Terri Windling's Blog, page 149

December 19, 2014

All we have...

"We are animal in our blood and in our skin. We were not born for pavements and escalators but for thunder and mud. More. We are animal not only in body but in spirit. Our minds are the minds of wild animals. Artists, who remember their wildness better than most, are animal artists, lifting their heads to sniff a quick wild scent in the air, and they know it unmistakably, they know the tug of wildness to be followed through your life is buckled by that strange and absolute obedience."

- Jay Giffiths (Wild: An Elemental Journey)

"All we have, it seems to me, is the beauty of art and nature and life, and the love which that beauty inspires." - Edward Abbey ( The Journey Home)

And that's everything.

December 18, 2014

Speaking of animals....

Who among us hasn’t wondered what it would be like to see the world through an animal’s eyes? To lope across the landscape as a wolf, fly above the trees on the wings of a crow, leap through the waves with a porpoise’s grace, snooze winter away in a bear cub’s den?

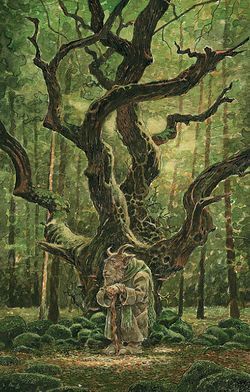

Many books for youn  g readers explore the common childhood desire to run wild with the animals, from Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book to Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are -- but even better than dancing with the wolves would be to have the power to become an animal oneself. T. H. White tapped into this fantasy in his Arthurian classic, The Once and Future King. Here, Merlin educates the young Arthur by transforming him into a badger, a fish, an owl, an ant, etc., and Arthur must learn to live as they live, gaining knowledge, even wisdom, in the process. This isn’t a standard part of the Arthur myth, but White hasn’t made it up from whole cloth either. He’s drawn on a worldwide body of tales even older than Arthur mythos: tales of shape-shifting, therianthropy (animal-human metamorphosis) and shamanic initiation. Animal-human

g readers explore the common childhood desire to run wild with the animals, from Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book to Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are -- but even better than dancing with the wolves would be to have the power to become an animal oneself. T. H. White tapped into this fantasy in his Arthurian classic, The Once and Future King. Here, Merlin educates the young Arthur by transforming him into a badger, a fish, an owl, an ant, etc., and Arthur must learn to live as they live, gaining knowledge, even wisdom, in the process. This isn’t a standard part of the Arthur myth, but White hasn’t made it up from whole cloth either. He’s drawn on a worldwide body of tales even older than Arthur mythos: tales of shape-shifting, therianthropy (animal-human metamorphosis) and shamanic initiation. Animal-human  transformation stories can be found in sacred texts, myths, epic romances, and folk tales all around the globe, divided into three (overlapping) types: First, there are stories of immortal and mortal beings who shape-shift voluntarily, altering their physical form at will for purposes both beneficent and malign. The second kind of story involves characters (usually human) who have their shape changed voluntarily—generally as the result of a curse, an enchantment, or a punishment from the gods. The third type of story concerns supernatural beings who are a blend of human and animal; they have the physical and mental attributes of both species and belong fully to neither world. Animal bride and bridegroom stories (in which a human man or woman is married to an animal, or an animal-like monster) can fall under any of these three categories: the animal spouse might be a shape-shifter, or an ordinary mortal under a curse, or a creature of mixed blood from the animal, human, and/or divine realms.

transformation stories can be found in sacred texts, myths, epic romances, and folk tales all around the globe, divided into three (overlapping) types: First, there are stories of immortal and mortal beings who shape-shift voluntarily, altering their physical form at will for purposes both beneficent and malign. The second kind of story involves characters (usually human) who have their shape changed voluntarily—generally as the result of a curse, an enchantment, or a punishment from the gods. The third type of story concerns supernatural beings who are a blend of human and animal; they have the physical and mental attributes of both species and belong fully to neither world. Animal bride and bridegroom stories (in which a human man or woman is married to an animal, or an animal-like monster) can fall under any of these three categories: the animal spouse might be a shape-shifter, or an ordinary mortal under a curse, or a creature of mixed blood from the animal, human, and/or divine realms.

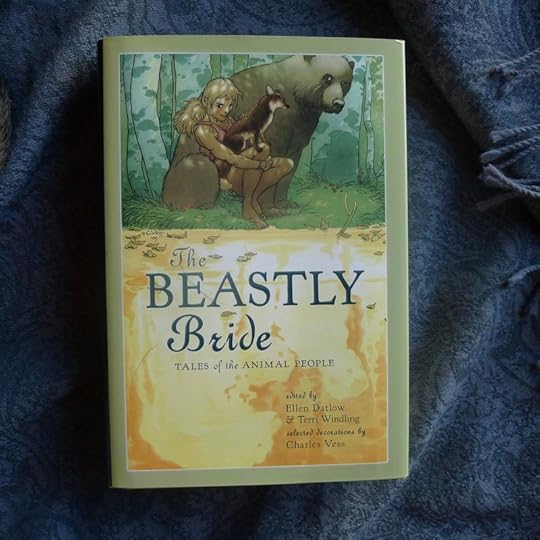

The Beastly Bride is an anthology of original stories and poems (for teen readers and up) inspired by animal transformation legends from around the world, retold and reimagined by Christopher Barzak, Peter Beagle, Jeffrey Ford, Gregory Frost, Hiromi Gotto, Ellen Kushner, Tanith Lee, Lucius Shepard, Delia Sherman, Midori Snyder, Jane Yolen and many other fine writers. The charming cover art and interior decorations are by the always-wonderful Charles Vess.

"Animal" is defined rather loosely here, for in addition to stories of bears, cats, rats, deer, and other four-footed creatures there are also birds, fish, seals, a fire salamander, a yeti’s child...and yes, a beastly bride or two.

"Any glimpse into the life of an animal quickens our own and makes it so much the larger and better in every way." - John Muir

So true.

This volume was published as the fourth installment of our Mythic Fiction anthology series for Young Adult readers, each book dedicated to a different aspect of world mythology: The Green Man: Tales of the Mythic Forest, The Faery Reel: Tales of the Twilight Realm, The Coyote Road: Trickster Tales, and The Beastly Bride: Tales of the Animal People. It's available in hardcover and ebook format from Viking Children's Books.

This volume was published as the fourth installment of our Mythic Fiction anthology series for Young Adult readers, each book dedicated to a different aspect of world mythology: The Green Man: Tales of the Mythic Forest, The Faery Reel: Tales of the Twilight Realm, The Coyote Road: Trickster Tales, and The Beastly Bride: Tales of the Animal People. It's available in hardcover and ebook format from Viking Children's Books.

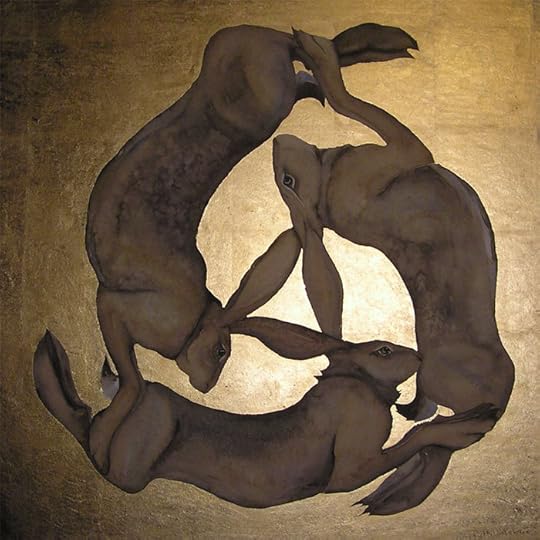

"Into the Woods" series, 34: The Folklore of Rabbits & Hares

The symbol of our village is three hares in a circle, their interlinked ears forming a perfect triangle -- an imge found in roof boss carvings in seventeen Devon churches, including ours. Known locally as the Tinner Rabbits, the design was widely believed to be based on an old alchemical symbol for tin, representing the historic  importance of tin mining on Dartmoor nearby -- until a group of local artists and historians created the Three Hares Project to investigate the symbol’s history. To their surprise, they discovered that the design’s famous tin association is actually a dubious one, deriving from a misunderstanding of an alchemical illustration published in the early 17th century. In fact, the symbol is much older and farther ranging than early folklorists suspected. It is, the Three Hares Project reports, "an extraordinary and ancient archetype, stretching across diverse religions and cultures, many centuries and many thousands of miles. It is part of the shared medieval heritage of Europe and Asia (Buddhism, Islam, Christianity and Judaism) yet still inspires creative work among contemporary artists."

importance of tin mining on Dartmoor nearby -- until a group of local artists and historians created the Three Hares Project to investigate the symbol’s history. To their surprise, they discovered that the design’s famous tin association is actually a dubious one, deriving from a misunderstanding of an alchemical illustration published in the early 17th century. In fact, the symbol is much older and farther ranging than early folklorists suspected. It is, the Three Hares Project reports, "an extraordinary and ancient archetype, stretching across diverse religions and cultures, many centuries and many thousands of miles. It is part of the shared medieval heritage of Europe and Asia (Buddhism, Islam, Christianity and Judaism) yet still inspires creative work among contemporary artists."

The earliest known examples of the design can be found in Buddhist cave temples in China (581-618 CE); from there it spread all along the Silk Road, through the Middle East, through Hungary and Poland to Germany, Switzerland, and the British Isles. Though now  associated with the Holy Trinity in Christian iconography, the original, pre-Christian meaning of the Three Hares design has yet to be discovered. We can glimpse possible interpretations, however, by examing the wealth of world mythology and folklore involving rabbits and hares. In many mythic traditions, these animals were archetypal symbols of femininity, associated with the lunar cycle, fertility, longevity, and rebirth. But if we dig a little deeper into their stories we find that they are also contradictory, paradoxical creatures: symbols of both cleverness and foolishness, of femininity and androgyny, of cowardice and courage, of rampant sexuality and virginal purity. In some lands, Hare is the messenger of the Great Goddess, moving by moonlight between the human world and the realm of the gods; in other lands he is a god himself, wily deceiver and sacred world creator rolled into one.

associated with the Holy Trinity in Christian iconography, the original, pre-Christian meaning of the Three Hares design has yet to be discovered. We can glimpse possible interpretations, however, by examing the wealth of world mythology and folklore involving rabbits and hares. In many mythic traditions, these animals were archetypal symbols of femininity, associated with the lunar cycle, fertility, longevity, and rebirth. But if we dig a little deeper into their stories we find that they are also contradictory, paradoxical creatures: symbols of both cleverness and foolishness, of femininity and androgyny, of cowardice and courage, of rampant sexuality and virginal purity. In some lands, Hare is the messenger of the Great Goddess, moving by moonlight between the human world and the realm of the gods; in other lands he is a god himself, wily deceiver and sacred world creator rolled into one.

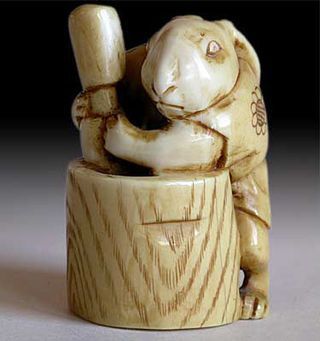

The association of rabbits, hares, and the moon can be found in numerous cultures the world over -- ranging from Japan to Mexico, from Indonesia to the British Isles. Whereas in Western folklore we refer to the "Man in the Moon," the "Hare (or Rabbit) in the Moon" is a more familiar image in other societies. In China, for example, the Hare in the Moon is depicted with a mortar and pestle in which he mixes the elixir of immortality; he is the messenger of a female moon deity and the guardian of all wild animals. In Chinese  folklore, female hares conceive through the touch of the full moon's light (without the need of impregnation by the male), or by crossing water by moonlight, or licking moonlight from a male hare’s fur. Figures of hares or white rabbits are commonly found at Chinese Moon Festivals, where they represent longevity, fertility, and the feminine power of yin.

folklore, female hares conceive through the touch of the full moon's light (without the need of impregnation by the male), or by crossing water by moonlight, or licking moonlight from a male hare’s fur. Figures of hares or white rabbits are commonly found at Chinese Moon Festivals, where they represent longevity, fertility, and the feminine power of yin.

In Egyptian myth, hares were also closely associated with the cycles of the moon, which was viewed as masculine when waxing and feminine when waning. Hares were likewise believed to be androgynous, shifting back and forth between the genders -- not only in ancient Egypt but also in European folklore right up to the 18th century. A hare-headed god and goddess can be seen on the Egyptian temple walls of Dendera, where the female is believed to be the goddess Unut (or Wenet), while the male is most likely a representation of Osiris (also called Wepuat or Un-nefer), who was sacrificed to the Nile annually in the form of a hare.

In Greco-Roman myth, the hare represented romantic love, lust, abundance, and fercundity. Pliny the Elder recommended the meat of the hare as a cure for sterility, and wrote that a meal of hare enhanced sexual attraction for a period of nine days. Hares were associated with the Artemis, goddess of wild places and the hunt, and newborn hares were not to be killed but left to her protection. Rabbits were sacred to Aphrodite, the  goddess of love, beauty, and marriage—for rabbits had “the gift of Aphrodite” (fertility) in great abundance. In Greece, the gift of a rabbit was a common love token from a man to his male or female lover. In Rome, the gift of a rabbit was intended to help a barren wife conceive. Carvings of rabbits eating grapes and figs appear on both Greek and Roman tombs, where they symbolize the transformative cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

goddess of love, beauty, and marriage—for rabbits had “the gift of Aphrodite” (fertility) in great abundance. In Greece, the gift of a rabbit was a common love token from a man to his male or female lover. In Rome, the gift of a rabbit was intended to help a barren wife conceive. Carvings of rabbits eating grapes and figs appear on both Greek and Roman tombs, where they symbolize the transformative cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

In Teutonic myth, the earth and sky goddess Holda, leader of the Wild Hunt, was followed by a procession of hares bearing torches. Although she descended into a witch-like figure and boogeyman of children’s tales, she was once revered as a beautiful, powerful goddess in charge of weather phenomena. Freyja, the headstrong Norse goddess of love, sensuality, and women’s mysteries, was also served by hare attendants. She traveled with a sacred hare and boar in a chariot drawn by cats. Kaltes, the shape-shifting moon goddess of western Siberia, liked to roam the hills in the form of a hare, and was sometimes pictured in human shape wearing a headdress with hare’s ears. Eostre, the goddess of the moon, fertility, and spring in Anglo–Saxon myth, was often depicted with a hare’s head or ears, and with a white hare standing in attendance. This magical white hare laid brightly colored eggs which were given out to children during spring fertility festivals -- an ancient tradition that survives in the form of the Easter Bunny today.

Eostre, the Celtic version of Ostara, was a goddess also associated with the moon, and with mythic stories of death, redemption, and resurrection during the turning of winter to spring. Eostre, too, was a shape-shifter, taking the shape of a hare at each full moon; all hares were sacred to her, and acted as her messengers. Cesaer recorded that rabbits and hares were taboo foods to the Celtic tribes. ((I should mention that our understanding of the Ostara/Eostre myth is a controversial one, with mythologists divided between those who believe she was, and was not, a major figure in the British Isles.) In Ireland, it was said that eating a hare  was like eating one’s own grandmother -- perhaps due to the sacred connection between hares and various goddesses, warrior queens, and female faeries, or else due to the belief that old "wise women" could shape-shift into hares by moonlight. The Celts used rabbits and hares for divination and other shamanic practices by studying the patterns of their tracks, the rituals of their mating dances, and mystic signs within their entrails. It was believed that rabbits burrowed underground in order to better commune with the spirit world, and that they could carry messages from the living to the dead and from humankind to the faeries.

was like eating one’s own grandmother -- perhaps due to the sacred connection between hares and various goddesses, warrior queens, and female faeries, or else due to the belief that old "wise women" could shape-shift into hares by moonlight. The Celts used rabbits and hares for divination and other shamanic practices by studying the patterns of their tracks, the rituals of their mating dances, and mystic signs within their entrails. It was believed that rabbits burrowed underground in order to better commune with the spirit world, and that they could carry messages from the living to the dead and from humankind to the faeries.

As Christianity took hold across Europe, hares and rabbits, so firmly associated with the Goddess, came to be seen in a less favorable light -- viewed suspiciously as the familiars of witches, or as witches themselves in animal form. Numerous folk tales tell of men led astray by hares who are really witches in disguise, or of old women revealed as witches when they are wounded in their animal shape. In one well-known story from Dartmoor, a mighty hunter named Bowerman disturbed a coven of witches practicing their rites, and so one young witch determined to take revenge upon the man. She shape-shifted into a hare, led Bowerman through a deadly bog, then turned the hunter and his hounds into piles of stones, which can still be seen today. (The stone formations are known by the names Hound Tor and Bowerman’s Nose.)

"Demonic" hares and rabbits are found on cathedral carvings and in other forms of Christian sacred art -- but we also find the opposite: the pagan Three Hares symbol mentioned above, adapted for Christian use, and unblemished white rabbits representing purity, piety, and the Holy Virgin.

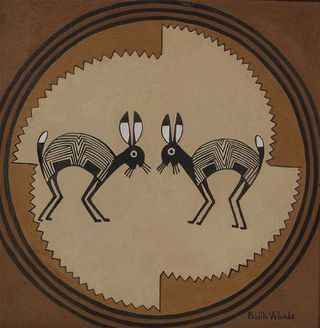

Among the many different Native American story traditions, Trickster tales featuring Coyote or Raven tend to be best known to non-Native audiences, but there are also a large number of tales that feature a trickster Rabbit or Hare, particularly among the Algonquin-speaking peoples of the central and eastern woodland  tribes.

tribes.

Nanabozho (or Manabozho) the Great Hare, for instance, is a powerful figure found in the tales of the Algonquin, Fox, Menoimini, Ottawa, Ojibwa, and Winnebago tribes. In some stories, Nanabozho is a revered culture hero -- creator of the earth, benefactor of humankind, the bringer of light and fire, and teacher of sacred rituals. In other tales he’s a clown, a thief, a lecher, or a cunning predator -- an ambivalent, amoral figure dancing on the line between right and wrong. In Potawatomi myth, Wabosso is the Great White Hare (and the younger brother of Nanabozho) who travels north to become the greatest of magicians among the supernaturals. The Utes tell the story of Ta-vwots, the Little Rabbit, who shatters the sun and destroys the world, all of which must be created again; and an Omaha rabbit brings the sun down to earth while trying to catch his own shadow. The Cherokee, the Creek, the Biloxi and other tribes tell humorous stories of a mischievous Rabbit who is cousin to Br’er Rabbit and Compair Lapin, outwitting foes and puncturing the pride of friends with his clownish antics.

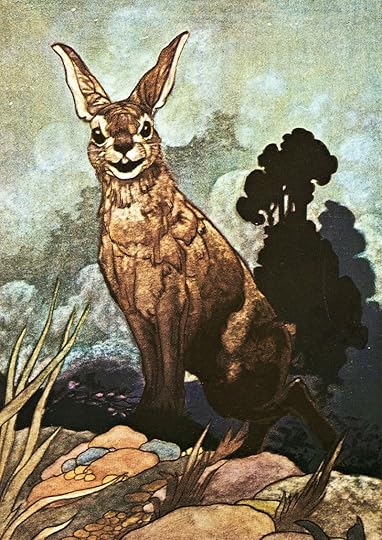

The jackalope legends of the American Southwest are stories of a more recent vintage, consisting of purported sightings of rabbits or hares with horns like antelopes. The legend may have been brought to North American by German immigrants, derived from the Raurackl (or horned rabbit) of the German folklore tradition.

Rabbits and hares are both good and bad in Trickster tales found all the way from Asia and Africa to North America. In the Panchatantra tales of India, for example, Hare is a wily Trickster whose cleverness and cunning is pitted against Elephant and Lion, while in Tibetan folktales, quick-thinking Hare outwits the ruses  of predatory Tiger. In Japan, the fox is the primary Trickster animal, but hares too are clever, tricky characters. Hares in Japanese folktales tend to be crafty, clownish, mischievous figures (usually male) -- as opposed to fox Tricksters (kitsune), who are more seductive, secretive, and dangerous (usually female). In West Africa, many tribal cultures, such as the Yoruba of Nigeria and the Wolof of Senegal, have traditional story cycles about an irrepressible hare Trickster who is equal parts rascal, clown, and culture hero. In one pan-African story, the Moon sends Hare, her divine messenger, down to earth to give mankind the gift of immortality. "Tell them," she says, "that just as the Moon dies and rises again, so shall you." But Hare, in the role of Trickster buffoon, manages to get the message wrong, bestowing mortality instead and bringing death to the human world. The Moon is so angry, she beats Hare with a stick, splitting his nose (as it remains today). It is Hare’s role to lead the dead to the Afterlife in penance for what he’s done.

of predatory Tiger. In Japan, the fox is the primary Trickster animal, but hares too are clever, tricky characters. Hares in Japanese folktales tend to be crafty, clownish, mischievous figures (usually male) -- as opposed to fox Tricksters (kitsune), who are more seductive, secretive, and dangerous (usually female). In West Africa, many tribal cultures, such as the Yoruba of Nigeria and the Wolof of Senegal, have traditional story cycles about an irrepressible hare Trickster who is equal parts rascal, clown, and culture hero. In one pan-African story, the Moon sends Hare, her divine messenger, down to earth to give mankind the gift of immortality. "Tell them," she says, "that just as the Moon dies and rises again, so shall you." But Hare, in the role of Trickster buffoon, manages to get the message wrong, bestowing mortality instead and bringing death to the human world. The Moon is so angry, she beats Hare with a stick, splitting his nose (as it remains today). It is Hare’s role to lead the dead to the Afterlife in penance for what he’s done.

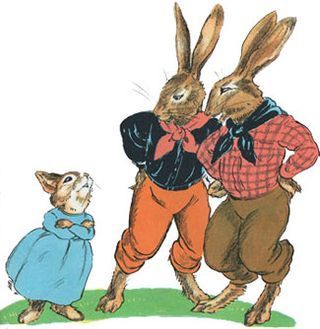

African hare stories traveled to North America on the slavers’ ships, mixed with rabbit tales of the Cherokee and other tribes, and were transformed into the famous Br’er Rabbit stories of the American South. These stories were passed orally among slaves, for whom Br’er (Brother) Rabbit was a perfect hero, besting more powerful opponents through his superior intelligence and quicker wits. the The Br’er Rabbit stories were  written down and published by Joel Chandler Harris in the 19th century in a now classic collection narrarated by the fictional Uncle Remus. At the same time that Chandler Harris was recording Br’er Rabbit stories from the African American oral tradition, folklorist Alcee Fortier was setting down the folk tales of the Cajun (French Creole) culture of southern Louisiana -- including delightful stories of a fast-talking rabbit Trickster called Compair Lapin. Like Br’er Rabbit, or the hares of West African lore, Compare Lapin is a rascal who manages to get himself into all kinds of trouble -- and then smoothly finds his way back out again through cleverness and guile. (Bugs Bunny owes more than a little of his character to this folkloric archetype.)

written down and published by Joel Chandler Harris in the 19th century in a now classic collection narrarated by the fictional Uncle Remus. At the same time that Chandler Harris was recording Br’er Rabbit stories from the African American oral tradition, folklorist Alcee Fortier was setting down the folk tales of the Cajun (French Creole) culture of southern Louisiana -- including delightful stories of a fast-talking rabbit Trickster called Compair Lapin. Like Br’er Rabbit, or the hares of West African lore, Compare Lapin is a rascal who manages to get himself into all kinds of trouble -- and then smoothly finds his way back out again through cleverness and guile. (Bugs Bunny owes more than a little of his character to this folkloric archetype.)

Whether hovering above us in the arms of a moon goddess or carrying messages from the Netherworld below, whether clever or clownish, hero or rascal, whether portent of good tidings or ill, rabbits and hares have leapt through myths, legends, and folk tales all around the world -- forever elusive, refusing to be caught and bound by a single definition. The precise meaning, then, of the ancient Three Hares symbol carved into our village church is bound to be just as elusive and mutable as the myths behind it. It is a goddess symbol, a Trickster symbol, a symbol of the Holy Trinity, a symbol of death, redemption and rebirth…all these and so much more.

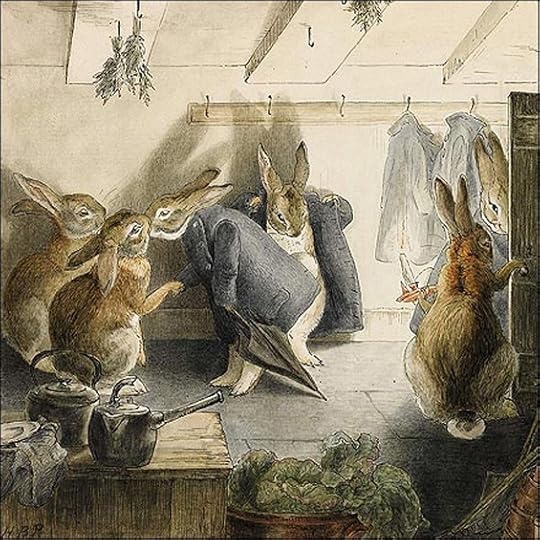

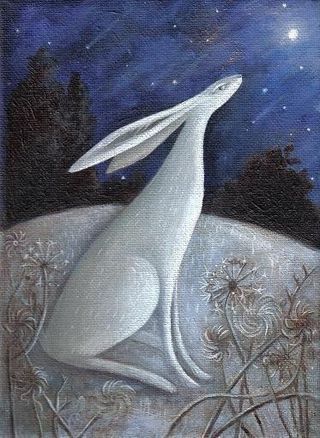

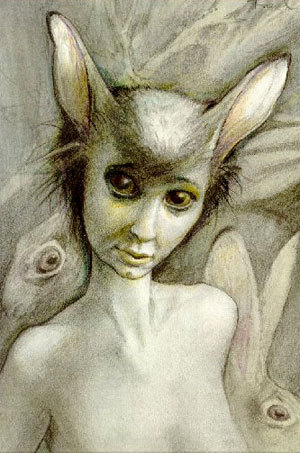

Images above: "Three Hares" by Jackie Morris, "Three Hares" by Brian Froud, "Nature in Art" by Eleanor Ludgate, "The Mockingbird and the Hare" by Kelly Louise Judd, "Wishing on a Blue Moon" by Karen Davis, "Girl and Rabbit" photographed by Katerina Plotnikova, "Brown Hare (Suffolk)" photographed by Michael Rae, "Thumper" (from my novel The Wood Wife) by Brian Froud, "Eostre" by Danielle Barlow, "Easter Rabbits" by Mr. Finch, "Hare" sculpture by Beth Cavener Stichter, "Desert Cottontail" sculpture by Mark Rossi, Desert Jackrabbit photograph (Wikipedia), my "Desert Bunny Girl with Prayer Feathers" sketch, "Mimbres Rabbits" by Pablita Verlarde (Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico), "Boxing Hares" photograph (The Independent), "The March Hare, Dormouse, and Mad Hatter" by John Tenniel, "Moon Rabbit" netsuke by Eiichi (Japan, late 19th Century), illustration from "The Tortoise and the Hare" by Charles Robinson, "Country Bunny" by Marjorie Hack, two more of my Bunny Girls, a rabbit study and "The Rabbit's Christmas Party" by Beatrix Potter, the March Hare at "The Mad Hatter's Tea Party" by Arthur Rackham, and "Young Hare" by Albrecht Dürer.

Images above: "Three Hares" by Jackie Morris, "Three Hares" by Brian Froud, "Nature in Art" by Eleanor Ludgate, "The Mockingbird and the Hare" by Kelly Louise Judd, "Wishing on a Blue Moon" by Karen Davis, "Girl and Rabbit" photographed by Katerina Plotnikova, "Brown Hare (Suffolk)" photographed by Michael Rae, "Thumper" (from my novel The Wood Wife) by Brian Froud, "Eostre" by Danielle Barlow, "Easter Rabbits" by Mr. Finch, "Hare" sculpture by Beth Cavener Stichter, "Desert Cottontail" sculpture by Mark Rossi, Desert Jackrabbit photograph (Wikipedia), my "Desert Bunny Girl with Prayer Feathers" sketch, "Mimbres Rabbits" by Pablita Verlarde (Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico), "Boxing Hares" photograph (The Independent), "The March Hare, Dormouse, and Mad Hatter" by John Tenniel, "Moon Rabbit" netsuke by Eiichi (Japan, late 19th Century), illustration from "The Tortoise and the Hare" by Charles Robinson, "Country Bunny" by Marjorie Hack, two more of my Bunny Girls, a rabbit study and "The Rabbit's Christmas Party" by Beatrix Potter, the March Hare at "The Mad Hatter's Tea Party" by Arthur Rackham, and "Young Hare" by Albrecht Dürer.

December 17, 2014

"Into the Woods" series, 33: The Folklore of Sheep

Sheep, like goats, are associated with Christmas in folk tales told across northern Europe and the British Isles. On Christmas eve, these tales report, all sheep face east, bow three times, and are gifted with the power of speech from the stroke of midnight until the rise of the sun. This holy ritual cannot take place under the gaze of human beings, but provided the sheep are unobserved and unaware, their conversations can be  overheard. In some accounts, the sheep sing hymns; in others, they foretell events of the year to come; and in some they gossip, praising or bemoaning the conditions in which they live. A grumbling sheep, mind you, is a cause for worry, because sheep are especially beloved and protected by Mother Mary in the folklore tradition, and a black mark is lodged in the heavenly accounts against farmers or shepherds who treat them ill.

overheard. In some accounts, the sheep sing hymns; in others, they foretell events of the year to come; and in some they gossip, praising or bemoaning the conditions in which they live. A grumbling sheep, mind you, is a cause for worry, because sheep are especially beloved and protected by Mother Mary in the folklore tradition, and a black mark is lodged in the heavenly accounts against farmers or shepherds who treat them ill.

Going back to myths older than Christianity: Duttur was the Sumerian pastoral goddess associated with ewes, milk, and arts of the dairy; she was the mother of Tammuz: the shepherd god of rebirth, fertility, and new growth in spring. Likewise, the ram-headed Khnum in Egyptian myth was a god of rebirth and pastoral regeneration. As one of the oldest of Egyptian deities, he also the god of creation, forming human bodies in clay on a potter's wheel and placing them inside their mother' wombs. In Greek myth, Aristaios (son of Apollo and Cyrene) was the god of shepherds and beekeepers. The island of Ceos was the center of his cult (though he is also associated with the founding of Thebes), where his followers practiced "weather magic" and were renown for their fine herds and dairy skills.

In Irish myth, Brigid (the goddess of poetry and husbandry, among other things) was the owner of Cirb, a castrated ram (or wether) who was king of all the rams and sheep of Ireland -- including the seven famous magical sheep owned by the sea god Manannán. These sheep, it was said, could produce enough wool to clothe every man, woman, and child the world over.

The "lamb of god" -- representing innocence, purity, and sacrifice for the greater good -- is a symbol found in all three of the major Abrahamic religions and especially in Christianity, where it's been widely represented all forms of Christian art and iconography. By contrast, lambs play little part in either Buddhist or Hindu lore, though the bold and virile ram appears in Asian myth in a variety of ways. A ram was present at the birth of Buddha, is a symbol of the passing year in Tibet, and is sacred (like the goat) to Agni, the Vedic god of fire, in the Hindu pantheon. Agni's ram is a symbol of sacrifice, but not a physical sacrifice of the animal itself; rather, of personal sacrifice in the form of spiritual practice and devotion.

Those born in the Chinese Year of the Sheep are said to be especially sensitive, creative, empathetic, and anxious; while those born under the sign of Aries the Ram in Western astrology are daring, lusty, quick-witted and honest, but also rather obstinate.

In Bulgaria, and other parts of eastern Europe, rams are said to be beyond the reach of evil; thus their image became a totem used to keep bad luck and illness at bay through carvings found on household utensils, domestic buildings, stables, and barns.

"Sheep breeding," writers Dr. Vihra Baeva, "has always been the main source of livelihood in the Bulgarian lands. That is why, in traditional culture, shepherds are held in high esteem and a large flock of sheep is sung praise of as a symbol of wealth and prosperity. The bells on the sheep’s necks, called chan or hlopka, which chime in harmony also give a sense of pride. Christmas carols express wishes that the flock may yagni (derived from the word for lamb) but also blizni (twin-lambs). They sing of fine-wool sheep, horn-twisting rams and white-faced lambs. The animal described as vaklo is especially prized -- i.e. animals that are white with dark rings around the eyes. That is why a pretty lass, who by and large would have black eyes is compared to a lamb that is vaklo, gentle and loved."

In the folklore of the British countryside, black sheep were largely considered lucky creatures -- in contrast to European lore where exactly the opposite was true, from which we get idioms like "the black sheep of the family" and the black sheep of children's rhymes and fairy tales.

The phrase "a wolf in sheep's clothing" is of Biblical origin (from The Gospel of Matthew), but can also be found in Aesop's Fables. "Two shakes of a lamb's tail," meaning to do something quickly, appears to have come from early settlers in either America or New Zealand (depending on which source you consult), popularized by Richard Barham’s book Ingoldsby Legends (1840). It's believed to have derived from way that high-spirited lambs wag their tails while feeding.

There are many different theories on where the idea of counting sheep in order to fall asleep comes from, but one of the most interesting is that it's rooted in the old Celtic dialects, used by shepherds to count their sheep long after general use of these dialects had disappeared. This repetition of numbers, chanted in an ancient language in a sing-song manner, was said to send children into peaceful slumber as their elders watched over the herds.

The fairy folk of Brittinay, Wales, and here in the West Country keep flocks of fairy sheep (and cattle), and are said to steal the sheep of local farmers in order to replenish their stock. Various charms, herbs, and rituals can be used to keep straying sheep safe from fairy hands. In some accounts, fairy sheep are diminutive in size, while in others they resemble ordinary animals except for the strange color of their eyes. Sheep who appear on Dartmoor roads at night and disappear in the blink of an eye are ones who belong to piskie folk, and woe betide any who harm them.

Our own dramatic sheep encounter occurred early one morning several years ago, when Tilly began barking frantically and our daughter went outside to investigate. A few moments later she was back again, dumbfounded. "There's a sheep in our back garden," she reported.

On closer inspection, our visitor turned out to be a ram -- a big, handsome fellow who was not best pleased to find himself in this unfamiliar terrain, far from his herd. He had somehow wandered from a farmer's field, through the woods, over a stream, past the garden gate, up a few stairs and onto the porch of Howard's office cabin, where the animal snorted, snuffled, pawed the ground and eyed us in great alarm. Howard was called, Tilly kept on barking, and the ram got more and more agitated while we tried to figure out how on earth to get him off the porch and back into the woods. This being the 21st century, Howard turned to the internet for advice on "how move a ram," and we learned we should herd him slowly, slowly, with plenty of space between him and us. Otherwise the poor fellow would panic and bolt and end up heaven knew where.

We must have been a fine sight that morning, all of us in our pyjamas still, Tilly dancing excitedly at our feet, while we guided the ram off the porch...down its stairs...through a break in the hedge...past my studio...through the woodland gate...and over the stream behind it. Finally, our visitor disappeared into the trees with a flash of his hooves, heading (we hoped) towards home.

If I hadn't snapped the picture below, I would wonder if I'd dreamt it all....

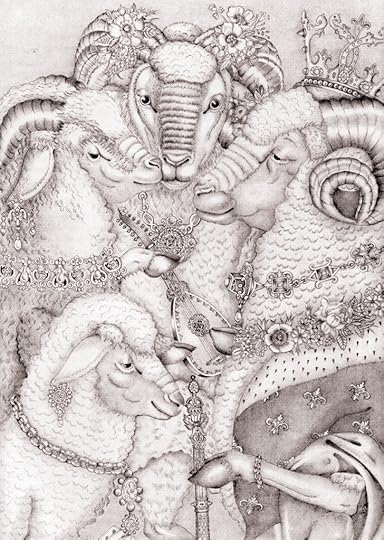

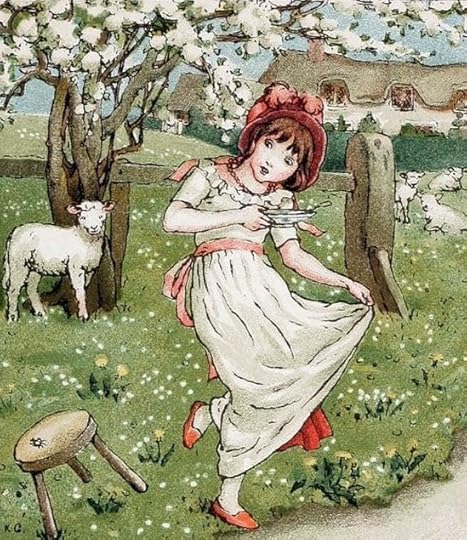

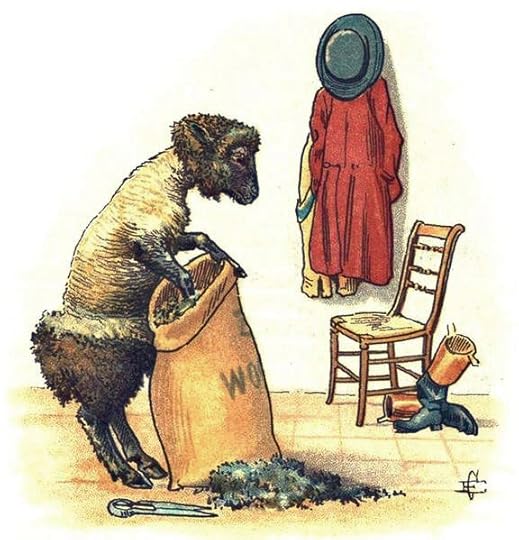

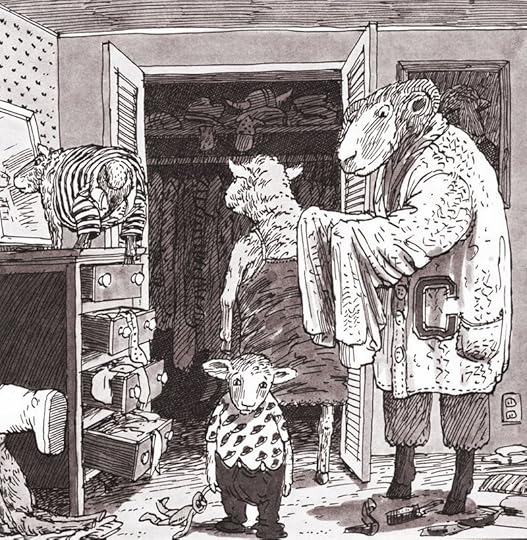

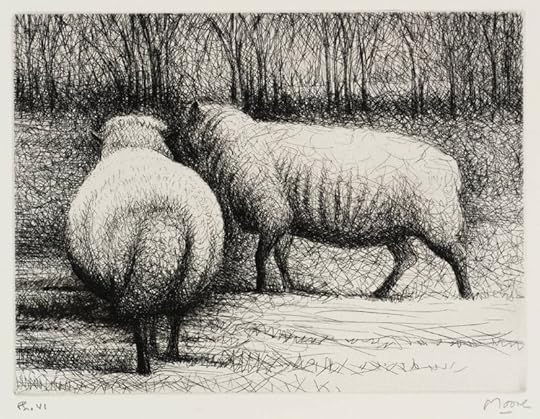

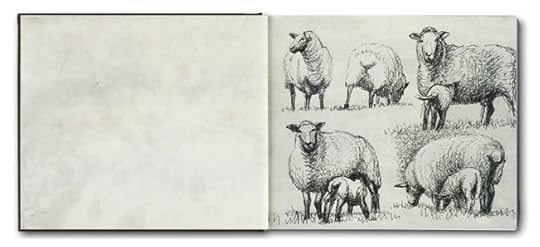

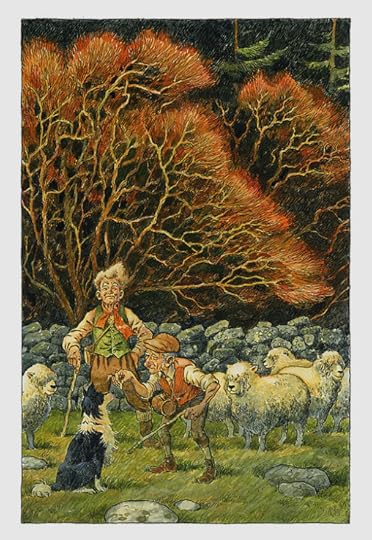

Images above: Adrienne Segur's illustration for Madame D'Aulnoy's classic fairy tale "The Royal Ram"; "Donkey Nanny, Lombardy, Italy" photographed by Elspeth Kinneirn (National Geographic); "Head of a Ewe," a Sumerian sculpture from the Protoliterate period (c 3500–3000 BC); three photographs of sheep and lambs here on Dartmoor by Helen Mason; "Little Miss Muffet and Her Sheep" by Kate Greenaway (1846-1901); "Baa Baa Black Sheep" by Edmund Caldwell (1880); "Baa Baa Black Sheep" by Paula Rego (1989); an illustration from "Baaa" by David Macauley; sheep studies and sketchbook by Henry Moore (1898-1986); "Training Day" by David Wyatt; Tilly watching sheep in a nearby farmer's field; and the ram on Howard's cabin porch.

Images above: Adrienne Segur's illustration for Madame D'Aulnoy's classic fairy tale "The Royal Ram"; "Donkey Nanny, Lombardy, Italy" photographed by Elspeth Kinneirn (National Geographic); "Head of a Ewe," a Sumerian sculpture from the Protoliterate period (c 3500–3000 BC); three photographs of sheep and lambs here on Dartmoor by Helen Mason; "Little Miss Muffet and Her Sheep" by Kate Greenaway (1846-1901); "Baa Baa Black Sheep" by Edmund Caldwell (1880); "Baa Baa Black Sheep" by Paula Rego (1989); an illustration from "Baaa" by David Macauley; sheep studies and sketchbook by Henry Moore (1898-1986); "Training Day" by David Wyatt; Tilly watching sheep in a nearby farmer's field; and the ram on Howard's cabin porch.

December 16, 2014

"Into the Woods" series, 32: The Folklore of Goats

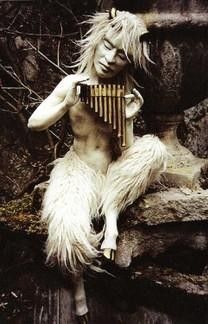

In myths all around the world the goat is associated with wilderness. The Greco-Roman gods who inhabited the forest depths and remote mountaintops roamed the backlands with goat companions, and appeared in the  form of goat-men themselves: Pan, Silvanus, Faunus, Bacchus, Dionysis, goat lovers all. Female goats were sacred to Artemis/Diana, goddess of female independence and the hunt, and goat milk was a common offering with which to honor or propitiate her.

form of goat-men themselves: Pan, Silvanus, Faunus, Bacchus, Dionysis, goat lovers all. Female goats were sacred to Artemis/Diana, goddess of female independence and the hunt, and goat milk was a common offering with which to honor or propitiate her.

In Sumerian myth, goats belonged to Marduk, the ancient god of magic and patron deity of Babylon, and were regarded as potent, uncanny beings due to this association. Agni, the Vedic god of fire, rides a chariot pulled by goats in some Hindu tales; as does Thor, the god of thunder, strength, and virility in Scandinavian myth. Thor's goats, called Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr, are slaughtered and feasted on each night, but when their bones are carefully gathered together these magical goats return to life.

The Yule Goat, found across northern Europe, is a straw figure traditionally made from the very last sheaf of grain to be harvested each year. It can range in size from tiny to huge, and has magical properties. The custom is pagan in origin, but has been become attached to  Christmas lore in a number of northern countries: Father Christmas is sometimes pictured as riding on the back of a goat in Scandinavia, for example, and "going Yule goat" refers to the custom of carolling or wassailing. In some regions, a man dressed as a goat accompanies the singers as they go from house to house; he is a Trickster figure, playing pranks on households not sufficiently hospitable. In other traditions, the Yule Goat is a gentle, invisible spirit who watches to make sure the winter rituals are correctly carried out, or a figure who, like Santa Claus today, distributes presents to children.

Christmas lore in a number of northern countries: Father Christmas is sometimes pictured as riding on the back of a goat in Scandinavia, for example, and "going Yule goat" refers to the custom of carolling or wassailing. In some regions, a man dressed as a goat accompanies the singers as they go from house to house; he is a Trickster figure, playing pranks on households not sufficiently hospitable. In other traditions, the Yule Goat is a gentle, invisible spirit who watches to make sure the winter rituals are correctly carried out, or a figure who, like Santa Claus today, distributes presents to children.

The Krampus is a relative of the Yule Goat, but he is far less benign. Known largely in Alpine regions, he's a hairy, frightening beast-man with the horns and hooves of a goat, wearing rattles and bells around his waist. He distributes gifts to good children and drags the naughty ones off into the forest.

The symbolism attached to goats varies a great deal around the world. In some places, they represent gentleness, endurance, spiritual purity, and sacrifice; in others, independence, lust, virility, fertility,  creative vigor, and stubbornness. Those born in the Chinese year of the goat are said to be shy, creative, and prone to perfectionism, while in Persian myth, goats symbolize leadership, forcefulness, and strength. This range reflects the nature of goat themselves. Though they were among the earliest of animals to be domesticated by humankind, they are also among the quickest to return to a feral state when opportunity arises.

creative vigor, and stubbornness. Those born in the Chinese year of the goat are said to be shy, creative, and prone to perfectionism, while in Persian myth, goats symbolize leadership, forcefulness, and strength. This range reflects the nature of goat themselves. Though they were among the earliest of animals to be domesticated by humankind, they are also among the quickest to return to a feral state when opportunity arises.

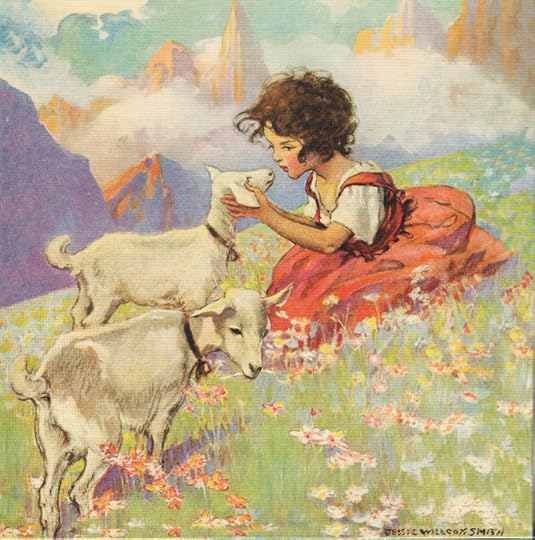

In old stories ranging from Aesop's Fables to fairy tales and nursery rhymes, goats are cannier than sheep (think, for example, of the clever Three Billy Goats Gruff), and though they're generally not full Trickster characters, they tend to retain an edge of Trickster's wiliness and wildness. Even in more recent stories for children -- such as Heidi, the classic by Johanna Spyri (which I adored as a child) -- they represent our connection to nature and life lived in turn with nature's cycles...carrying the echo of goat-legged Pan wherever they roam the mountains, and wherever we follow.

"From sunrise to sunset, I was in the forest, sometimes far from the house, with my goat who watched me as a mother does a child," wrote Mexican painter Diego Rivera (in My Art, My Life). "All the animals in the forest became my friends, even dangerous and poisonous ones. Thanks to my goat-mother and my Indian nurse, I have always enjoyed the trust of animals -- a precious gift. I still love animals infinitely more than human beings."

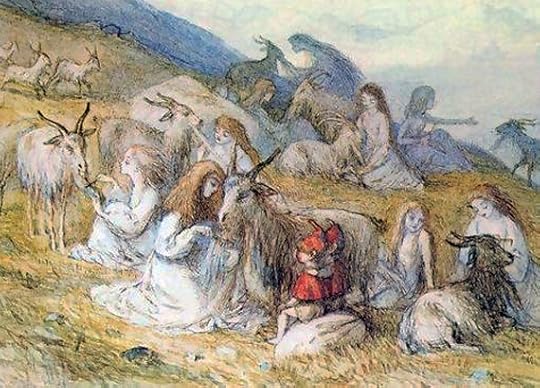

Imagery above: goats photographed by Adrienne Elliot, a sculpture of Pan by Wendy Froud, a Swedish Yule Goat photographed in 1917, "Yule Goat" by John Bauer (1882-1918), a straw Yule Goat in Sweden (2009), a photograph of Krumpus figures by Charles Fregere (from his brilliant Wilder Mann series), "Old Goats Home" by David Wyatt (initial sketch for a painting), "The Gidleigh Goat" by David Wyatt (Gidleigh is a village close to Chagford), "Heidi and the Goats" by Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935), a goat sketch by Diego Rivera (1886-1957), "Girls Combing the Beards of Goats" by Richard Doyle (1834-1883), and a goat image from the Russian surrealist photographer Katerina Plotnikova.

Imagery above: goats photographed by Adrienne Elliot, a sculpture of Pan by Wendy Froud, a Swedish Yule Goat photographed in 1917, "Yule Goat" by John Bauer (1882-1918), a straw Yule Goat in Sweden (2009), a photograph of Krumpus figures by Charles Fregere (from his brilliant Wilder Mann series), "Old Goats Home" by David Wyatt (initial sketch for a painting), "The Gidleigh Goat" by David Wyatt (Gidleigh is a village close to Chagford), "Heidi and the Goats" by Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935), a goat sketch by Diego Rivera (1886-1957), "Girls Combing the Beards of Goats" by Richard Doyle (1834-1883), and a goat image from the Russian surrealist photographer Katerina Plotnikova.

December 14, 2014

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, some warm, smoky music from Brazil for a cold December morning on Dartmoor....

Above: "Ainda Bem" by Marisa Monte, from Rio de Janeiro. Monte trained as an opera singer in Rome before returning to Brazil to sing jazz, blues, samba, and other forms of popular music. She's recorded ten albums over twenty-five years, including Verdade Uma Ilusão (2014).

Below: "Atrás da Porta" by Ana Cañas, a singer from from São Paulo. This video is part of Projeto Studio62's "minimalista" series, presenting the songs of Brazilian composer Chico Buarque in a raw and intimate way. Cañas has recorded four albums, the most recent of which is Coração Inevitável (2013).

Next:

"Bela Flor" by singer/songwriter Maria Gadú, also from São Paulo. She's recorded five albums since 2009, the latest of which is Nós.

And last:

A burst of sunshine from Luísa Maita, raised in a musical family in São Paulo. "Alento" comes from her debut album, Lero-Lero (2010).

If you'l like a little more this mornings, Maria Gadú's version of Pink's "Who Knew" is a real treat.

December 11, 2014

On Dragons

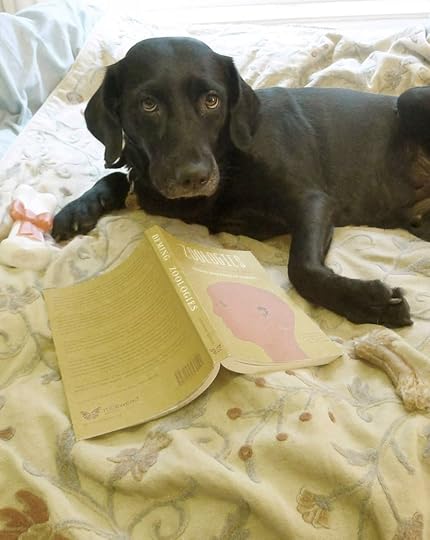

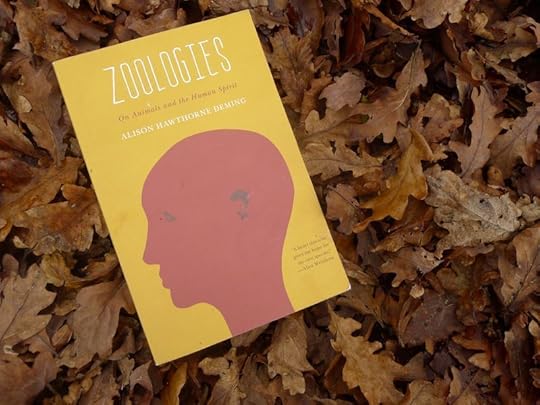

Here's one more exquisite passage from Alison Hawthorne Deming's Zoologies: On Animals and the Human Spirit (discussed in Tuesday's post). It comes from her essay "Dragons," which I recommend reading in full:

"Earth is teeming with creatures great and small, tame and wild, endangered and endangering, hideous and gorgeous. Animals are a manifestation of the planet's imagining, and dragons are a manifestation of Earth's imagining that takes place in the human mind. We're not the only animals that can carry other animals in mind. Who hasn't seen a dog running in his sleep after inner prey? Is only his body imagining the rabbit he chases when his paws gallop through the snoring or is his mind too capable of conjuring the cottontail? It's impossible to know. But I'm convinced that all the animal sentience in the world makes for a massive contemplative practice that is humming along at any given moment -- the crow perched on a spruce surveying the meadows, the bobcat trotting down a woods lane in a moving meditation, the humpback whale going tailfins up on a deep and sonorous dive, the crickets percussing their endless hum, the squirrels dismantling pinecones like manic monks with their prayer beads, the Jersey cows chewing their cuds while they lie under maple trees and stare at the dandelions, the elephants rumbling out their hellos to each other across the savanna, the rabbits dancing for mystical joy in the rain as I have seen them do in the desert, the dragons lunging from storybook pages and TV screens and medieval engravings -- all of them an expression of Earth's spirituality, the something greater than rock and light and water, the something beyond matter that seeks to be. A creature of the senses that drinks in the world, a creature of an inwardness that seeks its own ends separate from external factors. Aren't we all, all of us, animals here together, double agents in our own bodies?"

"Earth is teeming with creatures great and small, tame and wild, endangered and endangering, hideous and gorgeous. Animals are a manifestation of the planet's imagining, and dragons are a manifestation of Earth's imagining that takes place in the human mind. We're not the only animals that can carry other animals in mind. Who hasn't seen a dog running in his sleep after inner prey? Is only his body imagining the rabbit he chases when his paws gallop through the snoring or is his mind too capable of conjuring the cottontail? It's impossible to know. But I'm convinced that all the animal sentience in the world makes for a massive contemplative practice that is humming along at any given moment -- the crow perched on a spruce surveying the meadows, the bobcat trotting down a woods lane in a moving meditation, the humpback whale going tailfins up on a deep and sonorous dive, the crickets percussing their endless hum, the squirrels dismantling pinecones like manic monks with their prayer beads, the Jersey cows chewing their cuds while they lie under maple trees and stare at the dandelions, the elephants rumbling out their hellos to each other across the savanna, the rabbits dancing for mystical joy in the rain as I have seen them do in the desert, the dragons lunging from storybook pages and TV screens and medieval engravings -- all of them an expression of Earth's spirituality, the something greater than rock and light and water, the something beyond matter that seeks to be. A creature of the senses that drinks in the world, a creature of an inwardness that seeks its own ends separate from external factors. Aren't we all, all of us, animals here together, double agents in our own bodies?"

The dragon illustrations above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). Zoologies: On Animals and the Human Spirit by Alison Hawthorne Deming was published by Milkweed Editons, US, 2014. Related post: "Dealing with dragons."

The dragon illustrations above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). Zoologies: On Animals and the Human Spirit by Alison Hawthorne Deming was published by Milkweed Editons, US, 2014. Related post: "Dealing with dragons."

December 10, 2014

Fairy Tales, Then & Now

I loved The Diane Rehm Show on public radio when I lived in the States, so it was a thrill to learn that the show would be devoting a segment to "the history and modern relevance of fairy tales" this week. Fairy tales are usually covered in the media in a shallow (and sometimes deeply ignorant) way, but I trusted Ms. Rehm to do much better than this -- particularly as the guests she'd lined up were Maria Tatar, Marina Warner, and Ellen Kushner. Perfect! And, indeed, it was a splendid discussion. If you missed it, go here to have a listen.

(For those of you unfamiliar with the show, Diane Rehm's voice sounds strained because of spasmodic dysphonia, a neurological voice disorder that almost ended her career. Instead, she returned to the radio and used her show as a platform to raise public awareness of the condition. A remarkable woman.)

And on the subject of fairy tales:

I hope you haven't missed Marina Warner's excellent new book, Once Upon a Time: A Short History of the Fairy Tale, which just came out in October from Oxford University Press. "The more one knows fairy tales," she notes, "the less fantastical they appear; they can be vehicles of the grimmest realism, expressing hope against all the odds with gritted teeth."

The editors of Mirror, Mirrored (Gwarlingo Press) are planning a limited edition volume of Grimms Fairy Tales illustrated by contemporary artists from a wide range of disciplines, with an Introduction by Karen Joy Fowler. They are running a crowd-funding campaign for it now, with some lovely art as donation rewards.

And last: Go here to watch a video of Philip Pullman discussing the enduring power of stories in a clip from the BBC's Newsnight programme.

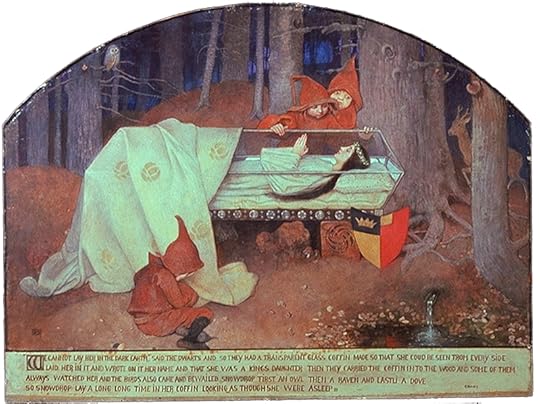

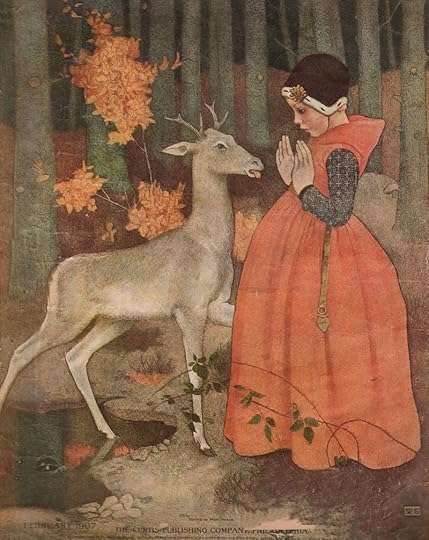

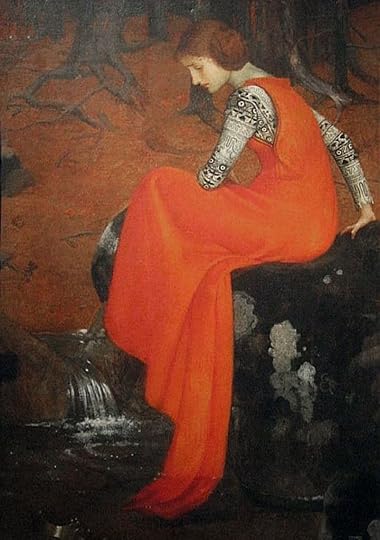

The illustrations in this post are by Marianne Stokes (1855-1927) -- a painter who, though little known today, was considered one of the leading women artists of Victorian England.

Born in Austria, Marianne studied in Munich and Paris, lived in arts colonies in Brittany and Denmark, then settled in St. Ives, Cornwall with her British husband, landscape painter Adrian Stokes. In Cornwall, she was part of the lively Newlyn group of plein air artists (along with her close friend Elizabeth Stanhope Forbes), until falling under the spell of Pre-Raphaelitism from the 1890s onward. The Stokes then lived and worked in London, with frequent painting trips abroad -- spending half their year in rural Austria, Hungry, and the Tartra Mountain villages between Slovakia and Poland. If you'd like to know more, I recommend Utmost Fidelity: The Painting Lives of Marianne and Adrian Stokes by Magdalen Evans.

lllustrations above: "The Frog Prince," "Snow White," an untitled magazine cover illustration from 1907, and "Melisande." The tapestry design is "Women's Worth" (based on a Schiller poem), created for Morris & Co. in 1912.

On Animals and the Human Spirit

I've just read Zoologies, a new collection of essays on animals, natural history, life, and art by Alison Hawthorne Deming, which I highly recommend. Here's a passage from Deming's Introduction to give you a taste:

"Animals surrounded our ancestors. Animals were their food, clothes, adversaries, companions, jokes, and their gods. In the Paleolithic period of the Great Hunt, Joseph Campbell writes, 'man's ubiquitous nearest neighbors were the beasts in their various species; it was those animals who were his teachers, illustrating in their manners of life the powers and patternings of nature.' In this age of mass extinction and the industrialization of life, it is hard to touch the skin of this long and deep companionship. Now we surround the animals and crowd them from their homes. They are the core of what we are as creatures, sharing a biological world and inhabiting our inner lives, though most days they feel peripheral -- a wag from the dog, an ankle embrace from the cat, the pleasure of sighting a house finch feeding outside the window, the thrill of spotting a hedgehog waddling along a path in Prague or a fox trotting across an urban campus in Denver. Animality and humanity are one, expressions of the planet's brilliant inventiveness, and yet the animals are leaving the world and not returning.

"What do animals mean to the contemporary imagination? We do not know. Or we have forgotten. Or we are too busy to notice. Or we experience psychic numbing to cope with the scale of extinctions and we feel nothing. Or we begin through our grief to realize how much we love our fellow creatures and tend to them. Or we write about them, trying to figure out what the experience of animals is and how they came to be so ingrained in human mind and emotion, to remember what it feels like to be embedded in the family of animals, to see the ways animals inhabit and limn our lives, entering our days and nights, unannounced and essential."

It's a wonderful book, beautifully composed, dark and painful in places, transcendent in others, and never sentimental. Deming discusses elephants and ants, pigs and oyster, and the animal nature of human beings. "I am tired," she writes, "of the conventional palette with which the lives of animals are painted. Most renderings feel too saturated with gratuitous piety, weighted down by ceaseless elegy, or boastful about heroic encounters on the last islands of wilderness. I want something closer to the marrow of our lived days, as in childhood, when an animal story or encounter could make me wonderstruck."

In these wide-ranging, incisive essays, she has amply achieved this.

Zoologies: On Animals and the Human Spirit by Alison Hawthorne Deming was published by Milkweed Editons, US, 2014. (I recommend the author's previous books as well, especially Writing the Sacred Into the Real.) A few related posts: "The Dance of Joy & Grief," "The Peace of Wild Things," "Wild Neighbors," "Daily Myth," "Holding the World in Balance," and "Animalness.

Zoologies: On Animals and the Human Spirit by Alison Hawthorne Deming was published by Milkweed Editons, US, 2014. (I recommend the author's previous books as well, especially Writing the Sacred Into the Real.) A few related posts: "The Dance of Joy & Grief," "The Peace of Wild Things," "Wild Neighbors," "Daily Myth," "Holding the World in Balance," and "Animalness.

December 9, 2014

Transformations

No words today, just images from the woodland behind the studio, transforming itself through the stages of autumn. Perhaps some of you will provide the words today with quotes or tales or poems....

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers