Hock G. Tjoa's Blog, page 5

August 26, 2015

Warren Dean's review

The following is Warren Dean's review of Agamemnon Must Die, reproduced from Goodreads (link) with his permission.

***

This is the story of what happens when King Agamemnon returns from the Greek conquest of Troy.

For ten years, his queen Clytemnestra has been nursing her hatred of Agamemnon for sacrificing their daughter Iphigenia at the beginning of the Trojan campaign. In her husband's long absence, she has taken his cousin Aigisthos as her consort. Aigisthos loves her unconditionally and is easily persuaded to help her kill the king.

After the deed is done, the story becomes that of Orestes, son of Agamemnon and heir to the throne. Honour and tradition require him to avenge himself on his father's killers, but is it really in his nature to do so?

In this re-telling of the tale, all of the characteristics of Greek tragedy are faithfully preserved. Mortal heroes and heroines struggle to reconcile lofty ambitions, innate character flaws, and the dictates of love, while immortal gods and goddesses manipulate them to further their own schemes and petty squabbles.

However, that is not all there is to the novel; the central storyline is overlaid with subtle facets which engage the reader on different levels. For example, Aigisthos' backstory makes him a noble character whose motives the reader can sympathise with. And Orestes' inner struggle is what makes him susceptible to Apollo's attempts to coerce him to act contrary to his nature.

The supernatural element of the story is prefaced by some of the mortals openly questioning society's belief in the literal existence of the gods. This gives the reader an insight into what motivates the likes of Apollo, Hermes, and the Furies to compel mortals to do their bidding. The gods' very existence is at stake; if the values and traditions that define them are abandoned, they themselves will fade into oblivion.

This theme culminates in an enthralling debate between the Furies, who want to maintain the power of the gods, and Athena, who wants to end the cycle of violence begun by Agamemnon's murder of his own daughter. Athena's stance is a fascinating one; in proposing to supplant the supreme authority of the gods with the rule of law, she is advocating her own eventual demise. The Furies' make an apposite observation in response: "This is too new for us. We grasp not the reason nor the desired outcome. Do you think to make men good by enacting more laws?"

Good question.

Good story.

(I received a free copy of this story in exchange for an honest, non-reciprocal review.)

***

I have reproduced the review exactly as written, not only because Warren thinks it is worth four stars out of five, but also for his reaction to the ending of the book--the "supernatural element," the debate between the new gods and the old, the Olympians versus the Fates. This occupies almost all of the last third of Aeschylus' trilogy. It was for him and fifth century B.C. Athens a vital debate.

It was also the hardest to write/retell. Nothing happens; it is a long argument. I chose to write this confrontation in verse with the Olympians speaking in a different meter from the Fates. I imagine that usually eyes glaze at this point. A debate between the new morality and the old, the new set of beliefs that make sense of life versus the old.

How refreshing that a reviewer finds this "an enthralling debate"!

***

This is the story of what happens when King Agamemnon returns from the Greek conquest of Troy.

For ten years, his queen Clytemnestra has been nursing her hatred of Agamemnon for sacrificing their daughter Iphigenia at the beginning of the Trojan campaign. In her husband's long absence, she has taken his cousin Aigisthos as her consort. Aigisthos loves her unconditionally and is easily persuaded to help her kill the king.

After the deed is done, the story becomes that of Orestes, son of Agamemnon and heir to the throne. Honour and tradition require him to avenge himself on his father's killers, but is it really in his nature to do so?

In this re-telling of the tale, all of the characteristics of Greek tragedy are faithfully preserved. Mortal heroes and heroines struggle to reconcile lofty ambitions, innate character flaws, and the dictates of love, while immortal gods and goddesses manipulate them to further their own schemes and petty squabbles.

However, that is not all there is to the novel; the central storyline is overlaid with subtle facets which engage the reader on different levels. For example, Aigisthos' backstory makes him a noble character whose motives the reader can sympathise with. And Orestes' inner struggle is what makes him susceptible to Apollo's attempts to coerce him to act contrary to his nature.

The supernatural element of the story is prefaced by some of the mortals openly questioning society's belief in the literal existence of the gods. This gives the reader an insight into what motivates the likes of Apollo, Hermes, and the Furies to compel mortals to do their bidding. The gods' very existence is at stake; if the values and traditions that define them are abandoned, they themselves will fade into oblivion.

This theme culminates in an enthralling debate between the Furies, who want to maintain the power of the gods, and Athena, who wants to end the cycle of violence begun by Agamemnon's murder of his own daughter. Athena's stance is a fascinating one; in proposing to supplant the supreme authority of the gods with the rule of law, she is advocating her own eventual demise. The Furies' make an apposite observation in response: "This is too new for us. We grasp not the reason nor the desired outcome. Do you think to make men good by enacting more laws?"

Good question.

Good story.

(I received a free copy of this story in exchange for an honest, non-reciprocal review.)

***

I have reproduced the review exactly as written, not only because Warren thinks it is worth four stars out of five, but also for his reaction to the ending of the book--the "supernatural element," the debate between the new gods and the old, the Olympians versus the Fates. This occupies almost all of the last third of Aeschylus' trilogy. It was for him and fifth century B.C. Athens a vital debate.

It was also the hardest to write/retell. Nothing happens; it is a long argument. I chose to write this confrontation in verse with the Olympians speaking in a different meter from the Fates. I imagine that usually eyes glaze at this point. A debate between the new morality and the old, the new set of beliefs that make sense of life versus the old.

How refreshing that a reviewer finds this "an enthralling debate"!

Published on August 26, 2015 16:46

August 20, 2015

Salman Rushdie, Midnight's Children

"To understand just one life, you have to swallow the world. I told you that," declared the author flatly through his narrator, Saleem Sinai, who was born on the stroke of midnight August 15, 1947 at the same instant that India was given its independence.

"There was an extra festival on the calendar, a new myth to celebrate, because a nation which had never previously existed was about to win its freedom, catapulting us into a world which, although it had five thousand years of history, although it had invented the game of chess and traded with Middle Kingdom Egypt, was nevertheless quite imaginary ... a mythical land, a country which would never exist except by the efforts of a phenomenal collective will--except in a dream we all agree to dream ... a mere fantasy shared in varying degrees by Bengali and Punjabi, Madrasi and Jat ... India a collective fiction in which anything was possible, a fable rivaled only by the two other mighty fantasies: money and God."

Thus, with wit, style, and erudition, Rushdie has his narrator usher that event, acknowledging the roles of a dying Jinnah who desired to witness the creation of Pakistan during his lifetime and of Mountbatten with his "extraordinary haste." Was it because the British believed there might be substance to the rumors that Hindus and Muslims had started to work on a resolution of their differences and feared a successful new nation where Britannia had ruled by division?

Thus, with wit, style, and erudition, Rushdie has his narrator usher that event, acknowledging the roles of a dying Jinnah who desired to witness the creation of Pakistan during his lifetime and of Mountbatten with his "extraordinary haste." Was it because the British believed there might be substance to the rumors that Hindus and Muslims had started to work on a resolution of their differences and feared a successful new nation where Britannia had ruled by division?

Those who prefer their fiction separated, like yokes from whites, from mere political history must suffer through much in this blockbuster, from the massacre at Amritsar, through the shenanigans of pro versus anti Muslim Leaguers, through comparisons between Nasser and Nehru, between Indian and Pakistani troops, actions in Kashmir and so on, as if to the last syllable of recorded time.

William Methwold, the departing expatriate who sold to the narrator's parents Methwold Estates in Bombay, whinged that the British had provided "hundreds of years of decent government ... built your roads. [We bequeathed India with] schools, trains, the parliamentary system. The Taj Mahal was falling down until an Englishman bothered to see to it."

But Reverend Mother (the narrator's grandmother) noticed that there was no water near the pot. "I never believed, but it's true, my God, they wipe their bottoms with paper only." Magna Carta, habeas corpus, and Shakespeare notwithstanding, the British Empire remained in her eyes as the great unwashed.

Rushdie's exuberant and eloquent stories set this blockbuster aside from Virgil's constipated and politically correct epic of the rise of Rome/Augustus or Tennyson's prissy, labored homilies that celebrated English greatness. Instead, from Tal, Aadam Aziz (the narrator's putative grandfather), heard many stories, "endless verbiage which made others think him cracked." The boatman of Kashmir told the tallest of tall tales: "listen, nakoo. I saw that Isa, that Christ, when he came to Kashmir, beard down to his balls, bald as an egg, old and fagged out."

But the narrator was ecumenical in his casual references to religious figures. He compared his own visions to those of Mohammed ("on whose name be peace -- I don't want to offend anyone") who had been commanded to Recite and received for his confusion the comfort and reassurance of family and friends that he had been singled out as the Messenger. The narrator, on the other hand, saw "the shawl of genius fluttering down, like an embroidered butterfly, the mantle of greatness settling on my shoulders." In an aside he explains a cozy reference to elephant-headed Ganesh, "despite my Muslim background, I'm enough of a Bombayite to be well up in Hindu stories."

Myth, politics, a cunningly contrived plot, almost overwhelms the imaginative, inventive, and most enchanting language. The Sinai family fed upon Reverend Mother's "curries and meatballs of intransigence"; Amina ate the "fish salans of stubbornness and biryanis of determination." Mary Pereira made them "pickles of guilt and fear of discovery."

This may very well be the Great Indian Novel. There is that air about it, but it may have been too clever.

"There was an extra festival on the calendar, a new myth to celebrate, because a nation which had never previously existed was about to win its freedom, catapulting us into a world which, although it had five thousand years of history, although it had invented the game of chess and traded with Middle Kingdom Egypt, was nevertheless quite imaginary ... a mythical land, a country which would never exist except by the efforts of a phenomenal collective will--except in a dream we all agree to dream ... a mere fantasy shared in varying degrees by Bengali and Punjabi, Madrasi and Jat ... India a collective fiction in which anything was possible, a fable rivaled only by the two other mighty fantasies: money and God."

Thus, with wit, style, and erudition, Rushdie has his narrator usher that event, acknowledging the roles of a dying Jinnah who desired to witness the creation of Pakistan during his lifetime and of Mountbatten with his "extraordinary haste." Was it because the British believed there might be substance to the rumors that Hindus and Muslims had started to work on a resolution of their differences and feared a successful new nation where Britannia had ruled by division?

Thus, with wit, style, and erudition, Rushdie has his narrator usher that event, acknowledging the roles of a dying Jinnah who desired to witness the creation of Pakistan during his lifetime and of Mountbatten with his "extraordinary haste." Was it because the British believed there might be substance to the rumors that Hindus and Muslims had started to work on a resolution of their differences and feared a successful new nation where Britannia had ruled by division?Those who prefer their fiction separated, like yokes from whites, from mere political history must suffer through much in this blockbuster, from the massacre at Amritsar, through the shenanigans of pro versus anti Muslim Leaguers, through comparisons between Nasser and Nehru, between Indian and Pakistani troops, actions in Kashmir and so on, as if to the last syllable of recorded time.

William Methwold, the departing expatriate who sold to the narrator's parents Methwold Estates in Bombay, whinged that the British had provided "hundreds of years of decent government ... built your roads. [We bequeathed India with] schools, trains, the parliamentary system. The Taj Mahal was falling down until an Englishman bothered to see to it."

But Reverend Mother (the narrator's grandmother) noticed that there was no water near the pot. "I never believed, but it's true, my God, they wipe their bottoms with paper only." Magna Carta, habeas corpus, and Shakespeare notwithstanding, the British Empire remained in her eyes as the great unwashed.

Rushdie's exuberant and eloquent stories set this blockbuster aside from Virgil's constipated and politically correct epic of the rise of Rome/Augustus or Tennyson's prissy, labored homilies that celebrated English greatness. Instead, from Tal, Aadam Aziz (the narrator's putative grandfather), heard many stories, "endless verbiage which made others think him cracked." The boatman of Kashmir told the tallest of tall tales: "listen, nakoo. I saw that Isa, that Christ, when he came to Kashmir, beard down to his balls, bald as an egg, old and fagged out."

But the narrator was ecumenical in his casual references to religious figures. He compared his own visions to those of Mohammed ("on whose name be peace -- I don't want to offend anyone") who had been commanded to Recite and received for his confusion the comfort and reassurance of family and friends that he had been singled out as the Messenger. The narrator, on the other hand, saw "the shawl of genius fluttering down, like an embroidered butterfly, the mantle of greatness settling on my shoulders." In an aside he explains a cozy reference to elephant-headed Ganesh, "despite my Muslim background, I'm enough of a Bombayite to be well up in Hindu stories."

Myth, politics, a cunningly contrived plot, almost overwhelms the imaginative, inventive, and most enchanting language. The Sinai family fed upon Reverend Mother's "curries and meatballs of intransigence"; Amina ate the "fish salans of stubbornness and biryanis of determination." Mary Pereira made them "pickles of guilt and fear of discovery."

This may very well be the Great Indian Novel. There is that air about it, but it may have been too clever.

Published on August 20, 2015 18:13

August 11, 2015

The Handmaid's Tale (of woe)

It is odd that Margaret Atwood's most famous novel, which many consider her best, should have won the Arthur C. Clarke Award in 1987 for the best work of science fiction published in the United Kingdom (during the previous year). She herself thought of The Handmaid's Tale and Oryx and Crake (published in 2003) as "speculative" or "social science fiction." In a few places, it has also been referred to as a "thriller"; it might be that, if one could conceive of a Hitchcock movie with the sound turned off as thrilling.

Handmaids in the Republic of Gilead perform their function in the coldest, starkest, most denatured interpretation of Rachel's request to Jacob: "Behold my maid ... go in unto her, and she shall bear upon my knees, that I may also have children by her." To call the society of The Republic of Gilead puritanical is a slander on the Puritans. An reference to Victoria's alleged advice to her daughter (perhaps to everyone of them married off): "just close your eyes and think about England," is more like it.

"A shape, red with white wings around the face, a shape like mine, a nondescript woman in red carrying a basket, comes along the brick sidewalk towards me. She reaches me and we peer at each other's faces, looking down the white tunnels of cloth that enclose us. She is the right one." Thus a mood of paranoia that swirls around the handmaiden is conveyed. The Eyes are watching. The Guardians are barely to be trusted. A woman was shot for fumbling in her clothes. "They" thought she might have a bomb. She had not even been a handmaid or a Wife or an "econo-wife," but a Martha.

The handmaiden slept in "what had once been the gymnasium... I thought I could smell, faintly like an afterimage, the pungent scent of sweat... Dances would have been held there; the music lingered, a palimpsest of unheard sound... There was old sex in the room and loneliness."

Alas, the way of a man with a woman, told in this Tale from the Maid's point of view is bleached of all sentiment, denuded of lust, and bleak, bleak, bleak. It has the intimacy and arousal of a gynecological examination. Even a society like that portrayed in A Thousand Splendid Suns, devoid of any notion of romantic love, betrays more feeling, more affection.

I wish, said the Handmaid, this story were "about love, or sudden realizations important to one's life, or even about sunsets and birds, rainstorms or snow... I'm sorry there is so much pain in this story... But I keep on going with this sad and hungry and sordid, this limping and mutilated story."

I wish, said the Handmaid, this story were "about love, or sudden realizations important to one's life, or even about sunsets and birds, rainstorms or snow... I'm sorry there is so much pain in this story... But I keep on going with this sad and hungry and sordid, this limping and mutilated story."

"Our sweetest songs," a Romantic poet once said, "are those that tell of saddest thoughts." The thoughts in this story are sad beyond bearing, but the songs are far from sweet. The writing in this volume may indeed be better than that in The Year of the Flood, but I found the later novel, dark and weird as it might seem, more life-affirming.

Handmaids in the Republic of Gilead perform their function in the coldest, starkest, most denatured interpretation of Rachel's request to Jacob: "Behold my maid ... go in unto her, and she shall bear upon my knees, that I may also have children by her." To call the society of The Republic of Gilead puritanical is a slander on the Puritans. An reference to Victoria's alleged advice to her daughter (perhaps to everyone of them married off): "just close your eyes and think about England," is more like it.

"A shape, red with white wings around the face, a shape like mine, a nondescript woman in red carrying a basket, comes along the brick sidewalk towards me. She reaches me and we peer at each other's faces, looking down the white tunnels of cloth that enclose us. She is the right one." Thus a mood of paranoia that swirls around the handmaiden is conveyed. The Eyes are watching. The Guardians are barely to be trusted. A woman was shot for fumbling in her clothes. "They" thought she might have a bomb. She had not even been a handmaid or a Wife or an "econo-wife," but a Martha.

The handmaiden slept in "what had once been the gymnasium... I thought I could smell, faintly like an afterimage, the pungent scent of sweat... Dances would have been held there; the music lingered, a palimpsest of unheard sound... There was old sex in the room and loneliness."

Alas, the way of a man with a woman, told in this Tale from the Maid's point of view is bleached of all sentiment, denuded of lust, and bleak, bleak, bleak. It has the intimacy and arousal of a gynecological examination. Even a society like that portrayed in A Thousand Splendid Suns, devoid of any notion of romantic love, betrays more feeling, more affection.

I wish, said the Handmaid, this story were "about love, or sudden realizations important to one's life, or even about sunsets and birds, rainstorms or snow... I'm sorry there is so much pain in this story... But I keep on going with this sad and hungry and sordid, this limping and mutilated story."

I wish, said the Handmaid, this story were "about love, or sudden realizations important to one's life, or even about sunsets and birds, rainstorms or snow... I'm sorry there is so much pain in this story... But I keep on going with this sad and hungry and sordid, this limping and mutilated story." "Our sweetest songs," a Romantic poet once said, "are those that tell of saddest thoughts." The thoughts in this story are sad beyond bearing, but the songs are far from sweet. The writing in this volume may indeed be better than that in The Year of the Flood, but I found the later novel, dark and weird as it might seem, more life-affirming.

Published on August 11, 2015 09:10

August 2, 2015

A giveaway on Amazon

I had never heard of such a thing until a couple of months ago. I have never considered such a thing until a couple of weeks ago.

But now I have done it. Anxiously following Amazon's hints and prompts, I have taken another small step in self-promotion and set up an Amazon Giveaway of https://giveaway.amazon.com/p/4ba0b754232f5654

I hope any of my followers or anyone happening on this blog will take the opportunity to try to win a copy (the Giveaway is limited to print versions only.)

I hope any of my followers or anyone happening on this blog will take the opportunity to try to win a copy (the Giveaway is limited to print versions only.)

Please do let me know by comment on this blog or Twitter (@hgtjoa) if your experience was pleasant.

Thanks!

But now I have done it. Anxiously following Amazon's hints and prompts, I have taken another small step in self-promotion and set up an Amazon Giveaway of https://giveaway.amazon.com/p/4ba0b754232f5654

I hope any of my followers or anyone happening on this blog will take the opportunity to try to win a copy (the Giveaway is limited to print versions only.)

I hope any of my followers or anyone happening on this blog will take the opportunity to try to win a copy (the Giveaway is limited to print versions only.)Please do let me know by comment on this blog or Twitter (@hgtjoa) if your experience was pleasant.

Thanks!

Published on August 02, 2015 17:42

July 27, 2015

Will China move to a "Two-Child Policy"?

On July 23 this year, China Daily reported that the National Health and Planning Commission of the People's Republic denied media suggestions that such a policy would be implemented by 2016. (See chinadaily.com.cn/china/2015-07/23/ and, the Great Firewall willing, you can read the article for yourself.) In 2013, there was a relaxation of the one-child policy to allow couples of which one spouse is a only child to have a second child. Eleven million couples qualified.

The debate around this Chinese policy has centered, among Westerners, on issues of human rights and reproductive freedom. I have a j'ne sais quoi feeling about this.

The debate around this Chinese policy has centered, among Westerners, on issues of human rights and reproductive freedom. I have a j'ne sais quoi feeling about this.

Among Chinese policy makers, one suspects, it has to do with how the nation proposes to feed its people and, lately, how its society will take care of its aging population. The chart to the left of China's estimated population by age group shows the stark truth that in 30 years, those currently aged 40 and above will be much larger than those currently aged 70 and above while their replacements, those currently aged ten to thirty-nine will be much smaller. The math is inexorable and the social prospects grim. A much smaller working population will have to support a much larger number of seniors.

[An acknowledgement is necessary: The image is by the Pardee Center for International Futures [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons.]

There is another dimension of this issue that has not surfaced but which is alluded to in a passage in The Ninja and the Diplomat, vol. 2 of The Chinese Spymaster, expected to be published in September this year. One character addressed another as "uncle" as respectful Chinese traditionally did (perhaps still do) when speaking to someone older and/or of higher status. The man thus addressed is touched because -

"As an unintended but ineluctable consequence of the one child policy, he and his wife, like most of his generation and those succeeding, consisted of only children; hence his family included no aunts or uncles, no cousins, and no nieces or nephews. The Chinese family had lost an immeasurable dimension of comfort."

The debate around this Chinese policy has centered, among Westerners, on issues of human rights and reproductive freedom. I have a j'ne sais quoi feeling about this.

The debate around this Chinese policy has centered, among Westerners, on issues of human rights and reproductive freedom. I have a j'ne sais quoi feeling about this.Among Chinese policy makers, one suspects, it has to do with how the nation proposes to feed its people and, lately, how its society will take care of its aging population. The chart to the left of China's estimated population by age group shows the stark truth that in 30 years, those currently aged 40 and above will be much larger than those currently aged 70 and above while their replacements, those currently aged ten to thirty-nine will be much smaller. The math is inexorable and the social prospects grim. A much smaller working population will have to support a much larger number of seniors.

[An acknowledgement is necessary: The image is by the Pardee Center for International Futures [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons.]

There is another dimension of this issue that has not surfaced but which is alluded to in a passage in The Ninja and the Diplomat, vol. 2 of The Chinese Spymaster, expected to be published in September this year. One character addressed another as "uncle" as respectful Chinese traditionally did (perhaps still do) when speaking to someone older and/or of higher status. The man thus addressed is touched because -

"As an unintended but ineluctable consequence of the one child policy, he and his wife, like most of his generation and those succeeding, consisted of only children; hence his family included no aunts or uncles, no cousins, and no nieces or nephews. The Chinese family had lost an immeasurable dimension of comfort."

Published on July 27, 2015 07:21

July 22, 2015

Revision to The Chinese Spymaster - adding an image

In view of the forthcoming publication of The Ninja and the Diplomat, vol. 2 of The Chinese Spymaster, and in anticipation of renewed interest in volume 1 itself, I recently revised the text of The Chinese Spymaster.

The revision consisted primarily of eliminating typos and formatting issues as best I could. I have learned of course from reviewers about aspects readers found wanting. Several wished for more action and/or a faster pace; others thought the flashbacks and asides in the narrative or the dialogue distracting. I have taken these comments to heart, but I did not revise the book to reflect any of them. Flashbacks and asides need to be handled more adroitly, and I hope to have accomplished these matters of style in volume two. More or faster paced action, however, are not only a matter of taste but also a result of the author's vision. I did/do not wish to write with James Bond or the Bourne books/movies as my models. It is simply not how I visualize the Chinese spymaster and his colleagues.

The Ninja and the Diplomat will be tighter in narrative and action. Readers will soon learn that I have not written to a formula, although I hope the thoughtfulness and awareness of geopolitical as well as national political and security issues of the main characters remain. The areas of geographical interest have also changed. Volume 2 takes on China's maritime interests to the northeast and southeast of Asia. I have found maps to accompany the text that I hope will make those contentious areas visually clear to the reader.

The Ninja and the Diplomat will be tighter in narrative and action. Readers will soon learn that I have not written to a formula, although I hope the thoughtfulness and awareness of geopolitical as well as national political and security issues of the main characters remain. The areas of geographical interest have also changed. Volume 2 takes on China's maritime interests to the northeast and southeast of Asia. I have found maps to accompany the text that I hope will make those contentious areas visually clear to the reader.

In The Chinese Spymaster, volume 1, the intrigue was centered on Afghanistan and the ramifications were envisioned to spread through all the Central Asian "stans." It seemed desirable to include an image of the area to the book. Doing so for the Kindle version was more difficult than for the print version or in other e-book formats. I tried to follow Kindle's formatting style guide but failed initially. The Kindle community/forum, the last time I checked, did not have a thread discussing my problem although I find it hard to believe that I was the first to experience it. Fortunately, "Contact us" led to a very useful email exchange that cleared up the mystery for me.

For the benefit of other authors, the text (saved as a web-filtered file) and the image should not be upload in a single folder, nor in such a folder that has been compressed (zipped). The trick is to place the image in a folder and then to send both that folder and the (web-filtered) text to the "zip" function in Windows 7. (Sorry, I have no idea if this would work for other versions of Windows or for Macs.)

The map, originally called the Political Map of the Caucasus and Central Asia is a product of the CIA's work and is in the public domain. It is available from Wikimedia Commons.

The revision consisted primarily of eliminating typos and formatting issues as best I could. I have learned of course from reviewers about aspects readers found wanting. Several wished for more action and/or a faster pace; others thought the flashbacks and asides in the narrative or the dialogue distracting. I have taken these comments to heart, but I did not revise the book to reflect any of them. Flashbacks and asides need to be handled more adroitly, and I hope to have accomplished these matters of style in volume two. More or faster paced action, however, are not only a matter of taste but also a result of the author's vision. I did/do not wish to write with James Bond or the Bourne books/movies as my models. It is simply not how I visualize the Chinese spymaster and his colleagues.

The Ninja and the Diplomat will be tighter in narrative and action. Readers will soon learn that I have not written to a formula, although I hope the thoughtfulness and awareness of geopolitical as well as national political and security issues of the main characters remain. The areas of geographical interest have also changed. Volume 2 takes on China's maritime interests to the northeast and southeast of Asia. I have found maps to accompany the text that I hope will make those contentious areas visually clear to the reader.

The Ninja and the Diplomat will be tighter in narrative and action. Readers will soon learn that I have not written to a formula, although I hope the thoughtfulness and awareness of geopolitical as well as national political and security issues of the main characters remain. The areas of geographical interest have also changed. Volume 2 takes on China's maritime interests to the northeast and southeast of Asia. I have found maps to accompany the text that I hope will make those contentious areas visually clear to the reader.In The Chinese Spymaster, volume 1, the intrigue was centered on Afghanistan and the ramifications were envisioned to spread through all the Central Asian "stans." It seemed desirable to include an image of the area to the book. Doing so for the Kindle version was more difficult than for the print version or in other e-book formats. I tried to follow Kindle's formatting style guide but failed initially. The Kindle community/forum, the last time I checked, did not have a thread discussing my problem although I find it hard to believe that I was the first to experience it. Fortunately, "Contact us" led to a very useful email exchange that cleared up the mystery for me.

For the benefit of other authors, the text (saved as a web-filtered file) and the image should not be upload in a single folder, nor in such a folder that has been compressed (zipped). The trick is to place the image in a folder and then to send both that folder and the (web-filtered) text to the "zip" function in Windows 7. (Sorry, I have no idea if this would work for other versions of Windows or for Macs.)

The map, originally called the Political Map of the Caucasus and Central Asia is a product of the CIA's work and is in the public domain. It is available from Wikimedia Commons.

Published on July 22, 2015 15:56

July 17, 2015

The Ingenious Judge Dee gets an airing

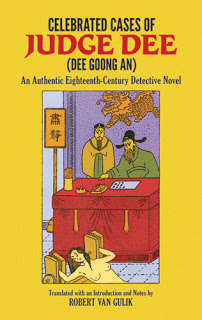

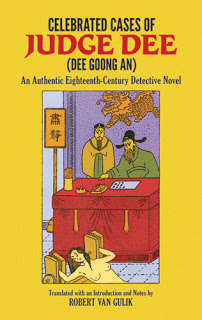

Some years ago, I asked around about Chinese detective stories and discovered that these were immensely popular in the vernacular literary form. In the eighteenth century, for example, stories were published about a Judge Dee. A print version was found by Robert van Gulik. During WW2, he used his leisure to translate them into English as The Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee, first published in 1949. He wrote then in an essay appended to that translation that he could easily imagine the Judge in new detective stories.

Thus he wrote The Chinese Maze Murders, The Chinese Bell Murders, and The Chinese Lake Murders. He had these translated into Japanese and Mandarin and published in the early 1950s before publishing them in English in 1957. These stories and several more subsequently attracted a loyal following fond of the cozy murder stories with the clever judge.

The Ingenious Judge Dee, a play, is an adaptation of The Celebrated Cases. I published the play in 2013 thinking that this would bring fresh appeal to the stories and also with the fond hope that fans of Judge Dee might some day be able to attend a performance and, as often ensues after such a group experience, be able to share their experience of the performance. I understand that a movie or two have been made based on the character and am aware that a video game featuring the Judge has recently been introduced in to the market.

The Ingenious Judge Dee, a play, is an adaptation of The Celebrated Cases. I published the play in 2013 thinking that this would bring fresh appeal to the stories and also with the fond hope that fans of Judge Dee might some day be able to attend a performance and, as often ensues after such a group experience, be able to share their experience of the performance. I understand that a movie or two have been made based on the character and am aware that a video game featuring the Judge has recently been introduced in to the market.

To my knowledge, the dramatic reading of Judge Dee will be the first such performance. It will take place in Nevada City, CA, on Thursday July 23, at 6.30. The venue is the lovely Miners Foundry.

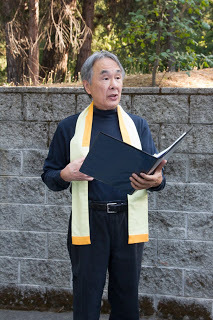

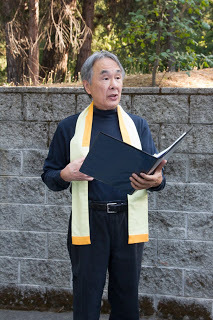

I have immodestly cast myself in the title role (pictured on the right) but have been fortunate that some friends from the local theater community will help playing the other roles in the play. Some of them will have more than one role, hence the various colored stoles or belts that we wear.

Photographs were taken by David Wong of David Wong Photography.

From left to right, Rene Sprattling, Dinah Smith, Brett Torgrimson, Hock, Drue Mathies, Lois Ewing and Eric Tomb.

Thus he wrote The Chinese Maze Murders, The Chinese Bell Murders, and The Chinese Lake Murders. He had these translated into Japanese and Mandarin and published in the early 1950s before publishing them in English in 1957. These stories and several more subsequently attracted a loyal following fond of the cozy murder stories with the clever judge.

The Ingenious Judge Dee, a play, is an adaptation of The Celebrated Cases. I published the play in 2013 thinking that this would bring fresh appeal to the stories and also with the fond hope that fans of Judge Dee might some day be able to attend a performance and, as often ensues after such a group experience, be able to share their experience of the performance. I understand that a movie or two have been made based on the character and am aware that a video game featuring the Judge has recently been introduced in to the market.

The Ingenious Judge Dee, a play, is an adaptation of The Celebrated Cases. I published the play in 2013 thinking that this would bring fresh appeal to the stories and also with the fond hope that fans of Judge Dee might some day be able to attend a performance and, as often ensues after such a group experience, be able to share their experience of the performance. I understand that a movie or two have been made based on the character and am aware that a video game featuring the Judge has recently been introduced in to the market.To my knowledge, the dramatic reading of Judge Dee will be the first such performance. It will take place in Nevada City, CA, on Thursday July 23, at 6.30. The venue is the lovely Miners Foundry.

I have immodestly cast myself in the title role (pictured on the right) but have been fortunate that some friends from the local theater community will help playing the other roles in the play. Some of them will have more than one role, hence the various colored stoles or belts that we wear.

Photographs were taken by David Wong of David Wong Photography.

From left to right, Rene Sprattling, Dinah Smith, Brett Torgrimson, Hock, Drue Mathies, Lois Ewing and Eric Tomb.

Published on July 17, 2015 13:31

July 9, 2015

Revisiting Agamemnon Must Die

Agamemnon Must Die tells the story that Aeschylus did in his Oresteia. This was a work that belonged very much to Athens in the fifth century B. C. It was written in lyric form as a drama that followed rules governing such works. The playwright made some innovations but not many. The actor declaimed and the chorus explained the "action." Even so, it was based on stories that belong to the cycle of songs or stories about the Trojan War. Archaeological remains from Mycenae during that era (about 1200 B. C.) strongly suggest a rich, perhaps a heroic culture.

Two artifacts belonging to that time and place and now in the possession of the Louvre are here reproduced, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The first is of a "sauce-boat" and the second is of an earring. They do not prove the existence of Agamemnon or the reality of the Trojan War, but I accept them as strongly indicative of a society that could very well have waged such a war.

Two artifacts belonging to that time and place and now in the possession of the Louvre are here reproduced, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The first is of a "sauce-boat" and the second is of an earring. They do not prove the existence of Agamemnon or the reality of the Trojan War, but I accept them as strongly indicative of a society that could very well have waged such a war.

The Homeric poems and similar stories cannot be dated with certainty any earlier than the eighth century B. C. They do suggest to me a continuity of oral tradition that informed Aeschylus. What is certain is that Aeschylus did not himself make up the stories as other playwrights also used the same materials. Euripides criticized sections of the Oresteia, and Aristophanes made fun of it. Sophocles is said to reflect, in his plays, knowledge of the Agamemnon stories.

My own telling or retelling of the story takes as given that Agamemnon was murdered upon his return from Troy and that he was avenged by his son Orestes seven years later. I felt it necessary to change some of the characters for what I considered to be sufficient cause.

My own telling or retelling of the story takes as given that Agamemnon was murdered upon his return from Troy and that he was avenged by his son Orestes seven years later. I felt it necessary to change some of the characters for what I considered to be sufficient cause.

Clytemnestra appears almost shrewish in Aeschylus' drama. This I find impossible to accept. If the legends guide us correctly, Agamemnon and his brother were taken to the house of Tyndareus, king of Sparta and father of Helen and Clytemnestra. As the older brother, Agamemnon's claim would surely have superseded that of Menelaus. Yet he chose Clytemnestra just as Odysseus declined to compete for Helen because his heart was set on Penelope. I concluded that Agamemnon was not totally clueless about his choice and saw something beyond Helen's beauty.

Similarly, Aigisthos was portrayed as weak and effeminate by Aeschylus and other retailers of these tales. It seemed inconceivable to me that Clytemnestra would have chosen such a person to allow into her chambers.

Menelaus is said by Homer to have made his way back to Greece in the eighth year after the Trojan War. I could not resist changing that to six years so that I could place him in an argument with Orestes over whether or not he should pursue the path of vengeance against Agamemnon's killers.

For more, I encourage readers of this blog to read my book.

Two artifacts belonging to that time and place and now in the possession of the Louvre are here reproduced, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The first is of a "sauce-boat" and the second is of an earring. They do not prove the existence of Agamemnon or the reality of the Trojan War, but I accept them as strongly indicative of a society that could very well have waged such a war.

Two artifacts belonging to that time and place and now in the possession of the Louvre are here reproduced, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The first is of a "sauce-boat" and the second is of an earring. They do not prove the existence of Agamemnon or the reality of the Trojan War, but I accept them as strongly indicative of a society that could very well have waged such a war. The Homeric poems and similar stories cannot be dated with certainty any earlier than the eighth century B. C. They do suggest to me a continuity of oral tradition that informed Aeschylus. What is certain is that Aeschylus did not himself make up the stories as other playwrights also used the same materials. Euripides criticized sections of the Oresteia, and Aristophanes made fun of it. Sophocles is said to reflect, in his plays, knowledge of the Agamemnon stories.

My own telling or retelling of the story takes as given that Agamemnon was murdered upon his return from Troy and that he was avenged by his son Orestes seven years later. I felt it necessary to change some of the characters for what I considered to be sufficient cause.

My own telling or retelling of the story takes as given that Agamemnon was murdered upon his return from Troy and that he was avenged by his son Orestes seven years later. I felt it necessary to change some of the characters for what I considered to be sufficient cause. Clytemnestra appears almost shrewish in Aeschylus' drama. This I find impossible to accept. If the legends guide us correctly, Agamemnon and his brother were taken to the house of Tyndareus, king of Sparta and father of Helen and Clytemnestra. As the older brother, Agamemnon's claim would surely have superseded that of Menelaus. Yet he chose Clytemnestra just as Odysseus declined to compete for Helen because his heart was set on Penelope. I concluded that Agamemnon was not totally clueless about his choice and saw something beyond Helen's beauty.

Similarly, Aigisthos was portrayed as weak and effeminate by Aeschylus and other retailers of these tales. It seemed inconceivable to me that Clytemnestra would have chosen such a person to allow into her chambers.

Menelaus is said by Homer to have made his way back to Greece in the eighth year after the Trojan War. I could not resist changing that to six years so that I could place him in an argument with Orestes over whether or not he should pursue the path of vengeance against Agamemnon's killers.

For more, I encourage readers of this blog to read my book.

Published on July 09, 2015 16:13

June 26, 2015

Target Audience for Judge Dee

Some time ago, I wondered about the existence of detective stories in Chinese literature.

Many friends told me that they were fans of the Judge Dee stories, rather like being fans of Agatha Christie, or of "the cat who" series, or of Nero Wolfe. You get the picture. I looked into this and soon discovered that there were more than two dozen Judge Dee stories from the clever pen of Robert van Gulik. I discovered among them The Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee, published in 1949 by Dover Press, that he did not write but translated from an eighteenth century edition published in vernacular Chinese.

Many friends told me that they were fans of the Judge Dee stories, rather like being fans of Agatha Christie, or of "the cat who" series, or of Nero Wolfe. You get the picture. I looked into this and soon discovered that there were more than two dozen Judge Dee stories from the clever pen of Robert van Gulik. I discovered among them The Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee, published in 1949 by Dover Press, that he did not write but translated from an eighteenth century edition published in vernacular Chinese.

I learned also that there was a historical Judge Dee, a Di Renjie, who served the Tang Empire in the seventh century. His title was not literally a judge and certainly not a judge in the same way that Rumpole of the Bailey or Judge Judy were "judges." You might be closer to the truth to compare his position to that of judges under the Napoleonic Code/Continental System who often served as prosecutor, judge and jury. His real position was that of an imperial official much like the thousand or so men with whom the English boasted they ruled India. They represented the Empire and fixed whatever was broken--fences, water supplies, domestic situations, as well as actual crimes against society or the state.

The Celebrated Cases impressed me enough to lead to the adaptation that I wrote and published as The Ingenious Judge Dee, a Play (this is described more fully in the tab for Books in this blog). Despite the eighteenth century "original" that van Gulik worked with, I chose to set the play in the seventh century. There isn't anything that is historically linked to that time in the play, but it seems a fitting tribute to the historical person. I imagined him as lean and athletic unlike the figure on the left, but his clothing might have looked similar. (This is a genuine Tang dynasty artifact, excavated in Xi-an, the capital of the Tang Empire and its image has been downloaded from Wikimedia Commons.)

The Celebrated Cases impressed me enough to lead to the adaptation that I wrote and published as The Ingenious Judge Dee, a Play (this is described more fully in the tab for Books in this blog). Despite the eighteenth century "original" that van Gulik worked with, I chose to set the play in the seventh century. There isn't anything that is historically linked to that time in the play, but it seems a fitting tribute to the historical person. I imagined him as lean and athletic unlike the figure on the left, but his clothing might have looked similar. (This is a genuine Tang dynasty artifact, excavated in Xi-an, the capital of the Tang Empire and its image has been downloaded from Wikimedia Commons.)

Then the thought intruded: Who would make up the "target market"?

Much of a writer's motivation, I believe, is internal. At least mine is. I write because something has piqued my interest or challenged my understanding or demands resolution between conflicting ideas or beliefs. This is very different from the writer who scopes out a target audience and develops a formula to appeal to it. Nevertheless, as a writer, I find it gratifying to be read even if I do not set out with an audience in mind. Reviews, even negative ones, are gratifying indications that one's work is making some sort of impression.

I imagine that the audience for this play will be those who are curious as I was about Chinese "detective" stories. No doubt, there will be fans of Judge Dee. (A video game has recently been released, I understand, but this runs outside the limits of my activities.) I hope also that those who are interested in Asian plays will look for my take on Judge Dee.

Many friends told me that they were fans of the Judge Dee stories, rather like being fans of Agatha Christie, or of "the cat who" series, or of Nero Wolfe. You get the picture. I looked into this and soon discovered that there were more than two dozen Judge Dee stories from the clever pen of Robert van Gulik. I discovered among them The Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee, published in 1949 by Dover Press, that he did not write but translated from an eighteenth century edition published in vernacular Chinese.

Many friends told me that they were fans of the Judge Dee stories, rather like being fans of Agatha Christie, or of "the cat who" series, or of Nero Wolfe. You get the picture. I looked into this and soon discovered that there were more than two dozen Judge Dee stories from the clever pen of Robert van Gulik. I discovered among them The Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee, published in 1949 by Dover Press, that he did not write but translated from an eighteenth century edition published in vernacular Chinese.I learned also that there was a historical Judge Dee, a Di Renjie, who served the Tang Empire in the seventh century. His title was not literally a judge and certainly not a judge in the same way that Rumpole of the Bailey or Judge Judy were "judges." You might be closer to the truth to compare his position to that of judges under the Napoleonic Code/Continental System who often served as prosecutor, judge and jury. His real position was that of an imperial official much like the thousand or so men with whom the English boasted they ruled India. They represented the Empire and fixed whatever was broken--fences, water supplies, domestic situations, as well as actual crimes against society or the state.

The Celebrated Cases impressed me enough to lead to the adaptation that I wrote and published as The Ingenious Judge Dee, a Play (this is described more fully in the tab for Books in this blog). Despite the eighteenth century "original" that van Gulik worked with, I chose to set the play in the seventh century. There isn't anything that is historically linked to that time in the play, but it seems a fitting tribute to the historical person. I imagined him as lean and athletic unlike the figure on the left, but his clothing might have looked similar. (This is a genuine Tang dynasty artifact, excavated in Xi-an, the capital of the Tang Empire and its image has been downloaded from Wikimedia Commons.)

The Celebrated Cases impressed me enough to lead to the adaptation that I wrote and published as The Ingenious Judge Dee, a Play (this is described more fully in the tab for Books in this blog). Despite the eighteenth century "original" that van Gulik worked with, I chose to set the play in the seventh century. There isn't anything that is historically linked to that time in the play, but it seems a fitting tribute to the historical person. I imagined him as lean and athletic unlike the figure on the left, but his clothing might have looked similar. (This is a genuine Tang dynasty artifact, excavated in Xi-an, the capital of the Tang Empire and its image has been downloaded from Wikimedia Commons.)Then the thought intruded: Who would make up the "target market"?

Much of a writer's motivation, I believe, is internal. At least mine is. I write because something has piqued my interest or challenged my understanding or demands resolution between conflicting ideas or beliefs. This is very different from the writer who scopes out a target audience and develops a formula to appeal to it. Nevertheless, as a writer, I find it gratifying to be read even if I do not set out with an audience in mind. Reviews, even negative ones, are gratifying indications that one's work is making some sort of impression.

I imagine that the audience for this play will be those who are curious as I was about Chinese "detective" stories. No doubt, there will be fans of Judge Dee. (A video game has recently been released, I understand, but this runs outside the limits of my activities.) I hope also that those who are interested in Asian plays will look for my take on Judge Dee.

Published on June 26, 2015 10:45

May 16, 2015

Muriel Spark, The Only Problem, a review

Norman Mailer dismissed Muriel Spark’s writing as belonging to what he called "dykily psychotic, crippled, creepish" women's writing. The man had his problems.

Spark is perhaps now best known for The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961) and most likely because that was made into a successful movie, starring the young Maggie Smith. Spark herself had attended James Gillespie's High School in Edinburgh (from 1923 to 1935) which was the model for the Marcia Blaine School in the novel.

The Only Problem was published in 1984 and drew my attention because its main character, Harvey, was trying as I am to understand the Book of Job. He and another character had discussed this Book since they were fellow students in university and agreed that it was the most important part of the Bible, that the problem it presents—why suffering is visited upon a man who has been pronounced righteous—is pivotal, is in fact “the only problem.”

The two men are married to sisters and matters do get complicated. Both marriages fail, though in very different ways. Harvey left his wife after she had shop-lifted two bars of chocolate and defended this action by arguing that stealing from big corporations that exploit their customers was acceptable. Her sister agreed with Harvey that stealing only makes it worse for everyone, besides which, “it’s dishonest.” The wife, however, continues in her wayward ways, contributing to a surrealistic drama involving the French police.

Meanwhile the sister leaves her husband and winds up with Harvey, though this is not as simple as it sounds. “Her being there … astonished her to the point of vertigo.” Harvey is independently wealthy and lives in France near the painting shown above of Job’s wife visiting her distressed husband. The painting is by Georges de la Tour, possibly done in 1625. Harvey visits it for inspiration from time to time. He is convinced that Job continued to suffer even after his health and wealth have been restored for “he [Job] not only argued the problem of suffering, he suffered the problem of argument. And that is incurable.” Ultimately, he [Harvey] finds “We are back to the Inscrutable. If the answers are valid, then it is the questions that are all cock-eyed.”

Meanwhile the sister leaves her husband and winds up with Harvey, though this is not as simple as it sounds. “Her being there … astonished her to the point of vertigo.” Harvey is independently wealthy and lives in France near the painting shown above of Job’s wife visiting her distressed husband. The painting is by Georges de la Tour, possibly done in 1625. Harvey visits it for inspiration from time to time. He is convinced that Job continued to suffer even after his health and wealth have been restored for “he [Job] not only argued the problem of suffering, he suffered the problem of argument. And that is incurable.” Ultimately, he [Harvey] finds “We are back to the Inscrutable. If the answers are valid, then it is the questions that are all cock-eyed.”

In an obituary that appeared in The Weekly Standard, May 1, 2006, Kelly Jane Torrance wrote: "The world has lost a singular voice with the death of Dame Muriel. Her short, sharp novels … have something of the biting wit of Evelyn Waugh and the intellectual Catholicism of Graham Greene; but in her ability to make the absurd seem everyday, and the darkest deeds deliciously droll, Spark was in a class of her own.”

The image of Georges de la Tour' painting was downloaded from Wikimedia Commons.

Spark is perhaps now best known for The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961) and most likely because that was made into a successful movie, starring the young Maggie Smith. Spark herself had attended James Gillespie's High School in Edinburgh (from 1923 to 1935) which was the model for the Marcia Blaine School in the novel.

The Only Problem was published in 1984 and drew my attention because its main character, Harvey, was trying as I am to understand the Book of Job. He and another character had discussed this Book since they were fellow students in university and agreed that it was the most important part of the Bible, that the problem it presents—why suffering is visited upon a man who has been pronounced righteous—is pivotal, is in fact “the only problem.”

The two men are married to sisters and matters do get complicated. Both marriages fail, though in very different ways. Harvey left his wife after she had shop-lifted two bars of chocolate and defended this action by arguing that stealing from big corporations that exploit their customers was acceptable. Her sister agreed with Harvey that stealing only makes it worse for everyone, besides which, “it’s dishonest.” The wife, however, continues in her wayward ways, contributing to a surrealistic drama involving the French police.

Meanwhile the sister leaves her husband and winds up with Harvey, though this is not as simple as it sounds. “Her being there … astonished her to the point of vertigo.” Harvey is independently wealthy and lives in France near the painting shown above of Job’s wife visiting her distressed husband. The painting is by Georges de la Tour, possibly done in 1625. Harvey visits it for inspiration from time to time. He is convinced that Job continued to suffer even after his health and wealth have been restored for “he [Job] not only argued the problem of suffering, he suffered the problem of argument. And that is incurable.” Ultimately, he [Harvey] finds “We are back to the Inscrutable. If the answers are valid, then it is the questions that are all cock-eyed.”

Meanwhile the sister leaves her husband and winds up with Harvey, though this is not as simple as it sounds. “Her being there … astonished her to the point of vertigo.” Harvey is independently wealthy and lives in France near the painting shown above of Job’s wife visiting her distressed husband. The painting is by Georges de la Tour, possibly done in 1625. Harvey visits it for inspiration from time to time. He is convinced that Job continued to suffer even after his health and wealth have been restored for “he [Job] not only argued the problem of suffering, he suffered the problem of argument. And that is incurable.” Ultimately, he [Harvey] finds “We are back to the Inscrutable. If the answers are valid, then it is the questions that are all cock-eyed.” In an obituary that appeared in The Weekly Standard, May 1, 2006, Kelly Jane Torrance wrote: "The world has lost a singular voice with the death of Dame Muriel. Her short, sharp novels … have something of the biting wit of Evelyn Waugh and the intellectual Catholicism of Graham Greene; but in her ability to make the absurd seem everyday, and the darkest deeds deliciously droll, Spark was in a class of her own.”

The image of Georges de la Tour' painting was downloaded from Wikimedia Commons.

Published on May 16, 2015 11:29