Pascale Petit's Blog, page 10

March 20, 2011

Poetry from Art at Tate Modern: Marcel Duchamp's The Large Glass

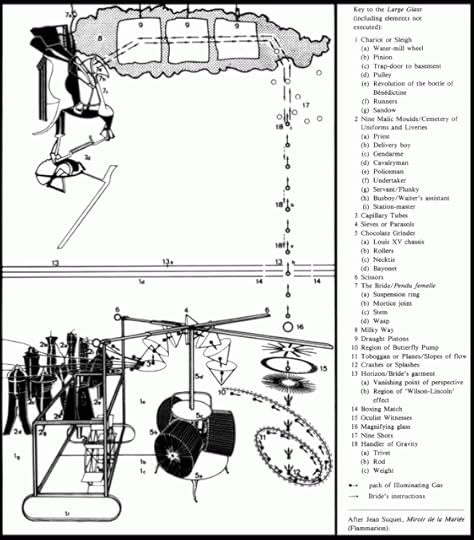

Tomorrow we'll be working with Marcel Duchamp's The Large Glass or The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, with the help of Octavio Paz's detailed description of the sculpture in his book Appearance Stripped Bare. Paz drew from Marcel Duchamp's extensive notes in a later work The Green Book. The language is a gift: "The Bride's names are Motor-Desire, Wasp, and Hanged Female, dragonfly and praying mantis..." and "The differences between the Bride's and the Bachelors' respective universes are vast. The Bride has a life-center; the Bachelors have not. They live on coal or some other raw material, drawn not from them but from their not-them..." (see below for a key to the realms of the two sexes).

I have long been drawn to this artwork, and it informed my practice when I was a sculptor. The version now on show at Tate Modern is a reconstruction by Richard Hamilton but I remember seeing it before Tate replaced the cracked bottom pane. So when I made a large glass construction influenced by it I incorporated cracks. Duchamp made this over a period of eight years then announced it definitively unfinished. The combination of his declared subject of the relation between the sexes and his "playful physics" makes its an endlessly fascinating study. Another source book for Duchamp's notes is a long heavy hardback Notes and Projects for The Large Glass by Arturo Schwarz, where Duchamp's original notes (in French) are scrawled like poems on the right and the English translation provided on the left. The notes, sketches and diagrams are an entire looking-glass world I can get lost in for hours.

Published on March 20, 2011 19:01

March 15, 2011

Ai Weiwei's Sunflower Seeds and Yang Lian's porcelain poem

@font-face { font-family: "Times New Roman";}@font-face { font-family: "MS 明朝";}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0cm 0cm 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }p.MsoPlainText, li.MsoPlainText, div.MsoPlainText { margin: 0cm 0cm 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: Courier; }table.MsoNormalTable { font-size: 10pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

For our third session of Poetry from Art at Tate Modern we worked in the Turbine Hall, with Ai Weiwei's Sunflower Seeds installation. These 100 million sunflower seeds have been individually handcrafted over two years by the artisans of the city of Jingdezhen, famed for its production of Imperial porcelain. Ai Weiwei has spoken about how the work is a commentary on the 'Made in China' phenomenon. I brought the poem 'Father's Blue & White Porcelain' by the 'misty' poet Yang Lian as a way in for the group to write about the installation. Yang Lian, who now lives in London in exile from China after the Tiananmen massacre, is as experimental an artist, and like Ai his work engages in a critical dialogue with Chinese tradition and history.

First, we watched the 15 minute film Tate made of how the porcelain sunflower seeds were manufactured, from the men mining and pounding the kaolin to the women expertly painting each seed in three or four strokes, Ai there among them, answering tweets on his mobile phone as he chatted. He is an unpretentious teddybear of a man and his warmth somehow made the installation more accessible and human-scaled. We then returned to the Turbine Hall bridge and I passed around some large striped, black sunflower seeds from Dakota, bought at my local international store, to feel as we discussed Lian's poem:

Father's Blue & White Porcelain

a small jar of night a thousand frontiers carrying himthe sky of old age continues the firing in the kilncontinues arranging this pot plant lamplighta glazed hand refines a blue coughin his flesh he embroiders the fragile whiteness of posterityturns around a thousand times the littleroom a snake's stomach swallows the longest diameter of lifehis night-long waking like the sleep-talk of the whole world

awake and not looking at humans not even waiting fora cup of darkness tea four walls softly slide upa small iron table sinks in to a venom-coated shaftanother red-hot circle sealinghis book its unread wings tightly closedhow many bloomings and fadings of seventieth birthdays have been fondledstartling a container with petals that cannot be rubbed awaylying down revealing again the birthmark of day

Yang Lian translated by Brian HoltonRiding Pisces: Poems from Five Collections (Shearsman, 2008)

A few of us thought there was the ghost of Keats' 'Ode on a Grecian Urn' when we looked at the way the father and his room are overlaid on and in the porcelain in a double exposure, the human pageant in the glaze. The images start out ordinary enough, but they soon morph: "a jar" turns unto "a jar of night', "tea" is a "a cup of darkness tea". Someone pointed out that the poem contained a deep well of history in it, both through the tradition of porcelain and in the layering of the past in the complex images: "the sky of old age" and "bloomings and fadings of seventieth birthdays".

I asked the group to sit around the Sunflower Seeds installation and write a poem about it incorporating one phrase from Lian's poem, such as "a glazed hand", "the sleep-talk". As his poem is made in a collage mosaic of images and thoughts, I wanted them to start a collage poem. I then read out quotes by Ai Weiwei when he was interviewed by Juliet Bingham and Marko Daniel (Tate curators), such as:

"In China, when we grew up, we had nothing... But for even the poorest people, the treat or the treasure we'd have would be the sunflower seeds in everybody's pockets."

"For me, the internet is about how to act as an individual and at the same time to reach massive numbers of unknown people.... I think this changes the structure of society all the time – this kind of massiveness made up of individuals."

As well as a phrase from Lian's poem, the group also had to incorporate a phrase from something Ai Weiwei had said in the interview. Homework was to carry on searching for phrases to include in a collage poem. They could find them from failed poems, notebooks, letters, anywhere. Then to print the results large, cut up the lines and rearrange them until they made a new sense. Some of the results will be published next month on the Tate Modern website in an online anthology of poems written this term.

For our third session of Poetry from Art at Tate Modern we worked in the Turbine Hall, with Ai Weiwei's Sunflower Seeds installation. These 100 million sunflower seeds have been individually handcrafted over two years by the artisans of the city of Jingdezhen, famed for its production of Imperial porcelain. Ai Weiwei has spoken about how the work is a commentary on the 'Made in China' phenomenon. I brought the poem 'Father's Blue & White Porcelain' by the 'misty' poet Yang Lian as a way in for the group to write about the installation. Yang Lian, who now lives in London in exile from China after the Tiananmen massacre, is as experimental an artist, and like Ai his work engages in a critical dialogue with Chinese tradition and history.

First, we watched the 15 minute film Tate made of how the porcelain sunflower seeds were manufactured, from the men mining and pounding the kaolin to the women expertly painting each seed in three or four strokes, Ai there among them, answering tweets on his mobile phone as he chatted. He is an unpretentious teddybear of a man and his warmth somehow made the installation more accessible and human-scaled. We then returned to the Turbine Hall bridge and I passed around some large striped, black sunflower seeds from Dakota, bought at my local international store, to feel as we discussed Lian's poem:

Father's Blue & White Porcelain

a small jar of night a thousand frontiers carrying himthe sky of old age continues the firing in the kilncontinues arranging this pot plant lamplighta glazed hand refines a blue coughin his flesh he embroiders the fragile whiteness of posterityturns around a thousand times the littleroom a snake's stomach swallows the longest diameter of lifehis night-long waking like the sleep-talk of the whole world

awake and not looking at humans not even waiting fora cup of darkness tea four walls softly slide upa small iron table sinks in to a venom-coated shaftanother red-hot circle sealinghis book its unread wings tightly closedhow many bloomings and fadings of seventieth birthdays have been fondledstartling a container with petals that cannot be rubbed awaylying down revealing again the birthmark of day

Yang Lian translated by Brian HoltonRiding Pisces: Poems from Five Collections (Shearsman, 2008)

A few of us thought there was the ghost of Keats' 'Ode on a Grecian Urn' when we looked at the way the father and his room are overlaid on and in the porcelain in a double exposure, the human pageant in the glaze. The images start out ordinary enough, but they soon morph: "a jar" turns unto "a jar of night', "tea" is a "a cup of darkness tea". Someone pointed out that the poem contained a deep well of history in it, both through the tradition of porcelain and in the layering of the past in the complex images: "the sky of old age" and "bloomings and fadings of seventieth birthdays".

I asked the group to sit around the Sunflower Seeds installation and write a poem about it incorporating one phrase from Lian's poem, such as "a glazed hand", "the sleep-talk". As his poem is made in a collage mosaic of images and thoughts, I wanted them to start a collage poem. I then read out quotes by Ai Weiwei when he was interviewed by Juliet Bingham and Marko Daniel (Tate curators), such as:

"In China, when we grew up, we had nothing... But for even the poorest people, the treat or the treasure we'd have would be the sunflower seeds in everybody's pockets."

"For me, the internet is about how to act as an individual and at the same time to reach massive numbers of unknown people.... I think this changes the structure of society all the time – this kind of massiveness made up of individuals."

As well as a phrase from Lian's poem, the group also had to incorporate a phrase from something Ai Weiwei had said in the interview. Homework was to carry on searching for phrases to include in a collage poem. They could find them from failed poems, notebooks, letters, anywhere. Then to print the results large, cut up the lines and rearrange them until they made a new sense. Some of the results will be published next month on the Tate Modern website in an online anthology of poems written this term.

Published on March 15, 2011 11:38

March 9, 2011

Celebrating Frida Kahlo on International Women's Day at Monmouth

Yesterday I gave an illustrated reading from What the Water Gave Me: Poems after Frida Kahlo for Monmouth Women's Festival to celebrate International Women's Day. The Monmouth Shire Hall was packed to capacity even though the tickets were £15 (the event included a delicious Mexican buffet lunch. I gave a 45 minute reading and talked about Kahlo's extraordinary life and paintings, showing the paintings each of my poems is based on. There were many Frida fans in the audience and some had travelled quite far to attend, not least my editor from Seren, Amy Wack, who, despite her busy schedule, comes to many of her authors' readings. Amy took this photo of me signing books.

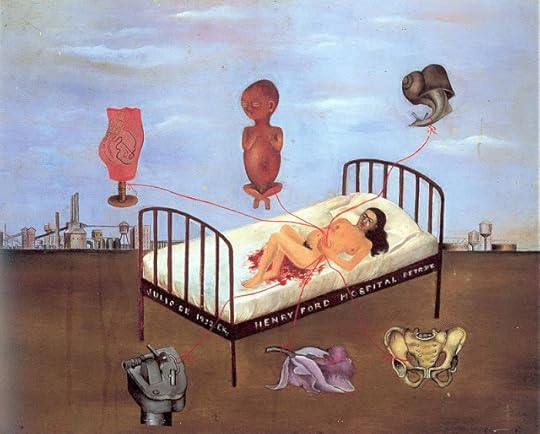

It felt right to celebrate Kahlo on International Women's Day, and include my poems about those radical paintings My Birth and Henry Ford Hospital with their depictions of childbirth and miscarriage which still have the power to shock. So when Mandi, one of the festival organisers, asked me later as she was driving me back to Newport train station, if I thought Kahlo was a feminist, I replied yes. Feminism as such wasn't yet a defined movement when she was painting (she was born in 1907 and died in1954), but what makes her so groundbreaking as an artist is how she bravely painted exactly what she wanted to paint, how she wanted to paint it, regardless of anyone else's approval. Which makes her a great role model.

Henry Ford Hospital (The Flying Bed) Frida Kahlo 1932

Henry Ford Hospital (The Flying Bed) Frida Kahlo 1932

Published on March 09, 2011 16:01

March 1, 2011

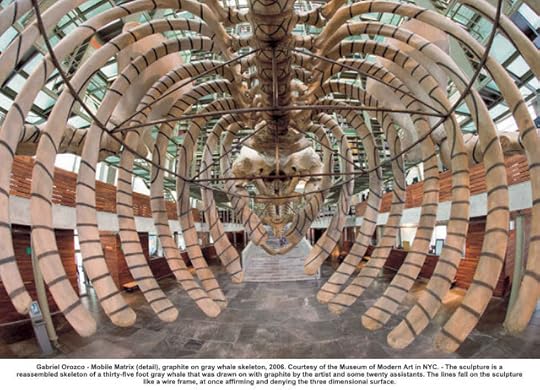

Poetry from Art at Tate Modern: Week 1 Gabriel Orozco

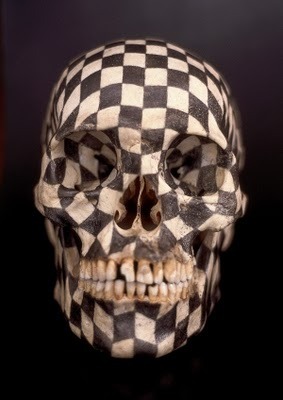

Last night my new Poetry from Art course started at Tate Modern. We are spending the first two weeks in the Gabriel Orozco exhibition and what a gift it is for poets. We sat in the hub room, between La DS and the Elevator, all twenty-seven of us. After introductions and a wander around the show we had a close look at Black Kites (see above), a real skull that Orozco painstakingly drew on with graphite while he was convalescing from a collapsed lung. I read out Carol Ann Duffy's poem 'Small Female Skull' and we compared and contrasted it with Orozco's piece. They are both weighted, compact, immaculately made, serious yet playful.

The focus of this term is image-making in poetry, how to shape poems, responding to art to help make poems more sculpted and visceral. Does the poem have one unifying image (such as a skull) or is it made up of a series of images? At the least, to be aware of the potential of imagery in a poem and how it might shape the raw material of the subject, so that the poem becomes more memorable. In Black Kites the black and white man-made checkerboard pattern surrounds and contains a found object which is a real skull; the chessboard-type grid over a mind. The dance between the two images is mind-boggling.

Duffy's 'Small Female Skull' is also mind-boggling in its ambiguity: is the poet holding her own skull or is she holding someone else's? The focus deftly shifts from inside her head to in her hands and we decided that there was no right answer, that the poem was open to individual interpretation. Early on, the skull is compared to an ocarina – the mind as musical instrument. It is delicate, papery in texture. As is Orozco's skull, with its precise loops-and-lozenge pattern over the faint hairline skull-joins.

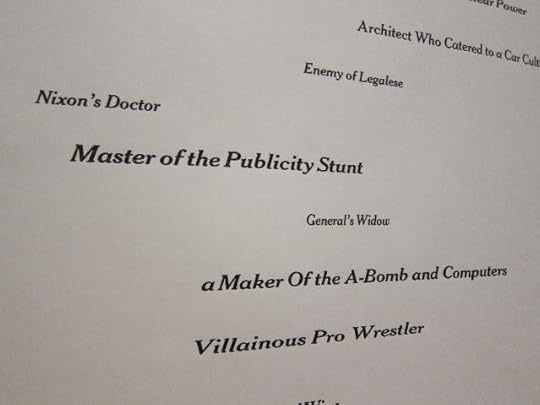

Black Kites is in the centre of the Obits Series room. Orozco collected these obituaries from The New York Times over years, selecting the ones he found "provocative or intriguing or funny or banal", removing the name and age of the person, and leaving only the heading which sums up their lives, such as "Ascertained Moon's Make-up", "Originated London Fog Coat" and "Researcher of Fireflies' Flash". Twenty-seven are reproduced on each of the large banner-like sheets of Japanese paper in various sized fonts resembling the originals as they appeared in the papers.

I asked everyone to choose one or two of the obituaries and extend them in prose notes, imagining the life suggested by the obit. They could choose one that reminded them of someone they knew, or make up an imaginary life suggested from the phrase. I then asked them to offer the group a gift phrase from their notes and we all wrote these down. The task was then to write a poem of no longer than thirteen lines incorporating one of Orozco's obits and one line from someone else. The results were imaginative, crazy and funny, and the exercise made for a good icebreaker.

One homework was to carry on working on this poem. I also set a new poem to do at home, playing at making a slight intervention in an environment and recording it, as Orozco does. In Elevator he took a lift and sawed through it, reducing it to his height, and removed the lift from its building. He also took photographs of ephemeral arrangements, such as breath on a piano. Some of his interactions are simple, such as placing oranges on every table in a factory. The task was to go on a walk in either a familiar or unfamiliar environment (it could be an office, street, wood, etc), observe it closely, make notes, take photos if possible. Then make a slight intervention Orozco style. Then write a poem about the process and not to get arrested! There was no obligation to actually do it, if they preferred they could just imagine doing it, but I suggested that it would be good if they could do something, however small.

Orozco has said that he likes to work with ordinary things and alter them slightly so as to see them anew. We discussed that and Robert Frost's idea that "Poetry is a fresh look and a fresh listen." I think that's what Orozco does with his pieces. How can we respond to his work in the same spirit in our poems?

Next week we'll have another wander around the other intriguing rooms then concentrate on Lintels. Tate has given us permission to set up our chairs under the delicate grey lint installation so it will be an interesting experience!

Published on March 01, 2011 19:47

February 19, 2011

Ai Weiwei's Sunflower Seeds at Tate Modern: poetry from art for kids

Last Monday I gave a talk to ninety 11-12 year olds at Lingfield Notre Dame School in Sussex, preparing them for their visit to Tate Modern the next day, when they were to write poems from art. While I was making a slideshow for them and researching for my workshop I fell in love with Ai Weiwei's Sunflower Seeds. I'm not sure what else to call it, but it does mean that I'm working on a poem about them, which is fun to do, even if it's no good.

I spent a day at the Tate, walking around the perimeters of the installation, looking down on them from the bridge, and watching the film of how he got a whole town in China to hand-paint a hundred million of the porcelain seeds in their husks. And wishing I'd seen the installation while you could still walk over or even bury yourself in them. En route to Sussex I hoped to find some sunflowers but it was Valentine's Day so the only flowers at the station were roses. But I did bring in a 800G bag of Dakota striped sunflower seeds, bought at my local Turkish international supermarket. The real seeds are huge, but Ai's are bigger than life and in the Turbine Hall they have an electrifying presence.

I passed the seeds around and told the kids the story of how everyone in the town of Jingdezhen (which once made porcelain for imperial China) made the 100 million seeds over a period of two years. Also, how Ai had said that "In China, when we grew up, we had nothing...But for even the poorest people, the treat or the treasure we'd have would be the sunflower seeds in everyone's pockets." I asked them to keep a few of the seeds in their pockets.

They were a lively, excitable group, and in the space of one and a half hours, they all wrote three poems each, in response to various artworks at Tate. We started by playing the game of Surreal Definitions which creates instant surrealism, and instant metaphors, such as "a mirror is a pool of silver light", "the sun is something delicious in your mouth", some of them believable, some crazy, and some very funny. One boy's ended up as "a boyfriend is where most women keep their money". His neighbour had defined "a purse" then passed his definition on, so that the definition of "where most women keep their money" got joined to the noun "a boyfriend". And so on.

Another big hit was using Moniza Alvi's poem 'I Would Like to be a Dot in a Painting by Miro' as a template for their poems when I projected Miro paintings for them to pretend to be a shape in. They had very spirited responses to this, and saw all kinds of shapes – boomerangs, arrows, hexagons, and told imaginative stories about their relationship to other shapes in the paintings.

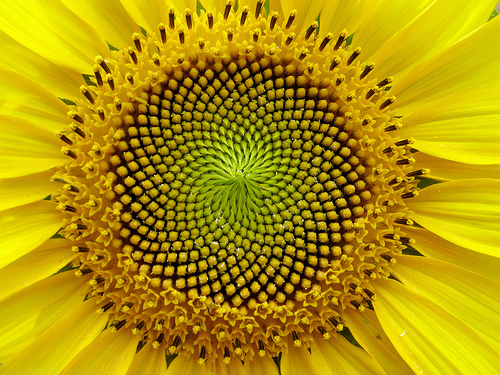

In one week my next Poetry from Art course (for adults) will start at Tate Modern, with two sessions in the wonderful Gabriel Orozco (see a previous post), then one in Ai Weiwei's Sunflower Seeds. Poems from the course will be published on the Tate Modern website in April. The art and English teachers of Lingfield school also hope to eventually publish a book of poems and drawings from the schoolkids' visit to the Tate and I'm looking forward to getting my copy. Meanwhile, here are some images of the sunflower seeds, fake and real, and a sunflower with the seeds packed in golden Fibonacci spirals.

Published on February 19, 2011 12:46

January 30, 2011

My TS Eliot Prize Reading in the Royal Festival Hall

Here is a recording of my entire reading at the 2010 TS Eliot Prize Readings in the Royal Festival Hall on 23rd January. This time last Sunday, I was nervously making my way to the Southbank and what turned out to be a two-thousand plus audience. Ian McMillan of Radio 3's The Verb introduced us all generously and warmly, welcoming us to that scary stage. I loved his joke about each poet speaking for only eight minutes, but not eight 'poetry' minutes.

The poems I read from my shortlisted collection What the Water Gave Me : Poems after Frida Kahlo were 'Remembrance of an Open Wound', 'What the Water Gave Me (V)', 'The Little Deer' and 'What the Water Gave Me (VI)'

The Poetry Book Society has recorded all ten of the shortlisted poets' readings and you can listen to them on vimeo. I'm looking forward to hearing them again, including Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, and Nobel laureate Derek Walcott, the winner of this year's prize, whose poems were read by Daljit Nagra.

There are three more of my poems from What the Water Gave Me, and by each poet from their shortlisted collections, on the Guardian website.

The poems I read from my shortlisted collection What the Water Gave Me : Poems after Frida Kahlo were 'Remembrance of an Open Wound', 'What the Water Gave Me (V)', 'The Little Deer' and 'What the Water Gave Me (VI)'

The Poetry Book Society has recorded all ten of the shortlisted poets' readings and you can listen to them on vimeo. I'm looking forward to hearing them again, including Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, and Nobel laureate Derek Walcott, the winner of this year's prize, whose poems were read by Daljit Nagra.

There are three more of my poems from What the Water Gave Me, and by each poet from their shortlisted collections, on the Guardian website.

Published on January 30, 2011 18:10

January 10, 2011

Poetry from Art at Tate Modern: Gabriel Orozco

Gabriel Orozco made 'Black Kites' when he was laid up at home with a collapsed lung. He painstakingly painted these black and white diagonals on a real skull, and has commented on how intense it was for him to live with the skull over a long period. Orozco is a Mexican artist, so I immediately think of the Aztec Tezcatlipoca smoking mirror mosaic skull inlaid with turquoise and jet in the British Museum, and the lifesize rock crystal skull carved from quartz crystal, reputed to be Aztec, though this is disputed.

Elevator

ElevatorOrozco is a playful, wide-ranging and inventive artist, with photographs, paintings, sculptures, and installations often featuring natural and found objects. A major retrospective of his work will open at Tate Modern next Wednesday, 19 January. I'm looking forward to my next Poetry from Art course which starts on 28 February and hope to spend one or two sessions in this exhibition. The course will culminate in publication of the participants' poems on the Tate Modern website. This course is booked out, but there are still a few places for the summer term, when the Miro exhibition will be on.

Dial Tone

Published on January 10, 2011 20:24

December 31, 2010

The creatures in our garden in 2010

We live in a two-up two-down terraced house in East London and have a very small overgrown garden, but over the past year it has been inhabited by a menagerie of creatures, including in July a swarm of bees which nested temporarily in our jasmine laden buddleia. Foxes shelter in our collapsed shed and toads hide from our four cats under the understorey of campanula and ivy. Photos all taken by Brian. Happy 2011 to you all from us and the beasts who share our lives.

Published on December 31, 2010 17:34

December 26, 2010

Harpy eagle nest watch

My Boxing Day was a harpy eagle research day. I am so fascinated by this creature that I can spend days trawling the web, reading about it. Like the king vulture, which I am also fascinated by, it's one of the gods of Venezuelan Amazonian tribes such as the Pemón, Warao and Yanomami. The Pemón live in the Lost World of the Guiana Highlands, near Roraima and Auyantepui. The Warao, or water people, live in stilt huts on the Orinoco Delta and the Yanomami live in south east Venezuela and north eastern Brazil. I've briefly visited the Warao and the Pemón and studied their lives and mythologies. The Pemón guide eco-tourists to the foot of Angel Falls in Canaima National Park in their curiara – traditional canoes powered by an outboard motor. They know the steep, rapid-strewn rivers of that breathtaking landscape intimately, as I discovered when we dodged rocks and rapids at full speed! They also guide groups up Mount Roraima, the highest of the tepuis or table mountains.

Their mythology includes much about the 'sky-world' – the plateaus of these giant prehistoric mesas. To ascend their spirit worlds in their myths they stick white harpy eagle down feathers in their hair. I don't know if they still do this, though I did climb Mount Roraima in 1995, and was aware that they considered it sacred and that we had to keep our voices quiet so as not to offend their spirits. The Yanomami sometimes raise a harpy eagle chick in a wooden cage for a supply of white down feathers to stick in their hair for ritual dress.

The female eagle is a third larger than the male and can even grab large howler monkeys from trees. I've posted this BBC documentary of a pair of harpies and their chick as I think it's quite extraordinary, especially towards the end, when the chick is almost fully grown (the team spent one year observing the nest), and the fledgling spends a lot of time watching the cameraman with intense curiosity. Since monkeys are pretty clever, he is going to have to learn how to outwit them so as to get enough to eat, and this film reveals the harpy's education as he observes the behaviour of his primate prey.

Published on December 26, 2010 19:29

December 16, 2010

Review of What the Water Gave Me and an essay

This is a quick post as I'm laid up in bed with flu, but very cheered up today by Ros Barber's review of What the Water Gave Me: Poems after Frida Kahlo and Val Robert's essay about my work. I find it encouraging to be favourably reviewed by a poet whose work I admire. Ros's latest collection Material, from Anvil in 2008, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. This is her author photo. You can become a fan of her work on Facebook. Here is an excerpt from her review:

This is a quick post as I'm laid up in bed with flu, but very cheered up today by Ros Barber's review of What the Water Gave Me: Poems after Frida Kahlo and Val Robert's essay about my work. I find it encouraging to be favourably reviewed by a poet whose work I admire. Ros's latest collection Material, from Anvil in 2008, was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation. This is her author photo. You can become a fan of her work on Facebook. Here is an excerpt from her review:"the book is as vibrant, and somehow life-affirming, as the paintings that inspired it. Petit's Kahlo embraces life with all the joy of one who experienced being laid 'on a billiard table' while doctors 'saw to the wounded, thinking me dead.' There is an ecstasy in the agony."

There have been a lot of reviews and blogs about What the Water Gave Me since it came out last May, including one by Ruth Padel in The Guardian, one by Zoë Brigley in New Welsh Review and another by David Morley in Magma – three other poets whose work I admire. If you go to the book page on my publisher Seren's website you can click on links to read many of their reviews. WtWGM was also Jackie Kay's Book of the Year in The Observer. The collection was reprinted after only four months and I'm very excited that a US edition will be published by Black Lawrence Press in 2011.

Val Roberts is a third year creative writing degree student at Liverpool John Moores University. In her post 'The Wonderful World of Pascale Petit' she analyses two of my hummingbird poems, 'The Strait-Jackets' from The Zoo Father and 'Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (I)' from What the Water Gave Me . I love it when people tell me things about my poems that I didn't quite register myself, but that's what she manages to do, especially in her study of the sonic echoes in both poems, and indeed, in her study of the thematic echoes, which she does very precisely, as shown in this excerpt from her analysis of 'The Strait-Jackets':

"For the first time since she arrived he starts to breathe more easily with that hummingbird metaphor, which is a soul of an injured person. Notice the subtle internal rhymes with the words 'breathe' and 'easily' and the echo of 'recycler' and 'cannula' which is attached to his nostrils as it almost slips out. This is an important part of the poem as the cannula almost slips out. This is perhaps where realisation may hit. It makes one wonder what else almost slips out. Perhaps Petit has spoken some truth about her and her father's relationship. This is the pure brilliance of Pascale's poetry. She says I don't know how long we sit there, such a powerful line and in particular with the internal half rhyme and echo of language. One does not know how long she has sat there. One does not know what has gone on."

Here is the poem 'The Strait-Jackets'. I love how she's accurately connected the hummingbird theme in this poem to the Frida Kahlo poem, where I am both writing about Kahlo's efforts to overcome her bus crash but am also coming to terms with my own childhood trauma through Kahlo's painting 'Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird'.

This is the photo of forty hummingbirds in a suitcase which inspired 'The Strait-Jackets'. The Brazilian ornithologist Augusto Ruschi's stowed his birds in a suitcase to transport them on plane flights, by lowering their temperature and placing them in a torpor (which hummingbirds go into at low temperatures to conserve energy). While they were asleep he wrapped them in pyjamas to protect their wings. Then he used to warm them up before releasing them once he reached his destination.

And here is Frida Kahlo's painting 'Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird'. It's the first painting I wrote into a poem in What the Water Gave Me. The whole book grew from this defiant self-portrait with a dead hummingbird hung from a necklace of thorns made from Christ's crown:

[image error]

Published on December 16, 2010 11:40