Jennifer Freitag's Blog, page 49

June 1, 2011

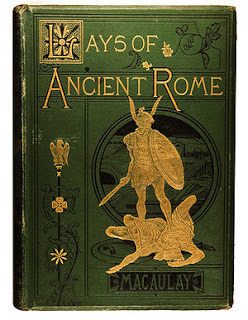

The Lays of Ancient Rome

I want to put in a plug for the old writers. You know how much I love old writing, and dead authors, and all that. I find the death of the author lends a kind of potency to good literature. A book is a man's far more significant gravestone that he leaves behind.

I want to put in a plug for the old writers. You know how much I love old writing, and dead authors, and all that. I find the death of the author lends a kind of potency to good literature. A book is a man's far more significant gravestone that he leaves behind.I just finished a battered old school edition of Thomas Babington Macaulay's The Lays of Ancient Rome - a battered old copy published in 1913 by Charles Merrill, an edition meant for schoolboys. It's a very nice copy: blue, cloth-bound, its pages yellowed and musty-scented from age, and I found that the beginning decrepitude of the book, its smallness, and its general feel of a type of book confined to past ages lent to the words inside an even greater potency. The whole thing felt old and, though old, alive. When I first cracked it open and the rush of musty book-smell wafted out at me, I was giddy.

Lars Porsena of Clusium

By the Nine Gods he swore

That the great house of Tarquin

Should suffer wrong no more.

By the Nine Gods he swore it,

And named a trysting day,

And bade his messengers ride forth,

East and west and south and north,

To summon his array.

The little school book boasts Horatius, The Battle of Lake Regillus, Virginia and The Prophecy of Capys. I was familiar with the fact that, as a boy himself, Winston Churchill had been made to learn Horatius by heart; but even without this knowledge, I think Porsena's vow would have opened the poem no less grandly for me.

With the vividness of good poetry, Horatius opens depicting the gathering of the Etruscan League against Rome. Horatius is not a lengthy poem (not like The Idylls of the King); Macaulay chooses his words perfectly, his cadence lending a marching-beat splendour to the pictures his words make. The Etruscan League gathers, thousands and thousands of soldiers from the twelve chief Etruscan cities, marching on Rome - "from the rock Tarpeian" the Romans watch the advancing devastation of the enemy host. Time is scarce, resources limited. Hopelessness hangs in the air. The city is choked with refugees from the surrounding countryside and the Senate, in dismay, watches their doom come marching down the road toward them.

And nearer fast and nearer

Doth the red whirlwind come;

And louder still and still more loud,

From underneath that rolling cloud,

Is heard the trumpet's war-note proud,

The trampling, and the hum.

And plainly and more plainly

Now through the gloom appears,

Far to left and far to right,

In broken gleams of dark-blue light,

The long array of helmets bright,

The long array of spears.

All seems lost, but the life-vein of the city could be its salvation: the Tiber might prove to gain them time, if only the bridge can be cut before the Etruscan host can swarm across. Horatius, for whom the poem is named, stands out as an image of pure Romanhood against the pitiful backdrop: faithful to the last, caring nothing of himself, whether he lives or dies, only that he does his duty for Rome.

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

"To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his Gods..."

It is the story of a very brave few holding back a tide of many. Even the enemy, awed by the display of faithfulness and prowess by Horatius and his friends, cheer them on as they throw down champion after champion sent against them.

With weeping and with laughter

Still is the story told,

How well Horatius kept the bridge

In the brave days of old.

Longer, and even more intense, follows The Battle of Lake Regillus. Several of the characters from Horatius reappear in this poem. The first poem charts the terror of pending confrontation, the second brings the forces to a head, Rome against the Etruscan League, and opening with the vantage point of time having gone by, heralding in the poetic story with the distinct overtones of victory.

Gay are the Martian Kalends:

December's Nones are gay:

But the proud Ides, when the squadron rides,

Shall be Rome's whitest day.

The call is to remember, in the name of the Great Twin Brethren, the Battle of Lake Regillus, the slaughter, the sacrifice, the heroes who lived and died there. The ghosts of dreams, the ghosts of battlefields, the ghosts of patrician families whose names have long mouldered into the dust, and the geniuses of gods bolt across the pages in rhyme and metre. The poet takes the reader through the planning of battle to the joining of battle, and describes many of the heroes who were met there on the field: the Dictator Aulus, and Æbutius Alva Master of the Knights, Mamilius of the Latian name whose helmet shone like red-gold flame, Lavinium and Laurentum, and Herminius on black Auster, Titus and false Sextus, and many, many more. The pieces are set, the board is ready - battle is engaged.

"On, Latines, on!" quoth Titus,

"See how the rebels fly!"

"Romans, stand firm!" quoth Aulus,

"And win this fight or die!"

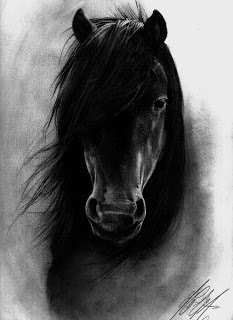

Perhaps the most stirring encounter of heroes, and the most tragic, is that of the Latian Mamilius and the Roman Herminius - the latter had helped keep the bridge in Horatius. The dark-grey charger and black Auster dash at each other, the whole battle swings and pauses round the warriors to watch, as if the earth has caught its breath in collective horror. It does not last long. The blows are swift and sure, and fatal -

And still stood all who saw them fall

While men might count a score.

But the tone of victory and defeat is carried on in the wake of the deaths of these two mighty warriors. The deed is done, but the poet follows the terrified homeward flight of Mamilius' grey horse: a riderless horse running into its own paddock is a potent image of defeat, and the people of Mamilius' Tusculum understand the image all too well.

But, like a graven image,

Black Auster kept his place,

And ever wistfully he looked

Into his master's face.

Black Auster remains over his master's fallen body, faithful even beyond death. The message of his stalwart nature, though brief, is powerful, and the reader's heart is captured by Herminius' horse so that, when the Latian Titus leaps to grab the horse's reins, the outrage is felt keenly. Furious, the Dictator springs at Titus and lays the young man in the dust, dead. Dismay falls on the Latian host. The wind is up, the tide is turning; and as Aulus swears revenge with black Auster upon Herminius' death, out of nowhere ride two splendid young warriors, in armour white as snow, on horses snowy-white. The grim face of a battlefield takes on a suddenly unearthly aspect and, like a dream, everything starts slipping: spirit and earth shift against each other, trying to fit, not quite matching up.

"By many names men call us;

In many lands we dwell:

Well Samothracia knows us;

Cyrene knows us well.

Our house in gay Tarentum

Is hung each morn with flowers:

High o'er the masts of Syracuse

Our marble portal towers;

But by the proud Eurotas

Is out dear native home;

And for the right we come to fight

Before the ranks of Rome."

So answered those strange horsemen,

And each couched low his spear;

And forthwith all the ranks of Rome

Were bold, and of good cheer.

The last charge is driven home, by Vesta's hearth, by the golden shield of Mars, driven home into the invading ranks of the Etruscan army, with the two mysterious white horsemen in the lead, slaying like there has never been slaughter before, and Aulus on black Auster hard behind them. The tide is turned, the

battlefield belongs to Rome: the day is won. The Roman host sweeps up the wreckage of the Latian army, but when those strange horsemen are looked for, they are not to be found.

battlefield belongs to Rome: the day is won. The Roman host sweeps up the wreckage of the Latian army, but when those strange horsemen are looked for, they are not to be found.But on the road to Rome are spied two gentlemen on horseback, their armour scarlet with blood, their horses bloody-red, and they announce to the fearful people in the city that the day is theirs, and that on the morrow their Dictator will ride home in triumph with the ragged corpse of Etruria's government dragged along behind him. The city is thrown into the ecstasies of joy, and the word flies throughout the countryside. But looking neither right nor left, steady on their course, the two horsemen ride on up into the Forum, bedecked with the falling laurel leaves and flowers that the wind brought off the cities garlands to them. They pause and wash their horses at Vesta's spring, then remount, all in silence, and ride through Vesta's door.

Then, like a blast, away they passed,

And no man saw them more.

The Great Twin Brethren had come and gone, and won the day, and Rome did not forget.

The next lay, a tragedy, is a brief one; only fragments of it are given in the text. Virginia is the story of a Rome which is losing its model citizens, a Rome without the Tribunes to uphold the right of the common man in the face of patrician oppression.

This is no Grecian fable, of fountains running wine,

Of maids with snaky tresses, or sailors turned to swine.

Here, in this very Forum, under the noonday sun,

In sight of all the people, the bloody deed was done.

This is a story of greed and innocence, sorrow and rage. Young Virginia, the picture of innocent feminine youth, walking through her own little world, is spotted by the wicked patrician Appius Claudius. His wealth is not enough, his power is not enough: that single dewy morning-star, which ought to have been out of his reach, had to be his. A lament for Virginia! She leaves her home in the morning, bound for her school and the duties of the day - and without warning up comes Marcus, Claudius' client, and grabs her by the arm. Her frightened screams draw a hasty crowd. Everyone knows Virginia, everyone loves Virgina; but what can they do against the likes of Appius Claudius? They have no Tribunes to defend their cause, they have no voice to lament their troubles in politics. Hopelessness hangs in the air.

Of a sudden young Icilius springs upon the scene, who had been a Tribune himself once, who was betrothed to Virginia. In a rage he conjures up the memories of the heroes who had gone before: was this why they had died, so that girls like Virginia could be snatched away by greedy paws? Think well on your fate, Romans - take a stand, or be slaves forever!

"No fire when Tiber freezes; no air in dog-star heat;

And store of rods for free-born backs, and holes for free-born feet.

Heap heavier still the fetters; bar closer still the grate;

Patient as sheep we yield us up unto your cruel hate.

But, by the Shades beneath us, and by the Gods above,

Add not unto your cruel hate your yet more cruel love!"

Icilius' speech throbs through the text: the last agonized, impassioned words of a young Rome. He ends his speech and the poem is broken, picking up again with Virginius, the girl's father, drawing her to one side of the crowd. There is a third option, a third way out of their predicament with Claudius, and Virginius knows it. He calls up memories of her childhood, he calls up his own love for her: the agony of a father saying his last farewell is in all his words.

"Then clasp me round the neck once more, and give me one more kiss;

And now, mine own dear little girl, there is no way but this."

With that he lifted high the steel, and smote her in the side,

And in her blood she sank to earth, and with one sob she died.

Stunned silence fills the Forum. The tension of a summer thunderstorm about to break crackles horrified in the air. Virginius breaks the silence only, calling for justice in the name of the Shades to be done between himself and Claudius. Stricken, but steadfast, he departs. In a fearsome rage Claudius leaps up, screaming for anyone and everyone to apprehend Virginius; but the crowd only falls back in silent respect to let the grieving father pass. The tertium quid has been taken: wickedness has been cheated, and the spark of Roman character is allowed to pass unhindered from the scene.

But Appius Claudius wants the last word. A funeral procession is made for the lovely corpse.

They brought a bier, and hung it with many a cypress crown,

And gently they uplifted her, and gently laid her down.

Decked out in the laurels of death, wreathed in cypress, Virginia's body is borne through the Forum. But Claudius is all mockery. He despises the gesture of respect shown by the crown, and commands his lictors to send the people home and bear away him the corpse. The summer thunder breaks. As the lictors advance the crowd gives tongue, growling low like an angry dog; when the lictors bare their weapons, the storm breaks. Incensed, outraged, the crowd turns on Claudius' twelve men. A Roman shield-ring hangs tenaciously about the bier as the crowd fetches whatever is to hand that can be made into a weapon.

'Twas well the lictors might not pierce to where the maiden lay,

Else surely had they been all twelve torn limb from limb that day.

Furious, Appius Claudius strives to speak, to be heard above the din of outrage and the voice of Roman feeling. But each time he was shouted down.

And thrice the tossing Forum set up a frightful yell;

"See, see, thou dog! what thou hast done; and hide thy shame in hell!

Thou that wouldst make our maidens slaves must first make slaves of men.

Tribunes! Hurrah for Tribunes! Down with the wicked Ten!"

The people have the last word, as they will always do when oppressed beyond their endurance. With stones and rods they send Claudius home, a wretched, battered sight, robbed of his desire and his image of power. The tragedy lingers, but justice has its way in the end.

...every Alban burger

Hath donned his whitest gown;

And every head in Alba

Weareth a poplar crown;

And every Alban door-post

With boughs and flowers is gay:

For to-day the dead are living;

The lost are found to-day.

With gaiety, thanksgiving, and celebration The Prophecy of Capys, the last lay, unfolds on the page. The prophecy harkens back to the early days of Rome, to the settlement on the banks of Alba Longa and the conquests of the twins Romulus and Remus. Many and magnificent are the exploits of Rhea's boys, of Mars' sons, of the she-wolf's little man-cubs. With spear and sword adorned each with the head of a foe, the brothers return triumphant to their old grandsire's hall. At the gate sits Capys the sightless seer; at the advance of Romulus upon the hall the prophecy grips the seer - a splendid, eerie sight to witness - and the luck and life to come of Rome is disclosed with a strange and heady seriousness.

"From sunrise unto sunset

All earth shall hear thy fame;

A glorious city thou shalt build,

And name it by thy name:

And there, unquenched through ages,

Like Vesta's sacred fire,

Shall live the spirit of thy nurse,

The spirit of thy sire."

The Prophecy of Capys is a fitting ending for a collection of poems for such a power empire: a strong poem, full of hope and conquest and the belief of the gods' favour. The early days are gone, the Republic is no more, the Empire has left behind only the scars of its buildings and the legacy of its laws: but Romulus' Eternal City stands on. Even in this little battered collection of poems, she lives on, and she is known everywhere.

"Where through the sand of morning-land

The camel bears the spice;

Where Atlas flings his shadow

Far o'er the western foam,

Shall be great fear on all who hear

The mighty name of Rome."

Tolle lege - take up and read.

May 25, 2011

Wanton Wednesday

Aren't archaic words just delicious? I love scrounging around Dictionary.com and my own battered copy of Webster in search of definitions to all the strange new words I run across. Why, since picking up Dorothy Sayers' Lord Peter, I've been at the dictionary three times as much as normal - quite a lot of new words, and even a bit of between-war slang. I found some really beautiful words in a poem by J.R.R. Tolkien, and if only my memory were a little better, I could cuddle them all close and even make use of them. Of course, you have to be careful with archaic words. They have to be in the proper setting, and make sense in the setting - or at least enough sense that a reader isn't thoroughly confused on his way to the dictionary. But archaic words are loads of fun, and sometimes even shouldered and clawed into quite a pretty historical setting. Archaic words are little gems.

It's Wanton Wednesday, because "miscellany" doesn't start with a W. I don't know who is supposed to be sporting about this, you or me - possibly both. At any rate, I have a number of things to share with you.

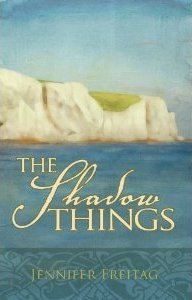

First off, Kelsey at her review blog Little Notes (she did a review of my book The Shadow Things) got a hold of me a week or so ago to do an interview. She had some excellent and really fun questions to pose at me, and I had a wonderful time doing the interview with her. By all means, pop on by and take a look!

an excerpt from The Shadow Things review from Little Notes

Why did you feel drawn to that particular time period (in regards to The Shadow Things)?

Oh, a lot of things drew me: the beauty of the South Downs, the familiarity of the post-Roman natives, the culture, and the advent of Christianity around that time. Among other things, I wanted to show Christianity getting a soul-hold on the island and displacing the pagan religions around it—and what the pagan religions thought of that. The late fifth century enabled me to do that.

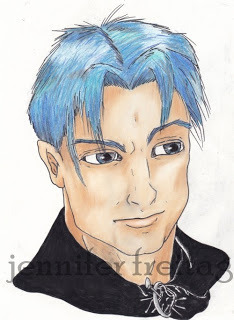

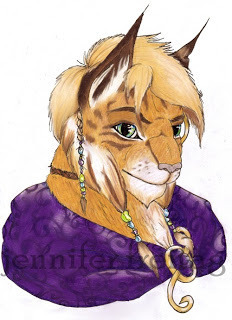

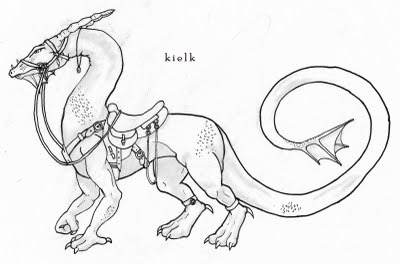

Secondly, I finally got around to making that sketch of my character Andor, which I have been meaning to do for a long time now. He looks rather cuter than he probably should be, but Abigail (my Abigail - there are a lot of Abigails) says that no one wants to be disillusioned out of his image of an adorable Andor, and that I oughtn't fret. I caught him, anyway, in his typical adoring pose. Also, that's not ketchup... I still have to ink him in, and probably get rid of the drip and gruesome so that he resembles the style I used in my dragon sketch. Probably. Maybe. Possibly. Mm, I'm not sure. He looks kind of fetching this way.

Secondly, I finally got around to making that sketch of my character Andor, which I have been meaning to do for a long time now. He looks rather cuter than he probably should be, but Abigail (my Abigail - there are a lot of Abigails) says that no one wants to be disillusioned out of his image of an adorable Andor, and that I oughtn't fret. I caught him, anyway, in his typical adoring pose. Also, that's not ketchup... I still have to ink him in, and probably get rid of the drip and gruesome so that he resembles the style I used in my dragon sketch. Probably. Maybe. Possibly. Mm, I'm not sure. He looks kind of fetching this way.Just as an aside, my heart wrenched horribly in the Lord Peter mystery The Undignified Melodrama of the Bone of Contention when the exploring party straggled into the library of the old Burdock manor and found that the housekeeper hadn't kept up the fires like she should have, and over the years the damp had got in and almost all the books were mildewed. It broke my heart. People oughtn't do that with books. If it's rude to cut a person off mid sentence while they are speaking, it ought to be socially unacceptable to ruin books like that. Poor Lord Peter was quite undone, and so was I.

May 24, 2011

Adamantine - Inklight

I got tagged with these questions by Megan. I'm a bit slow on the up-take, and I haven't quite figured out how tagging works. Do you mean tagging as one would tag a Christmas present, or tagging as in "Tag, you're it"? It's all very perplexing. But I obliged, because I was intrigued, and here I am, having dutifully filled out these billion questions which might shed a little more inklight onto my story Adamantine. Or they might not. They might just muddy it still more, I don't know. Enjoy!

I got tagged with these questions by Megan. I'm a bit slow on the up-take, and I haven't quite figured out how tagging works. Do you mean tagging as one would tag a Christmas present, or tagging as in "Tag, you're it"? It's all very perplexing. But I obliged, because I was intrigued, and here I am, having dutifully filled out these billion questions which might shed a little more inklight onto my story Adamantine. Or they might not. They might just muddy it still more, I don't know. Enjoy!Megan, this is all your fault.

1. What's your word count?

214,120 words, but I'm still editing so that number will fluctuate.

2. How long until you finish?

Aw, gee, I don't know. I would like to finish in the not-too-distant future, preferably long before the summer holidays are over.

3. If you have finished, how long did it take you?

Well, technically I have finished the story. And I've never understood the point of this question. What does it mean, knowing how long it took one to write a story? I didn't keep track of the day I started. I'm horrible at keeping time. I've been at this story for a while now, that's all I know.

4. Do you have an outline?

Hee. Hee. Hee. No.

5. Do you have a plot?

I should bally well HOPE so!

6. How many words do you typically write a day?

It depends on how inspired I am at any given time. When I've got a story really on fire, I can write upwards of several thousand words a day. When I'm piddling along, it's like pulling teeth.

7. What was your greatest word count in one day?

I think I've written five thousand words in a single day. Not particularly stellar, but not too shabby. Not too shabby.

8. What was your least impressive word count in one day?

Oy boy. Maybe…five?

9. What inspired you to write?

All the stories I was read and that I read myself when I was a child. And my imagination.

10. Does your novel/story have a theme song?

Not really, though the hymn Amazing Grace is rather important in the plot. I suppose Loreena McKennitt's "The Never-Ending Road" might squeeze in close as applicable.

11. Assign each of your major characters a theme song.

I already did. They can be found at my last Inklight post.

12. Which character is most like you?

Adamant is most like me, being the principle female character of the tale.

13. Which character would you most likely be friends with?

I like to think it would be Rhodri, if he would be patient enough with me. Considering the gruelling bruising and battering I've taken him through, I'm not sure how firm our friendship is right now. But I like him, whether or not he likes me.

14. Do you have a Gary-Stu or Mary Sue character?

None of the tests my characters have taken have labelled them as Stues or Sues.

15. Who is your favourite character in your novel?

Ack, that's a difficult question. Rhodri first, and the pooka as a close second.

16. Have your characters ever done something completely unexpected?

Yes. Oh yes. Oh goodness, yes. Rhodri has a knack for it, throwing sudden rabbit-trails out into the conversation and taking everyone down the rabbit-hole while I stay above wondering if I really ought to plunge down after them.

17. Have you based any of your novel directly on personal experiences?

It's really hard to say. Of course I haven't been to Faerie, of course I haven't met a flesh-and-blood Catti. Or course I haven't got stabbed into a pretty sieve by spears. But when you're thinking all this stuff up, it really is just like it is all happening to you. A few things, which I shan't tell, have happened to me before, and wormed their way into the story.

18. Do you believe in plot bunnies?

Do I—do I believe in plot bunnies? Have you been down the rabbit-hole, Miss Alice?Have you seen my plot bunnies?

19. Is there magic in your novel/story?

It depends on how you define 'magic.' Yes, there is some. There is other stuff, but that, said Kipling, said Lewis said Aristotle, is another story—and I shan't spoil it.

20. Are any holidays celebrated in your novel/story?

Christmas is observed in several capacities, both Christian and pagan; the important astrological points of the year are observed by most folk.

21. Does anyone die?

Am I allowed an evil chuckle? Yes, there is death.

22. How many cups of coffee/tea have you consumed during your writing experience?

I couldn't possibly tell you. The quantity is beyond counting. I don't bother keeping track of all the cups of tea I drink.

23. What is the latest you have stayed up writing?

Midnight is probably the latest I have stayed up.

24. What is the best line?

Aw, gee, I don't want to give away best lines. I'm inordinately fond of "A blush, I think, would be appropriate."

25. What is the worst line?

"Let me go! Ow!"

26. Have you dreamed about your novel/story or its characters?

I think I have, maybe once or twice, and it was something really darned clever, too, with Rhodri…but now I can't recall what it was. Blast.

27. Does your novel rely heavily on allegory?

Not at all. I'm not sure there is any intentional allegory in it at all, though a bit might have slipped in while my back was turned.

28. Summarize your novel/story in under fifteen words.

Concluding Beowulf's tale, Adamant must find Wiglaf, turning the world upside-down in the process.

29. Do you love all your characters?

Absolutely! Well, I like some, and I love some, and I love to hate some.

30. Have you done something sadistic or cruel to your characters specifically to increase your word count?

I've been sadistic and cruel, perhaps, but never for the sole purpose of increasing my word count. What dastardly folly!

31. What was the last thing your main character ate?

Uh, punch, I think. And those little tea-sandwiches with the cucumbers inside. I love those things.

32. Describe your main character in three words.

Demure. Passionate. Adamantine.

33. What would your antagonists dress up as for Halloween?

That's easy. The Dullahan and the Cóiste Bodhar.

34. Does anyone in your story go to a place of worship?

Monasteries are mentioned, and the characters spend the night at a convent.

35. How many romantic relationships take place in your novel/story?

Mm, several. Telling would be telling, wouldn't it, eh? "Even the smell of roses is not what they supposes; but more than mind discloses and more than men believe."

36. Are there any explosions in your novel/story?

Apart from tempers, there are no chemical explosions.

37. Is there an apocalypse in your novel/story?

If you define "apocalypse" as it ought to be defined, you might say that, yes.

38. Does your novel take place in a post-apocalyptic world?

Don't be ridiculous.

39. Are there zombies, vampires or werewolves in your novel/story?

No. No. Just no.

40. Are there witches, wizards or mythological creatures/figures in your novel/story?

There are a number of magical creatures included in the plot, witches among them.

41. Is anyone reincarnated?

No…

42. Is anyone physically ailed?

Oh please, I laugh. There is plenty of battering about, cavorting with weapons, drawn blood, etc. Fun times. Fun times, old boy. Fun times.

43. Is anyone mentally ill?

A character reflects on the possible fact of his having gone mad in the past.

44. Does anyone have swine flu?

No pigs fly in this story, I'm sorry.

45. Who has pets in your novel and what are they?

Adamant has a gargoyle, Andor.

46. Are there angels, demons, or any religious references/figures in your novel/story?

There are several references and key characters of supernatural import, some real, some just pagan.

47. How about political figures?

There are kings, chieftains, military officers, etc.

48. Is there incessant drinking?

I wouldn't call it incessant. They come up for air. No, no, there isn't incessant drinking.

49. Are there board games? If so, which ones?

Only political intrigue and the like.

50. Are there any dream sequences?

Yes, several.

51. Is there humor?

I suppose that's rather up to the reader to decide.

52. Is there tragedy?

Again, that's for the reader to determine.

53. Does anyone have a temper tantrum?

I don't know about temper tantrums. Tempers do come to a head on occasion. A head comes to tempers, as to that.

54. How many characters end up single at the end of your novel/story?

I don't break up any couples. Not in this story, at least.

55. Is anyone in your novel/story adopted?

Well, I suppose you might say Wiglaf was adopted by Beowulf. Two characters sort of unofficially adopt each other.

56. Does anyone in your novel/story wear glasses?

Mm, no.

57. Has your novel/story provided insight about your life?

I like to think so.

58. Your personality?

If anything, I hope this story has helped shape my personality for the better.

59. Has your novel/story inspired anyone?

I really don't know. I certainly hope so.

60. How many people have asked to read your novel/story?

I'm afraid I didn't stop to count. Everyone I know has expressed an interest in reading it; I suppose that's something.

61. Have you drawn any of your characters?

Yes, actually, quite a number of them.

62. Has anyone drawn your characters for you?

No, not to my knowledge.

63. Does anyone vomit in your novel/story?

Oh, vomiting is so much fun. It depicts pathos. It depicts suffering. It engenders feelings in the reader for the character vomiting. Or else the characters have a lousy cook and a case of food poisoning. Yes, a character vomits.

64. Does anyone bleed in your novel/story?

A better question would be, does anyone not bleed in the story.

65. Do any of your characters watch TV?

Heavens, no. There is no television. There is no concept of television. Save for the illiterate character, everyone is a passable or devoted reader.

66. What size shoe does your main character wear?

Adamant is English, but you must excuse my ignorance of English shoe size scales. She wears a six or a six-and-a-half. She has very small feet, quite dainty and lady-like.

67. Do any of the characters in your novel/story use a computer?

Give me a cudgel and I'll have at the person who dreams of putting computers in Faerie.

68. How would you react if your novel/story was erased entirely?

How would you like it if your heart were ripped out, stamped into the mud, burned, hurled into the ocean, followed by your toes, your fingers, and then your eyeballs? I don't think about such things. It is simply too horrible to contemplate.

69. Did you cry at killing off any of your characters?

Not strictly speaking, but Beowulf's death always makes me cry.

70. Did you cheer when killing off one of your characters?

Yes, I did. Such fun! Hee, hee.

71. What advice would you give to a fellow writer?

Persevere. Don't be content with the mediocre and cliché. Read good literature.

72. Describe your ending in three words.

Enchanting. Fulfilling. Gratifying.

73. Are there any love triangles, squares, hexagons, etc.?

There are a few snarls, but only one triangle to speak of, if you want to call it a triangle.

74. On a scale of 1-10 (1 being the least stressful, 10 being the most) how does your stress rank?

It rather depends on the importance of the scene and how well (or not well) it is coming. At the moment I would put myself around a three or a four, though I should probably motivate myself and be around a six or a seven.

75. Was it worth it?

As the author, absolutely. I enjoyed this adventure immensely, and I'm glad I got to invent and get to know these characters, and watch them grow (or degenerate, as the case may be). As for the readership, they have yet to tell me. I hope it was worth it to them.

I'm going to spend the rest of the day doing laundry and editing Adamantine to make up for the hour I wasted last night writing this up. Oh well, it was fun while it lasted. How about you folk? I'll stick Christmas labels on you all, because I want to see you answer these questions too - if only to know that I wasn't the only one wasting and hour at this silliness. The game's afoot: follow your spirit, and upon this charge cry - "God for Harry, England, and Saint George!"

May 18, 2011

Beautiful People - Andor

More beautiful people! Actually, given this month's subject of Georgie's and Sky's Beautiful People, the title is massively ironic. And, I confess, it gives me great delight to make it so. Well, for those who don't know, here is a brief explanation of Beautiful People before we begin the May-June session.

More beautiful people! Actually, given this month's subject of Georgie's and Sky's Beautiful People, the title is massively ironic. And, I confess, it gives me great delight to make it so. Well, for those who don't know, here is a brief explanation of Beautiful People before we begin the May-June session.Once a month Sky and [Georgie] will be posting a list of 10 questions for you to answer about your characters. You can use the same character every month, or choose a new one for each set of questions. Your call. You can answer all the questions, just one, or however many you have the time and energy to answer. Just go for it and have fun.

Last month's Beautiful People session, I chose to do my main character from Adamantine, Adamant. This month, Andor is going to get the limelight.

Andor

1. What type of laugh does he have?

Andor has a wide range of ecstatic noises, but most typically he employs a bark or a tiger type of purr.

2. Who is his best friend?

Andor is a free-spirited fellow, and generally charitable toward all, especially if you will feed him. He is one with Adamant, however, practically her inseparable shadow; he adores her without scruple. She is, unequivocally, the world to him.

3. What is his/her family like?

Originally a gargoyle, a mere carving of stone, Andor has no family, no connections, no background, nothing. He is the closest one can get to really coming out from under a rock.

4. Is he/she a Christian, or will he/she eventually find Jesus?

As an animal, Andor has no real conception of justification and sanctification, and no need of either. He appears to have some inkling of an idea that a relationship between people and God is important, but he has no need of a personal one himself.

5. Does he believe in fairies?

It depends on how you want to define "believe." As a genial soul, Andor is willing to like just about anyone who responds with a friendly attitude, whether that person be human, Catti, or fairy. Being an animal, Andor doesn't question the existence or non-existence of people. Fairies simply are.

6. Does he like hedgehogs?

Andor has never met a hedgehog, and having still, perhaps, some mortar between his ears, that is probably just as well. It would be unwise for Andor to attempt to make a snack out of a hedgehog.

7. Favorite kind of weather?

Andor likes full sun for bathing in, but a cool breeze to keep the temperature pleasing. He dislikes rain, even though he has a decently thick coat, and sleet is unbearable. Snow in moderation is enjoyable.

8. Does he have a good sense of humor? If so what kind? (Slapstick, wit, sarcasm, etc.?)

Andor doesn't really have much of a sense of humour or ill-humour to himself. His moods change in relation to Adamant's emotions and in relation to the circumstances. He does, however, feel these emotions in extreme: Adamant's contentment produces in him an almost immovable sense of peacefulness, and her anger or fear inspires in him a tempestuous rage.

9. How did he do in school, or any kind of education they might have had?

Andor has never gone to school. Despite the mortar between his ears, he is not an unintelligent chap, as far as animals go. Indeed, given his hideous appearance, showing up in a schoolroom setting would probably cause an almighty ruckus.

10. Any strange hobbies?

Not as such. Andor is very particular about washing his face, which must be done in cat and rabbit fashion by first licking his forepaws and running his forepaws over his face, but otherwise he has no hobbies to speak of.

May 17, 2011

"Yes," He Said. "Pray For Me."

excerpt from Adamantine

excerpt from AdamantineWhere the stonework was crumbled down along the side of the road the four of them got off, making their way through the frosty grass and autumn's leaves to the red splendour of the alders which hung over the turbulent river. The river was very loud in the quiet, and swollen with the sun that had been all day on the snows in the mountains. Andor went ahead of them down to the thicket, startling four rabbits turning to their white winter coats; he broke off the chase them upstream.

Eikin had one eye on the dog as they dismounted and unpacked. "I miss a fight," he admitted in an undertone to Adamant. "Sometimes I feel as if I just need a good fight and then I will be well again. It's the black forest in my restless blood."

Adamant looked from the Catti's face to the red-flushed dark boughs of the alders overhead. There were several tawny birds up there, flickering against the gold of the sky, and breaking up the winter's ploughland quiet which tried to mingle with the river's rushing. There was something, she thought, to that black forest restlessness: Eikin always seemed lingering just on the brink of an odd tingling feeling, like that chiff-chaff: merely waiting for the right moment to bound free into flight. She only hoped it would not be Rhodri who provided the means of Eikin letting loose his pent-up tremors.

She left him to see to the animals and joined Rhodri with the medical kit. The fairy had got down off his roan, hobbled to a single curl of alder-root, and eased himself stiffly down, leaning wearily back against the bole of the tree. His recumbent posture was submissive, though he watched her almost warily out of the corner of his eye; nevertheless she felt awkward as she sat down tailor-fashion with the kit by her side.

Rhodri extended his foot into her lap, settling the heel in the crook her crossed ankles made. "Is that all right?" he asked.

"Yes. Just a moment and I'll have your shoe off." She undid the lacing and wiggled the boot free. Rhodri's stone face never changed during the ordeal, but Adamant could sense the pain her movement was causing him. At last the boot came free, revealing the rumpled stocking beneath. This Adamant gently peeled off and hung over a stone to be washed later. She saw at once that the foot was in a sorry state. It was not crooked or disjoined from the ankle, but it still had a tinge of dead white to it and it looked weak. "Oh, the poor thing," Adamant whispered instinctively. She opened a salve and spread it over the arch and heel.

"That is cold," Rhodri remarked dryly.

"I am sorry," replied Adamant. She began to rhythmically rub the salve into his foot while pressing out the ache along the mangled foot and calf. Andor returned, a big tawny shadow trotting through the snowy brake, and pitched himself down at Rhodri's head, panting softly. Behind them, adding to the river's rush and the frenetic murmuring of the birds, the roan stamped and Kielk shifted disconsolately while Eikin made a small fire.

Rhodri shifted, putting his head against Andor's flank. "You have nice hands," he murmured. "I should much prefer to be strangled by yours than by Eikin's."

Surprised, Adamant paused. "Why would I strangle you?" she inquired. "What a silly idea."

"Silly idea," Eikin confirmed from where he squatted, coaxing the flames. "I'd run you through with my framea before ever I touched you."

Adamant frowned at the Catti. She went to protest that there was nothing wrong with strangling Rhodri with one's bare hands, then thought perhaps that was not what she meant. But Rhodri said nothing, and presently Eikin slung the waterskin over his shoulder and set off for the riverbank. She turned her back on him and continued rubbing Rhodri's foot. The fairy had his eyes partially shut, idly watching the swing of her pendant. As the sounds of Eikin's footsteps died off in yesteryear's bracken, the only noises were Andor licking his paws and Adamant's own softly laboured breathing.

She thought at first that Rhodri would say something, but realized that he never did what was expected of him, so she resigned herself to the silence while thinking of a one-sided conversation to begin. They never seemed to go well with Rhodri, not any subject, and when it came to the point words threatened to fail her under the bitter, dying grey gaze he gave. Suddenly a thought came into her head.

Could you love Rhodri? He needs love badly. Could you be the one to love him?

She was a little taken aback by the question her mind had made. Her hands slowed as she observed the fairy's face from under the windward brush of her hair. He was watching the chill breeze play in Andor's fur, ruffling it into a brindled crest along his spine, and there was that uncuriousness in his countenance, that windowpane-greyness as though he gazed from nothing upon nothing. And then she knew the answer very clearly. No, she could not be the one—certainly not yet. He needed God more than anything else; he needed to know the depth of forgiveness God was capable of reaching and the freedom from all misery which only the Holy Spirit could acheive. She recalled, with a sense of expectant joy, the morning Rhodri had interrupted her thoughts and finished what her Stone had been telling her:

How lovely upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings, that publisheth peace… and brings good news of happiness, who announces salvation, and says to Zion, 'Your God reigns!'

"You stopped."

Adamant raised her head. Rhodri had propped himself up on his elbow and was staring at her quizzically. The wind stirred his blue hair, making the silver highlights twinkle in the last of the winter sunlight. She twisted her mouth into a smile to hide her blush. "I was…praying for you," she said, in all honesty.

She expected him to ridicule her, but he said nothing. He dropped his eyes and plucked a stem of grass from the ground, rubbing it cruelly between his fingers. "Yes," he said finally. "Pray for me. Pray I live forever. Pray I never die and face God. Pray he forgets I exist and what I've done and all I want to do." His voice broke and he left off, flinging one arm over his face so she could not see him.

She knew then that she ought to leave him. Andor would be with him and, despite their dysfunctional beginning, Andor had come to adore Rhodri. So she rose, cast the corner of Rhodri's cloak over the withered bare foot, and walked off to join Eikin at the river and to wash the socks.

Eikin was just finishing filling the waterskin as she descended the bank. "Do you have it?" he asked.

It took her a moment to understand him. "Andor has it," she replied, and skirted him to kneel on a slab of rock over the water.

The little redwings played in the trees as Adamant began to work the grime from a woollen sock. Eikin, suddenly reluctant to leave, stood on the crest of the rock behind her, the dim light and wind obscuring the tawniness and brownness of his fur into a single blur.

"I hope his foot heals," the Catti said at last, breaking the silence. "I mind that you have to tend it."

"Yes, perhaps I mind as well," said Adamant, hoping to be agreeable. "But I oughtn't mind." She paused in her work and looked up at him. The red shadows of the trees made the hazel of his eyes look brown. "One day you'll realize that Rhodri has had a very, very hard time, much worse than even your people under the fairies."

Eikin's countenance was fixed and cold. "If you were a man," he said, "I would send you into the river with my fist."

Doomed to be disagreeable on the subject of the fairy, Adamant could only shake her head and rub her hand across her nose, for the cold made it run. "Don't be so proud, Eikin," she begged. "We've had this talk before. Imogin wouldn't like it."

"Even Imogin didn't like Rhodri."

"Maybe she disliked him, but only because he was being disagreeable. You still hate him. And, Eikin, you said you wouldn't." She shook the stocking hard. "Don't break your promises."

Eikin ran his claws through his hair and emitted a heavy sigh. "It is not," he said wearily, "on mere account that he is a fairy. It is on account of the fact that you are so beautiful and he can see that. One day—"

"There won't be a 'one day'," Adamant assured him hurriedly. "Trust me on that. Sometimes I think he is even more sinned against than sinning. He wants to try to come out, but every time he even gets close, you—you chase him back down the hole!"

Eikin remained silent, gazing back at her with such grim reproach that she felt her resolve waver a moment. What if—what if he was right? What if she had recoiled from Charles Demon only to stumble headlong into another mistake? But in the next instant she had hammered down the fear, jerking back around to scrub ruthlessly at the sock. She could not be wrong. The frankness, the undercurrent of fear—she could not believe that Rhodri had conjured them merely to deceive her.

"You doubt yourself."

"No," she replied, pursing her lips. She kept herself quiet for a count of ten before continuing. "Rhodri Fairy is ten times more intelligent than the two of us combined. He should have been a military general, not an orderly! I don't know why God gave him such a small body, but there is so much inside him: there is potential under that rage, Eikin."

He shook his head slowly—but almost, she thought, admittingly—with the light jinking green and brown and gold in his eyes. "How can you see this?" he asked.

Adamant looked away from those eyes. The evening mists were settling on the heights of the foothills, turning to a golden shroud where the lights struck them: a golden place where heaven and earth came to mingle in the upland solitude. "Once a Catti boy commended me for my character. I didn't think, at the time, that what he said was true, but as time passes I think—I think he may have been right."

Eikin moved to her side and sat by her, hunched over, playing with one paw in the water. "It was Brogi, wasn't it?" he asked.

"That was his name, yes."

Eikin nodded. "A wise child, if ever there was one. Brogi," he added, "will be a seer one day. And because he spoke a high thing of you, I know it is true." He looked at her curiously, searchingly. The wind ruffled his fur and hair, whistling into his cupped ears. "It is so hard, Adamant. I do not want to do it. You have no idea how satisfying it feels to hate long and good and hard." His teeth glinted as he forced his words past them.

A little chilled, as if by premonition, Adamant objected, "Rhodri has never done you any bodily harm. Why are you so set on hating him?"

"Because of his character; and because of what his people are to mine. You cannot deny a person's heritage just on a whim; it is what makes them. You told me not to be so proud; it is not that simple! We Catti were born proud. It is who we are. The fairies were born with a domineering spirit, a desire to rule the world. It is who they are. You cannot nullify that just because you pity a person."

Adamant gave another compulsive sniff and pushed her hair behind her ear. "It's when a person is most broken that he can be put together again, Eikin. I don't know about you, but I have been praying for Rhodri. And I will keep praying for him. It's there, the faith, the truth—or it will be, I'm sure of it. Rhodri has a fear of God—"

"The demons fear God."

"—and he can, and I believe will, be brought back to the feet of God once more—if he was ever there before. Perhaps this will be the first real time. There was a time when Rhodri knew something of God."

Eikin frowned terribly. "How can you know that?"

Adamant touched her lips with her tongue. She could not say—she could not tell of the moment in the bedroom when Rhodri had faced the splendour of the sunshot, snowy dawn and had spoken the words of God. She could not say that he looked like the face of the ploughlands being gouged up for the spring sowing. It was a conviction she could not make tangible. She sighed and picked the sock up again. "I can feel it. When you are born afresh yourself, you can tell sometimes." She side-glanced Eikin's way. "Not all the time, but sometimes."

Eikin merely grunted, and she heard and felt the weight of his disapproval in his tone. His tone, his steadfast disapproval, her sudden bone-weariness and desperation, and everything on top of finding Wiglaf suddenly pressed down upon her, and without really realizing what was happening the world had become a red-gold, brown-shadowed blur and she had clamped her hands over her mouth to stifle the onrush of sobs. The Catti said nothing, but reached over and gripped her forearm hard, which hurt, and steadied her a little. The tears gushed out all at once and soon subsided; she would have a bruise, she thought, on her forearm after she had just healed the bruise on her upper arm. At that thought the tears sputtered out in a shaky, self-depricating laugh, and she wished she had a pocket handkerchief. The reflection that flickered back up at her in the iron-dark water, spangled with the light that was still lingering in the sky, was clouded and unlovely.

"I think Rhodri was right in one thing," Eikin remarked, when she had finally fallen silent again. "You are too good for what this world can give. Too good for us."

Adamant pushed the corner of her wrist under her nose, sniffing violently. "It's not me—"

"It is you," retorted Eikin. "It is the you that—it is the real you. The you that God is making. Even in your blindness you and Andor both shame us with your loyalty, your unquestioning faith—"

"Oh, I question, Eikin," Adamant broke in. "My faith is so small."

"And mine seems unborn," Eikin growled. He let go of her arm. "More often than not I want to kill Rhodri. I want to spill his blood at my feet and the thought is a sweet, good thought to me." He curled his paw closed and watched the curl of it and the way the last light struck the points of his claws to pricks of fire. "And when I see your compassion I lash out at you. I know I hate, but I do not want to change. I love my hate. It is sweet in my mouth."

Adamant sighed. "I know what you mean. But Eikin—"

"No," the Catti said sternly, rising. The wind kicked up his cloak as he stood over the riverbank, eyes set in hard, glittering lines. "If I sort this out, I will sort this out myself. I won't kill Rhodri, I swear that. It may take me a lifetime to work out my hatred, but I won't kill him."

It was all she could ask for, and she was appreciative of that. She nodded, wordless.

He seemed almost on the brink of going, but looked back down at her, ears pricked into the wind. How wild and handsome he looked, Adamant thought, standing firm with the world all around him, a world he did not care about, a world which could not touch him. "Adamant," he said, slow and thoughtful, and with a voice far-off, "while you pray for Rhodri, if you remember, mention my name as well."

"Yes, Eikin. I will."

[Edit: for those of you who might have missed it (though it is probably unlikely) here is my list of cast, mostly with illustrations.]

May 11, 2011

Jenny vs. Writer's Block

Goodness gracious, the late Cretaceous. Writer's block. It haunts us all, lurking round the corner, behind the coffee maker, under the sofa, behind our computer monitors, at the damp bottom of our empty coffee and tea mugs. Writer's block. The very name of it strikes dread in my heart, and I begin the descent through the various stages of grief.

Denial: I'm only briefly stuck. This can't be happening. This isn't really writer's block. It will pass if I can just finish this one sentence.

Anger: Augh, why can't I think of something to write? I was doing brilliantly before! I was a shooting star! I was awesome! I was so on a roll! And now I can't think of a simple way to end this sentence!

Bargaining: Look, look, character... Just...work with me here, okay? You and I, we've got a beautiful friendship in the making. All I need is to finish this sentence. That's all I'm asking. Just the sentence. Maybe if you're feeling up to it, we can even finish the chapter. But, for now, just the sentence.

Depression: You know what? Fine. I don't care. It's a dumb sentence anyway. This whole chapter is dumb. In fact, the book might be all dumbness. I don't know why I even started this chapter in the first place. I'm a horrible writer.

Acceptance: Yep. This is writer's block.

Yep. This is writer's block. I don't think that there is anything you can do to prevent writer's block any more than you can prevent death and taxes. You simply can't keep the creative faucet running full blast all the time. If you could, you might go mad. I don't know about you, but I have felt creatively exhausted: whatever part of me it is that vibrates to the nearly constant thrum of creativity roiling in my mind is just worn out. Sometimes writer's block comes in the mere mundane coarse of things: you want to go on, you're willing to go on, you're waiting to go on, but nothing if flowing. On other occasions, the sheer activity of imagination is just so overwhelming that you can't go on. You need a break.

What do you do when you need a break? If you're anything like myself (and I do apologize in advance if you are) it's almost impossible to stop the hum-thrum in your mind. Everything around you, your very existence, plays on your imagination like a bard on harp-strings. It just won't stop. So here, before I get to the mundane writer's block, I will set down a few hopefully helpful things to do when your creativity is completely fagged.

1. The God of peace.

In the midst of all the crazy whirling-dervishness of my imagination, I have an unwavering true north to orient myself to. Though the depth of him is incomprehensible, the straightness, the steadfastness, the constancy of my God is something I can fix my mind on, dwell on, dwell within, move within, and find all peace within. All my ideas, all my dreams, all my bright firework-flashes of imagination dim in comparison to the steady light of Christ. When I'm just worn out, when my own mind has beaten me to a greasy patch on the ground, there is a steadiness in Christ to rest myself on, an arbor on the long road to Heaven under which I can take my rest.

2. Music.

Everybody knows that David played to soothe Saul's restless spirit. Find a David, find something soothing to listen to. I know oodles and bunches of you like putting together music lists to help you write. Try doing the same thing, but for the opposite reason. Find some music that cradles your poor battered psyche like fuzzy socks cradling cold toes.

3. Sun bathe.

Again, if you are like me, the sun has a way of dazing and quietening you. Find a warm patch out in the fresh air and just sit. Sit on a blanket, if you like, or take a cat-nap on one in the sun. Fresh air, warm sun, a pleasant solitude, is just what a worn soul needs sometimes.

4. A little story.

If there is nothing else to be done, hand your imagination over to someone else to handle. Find a well-loved story - it needn't be a big one - and let its familiarity and beloved nature carry yourself off. T

he very fact that you have heard it a hundred times, and possibly know it by heart, is perfect. For comfort and rejuvenation, I go back and read The Silver Branch. In a while I may have the whole thing known by heart, but still I like to lose myself in the comfortable familiarity of the words, no longer needing to key myself up to pay close attention to what happens next, merely wandering through a dream which I have dreamt so many times that I know my way through with my eyes closed. It's relaxing.

he very fact that you have heard it a hundred times, and possibly know it by heart, is perfect. For comfort and rejuvenation, I go back and read The Silver Branch. In a while I may have the whole thing known by heart, but still I like to lose myself in the comfortable familiarity of the words, no longer needing to key myself up to pay close attention to what happens next, merely wandering through a dream which I have dreamt so many times that I know my way through with my eyes closed. It's relaxing.Everyone understands that you can't keep pushing on and on and not expect a backlash of exhaustion. Your mind is the same way. Take a break. Take a break, even, before you reach the limp noodle stage. The world isn't going to implode if you shove the keyboard in,

close the notebook, and put the pencil down for a spell. Running yourself ragged isn't going to help you make excellent literature. Sometimes writer's block comes around because, quite frankly, you need it.

close the notebook, and put the pencil down for a spell. Running yourself ragged isn't going to help you make excellent literature. Sometimes writer's block comes around because, quite frankly, you need it.But what about the common, bad-penny, unwelcome writer's block? What do you do about that? I'm not going to reproduce it here, because that would be silly: Liz began by making a very nice post on what she does to combat writer's block, which I would highly recommend you take a peek at. As for myself, here is what I do to make my writer's block go away.

1. Reread.

When I'm afraid the spirit of the story is slipping through my grasping fingers, I go back and read passages I have already written. Even though my creativity isn't moving forward, it is at least churning over ground that I would like to continue ploughing. I prefer to reread the passages I think were particularly brilliant, which always helps me self-esteem.

2. Fill in the gaps.

Every story has to have gaps. No one wants to read every little detail of every thing that happens to your characters. But no one says you can't fill them in for your own amusement. I thought up a whole new section to replace a bad one in Adamantine because I found myself piddling through writer's block and making up stories about what happens to my characters after the story closes. If your creative juices don't want to go the way you want them to, divert them back around by Clever Means. It doesn't have to be serious at all. It can be a mere conversation between characters, just a little something which might jump-start your imagination the way you want it to go.

He held his hand out to indicate Roman's height. "Roman was about two at the time, and a very precocious lad. We had all the folk out to shearing, and with that many people we all assumed someone was watching him. But the next thing we know, Aventine is screaming - screaming bloody murder - and we all look up to see Roman with a sheep's ear in one hand, and a pair of shears held up in the other, for all the world going to slaughter that thing. We were yelling and screaming, and trying to stop him. We had no idea what had got into his head - neither did the sheep, who was looking very askance about the whole thing. It turns out, he had been listening to Aventine's history studies on the old pagan religions, and he wanted to see if he could sacrifice a sheep too. Poor thing." He shook his head, laughing wryly with the summer sun laughing with him in the golden splash of his wine. "Roman was heart-broken that he didn't get to carry through."

3. Music.

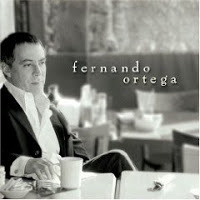

Music, of course! Now, I don't usually need a specific genre, or tune, to help me get into the mood, but I know a lot of people do. I can put on Escala's Palladio and be happy as a clam writing a quiet nighttime scene. But when I need atmosphere, I enjoy some of Heather Dale's pieces, and there is almost always some song by Fernando Ortega to fit the situation. There are billions of songs out there, one or two or several just waiting to be picked up and listened to, to further your story.

4. Comfort food.

This is, perhaps, a bad habit. I find food very comforting, and as I am currently equipped with a decent metabolism and a routine walk, I can nibble as I write without much danger. Excessive thinking, epic journeying, close shaves, sudden glorious vistas - these sorts of things require a satisfied appetite to pull off, you know. If possible, make what you particularly like, and eat that. Or drink it, if you're a liquid sort of person. I indulge in tea most excessively. I find it soothing and familiar, and it helps me focus.

5. Stare at the computer screen.

Yes, yes, this is what I do. I stare. I stare hard. I stare with feeling. And, while I do so, I divest my mind of everything but the immediate scene and walk about in it, observing my characters closely to determine how A must lead to B must lead to C. You will be surprised how often C will wildly dive off into M which leads to a magnificent E, which escalates into W, which becomes the best piece of writing you have ever made. Just stare. Cats do it all the time, and everyone knows that cats are brilliant.

Except mine.

6. Read prolifically.

I have very good intentions of doing this. I always have one or two or more books going at once, and I do read them, but I can't say I read prolifically. I read far too slowly for that. Nevertheless, the best place to get ideas is to go and look at other people's ideas. I'm afraid there is no use in worrying about trying to be original. We like to joke about good artists stealing from others, but the fact is...it's true. Some are giants, and some of us see far because we stand on the shoulders of those giants. There is a vast body of literature, of the written prying minds of men, just waiting for you to plunge in. Maybe I'm still sitting on the edge kicking my feet in the water, but it's done me good so far.

"Even in literature and art, no man who bothers about originality will ever be original: whereas if you simply try to tell the truth (without caring twopence how often it has been told before) you will, nine times out of ten, become original without ever having noticed it." C.S. Lewis

7. Be a child.

Everyone has to grow up. Everyone has to mature mentally and spiritually, and I will most heartily disagree with anyone who would presume to say otherwise. Yet there is, as George MacDonald pointed out in his writing, a difference between the childish and the child-like. C.S. Lewis, too, knew this, much as he did not get on with children. Children see the intrinsic magic of the world as adults so frequently do not, uncluttered as they are by cares and worries and responsibilities. There is nothing wrong with responsibilities, though Christ tells us precisely what to do with cares and worries. So be child-like sometimes! Don't be afraid to step outside and look at the butterfly on the lawn and think, "What would I think - what would my character think - of that? Is it pretty? Is it majestic? What is it like?" And just run wild. Frolic. That's it, positively frolic. Let your imagination just wheel through a starry field of dandelions and something pertinent is bound to be tripped over.

May 9, 2011

Noonday Devil

Why is it that things always dawn on us while we are taking our showers? What is the magical property of combined warm water, steam, mellow light, and fragrant soap which settles us into a more contemplative plane of consciousness?

Why is it that things always dawn on us while we are taking our showers? What is the magical property of combined warm water, steam, mellow light, and fragrant soap which settles us into a more contemplative plane of consciousness?Yes, yes, I don't know either.

I like to sing in the shower, and when I'm not singing, I like to put a CD on and listen to that. So this evening as I took my ritual cleansing I had Fernando Ortega's CD (very inventive title) "Fernando Ortega" playing in my lovely purple Sony CD-player on the counter. I was anxiously awaiting my most favourite song on that album to come on: "Noonday Devil." I am not sure why it is my most favourite song; I never ask myself such questions. Nevertheless, in the due course of time, on it came, and with a good will I began singing along.

I know there's hope in anger

And tenderness in shame

Sometimes I find you

On the other side of pain

But I had been editing Adamantine just this evening before supper, and as I listened to "Noonday Devil," something clicked. In the course of the story, our intrepid heroine finds herself in just such a situation as Mr Ortega sings of in his song.

In my hour of hopelessness

In my deep despair

The noonday devil whispers in my ear

I know that you are with me

But I can't feel a thing

The noonday devil

Has come around again

I was struck with the similarity. If Mr Ortega had been leaning over my shoulder as I had written up that section, he could not have made a song more like what I had been thinking. The hopelessness, the deep despair, the noonday devil whispering in her ear... Song and story came together in one wet moment in the shower. The song summed the whole passage up beautifully: the despair, the plea, the acknowledgment of human weakness in the face of darkness and the dependence upon the Holy Spirit to charge a human soul with greater fire.

Oh, Lord, make me angry

Oh, Lord, make me cry

Oh, Lord, please don't leave me here

To fall into the devil's lies

Our intrepid heroine did not think of all this at the time. I doubt that either you or I would have, though God's grace is sufficient. But she saw it later, and a truth missed at the time is still a truth. Sometimes we do find him on the other side of pain. Sometimes we must be made angry, sometimes we must be made to cry; sometimes our cold, cold hearts must be broken to know the sufficiency of God's grace and his love. What agonies we must endure sometimes, what close shaves, what long dark nights and blazing empty deserts, what sufferings of Christ we must bear up under to find him, to be like him, to become as he would have us.

But there is a hope in anger, and a tenderness in shame. There is a small but very beautiful poem by John Milton which, after some contemplation, I think takes Mr Ortega's song to the next level.

Is it true, O Christ in Heaven, that the highest suffer most?

That the strongest wander furthest and most hopelessly are lost?

That the mark of rank in nature is capacity for pain?

That the anguish of the singer makes the sweetness of the strain?

The person who comes out on the other side of pain, held up knowingly or unknowingly by the hand of God, is not the same person who was plunged into it at the beginning. Adamant learns this, in herself and in her friends: they are not the same: they have gone further up and further in. Bunyan makes a point of depicting the highway to Heaven as being a narrow one, a rough one, fraught with difficulty. But blessed is the man, the Psalmist says, in whose heart are the highways to Zion. There will be pain and the devil's lies along the way, of that we can be sure. Sometimes the monsters pull us under; but there we may find a sword on the wall (you know your Beowulf?), and the anger to wield it, and the grace with which to receive grace. It's a truth: it even gets into our stories. And sometimes our stories understand this better than we do ourselves. Sometimes the truth slips out at us through our own unwitting words, in a line of poetry, in a water-spangled piece of song. He has given us grace for grace, and inscribed a circle on the surface of the waters between dark and light. Sometimes I find him on the other side of pain. Sometimes I find him when

the noonday devil whispers in my ear

Mayhap I will learn a thing or two, between Adamant and Ortega and a shower.

Oh, Lord, make me angry

Oh, Lord, make me cry

Oh, Lord, break my cold, cold heart

So I can know your love inside

Your love inside

May 7, 2011

The Shadow Things Book Review

I am pleased to announce to the inquiring public that Miss Black on her book review blog Little Notes has read and reviewed my book The Shadow Things and put up the review for you to read. It would be a delight to me, and a real honour to her, if you might stop on by and take a look. Miss Black does a thorough combing-over of her books; I think you will enjoy the experience.

I am pleased to announce to the inquiring public that Miss Black on her book review blog Little Notes has read and reviewed my book The Shadow Things and put up the review for you to read. It would be a delight to me, and a real honour to her, if you might stop on by and take a look. Miss Black does a thorough combing-over of her books; I think you will enjoy the experience.excerpt from review

There are several threads and themes running through this novel, but my favorite, and the one that is the source of the book's title, is the idea that all we see in God's creation - the beauty and wonder and magnificence - is but a shadow of it's former self, a faint dream of things to come. This message in particular really spoke to me.

For those fellow authors who also want books reviewed and the word spread out, a line by email to Miss Black would probably not go amiss (I'm thinking of you, Liz!). May you live long, and may your pens never run dry!

Other places to find The Shadow Things reviews:

Genre Reviews by Debbie White

Amazon

Goodreads

May 4, 2011

Adamantine - Inklight

Miss Adamant Firethorne

Miss Adamant FirethorneMiss Adamant was born in London to an Italian father and an English mother in the Year of Our Lord 1826. It is a quiet, respectful, demure, naive seventeen-year-old which finds herself an orphan upon the death of her parents and going to live with her relatives in Cumbria. After a mutual dislike brews between herself and her cousins, Adamant is as much relieved as well as bewildered when she is mysteriously charged to recover the lost Dragon's Eye, a massive diamond, and to find as well as return the diamond to its rightful owner Wiglaf, heir of Beowulf. With absolutely no warning and very little preparation, Adamant is relocated clear out of her world into another to complete a task she knows nothing about with her life in God's hands and her feet taking her she does not quite know where.

Song: The Never-Ending Road, by Loreena McKennitt.

the road now leads onward as far as can be

winding lands and hedgerows in threes

by purple mountains and round every bend

all roads lead to you

there's no journey's end

Rhodri Fairy:

Rhodri Fairy:Don't let the appellation fool you. Though standing five feet, four i

nches tall, Rhodri is small among the fairy-kind. He was born in the Garden of Faerie, Kartusca, the lushest part of the fairy empire, but spent much of his life cheated out of what he wanted and wandering bitterly from place to place. He, like Adamant, was charged to find the Dragon's Eye, but upon failing and delivering it to impressive but evil powers Rhodri has spent goodness how long imprisoned in a kind of limbo. His naturally bitter disposition has since hardened into a decidedly sardonic demeanour, which makes his attention to and care for Adamant very awkward at times.

Song: I'm Still Here from the film "Treasure Planet."

and what do you think you'd ever say

I won't listen anyway

you don't know me

and I'll never be what you want me to be

Eikin Thrasirson, Catti:

Eikin Thrasirson, Catti:Eikin, a budding Catti warrior, was born and raised on the outskirts of the Faerie Empire and has not only heard the stories of fairy oppression of his people, but has seen it, and he bears no love for fairies of any size, shape, or colour. He is a fellow of firm but simple convictions, more prone to temper than tenderness, and it is with mixed feelings that he finds himself drawn into Adamant's task. As much as he cares for Adamant, he finds her continued belief in Rhodri to be trying and misguided at best, potentially dangerous for her honour at worst. He and the fairy spend much of the time circling each other and spitting like cats.

Song: The Boxer by Carbon Leaf.

couldn't ask for a better night, two by two

to the ring to the right point of view

we each retreat to the corner that's defined by you

to the ring to the right point of...

no return, no passion left to burn

the boxers grow weary

their eyesight blurry, blurry view

Kiaralinn Fairy:

Kiaralinn Fairy:If a beam of sunshine could be made into a person, that person would be Kiaralinn. The fairy girl was born and raised on the northern coast of Faerie, living a rural, carefree life among her friends and family. But providence ordains to throw her in with a strange human girl, a Catti, and a handsome taciturn fairy gentleman, and her naturally bubbly, naive disposition is something new to the mix. She finds a quiet but appreciative womanly companion in Adamant, as well as the fact that adventures are perhaps not nearly as enjoyable as she had believed them to be.

Song: The Star of the County Down.

down a boreen green came a sweet colleen

and she smiled as she passed me by

she looked so sweet from her two white feet

to the sheen of her nut-brown hair

such a coaxing elf, I'd to shake myself

to be sure I was standing there

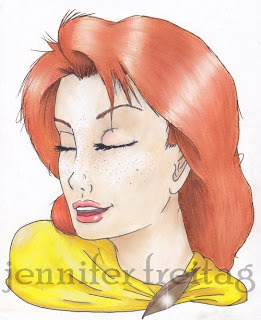

Morgan Fairy:

Morgan Fairy:As one fairy pointed out, she needs no surname. As cunning as she is enchanting, the ginger aristocrat is quick enough to ascertain the real purpose of the odd trio her stepsister has sent her way. Ambitious enough to make Agrippina the Younger impressed, Morgan plies every bit of conjuring she has on the group in an effort to steal a prize worth worlds.

Song: The Music of the Night from the score of "The Phantom of the Opera."

floating, falling, sweet intoxication

touch me, trust me, savor each sensation

let the dream begin, let your darker side give in

to the power of the music that I write

to the power of the music of the night

Wiglaf:

Anyone who has read to the end of Beowulf's story will recall Wiglaf as the young man who stuck by his Geat lord to the bitter end. He was Beowulf's heir and, at Beowulf's death, was to assume the Geat throne, but such a man as Beowulf produced enemies as well as allies in his lifetime, and at Geatland's most crippled hour disaster struck, Wiglaf was captured, the Dragon's Eye lost, and the world went on sadly, time out of mind, with the heir goodness alone knew where, and the enemies of Beowulf continually on the look-out for the fabled Dragon's Eye, each year bringing them a little closer to their objective. But every spell must be made so that it can be broken, and the young heir sleeps with the hope that his rescuers will reach him before his time runs out.

Song: Brother, Stand Beside Me by Heather Dale

brother, stand beside me - brother, lend your arm

brother, stand beside me - brother, lend your arm

see the weakness in the world

and choose to be strong

let them sing our praises when we've gone

The Pooka:

Pookas are ancient shape-shifting creatures, preferring either goat-shapes or horse-shapes, but capable of whatever shape they wish. Sometimes interested in the pursuits of its evil fellow, sometimes out for its own amusement, a single pooka dogs Adamant all along the way, becoming more and more infatuated with her as time progresses.

Song: When the Coyote Comes by Fernando Ortega

walking down the road, sniffing as he goes

an old coyote - his eyes are yellow green

trickster on the prowl throws back his head and howls

oh, the night heats up with the coyote comes

he won't rest till his work is done

critters flee when he comes around

some won't make it home

Andor the Gargoyle:

Andor is a hideous, doggish, loyally fanged creature, originally a gargoyle and magicked to life. He has attached himself to Adamant and she considers him her pet. He has nothing but his natural geniality to recommend him, as his misshapen qualities lend him an almost unforgivably unlovely appearance. He is, however, an irrational, animal version of Kiaralinn's sunshine personality, and his fangs as well as his furry warmth prove useful on more than one occasion.

Song: The Artistry of Change by Sparrow.

an instrumental

Many thanks go out to the rest of my folk: Fallows Dray, Sebastian, Axin, Teik, Imogin, Charles, the Coventry cousins, the Raven King, the Windress, and for the special appearance of Auberon - and, of course, to Beowulf, without whom this whole story would be meaningless. They all look forward to meeting you properly some day. God bless us all, everyone!

I apologize that not everyone got a picture. All pictures are done by me and belong to me, so please, respect my property and look, but don't touch, as our mothers always told us.

April 23, 2011

Who For the Joy Set Before Him...

love lustres at calvary

My Father,