Jennifer Freitag's Blog, page 50

April 20, 2011

Spring Special Reminder & Favourite Character List

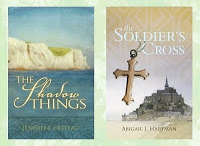

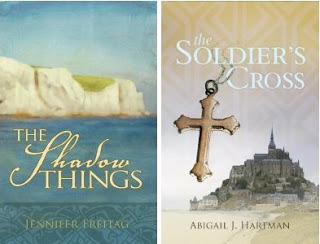

Abigail and I are offering a spring sale on our books The Shadow Things and The Soldier's Cross, from now until April 30. The books will be available for $20 (combined, not each), including shipping, and will also be autographed; if you would like a specific note in each, post a comment with the desired inscription, or email Abigail (jeanne@squeakycleanreviews.com) or me (sprigofbroom293@gmail.com). If you enjoy the books, we would love it if you posted your thoughts in an Amazon review!

Abigail and I are offering a spring sale on our books The Shadow Things and The Soldier's Cross, from now until April 30. The books will be available for $20 (combined, not each), including shipping, and will also be autographed; if you would like a specific note in each, post a comment with the desired inscription, or email Abigail (jeanne@squeakycleanreviews.com) or me (sprigofbroom293@gmail.com). If you enjoy the books, we would love it if you posted your thoughts in an Amazon review!The Shadow Things:

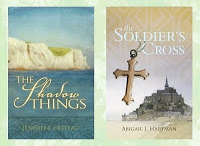

The Legions have left the province of Britain and the Western Roman Empire has dissolved into chaos. With the world plunged into darkness, paganism and superstition are as rampant as ever. In the Down country of southern Britain, young Indi has grown up knowing nothing more than his gods of horses and thunder; so when a man from across the sea comes preaching a single God slain on a cross, Indi must choose between his gods or the one God and face the consequences of his decision.

The Soldier's Cross:

A.D. 1415 - Fiona's world is a carefully built castle in the air, made up of the fancies, wishes, and memories of her childhood. It begins to crumble as she watches her brother march away to join in the English invasion of France. It falls to pieces when he is brought home dead.

Robbed of the one dearest to her and alone in the world, Fiona turns to her brother's silver cross in search of the peace he said it would bring. But when she finds it missing, she swears she will have it and sets out on a journey across the Channel and war-ravaged France to regain it and find the peace it carries.

Multiple Copies April Special $17.50

* * * * * *

By way of entertainment, to myself and others, I drew up a list of my thirty favourite fictional characters, sticking strictly to literature and inserting none of my own. These are figures whom I admire, who amuse me, who have influenced me, who have stuck with me through the monstrous plethora of books I have read and the vast pantheon of characters I have met. Let me introduce you to my friends!

1. Beowulf: One of the toughest guys in legend, and the most God-fearing.

2. Wiglaf: Beowulf's loyal young cousin, the only man who stuck with him to the end.

3. Tiberius Lucius Justinianus: Shy and steadfast, Justin is the most darling of unlikely heroes. But don't tell him I said so.

4. Marcellus Flavius Aquila: A comet-tail hero, a natural leader, frank, open,  self-assured…and Roman.

self-assured…and Roman.

5. Doctor Elwin Ransom: I have difficulty remembering Ransom is a university fellow in light of the wealth of his mind, his actions, his occasional humour, and his mystery. He is so much more than a mere Englishman.

6. Puck: Beneath his jovial persona of your magical creature is a seriously enchanting pulse worthy of Merlin.

7. Eltrap Meridon: A loyal friend, a fantastic fighter, and he's ginger. Enough said.

8. North Wind: I don't have a lot to say about North Wind, because she's not an easy character to know. Nevertheless, her motherly, wild, shape-shifting mystery lends her enough charm to make her one of my favourites.

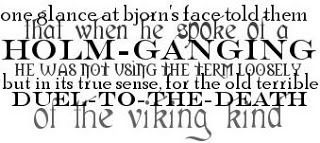

9. Bjorn Bjornson: I like the quiet, potent, clairvoyant types, the ones whose battles are all fought within and never sung about.

10. Bagheera: Halfway up the hill [Mowgli] met Bagheera with the morning dew shining like moonstones on his coat. The sleek black lord of the jungle, wise and mysterious Bagheera, the shadowy genius of Mowgli's story…how could I not love him?

11. Cottia: I relate to Cottia in a lot of ways, in her fierceness, in her smallness, in her fear of being caged and cramped and squeezed into a modern mould which harkens of none of her wild earthy ties.

12. Aslan: This character has always brought to the forefront of my awareness the knowledge that God's splendour and majesty, his loving-kindness, his justice and his mercy is deeper and more wild than I could ever imagine.

13. Puddleglum: Optimistic though dour, Puddleglum is the bedrock of The Silver Chair.

14. Tirian: Despite his rashness, despite the overwhelming odds of defeat, the last king of Narnia remains faithful to the true Aslan to the end—and beyond.

15. Jewel: You can't have Tirian without Jewel. As with electrum, Jewel is the silver to Tirian's gold.

16. Jill Pole: While I can't say I necessarily share personality traits with Jill, I've always related to her and she has always had a special place in my heart. And I've always wanted to know how to shoot a bow.

17. Tyr: I've always liked the one-handed holm-ganging god, and the fact that he got off rather lightly in Loki's taunting.

18. Bilbo Baggins: Probably your most unlikely hero of all time, this diminutive character grows to a shining light in Tolkien's story and quite possibly tops the hero on whose story his is styled.

19. Eowyn: Tolkien's tribute to the proud ancient Norse woman, Eowyn's backbone and tender heart are fantastic to read about.

20. Jonas Faulkner: Despite his mysterious past and scars, Jonas presents to the world a dashing, smiling image, a touch of seriousness coupled with a gushing child-like attitude. And I have a thing for skinny, convivial Victorian gentlemen.

21. Screwtape: This most logical if not always valid villain has intrigued me for years. His attitude of a schoolmaster (occasionally longing to give his pupil a good shaking)—blunt and reasonable—cuts through the tangled web of ethical conundrums to get at the heart of the wickedness that plagues us from day to day.

22. Aunt Honoria: As good as a man with a penchant for makeup. Aunt Honoria's worth is as hard to pinpoint as a single beam is on the face of the sun: she is permeated with stalwart nature and a tender if practical disposition.

23. Lady Talarrie: Resourceful, loving, magical, a woman for all seasons… I am not sure I have met a mother in a story to match this one.

24. Elizabeth Bennet: Elfin, intelligent, sure of her own mind to the point of being prejudiced, I can see a lot of myself in this famous heroine (some of the good bits and a lot of the bad). Her wit and charm filled me with endless delight as I read her story.

25. Emma Woodhouse: Spoiled but well-meaning, precocious and naïve, as with Elizabeth Bennent, Emma and I share an alarming amount of traits.

26. Mr Darcy: The pride of Pride and Prejudice. Mr Darcy cuts a straight-laced, unforgiving figure on the Georgian scene. He gives the motionless but masculine image of Greco-Roman statuary a potent life (and a better wardrobe) which I find fantastic.

27. Mr Knightley: A gentleman among gentlemen, I have the good fortune of knowing a man much like Mr Knightley: witty, intelligent, tender-hearted, a stalwart figure in the midst of a whirling, silly world.

28. Lena: Lena's tremendous physical power and presence is only half of why I love her. Beneath her hideous exterior beats a loving and repentant heart. And rushing out with all the noise of a shadow to bite a bad guy's leg in two is kind of awesome.

29. Gummy: It came to my attention after another reading of The Gammage Cup that Gummy, albeit much more jolly, is a lot like my own dearly beloved character of my own invention. Sunny-hearted with a backbone of iron, that's Gummy. Couldn't do without him.

30. Loki: Eh, not the most endearing character, but he makes the sort of villain you can really hate: shake-you-down-to-the-roots-of-your-soul hate. For some reason I've always liked that smooth, insidious, conniving villain. He's taught me a thing or two, Loki has. But he's a little tied up right now.

April 19, 2011

Beautiful People - Adamant

Sky and Georgianna Penn have begun a fun exercise in introducing people to characters by posting a list of questions for blogging authors to answer every month.

Sky and Georgianna Penn have begun a fun exercise in introducing people to characters by posting a list of questions for blogging authors to answer every month.Once a month Sky and I will be posting a list of 10 questions for you to answer about your characters. You can use the same character every month, or choose a new one for each set of questions. Your call. You can answer all the questions, just one, or however many you have the time and energy to answer. Just go for it and have fun.

Because I missed March I'll go ahead and post March's questions too, to introduce my character. And because I like answering questions. I will do Adamant from my novel Adamantine, because Rhodri has been getting far too much attention recently.

Adamant

1. What is your characters full name?

Miss Adamant Firethorne

2. Does his/her name have a special meaning?

Only in the sense of dramatic irony.

3. Does your character have a methodical or disorganized personality?

Adamant tries hard to be methodical, and she is, in general, a very tidy girl. She is most tidy when she is being tidy for other people.

4. Does he/she think inside themselves more than they talk out loud to their friends? (more importantly, does he/she actually have friends?)

The term 'friends' must be used loosely. She has companions, and she does talk to them, but she is not above conversing with herself, even out loud.

5. Is there something he/she is afraid of?

Failure. Too much hangs on her success for her to fail, but she is still terrified of doing so.

6. Does he/she write, dream, dance, sing, or photograph?

Adamant is quite a dreamer, but she is sensible enough of society to keep it to herself. She is a passable dancer and moderate singer, but she does not often have occasion or desire to excel in either.

7. What is his/her favorite book? (or genre of book)

Adamant is an eclectic reader. She is very fond of the works of the contemporary author Charles Dickens, even though she finds her spirit often depressed by him. She has acquired an interest in the ancient sagas, but unfortunately such stories are hard to come by. (I believe Puck had a thing or two to say about that.)

8. Who is his/her favorite author and/or someone that inspires him/her?

Adamant's favourite author at present is Charles Dickens, whose works, unfortunately, do not reflect her own life and poorly prepare her for what is required of her in Faerie. This is what comes of reading too much contemporary fiction.

9. Favorite flavor of ice cream?

Adamant has only had ice cream twice in her life, and both times it was raspberry ice cream with a side of lemonade. She is fond of the taste, but not very fond of the extreme coldness of the dish.

10. Favorite season of the year?

Spring, summer, and autumn, but not winter. She enjoys the transitional phases of spring and autumn and the full bloom of summer, but she dislikes the drab aspect of winter, especially coming from London as she does.

11. How old is he/she?

Adamant is seventeen going on eighteen.

12. What does he/she do in his/her spare time.

Being of a wealthy middle-class family, Adamant has plenty of spare time, and spends it most often reading or gardening, or pretending to practice her harp. She is not a bad hand at sewing, though she dislikes the monotony of it.

13. Is he/she see the big picture, or live in the moment?

Adamant tends to live in her own world adjacent to reality and, when returning to reality, has often to sort the bigger picture back out of her immediate emotions.

14. Is he/she a perfectionist?

Not really. As I said before, she is a tidy girl and likes order, but she is not obsessed with it.

15. What does his/her handwriting look like? (round, slanted, curly, skinny, sloppy, neat, decorative, etc)

Adamant possesses a very handsome hand—her mother made sure of that—but unfortunately she does not have anyone to write to.

16. Favorite animal?

Adamant is very partial to cats.

17. Does he/she have any pets?

She has a sort of gargoyle which seems to exhibit a distinctly canine set of traits.

18. Does he/she have any siblings, how many, and where does he/she fit in?

Adamant has no siblings and is an orphan; however, she does have three female cousins, none of which really likes her.

19. Does he/she have a "life verse" and if so what is it?

She does not really have a 'life verse,' for there are verses applicable to all walks and moments of life. If she had to choose one, it would most likely be Psalm 28:7: "The Lord is my strength and my shield; my heart trusted in him, and I am helped: therefore my heart greatly rejoiceth; and with my song will I praise him."

20. Favorite writing utensil?

She does not have a favourite writing utensil. If it does not bleed, does not break, does not overly smudge, and does not keep getting lost, it is an admirable writing utensil.April 13, 2011

A Somewhat Sure Thing

* * * * * *

From the crest of the hill one was afforded a fine view of the surrounding countryside. Our down country is good for views, if you take a liking to views; it is good for other things: sheep, mostly, and cows, and plenty of wheat and corn, and the barley used to make small beer, which is a staple among working folk like myself. From the crest of the hill you could see clear down to the Silver—a thick, winding band of iron-grey to the south—and the low farms between the upland masses shrouded in eerie mists, their boundaries marked out by the dark furring of wood that made a patchwork of the landscape.

A fine view, but I didn't have time nor luxury to turn about and see it. I swung up the hill with the accustomed hillman's stride, a squared-off hunk of rock nestled in the grip of my arms. They used horses and carts for this sort of work, most days, but Quince had gone lame in the hoof and Cobweb had unaccountably got a foal, and after a quarter-hour's listening to the grumbling of the work masters this morning I'd stepped forward with my two big arms and volunteered to put the work forward at least a little by lugging stone myself.

'Twas the earthworks we were building to terrace the downs. Downland soil is mostly chalksome, but you can grow good beech-woods and the land makes for excellent pasturage. So we were terracing some of the hills, keeping the hill back from sliding into the farmland below and levelling the turf out above.

I was headed for the earthworks, the last load until after the dinner hour in my arms, and I was eager to finish. My belly was plastered flat against my backbone, and gurgled every step or so to remind me that it was empty. I'm usually a peaceable soul, now, so long as I'm left to myself and no one takes it into his head to make trouble for me, but when I'm hungry I get a little temperamental. So when I came up to the crest of the hill where one could see the earthworks round the bend of the track and westward, and found a fairy standing stock in my path with his back to me, I flared. The rock was heavy and I was hungry.

" 'Moutta the way!" I barked. "Dun stand there gaupin'! I've work to do!"

There was a momentary pause. I wondered if the fairy had even heard me; mayhap he was deaf. But no, after a short space of time he turned unhurriedly around toward me. He had the hood of his slicker cast up, for it was a mucky, mizzling day with cold gusty winds blowing the soft rain all across the hillsides; as he turned, one such gust caught the hollow of his hood and blew it back from his face.

I felt the blood turn to ice in my veins.

I'm sure a boy has had nighttime dreams about meeting someone who turned out to have a hideous face, or no face at all. Such was the sensation which rushed giddily through my brain at that moment, though I'm full man-grown and counted something steady in the brain-pan, all told, when I came face to face with that little fairy. I'd never seen him before in my life, but I didn't have to. I knew enough to be sensible of my own grave error.

The Duke's face weren't hideous. Far from it, despite his little size he was possessed of a fine face, a gentleman's face, as if some artisan had carved it out custom-made for him. He regarded me with a mild expression, almost as if he were bemused, with a touch of absentminded bitterness about the mouth, though in the eyes he narrowed against the mizzle I thought I caught something like white laughter.

"I beg your pardon, my good fairy," he said in perfectly cultured tones. "I fear I am in your way." He nodded and took an equally unhurried step back.

I weren't conscious until that moment of standing absolutely still, like a rabbit which sees the fox. I was so mithered that I couldn't even begin to think to apologize, a fact which rears itself up in my memory time and again to make me blush with shame. But I don't honestly know what I could have said to that mild, bemused, mocking face.

I was saved—if I can call it saved—from a stammering conversation by a hailing behind me. The Duke glanced aside and I swung round to see a big bronze-and-brown Catti striding bold as you please up the hill toward us. You can't go long without spotting one of those figures, wearing their fine eerie elegance about them like kings, the lot of 'em, though any one of them may be merely freed from labour at trenches, and the son of a pig-drover before that. Nevertheless they are formidable folk, the Catti, and I'd keep my peace about them in the best of times.

The Catti came up to us, shook his arm loose of his wadmal cloak, and held up his paw, pads outward. "Lurld Duke," he said thickly.

"Lefe-Rogn," said the Duke, still in that mild tone of voice, raising his own hand in a returning gesture.

Lefe-Rogn the Catti dropped his arm, pulled the cloak shut as a gust of wind boomed round us, and began at once in his own thick, unintelligible language to tell the Duke something which I took was of some importance. Halfway through his discourse he removed a packet of lettering from his cloak and passed it over to the little fairy, who took it with a brief shadow clutching at the space between his brows. Never did his eyes leave Lefe-Rogn's face. He interjected now and then, and 'twas startling to hear the brogue come suddenly into his smooth tones as he returned language for language. Standing a little apart from the two, looking on—I'd forgot all about the rock in my arms and the emptiness in my belly—I was minded again of someone telling me, "It's like speakin' with gravel an' plums in yer mouth, that Cattee garble." Sure, an' maybe it was, but watching the Catti speak I saw that same curious elegance, and hearing the Duke I thought he gave to that tongue of gravel and plums a kind of wild gentleness, as if the whole language were a sort of speaking chant.

I was watching his face, too, as the Catti spoke. That white mocking laughter had vanished from the eyes almost upon the instant, and the shadow which his puckered brows made gave his nose a fierce aspect, hooked as an eagle's; it seemed for a moment he had given his profile back to the artistic stoneworker, for it was fixed and rigid, very sharp. Then—

You mind how a ray of light flushes on the yard of a spring morning, the first spring morning, and you see there's been crocuses blooming overnight? That's how it was as the Catti Lefe-Rogn began to end his talk. Something in the Duke's face unwound, and something relaxed, and there was only the way he bent his head and looked up 'neath his brows to cast a shadow on his countenance. Lefe-Rogn finished, and the Duke's gaze wandered a little between the two of us, fixed upon some point in the mizzling, misty middle distance. I could not read his face; Lefe-Rogn remained silent. But I know I felt a kind of thrill when the white mocking laughter flamed in the fairy's eyes once more.

"Fro gunen linn," he murmured, half to himself. Then, still more in that speaking chant,

Tirasbornsikka shobrou ninë.

And Lefe-Rogn grunted appreciatively.

The Duke seemed to wake from whatever far-off dream his thoughts had taken him and he shook himself, scattering beads of water everywhere. With a definite motion he flung the hood back over his head, obscuring the silvery-blue of his hair, and he stepped forward with a little including gesture toward the Catti, indicating that they walk back down the road together.

But as he passed me, he stopped, and I knew then that he had never forgot I was standing there. His gaze met mine, lifted a little for I'm a big fairy, narrowed against the blowing rain. There was that laughter, flaming white, laughing at me out of his eyes. "I wish you well at your work, sir," he said, and with a nod that was all. He was gone off with the Catti Lefe-Rogn back down the hillside, and I stood for long watching them rather dazed and moonstruck-like, listening to his words in my ears and hating myself for not being able to reply.

But I'd have time to do him a good turn soon and, though I'm sure he never saw it so that there was any score between us to settle, I think the balance is laid to rights.

'Twas the first I'd met him, but not the last I'd see of him that day. I finished my work, still a bit dazed, and made my way back to the work camp at the foot of the down. The mizzle had turned to real rain by then, and I had the full weight of it back of me as I descended the hillside and wound my familiar way toward the mess booth from which wafted the scents of supper. Small beer, like as not: hot porridgy stuff which stuck to your ribs, maybe some mutton if I was lucky, potatoes and carrots pan-seared and peppered. As I drew closer, I could hear Emer the mason whistling fair through the broken place in his teeth and, though I was hungry, I was suddenly aware that I didn't much care for company. I hesitated outside the booth until the scents and my own hunger drove me inside.

I could see Emer in the gloom—you can pick his saffron gash of wings out in a sea fog—cheerily whistling and breaking off the whistling now and then to put away a mouthful of potatoes; round him thronged the rest, familiar folk, downlanders mostly, all doing the work 'cause it's their own ditch and den, this country. I knew them by name, and the names I didn't know, I knew their faces. Yet they seemed to well out at me, press at me, and I didn't want to have anything to do with them. Marshlight fancies, I reckon—the mist had got between my ears. But something about the Duke, how detached and serene he had been, was more downlandish to me at that moment than the joyful crowding company of the farming fairies before me. I wanted naught to do with them just then, and I wanted to be with my own thoughts to sort them out. Funny odd thing, how a chap can know there's something in the wind, maybe before that wind has even blown.

Somehow I got myself some food, small beer and carrots, and beef—there weren't any mutton and the potatoes had all been took. No one paid me any mind as I made my way back outside the booth into the rushing face of the rain. I found a sheltered place under the lipped eave of the wagon-shed and perched there by my lonesome on an upturned barrow, straddle-legged with the platter of food between my knees. The rain came between me and the camp scene of times, gusting wildly in silver sheets back and forth, and all the while the lonesome wind creaking in the boughs of the wayfaring tree which grew nearby. Lights peeped back at me out of the mists from the farmsteading down the way and from the horn panes of the mess booth windows. They make a chap lonely, looking back out of the mists at little lights like that; but at that moment, I didn't mind the lonesomeness. Mayhap he didn't mind, either, the Duke. I had never got it in my head before that a fairy of such wealth and high standing could want a bit of lonesomeness for himself, but just then I thought I understood. Sometimes rainsome downland is just the sort of companion a soul needs.

I ate my carrots and beef after they were cold, and my porridgy mess as it was going cold too. I had neglected to bring any drink with me; the small beer was a trifle too thick for that. I sighed and got to my feet, but just as I did so I heard the light swift tramp of boots on the turf and out of curiosity I looked up to see a very young fairy coming through the mists, looking this way and that as if for something in particular. He was in his shirtsleeves, as I was, with a fine blue plaid vest, not as I was, and new galoshes with fresh mud-spatters on them. I waited patiently while the lad picked his way among the waiting stacks of stone and tools, trekking through several of the worst puddles a'purpose. He caught sight of me at last, as I'd always suspected he would, and he came at once toward me, smiling in a friendly way. His cap obscured his hair, but he sported a rain-streaked pair of blue wings, so that I was not very surprised when he came up to me and thrust out his hand, saying,

"Salutations, sir. My father bids me...convey to you how much he would appreciate your presence at Godolfin Stead. For tea," he added, smiling through his freckles and the rain on his cheeks.

I took the lad's little hand—little, but rough already—and shook it, pleased to discover he had a splendid shake back. "I'll come 'long now with you," I said.

We walked back together through the gusting rain, through the working camp to the gap in the intake and the road beyond. There was no verge to walk, for the road was bordered on either side thickly by gorse-shrub, the yellow flowers winking through the rain at us as the far-off lights of Godolfin Stead winked yellow in the mists. There was no verge, so by the time the two of us had come down the road to the gate of the steading our boots were covered in mud. The lad seemed not to be minding, and ordinarily I would not be minding much myself, but I felt in this instance I could not simply strike off my boots at the door and walk in with only my stockings on.

'Twas the first time I had been within Godolfin Stead. I've seen it from the hillside, a great rambling place, recently reclaimed from dereliction by the Duke himself. The two of us went in by way of the cobbled yard, round by way of the horses' stables and through the short picket-fenced garden to the long low jut of room which was still a bit raw with newness. It was dim inside, and smelt of damp and a little of moss. The lad thrust both feet in a trough which ran along one side of the room and yanked away at a faucet until the water spurted and gushed over his leathers, washing the mud away. I followed suit while he wordlessly manned the faucet for me, and so I was saved from having to walk in to tea in only my stockings.

It hadn't struck me until then that it was tea I was going to have. I hadn't thought for a moment that those mocking eyes meant to give me a lashing for my insolent tongue, but tea... That was something altogether different. In my grimed work clothes and rough Kartuscan brogue I felt out of place, no matter that my boots were shiny. What could he want with me? Surely it would not merely be tea.

The boy stood at the inner doorway, his hand on the latch while the light from within spilled out round him golden and inviting. He had his head up and turned a little, faintly and, I think, unconsciously supercilious. I struck the most of the water off my boots and joined him at the doorway.

"After you, young moster," I said.

He led the way into the farmhouse kitchen. I didn't mind being brought in by the servants' wing. If it had been anyone else, I think I might have, for I'm a free-born fairy, native to the countryside, even if I don't have a piece of land to my name. Nah, but I didn't mind for that fairy, who was asking me to tea and understood the companionable lonesomeness of our Kartuscan downs.

"Aie!" said one of the maids, scoldingly, as we walked through. She dusted her hands off fiercely on her apron and began striding toward us round the end of the great middle table. "Take iff that cap," she demanded. "And see you dry it iff at the stove." But she was a fine girl, and didn't strike in that most annoying way maids can have at the young master's clothing in an attempt to tidy him. She watched with eyes snapping in her freckled, flushed face as the boy slung off his hat, revealing a head of bright blue hair, and hitched it up over a hook by the stove.

"There," he said, turning back on the maid as the Duke had turned back on me. "Is it pleasing to you now, Lark?"

"You're as saucy as your father. Mind the hat in the future. Children these days!" she sighed, exasperated-like, as she whirled round to the counter. "An' him in gov'ment!"

The mocking white laughter which I was coming to know was in the boy's eyes as he beckoned me to follow once more. We left the kitchen and went down a narrow passage to the long, massive, ancient centre of the old steading which had in days agone been kitchen, greeting room, mess hall, and bedroom before any of the other wings had been built on as the farm had prospered. It was well furnished now, reclaimed in comfort though its rafters still sported the blackness of fires over generations; down the middle of the room was a raised hearth after the old fashion, its ends balanced with one desk and one piano. The desk was a massive piece of work, complete wood and scrolled all over with designs I'd have to get down on my knees to observe. I'm not much a fairy inclined to think highly of music, but I thought well of that piano. There was a maiden like a candle's flame perched on its bench with a bit of sewing in her lap. She could not have been over twelve, not old enough yet to 'come out,' as those social folk say, but she gave me back such a frank and welcoming look from 'neath her unbraided ginger hair that for a moment I thought I was looking at the mother.

But I weren't looking at the mother, and the boy was saying, "Here he is, sir," and I had to turn back to the desk.

The Duke looked up at once from whatever he was writing, a surpriseless geniality in his face. With a deft hand he turned the paper over and folded it with the side of his thumb—a firm, sharp edge—though it mattered naught 'cause I can't read. "Thank you, Roman," he told the boy. He got up and held out a hand to me.

I dragged my own cap off my head and stepped forward to take his handshake. The hand he held out to me was long and fine, unlike my blunt workman's paw: but I noticed he had a firm grip and, what's more, the light caught his wrist and showed up the fierce silver gash of a scar. " 'M Ironside," I said, finding my tongue at last. "Ghyll Ironside."

Recognition glinted in his eyes. "The Ironside ghyll—were you born near the place?" His tone was one of friendly interest.

I released his hand, taking the step back with my cap crushed in my fist. I couldn't remember anyone recognizing the place, as 'twas only a little gash of wooded land round the corner of nowhere and up a long scrubby walk of forsaken countryside. Them as did know were kind enough to let it pass; them as didn't made jesting remark on the uniqueness of my name, and that would be all. But the Duke unexpectedly and uncomfortably knew the place. "Aye, sir... S'matter of fact, I was born right there, sir. Named after it."

I saw the shadow of understanding dart across his face. But almost on the instant it was gone again, and the Duke was gesturing toward a half circle of couches set up alongside the hearth. I took the gesture and made for them, hoping my backside weren't as grimy as my front side. I noted that the Duke walked with a bit of a limp. I couldn't recall hearing of him being in any war, though I'd heard snatches of him being on the frontier when the Black Catti tribe had erupted against the garrisons. But that was...nah, I hadn't been paying attention, and I don't know how long ago that was. Some thirteen year or more. Mayhap he'd had a riding accident.

I eased myself with care onto the horsehair couch while the Duke, seating himself and crossing one leg over the other, turned to the boy and said, "Would you make sure Lark knows to bring the tea in? I'm sure she's busy with supper."

The girl at the piano put aside her sewing, rising. "I'll see to it."

"Thank you, my pet," said the Duke.

The girl went off, and the boy Roman sat down on the kerb of the hearth to listen to us talk. "I heard the two horses had been compromised," the Duke began. "Hopefully the one will recover soon, and I'm sure it will be little trouble to procure another to take the mare's place. Still, it puts the work back a bit. Do you think we will be done by autumn ploughing?"

I hadn't expected him to ask my opinion. Figures and speculations have never been my strong point, neither. I took a moment to think. "I reckon so, sir. It's not work we're unused to, and we've all got a mind to work at it. I think we could do it even without the horses, though they make it easier. A gelding would be best," I ventured to add.

"Mm, yes." The Duke nodded thoughtfully, gazing aside into the fire with a pensive expression. "I think I know a fellow who can lend us a beast. I may have you pick him up on your way back."

I blinked, surprised. "My way back—sir?"

The gaze darted up to me from under the brows, the firelight still caught in the blue, and the white of mockery flickering 'neath it. "I have a job for you, Mr Ironside, if you are interested in it."

I think a fairy might be suspicious, hearing a proposition started such a way. I might have said, "See here, I know you're in gov'ment. What's this all about, and is it honourable?" But I didn't. Looking back into that mocking, friendly face, I reckoned then without thinking about it much that I'd do anything and more for that fellow. He's that sort of fairy.

"If you reckon me a fit fairy for the job, sir," I replied, "I'll do aught you want me to."

I could see he was remembering my ungracious words on the hillside that late morning, and he was laughing at me now. But he didn't say a word about that. All he said was, shifting a little in his seat, "Ah, here comes Aventine with the tea," and the maid who reminded me of a candle's flame came in on silent feet, bearing a tea-tray in her arms. Roman, whom I took to be her brother, didn't stir a finger to help her, but looked on with that little condescending smile of his, though he couldn't abeen more than nine at the most, while she placed the tray between us, arranged her skirts, and began to serve us. I weren't accustomed to being served, but I let her do it, wishing all the while the teacups weren't so tender and small. I feared I might break 'em.

"Do you take cream, sir?" she inquired of me.

By the uncanny rowan, she had long lashes. "Aye, but nay sugar."

She put in a great dollop of wholesome cream, whisked it round, and passed it up to me. Her father took his tea black. When she had finished, she rose and retired to her bench again.

The Duke leaned back in his sofa, cradling the teacup in his hands while the steam danced writhing and doubling over between his face and me. "The game's afoot," he said gallantly. "We may be on the brink of an unprecedented peace with the Black Catti if what was agreed to a week ago," he gestured toward his desk and the packet of paper I could see still folded there, "holds true at this hour. But the Catti are a volatile people, the Black especially, and it may be long and long before the stitches we have put in this wound are strong enough to bear any sort of strain without bursting apart and bleeding again. So we must play this quietly and let no word of this slip out until it is a somewhat sure thing."

I was puzzled. He paused to take a sip of his tea and I stared at him, bemused-like, my own teacup held in my hands as if I held a new-hatched chick—a very warm new-hatched chick. Once more he seemed gone away into his own thoughts. The room was full of the tinselly rustle of the fire and the dusky rush of rain overhead. I prompted presently, "An' how can I be of help to you, sir?"

He surfaced slowly from his musing. Gesturing toward me with his teacup, he explained. "It is very simple. I have a friend who spent much of his soldiering years on the frontier working to make this peace come about, and now that he is retired I think he would appreciate being one of the first to catch the wind of what we are making."

I cut my gaze aside toward the desk. "An' that paper—you want that I should take it to him?"

The white laughter glittered at me. "Not as easy as that. I want you to recall the words I have told you here, now, and tell them to him."

I suppose I hadn't understood the gravity of the situation until he put it that way. I still didn't, to be honest. But a message too important to be passed by paper, that I could understand. I suddenly hadn't much stomach for the tea. A peace, a peace with the Black Catti... We'd had a tenuous trade relationship with the Dunr Catti for as long as I've been alive, a sort of uneasy, hackled dance, but never had we any peace with the Black Catti, no peace in any shape or form. If they should be spooked, God alone knew how many years of work would be in an instant destroyed, and we might very well be at war. I realized then that in a single morning's work, in what had appeared to be a chance and unfortunate encounter, I had been swept up into very grave events.

"Is there aught else I can do for it—for you—sir?" I asked.

For the first time, he smiled. I always thought he had been smiling before 'cause I could see it in his eyes. He smiled kind and full now. "Only to fetch the gelding for the work here, Mr Ironside. We must move forward with the work here on the home front as well."

"Of course, sir."

He put down his empty teacup and rose, returning to his desk. I hastily drank my tea, which was still warm and didn't taste half bad, much as I didn't want it, and got up too, trailing after him with the boy Roman trailing after me. It weren't far into the afternoon but the room was drenched in a deep gloom, with the orange glow of the fire lying in the centre of it as though it were a firedrake asleep in its darksome lair. It struck me that 'twas a fine place, and that the Duke had done well reclaiming it from dereliction.

"I am sure," said the Duke as he bent to scribble something on a paper, "that Hob can spare you a week or a fortnight." He glanced up under his brows, a way that he had which I was coming to know. "Do you know the rose hill?"

"Aye, sir." I gave my cap a little shake. "I know the place. Ain't been there, but I know it."

"Excellent." He resumed his scribbling. I watched the fine black scrawl flash wildly across the page. I couldn't read it anyhow, as I'd never been taught my letters, but I wondered that a fairy could read his writing even with a full alphabet in his head, he wrote so fast. But it was the only hurried thing he did. He seemed otherwise to have what I suppose folk in these parts call the wiggan gentleness, mostly 'cause of the old wise woman that has lived since the beginning of time down in the wood where the three rowans grow. Don't reckon myself there is anything wiggan about it. He finished writing and dusted the two sheets, folded them, sealed them, and handed them over to me. I took them with some trepidation. "This," he said of the first, "is for the foreman Hob, and this is for the fairy at Blodugwall. Mind you pass by on your way back from the rose hill to fetch the horse."

I slipped the two letters inside my grimy corduroy vest where they would be safe from the rain. "I'll mind, sir... Hob won't know why I've gone?"

The Duke shook his head. "I've given you leave to fetch a horse for the work, and that is true. That is all the truth Hob needs to know." A shadow passed across his face once more and he looked thoughtfully down at his son. "It's a curious weight and business, Mr Ironside, having to carry more truth than one can tell."

"Aye, sir."

I minded those words often on my road since then.

The door to the common room clicked open, and the figure of Lefe-Rogn slipped silently in. 'Twas uncanny, how so big a body could be so quiet. The atmosphere which the Duke's pensiveness had brought on the room vanished almost at once as the fairy said, "Is it that time already? Mind you are not late for supper."

"He'll be back in time for supper," said Lefe-Rogn, striding forward and catching hold of Roman's shoulder in a firm, shaking grip. I was surprised at how precisely he spoke our language. "He can smell that cooking clear across Kartusca."

"Mm," mused his father. "I reckon that he can."

Quiet as a mouse, Aventine had joined us, stealing up with her sewing clutched behind her back. Those beguiling lashes of hers flickered upward as she gazed at her father. "Please, might I go too?"

The Duke frowned good-naturedly. "Yes, you may go. If it isn't a mither to Lefe-Rogn and if you promise not to lose your hat to a hedgerow again."

The lashes flared round the eyes with embarrassment and the maid shot a glance my way. I made sure I was suddenly busy fiddling with my cap.

"Nay," rumbled the Catti. "I'll just go round by the garden shed and fetch a hammer and a few nails. The wind won't snatch her hat off."

The Duke nodded. "Yes, and nail Master Roman's coattails to his pony's saddle while you are about it, please. I can't afford losing him to a hedgerow too."

Lefe-Rogn bundled the two children off with remarkable dignity to fetch their galoshes and slickers for an afternoon ride in the rain, and the Duke and I followed slowly. Funny odd thing how it is: I walked into his house feeling an uncomfortable stranger, and I was walking out again feeling like an unassuming equal. He's that sort of fairy.

We followed the Catti and the two children to the outer doorway of the damp mudroom and watched them off, the horse and two ponies jogging through the rain, which had slackened a little, and rolling mists, which had thickened. When the jinkeh-jink of bridle-bit had faded off into the hush of the rain, I turned to take my leave of the Duke as well.

Was he always going away? I wondered. For he had again, gazing off across the shrouded garden and stable yard. He had touched the runnel of rainwater which was coursing down the stone casement of the doorway, and he was rubbing his fingers absentmindedly together. What did he see? I suddenly wondered if there was something to the wiggan gentleness, and I shivered. They said the king's particular friends were all a bit strange, standing a bit uneasily on the normal turf of the world as if they didn't quite belong there. And the Duke was one of the king's particular friends. I half wished to break his silence, but I didn't know what to say.

"If this becomes a somewhat sure thing," he said, a little to me, a little to himself, and perhaps a little to the mists beyond. Then he cocked his head, sliding his gaze upward to me, and he was that genial, mocking fairy again. "I plan to move my family back to Faerie at the end of the month. It is my understanding that you are not a landowner... Would you find it in your heart to see to Godolfin for me through the summer months?"

I stared at him. I knew I was gauping myself, but I couldn't quite help it. I'm not sure how much time passed between his words and mine. I stammered out at last, " 'M not fit for a task like that, sir! I can't read nor write, and you can forget sums n' all unless it's by my fingers. Why—" I cast a bewildered glance at what little of the steading yard I could see in the gloom. "I shouldn't know where to begin."

"Nonsense," said the Duke, gently, firmly. "You are downland-bred, a Kartuscan fairy. You know the land and the land knows you. That gets a fairy far, I find, letters and sums aside." And the mockery, I saw, had gone out of his eyes as he spoke. He has a way of putting things, that fairy does, and looking at you like he's looking clean through you to your hidden inside. Somehow I held that gaze, though 'twas the hardest thing in the world I reckon I've ever done. "Hold her for me. It is as important a thing to us Kartuscan folk as holding together the peace with the Black Catti is for our government."

He has a way of putting things.

'Twas I who offered the hand this time and he took it, smiling that faintly bitter smile of his. "Until next time, Mr Ironside."

"Gawd keep ye," I returned and, taking back my hand, struck out into the blowy face of the downland rain to find old Hob the foreman and be on my way.

Aye, by heaven and the uncanny rowan, 'tis a funny odd thing how a fellow's life can turn so unfamiliar at the bend of an old familiar track. But a lark struck up its wet tune in the hedge as I went along, an' it's in my mind that it conjured up that thrill in me again so that I found myself looking forward, as I'd never looked forward to a thing before, to the life the Duke of Kartusca had placed into my hands.

April 7, 2011

Puck and the Roman Centurion's Song

the roman centurion's song

Legate, I had the news last night - my cohort ordered home

by ship to Portus Itius and thence by road to Rome.

I've marched the companies aboard, the arms are stowed below:

now let another take my sword. Command me not to go!

I've served in Britain forty years, from Vectis to the Wall.

I have none other home than this, nor any life at all.

Last night I did not understand, but, now the hour draws near

that calls me to my native land, I feel that land is here.

Here where men say my name was made, here where my work was done;

here where my dearest dead are laid - my wife - my wife and son;

here where time, custom, grief and toil, age, memory, service, love,

have rooted me in British soil. Ah, how can I remove?

For me this land, that sea, these airs, those folk and fields suffice.

What purple Southern pomp can match our changeful Northern skies,

black with December snows unshed or pearled with August haze -

the clanging arch of steel-grey March, or June's long-lighted days?

You'll follow widening Rhodanus till vine and olive lean

aslant before the sunny breeze that sweeps Nemausus clean

to Arelate's triple gate; but let me linger on,

here where our stiff-necked British oaks confront Euroclydon!

You'll take the old Aurelian Road through shore-descending pines

where, blue as any peacock's neck, the Tyrrhene Ocean shines.

You'll go where laurel crowns are won, but - will you e're forget

the scent of hawthorn in the sun, or bracket in the wet?

Let me work here for Britain's sake - at any task you will -

a marsh to drain, a road to make or native troops to drill.

Some Western camp (I know the Pict) or granite Border keep,

mid seas of heather derelict, where our old messmates sleep.

Legate, I come to you in tears - my cohort ordered home!

I've served in Britain forty years. What should I do in Rome?

Here is my heart, my soul, my mind - the only life I know.

I cannot leave it all behind. Command me not to go!

A fan of Sutcliff (I know there are several out there, at the very least) will easily pick out the influence for several of her novels in this single poem. The Anglo-Indian poet is the voice of people translated to Britain over the years, whether physically or merely in literature. There is something compelling, something wildly magical beneath the hum-drum of daily life (which is the same the whole world over) that makes Britain unique.

puck's song

See you the dimpled track that runs,

all hollow through the wheat?

O that was where they hauled the guns

that smote King Philip's fleet.

See you our little mill that clacks,

so busy by the brook?

She has ground her corn and paid her tax

ever since Domesday Book.

See you our stilly woods of oak,

and the dread ditch beside?

O that was where the Saxons broke,

on the day that Harold died.

See you the windy levels spread

about the gates of Rye?

O that was where the Northman fled

when Alfred's ships came by.

See you our pastures wide and lone,

where the red oxen browse?

O there was a City thronged and known

ere London boasted a house.

And see you, after rain, the trace

of mound and ditch and wall?

O that was a Legion's camping-place,

when Caesar sailed from Gaul.

And see you marks that show and fade,

like shadows on the Downs?

O they are the lines the Flint Men made,

to guard their wondrous towns.

Trackway and Camp and City lost,

Salt Marsh where now is corn;

Old Wars, old Peace, old Arts that cease,

and so was England born!

She is not any common Earth,

water or wood or air,

but Merlin's Isle of Gramarye,

where you and I will fare.

Whether you like poetry or not, I highly recommend this bit o' the classics. Pick up Kipling! You will be glad you did.

April 4, 2011

Spring Special

Abigail and I are offering a spring sale on our books The Shadow Things and The Soldier's Cross, from now until April 30. The books will be available for $20 (combined, not each), including shipping, and will also be autographed; if you would like a specific note in each, post a comment with the desired inscription, or email Abigail (jeanne@squeakycleanreviews.com) or me (sprigofbroom293@gmail.com). If you enjoy the books, we would love it if you posted your thoughts in an Amazon review!

Abigail and I are offering a spring sale on our books The Shadow Things and The Soldier's Cross, from now until April 30. The books will be available for $20 (combined, not each), including shipping, and will also be autographed; if you would like a specific note in each, post a comment with the desired inscription, or email Abigail (jeanne@squeakycleanreviews.com) or me (sprigofbroom293@gmail.com). If you enjoy the books, we would love it if you posted your thoughts in an Amazon review!The Shadow Things:

The Legions have left the province of Britain and the Western Roman Empire has dissolved into chaos. With the world plunged into darkness, paganism and superstition are as rampant as ever. In the Down country of southern Britain, young Indi has grown up knowing nothing more than his gods of horses and thunder; so when a man from across the sea comes preaching a single God slain on a cross, Indi must choose between his gods or the one God and face the consequences of his decision.

The Soldier's Cross:

A.D. 1415 - Fiona's world is a carefully built castle in the air, made up of the fancies, wishes, and memories of her childhood. It begins to crumble as she watches her brother march away to join in the English invasion of France. It falls to pieces when he is brought home dead.

Robbed of the one dearest to her and alone in the world, Fiona turns to her brother's silver cross in search of the peace he said it would bring. But when she finds it missing, she swears she will have it and sets out on a journey across the Channel and war-ravaged France to regain it and find the peace it carries.

Multiple Copies April Special $17.50

April 2, 2011

The Shield Ring

For no reason I can give, I have always had a tingling curiosity, rather shy and yet at the same time determined, of the old Nordic world. This interest surfaced most vividly in a small story I wrote about the gods Tyr and Loki and their fight over the welfare of two humans which, in legendary fashion, turned out to be a truly tragic story, so tragic that no one in my family who has read it much liked it. Ah, well... Since then the interest has submerged itself under the Matter of Rome and what the Matter of Rome made of Britain which, in Roman fashion, served to dominate my other more peripheral interests.

I began a book, some years ago, by Rosemary Sutcliff called Sword Song. This last book of Sutcliff's was published posthumously by her godson Anthony Lawton, whose acquaintance I have had the pleasure of making, if only through emails. Unfortunately, Sutcliff died before she was able to complete her typical second and third drafts of the manuscript, and I believe that when I attempted to read Sword Song I could feel her final touches lacking. I put the book down unfinished, and let it lie, knowing that one day, in the distant future, I would take it up again. This was the first time I had seen Sutcliff's dealings with the Nordic kind, and I was a little put off by the unavoidable fact that its author didn't have time to polish it.

But, enjoying Sutcliff as much as I do, I was willing to give her a second chance. Not in Sword Song, not yet. Instead I took up the last of those books which loosely follow a family by way of an emerald signet ring, a ring with a dolphin engraved in the gem. Of course, I did not realize this until, among the inheritance that Bjorn was given by his foster-father, we found his father's ring. So I was still a little uncertain when I began reading, wondering how I would like a story about Vikings and Normans, hoping the while that a story set in the Lake District (which I should love some day to see) would make up for anything that might be lacking.

This is the reconstruction of a true story. In her author's note, Sutcliff assures the reader that, apart from Ranulf le Meschin (whose family name can be found in the Domesday Book), the characters in the story cannot be found in history books, but in local tradition and legend. The great Norman Survey of England halts at the foot of the Lake District, and the scar-marks of whatever struggle stopped the Norman advance can still be seen there today. As with many of her stories, The Shield Ring is the imaginative reconstruction of those mysterious gaps in history which those at the time failed to fill for us.

The story opened feeling like a scene in which Dan and Una might be walking in one of Kipling's Puck stories, which I liked. I liked Frytha, young, orphaned, uncertain Frytha, and I liked Bjorn's frank mocking demeanour, even as a young child, as though he were the King of Norway. They drew me in, the two of them, and their unspoken pact with each other. That serious unspoken bond, even in the midst of childhood, is something I have always appreciated. Frytha, having been uprooted at an early age from her family home, has a character which changes as she grows older, a character which changes naturally with age while the essentials remain the same, while Bjorn, after the first meeting, remains as potent and faintly mocking as the King of Norway throughout the book, though circumstances hammer his personality harder and denser as time passes.

Frytha. Orphaned as a child by a Norman raid, Frthya was taken by her father's herdsman Grim to join the Viking settlement in Lake Land. Growing up alongside her friend Bjorn, as war looms on the horizon, she wishes she was born to the sword side instead of the distaff side, but she proves her worth nevertheless. Though she directs her attention most often to the sword side of the fire where Bjorn operates, she gives the reader a glimpse into the woman's world of the Viking settlement as well.

Bjorn. Also an orphan, Bjorn is raised by his foster-father Haethcyn, the Hall Harper to Jarl Buthar of Lake Land. At an early age he shows the signs of a keen harper himself, but his own background, having strains of Welsh blood as well as Scandinavian, and his certain knowledge that one day he will be called upon to hang the fate of Lake Land in his hands lends to his harping a certain deep, melancholy appeal which few save Frytha really understand.

Aikin the Beloved. After the death of his foster-father Ari Knudson at the hands of the Normans, Aikin stands out among the warriors as a kind of fierce and furious, quiet silver flame of vengeance. Under Jarl Buth

ar he heads the Buthardale resistance against the Normans, an oddly gentle and charismatic figure to carry the day.

ar he heads the Buthardale resistance against the Normans, an oddly gentle and charismatic figure to carry the day.Among the handful of characters followed in this story, these three held both my attention and my heart and became, in their odd, different ways, friends to me.

I was able to relate to Frytha's unspoken, unasked understanding of the pattern of things, of why events unfolded as they did. Her sensibleness, her inner fire, her quiet fears, everything rang true to me as female characters so rarely do. In her eyes the Lake Land took on its living lustre as I read so that, though I have never been there myself, I could feel the throb of life in the earth beneath her bare brown feet. The dizzying loftiness of the fells, the plunging drops

into the glens purple and green with shadow (white, in places, where the bilberry was fleeced with bloom), seemed to swell on my vision with all the immensity of their vasty wildness. And more than that, just as Frytha was a stranger to Buthardale at the beginning and, at the end, considered it home worth dying for, so I was made to feel the same to a land I have never seen in a time I have never visited.

into the glens purple and green with shadow (white, in places, where the bilberry was fleeced with bloom), seemed to swell on my vision with all the immensity of their vasty wildness. And more than that, just as Frytha was a stranger to Buthardale at the beginning and, at the end, considered it home worth dying for, so I was made to feel the same to a land I have never seen in a time I have never visited.On a more emotional level, Bjorn carries the main thrust of the story. The Norman have tried for twenty, thirty years to extract from the Lake Land people the location of Buthardale, and no one has ever told. Bjorn's unspoken certainty that one day he, too, will have his strength tested at Norman hands puts him at a kind of distance for much of the story, his faintly mocking demeanour a mask for the terrible surety underneath. Which makes the moment of his trial and his own triumph, by comparison, dim the triumph of the Lake Land people against the Normans. Bjorn stands out from among his dolphin-ring'd ancestors as strong, defiant, loyal, and shining as a hero while staying close enough to allow the reader to feel his heartbeat in the text.

Aikin the Beloved resumes his lawful place by tradition in the story: the hero-figure, the legendary man. Sutcliff never shows the story through his eyes, but follows him from time to time through the eyes of others. He is the fierce white shining genius of the story, a genius of determination and vengeance, of heart-bursting loyalty, coupled with an odd but fitting gentleness. Unlike Frytha and Bjorn, Aikin never seems to age throughout the story, and in his agelessness, he stands out to me as a sort of embodiment of the Lake Land fells, impassable and beautiful at once.

Aikin's How still looks down on Keskadale and the low ground toward Derwentwater, marking the place where Aikin the Beloved was laid, with his great sword Wave-flame in his hand and his hound Garm at his feet, after the last battle of all.Among the gathering of characters in this story, there is one last addition which struck this tale with a true and throbbing note: Beowulf. Not the man himself, as such. The story of Beowulf, at this point, has been a story now for a very long time. But as with any legend, the genius of the great Geat warrior overshadows and empowers the steps of young Bjorn to the culmination of his fight, and he knows it. He played it on his harp, though only Frytha understood what he meant by it. The shades of Beowulf and Wiglaf stream in the dale sunset behind Bjorn and Frytha, a sunset lit by the firedrake. As Rich Mullins once sang, "Stories like that make a boy grow bold, stories like that make a man walk straight."

And we need heroes, don't we? The Shield Ring is a story of heroes, heroes unsung until Sutcliff took up her pen. From holm-gang to harp-song, heroes fill this story from beyond the fringes of the Domesday Book, from beyond the Norman pale, and with a strange sense of home-coming the long saga of the dolphin-ring brings itself most satisfactorily to a close.

March 23, 2011

Interview With Tessa From Christ is Write

Tessa on her blog Christ Is Write interviewed my sister Abigail and I about our recent published works "The Shadow Things" and "The Soldier's Cross," and about what it is like to be a young writer and author.

Check it out! Here's a sneak-peek.

What sort of challenges have you faced from dealing with your career as an author and being a student as well?

Abigail:

Being homeschooled has been a very helpful in affording time for me to write during the day, and my mother is very flexible; I am able to arrange my schedule and do both schoolwork and writing with relative ease, although during some parts of the semester I have to focus more on reports and exams. Also, now that I am published, my writing counts toward Grammar as a school subject.

Jenny:

I completely ignored my schoolwork and drove Mom crazy. Honestly, as soon as I was reasonably done with a subject, I would scamper back to my computer and bang out some more on a story. Or, even worse, I would procrastinate like nobody's business on my schoolwork in favor of writing on a story. I did, however, manage to graduate with decent grades, and now that I am married I do a manageable job juggling writing and tending the home.

****

So yes, I'm not dead. I'm even contactable. Meanwhiletide I'm working on some character busts for Adamantine, and when I'm done I hope to make a proper post for them here on Penslayer. Stay tuned! Wiglaf's sketch is being a jerk. The things I suffer...!

February 23, 2011

Buff Coats and Green Vales

Yeah, several jinxes just rang the doorbell, wanting to be let in for tea. I suppose they can at least fold the laundry while they are here.

After NaNo (which is like saying "after the war..."), I was bushed. I was creatively

wrung out. I was a limp noodle with no alfredo sauce. My proverbial muses had taken a trip to the Lake District and left me behind. Throughout December I told myself that, after the strain of the previous month, this was understandable. I needed to rest my little grey cells a bit. Come January, I would be right as rain.

wrung out. I was a limp noodle with no alfredo sauce. My proverbial muses had taken a trip to the Lake District and left me behind. Throughout December I told myself that, after the strain of the previous month, this was understandable. I needed to rest my little grey cells a bit. Come January, I would be right as rain.Jenny isn't the best weather forecaster in the world. Come January 1st, she sat down like a good girl, opened her document, took a deep breath...and wrote a sentence. Then she tugged and pleaded and hammered and cajoled her imagination, and wrote another sentence. The war wasn't over. It was grueling! Much of January consisted of no writing and lots of guilt-trips. February, which had been intended as a sort of miniature NaNo, flared, sputtered, and died an obscure and lonesome death.

And then, one day, she sat down at her computer with Abigail scribbling in a notebook beside her, and she started typing. She typed and typed, and kept typing, and it was something glorious. The words just flowed. In the midst of a stretch of perfectly spring-time days, warm and sunshiny, Between Earth and Sky obligingly blossomed for me. I have, so far as I am aware, successfully introduced all the pivotal characters of the plot and made Anna good-naturedly furious that I left her hanging and haven't written even more. You can't please everybody.

Well, that's what I've been writing. As for what I have been reading, I managed to finally get my hands on a lovely little red hard-bound copy of Rosemary Sutcliff's Simon, a small novel about the English Civil War. Something Jenny does not usually tell people is that, when she was a child, her favourite imaginary friend was Oliver Cromwell. She could tell you, though she does not care to, about the adventures she and Noll and Dick had in the countryside of Cambridgeshire, and about London (which she never liked), and all sorts of wild and ridiculous things that a child can come up with which are at once magical and implausible. While she is now too old to carry on imaginary games, and the Civil War is rather too fixed in history to be tampered with, the spirit of her best childhood friend lives on in another of her characters, and the adventures continue.

"But why on earth...?"

I can't answer that. As dorky and as boring as it sounds, even a brief and passing mention of the English Civil War makes my heart skip a beat and my mind rush away to Harry falling in the fens and nearly drowning before we could fish him out again. So you can imagine my thrill when I finally acquired a copy of Sutcliff's little book, which is hard to find and not exac

tly inexpensive. I devoured it. Simon, blunt, kind-hearted, Devonshire Simon whisked my heart away; and Amias, who is very like her later Flavius with his wild red hair, mocking laughter and taste for adventure: those two seemed to embody the spirit of the war in a way only Sutcliff could pull off. I am sure that, if you really didn't care, the story would seem odd, a rush of several years' worth of action whirling by, touched on only briefly. Maybe that is why it is so hard to find, and so unheard-of. For myself, it was a different story. I knew these names and faces, these happenstances, and watching my favourite author bring some of my favourite people to life was splendid. Never did a cavalry charge grow boring, never did a siege grow dull. At the heart of it was always Parliamentary Simon and his heart-felt friendship with his Royalist best friend. I laughed, I cried, I held my breath at the moment Simon swung round to find none other than Old Noll himself standing by to talk with him in his gruff, familiar farmer's voice. Fiery Tom Fairfax, with whom I had never been well acquainted, was a shining light at the head of the story Simon followed; and, underneath it all, Simon's family and farm waiting for him to come back to them: an emotional touch with all the marks of Sutcliff's deftness upon it.

tly inexpensive. I devoured it. Simon, blunt, kind-hearted, Devonshire Simon whisked my heart away; and Amias, who is very like her later Flavius with his wild red hair, mocking laughter and taste for adventure: those two seemed to embody the spirit of the war in a way only Sutcliff could pull off. I am sure that, if you really didn't care, the story would seem odd, a rush of several years' worth of action whirling by, touched on only briefly. Maybe that is why it is so hard to find, and so unheard-of. For myself, it was a different story. I knew these names and faces, these happenstances, and watching my favourite author bring some of my favourite people to life was splendid. Never did a cavalry charge grow boring, never did a siege grow dull. At the heart of it was always Parliamentary Simon and his heart-felt friendship with his Royalist best friend. I laughed, I cried, I held my breath at the moment Simon swung round to find none other than Old Noll himself standing by to talk with him in his gruff, familiar farmer's voice. Fiery Tom Fairfax, with whom I had never been well acquainted, was a shining light at the head of the story Simon followed; and, underneath it all, Simon's family and farm waiting for him to come back to them: an emotional touch with all the marks of Sutcliff's deftness upon it.Thank you, Sutcliff. This is a treasure.

[the sketch isn't by me, it's by someone else of someone else's character, but i borrowed him to embody the Parliamentary Forces. thanks!]

February 17, 2011

Seriously, I Wrote That?

Yes, it's me, editing Adamantine. I am not sure I have met anyone who particularly liked editing. Having flogged yourself for months, sometimes even years, to cross the finish line and hold up the completed product of a manuscript...you have to go back and edit it? The whole thing? All of it? Really?

Yes, it's me, editing Adamantine. I am not sure I have met anyone who particularly liked editing. Having flogged yourself for months, sometimes even years, to cross the finish line and hold up the completed product of a manuscript...you have to go back and edit it? The whole thing? All of it? Really?Well, of course you do. No work is perfect on the first run-through, and it goes without saying that any story will need plenty of polishing, sometimes even a bit of demolition and reconstruction. Adamantine is needing a good bit of both. Depending on the size of the story and the length of time you spent working on it, the daunting aspect of editing will vary. Flexing its muscles in the vicinity of 213,000 words, Adamantine is a bit daunting - especially since the first half of it is, in my own words, "lame rubbish!"

"Lame rubbish" is probably something every writer discovers has snuck in his manuscript when his back was turned. Now, everyone assures me, "It's not lame rubbish. It's fine! I liked it!" Ye-es, well...I don't. And that's what matters. Lame rubbish has got to be dwelt with. Soon. When I make another cup of tea. Tomorrow. When it's sunny. After I've thought about it for a while. These are all my excuses that I have used and a few that I have on reserve just in case I need them. Unfortunately, I can't afford to use excuses, and that lame rubbish of Adamantine's first half has got to be dwelt with.

"So, Jenny, why are you making a post about it?"

Yeah, well, you got me there. Chiefly because I know we all make lame rubbish, and unless we are very driven and angelic people (like Abigail), that lame rubbish will crouch like a fat hairy spider on the periphery of our awareness and grow and grow until it blots out all the good bits in the story we have written, and until our most feeble desires to edit sputters out like a candle in a gale. So lame rubbish happens. It happens to everyone. Take a deep breath, throw out your chest, and grab your red pen (or blue - mine happens to be blue). That lame rubbish dragon isn't going to slay itself for you.

Fairytales are more than true, not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten. ~ G.K. ChestertonGrammar. If you're anything like me (and I do apologize if you are), you will be so wrapped up in what you are writing that you just rush on through without hesitation, murdering the English laws of grammar as you pass by. I'm not really in the habit of murder, but on reflection I have unearthed some rather hideous and occasionally embarrassing mistakes which I made in my haste to write out a section. This isn't necessarily a bad thing. Unless you are Abigail, you can't keep track of everything at once, and sometimes spelling and grammar have to be put on the back burner while you pound out the plot, and then you can come back to it later.

English professors, please don't kill me.

And yes, you will probably run into some embarrassments. I committed the heinous crime of using the same word twice, quite close together in a paragraph, to describe two completely different things. I was mortified. I'm still getting over it. But it happens, and it has to be fixed, so put a bold face on it and don't worry. You're definitely not alone.

Where do I start? Well, that's really up to you. I like to tell myself that I editing the second half of Adamantine first because I wanted to really cement in my mind the way the characters and circumstances culminated, and to immerse myself still further in their final developments. Truthfully, I just like the second half better and I always save the worst for last. Julie Andrews will of course assure you that the beginning is the best place to start. But I do think that at least perusing the culminating chapters and fixing them in your mind will help you adjust the beginning ones. If you're a foreshadowing sort of person, this will definitely help. And even if you are not, knowing what your characters become in the end will help you smooth out the developmental paths in the story for the reader to follow. You know how your characters got to where they are in the end, but make sure the reader can follow that clearly. It's amazing the disconnect there can be between the author's mind and the reader's. Ho hum.

If you start at the end be sure to keep your whole story balanced. The end of your story should have much more developed characters, much more gravity, much more importance than the beginning because everything should be unfolding, and all the questions should be answered (unless you are writing a series). With all the finality of "It's done," the end of the story has the potential to seriously outweigh the beginning of the story. In terms of development and plot, this is as it should be. In terms of style and interest, this should not be. The beginning, in creating all the questions, should be just as interesting and the end which answers all the questions. If you start at the beginning keep the end in mind. As you edit, remember what you are working toward. Your first draft will undoubtedly be rough with lots of unexpected plot-twists that need to be rounded off or cut out altogether because you were not sure where you were headed on the first pass through. On an editing run, you should be able to keep in mind what the goals are and how your characters reached it, and you will be able to smooth their story out toward that goal as you go along picking up stray commas and hacking out stilted dialogue. Also, don't get discouraged by those stray commas and stilted dialogue. On your first pass through writing, you didn't really know where you were going or how you were going to get there. Wrong turns, jerky driving, it happens when you are all but lost on the road to plotdom.

In summation: don't let either the grandeur of your ending or the aimlessness of your beginning go to your head. Both are perfectly reasonable to find at the completion of a first draft, and it doesn't mean that you are an awful writer.

My beginning and my end are lame rubbish. Well, Tolkien started The Fellowship of the Ring three times, at least. That's all I can say. If you love your story that much, keep trying. You may be a world-famous author and have your story turned in a film one day. A touch of blind "I h'am teh greatest" as you write may carry you far and hold off the wave of despair if you have someone to hold you down on earth and tell you where your dialogue is stilted and your commas go awry.

Practice makes perfect. As with any art, writing takes work, and work often means uncomfortableness and sweat. Editing isn't usually the most exciting of tasks, but it's another necessary step in getting your prized story to the perfect level. On every pass you will straighten out another kink. Don't be overwhelmed by the sheer number of them (if you're like me); keep in mind all the ones you have already straightened out. As Marthe pointed out, when you're building a sandcastle and it begins to crumble, you reach out to catch it. And all you think about is what you lost, not what you managed to save. Well, in this case, the sandcastle isn't going anywhere, and you are only improving on it more and more. Keep that in mind, and keep pushing yourself. When all is said and done, you'll be glad you did.

Don't take Prospero's approach and drown your book fathoms down, whatever you do.

February 15, 2011

Dancing in the Minefields

There was a long, long silence. No sound in all the world but the sighing, singing, air-haunted stillness of the marsh under the moon. Not even a bird calling. Then Flavius said, 'So there wasn't another way out, after all - or, if there was, something went wrong and he couldn't use it.'

'There was another way out - and that was it,' Justin said slowly.

The young Centurion, who had been completely still throughout, said very softly, as though to himself,

'Greater love hath no man...'

and Justin thought it sounded as though he were quoting someone else.

Not a whole lot is known about Valentine, except that he aided the Christians and that he was martyred for his deeds. The Roman Catholic church made him the patron saint of intended couples and, in general, love, which is where our odd ideas of 'Valentine's Day' have come from, no doubt. But what I find most worthy of note is the very fact that this man in another time and place not only lived but also died for the name of Christ. Hundreds and hundreds like him also were brought to the point of shedding blood for their love of the name of Christ.

What is love? The essence of love is to seek the good of its object. In multitudinous ways, throughout our lives, we display this love in varying degrees for the people around us and, too, toward our God himself. I need not go into detail. If you love anyone, even yourself, you have displayed your love in some way. But in this body we cannot escape that nagging, clinging selfishness that taints our warmest expressions of love. Somewhere in the loving, 'I' am always there, and not in the way I should be. 'I' always manage to impose my own image on the thing or person I am loving, so that it is not purely myself loving that other thing or person, but myself loving myself as well.

we are frail

we are fearfully and wonderfully made

forged in the fires of selfish passion

choking on the fumes of selfish rage

and with these our hells and our heavens

so few inches apart

we must be awfully small

and not as strong as we think we are

We mustn't kid ourselves. Love is something the Spirit must cultivate, and not something we can stir up to any purity within ourselves. In our most ardent, heartfelt desire for good for whatever it is we love, the law that is at work in our members infuses it with selfishness.