Tom Kepler's Blog, page 23

August 24, 2013

If No One Reviews Your Book, Did Anyone Really Read It?

In the month of July, twenty-five e-book copies of I Write: Being & Writing and twenty-two copies of Who Listens to Dragons, Three Stories were downloaded during the July book promotion at Smashwords.

In the month of July, twenty-five e-book copies of I Write: Being & Writing and twenty-two copies of Who Listens to Dragons, Three Stories were downloaded during the July book promotion at Smashwords.The idea is that the free books would be market leaders that draw readers to buy other books by me. For instance, my e-book Who Listens to Dragons, Three Stories now sells for $0.99, the low price seeking to lead readers to the higher priced novel, The Stone Dragon, which is set in the same fantasy universe.

All readers who downloaded my books are kindly urged to review them.

Even bad reviews can lead to more sales. My young adult novel, Love Ya Like a Sister, was reviewed and given a "one star" rating, and later I was asked via email what I thought of the review. I wrote back that as an author, my opinion was not important, but as a career school teacher, some of the comments in the review were naive. These comments were ones such as "Events in the novel might give kids ideas" and "Kids don't really talk like that."

As a 30-year teaching professional, I've heard and had been told all kinds of things. In the novel, I didn't need to make up anything that might not really happen. The reviewer felt I was offended and removed the review from online. I was disappointed, actually. Would a one-star review saying, "Young people wouldn't really do those kinds of things," and "We don't want to give kids ideas" hurt sales? I don't really think so. The review revealed as much about the reviewer as the novel, and such comments certainly can pique the curiosity.

I'll be interested in how many reviews result from my participation in the Smashwords promotion. Although promotion can take time before the pay-off delivers, I'd like to think that there is some objective way to measure the success of giving my books away for free.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on August 24, 2013 04:00

August 22, 2013

A Day Out with Mom #15: my father, the storyteller

A master journeyman automobile mechanic, my father was a storyteller and a teller of jokes. My older sister and younger brother followed his example. I, the quiet middle child, became the writer, the witness, the reporter. I followed my own path but still inherited his love of words. Below is one of my dad's stories.

This video was originally posted in 2009 when my father was 89 years old. I wanted to post it now to provide a balance to his challenges that face him at 93 years of age. To use a comparison from my dad's life as a mechanic, we cannot determine how beautiful and useful a car was during its time by just evaluating its last years, worn and battered from its duty.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

This video was originally posted in 2009 when my father was 89 years old. I wanted to post it now to provide a balance to his challenges that face him at 93 years of age. To use a comparison from my dad's life as a mechanic, we cannot determine how beautiful and useful a car was during its time by just evaluating its last years, worn and battered from its duty.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on August 22, 2013 04:00

August 20, 2013

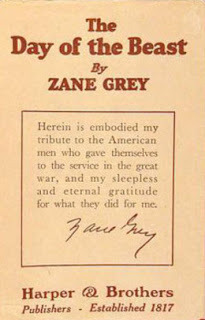

Book Review: The Day of the Beast

The Day of the Beast is the darkest novel that I've read by Zane Grey. It is also the least enjoyable.

The Day of the Beast is the darkest novel that I've read by Zane Grey. It is also the least enjoyable.I believe, though, that Grey did not write the novel to please but to educate his readers as to what had gone wrong with American society, and that is the novel's downfall. Through dialogue, character introspection, and downright direct statement, Grey's philosophy interferes with the advancement of the novel. He tells rather than shows, leaving little for the reader to ponder or discover.

The basic storyline is that a soldier, wounded in World War I, returns home to find the people he knew and the society within which he was raised changed for the worse. The details of his Post-traumatic Stress Disorder are that he cannot reintegrate or accept the change--or even "agree to disagree" with the changes. Going to battle with the societal changes of a nation . . . well, guess who loses in the end, which is the basis of the novel's darkness.

There are some good action passages which display Grey at his strongest, most notably one fight scene and descriptions of a snowstorm and of a river in flood. These scenes are too few and far between, though.

If you read The Day of the Beast, it is best to read it as an historic artifact. Grey's use of the term "slacker" is one instance. His description of jazz music from a conservative perspective is another. The presence of prejudice that is common in Grey's novels exists in this novel as in his others but is not primarily racial or ethnic; in this case, rather, it is based on wealth. Ironically, that prejudice is turned upside down with his premise that those who should know better are not showing the wisdom that they should possess by virtue of education and refinement. Those in poverty the author assumes it reasonable to be more base and immoral.

The greatest prejudice is gender-based with Grey's considerations of what women "are" and how they have fallen from that pedestal. This is serious stuff--the role of women in upholding the pillars of society and the role of men in honoring that role of women as the foundational essence of civilization. As usual, though, Grey's application of the abstract to the specific ends in the formation of two-dimensional characters when interesting three-dimensional characters were possible.

Grey lived in and wrote about a time of great change in America, if this can be said without demeaning the great change that takes place in any and every era. In retrospect, Grey did not quite get it right. However, as with all his novels, his assignation of personal responsibility to live life in accord with the highest principles is spot-on. The bad guys are the "slackers," the specific term Grey uses, those who act according to their small desires without regard for their greater selves or for others. Those who are the established social order who allow this to happen are equally to blame in Grey's viewpoint.

Denying personal responsibility because of social complacency is a great sin, according to Grey. We must do right even when the circumstances do not directly touch our lives. When change, though, is the nature of the world and evolution requires that circumstances change, deciding and acting can be tough. Grey's limitation was that he did not see what structures in society needed to change. His vision that was spot-on, though, was that causing others pain and suffering in order to gratify one's personal pleasure is wrong.

Two keys to enjoying Grey's novels are to focus on the selflessness of his protagonists and to accept that he was a writer and not a prophet. The fact that some writers are prophets provides a perspective for Grey's writing. His vision is true to his time--timeless in some aspects and tragically limited in others. I am tempted to go and read the beginning of Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times . . ."

The great weakness of this novel is structured in its original intent: "Herein is embodied my tribute to the American men who gave themselves to the service in the great war, and my sleepless and eternal gratitude for what they did for me." Too much tribute, too little novel--or, to put it in another way--Grey focused so much on his "tribute" that he was not successful in truly "embodying" his concept. To me as a writer, if the novel was not enjoyable, it certainly was educational.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on August 20, 2013 04:00

August 16, 2013

A Day Out with Mom #14: going to school

I went up through the eighth grade to a one-room school called Morris Ravine on Table Mountain. It usually had about ten kids but once got up to around twenty when a family showed up with eight kids. When that happened, the older students helped teach the younger ones. I had to be pretty tough because a lot of the kids were from the families living in tents along the Feather River.

Our first teacher was ninety years old. I think maybe she wore a wig, but she'd push her glasses up on her head and then forget they were there and go around looking for them. Sometimes she'd fall asleep in class. Then we older students would help her so things wouldn't get too wild.

There were two brothers, Leo and Haskell McInturf who were real ornery. Haskell used to peek at us when we were in the outhouse. It was kept clean with disinfectant, but there were holes where the knots had fallen out of the wood. I took can lids out one day, nailed them over the holes, and said, "There! Now you won't be doing any more peeping." They were younger than me, and I was one of the three eighth grade girls that helped teach them.

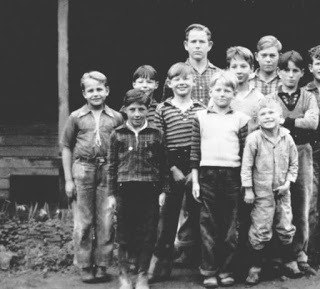

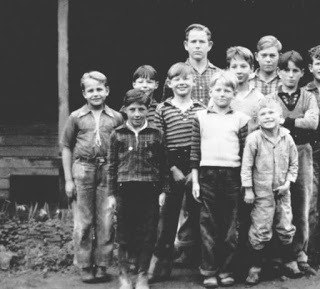

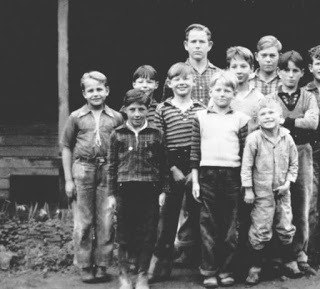

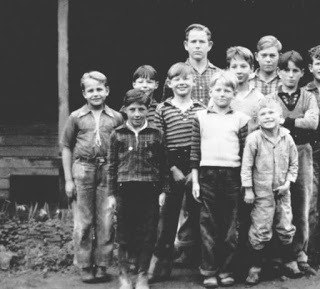

CSU Archive. Leo & Haskell far left and right. My uncle, 2nd from the right. (Link to full photo.)Leo was a paratrooper in the army during the war. He'd jump out of airplanes and did that in Germany and was there when Hitler died. I told him later, "I didn't think you'd have the guts to do that." After the war he came back and became a state highway patrolman. One day he pulled up to the house and got out. "What are you going to do, arrest me?" I asked. "Oh, Betty, don't say that. I just want to tell you I'll never forget how you taught me when I was young." We hugged before he left.

CSU Archive. Leo & Haskell far left and right. My uncle, 2nd from the right. (Link to full photo.)Leo was a paratrooper in the army during the war. He'd jump out of airplanes and did that in Germany and was there when Hitler died. I told him later, "I didn't think you'd have the guts to do that." After the war he came back and became a state highway patrolman. One day he pulled up to the house and got out. "What are you going to do, arrest me?" I asked. "Oh, Betty, don't say that. I just want to tell you I'll never forget how you taught me when I was young." We hugged before he left.

Leo and Haskell's dad was a miner at the Lucky 7 mine. They didn't pay much for such dangerous work. My dad worked there, too. Once there was a cave-in, and we went up to the mine and waited to see if they'd get out. They finally did, and my dad said, "I'm never going down in that hole again," and he didn't.

Us kids would come over the mountain to the school sometimes when we couldn't get a ride. I'd wear my jeans and my clodhoppers when I'd do that. That's what we called those big-soled shoes. Anyway, the McInturf boys bought their dad a house when he was old. That was the nicest thing. They also donated land that was used to build a senior citizen center after they passed away. Haskell, you know, went on to be a wood shop teacher at Oroville High. Both you and your brother had him.

After my first teacher retired, we got Mrs. Mooney. She was a no-nonsense teacher but cared for her students. She had a new car and would sometimes give the kids rides. "No, just sit there and don't move," she'd say. She didn't want that car getting messed up. Mrs. Mooney didn't dress sexy or anything like that. They didn't pay teachers much back then. She was just a regular person and a good teacher. Later she had kids. They wouldn't let a teacher teach if she was pregnant. Things were a lot different back then.

CSU Archive. Mrs. Mooney far right. There were only three girls in the eighth grade when I graduated, no boys! A person from the department of education came and gave us tests. You had to pass to be able to go to high school. I got an "A" on the constitution part.

CSU Archive. Mrs. Mooney far right. There were only three girls in the eighth grade when I graduated, no boys! A person from the department of education came and gave us tests. You had to pass to be able to go to high school. I got an "A" on the constitution part.

My cousin Mary didn't want to give the graduating speech and neither did the other girl, so Miss Mooney said, "Betty, you're going to give the speech." I knew how to make an outline, and I did the speech on conservation, on conserving nature in the area around the river and mountain and school. You two boys gave speeches, too, when you graduated. Everybody clapped and cheered when I finished. My mom said, "I didn't know you could do that."

When I went to high school, it was such a pretty building. It was so big, though. I had a hard time because I couldn't see well. I had glasses that were thick like the ends of Coke bottles and with leather on the sides. Some of the teachers would help me and some wouldn't. Mr. Nesbit, the principal, went around to all the teachers and told them that I had to have my assignments written out big so that I could see. Some wouldn't do it. They didn't do so much for kids who had difficulties back then. My cousin Mary said, "If they won't do it, then I will," and she took notes for me and wrote on the blackboard for me.

When I graduated in 1944, there should have been about two hundred students, but there were only about seventy because all the boys had gone to war. We graduated at the State Theater, and I was worried about climbing the steps to get my diploma. I wanted to do it by myself, though, and I did. When I got my diploma, Mr. Nesbit hugged me and told the audience, "Betty can't see very well, but she's a good student and a fighter." He was a nice man and cared for his students.

After I graduated, Mom didn't want me to work because of my eyes. My aunts were nurses, though, and I talked to them and they helped me. Then I went to the county hospital and applied for a job as a Practical Nurse. On my first day of work, I dressed and Mom said, "What are you doing?" I told her, "I've got a job," and that was that.

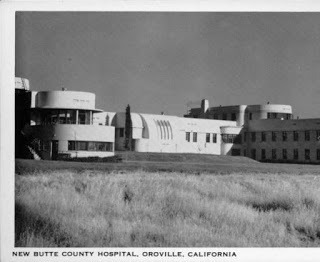

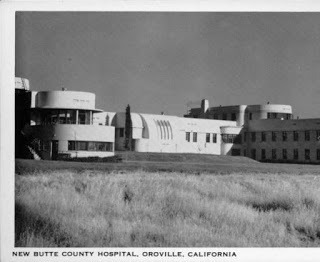

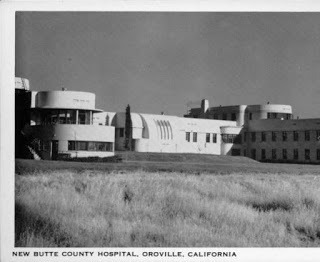

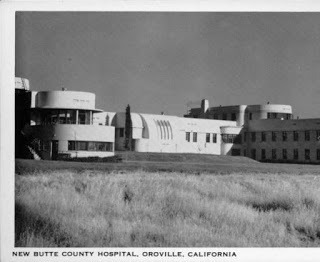

CSU Archive. Butte County Hospital when new.Later, after I married and your dad wanted me to stay home and raise you kids, Dr. Boom came over and chewed me out. He was a refined man, but he said, "What in the hell do you mean, Betty, you aren't going to take the test to become a licensed vocational nurse?" I only weighed ninety-eight pounds, but I was fast and efficient. Being a nurse was good learning for being a mother, though.

CSU Archive. Butte County Hospital when new.Later, after I married and your dad wanted me to stay home and raise you kids, Dr. Boom came over and chewed me out. He was a refined man, but he said, "What in the hell do you mean, Betty, you aren't going to take the test to become a licensed vocational nurse?" I only weighed ninety-eight pounds, but I was fast and efficient. Being a nurse was good learning for being a mother, though.

I grew up being blind for a time and then not seeing well for my whole life. Now I can't see again. I can't hear so well, either. I spent my whole life not giving up, though, and that's helping me now. It's like Mr. Nesbit said--I'm a fighter. Just because you're quiet doesn't mean you're weak, and just because you're loud doesn't mean you're strong. Silent waters run deep.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Our first teacher was ninety years old. I think maybe she wore a wig, but she'd push her glasses up on her head and then forget they were there and go around looking for them. Sometimes she'd fall asleep in class. Then we older students would help her so things wouldn't get too wild.

There were two brothers, Leo and Haskell McInturf who were real ornery. Haskell used to peek at us when we were in the outhouse. It was kept clean with disinfectant, but there were holes where the knots had fallen out of the wood. I took can lids out one day, nailed them over the holes, and said, "There! Now you won't be doing any more peeping." They were younger than me, and I was one of the three eighth grade girls that helped teach them.

CSU Archive. Leo & Haskell far left and right. My uncle, 2nd from the right. (Link to full photo.)Leo was a paratrooper in the army during the war. He'd jump out of airplanes and did that in Germany and was there when Hitler died. I told him later, "I didn't think you'd have the guts to do that." After the war he came back and became a state highway patrolman. One day he pulled up to the house and got out. "What are you going to do, arrest me?" I asked. "Oh, Betty, don't say that. I just want to tell you I'll never forget how you taught me when I was young." We hugged before he left.

CSU Archive. Leo & Haskell far left and right. My uncle, 2nd from the right. (Link to full photo.)Leo was a paratrooper in the army during the war. He'd jump out of airplanes and did that in Germany and was there when Hitler died. I told him later, "I didn't think you'd have the guts to do that." After the war he came back and became a state highway patrolman. One day he pulled up to the house and got out. "What are you going to do, arrest me?" I asked. "Oh, Betty, don't say that. I just want to tell you I'll never forget how you taught me when I was young." We hugged before he left.Leo and Haskell's dad was a miner at the Lucky 7 mine. They didn't pay much for such dangerous work. My dad worked there, too. Once there was a cave-in, and we went up to the mine and waited to see if they'd get out. They finally did, and my dad said, "I'm never going down in that hole again," and he didn't.

Us kids would come over the mountain to the school sometimes when we couldn't get a ride. I'd wear my jeans and my clodhoppers when I'd do that. That's what we called those big-soled shoes. Anyway, the McInturf boys bought their dad a house when he was old. That was the nicest thing. They also donated land that was used to build a senior citizen center after they passed away. Haskell, you know, went on to be a wood shop teacher at Oroville High. Both you and your brother had him.

After my first teacher retired, we got Mrs. Mooney. She was a no-nonsense teacher but cared for her students. She had a new car and would sometimes give the kids rides. "No, just sit there and don't move," she'd say. She didn't want that car getting messed up. Mrs. Mooney didn't dress sexy or anything like that. They didn't pay teachers much back then. She was just a regular person and a good teacher. Later she had kids. They wouldn't let a teacher teach if she was pregnant. Things were a lot different back then.

CSU Archive. Mrs. Mooney far right. There were only three girls in the eighth grade when I graduated, no boys! A person from the department of education came and gave us tests. You had to pass to be able to go to high school. I got an "A" on the constitution part.

CSU Archive. Mrs. Mooney far right. There were only three girls in the eighth grade when I graduated, no boys! A person from the department of education came and gave us tests. You had to pass to be able to go to high school. I got an "A" on the constitution part.My cousin Mary didn't want to give the graduating speech and neither did the other girl, so Miss Mooney said, "Betty, you're going to give the speech." I knew how to make an outline, and I did the speech on conservation, on conserving nature in the area around the river and mountain and school. You two boys gave speeches, too, when you graduated. Everybody clapped and cheered when I finished. My mom said, "I didn't know you could do that."

When I went to high school, it was such a pretty building. It was so big, though. I had a hard time because I couldn't see well. I had glasses that were thick like the ends of Coke bottles and with leather on the sides. Some of the teachers would help me and some wouldn't. Mr. Nesbit, the principal, went around to all the teachers and told them that I had to have my assignments written out big so that I could see. Some wouldn't do it. They didn't do so much for kids who had difficulties back then. My cousin Mary said, "If they won't do it, then I will," and she took notes for me and wrote on the blackboard for me.

When I graduated in 1944, there should have been about two hundred students, but there were only about seventy because all the boys had gone to war. We graduated at the State Theater, and I was worried about climbing the steps to get my diploma. I wanted to do it by myself, though, and I did. When I got my diploma, Mr. Nesbit hugged me and told the audience, "Betty can't see very well, but she's a good student and a fighter." He was a nice man and cared for his students.

After I graduated, Mom didn't want me to work because of my eyes. My aunts were nurses, though, and I talked to them and they helped me. Then I went to the county hospital and applied for a job as a Practical Nurse. On my first day of work, I dressed and Mom said, "What are you doing?" I told her, "I've got a job," and that was that.

CSU Archive. Butte County Hospital when new.Later, after I married and your dad wanted me to stay home and raise you kids, Dr. Boom came over and chewed me out. He was a refined man, but he said, "What in the hell do you mean, Betty, you aren't going to take the test to become a licensed vocational nurse?" I only weighed ninety-eight pounds, but I was fast and efficient. Being a nurse was good learning for being a mother, though.

CSU Archive. Butte County Hospital when new.Later, after I married and your dad wanted me to stay home and raise you kids, Dr. Boom came over and chewed me out. He was a refined man, but he said, "What in the hell do you mean, Betty, you aren't going to take the test to become a licensed vocational nurse?" I only weighed ninety-eight pounds, but I was fast and efficient. Being a nurse was good learning for being a mother, though. I grew up being blind for a time and then not seeing well for my whole life. Now I can't see again. I can't hear so well, either. I spent my whole life not giving up, though, and that's helping me now. It's like Mr. Nesbit said--I'm a fighter. Just because you're quiet doesn't mean you're weak, and just because you're loud doesn't mean you're strong. Silent waters run deep.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on August 16, 2013 21:07

A Day Out with Mom: going to school

I went up through the eighth grade to a one-room school called Morris Ravine on Table Mountain. It usually had about ten kids but once got up to around twenty when a family showed up with eight kids. When that happened, the older students helped teach the younger ones. I had to be pretty tough because a lot of the kids were from the families living in tents along the Feather River.

Our first teacher was ninety years old. I think maybe she wore a wig, but she'd push her glasses up on her head and then forget they were there and go around looking for them. Sometimes she'd fall asleep in class. Then we older students would help her so things wouldn't get too wild.

There were two brothers, Leo and Haskell McInturf who were real ornery. Haskell used to peek at us when we were in the outhouse. It was kept clean with disinfectant, but there were holes where the knots had fallen out of the wood. I took can lids out one day, nailed them over the holes, and said, "There! Now you won't be doing any more peeping." They were younger than me, and I was one of the three eighth grade girls that helped teach them.

CSU Archive. Leo & Haskell far left and right. My uncle, 2nd from the right. (Link to full photo.)Leo was a paratrooper in the army during the war. He'd jump out of airplanes and did that in Germany and was there when Hitler died. I told him later, "I didn't think you'd have the guts to do that." After the war he came back and became a state highway patrolman. One day he pulled up to the house and got out. "What are you going to do, arrest me?" I asked. "Oh, Betty, don't say that. I just want to tell you I'll never forget how you taught me when I was young." We hugged before he left.

CSU Archive. Leo & Haskell far left and right. My uncle, 2nd from the right. (Link to full photo.)Leo was a paratrooper in the army during the war. He'd jump out of airplanes and did that in Germany and was there when Hitler died. I told him later, "I didn't think you'd have the guts to do that." After the war he came back and became a state highway patrolman. One day he pulled up to the house and got out. "What are you going to do, arrest me?" I asked. "Oh, Betty, don't say that. I just want to tell you I'll never forget how you taught me when I was young." We hugged before he left.

Leo and Haskell's dad was a miner at the Lucky 7 mine. They didn't pay much for such dangerous work. My dad worked there, too. Once there was a cave-in, and we went up to the mine and waited to see if they'd get out. They finally did, and my dad said, "I'm never going down in that hole again," and he didn't.

Us kids would come over the mountain to the school sometimes when we couldn't get a ride. I'd wear my jeans and my clodhoppers when I'd do that. That's what we called those big-soled shoes. Anyway, the McInturf boys bought their dad a house when he was old. That was the nicest thing. They also donated land that was used to build a senior citizen center after they passed away. Haskell, you know, went on to be a wood shop teacher at Oroville High. Both you and your brother had him.

After my first teacher retired, we got Mrs. Mooney. She was a no-nonsense teacher but cared for her students. She had a new car and would sometimes give the kids rides. "No, just sit there and don't move," she'd say. She didn't want that car getting messed up. Mrs. Mooney didn't dress sexy or anything like that. They didn't pay teachers much back then. She was just a regular person and a good teacher. Later she had kids. They wouldn't let a teacher teach if she was pregnant. Things were a lot different back then.

CSU Archive. Mrs. Mooney far right. There were only three girls in the eighth grade when I graduated, no boys! A person from the department of education came and gave us tests. You had to pass to be able to go to high school. I got an "A" on the constitution part.

CSU Archive. Mrs. Mooney far right. There were only three girls in the eighth grade when I graduated, no boys! A person from the department of education came and gave us tests. You had to pass to be able to go to high school. I got an "A" on the constitution part.

My cousin Mary didn't want to give the graduating speech and neither did the other girl, so Miss Mooney said, "Betty, you're going to give the speech." I knew how to make an outline, and I did the speech on conservation, on conserving nature in the area around the river and mountain and school. You two boys gave speeches, too, when you graduated. Everybody clapped and cheered when I finished. My mom said, "I didn't know you could do that."

When I went to high school, it was such a pretty building. It was so big, though. I had a hard time because I couldn't see well. I had glasses that were thick like the ends of Coke bottles and with leather on the sides. Some of the teachers would help me and some wouldn't. Mr. Nesbit, the principal, went around to all the teachers and told them that I had to have my assignments written out big so that I could see. Some wouldn't do it. They didn't do so much for kids who had difficulties back then. My cousin Mary said, "If they won't do it, then I will," and she took notes for me and wrote on the blackboard for me.

When I graduated in 1944, there should have been about two hundred students, but there were only about seventy because all the boys had gone to war. We graduated at the State Theater, and I was worried about climbing the steps to get my diploma. I wanted to do it by myself, though, and I did. When I got my diploma, Mr. Nesbit hugged me and told the audience, "Betty can't see very well, but she's a good student and a fighter." He was a nice man and cared for his students.

After I graduated, Mom didn't want me to work because of my eyes. My aunts were nurses, though, and I talked to them and they helped me. Then I went to the county hospital and applied for a job as a Practical Nurse. On my first day of work, I dressed and Mom said, "What are you doing?" I told her, "I've got a job," and that was that.

CSU Archive. Butte County Hospital when new.Later, after I married and your dad wanted me to stay home and raise you kids, Dr. Boom came over and chewed me out. He was a refined man, but he said, "What in the hell do you mean, Betty, you aren't going to take the test to become a licensed vocational nurse?" I only weighed ninety-eight pounds, but I was fast and efficient. Being a nurse was good learning for being a mother, though.

CSU Archive. Butte County Hospital when new.Later, after I married and your dad wanted me to stay home and raise you kids, Dr. Boom came over and chewed me out. He was a refined man, but he said, "What in the hell do you mean, Betty, you aren't going to take the test to become a licensed vocational nurse?" I only weighed ninety-eight pounds, but I was fast and efficient. Being a nurse was good learning for being a mother, though.

I grew up being blind for a time and then not seeing well for my whole life. Now I can't see again. I can't hear so well, either. I spent my whole life not giving up, though, and that's helping me now. It's like Mr. Nesbit said--I'm a fighter. Just because you're quiet doesn't mean you're weak, and just because you're loud doesn't mean you're strong. Silent waters run deep.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Our first teacher was ninety years old. I think maybe she wore a wig, but she'd push her glasses up on her head and then forget they were there and go around looking for them. Sometimes she'd fall asleep in class. Then we older students would help her so things wouldn't get too wild.

There were two brothers, Leo and Haskell McInturf who were real ornery. Haskell used to peek at us when we were in the outhouse. It was kept clean with disinfectant, but there were holes where the knots had fallen out of the wood. I took can lids out one day, nailed them over the holes, and said, "There! Now you won't be doing any more peeping." They were younger than me, and I was one of the three eighth grade girls that helped teach them.

CSU Archive. Leo & Haskell far left and right. My uncle, 2nd from the right. (Link to full photo.)Leo was a paratrooper in the army during the war. He'd jump out of airplanes and did that in Germany and was there when Hitler died. I told him later, "I didn't think you'd have the guts to do that." After the war he came back and became a state highway patrolman. One day he pulled up to the house and got out. "What are you going to do, arrest me?" I asked. "Oh, Betty, don't say that. I just want to tell you I'll never forget how you taught me when I was young." We hugged before he left.

CSU Archive. Leo & Haskell far left and right. My uncle, 2nd from the right. (Link to full photo.)Leo was a paratrooper in the army during the war. He'd jump out of airplanes and did that in Germany and was there when Hitler died. I told him later, "I didn't think you'd have the guts to do that." After the war he came back and became a state highway patrolman. One day he pulled up to the house and got out. "What are you going to do, arrest me?" I asked. "Oh, Betty, don't say that. I just want to tell you I'll never forget how you taught me when I was young." We hugged before he left.Leo and Haskell's dad was a miner at the Lucky 7 mine. They didn't pay much for such dangerous work. My dad worked there, too. Once there was a cave-in, and we went up to the mine and waited to see if they'd get out. They finally did, and my dad said, "I'm never going down in that hole again," and he didn't.

Us kids would come over the mountain to the school sometimes when we couldn't get a ride. I'd wear my jeans and my clodhoppers when I'd do that. That's what we called those big-soled shoes. Anyway, the McInturf boys bought their dad a house when he was old. That was the nicest thing. They also donated land that was used to build a senior citizen center after they passed away. Haskell, you know, went on to be a wood shop teacher at Oroville High. Both you and your brother had him.

After my first teacher retired, we got Mrs. Mooney. She was a no-nonsense teacher but cared for her students. She had a new car and would sometimes give the kids rides. "No, just sit there and don't move," she'd say. She didn't want that car getting messed up. Mrs. Mooney didn't dress sexy or anything like that. They didn't pay teachers much back then. She was just a regular person and a good teacher. Later she had kids. They wouldn't let a teacher teach if she was pregnant. Things were a lot different back then.

CSU Archive. Mrs. Mooney far right. There were only three girls in the eighth grade when I graduated, no boys! A person from the department of education came and gave us tests. You had to pass to be able to go to high school. I got an "A" on the constitution part.

CSU Archive. Mrs. Mooney far right. There were only three girls in the eighth grade when I graduated, no boys! A person from the department of education came and gave us tests. You had to pass to be able to go to high school. I got an "A" on the constitution part.My cousin Mary didn't want to give the graduating speech and neither did the other girl, so Miss Mooney said, "Betty, you're going to give the speech." I knew how to make an outline, and I did the speech on conservation, on conserving nature in the area around the river and mountain and school. You two boys gave speeches, too, when you graduated. Everybody clapped and cheered when I finished. My mom said, "I didn't know you could do that."

When I went to high school, it was such a pretty building. It was so big, though. I had a hard time because I couldn't see well. I had glasses that were thick like the ends of Coke bottles and with leather on the sides. Some of the teachers would help me and some wouldn't. Mr. Nesbit, the principal, went around to all the teachers and told them that I had to have my assignments written out big so that I could see. Some wouldn't do it. They didn't do so much for kids who had difficulties back then. My cousin Mary said, "If they won't do it, then I will," and she took notes for me and wrote on the blackboard for me.

When I graduated in 1944, there should have been about two hundred students, but there were only about seventy because all the boys had gone to war. We graduated at the State Theater, and I was worried about climbing the steps to get my diploma. I wanted to do it by myself, though, and I did. When I got my diploma, Mr. Nesbit hugged me and told the audience, "Betty can't see very well, but she's a good student and a fighter." He was a nice man and cared for his students.

After I graduated, Mom didn't want me to work because of my eyes. My aunts were nurses, though, and I talked to them and they helped me. Then I went to the county hospital and applied for a job as a Practical Nurse. On my first day of work, I dressed and Mom said, "What are you doing?" I told her, "I've got a job," and that was that.

CSU Archive. Butte County Hospital when new.Later, after I married and your dad wanted me to stay home and raise you kids, Dr. Boom came over and chewed me out. He was a refined man, but he said, "What in the hell do you mean, Betty, you aren't going to take the test to become a licensed vocational nurse?" I only weighed ninety-eight pounds, but I was fast and efficient. Being a nurse was good learning for being a mother, though.

CSU Archive. Butte County Hospital when new.Later, after I married and your dad wanted me to stay home and raise you kids, Dr. Boom came over and chewed me out. He was a refined man, but he said, "What in the hell do you mean, Betty, you aren't going to take the test to become a licensed vocational nurse?" I only weighed ninety-eight pounds, but I was fast and efficient. Being a nurse was good learning for being a mother, though. I grew up being blind for a time and then not seeing well for my whole life. Now I can't see again. I can't hear so well, either. I spent my whole life not giving up, though, and that's helping me now. It's like Mr. Nesbit said--I'm a fighter. Just because you're quiet doesn't mean you're weak, and just because you're loud doesn't mean you're strong. Silent waters run deep.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on August 16, 2013 21:07

August 15, 2013

Nymph's Heart: a book review

Let's see . . . Juan Ponce de Leon, a water nymph, a Jesuit priest, the Fountain of Youth, hurricanes, the Everglades, and the Chosen One--along with three timelines: 1567, 1926, and 2005. That'll do it.

Let's see . . . Juan Ponce de Leon, a water nymph, a Jesuit priest, the Fountain of Youth, hurricanes, the Everglades, and the Chosen One--along with three timelines: 1567, 1926, and 2005. That'll do it.Archeologist William Rombola has written a creative novel that is part fantasy set in Florida, part mystery, and all adventure. The woven strands of the three timelines are artfully joined, and the main characters are fresh and fascinating in their backgrounds, personal history, and actions. Rombola also doesn't tell too much at once but lets the action gradually reveal character.

Because this is a do-it-yourself novel, there are lapses in proofreading and formatting that distract at times, but I found the concept and development of the novel sufficiently captivating to easily surge through to the end. I mean, Ponce de Leon is the bad guy.

The basic premise of the novel is that Miami is one screwed up town because an ancient corruption has not been cleansed from the land. Although this sounds like a hackneyed concept, the originality of the setting and characters make for a lively story. Also, Rombola's background as an archeologist adds verisimilitude to the places, people, and events of the novel.

Even without the guiding hand of an old-hand editor, this story is memorable, enjoyable, thoughtful.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on August 15, 2013 14:27

August 13, 2013

A Day Out with Mom #13: Plan B with Dad

We arrive at the nursing home and find Dad gone. "Yeah, he's been all over this morning," says his roommate. "Trying to get away from those 'asshole' nurses."

We arrive at the nursing home and find Dad gone. "Yeah, he's been all over this morning," says his roommate. "Trying to get away from those 'asshole' nurses.""He's getting stronger, wheeling himself around like that," Mom says, not hearing the last part. I'm not having a good feeling about the morning.

With Mom on my arm to guide and support her, we begin to cruise the halls. Turning a corner, we see Dad being wheeled back near the station by an aide.

"Hey, there you are, Dad!" I say.

"All right, let's go right now," Dad says.

He has that intense, strained, wild-eyed look that we are seeing too often. I say nothing, trying to provide no triggers for aggression or abusive behavior.

Eyes staring, Dad takes me in, my silence and all, and says, "You shut up, goddamnit!" I continue to say nothing. "All right, to hell with you," he continues, turning his wheelchair and rolling away down the hall.

"What should we do?" Mom asks.

"Let's wait here. Maybe he'll calm down if we don't follow him."

He storms down the hall, as best he can, his head and neck tensely snapping left and right as he studies his perimeter. His arm-strokes on the wheels propel him fairly quickly, considering his feebleness. He doesn't seem so feeble now, his actions flavored with a quick abruptness.

As he enters some patient's room, an aide at the station moves him out, Dad's hands gripping the armrests, his head still snapping left and right.

"Let's go to his room and meet him there," I tell Mom.

Two more aides meet us in his room as we arrive, Dad close behind, pushed by a fourth aide.

"Let's go! Goddamnit, you assholes can't keep me here," Dad yells at the aides.

"Harold, you can't talk to them like that. They're trying to help you," Mom says.

"You're my wife. Take me home."

"When you're stronger."

"Dad, Mom could hurt herself caring for you with her heart."

"There's nothing wrong with my wife. You shut the hell up!"

He lunges at me with an expression I can only describe as maniacal. I step out of reach as the aides grab and stabalize his wheelchair, keeping it motionless.

Mom steps forward. "I love you." She leans and they kiss.

"And I love you," Dad says. He reaches for her, and my heart leaps in two directions.

A nurse leans to him. "Let's lie you down to rest. Maybe you'll feel stronger after a rest."

"Don't tell me what to do!"

"We need to go," I tell Mom. "Maybe he will settle down after we're gone."

We enter and move down the hall. Mom is crying. "I don't know what to do," she says.

"We need to call before we come from now on," I tell her. "If Dad's upset, we can call again in the afternoon to see how he is."

"I don't know what to do."

"We'll call later, Mom."

"The stroke did of lot of it."

"We'll just do what we can."

That's the plan now, Plan B--call before visiting. I'll take Mom to visit Dad anytime, but Somebody Else we plan to avoid.

Addendum: Today we called and were told that Dad was sitting outside. When we showed up, he was wild again, saying I was ruining his marriage. Then he reached out to hit me. Mom and I left within minutes.

I told Mom we have to treat the situation like the weather--when it's nice, we enjoy it; when it's stormy, we get away from it and wait it out.

We're going now with Plan C: call before leaving home, and then upon arrival, have Mom sit in the lobby while I check to see Dad's mental state. Nice--we visit. If Somebody Else is on the rampage--we go away.

Today after leaving, I took Mom to the dollar store: three cans of soup, 2-in-1 shampoo/conditioner, and bath soap for $6.15. Not a solution but perhaps an anodyne.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on August 13, 2013 04:30

August 11, 2013

A Day Out with Mom #12: homage

We find Dad sitting in his wheelchair in the inner courtyard, half in shade and half in sunlight.

We find Dad sitting in his wheelchair in the inner courtyard, half in shade and half in sunlight. His eyes are closed, baseball cap shading his eyes, hands resting in his lap. Sunlight warms his back and neck. His movements are slow, almost as if flowing from a T'ai Chi posture. He has heard our voices.

As Mom sits beside him, he reaches out and takes both her hands in his. They sit in silence, Dad cupping one of Mom's hands with his, Mom patting his hands with her free hand. They have done this many, many times over the last sixty-seven years. Their hands remember one another on their own, out of muscle memory and shape carved by years.

Silence--I stand unmoving, unobtrusive. Dad opens his eyes, weak and an inflamed red. He murmurs a sentence, a question, a flow of syllables that his wife in her deafness and I with the distance cannot hear.

"What, Dad?" I ask.

He turns his vague gaze to his wife.

"Is there some way I can pay homage to this woman?"

I have never heard my father use the word "homage." I am motionless as the meaning of his words fills me.

"You are doing it now, Dad, holding hands and being together."

Mom pats his hands. Perhaps she heard the words, perhaps not.

They sit in silence, holding hands, these words homage to that moment.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on August 11, 2013 14:54

August 8, 2013

A Day Out with Mom #11: Dad dances with dementia

(Mom and I walk into Dad's room. He stares off, away from the door, at stripes of light and shadow from the venetian blinds.)

(Mom and I walk into Dad's room. He stares off, away from the door, at stripes of light and shadow from the venetian blinds.)Me/Mom: Hi, Dad, how are you doing today?" "Hello, Harold, we're here."

(No response. Dad continues to stare at the light striping the wall.)

Me: I'll just put the wheelchair over here and get the chair by you so Mom can sit by you.

(I push the wheelchair to the foot of the bed and then pick up the visitor's chair and position it next to Dad's side. As I am doing this, Mom bends down and picks up Dad's slippers to place them on the wheelchair's seat.)

Dad: Don't touch them! They're poisoned with powder they put on them!"

Mom: Harold, they're just your shoes.

Dad: No! There's poison on them. I saw them powder them. Wash your hands! Wash your hands!

Me: Dad, if the powder was that bad, they wouldn't be sticking your feet in them.

Dad: (Making abrupt, powerful pushing away movements with both hands.) All right, if you won't listen, there's nothing I can do. (Jaw set, he looks at neither of us.)

Me: OK, Dad, we'll go wash our hands. (I motion to Mom and take her into the bathroom.) Mom, remember when the German brain specialist said there were two dads--Dad and somebody else? I think Somebody Else is here today, so let's be careful and just leave early if we can't get along.

Mom: OK, let's not argue.

(We wash our hands and return. We talk to Dad but he does not respond. He continues to stare at the play of light and shadow on the wall. Occasionally he gives us sidelong glances. I pick up the daily cafeteria menu to have something to talk about.)

Me: Hey, roast beef, mashed potatoes, and gravy today, Dad. You like that.

(Dad turns his head slowly to face us.) Be very, very careful. Don't eat anything here. (He slowly turns his head so that he is staring at the stripes of light on the wall again. Mom and I talk of inconsequential, innocuous things, trying to draw Dad into the conversation. His body has a tenseness to it. He is aware of us but not responding to us. Mom and I chat and some minutes pass.)

Dad: Well, nice to have you come and visit. (He turns his head to look at us as he speaks. His voice lacks emotion and is guarded as he follows the social ritual of manners. He face is expressionless.) I'm tired and want to rest now. See you tomorrow.

Mom: OK, Harold, we'll go and let you rest.

Dad: Be careful on your way out. Don't take any chances.

(As we stand up, Dad's gaze shifts back to light and shadow. Mom kisses him. He does not respond.)

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on August 08, 2013 04:00

July 30, 2013

A Day Out with Mom #10: Dad talks bikes

123rf.comAs a kid in Oceanside, besides helping at the family business, Lee's Auto Court, I also worked odd jobs so I'd have some extra money.

123rf.comAs a kid in Oceanside, besides helping at the family business, Lee's Auto Court, I also worked odd jobs so I'd have some extra money. Mowing lawns and raking leaves were my first jobs during the summer and fall of my eighth grade year. I'd use Dad's push mower, pulling it down the sidewalks to the job, or sometimes the people would own their own mower that I'd use. I also had a job delivering special delivery letters.

When the letter was sent, in addition to the regular stamp, a special delivery stamp was also bought. The stamp had a picture of a boy on a motorcycle. I'd go to the post office and get the letter then walk to deliver it. Sometimes it was a long walk! I was paid by check twice a month. I think the stamp cost seven cents, and I was paid six for each letter I delivered.

One lady whose lawn I mowed--sometimes I'd go over there and they'd all be in the backyard with their clothes off. They had a tall hedge for privacy. I guess they were nudists. When that happened, I'd just go home.

She had an old bicycle, though, with wooden wheels that had the tires shellacked to the wood. Then you'd pump air into the tires, about forty or fifty pounds. I bought the bike for two dollars, took it home, took it all apart, and cleaned and painted it--a bright yellow so people could see me. It had big longhorn style handlebars that really stuck out. The lady's balance got too bad to ride, so I guess that's why she gave it to me so cheap. Two dollars was a lot of money back in those days, though, especially for a kid!

Now I could ride the bike to deliver special delivery. It was really heavy but much faster than walking. I used that bike to deliver letters on into high school. I'd even be in class and deliver letters. I'd check between classes, and if a letter came in I'd tell the teacher. She'd let me go, and when I got back, she'd fill me in on what I'd missed. Some of the roads were good, and some were just dirt roads. Much of the area around Oceanside in those days was just fields and scrub. Now it's all built up and full of people.

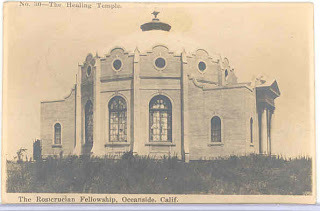

Rosicrucian Fellowship, OceansideOne place I delivered special delivery to regularly was the Rosicrucian Fellowship. Their place was about six miles out of town on a hill that could see off in all four directions--the ocean, the mountains, the desert. When the train came in, it carried mail. I tried to get there soon after the train and then head off to the Fellowship. Their buildings were adobe painted white, a main building and about ten or twelve smaller places for staying that had roofs that leaned down on one side for the rain to run off.

Rosicrucian Fellowship, OceansideOne place I delivered special delivery to regularly was the Rosicrucian Fellowship. Their place was about six miles out of town on a hill that could see off in all four directions--the ocean, the mountains, the desert. When the train came in, it carried mail. I tried to get there soon after the train and then head off to the Fellowship. Their buildings were adobe painted white, a main building and about ten or twelve smaller places for staying that had roofs that leaned down on one side for the rain to run off.I'd knock on the main door and a lady would answer. Sometimes she was asleep and I'd have to come in and wake her. She'd sign for the letters, and I'd take off--maybe back to school. I liked going there because sometimes there'd be a batch of letters I could deliver all at once, and I'd still get paid for every single letter I delivered.

Later on in high school, I'd saved up more money. I wanted to buy a motorcycle for my special delivery job, but Dad didn't want me to own one. He said they were too dangerous. Maybe that was because my older brother Leon was killed in an auto accident when he was about twelve.

Once he went fishing up in Bishop for a couple of weeks, though. He went up there a lot and left the rest of the family to run the auto court. He even met the actor Joel McCrea up there and taught him how to fly fish. McCrea had all the equipment--vest and hip boots and pole--but he didn't know how to cast or where in the stream, much less which flies to use. My dad taught him! I remember my dad said McCrea said, "I'm Joel McCrea, the actor. Seen any of my movies?" Your grandpa said, "No, I don't go to picture shows much."

So Dad was in Bishop and I found out one of my teachers had a Harley for sale because he'd just bought an Indian. I couldn't buy it because the teacher was afraid I'd get in a wreck and not have the permission of my family. Mom went down and signed for the Harley so I could have the bike. I took it home and did the same thing with it that I'd done with the bicycle--took it all apart, cleaned it, and painted it. I painted the Harley black and yellow but a brighter yellow so it could be seen better. I also bought a leather helmet to wear.

My dad came home from fishing, and the motorcycle was all together and being used for my job. I was making more money with it, so he let me keep it. My mom probably had a talk with him, too. She didn't say much, but Dad usually listened when she did--well, sometimes, anyway.

One time I came home and parked the bike. Dad came over and looked at the speedometer. It had a trip switch that would show what was the fastest you'd gone. Then you'd hit the trigger and it'd go back to zero for the next time. The needle showed 110 mph. Dad hit the trigger but didn't say anything.

I worked that special delivery job all the way through high school. It was a good job. I got to get out on my own. It was almost like working for myself because all I had to do was pick up the letters and then deliver them. For everything in between, I was my own boss. Out there on the road, there was a lot of freedom.

It's easy to forget how special it is just to be able to move, to travel, until you get old like me. I'm glad I did what I did when I had the chance. I'm glad you've got your bicycle now and are riding it all over. You should ride it back to Iowa. It's not that far, and even if it is, that's not a bad thing. It's a good thing, like getting a special delivery letter.

Copyright 2013 by Thomas L. Kepler, all rights reserved

Published on July 30, 2013 04:00