Terri Windling's Blog, page 153

October 26, 2014

Tunes for a Monday Morning

This week, old and new folk music from Wales...

Above, "Cerdd y Gog Lwydlas" by Cass Meurig and Nial Cain, traditional folk musicians based in North Wales. The song comes from the first of their two albums, Deuawd and Oes i Oes. (Cass Meurig has also recorded with the bands Fernill and Pigyn Clust.)

Below, "Fi Wela" by Fernhill, one of the best known Welsh folk bands, filmed in concert in Brussels in 2010. The band's current line-up is Julie Murphy (vocals), Ceri Rhys Matthews (guitar and flute), Tomos Williams (trumpet), and Christine Cooper (fiddle and vocals). Their seventh album, Amser, was released earlier this year.

Above, "Breuddwyd y Wrach/Nyth y Gog" performed by Alaw, a trio composed of Oliver Wilson-Dickson (fiddle), Dylan Fowler (guitar), and Jamie Smith (accordion). Alaw has released a gorgeous CD of music they call "lovingly crafted arrangements of Welsh folk," titled Melody (2013).

Smith and Wilson-Dickson are also members of Jamie Smith's Mabon, playing original tunes by Smith that are deeply rooted in the Welsh and "interCeltic" tradition. Below is a pub performance of "The Hustler" by Smith, filmed for the BBC television programme Horo Gheallaidh during Celtic Connections 2011 in Glasgow, Scotland. (You can watch the rollicking end of Mabon's Celtic Connections set here.) The band has recorded four CDs, the latest of which is Windblown (2012).

Photos above: The Valley of Nant Gwynant, North Wales (from National Geographic) and the Pentre Ifan neolithic dolmen in Nevern, Pembrokeshire, Wales (from Wikicommons).

October 23, 2014

Telling the story

I see her walking

on a path through a pathless forest

or a maze, a labyrinth.

As she walks, she spins

and the fine threads fall behind her

following her way,

telling

where she is going,

telling

where she has gone.

Telling the story.

The line, the thread of voice,

the sentences saying the way.

(from "The Writer On, and At, Her Work)

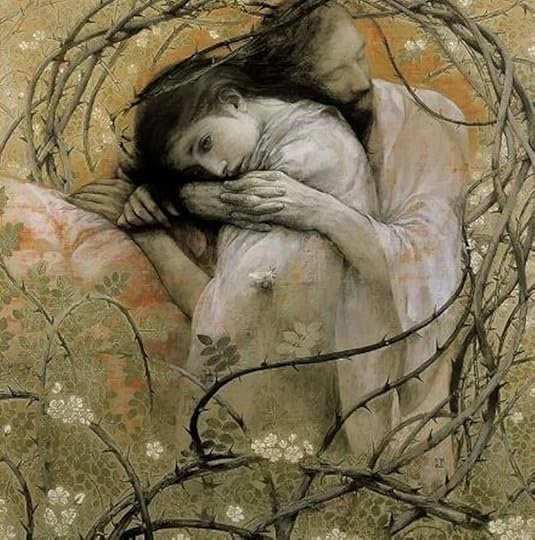

The gorgeous Mythic Art in this post is by Toshiyuki Enoki. Born in Tokyo in 1961, he was trained in traditional Japanese painting, lacquer painting, and western painting techniques. You can see more of his work here.

You can read the full poem, "The Writer On, and At, Her Work," in The Writer on Her Work, Vol. II edited by Janet Sternberg (where it was first published), and in Le Guin's collection The Wave in the Mind.

You can read the full poem, "The Writer On, and At, Her Work," in The Writer on Her Work, Vol. II edited by Janet Sternberg (where it was first published), and in Le Guin's collection The Wave in the Mind.

October 22, 2014

On the magic of cities

In response to a post last week, Raquel Somatra wrote:

"I lived on a mountain in North Carolina for six months with no car. The nearest grocery store was 1.5 miles away. Down the mountain, over several hills, through a dark tunnel, passed the old hotel that still has a sign that says 'now with color TV!'... People always think it must have been such a horrific time, to walk to the store once or twice a week and carry home groceries. But I loved it.....There is something about motion and pilgrimage that magically and deeply connects us to ourselves, to our insides, and to the earth. I think I got to know that landscape more in six months than locals who had lived their whole lives there. I knew where you could find pairs of bunnies in the spring, where the robins liked to feast along the ends of the roads, where wild roses grew, that tiny, wild pansies grew everywhere, fairy flowers hidden in the grasses. What else is there than connection to the land, ourselves, and each other? We must do this slowly -- I agree with Rebecca [Solnit]. Our minds move as slow as our feet, there can be no other way.

"p.s. I was thrilled to find that here in Brooklyn, I make a similar journey with groceries. There aren't mountains and pansies, but there are wondrous sights and people, a train, and much, much walking."

The post below comes out of thoughts prompted by Raquel's comment, and I want to begin by acknowledging that debt.

Despite the bucolic nature of this blog, written as it is from the English countryside, I think the words of the various writers quoted in these pages -- attesting to the importance of "land" and "place" -- are useful reminders to all of us, no matter where we live, that our aim should be to fully live wherever it is we find ourselves. As Mary Oliver tell us in beautiful poems that repeatedly enjoin us to pay attention, living a creative life is not just about the novels or paintings we produce (let alone manage to publish or sell), it's about living in a state of openness and attention -- beginning with the ground on which we stand: its flora, folklore, mythology, history, its weather patterns and daily rhythms, and the lives of those with whom we share it, human and nonhuman alike. This is as true, I believe, for city, town, and suburb dwellers as it is for me here, in rural Devon.

The "Urban Fantasy" field, back when it began in the 1980s and '90s -- when the term referred to works by writers like Charles de Lint, Emma Bull, Francesca Lia Block and Neil Gaiman, not paranormal romance and detective stories -- had at its heart a metaphorical search for wonder and natural (rather than supernatural) magic in city settings. These writers were asserting that one needn't travel to imaginary lands, the medieval past, or even to the countryside to find a magical (dare I say "spiritual"?) connection to place: it was available to all...yes, even at the heart of the beast: the big, noisy, crowded, diverse, dangerous, exciting modern city. (And remember that these writers began working in the '80s, when urban decline rendered many cities far less appealing than they are today.) Charles' Newford, Emma's Minneapolis, Francesca's Los Angeles, and Neil's London are cities in which the mythopoeic history of the land has re-asserted itself. The human protagonists of their books are those who hunger, in one way or another, to find that connection...and then to use it in concert with the unique gifts that cities alone can offer.

As Raquel says in her post script above, a city traversed on foot can be just as creatively inspiring as a woodland path or shoreline trail, at least for those open to its rhythms; for those who are paying attention. The following passage on urban walking comes from Rebecca Solnit's Wanderlust: A History of Walking, which devotes several chapters to the subject. To me, as a former New Yorker, this description of "city magic" rings absolutely true:

"There is a subtle state most urban walkers know, a sort of basking in solitude -- a dark solitude punctuated with encounters as the night sky is punctuated with stars -- one is altogether outside society, so solitude has a sensible geographical explanation, and there is a kind of communion with the nonhuman. In the city, one is alone because the world is made up of strangers, and to be a stranger surrounded by strangers, to walk along silently bearing one's secrets and imagining those of the people one passes, is among the starkest of luxuries. This uncharted identity with its illimitable possibilities is one of the distinctive qualities of urban living, a liberatory state for those who come to emancipate themselves from family and community expectation, to experiment with subculture and identity. It is an observer's state, cool, withdrawn, with senses sharpened, a good state for anybody who needs to reflect or create. In small doses, melancholy, alienation, and introspection are among life's most refined pleasures.

"Not long ago I heard the singer and poet Patti Smith answer a radio interviewer's questions about what she did to prepare for her performances onstage with, 'I would roam the streets for a few hours.' With that brief comment, she summoned up her own outlaw romanticism and the way such walking might toughen and sharpen the sensibility, wrap one in an isolation out of which might come songs fierce enough, words sharp enough, to break that musing silence. Probably roaming the streets didn't work so well in a lot of American cities, where the hotel was moated by a parking lot surrounded by six-lane roads without sidewalks, but she spoke as a New Yorker.

"Speaking as a Londoner, Virginia Woolf described anonymity as a fine and desirable thing, in her 1930 essay 'Street Haunting.' Daughter of the great alpinist Leslie Stephen, she had once declared to a friend, 'How could I think mountains and climbing romantic? Wasn't I brought up with alpenstocks in my nursery and a raised map of the Alps, showing every peak my father had climbed? Of course, London and the marshes are the places I like best.' Woolf wrote of the confining oppression of one's own identity, of the way the objects in one's home 'enforce the memories of our experience.' And so she set out to buy a pencil in a city where safety and propriety were no longer considerations for a no-longer-young woman on a winter evening [as they had been previously], and in recounting -- or inventing -- her journey, wrote one of the great essays on urban walking."

You can read Woolf's brilliant essay here.

Art above: Covers from my favorite magazine, The New Yorker, 1925-2014 (I'm so addicted to it that I still maintain a print subscription here in Devon), and the glorious New York paintings of Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986). I highly recommend Patti Smith's book Just Kids, a memoir of her youth in New York with Robert Mapplethorpe -- as well as works by all of the fine writers mentioned above. Previous posts related to this subject are here and here.

Art above: Covers from my favorite magazine, The New Yorker, 1925-2014 (I'm so addicted to it that I still maintain a print subscription here in Devon), and the glorious New York paintings of Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986). I highly recommend Patti Smith's book Just Kids, a memoir of her youth in New York with Robert Mapplethorpe -- as well as works by all of the fine writers mentioned above. Previous posts related to this subject are here and here.

A Morning Walk

"In order to create there must be a dynamic force, and what force is more potent than love?"

- Igor Stravinsky

October 21, 2014

Fantastic Women

Health issues have caused me to fall behind on a number of things in last few weeks, and as a result I've been remiss in letting you know about "Women Destroy Fantasy," a special issue of Lightspeed magazine, made possible by extra funds raised from Lightspeed's "Women Destroy Science Fiction" Kickstarter campaign. Lightspeed's managing editor, Wendy N. Wagner, explains the genesis of this special issue, dedicated to fantasy fiction, nonfiction, and illustration by women:

"Fantasy Magazine ran from 2005 until December 2011, at which point it merged with its sister-magazine, Lightspeed. Since that time, Lightspeed has been doing its best to uphold the fine tradition established by Fantasy, and we like to think it has kept the old girl alive by continuing to publish the same kind of quality fiction Fantasy fans had come to love and expect. Over at Lightspeed we were excited to publish our special issue, 'Women Destroy Science Fiction,' in June, but when our Kickstarter’s tremendous success unlocked all of our stretch goals -- thus offering us the chance to expand the destruction into fantasy and horror -- we knew that the 'Women Destroy Fantasy' special issue had to be a Fantasy Magazine special issue."

The "Women Destroy Fantasy" issue contains four original stories chosen by Guest Editor Cat Rambo (Cat was co-editor of Fantasy Magazine from 2007-2011), four classic fantasy stories chosen by me as Guest Reprint Editor, and seven works of non-fiction about women writers and artists in the fantasy field, chosen by Wendy Wagner...along with Author Spotlights and Reading Lists that are quite interesting in themselves.

You can read four of the stories online entirely for free: two of Cat's selections (by Kate Hall and T. Kingfisher), two of my selections (by Delia Sherman and Nalo Hopkinson), plus editorials (by Cat, Wendy, and me) and four works of nonfiction. Or you can plunk down $2.99 for the full digital edition (or $12.00 for a trade paperback edition) -- which is definitely worth the price, not only for the extra stories (originals by Julia August & H.E. Roulo, classics by Emma Bull & Carol Emshwiller) and the useful Reading Lists, but also for Sofia Samatar's particularly lovely essay, "The Frog Sister."

Do go have a look at what you can read online, including Kat Howard's fairy tale essay "The Princess and the Witch" (highly recommended), and an informative round-table on "Women in Fantasy Illustration" (which aspiring illustrators should not miss).

Best of all, you can listen to a podcast of Delia Sherman's "Miss Carstairs and the Merman," beautifully read by Gabrielle de Cuir, and with a witty introduction by Ellen Kushner (which, admittedly, made me blush). Delia discusses the writing of the story with Sandra O'Dell here.

There's some good-natured controversy about the project's name. "Women Destroy Science Fiction" was a natural choice for the SF version of this project since women have historically had a harder time in establishing themselves in the SF field, and complaints about women "destroying" the SF genre are at least as old as I am. Fantasy, however, has long been a women's preserve, as I argue in the editorial section...and yet it remains true (in the adult fantasy genre, less so in children's books and y.a.) that the best-sellers lists and prize lists still tend to be dominated by men, though notable gains by women (and writers of color) have certainly been made in the three decades I've been around. Although fantasy has been friendlier to women than some other fields (possibly due to its strong ties to children's literature), some of the overtly sexist incidents and assumptions I encountered during my early years in Publishing seem almost unbelievable today...and the fact that they seem so means we're making progress (all of us, men and women alike), even if we're not fully there yet.

This is, of course, not the first women's fantasy publication; if you're as old as me, you might remember the Sisters of Sorcery series published by DAW Books back in the '80s, among others. Whether there's still a need for such a publication is something that you, the readers, must each decide for yourselves. (There's bound to be a range of thoughts on the subject -- but if you express yours here, on the blog of this dyed-in-the-wool feminist, I beg you, be polite!)

As for my own opinion: when Lightspeed's Publisher/Editor-in-Chief, the gracious John Joseph Adams, wrote to ask if I'd be willing to select the reprints for this project, I found myself powerfully curious to see what form a women-writers-and-artists issue would take in 2014; and I'm always glad to see work by women celebrated, in this or any other field.

It should be noted that Cat and I worked in separate realms of endeavor and did not confer on our choices. If, as a result, "Women Destroy Fantasy" is shaped just a little less tightly than might have been possible by a single fiction editor (like Ellen Datlow's "Women Destroy Horror"), it also benefits by showing the work of two different generations of women editors: the places where our visions are similar, and where they contrast, is as interesting to me as the stories themselves, and shows some of the changes the field has undergone since I first joined it in the early 1980s.

There were, as is always the case with reprints, two classic stories I would have liked to have included that Lightspeed was unable to obtain, and so I must content myself with urging you to go and seek them out: "Transmutations" by Patricia A. McKillip (Xanadu II, Tor Books, 1994) and "The Little Dirty Girl" by Joanna Russ (The Armless Maiden, Tor Books, 1995). I only wish I could have chosen many more stories, for women have done such sterling work in fantasy that I want to honor them all. (I expect that Cat Rambo feels the same.)

There were, as is always the case with reprints, two classic stories I would have liked to have included that Lightspeed was unable to obtain, and so I must content myself with urging you to go and seek them out: "Transmutations" by Patricia A. McKillip (Xanadu II, Tor Books, 1994) and "The Little Dirty Girl" by Joanna Russ (The Armless Maiden, Tor Books, 1995). I only wish I could have chosen many more stories, for women have done such sterling work in fantasy that I want to honor them all. (I expect that Cat Rambo feels the same.)

Coming up: Look for the podcast of Nalo Hopkinson's brilliant tale, "The Glass Bottle Trick," which will come online this Friday. It, too, will be introduced by Ellen Kushner, who I expect to be in fine form, as always.

The art above is by K.A. King, Julie Bell, Rebecca Quay, Sandra Buskirk, Julie Dillon, and Tara Larsen Chang. It comes from the online editon of "Women Destroy Fantasy," reproduced here for promotional purposes only. All right reserved by the artists and Lightspeed/Fantasy Magazine.

The art above is by K.A. King, Julie Bell, Rebecca Quay, Sandra Buskirk, Julie Dillon, and Tara Larsen Chang. It comes from the online editon of "Women Destroy Fantasy," reproduced here for promotional purposes only. All right reserved by the artists and Lightspeed/Fantasy Magazine.

October 20, 2014

Planting words like seeds

Last week's discussion of time, technology, and living life at a more human pace inevitably leads back to a subject that many of us seem to be wrestling with these days: how to integrate communicate technologies into our lives without letting them take over.

One practice that helps me to get the balance right is to take periodic Offline Retreats. These are weeks in which I'm in the studio as usual (not sick in bed or on holiday) but keep the Internet shut down: no email, no blogging, no radio, no news. (If I had a mobile phone, I'd probably turn that off too.) It's a form of mental detox that serves to reset my work rhythms, helping me to retain the slow and steady focus that I need for the writing, painting, and editing I do.

I seem to have been wrestling with this issue for a long while. The following passage comes from a post I wrote over four years ago:

It's not surprising to me that so many of us in the Mythic Arts field have embraced the Internet so enthusiastically, for as a medium for the transmission of stories and ideas it's not only powerful and endlessly adaptable, but also remarkably accessible and democratic. I love the way that young artists can now find audiences for their work without being dependent (as we were in my generation) on the Gatekeepers of traditional media; I love the blogs that allow writers to communicate with their readers beyond the confines of a novel's pages; and I love watching Mythic Artists use modern mediums to keep ancient tales alive.

Overall, I value the Internet, and yet I also know that I have to put boundaries around my use of it. (Dani Shapiro is not wrong when she jokes that the Internet is crack cocaine for writers.) I spend enough time as it is behind these plastic computer keys...and although I do so in order to weave tales of earth and sky and wind and rain and animals and spirits on the printed page, I want my tales to reflect my experience of the natural world, not replace that experience. As much as I love wandering the woods of myth, as much as I love conjuring those woods in stories of my own, the real woods lie beyond the front door and that's where I must always go first. For my art's sake. For my soul's sake.

And so must many of us, I think; if not the woods, then the city streets, or the campus, or the road, or the porch where family and neighbors linger...whatever place you go, whatever air you breathe, to feed mind, heart, and imagination.

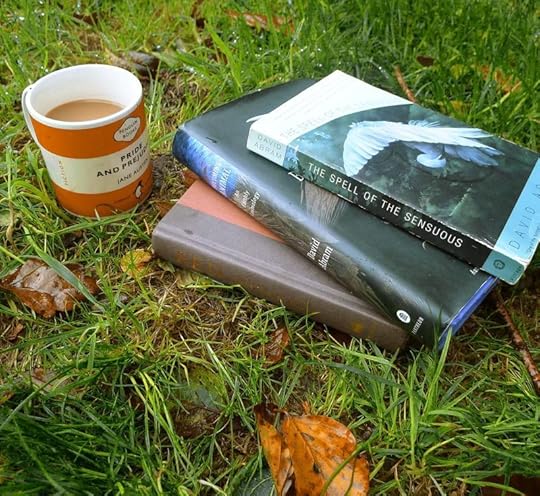

In his luminous book The Spell of the Sensuous, David Abram discusses the many ways that moving from an oral culture to a print culture has impacted, and even impoverished, our experience of the world around us. (His thesis is a nuanced and persuasive one; I won't try to encapsulate it here, but recommend reading it in full.) As a folklorist, I'm fascinated by David's argument; while as a writer, I find it more challenging, for I dearly love books and the printed page, and I'm fascinating by the still-evolving genre of blogging as an art form. Yet David isn't attempting to suggest that we turn our backs on literacy now, but rather that we understand its cultural, spiritual, and environmental implications. Addressing his fellow writers, he says:

"For those of us who care for an earth not encompassed by machines, a world of textures, tastes, and sounds other than those that we have engineered, there can be no question of simply abandoning literacy, of turning away from all writing. Our task, rather, is that of taking up the written word, with all its potency, and patiently, carefully, writing language back into the land.

"Our craft is that of releasing the budded, earthly intelligence of our words, freeing them to respond to the speech of things themselves -- the the green uttering-forth of leaves from the spring branches. It is the practice of spinning stories that have a rhythm and lilt of the local soundscape, tales for the tongue, tales that want to be told, again and again, sliding off the digital screen and slipping off the lettered page to inhabit the coastal forests, those desert canyons, those whispering grasslands and valley and swamps. Finding phrases that place us in contact with the trembling neck-muscles of a deer holding its antlers high as it swims toward the mainland, or with the ant dragging a scavenged rice-grain through the grasses. Planting words, like seeds, under rocks and fallen logs -- letting language take root, once again, in the earthen silence of shadow and bone and leaf."

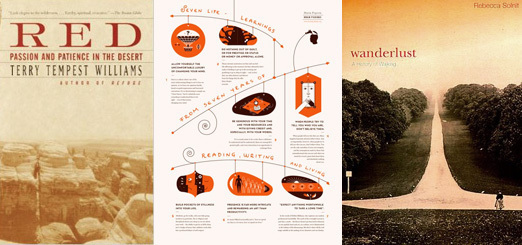

Likewise, Terry Tempest Williams tell us in her essay collection Red:

"I want to write my way from the margins to the center. I want to speak the language of the grasses, rooted yet soft and supple in the presence of wind before a storm. I want to write in the form of migrating geese like an arrow pointing south toward a direction of safety. I want to keep my words wild so that even if the land and everything we hold dear is destroyed by shortsightedness and greed, there is a record of participation by those who saw what was coming. Listen. Below us. Above us. Inside us. Come. This is all there is."

What does all this mean for me, personally? First, that I try to do as these writers suggest when I sit to write or paint myself: to bring the physical world into my work, whether moorland or desert or city street. And second, that I strive to live in such a way that writing and art springs out of my life; it doesn't become my life.

And that means turning off the computer every now and again, putting down my paint brushes and pens, lacing up my boots, whistling for the dog, and going out my front door. It means that I try to never forget that “community” begins at home: with my family, with my village, with the inter-species community of rooted and winged and four-legged beings among whom I live on this green hillside. And from this place, with my tap roots deep in the soil below, my “community” can then slowly spread: via books and paintings, via letters in the post, via pixels on the computer screen...to you, dear Reader.

October 19, 2014

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today: songs and videos on the theme of childhood, inspired by this passage from George Monbiot's Feral, which I quoted in Friday's post: "Of all the world's creatures, perhaps those in greatest need of rewilding are our children. The collapse of children's engagement with nature has been even faster than the collapse of the natural world. In the turning of one generation, the outdoor life in which many of us were immersed has gone....So many fences are raised to shut us out that eventually they shut us in."

Above: "Brother" by Mighty Oaks, an alt-folk trio based in Berlin, Germany, consisting of Ian Hooper (US), Craig Saunders (UK), and Claudio Donzelli (Italy). Like The Avett Brothers in America and Stornoway in England, the Mighty Oaks create songs rooted in pop, country, and folk music, distinguished by skillful vocal harmonies. The song comes from their second album, Howl (2014).

Below: "Down by the River" by Milky Chance, from Kassel, Germany. Created by Clemens Rehbein (vocalist) and Philipp Dausch, Milky Chance's music blends a range of influences, including folk, rock, reggae, jazz, and electronica. The song comes from their debut album, Sadnecessary (2013).

Next, two songs that have been Monday Tunes in the past, but that are worth re-visiting in this context....

Above: "Featherstones" by The Paper Kites, an alt-folk band from Melbourne, Australia. The song comes from their third EP, Woodland (2011).

Below: "Pieces of String" by singer-songwriter Alela Diane, based in Portland, Oregon (US). The song comes from her second album, The Pirate's Gospel (2006).

And last, below, a poignant song looking back at childhood:

"Once When I was Little" (accoustic version) by singer-songwriter James Morrison, from his second album, Songs for You, Truths for Me (2008). Born and raised in Rugby, Warwickshire (UK), Morrison is now based in Derby. I really love this song.

Oh heck, I'm going to throw in one more:

"Horsehead Bay" by Mighty Oaks, a beautiful song looking back at the lands of one's youth -- which for these lads is Washington State; Somerset, England; and Pesaro, Italy. The performance was filmed by Noir TV in Germany.

The illustrations above are "Children of the Forest" by Elsa Beskow (1874-1953) and "She Kissed the Bear on the Nose" by John Bauer (1882-1918). Both artists are from Sweden.

October 16, 2014

Gentle Readers,

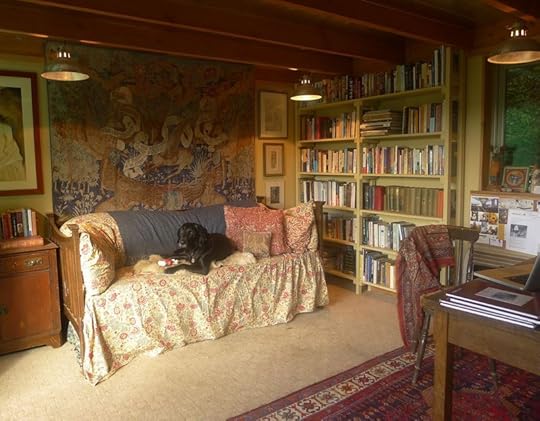

I am still a bit under the weather. The hound and I will be back in the studio on Monday.

In the meantime, some reading recommendations:

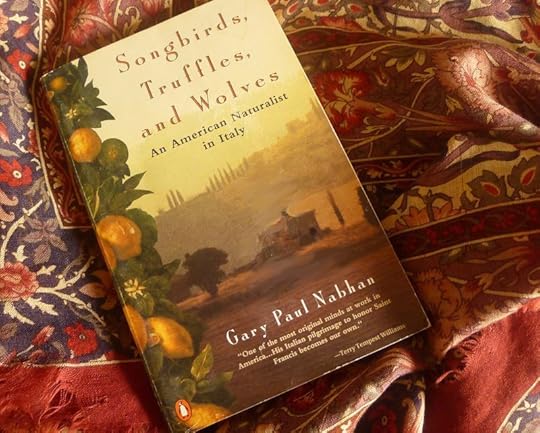

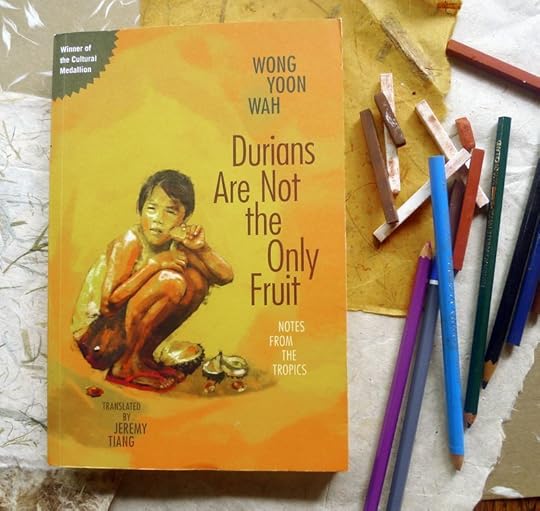

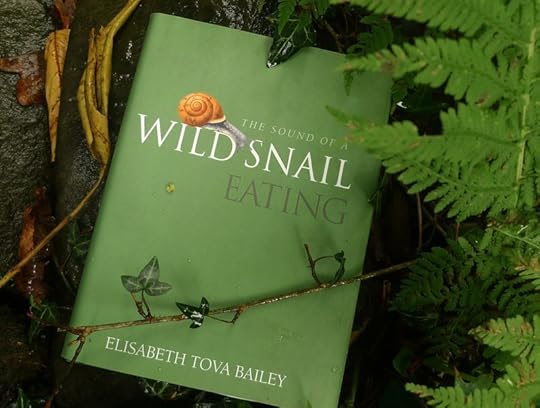

Reviews of the two lovely illustrated books below are forthcoming (as health permits).

Have a good weekend.

See the picture captions (by running your cursor over the photographs) for quotes from the first four books.

See the picture captions (by running your cursor over the photographs) for quotes from the first four books.

On time, technology, and a celebration of slowness

From Rebecca Solnit's Wanderlust: A History of Walking (2001):

"[My friend] Sono's truck had been stolen from her West Oakland studio, and she told me that although everyone responded to it as a disaster, she wasn't all that sorry it was gone, or in a hurry to replace it. There was a joy, she said, to finding that her body was adequate to get her where she was going, and it was a gift to develop a more tangible, concrete relationship to her neighborhood and its residents. We talked about the more stately pace of time one has on foot and on public transportation, where things must be planned and scheduled beforehand, rather than rushed through at the last minute, and about the sense of place that can only be gained on foot. Many people nowadays live in a series of interiors -- home, car, gym, office, shops -- disconnected from each other. On foot everything stays connected, for while walking one occupies the spaces between those interiors in the same way one occupies those interiors. One lives in the whole world rather than interiors built up against it....

"I had told Sono about an ad I found in the Los Angeles Times a few months ago that I'd been thinking about ever since. It was for a CD-ROM encyclopedia, and the text that occupied a whole page read, 'You used to walk across town in the pouring rain to use our encyclopedias. We're pretty confident that we can get your kid to click and drag.' I think it was the kid's walk in the rain that constituted the real education, at least of the senses and the imagination. Perhaps the child with the CD-ROM encyclopedia will stray from the task at hand, but wandering in a book or a computer takes place within more constricted and less sensual parameters. It's the unpredictable incidents between official events that add up to a life, the incalculable that gives it value. Both rural and urban walking have for two centuries been prime ways of exploring the unpredictable and incalculable, but now they are under assault on many fronts.

"The multiplication of technologies in the name of efficiency is actually eradicating free time by making it possible to maximize the time and place for production and minimize the unstructured travel time between. New time-saving technologies make most workers more productive, not more free, in a world that seems to be accelerating around them. Too, the rhetoric of efficiency around these technologies suggests that what cannot be quantified cannot be valued -- that that vast array of pleasures which fall into the category of doing nothing in particular, of woolgathering, cloud-gazing, wandering, window-shopping, are nothing but voids to be filled by something more definite, more productive, or faster paced....

"The indeterminacy of a ramble, on which much may be discovered, is being replaced by the determinate shortest distance to be transversed with all possible speed, as well as by electronic transmissions that make real travel less necessary. As a member of the self-employed whose time saved by technology can be lavished on daydreams and meanders, I know these things have their uses, and use them -- a truck, a computer, a modem -- myself, but I fear their false urgency, their call to speed, their insistence that travel is less important than arrival. I like walking because it is slow, and I suspect that the mind, like the feet, works at about three miles an hour. If this is so, then modern life is moving faster than the speed of thought, or thoughtfulness."

Solnit returned to the subject of time in an essay for the London Review of Books last year:

"Nearly everyone I know feels that some quality of concentration they once possessed has been destroyed. Reading books has become hard; the mind keeps wanting to shift from whatever it is paying attention to to pay attention to something else. A restlessness has seized hold of many of us, a sense that we should be doing something else, no matter what we are doing, or doing at least two things at once, or going to check some other medium. It’s an anxiety about keeping up, about not being left out or getting behind. (Maybe it was a landmark when Paris Hilton answered her mobile phone while having sex while being videotaped a decade ago.)

"The older people I know are less affected because they don’t partake so much of new media, or because their habits of mind and time are entrenched. The really young swim like fish through the new media and hardly seem to know that life was ever different. But those of us in the middle feel a sense of loss. I think it is for a quality of time we no longer have, and that is hard to name and harder to imagine reclaiming. My time does not come in large, focused blocks, but in fragments and shards. The fault is my own, arguably, but it’s yours too – it’s the fault of everyone I know who rarely finds herself or himself with uninterrupted hours. We’re shattered. We’re breaking up.

"It’s hard, now, to be with someone else wholly, uninterruptedly, and it’s hard to be truly alone. The fine art of doing nothing in particular, also known as thinking, or musing, or introspection, or simply moments of being, was part of what happened when you walked from here to there alone, or stared out the train window, or contemplated the road, but the new technologies have flooded those open spaces."

"I wonder," she muses later in the piece, "if there will be a revolt against the quality of time the new technologies have brought us, as well as the corporations in charge of those technologies. Or perhaps there already has been, in a small, quiet way. The real point about the slow food movement was often missed. It wasn’t food. It was about doing something from scratch, with pleasure, all the way through, in the old methodical way we used to do things. That didn’t merely produce better food; it produced a better relationship to materials, processes and labour, notably your own, before the spoon reached your mouth. It produced pleasure in production as well as consumption. It made whole what is broken."

(I highly recommend reading Solnit's essay, "In the Day of the Postman," in full.)

In "7 Things I Learned in 7 Years of Reading, Writing, and Living," Maria Popova notes:

"Presence is far more intricate and rewarding an art than productivity. Ours is a culture that measures our worth as human beings by our efficiency, our earnings, our ability to perform this or that. The cult of productivity has its place, but worshipping at its altar daily robs us of the very capacity for joy and wonder that makes life worth living — for, as Annie Dillard memorably put it, 'how we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.' "

(This is another article I highly recommend reading in full.)

Terry Tempest Williams, too, has questioned our culture's emphasis on speed, ease, productivity, and consumption. In her beautiful essay "Ode to Slowness" (Red, 2001), she reflects on her transition from the urban pace of Salt Lake City to the quiet rhythms of a village in the Utah desert, using language that echoes my own transition from Boston and New York City to the Arizona desert and rural England:

"My husband and I were comfortable in our urban routine," she writes," but one night over dinner her said, 'What if we are only living half-lives? What if there is something more?'

"We wanted more.

"We wanted less.

"We wanted more time, fewer distractions. We wanted more time together, time to write, to breathe, to be more conscious with our lives. We wanted to be closer to wild places where we could walk and witness the seasonal changes, even the changing constellations. And so we banked on the idea of a simpler life away from the city near the slickrock country we love. What we would lose in income, we would gain in sanity."

Time, she discovered, (as I, too, discovered), moves differently outside of the city.

"I am not so easily seduced by speed as I once was," says Williams. "I find that I have lost the desire to move that quickly in the world. To see how much I can get done in a day does not impress me any more. I don't think it's about getting older. It feels more like honoring the gravity in my own body in relationship to place. Survival. A rattlesnake coils; its tail shakes; the emptiness of the desert is evoked.

"I want my life to be a celebration of s l o w n e s s ."

As do I. Oh, as do I.

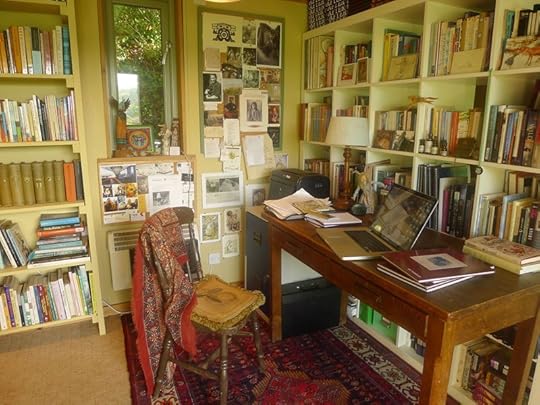

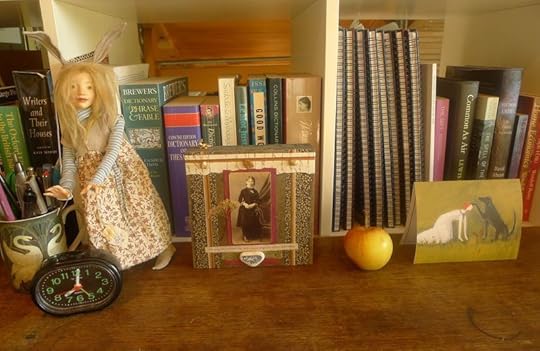

The Bunny Girl on my desk (and in the grass) is by Wendy Froud, the collage art by Lynn Hardaker, and the "woman with dog" card by Jeanie Tomanek. They were gifts, all of them, and much treasured.

The Bunny Girl on my desk (and in the grass) is by Wendy Froud, the collage art by Lynn Hardaker, and the "woman with dog" card by Jeanie Tomanek. They were gifts, all of them, and much treasured.

October 14, 2014

What comes from silence

How to be a Poet (to remind myself)

by Wendell Berry

Make a place to sit down.

Sit down. Be quiet.

Sit down. Be quiet.

You must depend upon

affection, reading, knowledge,

skill-more of each

than you have-inspiration

work, growing older, patience,

for patience joins time

to eternity...

Breathe with unconditional breath

the unconditioned air.

Shun electric wire.

Communicate slowly. Live  a three-dimensional life;

a three-dimensional life;

stay away from screens.

Stay away from anything

that obscures the place it is in.

There are no unsacred places;

there are only sacred places

and desecrated places.

Accept what comes from silence.

Make the best you can of it.

Make the best you can of it.

Of the little words that come

out of the silence, like prayers

prayed back to the one who prays,

make a poem that does not disturb

the silence from which it came.

"How to Be a Poet" is from Given: Poems by Wendell Berry (Counterpoint, 2006); all rights reserved by the author. The drawings above are by Honor Appleton, Harrison Weir, and H.J. Ford,

"How to Be a Poet" is from Given: Poems by Wendell Berry (Counterpoint, 2006); all rights reserved by the author. The drawings above are by Honor Appleton, Harrison Weir, and H.J. Ford,

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers