Tom Kepler's Blog, page 24

July 30, 2013

A Day Out with Mom #9: Dad talks bikes

123rf.comAs a kid in Oceanside, besides helping at the family business, Lee's Auto Court, I also worked odd jobs so I'd have some extra money.

123rf.comAs a kid in Oceanside, besides helping at the family business, Lee's Auto Court, I also worked odd jobs so I'd have some extra money. Mowing lawns and raking leaves were my first jobs during the summer and fall of my eighth grade year. I'd use Dad's push mower, pulling it down the sidewalks to the job, or sometimes the people would own their own mower that I'd use. I also had a job delivering special delivery letters.

When the letter was sent, in addition to the regular stamp, a special delivery stamp was also bought. The stamp had a picture of a boy on a motorcycle. I'd go to the post office and get the letter then walk to deliver it. Sometimes it was a long walk! I was paid by check twice a month. I think the stamp cost seven cents, and I was paid six for each letter I delivered.

One lady whose lawn I mowed--sometimes I'd go over there and they'd all be in the backyard with their clothes off. They had a tall hedge for privacy. I guess they were nudists. When that happened, I'd just go home.

She had an old bicycle, though, with wooden wheels that had the tires shellacked to the wood. Then you'd pump air into the tires, about forty or fifty pounds. I bought the bike for two dollars, took it home, took it all apart, and cleaned and painted it--a bright yellow so people could see me. It had big longhorn style handlebars that really stuck out. The lady's balance got too bad to ride, so I guess that's why she gave it to me so cheap. Two dollars was a lot of money back in those days, though, especially for a kid!

Now I could ride the bike to deliver special delivery. It was really heavy but much faster than walking. I used that bike to deliver letters on into high school. I'd even be in class and deliver letters. I'd check between classes, and if a letter came in I'd tell the teacher. She'd let me go, and when I got back, she'd fill me in on what I'd missed. Some of the roads were good, and some were just dirt roads. Much of the area around Oceanside in those days was just fields and scrub. Now it's all built up and full of people.

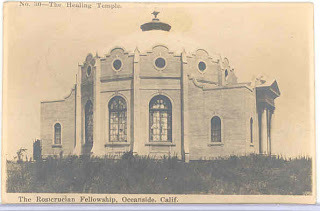

Rosicrucian Fellowship, OceansideOne place I delivered special delivery to regularly was the Rosicrucian Fellowship. Their place was about six miles out of town on a hill that could see off in all four directions--the ocean, the mountains, the desert. When the train came in, it carried mail. I tried to get there soon after the train and then head off to the Fellowship. Their buildings were adobe painted white, a main building and about ten or twelve smaller places for staying that had roofs that leaned down on one side for the rain to run off.

Rosicrucian Fellowship, OceansideOne place I delivered special delivery to regularly was the Rosicrucian Fellowship. Their place was about six miles out of town on a hill that could see off in all four directions--the ocean, the mountains, the desert. When the train came in, it carried mail. I tried to get there soon after the train and then head off to the Fellowship. Their buildings were adobe painted white, a main building and about ten or twelve smaller places for staying that had roofs that leaned down on one side for the rain to run off.I'd knock on the main door and a lady would answer. Sometimes she was asleep and I'd have to come in and wake her. She'd sign for the letters, and I'd take off--maybe back to school. I liked going there because sometimes there'd be a batch of letters I could deliver all at once, and I'd still get paid for every single letter I delivered.

Later on in high school, I'd saved up more money. I wanted to buy a motorcycle for my special delivery job, but Dad didn't want me to own one. He said they were too dangerous. Maybe that was because my older brother Leon was killed in an auto accident when he was about twelve.

Once he went fishing up in Bishop for a couple of weeks, though. He went up there a lot and left the rest of the family to run the auto court. He even met the actor Joel McCrea up there and taught him how to fly fish. McCrea had all the equipment--vest and hip boots and pole--but he didn't know how to cast or where in the stream, much less which flies to use. My dad taught him! I remember my dad said McCrea said, "I'm Joel McCrea, the actor. Seen any of my movies?" Your grandpa said, "No, I don't go to picture shows much."

So Dad was in Bishop and I found out one of my teachers had a Harley for sale because he'd just bought an Indian. I couldn't buy it because the teacher was afraid I'd get in a wreck and not have the permission of my family. Mom went down and signed for the Harley so I could have the bike. I took it home and did the same thing with it that I'd done with the bicycle--took it all apart, cleaned it, and painted it. I painted the Harley black and yellow but a brighter yellow so it could be seen better. I also bought a leather helmet to wear.

My dad came home from fishing, and the motorcycle was all together and being used for my job. I was making more money with it, so he let me keep it. My mom probably had a talk with him, too. She didn't say much, but Dad usually listened when she did--well, sometimes, anyway.

One time I came home and parked the bike. Dad came over and looked at the speedometer. It had a trip switch that would show what was the fastest you'd gone. Then you'd hit the trigger and it'd go back to zero for the next time. The needle showed 110 mph. Dad hit the trigger but didn't say anything.

I worked that special delivery job all the way through high school. It was a good job. I got to get out on my own. It was almost like working for myself because all I had to do was pick up the letters and then deliver them. For everything in between, I was my own boss. Out there on the road, there was a lot of freedom.

It's easy to forget how special it is just to be able to move, to travel, until you get old like me. I'm glad I did what I did when I had the chance. I'm glad you've got your bicycle now and are riding it all over. You should ride it back to Iowa. It's not that far, and even if it is, that's not a bad thing. It's a good thing, like getting a special delivery letter.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on July 30, 2013 04:00

July 26, 2013

When Classroom and Hospital Merge: a dream

I am beginning my day of teaching school, and I hope to hell I am dreaming.

I am beginning my day of teaching school, and I hope to hell I am dreaming.Standing before the class, instead of desks I see a classroom filled with hospital beds, the kind that can be raised at the knees and head.

"Good morning, class," rrrrrrrrrr, "today we are," rrrrrrrrr rrrrrrrrr rrrrr, "going to review punctuation," rrrrrrr rrrrrrr rrrrrrrr rrrrrrr rrrrrrr rrrrrrrr rrrrrrr rrrrrrr rrrrrrrr, "in preparation for the Iowa Assessment Tests."

. . . rrrrrrr rrrrrrr rrrrrrrr rrrrrrr rrrrrrr rrrrrrrr rrrrrrr rrrrrrr rrrrrrrr . . .

"Larry, I don't think you should be sharing Alice's bed. . . . Well, I appreciate you want to pair up as you work, and, yes, I know you're good at punctuation. . . . What's the problem, you say? . . . Well, I'm afraid you might start multi-tasking."

I turn to the chalkboard and write the assignment, then hand out photocopied worksheets. Yes, I have high-tech student desks and the students use computer tablets, but, lucky me, the teacher gets to keep the blackboard.

"Luis, what a dedicated student you are! You've brought your own black satin sheets and pillow cases. And it goes with your black eye shadow." I decide to ignore his earring, which is against school policy.

"We'll start with end punctuation," rrrrrrr rrr rrrrrr rrrrrrr, "the most fundamental," rrrr rrrrrrrrr rrrrrrrr, "the regulation of complete thoughts."

zzzzzz zzzzzz zzzzzzz zzzzzz zzzzzz zzzzzzz zzzzzz zzzzzz zzzzzzz

I could grab my walker and check student progress, but, heck, there are thirty-seven minutes left in the class period. Maybe I'll just rest my eyes for a few minutes. Maybe I'll dream of next semester when I'll be getting my electric wheel chair. Ah, technology . . .

zzzzzz zzzzzz zzzzzzz

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on July 26, 2013 06:48

July 24, 2013

A Day Out with Mom #9: on birth and death

When I was sixteen, I asked my English teacher how to write a letter to Kansas to find out about my adoption. When I got my birth certificate, my mom was mad at me. "You don't need to know about any of that," she said. I wanted to know, though, and she wouldn't help, so I just went ahead and did it on my own.

When I was sixteen, I asked my English teacher how to write a letter to Kansas to find out about my adoption. When I got my birth certificate, my mom was mad at me. "You don't need to know about any of that," she said. I wanted to know, though, and she wouldn't help, so I just went ahead and did it on my own.My birth mother was a Practical Nurse like I became after I graduated. She was part Irish and had reddish hair. My birth certificate said my father was part Indian. It didn't say what tribe, and with Kansas being so close to Oklahoma, it could be anything. Being Indian must have been a good part of him or it probably wouldn't have been mentioned on the birth certificate. One professor at the college where your sister worked told her he could tell she was part Indian by her cheekbones.

It doesn't matter who gave birth to you. Your real parents are the ones that raise you. I told this to your son so he'd know. I told him to love and respect the ones who raise you because they love you. My brother fell apart when he found out I was adopted. I told him it didn't matter. He was my brother, the only one I had, and I loved him.

Even though I'd been blind when young and spent my life not seeing well, I was still my own person and had my own ideas. It was a different time to go to high school back then. The year I graduated was the year of the war, and there weren't many of us to walk across the stage. Those that did were mostly girls because the boys were allowed to graduate early when they turned eighteen. Then they enlisted and were gone to fight. Even though they were so young, they went off to war.

I started nursing at nineteen, working with the woman doctor Contessa Craviotta. Her father was a doctor, too. Her husband was Dr. Bennington. He delivered your sister. He had been a doctor overseas during the fighting so he was kind of tough, but he was a good man and a good doctor. He said about you and your brother, "What've you got going having one boy on Groundhog's Day and the other on St. Patrick's Day?"

Your dad named our first two children, the girls. He named Chenel after her two grandmothers, Blanche and Nellie, using half of each name. Our second daughter he named after me, Betty Susan, but she only lived a day. She's buried in the cemetery on Feather River Boulevard in the area with all the little babies. No name was put on the stone because she didn't live a full day.

I knew there was something different about her because she didn't move like Chenel did. When Chenel was born, I hemorrhaged and had to have many transfusions. I wasn't supposed to have a baby so soon so the blood would settle, but the little baby came along. She was buried in a little white casket. Your grandmothers got her a white gown to wear. Dr. Craviotta wouldn't let me go because I was so weak. I cried and cried, but you've got to keep living and I had your sister to think of.

I named you after your grandfathers, and Pat was named by Dr. Craviotta. We were going to name him "John" after your grandfather's brother, but everybody at the hospital wanted to name your brother "Pat" because he was born on St. Patrick's Day. They said I could take him home early if I did and I'm part Irish, so that's the way he was named.

Both of you boys were put in incubators to keep you warm. You were my smallest child. Your Grandpa Kepler wanted you named "Leon" after your dad's older brother that died. Grandpa was going to town with eggs to sell when he turned the car over and Leon died. Your grandma said that Lee never forgave himself for that. Maybe that is why your grandpa was always so hard on your dad. Your grandpa always said you looked like Leon.

Your Grandpa Kepler would show up in his pink Cadillac with a gallon of strawberry ice cream and a big bowl of popcorn. He'd open the ice cream and sit down on the floor with you kids with spoons and ice cream and popcorn. "You're going to give the kids a stomachache," I'd say, but he'd just laugh and say, "Oh, let 'em have fun!" He liked to laugh and have fun. So does your dad, but he never laughed like your grandpa did. I don't know why. Your Grandma Kepler never laughed out loud so much either.

Your dad worked hard to raise you. When Chenel was born, we lived in a little town called Dobbins, up above Marysville in the mountains. We didn't have a refrigerator--we had an ice box that kept the milk and butter cool. Your dad worked construction, driving the dynamite truck. He did that for a while, but your grandpa didn't like him having such a dangerous job, so your dad got a job being a mechanic. He always liked working on cars, and it was something he was good at. He drove trucks for a while but didn't like being away from his family so much, so he settled down to working on cars, something he did all the time he raised you kids. At one time he was number 6 in ranking of all the Ford mechanics in the United States.

Everything we did, we did with you kids--racing go-carts, baseball, camping. We always did it as a family. On Fridays, I'd work all day getting the little travel trailer set up with food and everything we'd need. I'd make macaroni or potato salad. Then your dad would come home with the ice, we'd load up the food and take off for the mountains. Remember how we'd go up to Indian Creek and you boys would fish and float down the creek on your air mattresses? You boys would pitch your army pup tent and sleep outside. Your dad and I and your sister would sleep in the trailer.

One time your sister had a boy come along to camp with us. We were down at the creek, and your sister let that boy eat the whole bowl of potato salad. I said to him, "How could you go and eat the whole thing?" and he said, "Your potato salad is really good!" I was so mad at him! It was our food to eat, after all, but it was kind of funny.

Your dad and your sister fought all the time. They were too much alike, I think. She left home at seventeen, dropped out of high school her last semester. It was such a silly thing to do but she was so angry. She joined the Job Corps, met some tough kids, dropped out, got married, and had your nephew Bobby. Then she divorced. For a long time Chenel and your dad didn't talk, but when she got older, they got along better. She moved to the trailer court across the road when she was told she had six months to live because of cancer. It was all through her body. We were with her at the end. She wanted her family at the end.

I don't know what's going to happen with your dad. Nobody knows when they are going to die. That's something God knows and decides. Your sister asked her minister, "Why did God do this to me?" He said, "God didn't do this. Your body did." That seemed to help her. She always liked to sing. It was her favorite thing in school, and later she sang in the church choir. Your sister had a beautiful voice. Now she's gone, and I don't know about your dad. He's had a long life, and we've done many things together in our sixty-seven years we've shared. I don't know how long I'm going to live! None of us do.

We've just got to try to enjoy life and be good people. Your dad's like a little baby now a lot of the time, and I'm sad that I can't be with him all of the time because he's in a rest home. I'm not strong enough to take care of him, though. I know that. I'm not senile! But if he wants to come home and gets stronger and can stand, I'll bring him home. We'll figure something out.

I don't know what to do. We've spent so many years together. I guess I've just got to put it all in God's hands.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on July 24, 2013 04:00

A Day Out with Mom #8: on birth and death

When I was sixteen, I asked my English teacher how to write a letter to Kansas to find out about my adoption. When I got my birth certificate, my mom was mad at me. "You don't need to know about any of that," she said. I wanted to know, though, and she wouldn't help, so I just went ahead and did it on my own.

When I was sixteen, I asked my English teacher how to write a letter to Kansas to find out about my adoption. When I got my birth certificate, my mom was mad at me. "You don't need to know about any of that," she said. I wanted to know, though, and she wouldn't help, so I just went ahead and did it on my own.My birth mother was a Practical Nurse like I became after I graduated. She was part Irish and had reddish hair. My birth certificate said my father was part Indian. It didn't say what tribe, and with Kansas being so close to Oklahoma, it could be anything. Being Indian must have been a good part of him or it probably wouldn't have been mentioned on the birth certificate. One professor at the college where your sister worked told her he could tell she was part Indian by her cheekbones.

It doesn't matter who gave birth to you. Your real parents are the ones that raise you. I told this to your son so he'd know. I told him to love and respect the ones who raise you because they love you. My brother fell apart when he found out I was adopted. I told him it didn't matter. He was my brother, the only one I had, and I loved him.

Even though I'd been blind when young and spent my life not seeing well, I was still my own person and had my own ideas. It was a different time to go to high school back then. The year I graduated was the year of the war, and there weren't many of us to walk across the stage. Those that did were mostly girls because the boys were allowed to graduate early when they turned eighteen. Then they enlisted and were gone to fight. Even though they were so young, they went off to war.

I started nursing at nineteen, working with the woman doctor Contessa Craviotta. Her father was a doctor, too. Her husband was Dr. Bennington. He delivered your sister. He had been a doctor overseas during the fighting so he was kind of tough, but he was a good man and a good doctor. He said about you and your brother, "What've you got going having one boy on Groundhog's Day and the other on St. Patrick's Day?"

Your dad named our first two children, the girls. He named Chenel after her two grandmothers, Blanche and Nellie, using half of each name. Our second daughter he named after me, Betty Susan, but she only lived a day. She's buried in the cemetery on Feather River Boulevard in the area with all the little babies. No name was put on the stone because she didn't live a full day.

I knew there was something different about her because she didn't move like Chenel did. When Chenel was born, I hemorrhaged and had to have many transfusions. I wasn't supposed to have a baby so soon so the blood would settle, but the little baby came along. She was buried in a little white casket. Your grandmothers got her a white gown to wear. Dr. Craviotta wouldn't let me go because I was so weak. I cried and cried, but you've got to keep living and I had your sister to think of.

I named you after your grandfathers, and Pat was named by Dr. Craviotta. We were going to name him "John" after your grandfather's brother, but everybody at the hospital wanted to name your brother "Pat" because he was born on St. Patrick's Day. They said I could take him home early if I did and I'm part Irish, so that's the way he was named.

Both of you boys were put in incubators to keep you warm. You were my smallest child. Your Grandpa Kepler wanted you named "Leon" after your dad's older brother that died. Grandpa was going to town with eggs to sell when he turned the car over and Leon died. Your grandma said that Lee never forgave himself for that. Maybe that is why your grandpa was always so hard on your dad. Your grandpa always said you looked like Leon.

Your Grandpa Kepler would show up in his pink Cadillac with a gallon of strawberry ice cream and a big bowl of popcorn. He'd open the ice cream and sit down on the floor with you kids with spoons and ice cream and popcorn. "You're going to give the kids a stomachache," I'd say, but he'd just laugh and say, "Oh, let 'em have fun!" He liked to laugh and have fun. So does your dad, but he never laughed like your grandpa did. I don't know why. Your Grandma Kepler never laughed out loud so much either.

Your dad worked hard to raise you. When Chenel was born, we lived in a little town called Dobbins, up above Marysville in the mountains. We didn't have a refrigerator--we had an ice box that kept the milk and butter cool. Your dad worked construction, driving the dynamite truck. He did that for a while, but your grandpa didn't like him having such a dangerous job, so your dad got a job being a mechanic. He always liked working on cars, and it was something he was good at. He drove trucks for a while but didn't like being away from his family so much, so he settled down to working on cars, something he did all the time he raised you kids. At one time he was number 6 in ranking of all the Ford mechanics in the United States.

Everything we did, we did with you kids--racing go-carts, baseball, camping. We always did it as a family. On Fridays, I'd work all day getting the little travel trailer set up with food and everything we'd need. I'd make macaroni or potato salad. Then your dad would come home with the ice, we'd load up the food and take off for the mountains. Remember how we'd go up to Indian Creek and you boys would fish and float down the creek on your air mattresses? You boys would pitch your army pup tent and sleep outside. Your dad and I and your sister would sleep in the trailer.

One time your sister had a boy come along to camp with us. We were down at the creek, and your sister let that boy eat the whole bowl of potato salad. I said to him, "How could you go and eat the whole thing?" and he said, "Your potato salad is really good!" I was so mad at him! It was our food to eat, after all, but it was kind of funny.

Your dad and your sister fought all the time. They were too much alike, I think. She left home at seventeen, dropped out of high school her last semester. It was such a silly thing to do but she was so angry. She joined the Job Corps, met some tough kids, dropped out, got married, and had your nephew Bobby. Then she divorced. For a long time Chenel and your dad didn't talk, but when she got older, they got along better. She moved to the trailer court across the road when she was told she had six months to live because of cancer. It was all through her body. We were with her at the end. She wanted her family at the end.

I don't know what's going to happen with your dad. Nobody knows when they are going to die. That's something God knows and decides. Your sister asked her minister, "Why did God do this to me?" He said, "God didn't do this. Your body did." That seemed to help her. She always liked to sing. It was her favorite thing in school, and later she sang in the church choir. Your sister had a beautiful voice. Now she's gone, and I don't know about your dad. He's had a long life, and we've done many things together in our sixty-seven years we've shared. I don't know how long I'm going to live! None of us do.

We've just got to try to enjoy life and be good people. Your dad's like a little baby now a lot of the time, and I'm sad that I can't be with him all of the time because he's in a rest home. I'm not strong enough to take care of him, though. I know that. I'm not senile! But if he wants to come home and gets stronger and can stand, I'll bring him home. We'll figure something out.

I don't know what to do. We've spent so many years together. I guess I've just got to put it all in God's hands.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on July 24, 2013 04:00

July 22, 2013

The New "Who is John Galt?" Eponymously Anonymous J.K. Rowling

© Debra Hurford Brown"Who is John Galt?" was the cryptic question written on walls in Ayn Rand's novel Atlas Shrugged.

© Debra Hurford Brown"Who is John Galt?" was the cryptic question written on walls in Ayn Rand's novel Atlas Shrugged.Galt in Rand's novel is a creative and highly independent individual who becomes the ideological center of the novel's theme of self-sufficiency and freedom. Throughout the novel the question is asked, building to the climax of the novel.

Perhaps J.K. Rowling's name will come to represent that for independent publishers. With her publishing of The Cuckoo's Calling under a pseudonym and subsequent "outing," her novel has shot from relative obscurity to super-fame. Has Rowling betrayed women? Is Rowling's experience in any way instructional for the struggling and obscure writer? Was the project a marketing ploy or really an attempt by Rowling for a brief time of liberating obscurity?

Writers' website and blog Indies Unlimited posted a wryly humorous and timely article entitled "Chris James: I admit J.K. Rowling wrote my books." Later in the article is the revelation that Stephen King has fessed up that he actually is J.K. Rowling. So , let's see . . . that means that actually Stephen King wrote Chris James' books!

This should be the clarion call for all independent, self-publishing authors. We are undiscovered J.K. Rowlings. We are all graduates of Hogwarts and are never muggles. We all have a lightning scar/tattoo. Agent Tom Riddle just turned down our manuscript. We write our interrogatory manifesto on subway walls.

"J.K. Rowling wrote my books."

"I am J.K. Rowling."

Here are some suggestions to pump ourselves up with ink rather than accidie.

All "About" pages on our webs should include one of the above two quotations. Oh, WTF, use both!Dedications for our books should be to J.K., including one of the above quotations.Book signings should mention one of the above.We should add J.K. to our business checking accounts (any maybe she will add us to hers).Photoshopping J.K. and us together should be a no-brainer for marketing."Like" J.K.'s Facebook page (I just did) and post on her wall regularly. Name-drop J.K. Rowling regularly in your blog posts to increase the hits your page gets.But, by all means, persevere as she did, wish for support of nature, and accept your success with as much grace and dignity as she.We are all of one family, and finally we have discovered that family's common name--Rowling. Maybe my next novel will be Rowling Shrugged.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on July 22, 2013 14:22

July 18, 2013

A Day Out with Mom #8: dialoguing with Dad

"Where are we?"

"Where are we?""What do you mean, Dad? What town or what place?"

"What town. We're in Oceanside, right?"

"No, Dad, we're in Oroville."

"We've got a place just the other side of the hill, right over there."

"You mean the old place by the river?"

"No, the place by the ocean."

"That was a long time ago, when you were living with your parents."

"Oh. So where are we living now?"

"In Oroville in a mobile home."

"OK, so let's go home."

"We can't. You're too weak for us to take care of. You need to eat and exercise and get stronger. Then we can take you home."

"I'll do that after I get home."

"You need to get stronger here. We can't take care of you at home."

"I could walk when I came here. They're taking my good food and giving me crap food. That's why I'm so weak."

"You came here because you had pneumonia and were in the hospital. Then you couldn't walk. That's why you're here, to get strong. What you need to do is eat, rest, exercise and get strong again."

"I'm just sitting here, waiting to die. I can do that at home."

"We can't take care of you at home."

"You're trying to take over. Why don't you admit the truth!"

"Mom's heart is too weak. Taking care of you is too much the way you are."

"You're trying to take my money! You've got my wallet. Some son you are!"

"Mom has it in her purse."

"Good, then let's get going."

"Good-bye, Dad. You rest."

"Why's she leaving? She's my wife. She should be with me!"

"You rest and eat. Good-bye."

"You shut up, goddammit! This is all your doing."

"Good-bye, Dad."

"Don't say good-bye. See ya later."

"See ya later."

"Wait, damnit! Take me with you!"

"I'm trying to take care of both of you. We have to go now."

"You take care of your mother. You take care of her."

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on July 18, 2013 04:00

A Day Out with Mom #7: dialoguing with Dad

"Where are we?"

"Where are we?""What do you mean, Dad? What town or what place?"

"What town. We're in Oceanside, right?"

"No, Dad, we're in Oroville."

"We've got a place just the other side of the hill, right over there."

"You mean the old place by the river?"

"No, the place by the ocean."

"That was a long time ago, when you were living with your parents."

"Oh. So where are we living now?"

"In Oroville in a mobile home."

"OK, so let's go home."

"We can't. You're too weak for us to take care of. You need to eat and exercise and get stronger. Then we can take you home."

"I'll do that after I get home."

"You need to get stronger here. We can't take care of you at home."

"I could walk when I came here. They're taking my good food and giving me crap food. That's why I'm so weak."

"You came here because you had pneumonia and were in the hospital. Then you couldn't walk. That's why you're here, to get strong. What you need to do is eat, rest, exercise and get strong again."

"I'm just sitting here, waiting to die. I can do that at home."

"We can't take care of you at home."

"You're trying to take over. Why don't you admit the truth!"

"Mom's heart is too weak. Taking care of you is too much the way you are."

"You're trying to take my money! You've got my wallet. Some son you are!"

"Mom has it in her purse."

"Good, then let's get going."

"Good-bye, Dad. You rest."

"Why's she leaving? She's my wife. She should be with me!"

"You rest and eat. Good-bye."

"You shut up, goddammit! This is all your doing."

"Good-bye, Dad."

"Don't say good-bye. See ya later."

"See ya later."

"Wait, damnit! Take me with you!"

"I'm trying to take care of both of you. We have to go now."

"You take care of your mother. You take care of her."

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on July 18, 2013 04:00

July 16, 2013

Writing Tips from an Award-winning Travel Writer Laurie Gough

It was the eye-catching images and the interesting content that caught my attention--and then the experience-based wisdom that kept me reading.

It was the eye-catching images and the interesting content that caught my attention--and then the experience-based wisdom that kept me reading. From Laurie Gough's webpage bio:

"Lauded by Time magazine as "one of the new generation of intrepid female travel writers," Laurie Gough is author of Kiss the Sunset Pig, and Kite Strings of the Southern Cross, shortlisted for the Thomas Cook Travel Book Award, and silver medal winner of ForeWord Magazine's Travel Book of the Year in the US. Twenty of her stories have been anthologized in various literary travel books."On her site's webpage "Passions," she lists "Travel Writing Tips." I think they are useful for all writers to consider and am listing them in a condensed version below. Check out her page for the full story. Actually, just check out her website--the stories, the photos, and the efficient, effective presentation of Laurie Gough's work are all worth studying.

Travel Writing TipsFocus on interesting, different, and special qualities. "Usually this will be a combination of the place and the people."Concrete details: "not 'fruit' but 'rotting pomegranates.'""Stay true to who you are." Let the readers find out as you go along.Open your senses to the small things: oil-burning lamps, newly cut timber, cricket chirps . . .Characterization: "How human beings are acting on this planet never fails to enliven a story."Find the good, even in the lousy.Backstory: history, facts, past events."Read your work aloud to yourself."Tone/mood:"take in as much of a place as you can."The common saying for this is to "capture the place with words." I see little difference if that place is actual or imaginary. It's our job as writers to make it real.

Laurie Gough website: "where the passions of travel and writing meet and walk down the road together."

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved.

Published on July 16, 2013 04:00

July 13, 2013

A Day Out with Mom #7: the story of blindness in her life

Greyhart PhotographyWhen I was eight years old, some kids and I were playing in the barn and an older girl swung a rope that had strands of wires woven in it. It hit me in the eyes, cutting them. I was blind.

Greyhart PhotographyWhen I was eight years old, some kids and I were playing in the barn and an older girl swung a rope that had strands of wires woven in it. It hit me in the eyes, cutting them. I was blind.My parents took me to San Francisco where my eyes were operated on. That kind of thing was not common back then. I came home, and my mom told me I would never see. I told her after a while that I could see shapes and colors, but she said I was just imagining it. I was right, though, and I gained some of my sight back. The doctors were happy but told me it probably wouldn't last, and now here I am finding life hard because I can't see so good.

I had to wear glasses, and they were thick like Coke bottles. One boy at our school in Morris Ravine was from Oklahoma. He was bigger and older than me, and he kept calling me Four-Eyes. He just wouldn't stop, so I clobbered him and he never called me that again. I was just a tiny thing, too. Remember, when I married at twenty-six, I was just five feet tall and ninety-eight pounds.

PanoramioKids were a lot tougher in those days, living through the Depression. Kids these days--a lot of them couldn't take it. I went to school through the eighth grade in a one-room school house in Morris Ravine. The kids lived on or around Table Mountain and down by the river, some of them in tents.

PanoramioKids were a lot tougher in those days, living through the Depression. Kids these days--a lot of them couldn't take it. I went to school through the eighth grade in a one-room school house in Morris Ravine. The kids lived on or around Table Mountain and down by the river, some of them in tents. My dad would take some of the greens that he fed the rabbits he raised and take them and other food down to the tents so the people would have greens and wouldn't get the gout. He chopped firewood for the school to keep it warm. It had a pot-bellied stove, and every morning the teacher would start her day by putting on a pot of beans that was part of our lunch. Dad also brought gravel to put in front of the school so the kids could play outside on rainy days and not get muddy.

I never drove, even though I took the written test and got a one hundred percent. My eyes were just too bad. I liked to draw, though, and was good, and I liked to sew. After graduating, I became a Practical Nurse. You had to take a test to get a certificate from the state of California. Years later, Dr. Boom sat me down and just chewed me out because I didn't become a Registered Nurse. I just raised you kids, though, and now I'm too old and my eyes are bad. I'm eighty-eight years old now and too old to go back to nursing. I just can't see.

I worked as a nurse during World War II in the county hospital. I did a lot of different things, but my favorite was working with the babies. That's where I learned everything I needed to know to take care of you kids. I always made sure you got your shots, too.

There were babies who came to us all dirty and uncared for. Back then, there were still parents who weren't good and didn't care or who didn't know any better. We took care of them all. I was still working there when I met your dad. The other nurses gave me a ride to work, since I couldn't drive. All you kids were delivered by Dr. Craviotta, a woman doctor. There weren't many of them back then.

Now my eyes are getting worse and worse, just like the doctors said. I'd be able to do a lot more if I could see better. There are things I can't do that I used to. You just have to keep doing what you can, though, and not give up. I do a lot by touch.

It's sad getting old, but I keep doing things. I've worked all my life. My parents adopted me by paying a man from the state who came around with kids in a wagon. It was a lot different back then. They were my parents, though. They loved me and cared for me. We didn't have a lot of money, but we had more than some. We shared what we had to help others get by.

That's what people did back then, and that's how I tried to raise you kids. It's a different world now. People seem to always be going a lot faster and don't take time to rest. Some things don't change, though, and those are the things I tried to teach you.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on July 13, 2013 04:00

A Day Out with Mom #6: the story of blindness in her life

Greyhart PhotographyWhen I was eight years old, some kids and I were playing in the barn and an older girl swung a rope that had strands of wires woven in it. It hit me in the eyes, cutting them. I was blind.

Greyhart PhotographyWhen I was eight years old, some kids and I were playing in the barn and an older girl swung a rope that had strands of wires woven in it. It hit me in the eyes, cutting them. I was blind.My parents took me to San Francisco where my eyes were operated on. That kind of thing was not common back then. I came home, and my mom told me I would never see. I told her after a while that I could see shapes and colors, but she said I was just imagining it. I was right, though, and I gained some of my sight back. The doctors were happy but told me it probably wouldn't last, and now here I am finding life hard because I can't see so good.

I had to wear glasses, and they were thick like Coke bottles. One boy at our school in Morris Ravine was from Oklahoma. He was bigger and older than me, and he kept calling me Four-Eyes. He just wouldn't stop, so I clobbered him and he never called me that again. I was just a tiny thing, too. Remember, when I married at twenty-six, I was just five feet tall and ninety-eight pounds.

PanoramioKids were a lot tougher in those days, living through the Depression. Kids these days--a lot of them couldn't take it. I went to school through the eighth grade in a one-room school house in Morris Ravine. The kids lived on or around Table Mountain and down by the river, some of them in tents.

PanoramioKids were a lot tougher in those days, living through the Depression. Kids these days--a lot of them couldn't take it. I went to school through the eighth grade in a one-room school house in Morris Ravine. The kids lived on or around Table Mountain and down by the river, some of them in tents. My dad would take some of the greens that he fed the rabbits he raised and take them and other food down to the tents so the people would have greens and wouldn't get the gout. He chopped firewood for the school to keep it warm. It had a pot-bellied stove, and every morning the teacher would start her day by putting on a pot of beans that was part of our lunch. Dad also brought gravel to put in front of the school so the kids could play outside on rainy days and not get muddy.

I never drove, even though I took the written test and got a one hundred percent. My eyes were just too bad. I liked to draw, though, and was good, and I liked to sew. After graduating, I became a Practical Nurse. You had to take a test to get a certificate from the state of California. Years later, Dr. Boom sat me down and just chewed me out because I didn't become a Registered Nurse. I just raised you kids, though, and now I'm too old and my eyes are bad. I'm eighty-eight years old now and too old to go back to nursing. I just can't see.

I worked as a nurse during World War II in the county hospital. I did a lot of different things, but my favorite was working with the babies. That's where I learned everything I needed to know to take care of you kids. I always made sure you got your shots, too.

There were babies who came to us all dirty and uncared for. Back then, there were still parents who weren't good and didn't care or who didn't know any better. We took care of them all. I was still working there when I met your dad. The other nurses gave me a ride to work, since I couldn't drive. All you kids were delivered by Dr. Craviotta, a woman doctor. There weren't many of them back then.

Now my eyes are getting worse and worse, just like the doctors said. I'd be able to do a lot more if I could see better. There are things I can't do that I used to. You just have to keep doing what you can, though, and not give up. I do a lot by touch.

It's sad getting old, but I keep doing things. I've worked all my life. My parents adopted me by paying a man from the state who came around with kids in a wagon. It was a lot different back then. They were my parents, though. They loved me and cared for me. We didn't have a lot of money, but we had more than some. We shared what we had to help others get by.

That's what people did back then, and that's how I tried to raise you kids. It's a different world now. People seem to always be going a lot faster and don't take time to rest. Some things don't change, though, and those are the things I tried to teach you.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on July 13, 2013 04:00