Terri Windling's Blog, page 56

July 13, 2019

The stories we need

After spending the last week basically dissing Disney's treatment of classic stories, here's a post from the Myth & Moor archives looking at Disney retellings from a different perspective, positing that bad books (and films) created for children aren't always bad for children....

���Just as the child is born with a literal hole in its head, where the bones slowly close underneath the fragile shield of skin, so the child is born with a figurative hole in its heart. Slowly this, too, is filled up. What slips in before it anneals shapes the man or woman into which that child will grow. Story is one of the most serious intruders into the heart." - Jane Yolen

As a folklorist, fantasist, and passionate advocate for the value of fairy tales, I have written many articles and talks over the years about the fairy tales I loved as a child and how they've permeated my creative life ever since. I've spent less time thinking about the other tales that colored my childhood, especially those from the earliest years, tales read to me before I could read for myself -- tales that, whatever their objective value as literature, "intruded into the heart" during that formative time.

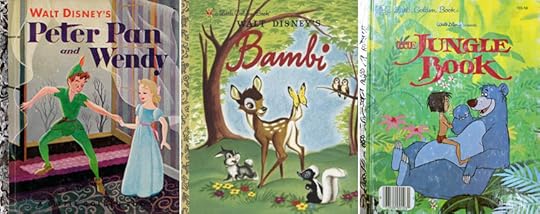

I wish I could say my young mind was nourished on the classics of children's literature -- the original text of J.M Barrie's sly and sardonic Peter and Wendy, for example -- but like so many children growing up in the '60s I had a Peter-Pan-simulacrum, not Peter himself: a small picture book with a re-written text that had been greatly slimmed down and simplified, based on Walt Disney's Peter, not Barrie's. Likewise for Felix Salten's Bambi, Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book, and so many other classics in 1960s adapations: they all seemed to bear Disney's stamp, whether or not Disney Studios had ever actually made films out of them.

I loathe such books now. And yet, I confess, as a child I swallowed them whole. The timeless magic of stories like Peter's runs deep, no matter how badly re-tellings may ravage them. I know from my taste in fairy tales -- where I had the luck to be raised on the old, unwatered-down versions -- that I would have preferred the original texts, even when the language sailed over my head; but I took what was offered, and loved Imitation Peter and Imitation Thumper and Imitation Baloo nonetheless.

My memory of my pre-reading years is patchy, but my memory of the books I adored is not, the stories entwined with the sound of my mother's voice as she read them to me at bedtime. She worked during the day, and these were among the rare moments I had her all to myself, and when she seemed contented to be with me, not sadly bewildered by my existence.

What I know today, and did not know then, is that my mother was still just a child herself, having dropped out of high school when I came along (the result of a love affair gone wrong) and living under her own mother's roof. Her room was a frilly teenager's bedroom. I had the little bedroom next door, where through the thin walls I could hear the sound of her crying, night after night. I thought I was the cause of those tears, an unwanted baby who had ruined her life. Much later I learned the rest of the story: there had been a second love affair, and a second baby after me, a son, who had been taken away. Now those years of her bottomless grief made sense. But these clarifying details were hidden from the puzzled child I was, and in the tale that I wove from my ignorance I was the source of her misery and her shame, and the fact that I could not break through her sorrow seemed to confirm this as truth.

We lived at that time with my grandmother, my step-grandfather, and the three young daughters of that marriage: my aunts, but barely older than me and so they seemed more like sisters. I adored them, followed them everywhere (when they let me), and longed to sleep in their dorm-like room at the top of the house, instead of in my bed with my head under the pillows to block out my mother's crying. Is it any wonder that the first great love of my life was Peter Pan? I insisted on keeping the window cracked open at night, in all kinds of weather, but I never said why. I was waiting for Peter. I wanted to fly to the stars and away. I was certain he would come.

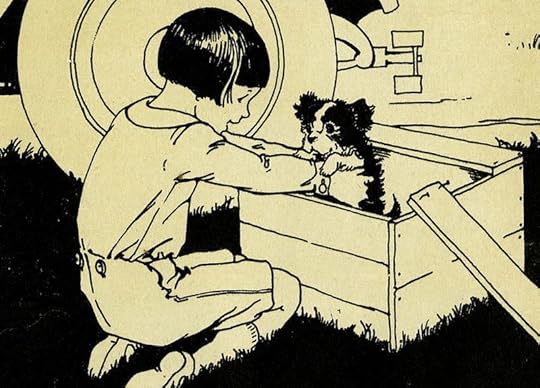

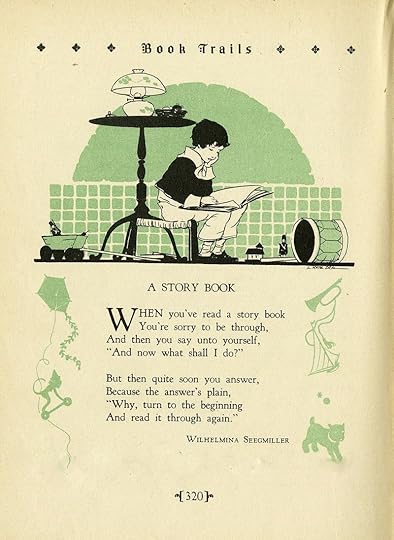

In addition to those dreadful Disney editions, when storytime came around at night I often requested the "red books": a children's anthology series from the 1920s that lived on my mother's shelves, not mine, for they'd been hers as a child, and she loved them, and I wasn't to touch them. (Or, god forbid, to color in them -- but of course I did and spent a whole week in disgrace.) When my mother died (again, much too young) the books came to me, and I still have them today: an eight volume series called Book Trails, published by Shepard & Lawrence in 1928.

Two things about these books strike me now. First, they are filled with poems and tales of Victorian and Edwardian vintage, full of children who lived in day and night nurseries, attended by nannies and servants, aired in perambulators and fed strange meals called "tea" (at which, I imagined, only the beverage of that name was served). In this way, I received a literary education more common to children of my mother's, and even my grandmother's, day. I can still quote reams of poetry by Walter de la Mare and Robert Louis Stevenson by heart...along with plenty of sickly-sweet late-Victorian rhymes that no one else has heard of now.

Second, I am struck by the fact that the tales I remember as favorites are all, every one of them, variations on a single theme: an unprepossessing child, or puppy, or princess, or fairy is overlooked, unwanted, or has no home...but by story's end they are claimed, loved, and recognized for their inherent worth.

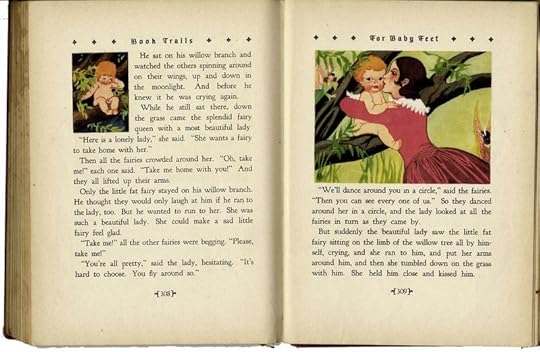

One story I asked for again and again is a saccharine take on the Ugly Duckling theme, "The Little Fat Fairy" by Florence S. Page. In this tale, there's a little fairy so chubby and clumsy that he can't fly like his fellow fairies, or dance properly, or do much of anything at all. The other fairies tease him and he tries not to mind, but he knows there is something horribly wrong with him and he's deeply ashamed. One day a Lovely Lady comes to the forest looking for a fairy companion. They dance around her, all calling "Choose me! Choose me!" Each one is more beautiful than the next, and the Lovely Lady can't make up her mind...until she spies the fat fairy above her in the trees, hiding his ugliness from her.

"Oh you dear little thing," she cries. "I want you!"

The other fairies are shocked. "Why would you want him? He's so fat he can't dance or anything!"

"That's because he's a baby, not a fairy," says the woman. "He's a beautiful baby boy! And I'm going to be his mother."

It's embarrassing reading the tale today, so cloyingly sweet, so heavy-handedly moral. And yet, I admit, this silly story still makes my heart catch in the same old way. I am in my 50th decade now, but that unwanted child is still at my core. To be seen, to be valued, to be claimed without hesitation...that's a powerful magic indeed, and it doesn't matter that the tale is so badly written. The child I was didn't know that, or care. I read it now and I'm transported back: to that room, to that bed, to the window cracked open, to the nightly sobs of my teenage mother. And the waiting, the waiting, for someone to claim me. Peter Pan. Lovely Lady. Anyone.

It's unsettling to write these words. Not because of painful emotions evoked -- I've made my peace with my past after all these years -- but because I'm a writer myself now, and these stories are challenging my deepest convictions. I believe it's important to write well for children; to create fantasy that is complex and true, not didactic tales or frivilous fancies steeped only in bathos and wish-fulfillment. Yet the sugary stories of the "red books" were true for me at that time, and I did not distinguish good writing from poor. I took what I needed, and if the tales were simplistic in the telling, they became something more in the hearing.

"I don't think there is such a thing as a bad book for children," says my wise friend Neil Gaiman. "Every now and again it becomes fashionable among some adults to point at a subset of children's books, a genre, perhaps, or an author, and to declare them bad books, books that children should be stopped from reading. I've seen it happen over and over; Enid Blyton was declared a bad author, so was RL Stine, so were dozens of others. Comics have been decried as fostering illiteracy. It's tosh. It's snobbery and it's foolishness. There are no bad authors for children, that children like and want to read and seek out, because every child is different. They can find the stories they need to, and they bring themselves to stories. A hackneyed, worn-out idea isn't hackneyed and worn out to them. This is the first time the child has encountered it."

"I don't think there is such a thing as a bad book for children," says my wise friend Neil Gaiman. "Every now and again it becomes fashionable among some adults to point at a subset of children's books, a genre, perhaps, or an author, and to declare them bad books, books that children should be stopped from reading. I've seen it happen over and over; Enid Blyton was declared a bad author, so was RL Stine, so were dozens of others. Comics have been decried as fostering illiteracy. It's tosh. It's snobbery and it's foolishness. There are no bad authors for children, that children like and want to read and seek out, because every child is different. They can find the stories they need to, and they bring themselves to stories. A hackneyed, worn-out idea isn't hackneyed and worn out to them. This is the first time the child has encountered it."

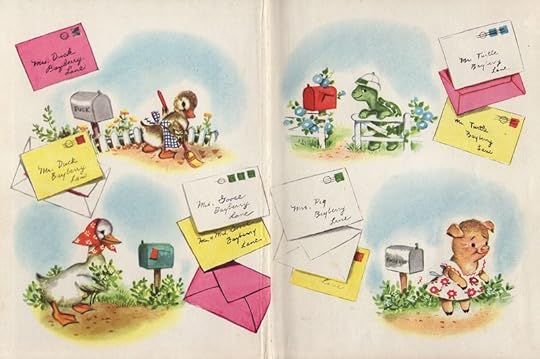

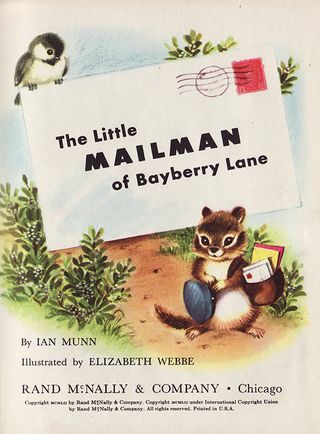

Another "bad book" I loved without reservation was The Little Mailman of Bayberry Lane by Ian Munn, published in 1953 and dismissed by reviewers as "sticky sentiment" even then. I can't say that assessment is wrong, but as a small child in the early '60s this book was my sacred text: profound, transcendent, and necessary. The story is simple. Mrs. Pig is the only animal on Bayberry Lane who never receives any mail. Each day she waits by her mailbox, hopeful, and each day the kind-hearted  Little Mailman, a chipmunk, witnesses her disappointment. Distressed by Mrs. Pig's loneliness, the Little Mailman comes up with a plan. The next day, everyone on the lane gets an invitation to a party...except poor Mrs. Pig, who is now sadder than ever. It turns out, of course, that the big event is a surprise party thrown by the mailman for her, after which she has so many friends that her mailbox never stands empty again.

Little Mailman, a chipmunk, witnesses her disappointment. Distressed by Mrs. Pig's loneliness, the Little Mailman comes up with a plan. The next day, everyone on the lane gets an invitation to a party...except poor Mrs. Pig, who is now sadder than ever. It turns out, of course, that the big event is a surprise party thrown by the mailman for her, after which she has so many friends that her mailbox never stands empty again.

Polly Pig, as depicted by illustrator Elizabeth Webbe, is quietly sad and quietly sweet -- descriptions I could also apply to my mother. No Mr. Pig is ever mentioned (another similarity), and she seems undeserving of the loneliness that suffuses her life until the Little Mailman comes along. I might easily have been a more selfish child, rejecting my mother and her suffocating sorrow, adding to the burden of grief she carried; but instead, through the Little Mailman, I learned about kindness, empathy, emotional generosity. If only I could be half so clever as he, I too might devise an ingenious plan to bring happiness back into my mother's life. I tried, and I tried, and I never succeeded. Her problems were larger than Mrs. Pig's. But the compassion that I learned from that "sticky sentimental" story I carry with me to this day.

None of these are tales I would choose to grow up with. Nor would I would give them to a child now when there are so many better stories to offer, both classic and contemporary. Yet I craved these books, asked for them over and over, and found their sugary sweetness nourishing to my soul. As a writer, I cannot approve of them. They are not, by any measure of the writing craft, good: they are simplistic, soppy, and (in the case of the Disneyfied picture books) inauthentic. They are everything that as an artist I deplore.

Yet they made me the person and writer I am. And I love them still.

Words: The quote by Jane Yolen is from her excellent book Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Childhood (Philomel, 1981). The quote by Neil Gaiman is from "Why our future depends on libraries, reading and daydreams (The Guardian, October 15, 2013). Pictures: The images are identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the pictures to see them.) The illustrations from the Book Trails series (Lawrence & Shepard, 1928) are, alas, not credited by artist.

The strange history of Snow White

To end this week's series of posts on folk and fairy tales:

Another discussion of Disney's fairy tale films can be found in "The Poisoned Apple," my essay on the history of Snow White. (It's available online here.) With this tale, too, the filmmakers made sweeping changes that both Americanized and altered the essence of the story.

"It's just that people now don't want fairy stories the way they were written," Walt Disney said in answer to such criticism. "They were too rough. In the end they'll probably remember the story the way we film it anyway."

Alas, I'm afraid he was right.

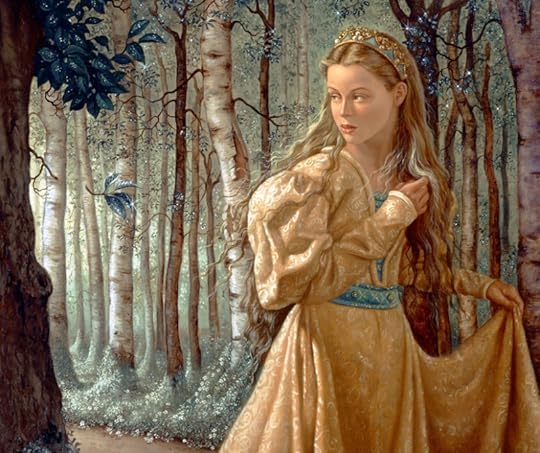

Art above: Snow White by Trina Schart Hyman (1974) and from the Disney animated film (1937).

July 11, 2019

The stuff that dreams are made of

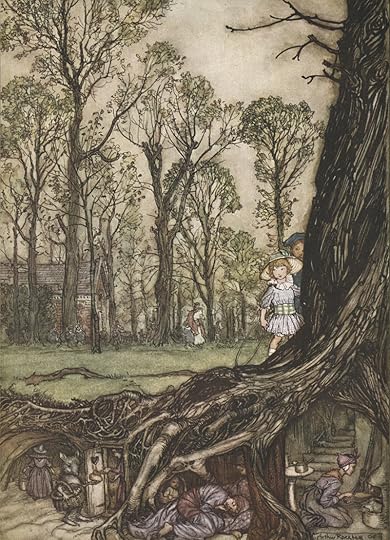

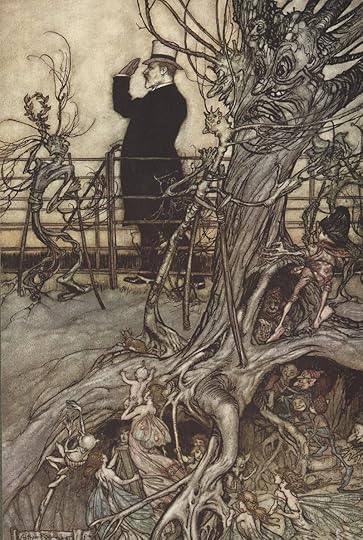

Today, one last passage passage from Jane Yolen's seminal book Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Chilhood, which no folklore library should be without. The art, of course, is by great Golden Age book illustrator Arthur Rackham.

"Though we are just now finding out that the dinosaur was probably a warm-blooded beast and not the cold-blooded lizard of the textbooks," Jane writes, "we have never been in doubt about dragons. We know, even without being told, that they were born, nourished, kept alive by human blood and heart and mind. They never were -- but always will be. It was Kenneth Grahaeme who wrote: 'The dragon is a more enduring animal than a pterodactyl. I have never yet met anyone who really believed in pterodactyls; but every honest person believes in dragons -- down in the back-kitchen of his consciousness.'

"Dragons and pterodactyls, actuality has nothing to do with Truth.

"Throughout the 19th century, there was a great deal of speculation about fairies. One group of anthropologists and folklorists held that there really had been a race of diminutive prehistoric people who had been driven underground by successive invasions. These 'little folk,' who were really the size of pygmies, supposedly lived for years in communities in caves and burrows, in warrens and tunnels and in the deepest, darkest parts of the forest where, in brown-and-green camoflage, they stayed apart from their enemies. Kidnappings and mysterious disappearances were all attributed to them. These hardy guerrillas of a defeated culture became, in the folk mind, the elves and gnomes and trolls of the British Isles. There were even archeologists wo were convinced they had discovered rooms underground in the Orkney Islands that resembled the Elfland in the popular ballad Child Rowland. (And, similarly, other folk stories might have emerged by a misunderstanding of the weirs and dikes used by the Romans for their household baths.)

"It is a very seductive thesis, but it really begs the question. For even if we do conclusively prove that the Picts or Celts or some other smaller-than-average race are the actual precursors of the fairy folk, it will not really change a thing about those wonderful stories. The tales of Elfland do not stand or fall on their actuality but on their truthfulness, their speaking to the human condition, the longings we have for the Faerie Other. Those are the tales that touch our longing for the better, brighter world; our shared myths, our shaped dreams. The fears and longings within each of us that helped us create Heaven and Elysium, Valhalla and Tir nan og.

"This is the stuff that dreams are made of. Not the smaller dreams that you and I have each night, rehearsals of things to come, anticipation or dread turned into murky symbols, pastiches of traumas just passed. These are the larger dreams of humankind, a patchwork of all the smaller dreams stitched together by time.

"The best of the stories we can give our children, whether they are stories that have been kept alive through the centuries by that mouth-to-mouth resuscitation we call oral transmission, or the tales that were made up only yesterday -- the best of these stories touch that larger dream, that greater vision, that infinite unknowing. They are the most potent kind of magic, these tales, for they catch a glimpse of the soul beneath the skin."

Words: The passage above is from the title esssay in Touch Magic by Jane Yolen (Philomel, 2981; August House, 2000). The poem in the picture captions, also by Jane, was first published in The National Storytelling Journal (Winter 1987). All rights to the text and art are reserved by the author and the Rackham estate.

Related reading: Jane Yolen on children and tough magic, Alison Hawthorne Deming on dragons, and me on fairies in legend, lore, and literature.

July 10, 2019

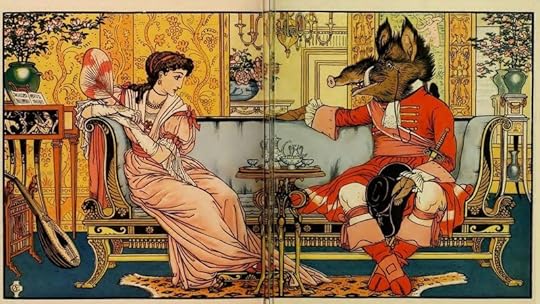

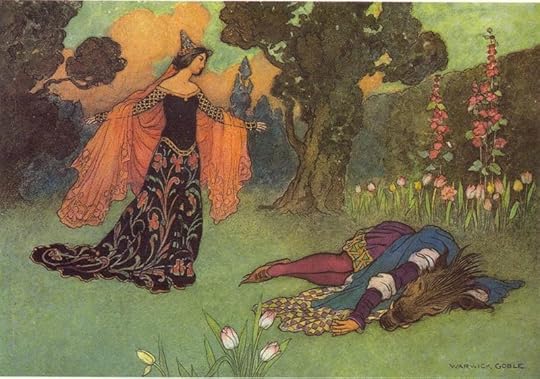

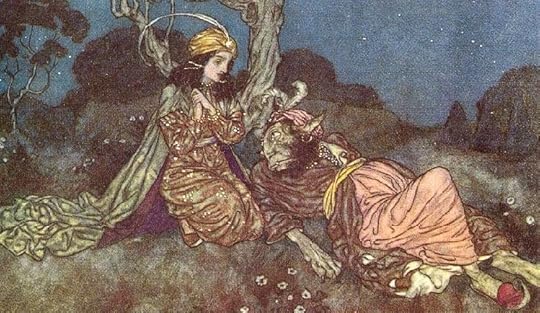

Retelling Beauty & the Beast

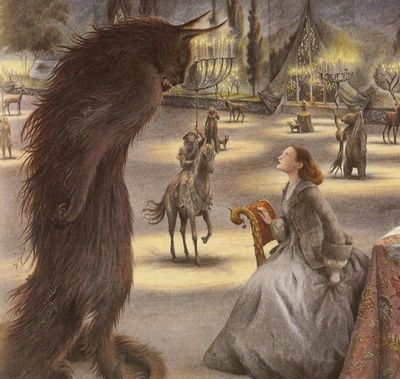

When I first saw Disney Studio's Beauty and the Beast, it was in the company of a five-year-old friend. The film was, of course, a visual delight: the animation was remarkable, the Broadway-musical-style show tunes were lively and witty, the Beast was sufficiently ugly and endearing, and Beauty, bless her, was a rare media heroine who actually read books. As with many of the best stories for children, my young companion and I both enjoyed the film, even if we were laughing at different jokes. Nonetheless, I found myself disturbed by Disney's treatment of the fairy tale -- specifically, with the liberties taken in changing classic elements of the story. But where, I wondered, do we draw the line between the use and abuse of fairy tales when creating new versions for modern audiences? Fairy tales aren't museum pieces to be preserved under glass, after all -- they are living stories: retold, reshaped, subverted, fractured, turned inside-out and upside-down by storytellers of each generation. So why did the Disney film seem to me not so much a fresh rendition of the story as a sloppy muddling of it? A look at the history of the tale will give some context to my dismay.

While we generally think of fairy tales as anonymous stories handed down from the distant past, Beauty and the Beast, in fact, is a literary work penned by the French writer Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve in 1740. De Villeneuve was part of the "second wave" of French fairy tale writers (Madame D'Aulnoy, Charles Perrault, and other salon fairy tale writers comprising the "first wave" fifty years earlier). When she sat down to create Beauty and the Beast, she was influenced by those earlier salonni��res, as well by Apuleius' "Cupid and Psyche" (published in his Golden Ass) and by the many animal -bridegroom legends to be found in the folk tradition. Like Madame D'Aulnoy and other salonni��res before her, Villeneuve used the metaphorical language of fantasy to address issues of concern to the women of her day. Chief among these was a critique of a marriage system in which women could claim few legal rights. They had no right to chose their own husbands, no right to refuse the marriage bed, no right to control their own property, and no right to divorce. Girls of her class were often wed at 14 or 15, given (sometimes virtually sold) to men who were decades older; and unsatisfactory wives could be locked up at their husband's command in mental institutions or distant convents. Many of the fairy tale salonni��res were sharply critical of such practices, and promoted ideals of love, fidelity, and civilit�� between the sexes. Their tales reflected the realities they lived with, and their dreams of a better way of life. Their Animal Bridegroom stories, in particularly, embodied the real-life fears of women who could be promised to total strangers in marriage, and who did not know if they'd find a lover or a beast in their marriage bed.

While we generally think of fairy tales as anonymous stories handed down from the distant past, Beauty and the Beast, in fact, is a literary work penned by the French writer Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve in 1740. De Villeneuve was part of the "second wave" of French fairy tale writers (Madame D'Aulnoy, Charles Perrault, and other salon fairy tale writers comprising the "first wave" fifty years earlier). When she sat down to create Beauty and the Beast, she was influenced by those earlier salonni��res, as well by Apuleius' "Cupid and Psyche" (published in his Golden Ass) and by the many animal -bridegroom legends to be found in the folk tradition. Like Madame D'Aulnoy and other salonni��res before her, Villeneuve used the metaphorical language of fantasy to address issues of concern to the women of her day. Chief among these was a critique of a marriage system in which women could claim few legal rights. They had no right to chose their own husbands, no right to refuse the marriage bed, no right to control their own property, and no right to divorce. Girls of her class were often wed at 14 or 15, given (sometimes virtually sold) to men who were decades older; and unsatisfactory wives could be locked up at their husband's command in mental institutions or distant convents. Many of the fairy tale salonni��res were sharply critical of such practices, and promoted ideals of love, fidelity, and civilit�� between the sexes. Their tales reflected the realities they lived with, and their dreams of a better way of life. Their Animal Bridegroom stories, in particularly, embodied the real-life fears of women who could be promised to total strangers in marriage, and who did not know if they'd find a lover or a beast in their marriage bed.

(To read more about the salonni��res and their fairy tales, go here.)

De Villeneuve's Beauty and the Beast, over one hundred pages long and published for adult readers, is somewhat different than the short version of the tale we know today. As the story begins, Beauty's destiny lies in the hands of her father, who gives her over to the Beast (to save his own life) and thus seals her fate. The Beast is a truly fierce figure, not a gentle soul disguised by fur -- a creature lost to the human world that had once been his by birthright. The emphasis of this tale is on the transformation of the Beast, who must find his way back to the human sphere. He is a genuine monster, eventually reclaimed by civilit��, magic, and love -- and it is only then that Beauty can truly love him in return. In this story, this final transformation does not occur until after Beauty weds the monstrous Beast, waking up to find a prince sleeping beside her, his humanity restored.

Sixteen years later Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, a French woman working as a governess in England, shortened and rewrote Villeneuve's story, publishing her version in a magazine for well-bred young ladies. (Lax copyright laws made this legal and common.) She tailored her version for her audience, toning down its sensual imagery and implicit critique of forced marriages. She also pared away much unnecessary fat -- the twisting subplots beloved by Villeneuve -- to end up with a tale that was less adult and subversive, but also more direct and memorable. In the Leprince de Beaumont version, and subsequent retellings, the story becomes a more didactic one. The emphasis shifts from the Beast's need for transformation; this time it's the heroine who must change, learning to see beyond appearance and find the man hidden in the Beast.

With this shift, we see the story altered from one of critique and rebellion to one of moral edification -- aimed at younger and younger readers, as fairy tales slowly moved from adult salons to children's nurseries. By the 19th century, the Beast's monstrous shape is only a kind of costume that he wears. He poses no genuine domestic danger or sexual threat to Beauty in these stories, despite keeping her imprisoned; and in some retellings for young readers, even this is toned down: Beauty is free leave if she wishes, staying with the Beast due to her sense of honor and the keeping her father's promise.

Early in the 19th century, the proliferation of printing presses caused the de Beaumont version of Beauty and the Beast to be widely disseminated in chapbook and pamphlet editions, often with credit attached to neither de Beaumont nor de Villeneuve. Betsy Hearne, in her fascinating study of the tale (Beauty and the Beast, Chicago University Press, 1989), points out that in this period the story took on certain Victorian absent from previous retellings. In the 1843 version attributed to Charles Lamb, for example, as well as in many of the sumptuously-illustrated retellings that followed, the idea of fate -- a metaphysical obsession of the period -- is introduced. Beauty's actions, such as going to the Beast's castle in her father's stead, are not simply attributed to blind obedience (as in the de Villeneuve original) or honor (as in de Beaumont's retelling), but to the heroine's acceptance of the predestined fate that lies before her.

In the 20th century the story was subtly altered again. In 1909, the French playwright Fernand Nozier wrote and produced a popular adult version of Beauty and the Beast with a fashionable Oriental flavor. Nozier's rendition is humorous, yet beneath its light surface the play explores a distinctly sexual subtext, and the duality of body and spirit. In this version, all three sisters find themselves powerfully attracted to the Beast. When Beauty's kiss turns him into a man, she complains: "You should have warned me! Here I was smitten by an exceptional being, and all of a sudden my fianc�� becomes an ordinary, distinguished young man!" This is a problem that continues to plague most dramatic representations of the tale. The Beast is such a compelling character that it is frequently disappointing when he turns back into a prince.

We see this again in Jean Cocteau's otherwise superb 1946 film Beauty and the Beast, which remains the best dramatic presentation of the tale created to date. Beautifully shot in black-and-white, Cocteau and his co-director, Ren�� Cl��ment, blend the story's magical motifs with vivid elements of dometic realism. Cocteau strove for what he called "the supernatural within realism," mixing shots of the Beast's enchanted castle with chickens pecking on the ground and other glimpses of ordinary life, skillfully grounding his fairy story within the natural world we know. The film was made in France after World War II -- a time when post-war blackouts and equipment shortages were daily problems, and when the idea of filming a fairy tale struck many as shockingly trivial. But Cocteau avoids triviality through a deep understanding of his source material, and an almost fanatical attention to the details of lighting and design. In Beauty and the Beast: Diary of a Film, he wrote that he aimed for "the clean, sculptured line of poetry instead of the usual diffuse lighting and use of gauze for magical effect." The resulting film has stood the test of time, and become a classic of the art.

We see this again in Jean Cocteau's otherwise superb 1946 film Beauty and the Beast, which remains the best dramatic presentation of the tale created to date. Beautifully shot in black-and-white, Cocteau and his co-director, Ren�� Cl��ment, blend the story's magical motifs with vivid elements of dometic realism. Cocteau strove for what he called "the supernatural within realism," mixing shots of the Beast's enchanted castle with chickens pecking on the ground and other glimpses of ordinary life, skillfully grounding his fairy story within the natural world we know. The film was made in France after World War II -- a time when post-war blackouts and equipment shortages were daily problems, and when the idea of filming a fairy tale struck many as shockingly trivial. But Cocteau avoids triviality through a deep understanding of his source material, and an almost fanatical attention to the details of lighting and design. In Beauty and the Beast: Diary of a Film, he wrote that he aimed for "the clean, sculptured line of poetry instead of the usual diffuse lighting and use of gauze for magical effect." The resulting film has stood the test of time, and become a classic of the art.

Although Cocteau's fairy tale film can be watched by children, the subtext is adult, and powerfully so. Beauty's nightly refusal of the Beast, and the slow awakening of her attraction and sexuality, are contrasted with the Beast's struggles to contain his own animal nature. He comes to her door covered with the blood of the hunt, and with anguish she sends him away....

...This echoes the Scandinavian animal-bridegroom tale East of the Sun, West of the Moon, in which a young woman is sold by her father to a big white bear -- but in the Scandinavian folktale the sexuality is more explicit. The animal bridegroom comes to his young wife's bed every night, under cover of dark. Beneath her hands, she feels the shape of a smooth young man, not a huge white bear -- but she is forbidden to light a lamp or catch a glimpse of his face.

In the myth of Cupid and Psyche, Psyche weds a hideous flying serpent -- who is really Cupid, under a spell. By night, a man makes love to her -- but she, too, is forbidden to look. She breaks this taboo, and is punished by losing her now-beloved husband. A series of arduous tasks must be completed to win him back. In Beauty and the Beast there is no equivalent taboo or insistence on obedience. Beauty's task is the opposite: to look where others would not, and to perceive the man within the Beast. The Beast's own task is patience, and the reclaiming of the human within himself.

An American television film of the story, made in the 1970s and starring George C. Scott as the Beast, notably failed to make any improvement on Cocteau. Robin McKinley was so enraged by this production that she sat down and wrote her first novel, Beauty, in response to it. Like Cocteau, McKinley understood the importance of grounding magic in realism, and of using clean prose to echo the clean lines of the old folk stories. McKinley lengthens the tale into novel form without cluttering it with spurious detail. She takes a few liberties with the original material (Beauty's sisters, for instance, are sympathetic), yet she stays faithful to the spirit of the original. Her heroine, unlike most versions, is a gawky, horse-mad, intelligent young woman whose name is a gently ironic one. Beauty's time in the Beast's castle is particularly well-rendered, and her raptures over the Beast's library (containing works from the future by Browning and Kipling) were surely the inspiration behind the book-loving Belle of the Disney film.

McKinley was still a young writer when she wrote Beauty, her first published novel. Twenty years and several books later, she found herself attracted to the tale once again -- looking at it through new eyes of experience and maturity. She then wrote the novel Rose Daughter, an alternate version of Beauty and the Beast. Reading the two novels side by side is a fascinating experience, and both books are highly recommended.

McKinley was still a young writer when she wrote Beauty, her first published novel. Twenty years and several books later, she found herself attracted to the tale once again -- looking at it through new eyes of experience and maturity. She then wrote the novel Rose Daughter, an alternate version of Beauty and the Beast. Reading the two novels side by side is a fascinating experience, and both books are highly recommended.

Angela Carter is another writer compelled to explore Beauty and the Beast. Carter understood how to work with the adult themes in fairy tales better than any other modern author, and her early death from lung cancer has been a blow to the field of mythic arts. In addition to editing folklore collections, Carter wrote a series of dark, rather Gothic stories based on fairy tales, collected in The Bloody Chamber and (posthumously) in Burning Your Boats. Elements of Beauty and the Beast and other animal bridegroom motifs are vividly rendered in two of Carter's best stories: the poignant "Courtship of Mr. Lyon," and the sensuous "Tiger's Bride." In the latter, a profligate father loses his lovely daughter in a game of cards, and delivers her up to a wealthy masked man who imprisons her in a crumbling mansion. This is a subversive treatment of the theme, smooth as black velvet and sharp as a thorn. In both stories, Carter is careful to sustain the Beast's charisma to the very end.

"Rusina, Not Quite in Love," an enchanting novella by the Italian writer Gioia Timpanelli, published in Sometimes the Soul, transplants Beauty and the Beast to Sicily. An impoverished painter marries a rich, hideously ugly man in order to pay off her father's debts. . .and finds the princely soul hidden by the beastly exterior.

Tanith Lee's story "Beauty" (published in her adult fairy tale collection Red As Blood) takes Beauty and the Beast beyond fairy tale forests and into the far future. Lee retains the magical rose, the wayward father, the two sisters, and the monstrous suitor who must not be refused. But the Beast in this case is an alien being, and the climax of the story is a clever one -- the transformation centered on the heroine and her ideas about herself and her life. Lee then returned to the theme in her chilling dark tale "Beast" (Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears), mingling Beauty and the Beast with elements of Bluebeard and Mr. Fox. Francesa Lia Block's story beast (The Rose and the Beast) is a contemporary meditation on the nature of wildness. Wendy Wheeler's "Skin So Green and Fine" (Silver Birch, Blood Moon) incorporates Haitian voodoo and spirit possession into the tale of a innocent baker's daughter married to a mysterious man and taken to live on an isolated sugar plantation.

Tanith Lee's story "Beauty" (published in her adult fairy tale collection Red As Blood) takes Beauty and the Beast beyond fairy tale forests and into the far future. Lee retains the magical rose, the wayward father, the two sisters, and the monstrous suitor who must not be refused. But the Beast in this case is an alien being, and the climax of the story is a clever one -- the transformation centered on the heroine and her ideas about herself and her life. Lee then returned to the theme in her chilling dark tale "Beast" (Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears), mingling Beauty and the Beast with elements of Bluebeard and Mr. Fox. Francesa Lia Block's story beast (The Rose and the Beast) is a contemporary meditation on the nature of wildness. Wendy Wheeler's "Skin So Green and Fine" (Silver Birch, Blood Moon) incorporates Haitian voodoo and spirit possession into the tale of a innocent baker's daughter married to a mysterious man and taken to live on an isolated sugar plantation.

Jane Yolen has worked with fairy tale themes for many years in the roles of fiction writer, academic, and editor of folklore collections. Her slant-wise take on Beauty's story is "Beauty and the Beast: An Anniversary" (The Faery Flag), a poignant poem from Beauty's point of view,reflecting on her long years with the Beast and their solitary, childless lives. (You can read it online here.)

Jane Yolen has worked with fairy tale themes for many years in the roles of fiction writer, academic, and editor of folklore collections. Her slant-wise take on Beauty's story is "Beauty and the Beast: An Anniversary" (The Faery Flag), a poignant poem from Beauty's point of view,reflecting on her long years with the Beast and their solitary, childless lives. (You can read it online here.)

I also recommend Beast by Donna Jo Napoli, a rich, unusual, beautifully crafted version of the tale. Inspired by the Persian fairy tale tradition, Napoli's hero is an Islamic prince transformed by a curse into a lion. Fleeing his father's lands, he makes his way to an abandoned chateau in France -- where a merchant, a rose, and a courageous young woman bring the story to its proper conclusion.

There are countless ways one can draw on old fairy tales to inspire modern works of art and fiction, as the works discussed above clearly demonstrate, and these ways are limited only by the imaginations of the artists themselves. No single version of Beauty and the Beast can be considered "correct" or "definitive" -- for although the story by de Villeneuve and de Beaumont did not begin as an oral folk tale, it has its roots in that tradition. And it is the nature of folk tales to be fashioned anew for each new generation.

And yet, Disney's film of Beauty and the Beast still disturbs me. Perhaps because it has not been billed as a new story inspired by the old fairy tale; rather, it has been presented to us as if it were the old fairy tale, and such is the power of the Disney name that audiences around the world now perceive this as truth. Yet it's not the old tale. Too many fundamentals have been changed for the film to make that claim -- and changed in glib or simplistic ways that lessen the story's classic themes. The father has been changed into a harmless buffoon, his role in Beauty's imprisonment diminished into an accident of circumstance. Beauty's request for a rose, and her father's thoughtless way of procuring one, have been deleted altogether, along with Beauty's jealous, interfering sisters. An arrogant suitor, Gaston, has been added and presented as the villain of the piece. In short, the heroes and villains of the story are clear-cut, unambiguous -- Belle and her father are always Good, Gaston and his minions are Bad. In the old fairy tale, Beauty makes mistakes: she goes home, she forgets about the Beast, and by doing so she almost causes his death. In the Disney film, we have a perfect heroine who never grows, never undergoes a maturation of her own to echo the Beast's metamorphosis, his reclamation of his humanity. The requisite happy ending is achieved, but the price for it has not been paid -- except by the dull-witted characters unfortunate enough to be wearing the black hats.

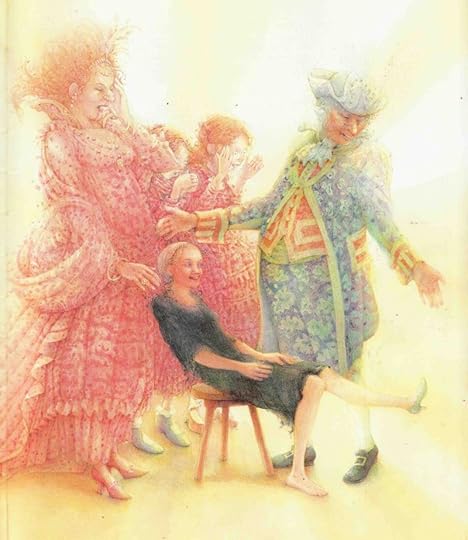

I am reminded of Jane Yolen's words in yesterday's post lamenting the fate of Cinderella, another heroine white-washed by Disney. The Cinderella of the folk tradition is clever, feisty, active girl -- while in the Disney film, as Jane points out, she's a "helpless, hapless, pitiable, useless heroine who has to be saved time and time again by talking mice and birds because she is 'off in a world of dreams'. It is a Cinderella who is not recognized by her prince until she is magically back in her ball gown, beribboned and bejeweled. Poor Cinderella. Poor us."

Likewise, with Disney's Beauty and the Beast we take one step forward with the creation of a literate and courageous heroine, but two steps backwards as the heart of the tale is lost in the musical razzle-dazzle. But hey, the film is entertaining and fun. My young friend and I enjoyed it thoroughly. So should we care about what's been lost in the process? In my opinion, you bet we should. It does no service to lie to children, to present the world as simpler than it is. Villains rarely appear with convenient black hats, good people are rarely perfect. Beauty has gone to Hollywood now. Poor Beauty. Poor Beast. Poor us.

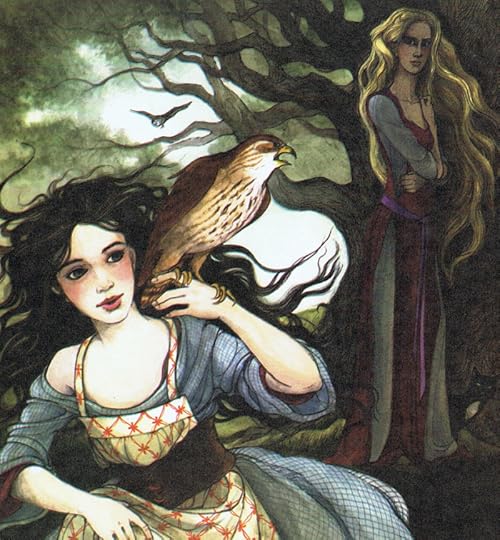

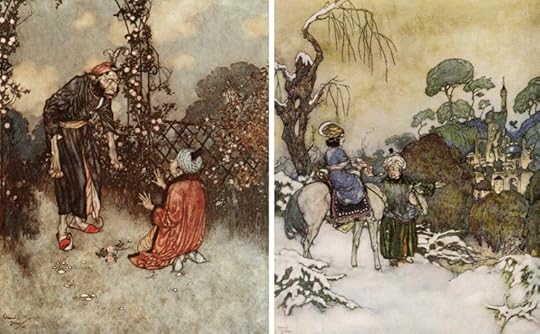

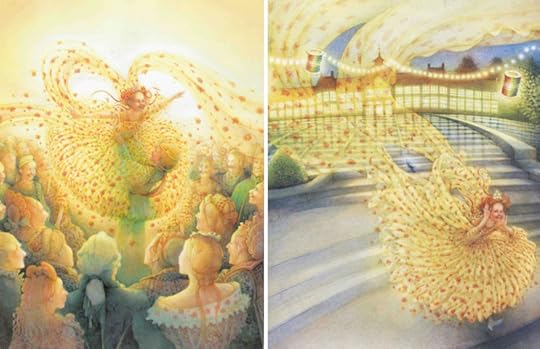

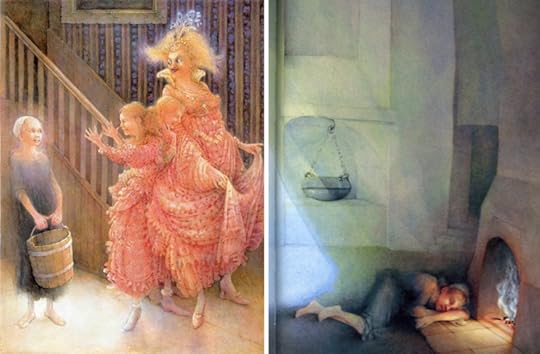

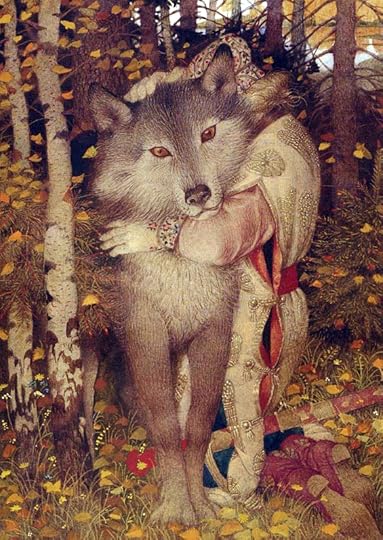

Art: The Beauty & the Beast illustrations above are by Kinuko Y. Craft, Adrienne Segur, Walter Crane, H.J. Ford, Warwick Goble, Edmund Dulac, Scott Gustafson, Angela Barrett, Pavel Tartarnikov, Jan Brett, Gabriel Pacheco, Eleanor Vere Boyle, and Mercer Mayer. Each image is identified in the picture captions. (Hold your cursor over the pictures to see them.) Photographs: Film stills from Beauty & the Beast directed by Jean Cocteau & Ren�� Cl��ment, starring Jean Marais and Josette Day (1946), andfrom Beauty and the Beast directed by Fiedler Cook, starring George C. Scott & Trish Van Devere (1976). All rights to the art and text in this post reserved by the artists and author.

July 9, 2019

Retellng Cinderella

In her seminal collection Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Chilhood, Jane Yolen discusses the "changeling life" of fairy tales as they travel from teller to teller, country to country, and century to century. Here she reflects on Cinderella in her various guises:

"The story of Cinderella has endured for over a thousand years, first surfacing in a literary source in 9th-century China. It has since been found from the Orient to the interior of South America, and over five hundred variants have been located by folklorists in Europe alone. This best-loved tale has been brought to life over and over so many times, no one can say for sure where the oral tale truly began. But as Joseph Jacobs, the indefatigable Victorian collector, once said of a Cinderella story he printed, it was 'an English version of an Italian adaptation of a Spanish translation of a Latin version of a Hebrew translation of an Arabic translation of an Indian original.' That is certainly an accurate statement of the hazards of folk-tale attributing: each reteller has brought to a tale something of his or her cultural orientation. The Chinese admiration for the tiny 'lotus foot' is preserved in the Cinderella tale, as is the 17th century European preoccupation with dressing for the ball.

"But beyond the cultural accoutrements, the detritus of centuries, Cinderella speaks to all of us in whatever skin we inhabit: the child mistreated, a princess or highborn lady in disguise bearing her trials with patience, fortitude, and determination. Cinderella makes intelligent decisions, for she knows that wishing solves nothing without the concomitant action. We have each of us been that child. (Even boys and men share that dream, as evidenced by the many Ash-boy variants.) It is the longing of any youngster sent supperless to bed or given less than a full share at Christmas. And of course it is the adolescent dream.

"To make Cinderella less than she is, an ill-treated but passive princess awaiting rescue, cheapens our most cherished dreams and makes mockery of the magic inside us all -- the ability to change our own lives, the ability to control our own destinies.

"In the oldest of the Cinderella variants, the heroine is hardly catatonic. In the Grimm 'Cinder-Maid,' though she weeps, she continues to perform the proper rites and rituals at her mother's grave, instructing the birds who roost there in the way to help her get to the ball. In 'The Dirty Shepherdess' variant and 'Cap o' Rushes' from France, '...she dried her eyes, and made a bundle of her jewels and her best dresses and hurriedly left the castle where she was born.' Off she goes to make her own life, working first as a maid in the kitchen and sneaking off to see the master's son. Even in Perrault's 17th-century 'Cendrillon, or The Little Glass Slipper,' when the fairy godmother runs out of ideas for enchantment, and was at a loss for a coachman, 'I'll go and see,' says Cendrillon, 'if there be never a rat in the rat-trap, we'll make a coach-man of him.'

"The older Cinderella is no namby-pamby forgiving heroine. Like Chesterton's children, who believe themselves innocent and demand justice -- unlike adults who know themselves guilty and look for mercy -- Cinderella believes in justice. In 'Rushen Coatie' and 'The Cinder-Maid,' the elder sisters hack

off their toes in order to try and fit the tiny shoe, and Cinderella never stops them. Her telltale birds warn the prince:

Turn and peep, turn and peep,

There's blood within the shoe;

A bit is cut from off the heel

And a bit from off the toe.

"Does Cinderella comfort her maimed sisters? Nary a word. And, in the least bowdlerized of the German and Nordic variants, when the two sisters attend the wedding of Cinderella and the prince, 'the elder was at the right side and the younger at the left, and the pigeons pecked out one eye from each of them.' Did Cinderella stop the carnage -- or the wedding? There is never a misstep between that sentence and the next. 'Afterwards, as they came back, the elder was on the left, and the younger on the right, and then the pigeons pecked out the other eye from each. And thus, for their wickeness and falsehood, they were punished with blindess all their days.'

"Of course, all this went into the Walt Disney blender and came out emotional pap. In 1950, when the movie Cinderella burst onto the American scene, the Disney studios were going through a particularly trying time. Disney had been deserted by the intellectuals who had championed his art for some time. Because of World War II, the public had been more interested in war films than cartoons. But with the release of Cinderella, the Disney studios made a fortune, grossing $4.247 million in the first release alone. It set a new pattern for Cinderella: a helpless, hapless, pitiable, useless heroine who has to be saved time and time again by the talking mice and birds because she is 'off in a world of dreams.' It is a Cinderella who is not recognized by her prince until she is magically back in her ball gown, beribboned and bejeweled.

"Poor Cinderella. Poor us. The acculturation of millions of boys and girls to this passive Cinderella robs the old tale of its invigorating magic. The story has been falsified and the true meaning lost -- perhaps forever."

If you'd like to know more about the history of Cinderella and it's many variants, my essay on the subject is online her: Cinderella: Ashes, Blood, and the Slipper of Glass.

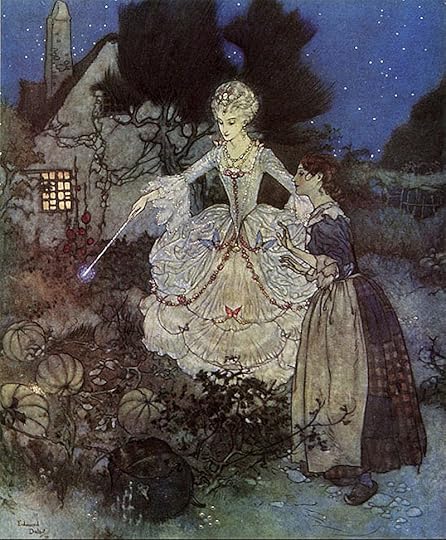

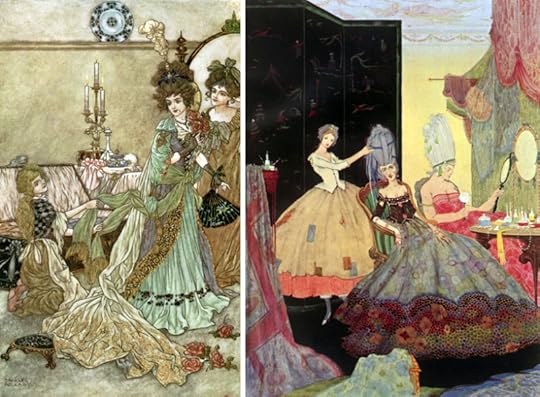

Pictures: The Cinderella art above is by Edmund Dulac, Arthur Rackham, Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Ruth Sanderson, Liiga Klavina, Jennie Harbour, Charles Folkard, Harry Clarke, Mary Blair, and Loek Hoopmans. Each image is identified in the picture captions. (Hold your cursor over the pictures to see them.) Words: The passage above from "Once Upon a Time" by Jane Yolen, published in Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Childhood (Philomel, 2981; August House, 2000), which I highly recommend. All rights to the text above are reserved by the author and artists.

The changeling story of Cinderella

In her seminal collection Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Chilhood, Jane Yolen discusses the "changeling life" of fairy tales as they travel from teller to teller, country to country, and century to century. Here she reflects on Cinderella in her various guises:

"The story of Cinderella has endured for over a thousand years, first surfacing in a literary source in 9th-century China. It has since been found from the Orient to the interior of South America, and over five hundred variants have been located by folklorists in Europe alone. This best-loved tale has been brought to life over and over so many times, no one can say for sure where the oral tale truly began. But as Joseph Jacobs, the indefatigable Victorian collector, once said of a Cinderella story he printed, it was 'an English version of an Italian adaptation of a Spanish translation of a Latin version of a Hebrew translation of an Arabic translation of an Indian original.' That is certainly an accurate statement of the hazards of folk-tale attributing: each reteller has brought to a tale something of his or her cultural orientation. The Chinese admiration for the tiny 'lotus foot' is preserved in the Cinderella tale, as is the 17th century European preoccupation with dressing for the ball.

"But beyond the cultural accoutrements, the detritus of centuries, Cinderella speaks to all of us in whatever skin we inhabit: the child mistreated, a princess or highborn lady in disguise bearing her trials with patience, fortitude, and determination. Cinderella makes intelligent decisions, for she knows that wishing solves nothing without the concomitant action. We have each of us been that child. (Even boys and men share that dream, as evidenced by the many Ash-boy variants.) It is the longing of any youngster sent supperless to bed or given less than a full share at Christmas. And of course it is the adolescent dream.

"To make Cinderella less than she is, an ill-treated but passive princess awaiting rescue, cheapens our most cherished dreams and makes mockery of the magic inside us all -- the ability to change our own lives, the ability to control our own destinies.

"In the oldest of the Cinderella variants, the heroine is hardly catatonic. In the Grimm 'Cinder-Maid,' though she weeps, she continues to perform the proper rites and rituals at her mother's grave, instructing the birds who roost there in the way to help her get to the ball. In 'The Dirty Shepherdess' variant and 'Cap o' Rushes' from France, '...she dried her eyes, and made a bundle of her jewels and her best dresses and hurriedly left the castle where she was born.' Off she goes to make her own life, working first as a maid in the kitchen and sneaking off to see the master's son. Even in Perrault's 17th-century 'Cendrillon, or The Little Glass Slipper,' when the fairy godmother runs out of ideas for enchantment, and was at a loss for a coachman, 'I'll go and see,' says Cendrillon, 'if there be never a rat in the rat-trap, we'll make a coach-man of him.'

"The older Cinderella is no namby-pamby forgiving heroine. Like Chesterton's children, who believe themselves innocent and demand justice -- unlike adults who know themselves guilty and look for mercy -- Cinderella believes in justice. In 'Rushen Coatie' and 'The Cinder-Maid,' the elder sisters hack

off their toes in order to try and fit the tiny shoe, and Cinderella never stops them. Her telltale birds warn the prince:

Turn and peep, turn and peep,

There's blood within the shoe;

A bit is cut from off the heel

And a bit from off the toe.

"Does Cinderella comfort her maimed sisters? Nary a word. And, in the least bowdlerized of the German and Nordic variants, when the two sisters attend the wedding of Cinderella and the prince, 'the elder was at the right side and the younger at the left, and the pigeons pecked out one eye from each of them.' Did Cinderella stop the carnage -- or the wedding? There is never a misstep between that sentence and the next. 'Afterwards, as they came back, the elder was on the left, and the younger on the right, and then the pigeons pecked out the other eye from each. And thus, for their wickeness and falsehood, they were punished with blindess all their days.'

"Of course, all this went into the Walt Disney blender and came out emotional pap. In 1950, when the movie Cinderella burst onto the American scene, the Disney studios were going through a particularly trying time. Disney had been deserted by the intellectuals who had championed his art for some time. Because of World War II, the public had been more interested in war films than cartoons. But with the release of Cinderella, the Disney studios made a fortune, grossing $4.247 million in the first release alone. It set a new pattern for Cinderella: a helpless, hapless, pitiable, useless heroine who has to be saved time and time again by the talking mice and birds because she is 'off in a world of dreams.' It is a Cinderella who is not recognized by her prince until she is magically back in her ball gown, beribboned and bejeweled.

"Poor Cinderella. Poor us. The acculturation of millions of boys and girls to this passive Cinderella robs the old tale of its invigorating magic. The story has been falsified and the true meaning lost -- perhaps forever."

If you'd like to know more about the history of Cinderella and it's many variants, my essay on the subject is online her: Cinderella: Ashes, Blood, and the Slipper of Glass.

Pictures: The Cinderella art above is by Edmund Dulac, Arthur Rackham, Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Ruth Sanderson, Liiga Klavina, Jennie Harbour, Charles Folkard, Harry Clarke, Mary Blair, and Loek Hoopmans. Each image is identified in the picture captions. (Hold your cursor over the pictures to see them.) Words: The passage above from "Once Upon a Time" by Jane Yolen, published in Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Childhood (Philomel, 2981; August House, 2000), which I highly recommend. All rights to the text above are reserved by the author and artists.

Cinderella

In her seminal collection Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Chilhood, Jane Yolen focuses on the "changeling life" of fairy tales as they travel from teller to teller, country to country, and century to century. Here she reflects on Cinderella in her various guises:

"The story of Cinderella has endured for over a thousand years, first surfacing in a literary source in 9th-century China. It has since been found from the Orient to the interior of South America, and over five hundred variants have been located by folklorists in Europe alone. This best-loved tale has been brought to life over and over so many times, no one can say for sure where the oral tale truly began. But as Joseph Jacobs, the indefatigable Victorian collector, once said of a Cinderella story he printed, it was 'an English version of an Italian adaptation of a Spanish translation of a Latin version of a Hebrew translation of an Arabic translation of an Indian original.' That is certainly an accurate statement of the hazards of folk-tale attributing: each reteller has brought to a tale something of his or her cultural orientation. The Chinese admiration for the tiny 'lotus foot' is preserved in the Cinderella tale, as is the 17th century European preoccupation with dressing for the ball.

"The story of Cinderella has endured for over a thousand years, first surfacing in a literary source in 9th-century China. It has since been found from the Orient to the interior of South America, and over five hundred variants have been located by folklorists in Europe alone. This best-loved tale has been brought to life over and over so many times, no one can say for sure where the oral tale truly began. But as Joseph Jacobs, the indefatigable Victorian collector, once said of a Cinderella story he printed, it was 'an English version of an Italian adaptation of a Spanish translation of a Latin version of a Hebrew translation of an Arabic translation of an Indian original.' That is certainly an accurate statement of the hazards of folk-tale attributing: each reteller has brought to a tale something of his or her cultural orientation. The Chinese admiration for the tiny 'lotus foot' is preserved in the Cinderella tale, as is the 17th century European preoccupation with dressing for the ball.

"But beyond the cultural accoutrements, the detritus of centuries, Cinderella speaks to all of us in whatever skin we inhabit: the child mistreated, a princess of highborn lady in disguise bearing her trials with patience, fortitude, and determination. Cinderella makes intelligent decisions, for she knows that wishing solves nothing without the concomitant action. We have each of us been that child. (Even boys and men share that dream, as evidenced by the many Ash-boy variants.) It is the longing of any youngster sent supperless to bed or given less than a full share at Christmas. And of course it is the adolescent dream.

"To make Cinderella less than she is, an ill-treated but passive princess awaiting rescue, cheapens our most cherished dreams and makes mockery of the magic inside us all -- the ability to change our own lives, the ability to control our own destinies.

"In the oldest of the Cinderella variants, the heroine is hardly catatonic. In the Grimm 'Cinder-Maid,' though she weeps, she continues to perform the proper rites and rituals at her mother's grave, instructing the birds who roost there in the way to help her get to the ball. In 'The Dirty Shepherdess' variant and 'Cap o' Rushes' from France, '...she dried her eyes, and made a bundle of her jewels and her best dresses and hurriedly left the castle where she was born.' Off she goes to make her own life, working first as a maid in the kitchen and sneaking off to see the master's son. Even in Perrault's 17th-century 'Cendrillon, or The Little Glass Slipper,' when the fairy godmother runs out of ideas for enchantment, and was at a loss for a coachman, 'I'll go and see,' says Cendrillon, 'if there be never a rat in the rat-trap, we'll make a coach-man of him.'

"The older Cinderella is no namby-pamby forgiving heroine. Like Chesterton's children, who believe themselves innocent and demand justice -- unlike adults who know themselves guilty and look for mercy -- Cinderella believes in justice. In 'Rushen Coatie' and 'The Cinder-Maid,' the elder sisters hack  off their toes in order to try and fit the tiny shoe, and Cinderella never stops them. Her telltale birds warn the prince:

off their toes in order to try and fit the tiny shoe, and Cinderella never stops them. Her telltale birds warn the prince:

Turn and peep, turn and peep,

There's blood within the shoe;

A bit is cut from off the heel

And a bit from off the toe.

"Does Cinderella comfort her maimed sisters? Nary a word. And, in the least bowdlerized of the German and Nordic variants, when the two sisters attend the wedding of Cinderella and the prince, 'the elder was at the right side and the younger at the left, and the pigeons pecked out one eye from each of them.' Did Cinderella stop the carnage -- or the wedding? There is never a misstep between that sentence and the next. 'Afterwards, as they came back, the elder was on the left, and the younger on the right, and then the pigeons pecked out the other eye from each. And thus, for their wickeness and falsehood, they were punished with blindess all their days.'

"Of course, all this went into the Walt Disney blender and came out emotional pap. In 1950, when the movie Cinderella burst onto the American scene, the Disney studios were going through a particularly trying time. Disney had been deserted by the intellectuals who had championed his art for some time. Because of World War II, the public had been more interested in war films than cartoons. But with the release of Cinderella, the Disney studios made a fortune, grossing $4.247 million in the first release alone. It set a new pattern for Cinderella: a helpless, hapless, pitiable, useless heroine who has to be saved time and time again by the talking mice and birds because she is 'off in a world of dreams.' It is a Cinderella who is not recognized by her prince until she is magically back in her ball gown, beribboned and bejeweled.

"Poor Cinderella. Poor us. The acculturation of millions of boys and girls to this passive Cinderella robs the old tale of its invigorating magic. The story has been falsified and the true meaning lost -- perhaps forever."

Pictures: The Cinderella art above is by Edmund Dulac, Arthur Rackham, Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Ruth Sanderson, Liiga Klavina, Jennie Harbour, Charles Folkard, Harry Clarke, Mary Blair, and Loek Hoopmans. Each image is identified in the picture captions. (Hold your cursor over the pictures to see them.) Words: The passage above from "Once Upon a Time" by Jane Yolen, published in Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Childhood (Philomel, 2981; August House, 2000), which I highly recommend. All rights to the text above are reserved by the author and artists.

To read more about the history of the fairy tale: "Cinderella: Ashes, Blood, and the Slipper of Glass."

Stories lean on stories

From Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Children by Jane Yolen:

"Over the last few years there have been many educational councils and conferences, papers and presentations about the need to return to the Basics -- to the teaching of the fundamental skills of reading, writing and arithmetic. But they are not the only subjects that are vital to our intellectual and human growth. An understanding of, a grounding in, a familiarity with the old lores and wisdoms of the so-called dead worlds is also a basic developmental need. Folklorist Charles Potter has written, 'Folklore is a lively fossil that refuses to die.' If children are invited to greet the great stories, to shake hands with the lively fossil, they will soon discover -- as did their parents before them -- that the well-kept bones are indispensable to the life of the mind....

"One of the basic functions of myth and folk literature is to provide a landscape of allusion. With the first story a child hears, he or she takes a step toward perceiving an new environment, one that is filled with quests and questers, fated heroes and fetid monsters, intrepid heroines and trepid helpers, even incompetent oafs who achieve competence and wholeness by going out and trying. As the child hears more stories and tales that are linked in both obvious and subtle ways, the landscape is broadened and deepened, and becomes more fully populated with memorable characters. These are the same folk that the child will meet again and again, threading their archetypal ways through the cultural history of our planet.

"Stories lean on stories, art on art. This familiarity with the treasure-house of ancient story is necessary for any true appreciation of today's literature. A child who has never met Merlin -- how can he or she really recognize the wizards in Earthsea? The child who has never heard of Arthur -- how can he or she totally appreciate Susan Cooper's The Grey King? The child who has never known dryads or fauns will not recognize them in Narnia, or find their faces on museum walls or in the black silhouettes on Greek vases. Never to have trod the stony paths of Mount Pelion with Chiron and to have seen only the sexually precocious centaurs of Fantasia or the horsemen on TV's Hercules is to be diminished, narrowed, condemned to live in a cultural landscape that is dry as dust."

"[Folklore also provides] a way of looking at another culture from the inside out. If a child becomes familiar with the pantheon of Greek gods, who toy with human lives as carelessly as children at play, then the Greek world view begins to come into focus. If a child learns about the range of Norse godlings who wait for heroic companions to feast with them at Valhalla, then the Vikings' emphasis on battle derring-do makes more sense. The study of the myth-making process, of those things that come together in a culture and propel a folk towards a coherent mythology, may be a very sophisticated one indeed, but its beginnings are back in the tales themselves.

"Stories lean on stories, cultures on cultures. Just as any great city is built on the stones and bones of its ancestors, so too is any mythology. And if our children can look at their own modern folklore within a broader context, they will see some very surprising shadows indeed. Spider-Man and TV's Hercules, Buffy and Xena do not spring from a void but from needs within our own culture. And those needs lean on past needs. Maureen Duffy writes in The Erotic World of Faery: 'We remake our mythology in every age out of our own needs. We may use ideas lying around loose from a previous system or systems as part of the fabric. The human situation doesn't radically alter and therefore certain myths are constantly reappearing.' "

"And if we deny our children their cultural, historical heritage, their birthright to these stories, what then? Instead of creating men and women who have a grasp of literary allusion and symbolic language, and a metaphorical tool for dealing with the serious problems of life, we will be forming stunted boys and girls who speak only a barren language, a language that accurately reflects their equally barren minds. Language helps develop life as surely as it reflects life. It is a most import part of our human condition.

"Our children today face a serious deprivation -- the loss of the word, of words. For as stories depend on stories, lives depend on lives. Contact and continuity are essential links in the long chain of human culture....

"A child conversant with the old tales accepts them with an ease born of familiarity, fitting them into his own scheme of things, endowing them with new meaning. That old fossil, those old bones, walk again, and sing and dance and speak with a new tongue. The old stories bridge the centuries."

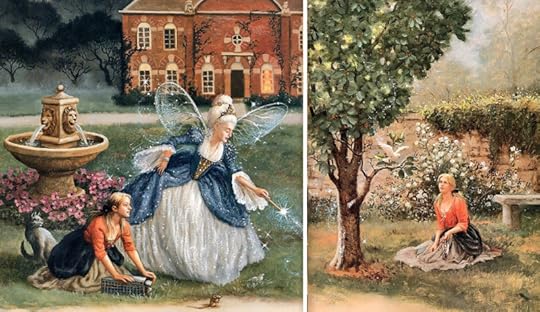

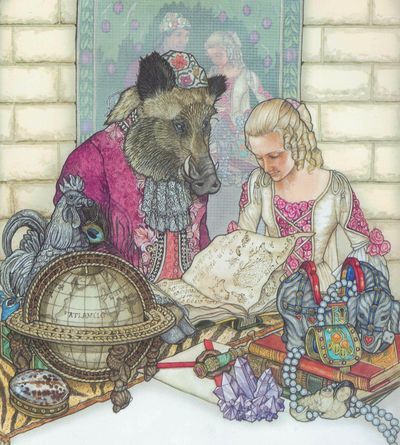

The imagery today is by Ruth Sanderson, a book artist and author based in western Massachusetts. Ruth grew up in a small town where her grandmother was a librarian, and much of her youth was spent in the woods, on the back of a horse, or with her nose in a book. She studied at Paier College of Art in Connecticut, then embarked on an illustration career focused on children's books in the mid-1970s. She has published over 80 books since then, including Cinderella, The Sleeping Beauty, The Twelve Dancing Princesses, Snow White & Rose Red, Goldilocks, The Enchanted Wood, The  Crystal Mountain, The Snow Princess, and Papa Gatto, all much beloved by young (and old) readers. She is a member of the Society of Illustrators, the Society of Children's Book Writers & Illustrators, and the Western Massachusetts Illustrator's Guild, as well as co-founder of the Children's Book Illustration program at Hollins University.

Crystal Mountain, The Snow Princess, and Papa Gatto, all much beloved by young (and old) readers. She is a member of the Society of Illustrators, the Society of Children's Book Writers & Illustrators, and the Western Massachusetts Illustrator's Guild, as well as co-founder of the Children's Book Illustration program at Hollins University.

"The archetypal characters and the symbolism that one finds in fairy tales," she says, "contain truths that are universal and can be as meaningful for children today as they have been for centuries past. So many of them are 'rites of passage stories,' where the hero (child) leaves home to seek adventure or to go on an impossible quest, learning in the process how to become independent and to form new relationships outside of parental influence. In The Twelve Dancing Princesses, the three magical woods that the princesses pass through are symbolic to me of their rite of passage into adulthood.

"My original story The Enchanted Wood grew out of my love for the woods, for paths, for fairytales. Trees have always had the ability to hold me spellbound, at sunset especially. An old tree can have such character and majesty. In the story, three sons go on a quest for the Heart of the World (which is a magical ���tree of life���) The fact that success often comes at a great sacrifice is the central theme of this story.

"Papa Gatto is the result of combining a number of Italian fairytales with a similar element -- a talking cat. It is a Cinderella-type story with a bit of Puss in Boots as well. And a slightly modern twist at the end, when the young lady declines the Prince���s proposal in favor of living with her beloved cats!"

Please visit Ruth's Golden Wood Studio to learn more about her work.

The passages quoted above are from "How Basic is Shazam?" by Jane Yolen, published in Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Childhood (Philomel, 2981; August House, 2000). All rights to the text and art in the post reserved by the author and artist.

July 8, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

It's early morning, quiet and misty, the sun rising slowly above the moor, and I've been playing the music of guitar virtuoso Ben Walker and friends to greet the day...

Above: "Silverline," written and sung by Josienne Clarke, backed up by Walker on guitar. The song appears on the duo's third album, Nothing Can Bring Back the Sun (2014).

Below: "John Riley," a traditional ballad performed by Clarke & Walker on their first album, The Seas Are Deep (2011).

Above: "When a Knight Won His Spurs," an early 20th century children's hymn adapted to a folk melody by Ralph Vaughan Williams. The song appeared on Clarke & Walker's second album, Fire & Fortune (2013).

Below: "Nurses' Song" by Ben Walker (with singer Kitty Macfarlane), from his gorgeous new solo album, Echo (2019). The piece is based on two poems from Songs of Innocence and Experience by William Blake.

Above: "How Stands the Glass Around" by Walker (with singer Jinnwoo). This one is a new arrangement of an 18th century soldiers' drinking song.

Below: "Let Me in at the Door" by Walker (with singer Hazel Askew) -- based on a 19th century poem, "The Witch," by Mary Elizabeth Coleridge.

Above: "Lachrimaie Pavane," the lute music of John Dowland, played on a Gibson ES-175.

Below: Walker & Clarke perform "The Banks of the Sweet Primrose" at the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards.

July 5, 2019

Running with wolves

Of all wild stories, the ones involving wolves seem somehow the wildest, for the wolf is an animal who carries our love and fear of wilderness in equal measure. A wide range of wolf mythology can be found around the world wherever wolves have roamed: in some tales they are depicted as culture heroes and loyal companions to the gods; in others they are devilish, destructive figures, enemies of the gods and humankind alike, agents of primal chaos.

The tradition of the wolf as warrior-hero is older than recorded history, writes Barry Lopez in his magnificent book Of Wolves and Men:

"The legend of Romulus and Remus and other wolf children point up another ancient image, that of the benevolent wolf-mother. The deaths of those taken for werewolves and burned alive in the Middle Ages represent yet another, focusing negative feelings about the wolf.

"I have written about the wolf as a symbol of twilight; other writers have suggested, and I agree with them, that the wolf is a symbol reflecting two human alternatives at war: instinctual urges and rational behavior. In Hesitant Wolf and Scrupulous Fox, Karen Kennerly says the wolf is the creature who is most like us in fable. 'Out of phase with himself,' she says, 'he is defeated alternately by hubris and naivete. He becomes the irreconcilability between instinct and rational thought.' His attempts to live a rational life is defeated by his urge to behave basely. Thus, the human and bestial natures. The central conflict between man's good and evil natures is revealed in his twin images of the wolf as a ravening killer and as nurturing mother. The former was the werewolf; the latter the mother to children, like Romulus and Remus, who found nations."

The wolves of myth, of course, are human creations, and have little to do with the actual lives of wolves living in the wild -- a subject that has been studied extensively by scientists of many different stripes in modern times, and about which there is much we still don't know, or fully understand. Wolf packs are complex, sophisticated systems -- and it seems that every time wolf scholars assert theories about precisely how they work, new data arises to shatter those theories. In a world where we like to map and track and pin knowledge down into cold, hard facts, the wolves elude us, slipping back into dark, starless night of mystery.

This makes them irresistible creatures for writers of "wild stories," and the howling of wolves can be found in many good (and not-so-good) works of fantasy fiction.

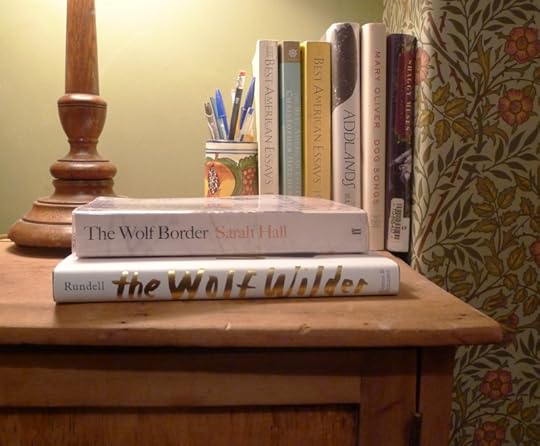

One of my favorite wolf stories is The Wolf Wilder by Katherine Rundell. It's an absolutely splendid novel, which I'll let the author describe herself:

"The Wolf Wilder is a fairy tale of sorts; in it, two children ride wolves across Russia in the snow. Much of fiction writing involves finding new ways to talk about old desires, and mine is a litany of all the things I dreamt of as a child: snow, knife, skis, wolf, boy. My source-text was the glorious Russian fairy tale, The Tale of Ivan Tsarevich, the Firebird and the Grey Wolf. In it Ivan Tsarevich, the son of a Tsar, is sent to catch a firebird that is eating his father's apples. He comes to a crossroads where a choice is set out: 'Whoever goes to the right shall die. Whoever goes along the

middle way will have his horse devoured by the grey wolf.' Ivan takes the middle road and, in the blunt diction of fairy tales, the grey wolf does indeed eat his horse, then suggests that Ivan ride on his own back to glory, instead.

"What I remember most clearly is one line. 'The grey wolf said, 'Get on my back and hang on tightly': and the wolf carried him off 'just as if he were on a swan's back.' That line reverberates with desire, both childlike and adult. It captures the doubleness of innocence and experience in fairy tales -- as Carol Ann Duffy writes in her poem 'Little Red Cap': What little girl doesn't dearly love a wolf?

"Shape-shifting wolves have always had cultural bite. The very first transformation scene in Ovid is also one of the earliest fictional accounts of lycanthropy, and was always the story in the Metamorphoses that I, as an unpleasant child, loved most. King Lycaon murders a hostage sent from Epirus, cooks his limbs 'still warm with life, boiling some and roasting others over the fire,' and serves it to Zeus as a feast that doubles as a taunt. In vengeance, Zeus strikes his palace with lightning and sends Lycaon out into the wild. 'There he uttered howling noises, and his attempts to speak were in vain. His clothes changed into bristling hairs, his arms to legs, and he became a wolf. His own savage nature showed in his rabid jaws.' Transformation, in Ovid, is a kind of truth-telling.

"Wolves offer a straightforward kind of truth, too. In Charles Perrault's 1697 version of Little Red Riding Hood; girls who get into bed with strange men don't survive. The wolf, for Perrault, is an entirely unsubtle stand-in for human lust. Angela Carter took Perrault's stories and inverted them; the result was The Bloody Chamber. Carter's world transforms the tradition of captured, passive girls; instead, it is delicious and dangerous: all dirt and diamonds, dust on mirrors, girls with architectural cheekbones and red cloaks. The young women in her tales are their own fairy godmothers. Her Red Riding Hood, faced with a wolf in the bed, 'burst out laughing; she knew she was nobody's meat.' Elsewhere, Carter wrote: "I really do believe that a fiction absolutely self-conscious of itself as a different form of human experience than reality (that is, not a logbook of events) can help to transform reality itself. 'Fairy tales remind us that we are so very hungry; the human appetite for other humans is insatiable, and Carter embraces hunger. A little bit of something wild does you good.' "

(I recommend reading Rundell's article, "The Greatest Literary Wolves," in full.)

My other favorite wolf story of recent years is Sarah Hall's finely-crafted novel The Wolf Border, about the re-introduction of wolves on a vast estate on the border of Cumbria and Scotland. This is a contemporary, largely Realist story with one slight fantasy element: in Hall's fictional world, the Scottish Referendum of 2014 has ended with Scottish independence. I admit that it took me a while to warm to the novel's protogonist, zoologist Rachael Caine, a damaged and damaging character -- but that, it turns out, is the point of the book. Rachael's emotional journey, paired with the saga of her wolves, is beautifully rendered, and I loved this book without reservation by the last page and journey's end.

Unlike the wolves of fantasy, Hall's wolves are never more or less than animals, fulfilling naturalist Henry Beston's vision that "the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours, they move finished and complete, gifted with the extension of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings: they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth."

This is not to disparage the wolves of fantasy literature, whose stories satisfy in a wholly different way: they are metaphorical tales exploring our relationship with the wild (for good or ill), and they work on us the way myths and fairy tales work on us: indirectly, symbolically, poetically, and below the level of conscious thought.

"Fantasy," explains Ursula Le Guin, "is a different approach to reality, an alternative technique for apprehending and coping with existence. It is not antirational, but pararational; not realistic but surrealistic, a heightening of reality. In Freud's terminology, it employs primary, not secondary process thinking. It employs archetypes, which, as Jung warned us, are dangerous things. Fantasy is nearer to poetry, to mysticism, and to insanity than naturalistic fiction is. It is a wilderness, and those who go there should not feel too safe....It is a journey into the subconscious mind, just as psychoanalysis is. Like pyschoanalysis, it can be dangerous; and it will change you."

The best wolves in fantasy are the ones that haunt your dreams when the book is done: Nighteyes in the Farseer books of Robin Hobb; the feral wizard-wolf at the heart of The Book of Atrix Wolfe by Patricia A. McKillp; the motorcycle-riding shapeshifters in The Evil Wizard Smallbone by Delia Sherman; the wild wolf-raised heroine of The Firekeeper Saga by Jane Lindskold; the mysterious Stephen, raised by wolves, in Alice Hoffman's darkly romantic Second Nature; the deliciously sinister Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken; or the frightening yet alluring beasts in Angela Carter's "The Company of Wolves" (and the movie made from it).

A list of good "wolf fantasy" would also surely have to include: Julie of the Wolves by Jean Craighead George (winner of the Newbery Medal); Wolf by Gillian Cross (winner of the Carnegie Medal, based on Little Red Riding Hood); Children of the Wolf by Jane Yolen (based on a real-life "feral children" tale), A Companion to Wolves by Sarah Monette & Elizabeth Bear; Cry Wolf by Pat toricia Briggs; and The Sight by David Clement-Davies (told from a wolf pack's point of view).