Terri Windling's Blog, page 74

September 12, 2018

Why stories are subversive

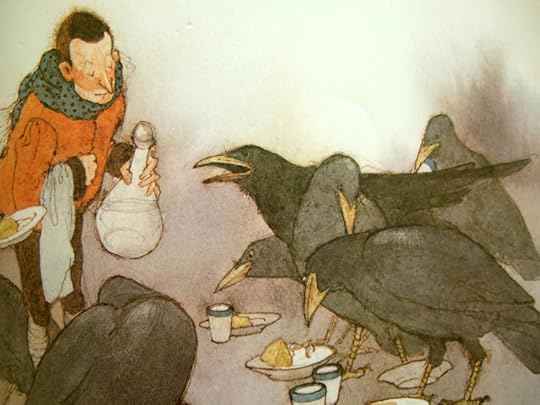

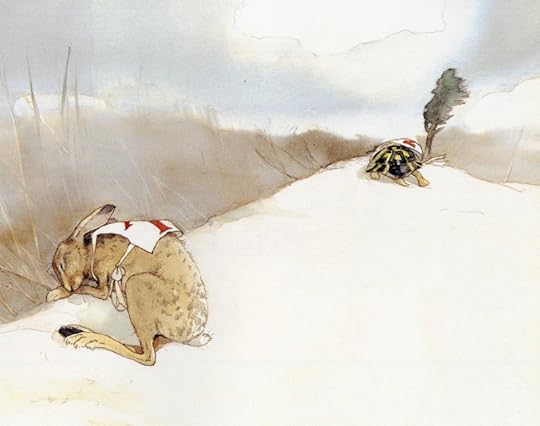

From "The Joys of Storytelling" by Ben Okri:

"Storytelling is always, quietly, subversive. It is a double-headed axe. You think it faces only one way, but it also faces you. You think it cuts only in one direction, but it also cuts you. You think it applies to others only, when it maintly applies to you. When you think it is harmless, that is when it springs its hidden truths, its uncomfortable truths, on you. It startles your complacency. And when you no longer listen, it lies silently in your brain, waiting.

"Stories are very personal things. They drift about quietly in your soul. They never shout their most dangerous warnings. They sometimes lend amplification to the promptings of conscience, but their effect is more pervasive. They infect your dreams. They infect your perceptions. They are always successful in their occupation of your spirit. And stories always have mischief in their blood.

"Stories, as can be seen from my choice of associate images, are living things; and their real life begins when they start to live in you. Then they never stop living, or growing, or mutating, or feeding the groundswell of imagination, sensibility, and character.

"Stories are subversive because they always come from the other side, and we can never inhabit all sides at once. If we are here, story speaks for there; and vice versa. Their democracy is frightening; their ultimate non-allegience is sobering. They are the freest inventions of our deepest selves, and they always take wing and soar beyond the place where we can keep them fixed.

"Stories are subversive because they always remind us of our fallibility. Happy in their serene and constantly-changing place, they regard us with a subtle smile. There are ways in which stories create themselves, bring themselves into being, for their own inscrutable reasons, one of which is to laugh at humanity's attempt to hide from its own clay. The time will come when we realize that stories choose us to bring them into being for the profound needs of humankind. We do not choose them....

"In a fractured age, when cynicims is god, here is a possible heresy: we live by stories, we also live in them. One way or another we are living the stories planted in us early or along the way, or we are living the stories we planted -- knowingly or unknowingly -- in ourselves. We live stories that give our lives meaning or negate it with meaninglessness.

"If we change the stories we live by, quite possibly we change our lives."

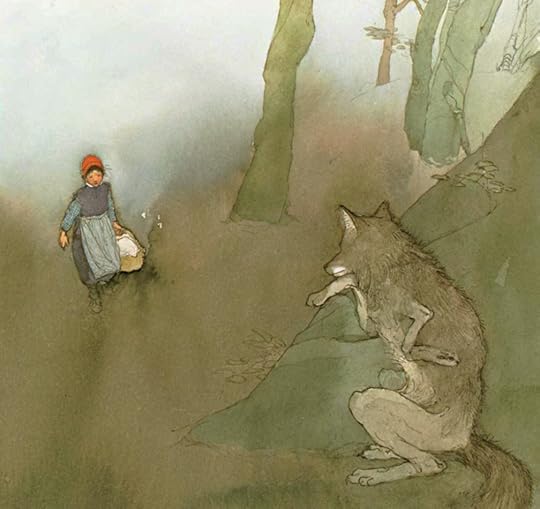

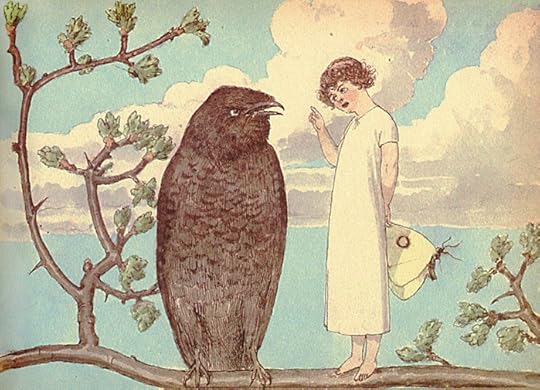

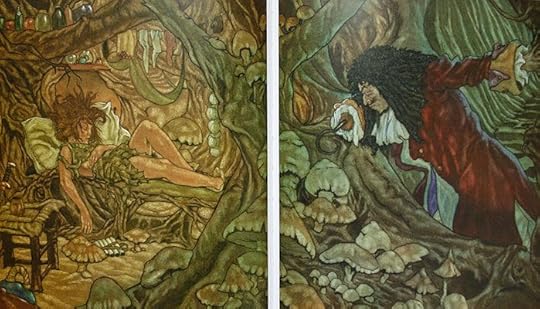

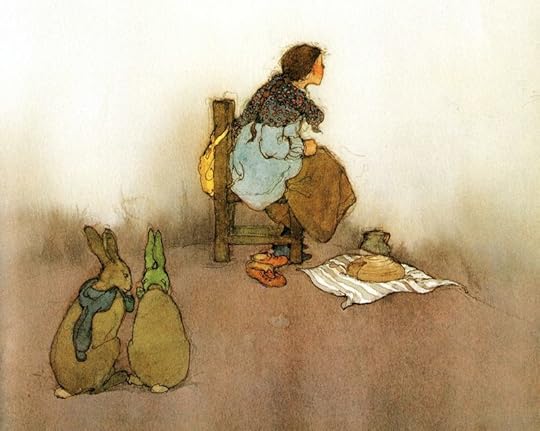

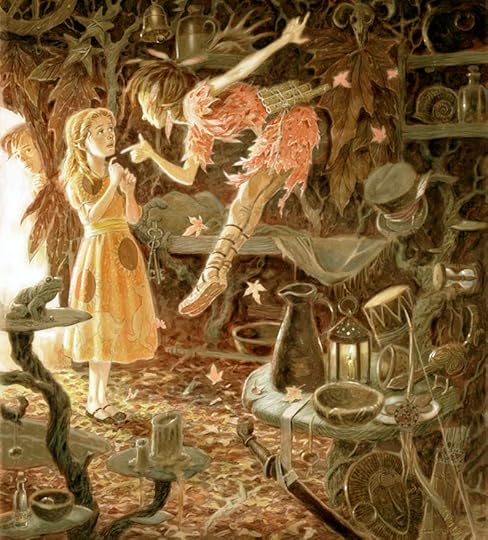

Pictures: The paintings above are by the great book artist Lisbeth Zwerger, who lives and works in Vienna, Austria. She has illustrated many editions of fairy tales and children's classics, and her work has been collected into two fine books: Wonderment and The Art of Lisbeth Zwerger. All rights reserved by the artist.

Words: The passage above is from "The Art of Storytelling I," from The Art of Being Free by Ben Okri (Phoenix House, 1977). All rights reserved by the author.

September 11, 2018

The gift blocked up

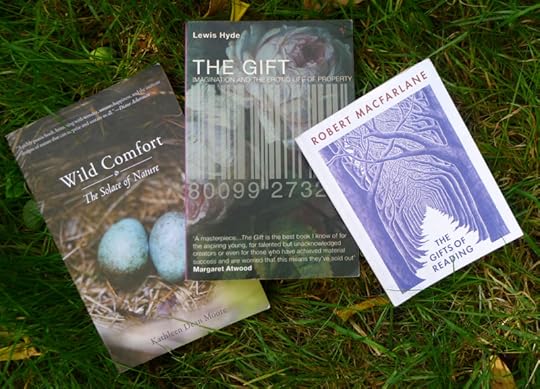

From The Gifts of Reading by Robert Macfarlane:

"Great art 'offers us images by which to imagine our lives' notes Lewis Hyde in his classic 1983 book, The Gift, '[and] once the imagination has been awakened it is procreative: through it we can give more than we were given, say more than we have to say.' This is a beautiful double-proposition: that art enlarges our repetoire for being, and that it further enables a giving onwards of that enriched utterance, that broadened perception.

"I was given a copy of Hyde's The Gift -- and I don't have that copy any longer, because I gave it to someone else, urging them to read it. Gifts give on, says Hyde, this is their logic. They are generous acts that incite generosity. He contrasts two types of 'property': the commodity and the gift. The commodity is the acquired and then hoarded, or resold. But the gift is kept moving, given onwards in a new form. Whereas the commodity circulates according to the market economy (in which relations are largely impersonal and conducted with the aim of profiting the self), the gift circulates according to the gift economy (in which relations are largely personal and conducted with the aim of profiting the other). In the market economy, value accrues to the individual by means of hoarding or 'saving.' In the gift economy, value accrues between individuals by means of giving and receiving. This, for Hyde, is why gifts possess 'erotic life,' as property: when we give a gift, it is an erotic act in the sense of eros as meaning 'attraction,' 'union,' a 'mutual involvement'....

"I am particularly moved by his deep interest in what he calls 'the gift that, when it comes, speaks commandingly to the soul and irresitably moves us.' The outcome of a gift is uncertain at the time of giving, but the fact that it has been given charges it with great potential to act upon the recipient for the good. Because the gratitude we feel, and because the gift is by definition given freely, without obligation, we are encouraged to meet it with openess and excitement. Unlike commodities, gifts -- in Hyde's account and my experience -- possess an exceptional power to transform, to heal and to inspire."

Lewis Hyde's The Gift was a seminal book for me when I first encountered it as a young writer, forming the way that I think about art: as a passing of gifts through the world, through time, and through the generations. I write and paint to make a living of course, to put food on the table and keep a roof overhead, but for me the first and most important impulse in the art-making process is, as Pablo Neruda once said, " to give something resiny, earthlike and fragrant in exchange for the gift of human brotherhood" ... to which I would add the gifts of sisterhood, and of a deeply cherished relationship with nature and the more-than-human world.

In a previous post on gift exchange I noted:

"Making art is a form of gift-giving, made wondrous by the way that some of our creations move outward far beyond our ken, gifting recipients we do not know, will never meet, and sometimes could never imagine. And I, in turn, have received great gifts from writers, painters, musicians, dramatists and others who will never know of my existence either, and yet their words, images, or ideas, coming to me at the right time, have literally saved me.

"The paradox inherent in making art, of course, is that it's an act involving both giving and receiving. Like breathing, it requires both, the inhalation and the exhalation. We receive the gift of inspiration (inhale), give it shape and form and pass it on (exhale)."

And yet somehow over the last few months, I seem to have lost the knack of breathing: the natural and mostly unconscious cycle of in and out that sustains my life. I was working...writing...but the work didn't flow. My regular morning posts for Myth & Moor slowed down to a trickle, then stopped altogether. My inbox filled with unanswered mail as my ability to communicate -- the very thing I've built my life and career upon -- seemed to vanish altogether. I can point to particular reasons why: Exhaustion. Medical problems, both time-consuming and worrying. Too many demands upon my time and attention, and too few spoons to distribute among them. The weariness of spirit caused by the constant assault of the daily news....It was all of those things and none of those things. I hadn't gone to ground intentionally; I kept trying to speak, and found myself dumb -- which is not a comfortable situation for a professional writer, a creature with language at her core. As novelist and poet May Sarton once wrote:

"The gift turned inward, unable to be given, becomes a heavy burden, even sometimes a kind of poison. It is as though the flow of life were backed up."

What has changed, then, since the silent summer months, allowing me to return to work and resume this blog?

This, too, is mysterious. Perhaps it's simply the turn of the season: the air growing crisp, the leaves turning gold, the reminder that nothing in nature stands entirely still. Perhaps is simply the need to breathe out after holding my breath for too damn long. Perhaps it's the way that the things that frighten us into paralysis -- medical issues or other life challenges -- eventually grow familiar, become the things you simply cope with, learn to fold into your days because you must...and life goes on...and the birds still sing...and the hound still wants her afternoon walk...and you find yourself speaking, once again, hesitantly at first, and then just a little louder...re-finding the words...re-finding yourself...until one day your fluency in your life's language returns.

"The earth offers gift after gift," writes Kathleen Dean Moore, "life and the living of it, light and the return of it, the growing things, the roaring things, fire and nightmares, falling water and the wisdom of friends, forgiveness. My god, the forgiveness, time, and the scouring tides. How does one accept gifts as great as these and hold them in the mind?"

By noticing them. By honoring them. By holding them close when the world goes dark, and passing them on when the light comes back.

The door of my studio stands open. Myth & Moor is back on schedule again. Autumn is here. I am moving forward, and I suddenly have so much to say.

September 9, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning

"When you tell a story or sing a song, you are the vehicle by which a tribe comes through you, and all your ancestors come here to help you..."

Above: "Go Away from My Window" performed by Iona Fyfe, from Aberdeenshire. Variants of this traditional song have been collected in northern Scotland and the Appalachian mountains of America. This version appears on Fyfe's gorgeous debut album, Away from My Window (2018).

Below: "Botany Bay" performed by Kelly Oliver, from Hertfordshire. This version of the ballad was collected by folk revivalist Lucy Ethelred Broadwood (1858-1928). It will appear on Oliver's third album, Bedlam, due out this month.

Above: "Chuir M���Athair Mise dhan Taigh Charraideach (My Father Sent Me to the House of Sorrow)" performed by The Furrow Collective: Lucy Farrell, Rachel Newton, Emily Portman, and Alasdair Roberts. This one's a waulking song from the Isle of Skye in the Inner Hebrides. It can be found on the quartet's second album, Wild Hog (2016).

Below: "A��� phiuthrag ���sa phiuthar (O Sister, Beloved Sister)" performed by Julie Fowlis, from North Uist in the Outer Hebrides. It tells the story of a young woman's search for her sister, stolen away by the s��thichean, or fairy-people. The song appears on Fowlis' latest album, Alterus, and features vocals by Mary Chapin Carpenter. The lovely animation is by Eleonore Dambre and Dima Nowarah.

Above: "The Outlandish Knight" (a variant of "Lady Isabela and the Elf Knight," Child Ballad #4) performed by Kate Rusby, from Yorkshire. The song appeared on her eleventh album, Ghost (2014).

Below: "False Light," a contemporary song in the ballad tradition by The Willows, from Cambridge. "It was written," they say, "after many misty walks around Wicken Fen, near to Ely. We love the folklore around these old tales surrounding the area, where atmospheric ghost lights, know as false lights, would lure people off the path, within the marshy reeds.��� The song will appear on their third album, Through the Wild, due out in November.

September 8, 2018

Myth & Moor update

Myth & Moor has been on an unscheduled hiatus due to health reasons. My apologies for the lack of updates. This blog will resume publication on Monday, September 10.

June 30, 2018

Away with the fairies

I'm heading up to Oxford University to participate in the Modern Faeries project organised by Fay Hield and Carolyne Larrington: an interdisciplinary gathering of folklorists, folk musicians, writers and artists, all focused on stories of the Twilight Realm and their meaning in modern life.

I'll tell you more about it when I'm back in Devon...or you can follow Modern Fairies on Twitter, where updates will be posted as it all gets up and running.

In the meantime, here's some fairy reading:

Fairies in Legend, Lore, and Literature

Italian Fairies: Fate, Folletti, and Other Creatures of Legend by Raffaela Benvenuto

Hungarian Fairies by Theodora Goss

Native American Fairies: Little People of the Southeast by Carolyn Dunn

Costa Rican Fairies: When My Hair was Woven with Duendes by Taiko Maria Haessler

June 18, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I've fallen in love with the music of Moria Smiley, an American singer, composer, and multi-instrumentalist whose influences range from classical choral compositions to bluegrass, gospel, and the folk traditions of eastern Europe and the British Isles. She's been doing excellent work for some years, but I've fallen hard for her extraordinary new album, Unzip the Horizon.

Since yesterday was Father's Day, let's begin with "Dressed in Yellow" (above), a song about a complex father/daughter relationship from Unzip the Horizon. Smiley is accompanied on vocals by the American roots duo Anna & Elizabeth.

"Wiseman" (below) is performed with the brilliant young English singer and folk song collector Sam Lee, influenced by the ballad-singing style Sam learned among the Travelling community of Britain. The backing musicians are: Dena El Saffar on violin/josa/viola, Joseph Phillips on bass, and Seamus Egan on percusssion.

These next two songs are among the many she's recorded in collaboration with other musicians.

Above: "John O'Dreams," written by Bill Caddick and performed by The Seamus Egan Project: Seamus Egan and Kyle Sanna on guitars, Jeff Hiatt on bass, Jon De Lucia on clarinet, and Smiley on banjo and vocals (2018).

Below: "Standing on the Shore," from the Irish/American band Solas, with Smiley stepping in on vocals. This recording appeared on the band's twelfth album, All These Years (2016).

And to end with, two more songs from Smiley's wide-ranging new album, Unzip the Horizon.

Above: "Refugee,"with backing vocals by Rising Appalachia and Krista Detor, accompanied by Vanessa Lucas-Smith on cello, Rekan on darkbuka, Joseph Phillips on bass, and Sola Akingbola on percussion. Explaining her inspiration for the song, Smiley writes: "My world was blown open in summer 2016 while volunteering at Calais Jungle refugee camp in France. I woke to culture and language completely beyond my understanding, and also the simple power of humans making beauty together -- from nothing."

Below: "Bring Me Little Water, Silvy," the classic Leadbelly song, arranged for voices and body percussion. The other performers are Ayo Awosika, Pilar Diaz, Sally Dworsky, Bella LeNestour, Courtney Politano, Moira Smiley, Ann Louise Thaiss, Maggie Wheeler, and Christine Wilson.

June 13, 2018

Stepping over the threshold

Returning to the theme of "books on books" (begun in a previous post), here's another passage from The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading by Francis Spufford:

"My favorite books were the ones that took books' implicit status as other worlds, and acted on it literally, making the window of writing a window into imaginary countries. I didn't just want to see in books what I saw anyway in the world around me, even if it was perceived and understood and articulated from angles I could never have achieved; I wanted to see things I never saw in life. More than I wanted books to do anything else, I wanted them to take me away. I wanted exodus. I was not alone. Tolkien believed that providing an alternative to reality was one of the primary properties of language. From the moment humans had invented the adjective, he wrote in On Fairy Stories, they had gained a creator-like power to build elsewheres.

" 'The mind that thought of light, heavy, grey, yellow, still, swift, also conceived of magic that would make heavy things light and able to fly, turn grey lead into yellow gold, and the still rock into swift water. If it could do the one, it could do the other; it inevitably did both. When we can take green from grass, blue from heaven, and red from blood, we have already an enchanter's power -- upon one plane; and the desire to wield that power in the world external to our minds awakes.'

"Anyone, he said, could use 'the fantastic device of human language' to mint a new coin for the imagination, such as the green sun. The green sun had no value, though, unless it was given a sky to rise in where it would have the same natural authority as the real yellow sun in the real sky. And after the sky, you had to invent the earth; and after the earth, the trees with their times of flowering and fruiting, and the inhabitants, and their habits of thought, and their manners of speech, their customs and clothing, down to the smallest details that labor and thought could contrive. To sustain a world inside which the green sun was credible required 'a kind of elvish craft ... story-making in its primary and most potent mode.'

"In fact Tolkien wanted to believe that fantasy was the highest form of art, more demanding than the mere reflection of men and women as they already were. He wanted to be able to look outward to story, and have it contain all that you might look inward to find, then more besides.

"But I knew there was a fundamental division between stories set entirely in another world, and stories that traveled out to another world from the everyday reality of this one. Some books I loved were in the first category. Tolkien himself, of course: the year I turned eight, I read The Lord of the Rings for the first time. [...] Later I discovered and cherished Ursula Le Guin's Earthsea novels. They were utterly different in feeling, with their archipelago of bright islands like ideal Hebrides, and their guardian wizards balancing light and dark like yin and yang. All they shared with Tolkien was the deep consistency that allows an imagined world to unfold from its premises solidly, step by certain step, like something that might really exist."

Yet the books that Spufford loved best were in the second category:

"...the ones that started in this world and took you to another. Earthsea and Middle Earth were separate. You traveled them in imagination as you read Le Guin and Tolkien, but they had no location in relation to this world. Their richness did not call you at home in any way. It did not lie just beyond a threshold in this world that you might find if you were particularly lucky, or particularly blessed.

"I wanted there to be the chance to pass through a portal, and by doing so pass from rusty reality with its scaffolding of facts and events into the freedom of story. If, in a story, you found that one panel in the fabric of the workaday world that was hinged, and it opened, and it turned out that behind the walls of the world flashed the gold and peacock blue of something else, and you were able to pass through, that would be a moment in which all the decisions that had been taken in this world, and all the choices that had been made, and all the facts that had been settled, would be up for grabs again: all possibilities would be renewed, for who knew what lay on the other side?

"And once opened, the door would never be entirely shut behind you either. A kind of mixture would begin. A tincture of this world's reality would enter the other world, as the ordinary children in the story -- my representatives, my ambassadors -- wore their shirts and sweaters amid cloth of gold, and said Crumbs! and Come off it! among people speaking the high language of fantasy; while this world would be subtly altered too, changed in status by the knowledge that it had an outside. E. Nesbit invented the mixing of the worlds in The Amulet, which I preferred, along with the rest of her magical series, to the purely realistic comedy of the Bastables' adventures in The Treasure Seekers and its sequels. On a grey day in London, Robert and Anthea and Jane and Hugh travel to blue sky through the arch of the charm. The latest master of worlds is Philip Pullman. Lyra Belacqua and her daemon walk through the aurora borealis in the first book of the Dark Materials trilogy; in the next, a window in the air floats by a bypass in the Oxford suburbs; in the third installment, access to the eternal sadness of the land of the dead is through a clapped-out, rubbish-strewn port town on the edge of a dark lake.

"As I read I passed to other worlds through every kind of door, and every kind of halfway space that could work metaphorically as a threshold too: the curtain of smoke hanging over burning stubble in an August cornfield, an abandoned church in a Manchester slum. After a while, I developed a taste for transitions to subtle that the characters could not say at what instance the shift had happened.

"In Diana Wynne Jones's Eight Days of Luke, the white Rolls-Royce belonging to 'Mr. Wedding' -- Woden -- takes the eleven-year-old David to Valhalla for lunch, over a beautiful but very ordinary-seeming Rainbow Bridge that seems to be connected to the West Midlands road system. I liked the idea that borders between the worlds could be vested in modern stuff: that the green and white signs on the motorways counting down the miles to London could suddenly show the distance to Gramarye or Logres.

"But my deepest loyalty was unwavering," Spufford states. "The books I loved best all took me away through a wardrobe, and a shallow pool in the grass of a sleepy orchard, and a picture in a frame, and a door in a garden wall on a rainy day at boarding school, and always to Narnia. Other imaginary countries interested me, beguiled me, made rich suggestions to me. Narnia made me feel like I'd taken hold of a live wire. The book in my hand sent jolts and shimmers through my nerves. It affected me bodily. In Narnia, C.S. Lewis invented objects for my longing, gave form to my longing, that I would never have thought of, and yet they seemed exactly right: he had anticipated what would delight me with an almost unearthly intimacy. Immediately I discovered them, they became the inevitable expressions of my longing. So from the moment I first encountered The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to when I was eleven or twelve, the seven Chronicles of Narnia represented essence-of-book to me. They were the Platonic Book of which other books were more or less imperfect shadows. For four or five years, I essentially read other books because I could not always be re-reading the Narnia books."

The American writer Lev Grossman was also ensorcelled by Narnia as a boy. In a fine essay on the subject he writes:

"The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is a powerful illustration of why fantasy matters in the first place. Yes, the Narnia books are works of Christian apology, works that celebrate joy and love -- but what I was conscious of as a little boy, if not in any analytical way, was the deep grief encoded in the books. Particularly in the initial wardrobe passage. There���s a sense of anger and grief and despair that causes Lewis to want to discard the entire war, set it aside in the favor of something better. You can feel him telling you -- I know it���s awful, truly terrible, but that���s not all there is. There���s another option. Lucy, as she enters the wardrobe, takes the other option. I remember feeling this way as a child, too. I remember thinking, 'Yes, of course there is. Of course this isn���t all there is. There must be something else.'

"How powerful it was to have Lewis come along and say, Yes, I feel that way, too.

"But I bristle whenever fantasy is characterized as escapism. It���s not a very accurate way to describe it; in fact, I think fantasy is a powerful tool for coming to an understanding of oneself. The magic trick here, the sleight of hand, is that when you pass through the portal, you re-encounter in the fantasy world the problems you thought you left behind in the real world. Edmund doesn���t solve any of his grievances or personality disorders by going through the wardrobe. If anything, they're exacerbated and brought to a crisis by his experiences in Narnia. When you go to Narnia, your worries come with you. Narnia just becomes the place where you work them out and try to resolve them.

"The whole modernist-realist tradition is about the self observing the world around you -- sensing how other it is, how alien it is, how different it is to what���s going on inside you. In fantasy, that gets turned inside out. The landscape you inhabit is a mirror of what���s inside you. The stuff inside can get out, and walk around, and take the form of places and people and things and magic. And once it���s outside, then you can get at it. You can wrestle it, make friends with it, kill it, seduce it. Fantasy takes all those things from deep inside and puts them where you can see them, and then deal with them."

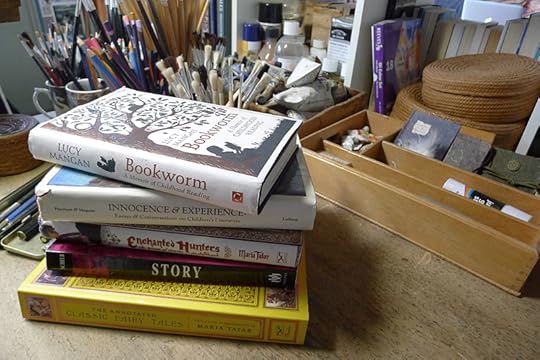

In Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading, Lucy Mangan reflects on the fourth book in the series, Prince Caspian:

"The Pevensies return to the magical kingdom to find that hundreds of years have passed, civil war is dividing the kingdom and Old Narnians (many dwarves, centaurs, talking animals, the dryads and hamadryads that once animated the trees, and other creatures) are in hiding. The children must lead the rebels against their Telmarine conquerors. The warp and weft of Narnian life is seen up close, in even more gorgeously imagined detail than the previous books. Lucy, awake one night in the thick of the forest that has grown up since she was last in Narnia, feels the trees are almost awake and that if she just knew the right thing to say they would come to Narnian life once more.

"It mirrored exactly how I felt about reading, and about reading Lewis in particular. I was so close...if I could just read the words on the page one more time, I could animate them too. The flimsy barriers of time, space and immateriality would finally fall and Narnia would spring up all around me and I would be there, at last."

Words: The passages above are from The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading by Francis Spufford (Henry Holt & Co, 2002); "Confronting Reality by Reading Fantasy" by Lev Grossman (The Atlantic, August 2014); and Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading by Lucy Mangan (Penguin, 2018); all rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The journey there and back again. Related posts: "Secret Threads," "Children, Reading, and Tough Magic", and "Ursula Le Guin on the Truth of Fantasy."

June 8, 2018

Myth & Moor update

My apologies once again for the recent paucity of posts. Having recovered (mostly) from this winter's long illness, I'm catching up on a mountain of missed work now...and I've also been traveling...and then recovering from traveling...and then catching up on that missed work again...and in the blink of an eye the entire spring has passed. I'll be away from home again weekend but back to the studio next week. If the Small Gods of Health and Fortune smile on me and all goes well, Myth & Moor will resume its regular publication schedule on Wednesday, June 13th.

During the time away, I've been reading, writing, thinking, and making notes for future Myth & Moor posts. I have so much to share with you.

Have a good and creative weekend everyone, and I'll be back with you very soon.

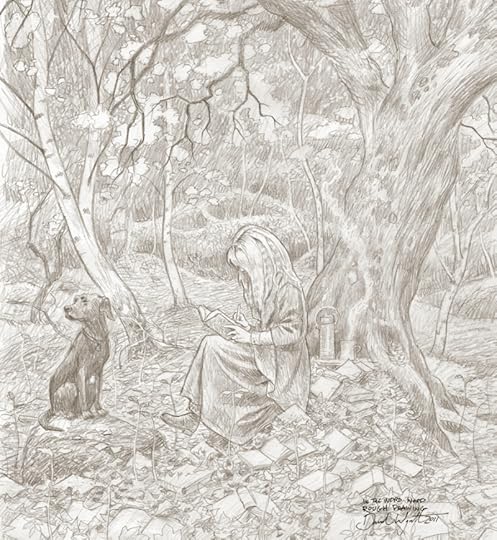

The drawing of me and Tilly above is, of course, by the great British book artist David Wyatt, an initial study for a painting in his gorgeous Mythic Village series. Photo: me and the hound on a bright June morning.

May 21, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm back from my travels, back to the studio, back in the good green hills of Chagford...and listening to ballads, old and new, on this quiet May morning.

Above: "Lark in the Clear Air," a traditional Irish song performed by Scottish folk musician Karine Polwart. Raised in Stirlingshire (between the lowlands and the highlands), she's now based in Edinburgh.

Above: "Lark in the Clear Air," a traditional Irish song performed by Scottish folk musician Karine Polwart. Raised in Stirlingshire (between the lowlands and the highlands), she's now based in Edinburgh.

Below: "All on a Summer's Evening," from Polwart's new album, A Pocket of Wind Resistance (with composer and sound designer Pippa Murphy). The song, she says, is "rooted in the ecology and history of my local heather moor by Fala Flow, Midlothian, south of Edinburgh. All on a Summer's Evening rests upon the traditional song Skippin Barfit Through the Heather. It's an introduction to the wide magical space of the moor, and to the story of a local couple, Will and Roberta Sime, which threads through the album."

Above: "The Driving of the Deer" (audio only), performed by Bella Hardy, a folk musician from the Peak District of Derbyshire. The song is about Sir William Peveril the Younger, a Norman knight reputed to be the grandson of William the Conqueror. (For the full story, go here.) Hardy found it in a 19th century collection, The Songs and Ballads of Derbyshire, and recorded her version on her fourth album, The Dark Peak and the Light (2014).

Below: "The Herring Girl," a song about an English girl who finds work as a herring packer in the Hebrides. It appeared on Hardy's third album, Songs Lost & Stolen (2011), featuring new ballads inspired by the old.

Above: "Geordie" (Child Ballad #209), performed by American folk musician Lindsay Straw, raised in Montana and now based in Boston. The song can be found on her second album, The Fairest Flower of Womankind (2017).

Below: "The Greg Selkie" (Child Ballad #113), performed by Maz O'Connor, a folk musician from the north of England. The song appeared on her first album, This Willowed Light (2014).

May 9, 2018

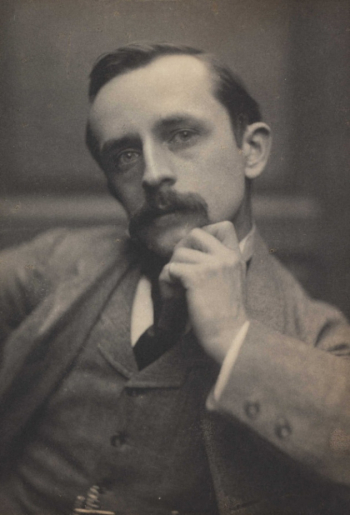

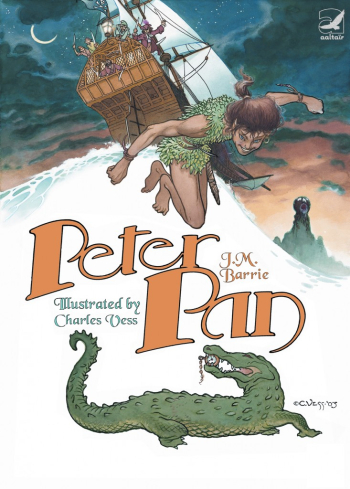

Happy Birthday, J.M Barrie!

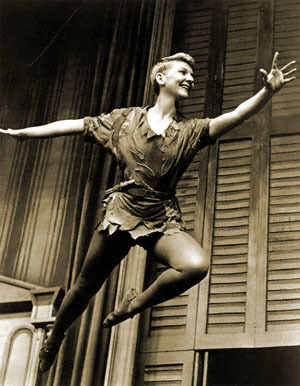

Charles Dickens once stated that Little Red Riding Hood was his first love, and if only he could have married her, he would have known perfect bliss. For me, my first love was Peter Pan -- that charming, exasperating rascal of a boy, killer of pirates and intimate of fairies.  But in my generation, we first encountered Peter as portrayed by the actress Mary Martin (in a televised version of the stage play Peter Pan), which created a certain gender confusion. Was Peter a boy (or girl) I had a crush on, or the dashing figure that I wanted to be myself? Play-acting the role of Wendy was boring, too much sewing and mothering of Lost Boys; play-acting Peter was so much better, strutting and scheming and fighting pirates. I dreamed of flight, and fairy dust, and Indian drums sounding in the woods; and insisted on leaving the bedroom window cracked in case Peter should appear.

But in my generation, we first encountered Peter as portrayed by the actress Mary Martin (in a televised version of the stage play Peter Pan), which created a certain gender confusion. Was Peter a boy (or girl) I had a crush on, or the dashing figure that I wanted to be myself? Play-acting the role of Wendy was boring, too much sewing and mothering of Lost Boys; play-acting Peter was so much better, strutting and scheming and fighting pirates. I dreamed of flight, and fairy dust, and Indian drums sounding in the woods; and insisted on leaving the bedroom window cracked in case Peter should appear.

On December 27, 2004, Peter Pan turned 100 years old. This piece is dedicated to him, and to his creator, the Scottish author Sir James M. Barrie.

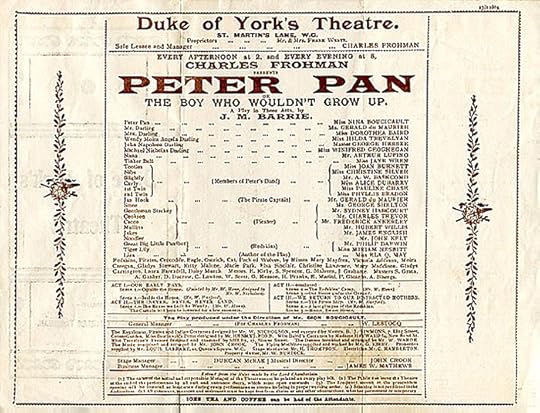

J.M. Barrie was already a well-known novelist and playwright when he sat down to write his first and only play for children, which he completed and offered to the theater producer Charles Frohman in the spring of 1904. It was unlike anything that had ever been presented to children on the London stage before, but Frohman loved it -- except for the title, which Barrie obligingly changed from The Great White Father to Peter Pan, the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up. ("Great White Father" is what Peter is called by Tiger Lily and her companions.) Although it had roots in the British pantomime tradition, Peter Pan was a wholly original concoction blending pirate stories, desert island stories, Indian adventures and fairy tales, all wrapped around a satire of family life in Edwardian London. Frohman took an enormous commercial risk in backing a play of over fifty parts and of actors wired to soar above the stage. No one knew if this preposterous play would work, especially its anxious author. On opening night, Barrie was ill with nerves, holding his breath at the critical moment when Peter asks the audience to clap their hands if they believe in fairies. What if no one clapped at all? But the audience responded with such wild applause that the actress playing Peter burst into tears.

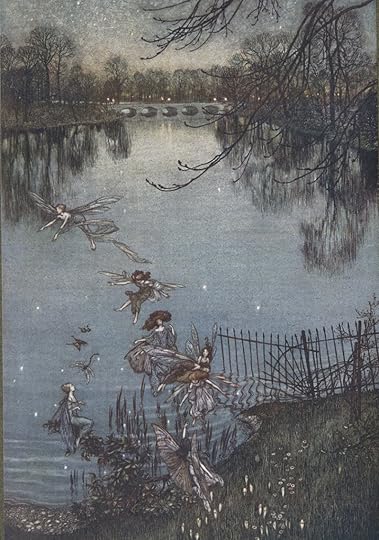

The opening of the play in December 1904 is now reckoned as the date of Peter's birth, for it marks the emergence of Peter as we know him, sword in hand and Tinker Bell at his side. Yet he really first appeared two years earlier in Barrie's adult novel The Little White Bird. The novel's narrator is a crusty bachelor who lives close to London's Kensington Gardens, where he meets a small boy and establishes an intense relationship with him. He charms the boy with stories about fairies, and about a run-away baby named Peter Pan who lives among the birds and fairies on an island in the Serpentine Lake.

All babies were once birds, he tells the boy, and they still possess the power of flight. Parents, he warns, must keep their windows shut so that their babies don't fly off at night. Peter Pan is a baby who once heard his mother talk about the life he'd lead when he was grown, prompting him to fly to Kensington Gardens in order to avoid this fate. In the Gardens, he's neither bird nor baby but a creature who is "betwixt and between," glorying in his independence, determined to never grow up. Eventually, however, he tries to go back home, only to find that he's left it much too late. His mother has another baby now, and the nursery windows are firmly locked.

All babies were once birds, he tells the boy, and they still possess the power of flight. Parents, he warns, must keep their windows shut so that their babies don't fly off at night. Peter Pan is a baby who once heard his mother talk about the life he'd lead when he was grown, prompting him to fly to Kensington Gardens in order to avoid this fate. In the Gardens, he's neither bird nor baby but a creature who is "betwixt and between," glorying in his independence, determined to never grow up. Eventually, however, he tries to go back home, only to find that he's left it much too late. His mother has another baby now, and the nursery windows are firmly locked.

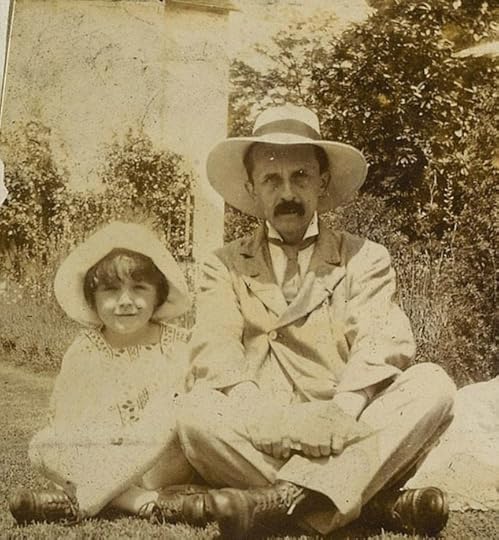

The Little White Bird, like most of Barrie's work, drew inspiration from the author's own life. He too lived close to Kensington Gardens, where he walked with his enormous St. Bernard dog, and where he first became friends with three little boys: George, Jack, and Peter Llewelyn Davies. Barrie held the boys spellbound with tales about magical goings-on in the park at night, when fairies emerged from the hollows of the trees, leaving messages for the boys to find. The first "Peter" in these stories was the real baby Peter, flying off from the Llewelyn Davies nursery to join the fairies' revels at night -- but soon a separate character emerged of the fairy-child Peter Pan, who had once been a human baby, but now lived in the wilds of the park. Barrie was an intensely autobiographical writer, mining his own life for story material to a degree that alternately charmed and exasperated the friends and family members who found themselves rendered into novels and plays. Thus to understand Peter Pan, we must take a closer look at his creator and his complicated relationship with the Llewelyn Davies family.

Born in Kirriemuir, Scotland in 1860, James Barrie was the frail, unprepossessing seventh child in a family of ten. His father was a hand-loom weaver, and although the family was far from affluent, they were comfortable, and good educations were provided for the Barrie boys. The eldest son, Alexander, graduated from Aberdeen University with first-class honors in Classics; and the next son, David, a brilliant boy, was expected to do even better. James, however, was a dreamy child more interested in games and Penny Dreadfuls (adventure comics) than excelling in academics. David was the acknowledged star of the family -- but when David was thirteen and James was six, David died in a skating accident. Their mother never recovered from this blow, and James spent the rest of his childhood trying to replace the boy she'd lost. He distracted his mother by begging for stories about the Scotland of her childhood (and would later make a good living turning these stories into articles and books). David remained enshrined in memory as the perfect child who never aged or disappointed. "Nothing that happens after we are twelve matters very much," J.M. Barrie wrote many years later.

Yet the years from ages thirteen to eighteen seem to have been the happiest of Barrie's own life, when he left his home and grieving mother to attend Dumfries Academy. Though Dumfries was co-educational, Barrie lived in a masculine world of sports, games, and intense friendships with other boys. He was small and thin, but good at football, cricket, fishing, and other sports, and especially at games of make believe involving pirates, bandits, and other stock characters from the Penny Dreadfuls. These games evolved into a Dramatic Club, establishing Barrie's life long devotion to the theater. He wrote his very first play for the club, a melodrama called Bandelero the Bandit.

Barrie knew from quite an early age that he wanted to be a professional writer, but his mother had other plans for him. He was to follow the path that David would have taken to a career in the ministry. Barrie dutifully went off to earn his M.A. at Edinburgh University, where he was miserable. He had been popular among the boys in Dumfries, but at university he was at a loss. He was an odd looking young man, barely five feet tall, and appeared much younger than he was. The women ignored him, and the men embarrassed him with coarse talk about the opposite sex. Barrie retreated into solitude, turning shy and reticent, which were traits he'd retain even when he'd become the most successful writer in Great Britain.

Barrie knew from quite an early age that he wanted to be a professional writer, but his mother had other plans for him. He was to follow the path that David would have taken to a career in the ministry. Barrie dutifully went off to earn his M.A. at Edinburgh University, where he was miserable. He had been popular among the boys in Dumfries, but at university he was at a loss. He was an odd looking young man, barely five feet tall, and appeared much younger than he was. The women ignored him, and the men embarrassed him with coarse talk about the opposite sex. Barrie retreated into solitude, turning shy and reticent, which were traits he'd retain even when he'd become the most successful writer in Great Britain.

Barrie obliged his parents by completing his degree, but returned home still determined to be a writer, landing a job with the Nottingham Journal and sending submissions off to the London papers. The St. James Gazette began to publish Barrie's stories of Scotland in his mother's day, and with this slim encouragement he moved to London at the age of 24. He went with little money and few contacts, and yet within a very few years Barrie's work was appearing regularly in the top newspapers and journals in the country. He published three books about old Scotland -- Auld Licht Idylls, A Window in Thrums, and The Little Minister -- which turned into surprise best-sellers, elevating him in literary circles and opening society's doors. Barrie's boyhood idol Robert Louis Stevenson proclaimed him to be a writer of genius, and Barrie's circle of friends now included Thomas Hardy, Henry James, William Meredith, Arthur Conan Doyle, and P.G. Wodehouse.

Barrie then turned his hand to writing plays, scoring successes with Ibsen's Ghost and Walker, London. He loved the theater -- and he also loved to flirt with the pretty starlets of the day, although he never went beyond flirting until he met a young woman named Mary Ansell. Mary's career on the stage was undistinguished but she was lively and intelligent, and as the two grew close, the London society papers predicted an engagement. Mary waited while Barrie dithered about her. He worried that he was unsuited to marriage -- as a child he'd even had nightmares about it -- and the notes in his journals from the period show a man who is wracked with doubt. He loved Mary, but did he love her deeply? Was he capable of a steady, adult love? He worried that the answer was no, but hoped that the act of marriage would mature him -- so he proposed to Mary, married her in Scotland, and took her off on a Swiss honeymoon. The honeymoon was not a success, and Mary later referred to it as "a shock." Barrie's biographers suspect (as did many of his friends) that the marriage was never consummated -- for he seems to have been an entirely asexual man, incapable of physical passion. In a journal entry recorded during his honeymoon he makes this note for a scene in a future play:

Wife-Have you given me up? Have nothing to do with me?

Husband calmly kind, no passion & c. (�� la self)

When the couple returned to London, Mary busied herself with their new house and dog, while Barrie retreated into his study and got back to work. He produced new stories, new plays, a sentimental biography of his mother -- and then began Tommy and Grizel, considered by many to be his finest novel. It's the tragic story of Tommy, a writer, who is married to his childhood friend Grizel. The marriage is not a happy one, for there's something vital lacking in Tommy -- he cannot love Grizel, or any woman, as he knows a woman ought to be loved. He's not like other men, he tries to explain, he's really just a boy who has never grown up. Barrie writes, "She knew that, despite all he had gone through, he was still a boy. And boys cannot love. Oh, is it not cruel to ask a boy to love?...He gave her all his affection, but his passion, like an outlaw, had ever to hunt alone."

As Barrie's biographers have remarked, one can only imagine what Mary thought when she read passages like this in print, realizing that anything she said or did might be turned into story material. But if Mary minded, she didn't show it. She carefully, dutifully kept up the public appearance of a perfectly normal marriage. There were compensations. She was wealthy now, and her husband was a celebrated man. If she didn't have his passion, and couldn't have his children, at least she had as much of Barrie's affection and attention as he had to give until, in 1897, she began to lose even that.

For it was in 1897 that Barrie became acquainted with the three little boys in Kensington Gardens: five-year-old George, four-year-old Jack, and baby brother Peter, who came to play in the park each day attended by their nanny. They talked about cricket, pirates, and fairies; he dazzled them by the way he could wiggle his ears; and before long, Barrie was meeting up with boys on a regular basis. He had always found it easier to make friends with children than he did adults. They didn't mind his moods, his long silences; they enjoyed his black humor and quirky stories, and accepted him as an overgrown boy rather than as one of the grown-ups.

For it was in 1897 that Barrie became acquainted with the three little boys in Kensington Gardens: five-year-old George, four-year-old Jack, and baby brother Peter, who came to play in the park each day attended by their nanny. They talked about cricket, pirates, and fairies; he dazzled them by the way he could wiggle his ears; and before long, Barrie was meeting up with boys on a regular basis. He had always found it easier to make friends with children than he did adults. They didn't mind his moods, his long silences; they enjoyed his black humor and quirky stories, and accepted him as an overgrown boy rather than as one of the grown-ups.

On New Year's Eve, the Barries attended an elegant dinner party where Barrie was seated beside the beautiful wife of a young barrister. He soon discovered, to his astonishment, that this was Sylvia Llewelyn Davies, the mother of his friends George, Jack, and Peter -- while she discovered, with equal amazement, that the mysterious man who could wiggle his ears was the famous author J.M. Barrie.  Sylvia was no stranger to fame herself, for her father was George du Maurier, illustrator for Punch magazine and author of the novel Trilby (which introduced Svengali to the world); her brother Gerald was a well-known actor; and her husband Arthur was the son of John Llewelyn Davies, a prominent theologian. Sylvia was charmed by Barrie's enthusiasm for her beloved boys, and invited him to visit them at home -- which he promptly did, reappearing there with increasing regularity.

Sylvia was no stranger to fame herself, for her father was George du Maurier, illustrator for Punch magazine and author of the novel Trilby (which introduced Svengali to the world); her brother Gerald was a well-known actor; and her husband Arthur was the son of John Llewelyn Davies, a prominent theologian. Sylvia was charmed by Barrie's enthusiasm for her beloved boys, and invited him to visit them at home -- which he promptly did, reappearing there with increasing regularity.

Soon Barrie was a fixture in Sylvia's household -- to the chagrin of her husband Arthur, who could not fathom why this strange little Scotsman was so constantly underfoot, and of Mary Barrie, disconcerted by this new focus in her husband's life. Neither Arthur nor Mary had cause to believe that Sylvia and Barrie had embarked on an affair (and Mary, especially, knew how impossible this was), but the intensity of Barrie's interest in Sylvia's boys raised more than a few eyebrows. Sylvia, however, found nothing strange in it. Completely in love with her handsome husband, she saw nothing compromising in accepting Barrie's friendship, and nothing odd in his devotion to her darling sons. She pushed Arthur's objections aside, and Arthur learned to hold his tongue, accepting Barrie's presence in their lives with as much stoicism as he could muster. Barrie's wife, for her part, made a point of befriending Sylvia and coped as best she could with the awkward fact that her husband was engrossed in the lives of another woman's children.

The question inevitably rises in relation to Barrie's involvement with the Llewelyn Davies boys whether he was a pedophile, or had repressed pedophilic tendencies. Nico Llewelyn Davies, the youngest of the boys, when asked about this after Barrie's death, dismissed the idea categorically. "I don't believe that Uncle Jim ever experienced what one might call 'a stirring in the undergrowth' for anyone -- man, woman, or child," said Nico. "He was an innocent -- which is why he could write Peter Pan." Writer Andrew Birkin, who spent three years researching Barrie's life for his BBC television program The Lost Boys, interviewed many who had known J.M. Barrie and conducted an extensive correspondence with Nico. Nothing he read or heard indicated that Barrie had a sexual interest in the boys. "Barrie was impotent, it's fairly clear," says Birkin (on the DVD edition of his program). "That was the tragedy of his life. Had he not been impotent, I think he would have been a womanizer ��� he was always falling in love with his leading ladies over the stage lights. The suggestion that he was somehow pedophilic with these boys doesn't really stand up to close examination."

In 1900, Sylvia gave birth to Michael, who would grow to be Barrie's favorite of her sons ��� but for now it was still George, the eldest, who was the child closest to his heart. Barrie's novel The Little White Bird (1902) is transparently based upon his relationship with George. Captain W., the novel's protagonist, meets a charming little boy in Kensington Gardens, and he sets out to win the affections of both the boy and his beautiful mother.

Like much of Barrie's fiction, the novel is too sentimental to suite most modern tastes (though saved by the delicious bite of Barrie's humor), and the intensity of the narrator's obsession with the boy makes for uncomfortable reading in our less innocent age. But this tribute to children and childhood  was exactly suited to the temper of its day. "To speak in sober earnest," proclaimed the London Times, "this is one of the best things that Barrie has written���.If a book exists that contains more knowledge and more love of children, we do not know it." George was proud of inspiring the novel (even though it earned him teasing from his school fellows), and Sylvia loved it. What Arthur and Mary felt about the book is not recorded.

was exactly suited to the temper of its day. "To speak in sober earnest," proclaimed the London Times, "this is one of the best things that Barrie has written���.If a book exists that contains more knowledge and more love of children, we do not know it." George was proud of inspiring the novel (even though it earned him teasing from his school fellows), and Sylvia loved it. What Arthur and Mary felt about the book is not recorded.

In 1903, Sylvia became pregnant with Nicholas (called Nico), her fifth and final child. The day before Nico's birth, Barrie started work on Peter Pan. Unlike baby Peter in The Little White Bird, this Peter would be an older boy who lived in distant Never Land (called Neverland or Never-never Land in some editions), where he'd have the adventures that Barrie had so often play-acted with Sylvia's children. Barrie set the first scene in the Darling house on a shabby street in Bloomsbury -- "but you may dump it down anywhere you like," he wrote, "and if you think it was your house, you are very probably right." The beautiful Mrs. Darling was modeled on Sylvia, and the perfidious Mr. Darling, rather unfairly, on Arthur. Barrie later explained to the Llewelyn Davies boys that Peter was made "by rubbing the five of you violently together, as savages with two sticks produce flame. That it is all he is, the spark I got from you."

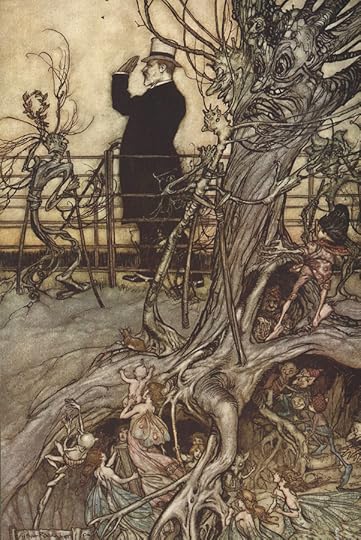

Other sparks came from Scottish fairy stories -- which Barrie would have heard or read in his youth, particularly as he was a fan of the writer and folklore enthusiast Sir Walter Scott. The fairy stories that he drew upon, however, weren't sugar-sweet Victorian confections about tiny butterfly-winged sprites, but older, darker stories about the dangerous fairies of the Scottish folk tradition. In these tales, seductive, heartless fairies lure children into the fairy realm, an enchanted world that lies at the heart of the woods, or underneath the Scottish hills. Time passes differently in that realm. A single night spent with the fairies might be a hundred years in human time -- so when the children go back home again, their parents are dead and gone.

In changeling tales, the fairies snatch infants and pretty children from their beds, whisking them off to fairyland as pampered pets, companions, or slaves. Sometimes a fairy is left behind, glamored to look like the stolen child: a bad-tempered, sickly, hungry creature who is a plague to the human parents. The lost children in changeling tales don't always find their way back home. Sometimes they stay under the hills, losing all memory of the mortal world -- just as John and Michael Darling forget their parents while living in Never Land.

In changeling tales, the fairies snatch infants and pretty children from their beds, whisking them off to fairyland as pampered pets, companions, or slaves. Sometimes a fairy is left behind, glamored to look like the stolen child: a bad-tempered, sickly, hungry creature who is a plague to the human parents. The lost children in changeling tales don't always find their way back home. Sometimes they stay under the hills, losing all memory of the mortal world -- just as John and Michael Darling forget their parents while living in Never Land.

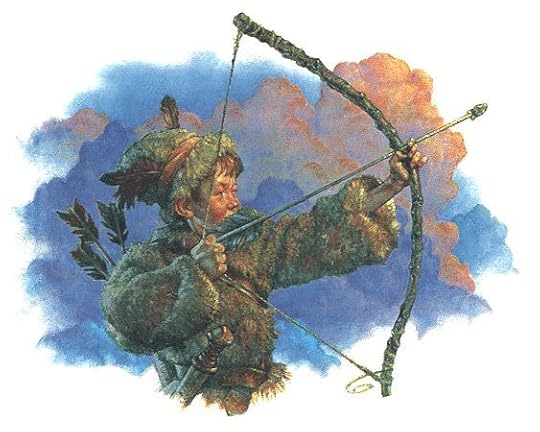

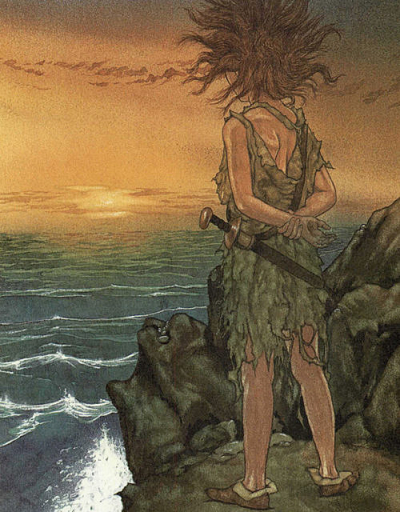

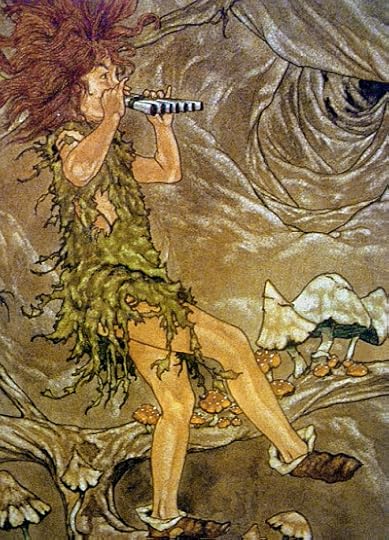

Barrie's Peter Pan is human-born, not a fairy, but he's lived in Never Land so long that he's as much a fairy as he is a boy: magical, capricious, and amoral, like the fairies of the old Scots tradition. He's a complex mixture of good and bad, with little understanding of the difference between them; both cruel and kind, thoughtless and generous, arrogant and tender-hearted, bloodthirsty and sentimental. He is a classic trickster character -- kin to Puck, Robin Goodfellow, and other delightful but exasperating sprites of fairy lore. He's a liminal creature, standing on the threshold between fairy and child, mortal and immortal, villain (when he lures children from their homes) and hero (when he rescues them from pirates).

Peter's last name derives from the Greek god Pan, the son of the trickster god Hermes by a wood nymph of Arcadia. Pan is a creature of the wilderness, associated with vitality, virility, and ceaseless energy. In the ancient writings of Servius we find this detailed description: Pan is "formed in the likeness of nature with horns to resemble the rays of the sun and the horns of the moon; his face is ruddy in the imitation of ether; he wears a spotted fawn skin resembling the stars in the sky; his lower limbs are hairy because of the trees and the wild beasts; he has the feet of a goat to resemble the stability of  the earth; his pipe has seven reeds in accordance with the harmony of heaven; his pastoral staff bears a crook in reference to the pastoral year which curves back on itself; and finally he is the god of all nature." Pan's young namesake does not have goat legs or horns, but he does ride on the back of a goat, and he plays the pan-pipes, an instrument Pan invented from hollow reeds.

the earth; his pipe has seven reeds in accordance with the harmony of heaven; his pastoral staff bears a crook in reference to the pastoral year which curves back on itself; and finally he is the god of all nature." Pan's young namesake does not have goat legs or horns, but he does ride on the back of a goat, and he plays the pan-pipes, an instrument Pan invented from hollow reeds.

Like Peter, the god Pan is a contradictory figure. He haunts solitary mountains and groves, where he's quick to anger if he's disturbed, but he also loves company, music, dancing, and riotous celebrations. He is the leader of a woodland band of satyrs ��� but these "Lost Boys" are a wilder crew than Peter's, famed for drunkenness, licentiousness, and creating havoc (or "panic"). Pan himself is a distinctly lusty god -- and here the comparison must end, for Peter's wildness has no sexual edge. Indeed, it's sex and the other mysteries of adulthood that he's specifically determined to avoid. ("You mustn't touch me. No one must ever touch me," Peter tells Wendy.)

Barrie added three girls to Peter's story (over the Llewelyn Davies boys' initial objection): Wendy Darling, the fairy Tinker Bell, and the Indian princess Tiger Lily. "Wendy" was a nonexistent name at the time. It came from a child named Margaret Henley who referred to Barrie as her "friendy" -- but she couldn't pronounce her "f"s and "r"s, and so the word came out as "Wendy". (Due entirely to Barrie's play, Wendy soon became a popular name for little girls.) Tinker Bell was originally called Tippy in the earliest drafts of the play, and Tiger Lily's tribe is called the Piccaninnies -- a name mercifully left out of modern renditions. (Barrie's Indians are fantasy Indians, "savages" imagined by Edwardian children, and have as much to do with actual Indians as Nanna the dog has to do with actual nannies.) Captain Hook comes directly from the make-believe games that Barrie played with George and his brothers, as well as from the pirates in the Penny Dreadfuls that Barrie loved as a child. Hook was first portrayed on the London stage by Gerald du Maurier (Sylvia's brother), who brought such menace to the role that children were carried screaming from the stalls. "How he was hated," recalled his daughter, the novelist Daphne du Maurier, "with his flourish, his poses, his dreaded diabolical smile! That ashen face, those blood-red lips, the long, dank, greasy curls; the sardonic laugh, the maniacal scream, the appalling courtesy of his gestures." Hook's villainy was never entirely played for laughs -- he was allowed to be a truly menacing figure, saving the role from pure camp and adding gravity to Peter's story.

While Barrie was busy with the enormous task of making this extravagant fantasia work on stage, Arthur Llewelyn Davies made a sudden move and relocated his family to Berhamsted, twenty-five miles away from London. Barrie still came to visit them, but he could no longer be a daily presence. Instead, he wrote wistful letters to the boys as he hovered anxiously around the theater, watching his actors learn to fly and Peter Pan come to life. Peter himself was played by a young starlet (Nina Boucicault in the first London production, Maude Adams in New York) -- largely because of labor laws preventing child actors from working after 9 pm, but also because of the British pantomime tradition in which the Principal Boy was always played by a girl. Great secrecy surrounded the Peter Pan rehearsals, which of course made the press and the public all the more eager to learn what Barrie had up his sleeve. On opening night (December 27, 1904), Sylvia and the boys came into town to accompany the nervous author to the theater. Back in New York, producer Charles Frohman waited to learn if he had a hit or a disaster. Finally a cable came. Peter Pan was an overwhelming success. The critics were charmed, and (more importantly to Barrie) an audience full of children had been enthralled. So many little children were injured, however, by going home and jumping from the furniture that he hastily rewrote the opening scene to explain that fairy dust was required to fly.

With this new success, Barrie was busier than ever. He visited Sylvia and the boys as often as his schedule would allow ��� but the family was happily settled in Berkhamsted, and Barrie was busy back in London with new stories, new plays, and a variety of political and charitable causes. Then, in 1906, disaster struck. Arthur was diagnosed with cancer, requiring an operation that would remove half of his jaw and palate. Barrie was immediately at his side, dropping everything to put himself at Arthur's assistance, as well as quietly picking up the cost of his expensive medical treatment. When the operation was completed, Arthur's face was a ruin and he could barely speak. Barrie remained posted at his bedside ��� nursing him, reading to him, conversing with him (as Arthur slowly communicated by writing). Arthur found Barrie kinder and wiser than he expected, and the relationship between the two men changed. When Arthur came home from the hospital, Barrie was a welcome (and necessary) presence in the household. The two families spent their summer holidays together, and everyone insisted that Arthur was getting better, but by autumn the tumor had spread, and by the following spring, Arthur was dead.

Arthur left little money behind, so now Barrie took over the family's support. He had earned a small fortune from Peter Pan and insisted it was theirs as much as his. Sylvia brought the family back to London, to a house near Barrie and Kensington Gardens. "And here, I think, Sylvia did succeed, gradually, in regaining something of the zest for life," wrote Peter Llewelyn Davies, years later, about his mother. "The boys were a fond amusement and distraction for her, relatives came frequently, and the dog-like J.M.B. still living at Leinster Corner and in constant attendance��� Everything must have been done, by all who had the care of us and above all by Sylvia herself, to shut out the imp of sorrow and self-pity from our young lives."

Arthur left little money behind, so now Barrie took over the family's support. He had earned a small fortune from Peter Pan and insisted it was theirs as much as his. Sylvia brought the family back to London, to a house near Barrie and Kensington Gardens. "And here, I think, Sylvia did succeed, gradually, in regaining something of the zest for life," wrote Peter Llewelyn Davies, years later, about his mother. "The boys were a fond amusement and distraction for her, relatives came frequently, and the dog-like J.M.B. still living at Leinster Corner and in constant attendance��� Everything must have been done, by all who had the care of us and above all by Sylvia herself, to shut out the imp of sorrow and self-pity from our young lives."

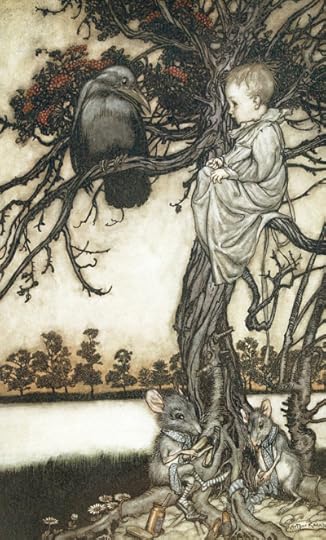

Daily life went on. Barrie continued to write, and Peter Pan continued to cast its spell, becoming the most famous of Barrie's works. The tale of Peter Pan as a baby, originally published in The Little White Bird, was now available in a separate children's book edition, called Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, with illustrations by Arthur Rackham. The script of the play was published under the title Peter Pan, the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up; and eventually Barrie novelized the story of the play in a book titled Peter and Wendy. He ended this volume with a brand new scene in which Peter comes back to Wendy's window years later, and discovers she is all grown up. The little girl in the nursery now is Wendy's daughter, Jane. The girl examines Peter with interest, and soon she's off to Never Land herself where her mother can no longer go, no matter how much she longs to follow.

Meanwhile, Barrie's relationship with the Llewelyn Davies family took its inevitable toll on his marriage, and he learned that his wife was having an affair with a young writer named Gilbert Cannan. He begged Mary to break it off, but this she had no intention of doing. Cannon had pledged to marry her, and she wanted a divorce. Barrie disappeared to Switzerland while the scandal raged in the London papers, then returned to London in October for the ordeal of the divorce proceedings. Two days after the case was over, Sylvia collapsed at home. Now she, too, was diagnosed with cancer, in a form impossible to treat. As was the practice of the time, she was not allowed to know how ill she was, though as the illness went on and on and on, she suspected that she was dying. She remained in bed until the following spring, seemed to be improve a little in the summer, and insisted on taking her sons on a fishing holiday to Devon. While the boys fished, she grew weaker and weaker. The children were not told she was dying. She passed away on August 27th, with her mother and Barrie in the room, and Barrie was left to break the news to the boys as they returned from the river.

Barrie now assumed all responsibility for the boys. The elder three were at Eton by this time, where their school fees had long been paid by Barrie, but Michael and Nico remained at home supervised by their nanny, Mary Hodgson, with Barrie living close by. Barrie was now an extremely wealthy man and he lavished money on his young wards ��� on clothes, books, sports equipment, and extravagant summer holidays; nothing was too good for them that might the ease the grief of losing their parents. Michael was the most like Barrie of all the boys ��� a dreamy, fey, creative child, and Michael was as excessively attached to Barrie as Barrie was to him. At Eton, Michael wrote to Barrie every day. There were more than two thousand letters between them ��� most of them later burned by Peter (the family archivist), who was embarrassed by their sentimentality.

Barrie's literary star continued to rise, and he was awarded a baronetcy in 1913 in recognition of his status as one of the best loved authors in Britain. George started university that year, where he remained on close terms with his guardian, but Jack, who was in the Navy now, and more independent than his brothers, resented the dominant role that Barrie had taken in their lives. The following year, Barrie took all of the boys except Jack to Scotland for a fishing holiday (Jack was on a ship in the North Atlantic), and it was there that they learned the news that England was now at war with Germany. George and Peter, like so many young men, immediately signed up to defend their country, and by December George's battalion was posted to the Western Front. With The Little White Bird packed in his kit-bag, he departed for the trenches of France, sending fond and cheerful letters back to Barrie and urging him not to worry. In March, George sent a letter from the Front saying, "Keep your heart up, Uncle Jim, & remember how good an experience this is for a chap who's been very idle before. Lord, I shall be proud when I'm home again, & talking to you about all this. That old dinner at the Savoy will be pretty grand���." By the time the letter reached London, George Llewelyn Davies had been shot and killed.

"I have lost all sense I ever had of war being glorious," Barrie wrote in one of his last letters to George, "it is just unspeakably monstrous to me now." Sylvia's brother Gerald (the original Captain Hook) also died that year in the mud of France; and Charles Frohman drowned shortly thereafter in the sinking of the Lusitania. Barrie despaired, fearing the war would swallow everything and everyone he loved ��� but peace was declared before Michael came of age, and Jack and Peter came safely home. Peter never fully recovered from horrors he witnessed at the Front; he struggled with depression for the rest of his life, and committed suicide many years later. For now, however, life went on. Jack married a girl he'd met while stationed in Scotland. Nico, the youngest, left home for Eton. Michael started at Oxford University, where he cut a dazzling figure. His close friend (and probable lover) Roger Stenhouse introduced him into Lytton Strachey's Bloomsbury circle, where Strachey pronounced him "the only young man at Oxford or Cambridge with real brains." Michael was handsome, brilliant, a gifted writer, and seemed to have the world before him. And just before his twenty-first birthday, he drowned in a boating accident.

"I have lost all sense I ever had of war being glorious," Barrie wrote in one of his last letters to George, "it is just unspeakably monstrous to me now." Sylvia's brother Gerald (the original Captain Hook) also died that year in the mud of France; and Charles Frohman drowned shortly thereafter in the sinking of the Lusitania. Barrie despaired, fearing the war would swallow everything and everyone he loved ��� but peace was declared before Michael came of age, and Jack and Peter came safely home. Peter never fully recovered from horrors he witnessed at the Front; he struggled with depression for the rest of his life, and committed suicide many years later. For now, however, life went on. Jack married a girl he'd met while stationed in Scotland. Nico, the youngest, left home for Eton. Michael started at Oxford University, where he cut a dazzling figure. His close friend (and probable lover) Roger Stenhouse introduced him into Lytton Strachey's Bloomsbury circle, where Strachey pronounced him "the only young man at Oxford or Cambridge with real brains." Michael was handsome, brilliant, a gifted writer, and seemed to have the world before him. And just before his twenty-first birthday, he drowned in a boating accident.

Like his mother, undone by the death of her son David, Barrie never fully recovered from Michael's loss, particularly since it came on the heels of losing Arthur, Sylvia, George, Gerald du Maurier, and Charles Frohman. He aged visibly, and for a long while barely had the will to go on living. But go on he did, supported by his affection for his three remaining "Lost Boys," and eventually for their children too ��� a brand new audience to charm with stories of pirates, Indians, and fairies. He continued to write, to socialize, to travel, to stay active in charitable and political causes, until he died in 1937, with Peter and Nico at his bedside. "To die will be an awfully big adventure," Barrie once wrote in the voice of Peter Pan. In his will, he left the Peter Pan royalties to the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children.

When Barrie commissioned the Peter Pan stature by Sir George Frampton that stands in Kensington Gardens to this day, he hoped it would allow Peter to be remembered long after his play was forgotten. But one hundred years later, Peter is just as popular as ever, and there are few children who don't know his story ��� through picture books, through the Disney animation, and through the recent live-action film, if not directly from Barrie's play or the pages of Peter and Wendy.

Peter's story has inspired several other works of fiction for both children and adults, and Barrie's life has inspired two dramatic productions: the excellent BBC television series The Lost Boys, and the film Finding Neverland.

Peter's story has inspired several other works of fiction for both children and adults, and Barrie's life has inspired two dramatic productions: the excellent BBC television series The Lost Boys, and the film Finding Neverland.

Finding Neverland is a charming but heavily fictionalized concoction, playing fast-and-loose with the facts of Barrie's life in order to tell a simpler, more romantic story. Here, Arthur is conveniently dead before Barrie meets Sylvia, and Sylvia's mother is turned into a villain, attempting to keep Barrie and Sylvia apart. The boys are reduced from five in number to four, and are portrayed as older when they first meet Barrie. (In real life, Peter was just a baby.) In the film, it's Peter (not the eldest, George) who is portrayed Barrie's special friend; and Peter again, not the middle boy, Michael, who shares Barrie's dreamy temperament and interest in writing. The biggest change is that handsome, charismatic Johnny Depp plays the part of the Scottish playwright, depicting him as a gentle, fey dreamer, rather than the odd little sharp-edged man that he actually was. But the movie has moments of magic, the period sets and costumes are lovely, and overall it is worth seeing, provided it's taken with many grains of salt.

Andrew Birkin's television series The Lost Boys, on the other hand, is specifically based on the known facts of J.M. Barrie's life, drawn from a vast array of surviving journals, correspondence, manuscripts, and photographs, as well as extensive interviews with those had known James Barrie. The last of the Lost Boys, Nico Llewelyn Davies, read and advised on Birkin's script ��� and when the final production was broadcast, Llewelyn Davies phoned up Birkin in tears, "undone," he said, by the way actor Ian Holm had turned into his Uncle Jim. (The series is available on DVD, and I highly recommend it. I also recommend Birkin's web site, where he generously makes a treasure trove of Barrie material -- journals, letters, story notes, photographs, etc. -- freely available to fans and scholars.)

Andrew Birkin's television series The Lost Boys, on the other hand, is specifically based on the known facts of J.M. Barrie's life, drawn from a vast array of surviving journals, correspondence, manuscripts, and photographs, as well as extensive interviews with those had known James Barrie. The last of the Lost Boys, Nico Llewelyn Davies, read and advised on Birkin's script ��� and when the final production was broadcast, Llewelyn Davies phoned up Birkin in tears, "undone," he said, by the way actor Ian Holm had turned into his Uncle Jim. (The series is available on DVD, and I highly recommend it. I also recommend Birkin's web site, where he generously makes a treasure trove of Barrie material -- journals, letters, story notes, photographs, etc. -- freely available to fans and scholars.)

James M. Barrie was a boy who couldn't grow up, and out of this conundrum he gave us Peter, the boy who wouldn't grow up -- a character so vivid, so universal, and so emotionally true that he seems to belong to folklore now, not to one author's imagination. One hundred years later, children still dream of flying off with Peter to Never Land, where they'll never bathe, or eat broccoli, or (the worst fate of all) have to grow up.

A few years ago I knew a little boy who referred to adults, like me, as "human beings". "Aren't you a human being too?" I asked. With a look of scorn for the stupidity of my question, he answered, "I'm not a human being, I'm a child." When I pointed out that one day he would grow up to be a human too, he shook his head and insisted, "No. I'm going to stay a boy."

J.M. Barrie would have perfectly understood the desire to stay a boy forever -- and advised him to keep his window open, so that Peter Pan could find him.

To learn more about Barrie, I recommend J.M. Barrie and the Lost Boys by Andrew Birkin (Yale University Press reprint, 2003); J.M. Barrie: The Man Behind the Image by Janet Dunbar (Collins, 1970); The Peter Pan Chronicles by Bruce K. Hanson (Carol Publishing, 1993); "The Boy Who Couldn't Grow Up: James Barrie" by Alison Lurie (in Don't Tell the Grown-ups, Back Bay Books reprint, 1998); Barrie: The Story of J.M.B. by Denis Mackail (Ayer Co. reprint, 1977); and Letters of James M. Barrie by Viola Meynell (Norwood Editions, 1942).Artists are identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights reserved by the artists or their estates.

To learn more about Barrie, I recommend J.M. Barrie and the Lost Boys by Andrew Birkin (Yale University Press reprint, 2003); J.M. Barrie: The Man Behind the Image by Janet Dunbar (Collins, 1970); The Peter Pan Chronicles by Bruce K. Hanson (Carol Publishing, 1993); "The Boy Who Couldn't Grow Up: James Barrie" by Alison Lurie (in Don't Tell the Grown-ups, Back Bay Books reprint, 1998); Barrie: The Story of J.M.B. by Denis Mackail (Ayer Co. reprint, 1977); and Letters of James M. Barrie by Viola Meynell (Norwood Editions, 1942).Artists are identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights reserved by the artists or their estates.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 712 followers