Seth Mnookin's Blog, page 5

May 15, 2012

More media stupidity: Chicago Sun-Times runs propaganda piece for Jenny McCarthy’s anti-vaccine conference

On Sunday, in honor of Mother’s Day, the Chicago Sun-Times ran a puff piece on native daughter Jenny McCarthy. This is closer to a press release than it is to journalism:

On Memorial Day weekend, Jenny McCarthy will bring a little bit of L.A. glamor to her hometown, Chicago, for a cause that is close to her heart. The TV star’s philanthropic organization, Generation Rescue, and Autism One [sic] have paired up to offer a conference for parents to learn about new support and treatment methods for their children with autism. … McCarthy will be a keynote speaker at the conference, which, for the second year in a row, is free for the entire weekend to ensure that families of all income levels can attend and learn more about treatment for their children with autism.

The piece also recommends a “hip cocktail fund-raiser” that McCarthy is holding, and ends with this shocker: “The Sun-Times proudly supports Generation Rescue & Autism One [sic].” As Carl Zimmer put it when he got to that line, “Huh???????”*

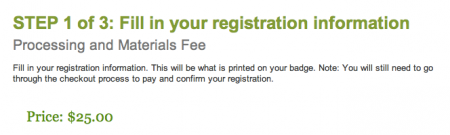

I’m not going to go all TLC and catalog the errors in the Sun-Times piece, but I will point out that apparently “free” means something different in Chicago than it does in the rest of world: Check out the conference’s registration page:

(There’s also a $125 charge for the gala dinner, a $35 charge to attend the “mixer,” and a $250 charge for anyone seeking CME credit.)

I’m also not going to get into Jenny McCarthy’s history; there are plenty of places to go if you want to learn about her history of promoting dangerous and false misinformation about vaccines. But I thought that perhaps fewer readers were familiar with AutismOne. Its annual conference is not, as the Sun-Times claims, a place for “parents to learn about new support and treatment methods for their children with autism”; it’s more akin to Woodstock for vaccine deniers. Take a look at some of the presentations scheduled for this year:

* More Vitamin D, No Vaccines, Virtually No Autism

* Know Your Vaccine Exemption Rights

* Hurt and Healing After Mercury-containing Vaccines

* FOIA Exposes CDC Lied Claiming Mercury in Vaccines is Safe

* Vaccine Nation: A Novel Dramatizing the Vaccine Safety Debate

* Vaccine Manufacturing Practices and Residual Vaccine Contaminants

* Hidden in Plain Sight: the Role of Vaccines in Chronic Disease

* Prospects for Justice for Children Injured by Vaccines: The Experience of the Omnibus Autism Proceeding

There are plenty of other presentations that don’t include the word “vaccine” in the title but are about vaccines, including “The Biological Basis of Autism: Causation and Treatment” by the father-son tag-team of Mark and David Geier. (From the description: “Important new information will be presented showing how environmental exposures, particularly mercury, are associated with autism…”) The Geiers, for those of you who don’t remember, opened clinics around the country to administer a powerful drug used to chemically castrate sex offenders as a “treatment” for autism. Mark Geier has had his medical license suspended in several states; David Geier is not a doctor; he was charged with practicing medicine without a license in his home state of Maryland.

And, of course, no AutismOne conference would be complete without a “Featured Presentation” by Andrew Wakefield, who this year will be giving a talk titled “The End Game.”

I had several sections in my book about AutismOne — if I get through the rest of my work, I’ll post one later today.

* The second half of that sentence was added at 5:18pm on May 15.

Taking stupid to a whole new level: TLC’s entry for the “Worst piece written about vaccines”

I try not to be surprised by the level of stupid displayed by people working in the information industries — print, television, radio, etc. — which should give you some indication of what level of ignorance is required to make me spit out my coffee, which is what I did when I read a TLC “How Stuff Works” post titled “Why shouldn’t we vaccinate our children?”

I started this post thinking I’d address every problem in the piece, but it quickly became clear that that was going to be too overwhelming. (Mary McCarthy’s evaluation of Lillian Hellman comes to mind: “Every word she writes is a lie, and that includes ‘and’ and ‘the.’”) Instead, I’ll limit myself to one of the piece’s six entries: “Vaccines May or May Not Have a Link to Autism.” What follows is the entirety of the content in that section, followed by the reality of the situation.

TLC: It’s important to point out that the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) states that several intensive studies have found no causal link between vaccines and autism spectrum disorder.

Reality: It’s false to say that the CDC “states” that studies have shown no link; that’s the same tactic birthers use when they say, “President Obama claims that he was born in the United States.” It’s also wrong to say “several” studies have found no causal link. The correct way to, um, state this would be to say, “Hundreds of extensive studies involving millions of children have shown conclusively that there is no link between vaccines and autism.”

TLC: The attention paid to reports of an increased prevalence in autism and vaccines containing thimerosal, a preservative used in vaccines that contains mercury.

Reality: To start with, this sentence isn’t written in proper English — but I guess in addition to not feeling constrained by facts, TLC doesn’t feel constrained by writing in complete sentences. More importantly, as anyone with 0.29 seconds and the ability to use a search engine could tell you, thimerosal was removed from all standard pediatric vaccines, with the exception of some variations of the seasonal flu vaccine, in 2001. (The last children’s vaccines that used thimerosal as a preservative expired in January 2003.) Here’s a timeline detailing all of that, and much more.

TLC: Exposure to heavy metals such as mercury can lead to developmental disorders, and there is definitely mercury in thimerosal, which is found in common vaccines for diseases like rubella, mumps and typhoid.

Reality: This could be one of the dumbest sentences ever written about vaccines…which is really saying something, considering how much dreck is out there. The type of mercury that has been shown to lead to developmental disorders is methylmercury; the type of mercury that’s in thimerosal is ethylmercury. A good parallel of the difference between ethylmercury and methylmercury is that of ethyl alcohol, or ethanol, and methyl alcohol, or methanol: Two shots of the former give you a buzz; two shots of the latter are lethal. What’s more, there has never been thimerosal in the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine — not before 2001 and not since. There’s also not thimerosal in the typhoid vaccine — which, incidentally, isn’t recommended in the United States unless people are traveling to areas of the world where typhoid is endemic.

TLC: However, thimerosal contains low levels of mercury; whether exposure to those low levels of mercury is enough to produce developmental disorders is what’s at issue.

Reality: As indicated above, standard pediatric vaccines do not contain thimerosal. There’s also no “issue” as to whether exposure to the amount of thimerosal contained in vaccines produced before 2001 was “enough to produce developmental disorders.” In 2004, the Institute of Medicine reviewed over 200 scientific studies that examined thimerosal-containing vaccines and autism and concluded that the studies “consistently provided evidence of no association between thimerosal-containing vaccines and autism.”

TLC: It’s a good idea to speak to your physician and conduct some of your own independent research about thimerosal.

Reality: It’s always a good idea to talk to your physician — provided he’s not a dissembling quack like Bob Sears. It’s also good to be informed. But as this stinking load illustrates, there’s a lot of bad — and dangerous — information to be found on the Internets.

May 14, 2012

Meandering Mississippi: An early journalism iBook is all wet

Note: This review also ran on Download The Universe, the excellent science ebook online review that I’m working on along with folks like Carl Zimmer, David Dobbs, PLoS’s own Steve Silberman, Tom Levenson, Annalee Newitz, and many many others. If you’re not a regular DtU reader, here’s what you’re missing: In the past week alone, the site has featured David’s write-up of the Byliner original Farthest North, “a strange, richly told story” about America’s first Arctic hero, and Carl’s review of Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomy, which he christened as “the first great science ebook.”

Meandering Mississippi, by Mary Delach Leonard & Robert Koenig. Published by The St. Louis Beacon. iPad (requires iBooks 2). $.99 iTunes

A little after 10 pm on May 2, 2011, the Army Corps of Engineers detonated explosives along a two-mile stretch of the Bird’s Point levee, just below the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. The goal was to save the city of Cairo, Illinois, which was facing such severe flooding that all but 100 of Cairo’s 2,831 residents had already been evacuated. It was a dramatic event; pictures of the explosions, like the one below, have a vaguely apocalyptic feel.

Since the initial explosions took place at night, reporters sequestered a half-mile away weren’t able to see how fast the water from the swollen river was flowing. In all, officials estimated up to three trillion gallons of water — that’s 3,000,000,000,000 gallons — poured onto the Bird’s Point-New Madrid floodway, comprised of approximately 130,000 acres of farmland and 90 homes.

This is precisely the type of story that The St. Louis Beacon, an online-only news organization launched in 2008 by St. Louis Post-Dispatch ex-pats, describes as its raison d’etre, and a handful of Beacon reporters spents months covering the flood’s aftershocks. In February, the Beacon became one of the first news organizations to use Apple’s new publishing software, iBooks Author, to package its reporting into an ebook.

The greatest virtue of iBooks Author is that it makes putting together a book incredibly easy–but, as Meandering Mississippi illustrates, that’s not always a good thing. The book assembles eight Beacon pieces that were originally published over a two-month period, from May 6 to July 7, 2011. As far as I can tell, they were simply dumped into the iBooks template without any editing, condensing, or updated reporting. I’m one of those old-school romantics that believes that daily journalism really is, as the old saying goes, the first rough draft of history. In order to do its job, each day’s story needs to give the reader enough background to ensure that he won’t feel lost. That context, so important in news reports, becomes deadly when a bunch of pieces are strung together in a row.

Just as frustrating is the fact that errors that were present in the original Beacon stories are reproduced in Meandering Mississippi. Take this Beacon piece, where the floodway is described as ”having been established early 1930s.” “In the” is also missing from the ebook. In other places, new errors actual seem to have been introduced: That same story describes how the Corps regarded the activiation of the floodway “a success”; in Meandering Mississippi, that becomes “asuccess.” Even the editor’s letter that serves as a kind of introduction to this project feels half-baked. It misspells the compound-adjective “long-term” and is signed “Margie” — no last name, no title, nothing. These are all minor points, to be sure, but they add to the overall impression that this was a slapdash effort. If the Beacon isn’t going to take its work seriously, why should we?

But maybe I’m focusing too much on, you know, the words. After all, in a Nieman Journalism Lab piece about Meandering Mississippi, Brent Jones, the Beacon editor that created the iBook, said, “The text carries the basics and the meat of the story, but having all these extra elements” — which Nieman described as “ slideshows, audio, interactive graphics, and video interviews” – ”to add to the book really make it stand out.” Would that that were true. The one video clip that is included is eight, unedited minutes of a Corps press conference on the night of the detonation. At least that’s what I gathered after watching the whole thing: The clip’s headline is simply “Decision Made,” and there’s no caption or other information to go along with it. (I did find some impressive video of the actual detonation — but that was on the Post-Dispatch‘s site.)

There’s also a single audio recording, which is made up of several not-very-informative minutes of talking by the mayor of one of the affected towns; when I looked on the Beacon‘s site, it turns out that was originally a video clip.

The still photographs are, if anything, even more disappointing. As the picture at the beginning of this review shows, there was some striking imagery that was produced on the night the levee was breached. I found that shot, by an AP photographer named David Carson, on The Washington Post‘s site; in contrast, Meandering Mississippi includes a series of small shots that look like they could be anything from a fireworks display to the detonation of a bunch of surface-to-air missiles.

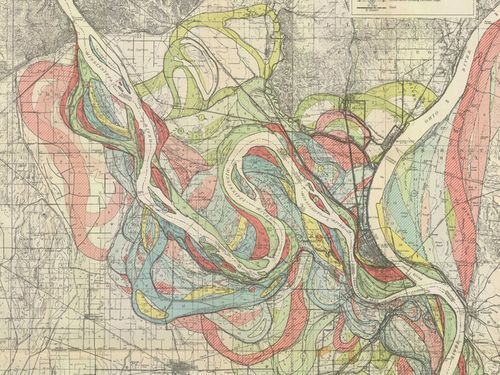

Even more confounding is a series of seven images that are spread out over eight of Meandering Mississippi‘s 54 pages. Only the first one, reprinted below, has a caption; it explains that the images are taken from “a 1944 report to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers by Harold Fisk. The different colored bands represent the courses taken by the Mississippi over time.”

Got that? I didn’t think so. My efforts to figure out what I was actually looking at eventually brought me to a 2010 blog post by Radiolab‘s Robert Krulwich describing these very maps. It was only then that I learned that the white channel traces the path of the river during Fisk’s time. (Krulwich’s piece is well worth reading. He also pastes together all of Fisk’s charts end to end; the result is spectacular. It’s the type of thing I imagine would look great on an iPad.)

The story of the flooding across the Midwest last spring is one that is still evolving: As it turns out, the Corps rebuilding efforts are going better than expected, and the dire warnings of toxic crops and long-term devestation turned out to be overwrought. Hopefully one day, a great book about this saga will be written. Unfortunately, this is not it.

May 11, 2012

E.O. Wilson’s The Social Conquest of Earth: Sloppy, self-indulgent, & unsophisticated

E.O. Wilson is, by any available yardstick, one of the grand scientific figures of the second half of the 20th century. By the time he published his first book in 1967, Wilson, just 38 years old then, had already helped revolutionize the fields of physiology (with his discovery of pheromones) and ecology (with his research on island biogeography). Not bad for a myrmecologist — that’s the technical term for someone who studies ants — from Alabama.

[image error]

The Social Conquest of Earth By E.O. Wilson

(Liveright, 2012) $27.95

As it turned out, he was just getting started. In the 1970s, Wilson published three books (“The Insect Societies,” “Sociobiology,” and “On Human Nature”) that helped create an entire new academic discipline dedicated to studying the biological basis of culture and society. Those books brought him fame and acclaim well outside of the ivied walls of Harvard, which has been Wilson’s academic home since the 1950s: His work was featured on the cover of Time and “On Human Nature” won a Pulitzer Prize.

April 24, 2012

Crap futurism, cruftiness, and walled gardens: A Download the Universe roundtable on e-reading

On April 4, the Pew Research Center’s released an extensive report on the country’s e-reading habits as part of its Internet and American Life project. It is, as is oftentimes the case with Pew reports, quite interesting and exceedingly bland. (You can find an introduction to the Pew report here; the full report is also available online or as a free download.)

As readers of this blog know, I love me some roundtables–and since I recently joined a new online science e-book review called Download the Universe, I figured I had the perfect excuse to gin one up…which is exactly what I did after roping io9′s Annalee Newitz, TIME.com’s Maia Szalavitz, and superhuman science journo Carl Zimmer into it.

Anyone interested in e-reading (or books or words or computers or technology) should check it out. The first entry, “Crap futurism, pleasure reading, and DRM,” ran yesterday; today’s entry is titled “Walled gardens, cruftiness, and a race to the bottom.” (The final entry will go up tomorrow morning.) Here are some samples to whet your appetites:

Maia: The thing that shocked me most about the Pew survey, however, was how little most people read. I suppose I already knew that to some extent, but I had no idea how much we all are outliers.

Seth: That’s interesting–I was struck by how much people read. I’m not sure where it’s from, but I feel like I’ve heard dozens of times over the past several years that the average American adult reads less than a book a year. Given that possibly apocryphal factoid that’s been lodged in my brain, the notion that, as Pew reported, more than 20% of all adults had read an e-book in the past year and a shocking 28% of Americans age 18 and older own at least one specialized device for e-book reading kind of blew me away. It also made me wonder a bit about whether their definitions a little too fluid: That 28% includes tablets, and I think most iPad users don’t regard their iPads as a “specialized device for e-book reading.”

Annalee: The first e-book I ever read was Heart of Darkness on the Sony Libre, the first e-ink device, which I was test driving for Wired in the early 2000s. I don’t think the Libre ever got sold in the U.S., though its underlying technology is what makes the Kindle so nice to read in broad daylight. I remember sitting on the bus with the little device, reading Joseph Conrad’s gooey, beautiful prose, planning to stuff the thing full of every other public domain novel I could.

I wanted to use that e-reader for preservation more than anything – as a place to stow history. And that’s probably why I didn’t pick up another e-reader until a couple of years ago, when I caved in and bought an iPad 1. I’d been leery of the Kindle because it seemed too bound up with Amazon’s creepy DRM-driven business model. Despite the fact that the iPad’s gated garden business model was even creepier — so creepy, in fact, that I wrote an article at io9 about how it was “crap futurism” — it was just too sexy to turn down.

And you know what? I’m glad I gave into my base instincts to get that hot little thing into my hands. Because suddenly I was reading the newspaper every day again. And reading comics! I realized I’d been avoiding both because their form factors were just too flimsy and annoying to hold. Somehow, reading the Guardian newspaper and Scott Pilgrim books became much easier when I had them on my book-shaped iPad.

Seth: There’s an equation I’d like to see: How sexy does something need to be to overcome its creepiness?

Annalee: I think the quick answer is that you have to be able to use the device to read/view open media formats. So if it’s sexy enough to have some openness, then go for it. Or jailbreak it and then go for it.

***

Seth: Carl, as someone who has written “traditional” print books and dedicated e-books, I’m curious if your thoughts about Amazon changed over the past few years–because mine definitely have. David Carr’s recent column in the Times, about how the DOJ should have gone after Amazon, not Apple, if it wanted to take on a monopoly threatening the book business, is just the latest data point that has me wondering whether I’m contributing to my own demise by patronizing Bezos’s warehouse of goodies.

(Some of those other data points: This April 1 Seattle Times story about how Amazon is putting the squeeze on small publishers and this April 15 NYT piece about the same.) I’m also curious as to whether you find Stross’s argument convincing — because I’m not sure I do. Do you really think we’re on the brink of Amazon letting Kindle books out of the garden?

Carl: Stross is arguing that the only way for big publishers to escape Amazon’s lock is to give up DRM (digital rights management), so that you can read their ebooks any way you like, much like you can with a pdf file. A DRM-free ebook would be readable on your laptop, on your iPad with all kinds of apps (not just iBooks), on your Sony Reader (if you still have one), or, yes, even on your Kindle. … The distributor for my ebooks, IPG, got into a tussle with Amazon, which wants distributors and publishers to pay for promotion on the site, to accept sharply lowered costs, and so on. IPG didn’t want to accept the terms, and so–zip!–all 5000 titles they distribute vanished from Amazon (This article in the Times this week details the conflict). I went from having two ebooks on Amazon to none. People can still buy my ebooks if they know where to look, but I’ve taken a huge hit because Amazon was responsible for most of my sales.

My choices are now to bow down to the power of Amazon and work directly with them, on their terms, or to enter that DRM-free wilderness where Doctorow has wandered for years.

Seth: I guess I should have been more clear — I actually do find that aspect of Stross’s argument compelling; what I don’t see is why publishers choosing to un-DRM their books would automatically mean Amazon agree to sell books in something other than the AZW format. Wouldn’t they just say, essentially, bully for you — but if you want to see your books on amazon.com, your going to need to do so under our terms?

I hadn’t realized that your ebooks were distributed by IPG. As someone essentially unaffected by that squabble, I’m rooting for IPG. What are your feelings?

Carl: I’m rooting for IPG too, simply because Amazon is playing such hardball with them, and I don’t like bullying. But I don’t think any short-term settlement between them will last long. IPG depends on access to outlets like Amazon to make money. Amazon doesn’t depend so much on places like IPG. IPG, in its current state, is only good at one thing: distributing books for independent publishers. Amazon, like Google and other web-based giants, is good at many things, and can easily retool itself to become good at many new things. They may have started out as a book dealer, but now they do cloud computing, video streaming, and all sorts of other things that were inconceivable a couple years ago. They can also be their own publisher and distributor, as well as a bookseller.

As I said, the rest of it is over at DtU — which should be a regular destination for you all anyway.

March 26, 2012

Bob Sears: Bald-faced liar, devious dissembler, or both?

Over the past four years, I've encountered a lot of people whose views about science, medicine, and vaccines I disagree with. Many of those people are quite angry with me; I've been accused of being everything from a paid propagandist for pharmaceutical companies to a baby killer. Still, for the most part, I firmly believe that the men and women who are driving the vaccine "debate" are motivated by their genuine conviction that they are doing what is best for children. They're wrong, and the effects of their misguided beliefs are dangerous (and potentially deadly)—but I try to respect where they're coming from and be compassionate about their situations.

Then there's "Dr. Bob" Sears, a first-rate huckster who has made hundreds of thousands of dollars by getting parents to pay for the "alternative" vaccine schedule he peddles in The Vaccine Book. (As of mid-February, Bookscan, which typically captures about 70 percent of book sales, reported total sales of more than 130,000.) I wrote about Sears's bestseller in The Panic Virus (if you're interested in a more complete evisceration of Sears's work, read Paul Offit's analysis in Pediatrics). Here's a brief portion of my analysis:

Sears's questionable assertions are by no means limited to his recommended schedule. In The Vaccine Book, he says that "natural" immunity is more effective than immunity gained through vaccination and implies that parents whose unvaccinated children come down with infections don't regret their decisions. The book's most startling passage, however, is included under the heading "The Way I See It." "Given the bad press for the MMR vaccine in recent years, I'm not surprised when a family . . . tells me they don't want the MMR," he writes. Because there's so little risk of getting infected, "I don't have much ammunition with which to try to change these parents' minds." He, does, however, advise them against talking to their friends about their concerns: "I also warn them not to share their fears with their neighbors, because if too many people avoid the MMR, we'll likely see the diseases increase significantly."

I went on to write about how Sears's downplaying of vaccine-preventable diseases was particularly ironic given what occurred in San Diego in 2008, when "a seven-year-old boy who was later revealed to be one of Sears's patients returned from a family vacation in Switzerland with the measles." Eventually, 11 other children were infected and dozens more were quarantined (some for up to three weeks); it ended up being the largest outbreak in California in almost two decades and cost well over $100,000 to contain.

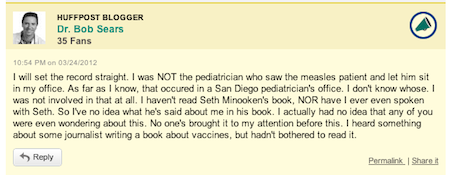

Sears's involvement with patient zero was not some sort of secret: It was also reported in a December 19, 2008 episode of This American Life, in the middle of an interview with Sears himself. (You can hear that part of the broadcast—"That's Dr. Bob Sears. … Dr. Bob, as people call him, is also the doctor for the non-vaccinating family that went to Switzerland"—here. For people interested in the whole show, Sears comes in just before the the 34-minute mark.) It was also reported in Sears's hometown newspaper, The Orange County Register. I wasn't the first person to write about it, and I wasn't the last–but for some reason, Sears has decided now is the time to speak out about this–and he's doing so in the comments of his latest Huffington Post vaccine scare-mongering lunacy.

Now, there are a number of odd things about Sears's comment. First, he denies something that I've never accused him of—not in my book, not in an interview, not in a speech: letting a patient infected with measles sit in his office. Then, he misspells my name, which is either an illustration of how little he cares about getting things right or of his deviousness (or both)—because while I assume it's true he's never spoken to Seth Minooken, he most definitely has spoken to Seth Mnookin. You don't need to take my word for it; as you can hear here, I actually taped the interview. That interview was just one part of a long series of back and forths I had with Sears and various staff members in his office. I think they're revealing—and, in light of Sears's claim that he's never spoken to me (or someone whose name sounds an awful lot like mine), they're worth discussing.

So here goes: On June 17, 2009, I sent an email to Bob Sears's office asking if I could speak to him "for a book I'm writing" about vaccines. I received no response, so on June 23, I wrote back, saying, "I wanted to follow up on an email I sent last week in an effort to find a time to speak with Dr. Sears for a book I'm working on for Simon & Schuster about vaccines."

This time, I did receive a response—not from Sears, but from a media relations staffer. Unfortunately, that response didn't make a lot of sense: "Thank you for following up with me today, we're excited at the possibility of working with you and your client. I'll be in touch, by the end of the day, as promised." Things became a bit clearer when I got another email the following morning:

I apologize for not getting back to you yesterday something came up that consumed my day. I'd like to put together a nice press kit for you but I'm not going to be able to get it to you until tomorrow. But, here's something to start with. We get approximately 50,000 visits a month from Canadian users, 70% of our visits are first time visitors, 30% repeat. I have a report I'll include in the press kit. We'd of course like to book as many impressions as you are willing to give us on a monthly basis, I believe you mentioned 8,000, would 10,000 be out of the question? We generally charge $15 cpm because of our specifically targeted audience, especially thevaccinebook.com is that in the price range you were expecting? Please respond with any general ideas/questions and like I said I'll have a formal press kit for you tomorrow but at least you have some numbers to start with today. Also, what sort of tracking will be used and how would be bill according to tracking?

When I explained that I was not actually interested in advertising on Sears's website but wanted to interview him, I was assured that Sears would be in touch in short order. After not hearing back for two more weeks, I emailed again; still, nothing. Finally, on July 14, Sears wrote to me, claiming that he'd emailed me previously but never heard back. (Perhaps he'd been emailing Seth Minooken.) We arranged a time to speak, but he didn't answer his phone. We arranged a second time to talk, and finally, on July 21, 2009, we conducted our first interview; over the coming months, we spoke one more time and had several email exchanges.

Finally, it seems worth noting that during the entire time I was working on The Panic Virus, never once did a representative from a pharmaceutical company or a government official even obliquely discuss any type of financial arrangement. In fact, there were only two people who did: One of Sears's office minions and the man Sears is embracing in the picture below: Andrew Wakefield.

March 23, 2012

The frozen future of nonfiction: My review of David Eagleman’s Why The Net Matters

One of my favorite events of the year is the annual ScienceOnline conference, which takes place every January in North Carolina: It’s filled with brilliant, funny, and wonderfully nice people. I’ve only attended for the past two years, but both times, I’ve left feeling invigorated and excited about my work.

This year, Carl Zimmer and some confederates (including MIT’s own Tom Levenson) were talking about the number of dedicated ebooks being published that dealt, in one way or another, with science. Within a few weeks, Download the Universe: The Science EBook Review was born.

Earlier today, I posted my first DtU review. It’s a write up of David Eagleman’s 2010 iPad app Why The Net Matters. I think Eagleman is a brilliant scientist, and Sum, his book of shortstories about the afterlife, is a wonderful piece of literature. Why The Net Matters, unfortunately, misses the mark:

The problems start with Eagleman’s premise, which is so vague and broad as to be practically meaningless. There are, he writes, just “a handful of reasons” that civilizations collapse: “disease, poor information flow, natural disasters, political corruption, resource depletion and economic meltdown.” Lucky for us (and Eagleman does offer readers “[c]ongratulations on living in a fortuitous moment in history”), the technology that created the web “obviates many of the threats faced by our ancestors. In other words…[t]he advent of the internet represents a watershed moment in history that just might rescue our future.”

On the other hand, it just might not: In order to make his point, Eagleman either ignores or doesn’t bother to look for any evidence that might undercut it.

You can read the rest of the review here.

The frozen future of nonfiction: My review of David Eagleman's Why The Net Matters

One of my favorite events of the year is the annual ScienceOnline conference, which takes place every January in North Carolina: It's filled with brilliant, funny, and wonderfully nice people. I've only attended for the past two years, but both times, I've left feeling invigorated and excited about my work.

This year, Carl Zimmer and some confederates (including MIT's own Tom Levenson) were talking about the number of dedicated ebooks being published that dealt, in one way or another, with science. Within a few weeks, Download the Universe: The Science EBook Review was born.

Earlier today, I posted my first DtU review. It's a write up of David Eagleman's 2010 iPad app Why The Net Matters. I think Eagleman is a brilliant scientist, and Sum, his book of shortstories about the afterlife, is a wonderful piece of literature. Why The Net Matters, unfortunately, misses the mark:

The problems start with Eagleman's premise, which is so vague and broad as to be practically meaningless. There are, he writes, just "a handful of reasons" that civilizations collapse: "disease, poor information flow, natural disasters, political corruption, resource depletion and economic meltdown." Lucky for us (and Eagleman does offer readers "[c]ongratulations on living in a fortuitous moment in history"), the technology that created the web "obviates many of the threats faced by our ancestors. In other words…[t]he advent of the internet represents a watershed moment in history that just might rescue our future."

On the other hand, it just might not: In order to make his point, Eagleman either ignores or doesn't bother to look for any evidence that might undercut it.

You can read the rest of the review here.

March 22, 2012

This weekend: The workings of the brain, nanotechnology, and the future of science writing

It's been a busy couple of months. Actually, that's a crazy understatement: It's been a tear-my-eyes-out, I'm-so-tired-I-can't-feel-my-feet couple of months. In addition to falling behind on several articles, grading papers, writing recommendations, and doing research, I'm also gotten out of my typical blogging rhythm. I'm hopeful that's about to change.

In the meantime, here's a late-in-the-game announcement about some wonderful events taking place this weekend as part of the MIT Graduate Program in Science Writing's 10th anniversary celebration. From 2pm until 3:30pm on Saturday, Alan Lightman, one of the founders of the program, will be hosting a panel discussion on attention and memory with Robert Desimone, the director of MIT's McGovern Institute of Brain Science; Suzanne Corkin, Professor of Behavioral Neuroscience at MIT; and Florian Engert, an Assistant Professor of Cellular Biology at Harvard University.

Then, from 4pm to 5:30pm, program director Marcia Bartusiak will host a panel on nanotechnology, quantum computing, and molecular biology with Angela Belcher, Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at MIT; Seth Lloyd, Professor of Mechanical Engineering at MIT; and Phillip Sharp, Institute Professor, Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT.

The weekend's festivities wrap up that night with a gala dinner at the MIT Museum, where I'll moderate a discussion with Amy Harmon, a New York Times Pulitzer Prize-winning science reporter, and Kurt Andersen, who, in addition to hosting Public Radio's Studio360, writes remarkable novels and commits frequent acts of excellent journalism. We'll be talking about science writing, covering controversies, the future of the media, and plenty more.

Details about the anniversary are here — hope you can make it!

February 20, 2012

SciWriteLabs 7.3: Long-form narratives, crappy first drafts, and the importance of wasting time

[Note: I discovered this morning that this piece had mysteriously disappeared from my site. I have no idea how that happened. It was initially posted on February 1; I have no way to recover previously submitted comments.]

It's been two weeks since the previous installment of my three-part conversation with Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times reporter Amy Harmon; today, finally, I'm posting the concluding chapter in what has been a fascinating discourse (for me, anyway). These discussions have focused loosely on "Navigating Love and Autism," Harmon's latest story in an ongoing series she's working on titled "Autism, Grown Up."

Today's entry focuses on the peculiar challenges of writing long-form journalistic narratives.

Note: The first part of Harmon and my Q&A, which looked at neurodiversity and some of the issues that arise when writing about autism, is here; the second part, which examined what it means to be a science writer, is here. These interviews are part of an ongoing project called #SciWriteLabs, which examines topics related to science writing and journalism. Of related interest is a recent roundtable I conducted about autism with a group of self-advocates, parents, and writers; the first part of that discussion is here, and the second part, which ran on The Huffington Post, is here. Finally, an obligatory mention: The Panic Virus, my book about the controversies over autism and vaccines, is out now in paperback.

SM: Over the past several weeks, one theme we've kept coming back to is the amount of work that's required for long-form narrative projects. People who don't work in the industry might not realize just how laborious it is to produce a 5,000 or 6,000 word story – and in an era of shrinking news budgets, just how at-risk these types of projects are. Can you talk a bit about what happens before your stories end up in print?

AH: There are different types of long-form narratives, so maybe it's worth explaining first that I tend to do what are sometimes called "story narratives.'' They have a plot and they are told through scenes and dialogue. They also have an argument, or at least a point, embedded in them, but it is often not explicitly stated, or perhaps only stated briefly in two or three "nut graphs" near the top. Like in a novel or a movie, the payoff comes at the end, so you need to make readers care about what happens to these characters, and if you can't, you're kind of screwed, because you then you have nothing.

These are different from explanatory narratives, which weave a story together with direct commentary by the reporter and/or experts the reporter has talked to; or essays, where you strive for a provocative argument; or profiles, where the point is to provide insight into an individual at a particular moment; or investigations. (Nieman Storyboard had a great interview recently with Jack Hart, a former narrative editor at The Oregonian, in which he distinguished between these genres.)

SM: That reminds of a presentation I saw last week by Deborah Blum. She and David Dobbs were speaking about story structure, and Deborah had a series of examples of ways writers can structure a story: By building a pyramid, or an inverse pyramid, or a diamond, or a circle; by weaving a braid, or creating a rainbow, or fashioning a wave. All of those can work – but the key, in every case, is to have the material that makes a reader want to find out more.

AH: Wow, I need a re-do of that presentation. I think that's true, and the challenge for a story narrative, regardless of the structure, is that you're relying exclusively on the scenes and characters to build that suspense.Jonah Lehrer's essay in The New Yorker last week about how to foster group creativity, for instance, made me keep reading because the point he was making was intriguing and the way he argued it was engaging. With my stories, though, if I stepped out of the narrative to directly explain things, it would sound preachy and annoying. So even though I have an implicit argument –"with the right kind of support, it's possible for autistic youth to achieve a level of independence that previous generations have not," say, — I'm trying to always "show" not tell. I don't think this type of narrative is any better or worse than the other kinds – I mostly do them because I'm not that good at the otherkinds. But they do require a different kind of reporting.

SM: What goes into the decision to do this specific kind of narrative?

AH: I think a lot ahead of time about whether I have the right character through which to illuminate whatever the broader cultural trend is that I'm trying to get at. What is the key conflict, how is it most likely to be resolved? How much of it has already happened and how much of it will play out as I watch?

SM: Can you describe what that was like for these stories about autism?

AH: In the first one, "Autistic and Seeking a Place In An Adult World," I wanted to show what I knew was a growing tension for many families and communities as more young adults like Justin seek jobs and a foothold in their communities. When I started following him, he had 18 months to find a job, and I thought it was a good bet that he would land one. "Navigating Love and Autism," the story about Jack and Kirsten, took about two months to do, and I was very nervous about finding a good ending. I got lucky when they decided to get a cat.

SM: Jack's father, John Elder Robison, noted in a comment how much commitment the "Navigating Love" piece took. What, exactly, was involved in that story?

AH: That was so nice of John to say. I did spend a lot of time with them. Between mid-October, when I first spoke to Jack and Kirsten on the phone, and mid-December, when I last saw them, I visited five times for two or three days each time — and when I wasn't there, I talked to them on the phone pretty much daily. We also emailed and IM'd. (At one point I even invented a character in Eve Online, the Internet game Jack is semi-obsessed with, so that I could talk to him in the game, but it crashed my computer so I had to give up on that.)

There was one Saturday near the end of my reporting that I spent in Philadelphia, where John and Jack and Kirsten were giving a day-long workshop to a group of autistic teenagers and their parents. They drove down from Amherst the day before in John's car—about a six-hour drive—and when I called ahead of time to ask if I could ride back with them, John said, "I don't see why you would want to do that." But to me, those six hours were a gift: I used every minute of that car ride to construct the detailed chronology I needed before I could start writing.

SM: When you're interviewing someone, are there times when you know you've just found a perfect scene for some part of your story?

AH: One of my two favorite narrative journalism quotes is from Gay Talese: "I waste a lot of time. It's part of my occupation.'' He was being facetious, but he was also making the point that if you are trying to capture some truth about people's lives, you have to be there for long stretches where not a lot happens. I pretty much take notes on everything, just in case, and when something really perfect happens, even if I'm not consciously thinking "I'm going to use this,'' I know it because my note-taking suddenly becomes frenzied.

It wasn't until the very end of that day in Philadelphia, for instance, that an anxious mother whose teenager has autism asked Kirsten and Jack if they were going to stay together and get married. That question, and Kirsten's answer, turned into a crucial scene in the story:

A mother who had slipped into the room put up her hand.

"Where do you guys see your relationship going in the future?" she asked. "No pressure."

Kirsten looked at Jack. "You go first," she said.

"I see it going along the way it is for the foreseeable future," Jack said.

One of the teenagers hummed the Wedding March.

"So I guess you're saying, there is hope in the future for longer relationships," the mother pressed.

Kirsten gazed around the room. A few other adults had crowded in.

"Parents always ask, 'Who would like to marry my kid? They're so weird,' " she said. "But, like, another weird person, that's who."

It shows how Kirsten and Jack's struggles are relevant to other young adults with autism, and also, I thought, how universal those struggles are. It also speaks to why Kirsten and Jack persevere with each other despite their difficulties. So that was one of those times when I'm just typing furiously, as fast as I can, because I'm worried about missing one crucial word and I'm cursing the fact that I don't have a recorder on, which I never seem to at the most important moments.

SM: I find the writing process to be much more painful and difficult than reporting, which is the part I actually enjoy. Is that also true for you?

AH: I like the very beginning of writing, when you have the illusion that it's going to go really fast, and it's been awhile since you last wrote, and you're kind of remembering that you enjoy playing with words. And I like the very end, when you're not really writing, you're polishing, and it feels like it's getting better with not much effort. In between, it's torture. I mentioned my first favorite narrative journalism quote already – my second is from John McPhee. In an interview in The Paris Review, he talks about how he gets in at nine, and basically procrastinates until five – not by surfing the Web, or anything, just sitting there and TRYING to write. And then at five, he starts to write, and then at seven, he goes home. "So why don't I work at a bank and then come in at five and start writing?'' he says. "Because I need those seven hours of gonging around.''

I think of that pretty much every day at 5:00 p.m. when I am writing, to try to make myself feel better. When I was stuck and totally miserable on the "Navigating Love'' story, Dean Baquet, the Times's managing editor, instructed me write what Anne Lamott calls a "shitty first draft.'' I hated that idea — but he's the managing editor, and I felt like I better do what he said.

So I wrote this awful first draft — and it was kind of a revelation. Making the shitty first draft better was much more fun than trying to write a perfect first draft. Also, on that story, I started writing it on Dec. 5, the day after they got the cat, and I basically did not look up until it ran on Dec. 27. For me, that was very fast, and I think just working straight through the weekends helped, because it's always hard for me to start writing again after I stop for a while. But I probably can't do that too often and maintain cordial relations with my family.

SM: I had a similar experience once, but the editor telling me to stop being so precious was my mother. I was complaining about having writers block, and she made the point that I didn't actually have writer's block — I hadn't forgotten how to write. I was just obsessing about every word I wrote being perfect. Ever since then, I've been aware of how much more comfortable I am revising something that's already on the page than I am starting something new — even if revising really means taking something I was working on and completely rewriting it.

Switching gears: The Times has had a great website for a longtime — but this story really seemed to highlight some of what the paper is trying to do in terms of adding value to stories online. What was involved in putting together the video clips and images that accompanied the piece?

AH: What I loved about the pop-up video clips and images that we used in these stories is that the technology really grew out of the needs of the story. No matter how I tried, I could not convey in mere words how Justin sounded, how he moved, all the subtle—often totally endearing, sometimes off-putting—mannerisms that make people think "he is different.'' And we didn't HAVE to rely on my words, because we had this great video footage that had been taken to accompany the story. It was when we were viewing the video for that first story, which was going to run as a mini-documentary alongside the piece, that the idea emerged to make the video and pictures PART of the story, rather than just running in parallel.

To go back to your first question, all of that requires a lot of work by a lot of great and talented people. I'll just list some so you get the idea: Kassie Bracken shot the video, Patrick Farrell edited the video, Fred Conrad shot the pictures, Josh Williams created the technology behind the "quick links,'' Anne Leigh did the layout. I'm not even mentioning the editors in video, photo and multimedia. Then there were also MY editors: Barbara Graustark and Glenn Kramon, who spent many hours shaping the stories and making them much better, and Kayne Rogers, the copy editor, who polished them. It really is a big production, and I feel very fortunate to work at a place where I can do this kind of story and also have so many people make it better than I could ever hope to on my own.

SM: I think that about does it — at least until March, when you and Kurt Andersen will be up in Cambridge for the 10th Anniversary Celebration of MIT's Graduate Program in Science Writing. Any last words?

AH: I'm now in the phase of looking for my next stories, and I'm remembering how important it is to find the right way to do it t at the outset. Chris Jones, who has won a bunch of awards writing this type of story for Esquire, tweeted something the other day that made me feel justified in spending the time up front. "Idea, reporting, writing, editing. Each as important as the other, but harder to rescue the earlier you lose the string." Scary and true. Wish me luck.

SM: Luck…

Seth Mnookin's Blog

- Seth Mnookin's profile

- 39 followers