Rob Ryser's Blog: excerpts from The Wall at newquoin.com, page 2

September 14, 2012

Our Need for Meaning

It’s the dawn of autumn, and everywhere people are telling us not to over think.

So let’s think about that for a minute.

After all, the only thing to gain from over thinking is understanding.

There is nothing wrong with advice that tells us not to complicate our relationships, or advice that tells us not to procrastinate our priorities, or advice that tells us not to lose the point about what’s important for the sake of debate.

It’s always good to be reminded to keep it simple.

Keeping it simple is a spiritual principle.

But telling us not to over think in an age when most of us have to admit that we do not spend enough time pondering deeply what eludes us hardly shows us how to find the simplicity and the clarity that we are looking for in great examples of wisdom such charity begins at home, or forgive and you will be forgiven.

Telling us not to over think something doesn’t show us how to enjoy the ease and the simplicity that we all want.

Telling us not to over think something suggests that the hard part is letting go of all the clutter we love to adorn our thoughts with, enabling us to reach the promised land of wisdom simply by not trying too hard to get there.

The idea that something rare and valuable can be discovered by simply not trying too hard to find it as untrue as the idea that the heart is made stronger by not going overboard with love, or that a mind is made wiser by not going overboard with learning or that a body is made healthier by not going overboard with nutrition and exercise.

Like a lot of conventional wisdom, the “don’t over think it” campaign tickles the ear more than it rings true.

All we need to do is test its validity against another piece of conventional wisdom such as no pain, no gain to see that the “don’t over think it” advice is simply another one of our societal coupons with no face value that we give to people to demonstrate that we know something when we don’t.

There are examples every day starting with the poor soul hanging off off the Tappan Zee Bridge where saying “don’t over think it” would be the worst thing to say.

We wouldn’t say it so someone contemplating marriage or abortion or military service or a religious vocation, because deep down we believe that decisions with life-changing consequences need to be thought over deliberately.

And like other conventional wisdom that we spread without enough thought about its veracity such as “everything is relative,” or “all things in moderation,” there is a morbid philosophical agenda behind the “don’t over think it” campaign.

What is really being said is that there is nothing worth thinking about so hard that it hurts, because there is no meaning in life anyway.

This of course is the great lie of nihilism. It is the great scam of materialism. It is the great schism of capitalism.

II.

The soul knows what the mind needs, even if the mind does not have the vocabulary to ask for it, even if the mind does not have the light to confess what it must have to live.

When I was young man – no longer a teenager but hardly an adult – I was beside myself in a crazy display of passion one night in the loft apartment my mother bought across the street from where we lived before the divorce.

My two best friends Jim and Dubbs were with me, trying valiantly to understand what I was saying through my tears about wanting to do something important and wanting to think important thoughts and wanting to plan so that the three of us would not get lost doing nothing.

I wanted them to promise that we would figure out something to do together so that no matter what, we would make a difference.

Jim and Dubbs were as patient as two good friends could be.

But they didn’t understand what I was saying. They didn’t understand what I was saying because I didn’t know how to express what I was feeling. It’s not only that I didn’t have the vocabulary of meaning that I might have had if I had been raised in the church, or if I had read good literature in school.

It was much deeper than that.

The fact is I had no confidence that there was any meaning. I thought meaning was something that had to be created, and it worried me to death that I didn’t know how to do that. It frightened the light out of me that I didn’t know where to start.

Jim had a plan. And the plan was to get drunk and go from there. We were already drunk, but his plan was the best one we had.

Everybody today would be proud of us. We didn’t over think it. We over drinked it.

It worked so well that night that I did the same thing every night for the next decade. And I ended up exactly where people end up who over drink and don’t over think.

III.

The dialogue of meaning is not a dialogue with the rest of the world.

The world will tell you that the meaning of life is to live it. But the meaning of life is not to live it. The nature of life is to live it.

Slugs and skunk weed and single cell amoeba all live life, and they never make the mistake of over thinking it.

The world will tell you that meaning is what you make of it. But meaning isn’t what we make of it. We are not the creators of meaning any more than we are the creators of bugs or weeds or bacteria.

If anything, we are the destroyers of meaning. But the world won’t tell you that.

The world will tell you that meaning is nothing. But that is not meaning. That’s nihilism.

The world will tell you that meaning is anything. But that’s not meaning. That’s relativism.

Everyone who has ever suffered knows that meaning is something.

Everyone who has ever hoped knows that meaning is everything.

On a good day, the world will tell you that meaning is love. And this is not all wrong. It just isn’t fully true.

Even if you are a person who is always engaged with others and who is always engaged in action, those love relationships and those service activities are not where meaning is defined. They are where meaning is experienced or expressed, but not where meaning is understood.

God forbid a person close to you dies. Meaning doesn’t die. Meaning endures.

IV.

In November a movie based on the Tolstoy masterpiece “Anna Karenina” is coming to American theaters.

It would be a strange thing in these times to ask people to read the 1,300-page novel instead of watching the 130-minute movie.

It would also be hypocritical. I was never one to read “Tess of the d’Urbervilles” when I could watch Nastassja Kinski in the theater.

But my soul knew what my mind wanted, even if my body ruled my mind.

In those days of my early-life crisis, I used to tell Jim that I wanted to go to Russia, although I had no idea why I wanted to go.

Jimmy got so tired of hearing my threats to leave for the enemy country that he finally said “Why? So you can wait in line for toilet paper?”

I couldn’t tell him why then, because I didn’t read then.

But I have read since then. And I can answer with the reason now: Russia is where they write novels about meaning.

I am not going to spoil anyone’s enjoyment of “Anna Karenina” by revealing that the title character at the end throws herself under a train to punish her lover Vronsky.

This doesn’t spoil the ending because there is much more to the ending than the death of the title character – even if the movie version doesn’t know it.

There is a character named Levin, and the only thing more dramatic and breathtaking than the death of the gorgeous and the tortured Anna Karenina is the conversion of Levin.

He says all his life as a believer in the scientific process and in scientific progress he thought as hard as he could. And as hard as he thought he could make no sense of meaning.

“I was astonished … that I could not discover the meaning of life, the meaning of my impulses and yearnings.”

Levin comes to the following conclusion, not as a result of not over thinking it, but as a result of refusing to give up thinking about it.

“Now I say I know the meaning of my life: ‘To live for God, for my soul.’ And this meaning, in spite of its clearness, is mysterious and marvelous. Such indeed is the meaning of everything existing.”

V.

If we think enough about it, we know that meaning is connected to pain and suffering and sacrifice. And that is enough to make us not think about it.

If we think enough about it, we know that meaning is something that belongs to us that we nonetheless misplace a lot and have a hard time finding. And that is enough to make us say it is not worth the search.

If we think enough about it, we know that meaning is transportation that takes us on unfamiliar travels when we are much more comfortable being grounded. And that is enough to make us say we’re not moving.

But we also have to admit that our search for the happiness that will ballast the pain and the loss and the change in our lives is ultimately a search for meaning.

So the answer we get when we ask the world to define the meaning of life is the answer we get when we ask the world to define who our neighbor is.

We get every good-sounding answer from the world except the correct one, because the answer is already written on our hearts, and it offends our sense of autonomy that the writing is someone else’s.

We know before we ask the question that everyone is our neighbor because every life has meaning.

Deep down we believe this because meaning is believing.

It’s why we bolt the signs to the beams of the bridges in New York next to the suicide hotlines that read “Life is Worth Living.”

We have always believed this, even though we have never trusted it.

We’ve never trusted it because we know how much life hurts.

The meaning we need to believe in is not that life is worth living for other people, but that our life is worth living – not just today, but every day of every season.

For that belief it takes a great faith in eternity where souls live happily ever after.

And there is no amount of over thinking that can spoil that.

August 5, 2012

The Sweetness of Suffering

NEW YORK – It is a broken life.

Love is broken by death.

Faith is broken by injustice.

Hope is smashed by unhappiness.

And pain reigns.

It’s true that some people have had the great blessing to come from homes where their sense of their origin was developed and where their picture of destiny took shape because being at home meant a connection to something greater than themselves.

But everyone knows people who have never known such a home.

It’s true that some people have had the great blessing to be inspired by teachers who shaped their ideas of identity and who filled them with a feeling of purpose because learning was grounded in service values.

But we all know people who have never known such teachers.

And it is true that some people have had the great blessing of being raised out of ruin through redemption and being rescued out of slavery by grace because angels in the trenches have brought the power of heaven down to earth.

But this is a broken world where people are so forsaken and so abused and so systematically disenchanted that it doesn’t surprise us that they are in pieces.

It does not surprise us that we are in pieces, either.

It only surprises us that we suffer.

We are surprised how often we suffer.

We are surprised how deeply we suffer.

We are surprised how singularly we suffer.

But we should not be surprised by our suffering.

II.

Suffering can make us feel alone and demoralized.

It can isolate us from the hope of relief, and it can trash our deepest held belief.

As a result, we don’t treat our neighbors with charity, and our neighbors don’t treat us with mercy.

So we go through life withholding from others what we want most from others.

But if we read well we will see that we are not the only ones who suffer.

That insight can become a great source of encouragement and nourishment.

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive.”

- James Baldwin

We can be encouraged by suffering because it makes us truly human.

Suffering teaches us that we are not unique.

This a good thing.

Once we realize we are not unique we see that we are not alone.

Once we see we are not alone, new sources of power present themselves to us, and we see solutions for our most puzzling problems.

We begin to see that we are puzzles made of pieces that fit together to make a beautiful whole, and we stop despairing so much about being broken.

Being in pieces makes it easier to see the parts of us that would otherwise be hidden in the whole.

We can also be nourished by suffering.

But first a story.

III.

For years I have taught a Toni Morrison novel called “The Bluest Eye.” And in every class I teach it I make sure to spend time on a simple three-word declaration in the novel that says “pain is sweet.”

It is puzzling statement in any context, but it is especially puzzling in this novel, where the title character is a black teenage girl in the racist South whose suffering at the hands of great hate is matched only by her own self loathing.

For this tortured title character, pain is most certainly not sweet. Her pain is poison. Pain drives the little suffering heroine out of her mind.

And yet the narrator of the novel, who is also a teenage girl, and also black, and also suffering great hate in the racist South, insists on making this puzzling declaration about pain being sweet.

The statement appears in a quiet scene in the beginning of the novel where the narrator girl is listening to her mother wash the dishes and sing the blues. The fuller statement is “…the words left me with a conviction that pain was not only endurable, it was sweet.”

I always ask the class for a show of hands for people who agree that pain is sweet. Inevitably, one or two hands go up with me. Inevitably, those who raise their hand are among my non-traditional undergraduate students who have kids, careers, and other substantial adult experience.

Whenever I see a hand go up with me, I know it is someone who has lived fully enough to profess something counter-intuitive.

Then w

e try to define what Toni Morrison is saying.

e try to define what Toni Morrison is saying. Sometimes by way of explanation we use childbirth as an example of a real life event where pain is truly pain and where sweetness is truly sweet.

In other classes we have talked about how the statement cannot make sense unless it is considered in the spiritual realm, which of course it must be, since the novel goes much deeper than the merely physical things people suffer through the senses.

Wherever the discussion ends, we always acknowledge that this is a heavy-duty existential statement that is more evasive than obvious.

Sweetness is a beautiful thing. Pain is a God-awful thing. How could a God-awful thing be beautiful? It occurs to me for the first time as I write this that the answer is also more evasive than obvious.

It occurs to me for the first time as I write this that the answer is also more evasive than obvious.

I’m reminded of a great teacher who is famous for saying to those following him: “let those with ears hear” and “let those with eyes see.”

So in the spirit of that teacher I say that suffering is sweet – let those with tongues taste.

IV.

I hope it is clear that we are not talking about chronic pain, although it needs to be said that we don’t do enough as a nation with palliative care. We spend so much time developing doctors and so much money developing pain killers you would think modern medicine would be better equipped to manage debilitating pain, especially in chronic cases, and at the end of life.

And I hope it is clear that we are not talking about nerve pain. If we were, this would be a commercial for a nerve pain killer, with the requisite list of side effects.

But we are not talking about nerve pain. We are talking about suffering – the pain that has reigned in our souls since the age of reason.

And the source of that suffering is the knowledge of certain death.

The most painful part of suffering is its capacity to render all good for naught.

In fact, the strongest argument in the world that God doesn’t exist is the existence of suffering.

But the existence of suffering does not prove that God is dead. The existence of suffering proves free will is alive.

We are broken people who did not bring ourselves into this broken world and yet we are responsible for fixing it.

The only chance we have to fix a problem that is bigger than us is to find a solution that is bigger than the problem.

If death is the problem, resurrection is the solution.

It takes a revolution in thinking, and a renaissance of action, and a revival of love to see death as a door to something more, where life is unbroken, because it never ends.

V.

It is natural to run from suffering. People who run from suffering are not cowards. They are human.

It is natural to fight suffering. People who fight suffering are brave.

But when a master teacher reclined on a hill to tell the multitudes how to suffer, he did not tell people to run from it. He did not tell them to fight it.

He told them to feed on it.

The message of the Beatitudes is that God is with us in our suffering, and if we can allow that presence to abide in us then we are blessed.

We are blessed with meaning where there would otherwise be meaninglessness because Jesus suffered.

We are blessed with compassion where otherwise there would be hardness of heart because Jesus gave up his life for us.

We are blessed with understanding and fullness and courage where there would otherwise be disillusionment and emptiness and paralyzing fear because Jesus is the fulfillment of God’s promise of salvation.

In this way suffering is redemptive.

This seems shocking because the world does not see suffering as redemptive.

The world sees suffering as destructive. And suffering is destructive when it hardens us.

Suffering hardens us when we look for victory over it. We are not built to outrun it. We are not equipped to out-muscle it. We feel defeated every time we try.

The way to suffer is not to strive for victory over it but to strive for faithfulness by finding ourselves in our wounds and by offering ourselves to each other.

July 7, 2012

Believing in the Unseen

FAITH, STRIFE AND THE HIDDEN LIFE

CROSS RIVER — This was originally going to be a webpiece about suffering.

It was going to be about how inescapable suffering is when we pursue meaning. It was going to be about how integral suffering is when we pursue happiness. It was going to be about how suffering can be redemptive when we pursue peace.

But I realized that would never work.

Suffering is unbearable without faith. And to date, I have written nothing about faith.

It is my fault for relying on my experience to dictate the order of ideas that I’m putting on this Wall instead of relying on design. The problem with using my experience as a guide is I burned such a destructive path into adulthood that I had to beg spare parts from strangers to put myself back together. I can’t commend my example to anyone, and my mind still renders things of meaning out of order.

As a result, the great suffering piece is on hold so that a little faith piece can be told.

It has to be a little piece, because faith is the domain of masters and masterpieces.

A master would say that faith is the bridge between prayer and love:

“The fruit of silence is prayer, the fruit of prayer is faith, the fruit of faith is love, the fruit of love is service, the fruit of service is peace.” (Mother Teresa)

A masterpiece would say that faith is the union of reason and revelation:

“Faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.”

(Hebrews, 11:1, NASB)

I don’t have any museum-quality definitions of faith to share, although I have to say that the beauty and order we revere most must not be confined to roped-off pedestal displays, or restricted to the care of curators with white gloves.

I don’t have any museum-quality definitions of faith to share, although I have to say that the beauty and order we revere most must not be confined to roped-off pedestal displays, or restricted to the care of curators with white gloves.The higher the ideal the more necessary it is to carry it in our hearts and wear it on the streets, even though there is always the risk of it being broken or soiled out in the open, because everyone’s hands are rough and everyone’s hands are dirty.

My definition of faith is a street definition, based on my experience. And my experience is that faith is so much a part of everyday life that we don’t recognize it.

If we would only recognize the disguises of faith, we could tap into faith’s power to overcome suffering, and draw the inspiration from faith to serve others.

Before I break faith down, I hope it is clear that I am not talking about faith in ourselves as though all I mean is self-confidence. I am not talking about faith in another person as though all I mean is trusting someone we love. I am not talking about faith as merely supporting a person we admire.

“I don’t believe in no car /

“I don’t believe in no car /

I don’t believe in General Motors /

I don’t believe in the President /

or the League of Women Voters /

I don’t believe in these things /

All these things might fail /

I don’t believe it’s going to snow /

it might sleet, rain or hail”

None of these examples that pass for faith supply enough power to accomplish what we cannot do for ourselves. In fact, I would make the argument that faith in myself and faith in other people fed my existential crisis as a teenager and as a man of 20 more than it diminished it, because the object of my faith was so fallible.

What we are really talking about is a belief in something greater than ourselves, and I hope we can agree that while it may not be possible for everyone to unite theologically about what the proper focus of our faith should be, it is entirely possible for everyone to unite existentially.

Simply said, we are creatures of what we cannot see.

As a result, we believe in the unseen.

E.M. Forster in his unparalleled criticism “Aspects of the Novel” observes that “We live between two darknesses … starting life with an experience we forget and ending it with the anticipation of something we cannot understand.”

Forster goes on to say that what is fictitious in serious fiction is the way readers are able to witness thoughts of characters that are hidden in real life. This is part of why he says “Human beings have their great chance in the novel.”

It is this secret life – the one that is hidden, for which no external evidence exists – where we have the most investment, and therefore where we have the most faith. It makes sense, then, that what we can see in life is made from what we cannot see.

Forster suggests that we really only experience five things of true consequence in life: birth, food, love, sleep and death.

I suggest that we do all of these things with faith. If we look at each of these five areas, maybe we can see how faith is as near to us as our breathing and as dear to us as our dreaming.

FAITH IS LIKE BIRTH – It is pure, whole and wonderfully made from parts that are wounded and divided.

Like faith, the triumph of birth makes a soul forget the trial of pain.

It is new enough to set the clock back to zero, and important enough to make time start over.

It is the perfect completion of countless expectations.

Just as we are reborn when we renew our hope, so it is with faith. We are able to renew our hope when we fear nothing from death because we expect everything from rebirth.

Birth is the first reason for Faith. Faith is renewal.

FAITH IS LIKE FOOD – It is enjoyable as a matter of the individual palate and it is required regardless of personal taste.

It satisfies the most basic hunger for sustenance and the most advanced appetite for abundance.

It satisfies the most basic hunger for sustenance and the most advanced appetite for abundance.Food is sufficient to fill the stomach for a day, but the next day it needs to fill the stomach again if the body is to live.

It can be monotonous in the relentless routine of eating it and yet food never loses its power to be a singular delight.

Food brings people together around the table to share their gratitude and to renew their hope.

Food is the second reason for faith. Faith is fuel.

FAITH IS LIKE LOVE – It is the union that binds people together for life.

Just as in love when people say that they want proof before they commit, so it is with faith. But people never have proof of another person’s love – not in the scientific sense that proof is used. Instead people have a preponderance of evidence of another person’s love. Sacrifice. Unconditional fidelity. Forgiveness. This is evidence of love. So it is with faith.

Love endures everything. Love outlasts death. So it is with faith.

Love is the third reason for faith. Faith lasts forever.

FAITH IS LIKE SLEEP – It is the closest thing in life to oblivion.

Just as Thoreau says that we awake in the morning to a higher life than we fell asleep from, so it is with faith.

Just as Thoreau says that we awake in the morning to a higher life than we fell asleep from, so it is with faith.It is the universal connection with the unconscious.

It is the life of the spirit without the body.

Like faith, sleep is the concrete need for the ethereal.

It is the need for the solace of solitude.

Just as dreams make the surreal seem grounded and the grounded seem surreal, so it is with faith.

Sleep is the fourth reason for faith. Faith is mystery.

FAITH IS LIKE DEATH – It is inescapable.

It is unexplainable.

It is as familiar to us as our own soul and yet it remains unknown.

It can often seem opposed to the life of matter and sight, and yet, more than anything else, it gives meaning to being.

We avoid it. We hide from it. We fight it. It seems like the enemy of our autonomy, but it forces us to decide who we really are and it allows us to see the value in others.

It makes eternity urgent.

It is a cold and empty place in the midst of mourning.

It makes life worth living. It makes suffering worth bearing. It makes service worth giving.

It is the great leveler of wrong.

It is deep sadness set to song.

Death is the fifth reason for faith. It is the guarantee of peace.

June 8, 2012

The American Problem

I used to think isolation and ignorance were my own unique problems.

Growing up in Chicago without faith and without a foundation in reading, it didn’t occur to me that other people might have the same problems with identity and destiny.

Living in London at 19, I heard it said a lot that isolation and ignorance were American problems. That opened my eyes a little, but I never connected that to my own alcoholism or to my own nihilism.

So the other day I was wondering how best to explain the dynamic relationship between serious literature and meaning that has been such a gift to me in my second chance at life. I came across a newspaper article from 2009 that I had clipped about the chairman of the Nobel Prize award jury in Stockholm, who called American literature too isolated and too ignorant to be taken seriously.

Specifically, he said American literature was too wrapped up in popular culture to be useful to the rest of the world. You can imagine the outrage that comment provoked from the American publishing establishment. It doesn’t outrage me. But that is not the point.

The point is that suddenly everything that I want to say in this space has fallen into place.

And what I want to say is that isolation and ignorance are art’s problem.

It is art’s job to take on the biggest questions of existence, so that we feel more solidarity with humanity, and so that we feel more enlightened about eternity.

It is art’s job to deepen what we know about ourselves and to expand what we know about our world.

It is art’s job to do for us what we cannot do for ourselves – otherwise why bother with novels or museums or symphonies at all?

Having said that, there are two huge problems for us.

FIRST, it is bad enough when a non-reader like me refuses to go to art for answers – either because I don’t know that art has answers, or more likely because I am too lazy or too proud. Either way I suffer and die in the shadow of the solution.

SECOND, it is much worse if I go to art and find that the meaning isn’t there because artists aren’t doing good art. If the art written by Americans is not solving the big problems of life by awakening readers, then the art written by Americans is solving lesser problems of boredom or paying the rent. And our culture suffers and dies in the darkness.

My experience is that isolation and ignorance are my own problems as long as I never read. But isolation and ignorance are America’s problem as long as American artists write for money instead of meaning.

If American art does its job and takes on the problem of meaning in this broken world full of souls who know death is coming, then the burden of existence is lightened, and people can love in the midst of suffering.

If American art does its job and takes on the problem of meaning in this broken world full of souls who know death is coming, then the burden of existence is lightened, and people can love in the midst of suffering.But if art cannot bring us into communion with each other, so that we discover our uniqueness in unity, if art cannot inform our conscience with the wisdom to put others first, to love justice and walk humbly, then what we are left with is entertainment.

God knows entertainment is a good thing. God knows that entertainment is one thing we don’t have a shortage of in America. But there are great experiences in fine art that more exhilarating and more enchanting than entertainment.

Reading great novels has made me the radical I have always wanted to be. Great novels have given me that buzzed rush of invincibility I used to get only during the first few years of drinking, with the difference that the literary highs linger longer in my interior and create this energetic appetite to do something.

Great novels make me shake my head in awe. They make me write things down that I want to pass down to my grand kids. They make me feel as proud and as privileged to read them as a VIP. But they are so much more important than that, because they are much more intimate than that.

The Manhattan writer John Herman who was my editor while I was writing “Great Desires for Absent Things” has compared reading the classics as second only to the pleasures of the body when it is young, except less fleeting.

The comparison never occurred to me quite like that, but I have to admit it’s true. There truly is something sensationally personal and uniquely fulfilling about connecting with great literature.

Reading a classic really is an up close relationship across time and space, and the question becomes what kind of a relationship do you have with what you read? Is it worthy of you?

I am not here to tell you that I discovered meaning in life only because I picked up Augustine or Dante or Dostoevsky. There is more to my story than the fact that I went from an ether major and a nothing-artist who never read and never wrote but told everyone I was a writer to a faith agent who writes every day and is always reading a masterpiece or a classic, even if it takes me a year or more to finish one.

During those desperately dark nights when I never wanted to see the morning, I knew that I wanted meaning and I knew I could not get it. So I told myself that meaning was unimportant because it was boring, and I lived through the body.

But the truth is truth is meaning is everything. Without meaning, even living through the body is no good. Without meaning nothing is good. Nothing is endurable. Love is no good without meaning. What good is it to love someone who is going to die suddenly or eventually? What good is the greatest feeling in the world when it hurts you so bad you would rather be dead? Love is no good at all without meaning.

My way to meaning was bloody and unclean because I thought suffering was the enemy and I was willing to die fighting it.

Let me do a better job of being honest: I did not fight valiantly against suffering. I ran from it and then surrendered and then tried to die. My surrender was refused. My death was postponed.

What I am here to tell you is you don’t have to kill yourself looking for meaning. You can find it in the best novels that have ever been written. Or you can try some of the recent masters whose work after their death continues to stand up. You might even try living writers whose only connection to the masters and to the masterpieces is a burning desire to write literary fiction they way they did.

What I am here to tell you is you don’t have to kill yourself looking for meaning. You can find it in the best novels that have ever been written. Or you can try some of the recent masters whose work after their death continues to stand up. You might even try living writers whose only connection to the masters and to the masterpieces is a burning desire to write literary fiction they way they did.If you have a good approach, there is enough meaning in the right literary novel to make up for a lifetime of squandering and wandering. I am not speaking of my definition of meaning or the church’s definition of meaning or the culture’s definition of meaning but your own definition of meaning that you have always understood to be the most important thing you know.

Meaning isn’t what the novel fills you with but what the novel brings out in you.

May 5, 2012

The Five Fingers of Existence

NEW YORK — Nothing is like the middle finger in America.

In one impulsive flip it accomplishes more strategy in a situation than a think tank could ever devise.

In the dirt of the moment it dresses insolence and intolerance with more dignity than any righteousness it’s raised against.

And in the hollows of a muted mind, this lone silent digit speaks with such authority and with such authenticity that no translation can master it.

It’s autonomy.

It’s identity.

And yet, for everything that the middle finger does to identify us as Americans, the middle finger does more to isolate us as Americans.

This is not an intractable problem.

We simply need to recognize that the middle finger is rooted in the hand.

Just as there is more to the hand than a middle finger, there is more to identity than individualism.

A soldier who battles alone will have more sorrow and less consolation than a soldier who fights with the unit.

It makes sense that the benefits of connections are superior to the benefits of independence, even if being connected to others means cutting certain ties to self rule.

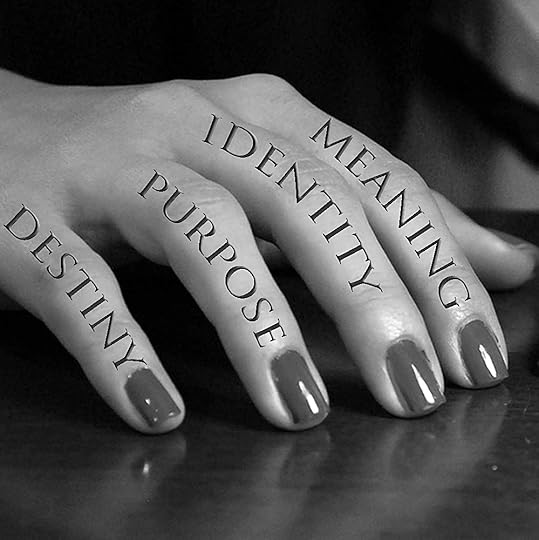

We have three other fingers and a thumb that are just as important to our existence as our identity. Taken together, they hold our  entire existence in our hand.

entire existence in our hand.

Before we take a look at the five fingers of existentialism, I have a confession to make.

It is true that in my 20s I was nihilistic and suicidal because I was defeated by my inability to connect with people on a deep level. It’s true that I was this way because of my inability to overcome fear.

As a result I drank to flood my dryness and I drugged to trick my will into living another day.

But the real reason I was so broken and overburdened is because I didn’t have meaning in life.

I didn’t know who I was, because I didn’t know where I came from.

Because I didn’t know where I came from, I didn’t know where I was going.

Because I didn’t know where I was going, I couldn’t figure out my purpose.

Because I couldn’t find my purpose, my life had no meaning.

[image error]Of course I had some ideas about who I was and where I came from and where I wanted to go and what I wanted my purpose to be.

I’m not saying I didn’t have ideas. I’m saying that all my best thinking brought me to the hell of my own error.

And so when I used the finger, I felt some short-term power but no enduring empowerment.

I make this confession to point out that like so many other solutions in life, I already had what was missing.

Here is how I see it now:

Origin is the opposable thumb of our existence. We need to know where we came from in order to live a happy life. We are not animals by chance. We are creatures of eternal love.

Origin is the opposable thumb of our existence. We need to know where we came from in order to live a happy life. We are not animals by chance. We are creatures of eternal love.

Identity is the middle finger of existence. Love is the only thing that lasts. We being creatures of love are therefore superior to any suffering life can bring, including the knowledge of certain death.

Purpose is the ring finger of existence.  Because we must love to live, we must serve to be happy.

Because we must love to live, we must serve to be happy.

Destiny is the little finger of existence. Philosophy says that we are mortal. Theology says that we are eternal. Destiny says that we are both.

Meaning is the index finger of existence. With it we recall our origin and uncover our identity and identify our purpose and point to our destiny.

Notice especially with the index finger and the thumb that these digits all have intricate relationships with each other that are irreducibly complex. Yes these digits can move independently. But what is more unsearchable – that they move in isolation or that they move in unison?

Notice especially with the index finger and the thumb that these digits all have intricate relationships with each other that are irreducibly complex. Yes these digits can move independently. But what is more unsearchable – that they move in isolation or that they move in unison?

When this hand of existence opens up to another, it is love. When this hand of existence is clenched, it is justice. When this hand of existence is cupped with another it is faith.

Like the wheel of fortune, the five fingers of existentialism is part of the orbit of essential ideas that we must have in range if we are going to be good Americans and pursue happiness.

This is because the pursuit of happiness is the search for meaning.

But we do not have to search for meaning.

We already have it in our hand.

April 9, 2012

The Essence of Attraction

CROSS RIVER, N.Y. – Literary fiction is the gnarliest kind of writing to pull off and the hardiest kind of writing to read and the farthest kind of writing from anything that's commercial or popular or superficial.

So the easiest sale for a literary novel is to readers who already love classics or to readers who already have advanced educations or to readers who already have at least one positive experience reading serious fiction.

But the New Q mission is not to preach to people who love to read. The New Q mission is to reach people who don't see the need.

The New Q principle is not to promote lasting fiction to people who are likely to buy it, but to attract people to literature who habitually deny it.

New Q is interested in people who haven't picked up novel since high school and people who have never finished a novel and people who are otherwise restlessly resigned to the idea that serious reading isn't for them.

This vision is not meant to cause confusion.

Yet people who are well meaning ask what New Quoin is up to.

And people who see no purpose where profit isn't pursued ask why New Q is in business.

The answer is better than 10 questions. And one story is better than the answer.

It was one of those Monday nights at a medium-sized liberal arts college in New York City in one of those undergraduate literature composition classes packed with non-traditional students who have kids and full-time jobs and English as a second language.

And from a corner desk where student in his early 20s had been sleeping because he worked two jobs, the student blurted out to the professor who was writing something on the board "What's your book about?"

This was one of those professors who encourages students to speak out to get them engaged in conversations and to push them to come with answers in their own words when all they really want to do is sit there and not be bothered.

And although the professor didn't remember telling this class he had written a novel, the professor figured he must have dropped something about it – otherwise how would this highly erratic student in the corner know?

"You don't want to know," the professor told him.

"Yes I do."

So the professor told him in three sentences.

"I want to read it," he said.

"No you don't."

"Yes I do," he said. "It would be the only book I ever read."

To this day, the professor cannot say what he was talking about that woke the student in the corner out of sleep.

What wakes anyone out of sleep?

Nobody knows whether the student would have taken the professor's novel and read it and been moved by it had the professor had a copy there to give him that night. Nobody knows because that was the student's last night. He stopped showing up to class. The professor had to fail him.

This at least is clear: whatever was awakened in the student that night was something more profound than anything the professor could have been saying.

The student was turned on by something that had always turned him off.

When that happened, the professor should have been ready with encouragement and nourishment for the student instead of thinking of the welfare of everyone else in the class and letting the golden moment go to rot.

The point of the story – and the answer to why New Q is in business as an indigent independent – is that an artist is happier over one non-reader who picks a novel and gets something out of it than the artist is over sales to 99 readers who need no conversion to literature.

This can only be the case where the artist is more interested in a masterpiece than in millions.

This can only make sense if serious reading can reveal the life of meaning.

The good news is that it can.

Literature is sustaining and transforming because it is enduring. It endures suffering. It endures death. And it brings new life into people's worlds.

This fact may not keep commercial publishers from rolling their eyes at literary fiction. It may not keep non-readers from rolling their eyes at it.

But the fact remains that a man who does not read seriously is man who is out of range. And a man who is out of range is a weightless creature in a universe of gravity.

On the other hand, a reading man has chance. He may not be able to square the big questions of life well enough to corner his curiosity, but he can confidently look up to the orbit of essential ideas lit like planets on a bright night and know that he is part of his own mystery.

He can accept who he is and understand where he came from and have a chance to find out where he is going in time to fulfill his purpose.

He may not get all of this meaning at once from picking up a literary novel, but he sure won't get any of this if he never picks one up.

March 1, 2012

The New Route to Happiness

Finding the happiness that eludes pursuit…

Few things in life collect as much mileage as happiness and still sparkle with such newness.

Few things are as cultivated by privileged people as happiness and also thrive in the wild for anyone to harvest.

And few things are as particular to the American spirit as happiness and yet are also so universal.

Happiness fits all faces and spaces. It is as attractive to babes as it is to the aged. It is as potent in small measures as it is in big heaps. It graces the unexpected moment and it rewards the long-suffering season.

And yet, for everything that can be said about the most important word in the world after love, happiness leaves a world to be desired.

We marvel at the modern model of happiness that popular culture portrays in Hollywood and Wall Street and Madison Avenue so much that we can't help allowing those pictures of ease and excess and excitement to inform our own dreams of happiness, even if we see the wreck and distress that the pursuit of pleasure brings.

Hollywood happiness

We teach ourselves that happiness is something to possess as a right because it says so in black and white in the Declaration of Independence, even if we know that securing great things for ourselves is never as great as doing little things for others.

And so deep down we feel sad.

The happiness that we really want is not something that can be produced with riches or something that can be pursued like a college degree or something that can be promulgated by the government of the people. The happiness that we want is more personal than possessions, more precious than prestige, and more important than democracy.

But every day in the lives of the people we are closest to and in the life of our own heart the chase goes on for Hollywood happiness because the happiness that we really want eludes our pursuit.

This didn't happen by accident.

Somewhere in the evolution of the American culture, after generations of having life easier than anyone else on earth, we decided to conform the big ideas of existence to suit our own comfortable sensibility. We did so because to conform ourselves to the big ideas of existence would require hard work, and everyone knows that hard work is only for people who have not made it yet.

After we decided that life begins at birth and after we decided that liberty begins at moral relativity we concluded that the classical definition of happiness as the highest good also needed to be more utilitarian.

And so the highest definition of happiness that our Founding Fathers intended became individual definitions of financial success, and our pursuit of happiness became the pursuit of possessions.

Our Madison Avenue friends helped us bridge the schism we created when we ditched our common definition of happiness by proclaiming that a few hundred million people each trying to get the most happiness they could for themselves was all the unity a great country like America needed.

As a result, we are killing ourselves trying to be happy. We are looking over our shoulders at what other people have and over looking people who need us in the name of our right to a better quality of life.

And so it is time to end the pursuit of happiness in America.

It's time to kick this trick phrase that has been manipulated too many ways and as a result does not mean what it should.

The novelist Jamaica Kincaid famously snapped in a 1997 Mother Jones interview that the pursuit of happiness was a "bad little sentence."

[image error]

Jamaica Kincaid

And she was right.

Just as the Horatio Alger myth had to expire and just as the American Dream had to retire so too this bad little sentence must burn in the fire before it kills our spirit to seek something higher.

We could spend all spring talking about the people we love and the harm they have done in the pursuit of happiness. We could change the names of our parents and our spouses and our children and our closest friends, and we could blur the circumstances of their sins so that they would not recognize themselves being destroyed for their bad example.

But that would be bad form.

It would be bad form because we ourselves have done worse things in the pursuit of happiness. It did not matter at the time to us that we were hurting ourselves and hurting other people. It did not matter at the time to us because we were not thinking of anyone but ourselves. We were not thinking of anyone but ourselves because that is what the pursuit of happiness means in our culture.

If we think about it, the things we call happiness are not happiness. Doing whatever we want whenever we want is not happiness. It is slavery. If we cannot stop ourselves from committing adultery when we want to commit adultery, then committing that adultery is not pursuing happiness; it is pursuing enslavement to adultery. If there is not something more important than ourselves in the struggle we have over our own actions that gives us the power to overcome unjust impulses, then there is nothing more important than ourselves in the struggle, and we are powerless over our own actions. And that is certainly not the definition of happiness. That is the definition of emptiness.

And when we cannot fill the emptiness inside with possessions we pursue in the name of happiness we start looking for power over our helplessness by breaking rules. We start hunting for happiness in strange places where happiness has never hidden.

We do not need to worry about being bad Americans for wanting to change a bad little sentence. If there is anything good about the pursuit of happiness it will come out of the fire refined.

It is our hearts that we have to keep in mind. If the pursuit of happiness is not the common quest for the highest good then it is not happiness we are pursuing but simple self interest.

We need a quest that makes our hearts stretch such as "Life, liberty and the pursuit of peace."

Or, if we must have happiness in our creed, how about Life, liberty and the pursuit of the highest good?

February 11, 2012

February 4, 2012

Elegance in Isolation

NEW YORK — There has been a lot of talk this year about elegance and isolation.

Watching the New York Knicks play with their smooth new superstar Melo, basketball commentators here and across the country have been as unified as a chorus in proclaiming that Melo's individual genius for scoring against any opposition kills the teamwork that is needed on the court to win games against good opponents.

In basketball language, what Melo does is called isolation. In everyday talk, it's called everyone walk away to a corner of the floor and watch Melo score.

You don't need to know any basketball language to know about the poetry of motion and execution. And you don't need to know a thing about poetry to know that writing that does not pass the ball to the reader is selfish.

What they say about Melo when he gets the ball is that the movement on the court stops. When Melo gets the ball and makes it clear that he is going to score, it freezes the other nine guys on the floor.

The ball sticks.

All season long I have been saying so what? So what if the ball sticks if Melo hits? Eventually, I have been saying to myself after each Knicks loss, poetry is going to conquer.

Well today I noticed as I was writing that the narrator's voice I was using in the story was pulling an isolation. In fact, my narrator has been pulling a lot of isolation.

Check it out – the narrator has a great voice. Beautiful, even. He's not a $100 million dollar superstar like Melo playing to wild crowds in Madison Square Garden, but he knows how to make words sing.

And today here was my narrator with the "ball" preparing to go to the "basket." And I noticed, just like the commentators have been saying all along about the Knicks, that the characters in my story were standing around watching.

The story was sticking.

Even when I saw the flow had stopped, it was tempting to say 'So what?' Let the other character's watch. Maybe they will learn something about grit and grace.

But I know enough about storytelling to know that stories have to move in order to be stories.

Next time my narrator wants to pull an isolation, I may have to force one of my characters into the lane and make my narrator pass.

January 16, 2012

The Real Wheel of Fortune

The Real Wheel of Fortune | a friend and guide for the alone and the blind

I always thought that the Wheel of Fortune was an American game show where contestants spin a cash-slotted wheel and guess at letters to solve the billboard-sized word puzzle.

I never knew that the real Wheel of Fortune is a rich and electric Renaissance concept about the role that people play in their own fate. I never knew that the real Wheel of Fortune is a guide and a friend for a journey that too often we undertake alone and blind. Remember that I didn't read in my youth and in my early adulthood. The shelves in my library of ideas were empty. I didn't have a single big thought in stock. I wasn't nourished by the classics and I wasn't strengthened by the masterpieces. The result was a weak and defeatist identity that kept me from making connections about origin and destiny and purpose and meaning.

I don't know what I would have done back then had someone showed me the real Wheel of Fortune anyway.

I don't know what I would have done back then had someone showed me the real Wheel of Fortune anyway. The more I see the wasteland of my early adulthood and the more I admire the oasis of answers in great books, the more I realize how truly bereft I was.

It's one thing to be dying of thirst in the desert. It is another thing to be dying of thirst and not to know that water is the solution.That was me.So it wasn't until my 40s, when I picked up a beautiful translation of Dante's Inferno, that the real Wheel of Fortune was explained to me in a couple of massive footnotes.

The discovery of this Real Wheel from the Renaissance was brighter to me than Times Square in December. I can't tell you how many times it has saved me from a dark night of the soul.

The Wheel of Fortune has become one of my favorite tools to manage disappointment, to reconcile injustice, to endure suffering and to accept brokenness.

I would love to hear how other people understand it and how other people apply it to their lives.Here is how the wheel works for me.

1. Each titled station on the wheel represents a personal stage in life. The stations are not necessarily literal descriptions of actual life events. I must be able to relate each station to a stage in my life.

For example, I have never literally had riches. But I know the bile of abundance and privilege and haughtiness. I had riches in my youth, coming from a white, middle-class American family in the Chicago suburbs. I had more than any other kid in the world. I acted like it.

2. The wheel is like a clock with fixed stations, and I move like a minute hand, clockwise, towards peace.

I do not believe it's possible to "get a little better each day," as it is popular to preach, but I do believe it's possible to be happier by becoming more accepting of suffering and by becoming less selfish through service and sacrifice.

3. Each station on the wheel is in a direct relationship with the stations next to it.

For example: starting at the top of the wheel where peace reigns and moving clockwise, the natural progression for someone with peace in life is to cultivate riches. Solomon comes to mind. From riches comes pride. And there, in the space of one season, look how far the proud man has already fallen from peace. And that is just the beginning. The only place for a proud man to go is impatience. From impatience springs war.

From the bottom of the wheel, there is no place to go but up. It might be hard to think of poverty as an improvement for anything, especially in America, but certainly a practice of making do with what one has is an upward adjustment and a clear an upgrade from war. A man who is able to accept poverty is also making progress towards humility. And a man who is humble has only patience to endure before he can finally be at peace.

4. Each station on the wheel requires the visitor to learn something or earn something in order to move on and suffer a new trial. We have to overcome our human nature if we want to keep kicking in the direction of peace.

[image error] One thing I've found is that the time allotments for each station in real life are not necessary slotted as evenly as they are represented on the Wheel.

Notice in the image from the Middle Ages how the people on the vain side of the wheel are falling off while those on the left hand side of the wheel are hanging on and climbing up with their eyes set higher than their station.

It doesn't take much time to fall a disgraceful distance. Climbing back up is what takes forever.

Before I reveal my own position on the wheel, I want to share what the Real Wheel of Fortune says about fate – that everyday ethereal thing that humbles the proud and raises the poor and seems content to let luck fuck everything up.

I don't know about others, but for me fate has always been one of those elusive realms hovering over free will and divine will, but never lingering near either one faithfully enough to belong to either realm. It wasn't until I found myself on the Wheel of Fortune that I discovered my place in my own mystery.

When I first discovered the Wheel, I was on the border of war and poverty.

At some point I made peace with poverty. I don't know that I love Lady Poverty the way some of my heroes do, but I came to terms with it well enough to set my sights on humility. I will say just one thing about humility, which is greatly misunderstood; faith makes humility manageable.

For example: my reward for a fight with three editors was to be busted down and moved out of the mothership to a bureau. This was well after I had gotten sober and started cultivating the life of meaning. I was warring with pride. Then I was reminded of the story of Naaman the great Syrian commander whose leprosy was so advanced that he went to a prophet's shack in the backwoods for a cure. The scrawny bald prophet didn't even come out of the shack to meet the great general but sent a servant who told Naaman to wash 7 times in the Jordon River. Naaman came from a land of big time rivers and was so insulted at the suggestion that he should wash in Jordan's mud that he started to walk.

Then I was reminded of the story of Naaman the great Syrian commander whose leprosy was so advanced that he went to a prophet's shack in the backwoods for a cure. The scrawny bald prophet didn't even come out of the shack to meet the great general but sent a servant who told Naaman to wash 7 times in the Jordon River. Naaman came from a land of big time rivers and was so insulted at the suggestion that he should wash in Jordan's mud that he started to walk.

But Naaman's little slave girl objected: "If the prophet had asked you to do something difficult to cure your leprosy, wouldn't you have done it?"

"Of course." Naaman told her.

"Then why not do the easy thing he tells you."

Naaman washed seven times and was healed, and I worked seven years on the Wheel with humility and that classic spiritual lesson as my aid.

Today, as of this writing, I am trying to be patient. At first I had the crazy idea that I might have to battle with patience for a few years or maybe for a few years more than that before the limousine rolled up to my house to take me to my payday. But if patience is really patience, wouldn't this station last forever? The worst thing about patience is when it doesn't stop. Somewhere along the way I'm afraid I will have to make peace with patience, although it is hardly the kind of friend I would chose.

It is my fate.

excerpts from The Wall at newquoin.com

Whether it’s for the criticism, the confessions or the connections about reading, writing and the life of meaning, The Wall is where we discover what we know about ou Revival | Revolution | Renaissance

Whether it’s for the criticism, the confessions or the connections about reading, writing and the life of meaning, The Wall is where we discover what we know about ourselves and what we know about our world by exploring the questions of origin and destiny and identity and purpose.

The Wall is a place for transformation as much as a place for information. It is also a place for your contribution. ...more

- Rob Ryser's profile

- 1 follower