David Weinberger's Blog, page 93

April 6, 2012

April 4, 2012

Culture of Hope

Forum d'Avignon is an annual get-together in France to talk about culture, by which most of the attendees (and especially President Sarkozy who came to give a speech) mean how they can squash the Internet and retain their stranglehold on culture. A little harsh? Maybe, but not entirely unfair. I went last year, and both Jamie Boyle and I felt so oppressed by the relentless Internet Fear exhibited by the other presenters that we felt obliged to say, "You know, there are some good things about the Internet also." We also both found a cadre of fellow travelers among the attendees and a handful of the other presenters, including many of the conference organizers. (Here's a set of my posts from the Forum.)

The Forum today invited a set of people to respond to four questions. The first question is: "1. Does culture / creative imagination give you a reason to hope?" With the above as context, here is my response:

Of course! If not culture, then what would give us reason to hope?

There are a few elements coming together that make this an especially hopeful time…and a few elements that I take as cold water being thrown in the face of hope.

The elements of hope include: (a) the scale of content, (b) the intense inter-linking of that content, (c) the growing open access to that linked content, and (d) the new forms of collaborative sociality that are emerging that (e) value difference and disagreement.

(a) The scale means that we now have works that can matter to us in any way we can imagine, rather than relying upon centralized authorities to decide what counts. Of course, from those centralized sources we have gotten great works of art, but we have gotten far more gross, coarsening, commercial crap. (b) The fact that these elements are linked means that we can now explore ideas all the way to the ends of our curiosity. It also means we can continuously derive new meaning from this interlacing of ideas. (c) Open access – the growth of outlets that may or may not be peer-reviewed and edited, accessible to the world for free – means that our best ideas are not locked up where only the privileged can view them. (d) The availability of these works on the very same medium that enables us to form social networks around them – the fact that the Net is equally good as a means of distributing content and as a social medium is unprecedented – has spurred innovative new ways of working and being together. Some of these new social forms have tremendous power, and are tremendously engaging; we can do things together that we never before thought possible. (E) Finally, the Internet only has value insofar as it contains and embraces differences and disagreements. A culture that does so is far more robust and far less oppressive than a culture homogenized by a timid sameness – the sort of lack of adventure characteristic of mainstream media.

Against this we have old industries that benefited from the scarcity of works and the difficulty of distributing them. They view culture as the set of cultural objects, and believe that they are entitled to continue to restrict and control access to them. They say they are doing this in order to support the artists, but they in fact are pocketing most of the artists' wages in the name of services we no longer need these industries to provide. Culture flourishes when it is open, abundant, connected, engaged, and diverse. Such a culture supports artists of every sort. The culture of hope is just such a culture.

April 2, 2012

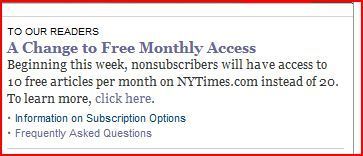

Why? Does the Times have research that shows that when s...

Why? Does the Times have research that shows that when someone is denied access to her eleventh NYT article, she's going to cave in and buy a subscription for $195/year? Because my informal market research — I sat myself in an airless room, asked myself some questions, and rewarded myself with m&m's — indicates that I will just get more annoyed at the NYTimes, and regret its insistence on losing its place in our culture.

PS: No, I don't know how to save the newspaper industry.

April 1, 2012

Books by Friends: Write Hard, Die Free

Howard Weaver's Write Hard, Die Free is a two-fisted memoir of how The Anchorage Daily News — a newspaper he helped found and then edited — went on to win two Pulitzer prizes and defeat the established major daily, which was, according to Howard, an oil industry mouthpiece. It's an entertaining story of scoops, legwork, drinking, and camaraderie.

It's also a reminder of an age that now seems as distant as the cowboys, although it was only a couple of decades ago. In part that's because Alaska remains a frontier state, but it's also because, while the future of newspapers is unknown, the days of brawlin' reporters are over.

Write Hard, Die Free (I love the title) is, as they say, a good read, and a reminder of a time not as distant as it already seems.

Reddit's awesome crowd-sourced April Fools

Reddit's Timeline lets you see reddits from the past and future. This is crowd-sourced humor, and whole bunches of it are pretty damn funny. Of course, some, not so much.

Many of the posts are in jokes about Reddit — e.g., in the '30s, someone posted "Ron Paul born – Great Depression to be ended soon?" Or in the Victorian Era: "We did it Ladies and Gentlemen! After 8 years of making our voice heard in every decent publication the empire has to offer, we did it: Arthur Conan Doyle is bringing back our hero!" But most are not directly about Reddit.

To explore it, go to Reddit and look for the column towards the right called "reddit timeline." Click on any of the periods, or on the up and down arrows to scroll more epochs. The 1920s is a pretty good one. Also, the Year Zero, and 1558.

Actually, browsing anywhere will lead you to something funny. IN MY OPINION.

March 31, 2012

[2b2k] The commoditizing and networking of facts

Ars Technica has a post about Wikidata, a proposed new project from the folks that brought you Wikipedia. From the project's introductory page:

Many Wikipedia articles contain facts and connections to other articles that are not easily understood by a computer, like the population of a country or the place of birth of an actor. In Wikidata you will be able to enter that information in a way that makes it processable by the computer. This means that the machine can provide it in different languages, use it to create overviews of such data, like lists or charts, or answer questions that can hardly be answered automatically today.

Because I had some questions not addressed in the Wikidata pages that I saw, I went onto the Wikidata IRC chat (http://webchat.freenode.net/?channels...) where Denny_WMDE answered some questions for me.

[11:29] hi. I'm very interested in wikidata and am trying to write a brief blog post, and have a n00b question.

[11:29] go ahead!

[11:30] When there's disagreement about a fact, will there be a discussion page where the differences can be worked through in public?

[11:30] two-fold answer

[11:30] 1. there will be a discussion page, yes

[11:31] 2. every fact can always have references accompanying it. so it is not about "does berlin really have 3.5 mio people" but about "does source X say that berlin has 3.5 mio people"

[11:31] wikidata is not about truth

[11:31] but about referenceable facts

When I asked which fact would make it into an article's info box when the facts are contested, Denny_WMDE replied that they're working on this, and will post a proposal for discussion.

So, on the one hand, Wikidata is further commoditizing facts: making them easier and thus less expensive to find and "consume." Historically, this is a good thing. Literacy did this. Tables of logarithms did it. Almanacs did it. Wikipedia has commoditized a level of knowledge one up from facts. Now Wikidata is doing it for facts in a way that not only will make them easy to look up, but will enable them to serve as data in computational quests, such as finding every city with a population of at least 100,000 that has an average temperature below 60F.

On the other hand, because Wikidata is doing this commoditizing in a networked space, its facts are themselves links — "referenceable facts" are both facts that can be referenced, and simultaneously facts that come with links to their own references. This is what Too Big to Know calls "networked facts." Those references serve at least three purposes: 1. They let us judge the reliability of the fact. 2. They give us a pointer out into the endless web of facts and references. 3. They remind us that facts are not where the human responsibility for truth ends.

March 28, 2012

The Gettysburg Principles for keeping your customers

I've got a post at the Harvard Business Review site about what I'm calling (not too seriously) The Gettysburg Principles. The point is that you can keep your customers buying from you if your business is of your customers, by your customers, and for your customers. "Of" means that your business is made up of people like your customers. "By" means that your customers are contributing to the creation of your product. "For" your customers means you put them first. These three terms give a handy way of analyzing why customers stick with some businesses even if they have to pay a bit more or make some other adjustments.

Anyway, there's more over at HBR…

[misc] Thesaurus of metaphors

Or maybe it's a dictionary. Or an encyclopedia. In any case, The Mind is a Metaphor you can look up metaphors by keyword and facet the results by date, genre, nationality, gender, etc. (Note that these are facets of the speaker, not of the metaphor.)

March 26, 2012

Kew Gardens adopts Web principles for real-world wayfinding

In a paper Natasha Waterson and Mike Saunders describe how Kew Botanical Gardens in England are adopting mobile technology to help visitors become "delightfully lost." From the abstract:

In October 2010, Kew Gardens commissioned an in-depth study of visitors' motivations and information needs around its 300-acre site, with the express aim that it should guide the development of new mobile apps. The work involved over 1,500 visitor-tracking observations, 350 mini-interviews, 200 detailed exit interviews, and 85 fulfilment maps; and gave Kew an incredibly useful insight into its visitors' wants, needs, and resulting behaviours.

It turns out that most Kew visitors have social, emotional, and spiritual, rather than intellectual, motivations during their time here. They do not come hoping to find out more, and they don't want or need to know precisely where they are all the time. In fact, they love the sense of unguided exploration and the serendipitous discoveries they make at Kew—they want to become "delightfully lost."

But as I read the actual paper, I was repeatedly struck by how often one could swap "in the Gardens" for "on the Web." The motivations, the cognitive space, the tools and techniques often mirrored the Web's. Indeed, one could argue that our experience of the Web is affecting how we view wayfinding in the real world, and not just because the Kew project integrates the offline and online worlds via mobiles, QRcodes, etc. Rather, the sense of serendipity, the loose connections, the desire to be able to follow one's interests, the expectation that one will always be able to get more information about something, and the desire to contribute back — this is a public space we're building together — all feel webby. Indeed, the paper's overall point is that architects of information spaces ought not pick a single motive for those spaces' users, and that is one of the fundamental lessons of the newly miscellanized world.

(Hat-tip to Hanan Cohen for the link.)

March 25, 2012

What you see animates into what you get

I spent too much time yesterday debugging a table in the Wikipedia markup language (on a different Wikimedia wiki). This would have come in handy: