Andy Worthington's Blog, page 35

June 10, 2018

Remembering Guantánamo’s Dead, 12 Years After the Three Notorious Alleged Suicides of June 2006

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Today, as we approach a terrible milestone in Guantánamo’s history — the 6,000th day of the prison’s existence, this coming Friday, June 15 — we also have reason to reflect on those who were neither released from the prison, nor are still held — the nine men who have died there since the prison opened, 5,995 days ago today.

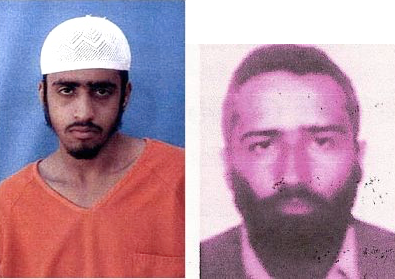

On June 10, 2006 — exactly 12 years ago — the world was rocked by news of the first three of these deaths at Guantánamo: of Yasser al-Zahrani, a Saudi who was just 17 when he was seized in Afghanistan in December 2001, of Mani al-Utaybi, another Saudi, and of Ali al-Salami, a Yemeni.

The three men were long-term hunger strikers, and as such had been a thorn in the side of the authorities, encouraging others to join them in refusing food. Was this enough of them to be killed? Perhaps so. The official story is that they killed themselves in a suicide pact, their deaths, as Guantánamo’s commander, Adm. Harry Harris Jr., ill-advisedly claimed at the time, “an act of asymmetrical warfare against us,” and “not an act of desperation.”

I commemorate the men’s deaths every year, as they remain significant, and they otherwise tend to have become forgotten, remembered only by the likes of writer and retired psychologist Jeffrey Kaye, and former US Staff Sergeant Joe Hickman.

Hickman is the leading witness in a case against the US military that has never been allowed to proceed — on which alleges that the three men did not kill themselves sin a suicide pact, but were killed. Hickman’s testimony, as the head of the guard watch in the prison’s towers, is that the story of the men’s deaths emerged only after vehicles that he had seen coming to and from a remote site — a secret facility he and other guards dubbed “Camp No,” had brought back what he presumed were their bodies, already dead, from that location, where they had either been deliberately killed, or had been accidentally killed as part of a torture session that went too far.

Hickman’s recollections, and his assessment of what happened on the night of June 9-10, 2006, was the main driver of lawyer and journalist Scott Horton’s article “The Guantánamo Suicides,” published in Harper’s Magazine in January 2010, which caused a stir — and won a journalism award — but which was never adequately followed up on, and which also received undue criticism from other media outlets.

And yet the gist of Hickman’s recollections remains a powerful rebuke to the official story, and has become part of a narrative amongst alternative US media that make a point of investigating the actions of their government. Just days ago, for example, the AllGov website recalled the alleged “suicides” in a story about Harris (recently nominated as ambassador to South Korea by Donald Trump), noting how, although he had “quickly declared the deaths to be suicides … an investigation by Harper’s magazine cast considerable doubt on that verdict, pointing out the near simultaneous times of death while held separately; the improbability of the prisoners’ ability to kill themselves in the manner described (stuff rags down their throats, and then climb up on a counter and hang themselves); and bruises and other injuries suffered by the prisoners. The article suggested that the three were killed during a torture/interrogation session held in a secret part of the base.”

In revisiting the deaths this year, I also came across a well-written article in Newsweek from January 2015, “To Live and Die in Gitmo,” by Alexander Nazaryan, published to coincide with the publication of Hickman’s book, Murder At Camp Delta.

Nazaryan provided the following helpful profiles of the three men who died:

Mana Shaman Allabardi al-Tabi (588) was a Saudi national who joined a religious charity called Tablighi Jamaat, which was believed to have links to Al-Qaeda. On January 17, 2002, “detainee was captured with four other individuals who were dressed in burkas trying to avoid capture” as he was leaving the Pakistani city of Bannu, on the border with Afghanistan, his Department of Defense file reads. On March 8, 2002, he was handed over to American forces and shipped to Guantánamo Bay, where he was described as “belligerent, argumentative, harassing, and very aggressive”—and useless when it came to intelligence about Al-Qaeda. He was cleared to be “transferred to the control of another country for continued detention.”

Yasser Talal al-Zahrani (093), also Saudi, was the son of a prominent government official. Jihad tugged at him in the early summer of 2001, when he had finished the 11th grade. “After sitting at home for approximately two months and hearing that sheiks from neighboring towns were saying jihad in Afghanistan was a religious duty, [al-Zahrani] decided to travel to Afghanistan,” his Pentagon file says. He went to Pakistan, then Afghanistan. Instead of starting his senior year of high school, he learned at a Taliban training center how to use a Kalashnikov assault rifle and a Makarov pistol. He served as “a fighter on the front lines of [the Battle of Kunduz]” during the American invasion of Afghanistan, where he was captured by the Northern Alliance. Al-Zahrani was turned over to American forces on December 29, 2001. His intelligence value was also minimal.

Ali Abdullah Ahmed (693) was a Yemeni who, according to his Department of Defense record, was “a street vendor who sold clothing…and was prompted to travel to Pakistan to receive [a religious] education upon hearing God’s calling.” He was captured at a safe house in Faisalabad that was alleged to be under the control of Abu Zubaydah, then believed to be one of Osama bin Laden’s top officers. Branded by the Pentagon as “a mid-to-high-level Al-Qaeda” operative, Ahmed arrived in Cuba on June 19, 2002. Later, government investigators realized there was “no credible information” tying him to terrorism. But this wasn’t the Palookaville slammer: If you tell the world, as the Pentagon did, that your island prison is home to “the worst of the worst,” you won’t want to advertise your errors and hyperboles. So they kept Ahmed.

Nazaryan also noted, aptly, “Much of what happens at Guantánamo, why it happens and who orders it to happen lurks in the shadowy realm of ‘unknown unknowns,’ in the famous formulation of former defense secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld,” and, in the course of describing Hickman’s journey from Staff Sergeant to key witness in a thwarted prosecution, also revisited the investigation into the deaths by the Seton Hall Law School, published just before Scott Horton’s Harper’s article, which forensically took apart the official NCIS investigation, noting, in particular:

There is no explanation of how each of the detainees, much less all three, could have done the following: braided a noose by tearing up his sheets and/or clothing, made a mannequin of himself so it would appear to the guards he was asleep in his cell, hung sheets to block vision into the cell — a violation of Standard Operating Procedures, tied his feet together, tied his hands together, hung the noose from the metal mesh of the cell wall and/or ceiling, climbed up on to the sink, put the noose around his neck and released his weight to result in death by strangulation.

The season of death

The deaths of the three men on the night of June 9-10, 2016 are not the only suspicious deaths at this time of year. I reported at the time about the alleged suicides of Abdul Rahman al-Amri, a Saudi, on my 30, 2017, and Muhammad Salih (aka al-Hanashi), a Yemeni, on June 1, 2009, and I have since written about their cases, but for many years now — probably more years than he cares to remember — Jeffrey Kaye has investigated their cases, reaching the conclusion that the story of their suicides is “unlikely,” as he explains in his book, Cover-up at Guantánamo: The NCIS Investigation into the “Suicides” of Mohammed Al Hanashi and Abdul Rahman Al Amri.

These are not the only deaths at Guantánamo, and not the only suspicious deaths either. In September 2012, Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif, who had serious mental health problems, died, reportedly by committing suicide — although, again, serious doubts have been expressed about the official narrative, and, as I explained at the time, in an article entitled, Obama, the Courts and Congress Are All Responsible for the Latest Death at Guantánamo, his death was not just a problem involving the military at Guantánamo; it also involved failures by all three branches of the US government in relation to his case. As I stated at the time:

I felt sick when I heard the news: that the man who died at Guantánamo … was Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif, a Yemeni. I had been aware of his case for six years, and had followed it closely. He had been cleared for release under President Bush (in December 2006) and under President Obama (as a result of the Guantánamo Review Task Force’s deliberations in 2009). He had also had his habeas corpus petition granted in a US court, but, disgracefully, he had not been freed.

Instead of being released, Adnan Latif was failed by all three branches of the US government. President Obama was content to allow him to rot in Guantánamo, having announced a moratorium on releasing any Yemenis from Guantánamo after Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, a Nigerian recruited in Yemen, tried and failed to blow up a plane in December 2009. That ban was still in place when Latif died, and had been put in place largely because of pressure from Congress.

Also to blame are the D.C. Circuit Court and the Supreme Court. Latif had his habeas corpus petition granted in July 2010, but then the D.C. Circuit Court moved the goalposts, ordering the lower court judges to give the government’s alleged evidence — however obviously inadequate — the presumption of accuracy. Latif’s case came before the D.C. Circuit Court in October 2011, when two of the three judges — Judges Janice Rogers Brown and Karen LeCraft Henderson — reversed his successful habeas petition, and only Judge David Tatel dissented, noting that there was no reason for his colleagues to assume that the government’s intelligence report about Latif, made at the time of his capture, was accurate, as it was “produced in the fog of war, by a clandestine method that we know almost nothing about.” In addition, Judge Tatel noted that it was “hard to see what is left of the Supreme Court’s command,” in 2008’s Boumediene v. Bush ruling, granting the prisoners constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights, that the habeas review process be “meaningful.”

Despite this, when the Supreme Court had the opportunity to take back control of the Guantánamo prisoners’ habeas petitions in June this year, through a number of appeals, including one by Latif, they refused.

Before Latif, Abdul Razzaq Hekmati, a profound case of mistaken identity — an Afghan who had actually helped significant individuals opposed to the Taliban and al-Qaeda escape from an Afghan prison — died of cancer in December 2007, and I wrote about the US government’s callous refusal to investigate his story (as they also did in numerous other cases) in a front-page story for the New York Times in February 2008, which I wrote with Carlotta Gall, entitled, Time Runs Out for an Afghan Held by the U.S.

in February 2011 an Afghan, Awal Gul, died after taking exercise, and in May 2011 another Afghan, known as Inayatullah (although that was not his real name, which was Hajji Nassim, and he too appeared to be a case of mistaken identity) also died, reportedly by committing suicide. Like Latif, he too had profound mental health issues, which were largely — and, in the end, fatally — ignored by authorities.

In closing, while reminding readers that Jeffrey Kaye has uncovered evidence that there were other deaths shortly after prisoners’ arrival at Guantánamo that have never been properly investigated, and marveling, frankly, that no one has died at the prison since Latif in September 2012, I’d like to point out that prisoners will, at any time, begin dying of age-related illnesses at Guantánamo unless we can find a way to get Donald Trump to shut it down, and, with that in my mind, I do urge you to get involved in our campaign to mark the 6,000th day of Guantánamo’s existence on June 15.

Note: For further information, see: Second anniversary of triple suicide at Guantánamo (in 2008), Murders at Guantánamo: The Cover-Up Continues (in 2010), The Season of Death at Guantánamo (in 2013), New Evidence Casts Doubt on US Claims that Three Guantánamo Deaths in 2006 Were Suicides (in 2014), Remembering the Season of Death at Guantánamo (in 2015) Remembering Guantánamo’s Dead (in 2016), and, last year, Another Sad, Forgotten Anniversary for Guantánamo’s Dead. On the third anniversary of the men’s deaths, in 2009, I produced a report about hunger strikes and the strikers’ devastating weight loss in Guantánamo’s Hidden History: Shocking Statistics of Starvation, and in 2011 I cross-posted a detailed defense of Scott Horton by the psychologist Jeff Kaye.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 7, 2018

June 15 Marks 6,000 Days of Guantánamo: Join Us in Telling Donald Trump, “Not One Day More!”

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Next Friday, June 15, 2018, is a bleak day for anyone who cares about justice and the rule of law, because the prison at Guantánamo Bay, where men are, for the most part, held indefinitely without charge or trial, will have been open for 6,000 days; or, to put it another way, 16 years, five months and four days. We hope you will join us in making some noise to mark this sad milestone in America’s modern history.

All year we’ve been running the Gitmo Clock, which counts, in real time, how long Guantánamo has been open, and in connection with that, we’ve made posters available every 25 days showing how long the prison has been open, and inviting suporters of Guantánamo’s closure to take photos with them, and to send them to us. The poster for 6,000 days is here. Please print it off, take a photo with it, ask your family and friends to do the same, and send the photos to us. We will add them to the photos we’ve been publishing all year, which can be found here.

How long is 6,000 days?

To give you some idea of how long 6,000 days is, try to remember what you were doing on January 11, 2002, when the prison opened. Perhaps you weren’t yet born, or perhaps, like me, you have sons or daughters who were just toddlers when those first photos of orange-clad, sensorily-deprived prisoners kneeling in the Caribbean sun as US soldiers barked orders at them were first released. My son is now 18 years old — nearly 18 and a half, in fact — but he was just two when Guantánamo opened.

For anyone 16 and under, Guantánamo has been open their whole lives, and, in addition, for Americans and other NATO members like the UK, our countries have also, unacceptably, been at war for their entire lives, mired in an unwinnable situation in Afghanistan, in which, as the author Anand Gopal explained to me several years ago, the US actually snatched defeat from the jaws of victory back in 2002, when the Taliban fell and al-Qaeda were decimated, but the US stayed on, out of its depth and played by whichever dubious lawlords succeeded in persuading them that they were their best friends.

I have been intimately involved in the Guantánamo story, researching and writing about it on an almost daily basis, for over 12 years now, beginning in March 2006. At the time, the prison had been open for less than 2,000 days. That milestone was reached on June 3, 2006, just days before one of the most shocking episodes in Guantánamo’s long and sordid history — the deaths of three prisoners, which the authorities described as a triple suicide, and “an act of asymmetrical warfare,” but which other parties, including former US military personnel who served on the base at the time, regard as probable homicides.

President Obama, who took office in January 2009 promising to close Guantánamo within a year, had already been in office for over a year when, still open, the prison marked its 3,000th day of operations, on March 29, 2010. 4,000 days also took place on Obama’s watch, on December 23, 2012, just three days after my son’s 13th birthday, and 5,000 days, on August 20, 2014.

Play this game yourself, if you like, and see what you can remember when — and then imagine being held in Guantánamo for all this time, without even being able to see any of your family members, even if they could get out to Guantánamo, because no Guantánamo prisoner has ever been allowed a family visit, unlike those convicted of the most horrendous crimes on the US mainland.

Remember too that the total length of World War I and World War II was just 3,757 days (1,564 days plus 2,193 days), and yet the “war on terror” declared by the administration of George W. Bush, of which Guantánamo is a key component, has now been ongoing for over 6,100 days, with no sign that those with power and influence in the US have any intention of acknowledging that a war cannot go on forever, and that it must be bounded in some way by time and place.

After 9/11, the Bush administration effectively declared the entire world to be a battleground in an endless war, an outrageous proposal, and yet one which Obama endorsed with his extra-judicial drone assassinations in countries with which the US was not at war, and one which, of course, Donald Trump has also been free to interpret as he wishes.

Why Guantánamo must be closed

Conceived in the heat of vengeance following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the prison at Guantánamo Bay was, from the beginning, a dangerous aberration, turning its back on centuries of laws and treaties regarding the treatment of prisoners.

In countries that, like the US, claim to respect the rule of law, there are only two ways to deprive someone of their liberty — either as a criminal suspect, to be changed and tried without undue delay, or as a prisoner of war, taken off a battlefield, who can be held unmolested until the end of hostilities under the terms of the Geneva Conventions.

At Guantánamo, however, the US invented a third category of prisoner — “enemy combatants,” who had no rights whatsoever, and were taken to Guantánamo, a US naval base on Cuba, so that they would be beyond the reach of the US courts, and so that the US authorities could do what they wanted with them.

In February 2002, George W. Bush issued a presidential memo specifically depriving them of the protections of the Geneva Conventions, and, sadly, for the next two years and four months, there was nothing to protect them from the torture and abuse that the US authorities implemented, and which they also practiced in Afghanistan, and in Iraq, where, eventually, the Abu Ghraib scandal surfaced to provide an insight into what the “war on terror” really meant.

Over the years, lawyers fought back against the black hole that Guantánamo was at its founding, securing access to the prisoners after taking a case all the way to the Supreme Court to establish, in Rasul v Bush in June 2004, that, because the prisoners had no way of challenging the basis of their detention if they claimed to have been wrongly detained, they had habeas corpus rights; the right to challenge the basis of their imprisonment before a judge. The arrival of attorneys in the fall of 2004 finally punctured the veil of secrecy that had, to that date, enabled torture and abuse to take place with relative impunity.

However, despite the promise of the Rasul ruling, the struggle to secure meaningful rights for the prisoners was eventually derailed. First, Congress passed legislation intended to strip the prisoners of their newly granted habeas rights. It then took until June 2008, in Boumediene v. Bush, for the Supreme Court to issue a second habeas ruling, concluding that Congress had erred, and granting the prisoners constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights.

That ruling led to a brief period in which the law actually applied at Guantánamo, and 38 prisoners had their habeas corpus petitions approved by judges, who impartially assessed the evidence, and concluded that the government had failed to make a case that they were involved with al-Qaeda or the Taliban. Along the away, the judges often exposed what objective research into the prison had firmly established — that the basis for rounding up prisoners and sending them to Guantánamo was horribly flawed, with no one actually caught “on the battlefield,” as the US alleged, and with the majority seized by the US’s Afghan and Pakistani allies, at a time when the US was offering substantial bounty payments (around $5,000 a head, a huge amount of money in Afghanistan and Pakistan) for anyone who could be packaged up as al-Qaeda or Taliban suspects.

Screening by the US in Afghanistan, where all the prisoners were processed, was almost non-existent, so when the prisoners arrived at Guantánamo, very little was known about almost all of them, and when they then failed to respond to questioning about al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden, because, in many cases, they had no information to provide, they were regarded as being terrorists trained to resist interrogation, and were then subjected to torture or other abuse designed to “break” them. This process, in turn, led to countless false statements being made, which fill the formerly classified military files that were released by WikiLeaks in 2011, for which I was a media partner.

Although there was a brief flowering of justice with regard to Guantánamo for a few years after the Boumediene ruling, politically motivated judges in the appeals court in Washington, D.C. responded by changing the rules and eventually gutting habeas corpus of all meaning for the Guantánamo prisoners by insisting that any information presented by the government had to be presumptively regarded as accurate.

Since 2010, no prisoner has been freed from Guantánamo as a result of a habeas corpus petition, and, with the law shut down yet again, prisoners have only been released at the whim of the president, or of Congress, and, in a few cases, through plea deals in the otherwise broken military commission trial system set up under the Bush administration to try prisoners at Guantánamo.

President Obama faced unprincipled opposition from Republican lawmakers over Guantánamo, but he responded by generally sitting on his hands, establishing himself as unwilling to spend political capital overcoming their opposition. He did, however, set up two review processes to assess the prisoners’ cases, which, although they had no legal power, ended up in 196 prisoners being released on his watch, compared to 532 under George W. Bush. Crucially, however, he left Guantánamo open for his successor to deal with as he saw fit.

41 men were still held at Guantánamo when Donald Trump took office, and Trump has shown no interest in releasing anyone, forcefully demonstrating how, fundamentally, Guantánamo remains a lawless place, where prisoners can only be freed if the president wants them freed. Although five of the 41 men he inherited from Obama were approved for release by the previous president’s review processes, and although only nine men are facing or have faced trials, Trump has, to date, released only one man, a Saudi sent back to ongoing imprisonment in Saudi Arabia, whose transfer out of the prison was only possible because of a plea deal he agreed in 2014.

With the doors of Guantánamo sealed shut by Donald Trump and a Republican majority in Congress, it would be enormously helpful if everyone concerned with justice and the rule of law joined us in saying to Donald Trump, on the 6,000th day of Guantánamo’s existence, “Not One Day More!”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 4, 2018

European Court of Human Rights Condemns Romania and Lithuania for CIA “Black Sites” Where Abu Zubaydah and Abd Al-Rahim Al-Nashiri Were Tortured

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

In two devastating rulings on May 31, the European Court of Human Rights found that the actions of the Romanian and Lithuanian governments, when they hosted CIA “black sites” as part of the Bush administration’s post-9/11 torture program, and held, respectively, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri and Abu Zubaydah, who have both been held at Guantánamo since September 2006, breached key articles of the European Convention on Human Rights; specifically, Article 3, prohibiting the use of torture, Article 5 on the right to liberty and security, Article 8 on respect for private life, and Article 13 on the right to an effective legal remedy.

The full rulings can be found here: Abu Zubaydah v. Lithuania and Al-Nashiri v. Romania.

In the case of al-Nashiri, who faces a capital trial in Guantánamo’s military commission trial system, as the alleged mastermind of the bombing of USS Cole in 2000, in which 17 US sailors died, the Court also found that the Romanian government had denied him the right to a fair trial under Article 6 of the ECHR, and had “exposed him to a ‘flagrant denial of justice’ on his transfer to the US,” as Deutsche Welle described it, adding that the judges insisted that the Romanian government should “seek assurances from the US that al-Nashiri would not be sentenced to the death penalty, which in Europe is outlawed.” Abu Zubaydah, it should be noted, has never been charged with anything, even though the torture program was initially created for him after his capture in a house raid in Pakistan in March 2002. At the time, the US authorities regarded him as a senior figure in Al-Qaeda, although they subsequently abandoned that position.

The Court also ordered Lithuania and Romania to pay €100,000 ($117,000) to each man, echoing the amounts the Court ordered Poland to pay to them when similar rulings were issued in 2014, as I wrote about here and here.

Responding the news, Human Rights Watch also pointed out how the Court had also “highlighted the serious deficiencies in the national investigations” by the Romanian and Lithuanian governments, and “urged both countries to conclude their investigations into their involvement in the rendition program without delay and to identify and punish relevant officials.”

Nadim Houry, the terrorism/counterterrorism director at Human Rights Watch, said, “The European Court’s rulings highlight that European officials have never faced the music for facilitating the CIA’s illegal torture and rendition program. The lack of accountability, mirrored in the US with the approval of an official involved in the rendition program as the new CIA director, leaves the door open for a return to these illegal practices.”

As Human Rights Watch also noted:

The European Court gave short shrift to the investigations and related diplomatic efforts by Lithuania and Romania over its role in these cases. The Lithuanian prosecutor-general’s office opened a criminal investigation in January 2010 following a parliamentary inquiry that confirmed the existence of two black sites and that Lithuanian airports and airspace had been used for CIA-related flights. One year later, the case was abruptly closed for lack of evidence.

Following the release of the US Senate summary of the still classified 6,700-page report documenting the CIA’s detention and interrogation program, the prosecutor general’s office claims to have sent a formal request for legal assistance to US authorities. In April 2015, it announced it was reopening its investigation, which remains ongoing.

Romania opened a criminal investigation in 2012 following a complaint by al-Nashiri but it is still pending and no information has been made public. A parliamentary inquiry that began in December 2005 and concluded in March 2007, found no evidence of a secret CIA prison, illegal prisoner transfers, or Romanian involvement in the CIA’s program. The European Court raised concerns in paragraph 651 of its judgment that the delay in the investigation meant that crucial flight data had been erased.

As Human Rights Watch also noted:

Romania and Lithuania are not the only European countries implicated in the CIA renditions program. The European Court has already condemned Poland for its role in the rendition, detention, and torture of both of these men, Macedonia for its involvement in the CIA’s abduction and illegal transfer of Khaled Al-Masri, a German citizen, and Italy for its role in the abduction of Hassan Mustapha Osama Nasr, an Egyptian cleric better known as Abu Omar, to Egypt.

There is also credible evidence from the United Nations, the European Parliament, and Council of Europe that many other European countries – including Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Spain, Sweden, and the UK – were involved to various degrees. The UK recently made a formal apology to two Libyan nationals in whose rendition it was involved, and Sweden has apologized to and compensated two Egyptian nationals for its involvement in their rendition.

Of these, only Italy has prosecuted anyone in relation to the program – convicting two Italians and, in absentia, 23 US agents for abducting the Egyptian cleric.

In a briefing paper, Helen Duffy, one of Abu Zubaydah’s lawyers, after noting that “Lithuania was the last European state to allow the CIA to operate such a centre on its territory from 2005 to 2006, and one of an estimated 57 states to have participated in the ERP” (the extraordinary rendition and torture programme), pointed that, although the judgment “focused on Lithuanian responsibility … in an unusually long and detailed judgment the Court also provided a comprehensive review of the facts in relation to our client’s case, and ERP in general. As such, it makes an important contribution to the historical record in an area that the Court noted remains ‘shrouded in secrecy.’”

I made my own contribution to piercing that shroud of secrecy in 2009, when I was the lead writer of a UN report into the US’s post-9/11 secret detention program, and I’m delighted that these rulings have been delivered by the European Court of Human Rights, especially as the US, under Donald Trump, has taken such a backwards step on torture with the confirmation as CIA Director of Gina Haspel, who was in charge of the first CIA “black site” in Thailand towards the end of its existence in late 2002, when both Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri were held there.

Back in 2014, when the European Court of Human Rights condemned the Polish government for its involvement with the CIA “black site” on is soil, it was, of course, impossible not to be struck by how the US itself was as determined to obstruct justice as the European Court was in exposing crimes that America had absolutely no justification in trying to hide.

Four years later, the contrast between the European Court’s exposure of injustice and lawlessness, and the US’s ongoing obstruction is even more pronounced, and urgently needs addressing.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 1, 2018

Guantánamo Scandal: The Released Prisoners Languishing in Secretive Detention in the UAE

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months of the Trump administration.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

There’s been some disturbing news, via the Washington Post, about former Guantánamo prisoners who were resettled in the United Arab Emirates, between November 2015 and January 2017, after being unanimously approved for release from Guantánamo by high-level US government review processes.

23 men in total were sent to the UAE — five Yemenis in November 2015, 12 Yemenis and three Afghans in August 2016, and another Afghan, a Russian and another Yemeni in January 2017, just before President Obama left office, as he scrambled to release as many prisoners approved for release by his own review processes as possible before Donald Trump took office.

All were resettled in a third country because the entire US establishment refused to contemplate releasing Yemenis to their home country because of the security situation there, because Congress had, additionally, refused to allow any more Afghan prisoners to be repatriated, and because, in the case of the Russian, it was not considered safe for him to be sent home.

For the Washington Post, Missy Ryan reported that, despite being unanimously approved for release, because of assessments that they did not pose any kind of significant threat to the US, the men “have disappeared from public view, largely cut off from the outside world since their transfer to a secretive rehabilitation program run by the United Arab Emirates,” adding that they “have had limited contact with their families, some for more than two years, and have not been told when they might be released,” according to their relatives, their attorneys, and current and former US officials who spoke to the Post.

As Missy Ryan explained, “Their uncertain fate exposes the limits of the United States’ ability to track and safeguard inmates resettled overseas” as part of efforts to close the prison, and “highlights the consequences of the Trump administration’s decision to close a State Department office tasked with overseeing Guantánamo matters” — the office of the envoy for Guantánamo closure, which existed from 2013 until the end of Obama’s presidency, and organized the resettlement of former prisoners, as well as monitoring those released.

Just two months ago, the consequences of Trump’s actions were starkly revealed when two former prisoners resettled in Senegal were repatriated to Libya, where they subsequently disappeared into the custody of a militia associated with grave human rights abuses. One of the men had wanted to return to Libya, but the other emphatically did not, and yet, under Trump, the US government no longer has any practical involvement in monitoring former prisoners or making any kind of representation on their behalf.

Regarding the 23 men sent to the UAE, Missy Ryan stated that, in interviews with attorneys for 19 of the former prisoners, the Post “found that few, if any, of the 23 men transferred to the UAE between 2015 and 2017 have been released, despite what attorneys said were informal assurances that they would be out within about a year.”

At the time of the men’s release, the circumstances of their resettlement were unclear, but it is alarming to hear that they were supposed to be held for “about a year” after their transfer, because they had already gone through rigorous review processes in the US to establish that it was safe for them to be freed, not for them to be transferred to another form of imprisonment. We cannot stress enough how disappointing we find this seemingly endless refusal to actually release men no longer regarded as posing a significant threat to the US.

And yet, in the Post’s words, the rehabilitation program in the UAE, “[l]ike a well-known program in Saudi Arabia,” was “designed to ensure that prisoners weren’t radicalized,” as well as ensuring that they “could adapt to outside life.”

Missy Ryan noted that one of the Afghans, Haji Wali Mohammed, an Afghan citizen who had been “held at Guantánamo for 14 years before he boarded a plane in January 2017 and prepared to begin what his attorney was informed would be a temporary rehabilitation program in the UAE,” has become “very hopeless” after more than 16 months at the UAE-run center, according to his son, Abdul Musawer, who has occasionally been allowed to speak with his father by phone.

From his home in Afghanistan, Abdul Musawer said, “The U.S. government said my father would be freely living with his family, but they lied.”

The Post noted that “some of the men transferred to the UAE report satisfactory conditions and appear to be progressing through a program granting prisoners greater liberties over time,” but that “others remain under restrictions and express mounting distress.”

Lawyers and family members stated that “some of the men have not been permitted to use the Internet or go outside,” adding that “[p]eriodic phone calls to family members are typically limited to five minutes, and are sometimes cut off if the conversation veers into politics or conditions at the center.”

In the case of Ravil Mingazov, the Russian, who was resettled in the UAE in January 2017, his mother, Zukhra Valiulina, said that, in a recent call to his family, he “suggested that conditions were worse than at Guantánamo.” In a phone interview, Valiulina said that her son said, bluntly, “Mama, this is a prison.”

In the case of Obaidullah, an Afghan once put forward for a military commission trial under George W. Bush, whose military lawyers then traveled to Afghanistan to establish that the government had no case against him whatsoever, his civilian attorney, Anne Richardson, explained that his family “was able to visit him early in his time in the UAE,” after his transfer in August 2016, but that “subsequently he was out of touch with his family for more than a year.”

Richardson said, “This seems like indefinite detention all over again,” and Missy Ryan noted that, although prisoners at Guantánamo are quite severely cut off from the outside world, “the U.S. military has allowed periodic visits by lawyers and the Red Cross, and provided certain information to the media. Not so in the UAE.”

Establishing detailed information about conditions in the UAE has generally been quite difficult. Some attorneys said that “their former clients have reported satisfactory conditions to their families, possibly because they are in the later stages of the program,” and some of the former prisoners “have received multiple visits from family members.” Ryan also noted that “UAE authorities have provided visas and money for other families.” It is not known how or why some prisoners are being treated better than others.

As Ryan also explained, however, “No matter the conditions, nearly everything about the UAE program remains secret, even its location. Attorneys and relatives of the men say at least some have reportedly been moved to a new site in recent months.”

The Post also noted that UAE officials refused to respond to requests for information about the former prisoners, and a State Department spokeswoman only provided a woolly hope that the former prisoners “would be integrated into their new countries.”

Some of the attorneys have said that “they have been unable to get even basic information” about their former clients. As the Post explained, “In letters this year to the State Department and the UAE’s Foreign Ministry, several lawyers requested the men be visited by their families and the Red Cross. They also asked for a time frame for their release and ‘clarity on the rights they will have.’” They added that previous entreaties “have either been met with silence or with contradictory instructions.”

The Post also explained that “Rep. Eliot L. Engel (N.Y.), the top Democrat on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, blamed the Trump administration for shutting down the State Department’s Guantánamo office, which negotiated the transfer agreements and followed up on resettled detainees.” As Rep. Engel said, “The U.S. government made commitments to protect our security and the rights of former detainees. On both counts, the administration is utterly failing to meet its responsibilities.”

That is undoubtedly true, and former envoys Daniel Fried and Lee Wolosky have been critical of the Trump administration’s position, as we explained in an article in April last year, Shutting the Door on Guantánamo: The Significance of Donald Trump’s Failure to Appoint New Guantánamo Envoys. More recently, after the Libya fiasco, both men spoke out about how Trump’s position was dangerous for national security, as well as being diplomatically disastrous — see here and here.

Attorneys for the former prisoners told the Post that “they were never permitted to see the agreements but were told by the State Department that the men would cycle through the UAE program and gradually be granted greater freedoms, at first inside and then outside the facility.”

Gary Thompson, who represented Ravil Mingazov, and previously “represented another Guantánamo prisoner who went through the Saudi program before being released,” said, “We felt that, because this was the established practice, this was great. However, weeks became months and months became over a year. It started to slip away, and then calls to his family became very brief and sounded funny. We just can’t figure out what’s happening.”

Former officials told the Post that the UAE, a close U.S. ally, “agreed to take the detainees and establish the rehabilitation center as a favor to President Barack Obama,” but those who worked on the transfers said that “the extended detention in the UAE violates the spirit of that arrangement.”

One former official said, “It is one thing to put the guys in a rehab program, or otherwise evaluate them for a short period, but this seems like the UAE is imprisoning them on behalf of the U.S. government. That wasn’t the deal and isn’t right.”

Other former officials apparently “voiced confidence” that the UAE authorities “would make appropriate judgments about the inmates’ readiness to be released,” but as I stressed above, these are men whose appropriateness for release had already been established by high-level US government review processes, and it simply shouldn’t be the case that the UAE is imposing yet another obstacle in a seemingly never-ending set of obstacles to the men ever being granted freedom.

Previously, I have compared getting released from Guantánamo to being let out of an airlock — but only into another airlock — with this process repeated apparently ad infinitum. It is unjust and unfair, and it should be brought to an end with all the men released and allowed to start the process of rebuilding their lives.

Steve Vladeck, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, explained, as the Post described it, that “U.S. law did not impose any obligations on the government once detainees were no longer in its custody.” As he said, “Once we cut ties, there really aren’t remedies under U.S. law.”

Gary Thompson added that “the situation was even more frustrating than Guantánamo.” As he described it, “Before, we could at least file a petition for habeas corpus, we could at least get on a plane and go to Guantánamo. We at least had procedures, even if they were kangaroo procedures. This is deeply frustrating because there is no process.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

It’s 33 Years Since the Battle of the Beanfield: Is It Now Ancient History, in a UK Obsessed with Housing Exploitation and Nationalist Isolation?

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist.

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist.

Please also note that my books The Battle of the Beanfield and Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion, dealing with the topics discussed in this article, are still in print and available to buy from me. And please also feel free to check out the music of my band The Four Fathers.

For anyone attuned to the currents of modern British history, today, June 1, has a baleful resonance.

33 years ago, on June 1, 1985, the full weight of the state — Margaret Thatcher’s state — descended on a convoy of vehicles in a field in Wiltshire, in a one-sided confrontation in which around 420 travellers — New Age travellers, as they were sometimes referred to at the time — were attacked with serious and almost entirely unprovoked violence by 1,400 police from six counties and the MoD, armed with truncheons and riot shields.

The violence that took place that day was witnessed by few media outlets, most of which had been told to stay away, as the state prepared to deal with the latest “enemy within,” so designated by Margaret Thatcher, drunk on power, who, over the previous year, had dealt a crippling blow to Britain’s mining industry, and was now sending her paramilitarised police force out to Wiltshire to do the same to a small group of anarchists, self-styled modern gypsies, green activists and peace protestors.

The state’s excuse for the violence of June 1, 1985 was that the convoy was travelling to Stonehenge to set up what would have been the 12th free festival in the fields opposite the ancient sun temple, and had ignored an injunction preventing them from doing so.

The Stonehenge Free Festival, started in the first flush of widespread counter-cultural dissent in the UK in the early 1970s, which also saw a civil servant prankster, Bill ‘Ubi’ Dwyer, set up the Windsor Free Festival in the Queen’s backyard, had grown throughout the late 70s and into the 80s from its humble origins as the brainchild of another eccentric individual, Wally Hope, into a month-long anarchic gathering, attracting tens of thousands of people, the centrepiece of a season of free festivals that was an alternative economy for the core members of the travelling community.

Although the festivals’ alleged desecration of Stonehenge and its surroundings was Margaret Thatcher’s excuse for decommissioning the convoy with such violence on June 1, 1985, there were other, more significant reasons that the establishment, for the most part, didn’t want to discuss: the fact that the travellers’ movement consisted largely of young people who had bought old vehicles cheaply and had taken to the road because of chronic unemployment in Thatcher’s Britain; the fact that the travellers’ very existence provided a potent challenge to long-standing notions of land ownership in the UK; and the inconvenient truth that the travellers were also engaged in challenging the British state’s approach to militarism and the environment.

In the early 80s, a contingent of travellers — the Peace Convoy — had supported the women of Greenham Common, who set up a permanent women’s peace camp to oppose Thatcher’s plans to allow the US to establish a cruise missile base on UK soil, at RAF Greenham Common in Berkshire. At the same time, a second peace camp was also established at RAF Molesworth in Cambridgeshire, where plans were announced for a second cruise missile base. In the summer of 1984, travellers joined that peace camp, creating the Rainbow Village, consisting of a mixture of environmental activists, travellers and Quakers. Environmentalism, alternative energy and opposition to nuclear power were also key elements of the ethos of the time, widely embraced by the travellers.

Thatcher recognised that the state couldn’t be seen to inflict mass physical violence on the women of Greenham Common, but the peace camp at Molesworth included men, and so, on February 6, 1985, 1,500 troops, the largest peacetime mobilisation of troops in modern British history (symbolically led by the defense secretary Michael Heseltine) evicted the camp. The travellers were subsequently harried from site to site across southern England until the final showdown at the Beanfield.

Traumatised, and with their homes — their vehicles — destroyed, the Stonehenge convoy never recovered from the Beanfield, and an annual militarised exclusion zone around Stonehenge prevented the revival of the free festival, but elsewhere Thatcher underestimated the counter-cultural spirit of 1980s Britain, as a new recreational drug, Ecstasy, arrived on the scene, fuelling a brand-new youth movement, the rave scene, which rapidly began attracting millions of people to illegal parties in warehouses and fields across the country, in defiance of new laws passed after the Beanfield, in the Public Order Act of 1986, which were designed to impose restrictions on “public assemblies.”

Raves and road protests

Prevented from travelling freely around the country, would-be dissenters also came up with a creative response that the state never foresaw. Instead of travelling around, which was fraught with problems, they stayed in one place, targetting road expansion projects that were characterised as an assault on the spirit of the land, and setting up protest camps, beginning with Twyford Down in 1992, where an extension to the M3 was planned, and, in many ways, culminating in 1996 with massive resistance to the nine miles of the A34 Newbury bypass in Berkshire. Along the way, there was huge resistance to the M11 Link Road in east London, which destroyed numerous streets and public spaces, and although almost all the resistance movements failed to prevent the new roads from being built, the government largely abandoned its road expansion plans in November 1995, cancelling 300 planned projects.

As dissent grew, the remains of the traveller movement mixed with the rave scene, creating hybrid events that culminated in the symbolic revival of the Stonehenge spirit at Castlemorton Common in Worcestershire over the Whit bank holiday weekend in May 1992, a counter-cultural melting pot attended by tens of thousands of people.

As dissent grew, the remains of the traveller movement mixed with the rave scene, creating hybrid events that culminated in the symbolic revival of the Stonehenge spirit at Castlemorton Common in Worcestershire over the Whit bank holiday weekend in May 1992, a counter-cultural melting pot attended by tens of thousands of people.

The road protest movement also drew from the rave scene’s energy, with such notable creations as Reclaim the Streets, which took back roads as public spaces, and, on one memorable occasion in July 1996, occupied the M41 motorway in west London, with activists drilling holes in the tarmac and planting trees.

The response to Castlemorton in particular was the Criminal Justice Act of 1994, which further clamped down on trespass and the right of assembly. The heavy-handed legislation, which, notoriously, gave the police powers to shut down events featuring music “characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats”, undermined the rave scene, and, more depressingly, legitimised its wholesale commercialisation, leading to what Vice magazine, in an article on the Beanfield in 2015, described as paving the way for “your V Festivals, ‘Morning Gloryville’ raves and nightclubs that charge £20 on the door and £5 for a bottle of water.”

Nevertheless, dissent remained wilfully unstifled, as the anti-globalisation movement, which arose in response to the rise of transnational capitalism, and, of course, brought people together across national borders, became the focus for riotous dissent in the late 90s, with one notorious day of action, the Global Carnival Against Capital, on Friday June 18, 1999 (also known as J18), seeing the mass occupation of the City of London alongside other events around the world.

However, by 2001, unfortunately, the tide was turning. In Genoa, in July 2001, Italian police murdered a protestor, and just two months later, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 changed the human rights and civil liberties landscape enormously, effectively neutering violent or threatening dissent of any kind, and providing cover not only for an enforced culture of general obedience, but also for the creation of a cynical climate of fear, endlessly reinforced via the compliant mainstream media.

The shallow, materialistic new world order

With the quelling of dissent, the main preoccupation of the new cross-party power establishments in the West, including, in particular, the Labour Party in the UK (the New Labour government of Tony Blair) was to rewrite the basis of existence in what, in many ways, must be seen as the ultimate fulfilment of Margaret Thatcher’s dream: one with a neutered underclass, with everything done as much as possible to enable the rich to get richer, and with shallow materialism and greed as the drivers of the economy, and the only arbiters of value and success in society as a whole.

From when travellers broke out of the despair of working class unemployment in the 1980s, this blunt new world of rapacious capitalism has not only reinforced joblessness, it has also involved seizing people’s homes through economic strangulation or actual physical destruction, creating a housing bubble that has now been in existence, propped up by successive governments and the banks, for 20 years, with only one minor blip following the global financial crash of 2008, when criminal bankers crashed the economy, and had to be bailed out by their victims.

Accompanying the strangling of individuals via rents and mortgages, the establishment is also physically destroying social housing, levelling council estates to replace them with unaffordable properties bought up by foreign investors, and determined to keep the poorer half of society so suppressed and so economically challenged that they can’t even think about unrest, let alone engage in it.

And, accompanying this economic rape, the establishment has also been engaged, for most of the time since the last exuberance of widespread dissent in the 1990s, with efforts to exterminate any notion of class consciousness, replacing it instead with misplaced anger at the EU, and dangerous hostility towards immigrants.

The result has been disturbingly successful — the EU referendum in June 2016, in which a small majority of those who could be bothered to vote called for us to leave the EU in a referendum that was only advisory but that has since been treated as “the will of the people” by deranged isolationist Tories and the mostly complicit mainstream media. Predictably, accompanying this result, the UK has also seen an attendant rise in racism and xenophobia.

Every EU national I meet has been subjected to abuse — verbal or otherwise — since the referendum, and the isolationist vitriol seems to know no limits. Islamophobia, ever-present since 9/11, remains ramped up, permanently reinforced by the media, traditional racism is ever-prevalent through the general flint-heartedness towards the victims of the greatest humanitarian crisis in our lifetimes — a tsunami of refugees, mostly created by our own foreign policy decisions, and our ever-rapacious economic exploitation of weaker economies — and even skin colour is no longer a barrier to prejudice, with Eastern Europeans targeted just as ruthlessly as traditional non-white victims of racism.

Racism has never been even vaguely suppressed, but 33 years ago, at the time of the travellers’ movement, the free festival scene and the Battle of the Beanfield, there were major cultural movements against it, as well for women’s rights, and for gay rights as well, and I regard the progress made on all three fronts as the three great achievements in the lifetimes of those of us who grew up between the late 60s and the 1980s.

At the time of punk, we were also listening to militant roots reggae music, and British reggae bands like Steel Pulse and Misty in Roots were very much part of the festival scene, just as dub music became, essentially, part of the very DNA of the music of the counter-culture.

I wouldn’t want to say that all music has subsequently been neutered, but much of it has, sadly, as materialism, wealth and status have become the dominant cultural indicators of success. Although it’s invigorating to see a grime artist like Stormzy challenge the government for its inaction regarding last June’s Grenfell Tower fire at this year’s Brit Awards, in general it’s fair to say, I think, that consumption has replaced revolt, and selfishness has replaced solidarity.

From today’s perspective, not only do free mass gatherings now seem inconceivable, as the festival season gets underway, with its multitude of commercial festivals for those with money (often literally taking place in fortresses erected specifically to keep everyone else out), but resistance to the type of exclusion that prompted people to get on the road in the 70s and 80s also seems remote, even as those in social housing have their homes knocked down, and more and more people are forced into the arms of private landlords, who are free to exploit them with almost no restraints whatsoever on their greed or their behaviour.

Rise up!

Surely something of the spirit of dissent still exists, to rise up if the current culture of ever-increasing inequality and class cleansing continues, as it seems certain to do if it continues to meet no resistance. For decades, we fought back, tooth and nail, against our exploiters and our destroyers — oppressors from the ruling class in our own country, and from those who, like Margaret Thatcher, despised the working class, without being so gullible that we would divert our energy onto invented enemies from elsewhere. Nothing has fundamentally changed, except we have been encouraged to forget ourselves, and to look everywhere except where we should to see who is responsible for the state of the world, and the increasingly parlous state of the UK.

Can we wake up, and soon? I certainly hope so. As Shelley wrote in ‘The Masque of Anarchy’, written in 1819 after the Peterloo Massacre, in which 15 people were killed by the state:

Rise, like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number!

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you:

Ye are many — they are few!

If you haven’t yet seen it, do watch ‘Operation Solstice’, the 1991 documentary about the Battle of the Beanfield, and the subsequent trial, directed by Gareth Morris and Neil Goodwin:

Note: For more on the Beanfield, see my 2009 article for the Guardian, Remember the Battle of the Beanfield, and my accompanying article, In the Guardian: Remembering the Battle of the Beanfield, which provides excerpts from The Battle of the Beanfield. Also see The Battle of the Beanfield 25th Anniversary: An Interview with Phil Shakesby, aka Phil the Beer, a prominent traveller who died six years ago, Remember the Battle of the Beanfield: It’s the 27th Anniversary Today of Thatcher’s Brutal Suppression of Traveller Society, Radio: On Eve of Summer Solstice at Stonehenge, Andy Worthington Discusses the Battle of the Beanfield and Dissent in the UK, It’s 28 Years Since Margaret Thatcher Crushed Travellers at the Battle of the Beanfield, Back in Print: The Battle of the Beanfield, Marking Margaret Thatcher’s Destruction of Britain’s Travellers, It’s 29 Years Since the Battle of the Beanfield, and the World Has Changed Immeasurably, It’s 30 Years Since Margaret Thatcher Trashed the Travellers’ Movement at the Battle of the Beanfield, It’s Now 31 Years Since the Battle of the Beanfield: Where is the Spirit of Dissent in the UK Today? and, most recently, Never Trust the Tories: It’s 32 Years Today Since the Intolerable Brutality of the Battle of the Beanfield.

For my previous reflections on Stonehenge and the summer solstice from 2008 to 2015, see Stonehenge and the summer solstice: past and present, It’s 25 Years Since The Last Stonehenge Free Festival, Stonehenge Summer Solstice 2010: Remembering the Battle of the Beanfield, RIP Sid Rawle, Land Reformer, Free Festival Pioneer, Stonehenge Stalwart, Happy Summer Solstice to the Revellers at Stonehenge — Is it Really 27 Years Since the Last Free Festival?, Stonehenge and the Summer Solstice: On the 28th Anniversary of the Last Free Festival, Check Out “Festivals Britannia”, Memories of Youth and the Need for Dissent on the 29th Anniversary of the last Stonehenge Free Festival, 30 Years On from the Last Stonehenge Free Festival, Where is the Spirit of Dissent?, Stonehenge and the Summer Solstice, 30 Years After the Battle of the Beanfield and Summer Solstice 2017: Reflections on Free Festivals and the Pagan Year 33 Years After the Last Stonehenge Festival.

Also see my article on Margaret Thatcher’s death, “Kindness is Better than Greed”: Photos, and a Response to Margaret Thatcher on the Day of Her Funeral.

[image error]Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (click on the following for Amazon in the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from six years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of a new documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 30, 2018

2,000 Views of The Four Fathers’ Video ‘Grenfell’, Remembering Those Who Died and Calling for Those Responsible to be Held Accountable

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist.

Please support my work as a reader-funded investigative journalist, commentator and activist.

Today is 350 days since the defining UK-based horror story of 2017 — the fire that engulfed Grenfell Tower in north Kensington, in west London, on June 14, 2017, killing 71 people, and leading to the death of a 72nd person this January. You can find profiles of all 72 victims here.

Last summer, I wrote a song about the fire for my band The Four Fathers, lamenting those whose lives were so “needlessly lost”, and calling for those responsible — “those who only count the profit not the human cost” — to be held accountable. We first played it live, at a benefit gig for a housing campaign in Tottenham, in September, recorded it with a German TV crew at the end of October, and released the video in December, and we have continued to play it live across the capital and elsewhere, making a small contribution to the effort to refuse to allow those responsible for the disaster to move on without a serious change in the culture that allowed it to happen.

That culture — cost-cutting in the search for profits, rather than ensuring the safety of tenants and leaseholders — came from central government, from Kensington and Chelsea Council, from the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation, which had taken over the management of all the borough’s social housing, and from the various contractors involved in the lethal refurbishment of the tower, when its structural integrity was fatally undermined.

Yesterday, we reached something of a milestone with the video, reaching 2,000 views on YouTube and Facebook. If you haven’t yet heard the song, do check it out, and please share it if you appreciate its sentiments. We are finally planning to record it in a studio soon — and hope that will enable its message to get out to a wider audience.

For the video, see below (and you can find it on Facebook here):

As for accountability, the official inquiry into the fire, set up by Theresa May, only began last week, and has, to date, focused its attention not only those responsible for the fire, but on the heart of its impact — the lives of those who died, delivered in profoundly affecting testimony by the survivors. For detailed daily reports by the Guardian, see Day One, Day Two, Day Three, Day Four, Day Five, Day Six and the final day of tributes today.

For a country still riven by issues of race and class, and with the lamentable recent upsurge in anti-immigrant sentiment, the tributes have shown the wonderfully rich and caring lives of so many of the victims — real people, not statistics in lazy, biased reports that try to tar anyone in social housing as inferior to owner-occupiers, and, generally, as some sort of criminal underclass.