Terri Windling's Blog, page 75

May 8, 2018

Thoughts on a train

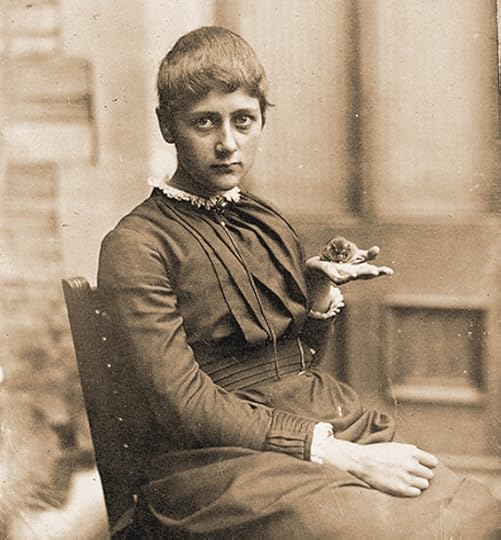

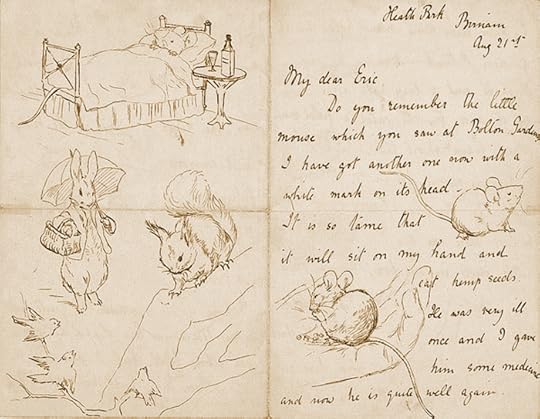

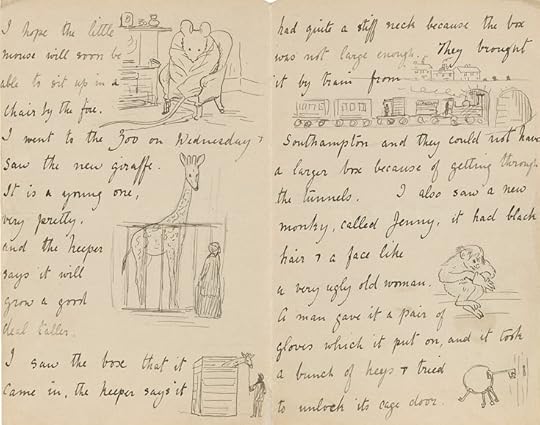

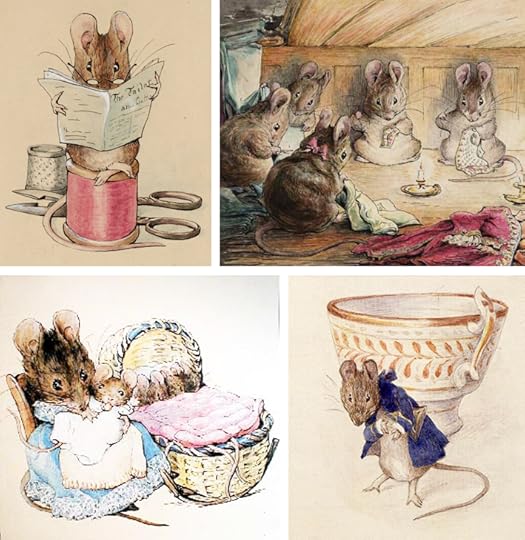

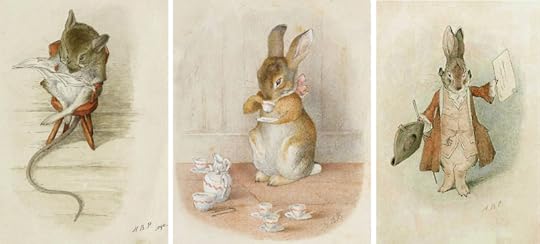

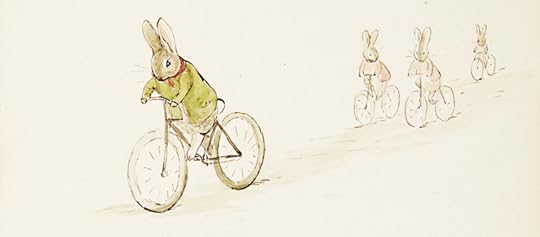

I'm on a long train journey today, traveling from Exeter to Glasgow. Right now we're rolling through the Lake District, which makes me think of one of my great heroes, Beatrix Potter: author, illustrator, farmer, naturalist, rural historian, and conservationist, who worked so hard to preserve this beautiful countryside that she loved.

"I remember I used to half believe and wholly play with fairies when I was a child. What heaven can be more real than to retain the spirit-world of childhood, tempered and balanced by knowledge and common-sense." - Beatrix Potter

"There's something delicious about writing those first few words of a story. You can never quite tell where they will take you. Mine took me here, where I belong." - Beatrix Potter

"I do so hate finishing books. I would like to go on with them for years." - Beatrix Potter

"Thank God I have the seeing eye, that is to say, as I lie in bed I can walk step by step on the fells and rough land seeing every stone and flower and patch of bog and cotton pass where my old legs will never take me again." - Beatrix Potter

"Believe there is a great power silently working all things for good, behave yourself and never mind the rest." - Beatrix Potter

Some of the pictures in this post first appeared on Myth & Moor on Beatrix Potter's 150th Birthday, July 28, 2016. Descriptions of the images can be found in the picture captions. For more information about this remarkable woman's life, I recommend Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature by Linda Lear. The Tale of Beatrix Potter by Margaret Lane is also good, and At Home With Beatrix Potter by Susan Denyer is delightful.

May 7, 2018

Reimagining Fantasy

I'm heading up to Scotland this week to give a talk on fantasy literature with two of my oldest friends: Ellen Kushner and Delia Sherman. The event is sponsored by Fantasy at Glasgow, the excellent Masters programme for Fantasy Lit at the University of Glasgow. Tickets are free and all are welcome, so if you're anywhere nearby, do come join us. And if we haven't met in person before, please don't be shy about introducing yourself afterwards.

Please note that the venue & time has been changed since earlier listings of the event (in order to make room for more people to attend). The information above is correct.

Tunes for a Monday Morning

It's a three-day holiday weekend here in the UK; the sun is shining, the hills are turning green, and wildflowers are blooming in the woods. I'm starting the morning with a strong cup of coffee, essays by Anne Fadiman, and a mix of bluegrass, Appalachian, & new folk music from North America...

Above: "Banjo Pickin��� Girl/Hunting Around The Hill," performed by bluegrass musicians Molly Tuttle & Rachel Baiman, who are currently touring the British Isles. Tuttle is from San Francsico, and Baiman is based in Nashville, Tennessee.

Below: "Good Enough," written and performed by Molly Tuttle, from her solo album, Rise (2017). I love this song, which is timely for me right now...and perhaps also for you.

Above: "Too Long (I've Been Gone)," written and performed by bluegrass musician and historian Dom Flemons, co-founder of Carolina Chocolate Drops. The song is from his first solo album, Prospect Hill (2014).

Below: "Going Down the Road Feelin' Bad," from Flemon's terrific new album Black Cowboys, which "sheds a light on the music, culture, and complex history of the golden era of the Wild West."

Above: "Woman of Constant Sorrow," a traditional Appalachian song performed in an untraditional manner by Rhiannon Giddens, another orginal member of Carolina Chocolate Drops. The track and video is a collaboration with electronica musician Sxip Shirey, and appears on his new album, A Bottle of Whiskey and a Handful of Bees (2018).

Below: "Far and Wide," a very beautiful song written and performed by Ruth Moody, from Winnipeg, Canada -- best known as a member of the Wailin' Jennys trio. She's recorded several albums with the trio, as well as three lovely solo albums.

Illustration by Helen Stratton (1867-1961)

May 1, 2018

May Day morning on Dartmoor

After waking before dawn for an outdoor Easter Sunrise Service a few weeks ago, this morning I rose in darkness again for a celebration rooted in the pagan faith: a gathering of Border Morris dancers on a quiet road by Hay Tor, on Dartmoor, to call up the sun at the dawn of Beltane with the pounding of feet, the cracking of sticks, and the music of fiddle, squeezebox and drum.

My favorite troupe (or "side," as they're traditionally called) is Beltane Border Morris: a wild and wonderful group of dancers who describe their art as the dark side of folk. This isn't the "bells and hankies and tea with the Vicar" sort of Morris dancing, it's fierce, eerie, athletic, unbridled -- invoking magic from the bones of the land and the old country lore that has not been forgotten.

Border Morris originated in the west of Britain -- probably sometime in the late Middle Ages, arising from dance traditions that were older still -- developed primarily by dancers and musicians along the border between England and Wales. The distinguishing characteristics of Border Morris (as opposed to other forms) are shorter sticks, higher steps, ragged costumes, blackened faces, and larger bands of musicians. The history of the blackened face is much disputed: it may have had ceremonial significance in the dance's deeply pagan origins; or it might have been a form of disguise adopted in years when Border Morris was frowned upon as rowdy, subversive, and un-Christian.

It certain is rowdier than most other forms of Morris; it's also more overtly pagan, and thus (to me) more powerful. Often performed at sacred times in the Celtic lunar calendar, the dances are tied to the seasons and the mythic wheel of life, death, and rebirth. Like other forms of sacred dance the world over, the drum beat and the dancers' steps weave patterns intended to keep the seasons turning and maintain the balance of the human/nonhuman worlds. Yet in contrast to other, more mannered forms of Morris, Border dancers unleash an energy that is earthier, lustier, more anarchic...both joyous and unsettling to watch, especially by dawn, dusk, or firelight.

This morning, there were two other local sides dancing with Beltane: Grimspound Border Morris, and a small group bedecked in ribbons whose name I didn't catch. The air was cold, nipping fingers and toes, as they danced the sun up over the moor and beat out a rhythm for summer's return.

When the sun was high, we said our goodbyes and made our way home across the moor, then down to Chagford through hedgerow lanes turned yellow with flowering gorse. It was early still. The village was quiet, and my own household still fast asleep. But while they slept, at the foot of Hay Tor, the remnant of an ancient folk ritual ensured that another summer would come. The land had been blessed. We'd all been blessed: dancers, watchers, and sleepers alike.

To learn more about Beltane Border Morris, please visit their lovely new website. You can watch a short video from this morning here -- and from previous May Days here and here. For more information about the folklore behind May Day and Beltane, go here.

I wish you an abundance of May blossoms and wildflowers, fecundity in all your creative work, fluid communion with our animal neighbours and the non-human world, the lusty good luck of the Jack-in-Green, and all of the season's good blessings for growth and renewal -- especially for those of you who live on the world's other side, entering the Long Dark of the year.

I wish you fine stories, poems, pictures, and tunes to ease the transition from winter to summer...and summer to winter...and back again.

I wish you dreams of drums, and of feather-clad dancers who move like a murder of crows taking flight.

I wish you a blessed, wild, and merry Beltane. Up the May!

April 25, 2018

Myth & Moor update

Dear readers, my apologies. I've been putting Part 2 of the "Books on Books" posts together, and it's taking longer than expected -- largely because my attention has been diverted by Other Necessary Tasks. So I'm afraid the post (focused on Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading by Lucy Mangan) will have to be delayed until tomorrow. In the meantime, I'd like to pass on a fabulous piece about writing that I came across recently, which made me laugh...and wince with painful recognition...and cheer because it's so damn true:

"How Do We Write Now?" by Patricia Lockwood.

I couldn't agree with Lockwood more. (Except for the penis thing.)

See you all tomorrow.

April 24, 2018

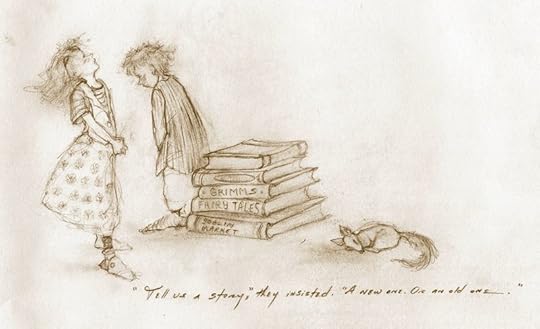

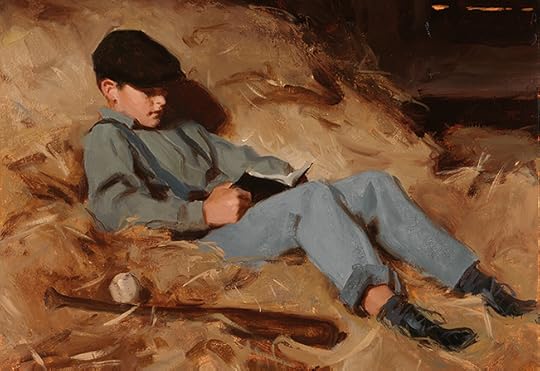

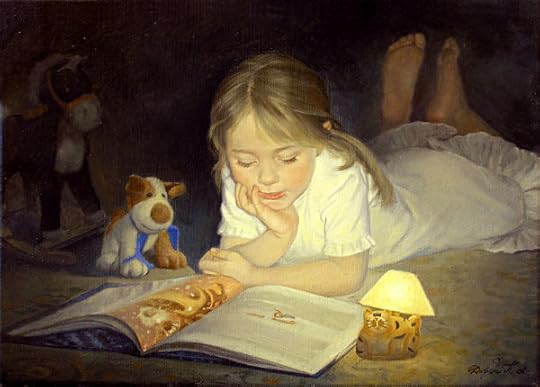

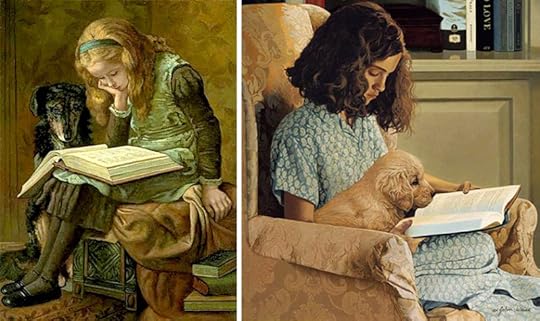

Books on books

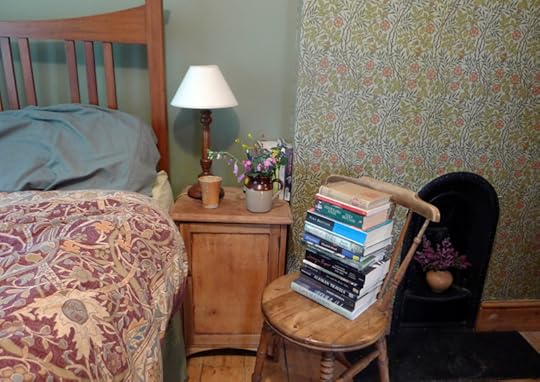

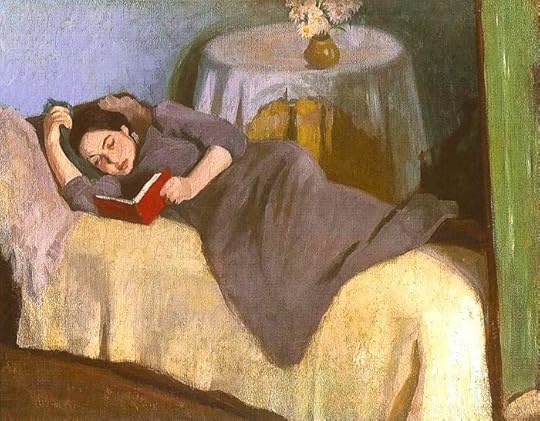

Having spent the better part of the last couple of months in and out of bed again has been a bit of a blow for my writing schedule (the manuscript I thought would be done by now is still inching its way to the finish line), and my studio hours are still limited as I find my way back to health and strength. But when illness robs us of productivity, breaking down our usual routines, slowing time down to a crawl, it also gives us unexpected gifts -- and for me, that gift is the time read. Okay, I'd rather be writing, painting, doing, not watching the world through a fever haze, or experiencing life through a printed page -- but on those days when my body fails I'm grateful to books, and to all those who write them.

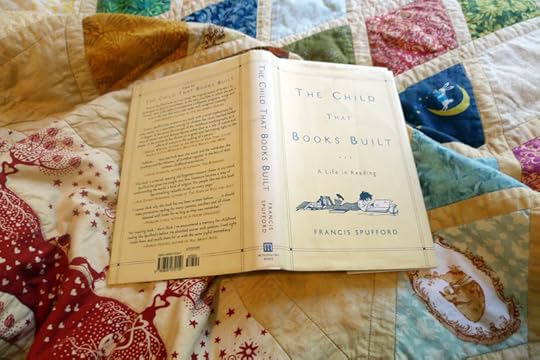

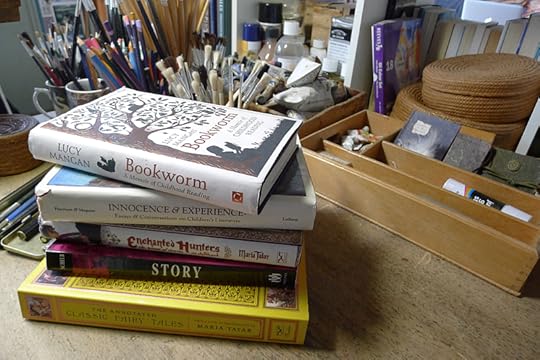

Reading having played a big part in my life for many reasons in addition to health, I have a particular fondness for books about books. Here are three I've read (or re-read) recently: The Child That Books Built by Francis Spufford, Bookworm by Lucy Mangan, and Books & Island in Ojibwe Country by Louise Erdrich. All three are memoirs, rather than literary studies; all three explore the author' s personal relationship with books; all three examine the ways that stories form us, effect us, and define us.

Let's start with The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading by Francis Spufford.

I first read Spufford's book in 2002, the year of its publication, and what struck me then was the unusual nature of its composition: childhood memoir mixed with literary history, cognitive science and child psychology in relation to story. In the intervening years, writers of memoir have expanded the form in so many ways that the premise of the book has lost its radical edge; I find that I have to remind myself that Spufford's memoir was a pioneering text, with both the strengths and flaws of form that trail-blazing entails. That said, it is still a very good read. Spufford is roughly the same generation I am (unlike Lucy Mangan) and grew up with many of the same children's books on his shelves. He also has a taste for fantasy (Mangan largely does not), and discusses the genre with knowledge and love. Although his writing on fairy tales relies too much on the disputed psychoanalytic theories of Bruno Bettleheim, his passion for all things magical wins me over nonethless, along with his poignant exploration of a childhood in which finding doors into other worlds was merciful and necessary.

Here's a passage from Spufford's introduction to give you a sense of the book as a whole:

"I began my reading in a kind of hopeful springtime for children's writing. I was born in 1964, so I grew up in a golden age comparable to the present heyday of J.K. Rowling and Philip Pullman, or to the great Edwardian decade when E. Nesbit, Kipling, and Kenneth Graham were all publishing at once. An equally amazing generation of talent was at work as the 1960s ended and the 1970s began. William Mayne was making dialogue sing; Peter Dickinson was writing the Changes trilogy; Alan Garner was reintroducting myth into the bloodstream of daily life; Jill Paton Walsh was showing that children's perceptions could be just as angular and uncompromising as adults; Joan Aiken had begun her Dido Twite series of comic fantasies; Penelope Farmer was being unearthly with Charlotte Sometimes; Diana Wynne Jones's gift for wild invention was hitting its stride; Rosemary Sutcliffe was just adding the final uprights to her colonnade of Romano-British historical novels; Leon Garfield was reinventing the 18th century as a scene for inky Gothic intrigue. The list went on, and on, and on. There was activity everywhere, a new potential classic every few months.

"Unifying this lucky concurrence of good books, and making them seem for a while like contributions to a single intelligible project, was a kind of temporary cultural consensus: a consensus both about what children were and about where we all were in history. Dr. Spock's great manual for liberal, middle-class child-rearing had come out at the beginning of the Sixties, and had helped deconstruct the last lingering remnants of the idea that a child was clay to be molded by a benevolent adult authority. The new orthodoxy took it for granted that a child was a resourceful individual, neither ickily good nor reeking of original sin. And the wider world was seen as a place in which a permanent step forward toward enlightenment had taken place as well. The books my generation were offered took it for granted that poverty, disease and prejudice essential belonged in the past. Postward society had ended them.

"As the 1970s went on, these assumptions would lose their credibility. Gender roles were about to be shaken up; the voices that a white, liberal consensus consigned to the margins of consciousness were about to be asserted as hostile witnesses to its nature. People were about to lose their certainty that liberal solutions worked. Evil would revert to being an unsolved problem. But it hadn't happened yet; and till it did, the collective gaze of children's stories swept confidently across past and future, and across all international varieties of the progressive, orange-juice-drinking present, from Australia to Sweden, from Holland to the broad, clean suburbs of America.

"For me, walking up the road aged seven or eight to spend my money on a paperback, the outward sign of this unity was Puffin Books. In Britain, almost everything written for children passed into the one paperback imprint. On the shelves of the children's section in the bookshop, practically all the stock would be identically neat soft-covered octavos, in different colors, with different cover art, but always with the same sans serif type on the spine, and the same little logo of an upstanding puffin. Everything cost about the same. For 17p -- then 25p and then 40p as the 1970s inflation took hold -- you could have any one of the new books, or any of the children's classics, from the old ones like The Wind in the Willows or Alice to the new ones that were only a couple of decades into their classichood, like the Narnia books (C.S. Lewis had died the year before I was born, most unfairly making sure I would never meet him).

"If you were a reading child in the UK in the Sixties or Seventies, you too probably remember how securely Puffins seemed, with the long, trust-worthy descriptions of the story inside the front cover, always written by the same arbiter, the Puffin editor Kaye Webb, and their astonishingly precise recommendation to 'girls of eleven and above, and sensitive boys.' It was as if Puffin were part of the administration of the world. They were the department of the welfare state responsible for the distribution of narrative. And their reach seemed universal: not just the really good books you were going to remember forever, but the nearly good ones too and the completely forgettable ones that at the time formed the wings of reading and spread them wide enough to enfold you in books on all sides."

A little later in the Introduction, Spufford lays out the premise of his memoir:

"I have gone back and read again the sequence of books that carried me from babyhood to the age of nineteen, from the first fragmentary stories I remember to the science fiction I was reading at the brink of adulthood. As I reread them, I tried to become again the reader I had been when I encountered each for the first time, wanting to know how my particular history, in my particular family, at that particular time, had ended up making me into the reader I am today. I made forays into child psychology, philosophy, and psychoanalysis, where I thought those things might tease out the implications of memory. With their help, the following chapters recount a path through the riches that were available to English children of the 1960s and 1970s, and onward into the reading of adolescence. It is the story (I hope) of the reading my whole generation of bookworms did; and it is the story of my own relationship with books; both. A pattern emerged, or a I drew it: a set of four stages in the development of that space inside where writing is welcomed and reading happens. What follows is more about books that it is about me, but nonetheless it is my inward autobiography, for the words we take into ourselves help to shape us. "

It is a premise Spufford amply fulfills.

Bookworm by Lucy Managan, newly published this year, is constructed on similar lines, and yet is a very different kind of book. More on that in the next post.

Words: The passage above is from The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading by Francis Spufford (Henry Holt & Co, 2002); all rights reserved by the author. Pictures: The art is identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) Related Reading: Previous posts that discuss The Child That Books Built include "In the Forest of Stories" (2013) and "Built by Books" (2014).

April 23, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning: songs for the spirit

I've been deeply in love with Nahko Bear's music since his first album came out in 2013, but living in a tiny village on Dartmoor, I've never been anywhere near one of his concerts. You can imagine my astonishment then when I learned he was coming to Devon this spring on a small accoustic tour, billed as "an evening of poetry,  story, and brotherhood medicine in song" with his friend Trevor Hall. Howard and I went to the gig last week, held in an arts centre in Exeter. The room was packed, the night was magical, and I'm so glad we were there. How these two open-hearted, unpretentious young men with nothing but two guitars and a piano between them managed to fill the room with such powerful medicine for body and soul is unfathomable...but they did.

story, and brotherhood medicine in song" with his friend Trevor Hall. Howard and I went to the gig last week, held in an arts centre in Exeter. The room was packed, the night was magical, and I'm so glad we were there. How these two open-hearted, unpretentious young men with nothing but two guitars and a piano between them managed to fill the room with such powerful medicine for body and soul is unfathomable...but they did.

This week's "Monday Tunes" come from both musicians: Nahko Bear, a singer/songwriter of Apache, Mohawk, Puerto Rican & Filipino heritage, who was raised in Oregon and now lives in Hawaii. And Trevor Hall, a folk/roots/reggae musician who grew up on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, and now lives in Boulder, Colorado.

Above: "What I Know" by Trevor Hall, from his forthcoming album The Fruitfall Darkess.

Below: "Dear Brother" by Nahko Bear, performed in New York City last month with two members of his band, Medicine for the People: Max Ribner (on horn) and Tim Snider (on fiddle).

Above: "San Quentin" by Nahko Bear, performed with Ribner and Snider in Philadelphia last summer.

Below: "Tus Pie (Your Feet)," from the same performance. This is my absolute favorite of Nahko's song, and I couldn't help tearing up a bit when he played it in Exeter last week -- on solo piano (rather than guitar), sliding into it from a rather stunning version of "Bridge Over Troubled Waters."

Above: "The Wolves Have Returned" by Nahko Bear, another favorite of mine. The Exeter concert ending with Trevor joining Nahko on stage for a glorious rendition of this song, complete with wolf howls. Alas, there's no video of the performance, but Nahko's solo version is lovely as well.

"I'm running the song lines, I'm wrapping my prayer ties, preserving the old way; the wolves have returned." They have indeed.

To end as we began, with Trevor Hall: here's "To Zion," from his album Kala (2015).

The wolf painting, "Nighteyes," is by Jackie Morris.

April 21, 2018

A pony interlude

Every spring, the local herd of Dartmoor ponies comes down from the moor to have their foals in the shelter of our village Commons. Today I counted four foals so far, with more on the way. Spring is truly here.

"There's magic in the trees and the hills and the river and the rocks, in the sea and the stars and the wind, a deep, wild magic that's as old as the world itself. It's in you too, my darling girl, and in me, and in every living creature, be it ever so small." - Kate Forsyth

April 18, 2018

Why we need fantasy

The following passage by Lloyd Alexander (1924-2007) comes from an essay published in The Horn Book fifty years ago, yet I'm struck by how relevant it still seems to be today:

"Anyone close to children -- librarians, teachers, maybe even parents -- knows they do not hesitate to come out with straightforward questions. I am beginning to learn this for myself, although the process has been a little backwards: Instead of getting to know children first, then writing books for them, the opposite is happening. It is only recently I have had some happy occasions to meet real live children. And not only in schools and libraries. At home I often discover a few hanging around the kitchen or perched on the sofa, swinging their heels. We talk awhile, they tell me what a hard day they had, I tell them what a hard day I have had -- there's really not much difference. But they constantly surprise me. The other afternoon one little girl asked, 'What would you rather do: be a millionaire or write books for children?'

"I gave her an absolutely honest answer. I said I would rather write books for children.

"Of course, I added, if someone felt inclined to give me a million dollars tax-free, in all politeness I could not refuse.

"But my answer was truthful. And I believe any serious, creative person -- and this includes teachers and librarians, for I have learned how really creative they are -- would have said the same. Because -- despite our status-oriented society, our preoccupation with 'making it,' with staying young forever, buying safe deodorants and unsafe automobiles -- I think something new is happening.

"Whatever our individual opinions, I think each of us senses that as a people we are in the midst of a moral crisis -- certainly the deepest of our generation, perhaps of our history. Few of us are untouched by a kind of national anguish. And it hurts. But if we felt nothing, if nothing moved or troubled us, then I feel we would be truly lost. For isn't anguish part of growing up? Without knowing grief, how can we ever hope to know joy?

"In the past, we have always been able to find technical or technological solutions to our problems. They have been external problems, for the most part, yielding to external solutions. And so we are not quite used to problems demanding inner solutions. In an article on fantasy literature, Dorothy Broderick points out that the English have dealt with fantasy more comfortably than we have in America and comments that perhaps, since England is so much older a nation, the English have had time to ask Why? instead of only How?

"It is true that we haven't had long years of leisurely speculation. But, ready or not, the time for us is now. A dozen Whys have been put to us harshly and abruptly. And searching for the Why of things is leading us to see the purely technological answers are not enough.

"We have machines to think for us; we have no machines to suffer or rejoice for us. Technology has not made us magician, only sorcerer's apprentices. We can push a button and light a dozen cities. We can also push a button and make a dozen cities vanish. There is, unfortunately, no button we can push to relieve us of moral choices or give us the wisdom to understand the morality as well as the choices. We have seen dazzling changes and improvements in the world outside us. I am not sure they alone can help change and improve the world inside us.

"We are beginning to understand that intangibles have more specific gravity than we suspected, that ideas can generate as much forward thrust as Atlas missiles. We may win a victory in exploring the infinities of outer space, but it will be a Pyrrhic victory unless we can also explore the infinities of our inner spirit. We have super-sensitive thermographs to show us the slightest variations in skin temperature. No devices can teach us the irrelevance of skin color. We can transplant a heart from one person to another in a brilliant feat of surgical virtuosity. Now we are ready to try it the hard way: transplanting understanding, compassion and love from one person to another.

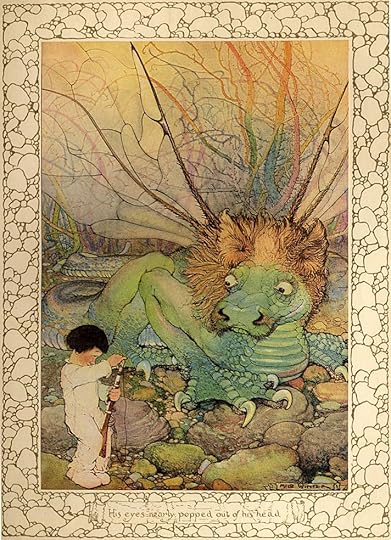

"To me, one of the clearest reflections of this changing attitude is a growing appreciation of fantasy in children's literature. The climate for fantasy today is vastly different from what it was twenty, even ten years ago, when the tendency was to judge fantasy as a kind of lollipop after the wholesome spinach of reality -- a tasty dessert, but not very good for the teeth.

"Now I think we see fantasy as an essential part of a balanced diet, not only for children but for adults too. The risks of keeping fantasy off the literary menu are every bit as serious as missing the minium daily requirements of thiamine, niacin, and riboflavin. The consequences are spiritual malnutrition."

Five decades on, these words are still true. We still need fantasy. We still need folk tales, fairy tales, mythic fiction, magic realism and other forms of fantastical literature to help us "explore the infinities of our inner spirit," and re-imagine the world.

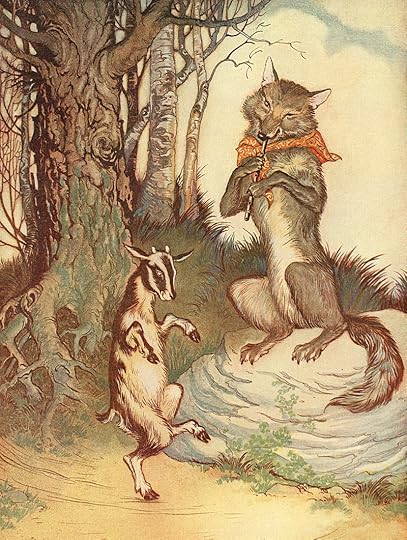

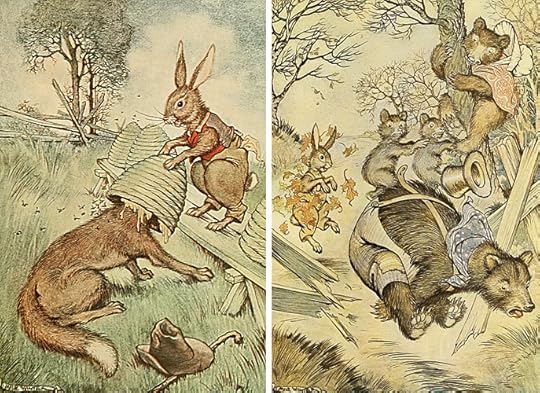

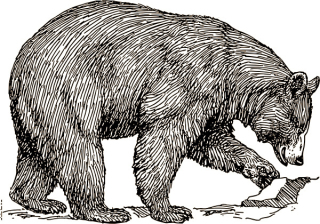

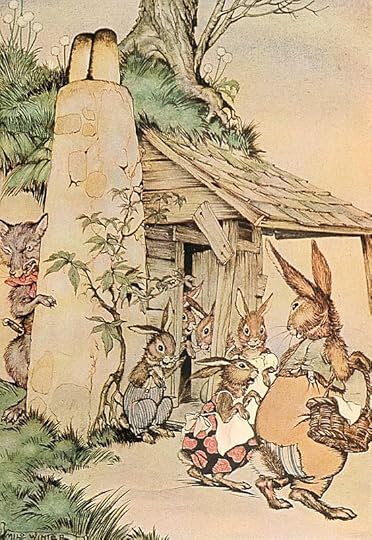

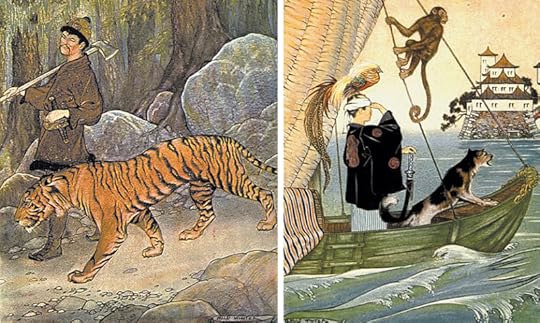

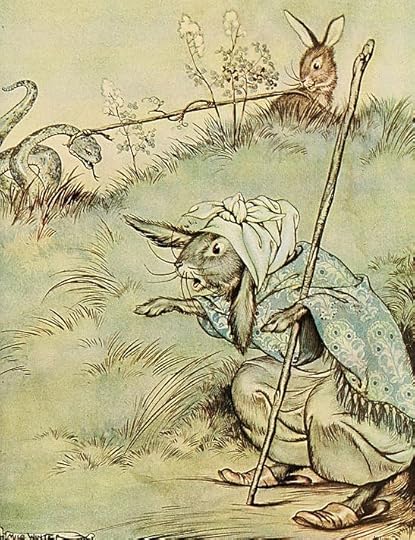

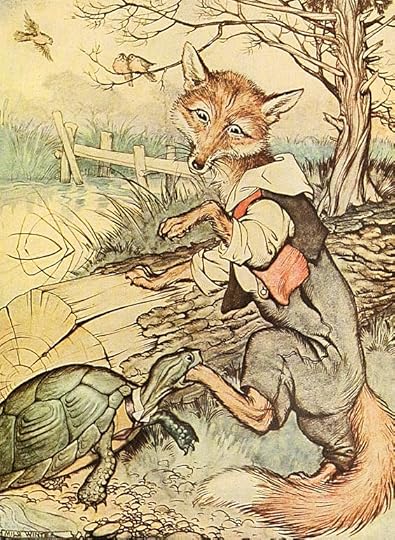

The art today is by American illustrator Milo Winter (1888-1956).

Born in Princeton, New Jersey, he trained at The School of the Arts Institute in Chicago, and illustrated his first children's book (Billy Popgun) at the age of 24. He lived in Chicago until the 1950s, and in New York City thereafter, illustrating a wide range of books for both children and adults -- including Gulliver���s Travels, Tanglewood Tales, Arabian Nights, Alice in Wonderland, Twenty Thousand Leagures Under the Sea, The Three Muskateers, Treasure Island, A Christmas Carol Aesops for Children, and Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales.

To see more of his work, go here.

The passage above is from "Wishful Thinking - Or Hopeful Dreaming?" by Lloyd Alexander (The Horn Book, August 1968). All rights reserved by the author's estate.

April 17, 2018

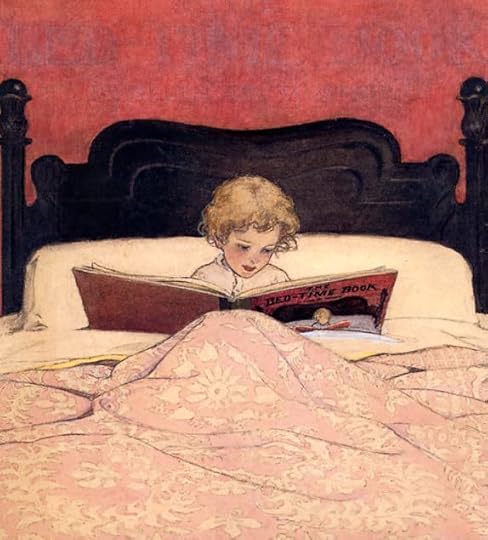

A walk in the woods

From The Faraway Nearby by Rebecca Solnit:

"Like many others who turned into writers, I disappeared into books when I was very young, disappeared into them like someone running into the woods. What surprised and still surprises me is that there was another side to the forest of stories and the solitude, that I came out that other side and met people there. Writers are solitaries by vocation and necessity. I sometimes think the test is not so much talent, which is not as rare as people think, but purpose or vocation, which manifests in part as the ability to endure a lot of solitude and keep working. Before writers are writers they are readers, living in books, through books, in the lives of others that are also the heads of others, in that act that is so intimate and yet so alone.

"These vanishing acts are a staple of children���s books, which often tell of adventures that are magical because they travel between levels and kinds of reality, and the crossing over is often an initiation into power and into responsibility. They are in a sense allegories first for the act of reading, of entering an imaginary world, and then of the way that the world we actually inhabit is made up of stories, images, collective beliefs, all the immaterial appurtenances we call ideology and culture, the pictures we wander in and out of all the time. In the children���s there are inanimate objects that come to life, speaking statues, rings and words of power, talismans and amulets, but most of all there are doors, particularly in the series that I, like so many children, took up imaginative residence in, for some years, The Chronicles of Narnia.

"I read one in fourth grade after a teacher who barely knew me handed it to me in the Marion school library; I can still picture his moustache and the wall of books. I read it and read it again and then began to save up to buy the seven books, one at a time. The paperbacks came from Amber Griffin, the enchanted bookstore in the middle of town, whose kind proprietor rewarded me with the case in which the seven books fit when I had paid for the last one. I still have the boxed set, a little tattered though I think no one has ever read them other than me. When I took one out recently, I noticed how dirty the white back of the book was from my small filthy fingers then.

"Much has been written about the Christian themes, British boarding school mores, and other contentious aspects of the series, but little has been said about its doors. There is of course the wardrobe in the first book C.S. Lewis wrote, the wardrobe made of wood cut from an apple tree grown from seeds from another world that, when the four children walk into it, opens onto that world. Two of the other books feature a doorway that stands alone so that when you walk around it it is just a frame, three pieces of wood in a landscape, but when you step through it leads to another world. There���s a painting of a boat that comes to life as the children tumble over the picture frame into the sea and another world. There are books and maps that come to life as you look at them.

"And there is the Wood Between the Worlds in the book The Magician���s Nephew, which tells the creation story for Narnia, a wood described so enchantingly I sometimes think of it as a vision of peace still. It���s more serene and more strange than the busy symbolism in the rest of the books, with their talking beasts, dwarves, witches, battles, enchantments, castles, and more. The young hero puts on a ring and finds himself coming up through a pool to the forest.

'It was the quietest wood you could possibly imagine. There were no birds, no insects, no animals, and no wind. You could almost feel the trees growing. The pool he had just got out of was not the only pool. There were dozens of others -- a pool every few yards as far as his eyes cold reach. You could almost feel the trees drinking the water up with their roots. This wood was very much alive.'

"It is the place where nothing happens, the place of perfect peace; it is itself not another world but an unending expanse of trees and small ponds, each pond like a looking glass you can go through to another world. It is a portrait of a library, just as all the magic portals are allegories for works of art, across whose threshhold we all step into other worlds."

Words: The passage above is from The Faraway Nearby by Rebecca Solnit (Viking, 2013) -- a simply marvelous book, full of musing on many things, including fairy tales. I highly recommend it. It also appears in Solnit's article "A Childhood of Reading and Wandering" (Lit Hub, 2017). The poem in the picture captions is from Toasting Marshmallows by Kristine O���Connell George (Houghton Mifflin, 2001). All rights reserved by the authors.

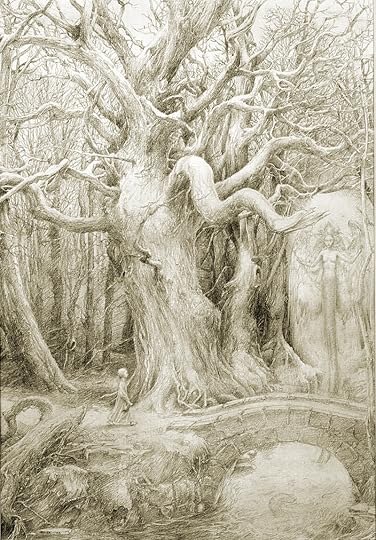

Pictures: The exquisite drawing above is "A Walk in the Woods" by my friend and neighbor Alan Lee, who is often inspired by the woods and rivers of Dartmoor. All rights reserved by the artist.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 712 followers