Andy Worthington's Blog, page 37

April 30, 2018

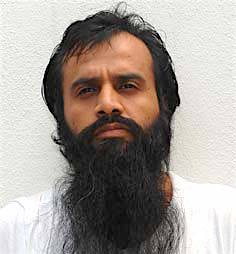

Ali Al-Marri, Held and Tortured on US Soil, Accuses FBI Agents of Involvement in His Torture

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

On Thursday April 26, in Amsterdam, Ali al-Marri, one of only three men held and tortured as an “enemy combatant” on the US mainland in the wake of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, spoke for the first time publicly, since his release in 2015, about his long ordeal in US custody, and launched a report about his imprisonment as an “enemy combatant,” implicating several FBI agents and stating that he is an innocent man, who only pleaded guilty to providing material support to terrorism in May 2009 because he could see no other way to be released and reunited with his family in Qatar.

Primarily through a case analysis of 35,000 pages of official US documents, secured through Freedom of Information legislation, al-Marri, supported by the British NGO CAGE and his long-standing US lawyer, Andy Savage, accuses several named FBI agents, and other US government representatives, of specific involvement in his torture. The generally-accepted narrative regarding US torture post-9/11 is that it was undertaken by the CIA (and, at Guantánamo, largely by military contractors), while the FBI refused to be engaged in it. Al-Marri, however, alleges that FBI agents Ali Soufan and Nicholas Zambeck, Department of Defense interrogator Lt. Col. Jose Ramos, someone called Russell Lawson, regarded as having had “a senior role in managing [his] torture,” and two others, Jacqualine McGuire and I. Kalous, were implicated in his torture.

Al-Marri’s story is well-known to those who have studied closely the US’s various aberrations from the norms of detention and prisoner treatment in the wake of the 9/11 attacks — at Guantánamo, in CIA-run “black sites,” in proxy prisons run by other governments’ security services, and, for al-Marri, and the US citizens Jose Padilla and Yasser Hamdi, on US soil — but it is a sad truth that the majority of Americans have not heard of him.

The torture of Ali al-Marri

Al-Marri had arrived in the US the day before the 9/11 attacks, to pursue post-graduate studies. He brought his wife and five children with him, and was registered as a legal US resident. In December 2001, as I explained in The Last US Enemy Combatant: The Shocking Story of Ali al-Marri, an article I wrote in December 2008, “he was arrested at his home by the FBI, and taken to the maximum security Special Housing Unit at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York, where he was held in solitary confinement as a material witness in the investigation into the 9/11 attacks.”

As I also explained in my December 2008 article:

In February 2003, al-Marri was charged with credit card fraud, identity theft, making false statements to the FBI, and making a false statement on a bank application, and was moved back to a federal jail in Peoria, but on June 23, 2003, a month before he was due to stand trial, the charges were suddenly dropped when President Bush declared that he was an “enemy combatant,” who was “closely associated” with al-Qaeda, and had “engaged in conduct that constituted hostile and war-like acts, including conduct in preparation for acts of international terrorism.” Also asserting that he possessed “intelligence,” which “would aid US efforts to prevent attacks by al-Qaeda,” the President ordered al-Marri to be surrendered to the custody of the Defense Department, and transported to the Consolidated Naval Brig in Charleston, South Carolina.

Al-Marri had already been held for 18 months, and had suffered in the Metropolitan Correction Center, where, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, Muslim immigrants — 762 of the 1,200 men in total who were rounded up for investigation — were subjected to physical and verbal abuse, held in conditions of confinement that were “unduly harsh,” and often denied basic legal rights and religious privileges, according to a 2003 report by the Justice Department. However, his ordeal began in earnest at the brig.

As was … revealed through the disclosure of military documents following a Freedom of Information request (PDF), al-Marri, along with two American citizens also held as “enemy combatants” — Yaser Hamdi and Jose Padilla — was subjected to the same “Standard Operating Procedure” that was applied to prisoners at Guantánamo during its most brutal phase, from mid-2002 to mid-2004. This involved the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques,” including prolonged isolation, painful stress positions, exposure to extreme temperature, sleep deprivation, extreme sensory deprivation, and threats of violence and death.

Although the treatment of prisoners at Guantánamo was disturbingly harsh, it can be argued — with some confidence, I believe — that the treatment of al-Marri, Hamdi and Padilla was worse than that endured by the majority of the Guantánamo prisoners, as all three suffered in total isolation.

In May 2009, I wrote the following about the first 16 months of his imprisonment in the Charleston brig:

[T]he first 16 months that he spent as an “enemy combatant” took place in a state of almost unprecedented isolation, which, outside of the horrors endured by the “high-value detainees” in CIA custody, was shared only by the other two US “enemy combatants,” Yaser Hamdi and Jose Padilla, and a handful of prisoners in Guantánamo. His isolation was such that, according to a psychiatric assessment conducted on behalf of his lawyers, he began suffering from “severe damage to his mental and emotional well-being, including hypersensitivity to external stimuli, manic behavior, difficulty concentrating and thinking, obsessional thinking, difficulties with impulse control, difficulty sleeping, difficulty keeping track of time, and agitation.”

As his lawyers also explained in court documents filed last May [May 2008], during this period interrogators told him that “they would send him to Egypt or to Saudi Arabia to be tortured and sodomized and forced to watch as his wife was raped in front of him,” and threatened to make him “disappear so that no one would know where he was.” They also explained, “He was denied any contact with the world outside, including his family, his lawyers, and the Red Cross. All requests to see, speak to, or communicate with Mr. al-Marri were ignored or refused. Mr. al-Marri’s only regular human contact during that period was with government officials during interrogation sessions, or with guards when they delivered trays of food through a slot in his cell door, escorted him to the shower, or took him to a concrete cage for ‘recreation.’ The guards had duct tape over their name badges and did not speak to Mr. al-Marri except to give him orders.”

Even after al-Marri was granted access to counsel in October 2004, the conditions of his confinement “remained unbearably brutal and harsh,” as his lawyers described it, explaining how he “continued to be confined to a 9 by 6 foot cell,” and was “denied regular opportunity for exercise,” and also stated, “The single window in Mr. al-Marri’s cell remained darkened with an opaque covering that prevented Mr. al-Marri from seeing the outside world or knowing the time of day. His cell had only a sink, toilet and hardened (metal) bed affixed to the wall. Mr. al-Marri had no chair on which to sit and no blanket, pillow, or any other soft item inside his cell. For more than two years, Mr. al-Marri was denied a mattress, causing him discomfort and pain whenever he lay down.”

The lawyers added, “Mr. al-Marri was confined to his cell for 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for months at a time. Once Mr. al-Marri was forced to spend more than 20 days in his metal bed in his freezing cell, shivering under a thin, stiff ‘suicide blanket,’ unable even to stand because the floor was too cold and his socks and footwear had been taken away from him.”

As I explained in my December 2008 article, “As part of a deliberate policy of controlling almost every aspect of his life ‘to cause disorientation, discomfort, and despair,’ al-Marri continued to be deprived of all external stimuli — he had no access to books, newspapers, magazines, TV or radio — and began showing evidence of … mental collapse.”

I also noted, “His conditions of confinement improved after August 2005, when his lawyers first filed a formal complaint about his treatment,” and they noted in May 2008 that he was “permitted to move about his cell block” (although he was the only prisoner there) and was “given adequate time for recreation.” He was also “in regular contact with his family by telephone, although his first phone call was not allowed until April 29, 2008, and was only arranged after his lawyers discovered that his father had died.”

When President Obama took office, he moved immediately to resolve al-Marri’s case, as the last outstanding US “enemy combatant” case. Yaser Hamdi, a US citizen who had moved with his family to Saudi Arabia when he was a child, had been seized in Afghanistan and was held at Guantánamo until the authorities realized that he was a US citizen, when he was moved to the brig, where he spent over two years before being returned to Saudi Arabia in August 2004, after renouncing his citizenship. Jose Padilla, meanwhile, initially seized in connection with a non-existent “dirty bomb” plot, was transferred into the federal court system in 2005, and, after a trial, given a 17-year sentence in January 2008, punitively increased to 21 years in 2014. His ordeal, however, seems to have effectively destroyed him, According to the psychiatrist Dr. Angela Hegarty, who spent 22 hours with him in 2006, “What happened at the brig was essentially the destruction of a human being’s mind.”

Al-Marri pleaded guilty to material support in May 2009, and was given a 15-year sentence in November 2009, with the judge accepting defense requests for his previous imprisonment to count as time served. He was released in January 2015.

The new report

Documents recording the torture of al-Marri, Padilla and Hamdi were first released many years ago, but as CAGE explain in their introduction to the new report, although logs from the brig “provide details about the actions taken against Ali al-Marri and the other men … largely it is unknown who is interrogating him when he leaves for interrogation sessions.” However, “The SHU [Secure Housing Unit] Visitation Log provides detailed dates, times and names of all those who were involved in meeting and interrogating Ali al-Marri,” and on one particular day, March 11, 2004, when al-Marri was “dry-boarded” – with socks stuffed down his throat and duct tape wrapped around his head — CAGE “was able to verify that the three interrogators logged into the prison” that day “were the FBI agents Ali Soufan and Nicholas Zambeck, and the Department of Defense interrogator Lt Col Jose Ramos.”

When the report was released, former Guantánamo prisoner Moazzam Begg, the outreach director for CAGE, said in , “Up until today US federal agents have insisted that they do not torture. However, during my incarceration, I was questioned by members of the FBI during every leg of my journey and threatened with rendition to Egypt or Syria in their presence, if I did not cooperate – an experience related to me by many others. Today, this evidence suggests that the FBI does in fact take part in systematic abuse. For this they, and the contractors that collaborate with them, must be held accountable.”

Andy Savage, al-Marri’s lawyer, after mentioning “the uproar about the use of torture at Guantánamo,” added, “Most Americans don’t realise that it also happened in their own country in Charleston, South Carolina. More specifically, that this torture was carried out by a rogue agent of the FBI, as proven from the prison logs.”

Ali al-Marri also spoke, telling CAGE, “Ali Soufan, one of the interrogators who abused me markets himself as an anti-torture advocate. This man continues to benefit from this label despite threatening me with rape, with kidnapping and torturing my family, and attempting to suffocate me so that I could confess falsely. I hope that this information leads to him, and the others involved in my torture, being brought to justice.”

Ali al-Marri speaks

Ali al-Marri also spoke to the Guardian, which noted that his “allegations of torture are supported by detention logs which are set to reignite the controversy over the US handling of al-Qaida suspects before the impending appointment as CIA director of Gina Haspel,” who ran a CIA “black site” in Thailand in 2002.

Remembering the events of September 11, 2001, al-Marri said that, as images of 9/11 appeared on the TV screen in the family’s hotel room, while his children were searching for the Cartoon Channel, “I had a sense. I rang the airline immediately – could we get home? But everything was grounded. I didn’t think al-Qaida could do it. In my hotel people were yelling at me. it was clear what was happening.”

He was arrested three months later after “he went to collect a trunk shipped from home,” and “the FBI were alerted,” and the Guardian noted how “FBI officers found an encyclopaedia bookmarked at US waterways, internet searches for toxic chemicals, and printouts of hundreds of American credit card numbers,” adding, “His claim to have come to the US to study was in doubt, as he had arrived two weeks late for the start of his course and 10 years after completing his first degree in the country.”

As the Guardian also noted, “FBI agents said he wanted to poison lakes with cyanide and disrupt the US banking system. They claimed he had visited al-Qaida training camps in Pakistan, and was in contact with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, mastermind of the 9/11 attacks.”

Now, however, al-Marri is challenging the perception of his guilt established by his plea deal. He “claims his encyclopaedia was bookmarked by his wife when she tidied his desk – ‘I was reading about the biggest lake, the longest river, I like these kind of facts’ – and says the chemical research was because he was considering importing chemicals from his brother-in-law’s Qatar company.” As he said, “It was not just cyanide, it was 200, 300 different chemicals.” He also claimed that the credit card numbers “were down to idle research on algorithms, while the trips to Pakistan were on business.”

“What is undisputed,” as the Guardian proceeded to explain, is his torture. Speaking of the “dry-boarding” experience, he said, “I was choking, I was dying. The suffering, you taste the pain, you taste it. Threatening to sodomise me, threatening to rape my wife, threatening to bring in my kids, that’s torture. Threatening to send me to a black site, to become a military lab rat, choking me to near death. This is torture.”

Responding to the fact that the log explains how his interrogators, “frustrated with his chanting of verses from the Qur’an, had taped his mouth,” al-Marri said, “I knew I had no rights, I was down the rabbit hole. It was dark times. My cell was six steps one way and, to lay down the other way, I’d have to bend my knees. I cannot see if it’s day or night. I felt as though I was buried in a concrete grave. I know the Americans were angry, but that gave them no right to treat me like that. In times of test your morals and values should not change. Unfortunately, at that time you were guilty until proven innocent – all the bragging about American justice and American constitution, all this goes out of the window. My thought was they will shoot me, hang me.”

He also said, “Yes I was scared, I was afraid of death, I was homesick for my kids, I wanted to smell the air. But I didn’t want to let that show, I was non-compliant from day one. I was treated the worst of any inmate in America. I had no mattress, no blanket, no pillow, no Qur’an or prayer rug. I had no idea which way is Mecca, so I prayed each way each time.”

Speaking of his plea deal, al-Marri insisted that he “pleaded guilty to get home.” As he said, “Everything in that plea bargain that has to do with al-Qaida and terror is 100% false,” adding, “My battery was at 1%, I’m done. From seven years of isolation, I missed my kids, my wife. To kiss my mum before she died outweighed my need to show innocence. In the military jail there’s no light at the end of the tunnel.” As he also said, “My best time was getting [to the end of] my sentence: 18 January 2015. Finite, out.”

On his return to Qatar, as the Guardian proceeded to note, “al-Marri received a hero’s welcome. The prime minister telephoned him and celebrations were held.” As he said, “People were stopping me in the street, taking selfies. What were they celebrating? An inmate who has spent his time in jail and got out? They do not believe I am a terrorist. Terrorist is a relative term; one man’s terrorist is another’s hero. America’s founding father George Washington was a terrorist to the British. To the west, yes, I am a terrorist, but to the Arabs I’m not, I’m a hero. So Osama bin Laden is a hero? When they call me terrorist, or they call me hero, I don’t see that.”

He added, “I was planning a master’s degree and maybe a PhD. I ended up with a PhD in American hospitality. Nobody has been held accountable. There are people who admit they have done this and people who deny it. I do not need apologies, I need accountability. What they said and did to me was torture.”

In a statement, the FBI told the Guardian that they “would not comment on the case,” but insisted that “the FBI does not engage in torture and we maintain that rapport-building techniques are the most effective means of obtaining accurate information in an interrogation.”

It is certainly true that FBI officials generally do insist that rapport-building is the only viable way of conducting interrogations, but in light of al-Marri’s allegations, and lingering doubts about when exactly the FBI walked away from the CIA’s abusive interrogations in 2002, it seem to me that a proper official analysis ought to be established, to ascertain how much, in the early years of the “war on terror,” those guidelines were stretched or even broken.

Note: Please also check out this ITV News interview with Ali al-Marri, and this Middle East Eye article, and if you’re in the UK, you can sign this petition to the Director of Public Prosecution by al-Marri’s son AbdurRahman “seeking the arrest of Ali Soufan so that the United Kingdom Director of Public Prosecutions can investigate the allegations against him further.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

April 27, 2018

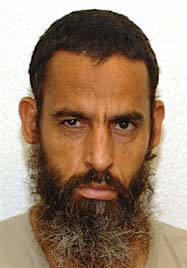

Lawyers for Guantánamo Torture Victim Mohammed Al-Qahtani Urge Court to Enable Mental Health Assessment and Possible Repatriation to Saudi Arabia

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Last Thursday, lawyers for Mohammed al-Qahtani, the only prisoner at Guantánamo whose torture was admitted by a senior official in the George W. Bush administration, urged Judge Rosemary Collyer of the District Court in Washington, D.C. to order the government “to ask for his current condition to be formally examined by a mixed medical commission, a group of neutral doctors intended to evaluate prisoners of war for repatriation,” as Murtaza Hussain reported for the Intercept. He added that the commission “could potentially order the government to release him from custody and return him home to Saudi Arabia, based on their evaluation of his mental and physical state.”

A horrendous torture program, approved by defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld, was developed for al-Qahtani after it was discovered that he was apparently intended to have been the 20th hijacker for the 9/11 attacks. As Hussain stated, court documents from his case state that he was subject to “solitary confinement, sleep deprivation, extreme temperature and noise exposure, stress positions, forced nudity, body cavity searches, sexual assault and humiliation, beatings, strangling, threats of rendition, and water-boarding.” On two occasions he was hospitalized with a dangerously low heart rate. The log of that torture is here, and as Hussain also explained, “The torture that Qahtani experienced at Guantánamo also exacerbated serious pre-existing mental illnesses that he suffered as a youth in Saudi Arabia — conditions so severe that he was committed to a mental health facility there in 2000, at the age of 21.”

The high-level acknowledgement of al-Qahtani’s torture, mentioned above, came just before George W. Bush left office, when Susan Crawford, the convening authority for the military commission trial system at Guantánamo, told Bob Woodward, “We tortured Qahtani. His treatment met the legal definition of torture.” She was explaining why she had refused to refer his case for prosecution.

Shayana Kadidal, Senior Managing Attorney at the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights, said, “Mr. Al Qahtani was already suffering from psychosis when he was brought to Guantánamo and systematically tortured. His psychosis casts serious doubt on all the government speculations that led them to torture him in the first place. He belongs in a psychiatric hospital in Saudi Arabia, not talking to the walls of a cell in Guantánamo.”

Another of his lawyers, Ramzi Kassem, a City University of New York law professor, said, “The government knew from very early in his detention that this man was manifesting serious psychiatric conditions. As early as 2002, a senior FBI official reported observing ‘behavior consistent with extreme psychological trauma’ in Mr. Qahtani, like ‘talking to nonexistent people, reportedly hearing voices, crouching in a corner of the cell covered with a sheet for hours on end.’”

Kassem added, “That was before the worst phase of torture in US custody, which only compounded those conditions. Torture can make a sane person lose their mind, but for someone who had documented mental health issues going back to the age of 8, this treatment was even more harmful.”

Murtaza Hussain also explained that, in 2008, six year after the arrived at Guantánamo, al-Qahtani “attempted to kill himself after being informed that he may face charges that would carry the death penalty.”

Since the charges against al-Qahtani were dropped, he has “continued to be held in a state of legal limbo,” as Murtaza Hussain described it. In 2016, when he faced a Periodic Review Board, an Obama-era parole-type process, which ultimately upheld his ongoing imprisonment, I noted that his lawyers had recently “succeeded in getting an independent psychiatrist, Dr. Emily Keram, to be allowed to visit Guantánamo … to assess al-Qahtani, and what she found — evidence of severe mental health problems predating his capture, and that can only have been exacerbated by his torture in US hands — would seem to suggest that, if he is not to be prosecuted — if, indeed, he is mentally unfit to stand trial — then he should not continue to be held under the laws of war that the US draws on to justify holding prisoners without charge or trial at Guantánamo, and should be returned to his home country.”

Dr. Keram’s evaluation was also included in last week’s submission, which, as Hussain put it, “found that he exhibited symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder and schizophrenia,” adding, “In addition to these conditions, Qahtani is reportedly afraid to sleep due to a fear of ‘ghosts,’ a fear which is consistent with the phenomenon of post-traumatic nightmares.”

The medical evaluation also noted that “Mr. al Qahtani’s symptoms of PTSD and schizophrenia are chronic and are worsening,” adding that “these symptoms will therefore continue beyond one year, will probably continue to worsen, and will be present throughout his lifetime.”

No high-level official has been held accountable for the use of torture by US forces since 9/11, even though, in December 2014, the Senate Intelligence Committee released what Hussain described as “a landmark report about CIA torture that documented the systematic torture of terrorism suspects in agency custody.” He largely blamed Barack Obama’s decision “not to conduct backward-looking prosecutions” for the failure to hold anyone accountable, and with reference to the nomination as CIA director of Gina Haspel, who oversaw a CIA “black site” in 2002, he adds, “This failure to provide legal accountability — even in cases like Qahtani’s, in which U.S. officials acknowledged the torture — has since opened the door for Bush-era officials who authorized torture to return to government service at even higher levels under President Donald Trump.”

Ramzi Kassem told Hussain, “President Obama admitted in 2014 that the US government had ‘tortured some folks,’ but he never named names. So we had a crime but no officially acknowledged victims and, crucially, no identified perpetrators held to account. Mr. Qahtani is therefore the only person in the entire so-called U.S. war on terror who the government has publicly admitted torturing. Repatriating Mr. Qahtani to be committed and treated in a Saudi psychiatric facility would be in everyone’s interest. The United States cannot viably prosecute a man it has admitted torturing, nor can it treat him.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

April 25, 2018

As Two Former Guantánamo Prisoners Disappear in Libya After Repatriation from Asylum in Senegal, There Are Fears for 150 Others Resettled in Third Countries

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Congratulations to the New York Times for not giving up on the story of the two former Guantánamo prisoners who were recently repatriated to Libya despite having been given humanitarian asylum in Senegal two years ago, on the understanding that they would not be sent back to Libya, as it was unsafe for them. The story is particularly significant from a US perspective, because of the role played — or not played — by the State Department, which, under President Obama, facilitated the resettlement of the men, and many others, and, in general, also kept an eye on them after their release.

The story first emerged three weeks ago, when I was told about it by former prisoner Omar Deghayes, and the Intercept published an article. My article is here. A week later, the New York Times picked up on the story, reporting, as Omar Deghayes also confirmed to me, that one of the two men, Salem Ghereby (aka Gherebi) had voluntarily returned to Libya, as he desperately wanted to be united with his wife and children, and because he hoped that his connections in the country would prevent him from coming to any harm. My second article is here.

Unfortunately, on his return, Salem Ghereby was imprisoned at Tripoli’s Mitiga Airport, where human rights abuses have been widely reported, and the British NGO CAGE then reported that the other Libyan, Omar Khalifa Mohammed Abu Bakr (aka Omar Mohammed Khalifh), who didn’t want to be repatriated, had also been sent back to Libya, where he too was imprisoned at the airport. I wrote about that here, and then exclusively published Salem Gherebi’s letter explaining why he had chosen to be repatriated.

That was eight days ago, and since then the trail has gone cold, as the New York Times noted in its most recent article, ‘Deported to Libya, Ex-Gitmo Detainees Vanish. Will Others Meet a Similar Fate?’ written by Charlie Savage, Declan Walsh, and, in Senegal, Dionne Searcey, and published on April 23.

The Times article stated that the Senegalese government’s decision to deport the two men “to their chaotic birth country of Libya” has “raised the prospect that the resettlement system is starting to collapse under President Trump,” explaining how, after “a traumatic journey,” the two men “apparently fell into the hands of a hard-line militia leader who has been accused of prisoner abuse — and then they vanished.”

As the article’s authors recognize, the resettlement program, part of “President Barack Obama’s drive to close the Guantánamo prison,” involved “deals with about three dozen nations to take in lower-risk detainees from dangerous countries.” The article added that officials argued that “[r]esettling them in stable places would increase the chances they would live peacefully … rather than face persecution or drift into Islamist militancy.”

Current and former officials told the Times that the case “sets a worrisome precedent,” the danger being that other countries “may follow Senegal in forcibly moving more of the nearly 150 Obama-era resettled former detainees home to unstable places where they risk being killed — or could end up becoming threats themselves.”

With an inexplicable sense of understatement, the Times stated that the breakdown of the Senegal resettlement also “appears to be at least partly a consequence of the disorganization that has afflicted the State Department since Mr. Trump took office.” It would make more sense, I think, to have stated that the breakdown of the Senegal resettlement is a direct “consequence of the disorganization that has afflicted the State Department since Mr. Trump took office.”

President Obama, as the Times noted, “set up a high-level, centralized office charged with monitoring former detainees indefinitely and dealing with any problems” — the office of the special envoy for Guantánamo Closure. However, under Rex Tillerson, Donald Trump’s first secretary of state, that office was shut down, its function “added to the long list of things individual embassies are supposed to track.”

Daniel Fried, Obama’s first special envoy for Guantánamo Closure, pulled no punches in criticizing the Trump administration, telling the Times, “This is what is going to happen when you close down the Office of Guantánamo Closure for political reasons. Countries conclude that we don’t care anymore, and there is no follow-up.”

A State Department official, speaking anonymously, refuted this assessment, but his protestations, to be frank, sounded feeble.

Analyzing the resettlement program, most of which took place under Obama, although some prisoners were also resettled under George W. Bush, the Times noted that some “have gone well,” explaining, “Former detainees learned their new local languages, found jobs and even married. Others have been rockier. In countries like Uruguay and Kazakhstan, former detainees have struggled to fit in while complaining of inadequate support, distance from relatives and heavy-handed security. In still other countries, like Ghana, the former detainees appear to be doing better, but the government there was heavily criticized by political opponents for agreeing to resettle them.”

As the Times also explained, “Nearly all resettled detainees impose some level of headache on host governments, which generally provide basic assistance while monitoring them. Typically, the receiving countries also agreed not to let the former detainees travel for two or three years, leaving ambiguous what would come next. Against that backdrop, there are reasons to believe Senegal may be the first of many nations that could seek to shed that burden by deporting resettled detainees.”

This is deeply troubling, of course, not just because of the vulnerability of the men in question, but also because of the context — stripped of their rights as human beings in Guantánamo, redefined as “enemy combatants,” who could be held forever without charge or trial, and who, even when released, continue to be regarded by the US as “enemy combatants,” no body of law provides for their treatment. If they become disposable chess pieces, no legislation is in place to stop their abuse, a situation that clearly needs to come to an end now they are facing such a horrendous threat under Donald Trump, and it’s a situation which I fervently hope that lawyers and the United Nations are looking at closely.

The Times specifically mentioned “a Yemeni man resettled in Serbia in 2016,” who “has struggled to learn the local language while complaining that a Guantánamo stigma was wrecking his job and social-life prospects.” That man is Mansoor Adayfi, a talented writer, who, most recently, was interviewed by BBC Radio 4 for a powerful and moving program about the prisoners’ artwork, which the Pentagon recently announced its intention to destroy, after an exhibition in New York revealed the prisoners as human beings with emotions and sensibilities.

As the Times noted, Adayfi “was resettled alongside a former detainee from Tajikistan, who has more readily adapted.” Crucially, however, “both lack legal status, and a Serbian official told one of their lawyers that the government is reviewing whether to deport them this summer, after the two-year travel ban ends,” although a government spokesman “said no decision has been made.”

Beth Jacob, Adayfi’s lawyer, said her client “fears repatriation but she could ‘not even find someone in the US government to discuss our concerns with.’” Matthew O’Hara, who represents the other former prisoner, from Tajikistan, “said his client would likely be persecuted or tortured in Tajikistan, which revoked his citizenship.” As O’Hara put it, “My level of concern went through the roof when I saw what happened in Senegal.”

Regarding the two men resettled in Senegal, the Times noted that it was “a favor to Mr. Obama by its president, Macky Sall,” and that they “were given apartments in Dakar, with a minder living nearby.” Although they had complained about aspects of their treatment, the Times noted that “there were also signs the resettlement was working,” with Khalifa, who “said he was engaged,” being “warmly greeted by his neighbors.”

Senegalese officials, in the Times’ words, “have refused to discuss what prompted them to consider deporting the men,” although the newspaper noted that “[r]elations between African countries and the United States have generally deteriorated under Mr. Trump, especially since reports surfaced in January that he insulted African nations using a crude term.”

Ramzi Kassem, a law professor at the City University of New York who represents Khalifa, told the Times that his client “was first told in January he might not be allowed to stay in Senegal.” Kassem said he emailed the US Embassy “but received no reply.” The men were told in writing that they would be deported on March 26.

While Ghereby did not object because at least in Libya he could be reunited with his family,” Khalifa “was terrified,” telling the Times reporter who visited the two men “that he feared he would be killed.” Neighbors said that the two were taken away by Senegalese security officials just after the interview.

Nothing was heard of them until later that week, when Ghereby “called a human rights organization, from an airport in Tunisia, apparently during a layover to Libya.” Khalifa’s fate “was even more mysterious.” Lee Wolosky, Obama’s second special envoy for Guantánamo Closure, who had negotiated the Libyans’ resettlement, was told by a Senegalese official that Khalifa “would not be forcibly deported,” but that was evidently untrue.

The Times noted that “it now appears that he, too, was sent to Tunisia,” with both men then “flown on to Tripoli and taken into custody by a hostile militia, according to both an intelligence official with Libya’s Government of National Accord, an interim body that is backed by the United Nations but exercises little real authority, and a Libyan airline employee.”

Separately, a spokesman for Libyan Airlines told the Times that “both men took its flight from Tunis to Tripoli, although he did not know what happened to them after,” while Lee Wolosky was eventually told by the Senegalese official that Khalifa was no longer in Senegal.

The intelligence official and the airline employee also explained to the Times that, while in Tunis airport, “one of the men — it was not clear which — began protesting loudly and bloodied his head by banging it against a hard surface,” also explaining that both men had wanted to be flown “to Misrata, a city about 130 miles east of Tripoli,” and “sought to avoid the Tripoli airport because it is controlled by Abdulrauf Kara, a militia commander who runs a counterterrorism detention camp where human-rights groups say mistreatment is rife.” However, “Mr. Kara was determined to take the two men into custody, and sent a group of guards to Tunis to escort them back.”

However, “adding to the murkiness,” in the Times’ words, “Ahmed bin Salam, a spokesman for Mr. Kara’s group, later denied it was holding the men.” In English, he said, “I think they are with the mukhabarat” (the intelligence service), although he “declined to elaborate.”

After the Times article was published online, Stephen Yagman, who had represented Salem Ghereby many years ago, “said his former client and his wife told him last week that Mr. Ghereby was in eastern Libya with his family,” although that could not be independently verified. Yagman said they “did not discuss his journey,” and he “refused to detail how they had communicated.”

Ramzi Kassem, meanwhile, stressed that international law “prohibits forcibly sending people to places where they are likely to be abused,” and “said he held both Senegal and the United States responsible for any harm Mr. Khalifa might suffer.”

However, he also pointed out that the issue at stake “was bigger.” As he put it, “If the other countries that took in Guantánamo prisoners interpret the deafening US silence throughout the Senegal debacle as a signal that the Trump administration no longer cares about past undertakings, then it could soon be open season on those former prisoners. Nothing could be less conducive to the humanitarian ideals the United States professes, nor even to the security objectives it often proclaims.”

The State Department made a woolly statement about who it had “reiterated to the Government of Senegal our expectation that it will uphold its international obligations with respect to both individuals,” which literally means nothing.

Lee Wolosky, in contrast, “said he believed the State Department, under previous administrations, would have persuaded Senegal to take steps to keep the men safe while making its leaders feel like the United States still cared about successfully resettling them.” He added that “[t]he human-rights concerns raised by the fact that the two men apparently ended up in cells in Tripoli … should be cause for alarm.”

As he put it, “The last two administrations tried to responsibly release individuals in a way that took into account both legitimate US security interests and also human rights and the rule of law. This result just utterly frustrates that policy.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

April 23, 2018

The 34 Estates Approved for Destruction By Sadiq Khan Despite Promising No More Demolitions Without Residents’ Ballots

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist.

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist.

Anyone paying any attention to the sordid story of council estate demolitions in London will know how hard it is to take politicians seriously — and especially Labour politicians — when it comes to telling the truth about their actions and their intentions.

Perfectly sound estates are deliberately run down, so that councils can then claim that it’s too expensive to refurbish them, and that the only option is to knock them down and build new ones — with their developer friends who are conveniently waiting in the wings.

In addition, a collection of further lies are also disseminated, which divert attention from the fundamental injustice of the alleged justification for demolitions — false claims that the new housing will be “affordable”, when it isn’t; that part-ownership deals are worthwhile, when they are not; and that building new properties with private developers will reduce council waiting lists, when it won’t.

The biggest lie of this whole “regeneration” racket, therefore, is that structurally sound estates must be knocked down, while, on a day to day basis, the second biggest lie permeates all discussion with the success of Goebbels-style propaganda — the lie that “affordable” housing is affordable. Boris Johnson, in his crushingly dire eight years as London’s Mayor, decided that “affordable” meant 80% of market rents, but that is clearly not affordable, as market rents are so dizzyingly overblown — and completely unfettered by any form of legislation — that people are often paying well over half their incomes in rent, when what was long regarded as fair was a third (similarly, buying a home is now unaffordable for most people, as prices have spiralled out of reach, with a huge deposit needed for a property that costs ten times a buyer’s annual salary, when the fair model of the past used to be that it should cost no more than three and a half times one’s annual income).

Genuinely affordable rents are social rents, paid by council tenants and housing association tenants, which are generally a third of market rents, but it is these rents that central government, councils and, most recently, large housing associations, are trying to get rid of entirely. Behind it all is the stranglehold of Tory austerity, cynically implemented to destroy all public services, but few of those responsible for social housing are fighting back, and many — including many Labour councils — are actually gleefully engaged in social cleansing their boroughs of those they regard as an impediment to gentrification and wealthier incomers.

But here the extent of the delusion ought to become clear. These coveted aspirational professional young people do exist, but they can barely afford to pay the kind of costs associated with a property racket that is only really interested in couples who earn over £70,000 a year, while anyone who earns less — and is regarded as “poor” by bloated public servants who have lost touch with reality — will probably end up being priced out of the future of endless towers of new housing that are largely being bought off-plan by foreign investors, who often leave their investments empty.

Ironically, to keep most workers able to live in London, where, we should note, the mean income is no more than £20,000, compared to the average income, which is around £35,000, the government will end up having to subsidise cynically inflated new build rents, to add to the £26bn housing benefit bill, most of which goes to private landlords, when the only sensible way out of this spiral of greed is to defend social rents, stop knocking estates down, and embark on any number of visionary and large-scale not-for-profit social homebuilding projects to deliver new homes for social rent. City investors will be supportive of such a plan, because guaranteed rents over decades, even at socially rented levels, are actually a good investment, whose rationale has been lost in the forest of greed in which we currently find ourselves that is making life miserable for most renters, or driving them out of the capital altogether.

Over the last few years, the horrors of the housing market have started to become more apparent to more people, with the Heygate development in Southwark as a grim template. There, Southwark Council sold off a Brutalist estate that could easily but mistakenly be portrayed as a sink estate, to Lendlease, rapacious international property developers. The council made no money out of the deal, but Lendlease stands to make £200m from the Heygate’s replacement, Elephant Park, which will contain just 82 units of housing for social rent, when the original estate had over a thousand socially rented flats.

The Heygate provided a template for the effective scrutiny of “regeneration”, but Southwark Council, greedy and contemptuous of its own constituents, failed to heeds its lessons, and has now started demolishing the Aylesbury Estate down the road, one of Europe’s largest estates. There has been noticeable resistance in Lambeth, to proposals to destroy two very well-designed estates, Central Hill and Cressingham Gardens, and the false rationale for destruction becomes more transparent when architects and heritage bodies become involved. A powerful example of this is Robin Hood Gardens in Tower Hamlets, a visionary Brutalist estate, shamefully neglected, whose destruction is, however, well under way despite high-level support for its preservation.

Another key battleground has been Haringey, in north London, where campaigners successfully derailed the first phase of proposals by the council to enter into a giant stock transfer programme with Lendlease, and last June the Grenfell Tower disaster brought into sharp relief, how, in the most horrific manner imaginable, the lives of those who live in social housing are regarded as inferior to those with mortgages.

In autumn, Jeremy Corbyn intervened in the debate about social housing, using his conference speech to say that there must be no more estate demolitions without residents’ ballots. It was a high-profile intervention in the debate, and it set a marker for campaigners, and for the Labour left, but it lacks the teeth to stop destructive Labour councils from continuing with their destruction, and Corbyn has persistently failed to follow up on this grand gesture by engaging in ground-level criticism of people like Peter John and Lib Peck, the leaders of Southwark and Lambeth councils respectively.

Corbyn’s promise was picked up on by Sadiq Khan, London’s Mayor since 2016, who also promised that there would be no estate demolitions without ballots, but was then rumbled by hard-working and tenacious Green London Assembly member Sian Berry, who revealed, a month ago, that, as she put it in the headline of a well-read article on her website, ‘Mayor quietly signs off funding for 34 estates, dodging new ballot rules.’

Berry produced a list of the estates, which are listed below, and stated that the information showed Sadiq Khan “signing off at least over 9,000 home demolitions, leaving around 3,000 homes we can count in schemes that will subject to ballots.” She added, “In total, since the consultation closed nearly a year ago (when the Mayor knew he would have no choice but to introduce ballots) he has signed off funding for 34 estates. And 16 of these schemes have been signed off since 1 December when the Mayor and his team were finalising the new policy and gearing up to announce it.”

As she also stated, “This information paints a sorry picture, and is a harsh slap in the face to many residents on estates under threat who – thanks to his actions – will be denied a ballot at the last moment before his new policy comes in. They include the Fenwick, Cressingham Gardens, Knights Walk and other estates in Lambeth (though not Central Hill), Ham Close in Richmond, Cambridge Road in Kingston and the Aylesbury in Southwark.”

She also stated, “I am appalled by this behaviour, and with the delaying tactics involved in trying not to admit he was rushing through major schemes like this”, and added, “It is a betrayal of the residents on these 34 estates, but it will also disappoint the Mayor’s wider electorate, who are just about to vote in local elections in London. I commissioned YouGov to poll Londoners as a whole on this issue and 64 per cent backed ballots for estate residents, with only 13 per cent against, in results revealed this week.”

A spokesman for the Mayor sought to contradict Sian Berry’s claims, telling the Architects’ Journal, “The mayor made a firm public commitment not to sign off any contracts for new estate regeneration schemes during the consultation [on ballots, which ran from February to April]. No contracts for new estate regeneration schemes have been signed since the consultation on ballots opened.”

The Architects’ Journal added, “According to the mayor, the majority of the 34 decisions were made before last summer, and 16 [other] contracts signed after 1 December were for schemes already allocated funding.”

What actually happened, as careful readers will realise, is that Khan was told — by his advisors, and by councils and developers — that deals that were considered to already be underway — even if they weren’t — had to be approved before any inconvenient new hurdles like ballots could even be considered.

As Sian Berry put it, The mayor needs to think again about how the people on the estates he’s rushed through should be treated. Their right to a ballot can’t be brushed off just because he’s decided to restrict his policy only to questions of funding and pushed these deals through. Many of these estates, including Cressingham Gardens, do not yet have planning permission and the mayor could be asking for ballots to be held on these schemes, and using the results as a consideration in his planning decisions.”

The list of estates, whose destruction was approved after the end of the consultation on the guidance for estate demolition (March 14, 2017) is below, and please follow the links for further information. And what’s particularly interesting, of course, is how only 17 of London’s 32 boroughs are involved, although most of those are Labour-controlled, which is surely something worth reflecting on with London’s local elections taking place next Thursday, May 3.

The 34 estates approved for destruction from March 2017 to January 2018 by Sadiq Khan

SOUTH

Southwark (2)

Aylesbury Estate, SE17 – 3,500 new properties, with Notting Hill Housing Trust, approved October 25, 2017.

Ongoing destruction, particularly resisted by leaseholders facing Compulsory Purchase Orders, who secured a brief but significant success in 2016. Also see ‘The State of London’, and check out the 35 Percent campaign’s detailed account here.

Elmington Estate, SE5 – 632 new properties, with Peabody Trust, approved January 22, 2018.

Ongoing destruction. See ‘The State of London’, and check out the 35 Percent campaign’s detailed account here.

Lambeth (5)

Cressingham Gardens, SW2 – 464 new properties, approved December 1. 2017.

This is a well-designed 1970s low-level estate on the edge of Brockwell Park, with a close-knit community who have mobilised impressive resistance to Lambeth Council’s cynical plans, which clearly involve the attraction to developer son the parkside setting. See ‘The State of London’ for more, and the Save Cressingham Gardens website.

Fenwick Estate, SW9 – 508 new properties, approved December 1. 2017.

Estate near Clapham North tube station, subjected to ‘managed decline’ by council. No tenants’ perspective available online. Do, however, check out Brixton Buzz‘s report from July 2017 about murky goings-on with the proposed development.

Knights Walk, SE11 – 84 new properties, approved September 29, 2017.

Small estate, partly saved in previous resistance involving ASH (Architects for Social Housing).

South Lambeth, SW8 – 363 new properties, approved September 29, 2017.

No tenants’ perspective available online. Lambeth Council’s page is here.

Westbury Estate, SW8 – 334 new properties, approved September 29, 2017.

No tenants’ perspective available online. Lambeth Council’s page is here.

Lewisham (2)

Frankham Street, SE8 (aka Reginald Road) – 209 new properties, with Peabody Trust, approved January 22, 2018.

Long-standing battle to save a block of 16 council flats (Reginald House) and Old Tidemill Garden, a community garden, from destruction as part of the redevelopment of the old Tidemill School. Alternative plans could easily preserve the garden and flats, but the council and Peabody aren’t interested. For the resistance, see here and here.

Heathside & Lethbridge, SE10 – 459 new properties, with Peabody Trust, approved January 22, 2018.

Ongoing destruction of two estates, only one of which, the Brutalist Lethbridge Estate, is still standing. No tenants’ perspective online. See ‘The State of London.’

Greenwich (1)

Connaught, Morris Walk and Maryon, SE18 – 1,500 new properties, approved January 15, 2018.

Planned destruction of three estates. Connaught has already been demolished, and is being replaced by a new development. Morris Walk and Maryon are subjected to serious ‘managed decline.’ No tenants’ perspective online. For Maryon, see ‘The State of London.’

Bexley (1)

Arthur Street, DA8 – 310 new properties, with Orbit Group Limited, approved December 22, 2017.

Proposed development of an estate including three tower blocks in Erith. See Orbit Homes’ plans here, and this Bexley Times article.

Wandsworth (1)

St. John’s Hill, SW11 – 599 properties, with Peabody Trust, approved January 22, 2018.

The continuation of the destruction of a 1930s estates and its replacement with new properties because, as Peabody alleges,”the accommodation does not now fit the needs of residents.” They also note, “Phase 1 of the redevelopment (153 homes) was completed in April 2016 and includes 80 homes for social rent, 6 shared ownership and 67 private sale.” See Peabody’s page here.

Merton (1)

High Path, SW19, Eastfields, Ravensbury, CR4 – 2,800 properties, with Clarion Housing Group, approved December 21, 2017.

See development information about these estates in South Wimbledon (High Path) and Mitcham (Eastfields, Ravensbury) on the website of Clarion (formed from the merger of Affinity Sutton and Circle Housing in 2016) here. A local news article last May stated, “Clarion estimate there are currently 608 homes in High Path, 465 in Eastfields and 192 in Ravensbury. Including the replacement houses, about 1660 homes will be built in High Path, 800 in Eastfields and up to 180 in Ravensbury. This means that after the replacement homes have been built for the existing tenants, an extra 1,800 homes will be available to rent and buy.” No mention was made of what these new rental costs might be.

Richmond upon Thames (1)

Ham Close, TW10 – 425 properties, with Richmond Housing Partnership Limited, approved November 17, 2017.

See the Ham Close Uplift website for further information.

Kingston (1)

Cambridge Road, KT1 – 2003 properties, approved October 10, 2017.

See the council’s plans here for the redevelopment of the site, which includes three tower blocks. For the residents’ association, see here, and also check out this local news article from 2016.

EAST/NORTH

Tower Hamlets (4)

Aberfeldy Estate (phases 4, 5 & 6), E14 – 206 properties, with Poplar HARCA Ltd, approved October 18, 2017.

Ongoing destruction of an estate in Poplar — a 12-year project involving the creation of over 1,000 new properties. For more information, see the website of architects Levitt Bernstein, and also see Poplar HARCA’s site. Rather pretentiously, I think, the architects claim, “The site’s illustrious past is made visible through art installations including case concrete tea crates and brass cotton reels in the landscape and paisley patterns etched in the paving. Crisp detailing and a limited material palette give the buildings a modern warehouse aesthetic.”

Blackwall Reach, E14 – 1,575 properties, approved March 23, 2017.

This is a much-criticised project that involves the destruction of Robin Hood Gardens, the acclaimed Brutalist masterpiece, which was, indeed, an extraordinary creation, although it was severely neglected by Tower Hamlets Council as part of very deliberate “managed decline.” For more, see ‘The State of London’ here and here.

Chrisp Street Market, E14 – 643 properties, with Poplar HARCA Ltd, approved October 18, 2017.

This contentious project involves the destruction of the first purpose-built pedestrian shopping area in the UK, created for the Festival of Britain in 1951, and associated housing, although it has met with strong local resistance, and was put on hold by the council in February 2018. See a City Metric article here.

Exmouth Estate, E1 – 80 properties, with Swan Housing Association, approved March 23, 2017.

The estate is just off the Commercial Road, but I can’t find any information available online. However, Swan Housing Association came in for serious criticism after the stock transfer from the council in 2006, which Socialist Unity reported in 2009.

Barnet (1)

Grahame Park (phase B, plots 10, 11 & 12), NW9 – 1,083 homes, with Genesis Housing Association Ltd, approved November 24, 2017.

For the council’s plans for this estate in Colindale, see here. They claim that, with Genesis, as “the developer and resident social landlord”, who have now merged with Notting Hill, they will build approximately 3,000 homes by 2032, including around 1,800 new private homes, around 900 new “affordable” homes. In addition, “Approximately 25 per cent (463) of the original homes will be retained and integrated into the new development.” Also see the Notting Hill Genesis page here.

Brent (1)

South Kilburn Estate (various phases), NW6 – 2,400 homes, with Notting Hill Housing Trust, Network Homes Ltd, L&Q and Catalyst Housing Group, approved October 23, 2017.

Ongoing destruction. For the Observer, Rowan Moore was full of praise for the new development in 2016, stating, “Thanks to the enlightened thinking of Brent council and Alison Brooks Architects, a notorious London estate that featured in Zadie Smith’s White Teeth is now the site of some of the best housing in the neighbourhood.” See Brent Council’s page here, and also see a review on the Municipal website here.

Enfield (1)

Alma Estate, EN3 – 993 homes, with Newlon Housing Association and Countryside, approved November 15, 2017.

Ongoing destruction of four big tower blocks in Ponders End. See ‘The State of London.’

Havering (5)

Napier House and New Plymouth House, RM13 – 200 homes, approved January 31, 2018.

See Havering Council’s page for the planned redevelopment of these two tower blocks in Rainham here. And see this Romford Recorder article from 2016 about the first consultations with tenants. Also see Edinburgh University’s ‘Tower Block’ site, which shows both towers, and describes them, collectively, as Dovers Farm Estate.

Waterloo Estate, RM7 – 994 homes, approved January 31, 2018.

See Havering Council’s page for the planned redevelopment of this estate in Romford here. And see this Romford Recorder article from 2016 about the shock felt by residents when they first received the news.” As the article noted, “Ruth Crabb, who has lived on the Waterloo Estate for 18 years, said she was concerned residents had no idea about the proposed plans to potentially demolish the estate and build an additional 220 homes. ‘The fact that they haven’t even bothered to write to us as tenants and explain what they have planned … we are quite shocked,’ she said.”

Orchard Estate (former Mardyke), RM13 – 55 homes, with Clarion Housing Group, approved December 21, 2017.

The approval for further development at the Orchard Village Estate in Rainham came despite huge problems with earlier development on the site. From February 2017, in the Guardian, see Leaking sewage and rotten floorboards: life on a ‘flagship’ housing estate, Housing association agrees to buy back homes on ‘substandard’ development and Chairman of housing association behind ‘substandard’ development resigns.

Queen Street Sheltered Housing Scheme, RM7 – 6 homes, approved July 17, 2017.

See Havering Council’s page for the redevelopment of this small block of sheltered housing in Romford here.

Solar, Serena, Sunrise Sheltered Housing Scheme, RM12 – 54 homes, approved July 17, 2017.

See Havering Council’s page for the redevelopment of this sheltered housing in Hornchurch here.

Barking & Dagenham (1)

Gascoigne West (Barking Town Centre), IG11 – 850 homes, approved July 27, 2017.

For the outline planning application in September 2017, see this article on the ‘BOLD’ website, dealing with development and regeneration in Barking and Dagenham. The redevelopment of Gascoigne East was approved under Boris Johnson, and began in 2015.

WEST

Kensington & Chelsea (2)

William Sutton Estate, SW3 – 270 homes, with Clarion Housing Group, approved December 21, 2017.

The Sutton Estate in Chelsea was built in 1913 by the philanthropist William Sutton expressly to provide “houses for use and occupation by the poor”, as the Guardian explained in 2016, when their then-owners, Affinity Sutton, a housing association, which has since merged with Circle Housing to become the Clarion Housing Group, planned to bring a century of social housing to an end on the site, proposing to “replace more than 200 affordable homes with luxury apartments for private sale.” That plan was turned down by Kensington & Chelsea Council, but Clarion has appealed the ruling, and a hearing will be held on May 9, 2018. I can only wonder if Sadiq Khan’s premature approval of the redevelopment will affect the decision. For more information, see the Save the Sutton Estate website, and also see Clarion’s position.

Wornington Green, W10 – 1,000 homes, with Catalyst Housing Ltd, approved January 8, 2018.

The estate, as Catalyst explain, “originally comprised 538 flats and houses (accommodating approximately 1,700 residents) which were constructed between 1964 and 1985 in predominantly large deck-blocks, typical of public housing of the period.” Work has already begun on the replacement, with Phase One “includ[ing] the building of 324 new homes, a mix of 174 for affordable rent and 150 homes for private sale.” And here, as usual, that word “affordable” is misleading. Phase Two of the project began in Autumn 2017, but it is difficult to take Catalyst’s claims at face value — that there will be “no loss of social housing”, because “all current tenants will be offered new homes in the development.”

Ealing (4)

Friary Park, W3 – 476 homes, with Catalyst Housing Ltd, approved January 8, 2018.

The estate is in Acton, and as Catalyst explain, “Friary Park was originally built for private sale by Laing Construction. It was purchased by Catalyst (then Ealing Family Housing Association) in 1987. We’ve been considering a range of options to improve the neighbourhood and have decided that the best route is to redevelop the estate – demolishing existing homes and replacing them with new, high-quality, energy-efficient ones.” In 2015, when plans were first proposed, locals expressed concern that the new development would feature a 29-storey tower that would be “West London’s tallest building”, and “would loom over much of Acton including some of the area’s most expensive streets.”

Havelock Estate, UB2 – 922 homes, with Catalyst Housing Ltd, approved January 8, 2018.

The estate is in Southall, and on their website town planning consultants Barton Willmore enthused about how outline permission had been granted “for the demolition of 695 homes to replace with 922 new homes, whilst retaining 154 of the existing homes”, adding, “This includes 367 affordable social rent homes, 121 intermediate tenure homes and 434 new market sales homes. Combined, this will result in 1,076 homes across the site.” As usual, it take serious scrutiny to assess quite how severe is the loss of social rents. For Catalyst’s page, see here.

Green Man Lane, W13 – 770 homes, with A2Dominion Homes and Rydon/FABRICA, approved November 7, 2017.

Conran & Partners are the “masterplanners and project architects” for this development in Ealing, in which an entire 1970s estate of 464 homes will be demolished to make way for 764 new properties, For an 88-year old resident’s memories of the old estate from 2010, see this local news article.

South Acton, W5 – 2,600 homes, with L&Q, approved November 7, 2017.

As Ealing Council explains, “South Acton is the council’s largest estate”, built over 30 years from 1949 with several tower blocks and slab blocks, which “eventually became one of the largest municipal housing estates in West London, with almost 2,100 homes.” In 2008, the council decided to “comprehensively regenerate the area, as this is considered to be the best way to acheive [sic] the transformative effect desired by residents and the council”, and Acton Gardens (a collaboration between L&Q and Countryside) became the council’s chosen development partner in 2010.

Sian Berry’s document also contained a list of eleven estates whose destruction was approved by Boris Johnson. They are listed below.

Eleven additional estates whose destruction was approved by Boris Johnson

Barking & Dagenham: Gascoigne Estate (Blocks A1, A2, B1, C1, D1), IG11 – 175 homes, with East Thames (now L&Q), approved March 23, 2015.

Camden: Abbey Area (phases 1, 2 & 3), NW6 – 241 homes, approved March 11, 2016. See Camden Council’s page.

Camden: Agar Grove, NW1 – 513 homes, approved March 11, 2016. See Camden Council’s page.

Ealing: Rectory Park, UB5 – 425 homes, with Network Homes Ltd, approved February 2, 2015. See Ealing Council’s page for this development in Northolt.

Ealing: Greenford – Allen Court, UB6 – 89 homes, with Notting Hill Housing Trust, approved December 8, 2014. See this page for information about this development in Greenford.

Enfield: Ladderswood Way Estate, N11 – 517 homes, with One Housing Group Ltd, approved October 17, 2014. See the website here.

Hammersmith & Fulham: Lisgar Terrace (Phase 4), W14 – 36 homes, with Southern Housing Group, approved January 12, 2015. See Southern’s website here.

Lambeth: Loughborough Park, SW9 – 487 homes, with the Guinness partnership, approved October 31, 2014. See ‘The State of London.’

Tower Hamlets: New Union Wharf (Phases 2 and 3), E14 – 75 homes, with East Thames (now L&Q), approved March 25, 2013. See the website here.

Tower Hamlets: Ocean Estate (Site H), E1 – 121 homes, with East Thames (now L&Q), approved March 25, 2013. See Levitt Bernstein’s page here for this development in Stepney.

Waltham Forest: Marlowe Road Estate, E17 – 436 homes, approved December 14, 2015. See the council’s website here.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

April 21, 2018