Hock G. Tjoa's Blog, page 9

October 16, 2013

Collecting kudos

I'm cheating somewhat by reproducing three reviews of Heaven is High and the Emperor Far Away, A Play as this post. But I do so in part to highlight one of the many resources a writer now has to find support while writing and, having written, to promote his or her work. The following three reviews are from Goodreads.com, a wonderful site in which to find resources while writing and then to make written work available for reviews.

I'm cheating somewhat by reproducing three reviews of Heaven is High and the Emperor Far Away, A Play as this post. But I do so in part to highlight one of the many resources a writer now has to find support while writing and, having written, to promote his or her work. The following three reviews are from Goodreads.com, a wonderful site in which to find resources while writing and then to make written work available for reviews.On July 13, 2013, Zrinka Jelic author of Love Remains (July 2013) wrote:

It took me a few pages to get into the feel of the book, but once I settled into this style I found it an enjoyable read. I'm sure there are guidelines for writing the play, but I'm not familiar with those and therefore won't review the writing itself.

The developments of the plot are giving us a clear message how reform, revolution and the change only makes things worse in the long run. If the progress is to happen, it will happen naturally at its own pace not forced by someone's beliefs and guns. The story line reminded me of an Croatian TV series that follows the little barber shop before, through, between and shortly after the two world wars. The barber's main line was "I won't tolerate politics in my shop." Yet, politics was all that was talked about. Same in the Teahouse, the owner put up signs about not discussing the politics, yet the developments in the country was the only thing on people's mind.

I would love to see this onstage. Perhaps it'd be less confusing with the lines for actors clues and cues and the kind of voice they should say the lines.

I understand that this is a translation into English, but perhaps some different words should have been chosen. For instance eunuch, the dictionary tells us it is "a man who has been castrated, esp (formerly) for some office such as a guard in a harem" Yet in this story eunuch, from what I gathered, was a man of wealth and influence who had as it was implied used a then young girl to present her as his child bride. I found this a bit confusing, but contributed it to being lost in translation.

All in all, this was a good and entertaining read.

Tani Mura on September 6, wrote:

This is a short play about a shopkeeper, his tea house, and his family and friends as he struggles through political change, economic woes, and societal immoralities in a China not so long ago.

This was a very enjoyable and light read. Translating and adapting an original work is difficult, and delivering a play in an interesting and accessible format is quite a challenge, but I think the author did a fabulous job of balancing historical context, dialogue, and stage direction to assist the reader in conjuring up an image of the play in his or her head.

The preface was extremely helpful, not only because it set up the political and social environments in which this play unfolds, but also because it allowed for some of the author’s voice to come out. Favorite quote: “Heaven is high and the Emperor is far away was a familiar saying in the provinces of China…It reflects the sense that human ideals are quite remote from out mundane reality.” The author has a knack for elegant yet not overly embellished writing, and this preface contrasted well with the simplicity of the play itself.

Of course, because this is meant to be a play, and we as readers aren’t able to see the actors’ facial expression, catch their subtle motions, or hear the anguish or laughter in their voice, much of it is left to the readers’ imagination. For those who are seeking descriptive character development and a detailed plot, you may not enjoy this as much. But for me – an avid reader who appreciates when books leave a lot of room for the readers’ own imagination – this was a very enjoyable read.

Then most recently on October 8, Peter Stone opined:

'Heaven Is High and the Emperor Far Away, a Play' by Hock G. Tjoa, was a most enjoyable and informative read of a most tragic period of Chinese history, of a time when China was recovering from the ravages committed by the Japanese army during World War Two, only to plunge into the civil war as the Communists rose to power. The play gives us a glimpse of everyday life in this time, by letting us experience it through the goings on within a teahouse that had survived decades of power struggles and wars.

I felt very sorry for the shopkeeper as he poured his life and years into the teahouse, only for the vultures of a corrupt government take advantage of him time after time. I lost count of how many times he had to fork out bribes, to cops, agents, and others, just to keep in business or to keep them away from his customers.

And all the while the shopkeeper is preparing to re-open the teahouse. As I read I began to wonder if he would even be able to re-open the teahouse before running out of money. There is a broad spectrum of characters, from many walks of life, and watching them interact with each other is a treat.

Disclaimer - I was provided a copy of the play by the author for an unbiased review.

======

I trust readers will follow the link in the first paragraph to see other reviews and also to explore the world of Goodreads for themselves. Amazon has recently purchased that site but what that means is unclear to me. Sharp-eyed readers will also notice that I have changed the background color of the cover from a rosy pink to a golden yellow; this is now easily done on a site such as Createspace through which I published both the paperback and Kindle version of this play. Chalk it up to modern technology!

Published on October 16, 2013 17:18

October 2, 2013

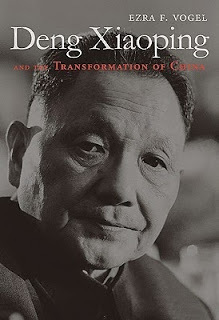

Deng Xiaoping and Liberal Democracy

Reading this large but absorbing tome leaves one with the sense that Vogel wished Deng had brought China closer to liberal democracy, in the same fashion as old school biographers of Gandhi conveyed the chimes of a pious wish that he had become a Christian. Neither eventuality was ever "in the cards." One suspects that many reviewers of Vogel's work are critical also of the author for "going easy" on Deng for the very same reason.

Reading this large but absorbing tome leaves one with the sense that Vogel wished Deng had brought China closer to liberal democracy, in the same fashion as old school biographers of Gandhi conveyed the chimes of a pious wish that he had become a Christian. Neither eventuality was ever "in the cards." One suspects that many reviewers of Vogel's work are critical also of the author for "going easy" on Deng for the very same reason.Though it looms large in current international relations, liberal democracy has very shallow roots. One cannot accuse the British Empire, for instance, of having tried to make the world safe for democracy; it was trying to make it safe for the British pound. Not until well into the twentieth century can liberal democracy be said even to exist. The international megaphone meanwhile has been passed on. As western democracies were/are refining their notions of liberal democracy, dozens of other countries were/are struggling simply to be free, from their past and from their recent colonial overlords. It seems suspicious that these former overlords should require of India, China and the dozens of nations that came into being around the middle of the twentieth century that their politics be conducted as if by Westernized Oriental Gentlemen.

John Locke can be said to have laid the foundation for such a philosophy of political behavior

or government, but it is useful to remember that he did much of his thinking in the comfort of the palatial residence of the Earl of Shaftesbury whom he served as personal physician. The notion elaborated in the Second Treatise on Government that civil society should have the liberty and legitimacy to overthrow a (royal) government that had grown tyrannical formed the rationale for the Glorious Revolution of 1688. England deposed one king and adopted another with some sort of understanding that the new monarch would get along better with the nobility and landed gentry. Locke would have been horrified to see his ideas pressed into the service of the American revolution as it was (as brilliantly argued by Louis Hartz in 1955) and would probably be spinning in his grave about the Irish being given any kind of democracy. What he would have thought about Margaret Thatcher's successful attempt at re-establishing British liberal democracy in the Falklands (what did she or the world think was going to happen to the Islands under Argentine rule?) and failed attempt to maintain it in Hong Kong, it is best not to speculate.

or government, but it is useful to remember that he did much of his thinking in the comfort of the palatial residence of the Earl of Shaftesbury whom he served as personal physician. The notion elaborated in the Second Treatise on Government that civil society should have the liberty and legitimacy to overthrow a (royal) government that had grown tyrannical formed the rationale for the Glorious Revolution of 1688. England deposed one king and adopted another with some sort of understanding that the new monarch would get along better with the nobility and landed gentry. Locke would have been horrified to see his ideas pressed into the service of the American revolution as it was (as brilliantly argued by Louis Hartz in 1955) and would probably be spinning in his grave about the Irish being given any kind of democracy. What he would have thought about Margaret Thatcher's successful attempt at re-establishing British liberal democracy in the Falklands (what did she or the world think was going to happen to the Islands under Argentine rule?) and failed attempt to maintain it in Hong Kong, it is best not to speculate.But India, China and other nations though new as nations are not so new as cultures or civilizations. They developed not besotted with the belief that "all that is, is right," nor that Progress was "historically inevitable," nor that as such it would lead to liberal democracy. In China, the essence of political legitimacy was to maintain order and prosperity such that even though enough is known about neighboring countries, its own people would have no interest to visit their neighbors. When Deng was confronted with the dramatic escapes from China to Hong Kong, his reaction was not to preach liberal democracy (which might have recommended walls of razor wire) but economic development.

Is this cultural difference tantamount to a "clash of civilizations"? I seriously doubt it. Huntington's essay was occasioned by the work of a former student who wrote The End of History, an explication of Hegel's notion (one Marx approved of) that nation-states would inevitably wither away. If so, what would we ever fight over? From the point of view of an American political scientist in the 1990s, cultural values, of course. Alas, nation-states do not appear to be in any hurry to wither away. Further, conflict arises not discernibly because of cultural differences; it seems more likely to be the case when there is a bully in the schoolyard.

Ten years before Ayatollah Khomeni referred to the United States as "the Great Satan," pundits were agog with Servan-Schreiber's Le Defi Americain. Perhaps that was simply Gallic nerve. Then came Shintaro Ishihara's The Japan that can say No. He was deemed a ultra-nationalist crank. What do pundits think a poll of European and South American states today would reveal?

Ten years before Ayatollah Khomeni referred to the United States as "the Great Satan," pundits were agog with Servan-Schreiber's Le Defi Americain. Perhaps that was simply Gallic nerve. Then came Shintaro Ishihara's The Japan that can say No. He was deemed a ultra-nationalist crank. What do pundits think a poll of European and South American states today would reveal?We can all hope that the nation-states of the world spare some consideration for economic prosperity whether or not they are also thinking of liberal democracy or worried about the schoolyard bully.

Published on October 02, 2013 18:23

July 19, 2013

Literary "crunches"

Many years ago, perhaps a few decades now, I found that reading some pages of Fowler’s Modern English Usage would provide a boost to literary activity much as doing twenty-five jumping jacks and/or stomach crunches might get my heart rate up. Alas, Fowler’s became increasingly out of date and the many worthy new editions did not have the same combination of snap and gravitas to do the trick.

I am happy to report that I have found a substitute; it is Francine Prose’s Reading Like a Writer: a guide for people who love books and for those who want to write them. Prose is herself a writer of fiction and though I must confess I do not agree with all her suggestions for books “to be read immediately,” I am pleased to find that I heartily concur with her recommendation of many. These books and others provide illustrations for the wise advice that she has for writers. There is much humor also in this book.

On sentences, for instance, she tells the story of a young author who has lunch with a “super-agent.” They discuss the writer’s ambitions and, when the writer confesses that he is not interested in genres so much as he is in writing beautiful sentences, the agent pauses for a longish time. “Never,” he finally says, “tell this to any publisher.”

Prose also advises that writers occasionally read their work out loud, a practice common among the gentry before mass entertainment trashed the amateur efforts of guests at country homes to entertain themselves, to become aware of the cadence, the rhythm of one’s sentences.

The catholicity of her taste and sources is indicated by her choice of examples. For paragraphs, she selects, among others, Isaac Babel and Rex Stout. "A new paragraph is a wonderful thing," said Babel. "It lets you quietly change the rhythm, and it can be like a flash of lightning that shows the same landscape from a different aspect." Prose adds that paragraphs are very much like breaths; they are the natural places/times to inhale or exhale.

From Rex Stout, via Nero Wolfe, comes this observation: "Paragraphing--the decision whether to take short hops or long ones, and whether to hop in the middle of a thought or action or to finish it first--that comes from instinct, from the depths of personality." Thus paragraphing is as peculiar to an individual writer as his or her fingerprint. Some authors are loath to make paragraph breaks, most famously Gabriel Garcia Marquez, whose Autumn of the Patriarch is written in a single paragraph.

Finally, for this was never intended to be a condensation of all that Prose has to teach a writer, the source that brought Babel's thoughts on paragraphs to us also found him with a high stack of handwritten pages on his desk; was the master of the short story finally going to write a novel? Not at all. The stack represented revisions of his latest short story, all twenty-two of them.

Published on July 19, 2013 15:03

June 22, 2013

Cozy Mysteries

Given the flood of dark, often sadistic, noir mysteries, I have turned for relief to the "cozies." One thinks at once of Agatha Christie whose Mysterious Affair at Styles published in 1920 introduced to the world Hercule Poirot. Lovers of the cozies who are purists tend to stick with the novels that feature Miss Marple. But it is Poirot, Chief Inspector Japp and the useful Captain Hastings (who narrates this story) that are the first of Christie's creations. It is an inspired combination of the slightly ridiculous Belgian detective so full of himself and his waxed mustache with the ever helpful Hastings to drive Monsieur around together with the very epitome of Englishness in Inspector Japp of Scotland Yard. No doubt some version of his character is associated with continental visions of "le roast beef."

Americans can be proud of the Cat Who series created by Lillian Jackson Braun. The first of these, The Cat Who Could Read Backwards, was published in 1966. Because all the stories were set in the same (mid-western) small town with more or less the same characters (no exotic settings or characters for Braun), readers can look forward to a new Cat Who with the comfort and anticipation that one feels when going home from a vacation abroad or a long weekend down the road. Together with other familiar toilers in the field of cozies, particularly Jessica Fletcher of Murder, She Wrote fame (although a TV series, these stories also were mostly set in the same small New England town of Cabot Cove), the cozies seemed to be a female preserve which would be fitting for its kinder, gentler approach to solving crimes. Perhaps that also accounts for the preference for Miss Marple, but one would be crazy to exclude the Poirot stories.

So too, I say, it would be insane to exclude Rex Stout's marvelous Nero Wolfe with his seventh of a ton avoirdupois, personal chef and personal gardener and orchid collection (I don't recall any reference at all to cymbidiums). Like Poirot, Wolfe had a male assistant, Archie Goodwin who introduces himself several times quite amiably as Wolfe's Man Friday-Saturday-Sunday-Monday-Tuesday-Wednesday-and-Thursday. Stout's Fer de Lance initiated his series in 1934. I am happy to say that one need not be ashamed to be reading Rex Stout these days. There seem to be web-sites devoted to keeping alive his work as well as related trivia.

All this is not to argue that tastes do not or should not change. The Girl Who series that made such an impact on the reading world a couple of years ago were absolutely brilliant writing. They should persuade any who need persuading that there is real evil in this world. Then we discovered that there is an entire universe of Scandinavian noir. At the same time, American TV seems to be inundated with police "procedurals", series on crime scene investigations or special units investigating heinous crimes as well as gory paranormal events.

I confess that my mind craves balance as well as authenticity. It rebels against the flood of noir mysteries as it does against spy novels full of vengeance or populated by self-righteous super heroes, even those who are rule-breakers because their motives are higher and purer. Perhaps I should admit that my prejudice is ESPECIALLY against those who believe their motives are higher and purer. Neither human society nor civilization itself is well served by the glorification of such characters. Just saying.

Published on June 22, 2013 15:13

May 22, 2013

Writing dialog

May 22, 2013

First, a clarification: Some people blog every day, and it is widely recommended that bloggers do so at least once a week. I must confess that I find once a month challenging. Twitter gets maybe one a week from me, so.... At any rate, I am sure those who follow or visit this blog have other sources of entertainment.

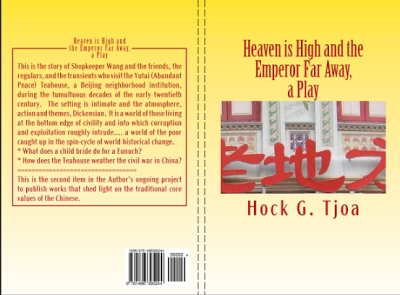

This blog is also a break from the build-up I have tried to give to the publication of The Chinese Spymaster , expected this summer. This blog does continue on the theme of a writer's education. I found in writing (translating and selecting) The Battle of Chibi that there were many passages that included dialog and thought it odd that some translations minimized this. At any rate, to coincide with the appearance of a (slightly) revised version of "Heaven is High and the Emperor is Far Away, a Play," my translation and adaptation of Lao She's Teahouse , I offer this blog on writing dialog. Following is the "proof" of the cover from Createspace:

First, dialog should not, in my view, mean that the rules of good grammar and spelling are suspended. Some authors seem to believe that this leads to inauthentic language. I think the true challenge in writing dialog is to write to the highest standards of correctness one can within the limits of credibility. The original Mandarin of Teahouse was, one is informed, an accurate rendering of Peking dialect. I have no idea how to convey that in English and therefore chose to write the dialog as "standard English" with a few exclamations--"wah" and "ai-ya"--that I hope act as sign-posts that the play does not take place, say, in Kansas.

I hasten to add that I would not wish to change a single syllable of Faulkner or Twain or Joyce, but my own modest thought about this is that there is entirely too much bad "dialect," that it is best left to experts, and that it is actually easier to write standard English.

As much as possible, dialog also enables the writer to show rather than to tell. This is not always the case as even in real life we gossip and exchange news in indirect speech. Friends get together and discuss, for example, the passing of some custom, practice, or of some other friend. But generally dialog enables the writer to show people arguing and quarreling as opposed to telling us about it. For writers, it is generally accepted that this is a good thing.

Dramatic dialog has the added requirement that it carries on at a good pace. Those who write plays and have watched them performed cringe at moments of "dead air." Often such moments can be covered up by more or less antic stage "business." But it is best that the dialog be crisply written (and that the actors remember their lines).

Like all writing, dialog should contribute to some point of the story whether this is the development of a character, the detailing of a plot element or the depiction of some action. Fellow writers who have difficulty with dialog are encouraged to try writing or adapting a play to get the appropriate workout.

(Details on purchasing the new revised version of "Heaven is High" may be found under the appropriate tab of this blog.)

First, a clarification: Some people blog every day, and it is widely recommended that bloggers do so at least once a week. I must confess that I find once a month challenging. Twitter gets maybe one a week from me, so.... At any rate, I am sure those who follow or visit this blog have other sources of entertainment.

This blog is also a break from the build-up I have tried to give to the publication of The Chinese Spymaster , expected this summer. This blog does continue on the theme of a writer's education. I found in writing (translating and selecting) The Battle of Chibi that there were many passages that included dialog and thought it odd that some translations minimized this. At any rate, to coincide with the appearance of a (slightly) revised version of "Heaven is High and the Emperor is Far Away, a Play," my translation and adaptation of Lao She's Teahouse , I offer this blog on writing dialog. Following is the "proof" of the cover from Createspace:

First, dialog should not, in my view, mean that the rules of good grammar and spelling are suspended. Some authors seem to believe that this leads to inauthentic language. I think the true challenge in writing dialog is to write to the highest standards of correctness one can within the limits of credibility. The original Mandarin of Teahouse was, one is informed, an accurate rendering of Peking dialect. I have no idea how to convey that in English and therefore chose to write the dialog as "standard English" with a few exclamations--"wah" and "ai-ya"--that I hope act as sign-posts that the play does not take place, say, in Kansas.

I hasten to add that I would not wish to change a single syllable of Faulkner or Twain or Joyce, but my own modest thought about this is that there is entirely too much bad "dialect," that it is best left to experts, and that it is actually easier to write standard English.

As much as possible, dialog also enables the writer to show rather than to tell. This is not always the case as even in real life we gossip and exchange news in indirect speech. Friends get together and discuss, for example, the passing of some custom, practice, or of some other friend. But generally dialog enables the writer to show people arguing and quarreling as opposed to telling us about it. For writers, it is generally accepted that this is a good thing.

Dramatic dialog has the added requirement that it carries on at a good pace. Those who write plays and have watched them performed cringe at moments of "dead air." Often such moments can be covered up by more or less antic stage "business." But it is best that the dialog be crisply written (and that the actors remember their lines).

Like all writing, dialog should contribute to some point of the story whether this is the development of a character, the detailing of a plot element or the depiction of some action. Fellow writers who have difficulty with dialog are encouraged to try writing or adapting a play to get the appropriate workout.

(Details on purchasing the new revised version of "Heaven is High" may be found under the appropriate tab of this blog.)

Published on May 22, 2013 12:23

April 20, 2013

Why and how I came to write a spy novel

For the past year I have been working on a spy novel that I hope will be published this July or August; I'd like to share with fellow authors the reasons why. It represents a change of genre--from translations or re-creations of traditional Chinese works to "espionage novels." There are two reasons: I like reading such novels and I wanted to find out if I could write one.

Almost at the very beginning of this exercise several ideas came to mind that have mostly been incorporated although not in the manner they had presented themselves. One of these, for instance, is the idea that the spy agency of one country might reach out to that of another .... But in addition to jotting these ideas down, I decided also to read or re-read spy novels to determine what I liked and what I would try to avoid.

It became very clear that the ideological issues that were so strongly felt by, say Helen McInnes, was not a working model for me. I do not consider the Iron Curtain relevant any longer or that democracy is locked in battle against communist or anarchist alternatives. Clearly, the leaders of many countries do not believe that historical inevitability will lead all countries to adopt a form of liberal democracy; the "Whig interpretation of history" is almost peculiarly Anglo-Saxon and the "Idea of Progress" is something that has a different ending envisioned by different cultures and civilizations. I do not believe that the civilized minds of the world in the near future will all turn out to be varieties of "Westernized Oriental Gentlemen."

It became very clear that the ideological issues that were so strongly felt by, say Helen McInnes, was not a working model for me. I do not consider the Iron Curtain relevant any longer or that democracy is locked in battle against communist or anarchist alternatives. Clearly, the leaders of many countries do not believe that historical inevitability will lead all countries to adopt a form of liberal democracy; the "Whig interpretation of history" is almost peculiarly Anglo-Saxon and the "Idea of Progress" is something that has a different ending envisioned by different cultures and civilizations. I do not believe that the civilized minds of the world in the near future will all turn out to be varieties of "Westernized Oriental Gentlemen."

Super-spies too, from Bond t0 Bourne, failed to impress me as suitable for anything other than escapist literature. They may make for good movies but not for good books, I decided. I could imagine well-trained agents who might perform as world class athletes, but did not want to write fantasies involving genetically enhanced or modified men and women saving the world from evil mutations. (I prefer to feed my fantasies with science fiction.) Too, I found myself offended by the school yard morality--he hit me first--that makes up the subtext of a great many pulp spy thrillers although vengeance has, I recognize, ancient roots.

It was impossible not to consider the work of John Le Carre; I think I have read at least once nearly every book he has published. But I confess to finding the world of espionage as he sees it somewhat eccentric; he concentrates almost exclusively on the inner monologues of the main character(s) who often distrust themselves not to mention their lack of faith in their colleagues. In the movie version of "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy" for instance, Smiley is seen to be thinking far more than he is speaking (in itself, not necessarily a bad thing). There is much to learn from Le Carre about writing and about spy-craft, but I wanted to write a spy novel involving the Chinese intelligence agency and the Chinese are not much given to introspection, except as acts of political self-criticism.

It was impossible not to consider the work of John Le Carre; I think I have read at least once nearly every book he has published. But I confess to finding the world of espionage as he sees it somewhat eccentric; he concentrates almost exclusively on the inner monologues of the main character(s) who often distrust themselves not to mention their lack of faith in their colleagues. In the movie version of "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy" for instance, Smiley is seen to be thinking far more than he is speaking (in itself, not necessarily a bad thing). There is much to learn from Le Carre about writing and about spy-craft, but I wanted to write a spy novel involving the Chinese intelligence agency and the Chinese are not much given to introspection, except as acts of political self-criticism.

There are very good spy novels set in or involving the agencies of the People's Republic that have been published recently. Though literate and filled with much well-researched details, they struck me as overly clever just as sometimes gymnasts become physical contortionists. I did not find any to serve as a model or inspiration for The Chinese Spymaster. This will I hope be the first in a series and so I have given it the working title of Operation Kashgar. I have chosen to ignore the usual spy novel themes of revenge and betrayal; instead there will be geopolitical considerations given the political restlessness in Central Asia and China's long "Inner Asian" borders.

Look for it about a month after the summer solstice.

Almost at the very beginning of this exercise several ideas came to mind that have mostly been incorporated although not in the manner they had presented themselves. One of these, for instance, is the idea that the spy agency of one country might reach out to that of another .... But in addition to jotting these ideas down, I decided also to read or re-read spy novels to determine what I liked and what I would try to avoid.

It became very clear that the ideological issues that were so strongly felt by, say Helen McInnes, was not a working model for me. I do not consider the Iron Curtain relevant any longer or that democracy is locked in battle against communist or anarchist alternatives. Clearly, the leaders of many countries do not believe that historical inevitability will lead all countries to adopt a form of liberal democracy; the "Whig interpretation of history" is almost peculiarly Anglo-Saxon and the "Idea of Progress" is something that has a different ending envisioned by different cultures and civilizations. I do not believe that the civilized minds of the world in the near future will all turn out to be varieties of "Westernized Oriental Gentlemen."

It became very clear that the ideological issues that were so strongly felt by, say Helen McInnes, was not a working model for me. I do not consider the Iron Curtain relevant any longer or that democracy is locked in battle against communist or anarchist alternatives. Clearly, the leaders of many countries do not believe that historical inevitability will lead all countries to adopt a form of liberal democracy; the "Whig interpretation of history" is almost peculiarly Anglo-Saxon and the "Idea of Progress" is something that has a different ending envisioned by different cultures and civilizations. I do not believe that the civilized minds of the world in the near future will all turn out to be varieties of "Westernized Oriental Gentlemen." Super-spies too, from Bond t0 Bourne, failed to impress me as suitable for anything other than escapist literature. They may make for good movies but not for good books, I decided. I could imagine well-trained agents who might perform as world class athletes, but did not want to write fantasies involving genetically enhanced or modified men and women saving the world from evil mutations. (I prefer to feed my fantasies with science fiction.) Too, I found myself offended by the school yard morality--he hit me first--that makes up the subtext of a great many pulp spy thrillers although vengeance has, I recognize, ancient roots.

It was impossible not to consider the work of John Le Carre; I think I have read at least once nearly every book he has published. But I confess to finding the world of espionage as he sees it somewhat eccentric; he concentrates almost exclusively on the inner monologues of the main character(s) who often distrust themselves not to mention their lack of faith in their colleagues. In the movie version of "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy" for instance, Smiley is seen to be thinking far more than he is speaking (in itself, not necessarily a bad thing). There is much to learn from Le Carre about writing and about spy-craft, but I wanted to write a spy novel involving the Chinese intelligence agency and the Chinese are not much given to introspection, except as acts of political self-criticism.

It was impossible not to consider the work of John Le Carre; I think I have read at least once nearly every book he has published. But I confess to finding the world of espionage as he sees it somewhat eccentric; he concentrates almost exclusively on the inner monologues of the main character(s) who often distrust themselves not to mention their lack of faith in their colleagues. In the movie version of "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy" for instance, Smiley is seen to be thinking far more than he is speaking (in itself, not necessarily a bad thing). There is much to learn from Le Carre about writing and about spy-craft, but I wanted to write a spy novel involving the Chinese intelligence agency and the Chinese are not much given to introspection, except as acts of political self-criticism.There are very good spy novels set in or involving the agencies of the People's Republic that have been published recently. Though literate and filled with much well-researched details, they struck me as overly clever just as sometimes gymnasts become physical contortionists. I did not find any to serve as a model or inspiration for The Chinese Spymaster. This will I hope be the first in a series and so I have given it the working title of Operation Kashgar. I have chosen to ignore the usual spy novel themes of revenge and betrayal; instead there will be geopolitical considerations given the political restlessness in Central Asia and China's long "Inner Asian" borders.

Look for it about a month after the summer solstice.

Published on April 20, 2013 15:25

March 9, 2013

How and Why The Battle of Chibi was written

March 9, 2013

Lao She, author of Tea HouseAbout ten years ago, I complained to a group of friends that I found reading the Romance of the Three Kingdoms boring. I had thought it would fill a gap in my education and had sought out the latest and greatest English translation. One of my friends, a Japanese, protested that this was her father's favorite book, that many Japanese have read several translations of this Chinese classic even as younger generations knew it chiefly from manga or computer games.

Lao She, author of Tea HouseAbout ten years ago, I complained to a group of friends that I found reading the Romance of the Three Kingdoms boring. I had thought it would fill a gap in my education and had sought out the latest and greatest English translation. One of my friends, a Japanese, protested that this was her father's favorite book, that many Japanese have read several translations of this Chinese classic even as younger generations knew it chiefly from manga or computer games.Two or three years later, overtaken by retirement, I undertook to study Mandarin. I soon found the usual exercises in the usual text books quite dull and decided to take on some "real stuff." Lao She's Tea House (茶館), written in the Beijing vernacular (although the author was a Manchu) lured me with its deceptively simple language; the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, I thought, could not be all that much more difficult.

I hasten to add that I would never have progressed to this stage without the remarkable software developed by Pleco (link) that combines access to several Chinese-English dictionaries with recognition of Chinese graphs as they are handwritten on the touch screen of a personal digital assistant. Even so, the Romance is 120 chapters and over a thousand pages long (in English). Further, although the Three Kingdoms period of Chinese history dates from 220 to 280 A.D., the Romance actually starts with the fall of the Han Dynasty (around 180 A.D.); by chapter 50, it is still preoccupied with the battle of Chibi that took place in 208 A.D.

A friend who is better versed in East Asian history explained that this Battle was pivotal to the character of the Three Kingdoms as it ensured that China would not be united during this period due to the stand-off among the three contenders for leadership. This gave me pause and the excuse to bring some "unity" to the project. The result is the selection and translation of 23 chapters ending before the Three Kingdoms period actually begins. I also eliminated names that were not associated with a speech or an any action. This would, as I envisioned it, transform the "shaggy dog" character of the classic to a novel that contained enough action, debate and stratagem as well as instances of heroism and stupidity that have made the Romance what it is--the best introduction to classical Chinese thought.

I did not try to create a novel with anything like Aristotelian unity of form or action, only a story with a beginning, middle and end. The Chinese text contained much dramatic dialog that I tried to reproduce. It contained much poetry which I initially avoided (as I do not think there is a single poetic bone in my body) until I chanced upon Archie Barnes' brilliant book, Chinese Through Poetry published posthumously in 2007. Working through this book gave me the courage to attempt the translation of the poetry I felt was essential for The Battle of Chibi; it also boosted my spirit through the final stages of writing.

I did not try to create a novel with anything like Aristotelian unity of form or action, only a story with a beginning, middle and end. The Chinese text contained much dramatic dialog that I tried to reproduce. It contained much poetry which I initially avoided (as I do not think there is a single poetic bone in my body) until I chanced upon Archie Barnes' brilliant book, Chinese Through Poetry published posthumously in 2007. Working through this book gave me the courage to attempt the translation of the poetry I felt was essential for The Battle of Chibi; it also boosted my spirit through the final stages of writing.This is a story I have told a few times in different ways, in response to those who were kind enough to ask about the making of this book. For the record, this is how and why I came to select from the Romance and translate what became The Battle of Chibi (link).

Published on March 09, 2013 16:15

January 22, 2013

MICHENER'S CARAVANS

Published in 1963 and set in 1946-7 (before the Partition of India), this book reminds us what a great investigator and thoughtful writer Michener was. The story itself is outmoded and Michener does not show great insight into the psychology of his characters. But one wonders if anyone in "exceptional" America read it when Charlie Wilson went to arm the Taliban against the Soviet supported regime, when soldiers were sent after 9/11 only to remain there for more than a dozen years.

Published in 1963 and set in 1946-7 (before the Partition of India), this book reminds us what a great investigator and thoughtful writer Michener was. The story itself is outmoded and Michener does not show great insight into the psychology of his characters. But one wonders if anyone in "exceptional" America read it when Charlie Wilson went to arm the Taliban against the Soviet supported regime, when soldiers were sent after 9/11 only to remain there for more than a dozen years. The author described Kabul as resembling Palestine in Jesus' day, of death by stoning, of an eye for an eye and a life for a life, of the fate of the country to be determined--whenever Afghanistan might be left to itself--by the struggle between the many bearded men led by mullahs from the hills and the few young experts with degrees from Oxford, Sorbonne or MIT, the former making up 99.99 percent of the country.

"We are a brigand society and we murder our rulers," says one of the characters. There are indeed striking descriptions of a violent and very different society that has very likely not changed much except that the munitions have multiplied, the mullahs reinforced with money and ideology from an even more fundamentalist source, and the young experts very likely all killed, corrupted or disenchanted. It is a quiet book and does not address itself to the political issues. It muses on the fact that the Afghans look so much like the Jews and thought of themselves as one of the "lost tribes"; they rejoiced equally when the Germans proclaimed them the First Aryans.

Michener's story also gives prominence to wanderers who traded goods (perhaps stolen) and made annual migrations with their goats and camels between the Oxus (now in Turkmenistan) and Jhelum (now in Pakistan), a trek of two thousand miles. Were they Povindahs? Kochis? Whatever, they were the gypsies of Central Asia. The author tells of the Desert of Death that lies between Iran and Afghanistan and of the mysterious City at the border. The heat and absence of humidity of the desert were such that the Helmand River flows into the desert and simply disappears.

The most ambitious among the Afghans in this book wants to build a dam and transform the desert gradually into farmland. He even explores the ancient karez tunnels that were sunk deep into the ground to bring up water; such tunnels may have had Persian origins and are to be found all the way from Iran and Pakistan through Afghanistan to the desert town of Turpan in Western China. Some years ago, I read a whole bunch of books on the Silk Road as if in a trance. The romantic caravan trails they described, I learn now from Michener, crossed at Kabul.

Published on January 22, 2013 17:36

January 2, 2013

RED SORGHUM

This is a bold, brash, bawdy and brilliant work. Purporting to be a family chronicle that the narrator obtains from a 92 year old woman from his family village, it tells of his brave, lusty and larger than life grandparents and their turbulent existence carving out a life in the midst of a northern Chinese region infested with bandits, opium smokers and gamblers, and invaded by the Japanese. There are horrific scenes of brutality: second grandma (thereon hangs another tale) and young auntie were raped and mutilated, Uncle Arhat was skinned alive before being dismembered, Grandpa himself murdered Grandma's newly-wed husband and father-in-law (you simply have to read this book).

This is a bold, brash, bawdy and brilliant work. Purporting to be a family chronicle that the narrator obtains from a 92 year old woman from his family village, it tells of his brave, lusty and larger than life grandparents and their turbulent existence carving out a life in the midst of a northern Chinese region infested with bandits, opium smokers and gamblers, and invaded by the Japanese. There are horrific scenes of brutality: second grandma (thereon hangs another tale) and young auntie were raped and mutilated, Uncle Arhat was skinned alive before being dismembered, Grandpa himself murdered Grandma's newly-wed husband and father-in-law (you simply have to read this book).The author paints his scenes in vivid language: the red sorghum of the title itself refers to the hardy grain that shimmered in fields like a "sea of blood"; dancing, it "reeked of glory; cold and graceful, it promised enchantment; passionate and loving, it was tumultuous." The narrator felt a pang on a return visit, finding the fields planted with a hybrid variety of sorghum that never seemed to ripen (guaranteed to cause constipation); he was haunted by "a nagging sense of our species' regression."

Though Grandma died in the main battle told, that of the Black Water River with several bands of Chinese ill-coordinated against the Japanese, she was the heroine--lovely as foot-binding had reduced her feet to three inch "lotuses" so that when she walked, "her body swayed like a willow in the wind," and as opium-smoking short of addiction had given her "the complexion of a peach, a sunny disposition and a clear mind." She died unafraid but unwillingly; unafraid of the eighteen levels of Hell that everyone knew about but unwilling to let go of life.

The novel covers much more--a digression into the marauding packs of dogs almost has the dogs taking on the voice of the narrator; a survivor of the war who lives on into the middle of the 20th century, Old Eighteen Stabs Geng who lived despite those wounds because of the magical ministrations of a silver fox, succumbs to starvation when his pension is held up by a petty bureaucrat.

Should the author have put more energy into decrying such evil? This reviewer will not judge, only saying this--that it would have been criminal not to have written this book or to have published it. Yes, the story line is not chronologically straightforward and often jerks like the handheld videocams of journalists embedded in some war. So what? The Nobel was well earned.

For some context, I read Red Sorghum just after reading Anchee Min's Empress Orchid about which I wrote (in a review posted on Amazon.com):

This novel about the last Empress Dowager of China as a young concubine in the late Qing dynasty is smoothly told. She pays attention to palace politics and learns about the wider world though her eunuchs, the emperor she serves and his half brother. When she bears the Emperor a son, she is elevated to the position of Empress, only she has to share that position as there is already one. But never mind, it happens to be her best friend among occupants of the harem.

This novel about the last Empress Dowager of China as a young concubine in the late Qing dynasty is smoothly told. She pays attention to palace politics and learns about the wider world though her eunuchs, the emperor she serves and his half brother. When she bears the Emperor a son, she is elevated to the position of Empress, only she has to share that position as there is already one. But never mind, it happens to be her best friend among occupants of the harem. Orchid must also face down and defeat the dying Emperor's most powerful advisor. (One does not learn why he chose to make an enemy of her.) China's humiliation at the hands of the barbarians penetrates into the harem somehow and Orchid chooses to support the uncle of her son the next Emperor. Throughout the book, the prose is smooth and chaste, bloodless, even when people died. An interesting read.

As Maureen Dowd complained after an editorial colleague at the New York Times won the Nobel Prize (for Economics) this is hardly a fair comparison. It is not. Some people love Goya's paintings, especially those he did of Spanish royalty. There is an air, a style about them. But it is difficult to pay heed when there is a Guernica in the same room.

Published on January 02, 2013 17:43

December 22, 2012

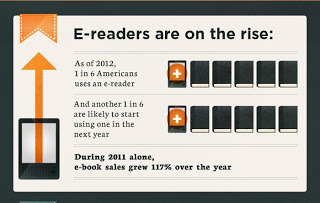

BOOKS--print or digital

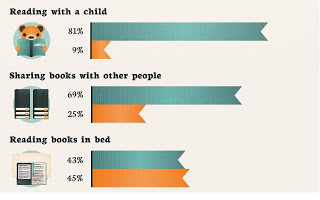

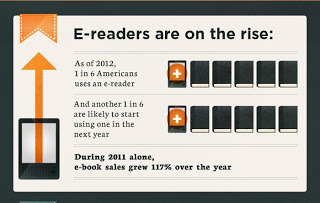

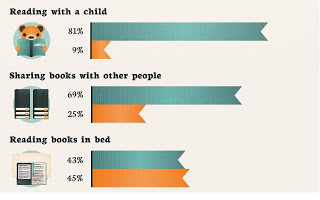

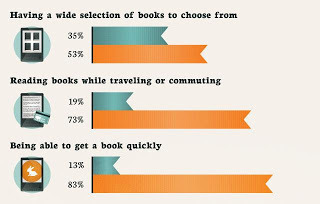

The website TEACHINGDEGREE.ORG, from which the graphics of this blog have been obtained, is clear about this. There are more and more e-readers out there:

The shopping frenzy of the last few weeks--perhaps it continues--must surely have driven that point home. But there is good news; this does not spell the end of real books.

The shopping frenzy of the last few weeks--perhaps it continues--must surely have driven that point home. But there is good news; this does not spell the end of real books.

As it turns out, those who own an e-reader are likely to read more, even of books in print form.

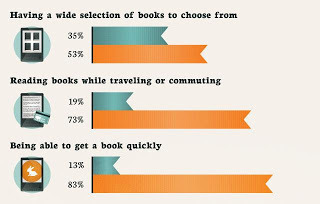

For those who care that we do not slouch our way into illiteracy, this is a good thing. In addition there some circumstances, if one thinks about it, in which one form of books work better than others:

Reading with a child, for example, is best done with a book in print, while the great convenience of having many books in a small thin device makes travelling with a whole library best done with an e-Reader. (In any case, illustrated children's books test the current limits of e-publication.)

However one looks at it, this holiday season--here's to Books!

The shopping frenzy of the last few weeks--perhaps it continues--must surely have driven that point home. But there is good news; this does not spell the end of real books.

The shopping frenzy of the last few weeks--perhaps it continues--must surely have driven that point home. But there is good news; this does not spell the end of real books. As it turns out, those who own an e-reader are likely to read more, even of books in print form.

For those who care that we do not slouch our way into illiteracy, this is a good thing. In addition there some circumstances, if one thinks about it, in which one form of books work better than others:

Reading with a child, for example, is best done with a book in print, while the great convenience of having many books in a small thin device makes travelling with a whole library best done with an e-Reader. (In any case, illustrated children's books test the current limits of e-publication.)

However one looks at it, this holiday season--here's to Books!

Published on December 22, 2012 11:38