Terry Laughlin's Blog, page 35

May 22, 2013

Triathlon Swimming: TI Swimming Faster Presentation Part 4 “Olympic Mammals are Terrestrial Mammals Too!”

To comment on this video on YouTube, click here

0:01 – Video of Total Immersion’s Perpetual-Motion Freestyle

0:32 – Olympic Champions are Terrestrial Mammals too!

1:14 – Faster strokes is a Problem, not a Solution

Total Immersion’s Head Coach Terry Laughlin gives an in-depth triathlon swimming presentation on Swimming Faster.

At the 2009 Multisport World Expo he advocates slower, slonger strokes for more speed.

The post Triathlon Swimming: TI Swimming Faster Presentation Part 4 “Olympic Mammals are Terrestrial Mammals Too!” appeared first on Total Immersion.

May 21, 2013

Triathlon Swimming: Total Immersion Freestyle Workshops…Turn your Struggles into Skills

To comment on this video on YouTube, click here

0:01 – Total Immersion Workshops can improve your stroke efficiency by 20%

0:15 – Underwater shot of the Perpetual-Motion Freestyle

0:41 – Group instruction

Total Immersion runs the world’s best triathlon swimming workshops. Turn your Struggles into Skills at a Total Immersion Weekend Workshop where you can learn the Perpetual-Motion Freestyle

To find a total immersion workshop near you, click here ->

To find out more about Total Immersion’s Perpetual-Motion Freestyle, click here ->

The post Triathlon Swimming: Total Immersion Freestyle Workshops…Turn your Struggles into Skills appeared first on Total Immersion.

Imprinting A Quality Catch

Here is an excerpt from my recent post Imprinting A Quality Catch:

**

We need to keep in mind the purpose of the Catch – to catch a pocket of high pressure water (or a pilates ball full of water molecules), hold it, then leverage against it to enable the rotation of the body to steadily drive our body forward on the path of least resistance. It is NOT so that you can push water back longer.

EVF is not just early, it can also be extreme in what it does to the shoulder joint if not done with extreme care and perfect timing. Even then, in the style admired and imitated among the elites, it may be technique fit only for the lucky or freakishly injury-proof. Pursue with caution.

Rather than early ‘vertical’ forearm I would encourage you to think of it as an early effective catch. The purpose, after all, is not to get the arm to look a certain way but to get a good grip on the water.

Therefore, I would encourage you to use these three Focal Points, and let the early-ness of the catch happen (more safely) as a byproduct**…

**

Click here to read more on my blog Smoothstrokes.wordpress.com.

May 20, 2013

Wetsuits, Friend or Foe?

I swam into this fascinating paradox early last year when passing through San Francisco and stopped by my favorite swimming hole at Aquatic Park to go for a short cold water swim.

The water temp that day a balmy 53 degrees. I didn’t have a full wetsuit, but had my TYR swim skin sleeveless shorty (designed for temps above 78 degrees in triathlon). The veteran SF Bay swimmers of the South End and Dolphin Rowing clubs who swim frequently at Aquatics Park go without wetsuits regardless if temps are below 50 or above 60 degrees. The club swimmers generally scoff at the swimmers/triathletes with the expensive full wetsuits, but seem to tolerate them nonetheless. Rumor has it, if you join one of these swim clubs, they accept the wetsuit swimmer for a couple of weeks, then peer pressure sets in to shed your neoprene wrap and sport only your speedo, cap(s) and goggles.

I’ve swam enough in the SF Bay, a cardinal rule is to keep your head warm (neoprene cap, tyr warmwear cap, etc) and wear ear plugs to keep cold water from rushing in and out of inner ear. Also, keep core warm, drink a warm drink, and stay warm head to toes before doing a cold water swim or swimming for extended periods in colder water even at temps in the low 60’s.

Anytime I’ve swam in temps mid 50’s or below in a full wetsuit, it always stings a bit getting in, face, hands, feet hurt – and the initial seeping of cold water into the suit is a shock until the body heats it up. But after a few minutes, temps adjust and it feels very comfortable. I don’t like swimming in the full since the added buoyancy throws off balance and I need to adjust my stroke to a flatter “wetsuit stroke”. But I like warm too – so I’m OK with the buoyancy adaptation. However, after a cold water bay swim in the full wetsuit, my feet and hands would be completely numb. If I had to run to a bike transition in triathlon, I never got much feeling in feet and hands until I was well into the ride, often slightly numb until the run leg.

Swimming several open water races that split groups between wetsuit and non wetsuit, interestingly, only swimmers wearing full wetsuits have been pulled out of the water due to hypothermia. Not one swimmer (in my experience) was pulled out going “skins” or no wetsuit. What is it about the wetsuit swimmer and non wetsuit swimmer, why would the swimmer with the neoprene body wrap, their body temp drop, and the non wetsuit swimmer body temp remain at 98.7 degs? Both wetsuit and non wetsuit swimmers had similar body types, mostly lean, not much body fat to spare. One swimmer most recently at the Bridge to Bridge swim (Golden Gate to Oakland Bay bridge) wearing a high end full wetsuit became disoriented, swimming in circles, and was pulled out due to hypothermia about an hour into the swim. All skins (non wetsuit) swimmers finished and several in 56 deg water for well over two hours.

Jumping into 53 water in my sleeveless shorty speed suit, I’ll admit I was in pain. Face, shoulders, feet, hands all hurt – and cold water took my breath away. I hadn’t been in water in low 50’s for over a year and that was in a full wetsuit, no cold water acclimation. My initial thoughts were this swim wasn’t going to last very long. But as fast as the stinging cold set in, I was suddenly comfortably warm. No pain, warm, pleasant free swimming, no buoyancy adjust to a full wetsuit. I thought for a minute I was nearing death, but no – just kept on swimming comfortably for over an hour in low 50’s. Wow – this was a new experience I hadn’t expected. Is this what the swimmers at the local SF Bay rowing/swimming clubs have been trying to tell us?

Running short on time, I had to get out – but sure didn’t want to. When my feet touched down on the sand, again to my surprise, I could actually feel the sand between my toes, no numbness. My hands, no stiffness, and fingers moved freely. This was a first after a cold water swim.

Was I warmer with no wetsuit verses a wetsuit? Does the wetsuit possibly turn off or mask the body’s natural defense to remain warm? I’m neither medical doctor nor physiologist, but I can’t help but be curious. But at least with my body and body type, swimming continously in 53 degree water triggered a response to turn on a its natural defense to stay warm – through hands and feet too.

What was the common thread for those wearing full wetsuits that went hypothermic? All of these swimmers, mostly lean men, balding, military hair cut or shaved heads wearing a thin single latex race cap, and no ear plugs. All the ‘skins’ swimmers however, had neoprene caps, and/or two thick caps and ear plugs – no hypothermia. But the "skins" swimmers seem to be much more aware of their bodies and spend time adapting to cold temps, where swimmers wearing wetsuits may have a false sense of secuity and skip important prep.

Most heat escapes from your head. Regardless of what you have wrapped around your body, if your head is cold, your body will follow. Although many will argue, the surface area of the skull is far smaller than that of the body and more heat escapes from the larger surface area. This is true, but maybe it’s the larger surface (shoulders to toes) and stinging cold triggers the body’s response to turn on its natural thermal blanket.

In short, whether you wear a wetsuit or not in cold water swims:

Warm core and keep body and head warm before the swim.

Wear a thick swim cap (or caps), neoprene or warmwear cap.

Ear Plugs. Keep cold water out of inner ear.

Acclimate, slowly increase duration of each swim.

With some simple preparation, regardless of colder water temps, you may discover that you shed the wetsuit altogether – and find a new sense of freedom in cold, open water swimming, and are no longer bound to a wetsuit and its added buoyancy.

Happy Swimming!

Coach Stuart

May 17, 2013

Get Hip to Open Water Technique

This summer marks the 40th anniversary of my first experience with open water racing. I joined the Jones Beach Lifeguard Corps in 1973, and–as one of the better open water distance swimmers at Jones Beach–began to represent the Corps at lifeguard tournaments on the East Coast. I fared far better in 500- to 1000-meter races in L.I. Sounds or the Atlantic Ocean than I had in races of similar distance in college meets in the pool. I also enjoyed them far more.

I initially credited my success in open water to “natural endurance” and to having an instinct for racing without walls and lanes that others lacked.

I left the ocean behind after moving to Richmond VA in 1978. When I resumed swimming in open water in the early 1990s, I picked up where I’d left off—competing successfully in open water with people whose ‘wake I’d eaten’ in the pool.

In 2001, turning 50, I began to think of myself as an “open water specialist.” In part because the ‘sky lakes’ in Minnewaska State Park, became available for wide open swimming after years of being restricted to roped-in areas, not much bigger than a pool.

Committing to ‘Open Water Technique’

At the time, I trained in Masters workouts and swam pool meets occasionally. It occurred to me that the stroke I used in open water races—mostly between 1 and 3 miles—felt long and integrated, while the stroke I used in the pool–especially in the heat of a race (including with teammates in training)–felt more hurried and choppy.

Since I’d had my greatest success in open water races, I thought I should ‘put my eggs in that basket,’ using my open water stroke exclusively, even when racing teammates on short repeats. This meant limiting the number of strokes I would allow myself in training to 15, while keeping my average SPL between 13 and 14.

My stroke limit of 15 strokes put me at a disadvantage on 25- and 50-yard repeats, when many of my Masters teammates would take 20 or more

Thought I trailed significantly at first, before long I began closing the gap on high-revving teammates. Taking fewer strokes forced me to get more out of each stroke, but I adapted fairly quickly. And on longer repeats or sets—where I’d always finished near the top of the group–I saw even more improvement.

In 2002, I swam the 28.5-mile Manhattan Island Marathon, completing it with far longer, and more leisurely, strokes than any other competitor. From then through 2004, I had strong results in races of all distances. But it wasn’t until reading an article in 2005 by Jonty Skinner—at the time Performance Science Director for USA Swimming–that I realize how uniquely suited were the techniques I’d been practicing for open water.

Hip-Driven vs. Shoulder-Driven

Skinner’s article analyzed the contrasting techniques employed by freestylers who were more successful in Short Course (25y/m pools) vs. those who shone in Long Course (50m pools). Because the Olympics are held in Long Course, success in a 50m pool is highly valued.

After studying video from 20 years of national championships in both courses, Skinner observed that elite Long Course freestylers swam with longer, lower-tempos ‘hip-driven’ strokes. In contrast, elite Short Course freestylers swam with shorter, higher-tempo ‘shoulder-driven’ strokes.

Skinner explained the disparity this way: Among elite freestylers, in a 25-yard pool, the ratio of swimming to non-swimming (turns and pushoffs) is approximately 2.6 to 1. In a 50-meter pool, the swimming to non-swimming ratio rises to nearly 8 to 1.

I.E. During a minute of Short Course swimming, an athlete could spend as little as 43 seconds swimming and as much as 17 seconds “not-swimming.” In a 50-meter pool, he or she would spend about 53 seconds swimming and only 7 seconds “not-swimming.”

As Skinner explained, a shoulder-driven stroke allows the swimmer to achieve higher tempos and generate higher arm forces. This can create more speed in short bursts,but has great potential to cause fatigue. Frequent ‘rest breaks’ received by the arms on turns allow the swimmer to recover sufficiently to sustain a fast pace for distances up to about 200 yards.

But in a 50m pool, and when swimming over 2 minutes continuously, the hip-driven stroke proved to be the far better choice.

Upon reading Skinner’s article, I instantly recognized that what provided a significant advantage in 50-meter pools ought to be even more advantageous in open water, where the swimming-to-recovering ratio rises to infinity.

‘Lose’ the Pool Repeat to Win in Open Water

My instincts had already led me in the right direction. To complete 25 yards in 15 or fewer strokes, I had to use the hip-driven style. At 18 or more strokes, my teammates were shoulder-driven. After reading Skinner’s article, I redoubled my commitment to hip-driven technique. (I also put more focus on understanding and teaching techniques which would maximize the advantage of hip-driven technique. I’ll note those in the next installment of this series.)

And of course since most open water competitors and triathletes do the majority of their training in 25-yard pools—and especially if they race others, as in Masters workouts—the pace clock and their natural competitiveness provides a strong incentive to revert to shoulder-driven strokes. It requires a conscious decision to limit stroke count–and strong restraint when swimming next to a shoulder-driven swimmer—to hardwire the hip-driven style.

Back in 2005, I was willing to ‘lose’ the 25-yard in the present moment to be better prepared for an open water event that might be several months in the future. The following year I won the first of six National Masters open water titles and broke two national age group records. I feel certain none of this would have been possible had I not committed to the hip-driven stroke.

This article has been excerpted, in part, from the ebook Outside the Box: A Program for Success in Open Water

Hip-driven technique is illustrated on the DVDs Outside the Box and TI Self-Coached Workshop. Get all three items for 20% off in our Open Water Success bundle.

Or learn open water technique, strategies and tactics at any TI Open Water Camp.

The post Get Hip to Open Water Technique appeared first on Swim For Life.

May 14, 2013

Opportunity Cost

Here is a snippet of a comment I received on the the recent post No Bubbles To Eat:

"I have only been doing the TI method for two months and I am a competitive swimmer which messes me up…when i have to go fast."

Here was my response to that part of it (and I’ve added a bit more as I kept thinking):

And when you go faster, at some point you trip the circuit breaker in your brain (so-to-speak) and return to default mode (old) technique – putting too much load on an under-developed motor-control pathway. It takes time to replace the old with a new default that can handle higher stress – you have to start slowly with the NEW patterns and gradually build up while at the same time allowing the OLD patterns to atrophy by disuse and lose their default status in your brain. After a while, from complete refusal to use old patterns of swimming, you’re brain will only know the new patterns and regard them as the default. There will be no old technique to go back to.

Click here to read more of this on my blog Smoothstrokes.wordpress.com.

May 12, 2013

Got Talent?

Here is my two-cents to add to those who’ve been doing a great job busting the myths behind talent (Like Daniel Coyle in The Talent Code): Talent is just the gift of a head-start. It isn’t what gets you through a practice, across the finish line or onto the podium.

It may be that talent – this head-start in front of the rest of us – is just that someone finds himself a bit more aligned with how things work than others are. However, this doesn’t mean he understands how those things work, or how to cooperate further. This certainly doesn’t mean he will stay ahead if he does not gain that understanding. And this does not mean that another, one without that head-start, cannot catch up to him and pass by if he learns to align himself with how things work even better.

The talent that matters is not the instant ability to accomplish some task, but the magical skill to learn how…

**

Click here to read more on my blog smoothstrokes.wordpress.com.

May 7, 2013

How Tim Ferriss Learned to ‘Feel like Superman’

Tim Ferriss has gained worldwide renown as an expert on how to master a variety of skills very quickly, by finding shortcuts and avoiding what he calls ‘failure points’ that hamstring the average person. In his first book, The Four Hour Workweek, he explained how to escape the 9-5 grind and enjoy more personal freedom by ‘hacking’ the world of work. His blog of the same name expanded from work to ‘Lifestyle Design.’ His followup book, The Four Hour Body was filled with what he called ‘body hacks’ – shortcuts to losing fat, gaining strength and a whole range of others. He included a chapter devoted to TI.

I ordered Tim’s most recent book The Four Hour Chef the day it was released five months ago. Partly because I’m an avid cook. Preparing and eating good food closely follows swimming among my enthusiasms.

And partly because my curiosity was piqued by the subtitle The Simple Path to Cooking Like a Pro, LEARNING ANYTHING [both caps and much larger font size on the cover] and Living the Good Life. For over a dozen years, we’ve given equal emphasis to teaching the behaviors and mindsets of expertise and mastery as to teaching skillful swimming.

As soon as the book arrived, I leafed through it and, as I related in the blog META-Learning: Who Would You Rather Have As A Teacher–Phelps or Shinji? was surprised to find on p. 31 a familiar picture—a screen shot of TI Coach Shinji Takeuchi’s #1-ranked youtube video, above a screenshot of Michael Phelps’s #2 rated video.

How to Learn ANYTHING

The book’s first section is a guide to what Tim calls Meta-Learning – greatly accelerating the process for learning nearly anything by uncovering clever shortcuts and avoiding failure points that impede and dishearten most people. That Shinji who only took up swimming at 37, gained more followers on youtube than Michael Phelps, who began swimming at 7, makes him a great example of Meta-Learning.

Tim invited those who were eager to begin cooking to skip ahead to the next section where he begins to present cooking skills. I took him up on it after writing the blog about Shinji. Yesterday I returned to the Meta-Learning section to read it in full.

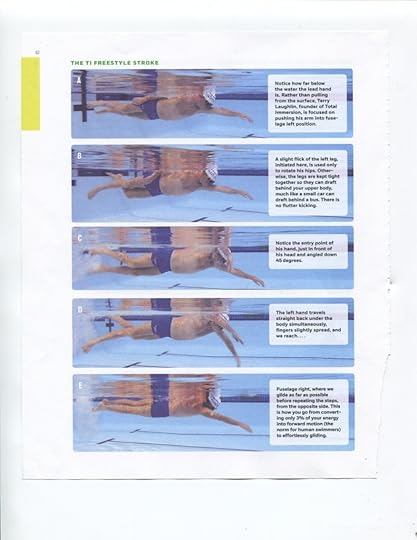

And again, to my great surprise, on p. 62 I found this series of five pictures of me, taken from screen shots in the TI DVD Self Coached Workshop: Perpetual Motion Freestyle in 10 Lessons.

Accompanying it was text, in which Tim extolled TI as an example of a Meta-Learning program – and this section explaining how learning to swim with the help of a TI DVD made him feel like Superman. Here’s the excerpt:

Despite having grown up five minutes from the beach, I could never swim more than two laps in a pool. This was a lifelong embarrassment until I turned 31, when two catalysts changed everything.

At the end of January 2008, a friend issued me a New Year’s resolution challenge: he would go the rest of 2008 without coffee or stimulants if I trained and finished an open-water 1-km swim during the year.

Months after this handshake agreement, after many failed swimming lessons and on the cusp of conceding defeat, a former non-swimmer Chris Sacca, introduced me to TI.

Total Immersion offered one thing no other swimming method had: a well-designed progression.

Each step built upon the previous and eliminated the usual failure points—like kickboards.

The first sessions including drills like pushing off in shallow water and gliding for 5 yards or so, at which point you simply stood up. Practicing breathing came much, much later. Learners of TI, by design, dodge that panic-inducing bullet when they most need to: in the beginning. The TI progression won’t allow you to fail in the early stages. There is no stress.

The skills are layered, one-by-one, until you can swim on autopilot. “

[Summarizing the next part: Tim cut drag by 50% in his first self-coached practice and had more than doubled the distance he traveled on each stroke by his fourth. Within 10 days he’d increased the distance he could swim nonstop from 40 yards to 400. Note: A 1000% increase! In 10 days!]

Several months later, at my childhood beach, I calmly walked into the ocean, well past my former fear-of-death distance and effortlessly swam over a mile—roughly 1.8 km—parallel to shore. I only stopped because I’d passed my distance landmark, a beachfront house. I felt no fatigue, panic, fear—nothing but the electricity of doing something I’d thought impossible.

I felt like Superman.

And here’s Tim telling the same story at a TED Conference

More posts about Tim Ferriss, TI and Meta-Learning

How Tim Ferriss Learned to Swim in 10 Days

Could Tim Ferriss turn The Situation on to Swimming?

How to Build World Class Muscle Memory

META-Learning: Who Would You Rather Have As A Teacher–Phelps or Shinji?

The post How Tim Ferriss Learned to ‘Feel like Superman’ appeared first on Swim For Life.

May 6, 2013

No Bubbles To Eat

An excerpt from my blog today…

**

Bubbles are evidence of turbulence. Bubbles mean there are voids in the water, which means there are low-pressure zones in that volume. Essentially, bubbles mean ‘low-traction’ zones. For a high diver this is good news. For a swimmer this is bad news.

A swimmer creating bubbles with each kick or stroke is the equivalent of a car spinning its wheels in the mud or snow. Bubbles mean there is less firm water to press against. In order to overcome the loss of traction when pulling air down with each kick and arm entry the swimmer has to exert even more effort to make up for it. Bubbles are the product of in-accurate movement patterns and lead to considerable unnecessary waste of energy.

**

Click here to read the full post on my Smoothstrokes.wordpress.com blog.

May 3, 2013

Set Up The Solution

Let me lay out the thinking behind how a TI Coach may set up the solution for a swimmer’s problem. This should be helpful to you who are self-coaching – afterall, it is our goal to help you think like a TI Coach thinks so you can improve your own swimming. At first this is going to sound a little technical as I quickly cover the concept but at the end I will give an example to show you how I applied this to a real swimmer recently.

Click here to read more on my blog Smoothstrokes.wordpress.com

Terry Laughlin's Blog

- Terry Laughlin's profile

- 17 followers