Chris Stedman's Blog, page 16

February 12, 2013

Be My Valentine, Carl Sagan

In anticipation of Valentine’s Day, I decided to repost a piece I wrote last year as a part of the HCH blogathon, in which I confess my love for Carl Sagan:

+++++

This post is a part of the Humanist Community at Harvard’s 2012 Blogathon, a 12 hour blogging marathon by Chris Stedman and Chelsea Link to support HCH’s end-of-the-year fundraiser. Chelsea and Chris are both publishing one new post per hour, for twelve hours straight, and none of the posts have been written or drafted in advance. For more blogathon posts, click here. If you enjoyed this post or any of the others, please consider consider chipping in to support our work.

Dear Carl,

I’ve already complained about the nature of rapidfire blogathon writing today, so I won’t repeat myself. As with, well, every piece I’ve written so far today, I would prefer to write this with more time and consideration. But like many love letters, this stream of consciousness is being composed on an impulsive whim. (And, in defense of blogathons, I suppose this is one thing they’re good for — pushing the writer to express a set of ideas in a concise and timely manner.)

I don’t know where to begin thanking you, Dr. Carl Sagan. Your writing has been a source of great comfort at times when I most needed to be comforted. I found solace in Cosmos, such as when you wrote: “Every one of us is, in the cosmic perspective, precious. If a human disagrees with you, let him live. In a hundred billion galaxies, you will not find another.” It reminded me of how important it is to remember that every human being deserves to be treated with dignity — including myself.

Your writing constantly reminds me of our interdependence, and of how important it is that all of us work together to improve our world — because none of us can do it alone. I was moved to tears the first time I read the Pale Blue Dot. I still am. I’m just going to leave this excerpt here without further comment, because it speaks for itself, and because I think that the world would be a better place if everyone remembered this message more often:

Alongside that — and so many other writings you published — is perhaps my favorite thing you ever said, which is now tattooed on my arm, interwoven among other tattoos that compose my full sleeve (including several satellite dishes). It is a phrase that you wrote in Contact: “For small creatures such as we the vastness is bearable only through love.” This quote opens my own book, Faitheist, alongside a quote from Rumi: “Your task is not to seek for love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it.” Your work has helped me to uncover so many barriers of my own.

I will never have the opportunity to meet you, and for that I feel regret — for I would like to thank you for the ways in which your wisdom and your writing has expanded my horizons, set me ablaze with intellectual curiosity, and excited my passion for humanity’s potential. You cannot know how much you have given me, and how your work continues to enrich so many lives. But that regret quickly evaporates when I realize how fortunate I am to exist — and how wonderful it is that I was taught to read and raised to value education, so that I would eventually come across your writing and be further inspired in my quest for knowledge and for a more peaceful world.

I suppose the best ‘thank you’ I can offer is to try to live out some of your ideals as best I can, and to share your work with others. Your empathy and compassion, your wisdom and pragmatism, your skepticism and curiosity, your science advocacy, and your talents as a writer have inspired so many people to ask important questions, to treat others kindly, and to work for a better pale blue dot. Your legacy is great — and even though you are no longer living, it will continue to live on for years beyond my own short time here.

You wrote in Cosmos: “Where are we? Who are we? We find that we live on an insignificant planet of a hum-drum star lost in a galaxy tucked away in some forgotten corner of a universe in which there are far more galaxies than people.” And yet, thanks to your work, our planet feels just a bit more significant than it did before I knew of you. You remind me to be mindful my own insignificance, and yet you also inspire me to try to do something of significance with the life that I have. For that — though I have never met you — this small creature loves you.

Thank you,

Chris

Chris Stedman is the Assistant Humanist Chaplain at Harvard and the Values in Action Coordinator for the Humanist Community at Harvard. He is the author of Faitheist: How an Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious, and the founder of the blog NonProphet Status.

Continuing the Class Discussion

In the wake of my Huffington Post piece last week, “The New Atheist Movement Should Care About Poverty,” a variety of commentators—some a part of the movement, some unaffiliated atheists and agnostics, some religious—have weighed in response. From what I’ve read I’ve noticed some pretty general themes that the responses generally take, that I think warrant addressing. Naturally, I wanted to follow up and keep the discussion going.

First, something of a misconception that’s permeated the general response is probably a result of clumsy focus on my part. My main thesis was intended to primarily address class inequality, not just poverty. They’re certainly related: failing to effectively address poverty is indeed an instance of classism. “Class inequality”, at least in my definition, refers to something a bit more general though. Essentially, it’s the notion that in any given dimension of social justice, a (typically very small) class of elites are too distant from the underprivileged to understand or truly care about their plight (this is often directly correlated with income, which is why when you think “class” you’re likely to think in economic terms). Think environmental justice: the elites who don’t live in areas affected by climate change-induced drought or natural disasters can easily brush off the issue, as working towards fighting global warming often is at a disadvantage to them in the short-term.

So with that in mind, the problem I see in the atheist movement isn’t purely economic. The prevalent condescending attitude towards believers and the let’s-change-their-minds-by-arguing-with (at)-them grand strategy are indications of a distance from the experience of religious people, who are believe as they do for a variety of reasons and as a result of a variety of external forces. Again, this is fairly obvious, I think, in the case of the movement’s treatment of poverty: in Debbie Goddard’s recent Skepchick post, she advocated for improving education in low-income communities as a more effective, and far more benevolent in the long run, method of enhancing critical thinking. A bus campaign in the South Side of Chicago isn’t just an ineffective tactic to this end—it’s actually harmful, both to the movement’s image and to the well-being of the community.

So with that in mind, the problem I see in the atheist movement isn’t purely economic. The prevalent condescending attitude towards believers and the let’s-change-their-minds-by-arguing-with (at)-them grand strategy are indications of a distance from the experience of religious people, who are believe as they do for a variety of reasons and as a result of a variety of external forces. Again, this is fairly obvious, I think, in the case of the movement’s treatment of poverty: in Debbie Goddard’s recent Skepchick post, she advocated for improving education in low-income communities as a more effective, and far more benevolent in the long run, method of enhancing critical thinking. A bus campaign in the South Side of Chicago isn’t just an ineffective tactic to this end—it’s actually harmful, both to the movement’s image and to the well-being of the community.

“The movement”—I want to be entirely clear in that my prescription is not an attack on atheists as a whole, nor is it a claim about what someone who identifies as an atheist would naturally or inherently believe. The network of individual activists and organizations that form the political movement that has emerged in the last decade was the subject of my piece, and is the subject of my criticism. I count myself a part of that movement, it’s the bulk of my resume, and operating in the mindset of “clean your own backyard”, I want to see its efforts to build a better world enhanced and properly directed. Whatever the definition of “atheist” or “humanist” is, I’m addressing a problem with the political movement, not necessarily with individuals.

That said, the movement’s leaders and loudest voices are indeed those that I want to change, primarily because they form of the image of the movement and have the sway to enact great change in its mission. One of those leaders, American Humanist Association president Roy Speckhardt, holds that the outreach done by the likes of American Atheists and Richard Dawkins, problematic or not, “aids in reaching out to a broader audience,” according to a recent article in the Christian Post. He offered praise for Dawkins, whose talks “draw thousands” and whose foundation has “600K followers on Twitter” (is that really a valid measuring stick?). In short, he decried the notion that Dawkins is “elitist” because he leads in the movement’s outreach. The misguidance here: regardless of how many their voices “reach,” those who will identify with and be sympathetic to their voices are going to be a vastly smaller set if what they’re saying is divisive and conceited. Further, given the nature of their statements and campaigns, they are right now still only reaching out to a particular overclass. Richard Dawkins is playing to the educated—not the clever, not the curious, but those in or connected to academia. His outreach, in hostilely mocking and demeaning believers—labeling them “deluded”, encouraging his constituents to “show contempt for the religious”, and, of course, likening religious upbringing to child abuse—is toxic no matter how many ears it reaches.

But, this next sentence, I think, is critically important regarding my intentions. I’ll put even put it in bold. Cntrl-B: I do not think that the movement never addresses poverty, or that specific leaders are wholly silent on the topic. And to be fair, I never said either of those. The problem I see is with the movement’s grand strategy, and with the focus and collective statements of the leaders. Yes: Sam Harris has written about taxing billionaires. Sam Harris, in The End of Faith, also holds that we should fight Islamic terrorism by devoting our time and resources proving the Quran wrong rather than aiming primarily to break down gender inequality, relieve poverty, and improve education in the Middle East. I don’t doubt that plenty of the movement’s membership thinks America’s rigged economic system and continued oppression of the poor are screwed up. What I doubt is that we’re taking sufficient measures to combat these modes of inequality, as they perpetuate other areas of social justice that we already and rightly care immensely about. And furthermore, I know of almost no places in the seminal atheistic literature that discuss class and economic inequality, despite extensively commenting on LGBT rights and gender equality. We all want to fast-track our goals in these dimensions of social justice, but we’re making that extensively difficult—if not impossible—when we maintain an elitist mindset.

Lastly, while I speak directly to the atheist movement, I certainly don’t think overcoming poverty is only or ought to be primarily on the shoulders of the nonreligious. The atheist movement simply has considerable power, in their institutions and their influence, and I believe it ought to be directed at combating the pervasive class divide that permeates and sustains so much of the social and economic inequality in our time. This journey should be undertaken alongside our peer moral communities—and indeed, religious communities are our peers—for only through ubiquitous compassion, unmarred by tribalism, can we succeed. We have an obligation to strive to relieve the suffering of those less privileged than us—this begins with identifying who they are, and having empathy rather than ego.

Walker Bristol woke up this morning and realized, to his dismay, that he is the President of the Tufts Freethought Society and the Director of Communications for Foundation Beyond Belief . This is especially peculiar considering he grew up as a high school wrestler-pianist in North Carolina and intended to become Luke Skywalker for an undisclosed period of his life, eventually settling for a Star Wars tattoo. The Tufts Political Science and Religion departments suffer his enrollment. He writes about social activism and art in the Tufts Daily . His diet consists of hummus. He tweets nonsense on all these fronts @WalkerBristol .

February 8, 2013

Something that Sam Harris and Deepak Chopra can agree on

In a recent conversation with Oprah Winfrey, Deepak Chopra explained why meditation has nothing to do with religion:

There are breathing meditations in every tradition. There are body-awareness meditations in every tradition. And there are variations of mantra meditation. It has nothing to do with belief or ideology or doctrine. It’s a simple mental technique to go to the source of thought.

Though the idea of a mental technique going “to the source of thought” seems to have Chopra’s characteristic fuzziness, I appreciate that it seems as if everyone—from Sam Harris to Deepak Chopra—can agree that meditation is a secular practice.

I’ve never done it myself, though I’ve considered it once or twice. Sam Harris, writing on the topic, says:

The quality of mind cultivated in [the meditation practice of] vipassana is generally referred to as “mindfulness” (the Pali word is sati), and there is a quickly growing literature on its psychological benefits. Mindfulness is simply a state of open, nonjudgmental, and nondiscursive attention to the contents of consciousness, whether pleasant or unpleasant. Cultivating this quality of mind has been shown to modulate pain, mitigate anxiety and depression, improve cognitive function, and even produce changes in gray matter density in regions of the brain related to learning and memory, emotional regulation, and self awareness.

I’ve argued before that religion is far more than just a sterile series of metaphysical prepositions that are either true or false. Religions have power as social institutions, moral communities, and shapers of cultural practice which might be unrivaled by anything that exists in the secular sphere. These aspects of religion can have benefits that extend far beyond the question of whether or not god exists, so it’d be hasty and shortsighted at best to condem these aspects without taking a serious look at what structures and practices we can beneficially apply to secular living.

I think this idea has a lot of promise, even though it’s come under a lot of scrutiny—one need only look at the response among atheist bloggers after Alain de Botton’s TED talk and subsequent book, Religion for Atheists, was released last year. But it was that type of thinking that led me to try out Lent as a willpower hack for veganism, and, though I’m still working on making the transition, I’m much further along than I otherwise may have been. This exact same logic applies to Sam Harris’s efforts to take spirituality and meditation to a more mainstream, less mystical place.

To me, these can only be good things. There may be a tendency among atheists to overcorrect for the harms they see in religion, but there’s no reason to cut off our collective noses to spite our face. Sam Harris wrote on the topic of spirituality that “[w]e must reclaim good words and put them to good use.” The same holds for good practices.

Sam Harris and Deepak Chopra debated “Does God have a future?” on ABC’s Nightline in 2010.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

February 7, 2013

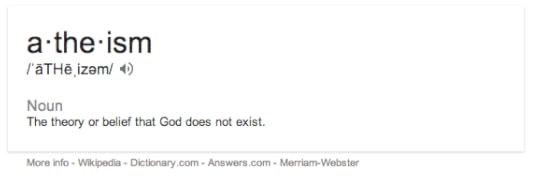

For a Substantive Definition of Atheism

My post about the uses of “atheism” and “agnosticism” has gone up on the Huffington Post religion section, and I’ve been mulling it over for a few days. I want to focus specifically on some uses of the word atheist, because they are as muddled as the uses of “agnostic.”

Google can’t possibly be wrong. Neither can the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

I wrote in my post that I reject the awkward, clumsy, and evasive definition of atheism as “the lack of a belief in any god or gods.” This has the benefit of putting something at stake for atheists—namely that we can be right or wrong—and it also keeps us from artificially bolstering our numbers. An agnostic would find little to support in the projects of American Atheists, so I think disbelief and uncertainty should remain distinct positions when it comes to God.

This refined definition has the added benefit of saving us from some awkwardness later on . Some atheists often like to hold that atheism is the default position, pithily claiming that we’re born atheists. While this might have a bit of rhetorical force, it just further demonstrates the limits and absurdity of the clunky lack-of-a-belief definition. If babies are atheists, what else? Rocks? Chairs? Galaxies? Mitochondrial DNA? That can’t possibly be right. It would be arbitrary to limit the definition to people, but it seems wrong that objects should count as nonbelievers. You might argue that it’s necessary to be able to believe in God in order to count as an atheist, but then that naturally excludes babies. We save ourselves some headaches by using the stronger definition.

This also means we have to ditch the awful “you’re an atheist about all the other gods you don’t believe in” argument, or the “everyone’s an atheist, we just believe in one less God than you do” argument.

Christians might think Muslims off about a few details, but atheists reject the entire package. There’s so much Christians and Muslims have in common that atheists reject outright—the existence of an all powerful, all knowing, maximally good deity that looks after us, has a plan, vindicates the righteous, gives us life after death, and so on. If you think that someone can believe all of that, but still be an atheist towards something, then you must have a very weak conception of “atheist” as a label. Such quips might have some persuasive force for rejecting a few cultural specifics of each religion—the divinity of prophets, the historic validity of holy books, trustworthiness of purported miracles, and so on—but that itself has nothing to do with whether or not God exists.

Let me argue again for why it’s important that atheism mean something more substantial. It forces us to take responsibility and ownership over our own beliefs—instead of being stuck with a lame lack-of-belief, we get an active, supported, evidence-based position. It puts something on the line for us—instead of pointing out weak arguments for the other side, we need to present strong arguments for our own. This pressure can only be a good thing if we’re trying to find out what’s true, because it exposes our beliefs to scrutiny.

Lastly, it gives us something more substantial as a base for a movement—a lack of a belief seems strange like a strange thing to orient around. There’s no sense in getting together a group of non-football players, as the jokes tend to go. But, to extend the silly metaphor, there is an obvious reason why people who might think that football is harmful should rally together. A belief provides something in common, even if that belief is the negation of another belief (because all beliefs can be framed as a negation of something else.) Under the definition I’m advocating for, an atheist movement makes sense. Under the lack-of-a-belief definition, the case for an organized movement doesn’t stem much further than pragmatic happenstance.

Semantics are often a tricky thing to argue, and I don’t expect the matter to be settled any time soon. I think, though, that it’s time to get past this limp definition of atheism to something more appropriate for a serious position and movement.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

February 4, 2013

Is tribalism and group-think always a bad thing?

Was all the time I spent here rooting for my team just encouraging dogmatism and tribalism? (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

I spent a few hours last night streaming the Super Bowl online, and, general awfulness of football notwithstanding, I actually enjoyed it. To be fair, that was largely because of Beyonce’s (amazing) performance and the fact that the new episode of HBO’s Girls aired a day earlier to accommodate the new Sunday lineup. That aside, there’s something just exciting about sports.

The relationship between religion and sports is often discussed, in fact Marcus Mann posted a great piece about this yesterday. It’s less common, though, to address what the two might have in common.

Eli Federman wrote an interesting piece for the religion section of the Huffington Post, recently, about why he wouldn’t be watching the Super Bowl. He concludes:

But as a society we should be mindful of the cult-like traits of groupthink, tribalism and consumerism — which blind obedience to sports can cultivate.

Leaving aside the serious issue of consumerism, I want to focus specifically on tribalism and dogmatism. These two things are often a particularly harmful mix in the world, and it’s the opinion of many of us here at NonProphet Status that it’s these things, not religion itself, that leads to many of the problems atheists point out. But does it necessarily follow that any indulgence of these things must necessarily be bad? Are ttribalism and dogmatism things that can be cultivated and applied to other, less benign aspects of our lives?

I’m somewhat skeptical. This may be pessimism or cynicism on my part, but I suspect that our status as a social primate will always leave a hole that groupthink and tribalism fit quite nicely in. It seems to me that finding something fun and harmless to substitute something potentially more harmful might actually be a responsible decision.

I might irrationally and dogmatically think that Yale is better than Harvard. I might root for us at a football or hockey game, feel a tinge of schaudenfreude when rival students get kicked out for cheating, or get unjustifiably happy to run into another alumnus—even one I’ve never met. There’s certainly nothing rational about any of this, but so long as it’s kept, like all things, in moderation, then what’s the harm?

I suspect this might relate to a broader attitude about similar issues, and I think it’s a common source of controversy. Does pornography serve as a harmless sexual outlet, or does it teach us to treat women’s bodies as objects and commodities, increasing the risk of sexual violence down the road? Are violent video games harmless fun, or does it allow us to more easily morally disengage from real-life violence? I’m sure we can all think of more cases.

These are empirical questions that might soon be answered (but at least in the case of violent video games, research has been going on for decades, and the answer still seems hazy. I think the case might be weak, but there’s still a case and it’s still not settled). But until then, how should we be treating ostensibly benign actions that may support more insidious behaviors or tendencies later on? Should we treat them as catharses, or proper objects of a better-safe-than-sorry mentality?

I find myself leaning towards the former, but I’m not sure if I’ve got a particularly strong argument for why.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

February Appearances

This post originally appeared on faitheistbook.com.

Below are my scheduled events for the month of February – these are subject to change and new ones may be added, so please be sure to check back! -Chris

Feb 5, 7 PM

Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY

Speech and workshops

Sponsored by Better Together Syracuse, Syracuse Secular Student Alliance, Syracuse Interfaith Student Council, and Hendricks Chapel

More information

Feb 15, 12 PM

Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Conversation with BuzzFeed’s Chris Geidner

Sponsored by Georgetown’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs & LGBTQ Center

More information

Feb 19, 6 PM

Portland State University, Portland, OR

Speech and meetings

Sponsored by Freethinkers of PSU and the Center for Inquiry – Portland

More information

Feb 20, 6 PM

Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR

Speech and workshops

Sponsored by Interfaith Community Service, Human Services Resource Center, and Pride Center

More information

Feb 21, 7 PM

University of Oregon, Eugene, OR

Speech

Sponsored by the Alliance of Happy Atheists

More information

Feb 24, 4 PM

Revolution Church, New York City, NY

Talk

More information

Feb 25, 7 PM

Columbia University, New York City, NY

Speech

Sponsored by the Columbia Humanist Society

‘Faitheist’ Excerpt: A Pastor Saved My Life

This post originally appeared on faitheistbook.com.

Following the essay adapted from Faitheist recently published by The Advocate, Huffington Post Religion and Huffington Post Gay Voices have published a piece, also adapted from the book, about what happened when my mother found out I was gay and took me to speak with a minister.

Check out a selection below, and click here to read it in full.

This piece was adapted from Faitheist: How an Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious (Beacon Press, 2012).

“I’m… gay… and I don’t know why God won’t answer my prayers.”

That was the opening line of a journal I kept during my adolescence, the contents of which detailed my private struggle as an adolescent to reconcile my sexuality with my fundamentalist Christian beliefs.

A week before my 14th birthday, my mom found that journal.

Picking me up from an event, she told me that she read it, and that she loved me. I sobbed and went downstairs to my room, refusing to leave for the rest of the day.

The next morning, I slept in. Eventually I woke up and, after lying in bed for an hour staring at the spackled ceiling, went upstairs.

My mom was sitting at the kitchen table with a glass of water, working on some insurance paperwork. She looked up at me and said: “I scheduled a meeting with a minister. Let’s go.”

February 3, 2013

God is Amazing: Revisiting Religion and the NFL

As a group, we at NonProphet Status aren’t the most engaged in football. But even though I’m more excited for Beyonce’s half-time show than the actual game (I’m expecting something like this), the Super Bowl, and football more generally, has huge cultural currency in the United States. Unsurprisingly, there are some really interesting ways that religion is involved. Marcus Mann was kind enough to share some of his thoughts with us for this special occasion:

In the spirit of the Super Bowl—America’s annual holiday of television, violence and cheese—I’d like to take a moment to resurrect a topic that has been dormant lately except for a few hesitant whispers.

In the spirit of the Super Bowl—America’s annual holiday of television, violence and cheese—I’d like to take a moment to resurrect a topic that has been dormant lately except for a few hesitant whispers.

It wasn’t long ago that every angle of the religion-sports dyad was torn open, discussed, debated, and reported ad nauseum as the born-again, media savvy phenom Tim Tebow rushed and passed his way into the NFL playoffs and Americans’ hearts. His star has faded, though, and so has that hope of many an American that maybe, just maybe, there was actually some transcendent power guiding Tim Tebow and his oft-critiqued throwing motion toward greatness.

The topic of God and sports has died down since 2011. But after the Baltimore Ravens dispatched my beloved New England Patriots in this year’s AFC Championship game, I found myself wondering again about the various intersections of our country’s two favorite modes of collective worship.

After the final whistle had blown in that fateful game, Baltimore linebacker Ray Lewis, who will be retiring after seventeen years in the NFL and is a sure first ballot hall of famer, put on one of the most elaborate displays of triumphal piety I have ever seen in professional sports. Tearful and jubilant praise to God was interrupted intermittently for a series of scripturally infused post-game interviews and a few moments of prostration on the grass of the football field under the flashing lights of encircled photographers.

This kind of religious effervescence was also on display during Lewis’s post-game ritual dance in the middle of the field after winning his last home game in Baltimore; a dance that he performed before games throughout his career. Fans of French sociologist Emile Durkheim might imagine him, if he were alive today, blogging the GIF of that last dance, the Raven streaking along Ray Lewis’s helmet in all its totemic glory as the crowd cheered him on, with the heading, “OMFG, is everyone getting this?!” Or perhaps he could just embed another GIF under it of someone dropping a mic.

Before defeating the Patriots, Ray Lewis and the Baltimore Ravens had to take care of Peyton Manning and the Denver Broncos first at Mile High Stadium in Colorado; a game in which, like with the Patriots, the Ravens were unanimous underdogs. In what was either a moment of serendipity or a stroke of cinematic artistry, CBS panned their camera to the image of a vanquished Peyton Manning trotting off the field, accompanied by the sound of Ray Lewis attributing his team’s victory to the will of God in a post-game interview.

As Peyton Manning jogged into his offseason, it was hard not to conclude, by Lewis’s logic, that God had evidently not chosen him.

My point though isn’t to note the logical inconsistencies when Lewis shouts, “God is amazing,” after winning football games, or to otherwise critique Lewis’s religious enthusiasm. Many have already pointed to the innumerable members of the human race who have never won their own personal equivalent to an AFC Championship game, let alone had access to enough food to have a chance at any kind of personal success at all.

Instead, I wonder what it is about Lewis that has largely excused his piety from the scrutiny of the American culture wars while Tim Tebow’s faith engendered immediate controversy.

Of course, one can immediately consider the issue of race and by extension how white Evangelicalism and black conservative Protestantism are treated differently by religious pundits and the mainstream media. A good example might be the issue of how Barack Obama took the risk of alienating black Protestants by including gay marriage in his platform – a tension that was noted but often unexplored (except by a few) as it inevitably leads to a confrontation with homophobia in black Protestant communities. It is an issue that would be awkward, to say the least, for a largely white institution to explore in depth.

There might be a simpler and more direct possibility, though, that relates theology and language to explain the difference in how Ray Lewis’s and Tim Tebow’s brands of jock Christianity were received. Tim Tebow, for example, began all of his post-game interviews with the words, “First of all I would like to thanks my lord and savior Jesus Christ.” Ray Lewis, however, often ends his accounts of collective victory with the words, “God is amazing.”

We should appreciate the exclusivity of the former and the inherent ecumenism of the latter. While Tim Tebow was sounding a dog-whistle to all his fellow born-agains, attributing his success to a personal relationship with his specific deity, Ray Lewis’s was an exclamation of awe that even the most secular of us can recognize and translate: life can be amazing and even transcendent. To put it another way, if we are to take Ray Lewis’s rhetoric at face value, no one is necessarily going to hell. I’m not sure we can say the same thing about Tim Tebow.

The philosophical hypocrisies of sports theology will always be with us and will not be going away anytime soon. Ray Lewis’s still vague role in a double-homicide in 2000, an incident where he subsequently pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice and settled out of court with the victim’s families for an unspecified amount of money, obviously has implications in a discussion of his faith. Not to mention the more recent accusations that Ray Lewis used banned substances like, of all things, antler spray to help recover from a torn tricep faster than any athlete ever.

Whatever the specific issue or athlete, these asymmetries of religion and action will inform conversations indefinitely. Perhaps, though, we can begin to differentiate between strains of exclusivity and ecumenism, however sincere or unintended, in our sports figures’ rhetoric. Although Ray Lewis’s public piety has ruffled a few feathers, there does seem to be some consensus:

While the unfaithful might find Ray Lewis’s religious effusions annoying, Tim Tebow’s evangelical specificity bordered on the offensive.

Tribal loyalty still works on the football field and even in the stands where fans sport their teams’ colors and revel in the unity of their imagined community. After that final whistle blows, though, most athletes, including Ray Lewis, seem to remember that football is for everybody. The language we use to describe our collective experience with the game should reflect that.

Marcus Mann lives with his wife in Carrboro, NC and is a Masters student in Religion at Duke University. When he’s not studying contemporary American atheist and humanist social movements, he enjoys sipping IPA’s while watching his kittens destroy his apartment. You can follow him on Twitter.

February 2, 2013

The New Atheist Movement Should Care About Poverty

Originally featured on Huffington Post Religion.

When new atheism emerged at the beginning of the millennium, perhaps the quickest stereotypes to flank authors like Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins were “elitist” and “self-satisfied.” Many in today’s atheist movement — the collection of organizations and activists working to build a culture safer for nonbelievers, combat dogmatism and in some cases eliminate religion itself — would dismiss these stereotypes as a baseless smear campaign by their adversaries. We value truth and think we’re right about something — which hardly seems different from the attitude of many believers. That itself doesn’t mean we consider ourselves “superior” to them.

There’s something toxic, though, that permeates this movement, something that may well inspire and support the stereotypes that have lingered for years. The atheist movement, in composition and purpose, has in the last decade failed to demonstrate a meaningful dedication to fighting economic inequality and building a safe space for nontheists regardless of their socioeconomic class. Despite all their talk of building a better world and upholding diversity, contemporary atheism and humanism’s most prominent authors and leaders have been suspiciously silent on the topic of poverty. This limits the movement’s ability achieve universal compassion, and renders it unattractive to those who don’t occupy a comfortable spot on the social hierarchy.

What’s even worse: the atheist movement’s implicit dismissal of class inequality greatly hinders its ability to build meaningful and sustainable partnerships with other moral communities, either as a function of or a result of this disregard. It creates distance between organized atheism and religious groups that are predominantly composed of the underprivileged. Without these partnerships, the idea of building “a better world” is not only unachievable, but incoherent…

…continue reading at HuffPo Religion!

Walker Bristol woke up this morning and realized, to his dismay, that he is the President of the Tufts Freethought Society and the Director of Communications for Foundation Beyond Belief . This is especially peculiar considering he grew up as a high school wrestler-pianist in North Carolina and intended to become Luke Skywalker for an undisclosed period of his life, eventually settling for a Star Wars tattoo. The Tufts Political Science and Religion departments suffer his enrollment. He writes about social activism and art in the Tufts Daily . His diet consists of hummus. He tweets nonsense on all these fronts @WalkerBristol .

February 1, 2013

Simplifying our language: a defense of agnosticism

I alluded to this briefly in my most recent post about Humanism, but I don’t like that our definitions of atheism and agnosticism are conflated and confused. The language and labels we use ought to tell us something substantive about what we believe. But as it stands, the words “atheist” and “agnostic” don’t really tell us much at all. Many atheists often argue that everyone who isn’t a believer is an atheist, including babies and many who identify as an agnostic. But this muddles and confuses what really should be two separate positions on the existence of God, and I think we’re better off keeping them separate.

Knowledge vs. Belief

The argument goes that atheism and theism describe what you believe, while agnosticism and gnosticism describe what you know. Since most agnostics don’t actively believe that God exists, then they should be considered atheists—even if they don’t know one way or the other. But even though people treat knowledge and belief like they’re very different things, they’re really not. People like to construct infographics where belief and knowledge are orthogonal to one another, but knowledge is actually just a specific kind of belief.

This conversation often gets confused by our degree of confidence in our beliefs, but knowledge isn’t determined by confidence—knowledge is simply a belief that is both true and justified (Gettier thought-experiments notwithstanding). It just so happens to be that we tend to be confident in beliefs that we think are true and justified. So confidence isn’t a criterion for, but rather a consequence of, knowledge. Similarly, many like the distinction between strong and weak atheist, or gnostic and agnostic atheist, because they reflects degrees of confidence. But why should we capture confidence with our labels? We don’t do this with any other ideology—there are no specific labels for a strong Catholic and a less certain Catholic—they’re all just Catholics.

So knowledge about God’s existence isn’t useful in a label at all, because it doesn’t tell us anything about your belief—few people would admit their beliefs aren’t justified, and whether or not God exists is completely independent of your beliefs about it. Whether it’s knowledge or belief, your attitude towards the existence of God is exactly the same.

Attitudes towards an idea

There are really only three ways to describe an attitude toward an idea—you can think it’s true, you can think it’s false, or you can have no idea at all.

Take the following statement: there is an even number of women named Mary in the state of Connecticut. You can believe that this is true—maybe you did a census or something. You can also believe that it’s false, because maybe the census showed an odd number of Marys. But you can also have no belief about the number of Marys at all—I’d imagine this is where most of us stand on this issue. Colloquially, you’d just say “I don’t know.” In other words, you could say you’re agnostic about it.

We talk this way all the time, so why make it more complicated for God?

Agnostic-atheist is a clunky, awful and vague label

I’ve often seen atheists argue that agnostics are really just atheists, based on an awkward definition of atheism as “a lack of belief in a deity.” This is sometimes based on something of an etymological fallacy, noting that the prefix “a” signifies negation, therefore “a-theists” are simply those without theism. Agnostics would technically qualify as atheists since they aren’t believers. But I suspect few making that argument would also argue that atoms are thus indivisible because the suffix “tom” refers to the word “cut” in Greek. The etymology of a word shouldn’t strictly dictate how we ought to define it.

Historically and philosophically, atheism has distinctly been the belief that God doesn’t exist (The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines atheism as such, which is about as definitive a source as you could want). There have often been those that have argued for atheism to capture everyone except explicit theists, and this might make sense from a theist’s perspective—it might be helpful to have a word to capture everyone who isn’t you.

But it seems useless to group people who think there are an odd number of Marys in Connecticut with people who don’t believe one way or the other, so why do we lump atheists and agnostics together? If you tell me you’re an agnostic-atheist, I don’t learn much about your attitude towards God—assuming I don’t lump you in with the somewhat archaic idea that agnostics are those who think that the existence of God is in principle unknowable. I really only learn that you’re not a theist—how can an ostensibly more specific label tell me less about what you believe?

Atheism is better as a label for a specific position

Do you think atheism can be right or wrong? Then you can see where I’m coming from. There’s no sense that “lacking a belief in a deity” can ever be true, because it doesn’t make a specific claim. But if we stick with atheism as the belief that God does not exist, then it does. It’s specific, concrete, and, most importantly, potentially true or false. It puts something at stake for atheists. Instead of simply saying “there is no evidence for theism, the burden of proof is on them” we have to say “here’s what we believe, and here is our evidence.” It’s what atheists have been doing for centuries, and it’s a cop-out to define away responsibility for our position, just so we can artificially bolster our numbers with vague labels.

That leaves us with three commonsense, simple, and (somewhat ironically) more specific words for our religious discussions. Theists believe that God exists, atheists believe that God doesn’t exist, and agnostics don’t believe one way or the other—there’s no reason to make it more complicated than that.Of course, this post isn’t meant to be definitive, but I think it captures everything we’d want our labels to capture. I’m open, though, to being convinced otherwise.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.

Vlad Chituc is a lab manager and research assistant in a social neuroscience lab at Duke University. As an undergraduate at Yale, he was the president of the campus branch of the Secular Student Alliance, where he tried to be smarter about religion and drink PBR, only occasionally at the same time. He cares about morality and thinks philosophy is important. He is also someone that you can follow on twitter.