Terri Windling's Blog, page 55

July 26, 2019

Brothers & Beasts: the boys who love fairy tales

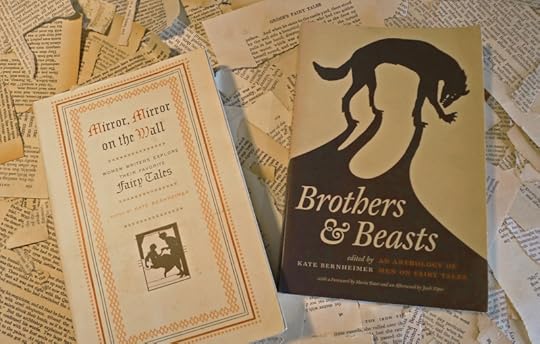

Many of you will be familiar with Kate Bernheimer's fine book Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Women Writers Explore Their Favorite Fairy Tales, originally published in 1998, containing memorable essays by Margaret Atwood, A.S. Byatt, bell hooks, Joyce Carol Oates, Fay Weldon, Joy Williams, and many others. (Ursula Le Guin, Midori Snyder, and I contributed essays to the second, expanded edition in 2002: "The Wilderness Within," "The Monkey Girl" and "Transformations.")

Less well known than Mirror, Mirror, but equally good, is Kate's follow-up volume: Brother's & Beasts: An Anthology of Men on Fairy Tales, 2007. The book has a fine roster of writers, including Gregory Maquire, Neil Gaiman, Robert Coover, Timothy Schaffaert, Christopher Barzak, Jeff VanderMeer, and Alexander Chee, plus contributions from scholars Maria Tatar and Jack Zipes, and a fascinating introduction by Kate discussing the way the project came together.

Less well known than Mirror, Mirror, but equally good, is Kate's follow-up volume: Brother's & Beasts: An Anthology of Men on Fairy Tales, 2007. The book has a fine roster of writers, including Gregory Maquire, Neil Gaiman, Robert Coover, Timothy Schaffaert, Christopher Barzak, Jeff VanderMeer, and Alexander Chee, plus contributions from scholars Maria Tatar and Jack Zipes, and a fascinating introduction by Kate discussing the way the project came together.

She'd originally intended to publish both men and women in Mirror, Mirror, she writes, but "several people who greatly supported that book did not support the inclusion of men. They claimed, quite adamantly, 'No one will be interested in what men have to say about fairy tales.' Worse still, they continued, 'Men wouldn't have much of interest to say about fairy tales.'

"But evidence of men's interest in fairy tales is vast and spans many centuries," Kate continues. "At the time I was very young and did not argue. Besides, I thought that a book gathering essays by women would be interesting too. Why not? But I always considered that book incomplete -- or, more precisely, because I am an emotional editor, I consider it unfair. Of all the literary traditions, the fairy-tale tradition is generous and spiteful towards boys and girls, men and women -- it does not prefer one over the other. I did not like to suggest that women more than men had a stake in these powerful stories.

"Also, I felt that the assertion that men would have nothing to say about fairy tales was reflective of a two-fold prejudice: against men and against fairy tales. There was an implicit disdain for boys drawn to stories of wonder. There was also an implied disdain for fairy tales, so strongly associated with girls and the nursery.

"Though several eloquent gender studies of fairy tales exist, one hardly encounters a popular reference to men and fairy tales -- Robert Bly's Iron John nothwithstanding. It is as if men are not allowed to have an emotional or artistic relationship to fairy tales. On the whole -- in the classroom, at conderences, or at lectures -- I find that men are not accustomed to being asked if they like fairy tales, let alone whether fairy tales have influences their emotional, intellectual, and artistic lives. "

The premise of Brothers & Beasts, Kate says, "was to reverse that poor spell."

"While I appreciate the celebration, both in scholarship and in popular culture, of the strong female characters in fairy tales," Kate adds, "I think that, first and foremost, our devotion to fairy tales is with 'the whole of the mind' and not with our gender. Phrased differently, perhaps less controversially, it is clear that in both Mirror, Mirror and Brothers & Beasts artistic fervor comes first -- a fervor begun in childhood with a fervor for reading....

"For me, there was nothing like reading fairy tales as a child. As Maria Tatar points out in her lovely forward, 'When you read a book as a child, it sends chills up your spine and produces somatic effects that rarely accompany the reading experience of adults.' Jack Zipes, in his afterword, writes, 'The fairy tale has not been partial to one sex or the other.' Reading fairy tales -- or writing about them -- is, I can assure you, one of the few ways that adults can re-create that delicious, somatic childhood chill.

"Yet men, so discouraged from speaking personally about fairy tales and their connection to them, may lose that opportunity -- which is a loss for us all. That is why I so badly wanted to do this book. I was surprised by the urgency the writers felt too. And I cherish the tenderness with which these writers talk about thimbles and flowers, myth makers and cowards, bears both little and big. It is the tenderness that strikes me, the tenderness and urgency here."

Brothers & Beasts is available from Wayne State University Press. I highly recommend it if it's not on your fairy tale shelves already.

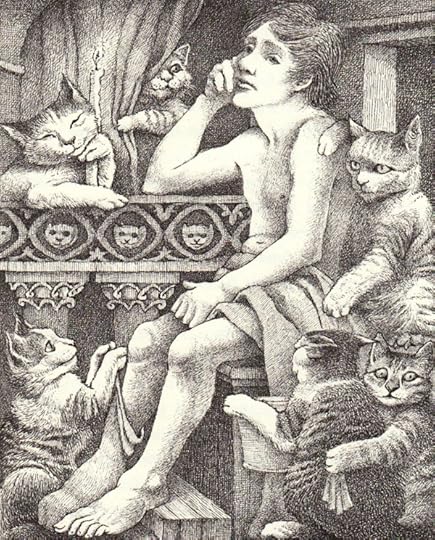

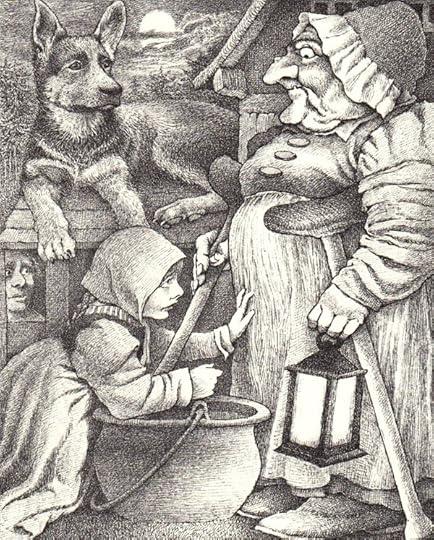

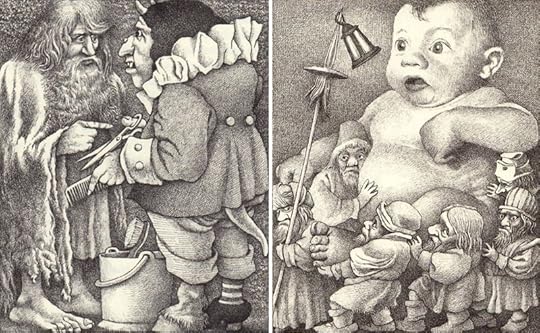

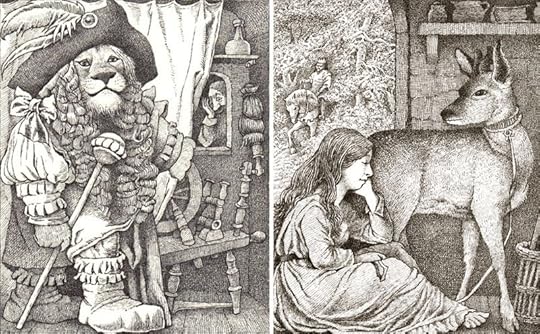

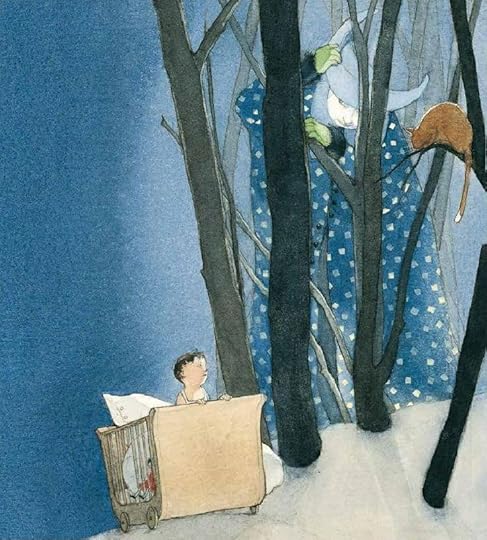

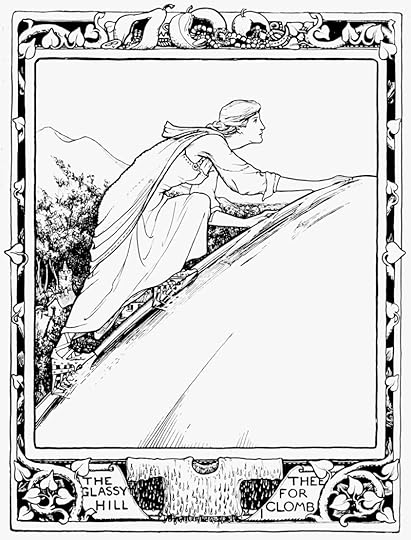

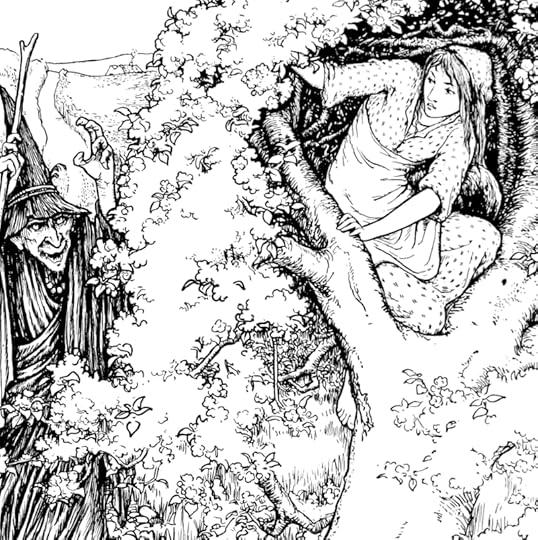

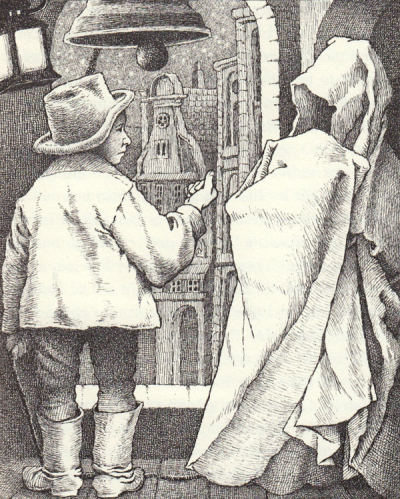

The art today is by Maurice Sendak (1928-2012), from his two-volume fairy tale masterpiece The Juniper Tree and Other Tales from Grimm. Sendak, the child of Polish-American parents, came from a family much decimated by the Holocaust. Raised in Brooklyn, New York, he vowed to become an artist after watching Disney's Fantasia at the age of twelve. He began illustrating books in the late 1940s, then moved on to writing them as well, creating such classics as Where the Wild Things Are, In the Night Kitchen, and Outside Over There, and winning virtually every major award he could win.

"Once a little boy sent me a charming card with a little drawing on it," Sendak recalled in one interview. "I loved it. I answer all my children���s letters -- sometimes very hastily -- but this one I lingered over. I sent him a card and I drew a picture of a Wild Thing on it. I wrote, 'Dear Jim: I loved your card.' Then I got a letter back from his mother and she said, 'Jim loved your card so much he ate it.' That to me was one of the highest compliments I���ve ever received. He didn���t care that it was an original Maurice Sendak drawing or anything. He saw it, he loved it, he ate it."

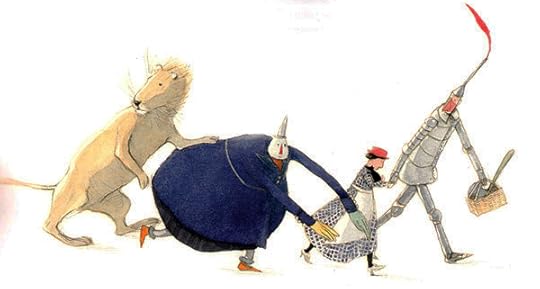

Words: The passage above is from Brothers & Beasts, edited by Kate Bernheimer (Wayne State University Press, 2007); all rights reserved by the author. Pictures: Maurice Sendak's drawings are from The Juniper Tree and Other Tales from Grimm, translated by Lore Segal & Randall Jarrell (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, revised edition 2003); titles can be found in the picture captions. All rights reserved by the Sendak estate.

Related reading: Fairy tales and youngest sons, Hansel and the trail of stones, and The road between dreams and reality.

July 25, 2019

Happy birthday, Tilly!

Ten years ago we made a decision to bring a dog into our family. Our daughter had suffered a string of losses and we hoped that the companionship of a bouncy young dog might aid in her recovery; and my husband had always been mad about dogs and pined for one of his own. I was the hold-out in the family. It wasn't that I disliked dogs, but I didn't really know much about them. I'd lived with a cat for twenty years -- a big striped tom-cat, feisty and independent -- and dogs by comparison, well, seemed like an awful lot of work.

We dithered about it for a couple of months until an exasperated young friend declared: "Get a dog, or don't get a dog, but don't just keep talking about it!" Learning that a farmer in the north of Devon had a litter of pups ready to leave their mama, we jumped in the car "just to take a look" ... and came back home with a tiny black bundle snoozing calmly on our daughter's lap.

We dithered about it for a couple of months until an exasperated young friend declared: "Get a dog, or don't get a dog, but don't just keep talking about it!" Learning that a farmer in the north of Devon had a litter of pups ready to leave their mama, we jumped in the car "just to take a look" ... and came back home with a tiny black bundle snoozing calmly on our daughter's lap.

Tilly is often mistaken for a small Labrador Retriever, but she's actually a cross known as a Springador: her mother was a liver-and-white Springer Spaniel, and her father was (supposedly) a yellow Lab from a nearby farm. (There was also a big black mutt slinking around, looking mighty pleased with himself.) The entire litter of eight was black but for one male pup with a blaze of white. Tilly looked identical to the others. There was nothing special to distinguish her, and anyway, Howard wanted a boy ... but this tiny scrap of being had her own ideas. We didn't choose our dog, our dog chose us -- quietly, clearly, and with great determination. It was less than an hour's drive back to Dartmoor, but by the time she entered the house in Howard's arms she'd already turned me from a Dog Agnostic to a passionate member of the Dog-loving Tribe.

When Tilly was young, the two of us liked to start our mornings in the garden watching birds: me sitting in a low deck chair, my morning coffee close to hand, with the pup tucked into the folds of my skirt where it stretched between my knees.

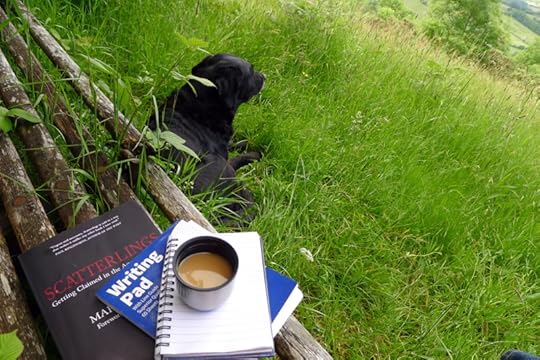

Ten years later, we still often start the day outdoors -- in a field, or the woods, or up on the hill. If the weather is good, I pick a spot to read or write while Tilly sits close by: watching the birds, sniffing the breeze, following the movements of sheep and wild ponies through the fields below.

I can't gather her up in my skirts anymore -- but I love the big, warm bulk of her, and her greying muzzle, and the jowls below her chin. We've both grown older and slower through the years, but the signs of age that discomfort me in myself seem entirely lovely on her.

"We love dogs," writes Erica Jong, "because they show us how to live with with utmost simplicity: Rejoice and kick up your heels after a good shit. Love the one who feeds you. Curl up with the one who strokes your belly. Cherish a good master and lick him into enduring servitude. Celebrate life. Praise God. Find your way home no matter how long it takes. Watch out for the coyotes in the woods. Sniff every corner of the room before you decide to stay there. Turn around three times and create a magic circle before you settle down to dreaming. Decide to trust someone totally before you die.

"These are some of the things I've leaned from the dogs in my life. Cats teach us other lessons -- lessons about keeping your own counsel, cherishing your independence, and giving love without surrendering one's self. Dogs seem more slobbery and slavish. But it is we who become their slaves. As a species, humans are slow to trust. Perhaps that's because we have disregarded our noses for so many millenia. The nose is the only organ that tells it true. By living with dogs, we reclaim the feral in ourselves. We may seek to civilize them, but in truth they help us reclaim the wildness in ourselves. They remind us that in the ancient days we have had much wisdom that we have since sadly abandoned: the wisdom of touch, the wisdom of smell, the wisdom of the senses."

"These are some of the things I've leaned from the dogs in my life. Cats teach us other lessons -- lessons about keeping your own counsel, cherishing your independence, and giving love without surrendering one's self. Dogs seem more slobbery and slavish. But it is we who become their slaves. As a species, humans are slow to trust. Perhaps that's because we have disregarded our noses for so many millenia. The nose is the only organ that tells it true. By living with dogs, we reclaim the feral in ourselves. We may seek to civilize them, but in truth they help us reclaim the wildness in ourselves. They remind us that in the ancient days we have had much wisdom that we have since sadly abandoned: the wisdom of touch, the wisdom of smell, the wisdom of the senses."

"It's not that I was unhappy in what I now think of as 'the dogless years,' " Ann Patchett recalls about the days before her Rose entered her life, "but I suspected things could be better. What I could  never have imagined was how much better they would be. I had entered into my first relationship of mutual, unconditional love....

never have imagined was how much better they would be. I had entered into my first relationship of mutual, unconditional love....

"I watch the other dog owners in the park, married people and single people and people with children. The relationship each one has with his or her dog is very personal and distinct. But what I see again and again is that people are proud of their pets, proud of the way they run, proud of how they nose around with the other dogs, proud that they are brave enough to go into the water or smart enough to stay out of it. People seem able to love their dogs with an unabashed acceptance that they rarely demonstrate with family or friends. The dogs do not disappoint them, or if they do, the owners manage to forget about it quickly. I want to learn to love like this, the way we love our dogs, with pride and enthusiasm and complete amnesia for faults. In short, to love others the way our dogs love us."

Amen.

Words: The passages quoted above are from "A Woman's Best Friend" by Erica Jong and "This Dog's Life" by Ann Patchett, published in Dog is My Co-Pilate (Tree Rivers Press, 2003). The poem in the picture captions is from Poetry magazine (August issue, 1999). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The first drawing of Tilly as a young pup is from preliminary sketches for In the Word Wood by David Wyatt. The second Tilly sketch, also by David, is called "The Birthday Jig." The little colour drawings of Tilly are from Kathleen Jenning's sketchbook. Photographs: Tilly at eight weeks old, ten weeks old, and ten years old.

July 24, 2019

A quiet morning in the studio

Some time ago I stumbled across these words by children's book writer Cornelia Funke (author of The Thief Lord, Inkheart, etc.), and they've been pinned to the wall above my desk ever since:

"I pledge to use books as doors to other minds, old and young, girl and boy, man and animal.

"I pledge to use books to open windows to a thousand different worlds and to the thousand different faces of my own world.

"I pledge to use books to make my universe spread much wider than the world I live in every day.

"I pledge to treat my books like friends, visiting them all from time to time and keeping them close."

In American Gods, Neil Gaiman reflects on why we need to keep writing and telling stories:

"There was a girl, and her uncle sold her. Put like that it seems so simple.

"No man, proclaimed Donne, is an island, and he was wrong. If we were not islands, we would be lost, drowned in each other's tragedies. We are insulated (a word that means, literally, remember, made into an island) from the tragedy of others, by our island nature and by the repetitive shape and form of the stories. The shape does not change: there was a human being who was born, lived and then by some means or other, died. There. You may fill in the details from your own experience. As unoriginal as any other tale, as unique as any other life. Lives are snowflakes -- forming patterns we have seen before, as like one another as peas in a pod (and have you ever looked at peas in a pod? I mean, really looked at them? There's not a chance you'll mistake one for another, after a minute's close inspection) but still unique.

"Without individuals we see only numbers, a thousand dead, a hundred thousand dead, 'casualties may rise to a million.' With individual stories, the statistics become people- but even that is a lie, for the people continue to suffer in numbers that themselves are numbing and meaningless. Look, see the child's swollen, swollen belly and the flies that crawl at the corners of his eyes, this skeletal limbs: will it make it easier for you to know his name, his age, his dreams, his fears? To see him from the inside? And if it does, are we not doing a disservice to his sister, who lies in the searing dust beside him, a distorted distended caricature of a human child? And there, if we feel for them, are they now more important to us than a thousand other children touched by the same famine, a thousand other young lives who will soon be food for the flies' own myriad squirming children?

"We draw our lines around these moments of pain, remain upon our islands, and they cannot hurt us. They are covered with a smooth, safe, nacreous layer to let them slip, pearllike, from our souls without real pain.

"Fiction allows us to slide into these other heads, these other places, and look out through other eyes. And then in the tale we stop before we die, or we die vicariously and unharmed, and in the world beyond the tale we turn the page or close the book, and we resume our lives.

"A life that is, like any other, unlike any other.

"And the simple truth is this: There was a girl, and her uncle sold her."

In A Way of Being Free, Ben Okri advises that we take good care of the stories that come to us:

"There are ways in which stories create themselves, bring themselves into being, for their own inscrutable reasons, one of which is to laugh at humanity's attempts to hide from its own clay. The time will come when we realize that stories choose us to bring them into being for the profound needs of humankind. We do not choose them.

"Even when tragic, storytelling is always beautiful. It tells us that all fates can be ours. It wraps up our lives with the magic which we only see long afterwards. Storytelling connects us to the greater sea of human destiny, human suffering, and human transcendence."

And in Walking on Water, Madeleine L'Engle declares:

"If the work comes to the artist and says, 'Here I am, serve me,' then the job of the artist, great or small, is to serve. The amount of the artist's talent is not what it is about. Jean Rhys said to an interviewer in the Paris Review, 'Listen to me. All of writing is a huge lake. There are great rivers that feed the lake, like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. And there are mere trickles, like Jean Rhys. All that matters is feeding the lake. I don't matter. The lake matters. You must keep feeding the lake.' "

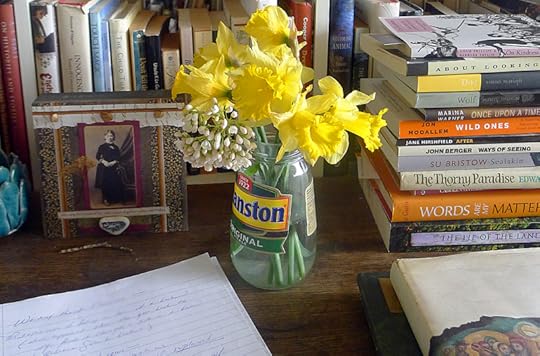

Words: I'm afraid I don't remember where I came across the quote from Cornelia Funke, but the others can be found in American Gods by Neil Gaiman (Headline, 2005), A Way of Being Free by Ben Okri (W&N, 1997), and Walking on Water by Madeleine L'Engle (Waterbrook Press, 2001). The Jean Rhys quote cited by L'Engle is from "The Art of Fiction, #64" (Paris Review, Fall 1979). The poem in the picture captions is from Circles on the Water by Marge Piercy (Knopf, 1982). All rights reserved by the authors.

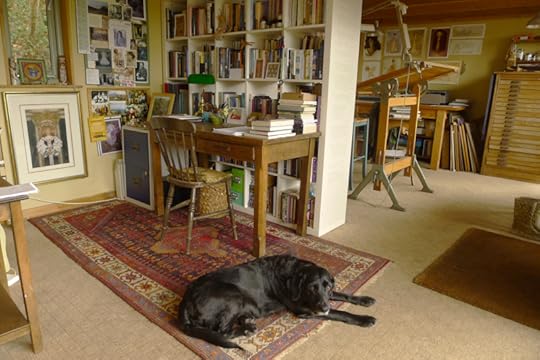

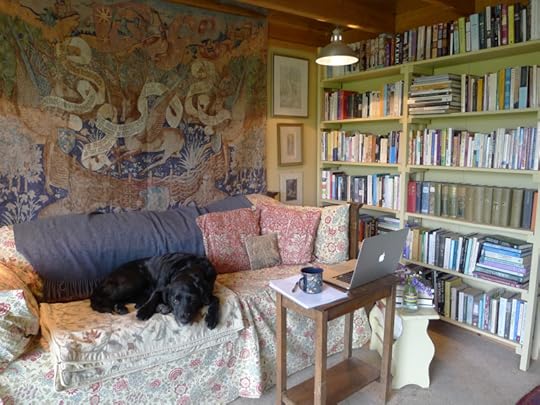

Pictures: A quiet summer morning in my work studio, built from recycled materials on a green hillside in Devon.

Related reading: The Hunger for Narrative, A Trail of Stories, and Touching the Source.

July 23, 2019

The Sense of Wonder

"As a child, one has that magical capacity to move among the many eras of the earth," writes Valerie Andrews in A Passion for this Earth; "to see the land as an animal does; to experience the sky from the perspective of a flower or a bee; to feel the earth quiver and breathe beneath us; to know a hundred different smells of mud and listen unselfconsciously to the soughing of the trees."

But as Jay Griffiths cautions in her extraordinary book Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape: "Children have been exiled from their kith, their square mile, a land right of the human spirit. Naturally kindled in green, they need nature, woodlands, mountains, rivers and seas both physically and emotionally, no matter how small a patch; children's spirits can survive on very little, but not on nothing. Yet woodlands are privatized ... while even the streets -- the commons of the urban child -- have been closed off to them."

What can we do to bring them back to the wild? Both the wild in the landscape and the wild in themselves?

"By suggestion and example, I believe children can be helped to hear the many voices about them," ecologist Rachel Carson wrote in The Sense of Wonder (published posthumously in 1965). "Take time to listen and talk about the voices of the earth and what they mean -- the majestic voice of thunder, the winds, the sound of surf or flowing streams."

Carson's words were important back in the '60s, and they are even more so today. As Alan Dyer states in "A Sense of Adventure" (Resurgence Magazine, Sept/Oct 2004):

"Children the world over have a right to a childhood filled with beauty, joy, adventure, and companionship. They will grow toward ecological literacy if the soil they are nurtured in is rich with experience, love, and good examples."

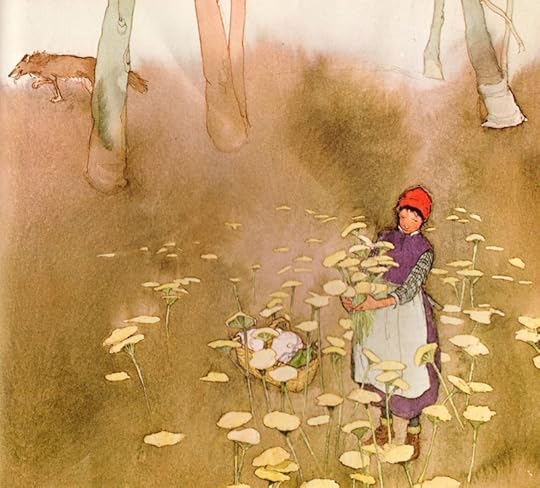

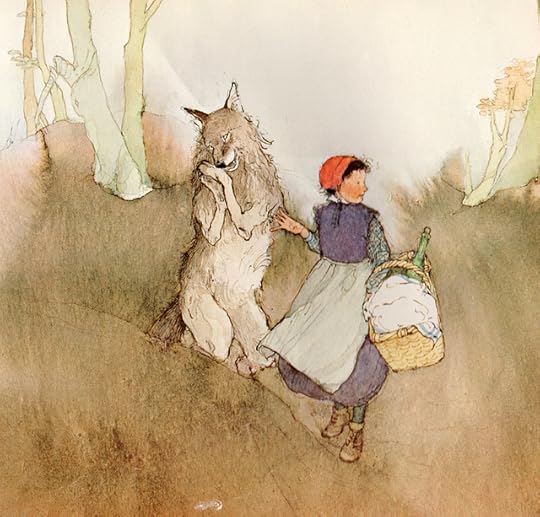

The paintings today are by one of my all-time favorite artists, the extraordinary Lisbeth Zwerger. Born in Vienna, Austria in 1954, she studied at the Applied Arts Academy in that city and has been illustrated  children's books since 1977, winning the prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Medal for "lasting contributions to children's literature" in 1990. Zwerger has very little web presence of her own, but you can find examples of her art on Pinterest and Tumblr -- or better still, go to her glorious books, including many fine illustrated editions of fairy tales by the Grimms, Andersen, and Oscar Wilde; classics such as Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz, The Nutcracker, and A Christmas Carol; and a very lovely art book, The Art of Lisbeth Zwerger -- which sits paint-stained and much-thumbed-through near my own drawing board, a constant source of inspiration.

children's books since 1977, winning the prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Medal for "lasting contributions to children's literature" in 1990. Zwerger has very little web presence of her own, but you can find examples of her art on Pinterest and Tumblr -- or better still, go to her glorious books, including many fine illustrated editions of fairy tales by the Grimms, Andersen, and Oscar Wilde; classics such as Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz, The Nutcracker, and A Christmas Carol; and a very lovely art book, The Art of Lisbeth Zwerger -- which sits paint-stained and much-thumbed-through near my own drawing board, a constant source of inspiration.

July 22, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Music, magic, stories....

Above: "The Kingdom" by American singer/songwriter Jesca Hoop, who is based in Manchester, England. The song is from her second album, Hunting My Dress (2009).

Below: "Blood Moon" by the Irish folk-electronica duo Saint Sister (Gemma Doherty & Morgan MacIntyre), from their debut, Shape of Silence (2018).

Above: "Riverside" by Danish singer-songwriter Agnes Obel, born in Gentofte and now based in Berlin. The song is from her first album, Philharmonics (2010).

Below: "Garden District" by French harpist and singer C��cile Corbel, from Finist��re in the far west of Brittany. The song appeared on Roses, the fourth volume in her SongBook series of albums (2014).

Above: "The Snow Queen" by British singer/songwrite Ana Silvera, based in London. The song is from her very beautiful album Aviary (2013).

Below: "Gravity" by American singer/songwriter Vienna Teng, born in California and now based in Detroit. The song is from her first studio album, The Waking Hour (2002).

Pictures: wild words in the woods. The fairy tale openings in the picture captions were taken from a Guardian article by Kate Lyons.

July 19, 2019

I'm telling you stories. Trust me.

From "Potato Soup" by Marina Warner (published in her short history of fairy tales, Once Upon a Time):

"Princes and queens, palaces and castles dominate the foreground of a fairy tale, but through the gold and glitter, the depth of the scene is filled vivid and familiar circumstances, as the fantastic faculties engage with the world of experience. Realism of content also embraces precise observation of detail, and contrasts between earthiness and preposterous fancy sharpen the entertaining effect.

"Charles Perrault tells us, for example, that Cinderella's cruel sisters have dressmakers' pins from England, the most fashionable and most coveted article at the time. In the Grimms' The Three Golden Hairs, the Devil himself is the adversary, and hell is a kitchen much like any ordinary kitchen where his granny sits by the stove. When the brave hero appears, a poor lad who's been set an impossible task by the proud princess to fetch her the trophy (the hairs in the title), Granny is kind to him, and turns the boy into an ant to keep him safe. She hides him in the folds of her apron until she herself has pulled out the three hairs, shushing the Devil as she does so. She then turns our hero back again into human form and sends him back to the world above to marry the princess.

"It is emblematic that the Devil's kind old granny can pull out the required hairs because she is de-lousing him, something that's comforting even in Hell. Each of the three hairs then brings about a blessing that makes a joke of the story's roots in toil and hunger: with the first, the Devil reveals that a spring has died up because an old toad is squatting on a stone that's blocking it; with the second that an apple tree no longer bears fruit because a mouse is nibbling through its roots; and with the third that the ferryman, who's working day in and day out, poling passengers across the river need only put his pole in the hands of one of his passengers to be free.

"Many fairy tales about golden-haired princesses with tiny feet still address the difficulty, in an era of arranged marriage and often meagre resources, of choosing a beloved and being allowed to live with him or her. Many explore other threats all too familiar to the stories' receivers: the loss of a mother to childbirth is a familiar, melancholy opening to many favourites.

"Behind their gorgeous surfaces you can glimpse an entire history of childhood and the family: the oppression of land-owners and rulers, the ragamuffin orphan surviving by his wits, the maltreated child who wants a day off from unending toil, or the likely lad who has his eye on a girl who's from a better class than himself, the dependence of old people, the rivalries between competitors for love and other sustenance.

"Unlike myths, which are about gods and superheroes, fairy tale protagonists are recognizably ordinary working people, toiling at ordinary occupations over a long period of history, before industrialization and mass literacy. In the Arabian Nights the protagonists belong to more urban settings, and practice trades and commerce. Some are abducted and then sold into slavery, many are cruelly driven by their masters and mistresses. In the European material, the drudgery is more rural, the enslavement more personal in its cruelty. It is fair to say tale fairy tale heroines are frequently skivvies who take on the housework uncomplainingly, and that this kind of story won favour in the Victorian era and later, at the cost of eclipsing lively rebel protagonists, tricksters like Finette (Finessa in Engligh translation), who turns the tables on her sisters' seducers, or Marjana the slave girl who pours boiling oil on the Forty Thieves.

"Direct and shared experiences of material circumstances -- of the measure sociologists use to establish the well-being of a given society -- are taken up by fairy tales as a matter of course: when the mother dies giving birth, that child will have to survive without her love and protection, and that is a grim sentence. The pot of porridge that is never empty speaks volumes about a world where hunger and want and dreadful toil are the lot of the majority, whose expectations are rather modest by contemporary standards. 'A fairy tale,' Angela Carter once remarked, 'is a story in which one king goes to another to borrow a cup of sugar.'

"D.H. Lawrence famously proclaimed, 'Trust the tale, not the teller.' To which Jeanette Winterson retorts, repeating again and again, 'I'm telling you stories. Trust me.' But in what ways can we trust the tale -- and even trust the teller? How can such preposterous fantastic stories be true, as Italo Calvino and others who value fairy tales have claimed?

"One answer is that a story is an archive, packed with history: just as an empty field in winter can reveal, to the eye of an ancient archaeologist, what once grew there, how long ago the forest was cleared to make way for pasture, and where the rocks that were picked out of the land eventually fetched up, so a fairy tale bears the marks of the people who told it over the years, of their lives and their struggles.

"C.S. Lewis writes that in literature there is realism of presentation on the one hand, and realism of content on the other: 'The two realisms are quite independent. You can get that of presentation without that of content, as in medieval romance; or that of content without that of presentation, as in French (and some Greek) tragedy; or both together, as in War and Peace; or neither, as in the Furioso or Rasselas or Candide.'

"According to these distinctions, it is possible to see how fairy tales, while being utterly fantastical in presentation, are forthright in their realism as to what happens and can happen....

"The happy ending, that defining dynamic of fairy tales, follows their relation to reality. Ordinary misery and its causes are the stories' chief concern. But writers -- and storytellers -- address their topics with craft, and it is often more compelling to translate experience through metaphor and fantasy than to put it plainly. As C.S. Lewis wrote in the title of one of his essays, 'Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What's To Be Said.'

"Even a writer as dreamy (and privileged) as the German Romantic Novalis defined the form as a way of thinking up a way out: 'A true fairytale must also be a prophetic account of things -- an ideal account -- an absolutely necessary account. A true writer of fairy tales sees into the future."

"The stories face up to the inadmissable facts of reality and promise deliverance. This honest harshness combined with the wishful hoping has helped them to last. If literature is the place we go to, in Seamus Heaney's words, 'to be forwarded within ourselves,' then fairy tales form an important part of it. If literature gives 'an experience that is like foreknowledge of certain things which we already seem to be remembering,' fairy tales offer enigmatic, terrifying images of what the prospects are, of the darkest horrors life may bring. Yet the stories usually imagine ways of opposing this state of affairs, or at worst, of having revenge on those who inflict suffering, of turning the status quo upside down, as well as defeating the natural course of events; they dream of reprisals, and they sketch alternative plots lines. They are messages of hope arising from desperate yet ordinary situations."

Likewise, Lynda Barry has said:

"There are certain children who are told they are too sensitive, and there are certain adults who believe sensitivity is a problem that can be fixed in the way that crooked teeth can be fixed and made straight. And when these two come together you get a fairy tale, a kind of story with hopelessness in it. I believe there is something in these old stories that does what singing does to words. They have transformational capabilities, in the way melody can transform mood. They can't transform your actual situation, but they can transform your experience of it. We don't create a fantasy world to escape reality, we create it to be able to stay.

"I believe we have always done this, used images to stand and understand what otherwise would be intolerable.���

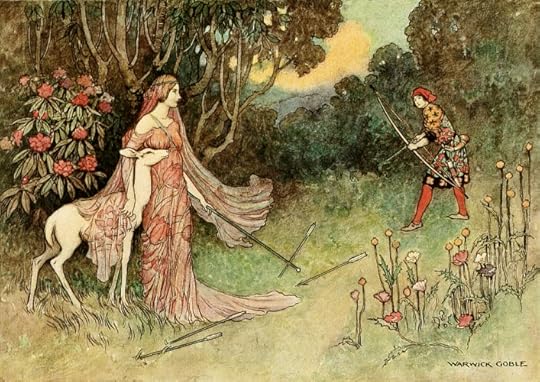

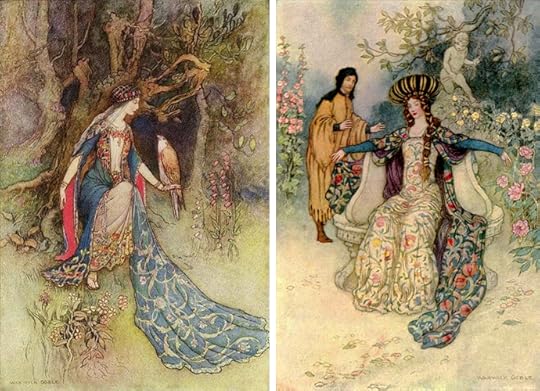

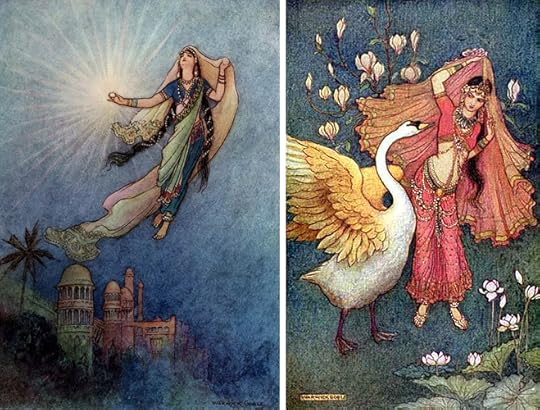

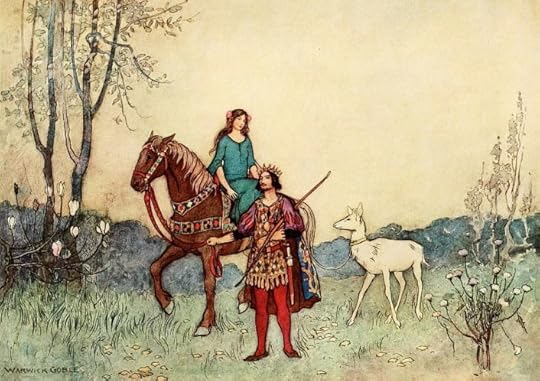

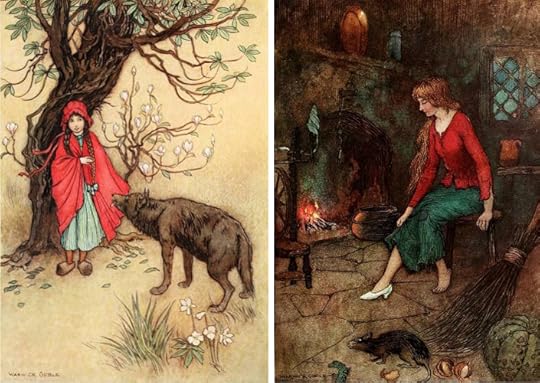

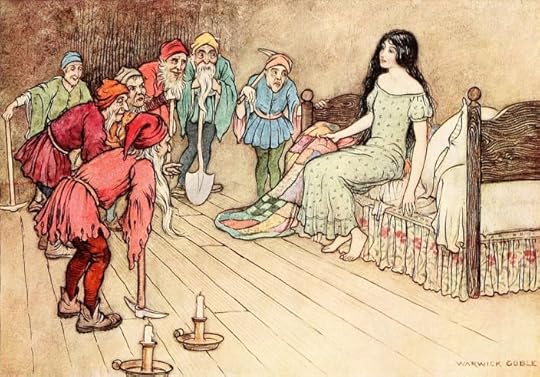

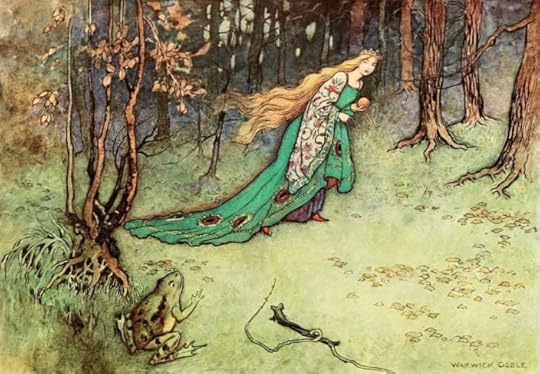

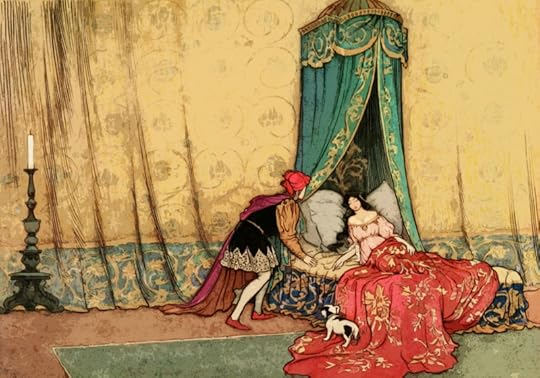

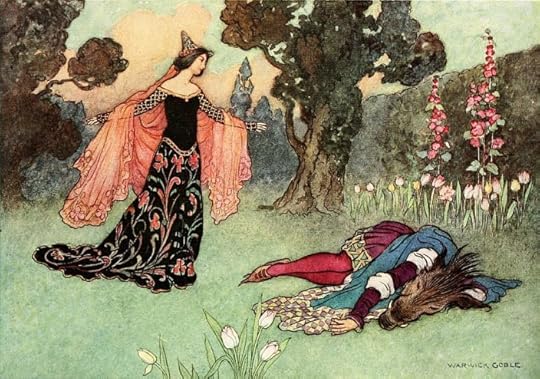

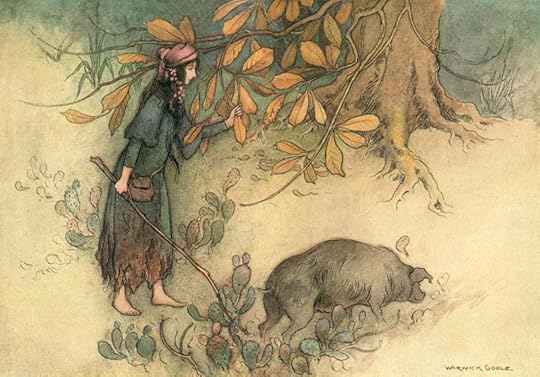

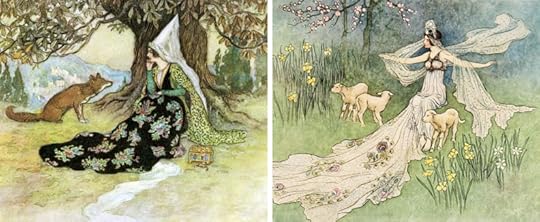

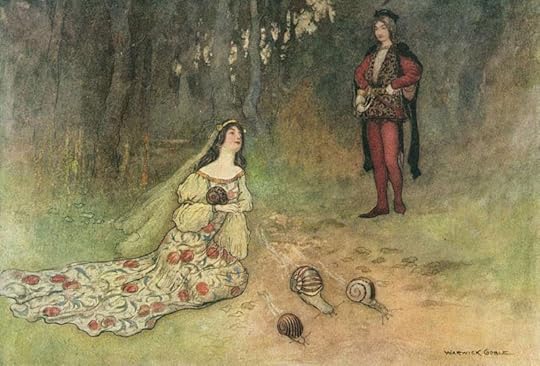

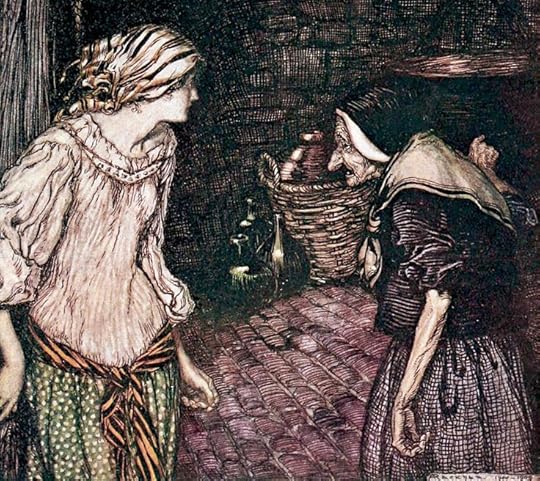

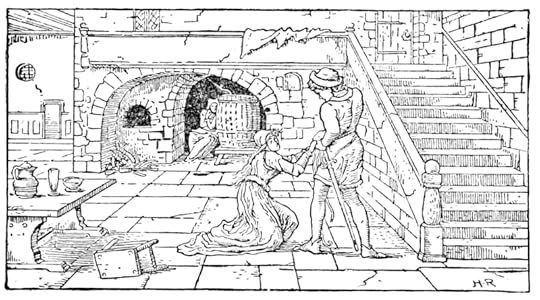

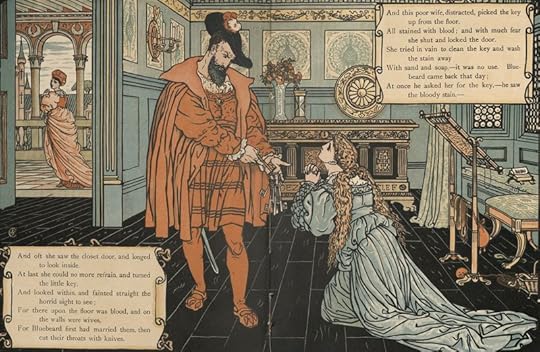

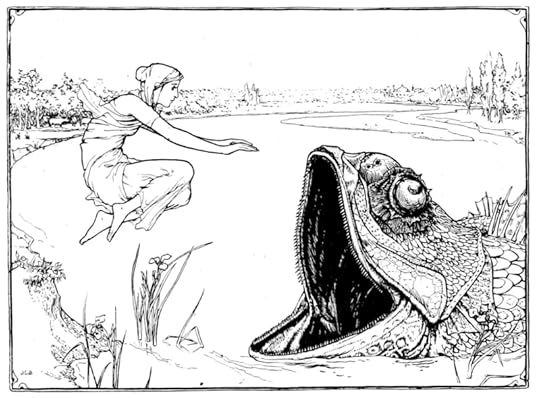

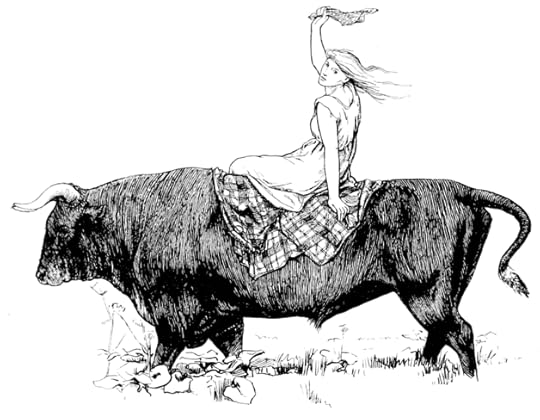

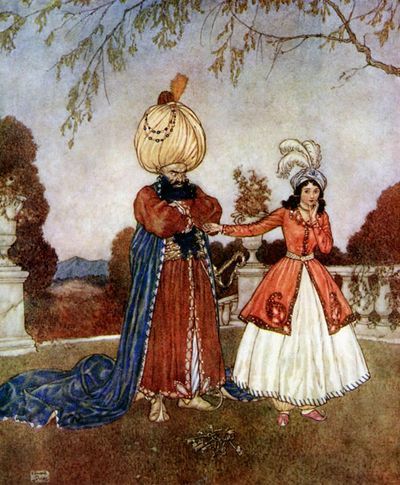

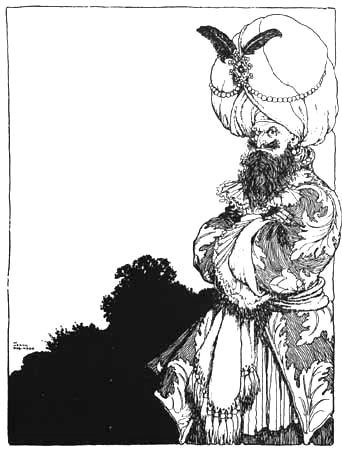

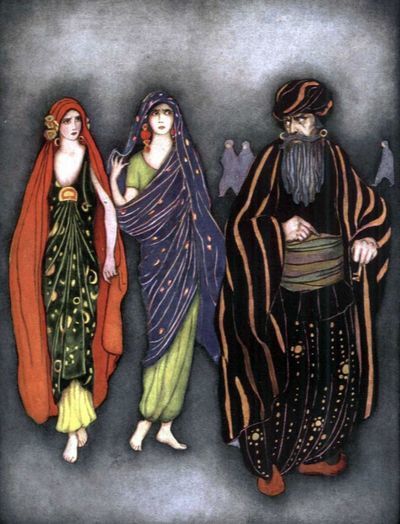

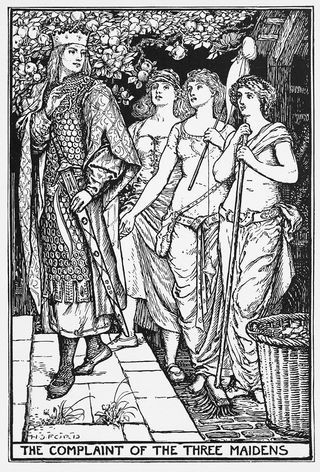

Pictures: The art today is by Warwick Goble (1862-1943). Born in north London, he trained at the Westminster School of Art and worked for a printing company before becoming a popular illustrator of fairy tale books and other editions for children and adults.

Words: The passages above are from Once Upon a Time: A Short History of Fairy Tale by Marina Warner (Oxford University Press, 2014), and What Is It (Drawn & Quaterly, 2008), by cartoonist Lynda Barry. All rights reserved by the authors.

July 18, 2019

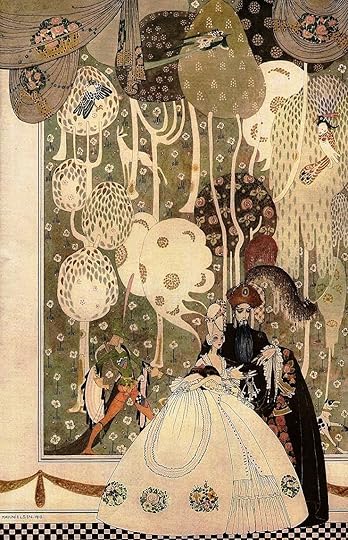

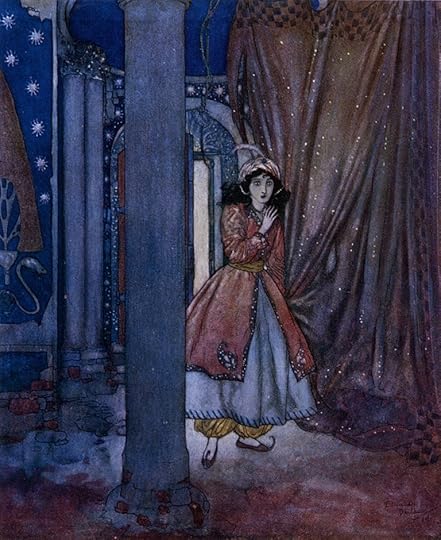

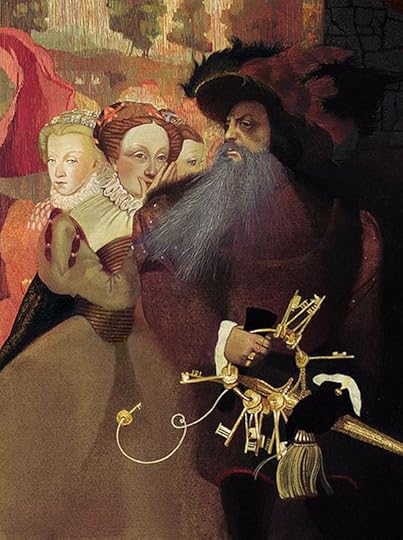

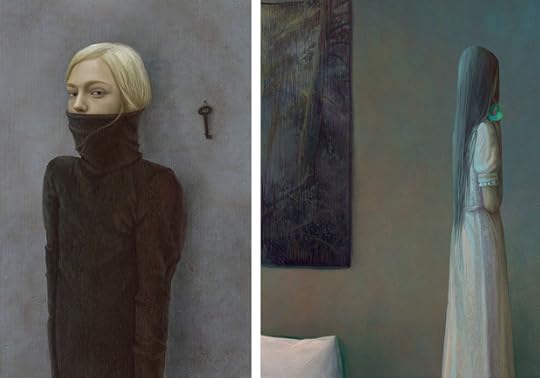

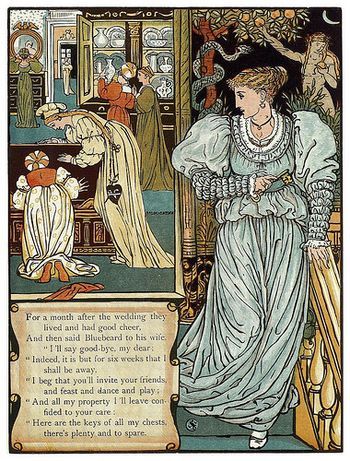

The story of Bluebeard

Though based on older folk tales of demon lovers and devilish bridegrooms, the story of Bluebeard, as we know it today, is the creation of French writer Charles Perrault -- first published in 1697 in his collection Histoires ou contes du temps pass�� (Stories or Tales of Past Times). Perrault was one in a group of writers who socialized in the literary salons of Paris, collectively creating a vogue for literature inspired by peasant folk tales. These new stories were called contes des fe��s, from which our modern term "fairy tales" derives -- but the contes des fe��s of the French salons were intended for adult readers.

Bluebeard, for example, has little to recommend it as a children's story. Rather, it's a gruesome cautionary tale about the dangers of marriage (on the one hand) and the perils of greed and curiosity (on the other) -- more akin, in our modern culture, to horror films than to Disney cartoons. The story as Perrault tells it is this: A wealthy man, wishing to wed, turns his attention to the two beautiful young daughters of his neighbor, a widow. Neither girl wants to marry the man because of his ugly blue beard -- until he invites the girls and their mother to a party at his country estate. Seduced by luxurious living, the youngest daughter agrees to accept Bluebeard's hand. The two are promptly wed and the girl becomes mistress of his great household. Soon after, Bluebeard tells his wife that business calls him to make a long journey. He leaves her behind with all the keys to his house, his strong boxes, and his caskets of jewels, telling her she may do as she likes with them and to "make good cheer." There is only one key that she may not use, to a tiny closet at the end of the hall. That alone is forbidden, he tells her, "and if you happen to open it, you may expect my just anger and resentment."

Bluebeard, for example, has little to recommend it as a children's story. Rather, it's a gruesome cautionary tale about the dangers of marriage (on the one hand) and the perils of greed and curiosity (on the other) -- more akin, in our modern culture, to horror films than to Disney cartoons. The story as Perrault tells it is this: A wealthy man, wishing to wed, turns his attention to the two beautiful young daughters of his neighbor, a widow. Neither girl wants to marry the man because of his ugly blue beard -- until he invites the girls and their mother to a party at his country estate. Seduced by luxurious living, the youngest daughter agrees to accept Bluebeard's hand. The two are promptly wed and the girl becomes mistress of his great household. Soon after, Bluebeard tells his wife that business calls him to make a long journey. He leaves her behind with all the keys to his house, his strong boxes, and his caskets of jewels, telling her she may do as she likes with them and to "make good cheer." There is only one key that she may not use, to a tiny closet at the end of the hall. That alone is forbidden, he tells her, "and if you happen to open it, you may expect my just anger and resentment."

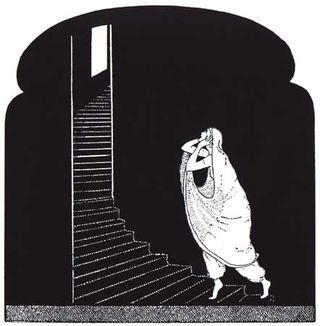

Of course, the very first thing the young wife does is to run to the forbidden door "with such excessive haste that she nearly fell and broke her neck." She has promised obedience to her husband, but a combination of greed and curiosity (the text implies) propels her to the fatal door the minute his back is turned. She opens it and finds a shuttered room, its floor awash in blood, containing the murdered corpses of Bluebeard's previous young wives. Horrified, the young wife drops the key into a puddle of blood. Retrieving it, she locks the room and runs back to her own chamber. Now she attempts to wash the key so that her transgression will not be revealed -- but no matter how long and hard she scrubs it, the bloodstain will not come off.

Of course, the very first thing the young wife does is to run to the forbidden door "with such excessive haste that she nearly fell and broke her neck." She has promised obedience to her husband, but a combination of greed and curiosity (the text implies) propels her to the fatal door the minute his back is turned. She opens it and finds a shuttered room, its floor awash in blood, containing the murdered corpses of Bluebeard's previous young wives. Horrified, the young wife drops the key into a puddle of blood. Retrieving it, she locks the room and runs back to her own chamber. Now she attempts to wash the key so that her transgression will not be revealed -- but no matter how long and hard she scrubs it, the bloodstain will not come off.

That very night, her husband returns -- his business has been suddenly concluded. Trembling, she pretends that nothing has happened and welcomes him back. In the morning, however, he demands the return of the keys and examines them carefully. "Why is there blood on the smallest key?" he asks her craftily. Bluebeard's wife protests that she does not know how it came to be there. "You do not know?" he roars. "But I know, Madame. You opened the forbidden door. Very well. You must now go back and take your place among my other wives."

Tearfully, she delays her death by asking for time to say her prayers -- for her brothers are due to visit that day, her only hope of salvation. She calls three times to her sister Anne in the tower room at the top of the house ("Sister Anne, Sister Anne, do you see anyone coming?") And at last they come, just as Bluebeard raises a sword to chop off her head. The murderous husband is dispatched, his wealth disbursed among the family, and the young wife is married again, Perrault tells us, to "a very worthy gentleman who made her forget the ill time she had passed with Bluebeard."

This bloodthirsty tale is quite different in tone from the other tales in Perrault's Histoires (the courtly confections of "Sleeping Beauty," "Cinderella," etc.), and its history has been a source of debate among fairy tale scholars. Some assert that Perrault was inspired by the historical figure of Gilles de Rais, a fifteenth century Marshal of France and companion at arms to Joan of Arc. After driving the English out of France, this martial hero returned to his Breton estate where, a law unto himself, he practiced alchemy and dark magic while young peasant boys began to disappear across his lands. Rumors swirled around de Rais and when, at last, the Duke of Brittany intervened and investigated, the remains of over fifty boys were dug up in de Rais's castle. He later confessed to sodomizing and killing one hundred and forty boys, although the actual number may be closer to three hundred. De Rais was simultaneously hanged and burned alive for these crimes in 1440.

This bloodthirsty tale is quite different in tone from the other tales in Perrault's Histoires (the courtly confections of "Sleeping Beauty," "Cinderella," etc.), and its history has been a source of debate among fairy tale scholars. Some assert that Perrault was inspired by the historical figure of Gilles de Rais, a fifteenth century Marshal of France and companion at arms to Joan of Arc. After driving the English out of France, this martial hero returned to his Breton estate where, a law unto himself, he practiced alchemy and dark magic while young peasant boys began to disappear across his lands. Rumors swirled around de Rais and when, at last, the Duke of Brittany intervened and investigated, the remains of over fifty boys were dug up in de Rais's castle. He later confessed to sodomizing and killing one hundred and forty boys, although the actual number may be closer to three hundred. De Rais was simultaneously hanged and burned alive for these crimes in 1440.

There is another old Breton tale, however, which relates more closely to Bluebeard's story: that of Cunmar the Accursed, who beheaded a succession of wives, one after the other, when they became pregnant. Cunmar was an historical figure, the ruler of Brittany in the mid-sixth century, but the legend attached to him has its roots in folk tales, not history.

The story concerns a nobleman's daughter, Triphine, the last of Cunmar's wives. Heavily pregnant with his son, she enters Cunmar's ancestral chapel where she is warned of her fate by the bloodstained ghosts of his previous wives. She flees to the woods, but her husband pursues her, cuts off her head and leaves her to die. Her body is found by Gildas, the abbot of Rhuys, who is destined to be a saint. Miraculously, he re-attaches the head and brings her back to life. The two follow Cunmar back to his castle, where Gildas causes the walls themselves to crash down on the murderer. Triphine's son is safely delivered, given to Gildas and the church, and Triphine devotes the rest of her life to prayer and performing good works. Eventually, she too is sainted (depicted in religious statues and paintings as carrying her own severed head) -- while the ghost of Cunmar continues to haunt the country in the form of a werewolf. The Bluebeard parallel becomes stronger yet when one considers a series of frescoes depicting Triphine's story in the Breton church St. Nicholas des Eaux. One panel of these medieval paintings shows Cunmar handing a key to his young bride, while another shows her entering the chamber where his previous wives are hanging.

The story concerns a nobleman's daughter, Triphine, the last of Cunmar's wives. Heavily pregnant with his son, she enters Cunmar's ancestral chapel where she is warned of her fate by the bloodstained ghosts of his previous wives. She flees to the woods, but her husband pursues her, cuts off her head and leaves her to die. Her body is found by Gildas, the abbot of Rhuys, who is destined to be a saint. Miraculously, he re-attaches the head and brings her back to life. The two follow Cunmar back to his castle, where Gildas causes the walls themselves to crash down on the murderer. Triphine's son is safely delivered, given to Gildas and the church, and Triphine devotes the rest of her life to prayer and performing good works. Eventually, she too is sainted (depicted in religious statues and paintings as carrying her own severed head) -- while the ghost of Cunmar continues to haunt the country in the form of a werewolf. The Bluebeard parallel becomes stronger yet when one considers a series of frescoes depicting Triphine's story in the Breton church St. Nicholas des Eaux. One panel of these medieval paintings shows Cunmar handing a key to his young bride, while another shows her entering the chamber where his previous wives are hanging.

It's possible that Charles Perrault knew the story of Cunmar the Accursed, using details from it to color his own. Or it may simply be that he knew other similar stories from French and Italian peasant lore, with their wide range of "monstrous bridegroom" and "murderous stranger" motifs. Indeed, these motifs are ones we find in folk traditions around the world. But in marked contrast to Perrault's Bluebeard (the best known of such tales today), in the old peasant stories the heroine does not weep and wait for her brothers' rescue -- rather, she's a cunning, clever girl fully capable of rescuing herself.

In the Italian tale Silvernose (as compiled by Italo Calvino from three regional variants and published in Italian Folktales), the devil, disguised as a nobleman, visits a widowed washerwoman and asks for her eldest daughter to come and work in his fine house. The widow distrusts the man's strange  nose, but her daughter agrees to go nonetheless, bored as she is with life at home and looking for an adventure. She follows Silvernose to his palace, where she's given keys to all the fine rooms. He gives her the run of the place -- except for one door which she may not unlock. That night, Silvernose enters her room and leaves a rose in her hair as she sleeps. In the morning, he rides off on business, leaving his young servant behind. Immediately she opens the forbidden door. Inside, she finds hell itself -- a fiery room where the souls of the damned writhe in eternal torment. The horrified girl swiftly slams the door shut, but the flower in her hair has been singed. When Silvernose returns, the flower is proof of her transgression. "So that's how you obey me!" he cries, opening the door and tossing her in.

nose, but her daughter agrees to go nonetheless, bored as she is with life at home and looking for an adventure. She follows Silvernose to his palace, where she's given keys to all the fine rooms. He gives her the run of the place -- except for one door which she may not unlock. That night, Silvernose enters her room and leaves a rose in her hair as she sleeps. In the morning, he rides off on business, leaving his young servant behind. Immediately she opens the forbidden door. Inside, she finds hell itself -- a fiery room where the souls of the damned writhe in eternal torment. The horrified girl swiftly slams the door shut, but the flower in her hair has been singed. When Silvernose returns, the flower is proof of her transgression. "So that's how you obey me!" he cries, opening the door and tossing her in.

He then returns to the washerwoman, and asks for the second daughter. The middle girl meets her sister's fate. But the youngest daughter, Lucia, is cunning. She too follows Silvernose to his palace, she too is given the forbidden key, she too has a flower placed in her hair as she lies asleep. But she notices the flower and puts it safely away in a jar of water. Then she opens the door, pulls her sisters out of the flames, and plots their escape. When Silvernose comes home, the flower is back in her hair, as fresh as ever. The devil is pleased. Here's a servant at last who will bind herself to his will.

Lucia prevails upon him then to carry some laundry back to her mother. Her eldest sister is hidden inside the bag, which is very heavy. "You must take it straight to my mother," she says, "for I have a special ability to see from great distances, and if you stop to rest and put that bag down, I will surely know." The devil starts upon his trip, grows tired, and begins to put the bag down. "I see you, I see you!" the eldest sister cries from inside the laundry bag; and thinking it's Lucia's voice, Silvernose hurries on. Lucia repeats this ruse for the middle sister. Then she hides in the third bag herself, along with a store of gold pilfered from the devil's treasury. Reunited with their mother (and wealthy now besides), the sisters plant a cross in the yard and the devil keeps his distance.

The Italian story Silvernose is similar to an old German tale called Fitcher's Bird, collected by the Brothers Grimm and published in Kinder- und Hausmarchen. In this story, the Bluebeard figure is a mysterious wizard disguised as a beggar. The wizard appears at the door of a household with three beautiful unmarried daughters. He asks the eldest for something to eat, and just as she hands the beggar some bread he touches her, which causes her to jump into the basket he carries. He spirits the girl away to his splendid house and gives her keys to its rooms, but forbids her, under penalty of death, to use the smallest key. The next day he sets off on a journey, but before he leaves he gives her an egg, instructing the girl to carry the egg with her everywhere she goes. As soon as he leaves she explores the house, and although she tries to ignore the last key, curiosity gets the better of her and she opens the final door. Inside she finds an ax and a basin filled with blood and body parts. In shock, she drops the egg in the blood, and then cannot wipe off the stain. When the wizard comes home, he demands the return of the keys and the egg, and discovers her deed. "You entered the chamber against my wishes, now you will go back in against yours. Your life is over," he cries, and cuts her into little pieces.

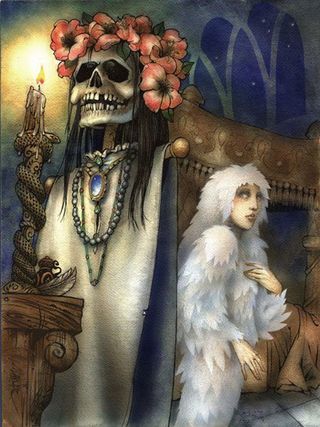

This sequence of events is repeated with the second daughter, and then with the third -- except that the youngest girl is the clever one. She puts the egg carefully away before she enters the forbidden chamber, determined to rescue her sisters. Inside, she finds her sisters chopped up into pieces. She promptly gets to work reassembling the body parts, piece by bloody piece. When her sisters' limbs are all in place, the pieces knit themselves back together and the two elder girls come back to life with cries of joy. Then they must hide as the wizard returns. He calls for the youngest and asks for the egg. She hands it over, and he can find no stain or blemish on it. "You have passed the test," he informs her, "so tomorrow you shall be my bride."

This sequence of events is repeated with the second daughter, and then with the third -- except that the youngest girl is the clever one. She puts the egg carefully away before she enters the forbidden chamber, determined to rescue her sisters. Inside, she finds her sisters chopped up into pieces. She promptly gets to work reassembling the body parts, piece by bloody piece. When her sisters' limbs are all in place, the pieces knit themselves back together and the two elder girls come back to life with cries of joy. Then they must hide as the wizard returns. He calls for the youngest and asks for the egg. She hands it over, and he can find no stain or blemish on it. "You have passed the test," he informs her, "so tomorrow you shall be my bride."

The girl agrees that she will wed the wizard, under this condition: "First take a basket of gold to my father. You must promise to carry it on your back, and you mustn't stop along the way. I'll be watching you from the window." The two elder girls are hidden inside the basket, beneath a king's ransom in gold. The wizard picks it up and stumbles off, sweating under his burden. Yet every time he stops to rest, he hears one of the sisters saying: "I see you, I see you! Don't put the basket down! Keep moving!" Thinking it's the voice of his bride, the wizard continues on his way -- while the youngest girl invites the wizard's friends to a wedding feast. She takes a skull from the bloody room, crowns it with garlands of flowers and jewels, and sets it in the attic window, facing the road below. Then she crawls into a barrel of honey, cuts open a featherbed, and rolls in the feathers until she's completely  disguised as a strange white bird. As she leaves the house, she meets the wizard's equally evil friends coming toward it. They say to her:

disguised as a strange white bird. As she leaves the house, she meets the wizard's equally evil friends coming toward it. They say to her:

"Oh Fitcher's bird, where are you from?"

"From feathered Fitcher's house I've come."

"The young bride there, what has she done?"

"She's cleaned and swept the house all through;

She's in the window looking at you."

She then meets the wizard himself on the road, and these questions are repeated. The wizard looks up, he sees the skull in the window, and hurries home to his bride. But by now, the brothers and relatives of the three young girls are waiting for him. They lock the door, then burn the house down with all the sorcerers inside. (The unexplained name Fitcher, according to Marina Warner, "derives from the Icelandic fitfugl, meaning 'web-footed bird', so there may well be a buried memory here of those bird-women who rule narrative enchantments.")

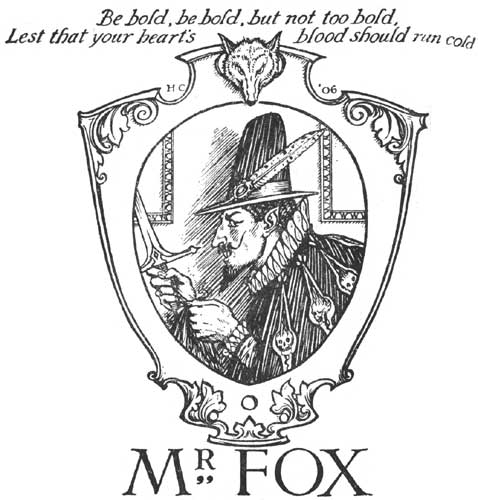

The Robber Bridegroom is another classic fairy tale about a murderous stranger. It too can be found in Germany and Italy, and in variants around the world. One of the most evocative of these variants is the English version of the story, in which the Bluebeard figure is known as Mr. Fox (or Reynardine). A girl is courted by a handsome russet-haired man who appears to have great wealth. He is charming, well mannered, well groomed, but his origins are mysterious. As the wedding day grows near, it troubles the girl that she's never seen his home -- so she takes matters into her own hands and sets off  through the woods to seek it. In the dark of the woods, she finds a high wall and a gate. Over the gate it says: Be bold. She enters, and finds a large, dilapidated mansion inside. Over the entrance it says: Be bold, be bold. She enters a gloomy hall. Over the stairs it says: Be bold, be bold, but not too bold. She climbs the stairs to a gallery, over which she finds the words: Be bold, be bold, but not too bold, lest your heart's blood should run cold.

through the woods to seek it. In the dark of the woods, she finds a high wall and a gate. Over the gate it says: Be bold. She enters, and finds a large, dilapidated mansion inside. Over the entrance it says: Be bold, be bold. She enters a gloomy hall. Over the stairs it says: Be bold, be bold, but not too bold. She climbs the stairs to a gallery, over which she finds the words: Be bold, be bold, but not too bold, lest your heart's blood should run cold.

The gallery is filled with the body parts of murdered women. She turns to flee, just as Mr. Fox comes in, dragging a new victim. She hides and watches, horrified, as the girl is chopped to bits. A severed hand flies close to her hiding place, a diamond ring on one finger. She takes the hand, creeps out the door, and runs home just as fast as she can. The next day there's a feast for the wedding couple, and Mr. Fox appears, looking as handsome as ever. He comments, "How pale you are, my love!"

"Last night I had a terrible dream," she says. "I dreamed I entered the woods and found a high wall and a gate. Over the gate it said: Be bold." She proceeds to tell him, and the assembled guests, just what she found inside.

"It is not so, nor it was not so, and God forbid it should be so," said Mr. Fox.

"But it is so, and it was so, and here's the hand and the ring I have to show!" She pulls the severed hand from her dress and flings it into her bridegroom's lap. The wedding guests rise up to cut Mr. Fox into a thousand pieces.

An Indian version of the tale has the daughter of respectable Brahmans courted by a man who is actually a tiger in disguise, anxious to procure a wife who can cook the curry dishes he loves. It is only when the girl is married and on her way to her husband's house that she learns the truth and finds herself wife and servant to a ferocious beast. She bears him a child, a tiger cub, before she finally makes her escape. As she leaves, she tears the cub in two and hangs it over the flames so that her husband will smell the roasting meat and think that she's still inside. It's an odd little tale, in which one feels sneaking sympathy for the tiger.

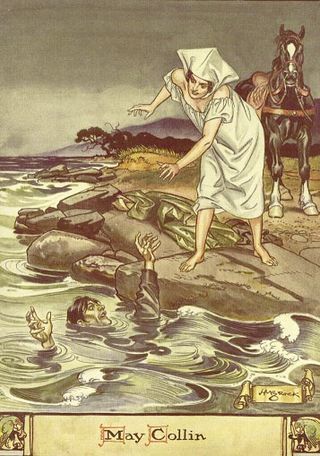

In various "demon lover" ballads found in the Celtic folk tradition, the Bluebeard figure is the devil in disguise, or else a treacherous elfin knight, or a murderous ghost, or a false lover with rape or robbery on his mind. In May Colvin, False Sir John rides off with a nobleman's daughter he's promised to marry -- but when they reach the sea, he orders the maiden to climb down from her horse, to take off her fine wedding clothes, and to hand over her  dowry. "Here I have drowned seven ladies," says he, "and you shall be the eighth." May begs him, for the sake of modesty, to turn as she disrobes. And then she promptly pushes him in the water to his death.

dowry. "Here I have drowned seven ladies," says he, "and you shall be the eighth." May begs him, for the sake of modesty, to turn as she disrobes. And then she promptly pushes him in the water to his death.

In a Scandinavian version of this ballad, a nobleman's daughter is courted by a handsome, honey-tongued, false suitor who promises to take her to the fair if she meets him in the woods. Her father will not let her go, her mother will not let her go, her brothers will not let her go, but her confessor gives permission, provided she keeps hold of her virtue. She finds her suitor in the woods busy at work digging a grave. He says the grave is for his dog; but she protests that it is too long. He says the grave is for his horse; she says it is too small. He tells her the grave is meant for her, unless she consents to lie with him. Eight maidens has he killed before, and she shall be the ninth. Now the choice is hers -- she must lose her virtue or her life. She chooses death, but advises her false suitor to remove his coat, lest her heart's blood spatter the fine cloth and ruin it. As he takes it off, she grabs the sword and strikes his head off "like a man." The head then speaks, instructing her to fetch a salve to heal the wound. Three times the girl refuses to do the bidding of a murderer. She takes the head, she takes his horse, she takes his dog, and rides back home -- but as she goes, she encounters her suitor's mother, his sisters, his brothers. Each time they ask, "Where is thy true love?" Each time she answers, "Lying in the grass, and bloody is his bridal bed." (In some versions, the entire family is made up of robbers and she must kill them too.) She then returns to her father's court, receiving a hero's welcome there. But in other "murderous lover" ballads, the heroines are not so lucky. Some meet with graves at the bottom of the sea, others in cold rivers, leaving ghosts behind to sing the sorrowful song of their tragic end.

Charles Perrault drew a number of elements from folk tales and ballads like these when he created the story of the urbane, murderous Bluebeard and his bloody chamber. Like the devil in the Italian tale Silvernose, Bluebeard is marked by a physical disfigurement -- the beard that "made him so frightfully ugly that all the women and girls run away from him." Like Mr. Fox, his wealth and his charm serve to overcome the natural suspicions  aroused by his mysterious past and the rumors of missing wives. Like the false suitors, he seduces his victims with courtly manners, presents, and flattery, all the while tenderly preparing the grave that will soon receive them. Perrault parts with these older tales, however, by apportioning blame to the maiden herself. He portrays her quite unsympathetically as a woman who marries solely from greed, and who calls Bluebeard's wrath upon herself with her act of disobedience. This is absent in the older tales, where curiosity and disobedience, combined with cunning and courage, are precisely what save the heroine from marriage to a monster, death at a robber's hands, or servitude to the devil. Perrault presents his Bluebeard as a well-mannered, even generous man who makes only one demand of his wife, marrying again and again as woman after woman betrays this trust.

aroused by his mysterious past and the rumors of missing wives. Like the false suitors, he seduces his victims with courtly manners, presents, and flattery, all the while tenderly preparing the grave that will soon receive them. Perrault parts with these older tales, however, by apportioning blame to the maiden herself. He portrays her quite unsympathetically as a woman who marries solely from greed, and who calls Bluebeard's wrath upon herself with her act of disobedience. This is absent in the older tales, where curiosity and disobedience, combined with cunning and courage, are precisely what save the heroine from marriage to a monster, death at a robber's hands, or servitude to the devil. Perrault presents his Bluebeard as a well-mannered, even generous man who makes only one demand of his wife, marrying again and again as woman after woman betrays this trust.

Only at the end of the tale, as the bridegroom stands revealed as a monster, does Perrault shift his sympathy to the bride, and Bluebeard is dispatched. Perrault ends the tale with a moral that stresses the heroine's transgressions and not her husband's, warning maidens that "curiosity, in spite of its appeal, often leads to deep regret." In a second moral, Perrault remarks that the story took place long ago; modern husbands are not such "jealous malcontents." Jealous malcontent? "Homicidal maniac" would be a better description! Again Perrault's words imply that despicable as Bluebeard's actions are, they are actions in response to the provocation of his wife's behavior.

Another departure from the older folk tales is that Bluebeard's wife, like the other fairy tale heroines in his Histoires ou contes du temps pass��, is a remarkably helpless creature. She herself does not outwit Bluebeard, she weeps and trembles and waits for her brothers -- unlike the folklore heroines who, even when calling brothers to their aid, have first proven themselves to be quick-witted, courageous, and pro-active. As Maria Tatar has pointed out (in her book The Classic Fairy Tales), "Perrault's story, by underscoring the heroine's kinship with certain literary, biblical, and mythical figures (most notably Psyche, Eve, and Pandora), gives us a tale that willfully undermines a robust folkloric tradition in which the heroine is a resourceful agent of her own salvation."

Another departure from the older folk tales is that Bluebeard's wife, like the other fairy tale heroines in his Histoires ou contes du temps pass��, is a remarkably helpless creature. She herself does not outwit Bluebeard, she weeps and trembles and waits for her brothers -- unlike the folklore heroines who, even when calling brothers to their aid, have first proven themselves to be quick-witted, courageous, and pro-active. As Maria Tatar has pointed out (in her book The Classic Fairy Tales), "Perrault's story, by underscoring the heroine's kinship with certain literary, biblical, and mythical figures (most notably Psyche, Eve, and Pandora), gives us a tale that willfully undermines a robust folkloric tradition in which the heroine is a resourceful agent of her own salvation."

This difference is particularly evident when we compare Perrault's passive heroine with those created by other fairy tale writers in the French salons -- the majority of them women writers, whose works were quite popular in their day. Perrault's niece, Marie-Jeanne L'H��ritier, was also the author of fairy tales; her story The Subtle Princess, published three years before Perrault's Histoires, drew on some of the same folklore motifs as Bluebeard. In L'H��ritier's tale, a king has three daughters, two of them foolish, the youngest one clever. When the king journeys away from home, he gives each of his girls a magical distaff made of glass that will shatter if the girl loses her virtue. (The tell-tale key in "murderous bridegroom" tales is often also made of glass.) The wicked prince of a neighboring kingdom enters the castle disguised as a beggar, then seduces each elder sister in turn -- marrying, bedding, and abandoning them. The youngest sister sees through his charms, whereupon he tries to take her by force. No wilting flower, she hoists an ax and threatens to chop him into pieces. The story goes on, with more attempts on the life and honor of the Subtle Princess, but she turns the tables on the wicked prince, kills him in a trap he's set for her, and goes on to marry his gentle, civil, kind-hearted younger brother. The Subtle Princess has no brothers of her own to come rushing to her aid, nor does she need them. She manages matters very well for herself, thank you.

In the following century, as women lost the social gains they'd made in the heady days of the salons, tales by L'H��ritier and other women (D'Aulnoy, Murat, Bernard, etc.) fell out of fashion, while those by Perrault -- with their simpler prose style, their moral endings, their meek and mild princesses -- continued to be reprinted and recounted year after year. As the 18th and 19th centuries progressed, re-tellings of Bluebeard increasingly emphasized the "sin" of disobedience as central to the story -- a subsequent version was titled Bluebeard, or The Effects of Female Curiosity. As fairy tales became an area of scholarly inquiry in the 19th and 20th centuries, folklorists pounced upon this theme in their analysis of the tale -- and took it one step further, suggesting that Bluebeard's wife's disobedience was sexual in nature, the blood-stained key symbolizing the act of infidelity. (Never mind the fact that there are no other men in the whole of Perrault's tale until those convenient brothers come thundering out of nowhere to save her.)

Psychologist Bruno Bettlheim was one of the critics who read Bluebeard as a tale of infidelity. In his flawed but influential book of the 1970s, The Uses of Enchantment, he pronounced Bluebeard "a cautionary tale which warns: Women, don't give in to your sexual curiosity; men, don't permit yourself to be carried away by your anger at being sexually betrayed. " But as novelist Lydia Millet has pointed out in her essay, "The Wife Killer" (published in Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Women Writers Explore The Favorite Fairy Tales): "Blue Beard wanted his new wife to find the corpses of his former wives. He wanted the new bride to discover their mutilated corpses; he wanted her disobedience. Otherwise, he wouldn't have given her the key to the forbidden closet; he wouldn't have left town on his so���called business trip; and he wouldn't have stashed the dead Mrs. Blue Beards in the closet in the first place. Transparently, this was a set-up."

Marina Warner, in her excellent fairy tale study From the Beast to the Blonde, suggests another way to read the tale: as an expression of young girls' fears about marriage. Perrault was writing at a time, and in a social class, when arranged marriages were commonplace, and divorce out of the question. A young woman could easily find herself married off to an old man without her consent -- or to a monster: a drunkard, a libertine, or an abusive spouse. Further, the mortality rate of women in childbirth was frighteningly high. Remarriage was commonplace for men who'd lost a wife (or wives) in this fashion, and ghosts from previous marriages hung over many a young bride's wedding. (Perrault and other writers in the fairy tale salons were firmly against arranged marriages, and this concern can be seen in the subtext of many fairy tales of the period.)

Another aspect of Bluebeard's story that we see increasingly emphasized in later re-tellings is xenophobia, with the brutal bridegroom portrayed as an Oriental. There is nothing in the text of Perrault's tale (except that extraordinary beard) to indicate that Bluebeard is anything but a wealthy, if eccentric, French nobleman -- yet illustrations to the story, from 18th century woodcuts to Victorian and Edwardian illustrations (by Edmund Dulac, Charles Robinson, Jennie Harbour, Margaret Tarrant and others) -- depict Bluebeard in Turkish garb, threatening his bride with a scimitar. It must be remembered that Arabian-Nights-style fairy tales were enormously popular in Europe from the 18th century onward, yet none of the other tales in Perrault's collection Histoires ou contes du temps pass�� were given this Oriental gloss as persistently as Bluebeard. Both horrible and sensual (all those wives!), Bluebeard is perhaps a more comfortable figure when he is the Other, the Outsider, the Foreigner, and not one of us. And yet, it's the fact that he is one of us -- the polite, well-mannered gentleman next door -- that makes the story so very chilling to this day. While tales like Beauty and the Beast serve to remind us that a monstrous visage can hide the heart of a truly good man, Bluebeard shows us the reverse: a man's fine facade might hide a monster.

Another aspect of Bluebeard's story that we see increasingly emphasized in later re-tellings is xenophobia, with the brutal bridegroom portrayed as an Oriental. There is nothing in the text of Perrault's tale (except that extraordinary beard) to indicate that Bluebeard is anything but a wealthy, if eccentric, French nobleman -- yet illustrations to the story, from 18th century woodcuts to Victorian and Edwardian illustrations (by Edmund Dulac, Charles Robinson, Jennie Harbour, Margaret Tarrant and others) -- depict Bluebeard in Turkish garb, threatening his bride with a scimitar. It must be remembered that Arabian-Nights-style fairy tales were enormously popular in Europe from the 18th century onward, yet none of the other tales in Perrault's collection Histoires ou contes du temps pass�� were given this Oriental gloss as persistently as Bluebeard. Both horrible and sensual (all those wives!), Bluebeard is perhaps a more comfortable figure when he is the Other, the Outsider, the Foreigner, and not one of us. And yet, it's the fact that he is one of us -- the polite, well-mannered gentleman next door -- that makes the story so very chilling to this day. While tales like Beauty and the Beast serve to remind us that a monstrous visage can hide the heart of a truly good man, Bluebeard shows us the reverse: a man's fine facade might hide a monster.

Bluebeard remained well known throughout Europe right up to the 20th century, in turn inspiring new tales, dramas, operettas, and countless pantomimes. William Makepeace Thackeray published a parody called Bluebeard's Ghost in 1843 which chronicles the further romantic adventures of Bluebeard's widow. Jacques Offenbach wrote a rather burlesque operetta titled Barbe-Bleue in 1866. In 1899, the Belgian symbolist Maurice Maeterlinck wrote a libretto entitled Ariane et Barbe-Bleue, set to music by Paul Dukas and performed in Paris in 1907. Maeterlinck's version, written with the aid of his lover, the singer Georgette Leblanc, combines Bluebeard with elements from the myth of Ariadne, Theseus and the Minotaur. In this sad, fatalistic version of the tale, Ariande, the last of Bluebeard's brides, attempts to rescue his previous wives and finds them bound by chains of their own making to Bluebeard's castle. The Seven Wives of Bluebeard, by Anatole France, published in 1903, re���tells Perrault's story from Bluebeard's point of view, portraying the man as a good-hearted (if somewhat simple-minded) nobleman whose reputation has been sullied by the duplicitous women he's married. Bela Bartok's opera Duke Bluebeard's Castle (1911), libretto by Bela Balasz, presents a brooding, philosophical Bluebeard, reflecting on the impossibility of lasting love between men and women.

Bluebeard remained well known throughout Europe right up to the 20th century, in turn inspiring new tales, dramas, operettas, and countless pantomimes. William Makepeace Thackeray published a parody called Bluebeard's Ghost in 1843 which chronicles the further romantic adventures of Bluebeard's widow. Jacques Offenbach wrote a rather burlesque operetta titled Barbe-Bleue in 1866. In 1899, the Belgian symbolist Maurice Maeterlinck wrote a libretto entitled Ariane et Barbe-Bleue, set to music by Paul Dukas and performed in Paris in 1907. Maeterlinck's version, written with the aid of his lover, the singer Georgette Leblanc, combines Bluebeard with elements from the myth of Ariadne, Theseus and the Minotaur. In this sad, fatalistic version of the tale, Ariande, the last of Bluebeard's brides, attempts to rescue his previous wives and finds them bound by chains of their own making to Bluebeard's castle. The Seven Wives of Bluebeard, by Anatole France, published in 1903, re���tells Perrault's story from Bluebeard's point of view, portraying the man as a good-hearted (if somewhat simple-minded) nobleman whose reputation has been sullied by the duplicitous women he's married. Bela Bartok's opera Duke Bluebeard's Castle (1911), libretto by Bela Balasz, presents a brooding, philosophical Bluebeard, reflecting on the impossibility of lasting love between men and women.

As fairy tales were relegated to the nursery in the 2oth century, Bluebeard was seldom included, for obvious reasons, in collections aimed at children. And yet the story did not disappear from popular culture; it moved from the printed page to film. As early as 1901, George M��li��s directed a silent film version titled Barbe Bleue, which manages, despite cinematic limitations, to be both comic and horrific. Other film treatments over the years include Bluebeard's Eighth Wife in 1938; Bluebeard in 1944; Richard Burton's Bluebeard in 1972, and Bluebeard's Castle, a film version of Bartok's opera, in 1992. Maria Tatar makes a case that Bluebeard's tale can be seen as a precursor of modern cinematic horror. "In Bluebeard, as in cinematic horror," she writes, "we have not only a killer who is propelled by psychotic rage, but also the abject victims of his serial murders, along with a 'final girl' (Bluebeard's wife), who either saves herself or arranges her own rescue. The 'terrible place' of horror, a dark, tomblike site that harbors grisly evidence of the killer's derangement, manifests itself as Bluebeard's castle."

As fairy tales were relegated to the nursery in the 2oth century, Bluebeard was seldom included, for obvious reasons, in collections aimed at children. And yet the story did not disappear from popular culture; it moved from the printed page to film. As early as 1901, George M��li��s directed a silent film version titled Barbe Bleue, which manages, despite cinematic limitations, to be both comic and horrific. Other film treatments over the years include Bluebeard's Eighth Wife in 1938; Bluebeard in 1944; Richard Burton's Bluebeard in 1972, and Bluebeard's Castle, a film version of Bartok's opera, in 1992. Maria Tatar makes a case that Bluebeard's tale can be seen as a precursor of modern cinematic horror. "In Bluebeard, as in cinematic horror," she writes, "we have not only a killer who is propelled by psychotic rage, but also the abject victims of his serial murders, along with a 'final girl' (Bluebeard's wife), who either saves herself or arranges her own rescue. The 'terrible place' of horror, a dark, tomblike site that harbors grisly evidence of the killer's derangement, manifests itself as Bluebeard's castle."

Marina Warner concurs. "Bluebeard," she notes, "has entered secular mythology alongside Cinderella and Snow White. But his story possesses a characteristic with particular affinity to the present day: seriality. Whereas the violence in the heroines' lives is considered suitable for children, the ogre has metamorphosed in popular culture for adults, into mass murderer, the kidnapper, the serial killer: a collector, as in John Fowles's novel The Collector, an obsessive, like Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. Though cruel women, human or fairy, dominate children's stories with their powers, the Bluebeard figure, as a generic type of male murderer, has gradually entered material requiring restricted ratings as well."

Marina Warner concurs. "Bluebeard," she notes, "has entered secular mythology alongside Cinderella and Snow White. But his story possesses a characteristic with particular affinity to the present day: seriality. Whereas the violence in the heroines' lives is considered suitable for children, the ogre has metamorphosed in popular culture for adults, into mass murderer, the kidnapper, the serial killer: a collector, as in John Fowles's novel The Collector, an obsessive, like Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. Though cruel women, human or fairy, dominate children's stories with their powers, the Bluebeard figure, as a generic type of male murderer, has gradually entered material requiring restricted ratings as well."

Indeed, for modern prose versions of Bluebeard we must go not to the children's fairy tale shelves, as we do for other stories by Perrault, but to the shelves of adult literature, where we find a number of interesting re-tellings. Foremost among them is Angela Carter's splendid story, "The Bloody Chamber," published in her short story collection of the same name, in which the author gives full reign to the tale's inherent sensuality, and expands the role of the bride's mother to wonderful effect. "Bluebeard's Daughter" by Sylvia Townsend Warner is a wry, sly, elegant tale about the daughter of Bluebeard's third wife, with her own abiding interest in the locked room of her father's castle. "Bones" by Francesca Lia Block (from The Rose and the Beast) transplants the fairy tale to modern Los Angeles, while Margaret Atwood's "Bluebeard's Egg" (from Bluebeard's Egg & Other Stories) is a contemporary, purely realist tale of marriage and infidelity, drawing its symbolism from both Bluebeard and Fitcher's Bird.

Gregory Frost's inventive novel Fitcher's Brides (a finalist for the World Fantasy Award) also draws liberally from both these tales, setting the story in upstate New York in the 19th century, at a time when religious fervor, doomsday cults, and experimental utopian communities were widespread. His Bluebeard figure is a calculating, controlling preacher named Reverend Fitcher. Bluebeard by Kurt Vonnegut and The Blue Diary by Alice Hoffman are contemporary novels that make use of the fairy tale's symbolism in intriguing ways. Vonnegut's book is the tale of an artist with a secret in his potato barn; Hoffman's novel is the chilling study of a seemingly perfect man with a mysterious past. Bluebeard/Robber Bridegroom poetry includes Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Bluebeard " (Renascence and Other Poems), Anne Sexton's "The Gold Key " (Transformations), Gwen Strauss's "Bluebeard" (Trail of Stones), and Neil Gaiman's "The White Rose" (Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears) -- plus an entire anthology of Bluebeard poems: Bluebeard's Wives, edited by Julie Boden and Zoe Brigley (Heaventree Press, 2007).

In her essay "The Wife Killer," Lydia Millet reflects on Bluebeard's potent, enduring allure. "Blue Beard retains his charm," she writes, "by being what most men and women feel they cannot be: an overt articulator of the private fantasy of egomania...he is the subject that takes itself for a god. He is omnipotent because he accepts no social compromise; he acts solely in the pursuit of his own satisfaction." She goes on to comment that "between an egotist with high expectations and a sociopath stretches only the fine thread of empathy and identification."

Bluebeard, Millet reminds us, is a story about illusion, transgression, and the dark side of carnal appetites. It cautions us to beware of strangers in the woods...and of gentleman in the front parlor.

Pictures: Artists are identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights to the art, text, and quotes above reserved by the artists and authors. Related reading: "Bluebeard's Third Wife" by Helena Bell (Strange Horizons), "Bluebeard's Final Girl, or the Revisionist" by Veronica Schanoes (JOMA), and "The White Road," a Mr. Fox poem by Neil Gaiman (JOMA). For more on Charles Perrault and other salon fairy tale writers of 17th century France: Once Upon a Time: a short history of adult fairy tales.

July 17, 2019

Wily and brave: the heroines of fairy tales

Continuing our discussion of stories, storytelling, and the fairy tale tradition, here's one more passage from Katherine Langrish's fine book Seven Miles of Steel Thistles: