Chris Stedman's Blog, page 17

January 30, 2013

How much of a Humanist are you?

Apropos of the recent discussion between James Croft, Leah Libresco and me over the specifics of Humanism, I’ve stumbled upon the British Humanist Associations “Are you a Humanist?” quiz. Though I ended up tentatively supporting Humanism as a movement while rejecting it as a philosophical position, I’m apparently 90% a Humanist. I felt that the responses were somewhat limited (understandable, considering it’s a multiple choice quiz for a broad lay audience), so I thought it might be fun to expand on my answers in more depth below.

Apropos of the recent discussion between James Croft, Leah Libresco and me over the specifics of Humanism, I’ve stumbled upon the British Humanist Associations “Are you a Humanist?” quiz. Though I ended up tentatively supporting Humanism as a movement while rejecting it as a philosophical position, I’m apparently 90% a Humanist. I felt that the responses were somewhat limited (understandable, considering it’s a multiple choice quiz for a broad lay audience), so I thought it might be fun to expand on my answers in more depth below.

Take the quiz yourself and let me know if you’d have preferred any other choices, or just think my responses are way off.

1. Does God Exist?

The negative responses to this question were either “I don’t know” or “There is no evidence, so I assume God doesn’t exist.” I wasn’t particularly satisfied by either choice. I’m not an agnostic, I’m an atheist (and I reject the useless muddling of the terms by pretending they overlap.) So I very much believe that God doesn’t exist, and I don’t consider that an assumption based on a lack of evidence. I actually think the evidence is rather suggestive that God doesn’t exist, and I’d wager many other atheists and Humanists feel the same way. So I feel uncomfortable categorizing that as an assumption. Nonetheless, that’s the option I chose.

2. When I die…

That’ll be the end of me. There’s a cute option that involves living on through children and memories but that’s not really me living on (but instead my works and memories of me…). Woody Allen put it nicely, “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work… I want to achieve it through not dying.”

3. How did the Universe begin?

I also have a few quibbles here, as well, because I’m skeptical that science can ever answer this question. I also don’t think the scientific explanations being the best explanation available is necessarily incompatible with God creating the universe. That’s because the two are at different levels of explanation, so what’s best is really a matter of preference. But again, minor quibble. I chose science.

4. The theory that life on Earth evolved gradually over billions of years is…

True. Next.

5. When I look at a beautiful view I think that…

“this is a beautiful view.” But the only choices were “protect it for the future” or “think that this is what life is all about.” This was a toss-up for me because I don’t ever really think either. Life is about more than just looking at beautiful views, and I’m not thinking about future generations on a typical day. I figure that “this is what life is all about” is close enough, though.

6. I can tell right from wrong by…

I’m pretty tiffed that the only decent answer is a consequentialist one. The other options are “my parents,” “my pastor,” or “I do what I want.” (Can the responses be at least close to one another on Kohlberg’s stages of moral development, please?) My problem is that the consequences of actions themselves don’t really tell you what you should do. A hedonic egoist, a consequentialist, and someone with a chaotic neutral alignment will all come to very different conclusions based on the same information about consequences. So this answer doesn’t really give anything substantively moral. I would have preferred an answer like “by weighing everyone’s preferences equally and acting accordingly,” even as vague as that is. Personally, I’ve got a shaky working model like “choosing the action that would make me most like the person I want to be,” and I’ll just bite the bullet that there’s some inherent subjectivity to that. It gets close to what I think is a more solid position, though.

7. It’s best to be honest because…

The only good answers here are motivated by self-interest, which I don’t really appreciate. I can choose between “people respect you more if you’re honest” and “I’m happier being honest.” I picked the latter, but would have preferred an answer with a more universal justification.

8. Other people matter because…

We can choose between “people have feelings” and “we will be happier if we treat each other well.” I’m not particularly happy with either answer, but I think the first one has more moral weight. And to anyone who chooses the second one: if the empirical facts swung the other way, and it turned out that being cruel to other people or a subset of people actually increased aggregate happiness, would you then be willing to say that we ought subjugate those people? That’s not a comfortable place to be in.

9. Animals should be treated…

With respect, because they can suffer, too. I think this is the only coherent answer given, and I don’t think it makes sense for a Humanist or atheist to not care about animal welfare. If suffering matters, then there’s no inherent reason that human suffering is special. I think I might write at length about this later, but I can’t think of any good reason an atheist or Humanist shouldn’t be a vegetarian or vegan. Just something to mull over.

10. The most important thing in life is…

We have either environmentalism or general welfare and happiness of humanity. I think the latter is more important, but it ignores animal welfare (which matters) and it depends on some strong and as-of-yet unjustified ethical principles. I’m happy to choose that, though.

—

Anyway, those are my answers. I think as a whole it was an interesting quiz which did a good job of highlighting some values I think Humanists can somewhat uncontroversially organize around (even if I think it’s philosophically shaky). At the very least, I have a better idea of some of the things Humanists are committed to, even if I might not agree with the justification.

h/t to Paul Fidalgo at T

he Morning Heresy

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

January 25, 2013

A Pro-Choice Muslim Celebrates Roe v. Wade

Tuesday was the fortieth anniversary of one of the most controversial and recognizable Supreme Court decisions, Roe v. Wade. Though the Court’s interpretation and justification for the decision was revisited and updated over the decades that followed the 1973 ruling, the original judgment focused on the right of physicians, not women, to privacy, rather than bodily autonomy or equality. Jeffrey Toobin of The New Yorker wrote in their most recent issue about Roe v. Wade’s legal transformation, noting that the word “physician” appeared in the original ruling 48 times, and “women” only 44. Toobin writes:

On the fortieth anniversary of Roe v. Wade, it is worthwhile to celebrate a landmark of what is, in the truest sense, women’s liberation. But it’s important to remember, too, that it wasn’t the Supreme Court Justices alone who made sure that Roe survived. The judicial texts have evolved from odes to doctors to paeans to liberty and to defenses of equality. But it is the voters and the President they elect who will decide whether abortion rights survive for the next four decades.

I think it’s important to focus on the cultural attitudes surrounding abortion, because they’ll inevitable be what determines Roe’s future. This is one of the reasons I’ve been arguing for a while about the importance of liberal religious believers, particularly on women’s issues and LGBTQ rights. Though I think reports of religion’s demise are greatly exaggerated, the country’s shift to the left on social issues should give us reason to be optimistic about the future of religion in America. Altaf Saadi, a fourth-year student at Harvard Medical School, demonstrates this perfectly.

Saadi writes in the Huffington Post’s Religion section about her story as a pro-choice Muslim, challenging assumptions about but also within Islam. The entire post deserves a read, but I found the end to be particularly striking:

This year, on the 40th anniversary of the monumental Roe v. Wade decision, and after a crescendo of anti-abortion opposition witnessed in the past year (in 2012 alone, 43 abortion restrictions were enacted in 19 states), I celebrate Roe v. Wade proudly as a Muslim woman. I deeply hope that more Muslim women and men will do the same with me, refusing to accept blanket, unfounded statements about religious or Islamic opposition to abortion.

I also hope that the celebration of this day will translate to advocacy around this issue in faith communities, where criminalizing obtaining or providing an abortion can be seen as a violation of religious liberty, in addition to violations of the right to privacy and bodily autonomy. Just as there are religious leaders in our communities that understand the complexity and nuances involved in such a decision, we must understand too. It is as the Eastern Orthodox author Frederica Mathews-Green aptly put it: “No woman wants an abortion as she wants an ice cream cone or a Porsche. She wants an abortion as an animal caught in a trap wants to gnaw off its own leg.”

Obama has been doing a particularly good job of framing liberal policies in terms that religious believers can relate to—fighting climate changed is adhering to God’s command that we be stewards of our planet, gay rights is a natural conclusion of our equal creation by God, and so on. I think this provides an important opportunity for religious believers who don’t want to feel like they must choose between their religion and progressive politics. Religious doesn’t need to mean social conservative, and we do everyone a disservice when we act like it does.

Religion is not anti-gay rights. Religion is not anti-evolution or anti-woman or anti-abortion. Religion isn’t a monolithic entity that’s anti or pro anything—it’s a complex social structure realized in vastly different and deeply personal ways across many different people and cultures.

I admire the bravery of Altaf Saadi, who can challenge stereotypes and act as a proud example of how an Islamic woman can fight for a woman’s right to equality and bodily autonomy without sacrificing her religious convictions. I appreciate Leah Libresco, a recent convert to Catholicism, for coming out in support of civil gay-marriages. And I’m grateful to other young, religious Americans who are challenging our ideas of what it means to be religious. I’m eager to see how our generation continues to navigate these social issues in the coming years.

P.S. After this post went up, Chris showed me some really cool numbers that the Pew Research Center put out recently about religious support for Roe v. Wade. CNN’s Religion Blog writes:

Slightly more than half (54%) of white evangelicals, according to the Pew Research Center study, favor completely overturning the 1973 Supreme Court decision that affirmed a woman’s right to have an abortion. No other religious group, including white mainline Protestants, black Protestants and white Catholics, agreed with completely overturning the ruling.

In fact, substantial majorities of white Protestants (76%), black Protestants (65%) and white Catholics (63%) say the ruling should not be over turned, the survey found.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

January 23, 2013

The Advocate: ‘Saved by Grace’

This post originally appeared on faitheistbook.com.

The Advocate magazine, which previously listed Faitheist at the front of their list of 10 books on the intersection of religion and LGBT life, has published an essay about my years in the closet, portions of which were adapted from Faitheist. This was a difficult one to write and share—thanks so much to everyone who has shown me love and support over the years.

Check out the beginning of the piece below, and click here to read it in full.

This piece was adapted from Faitheist: How an Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious (Beacon Press, 2012).

Sometimes a person can descend so low into his or her own misery that returning to the world is impossible without the help of another person. Sinking deeper and deeper into self-loathing as an adolescent, I thought that person would be Jesus.

As it turned out, my savior did come from above—she slept just upstairs.

I was a gregarious child, but I lost my self-confidence around the age of 11. Shortly after joining a fundamentalist, nondenominational Christian church at the encouragement of friends, I realized I was gay. The evangelical community I converted into made it clear that embracing my same-sex attractions was not an option, but they presented a way out: I could pray the gay away.

I launched a private campaign to cure myself of my sexual orientation. I prayed and fasted obsessively, spending my middle school lunch periods in an empty classroom with an empty stomach, a teen study Bible plastered with bumper stickers, a Discman to play Christian worship music, and a journal for reflecting on my efforts.

This self-imposed isolation went on for years, but my attractions remained. Growing more and more frustrated that I was perpetually hiding this struggle and not seeing any hope of change, I became despondent. I kept praying and fasting, waiting to wake up straight, but I was at the end of my rope.

Click here to continue reading.

P.S. If you or someone you know is struggling with this issue, please know that you are loved—and, if needed, don’t hesitate to reach out to my friends at The Trevor Project. xx

January 22, 2013

A Tale of Two New Humanist Service Initiatives

My new piece about Humanism and service for HuffPost Religion is coauthored with Conor Robinson, Director of Pathfinders Project at the Foundation Beyond Belief. Check out the piece for more information on the recent partnership between Pathfinders Project and Values in Action at the Humanist Community at Harvard.

A little more than a year ago, the two of us walked along a beautiful California beach. It was a gorgeous afternoon, and all around us people laughed and frolicked, enjoying the sun and surf. We, too, were enjoying the day, but we weren’t there just to take in the beautiful views or some extra UV rays — we were there with a group distributing resources to the homeless youth who spent their days on the beach, unable to find assistance elsewhere. We shared food and clothing, offered medical assistance and listened to their stories.

We were there because we care about those kids. We were there because we care about service work. And we were there because we are atheists and Humanists who care deeply about making the world a better place.

We are two incredibly different individuals living on opposite ends of the country, but our work in the Humanist and atheist movements, as well as our commitment to service, has brought us together. After three years of unofficial collaboration, we are excited to announce a partnership between our projects –Pathfinders Project at Foundation Beyond Belief, and the Values In Action (VIA) initiative at the Humanist Community at Harvard (HCH).

Click here to continue reading.

January 21, 2013

Video: ‘Faitheist’ and Martin Luther King, Jr. Day

Thank you so much to Montana State University’s newspaper, Exponent, for producing this lovely video about my visit for their annual Martin Luther King, Jr. lecture. What a great way to remember what was a truly special day for me.

This post originally appeared on faitheistbook.com.

January 20, 2013

The Internet probably hasn’t made people less religious

If there was a single cultural currency of the atheist movement, it would undeniably be the Internet language of memes, macros, and Facebook screencaps. Though atheists still make up only around 3-8% of the population, depending on who asks and how, they’re a dominating presence in online discourse. On websites like Reddit, where more than 80% of users are men and under the age of 35, atheism seems to be a default cultural assumption. The atheism subforum is in fact so popular—it has more than a million and a half subscribers—that it’s one of the few that new accounts are automatically subscribed to upon registration. From Facebook to YouTube, it seems like atheism has a serious presence online.

It’s not really much of a surprise, then, that atheists really love the Internet. When commenting on America’s shift away from religion, it seems that atheists are always quick to add to the sociologist’s explanation with a comment like “[a]nd the Internet. Don’t forget the Internet.” And this week, Valerie Tarico took this trend to the extreme with her Salon article, “Religion May Not Survive the Internet.”

Let me continue in my role as stats-nerd and general naysayer to suggest the following: Religion did and will survive the Internet and, at least when we’re talking about shifts in demographics, we probably should forget the Internet.

So here’s what we know:

Atheism hasn’t risen much at all over the last decade.

For all the fuss made over the “rise of the Nones,” they’re remarkably religious. About 70% of the religiously unaffiliated say they still believe in a God or a universal spirit. The rest of the population isn’t much different. Though it’s true that fewer Americans are saying they believe in God—according to Gallup, 86% of respondents said they believed in God in 1999, whereas 80% said they did in 2010—more Americans now say they believe in a universal spirit—the number was only 8% in 1999, and it’s risen to 12% in 2010.

The number of Americans in the 2000′s who believed in neither God nor a universal spirit hardly changed at all, rising only from 5% to 6%. It’d be weird if a decade characterized by greater access to information only had the effect of pushing people away from God and into belief in a universal spirit. If the Internet has done anything, then, it seems like it’s only connected nonbelievers into online communities, which has likely made them more comfortable identifying as atheists. That’s not to say the Internet hasn’t been important, since it likely allows many geographically isolated nonbelievers to have a community, but it probably hasn’t changed many people’s minds.

Migration from religion has only really affected Protestants.

I discussed these data briefly when I gave my advice to Evangelical Christians. If, as sociologists like Robert Putnam and authors like David Niose argue, what’s driving the exodus from organized religion is a cultural shift to the left on social issues coupled with our current mix of religion and conservative politics, then you’d expect to see conservative churches losing the most members. A look at the polling data shows exactly that. Over the last five years, according to Pew, the unaffiliated have risen by about 5%, and Christianity has dipped about 5%. But the numbers seem to come exclusively from the largely conservative Protestants, whereas the generally liberal Catholics have hardly been affected at all. If it’s access to information that’s driving this trend, then it’d be weird if Protestants were the only believers using the Internet.

Widespread access to information isn’t that new.

From how you hear many atheists talk about the Internet, you’d think that no one had access to any information that challenged religious beliefs before Al Gore worked his magic. But “the Great Agnostic” Robert Ingersol was one of the most popular and sought after speakers in the mid-to-late 19th Century, and, thanks to Benjamin Franklin and the public library system, any curious doubters of the 20th Century could easily read Hume’s “Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion” or anything, really, by Bertrand Russell. Information may be easier to access now than ever before, but the access has always been there—so long as you were literate and could make it to a library. Religion survived in those days, and it’s surviving now.

We only really look for information that confirms what we already believe.

Over the last few decades, psychological research has shown again and again how bad we are at changing our minds. When given the opportunity, we seek information that justifies what we already believe and ignore or try to discredit information that doesn’t. The research is broad, but Chris Mooney summarizes many of the findings nicely in his 2011 article “The Science of Why We Don’t Believe Science.” So even though the Internet might be providing a breadth of new information, it’s not immediately clear how persuasive it’s been. And since the amount of Americans who believe the Earth is less than 10,000 years old has remained basically constant over the last twenty years, I’m not too optimistic. It seems that whether it’s today or a hundred years ago, doubters are going to seek out information to confirm their doubts and believers are going to largely ignore conflicting information.

—

Given these data, I think it’s really unlikely that the Internet has played any substantive role in bringing Americans out of religion. Everyone has a self-serving bias, and atheists aren’t immune. Atheist writers seem really optimistic—they say we have the truth on our side, information is widely accessible, and we’re growing in numbers. But it seems like these first two things don’t really matter that much, and our growth seems to be more in organization and political influence, rather than genuine conversion.

To me, this supports a focus on values rather than beliefs, and about this I’m optimistic—if America is becoming more socially liberal but remains God-fearing, then that’s fine with me. So long as we have a cultural momentum geared toward gay rights, secular government, and social justice, the politically liberal religiously unaffiliated can help to push this progress forward. And there the Internet might help, no matter what anyone believes about God.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

January 18, 2013

In the Bozeman Daily Chronicle

This post originally appeared on faitheistbook.com.

Thank you so much to everyone who came to my events last night and this morning at Montana State University! (And to all the folks who came to my event the night before at The Mark Twain House & Museum – here’s a post from the event’s moderator about it.) I had such a wonderful time meeting and speaking with you all. Below is a part of an article from the Bozeman Daily Chronicle about last night’s MSU event; click here to read it in full and see pictures from the event.

Atheists and people of religious faith can work together to build a better world despite their differences, activist and author Chris Stedman told a Bozeman audience Thursday at a Martin Luther King lecture.

Stedman, the assistant humanist chaplain at Harvard University, spoke to more than 100 students and community members at Montana State University for the university’s annual King lecture.

He recently wrote a book, “Faitheist: How An Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religions.” It describes his personal journey in and out of faith, and how he came to work with a Christian pastor to fight hunger. In the Boston area, he said, they’ve provided meals for 70,000 hungry children.

“What would happen if atheists and Christians could see themselves as necessary partners in making the world a better place?” Stedman asked. “What might we accomplish together?”

King, the black civil rights leader, was known for reaching across religious lines to work with Jews and Christian pastors of different denominations, Stedman said. But few know that one of King’s closest advisors, Phillip Randolph, a black labor leader and organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, where King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, was also an atheist.

Atheists are one of the most distrusted groups in America and live with a great stigma, Stedman said. People assume they’re angry and want to tear down religion. Polls find that Americans are less likely to vote for atheists than for Jews, Mormons or Muslims, and atheists are the ones parents least want their children to marry.

Yet the ranks of non-believers are growing, especially among young people, he said. One in five Americans is not religiously affiliated.

January 15, 2013

Michael Shermer and bridging the Is/Ought Gap

In a recent blog post and Edge submission, skeptic Michael Shermer argues that the famous “is/ought” fallacy is itself a fallacy. He writes:

In a recent blog post and Edge submission, skeptic Michael Shermer argues that the famous “is/ought” fallacy is itself a fallacy. He writes:

Ever since the philosophers David Hume and G. E. Moore identified the “Is-Ought problem” between descriptive statements (the way something “is”) and prescriptive statements (the way something “ought to be”), most scientists have conceded the high ground of determining human values, morals, and ethics to philosophers, agreeing that science can only describe the way things are but never tell us how they ought to be. This is a mistake.

While Shermer’s argument is somewhat straightforward, it’s actually hard to logically parse it. It also isn’t a particularly new idea, because it seems to closely echo statements made by Sam Harris in his TED talk and book, The Moral Landscape. Regardless, Shermer starts with the following:

We begin with the individual organism as the primary unit of biology and society because the organism is the principal target of natural selection and social evolution. Thus, the survival and flourishing of the individual organism—people in this context—is the basis of establishing values and morals, and so determining the conditions by which humans best flourish ought to be the goal of a science of morality.

Shermer never quite makes it clear, though, why we’re starting where we are or how science grants any moral significance to our status as the “principle target of natural selection and social evolution.” It’s also not quite clear why science entails that “determining the conditions by which humans best flourish ought to be the goal of a science of morality.” In fact, it’s not clear where any of these conclusions are coming from at all, let alone what part science is playing in them. If anything, these conclusions seem to be assumptions that Shermer is smuggling in. These assumptions will show up as a problem later, but Shermer goes on to list findings in biology, psychology, and the social sciences to demonstrate science’s ability to determine values with an example:

Question: What is the best form of governance for large modern human societies? Answer: a liberal democracy with a market economy. Evidence: liberal democracies with market economies are more prosperous, more peaceful, and fairer than any other form of governance tried.

That’s it. Therefore science says we should accept liberal democracy and the is/ought gap has been bested. In your face, Hume.

But in all seriousness, I hope that strikes you as incomplete. In fact it perfectly demonstrates the is/ought gap and why it’s not a fallacy at all. Let me restate Shermer’s argument this way for clarity:

Premise: A liberal democracy is more prosperous, more peaceful, and fairer than any other form of governance tried.

Conclusion: We ought to institute a liberal democracy.

That seems a little incomplete, doesn’t it? That’s because it’s missing a step:

Premise 1: A liberal democracy is more prosperous, more peaceful, and fairer than any other form of governance tried.

Premise 2: We ought to institute the most prosperous, peaceful, and fair form of governance we’ve tried.

Conclusion: We ought to institute a liberal democracy.

Shermer’s argument is missing an “ought” statement, and that’s exactly what the is/ought gap is—an “ought” is needed somewhere in the premises in order to derive a conclusion about an “ought.” That’s exactly what Shermer needed to show that science can do, and it’s exactly what he glossed over. If your argument hinges on some kind of assumption about what you ought to do—what kinds of governments we ought to institute (fair and peaceful ones) or what kinds of things we ought to promote (flourishing)—then you’ve really said nothing interesting at all about science or morality.

No one says that science can’t provide us with information about the world that might enter into the “is” statements of our moral calculus. But in doing that we don’t bridge the “is/ought” gap. Instead, all Shermer has done is assume his way across it while pretending that science did all the work.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

January 11, 2013

Changing My Mind

With the new year, I was thinking about how much my views on a whole bunch of things have changed just in the last few months, and it occurred to me: I’ve probably said a bunch of wrong stuff out loud and even louder on the internet in my time blogging (like bloggers are prone to do).

So rather than just shrug and hope people who’ve read stuff of mine in the past keep up with me in the here/now and are familiar with my personal intellectual evolution (you love me that much right right), I just wanted to quickly compile and critique few things I’ve found from my past that I really just don’t agree with anymore. If only to help me sleep at night.

So here we go, following the Ghost of Wrongness Past:

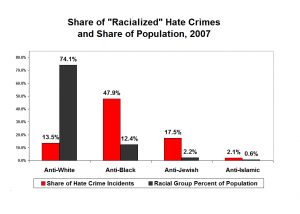

“Atheism may, in fact, be the most stigmatized minority group in America” – Peers, Parents, and Popularity || The New Humanism

“Atheism may, in fact, be the most stigmatized minority group in America” – Peers, Parents, and Popularity || The New Humanism

In which I buy into a prevailing misconception. Barring the already ambiguous (and not clarified) use of the word “stigmatized”—in what way? Civil rights? Recipients of violence? Ability to hold office?—this notion that to identify as an atheist is equally and universally as socially repulsive now as it was decades or centuries ago just needs to be excised, in the interest of nuance and honesty. I’m white and cisgender male-identified, I’m fairly financially secure, and I live in Boston. There are places where I’m underprivileged, but particularly in my community, my atheism is in no way “stigmatized”. Of course: there are other classes, other geographies, other communities in America where it is abhorred (naturally, I cited Jessica Ahlquist’s plight in the article, and even in my North Carolina hometown I felt compelled to hide it most of the time)—but, and I’ll gleefully play the Oppression Olympics here, this is in no way even comparable to (like one commenter on the article notes) that of those in the trans community, who are routinely disserviced by our repugnantly binary-normalized society, who are the subjects of extraordinary violence, who have no choice but to do everything they can to hide who they are in most communities in America. I mentioned earlier that my class plays heavily into this characterization—sure, if I was in a low income, urbanized neighborhood, where maybe the local church is central to community organization, being an open and out atheist could easily contribute to the existing oppressive forces from the government and from the surrounding poverty-borne tension. But that’s not because “atheism may be the most stigmatized minority group in America”, it’s because oppression is naturally going to magnify exponentially as you start adding minority characteristics to your identity. Vlad wrote a great piece a while back criticizing the common trope of how “distrusted” atheists are. I don’t think we should discredit the underprivilege of many Western atheists (and certainly not of atheists in less developed countries, just remember no further than Alexander Aan in Indonesia), but that we shouldn’t let our dedication to our own plight blind us from the oppression of others. That’s how a progressive can inhibit progress.

“The use of Islamic promises of paradise, in addition to anti-Israeli propaganda, to drive young Palestinian middle-class to suicide bombing is, to me, just as much an affront to human dignity as the Apartheid-esque segregation and misemployment of the citizens of the West Bank by Israeli officials.” – Israel and the Arab World, Part 3 || NonProphet Status

“The use of Islamic promises of paradise, in addition to anti-Israeli propaganda, to drive young Palestinian middle-class to suicide bombing is, to me, just as much an affront to human dignity as the Apartheid-esque segregation and misemployment of the citizens of the West Bank by Israeli officials.” – Israel and the Arab World, Part 3 || NonProphet Status

This isn’t as strong a statement as I think it comes off, I think my intention was more to be nuanced in my assessment of the issue, I made the tiresome mistake that CNN makes all the time: of thinking “balanced and objective” means suggesting both sides are equals. It is true that the charter of Hamas has a number of propagandic, prejudiced statements, suggesting for instance that Jews “control the mass media”. It’s also true that they’re guilty of training schoolchildren in bomb tactics, under the guise of education. But I think, now, that this is all very beside the more relevant point that this repugnantly extremist behavior is a natural consequence of the tremendous divide, in wealth and power, between Israel and the Palestinian territories. And frankly, looking at the issue from any other dimension, you’d be hard pressed to find a way in which Israel’s transgressions don’t vastly outdo those of the Arabs: the IDF’s arsenal includes the “most powerful military technology in the region”; Israel’s lobbying power in the most powerful government in the world gives it tremendous propogandic influence; and even sources sympathetic to Israel cite the number of Palestinian casualties as four times greater than those in Israel. Racism is not justified, but when it’s coming from two sides, particularly sides of a class divide as stark as that in Jerusalem, we are obligated to side with those oppressed, albeit giving honesty to their own shortcomings and horrific practices. But never should we say that they are of the same “affront to human dignity” when one towers above the other.

“I don’t think he ever engaged in what I would call, ‘bullying’.” – Hitched || NonProphet Status

“I don’t think he ever engaged in what I would call, ‘bullying’.” – Hitched || NonProphet Status

Maybe my definition of “bullying” has changed, but more than likely, my changed interpretation of Hitchens has led me to question whether he deserves this much credit. He’s certainly still one of primary influence to my interest in journalism, activism, and polemics–but, like I mentioned in the last graph, I don’t want to present him as unflawed, or apologize for some of his truly problematic views and statements on wars overseas, women, and, naturally, religion. I don’t any longer think there’s a valid distinction to be made between desecrating and dehumanizing a certain religion as a monolith and doing so to its individual members–any more than there is in the tired “love the sinner, hate the sin” nonsense. So I’m truly uncomfortable and offended that Hitch was known to offer up stuff like “[cluster bombs] are pretty good because those steel pellets will go straight through somebody and out the other side and through somebody else. And if they’re bearing a Koran over their heart, it’ll go straight through that, too.” Or, when he outright tried to discredit the term “islamophobia”, calling it a “stupid neologism” and denying its interconnection with racism. That was, on it’s face, bullying, of an oppressed class no less. His notorious “Why Women Aren’t Funny” is laughably broad-stroking and based in a entirely anachronistic, 1940′s-Mad -Men causal sexism. While I think his support for the Iraq War came from a place of compassion for the Arabs, and especially Kurds, massacred under Sadam Hussein, I also think “Kill Sadam, save the world” is an overtly militaristic and unstrategic policy prescription that ultimately did far more harm to both sides than good. But I’ll still defend Hitch’s historic activism, particularly in response to Vietnam and in support of civil rights, his passion for journalistic integrity, and his eloquence and verbosity. And I definitely recommend reading (or checking the audiobook) his memoir Hitch-22, which helps give a much more nuanced picture of his life and times in his own words.

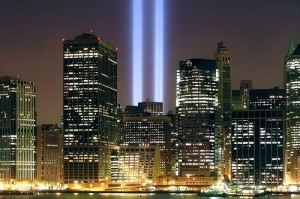

“The actions that transcribed on September 11th, 2001 were undoubtedly religious motivated.” – 9/11 || NonProphet Status

“The actions that transcribed on September 11th, 2001 were undoubtedly religious motivated.” – 9/11 || NonProphet Status

In context, I did proceed after this to explain that “religious motivations” aren’t formed “in a vacuum”, and how silly it would be to draw a perfect causal relationship between any form of Islam and immense terroristic violence. But if I were writing this same article today (or last September), I don’t think I’d mention the religious aspect at all. That definitely seems weird—9/11 inspired many of the big atheist authors to get writing on the topic of religion, thus springing atheism into the mainstream. But in honesty, has much good come from us, behind our privileged American computers, pointing out the passages in the Quran that may have inspired mass violence? Doing so, and trying to paint Islam as “barbaric” or inherently violent, has certainly contributed to a culture of Islamophobic oppression, and linked not only American Muslims to a horrific crime that had no part whatsoever in, but really anyone who at all fits the “Muslim terrorist” stereotype–Steve just recently published a compelling piece on this very point. So while religion was a part of the myriad motivations for the 9/11 attacks, it seems like there are far better ways for us to talk about the issue–in terms of poverty, of authoritarianism, perhaps very specifically of dogmatism–than simply “religion caused this”. “Imagining a world with no religion” does not necessarily lead to the twin towers remaining standing. But imagining a world where we don’t broad-stroke a link between particular identities and mass violence certainly seems to lead to a more harmonious society.

Anyway, these are just a few places where I wanted to reflect on how my way of thinking’s changed. Honesty and openness are an important jigsaws in critical thinking, and if we’re to best confront the problems of our world, we have to be willing to realign ourselves as we learn more about the world. We have to fight the tribalism that arises from a comfortable perception of superiority. And we have to be brutally self-reflective.

Can’t wait to see how I’m thinking differently next year.

Walker Bristol woke up this morning and realized, to his dismay, that he is the President of the Tufts Freethought Society and the Director of Communications for Foundation Beyond Belief . This is especially peculiar considering he grew up as a high school wrestler-pianist in North Carolina and intended to become Luke Skywalker for an undisclosed period of his life, eventually settling for a Star Wars tattoo. The Tufts Political Science and Religion departments suffer his enrollment. He writes about social activism and art in the Tufts Daily . His diet consists of hummus. He tweets nonsense on all these fronts @WalkerBristol .

A few links: James Clarifies, Mindreading Conference, and Susan Jacoby

Leah Libresco and I have been flanking James Croft and other Humanists to clarify the often vague discussion surrounding Humanism and its values. Though occasionally a bit frustrating, my conversation with James and a few others has really helped me get a better handle on the topic.

Leah Libresco and I have been flanking James Croft and other Humanists to clarify the often vague discussion surrounding Humanism and its values. Though occasionally a bit frustrating, my conversation with James and a few others has really helped me get a better handle on the topic.

James wrote a response yesterday, and he helpfully clarifies that Humanism is better understood as a tradition, rather than a single philosophy. This helps, but I can’t shake my concerns about its vagueness, and I don’t quite understand why Humanism is a helpful label over and above social or political convenience (and I’m happy to leave it at that).

I pressed James about the importance of Humanism, and he certainly isn’t modest about it (he went so far as to call it the most generative tradition in philosophy; I was skeptical). But he argued that without Humanism, you couldn’t understand much of philosophy, like Kant (incidentally, these conversations have also persuaded me to write a post explaining my Kant-appreciation since it seems to come up so much. I promise to share soon). But it’s hard for me not to read this claim as saying “Humanism, as a broad tradition, includes important philosophers that you should know about.” It seems what’s doing the legwork of Humanism is really just the important philosophers that fall under this rather-broad label.

But if we’re going to call the tradition of Humanism important and generative, what we need to be showing is that the common thread that connects all the independent philosophy is having some impact, rather than just the independent philosophy. We can’t just say “Mills is important, so Humanism is important” or “we need to understand Mills to understand [whatever], so we need Humanism to understand [whatever].” Instead, it should be something like “[Whatever thing] connects the work of Mills to Sartre/Singer/Russell/whoever else, and [that thing] is important” or “[That thing] is necessary to understand [whatever].” In the former case, Humanism is just an irrelevant post-hoc label; in the latter case it’s doing some work.

—

I’m going to be at this really interesting conference in Chapel Hill for the next two days. From the site:

This conference brings together a number of researchers who are currently working on topics such as: the role of mindreading in understanding (both linguistic and nonlinguistic), varieties and impairments of intersubjective engagement, and the nature of emotions and their role in interpersonal communication as well as in the genesis of moral discourse (both in ontogeny and in phylogeny). These topics lie at the intersection of several fields: philosophy, psychology, linguistics, and neuroscience. Their discussion could benefit from productive interdisciplinary exchange – to which we hope to contribute with this conference.

I’m pretty excited, so I’ll probably be tweeting a bit while it’s going on and might write up any particularly cool talks or discussions after. If any interested readers want to let me know if any specific talks seem interesting, I’ll do what I can to report back.

—

So I actually wasn’t a huge fan of Susan Jacoby’s essay published in The New York Times on Sunday, “The Blessing of Atheism.” Personally, I’ve never found comfort during tragedy in knowing that I don’t need to worry about free will or the problem of evil. Usually, I’m busy worrying about the fact that I live in a purposeless universe, can be the random victim of tragedy at any time myself, and will experience exactly nothing when I die. But to each their own.

Alan Jacobs has a more at length critique worth reading (h/t to Paul Fidalgo at The Morning Heresy). He writes:

What does atheism have to offer when “a loved one [is] losing his mind to Alzheimer’s,” and so on? I don’t see how atheism qua atheism (as the philosophers say) has anything at all to offer, though particular atheists, just like particular religious believers, can certainly offer a lot in the way of care, compassion, physical and emotional assistance.

—

Did I mention that I wrote a thing? Guys I wrote a thing maybe go read it and validate me please.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.