Pascale Petit's Blog, page 7

June 5, 2012

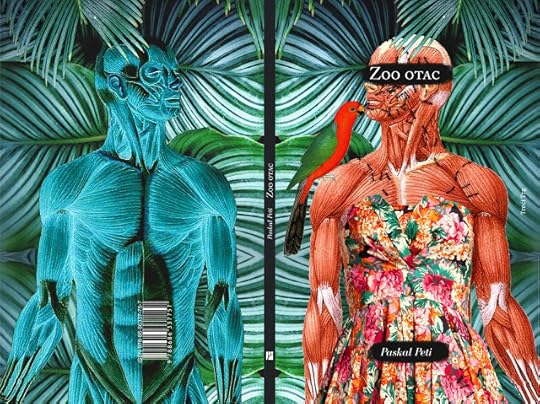

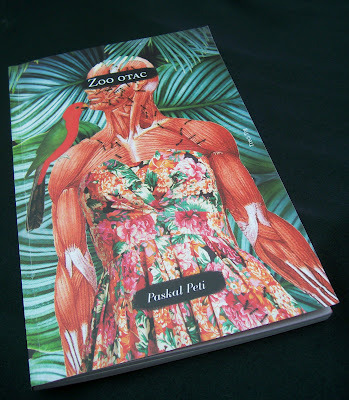

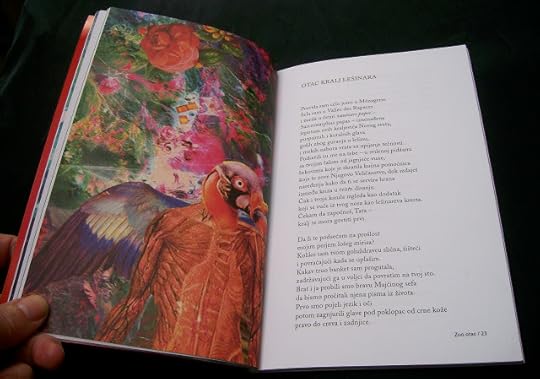

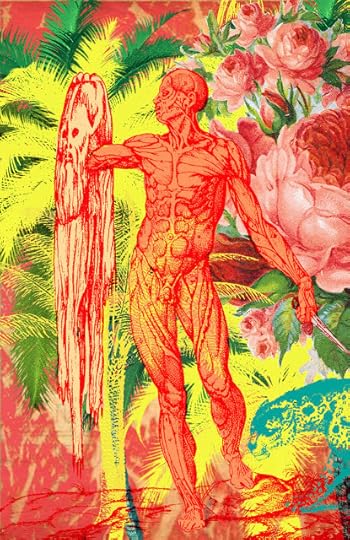

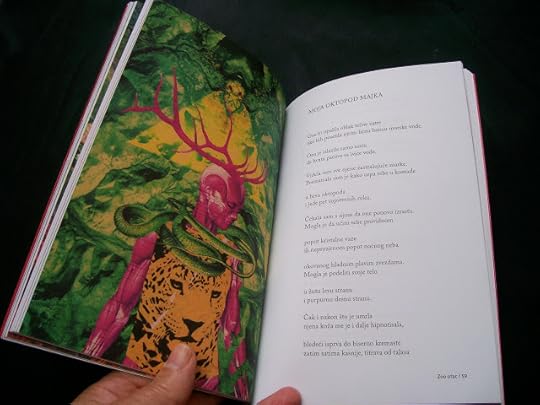

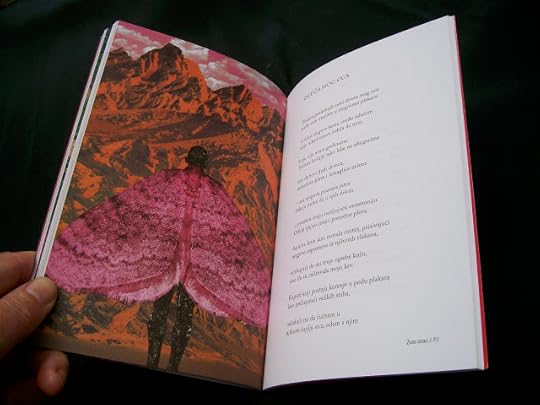

Serbian edition of The Zoo Father with illustrations: Belgrade Poetry Festival

This is the cover of the Serbian edition of The Zoo Father, published by Treci Trg and launched at the Belgrade International Festival of Poetry, May 30 – June 3, which Treci Trg also organised. I was astonished when my translator Milan Dobricic emailed me the images designed by Dragana Nikolic. She seems to have captured the spirit of my book and to have added something extra. There was an exhibition of the cover and the eleven illustrations during the four-day festival.

Apart from the chance to visit Belgrade, which I'd not seen before, this was also an opportunity for me to listen to the other guest poets, and make new discoveries, such as Vladimir Martinovski from Macedonia and Turkish poet Gokcenur C, both so fresh they made me want to write then and there, if the programme hadn't lasted until the early hours each night. Martinovski is not yet translated into English but he should be.

The Zoo Father, which was published in the UK by Seren in 2001, is currently out of stock but about to be reprinted and made available as an e-book. It has also been published in Mexico in a bilingual Spanish/English edition by the publisher El Tucan de Virginia in 2004.

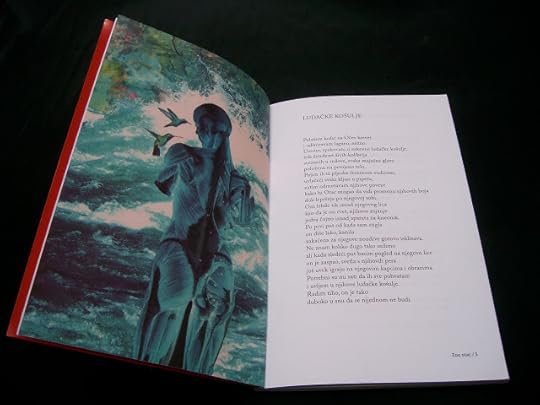

Illustration for 'The Strait-Jackets'

Illustration for 'The Strait-Jackets' 'The Strait-Jackets' to read the poem in English click here

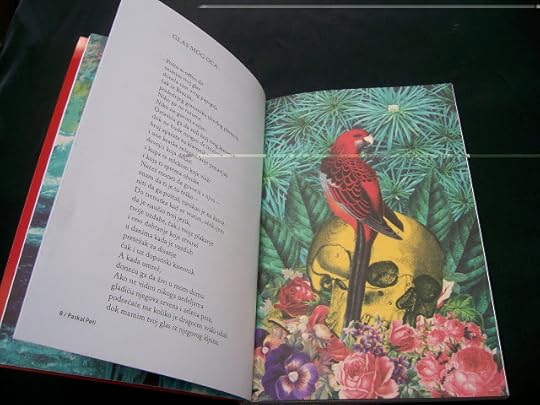

'The Strait-Jackets' to read the poem in English click here Illustration for 'My Father's Voice'

Illustration for 'My Father's Voice' Illustration for 'King Vulture Father'

Illustration for 'King Vulture Father' 'King Vulture Father'

'King Vulture Father' Illustration for 'Trophy'

Illustration for 'Trophy' 'Trophy'

'Trophy' Illustration for 'My Octopus Mother'

Illustration for 'My Octopus Mother' Illustration for 'My Father's Clothes'

Illustration for 'My Father's Clothes'

Published on June 05, 2012 05:15

May 19, 2012

Chateau Ventenac poetry course 2012

Minerve on the Gorge du Cesse (see tiny people on the dry riverbed)

Minerve on the Gorge du Cesse (see tiny people on the dry riverbed)One of my top places in the world is the Languedoc Roussillon in the south of France, so teaching a poetry course there is a dream. Last week, for six days, eleven poets joined me at Chateau Ventenac for Making Worlds, my third course at the Chateau. They came from London, Palm Springs, LA, Colorado, Stafford and Herefordshire. We spent the mornings in creative workshops, the afternoons free (though everyone had two tutorials with me so I was busy), and in the evenings there were writing games and readings. Unlike Arvon courses we were catered for – the meals were exquisite.

It was during the afternoon tutorials, while we sat under the awning by the pool on the bottom terrace, that a nightingale perched over us and sang. I knew instantly that it was the bird in Keats' ode (the poem that switched me onto poetry when I was a teenager). The notes sounded like gurgles blown in glass, breaking through to our world from another dimension – they were piercing and ecstatic. The next day he returned and sang for longer. Justina wrote that it was "like a star running down your throat". The phrase is one from a series of lines from cosmological myths that I supplied the first evening, for them to incorporate into a short poem.

I also brought along a hoard of surreal contemporary art cards to kick-start poems, and animal fact-files which I bought from Oxfam, meant for children, but those have the most fascinating facts! These included info about the hoopoe, who also sang for us regularly, pipistrelles, which swooped over the veranda each evening, the grass snake, hares and owls. Inside each file I'd inserted another sheet about myths associated with each animal. The prompt was to write a poem which included some biological facts about the creature (handed out to everyone at random), which somehow resonated, some mythological aspect, and something personal (as well as free-associations). Perhaps the poet wished to tackle a difficult subject they could dress in an animal mask. One of the examples we discussed before starting was Joy Harjo's poem 'She Had Some Horses'. They could also try her use of repetition and hypnotic chant to build momentum.

On the third writing morning we changed tack and stopped using images and texts to generate poems, and instead went for a walk along the Canal du Midi, with the golden rule that although they could chat en route to the Pont-Canal two kilometres away, they had to be silent on the return. The process was to be like the contrast between Gauguin and Van Gogh's working methods: Gauguin painting from his imagination (as we had been doing indoors so far) and Van Gogh from direct observation outdoors. The group could respond to one object along the way back through all eight senses, paying close attention to it.

Midway through the week, we had a day off and went to the medieval Cathars cité of Minerve, which leans over the intersection of two limestone gorges: the Cesse and the Brian. After a leisurely lunch in the Troubadour restaurant overlooking the gorge we wound down to the stony bed, hoping we could wade through the cave which connects the two almost-dry rivers, to a secluded valley the other side, but the water was too deep. So they explored the limestone cliffs and listened to the birds. I sat on a bank and read work for the following day's tutorials in this idyllic setting. Next year's course will also be in May, and I've already bagged my tutorial space down by the 'nightingale' bush.

Taking notes along the Canal du Midi on Wednesday morning

Taking notes along the Canal du Midi on Wednesday morning At the seventeenth century Canal-Pont, the first built in France, where the canal crosses a river

At the seventeenth century Canal-Pont, the first built in France, where the canal crosses a river The cave tunnel between the two gorges below Minerve

The cave tunnel between the two gorges below Minerve From left to right: Maria Elena Boekemeyer, Stephen Linsteadt and Lois P Jones on the gorge bed at Minerve

From left to right: Maria Elena Boekemeyer, Stephen Linsteadt and Lois P Jones on the gorge bed at Minerve The Canal du Midi

The Canal du Midi Moi in front of the bridge over the Cesse Gorge, entrance to Minerve

Moi in front of the bridge over the Cesse Gorge, entrance to Minerve Katrina Naomi with matching shutters and door at 1, La Caunette, another medieval village by Minerve

Katrina Naomi with matching shutters and door at 1, La Caunette, another medieval village by Minerve Apéritifs on the terrace each evening

Apéritifs on the terrace each evening

Writing game with the drinks!

Writing game with the drinks! On the last evening a few locals and some of our helpers came to the reading by the group. Here is Jinny Fisher reading two of her poems from the week. Everyone read work written on the course. Next to Jinny is Julia Bristow (owner of the Chateau), Philip, Susan, Mary and Justina

On the last evening a few locals and some of our helpers came to the reading by the group. Here is Jinny Fisher reading two of her poems from the week. Everyone read work written on the course. Next to Jinny is Julia Bristow (owner of the Chateau), Philip, Susan, Mary and Justina The residents of the canal. There were also otters and ducklings.

The residents of the canal. There were also otters and ducklings. Justina Hart and Carl Burness on the terrace

Justina Hart and Carl Burness on the terrace

Published on May 19, 2012 08:02

May 7, 2012

Metamorphoses Translation Workshop in Algiers April 2012

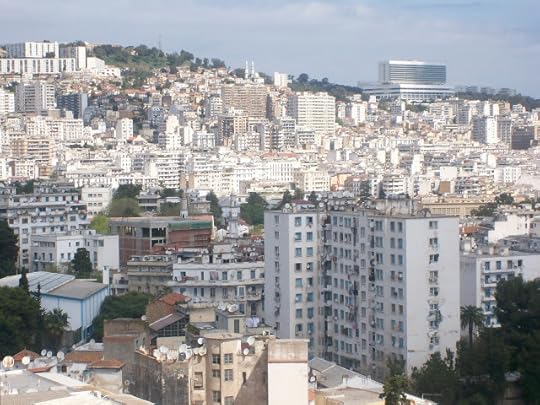

Just before I landed in Algiers I could see the Kabylie Mountains hovering above the coast. They have a special significance for me because my father lived there for a few years, during the thirty-five years of his disappearance. He told me he stayed there with his best friend, in the mountains, and he loved it. Before he disappeared, when I was still living in Paris with my parents, they ran a brasserie and beer business just by the Jardin des Plantes, and their customers were mainly Algerians. This was in the late fifties. Later I was told my father was part Algerian, but it turns out that was probably a myth. I had been to Tunisia and Morocco but I always wanted to go to Algeria. So when the British Council invited me to take part in a translation project (organised by them and EUNIC) I leapt at the opportunity. Even though getting the business visa was a lengthy, fiddly process made even harder by my French passport having Israeli stamps on it. Initially, I was invited in March for nine days, then that was postponed and shortened to a flying visit of five days in April.

At the three-day Metamorphoses workshop I worked with two groups. One translated two of my poems into Arabic and the other translated the same two poems, 'The Strait-Jackets' and 'What the Water Gave Me (VI)' into French. Each group was composed of translation or interpretation students and was led by a professional interpreter/translator. The Arabic moderator, Lotfi Zekraoui, had flown in from New York, where he is on a Fulbright scholarship at Cuny but he is from a nearby city. The French moderator was Walid Grine, son of one of the Algerian writers joining me on the project.

We only had three days to work in and I was disappointed I did not get to translate Algerian writers, especially as during the final event we all heard everyone's work (inlcuding translations into French) and I was very impressed by a short story by the novelist/poet Mostafa Fassi. The subject of the story was a wartime incident, but what impressed me was the immaculate description of a very moving scene, so moving that the moment he started to read the original in Arabic, his lead translator Malika Benbouza began silently weeping, even though she was on the stage. I heard other stories about living through wartime and under terrorism from the students as well and gained just a glimpse of what it means to be Algerian.

I was also impressed by how hard the students worked. I don't think my poems have ever been put under such intense scrutiny. One of the translation issues that came up with each of the four writers and our translators was religion and how to translate one set of references from one faith into another. I became acutely aware of the Catholic iconography in my Frida Kahlo poem, including an ascension and a reference to Saint Sebastian (Kahlo's rain of thorns). The students pondered: how does this metamorphose into the Islamic faith? There was also an issue for the Arabic students that they didn't know what hummingbirds were, since they are only a New World species.

My hotel was at the top of the hillside Algiers is built on, in the Embassy district, so, as we wound down in the car each day, round the narrow zigzags to our art centre just above the port, I tried to take photos. But this soon proved unwise, as police were everywhere and they did not like cameras, especially when the presidential convoy was about. Although there was little opportunity to take pics, we took our coffee breaks on a veranda at the art centre, and most of the photos here are taken from there. On the second evening I was going to go to the Casbah but came down with food poisoning and acute sick/dizziness. I missed the tourist spot but did get an insight into emergency healthcare, which is free and instant. The hotel, which was not a grand tourist one, provided a driver for free as well, to take me to the clinic. This was just one example of Algerian warmth and kindness. On the last evening, after our readings and public discussions, I was accompanied by Amina (from the BC) and Lotfi on a walk downtown. It was quite intimidating, as there were only men about and no tourists.

I hope the translation project continues and that British poets get a chance to get acquainted with Algerian writers and culture. If I can I hope to translate that short story by Mostafa. As the plane rose, I managed to take a photo of the Kabylie Mountains and I thought about my father living up there, probably under one of his many different names, and I warmed to him in his mountain home, remembering how fondly he had spoken of it before he died, and of the hospitality of his friends there.

The port and harbour in Algiers

The port and harbour in Algiers Algiers La Blanche

Algiers La Blanche The French team, from left to right: Amina, Walid (moderator), Asma and Soltani

The French team, from left to right: Amina, Walid (moderator), Asma and Soltani The Arabic team, from left to right: Farouk, Aicha, Lotfi (moderator), Nabil

The Arabic team, from left to right: Farouk, Aicha, Lotfi (moderator), Nabil Downtown

Downtown The post office

The post office view down to the port

view down to the port lunch break with Lotfi and Nabil

lunch break with Lotfi and Nabil after the last event with discussions and debates, two teams, with Jeremy Jacobson, Director of Algerian British Council

after the last event with discussions and debates, two teams, with Jeremy Jacobson, Director of Algerian British Council The mountains from the air

The mountains from the air

Published on May 07, 2012 11:55

May 5, 2012

Poetry from Art online anthology 2012, at Tate Modern

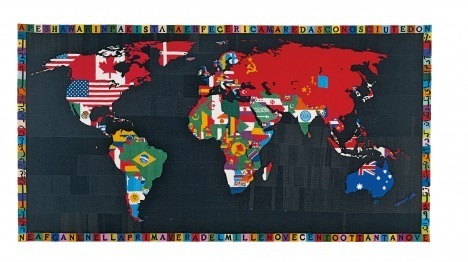

Alighiero e Boetti Mappa (Map) 1989 Embroidery on fabric 227.7 × 117.5 cm

Alighiero e Boetti Mappa (Map) 1989 Embroidery on fabric 227.7 × 117.5 cmPoetry from Art online anthology 2012

Edited by Pascale Petit The anthology of poems by the poets who attended my Poetry from Art course at Tate Modern this spring is now up on the Tate website. (My next course Shaping Poems: Image-Making, starts on 11th June). Here is the foreword to the spring anthology by Sandra Sykorova, assistant curator of adult programmes:

For over six years now, our Adult Programmes team has worked with the award-winning poet Pascale Petit on a range of poetry writing public courses inspired by works of art in our collections displays and temporary exhibitions. This online anthology is the creative outcome of the Poetry from Art: Starting Poems – Writing course that ran over six Monday evenings at Tate Modern in February and March 2012.

Twenty-one course participants, from all walks of life, had the opportunity to explore and directly respond to works of art by Alighiero Boetti, Yayoi Kusama and Catherine Yass.

In their encounters with often challenging artworks, the participants discovered new thoughts and experiences that spoke directly to them. We are delighted to share these poems with you.

The next poetry course begins on 11 June 2012 and you can find more details and book here.

Published on May 05, 2012 10:27

April 10, 2012

Goodbye to rue Hautefeuille, Paris

Here is the view from my balcony on the sixth floor, over the high plane trees in the square St André des Arts, just behind Place St Michel. The trees are swaying in the wind this morning. The leaves are almost fully out but they were just buds when I arrived ten days ago for my writing retreat. I've never had such a close relationship with the tops of plane trees before. I didn't even know they had globular female flowers. There are about nine trees in the square, sharing the space with a metro entrance, a large restaurant which sprawls under them, parked motorbikes, and various vagrants, one of whom sometimes raises a small tent from poles at night. Bye-bye trees of Paris, bye-be sparrows who cheep on my balcony demanding more crumbs. Bye-bye Easter at Notre Dame and Emmanuel, the Bourdon bell only rung on Palm Sunday, Easter day, Christmas and when peace is declared or a pope dies.

Every time I come to Paris I discover something new. This time it was Sainte Chapelle. How could I have not known about it? I was born here. Last time it was the catacombs. It's as if Paris, which is built on limestone, opens up more of its caverns on each visit. I went for a walk in the Luxembourg gardens yesterday evening, for the first time as an adult. I must have been there as a child, riding on a stag or giraffe on the old-fashioned carousel, or launching a toy yacht on the pond. I can't really remember. But what I do remember vividly is playing in the sandpit in another square, just behind where we used to live on the Boulevard de Grenelle. I went to see that sandpit again. I walked in the footsteps of a six-year-old, along the side of the park and sat and watched children playing in it. They and their parents looked happy, normal. That sandpit was the place I learnt to be an artist, a sculptor at first, then a poet. In it I created my world, a retreat from well, whatever it is I had to retreat from. I will always be grateful to it and to that simple material, sand.

Sand and leaves. So simple, they are hard to comprehend. As for Sainte Chapelle and its fifteen fifty-feet high stained-glass windows, epitome of High Gothic, how do I grasp that? Or the inside of Notre Dame, and its three rose windows, which I braved often on this visit. Or the ritual opening of the central portal, when I happened to be at the end of my first tour, just by the huge main front doors, which are always closed, when the cardinal and the congregation turned around, and the ritual was performed right under my nose, at the front of the cathedral, and after the organ had boomed out nine knocks, the bolts were drawn back and sunlight streamed into the incense-filled nave.

Published on April 10, 2012 01:33

March 13, 2012

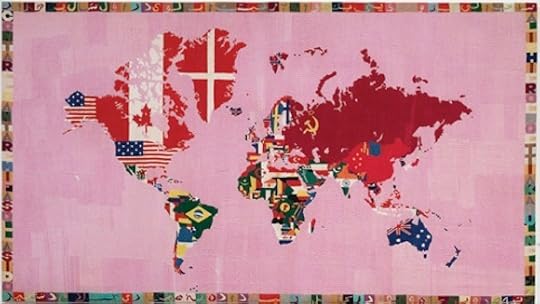

Alighiero Boetti's Maps: Poetry from Art at Tate Modern week 4

Alighiero Boetti Mappa Photo Lucy Dawkins Tate Photography

Alighiero Boetti Mappa Photo Lucy Dawkins Tate PhotographyLast night the fourth session of my Poetry from Art course was in the map room of the Alighiero Boetti: Game Plan exhibition at Tate Modern. Twenty of us sat surrounded by huge tapestries of world maps embroidered by Afghan women in their homes. The stillness and poise contrasted with the noisy rooms of our last sessions in the Kusama exhibits. When the group was hushed and writing, I could almost hear the lapping of the oceans interwoven with the murmur of the embroiderers' quiet chatter as they sewed in their homes.

Boetti considered the women embroiderers as co-authors of these works, even though he never met them, as Islamic mores forbade contact. He outlined the countries and flags on canvas with Magic Marker, then handed them over to male clan leaders who passed them on to the women and girls who would have learnt their craft from an early age. I laid out photographs of the women at work on the maps, on the bench in the centre. They were photographed by Randi Malkin Steinberger, who was allowed one day to take pictures of them for Boetti. She has since published a wonderful book of her photos.

I often ask the group to start by spending a few minutes quickly noting their immediate impressions of the art, before we discuss it or look at related poems. In this instance, hardly anyone had seen the show before the session, so I wanted them to have a chance to respond to the maps while they were still in the grip of that overwhelming awe and freshness I remembered when I first walked into the room and was surrounded by the colours of the world.

I laid out dozens of A3 photocopies of medieval map-views, complete with sea-monsters and wind-gods, on the second bench and showed them some images by two other artists who have worked extensively with maps, Guillermo Kuitca and Kathy Prendergast. We then read Elizabeth Bishop's poem 'The Map', Moniza Alvi's 'Map of India' and 'Topography' by Sharon Olds. These were examples of how the subject might be approached. Perhaps through close, precise, physical description of coastlines, as in Bishop's poem, intertwined with philosophical meditations on map-making, such as in her line: "are they assigned, or can the countries pick their colors?", or in Moniza's case, by focusing on one country which is significant for the poet, or they could try building an emotional and sensory map as Sharon Olds did, where a couple fly in from different continents to make love, still bearing the prints of those maps on their skins.

The group then had fifteen minutes to write a poem. I suggested they could assume the voice of the embroiderer, the artist, or even the map itself. We had thought that Bishop's map seemed be alive enough to lift off the page. They could try using colour as their main motif, enveloped as we were by lemon, pink, silver, black, as well as kingfisher-blue oceans. They could use place names and their sounds. They could zoom in as Moniza had done, in to one country which was significant for them and write about a personal place, bearing in mind that even the most autobiographical voice in a poem is fictionalised, and not the author's quotidian self.

I wondered how they would manage, with so much information and little time to write. There are mostly women in the group, which may account for many choosing to write in the voice of an embroiderer. Needles flashed in and out of their lines as they read back. I'm always amazed how well they write under pressure, after being reassured that they are only expected to produce 'material in progress' and not poems yet. Hearing them read their responses, as we were bathed in the glow of the tapestries, made me feel as if the world was constantly being remade. Some of the results will later be published in an online anthology on the Tate Modern website.

Published on March 13, 2012 17:50

March 7, 2012

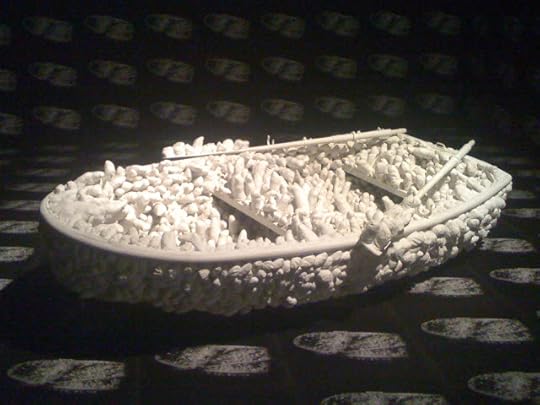

Yayoi Kusama 2: Poetry from Art at Tate Modern

For our third week and second Poetry from Art session in the Yoyoi Kusama exhibition we focused on two works: Aggregation: One Thousand Boats and The Clouds. Kusama scavenged the boat from Manhattan streets and covered it with what she called phallic shapes made of stuffed cloth and painted white. The boat glows, spotlit in a darkened room, and is surrounded by one thousand print copies. We wondered if it was beautiful or disturbing, dark or light-hearted. Someone saw it as child-like, someone else found it upsetting. We talked about how art can change traumatic experience, as Kusama has said, that the obsessive phallic shapes she covered her sculptures with are her way of working through the childhood trauma of her mother forcing her when she was four to watch her father with his many mistresses and report back to her. We agreed that the 'shapes' also look like coral encrusted on a wreck; perhaps Kusama has succeeded in rendering those shocks harmless?

We read Arthur Rimbaud's Le Bateau Ivre in the best translation I know, Drunk Boat by Ciaran Carson, and compared the French child prodigy's drunken boat with Kusama's. The original poem is stuffed with words that rock against each other in long alexandrine lines which chart 'a systematic disordering of the senses'. I encouraged people to let rip with their imaginations and language, and write a poem responding to the boat in fifteen minutes; they could use Carson's expansive long line if they wished.

But they had a choice, they could either write about the boat or The Clouds, which we also went to see, carefully avoiding leaning over the laser alarms. If they chose to write about The Clouds then their homework was to write about the boat, and vice versa. These 'clouds' are also made from stuffed and painted cloth. We looked at them and said what shapes we could see in them. To help write a poem responding to this installation, we discussed 'Falmouth Clouds' by Peter Redgrove, with its series of spawning metaphors, where he sees theatre-chocolates and cathedrals in the sky, bolts of silk unrolling, trapdoors, laboratories and tablecloths, and most unexpectedly, floating coal-mines. What unexpected images could they come up with if they wrote really fast, free-associating? And what form would they use to write a spacey sky poem? Perhaps Redgrove's airy short stanzas separated by numbered sections?

Next week we will be in the Alighiero Boetti exhibition and I think I know what room we will work in but I'm not saying.

The Clouds

The Clouds We paused to look at Accumulation Sculptures on the way to the boat

We paused to look at Accumulation Sculptures on the way to the boat

Published on March 07, 2012 20:04

February 28, 2012

High Wire by Catherine Yass: Poetry from Art at Tate Britain

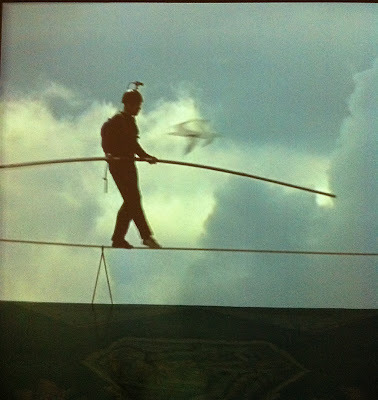

Our second session of my Poetry from Art course was at Tate Britain in the video installation High Wire by Catherine Yass. The video fills a wall but the first thing you notice is the sound of wind buffetting thirty-one-floor-high tower blocks in Glasgow's Red Road. It's such a cold sound that people could feel the blast on their backs as we sat in a circle in the gallery next to the room. The camera views are mainly ones from the camera attached to wire-walker Didier Pasquette's helmet as he inches out onto the cable strung between two of the buildings.

We saw the building opposite veer vertiginously down to the ground, shake then steady itself. And he's off, walking on air, all the time the gusts getting stronger. He walks like a ballet dancer, surely and at a fairly smart pace. A gull flies past him and he stops; his long metal pole dips too low one side. His mouth is moving and later we realise he's shouting that the winds have defeated him and the wire is moving too much. There is nothing he can do but go back and the slower backwards ballet seems impossible but must be done.

A gull flies past him just before he stops

A gull flies past him just before he stopsAfter watching the sequence we talk about the history of wire walking or rope-dancing as it was once called, how some wire walkers perform domestic feats in the air, such as cooking a meal, almost as if they are making a home in the sky. I quote Jean Genet who wrote that the role of the wire walker is to bring his wire to life: 'you will perfect your leaps...not for your own glory, but so that a dead, voiceless steel wire at last may sing'.

Yass' project was set up by Artangel and they have published an excellent book with stills and essays about it where they said: 'We had this clear image of finding these streets in the sky'. Yass has written:

When I was a child I climbed out of my bedroom window, on to the roof and up to the top. It was about six in the morning. I sat astride the rooftop, exhilarated and frightened. Coming down was harder as the tiles kept slipping, making me lose my foothold.

High Wire is a dream of walking in the air, out into nothing. But it has an urban background and the high-rise buildings provide the frame and support. The dream of reaching the sky is also a modernist dream of cities in the air, inspired by a utopian belief in progress.

Every time I see Didier turning back I remember hearing him shout, from where I was standing on another rooftop, 'C'est pas possible!' But something was possible, he returned safely. And something emerged from the actuality of the walk, which was a moment when reality became more of a dream than the dream itself.

We then read Tony Hoagland's poem 'From This Height', and discussed how he opens up time into historical time, telescoping into the past and also outwards, broadening the view, from within the constrained space of the couple on "the eighth story of the world" as they hear the wind which "rubs itself against the walls of the condominium". I wanted the group to feel that they didn't have to restrict themselves to writing literally about the installation, to be inventive and open it up into any direction that served to make the poem matter for them.

Published on February 28, 2012 09:33

February 27, 2012

Yayoi Kusama at Tate Modern: Poetry from Art

Last Monday my new Poetry from Art at Tate Modern course started in the Yayoi Kusama exhibition. Twenty six of us sat in her colourful recent paintings room (they're like a cross between outsider and Australian aboriginal art and exquisitively colourful and organic), between two installations: Infinity Mirrored Room: Filled with the Brilliance of Life and I'm Here, but Nothing. We read excerpts from Kusama's autobiography where she recounts her childhood 'hallucinations' and how these have served as obsessions for her art. We wondered if they were really hallucinations, or perhaps a glimpse into dimensions where the ego's boundaries are blurred. She says her ego was obliterated when the room she was sitting in when she was a child was taken over by polka dots and flowers, and in her parents' propagating fields where violets and pumpkins spoke to her. When her dog spoke Japanese and she barked back was she experiencing an extreme degree of negative capability?

The Infinity Room was everyone's favourite. The video doesn't do it justice. It's silent, and the endless mirrored reflections of the viewers are like dark matter between the constellations of her fluorescent dot-worlds. We went in ten at a time, parting the black curtain to step onto a path bordered by mirrored floors which turned out to be water (we could smell the chlorine). The illuminated dots pulse with waves of colour then suddenly go out and you have to stand there not daring to move, trusting they'll come back on.

We started the session by nonstop writing to the paintings which surrounded us, then everyone offered the group a gift phrase from their lines and they could incorporate one of these as well as a phrase from Kusama's poems into their response. The group then had ten minutes to write a short poem about anything in one of these three rooms that resonated for them. I brought in some short poems from Bunny by Selima Hill, as Kusama's work reminds me of the cut-glass-coloured voice of Hill's teenager who is haunted by a lodger.

The homework was to write a 'mirror' or 'specular' poem. This could respond to Kusama's Infinity Room or be about any subject. We read a superb example of the form by Julia Copus: 'The Back Seat of My Mother's Car', where the window at the back of the car works as the mirror hinge of the poem before it reverses back on itself. The second part of a 'mirror' poem is the same as the first half but the lines are in reverse order; only the punctuation can change.

Tonight we will travel to Tate Britain for our second session, to work with a brand new exhibit (in the twentieth century British art rooms) which stunned me when I went there last week for a recce, but I'm not saying what it is. Like the Infinity Room it will be a surprise.

Eyes of Mine Yayoi Kusama 2010, acrylic on canvas

Published on February 27, 2012 10:29

December 14, 2011

Chinese Water: Yangzhou and the Red Bridge Autumn Ceremony

Our last weekend in Shanghai we caught a 330 kilometres an hour train to the city of Yangzhou, north west of Shanghai and across the vast Yangtze River. The train station was big as a Heathrow terminal. Yang Lian upgraded our first class tickets to super first with just one word whispered in the conductor's ear, so we settled in the sleek, private, dragon-head of the train and got to work. George Szirtes and myself had one hour to write our translations of the Qing Dynasty 'Poem for the Red Bridge Autumn Ceremony' by Wang Hang – a devil of a quatrain in strict classical form, with a flood of info stuffed into the first two lines and what boiled down to two very short last lines in English. The original has seven characters per line and a strict tonal rhyme scheme. We did not yet have the literal translation, so most of the hurtling was taken up with Lian giving us his version of the gist.

We would have one hour for 'polishing' in the hotel before going out to banquet with our hosts, then an early rise to read our efforts at the 9am ceremony. I was much distracted by medical goings-on at home, which put the task into perspective. I'm a dedicated free verser, so my failure to meet the challenge wasn't important, as long as I tried to produce something and made the gesture.

Shortly after dawn, we settled into our gaudy gondola and set off across Slender West Lake, the subject of the poem, which is about its naming, and warmed our hands on porcelain mugs of hot green tea with cozy lids, as banks of willow, bamboo and lily grass slid past and a girl played the zither. Rainbow bridges and curly pavilion roofs with tiles like dragon scales came into view; the water was photogenic as it always is even though it's often not itself and famous here for reflecting a fairy moon. We disembarked on a dreamlike lawn where I imagined there might only be a small huddle of poets reciting to each other. People were gathering beyond the bonsai tubs, but surely nothing to do with us.

Our hosts led us towards them and we stood in a line facing the crowd. Beautiful slender girls in purple costumes gave us sprigs of lily grass and scented red silk pouches to hold. Then a round table materialised decked with familiar glasses and I knew that a toast was imminent with the white liquor baijiu, which, thankfully, must be downed in one gulp. Perhaps the baijiu arrived after the readings – it's all a blur now – though I do remember that I had to read my attempt first, relieved that none of our hosts would understand it. Here it is, with some later amendments:

Poem for the Red Bridge Autumn Ceremony

The willow leaves trail to where lily grass yellows,

the fang of flying geese and arched bridge paint echoes.

Here in this crucible where the sun's molten gold flames

we should call this framed haven Slender Western Lake.

And click here for George Szirtes' translation, in his blog. Later, he read his haunting sonnet 'Water', which begins "The hard beautiful rules of water..." and includes the magical line "That it shall arch its back in the sun". I read my poem 'What the Water Gave Me (VI)', which was translated into Chinese by both Lian and Kaiyu, so there was a distinct watery theme to our visit. As we only had a few of our poems translated during the fortnight, I heard George's 'Water' many times, that cat-like back-arching echoed by rainbow bridges. From our dragon-boat I spied waterfalls and wished we could stop to see them up close, though I suspected they were man-made.

Last time I was in China, in 2007, I flew from Shanghai to Beijing and from Beijing to Chengdu, and saw just how Shan-Shui China is with the almost continuous vistas of mountains, lakes and rivers that unfolded beneath my window. Yet the two mountains I climbed then – Huangshan (in Anhui Province) and Qingcheng (in Sichuan Province) – were both extremely wild and extremely tamed, with steps carved into every slope and sheer wall. On the summits of Huangshan there were otherworldly cloud- and mist-seas floating between the striated rock cliffs, there were also hordes of people squeezed onto the narrow paths of each jagged peak. Which reminds me of Victor Hugo's opening chapter to Notre Dame of Paris, where crowds surge along the streets, bridges and squares of medieval Paris like floodwater, as if humanity is alien as water and water is human as home.

A lunar arch for viewing the Five Pavilions Bridge

A lunar arch for viewing the Five Pavilions Bridge  Many pleasure boats ply the Slender Western Lake

Many pleasure boats ply the Slender Western Lake Our dragon driven gondola

Our dragon driven gondola

A boat and a mirror-boat

A boat and a mirror-boat

A crowd gathers behind the bonsai tubs for the Red Bridge Autumn Ceremony when Wang Hang's poem is recited and we add our translations

A crowd gathers behind the bonsai tubs for the Red Bridge Autumn Ceremony when Wang Hang's poem is recited and we add our translations Trailing willows like being behind a waterfall

Trailing willows like being behind a waterfall

Is this tree painted or real?

Is this tree painted or real?

Watery zither music on the boat

Watery zither music on the boat

These beautiful slender musicians were waiting for us in an upper room of one of the many stately homes we visited

These beautiful slender musicians were waiting for us in an upper room of one of the many stately homes we visited Portraits of poets with beautiful musicians, from left to right: George Szirtes; Zi Chuan, editor of Yangzte River Poetry Review and our host; Xiao Kaiyu; Tang Xiaodu eminent critic and poet from Beijing.

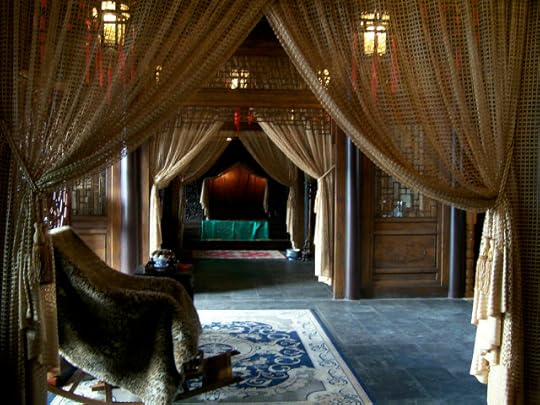

Portraits of poets with beautiful musicians, from left to right: George Szirtes; Zi Chuan, editor of Yangzte River Poetry Review and our host; Xiao Kaiyu; Tang Xiaodu eminent critic and poet from Beijing. Upstairs in the daughter's quarters of a stately home, light on the floor

Upstairs in the daughter's quarters of a stately home, light on the floor The daughter's bathtub, for light-bathing.

The daughter's bathtub, for light-bathing. The Daughter's Bedroom

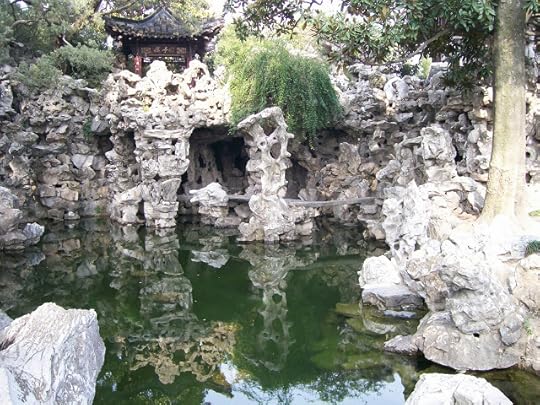

The Daughter's Bedroom These rocks are real but glued together. In another part of this garden there was a grotto retreat, complete with rock chaise longue, stone table, bookshelves and toilet!

These rocks are real but glued together. In another part of this garden there was a grotto retreat, complete with rock chaise longue, stone table, bookshelves and toilet!

We cross the road back to our minibus

We cross the road back to our minibus  The evening ends with another banquet followed by calligraphy. Here is Xiao Kaiyu drawing the ceremonial poem on rice paper, watched by George and Clarissa.

The evening ends with another banquet followed by calligraphy. Here is Xiao Kaiyu drawing the ceremonial poem on rice paper, watched by George and Clarissa.

Published on December 14, 2011 08:21