Mary Sharratt's Blog, page 5

August 4, 2011

Women & the Crusades: guest post by Nan Hawthorne

Today's guest post is by Nan Hawthorne, whose new novel Beloved Pilgrim explores the Crusade of 1101 from the perspective of a woman who went off to fight.

During my own research of Hildegard von Bingen, I uncovered this short description of female crusaders from the Disibodenberg Chronicles, written by the monks of the abbey of Disibodenberg where Hildegard lived from the age of eight as a child anchorite:

Not only men and boys, but many women also took part in this journey. Indeed females went forth on this venture dressed as men and marched in armour . . .

--From the Disibodenberg Chronicles, as cited by Fiona Maddocks in her book, Hildegard of Bingen: The Woman of Her Age.

Although the fiction might be romantic and compelling, we can't neglect certain historical realities. Muslims and Jews regarded these "Holy Wars" as genocide. Indeed, in Rhineland German cities and towns such as Mainz and Bacharach, many Jewish people met their deaths in the tumult of the crusading fervour.

The Crusade of 1101 and Beloved Pilgrim by Nan Hawthorne

The initial research I did to write, Beloved Pilgrim, had everything to do with my choice of the dates and events portrayed. Though many of us are familiar with battles and figures from the Crusades, the Crusade of 1101, though obscure by comparison, proved to be tailor-made for a novel. The actual event took place over only a few months and in itself was classic plotting, with a dramatic beginning, several setbacks, conflict not only between the crusaders and Turks but also between the Christian leaders who made such a mess of things, and the devastating conclusion. Reading more about the crusade, usually considered an extension of the First Crusade, I found that the context was ideal for character development and thematic requirements I already had in mind.

The chroniclers of this crusade did not experience it themselves, but scholar Steven Runciman was able to put together what is as close to a definitive history as possible. His work, A History of the Crusades: Volumes 1-3, was my and the rest of the world's primary source, along with the able help of Jack Graham, a medieval warfare enthusiast who helped me choreograph battle scenes and fixed some apparent inconsistencies in Runciman's account. That Graham had lived in Turkey was also very helpful.

Some may question whether a woman like Elisabeth could have fought as a knight. I was not able to find evidence of women who fought thus in the Crusades, but knowing about Joan of Arc, Boudica and Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, so I feel justified in portraying her as such. Her lesbianism is pure speculation.

One of the mysteries that came out of the Crusade of 1101 was what happened to Ida, Margravine of Austria, who disappeared and was never found again. The only theory extant, that she was captured and became the mother of a great Saracen leader, is easily dismissed as the man was already born when she arrived in Byzantium. This mystery provided me the opportunity as an author to suggest what may have happened to her and make it part of the story and my protagonist's journey.

I firmly believe that as an author of historical fiction I have a responsibility to make the setting, characters and events as authentic as possible, but I also believe that nothing can substitute for good storytelling. Fiction and history texts are not the same. It is the function and beauty of historical fiction to bring the reader into a historical context in such a way that he or she can experience it as close to first hand as possible. I therefore feel free to insert myself, my ability to speculate and extrapolate, making, as far as I see it something even more authentic than a straight retelling of historical record. The latter cannot even come close to telling the true story, if only because the historian focuses on primarily the people and places at the core of the events. A historical novelist can move the focus off these and onto the rest of the world and suggest how people at the time may have seen, reacted to and drawn their own conclusions.

Published on August 04, 2011 03:50

June 5, 2011

Beyond the Marquee: Toward a Common History

This article of mine was originally published in the February 2011 issue of Historical Novels Review.

Come and visit our panel "Are Marquee Names Really Necessary" with star authors Margaret George, C.W. Gortner, Susanne Dunlap, and Vanitha Sankaran at the 2011 Historical Novel Society North American Conference in San Diego, on Saturday, June 18.

Recorded history is wrong. It's wrong because the voiceless have no voice in it.

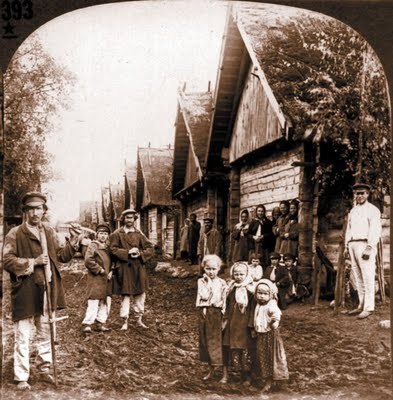

These are the words of the late, great Mary Lee Settle, author of the classic Beulah Land Quintet, published in the 1950's when both academic history and most historical fiction were narrowly focused on the elite. So many people have been written out of history: not only the vast majority of women, but also people of the peasant and labouring classes, and most people of non-European ancestry. In Settle's day, a more inclusive history seemed a far off dream.

"There's a revolution going on out there!"

Sarah Dunant, acclaimed author of The Birth of Venus and In the Company of the Courtesan, remembers this time. Speaking at the Bluecoat School in Liverpool in May 2010, Dunant described how she first fell in love with historical fiction when she was a twelve-year-old in postwar Britain, which she remembers as "a grey, colourless, bleak place" where nobody wanted to talk about the war. On the brink of adolescence, she found a wonderful escape in Jean Plaidy's novels of the crowned heads of Europe. These books not only opened up another world that was colourful and glamorous but they inspired Dunant's lifelong love affair with history. She went on to study history at Cambridge. "The history I learned," she recalls, "was the history of great battles, great empires, great men."

But what inspired Dunant to become a historical novelist were the sweeping developments in academic history that occurred after she left Cambridge in 1972. This new history embraced people who did not belong to the elite. She cites Joan Kelly-Gadol's 1977 essay, "Did Women Have a Renaissance?" as one of the turning points in the development of how we look at history.

Sarah Dunant is not only a champion of a more inclusive, non-elitist historical fiction—she also became an international bestseller by writing about people on the margins of history. Her most recent novel, Sacred Hearts, explores the secret world of Benedictine nuns in 1570 Ferrara, Italy—a cloistered "republic of women" where each choir sister had a voice and a vote in the daily chapter house meeting.

"Modern historians," Dunant explains, "know that there is a multiplicity of history—there is more than one history, one fact. The history I'm using has been hard won over the past twenty to thirty years." And this history allowed her to write novels about a past that simply wasn't regarded as history even thirty years ago. For Sacred Hearts, she has drawn on two generations of young historians who examined court records of nuns who got into trouble.

Similarly, I could not have written my most recent novel, Daughters of the Witching Hill, which is based on the true story of the Pendle Witches of 1612, without the drawing on groundbreaking social histories, such as Keith Thomas's Religion and the Decline of Magic; landmark works on Reformation Studies, like Eamon Duffy's The Stripping of the Altars and Ronald Hutton's The Rise and Fall of Merry England; as well as recent studies on historical cunning folk.

Is the tide, then, changing? Will this new history open the door to a Renaissance in the historical novel? Will more and more authors draw on this wider window into ordinary people's lives instead of rehashing the same old tired tales of Tudor royalty? Dunant believes that historical novelists possess every potential to be on the cutting edge of bringing this new history in an accessible form to a modern audience. "Wake up, there's a revolution going on out there in historical fiction!" Dunant told Lucinda Byatt in their May 2010 Solander interview.

Marquee names only, please

Although the world of academic history has moved on light years since the 1950s, historical fiction often appears to be stuck in a rut. In these recessionary times, an increasingly conservative publishing market urges new and established authors alike to play it safe by writing about famous historical figures, such as Tudor royalty, instead of drawing on a social history of the less privileged.

Speaking at the 2007 Historical Novel Society Conference in Albany, New York, agent Irene Goodman stressed the importance of "marquee names" in finding an audience for one's historical fiction. In the May 2010 issue of Solander, Goodman cited author Leslie Carroll's leap from midlist obscurity to major success with the sale of her trilogy of novels about Marie Antoinette. Goodman is not alone in stressing the importance of marquee names.

"The trend simply cannot be denied," Bethany Latham, Managing Editor of Historical Novels Review, observes. "For better or worse, publishers seem to prefer marquee names right now. They're the path of least resistance—easier to market since, in the mind of many publishers, celebrity protagonist equals ready-made audience. There's even a tendency for successful authors who began differently to evolve into something that better fits the prevailing mold—witness Philippa Gregory, who started out with the Wideacre Trilogy but has ended up with the familiar big-name Tudors and Plantagenets, and will be sticking with them for the foreseeable future."

Popular fascination with historical It Girls like Anne Boleyn helped launch the incredible resurgence in historical fiction within the past decade, most notably through Gregory's blockbuster, The Other Boleyn Girl. Literary agent Marcy Posner, speaking at the 2010 Historical Novel Society Conference in Manchester, UK, pointed out how Gregory's glittering evocation of the Tudor Court inspired a large group of female readers to make the leap from historical romance to mainstream historicals. It seems only natural for agents and editors to look for work that contains the same kind of hook that proved so successful for Gregory.

"My experience was that when I sent some of my work to an agent," says Elizabeth Ashworth, author of The de Lacy Inheritance, "she thought it was an engaging story and she liked my style of writing but she didn't think she could sell my work to a publisher because it wasn't about a well known king or queen. When I mentioned that I was working on another novel set in the reign of Edward III, she replied that if I wrote about Edward and Piers Gaveston, she might be interested. But that story has been written many times before and it was another story I wanted to tell – one about Lady Mabel Bradshaw who lived at that time but is relatively unknown."

"The marquee name, especially female, has become almost a requirement in historical fiction," says C.W. Gortner, author of The Confessions of Catherine de Medici. "My novel, The Last Queen, languished unpublished for years, with several of my rejection letters pointing out that Juana [of Spain] was not a 'known personage'. I persisted and eventually found success, but how many other writers give up?"

The insistence on marquee names was why author Jeri Westerson says she switched to writing historical mysteries. "I preferred to write about the everyman in an historical setting, but year after year, I was told by editors that my medieval stories needed to be about royalty or other noble personages. The kind of historical I wanted to write translated much better to the mystery genre. So now I write medieval mysteries (after some eleven years of peddling historical manuscripts and not selling them)." Her fourth Crispin Guest Medieval Noir, Troubled Bones, will be released in Fall 2011. However, other historical mystery writers embrace the marquee name trend by choosing a well known figure such as Elizabeth I or Oscar Wilde as their sleuth.

Susanne Dunlap, author of Liszt's Kiss and The Musician's Daughter, adds that in Young Adult Fiction, the pressure is to write "something that fits into the high school curriculum," which may well involve including famous personalities.

The bias can sometimes be found among HNS members themselves. Historical Novels Review Book Review Editor Sarah Johnson has noticed that reviewers tend to clamour for books about big names while novels about less familiar characters and settings can be harder to place.

Not even the most elite literary circles are immune to this trend. Hilary Mantel's Booker Award winning masterpiece Wolf Hall is set in Henry VIII's court.

A lack of diversity in the genre?

So does this push to write about marquee names help or hinder historical fiction?

"This is the backwash of celebrity culture," Dunant states, "and our greed for sensation and scandal. People read about Anne Boleyn when they tire of reading about Paris Hilton. We've gone back to kings and queens, a celebrity history, because we've squeezed Paris Hilton dry."

Must we all write like latter day Jean Plaidys and Georgette Heyers in order to meet our publishers' sales expectations? Bethany Latham laments to think that in today's climate, Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind, the bestselling historical novel of all time, might not be published because Scarlet O'Hara is a nobody.

Alison Weir, speaking at the 2010 HNS Conference in Manchester, presents a different viewpoint, arguing that her novels on figures such as Elizabeth I and Eleanor of Aquitaine are a legitimate way of reclaiming women's history, even though they are focused on elite women. As Keynote Speaker at the conference, Weir explained how she pitched a nonfiction biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine some years ago only to be told that not enough material existed on her to make her a worthy subject.

"I think many readers gravitate toward the familiar," Sarah Johnson observes, "and historical fiction readers in particular often choose novels that help them gain insight into a real-life character's mindset or behavior. In that sense, I can see why marquee names are so popular, and why authors are being encouraged to choose them as subjects. It's an automatic 'hook.'"

Johnson added that the industry's insistence on marquee names has the unfortunate drawback of creating a "lack of diversity of the genre."

"The push for 'big names' is primarily about name recognition," state N. Gemini Sasson, author of The Crown in the Heather. "The casual historical fiction reader scanning the shelves at the local Target store is more likely to linger over a name she recognizes, pick up the book and buy it, than an unknown. I do wonder though when a saturation point for some of these historical persons will be reached and the scales tip the other way."

"If I see another book on the Tudors, I'll scream!"

Which begs the question: are historical fiction readers beginning to reach their saturation point with historical celebrities? Eager to ape Philippa Gregory's success, many authors have tried to follow her formula, with mixed results. How many more novels about Tudor royalty can the public bear?

"Frankly, if I see another book on the Tudors, I'll scream," HNS member Monica Spence admits.

"When I'm book-buying, the Not Anne Boleyn Again Syndrome periodically strikes," Bethany Latham confesses.

Anne Gilbert says that she tends to shy away from fictional biographies. "No matter how well-written they may be," says Gilbert, "they tend to concentrate on pretty much the same well-known historical people."

"There are only so many 'ultra famous' women we can write about, whom publishers find commercial enough," C.W. Gortner observes. "Take, for example, Eleanor of Aquitaine; as fascinating as she is, how much more can be said about her without it becoming repetitious or whimsical in novelized form?"

A 2009 market research poll conducted by blogger Julianne Douglas on Writing the Renaissance indicates that only 11% of the people she surveyed buy historical fiction based on the appeal of marquee names alone. Readers want so much more out of their fiction: fascinating characters and storylines, arresting and richly realised settings.

Finding an audience

Following the Publisher's Weekly listings of best-selling historical fiction on her blog, Reading the Past, Sarah Johnson mentions Edward Rutherfurd, Lisa See, and Sandra Dallas as just a few commercially successful authors who have bucked the big name trend. Their novels reached a wide audience because they have additional hooks that attract readers, Johnson points out, such as strong book club potential, and they also appeal to many readers outside the core historical fiction audience. Bethany Latham praises Maggie O'Farrell as a successful author with a fresh, original voice, who is utterly unaffected by the celebrity trend, not to mention Kenneth Follett, whose blockbuster Fall of Giants saga depicts ordinary people against extraordinary historical backdrops.

However, HNS member Matt Phillips, who is writing a novel based on his ancestors on the Pennsylvania frontier, still feels that not enough historical fiction based on the lives of "real people" is reaching the reading public. "There are so many stories that can shed light on how the 'average person' lived, or might have lived, while also entertaining the reader, engaging his or her imagination and emotions authentically with the thrills and fears and hopes and challenges of living in another time. Yet relatively few such stories find their way to the shelves of our bookstores because publishers continue to emphasize the marquee names."

What happens when new or midlist authors embrace the lives of people on the margins of history? Gabriella West's novel Time of Grace (Wolfhound Press, 2002) is a daring work—a woman-centered look at a very male period in history, Ireland's 1916 Easter Rising, and also a romance between two young women. "It was successfully published but I'm not sure it was published successfully," West says. "It never really found its audience."

Joyce Elson Moore's has had a happier experience with her new novel, The Tapestry Shop, based on the life of Adam de la Halle, an obscure 13th-century musician. "His secular plays and music are still being performed," Moore explains, "and he was one of the last and greatest of the trouveres (like troubadours in southern France). He penned the first version of the Robin Hood legend, and I felt like his story had to be told. The book is getting a lot of attention, and I think one reason is that it is different."

Elizabeth Ashworth reports good sales on her own first novel, The de Lacy Inheritance. "I was lucky that my publisher Myrmidon Books was willing to take my novel, although the main character is a leper. It's selling well and I think that proves the publishers wrong who maintain that readers only want to read about kings and queens."

"Just give us variety."

"To be honest, I'm not sure I'd be able to work with the constraints of a documented marquee name," says Vanitha Sankaran, whose debut novel Watermark explores the life of a woman papermaker in late medieval France. "As a writer, I like the freedom of being able to create my own characters and stories while staying accurate to the era. As a reader, however, I'm interested in reading about all different t ypes of people, from the poor man trying to feed his pregnant wife to the merchant seeing his profits swallowed up by war. I wish publishers would take more risks across the whole genre and not focus on any time, place, or biographical person, but just give us variety."

Sarah Johnson agrees that "those who stick narrowly to celebrity characters are missing out on some wonderful stories! In particular, the Editors' Choice selections in Historical Novels Review demonstrate that historical fiction readers' most highly recommended books don't follow trends or fit into neat categories."

N. Gemini Sasson sums it up beautifully: "There are less well known historical figures that have stories worth telling, every bit as compelling and dramatic as those whose stories have been told a hundred ways already. Sharing their lives would do nothing but enrich our view of the past."

Perhaps we are indeed ready for a revolution in historical fiction.

"Time to Change the Marquee" by Julianne Douglas

"Bestselling Historical Novels of 2009" by Sarah Johnson

Published on June 05, 2011 03:57

April 3, 2011

Mary Frith: the Original Roaring Girl

[image error]

Behind Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker's sparkling stage comedy, The Roaring Girl, (ca 1607-1610), was a real woman, the notorious Mary Frith, aka Moll Cutpurse—a cross-dressing, hard-drinking pickpocket, fence, and Queen of Misrule.

-One of the many merry pranks attributed to Firth in Charles Whibley's A Book of Scoundrels.

Born in London in 1584 to a shoemaker and a housewife, Frith was an uncompromising tomboy who disdained feminine clothing. Instead she sported a doublet and men's breeches. She smoked a pipe and swore like a sailor. The original Jacobean Roaring Girl, she ran with a rough crowd, aping the lifestyle of the traditional Roaring Boys, young men who caroused in taverns before going on the streets to brawl and engage in petty crime. In 1600, at the age of sixteen, she was first indicted for thievery, stealing 2s, 11d.

By 1610, her reputation had inspired not only Middleton and Dekker's famous play but many other works, including John Day's 1610 drama, The Madde Pranckes of Mery Mall of the Bankside. These works sensationalised her scandalous behaviour. Men regarded women who habitually cross-dressed as sexually riotous and out of control. Yet Frith herself claimed to be uninterested in sex.

She did, however, revel in her notoriety. In 1611 she performed at the Fortune Theatre in an age where women on the stage were unheard of and female parts in plays were performed by boys in women's clothing. Frith, as always, appeared in breeches and regaled her audience by singing bawdy songs while playing the lute. Later in that same year, she was arrested for indecent dress and accused of prostitution.

In February 1612, Frith was made to do penance for her evil living at Saint Paul's Cross, an open air preaching cross on the grounds of the old Saint Paul's Cathedral in London. Before the crowd she wept copiously and appeared very penitent indeed, although John Chamberlain later observed in a letter that he thought she only wept on account of being "maudlin drunk, being discovered to have tippled three-quarters of sack."

In 1614, Frith wed Lewknor Markham in what appeared to a marriage of convenience, but she gave no signs of settling down. By the 1620s, she was working as a fence and a pimp, procuring both young women for her male clients and strapping young men to service middle class wives.

In 1644, records show that she was released from Bethlem Hospital after being cured of insanity.

An apocryphal tale goes so far as to claim that during the English Civil War, she robbed and shot General Fairfax, then escaped the gallows by way of a 2000 pound bribe.

However, her actual recorded death seems the least exciting episode in her long and colourful life. In July 1659, she died of dropsy in Fleet Street, London.

Read her fabulously embroidered biography in Charles Whibley's A Book of Scoundrels .

Behind Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker's sparkling stage comedy, The Roaring Girl, (ca 1607-1610), was a real woman, the notorious Mary Frith, aka Moll Cutpurse—a cross-dressing, hard-drinking pickpocket, fence, and Queen of Misrule.

The vintner bet Moll £20 that she would not ride from Charing Cross to Shoreditch astraddle on horseback, in breeches and doublet, boots and spurs. The hoyden took him up in a moment, and added of her own devilry a trumpet and banner. She set out from Charing Cross bravely enough, and a trumpeter being an unwonted spectacle, the eyes of all the town were clapped upon her. Yet none knew her until she reached Bishopsgate, where an orange-wench set up the cry, `Moll Cutpurse on horseback!' Instantly the cavalier was surrounded by a noisy mob. Some would have torn her from the saddle for an imagined insult upon womanhood, others, more wisely minded, laughed at the prank with good-humoured merriment. Every minute the throng grew denser, and it had fared hardly with roystering Moll, had not a wedding and the arrest of a debtor presently distracted the gaping idlers. As the mob turned to gaze at the fresh wonder, she spurred her horse until she gained Newington by an unfrequented lane. There she waited until night should cover her progress to Shoreditch, and thus peacefully she returned home to lighten the vintner's pocket of twenty pounds.

-One of the many merry pranks attributed to Firth in Charles Whibley's A Book of Scoundrels.

Born in London in 1584 to a shoemaker and a housewife, Frith was an uncompromising tomboy who disdained feminine clothing. Instead she sported a doublet and men's breeches. She smoked a pipe and swore like a sailor. The original Jacobean Roaring Girl, she ran with a rough crowd, aping the lifestyle of the traditional Roaring Boys, young men who caroused in taverns before going on the streets to brawl and engage in petty crime. In 1600, at the age of sixteen, she was first indicted for thievery, stealing 2s, 11d.

By 1610, her reputation had inspired not only Middleton and Dekker's famous play but many other works, including John Day's 1610 drama, The Madde Pranckes of Mery Mall of the Bankside. These works sensationalised her scandalous behaviour. Men regarded women who habitually cross-dressed as sexually riotous and out of control. Yet Frith herself claimed to be uninterested in sex.

She did, however, revel in her notoriety. In 1611 she performed at the Fortune Theatre in an age where women on the stage were unheard of and female parts in plays were performed by boys in women's clothing. Frith, as always, appeared in breeches and regaled her audience by singing bawdy songs while playing the lute. Later in that same year, she was arrested for indecent dress and accused of prostitution.

In February 1612, Frith was made to do penance for her evil living at Saint Paul's Cross, an open air preaching cross on the grounds of the old Saint Paul's Cathedral in London. Before the crowd she wept copiously and appeared very penitent indeed, although John Chamberlain later observed in a letter that he thought she only wept on account of being "maudlin drunk, being discovered to have tippled three-quarters of sack."

In 1614, Frith wed Lewknor Markham in what appeared to a marriage of convenience, but she gave no signs of settling down. By the 1620s, she was working as a fence and a pimp, procuring both young women for her male clients and strapping young men to service middle class wives.

In 1644, records show that she was released from Bethlem Hospital after being cured of insanity.

An apocryphal tale goes so far as to claim that during the English Civil War, she robbed and shot General Fairfax, then escaped the gallows by way of a 2000 pound bribe.

However, her actual recorded death seems the least exciting episode in her long and colourful life. In July 1659, she died of dropsy in Fleet Street, London.

Read her fabulously embroidered biography in Charles Whibley's A Book of Scoundrels .

Published on April 03, 2011 13:29

February 10, 2011

A Short History of Saint Valentine's Day

The origins of Saint Valentine's Day lie shrouded in obscurity. Saint Valentine himself, a third century Roman martyr, seems to have nothing to do with the romantic traditions that became associated with his feast.

Dr. Douce, in his Illustrations of Shakespeare, cited in The Book of Days, writes:

It was the practice in ancient Rome, during a great part of the month of February, to celebrate the Lupercalia, which were feasts in honour of Pan and Juno. whence the latter deity was named Februata, Februalis, and Februlla. On this occasion, amidst a variety of ceremonies, the names of young women were put into a box, from which they were drawn by the men as chance directed. The pastors of the early Christian church, who, by every possible means, endeavoured to eradicate the vestiges of pagan superstitions, and chiefly by some commutations of their forms, substituted, in the present instance, the names of particular saints instead of those of the women: and as the festival of the Lupercalia had commenced about the middle of February, they appear to have chosen St. Valentine's Day for celebrating the new feast, because it occurred nearly at the same time.

The first mention of Valentine's Day traditions in England originate from the 14th century writers Geoffrey Chaucer and John Gower who both allude to the folk belief that birds choose their mates on the feast of Saint Valentine, their patron.

In Britain, the mating flights of crows, rooks, and ravens can generally be observed by February 14. Here in Lancashire, I notice more and more birdsong each day as February advances and the birds repair their nests, preparing for a new cycle of birth and life.

Around 1440, John Lydgate's poem in honour of Queen Katherine, widow of Henry V, is the first to mention romantic traditions among humans associated with this date:

To look and search Cupid's calendar,

And choose their choice, the great affection.

People of both sexes sent tokens of admiration. You could either send a token to the romantic interest of your choice, or draw lots as to who would receive your Valentine. In 1470s Norfolk, the Paston family seems to have perferred drawing lots rather than sending tokens to a chosen person.

Actual Valentines could be quite costly. In 1523, Sir Henry Willoughby, gentleman of Warwickshire, paid 2S, 3d for his. Unfortunately no description of this costly item remains for us today.

After the Reformation, the feast of Saint Valentine was abolished, and yet the amorous traditions flourished.

By 1641, the system of casting lots for Valentines was so well known in Edinburgh that a wag waggishly proposed their new Lord Chancellor be chosen by the same method.

A Dutch visitor to London in 1663 observed:

it is customary, alike for married and unmarried people, that the first person one meets in the morning, that is, if one if a man, the first woman or girl, becomes one's Valentine. He asks her name which he takes down and carries on a long strip of paper in his hat band, and in the same way the woman or girl wears his name on her bodice; but it is the practice that they meet on the evening before and choose each other for their Valentine, and, come Easter, they send each other gloves, silk stockings, or sometimes a miniature portrait, which the ladies wear to foster the friendship.

In his diaries of the same decade, Samuel Pepys reveals how he would call by a colleague's house early in the day in order to make the man's daughter his Valentine. Pepys would also arrange for a young man to call to pay the same homage to Mrs. Pepys and bring her presents, which Pepys then paid for. One year when Pepys was short of cash, alas, no young man with presents appeared and Mrs. Pepys was quite irate. Eventually they settled on a yearly ritual, whereby Pepys's cousin paid a visit to honour Mrs. Pepys and bring her presents which Pepys knew she desired.

Sources:

The Book of Days

Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain

Short self-promotional addendum: DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL is now available in paperback and is a BookBrowse Recommended Book Club Read AND is the perfect Valentine's Day Gift for that special person who likes to read about real historical firebrands and 17th century enchantments.

Published on February 10, 2011 11:15

February 4, 2011

Hard hitting fiction

Tired of chick lit and looking for contemporary fiction with a bit more bite to it?

Randy Susan Meyers's hard hitting novel, THE MURDERER'S DAUGHTERS, has just been released in paperback. This book has been getting so much acclaim, it would be a pity to miss.

Randy Susan Meyers lives in Boston with her husband. She teaches at the Grub Street Writers Center and is a regular contributor to The Huffington Post. The Los Angeles Times called her debut novel, The Murderer's Daughters "a knock-out debut . . .all too believable and heartbreaking."

Be sure to check out her website.

Published on February 04, 2011 11:07

January 22, 2011

New Year, New Book

DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL, my novel exploring the true story of the Pendle Witches of 1612, is now out in paperback.

The wild, brooding landscape of Pendle Hill in Lancashire, Northern England, my home for the past nine years, gave birth to my novel, DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL, which tells the true story of the Pendle Witches.

In 1612, seven women and two men from Pendle Forest were hanged for witchcraft, but the most notorious of the accused, Bess Southerns, aka Mother Demdike, cheated the hangman by dying in prison. This is how Thomas Potts, describes her in THE WONDERFULL DISCOVERIE OF WITCHES IN THE COUNTIE OF LANCASTER:

She was a very old woman, about the age of Foure-score yeares, and had been a Witch for fiftie yeares. She dwelt in the Forrest of Pendle, a vast place, fitte for her profession: What shee committed in her time, no man knowes. . . . No man escaped her or her Furies.

Other books have been written about the Pendle Witches--both nuanced and lurid. Mine is the first to tell the tale from Bess Southerns's point of view. I longed to give her what her world denied her--her own voice.

History is a fluid thing that continually shapes the present. Set in an era of religious intolerance, political strife, suspicion, and social inequality, Bess and her family's struggle feels more relevant than ever, especially as we approach the 400th anniversary of the Pendle Witch trials in 2012.

I hope you will be as moved by their story as I am.

Here is a short video docodrama I shot with Outsider TV about a year ago:

Read an excerpt.

Read what the critics are saying about the book.

Where to buy:

Amazon.com

Amazon.co.uk

Barnes & Noble

Borders

Powells

Indiebound

The book is also available in e-book in both Kindle and Nook formats.

Published on January 22, 2011 03:44

December 16, 2010

Bringing Light to Dark Places

Warmest Midwinter Blessings to all my readers

It's all too easy to feel frazzled and stressed during this time of year when the ancient sacred significance of the season has been overshadowed by the commercialism of "Giftmas."

Midwinter is the darkest time of year, the time of the Winter Solstice, when the sun appears to stand still in the sky. Here, in the North of England, the darkness feels overwhelming. The sun does not rise until after 8:00 and sets by 3:30. By 5:00, it's pitch dark. Now imagine experiencing this before the era of electric lights and central heating.

This silent tide of year has been marked by sacred ritual from time out of mind. Modern Christmas has roots that reach back before the dawn of Christianity.

The ancient Romans celebrated Saturnalia, the Festival of Saturn, with much merry-making, gift-giving, and "misrule," as the masters waited upon their slaves. People decorated their homes with greenery. Rich and poor alike joined in the feasting. In Northern Europe, Yuletide festivities marked the Solstice and the return of the light. In De temporum ratione, the Venerable Bede (673-735) wrote that the Pagan Anglo-Saxons began their year on December 25, on a feast they called Modranecht, or Mother's Night, marked by ceremonies that lasted the entire night. Mostly likely this feast was connected with the cult of the Matronae, the female ancestors.

Although there is no scriptural evidence to suggest that Jesus was born on 25 December, the early Church embraced this Solstice tide as fitting for the celebration of the birth of the Son of Light. Traditionally Christmas lasted for Twelve Nights, from December 25 to January 6, the Feast of the Epiphany, once the old date of Christmas. During the medieval period, no villeins worked their lord's land during this time. In fact, their lord was obliged to provide a feast for them. As in the ancient Roman feast of Saturnalia, medieval Britons enjoyed a reversal of the social order by crowning a Lord of Misrule, a common born man who lorded it over the gentry to guarantee hilarity for all.

This was a time of carol singing, games, and "guizing" - wild processions in animal masks that draw on the lore of the Wild Hunt that swept down from the sky across Northern and Middle Europe during the Twelve Nights. This kind of guizing still takes place every Christmas in the town of Kirschseeon near Munich, Germany. Mummers wear elaborately carved wooden masks and run through the woods in the Perchtenlauf, in eldritch celebration of the Rauhnaechte, the twelve nights of Yule, a time of much superstition, when it was believed that old Gods roared through the sky and the dead spirits walked the earth. The Perchtenlauf takes its name from Frau Percht, a figure that is closely associated with Frau Holle, who may have her roots in an old Goddess.

Traditionally the time for telling ghost stories was not Halloween, but the Twelve Nights, time out of time when all kinds of uncanny things could come to pass. Animals spoke in human speech. Water turned to wine. The future could be foretold. All spinning stopped and no wheel could turn. Time stood still. The world held its breath, awaiting the return of the light. In Glastonbury, the Holy Thorn Tree on Wearyall Hill bloomed on Christmas day.

This beautiful short film invites viewers to devote 12 minutes on each of the Twelve Nights to silent contemplation of the mysteries of this season. Anyone, of any spiritual tradition, can reclaim the numinous grace of this time out of time.

A dear friend of mine has reclaimed the beauty and power of Hanukkah. She read about how Hanukkah didn't really start with the Maccabees, how it was a much older holiday than that - and originally about bringing light to dark places. "So in every way I can," she says, "I use this season to bring light to dark places. Literally, figuratively, whatever. Sometimes it's just about watching the sun go down, turning on the light in the dining room, and saying out loud, 'Thank you for this miracle of light in my home after the sun has gone.'"

May all of us bring light into dark places.

Wishing you all a joyous Midwinter and a New Year filled with happiness and peace,

Mary

The newly released paperback edition of Daughters of the Witching Hill is now shipping! You can order it here.

Published on December 16, 2010 02:44

October 31, 2010

All Hallows Tide in Pendle

When Halloween comes around, the popular imagination turns to ghosts and hauntings. And to witches.

Especially in my neck of the woods. I live in Pendle Witch Country, the rugged Pennine landscape surrounding Pendle Hill, once home to twelve individuals arrested for witchcraft in 1612.

Unfortunately Halloween seems to drag out all kinds of ghoulish speculation about historical witches and cunning folk in a way that is not only historically inaccurate but disrespectful to the dead. The Pendle Witches were not ghouls, but real people who were held for months in a lightless dungeon in Lancaster Castle, chained to a ring in the stone floor, before being tried without a barrister, condemned on the testimony of a nine-year-old girl, and then hanged. The historical truth is far more chilling than any fabricated horror story.

So let this All Hallows Tide be not an excuse for macabre speculation but let us light a candle in the memory of those men and women from Pendle Forest who died unjustly:

Elizabeth Southerns, Alizon Device, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redfearn, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, Jane Bulcock, John Bulcock, and Jennet Preston.

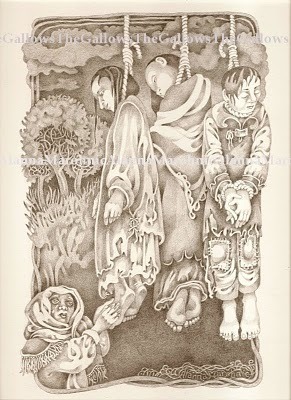

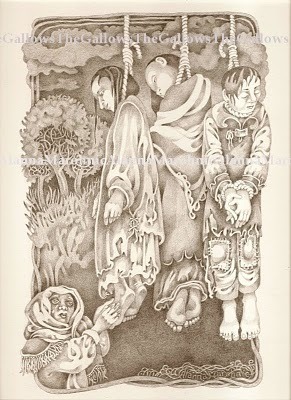

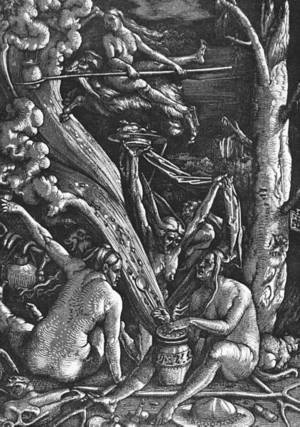

The artist Alanna Marohnic created this illustration for my article "Mother Demdike: Ancestor of My Heart" in the new "Grandmother Gaia" issue of SageWoman Magazine. However, the magazine felt the image was perhaps too disturbing. Alanna nonetheless wanted to share her artwork with me because she felt so moved by the Pendle Witches' story, she felt it in order for someone to witness what happened to them at the gallows. It is with her kind permission that I reprint the image here.

From my novel Daughters of the Witching Hill:

You'll not find our graves anywhere. God-fearing folk do not bury witches on consecrated ground, or even in the unhallowed plot beyond the churchyard walls where the suicides and unchristened go. After I died in gaol, they burned my corpse, then buried my charred bones on the wild heath overlooking Lancaster Castle. Three months on, they did the same to Alizon, Liza, Jamie, and the rest of them hanged upon that dazzling August day. No crosses mark our resting place, just heather and nesting lapwing. Only our names lingered on and the lies they told about us.

Away in Pendle Forest, Nowell ordered his men to bring down Malkin Tower stone by stone till only the foundation remained. Yet he could never banish me and mine from these parts. This is our home. Ours. We will endure, woven into the land itself, its weft and warp, like the very stones and the streams that cut across the moors.

What is yonder that casts a light so far-shining?

My own dear children hanging from the gallows tree.

Hanging sore by twisted neck,

How they gasp and how they thrash.

Stay shut, hell door.

Let my children arise and come home to me.

Neither stick nor stake has the power to keep thee.

Open the gate wide. Step through the gate. Come, my children. Come home.

[image error]

May justice be served. May ancestral memory be served. May we dream true and have a blessed All Hallows.

Especially in my neck of the woods. I live in Pendle Witch Country, the rugged Pennine landscape surrounding Pendle Hill, once home to twelve individuals arrested for witchcraft in 1612.

Unfortunately Halloween seems to drag out all kinds of ghoulish speculation about historical witches and cunning folk in a way that is not only historically inaccurate but disrespectful to the dead. The Pendle Witches were not ghouls, but real people who were held for months in a lightless dungeon in Lancaster Castle, chained to a ring in the stone floor, before being tried without a barrister, condemned on the testimony of a nine-year-old girl, and then hanged. The historical truth is far more chilling than any fabricated horror story.

So let this All Hallows Tide be not an excuse for macabre speculation but let us light a candle in the memory of those men and women from Pendle Forest who died unjustly:

Elizabeth Southerns, Alizon Device, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Anne Whittle, Anne Redfearn, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, Jane Bulcock, John Bulcock, and Jennet Preston.

The artist Alanna Marohnic created this illustration for my article "Mother Demdike: Ancestor of My Heart" in the new "Grandmother Gaia" issue of SageWoman Magazine. However, the magazine felt the image was perhaps too disturbing. Alanna nonetheless wanted to share her artwork with me because she felt so moved by the Pendle Witches' story, she felt it in order for someone to witness what happened to them at the gallows. It is with her kind permission that I reprint the image here.

From my novel Daughters of the Witching Hill:

You'll not find our graves anywhere. God-fearing folk do not bury witches on consecrated ground, or even in the unhallowed plot beyond the churchyard walls where the suicides and unchristened go. After I died in gaol, they burned my corpse, then buried my charred bones on the wild heath overlooking Lancaster Castle. Three months on, they did the same to Alizon, Liza, Jamie, and the rest of them hanged upon that dazzling August day. No crosses mark our resting place, just heather and nesting lapwing. Only our names lingered on and the lies they told about us.

Away in Pendle Forest, Nowell ordered his men to bring down Malkin Tower stone by stone till only the foundation remained. Yet he could never banish me and mine from these parts. This is our home. Ours. We will endure, woven into the land itself, its weft and warp, like the very stones and the streams that cut across the moors.

What is yonder that casts a light so far-shining?

My own dear children hanging from the gallows tree.

Hanging sore by twisted neck,

How they gasp and how they thrash.

Stay shut, hell door.

Let my children arise and come home to me.

Neither stick nor stake has the power to keep thee.

Open the gate wide. Step through the gate. Come, my children. Come home.

[image error]

May justice be served. May ancestral memory be served. May we dream true and have a blessed All Hallows.

Published on October 31, 2010 12:04

October 26, 2010

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change--Germany: 1560 - 1660

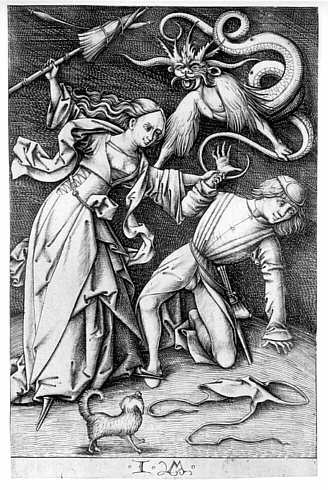

"The Evil Wife" by Israhel van Meckenem, 1440/1445-1503

A woman, encouraged by a demon, beats her husband with her distaff.

PART TWO

By the latter half of the 15th century, the feudal agrarian economy was beginning to crumble, while the capitalist market economy was growing more and more powerful, as did economic competition between men and women. Men active in the market economy tried to further their interests by simultaneously excluding women from many professions and trying to marginalize the domestic economy by claiming that home-produced goods were inferior to shop-produced goods. The guilds also began excluding women. Feeling their livelihood threatened by the competition with wealthy burghers, who set up their own industries and arranged for peasants to manufacture goods for them, male guild members struggled to initiate restrictions for women in the guilds. In 1494 in Cologne, for example, women were driven out of the harness-making guild for the first time. (Rauer 108).

In addition, traditionally "female" professions such as medicine were being taken over by men; male doctors had grown popular among the wealthy classes and were now also making inroads on medical care for the lower classes, and even encroaching on the very traditionally feminine occupation of midwifery (Ehrenreich and English 15-16--please note that the scholarship of this particular text has been called into question). Now we see the beginning of the sexual division of labor: women were beginning to be pushed into the ever-shrinking domestic economy, while men attempted to make the market economy their exclusive domain. This trend not only effected women on a purely economic level, but it also had a profound effect on women's social and sexual status. "The contraction and redefinition of women's productive and domestic roles was consistent with changes in the ideology of sexuality" (Merchant 150).

The Renaissance also ushered in a new ideal of bourgeois womanhood. The domestic sphere of the housewife and mother was idealized by Protestant intellectuals such as Martin Luther. "Gott hat Mann und Frau geschaffen, das Weib zum Mehren mit Kinder tragen; den Mann zum Naehren und Wehren," the Father of the Reformation wrote, advocating strict gender roles. "Im weltlichen politischen Regiment und Handeln antugen sie [Frauen] nichts, dazu sind Maenner geschaffen und geordnet von Gott, nicht die Weiber" (Rauer 112-113). (God created man and woman so that the woman would bear children and that the man would provide and defend. In worldly politics and trade, women should have no part--God created and ordained men for this, not women.) It must, however, be pointed out that Luther's own wife, the ex-nun Katharina von Bora was a very strong woman, beloved by her husband, who addressed her as "Herrin," or "my boss." She took charge of their household finances, farmed, raised and slaughtered livestock, and brewed vast quantities of beer to support Luther and his theology students and keep their household fed. She was the sole woman to take part in Luther's otherwise exclusively male "table talk" discussions.

Despite the positive recognition of woman as wife and mother that took place in the early Reformation, the misogynist ideology of the Catholic Church, such as Thomas Aquinas's contention that women are by nature morally weaker than men, remained in both Catholic and Protestant Churches. Also, Renaissance humanism pushed upper class women into the narrow role of being well-educated but submissive helpmates to their scholarly husbands. In 1499, Konrad Reutinger extolled his wife as the perfect Renaissance woman:

habe ich als Gattin ein Maedchen heimgefuehrt . . . schamhaft, bescheiden, schoen, etwas erfahren in den lateinischen Wissenschaften, die nie von ihren Hausgenossen streit- order schmaehsuechtig gesehen worden ist . . . . Daher weiss ich dem besten und groessten Gott jetzt und in Zukunft Dank, der meinem Studium eine Gefaehrtin und Anhaengerin gegeben hat, die mir aufs innigste vertraut ist. (Ibid 133)

(I've taken a girl home to be my wife [who is] modest, docile, beautiful, with some knowledge of Latin that those in her household have never come to view as overly ambitious or aggressive . . . . For this I thank the best and greatest God now and always, that he has given me for my studies a companion and follower in whom I trust absolutely.)

The Renaissance also saw the birth of a brand new bourgeois motherhood ideal. In the Middle Ages, mothers were expected to take care of their young children, but the mother-child bond was not as glorified to an almost sacred institution and be-all and end-all of a woman's existence as it would become in later centuries. Also, childhood, as we now view it, did not exist then; children were treated as small adults. Children of the lower classes who survived infant hunger and childhood diseases were sent away from their parents as soon as they were old enough to find work as servants in the wealthier estates (Hoher 20).

In the second half of the 15th century, the Catholic Church was losing its authority, under threat by serious challenges and dissent that would soon take the shape of the Reformation. During this divisive time, the Catholic Church expressed a new kind of religious aggression in enforcing morality and a new fascination with the devil. The hedonism that had reigned in medieval plebeian culture was no longer to be benignly overlooked. Wifely obedience in marriage began to be emphasized more and more. During this period, a new genre of literature originated: the Devil Book, which concentrated on explaining how certain activities, such as dancing and drinking, were sinful. The general effect of these publications was to imply that the devil was everywhere (Midelfort 69). The Catholic Church's attitude towards witchcraft also changed quite significantly--the ancient code saying it was sinful to believe in witches was reversed; now Church officials declared it sinful not to believe in them. They argued that a new sect had developed, which even the Fathers of the Church had been unable to foresee (Chamberlin 137). In 1484, Pope Innocent and two German Dominican friars, Kramer and Sprenger, issued a bull against witchcraft in response to rumors of widespread witch activity in Germany. This bull granted the use of inquisitorial techniques in witch hunting. Although the late 15th century was noted for religious intolerance, it was also characterized by a "new carelessness in law" (Ibid 69). The use of torture was revived with the re-establishment of Roman Law. This resulted in a considerable escalation in witch persecutions: "Torture allowed accusations to proliferate to epidemic proportions, because once a witch confessed under torture, she would be tortured again to divulge the names of her neighbors seen at the Sabbat" (Ruether 102). In 1486, Kramer and Sprenger's Malleus Maleficarum was published. This highly misogynistic witch-hunting manual established the belief that women are by nature more prone to witchcraft than men: "Femina comes from Fe [faith] and Minus, since she is ever weaker to hold the faith . . . . Therefore, a wicked woman is by her nature quicker to waver in her faith, and consequently quicker to abjure the faith, which is the root of witchcraft" (Malleus 44). The authors of the book were also obsessed with the idea that the unquenchable carnal lust of women drove them to the devil: "All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which in women is insatiable . . . . Wherefore for the sake of fulfilling their lusts they consort with devils . . . it is sufficiently clear that it is no matter for wonder that there are more women than men infected with the heresy of witchcraft (Ibid 43).

As we have seen, women were beginning to be perceived as a threat to the new economic and religious developments. One cannot imagine that they were at all cooperative with the new infringements on the relative economic and sexual freedom they had enjoyed in the past. They would not submit easily to these changes--they would resist--and their resistance would make them a threat to the interests of the new order. In the arts and media of this period, women were constantly portrayed as domineering, threatening, lustful, violent, and powerful: a force that must be quelled. Village festivals of this period often had floats featuring wives beating their husbands, hurling refuse and rocks at them, and verbally abusing them. Numerous art works of this era, especially the works of Hans Baldung Grien and Albrecht Duerer, depicted the supposed disorder wrought by lusty women. Popular illustrations portrayed women beating their husbands with distaffs. Spinning was one of the occupations with which a woman could still make a decent living. The distaff symbolized her earning power and economic independence from her husband. These male artists interpreted woman's breadwinning power as something threatening, something she abused: her pride of being able to earn undermined her husband's authority. These women were not conforming to the new mold of wifely obedience that Church officials were stressing more and more. Thus, not only were women a threat to their husband's authority, they were also a threat to society in general.

One 1521 engraving by Urs Graf (unfortunately I could not find a jpeg of it to post here) depicts two young women savagely beating a monk who has probably molested them. In the Renaissance, women were portrayed as capable of violence, revenge, and self-defense. Urs Graf's women respect neither male nor religious authority; they assume the right to punish any man who tries to molest them. Hans Baldung Grien's engraving, "Aristotle and Phyllis," below, shows the legendary Phyllis literally making an ass of Aristotle. In all these pictures, women are portrayed as violent, crafty, and insubordinate. Their male victims are portrayed as pathetic, weak-willed fools for allowing themselves to be dominated by women. The message that I read into these art works is that women are trying to hold the upper hand. They will not allow themselves to be forced into the new "proper" feminine sphere. In order for women to be put in their place, men must assert their dominance. Thus, these male artists perceive women as a powerful, chaotic force that needed to be violently subdued. This violence against women would not be long in coming.

"Hercules among the maids of Queen Omphale" by Lucus Cranach the Elder: these women are emasculating the mighty Hercules by dressing him in a women's coif and pressing a distaff into his hand.

"Aristotle and Phyllis" by Hans Baldung Grien, 1513.

Aristotle who proclaimed that the male is superior to the female is shown subjected to Phyllis who literally makes an ass of him.

Published on October 26, 2010 03:28

October 25, 2010

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change

I recently revisited my Senior Paper, written in 1988 at the University of Minnesota. Although some of my sources are *very* dated, most of the actual historical information seems to have stood up to the test of time and, though my focus in this paper was Germany, much of this material seems prescient for what I would later write in DAUGHTERS OF THE WITCHING HILL.

Especially important in my research was the realization that women in the Middle Ages actually had more economic power and independence than they did in the Renaissance and Early Modern Period. I highly recommend Joan Kelly's iconic essay, "Did Women Have a Renaissance?", reprinted in Women, History & Theory: the Essays of Joan Kelly, University of Chicago Press, 1984.

So as an All Hallows offering, I thought I would repost my paper here, in digestible chapters. Keep in mind that I was a college senior when I wrote it, not a PhD candidate, and that I majored in German, so some of my sources are German language. Please note that in the twenty years after I wrote this papar, a lot more scholarship has been done on historical witchcraft studies, and if you are interested in reading more, please refer to the more recent books. I'll try to post a more updated reading list later.

Witch Persecutions, Women, and Social Change: Germany: 1560 - 1660

Part One

The 16th and 17th centuries were one of the bleakest periods for European women. From roughly 1560 to 1660, the witch hysteria claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people, around 75% of whom were women, many of them older women of the lower classes (Ruether 111). One of the worst areas of persecution at this time was Southwest Germany. The question I shall try to answer in this essay is why the witch persecutions often seemed to focus on poor, elderly women. Were these women viewed as a threat to the social order to be violently subdued? What is the historical context for this? How do the persecutions relate to the rise of capitalism, the decline of the domestic economy, the male takeover of tradtionally female professions, the tightening moral and religious strictures, and the peasant rebellions? I will begin to try to answer these questions by tracing the development of the witch burnings over history and the status of women in these different historical periods: from the Middle Ages, when there were very few witch persecutions and women enjoyed relative economic and sexual freedom; to the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, when men and women began to compete in the market economy and women were beginning to be perceived as a threat, and the number of witch persecutions significantly increased; to the last half of the sixteenth and the first half of the seventeenth century, when the mass persecutions took place and women were forced into a far more restricted sphere, ecnomonically and morally, than they had experienced during the medieval period.

Very little witch persecution took place in the medieval period. Although, by the early Middle Ages, most of Europe had been at least nominally Christianized, many old pagan folk ways survived. Such tradtional seasonal festivities such as Walpurgis (May Eve), Fastnacht (the wild festivities that preceded the solemn fast of Lent), harvest homes, and the like often featured much feasting, drinking, and sexual licentiousness. Church officials did not necessarily condone these activities, but the Church, at this point in history, was content to erect a superstructure of Christianity over this rural plebian culture (Ibid 93). To a great extent, the Church looked the other way in cases of lapses in sexual morality, and men and women often did as they pleased. Thus, the customs and behaviors which would later be connected with witchcraft were tolerated and often ignored by the early medieval Church (Ibid 99).

During the Middle Ages, beliefs about what constituted magic and witchcraft slowly evolved. During the early medieval period, the Church viewed witchcraft and magic merely as pagan superstition. In the 8th century, for example, Boniface, the English apostle of Germany, declared that believing in witches was unchristian. In the same century, Emperor Charlesmagne denounced witch burnings as foul remnants of paganism and initiated the death penalty in newly converted Saxony for anyone who committed this sinful act (Trevor-Roper 92). Having firmly established witch persecutions as pagan superstition, the Church maintained a healthy skepticism in regard to the idea of witchcraft (Midelfort 14). In fact, up until the late 15th century, the Church declared it a sin to even believe in witches (Chamberlin 137). Thus, the medieval period until this point was far more "enlightened" in regard to the subject of witchcraft than the next few generations would be. As we shall see, the witch craze was a phenomenon of the Renaissance, Reformation, and early modern period.

The econominc structure of the medieval period until about 1450 was based on the feudal agrarian system, peasant control of production, and a dominant domestic economy. The peasants worked the lord's land and this guaranteed them their livelihood: from the harvest, they took what they needed for survival, while the lord took the surplus. Feudalism necessitated cooperation and interdependence on the part of peasants. For example, the introduction of the heavy plow during Carolingian times made it necessary for the serfs to work together to get a plow and a team of horses or oxen for it. They also decided communally what to plant, where they would plant, which fields to leave fallow, how crops should be rotated, and how the harvest should be divided. Although the landlord benefitted the most from this system, the peasants made the major decisions and controlled production. This subsistence ecnonomy was a domestic economy: almost all the goods necessary for survival were produced by peasant family units in the household (Ketsch 83).

The domestic agrarian economy and culture allowed women relative economic freedom. Work among the lower classes did not have any rigid gender division at the time. Male and female peasants worked alongside each other in the fields. Male and female servants of the same class often did identical work. The only female-specific work was housework, child-rearing, midwifery, and prostitution. In addition, herbal medicine and the crafts of brewing, spinning, and weaving were thought to be more "female" than "male" professions. Among the lower classes, however there was no specifically "male" work. Rigidly defined gender spheres existed only among the feudal nobility: women were responsible for reproduction and household management, while men took over martial responsibilities (Hoher 14).

No rigid gender division was evident in the market economy at this time, however. Men and women participated on a relatively equal basis in the flourishing craft guilds in the imperial cities. In the 13th through 15th centuries, women were admitted to all guilds. Although, in the early Middle Ages, there had been restrictions regarding independent female masters--that is women masters not married or related to male masters--this situation improved in the 13th century. Women began founding their own guilds and taking part on a more equal basis in the mixed guilds (Hoher 15). A document from a yarn making guild in Cologne in the last 14th century, for example, gives detailed regulations specifically regarding female apprentices and female masters: "Welches Maedchen das Garnhandwerk in Koeln lernen will, das soll vier Jahre dienen and nicht weniger . . . . Und sie soll in den vier Jahren nicht mehr als zwei Frauen dienen." (If a girl wants to learn the yarn making craft in Cologne, she must apprentice at least four years . . . . and in these four years, she should serve no more than two women.) This document also outlines the special provisions made for husbands of deceased female masters. Another guild document gives evidence for both male and female masters working in a bath house: "Kein Meister and keine Meisterin soll eines anderen Badegaeste zu sich bitten, bei einer Strafe von halben Pfund." (Rauer 104). (No male master or female master should solicit someone else's bath guest client, on pain of a fine of half a pound.) Women were also quite acrive in selling and trading, especially in materials commonly used in both medicine and folk magic. (Hoher 16).

From the 12th to the mid 15th century, Europe was underpopulated and the workforce needed women. At this time, there was little economic competition between the sexes and the split between the domestic and the market economy had not yet been fully established (Ketsch 117). So, as we have seen, women were relatively economically independent during this period.

There were also viable alternatives to the domestic sphere of marriage and motherhood during the Middle Ages. Convents attracted noblewomen who wished to free themselves from a life of child-rearing and to devote themselves to religion and learning. Beguinages--urban and secular all female communes--motivated women of the lower classes to leave the country for the city. Some women even became vagabond musicians and mercenary soldiers. There were also a few female hermits: single women who lived on the outskirts of towns and forests, and often practiced herbal medicine. These solitary women would later become victims of the witch hysteria in the Renaissance (Boulding 210-211).

The feudal agrarian system was not to last forever. The landlords' tendency to extract from unfree peasants any handy income above subsistence meant that these peansant were unable to give back what they took from the land. Thus, a combination of bad farming techniques leading to soil depletion, steady population growth, and the overtaxation of peasants by land owners all contributed to the gradual breakdown of the feudal agrarian economy and ecosystem (Marchant 47). As the feudal agrarian and domestic economy wanted, the capitalist market economy grew stronger. This had a profound effect on the socio-economic status of women.

During the years 1450 to 1550, very dramatic economic, social, and religious changes took place that would threaten the status and freedom that medieval women had enjoyed. Up until 1450, both sexes were needed in the economy, but afterwards, competition began to take place between the sexes in the market economy. It is during this period that the sexual division of labor, and the separation between the market and the domestic economy began to develop. As men struggled to gain supremacy in the market economy and to push women, their competitors, out of the guilds and into the domestic economy, which was becoming more and more marginalized, women resisted. Women were beginning to be viewed by men as a threat to the order of society. At the same time, a tightening in the moral and religious strictures in both the Catholic and the newly developing Protestant Churches began. The sexual licentiousness, dancing, and drinking that had been commonplace in the medieval period was increasingly frowned upon. Religious authorities grew more obsessed with morality, and the concepts of the devil and witchcraft than they had been before. During this period, the number of witch persecutions rose significantly. The events that took place between 1450 and 1550, thus, were decisive in laying down the foundation for the later witch crazes of 1560 to 1660.

Boulding, Elise. "Familial Constraints on Women's Working Roles," Women and the Politics of Culture, Zak & Moots, eds., Longman Inc., New York, 1983.

Chamberlin, E.R., Everyday Life in Renaissance Times, Pedigree, London, 1965.

Hoher, Friederike. "Hexe, Maria und Hausmutter--zur Geschichte der Weiblichkeit im Spaetmittelalter," Frauen in der Geschichte (Vol. III), Kuhn & Rusen, eds., Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1983.

Ketsch, Peter. Frauen im Mittelalter (Vol. I) Kuhn (ed.), Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1983.

Midelfort, Erik, H. C. Witch Hunting in Southwest Germany 1562-1684: The Social Foundations, Stanford, 1972.

Merchant, Carolyn. The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1979.

Rauer, Brigitte. "Hexenwahn--Frauenverfolgung zur Beginn der Neuzeit," Frauen in der Geschichte (Vol. II), Kuhn & Rusen, (eds.), Paedagogischer Verlag Schwann-Bagel, Dusseldorf, 1982.

Reuther, Rosemary. New Woman/New Earth: Sexist Ideologies and Human Liberation, Seabury Press, New York, 1975.

Trevor-Roper, H.R. The European Witch-Craze of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Harper & Row, New York, 1969.

Published on October 25, 2010 02:08