Steven W. Booth's Blog, page 4

January 23, 2013

September 27, 2012

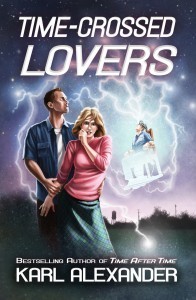

Time-Crossed Lovers by Karl Alexander

For those of you who remember the movie Time After Time with Malcolm McDowell, Mary Steemburgen, and David Warner, you’ll be pleased to know that the bestselling author of the novel and screenplay, Karl Alexander, has written a new time-travel-love-story-thriller novel which is being released this Friday. Time-Crossed Lovers is another example of Alexander’s understanding of human relationships under extraordinary circumstances.

For those of you who remember the movie Time After Time with Malcolm McDowell, Mary Steemburgen, and David Warner, you’ll be pleased to know that the bestselling author of the novel and screenplay, Karl Alexander, has written a new time-travel-love-story-thriller novel which is being released this Friday. Time-Crossed Lovers is another example of Alexander’s understanding of human relationships under extraordinary circumstances.

Time-Crossed Lovers is the story of Curtis Beckett, a convicted murderer on Nebraska’s Death Row. His crime: the brutal murder of his wife and step-daughter. His sentence: a date with the electric chair. There’s nothing particularly out of the ordinary about the chair—except in this case it just happens to be cross-wired with an experimental time-travel device housed in a Top-Secret facility built on prison grounds. No one intends for Curtis to be sent back in time—everyone expects him to die in the chair—and when he disappears when they throw the switch, no one is more surprised than Curtis to find that he has appeared in Nebraska, in October 1957. Curtis suddenly has his freedom, no past to haunt him, and an opportunity to set things right. But it isn’t the past that haunts him, it is the future. Back in the present, all hell has broken loose. Not only is Curtis missing, but so is the sister of Curtis’s murdered wife, who had come to witness the execution. The Warden is livid—no one informed him of the time-travel experiments happening under his nose. The middle of an execution was the wrong time to find out. Now he has to work with the scientists who created the time machine to get Curtis back—and execute him properly!

Time-Crossed Lovers is also a love story of cosmic proportions. As Curtis is taken to the electric chair, he has a vision of a beautiful woman whom he has never met—and never would meet, if the electric chair had done its job. But the universe will not be denied, and Curtis finds the woman of his vision living not far from the prison in a place Curtis knows well. The real question quickly becomes, will the Warden, the Governor, and the time-travel scientists succeed in bringing Curtis Beckett back to the present—simply to execute him again—or will Curtis be left in 1957 Nebraska to live out his life with the woman he loves.

When I first read Time-Crossed Lovers, I liked it right away. It had the right feel, great characters, and a fascinating premise. Karl’s understanding of that time period—the culture and attitudes of the late ’50s—makes Time-Crossed Lovers a very believable read. It reminds me of Ed Gorman’s Sam McCain mysteries, which take place a few years later and one state over in Iowa. And as a fan of the Space Program, I found it interesting that the story takes place in the past about a week after the launch of Sputnik by the Russians. It was a time of turmoil in America, and it struck me as a perfect time for the universe to open up and deposit a time traveler.

With the book launching on Friday, we were able to take advantage of the release of the book by having Karl come out to the West Hollywood Book Fair on this Sunday, September 30, 2012, and sign books. He will be appearing at the GLAWS booth, A24-27, right in the heart of the book festival. Feel free to come out and say hi, get a book signed, and enjoy the day.

Genius Book Publishing is proud to have Karl’s book as one of our publications. The book will be available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Apple iBookstore, and from booksellers everywhere starting Friday. The print version is already available for ordering at our eStore: https://www.createspace.com/3976625

September 17, 2012

In Search of “That Purple Book”

Technology is funny stuff. Take hearing aids, for example. Back in the last century, hearing aids were so horrendously expensive that the only way anyone could ever afford one is to have the cost of the device subsidized by the government and donations—usually the organization selling the hearing aid was a tax-exempt nonprofit. Technology changed all that by bringing down the price of the devices so much that hearing aids are now quite affordable. And you know what, those free and nearly free services have gone away. Does that mean that technology made hearing aids obsolete? Not at all. But it did change the nature of the hearing aid industry forever.

Today, technology has done nothing to the demand for books. If anything, it has increased that demand. Technology has made it possible to disconnect a book from the paper it was written on, and made it possible to store a nearly infinite number of titles in databases. The retrieval of those titles could mean uploading the title into an ereader or printing the book via Print-On-Demand technology. Has that storage-and-retrieval technology put authors or publishers or book designers or cover artists or editors or marketers out of business? No, they’re still there and still needed. It hasn’t even made a dent in the need for warehouses and shipping departments. But publicly available databases filled with searchable content has done one thing. It has changed the research industry, and I’m guessing that very soon, one of our most valuable national free resources will be gone the way subsidized hearing aid companies have gone. I’m talking about librarians.

I have spent much of my life around librarians. Not libraries, mind you, but librarians themselves—both my mother and my wife are librarians (I didn’t do that on purpose, I swear!). And when you get to know librarians as well as I do, you gain a deep respect for what they do—and no, telling you to shush isn’t one of the things that I’m talking about. Perhaps you didn’t know this, but librarians are actually hard-core researchers and information specialists. A librarian is someone who actually has a snowball’s chance in hell of finding “you know, that book… it’s purple, and I think it has the author’s name printed on the cover. Or was it the title?” Try typing that into Amazon.

There are organizations out there trying to replace librarians. Take Wolfram Alpha, for example (Wolfram Alpha is a natural-language search engine—or as they refer to themselves, a “computational knowledge engine”). I actually tried typing the following phrase into Wolfram Alpha: I’m looking for that book with the purple cover. Do you know the one I mean? And here is the result that I got. The Color of Purple by Alice Walker. I suppose that’s a valid answer, but it really wasn’t the book I wanted. In fact, the one I had in mind was the novella Sex, Death & Honey by Brian Knight as published by Cargo Cult Press (before he turned it into the novel Genius Book Publishing released).

Search engines have made amateur librarians of all of us, and online bookstores have diminished the need for physical libraries. But one of these days, someone is going to find a way to create a search engine just smart enough to put librarians out of business. In the short run, somewhere between when libraries go out of business and when IBM Watson is commercially available to the masses, I’m guessing some clever entrepreneur is going to create an online service where someone can submit a query as vague as “I’m looking for that book with the purple cover. Do you know the one I mean?” and get it answered by real librarians, and not by crowdsourcing like answers.yahoo.com uses (crowdsourcing is when you get a bunch of people together and hope that one of them has an answer that is close—Wikipedia.com uses the same logic).

Or maybe they won’t. You see, the kind of research librarians do is very labor intensive, and if there is one thing that technology does, it reduces the need for labor intensive activities. Labor is expensive. Technology is expensive. But the technology folks have figured out that they can keep all the money for themselves if they cut out the middleman laborers. So I’m still betting on IBM Watson to take the place of librarians well before anyone ever starts up a 24/7 librarian service.

So if you are looking for that purple book, pretty soon we—as a culture—will lose the ability to find this kind of information. Is that a big loss?

I think so, but then again, I’m biased.

September 13, 2012

The Problem With Publishing Today Is All The Damned Content

For those of you old enough (or lucky enough) to have seen the 1987 movie, The Lost Boys, you may recognize this line: “That’s the problem with Santa Carla. All the damned vampires.” That just about sums up the problem with the publishing industry. Just substitute publishing for Santa Carla and content for vampires.

Why is content a problem? Where do I start? Well, lets start by defining content, which in this case means information, generally in written form, for which there is an audience. Content can be free or paid; it can be valuable or worthless; but most importantly, it takes time to consume it, and time has a value all its own—time is money, after all. People consuming content are trading their valuable time and hopefully gaining something from the experience, entertainment and knowledge being the primary two benefits.

With the advent of self-publishing, the market was flooded with books—fiction, non-fiction, well-written, poorly written—and for the first couple of years, this was a real boon for readers and authors alike. The readers got to see some really great authors that the “gatekeeper” publishers would have otherwise ignored, and the authors got to get their work out into the market, and make money from it. That’s the point, after all.

But all that content suddenly appearing in the book market changed the dynamics of the market itself. With the increase in competition for readers’ attention, as well as their dollars, the price of content began to come down. It isn’t quite free yet, but it is approaching free as time goes on. I have been told more times than I can count that there is downward pressure on the price of ebooks in a self-publishing market. But instead of this pressure coming from Amazon, as was the common hypothesis, I’m convinced it came from market forces bigger than even Amazon itself.

Then came the spammers. It wasn’t so very long ago when Amazon had problems with bogus books, stolen books, poorly formatted public domain books, and who knows what else entering the market. Once people started noticing this problem, Amazon eventually took action to reduce if not remove spam content. Today, it is still possible to find spam-like content, but for the most part, most of the books I run across were actually written by someone, and are not stolen books or computer-generated gibberish. But the low quality of the spam—and much of the “real” stuff, too, for that matter—has created what they call in the automobile industry the “lemon effect.” A lemon car is one that just won’t work right. Some cars, even though they are identical in every way to the other cars that are the same make and model, break down or stop working much too early in the life of the car. There are even “lemon laws” that allow consumers to return lemons to the dealer when it becomes clear that they don’t work. Lemons make consumers nervous about buying cars, and lemon books—which in this case I mean bad content, not faulty software—make readers nervous about buying something practically sight unseen.

Now, it used to be that in order to avoid lemon content and find a book best suited to the reader, there were well-known, independent reviewers who gave opinions about the book, which readers used to make selections. With the flood of content at the beginning of the self-publishing revolution, it started to become more and more difficult for independent reviewers to review everything, or even nearly everything. Enter the citizen reviewer. These reviewers had been around since at least the advent of the world wide web, and were very useful for identifying bad products, services, or other consumables. Citizen reviewers had been reviewing books online from the beginning of online bookstores. But when they really came into their own was when the self-published books began hitting the market. This is because these reviews were perhaps the only reviews a book might get. Recommendation algorithms, like those at Amazon, use those reviews as a guide to what to promote. And if you weren’t being promoted by the retailer (again, Amazon), you weren’t being seen. So getting those citizen reviews became essential.

However, there is a problem with getting reviews, whether from well-known reviewers with an audience or the citizen reviews that I have referred to. It takes time to read a book (for some, a few hours, for others, a few weeks), and then it can take a couple of hours for a reviewer to craft a well-written review. That means, in the case of a very fast reader, it can take as much or more time to write the review as it did to read the book. If there was an infinite amount of time in the day, the enormous—and growing—number of books that could be reviewed would be reviewed. But since time flies, so do the opportunities to review books. Even reviewers have to sleep once in a while.

Since it is so cumbersome for a reviewer to review as many books as there are in the market, many books go unreviewed. But remember, the recommendation algorithms at Amazon and other retailers depend on those reviews. So where is an author/publisher/self-publisher supposed to get reviews, when even the well-known reviewers are backed up beyond belief. The answer is simple: Sock puppets!

I’ve already covered the subject of Sockpuppetry in detail, so I won’t repeat that here. What I will say is that sockpuppetry has created a lemon effect on the reviews that were meant to warn people away from the lemons in the first place. Talk about irony!

The enormous influx of content has overwhelmed the system. Even though there is enough demand for content out there for people to make money, the book market isn’t the Field of Dreams. If you build it, they will almost certainly not come, unless you or someone else tells them about it. Word of mouth is still the most powerful selling tool out there, but the number of books to talk about is increasing faster than the mouths can keep up. The well-known, independent reviewers can’t review everything—when contacted, most of them have told me that they receive hundreds of requests for reviews each day, and there’s no way for them to keep up. And even if you can get a citizen reviewer to review your book, nobody listens to them anymore because they are more likely to be sockpuppets than actual people—or, I suppose, if they are real people, then their reviews are canned. The system is broken.

When I say, the system is broken, I mean Amazon is broken, and Amazon broke everything else along the way. It has been clear from the beginning of the self-publishing revolution that Amazon was out to put everyone else in the publishing industry out of business. They got Borders bookstores to fold already, and they caused the agency price-fixing conspiracy to happen as a direct result of their predatory tactics. But what is becoming clear is, Amazon’s system is broken too. Sockpuppetry is a result of authors taking advantage of a gaping hole in the integrity of the review system at Amazon. I’m not defending the sock puppeters, but at the time this started, it was game the system or be left behind. Now that the sock puppet scandal has come out, Amazon is moving to fix that part of the system, but they haven’t created something to replace it with.

And, quite frankly, it is Amazon’s mess to fix.

September 11, 2012

Don’t Explain Anything!

Yesterday I was emailing with an author who had submitted a manuscript to me which I had turned down. The story was hard science fiction, and the word count was in excess of 140,000, but that wasn’t why I turned it down. The reason I did turn it down was because when I read it I was bombarded with information that, to me, was extraneous and got in the way of the story. There were other reasons that I didn’t accept it, but they were all related to the same writing “mistake.” And I’m not talking about telling vs. showing. I’ve already covered that subject. No, the real reason I decided to turn down this otherwise well-written story was because the author didn’t trust me, the reader, to understand his thoughts.

I’ve touched upon this before, but when I read a story, I want to work for it. I’m a troubleshooter by trade, a problem-solver, and I take a great deal of satisfaction in figuring things out. And I’m not the only one like that in the reading world. The entire mystery industry is built on people who want to figure out whodunnit. Not every story has to have a mystery to be interesting, of course, but what doesn’t work for me is being handed every single tidbit of background and motivation on a platter. It ruins the whole point of puzzling things out.

The author to whom I am referring has read The Hungry (I’m pretty sure I gave him a copy), and he liked it. But he made an interesting comment about it. He said, “Having read Penny Miller, I see how very lean your prose is. Part of that may be your style preference, part may be that in a zombie apocalypse motivation and backstory need not be as explicit (as in don’t get eaten and who cares).” Now, I agree that the lean prose he refers to is a style preference. Harry Shannon, my writing partner, has to continually add detail to my writing in order to anchor the reader in the scene (although in my opinion, I could get away with even less detail than Harry adds). But I don’t agree that it is the genre or the style preference that dictates the need for “lean prose.” I think any kind of storytelling can get away with reducing the amount of detail until there’s just enough to keep the reader in the story (as Harry would have it), and not ruin the mystery.

As I’ve mentioned before, one of my writing idols is George Lucas, particularly regarding Star Wars: A New Hope. In that movie, we are presented with a lot of crazy ideas—faster than light travel, laser swords, white radio/ansible-like communications, the utter lack of orbital mechanics, sound in space—and we bought into every single one of them, mainly because Lucas didn’t explain a damned thing. I was 6 years old when that movie hit the theaters, and I didn’t need a degree in engineering or astrophysics to understand what was going on. I used my imagination to fill in the blanks. Now, let’s fast forward to Star Wars: The Phantom Menace, which is an otherwise tolerable effort. I say otherwise because Lucas did something in that story—or more to the point, with that story—that he never should have done, ever. He explained things. I can sum it up in one word: Midichlorians. WTF? I mean, really. I thought the Force was created by all living things, not just these little microscopic organisms that live inside other beings. But Lucas needed an objective measure for the ability to use the Force that everyone could agree upon. Hence, midichlorians. And, in fact, the whole trilogy of “new” movies—episodes 1, 2, and 3—was one big explanation. Why did Anikin Skywalker become Darth Vader? he asks in those movies. You know what? WHO CARES?! He was Darth Vader, and that was good enough for my six-year-old mind. And 35 years later, it’s still good enough. George Lucas became one of the most important and successful people in cinematic history by not explaining. And he became irrelevant by choosing the opposite path.

Now, let’s get back to my author friend with the hard science fiction story. One of the features of hard science fiction when compared to any other kind of science fiction is that the technology at the heart of the story is as important—if not more so—than many of the characters. You have to get the technology right, even if it is complete bunk, because the technology drives the story. It must be internally consistent (as with all storytelling), and it has to be worth the suspension of disbelief that you are asking from your readers. You can’t do silly things like have breathable atmosphere in deep space (like Lucas did in the asteroid scene in Empire Strikes Back, but that wasn’t hard science fiction, it was space opera, so he can get away with it), mainly because it is demonstrably not feasible that space is filled with Nitrogen/Oxygen atmosphere. We know it isn’t so, so don’t say it in hard science fiction. But this author didn’t do that. To the best of my knowledge, his science was dead on. No, what he did was, in a way, worse. He explained the people.

I will admit up front that it has been a few weeks since I read his story, and that I did not read the entire thing. It was a submission, and I gave it just enough time to realize it wasn’t working, then stopped. But that doesn’t take away from what made his story good, or, for that matter, make what he did wrong all right.

In his story, he has an antagonist, and the antagonist has a sidekick. In order to justify that the antagonist was a true bad guy in every sense of the word, he gave us the background on the sidekick. The idea was, if the sidekick was this bad, think about how really awful the antagonist must be (he might have explained why the antagonist was bad, too, but I didn’t read that far). So the author launches into this psychological treatise on the obsession that drives the sidekick to be so bad. There were two problems with that. One, he didn’t do a very convincing job of making the sidekick someone we cared about—even to the point of caring that he lost—and two, his explanation for the obsession was kind of silly, unimportant, and frankly incomprehensible. The sidekick did his thing because he was obsessed, but the reason he is obsessed is lost on the reader.

My point is this. If you are going to make the technology an important factor, be conversant enough with the technology to understand it yourself, and dole out the information that the reader needs a little at a time, allowing the reader to piece the technology together. The same goes for the people. If you don’t have a handle on why someone is a bad guy, you as the author should figure it out. But explaining it—and explaining it wrong—are bad choices.

When an author explains something all up front, whether it be technology, or psychology, or any other -ology, and doesn’t let the reader participate in the figuring-out process, that shows a lack of trust of the reader to piece it together. I like to think I’m a smart, observant, and above all, trustworthy kind of guy. And I expect most people view themselves that way. So when the author of a story violates the trust that is inherent in the author/reader relationship, it shouldn’t be at all surprising that the readers will turn away from that author—or at least that book.

To be fair, I must say one other thing. The author to whom I am referring took my suggestion that he cut out anything that looked like excess explanation from his story, and he reports that his 140,000 word manuscript is now 108,000 words, and it is better and cleaner than ever. I’m really looking forward to reading the revised edition of the manuscript. It should be a lot more fun and challenging to read now.

September 10, 2012

How Gross Is Too Gross?

I tried to get into The Walking Dead. I really did. After being called out at World Horror Convention 2012 for being an author of zombie novels and not having seen it, I decided that it was something I had to do. I rented the first season from Netflix, talked my wife into watching it with me, and spun up the DVD player.

The characters were interesting, the premise was reasonably thought out (I still don’t buy into the “simultaneous appearance of zombies in all parts of the world” school of zombie storytelling, but this isn’t a post about zombie lore, so I digress), and the effects were cool.

But it was just too gross.

And more to the point, being gross seemed to be the point. In the third episode (or so), the heroes had to make their way through a city block of zombies to get to some vehicles to rescue themselves with. In order to get past the zombies, the heroes had to—I am not making this up—chop up a zombie and turn it into goo so they could smear the putrid stinking mess over themselves. The idea was that if they smelled like zombies, they could walk among the zombies without triggering an attack. I’ll let you watch the episode to see how it played out.

Here’s my point. As I was writing that synopsis, I could feel my gorge rise. I wasn’t exactly nauseous, but I was getting there. The whole concept of painting yourself in rotten human fluids is just… gross. And just because it is horror doesn’t mean that it has to be gross (well, not that gross).

Now, don’t get me wrong. I used to be an avid watcher of CSI (at least while William Petersen was still onboard), and I’d watch it during dinner. Now, there was a disturbing show. Their effects shop did an excellent job of depicting all manner of damage one human could inflict on another. And yes, there were some episodes that were a bit too much for me. But there was a reason for the disgusting images. They were trying to accomplish something. It was brief, and if I didn’t want to watch, I could always cover my eyes for two seconds, and it would be gone. But with The Walking Dead, if I were to take the same approach, I would be better off just blindfolding myself and listening to the audio of the show. I just couldn’t get away with looking away for a moment, because the next moment, something even more disturbing would appear.

I think about some classic horror that I’ve seen and read, and I don’t remember it being so overtly gross. In Stephen King’s Christine (both the book and the movie), there’s a scene where Christine crushes some bad-asses to death as revenge for the trashing they gave the car. Scary, sure, disturbing, perhaps, but it was just enough to get the point across and then move on. In The Shining (again, book and movie), there was the river of blood—though I kind of wish they had kept the topiary animals instead of going with the hedge maze in the movie, but again I digress—and in Misery there was the ankle smashing scene. In 30 Days of Night (I only saw the movie), the little girl vampire running through the store, dripping blood from the mouth, was pretty upsetting. But each of these scenes was brief, to the point, and actually helped move the story along.

But what is the dividing line between gross for effect and gross for gross’s sake? At the extreme end, there are authors like Edward Lee (who is a really nice guy, but who writes some really upsetting gore-porn). Violent rapes, graphic dismemberments, torture both physical and psychological. In my opinion, there’s enough bad stuff in the world that I don’t need to fill my head with those images. I can just watch the news.

Actually, I think that’s the point. I’ve said before that I write about “the end of the infrastructure” because I want to learn how to react to something that terrifies me. By confronting it head on, I can become a stronger person and more prepared to face the world. Perhaps others use downright disgusting horror as a way of facing their fears. The world is filled with bad stuff. Some of it is happening out there right now as we speak. Many people have survived situations that would crush the rest of us—many of those survivors are or were children at the time of the event. I think the people who inflict various levels of troubling, or sometimes outrageously upsetting, images on their psyches are doing it because, ultimately, horror fiction is safer than the horrors of reality.

I’m willing to bet that I’m not the first person to postulate this hypothesis. I’d be surprised if every horror writer didn’t come to this conclusion at some point during their career. But I think it needs to be said. Fiction is about “what if?” Horror fiction is about “what if something bad happens?” From my point of view, however, it is up to the individual to decide what images and ideas they will take in to their minds, and what to do with them.

Dead, rotting bodies, upright or otherwise, gross me out. But the breakdown of society fascinates and terrifies me. Should I give The Walking Dead another shot at helping me deal with my fear? If you ask my writing partner, Harry Shannon, he’d say, “absolutely!” He LOVES that show. Will I actually watch it, though? Probably not.

Instead, I think I’ll go read A Canticle For Leibowitz.

September 6, 2012

If You Like Speculative Fiction, Raise Your Tentacle

Genius Book Publishing started out with the intent to publish “speculative fiction.” But just about as quickly as we made that decision, we began hearing a startling question: “What is speculative fiction, anyway?” I mean, isn’t all fiction speculative? After all, the eternal writing prompt “What if?” can apply to anything from science-fiction to romance, and everything else, for that matter. Fiction, by it’s very nature, looks not to what is, but what could be.

But that doesn’t solve the problem. When most people (and for the purposes of this post, most people includes all the editors at Wikipedia) say speculative fiction, they are referring to genres like fantasy, horror, science fiction, supernatural, superhero, utopian, dystopian, and apocalyptic fiction, or some combination thereof.

(Just a thought: Wouldn’t it be great if someone wrote a superhero/fantasy/apocalyptic story? With a lead-in like that, I may actually be willing to do an anthology… but I digress.)

In a recent blog post, Mike Shatzkin pointed out, “40 years ago that all trade book publishing companies were started with an ‘editorial inspiration’: an idea of what they would publish. Sometimes that was a highly personal selection dictated by an individual’s taste, such as by so many of the great company and imprint names: Scribners, Knopf, Farrar and Straus and Giroux, for examples. Random House was begun on the idea of the Modern Library series; Simon & Schuster was started to do crossword puzzle books.”

Mike’s comments (or really, his father’s, since that is who he is quoting) really struck something within me. In the year since I started this publishing endeavor, I had lost sight of my original goal. Genius Book Publishing has always been a genre press (another tough term… but again, I digress), but we have tried to be as general as possible because I didn’t want to get pigeon-holed into a single genre. There’s a flaw in that approach, however.

I’ve touched upon this before, but one of a publisher’s primary duties—and one of the draws for authors who sign up with those publishers—is to build an audience, a following for each author. If the publisher can’t or won’t do that, then the author doesn’t get paid—no sales—and neither does the publisher. However, the publisher who focuses on a genre or set of closely related genres (e.g., speculative fiction) can share the audience between all of its authors. After all, it is demonstrable that most readers like more than one author. No reason they can’t read and buy most or all of a publisher’s authors—if they all write books that are similar enough to share that speculative nature.

At one point, when readers, authors, and others would ask me what kinds of books do I want to publish, I would say, “Good books.” Later on, it became clear to me that I wanted to publish exciting books that really grabbed the reader and didn’t let go. That was still a little too generic, but it was better than, “good books.” Now that I am truly realizing the power and responsibility of building an audience, it has become increasingly apparent—and increasingly important—for Genius Book Publishing to be focused in what we publish to achieve that synergy where readers come to trust us to publish books that they will want to read, and authors will know that we can build them the audience they deserve.

Does that mean we are going to be dropping any projects that don’t fit within that synergy? Well, yes and no. Yes, in the sense that we may not pick up some projects that would otherwise have been interesting to us, and No, insofar as we have no plans to cancel any projects that are currently in the works. It isn’t good enough to be ready to invest time, money, and effort into a book we believe in. We have a responsibility to both our readers and our authors to continue publishing books that both can agree upon.

So, in the future, you may not see quite as much of a variety in our selection—we probably won’t be picking up any legal thrillers anytime soon—but the books we will be choosing will hopefully appeal to those readers out there that like our other books.

Thus, if you like superhero apocalyptic fantasies, or science-fiction mysteries (okay, mysteries may be a bit of a stretch, but I love me some speculative mysteries), expect to see more of that, along with quite a bit of horror, in the coming years.

You can put your tentacles down now.