Mary Sharratt's Blog, page 3

November 8, 2012

ILLUMINATIONS Amazon Reader Review Contest

Dear Hildegard fans,

Writers love to hear feedback on their work.

Post a Reader Review for Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk and send me an email saying you've done so. The writer of the most insightful review will win a free CD of Anonymous 4's The Origin of Fire: Music and Visions of Hildegard von Bingen AND a free bottle of the Hildegard-themed Veriditas Perfume by Arabesque Aromas, made from all natural ingredients:

Contest ends November 20. The winner will be announced shortly thereafter.

If you've already written a review and wish to enter, just send me an email.

Thanks so much for participating!

All good wishes from Mary

Published on November 08, 2012 04:17

October 31, 2012

Blessed All Hallows

Last weekend in England, the clocks fell back. Now the long northern darkness is closing in. People who live in more southerly climes might have a hard time imagining just how DARK it is in the North in this waning end of the year.

Imagine the English gothic novel brought to life as a living reality, everything pitch black at 4:30 on an overcast day.

Today is one of the biggest turning points of the year--All Hallows Eve. Its secular and commercial manifestation with the mass-produced trick or treat paraphenalia cannot hold a candle to the true signficance and gravitas of this ancient feast.

All Hallows has its roots in the Celtic Samhain, which marked the end of the pastoral year and was considered particularly numinous, a time when the faery folk and the spirits of the dead roved abroad. This was a time of inclement weather, when the Wild Hunt, that endless stream of ancestral spirits, raged overhead--something that might feel all too close to home for those who dwell in Hurricane Sandy's path. Even in the digital age, we are still very much at the mercy of the elements and the all too fragile balance of nature.

Many of Samhain's folkways were preserved in the Christian feast of All Hallows, which had developed into a spectacular affair by the late Middle Ages, with church bells ringing all night to comfort the souls believed to be in purgatory. Did this custom have its origin in much older rites of ancestor veneration? This threshold feast opening the season of cold and darkness allowed people to confront their deepest held fears—that of death and what lay beyond. And their deepest longings—reunion with their cherished departed.

After the English Reformation, these old Catholic rites were outlawed, resulting in one of the longest struggles waged by Protestant reformers against any of the traditional ecclesiastical rituals. Lay people stubbornly continued to hold vigils for their dead—a rite that could be performed without a priest and in cover of darkness. Until the early 19th century in the Lancashire parish of Whalley, some families still gathered at midnight upon All Hallows Eve. One person held a large bunch of burning straw on a pitchfork while the others knelt in a circle and prayed for their beloved dead until the flames burned out.

Long after the Reformation, people persisted in giving round oatcakes, called Soul-Mass Cakes to soulers, the poor who went door to door singing Souling Songs as they begged for alms on the Feast of All Souls, November 2. Each cake eaten represented a soul released from purgatory, a mystical communion with the dead.

In Glossographia, published in 1674, Thomas Blount writes:

All Souls Day, November 2d: the custom of Soul Mass cakes, which are a kind of oat cakes, that some of the richer sorts in Lancashire and Herefordshire (among the Papists there) use still to give the poor upon this day; and they, in retribution of their charity, hold themselves obliged to say this old couplet:

God have your soul,

Bones and all.

What do these old traditions mean to us today?

All Hallows is not just a date on the calendar, but the entire tide, or season, in which we celebrate ancestral memory and commemorate our dead. This is also the season of storytelling, of re-membering the past. We honour all those who have gone before us. The veil between the seen and unseen grows thin and we may dream true.

Wishing a blessed All Hallows Tide to all!

Source: Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain

Links:

Soul Cake Recipes

Souling Songs

In 1106, on November 1, the Eve of All Souls, eight-year-old Hildegard von Bingen, a child dedicant to monastic life, endured a searing rite of passage that marked her death to the secular world and her new existence as an oblate-anchorite. (See the video at the top of the page.)

Excerpt from ILLUMINATIONS: A NOVEL OF HILDEGARD VON BINGEN

At dusk on the Eve of All Souls, the rite began.

In our guesthouse chamber, I froze, bare feet on the cold stone floor, as Jutta tugged my earthly garments over my head and let them tumble to the ground.

“You don’t need these anymore, ” she told me.

She wore nothing but a death shroud of sackcloth woven from coarsest, scratchiest goat hair. As goose pimples rose on my naked flesh, Jutta made me raise my arms so that she could fit an identical shroud over my body. The goat hair dug into me, making me want to claw my skin to relieve the itch.

Jutta then bowed her head as low as it could hang and shuffled out of the room, leaving me to shuffle after. We processed to the abbatial church, now alight with tapers, as though a funeral were underway.

At the west end of the church lay a bed of black earth strewn with bare branches and dead leaves. Jutta flung herself belly down in the dirt. Dust to dust. I bridled, my stomach lurching. I remembered the story of Saint Ursula, the 11,000 murdered virgins, the rotting flesh, and then it struck me like a blow, the full weight of what it meant to be an anchorite. The funeral tapers, the bed of earth—this night, I was to die. To be buried with Christ.

Flinging myself toward Mother who watched with the rest of the congregation, I mouthed the words save me. Mother’s face flushed. Weeping in earnest, she stepped toward me while my heart pounded in mad hope. But her gaze left me mute. It was as though she had taken a silken thread and sewed my lips shut so I could only mewl, as weak as a kitten, not sob or wail or rage. Taking my hands, Mother guided me downward, into that dirt.

“It’s God’s will, ” she whispered. “We must all obey those who stand above us.”

With trembling hands, she arranged my prone body till at last I lay corpse-still beside Jutta.

Holy water fell on my back like rain, wetting me through the prickly hair shirt. Incense and the stink of dank earth filled my nose. Finally the archbishop commanded me and Jutta to stand. Numb, my head ringing, I staggered to my feet and chanted the words they told me to chant.

Abbot Adilhum gave me and Jutta burning candles to hold in each hand.

“One for your love of God, ” he said as the hot wax dripped down to sear my fingers. “One for your love of your neighbors.”

I felt no love at all, only shuddering emptiness.

The monks sang Veni creator. At the abbot’s prompting, I mumbled, “Suspice me, Domine.” Receive me, Lord. I placed my candles beside Jutta’s on the altar before hurling myself back into the grave dirt beside Jutta. My ears burned as the monks chanted what even I recognized as the Office of the Dead.

“Rise, my daughters, ” said the archbishop, leading us out of the church and into our tomb, our sepulcher, the narrow cell built onto the edge of the church.

My eyes flooded as he swung his incense thurible round and round. There was only the low doorway and no windows, save for the screen viewing into the church and the revolving hatch where the monks could pass in food to Jutta and me without our even seeing who stood on the outside. Mother and Rorich were already lost to me, outside in the courtyard, chanting along with the monks. I’ll never see their faces again.

“Here I will stay forever, ” Jutta sang. “This is the home I have chosen.”

I choked and coughed as the archbishop sprinkled dust on us. Every part of my body shriveled as he spoke the Rite of Extreme Unction, reserved for those on their deathbed.

“Obey God, ” he told us before leaving our cell.

Tears slid from my eyes as I watched the lay brothers brick up the doorway that Jutta and I had passed through but would never be allowed to leave. As Jutta murmured her prayers, I lay rigid on that cold stone floor as though I were truly a corpse in my crypt.

When the last brick was laid in its place, blocking every hope of escape, Jutta took my hands and pulled me to my feet. In the light of the single taper the monks had left us, I saw her smile.

“My dearest dream has been made real, ” she said.

At that, she blew out the taper, and coffin-darkness enclosed us.

Published on October 31, 2012 08:23

October 7, 2012

Hildegard von Bingen: Doctor of the Church

Hildegard von Bingen: Doctor of the Church and Timeless Visionary

Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179) was a visionary abbess and polymath. She composed an entire corpus of sacred music and wrote nine books on subjects as diverse as theology, cosmology, botany, medicine, linguistics, and human sexuality, a prodigious intellectual outpouring that was unprecedented for a 12th-century woman. Her prophecies earned her the title Sybil of the Rhine.

Pope Benedict XVI canonized Hildegard on May 10, 2012—873 years after her death. Today, October 7, 2012, she will be elevated to Doctor of the Church, a rare and solemn title reserved for theologians who have significantly impacted Church doctrine.

But what does Hildegard mean for a wider secular audience today?

I believe her legacy remains hugely important for contemporary women.

While writing Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen, I kept coming up against the injustice of how women, who are often more devout than men, are condemned to stand at the margins of established religion, even in the 21st century. Women bishops still cause controversy in the Episcopalian Church while the previous Catholic pope, John Paul II, called a moratorium even on the discussion of women priests. Although Pope Benedict XVI is elevating Hildegard to Doctor of the Church, he is suppressing Hildegard’s modern day sisters--the nuns of the Leadership Council of Women Religious, who stand accused of radical feminism.

Modern women have the choice to wash their hands of organized religion altogether. But Hildegard didn’t even get to choose whether to enter monastic life—according to the Vita Sanctae Hildegardis, she was entombed in an anchorage at the age of eight. The Church of her day could not have been more patriarchal and repressive to women. Yet her visions moved her to create a faith that was immanent and life-affirming, one that can inspire us today.

Too often both religion and spirituality have been interpreted by and for men, but when women reveal their spiritual truths, a whole other landscape emerges, one we haven’t seen enough of. Hildegard opens the door to a luminous new world.

The cornerstone of Hildegard’s spirituality was Viriditas, or greening power, her revelation of the animating life force manifest in the natural world that infuses all creation with moisture and vitality. To her, the divine is manifest in every leaf and blade of grass. Just as a ray of sunlight is the sun, Hildegard believed that a flower or a stone is God, though not the whole of God. Creation reveals the face of the invisible creator.

“I, the fiery life of divine essence, am aflame beyond the beauty of the meadows,” the voice of God reveals in Hildegard’s visions, recorded in her book, Liber Divinorum. “I gleam in the waters, and I burn in the sun, moon and stars . . . . I awaken everything to life.”

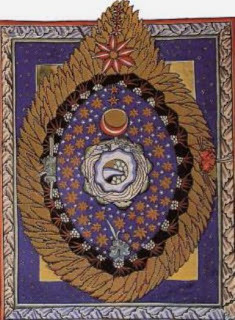

Hildegard’s re-visioning of religion celebrated women and nature, and even perceived God as feminine, as Mother. Her vision of the universe was an egg inside the womb of God.

According to Barbara Newman’s book Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine, Hildegard’s Sapientia, or Divine Wisdom, creates the cosmos by existing within it.

O power of wisdom!

You encompassed the cosmos,

Encircling and embracing all in one living orbit

With your three wings:

One soars on high,

One distills the earth’s essence,

And the third hovers everywhere.

Hildegard von Bingen, O virtus sapientia

Hildegard shows how visionary women might transform the most male-dominated faith traditions from within.

May Hildegard's luminous visions inspire us all.

My novel, Illuminations, based on Hildegard's dramatic life, is published October 9.

Published on October 07, 2012 03:23

October 5, 2012

Blog Tour!

ILLUMINATIONS: The Blog Tour

For those of you who live outside Minnesota and can't attend my Book Tour Events, I shall also be on Blog Tour throughout most of October. Visit my blog tour stops, read articles and interviews about Hildegard, leave a comment, and you could win a free copy of my brand new ILLUMINATIONS: A NOVEL OF HILDEGARD VON BINGEN!

October 9th: Jenn’s Bookshelves

October 10th: The Burton Review

October 12th: Kris Waldherr Blog

October 15 and 16th: Passages to the Past

October 17 and 18: Beyond the Fields We Know

October 19: Gaian Soul Blog

October 22 and 23: Literate Housewife Blog

October 24 and 25: Booking Mama

October 29 and 30: Peeking Between the Pages

November 5 and 6: Devourer of Books

Date tba: Goddess in a Teapot

Published on October 05, 2012 08:08

September 17, 2012

The Feast of Saint Hildegard

September 17 marks the feast day of Saint Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179), the great visionary abbess and polymath.

Long regarded as a saint in her native Germany, she was only canonized in May this year—873 years after her death. In October 2012, she will be elevated to Doctor of the Church, a rare and solemn title reserved for theologians who have significantly impacted Church doctrine.

But what does Hildegard mean for a wider secular audience today?

I believe her legacy remains hugely important for contemporary women.

While writing Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen, I kept coming up against the injustice of how women, who are often more devout than men, are condemned to stand at the margins of established religion, even in the 21st century. Women bishops still cause controversy in the Episcopalian Church while the previous Catholic pope, John Paul II, called a moratorium even on the discussion of women priests. Although Pope Benedict XVI is elevating Hildegard to Doctor of the Church, he is suppressing Hildegard’s contemporaries, the sisters and nuns of the Leadership Council of Women Religious, who stand accused of radical feminism and other doctrinal errors.

Modern women have the choice to wash their hands of organized religion altogether. But Hildegard didn’t even get to choose whether to enter monastic life—she was entombed in an anchorage at the age of eight. The Church of her day could not have been more patriarchal and repressive to women. Yet her visions moved her to create a faith that was immanent and life-affirming, one that can inspire us today.

Too often both religion and spirituality have been interpreted by and for men, but when women reveal their spiritual truths, a whole other landscape emerges, one we haven’t seen enough of. Hildegard opens the door to a luminous new world.

The cornerstone of Hildegard’s spirituality was Viriditas, or greening power, her revelation of the animating life force manifest in the natural world that infuses all creation with moisture and vitality. To her, the divine is manifest in every leaf and blade of grass. Just as a ray of sunlight is the sun, Hildegard believed that a flower or a stone is God, though not the whole of God. Creation reveals the face of the invisible creator.

“I, the fiery life of divine essence, am aflame beyond the beauty of the meadows,” the voice of God reveals in Hildegard’s visions, recorded in her book, Liber Divinorum. “I gleam in the waters, and I burn in the sun, moon and stars . . . . I awaken everything to life.”

Hildegard’s re-visioning of religion celebrated women and nature, and even perceived God as feminine, as Mother. Her vision of the universe was an egg in the womb of God.

According to Barbara Newman’s book Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine, Hildegard’s Sapientia, or Divine Wisdom, creates the cosmos by existing within it.

O power of wisdom!

You encompassed the cosmos,

Encircling and embracing all in one living orbit

With your three wings:

One soars on high,

One distills the earth’s essence,

And the third hovers everywhere.

Hildegard von Bingen, O virtus sapientia

Hildegard shows how visionary women might transform the most male-dominated faith traditions from within.

Published on September 17, 2012 03:26

September 13, 2012

Hildegard and the Feminine Divine

Don't miss the Fall 2012 issue of Namaste Insights, dedicated to Hildegard von Bingen and the Feminine Divine.

In this issue, I interview radical theologian and Hildegard scholar Matthew Fox, whose 1985 nonfiction book, The Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen made Hildegard's life and work accessible to a wide, popular English-speaking audience for the first time. A former Dominican monk, Fox was expelled from his order by Cardinal Ratzinger. Read the interview to hear what Matthew has to say about the irony of Joseph Ratzinger aka Pope Benedict XVI being the one to finally canonize Hildegard and elevate her to Doctor of the Church.

Matthew's new book Hildegard of Bingen: A Saint for Our Times will be published in October, as will my own new title, Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen/.

Published on September 13, 2012 05:40

September 3, 2012

Illuminations Book Tour!

Schedule of events for ILLUMINATIONS: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen (launch date 10/9/2012)

Here are the events already booked. More to be announced!

Tuesday, Oct 9—St. Paul

7:00 pm —Common Good Books launch event: 38 S. Snelling Ave., St. Paul, MN 55105.

Wednesday, Oct 10—Edina

7:00 pm —Barnes & Noble Galleria. 3225 West 69th Street, Edina, MN 55435.

Thursday, Oct 11—Wayzata

7:00 pm — The Bookcase, 607 Lake Street East. Wayzata, MN 55391.

Monday, Oct 15—White Bear Lake

6:30 pm —White Bear Lake Public Library, 4698 Clark Ave., White Bear Lake, MN 55110.

Tuesday, Oct 16—Minneapolis

4:30 pm—University of Minnesota Bookstore, Coffman Union, University Ave.

Tuesday, Oct 16—St. Paul

7:30 pm —Carol Connolly Reading Series, University Club, Summit Ave.

Wednesday, Oct 17—St. Paul

7:00 pm—Subtext Books, 165 Western Ave. N.

Thursday, Oct 18—Mounds View

6:30 pm —Mounds View Public Library, 2576 County Rd 10, Mounds View, MN 55112

Saturday, Oct 20—Stillwater

2:00 pm—Valley Bookseller, 217 Main Street North, Stillwater MN 55082.

Monday, Oct 23—Northfield

7:00 pm—Northfield Library, 210 Washington St., Northfield MN 55057

Wednesday, Oct 24 —Book Club, Golden Valley

7:00 pm —Private event.

Thursday, Oct 25—Podcast: Goddiscussion

9:00 pm Eastern Standard Time

Published on September 03, 2012 07:44

August 19, 2012

In Memory of the Pendle Witches

Here is a copy of the paper I read at the Capturing Witches Conference this weekend at Lancaster University. Academics, writers, and independent researchers from all over the world gathered to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the Lancashire Witch Trials.

This weekend marks the 400th anniversary of the 1612 Pendle Witch Trials. Throughout the region people will be commemorating this solemn occasion. It’s my sincere hope that these events portray the accused witches not as some ghoulish sideshow but as real people who suffered and died unjustly because of other people’s ignorance.

As a novelist, I wanted to devote my work to honouring these people, to raising them from the ashes. I wanted to give voice to the voiceless. An expat writer, I have lived in a number of different countries, but no place has touched me as deeply as the Pendle region in Lancashire, my home for the past ten years.

Evocation of place is my passion. The question I ask myself is what makes this place I’m in now unique, unlike any other place I’ve ever been? What song does the land sing? What stories does it have to tell? What ancestors and elders cry out from the depths of this earth? I am obsessed with local history and regional folklore, how these stories merge with the landscape itself. History is a fluid thing that, together with folklore and myth, continually shapes the present. As contemporary British storyteller Hugh Lupton has said, if you go deep enough into the old tales and can present them in an evocative and meaningful way to a modern audience, you become the living voice in an ancient tradition—the highest aspiration I have for my own writing.

I arrived here knowing next to nothing about the Pendle Witches, but I soon became haunted by the images of witches I saw everywhere. In Pendle, witches are inescapable. They appear on pub signs, beer mats, bumper stickers, the sides of buildings, an entire fleet of double-decker buses. In the beginning I believed these witches on broomsticks belonged to the realm of fairy tale and ghost story. The truth, when I took the time to learn it, was far more disturbing.

In 1612, in one of the most meticulously documented witch trials in English history, seven women and two men from Pendle Forest were hanged as witches, based on testimony given by a nine-year-old girl. In court clerk Thomas Potts’s account of the proceedings, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster, published in 1613, he paid particular attention to the one alleged witch who escaped justice by dying in prison before she could even come to trial. She was Elizabeth Southerns, more commonly known by her nickname, Old Demdike. According to Potts, she was the ringleader, the one who initiated all the others into witchcraft. This is how Potts described her:

She was a very old woman, about the age of Foure-score yeares, and had

been a Witch for fiftie yeares. Shee dwelt in the Forrest of Pendle, a vast

place, fitte for her profession: What shee committed in her time, no man

knows. . . . Shee was a generall agent for the Devill in all these partes: no

man escaped her, or her Furies.

Reading the trial transcripts against the grain, I was amazed at how her strength of character blazed forth in the document written to condemn her. This is the kind of heroine every novelist dreams of creating—except Mother Demdike was better than any fiction. She was real.

I immersed myself in the local studies section of Clitheroe Library and read everything about the Pendle Witches I could get my hands on, including the novels already written about them. Robert O’Neill’s Mist over Pendle is my favorite work of fiction devoted to the Pendle Witch lore and yet, as delightful as O’Neill’s prose is, I was disappointed that he cast Mother Demdike as a sad and pathetic figure when the primary sources seemed to be pointing out that she was much, much more than that!

Then I turned to more recent research in witchcraft studies such as Robert Poole’s The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories and Jonathan Lumby’s The Lancashire Witch-Craze, which drew me into a mysterious lost world, where recusant Catholicism rubbed shoulders with popular folk magic. Emma Wilby’s watershed book Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits helped me decipher Mother Demdike’s testimony in the trial documents, such as her first encounter with her spirit Tibb in the quarry in Goldshaw Booth outside Newchurch in Pendle, and place her firmly in her historical context as a cunning woman. This research allowed me to recast Mother Demdike, so often maligned in fiction and popular culture, as a tragic heroine.

I had to tell Mother Demdike’s story in the first person. It was important to me to give her story back to her, let it unfold from her point of view, allowing her to shine forth like the firebrand she was. I yearned to spin her tale as best I could so my writing could be a mouthpiece for this mighty cunning woman that the authorities had worked so hard to silence. In the course of working on my novel, Daughters of the Witching Hill, Demdike, who I called Bess, became a true presence, a shining light in my life. An ancestor of my heart, if not my blood.

Bess Southerns’s life unfolded almost literally in my backyard. Her essence seemed to arise directly out of the wild Pennine moorland outside my door. Writing about her wasn’t a mere exercise of reading books, then typing sentences into my computer. To do justice to her story, I had to go out into the land—literally walk in her footsteps. Using the Ordinance Survey Map, I located the site of Malkin Tower, once her home. Now only the foundations remain. My horse’s livery yard is near Read Hall, once home to Roger Nowell, the witchfinder and prosecuting magistrate responsible for sending Bess and the other Pendle Witches to their deaths. Every weekend, I walked or rode my chestnut mare down the tracks of Pendle Forest. Quietening myself, I learned to listen, to allow Bess’s voice to well up from the land. Her passion, her tale enveloped me.

As I sought to uncover the bones of Bess’s story, I was drawn into a new world of mystery and magic. It was as though Pendle Hill had opened up like an enchanted mountain to reveal the treasures hidden within. Every stereotype I’d held of historical witches and cunning folk was dashed to pieces.

Once in a place called Malkin Tower, there lived a widow, Bess Southerns, called Demdike. Matriarch of her clan, she lived with her widowed daughter and her three grandchildren. What fascinated me was not that Bess was arrested and imprisoned but that the authorities only turned on her near the end of her long, productive life. She practiced her craft for decades before anybody dared to interfere with her or stand in her way.

Cunning craft—the art of using charms to heal both humans and livestock—appeared to be Bess’s family trade. Their spells, recorded in the trial documents, were Roman Catholic prayer charms—the kind of folk magic that would have flourished before the Reformation. Bess’s charm to cure a bewitched person, quoted in full in the trial transcripts as damning evidence of diabolical sorcery, is, in fact, a moving and poetic depiction of the passion of Christ, as witnessed by the Virgin Mary:

What is yonder that casts a light so farrandly,

Mine owne deare Sonne that’s naild to the Tree.

Bess herself would have been old enough to remember the Old Church, for the English Reformation didn’t really get under way until the reign of Edward VI, Henry VIII’s short-lived son, who came to the throne when Bess was a teenager. She would have remembered the old ways of lighting candles before statues of the saints, of making offerings at holy wells, of processions around the fields to make them fertile—all practices that English Protestants condemned as pagan and un-Christian.

Indeed Bess had the misfortune to live in a time and a place where Catholicism became conflated with witchcraft. Even Reginald Scot, most of the enlightened men of the English Renaissance, thought that the act of transubstantiation, the point in the Catholic mass where it is believed that the host becomes the body and blood of Christ, was an act of sorcery. In 1645, in a pamphlet by Edward Fleetwood entitled A Declaration of a Strange and Wonderfull Monster, describing how a royalist woman in Lancashire supposedly gave birth to a headless baby, Lancashire is described thusly: “No part of England hath so many witches, none fuller of Papists.”

So were Bess and her family at Malkin Tower merely maligned and misunderstood practitioners of Catholic folk magic? The truth seems far more tangled. Bess and her sometimes-friend, sometimes-rival Anne Whittle, aka Chattox, accused each other of using clay figures to curse their enemies. Both women freely confessed, even bragged about their familiar spirits who appeared to them in the guise of beautiful young men—otherworldly lovers. Bess’s spirit was named Tibb, while Chattox’s was called Fancy.

When Bess was in her fifties, walking past the quarry at Goldshaw Booth at sunset—called daylight gate in her dialect—a beautiful young man emerged from the stone pit, his hair golden and shining, his coat half black, half brown. He introduced himself to her as Tibb and promised to be her familiar spirit, her otherworldly companion who would be the power behind her every spell.

Bess is the narrator of the first part of the book. The second part is narrated through the voice of her granddaughter Alizon, a teenager who showed every promise of becoming a cunning woman as mighty as her grandmother. But Alizon is two generations removed from the rich folk magic and the old ways of Mother Demdike’s youth. The child of a sterner Puritan age, she isn’t finding it so easy to come to terms with the legacy her grandmother wants to pass on to her. Will Alizon accept the call of power or will she refuse it? How will her decision effect her family’s fate?

The crimes of which Elizabeth Southerns and her fellow witches were accused dated back years before the trial, but for decades on end, no one dared to meddle with her. But in 1612 that all changed. On March 18, 1612, Alizon had a bitter verbal confrontation with John Law, a pedlar from Halifax in Yorkshire. A few minutes after the young woman told him off, John Law collapsed from a stroke.

Both Alizon and the pedlar were convinced that her anger had struck him lame. Falling to her knees, Alizon burst into tears and begged his forgiveness before fleeing in terror. When witnesses reported Alizon to the authorities, magistrate Roger Nowell wasted no time in arresting her. Possibly through the use of leading questions, he browbeat this young woman into implicating her grandmother and also Chattox, Bess’s rival, and Chattox’s daughter, Anne Redfearne. This was the beginning of the end that saw twelve people from the Pendle region imprisoned in the Well Tower in Lancaster Castle, chained to each other and to an iron ring on the floor.

Not long after her arrest, Bess Southerns died in prison. Ever the wily cunning woman, she cheated the hangman before she could be brought to trial. Her family and friends experienced a different fate.

Alizon, first to be arrested, was the last to be tried at Lancaster in August, 1612. Her final recorded words on the day before she was hanged for witchcraft are a passionate tribute to her grandmother’s power as a healer. Roger Nowell brought John Law, the pedlar she had supposedly lamed, before her. Filled with remorse to see the man’s suffering, she again begged his forgiveness. John Law, perhaps pitying the condemned young woman, replied that if she had the power to lame him, she must also have the power to cure him. Alizon sadly told him that she lacked the powers to do so, but if her grandmother, Old Mother Demdike, had lived, she could and would have healed him and restored him to full health. The following day Alizon and the others were hanged and buried in an unmarked grave.

Long after their demise, Mother Demdike and her fellow witches endure as part of the undying spirit of Pendle. Their legacy is woven into the land itself, its weft and warp, like the stones and the streams that cut across the moors. This is their home, their seat of power, and they shall never be banished. By learning their true history, I have become an adopted daughter of their living landscape, one of many tellers who spin their neverending tale.

From Daughters of the Witching Hill:

Let my children arise and come home to me.

Neither stick nor stake has the power to keep thee.

Open the gate wide. Step through the gate. Come, my children. Come home.

Published on August 19, 2012 04:35

July 8, 2012

Of Witches and Saints: Mother Demdike and Hildegard von Bingen

This summer marks the 400th Anniversary of the 1612 Pendle Witch Trials. In August 1612, seven women and two men from the Pendle region in Lancashire were hanged for witchcraft based on evidence given by a nine-year-old girl. The most notorious of the accused, Elizabeth Southerns alias Old Demdike, escaped the hangman by dying in prison before she could even come to trial. She is the heroine of my novel, Daughters of the Witching Hill.

Throughout the Pendle Region, people will be commemorating this solemn anniversary. It is my sincere hope these events portray Mother Demdike and her fellow accused not as some ghoulish sideshow, but as real people who unjustly suffered and died on account of other people's ignorance and religious intolerance.

I will be taking part in a number of events in remembrance of the Pendle Witches. My schedule is listed below. I wish to draw particular attention to Capturing Witches at Lancaster University, August 17 - 19, a multi-disciplinary academic conference discussing everything from historical witchcraft to Neopagan belief to the horrifying persecution of so-called "child witches" in modern day Nigeria.

This summer has also marked the much belated canonization of 12th century powerfrau, Saint Hildegard von Bingen, the heroine of my forthcoming novel, Illuminations.

Some readers might wonder how I could make the leap from writing about historical witch, Mother Demdike, to Hildegard, a Benedictine abbess. In fact, Hildegard and Demdike had a lot in common. Demdike earned her bread as a healer with her charms and herbal remedies. She was known as a cunning woman, a woman of wisdom. Hildegard, a brilliant polymath and composer,healed with herbs and gemstones. She believed in viriditas, the green and animating life force manifest in the natural world, infusing all creation with moisture and vitality. Demdike was guided by visions of Tibb, her familiar spirit, while Hildegard was called "Sibyl of the Rhine" and revered for her visions and prophecies. Demdike's charms, recorded in the official trial documents, drew on the mystical imagery of the old Catholic Church, outlawed by the Reformation. Hildegard's gemstone remedies seem to draw on sympathetic magic, as seen in her "Sapphire Charm," listed below.

Both women seemed to inhabit a worldview where the boundaries between religion, magic, and visionary experience were fluid. Demdike, a practitioner of Catholic folk magic who also appeared to believe in the so-called Faery Faith that coexisted alongside Christianity for centuries, fell foul of her Puritan magistrate and was condemned as a witch. She died, most likely of hunger and typhoid, while imprisoned in a lightless dungeon, chained to a ring in the floor with the eleven other accused Pendle Witches. The founder of two monasteries, Hildegard would seem to be a pillar of the religious orthodoxy of her day. Yet even she earned the enmity of her archbishop when she refused to disinter a supposed apostate buried in her churchyard. As punishment for her disobedience to male authority, she and her nuns suffered an interdict - or collective excommunication - lifted only a few months before her death. Hildegard might well have died an outcast. And I believe that if Hildegard had lived in Demdike's Puritan England with its abhorrence of mystical experience, she might also have been accused of witchcraft.

Fortunes can change. On October 7, 2012, Hildegard will be elevated to Doctor of the Church, a rare and solemn title given to theologians who have made a significant impact. While such a lofty title will never be attached to Mother Demdike, let's hope that she and the other Pendle Witches might at least be remembered with respect and sad reflection for what they were forced to endure.

Sadly, the Pendle Witch tragedy is as relevant in 2012 as it was in 1612. Witch hunts are still ongoing. Children in West Africa and even the United Kingdom are being tortured and killed.

May we work together to end this injustice. May mystics and visionaries of all faith backgrounds receive recognition and honour. May all witch hunts end forever.

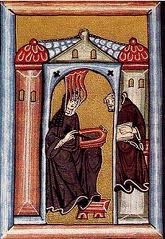

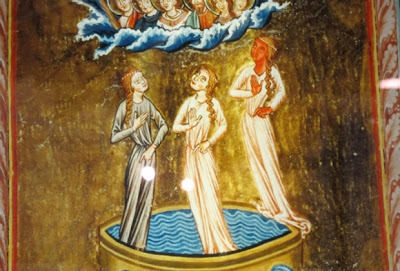

Illustration: Hildegard's vision of the universe as an egg inside the womb of God

Illustration: Hildegard's vision of the universe as an egg inside the womb of GodHildegard's Sapphire Charm to dispel undesired attraction

Sapphire is hot and develops after noontime, when the sun burns ardently and the air is a bit obstructed by its heat. The splendor is not as full as it is when the air is a bit cool. Sapphire is turbid, indeed more fiery than airy or watery. It symbolizes a complete love of wisdom. . . . If the devil should incite a man to love a woman so that, without magic or the invocation of demons, he begins to be insane with love, and if this is an annoyance to the woman, she should pour a bit of wine over a sapphire three times and each time say, "I pour this wine, in its ardent powers, over you; just as God drew off your splendor, wayward angel, so may you draw away from me the lust of this ardent man."

From Hildegard von Bingen's Physica: The Complete English Translation of Her Classic Work on Health and Healing, translated from the Latin by Priscilla Throop, and published by Healing Arts Press.

Published on July 08, 2012 03:56

June 3, 2012

The Illuminating Life of Hildegard von Bingen

My forthcoming title, Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen, will be published on October 9, 2012, and is available for pre-order on Amazon.

Who was Hildegard of Bingen?

Born in the Rhineland in present day Germany, Hildegard (1098-1179) was a visionary abbess and polymath. She composed an entire corpus of sacred music and wrote nine books on subjects as diverse as theology, cosmology, botany, medicine, linguistics, and human sexuality, a prodigious intellectual outpouring that was unprecedented for a 12thcentury woman. Her prophecies earned her the title Sybil of the Rhine. An outspoken critic of political and ecclesiastical corruption, she courted controversy. Late in her life, she and her nuns were the subject of an interdict (a collective excommunication) that was lifted only a few months before her death. Hildegard nearly died an outcast.

In October 2012, 873 years after her death, the Vatican will finally give her the highest recognition for her considerable achievements – she will be canonized and elevated to Doctor of the Church, a rare and solemn title reserved for theologians who have significantly impacted Church doctrine. Presently there are only thirty-three Doctors of the Church, and only three are women (Catherine of Siena, Teresa of Avila, and Therese of Lisieux).

What inspired you to write a novel about this 12th century powerfrau?

For twelve years I lived in Germanywhere Hildegard has long been enshrined as a cultural icon, admired by both secular and spiritual people. In her homeland, Hildegard’s cult as a “popular” saint long predates her official canonization.

I was particularly struck by the pathos of her story. The youngest of ten children, Hildegard was offered to the Church at the age of eight. She reported having luminous visions since earliest childhood, so perhaps her parents didn’t know what else to do with her.

According to Guibert of Gembloux’s Vita Sanctae Hildegardis, she was bricked into an anchorage with her mentor, the fourteen-year-old Jutta von Sponheim, and possibly one other young girl. Guibert describes the anchorage in the bleakest terms, using words like “mausoleum” and “prison,” and writes how these girls died to the world to be buried with Christ. As an adult, Hildegard strongly condemned the practice of offering child oblates to monastic life, but as a child she had absolutely no say in the matter. The anchorage was situated in Disibodenberg, a community of monks. What must it have been like to be among a tiny minority of young girls surrounded by adult men?

Disibodenberg Monastery is now in ruins and it’s impossible to say precisely where the anchorage was, but the suggested location if two suffocatingly narrow rooms built on to the back of the church.

Hildegard spent thirty years interred in her prison, her release only coming with Jutta’s death. What amazed me was how she was able to liberate herself and her sisters from such appalling conditions. At the age of 42, she underwent a dramatic transformation, from a life of silence and submission to answering the divine call to speak and write about her visions she had kept secret all those years.

In the 12thcentury, it was a radical thing for a nun to set quill to paper and write about weighty theological matters. Her abbot panicked and had her examined for heresy. Yet miraculously this “poor weak figure of a woman,” as Hildegard called herself, triumphed against all odds to become one of the greatest voices of her age.

What special challenges did you face in writing about such a complex woman?

Hildegard’s life was so long and eventful, so filled with drama and conflict, tragedy and ecstasy, that it proved mightily difficult to squeeze the essence of her story into a manageable novel. My original draft was forty-thousand words longer than the current book. I also found it quite intimidating to write about such a religious woman. In the end, I found I had to let Hildegard breathe and reveal herself as human.

How did you research this book?

I completed a course on Medieval Studies at Lancaster University. I also read extensively in both English and German while listening to Hildegard’s transcendent music. My research took me to all the locations mentioned in the novel, from the ruins of Disibodenberg Monastery where Hildegard languished in the anchorage, to the site of Rupertsberg, the monastic house she founded for her nuns when life at Disibodenberg had become unbearable. Unfortunately Rupertsberg was completely destroyed in the Thirty Years War, but the location is still very beautiful and inspiring. You can see photos on my blog.

Hildegard’s second monastery at Eibingen endured right up until the secularization in the early 19th century when it was torn down. However, the former convent church remains and is now the Parish Church of Saint Hildegard, where Hildegard’s relics are kept – her heart, her tongue, and her hair. A short distance away is the new Abbey of Saint Hildegard, built in 1900, a flourishing Benedictine community and pilgrimage site where suitably enlightened nuns offer wine tasting (they grow their own vintage) and sell books on planting medicinal herbs by the phases of the moon.

Across the Rhine in the Hildegard Forum, also run by nuns who offer outreach for secular people who want to learn more about Hildegard, particularly her philosophy of holistic healing and nutrition. They manage a café/restaurant; offer seminars and retreats; and maintain an orchard and a medieval-style herb garden.

I also visited Bermersheim, Hildegard’s birthplace. Unfortunately nothing remains of her family home, but there’s a statue of her in the churchyard, high on a hill, with views of lush green vineyards. Not far away is Sponheim, her mentor Jutta’s birthplace, where the ruins of Sponheim Castlestill stand.

If Hildegard has long been venerated as a “popular” saint in Germany, why did it take the Vatican so long to canonize her? Why Hildegard and why now?

The first attempt to canonize Hildegard began in 1233, but failed as over fifty years had passed since her death and most of the witnesses and beneficiaries of her reported miracles were deceased. Her theological writings were deemed too dense and difficult for subsequent generations to understand and soon fell into obscurity, as did her music. According Barbara Newman, Hildegard was remembered mainly as an apocalyptic prophet. But in the age of Enlightenment, prophets and mystics went out of fashion. Hildegard was dismissed as a hysteric and even her authorship of her own work was disputed. Pundits began to suggest her books had been written by a man.

Newman states that Hildegard’s contemporary rehabilitation and resurgence was due mainly to the tireless efforts of the nuns at Saint Hildegard Abbey. In 1956 Marianne Schrader and Adelgundis Führkötter, OSB, published a carefully documented study that proved the authenticity of Hildegard’s authorship. Their research provides the foundation of all subsequent Hildegard scholarship.

In the 1980s, in the wake of a wider women’s spirituality movement, Hildegard’s star rose as seekers from diverse faith backgrounds embraced her as a foremother and role model. The artist Judy Chicago showcased Hildegard at her iconic feminist Dinner Party installation. Medievalists and theologians rediscovered Hildegard’s writings. New recordings of her sacred music hit the popular charts. The radical Dominican monk Matthew Fox adopted Hildegard as the figurehead of his creation-centered spirituality. Fox’s book Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen remains one of the most accessible and popular books on the 12th century visionary. In 2009, German director Margarethe von Trotta made Hildegard the subject of her luminous film, Vision. And all the while, the sisters at Saint Hildegard Abbey were exerting their quiet pressure on Rome to get Hildegard the official endorsement they believed she deserved.

Pope John Paul II, who had canonized more saints than any previous pontiff, steadfastly ignored Hildegard’s burgeoning cult, possibly because he was repelled by her status as a feminist icon. Ironically it is his successor, Benedict XVI, one of the most conservative popes in recent history—who, as Cardinal Ratzinger, defrocked Matthew Fox—is finally giving Hildegard her due. Reportedly Joseph Ratzinger, a German, has long admired Hildegard.

Were Hildegard’s visions caused by migraines?

Neurologist Oliver Sacks believes that Hildegard’s visions and the debilitating chronic illnesses she suffered throughout her life can be attributed to migraines. In Scivias, she describes being bedridden while she received the divine command to write and speak about her visions. Sacks maintains that the symptoms she describes are identical to those of migraine sufferers. He also states that the concentric rings of circles in the illuminations of her visions are reminiscent of a migraine aura.

Critics of this theory will point out that Hildegard, in her medical treatise Causae et Curae, described the migraine in detail but never connected this diagnosis to herself. Moreover she herself did not paint the illuminations that illustrated her visions. So the rings of light could be the illuminator’s stylistic interpretation and nothing to do with any alleged visual hallucinations on Hildegard’s part.

Thus, the “migraine theory” remains speculative. In our hyper-rationalistic age, I think we are too hasty to “diagnose” historical figures with readily-identifiable conditions—ie “Mozart was autistic.” One thing we do know is that Hildegard lived in an age of faith. She and those around her sincerely believed her visions were real. Hildegard wrote an epic trilogy explaining her visions, relating them to the human struggle for redemption, how the fallen world can be reconciled with the created world. Therein lies her genius, not in any catalogue of physical symptoms.

What was going on between Hildegard and the young nun Richardis? Was Hildegard a lesbian?

Hildegard’s passionate letters to and about her protégée Richardis von Stade reveal the abbess at her most human and vulnerable. Alas, it’s far too easy to misinterpret this in an anachronistic light.

In her otherwise gorgeously nuanced film Vision,Margarethe von Trotta portrays Hildegard in the throes of a painful midlife infatuation with a much younger woman. This belies the fact of how

long their relationship endured—Richardis closely supported Hildegard during the ten years it took

her to write Scivias. When Richardis left to be abbess in distant Bassum, Hildegard was heartbroken. Richardis later deeply regretted leaving her.

I don’t believe their relationship was sexual. Since Hildegard made no attempt to hide her love for

Richardis, I don’t believe that she believed their love was in any way shameful. In Surpassing the Love of Men, Lillian Faderman points out that before Freud and Havelock Ellis and our modern theories of sexual orientation, women could be very ardent in expressing their love for each other without experiencing any social condemnation. Think of Emily Dickinson’s deeply romantic letters to Sue Gilbert, who later became her sister-in-law. The Victorians made no attempt to censor these letters. Only in the 20th century did people begin to find them scandalous.

In Hildegard’s own age, the view of sexuality was completely male-oriented. Male homosexuality was punishable by death while the only recorded cases of women being punished for loving other women were in the rare instances where one woman cross-dressed as a man, usurping male identity and male privilege, and under this guise actually married another woman. Otherwise it appeared that nobody really worried about women’s relationships. According to John Boswell’s Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, Anastasius, one of the many popes during Hildegard’s long lifetime, dismissed the one passage in the Bible (Romans 1:26) alluding to women’s same sex relationships, and actually queried whether lesbian relationships were even possible. “Women offer themselves to the men,” Anastasius wrote. An intimate relationship that did not involve men was apparently inconceivable to this pontiff.

What relevance does Hildegard have for us today?

I think that Hildegard’s legacy remains hugely important for contemporary women. While writing this book, I kept coming up against the injustice of how women, who are often more devout than men, are condemned to stand at the margins of established religion, even in the 21stcentury. Women bishops still cause controversy in the Episcopalian Churchwhile the previous Catholic pope, John Paul II, called a moratorium even on the discussion of women priests.

Modern women have the choice to wash their hands of organized religion altogether. But Hildegard didn’t even get to choose whether to enter monastic life—she was thrust into an anchorage at the age of eight. The Church of her day could not have been more patriarchal and repressive to women. Yet her visions moved her to create a faith that was immanent and life-affirming, that can inspire us today.

The cornerstone of Hildegard’s spirituality was Viriditas, or greening power, her revelation of the animating life force manifest in the natural world, infusing all creation with moisture and vitality. To her, the divine was manifest in every leaf and blade of grass. Just as a ray of sunlight is the sun, Hildegard believed that a flower or a stone was God, though not the whole of God. Creation revealed the face of the invisible creator. Hildegard’s re-visioning of religion celebrated women and nature, and even perceived God as feminine, as Mother. Her vision of the universe was an egg in the womb of God.

Hildegard shows how visionary women might transform the most male-dominated faith traditions from within.

But surely Hildegard was no feminist in today’s sense. She was a woman of her time.

Traditionalists will point out that Hildegard was deeply conservative in many respects and will argue that she has been unfairly appropriated by feminists and by New Age spirituality. She never called for women priests, for example. But Hildegard lived in a golden age of monasticism, when an influential abbess could wield considerably more power than the average parish priest.

Kathryn Kerby-Fulton in her essay “Prophet and Reformer: Smoke in the Vineyard,” maintains that although Hildegard’s sacramental theology was orthodox, her reformist thought was radical, as evidenced in her blazing sermon against ecclesiastical corruption which she delivered in Cologne in 1170. If the clergy did not reform and end their abuses, Hildegard preached, the secular princes would rise up against these men, oust them from their offices, and seize their property and wealth. For this reason the Lutheran Church in Germany regards Hildegard not only as a reformer, but as a prophet of the Reformation. Indeed her theology and philosophy are so complex and multi-stranded that her work and life continue to inspire very diverse groups of people, from conservative Catholics to feminist theologians, such as Barbara Newman, whose book Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminineprofoundly influenced me.

Published on June 03, 2012 04:28