karamazov without understanding the spiritual concepts and the timeless stories of the Bible.

The Wall and the New Quoin website:

So just as it was necessary for Judge Woolsey to respect the orbit of thought influenced by Joyce's Ulysses in order to decide whether the novel was more artistic than obscene, so too, I thought, it was necessary for kick-ass, street-smart, barely-read, men to understand a little about the orbit of meaning that influences my own novel, "Great Desires for Absent Things," in order to get something more out of it.

And if you look around The Wall and the NewQuoin.com site, you will see criticism, connections and confessions about ideas of identity, origin, destiny, purpose and meaning.

The truth is the orbit of essential ideas is much larger than this Wall or this site; this site represents a small part of a much larger vision that will take years to execute and multiple partners to pull off. I won't begin working on until I am finished with the current novel I am writing.

But perhaps there are enough ideas in orbit for you to be a better judge of "Great Desires for Absent Things."

October 15, 2011

Fear What Is Near

How do you get from the FEAR that says F*CK EVERYTHING AND RUN to the FEAR that says FACE EVERYTHING AND RECOVER?

How do you get from the FEAR that says F*CK EVERYTHING AND RUN to the FEAR that says FACE EVERYTHING AND RECOVER?

The answer is you get there by yourself.

But you don't have to do it alone.

Don't fear death.

Don't fear death.— You are immortal until the purpose of your life is accomplished.

Don't fear emptiness.

— You have a full plate that cannot be finished in one sitting.

Don't fear darkness or evil.

— You have protection from what you cannot see.

Fear instead what is near.

† Near to you – nearer than death

– is an eternal force that cannot die.

† Near to you – nearer than the loneliness you feel

– is an ever-faithful friend who cannot abandon you.

† Near to you – nearer than the terror of suffering that haunts you

– is a sustaining strength that can never be drained by pain.

Nearest to you of all – nearer even than the meaninglessness that mocks you – is the essence of your identity and the substance of your destiny.

Fear the absence of this essence with all the reverence that you attach to the unanswered questions of your existence and you will begin to see the wisdom in the mystery of your being.

September 20, 2011

Life is Relentlessly Moral

Life is mercilessly and unceasingly moral. It comes at us viciously – maliciously – or so we complain. The good life is constantly demanding that we do what is right by others and what is right by ourselves. We confuse the moral consistency that the good life requires with unfairness to us, and with fraud of character in others who pursue righteousness better than us. We say 'Who is moral all the time? Surely someone who does not taste life much.' But who is it who does not taste life much? Surely it is not a real person we deride, but a person we compose out of weak parts. We create someone lesser so that we can be better.

[image error]

II. "See the luck

I've had / Could make a good man turn bad"

We say life comes at us so relentlessly by demanding that we be just and generous and merciful and sacrificial that the good life is picking on us. And so we declare ourselves worn down by undue burden.

In that universal appeal of the victim, we throw up our hands in helplessness about the abuse we have suffered and about the limit that we have reached in suffering it. And we solace ourselves that we are only human. We take the Anna Karenina defense that we cannot be stronger than ourselves. And then, in order that our surrender to the ceaseless challenge to be good might be fashioned into something purposeful, we invoke that American virtue called happiness. And we say 'We only want to be happy.' If only this retreat from righteousness made us happy.

III. The cure and the curse of our conscience

The one defense we have against the onslaught of the moral life is our conscience – a conscience that was a gift to us, ironically, after we made the very first immoral choice in Paradise. We walked out of perfection and into suffering carrying on our backs the heavy knowledge of good and evil.

This knowledge of our conscience tells us with unwavering accuracy what is right and what is wrong. This heart of our soul keeps the beat even when we have lost our way. It tells us so even when we tell ourselves that we know better. In this way our conscience is the balm and the cure.

But this cure is also the cause of the one burden we have that is even greater than the moral life picking on us; our conscience has the uncanny capacity of reminding us of all the times we have chosen the bad over the good. And so we make a snake of the good life.

IV. "Human beings have their great chance in the novel"

— E.M. Forster

Art is our companion in the moral life because great works can ground us in our common origin and guide us in our common destiny. Art reveals and heals. The problem is that so much contemporary art and commercial literature ends where the moral life begins. Formula fiction leaves the reader to imagine that conflict is resolved and crisis is transcended when characters finish happily in marriage or in addiction recovery or in religious conversion.

But the New Quoin novel "Great Desires for Absent Things" begins at the end in order to portray the good life for the unrelenting friend that it is. "Great Desires for Absent Things" begins at the end of a young married man's trial to overcome alcohol addiction and meaninglessness. In doing so, it highlights the war he and other brave characters have to wage to overcome themselves.

In the end, the broken and battle-weary characters in this literary novel are near enough to the wholeness and the peace that comes from embracing mystery to taste it; regardless of their bad record of bad choices, the important moral choice is still the present one that can make old things new.

September 15, 2011

The Idiot Has the Answer

What's the difference between art and entertainment? The answer is in "The Idiot."

What's the difference between art and entertainment? The answer is in "The Idiot."

No one I know confuses the difference between James Bond and Masterpiece Theater. Masterpiece Theater is unadulterated art. James Bond is pure Hollywood formula. I can't wait for the next one.

Yet I am seeing more and more confusion from fellow readers and fellow writers about the difference between literary fiction and commercial fiction. It is not so much that they misunderstand the distinction between a literary masterpiece and a page-turning best-seller but that they misunderstand the difference.

Why do we need these labels? Can't art be entertaining? Can't entertainment reach artistry?

Of course. Plenty of high art like Robert Frost's poetry or Ernest Hemingway's fiction has been a commercial smash. Plenty of popular entertainment has been critically acclaimed. Jazz comes to mind. But let's not allow the exceptions to overrun the obvious: we can find the answer to this question in Dostoevsky's masterpiece, "The Idiot."

In it, Prince Myshkin is explaining to a group of society women how a friend of his had been condemned and had been led out by the guards into the courtyard to be shot, being told he had five minutes to live.

[image error] Prince Myshkin goes on to explain how his condemned friend found in those five minutes all the time he needed and more to think about the things he needed to think about before he died. The friend found to his surprise that his meager five minutes stretched out like a great fabric. The friend had time to think of the people he loved. He had time to think through those final thoughts that he had always carried but not completed. He had time to look around the world of his experience and connect the things he never had the care to assemble before.

And in the final moment of life after he had done everything he needed to do, he caught a glimpse of light glinting off a crucifix in the distance. And the friend recognized with instant conviction that this was the new nature he was going to have after death.

As Prince Myshkin continues the story, he not only has the women captivated but he has the reader totally hooked. Prince Myshkin explains that his friend found himself with so much extra time that he almost begged to be shot. In fact, the friend frightened himself with the thought that if he did not die soon the eternity of minutes left in his life would be so overwhelming that he wouldn't know what to do with himself. It was at this moment that the guards did a mock execution on him, pulling the trigger on an empty cartridge. Then they let Myshkin's friend go free.

"And then?" Asks one of the women. "Did he live counting each moment?"

At this point in the reader's imagination — an imagination that has been informed so faithfully by commercial publishers and popular art — the answer comes 'Why yes, of course the friend did not waste a single moment from that point on!'

But Myshkin responds "Oh no. He didn't live like that at all. He wasted many, many minutes."

And in this response is the difference between art and entertainment. It is the difference between literary fiction and commercial fiction. It is the difference between the ragged edges of an artistic Masterpiece Theater film and the polished formula of a James Bond blockbuster.

Prince Myshkin's response is so striking because it is so lifelike. Life is contradictory and ruthlessly uneven. Life is a war that is never an accomplished fact the way it is depicted by commercial formula publishers of romance novels or Christian fiction.

To suggest that a man who has a religious conversion automatically goes on to live as blamelessly as the Virgin Mary is to make a mockery of authentic spirituality, even if it maximizes the publisher's profit by maximizing the plot's predictability.

To read about the true battles in a young man's second chance life, check out "Great Desires for Absent Things."

What we learn from "The Idiot" is that formula fiction behaves the way we expect life to behave, and that literary fiction behaves the way life behaves — in fits and visions and violations.

Commercial fiction caters to the times so that it can cash in on fashion; literary fiction plays to the ages so that we might have treasure at the end of this journey.

August 20, 2011

The Dignity of Indelibility

What we caution about tattoos is the same appeal people make who get them.

What we caution about tattoos is the same appeal people make who get them. We say: "We wouldn't care if it wasn't permanent."

And the people who get tattooed say "We wouldn't care if it wasn't permanent."

Check it out. We understand the appeal of permanence. We understand the dignity of indelibility.

We understand all about indelibility because we understand all about sacraments. And maybe if sacraments were not such a big part of our lives, we would go out and get tattooed, too.

A sacrament is an outward sign of an invisible reality – on the outside it may look like a thin wafer, but in reality it is the bread of life.

A sacrament is the sign with power; it brings about what it signifies – baptismal water symbolizes purity and it also purifies the soul. Tattoos can often be outward signs of an invisible reality, too.

Tattoos can often be outward signs of an invisible reality, too.

We understand the appeal of putting something beautiful or something powerful or something provocative on our body permanently to show the world that we have something beneath our skin that is abiding and original.

And if people who get tattoos are uniting themselves with this spirit of permanence then this is something deep in common that we share.

More and more in our society as break ups and blown vows pile up evidence that love can't last, we protect ourselves from disappointment and rejection and suffering by becoming cynics who say promises are made to be broken. So it is an act of revolution as much as an act of fashion to put on a tattoo that says:

So it is an act of revolution as much as an act of fashion to put on a tattoo that says:

'Yes I know this thing is permanent, but I know who I am, and that is the first step to knowing where I'm going and why I'm here.'

We are not so certain that tattooing CHOSEN1 across one's shoulders constitutes an outward sign of an inward reality. We are not talking about vanity tats.

But we are saying we want to encourage integrity. We want to encourage fidelity. We want to encourage conviction.

Because ultimately, we want to encourage mission and service and radical love.

And if a tattoo helps remind people of their enduring and eternal inward reality, then maybe it is a sign with power.

August 16, 2011

Hollywood and Baseball

I have another real life example of that line from "Great Desires for Absent Things" that we despise in others most what we despise in ourselves first.

It's a confession about Hollywood. But first, I have a parable about baseball to share that will help the whole thing translate.

There is a woman named Sloan. The closest people in her life adore baseball so much that they always want to talk about it with her. And Sloan despises baseball, even though she goes ahead and talks about it with these very close people in her life.

To Sloan, baseball is a diversion from important things. To Sloan, baseball produces false images of success and worth. Sloan cannot readily say this to her loved ones because it would be too confrontational. She is a person who needs to be liked. She needs to be clever about how she offends people.

So instead, Sloan's contribution to these conversations is bringing up the gambling-ruined baseball legend Pete Rose when he is in the news. Or she brings up the notoriously rich and ever controversial Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, even though the man is dead. Or Sloan soaks in the details about the scandal-of-the-day involving superstar homerun hitter Alex Rodriguez.

She does this not to point out what evil she thinks of these baseball lions, but what evil the world thinks of them. See? Clever.

It follows that Sloan does not pay attention to any other kind of baseball news — and certainly not positive baseball news. It goes without saying: she is only interested in negative baseball news to cover her bias.

HERE'S THE POINT, it seems to me: Sloan does not have to like baseball just because her loved ones do. And Sloan does not have to confess how she despises baseball either. But what she does have to do is be honest with herself about a few things.

She has to realize herself that when she focuses on baseball news, she is only focusing on negative news.

She has to realize herself that negative news is only part of the baseball news spectrum, even if some of the negativity seems to condemn baseball according to her views.

She has to realize that she ignores positive baseball news precisely to stack the argument in her favor.

When Sloan is honest about these things, she sees that she is not merely beating up on baseball because the silly sport deserves it, but that she is actually being unfair to baseball and therefore unjust.

Sloan does not owe this honesty to anyone but to herself. But if she is not honest with herself, she is the only one who she is fooling. Every time Sloan brings up Pete Rose the crook and George Steinbrenner the cheater and Alex Rodriguez the fraud, her loved ones know what she is doing. She is telling them nothing about baseball and everything about her bias.

It's the crookedness and the cheating and the fraudulence within Sloan that she despises.

NOW TO MY CONFESSION ABOUT HOLLYWOOD

NOW TO MY CONFESSION ABOUT HOLLYWOOD I used to think that I was better than everyone in Hollywood. This was a deeply rooted conceit of mine right after I got sober.

I had never admitted it to anyone, of course, and for many years I refused to admit it to myself — because I knew how maniacal it was. On the one hand I was calling everyone in Hollywood superficial, as if such a thing was possible. On the other hand, I was holding myself up as superior to them all. One thing I learned when I put down the drink is that I'm not even better than myself. The higher I am in my own estimation, the less I measure up to my own standard.

And honestly, if I was better than Hollywood, would I really need to pronounce my superiority?

Yet on I went focusing on negative Hollywood news and ignoring positive news about stars and movies, the same way Sloan did with baseball. The same way people do with lots of things from politics to religion.

I am the one who is superficial. I am the one who is vain. I am the one who is material and overly concerned with my image and my popularity. I know this because I despise the things in other people most that I despise in myself.

I have worked to correct this. I look for good news from Hollywood. It's there. I try to exercise compassion when Hollywood royalty suffers. I try not to fly to each scandal that breaks as a pretext to stab the industry anew.

But of course I am still very biased. I am still very much possessed with the things that I despise. It drives me nuts not to be able to make more progress on it. But the fact that I cannot make more progress makes me a little more forgiving of the people I love who do the same thing with religion.

July 25, 2011

Open Market Censorship

No one can disparage commercial publishers for printing literature that is going to make their profit margin.

No one can disparage commercial publishers for printing literature that is going to make their profit margin.

But commercial publishers don't always know which literature is going to make them money because readers are always looking for something different, and because readers don't always know what they like until they read it.

So publishers decide what is commercially viable based on formulas of fiction that sell well in market niches, and based on past best sellers that cater to the widest audience possible.

This has the effect of producing a homogenized disposable literature that bars non-commercial literature, especially enduring literature with artistic integrity.

Commercial publishers have printed great stories. But today's publishers are committed to less art and more quick fiction even though readers are dwindling — something akin to sending the bus to stops where no one is waiting anymore.

So instead of appealing to new readers and trying to win back traditional fiction readers with artistic alternatives to pop reading and throwaway books, corporate publishers continue to send the formula fiction bus to desolate stops.

This is reflected even in the smaller presses that distinguish themselves from corporations by promoting "books that require a brain." Small presses are in publishing for the money, too, so that these little guys conspire more than they compete with the conglomerates to censor worthy fiction from print.

The result is that just about all American-published fiction now is market-driven and pop-culture referencing.

The problem with quick fiction is we inevitably feel the publisher's hand in our pocket. We get the feeling not so much of being robbed or ripped off but of being reduced. We are being treated not like the person who the novel was written for, but the consumer who the publisher targeted.

No wonder no one is waiting for that bus anymore.

June 24, 2011

The Wrestler

In my early teens, my father would drive my brother and me on those bleak winter nights to a wrestling club in Chicago that wound up producing at least two state champions.

In my early teens, my father would drive my brother and me on those bleak winter nights to a wrestling club in Chicago that wound up producing at least two state champions.One of those future champions was a kid named Ed Giese who won the state title I believe three times in a row before going to the University of Minnesota and finding out how tough the rest of the Midwest wrestles. And I made my name in that club by wrestling Ed even in practice.

"Know what your problem is, Ryser?" The coach called me out during one of those lulls in practice were everyone is too winded to move. "In here you wrestle, but at the meets you act like you're off the streets.

The coach was right.

The difference between my good performance in practice against a championship competitor like Ed and my underachieving performance during those interminable weekend wrestling tournaments against no-name opponents really was a waste of my training.

Today I know why I was a completely different wrestler in practice than in tournament competition. I know why I was underachieving.

Winning on the mat never had a claim on my heart.

Nothing had a claim on my heart then.

II

All this came back to me on my way to teach in the Bronx. And it made me wonder how far I really have come since I've grown up.

My life has turned around so drastically and so remarkably over the last 17 years of sobriety and faith because I have more grace than I can handle. This is a good thing. And yet in spite of all my "training" in the second-chance life, I still battle like an untrained street fighter.

I mean, in spite of all the lessons I have learned from the classics and the spiritual direction in my life, and from my love relationships and my kids and my students and my colleagues at the newspaper, I fight my battles like that same green kid in Chicago who's going through everything for the first time.

I don't say 'I love you' or 'I'm sorry' any more than I did when I was a kid. I judge on appearance. I'm quick to condemn. I withhold charity and forgiveness and grumble when I'm feeling sorry for myself that my limousine to the easy life is late in arriving.

The only difference between my "wrestling" now and then is that now I care about the outcome.

Faith has a claim on my heart. Meaning is everything to me.

So it bothered me on the way to the Bronx to think that being saved and sober hasn't changed me much at all.

III

Now it occurs to me — slowly and not quite completely — that when it comes to the big battles we fight with ourselves, the important thing is not to win them. The important thing is not the successful outcome but the faithful effort.

Jacob didn't beat the angel he wrestled in Genesis. The angel let him go easy with an injury on the hip. Jacob walked away with a limp.

And yet Jacob was exalted and rewarded with a new name from God for his effort. Why? What did Jacob do that was so eternal? He fought with everything he had, right? It was his effort — the great spirit he tapped from his faith — that God recognized as good and worthy of imitation.

The most important thing when it comes to our most important battles is to put our whole soul into the fight, even if we think the opponent is too big. Even if we're just fighting like we are off the streets.

My whole adolescence and early adulthood was spent shying away from the big questions of existence and backing down from the challenges that death and morality posed to my idea of life. I didn't think I was big enough to wrestle with God. I didn't think I was brave enough.

The good news is when we battle, we win. We find in our exertion against huge odds a surprising inner strength. We find in our exhaustion a remarkable spring of energy. We find in our injuries an unexpected resilience that feels like redemption, even though we feel the wound.

This is what happens when divine will and free will meet on earth. They battle. They wrestle. This is the premise of a new novel, "Great Desires for Absent Things."

And just when we think we've lost, we realize that we have gained eternity.

Genesis

My great-grandfather immigrated from Switzerland to New York. He moved his family to Chicago where he drank on the streets to the scorn of the crowd.

My grandfather swore off the booze. He moved his family to Indiana, where he became a man of God.

My father swore off God. He moved his family to Chicago and became a man of might.

I swore off might. I swore off God. And I drank on the streets to the scorn of the crowd.

BUT THEN, by the grace of the God of my fathers, I swore off the booze. I moved to New York, and I became a man of letters.

And in those letters, which were already formed, was the place of my origin, the passion of my purpose and the promise of my destiny.

excerpts from The Wall at newquoin.com

Whether it’s for the criticism, the confessions or the connections about reading, writing and the life of meaning, The Wall is where we discover what we know about ou Revival | Revolution | Renaissance

Whether it’s for the criticism, the confessions or the connections about reading, writing and the life of meaning, The Wall is where we discover what we know about ourselves and what we know about our world by exploring the questions of origin and destiny and identity and purpose.

The Wall is a place for transformation as much as a place for information. It is also a place for your contribution. ...more

- Rob Ryser's profile

- 1 follower