Seth Mnookin's Blog, page 2

July 15, 2013

A Jenny McCarthy Reader, Pt. 1: The birth of a star and an embrace of “Crystal Children”

Note: Earlier today, . As many people have already noted, this is an extremely unfortunate move on ABC’s part: It’s giving the network’s imprimatur to someone who has worked, methodically and relentlessly, to undermine public health.

In (dis)honor of McCarthy’s new perch, I’ve decided to post a chapter of my book The Panic Virus titled “Jenny McCarthy’s Mommy Instinct” on the blog. Since it’s well over 5,000 words, I broke it up; this first part is about McCarthy’s rise to fame and her embrace of a different theory regarding her son. There are three more parts: “Jenny brings her anti-vaccine views to Oprah,” “Jenny legitimizes the scientific fringe,” and “The real dangers in following Jenny’s advice.”

Jenny McCarthy’s career in the public eye began in October 1993, when, at the age of twenty-one, she was named Playboy’s Playmate of the Month. Not long thereafter, she was crowned the magazine’s Playmate of the Year, and for much of 1994 she hosted Hot Rocks, an hour-long Playboy Channel TV show that aired “uncensored” music videos.

Her rise to mega-stardom began in earnest in 1995, when MTV hired her to co‑host its new dating show, Singled Out. From the show’s first episodes, it was clear the five-foot, seven-inch native Chicagoan’s appeal had at least as much to do with her fearless sense of humor and the guileless way in which she broke taboos as it did with her bleached blond hair and her buxom physique: Every time she gleefully sniffed her armpits or bragged about the potency of her flatulence, she reminded the world that you didn’t need to be an ethereal waif like Kate Moss or a supercilious beauty like Christy Turlington to be a sex symbol.

By 1996, McCarthy had become one of the most ubiquitous stars in the United States. That year she appeared on two more Playboy covers and bidding wars broke out whenever she announced her intention to work on a new project. In 1997, she had two eponymous shows at the same time—MTV’s sketch comedy program The Jenny McCarthy Show and NBC’s half-hour sitcom Jenny—and was paid $1.3 million by HarperCollins for her quasi-autobiography, Jen-X. Then, in an instant, her appeal seemed to evaporate. Despite a massive promotional campaign, Jenny tanked—its ratings were so bad that it was canceled after a single season—and her book flopped as well.

The stall in her career gave McCarthy a chance to focus on her personal life. In 1999, she married an actor and director named John Mallory Asher, and in 2002 she gave birth to the couple’s first child, a boy named Evan. Shortly thereafter, she became an unlikely publishing phenomenon: A decade after the combination of her just-one-of-the- guys attitude and girl-next-door good lucks made her the object of teenage boys’ fantasies, she discovered that her willingness to openly and honestly tackle subjects other people were too timid (or uncomfortable) to address held a similar appeal for thirtysomething women trying to navigate their way through adulthood. In 2004, she released Belly Laughs, a book about pregnancy in which McCarthy addressed topics like butt-hole problems and pubic hair fiascos; it ultimately sold more than 500,000 copies. Her next book, 2005’s Baby Laughs, didn’t do quite as well, although its sales figure of 250,000 copies still made it an unqualified success.

Then things seemed to unravel once again. Dirty Love, a film McCarthy wrote and starred in and which Asher directed, was released to universally bad reviews: In his zero star write-up, Roger Ebert said the “hopelessly incompetent” film was “so pitiful, it doesn’t rise to the level of badness.” Instead of being refreshingly honest, McCarthy’s attention-getting antics—like the scene in Dirty Love that featured her wallowing in a pool of her own menstrual blood—seemed increasingly desperate and contrived. Even Life Laughs, the third book in her trilogy on early motherhood, didn’t do nearly as well as her previous two books. By the end of the year, her personal life had also hit a rough patch, and she and Asher filed for divorce. To top it all off, Evan, her perfect, blond-haired, blue-eyed little boy, was having problems of his own.

• • •

In the spring of 2006, McCarthy and her son were walking in downtown Los Angeles when a woman approached them. “You’re an Indigo,” the stranger said. “And your son is a Crystal.” McCarthy barely had time to shout, “Yes!” before the woman left as quickly as she’d come.

Indigo Adults and Crystal Children.

That chance encounter served as McCarthy’s introduction to a New Age movement based on the belief that a group of spiritually advanced children known as Crystals are destined to lead humanity to its next evolutionary plateau. (Parents of Crystals recognize each other through the purplish aura they emit, hence their designation as Indigos.) It was only then, McCarthy would say later, “[That] things in my life started to make sense.” Evan had always been a unique kid—he seemed less social and more intense than other children his age—and several doctors had already broached the topic of whether he had a behavioral or developmental disorder.

McCarthy’s embrace of Crystal beliefs gave her the strength to reject doctors’ efforts to squash Evan’s spirit. “The reason why I was drawn to Indigo, and probably many other mothers [are] too, was the fact that my son was given a diagnosis for a behavior issue,” she explained later. “I would not accept this negative label they were trying to put on my son and found out that he mirrored Indigo characteristics. . . . Once moms educate themselves, and find out what other mothers of Indigos do for behavior issues, we generally find the answers and solutions for everything.”

That summer, McCarthy launched IndigoMoms.com, an online portal for Indigos looking to connect with one another. It included a social networking area called “Mommy+Me,” a forum where McCarthy would answer readers’ questions, and an e‑commerce section that offered tank tops and baby doll tees for sale alongside one-year subscriptions to something called a “Prayer Wheel”; the services of McCarthy’s sister, Jo Jo, a “celebrity makeup artist”; and Quantum Radiance Treatment by McCarthy’s friend Nicole Pigeault.

IndigoMoms.com never really caught on, and by the end of the year, McCarthy pulled the plug on the site. (It remains available only through a service that collects archives of Web pages.) As it turned out, by that point McCarthy was already deeply involved with another parent-led movement defined by its opposition to conventional medicine.

May 14, 2013

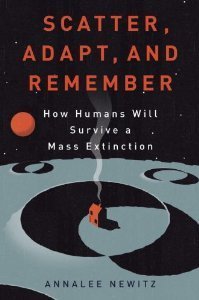

Today at 3pm: A live-chat with “Scatter, Adapt, and Remember” author/io9 editor Annalee Newitz

One of the nicest things about the science writing racket is how many incredible people there are in the field, people who not only are ferociously intelligent and omnivorously curious but are also tirelessly generous and endlessly kindhearted.

Exhibit #1 is Annalee Newitz, the founding editor of io9, the Gawker Media site that covers science, science fiction, and the future.

io9 editor and all-around awesome person Annalee Newitz

If you’ve never read io9, do yourself a favor and rectify that, stat — it’s a great site. Today’s the publication date for Annalee’s latest book, Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction, and it’s a doozy. It’s not easy to pull off a serious work of speculative popular science, but Annalee manages to do it, surveying the history of Earth’s mass extinctions and taking a clear-eyed look at what the future might hold. But you don’t need to take my word for it — here’s a glowing Kirkus review, and, if you want to read some of the book for yourself, here’s an excerpt.

Today at 2pm, I’ll be hosting a live-chat with Annalee on io9 about her book — I’ll ask her some questions generated by the hoi polloi and some of my own. Stop on by and check it out – it’ll definitely be worth it. (Here’s the link, which is live now.) And who knows? You might learn something that’ll help humanity survive the future.

Today at 2pm, I’ll be hosting a live-chat with Annalee on io9 about her book — I’ll ask her some questions generated by the hoi polloi and some of my own. Stop on by and check it out – it’ll definitely be worth it. (Here’s the link, which is live now.) And who knows? You might learn something that’ll help humanity survive the future.

(News and updates about Scatter, Adapt, and Remember can be found on the book’s site, http://scatteradaptandremember.com/.)

April 29, 2013

Credibility in the Age of Twitter: A Town Hall on the Marathon Bombing this Wednesday at the Nieman Foundation

It’s been a hectic, stressful, emotional two weeks here in Boston. As some of you know, I grew up in the area — at the top of Heartbreak Hill, which comes at the end of four miles worth of hills that end just before the 21 mile mark. I’m obviously not the first person to say this, but it’s impossible to overstate how integral the Marathon is to the fabric of the region. From grade school through high school, I would hand out water and oranges at the corner of Commonwealth Avenue and Hammond Street.

My family now lives a few miles down the road, just outside of downtown Boston. On April 15, I took my three-year-old son to the annual Patriot’s Day Red Sox game.

First pitch is at 11:05 am — it’s the only game in all of baseball to start in the morning — which means that it typically gets out just as hordes of marathoners are coming through Kenmore Square, about a mile from the finish line. It’s also one of the only games I can go to with my son, who still takes a pretty serious midday nap.

We left the game in the seventh inning — he’s not a big fan of crowds or sudden loud noises, and I was getting worried about a walk-off win (which, as chance had it, is exactly what happened). We climbed on the T at Kenmore Square a little before 2 pm, and there were a handful of marathoners heading home on the train. We talked to one — gave him a high five and told him he should go to sleep, just like we were planning to do.

By 2:10, my son was asleep and I was starting to do some work on my computer. Fifty minutes later, I got an email from my wife, who works for Boston magazine: “Two bombs went off at Marathon Sports. Many injured. Sirens everywhere around here.”

I spent the afternoon listening to police scanners and tweeting out what I thought was relevant information.

Three days later, I was getting ready for bed when I got an Emergency Alert text message from MIT: Shots had been fired on campus. I got in my car and drove to the site of the where Officer Sean Collier was assassinated — and then followed the police to the site of a carjacking, and then to Watertown, where I tweeted updates until 6 am the next morning, when I finally went back home. (I wrote about that night for The New Yorker.)

I still haven’t processed everything that happened to me, my city, and my workplace — and I’m not sure when I will. It’s easier for me to think about what the events of the last two weeks will mean for journalism — and that’s the topic of an event this Wednesday at Harvard’s Nieman Foundation titled “Timing, Trust, and Credibility in the Age of Twitter.” It’s a town-hall type discussion, and I’ll be there along with:

* Boston Globe metro editor Jennifer Peter

* Boston Globe reporter, 2013 Nieman Fellow, and former Palm Beach Post colleague David Abel

* Boston Police Department chief of public information Cheryl Fiandaca

* WGBH’s “Under the Radar” host Callie Crossley

* Washington Post engagement editor David Beard

There’ll also be some interesting people in the audience, including:

* Andrew Kitzenberg, the Watertown resident who took some of the only pictures of the shootout between the Tsarnaev brothers and police

* Hong Qu, a Nieman fellow developing a program to extract credible, real-time info from Twitter

* Todd Mostak, a researcher at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab

* Dana Forsythe, editor of WickedLocal’s Watertown site

The event is free and open to the public, but you need to RSVP if you want to come. It’ll also be live streamed.

February 24, 2013

Upcoming: Nate Silver and I talk politics, baseball, and more

I have a handful of appearances coming up, including two public talks that are part of MIT’s Communications Forum. The first, which is this Thursday at 5 pm, is a special one indeed: I’ll be holding a Q&A with Nate Silver, the powerhouse behind FiveThirtyEight, the stat-centric political blog that has roiled the punditocracy by forecasting the past two presidential elections with remarkable accuracy.

Nate Silver

Silver, of course, has not always been focused on politics: From 2003 to 2008 he wrote for Baseball Prospectus, and PECOTA, his sabermetric tool for predicting baseball players’ future performance, is one of the most advanced systems developed. In a previous life, I also did some writing about baseball, so that’s a subject we’ll be touching on — as well as the future of the journalism, how to monitor one’s media diet, and more.

The other Communications Forum event is a few months away: On April 11, I’ll be hosting a discussion with Ta-Nehisi Coates and Mark McKinnon. That should be equally lively and interesting; more details closer to the actual date.

There are a few more upcoming events, including a March 8 talk in Chicago as part of the National Foundation on Infectious Disease’s Clinical Vaccinology Course; two panels (on March 14 and 16) as part of the Association of Health Care Journalists’ Health Journalism 2013 conference in Boston; a talk on April 21 as part of the Colorado Academy of Family Physicians’s annual scientific conference; and, on April 23, an open-to-the-public event titled “Vaccine myths, parents, and modern health information” at Seattle’s Town Hall with Wendy Sue “Seattle Mama Doc” Swanson. More details are on my website.

January 21, 2013

New York Times with most detailed account yet of MIT’s role in Swartz case

Late yesterday, Noam Cohen of The New York Times published a nuanced account of the events that led to the arrest of Aaron Swartz in January, 2011 for using MIT’s computer networks to illegally download millions of research articles owned by JSTOR, a non-profit organization that sells subscriptions to academic institutions. Cohen’s piece relied heavily on “internal MIT documents” that, as far as I know, have not been reported elsewhere; these included a “detailed internal timeline” by a senior security analyst employed by the university. It’s is unlikely to change the mind of those already convinced that MIT acted overzealously in investigating the case, but it does fill in some crucial holes in this tragic story.

I think Cohen is correct in locating the key moment in MIT’s involvement in the case in the time between when it discovered its network had been breached and when Swartz was identified as the culprit: “Mr. Swartz’s actions presented M.I.T. with a crucial choice: the university could try to plug the weak spot in its network or it could try to catch the hacker, then unknown.” Cohen also highlights several other factors that came into play at the time: First, that the MIT “tech team detected brief activity from China on the netbook [being used to illegally download the JSTOR articles]— something that occurs all the time but still represents potential trouble.” Second, JSTOR, which notably did not press charges after Swartz was arrested, was less forgiving before his identity was known: According to the account of the MIT employee who was dealing with JSTOR, it viewed the “systematic and careful nature of the abuses…as approaching criminal action.”

Another interesting quote comes from Michael Sussmann, a former federal prosecutor who specializes in Internet and technology law. Once law enforcement was called in to the case — something that occurred before anyone knew Swartz was the perpetrator — MIT’s hands were, Sussmann told Cohen, essentially tied: “After there’s a referral, victims don’t have the opportunity to change their mind.” That was something I’d been wondering about ever since this story broke. Another question I have that has not, as far as I know, been answered: At the time of his arrest, Swartz was a fellow at Harvard’s Safra Center for Ethics — and therefore already had legitimate access to JSTOR. Usage restrictions would have limited his ability to download articles simply using his own login — but why did Swartz use MIT’s network to illegally access JSTOR instead of Harvard’s?

January 13, 2013

MIT president asks for “a thorough analysis” of Aaron Swartz case

For the past several years, Swartz’s life was dominated by a federal investigation related to his Open Access activism: In 2011, he was indicted for breaking into MIT’s computer networks and downloading almost five million scholarly articles from JSTOR. I arrived at MIT, an institute with roughly 1,000 faculty members, a few months after that indictment. It would be folly for me to pretend I had any sense of the overall sentiment of the staff here, but I never heard anyone here speak disparagingly of Swartz — and I heard a lot of people talk admiringly of his efforts.

Swartz was, by his own admission, someone who struggled with acute depression and suicidal thoughts. A few hours ago, MIT president Rafael Reif sent out this email to “members of the MIT community”:

Yesterday we received the shocking and terrible news that on Friday in New York, Aaron Swartz, a gifted young man well known and admired by many in the MIT community, took his own life. With this tragedy, his family and his friends suffered an inexpressible loss, and we offer our most profound condolences. Even for those of us who did not know Aaron, the trail of his brief life shines with his brilliant creativity and idealism.

Although Aaron had no formal affiliation with MIT, I am writing to you now because he was beloved by many members of our community and because MIT played a role in the legal struggles that began for him in 2011.

I want to express very clearly that I and all of us at MIT are extremely saddened by the death of this promising young man who touched the lives of so many. It pains me to think that MIT played any role in a series of events that have ended in tragedy.

I will not attempt to summarize here the complex events of the past two years. Now is a time for everyone involved to reflect on their actions, and that includes all of us at MIT. I have asked Professor Hal Abelson to lead a thorough analysis of MIT’s involvement from the time that we first perceived unusual activity on our network in fall 2010 up to the present. I have asked that this analysis describe the options MIT had and the decisions MIT made, in order to understand and to learn from the actions MIT took. I will share the report with the MIT community when I receive it.

I hope we will all reach out to those members of our community we know who may have been affected by Aaron’s death. As always, MIT Medical is available to provide expert counseling, but there is no substitute for personal understanding and support.

With sorrow and deep sympathy,

L. Rafael Reif

January 11, 2013

Finding time for fun: The Sabeti Lab goes Gangnam Style

One of the last pieces I worked on in 2012 was a profile of Pardis Sabeti for Smithsonian‘s “Innovators” year-end issue. Pardis is an inspirational figure for a number of reasons: Her work has transformed computational genetics; she does everything she can to make sure her research has a positive impact on people’s lives; she is, by all accounts, an amazing and generous mentor.

That said, one of the things I found most impressive about Sabeti was the way she finds time to have fun. Working as a research scientist has always been nerve-wracking and overwhelming; that’s more true than ever these days, when federal funding that’s been taken for granted for the past half-century is being called into question. Every since she was an undergrad, Sabeti has sought out ways to make sure she, and the people around her, are finding time to enjoy life.

Perhaps the reason I found this so striking is that it’s something I’m woefully bad at. Journalism is another frenetic, high-stress profession; the secular changes going on in the industry have added a whole other layer of financial uncertainty to the mix. Despite the personal and professional successes I enjoyed last year (I joined the faculty at MIT; we had our second child), 2012 was an arduous, difficult year, and there were too many days when I neglected to spend some of my time smiling and enjoying my life. I’m not a fan of New Year’s resolutions, but that is one thing I’d like to change in 2013.

I was thinking about all of this today because I came across the Sabeti Lab’s annual holiday card while cleaning out my email inbox. One afternoon when I was working on the Smithsonian piece, I tagged along as Sabeti and two members of her lab scouted an indoor trampoline park as a possible location for the card’s photo shoot. In the end, they decided to eschew flying through the air and went Gangnam Style instead. The result is below…

December 18, 2012

“Electric Shock”: Inspiring new Matter story; reason for hope in the future

Last spring, Jim Giles and Bobbie Johnson, a pair of British journalists who’d written for everywhere from The New York Times and The Guardian to Economist and Wired, announced their intention to launch Matter. It felt, to many of us in the science-writing racket, like a quixotic effort: Was there really pent-up demand for in-depth, independent reportage that covered breaking news about science within the parameters of long-form non-fiction?

To answer ‘yes’ to that question required ignoring decades-long secular trends in journalism. Legacy news organizations ranging from CNN to my hometown paper, The Boston Globe, have been jettisoning specialized science reporters since the late 1990s. As profits disappeared and newsroom budgets shrank, “in-depth” projects became rarer and rarer. This is hardly a surprise. Nuanced, investigative reports have always been the equivalent of newsroom money pits: They require (relatively) highly paid reporters and editors, they don’t produce a lot of copy relative to the amount of effort needed, and they don’t typically deal with subjects advertisers want to be associated with. (Can you think of any companies that’d be eager to pitch their wares alongside this excellent Times series on the abuse of developmentally disabled patients in New York State group homes? Me neither.)

Even the existence of the very small handful of outlets — namely Atavist and Byliner – that were successfully producing the type of work Matter aspired to create seemed to raise questions about Giles and Johnson’s project. Atavist, in particular, was already highlighting work by well-known science writers (including Deborah Blum and David Dobbs, fellow contributing editors at the online science ebook review Download the Universe) and had run some of the best science stories of the past year, including Jessica Benko’s “The Electric Mind” and Matt Power’s “Island of Secrets.” What hole, exactly, would Matter be filling?

***

My first direct contact with Matter came last summer, when Giles got in touch with me to discuss the project. By that point, the Matter Kickstarter campaign had exceeded its initial $50,000 goal by more than $100,000, and Giles and Johnson were well on their way to their planned fall launch. Despite my reservations, I was, for purely selfish reasons, rooting for the endeavor to be a success. (In addition to writing long-form pieces about science myself, I teach in MIT’s Graduate Program in Science Writing, a year-long master’s program that emphasizes long-form reportage.)

Then, in October, Jim asked me if I was interested in editing a piece. There were a lot of good reasons for me to decline: My family was in the middle of a difficult move; November is my busiest teaching month; there are a number of projects of my own that I’m woefully behind on. Still, I agreed to read the first draft of the piece Jim wanted me to work on, if only so it wouldn’t seem as if I was summarily saying no.

Bad move on my part: The piece, a wonderfully rich profile of Michael Levin, a Tufts professor using bioelectrical signals to prompt regeneration, was enthralling — and, as it happened, I’d recently met the writer, an award winning radio and print reporter named Cynthia Graber who’s spending the year at MIT on a Knight Fellowship. Levin’s tale was both fascinating and inspiring: He’s Russian-Jewish émigré whose single-minded obsession has led him to the brink of discovering one of medicine’s holy grails. Equally inspiring to a writer/journalist who sometimes wonders whether there’s an audience for the type of work I find most rewarding was that fact that Cynthia had hunted down this story and reported it to within an inch of its life — and she’d done it all without an assignment, or even any real prospects of one. She’d spent hours upon hours talking with Levin; she’d been in his lab and interviewed his colleagues and collaborators and students; she’d even researched centuries of history of bioelectricity — and then, when she was done, she wrote it all up and sent it, unsolicited, to Matter. If there was any way I could be a part of helping this work see the light of day, I was going to do it.

Michael Levin in his lab at Tufts. (Photo by Kathi Bahr)

“Electric Shock,” the result of Cynthia’s Herculean efforts, came out today. It’s available for 99 cents — and for that price, you get access to the gorgeous online version (which includes pictures by Kathi Bahr), an ebook that can be read on Kindles or iPads or your ereader of choice, and access to an exclusive Q&A with Cynthia. It’s a piece of work I’m honored and proud to be associated with.

It’s also the type of thing that makes me more optimistic about the future of my profession. There’s no question that the media is in the middle of a painful, difficult period. But “Electric Shock” underscores how seismic change does, in fact, bring new opportunities for those willing to look for them. Five or ten or twenty years ago, I’m not sure Cynthia would have ever written this piece in the first place — and if she had, I don’t know if it would have seen the light of day. There are tiny number of print publications that run stories that are more than 5,000 words long. Would any of them have been interested in a profile of a biologist who is happiest when he can read and think in peace at a South Florida resort that caters to the elderly? And if one of them had, would its editors have given a reporter who’d never written anything approaching that length the chance to show what she was capable of?

Maybe, in the end, Matter will prove to be a quixotic effort; maybe Jim and Bobbie really are tilting at the windmills of user-generated, bite-sized, easy-to-digest content. But after working on “Electric Shock,” I’m willing to do whatever I can to prove that my initial skepticism was wrong.

***

If you haven’t read it already, you should also check out Matter‘s first piece, a stunning exploration of people who amputate healthy limbs. It was written by New Scientist correspondent Anil Ananthaswamy and edited by former Harper’s and current Oxford American editor Roger Hodge.

December 10, 2012

We interrupt this extended absence: Tonight only, The Panic Virus at Skeptics in the Pub, Harvard Square

It’s been a lonely few months here at The Panic Virus. There are myriad reasons for that, none of which I’ll bother you all with now. But…I will be coming out of my hole tonight to talk to the Boston Skeptics as part of their Skeptics in the Pub series.

The details:

What: Boston Skeptics SitP series

When: December 10, 2012, 7pm

Where: Upstairs at Tommy Doyle’s, Harvard Square

Cost: Free; donations welcome

Other info: Here’s the event’s Facebook page. Twitter: @bostonskeptics and @sethmnookin.

The nominal topic tonight will be what the group refers to as the Vaxx Wars and “why people believe false and ultimate harmful ideas.” As always, I’m up for talking about anything the audience is interested in. So come on out, interested audience!

September 14, 2012

The state of science writing, circa 2012: The summer of our discontent, made glorious by the possibilities of our time

The summer has not been an easy one for aficionados or practitioners of science writing. There was, of course, the ongoing, death-by-1,000-cuts Jonah Lehrer fiasco, where, over a period of more than a month, one of the most popular and admired science writers working today was revealed to have promiscuously recycled his own work; was caught fabricating quotes by Bob Dylan; was fired from The New Yorker; and had his best-selling book withdrawn by his publisher. Before it was all over, the Lehrer mess had also sullied the reputation of Wired, one of the few popular magazines that runs long, narrative stories about science and technology, and Wired.com, which features a sterling lineup of science bloggers. (This wound was at least partially, and bewilderingly, self-inflicted.)

It would be folly to draw broad conclusions from the actions of one unscrupulous individual — but Jonah was far from the sole case of a journalist who writes about science misleading the public, either intentionally or (as hopefully is more often the case) not. On August 26, The New York Times‘s Sunday Review section ran a piece titled “An Immune Disorder at the Root of Autism” that (no joke) proposed hookworms as a potential cure for autism. (My comment at the time was that I wished the standard for publication in op-ed pages was “interesting and plausible” as opposed to just “interesting.”) Over at the tech blog Gizmodo, Jesus Diaz, whom I enjoy reading when he’s writing about gadgets, made me want to claw my eyes out with his series of goshtastic dispatches that heralded the imminent arrival of a cancer-free world where the eternally young spend their days pondering their artificial memories, which they’ll be able to do without having to breath – although they will still need to reckon with The Force. More recently, there’s been the spectacle of Naomi Wolf butchering logic and misrepresenting research while promoting her latest book, Vagina. On Tuesday, The Guardian gave her free rein to claim, in a column non-ironically given a “Knowledge is power” headline, that her critics were simply refusing to accept the ”latest neuroscientific and other findings” about female desire.

Even moments that should have been celebratory ended up leaving many of us who care about science, and science communication, grumpy and dispirited. Last week, the massive ENCODE project — that stands for Encyclopedia Of DNA Elements — published dozens of papers that stemmed from a years-long effort to unravel the mysteries of the human genome (The project included more than 1,600 experiments on 147 cell types. The main paper alone had almost 450 authors, who collectively represented more than 30 different institutions.) This was exciting, impressive work — but, as the name of the project itself implies, what was most striking about the ENCODE results were their encyclopedic nature and not any stand-out breakthroughs. Indeed, the realities that the ENCODE research provided evidence for — that it’s essential to examine genetic variation in a population when tackling disease; that variation isn’t uniform across the entire genome; that large swaths of our genome that don’t encode for proteins do serve other important functions — were all principles that were already pretty well understood.

But providing detailed evidence for things we (more or less) know are true is much less compelling than paradigm-shifting conclusions, which is presumably why the main ENCODE paper claimed that the team had been able to ”assign biochemical functions for 80% of the genome” (much of which had been known by the misleading shorthand, junk DNA). That talking point, which was repeated ad nauseam by many, if not most, of the outlets covering the ENCODE results, led John Timmer to post a piece in Ars Technica titled, “Most of what you read was wrong: how press releases rewrote scientific history.” “Unfortunately,” John wrote, “the significance of that statement hinged on a much less widely reported item: the definition of ‘biochemical function’ used by the authors.”

This was more than a matter of semantics. Many press reports that resulted painted an entirely fictitious history of biology’s past, along with a misleading picture of its present. As a result, the public that relied on those press reports now has a completely mistaken view of our current state of knowledge (this happens to be the exact opposite of what journalism is intended to accomplish). But you can’t entirely blame the press in this case. They were egged on by the journals and university press offices that promoted the work—and, in some cases, the scientists themselves.

Lest anyone think that the ENCODE case was sui generis, just this past Wednesday, a team of researchers based in France published a paper in PLOS ONE titled “Why Most Biomedical Findings Echoed by Newspapers Turn Out to be False: The Case of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.” (The paper’s authors were intentionally evoking the title of John P. A. Ioannidis’s groundbreaking 2005 piece, “Why most published research findings are false,” which built off of his earlier JAMA paper, “Contradicted and Initially Stronger Effects in Highly Cited Clinical Research.”) After examining every newspaper report about the ten most covered research papers on ADHD from the 1990s, the authors were able to provide empirical evidence for a troubling phenomenon that seems to be all but baked in to the way our scientific culture operates: We pay lots of attention to things that are almost assuredly not true.

That might sound crazy, but consider: Because it’s sexier to discover something than to show there’s nothing to be discovered, high-impact journals show a marked preference for “initial studies” as opposed to disconfirmations. Unfortunately, as anyone who has ever worked in a research lab knows, initial observations are almost inevitably refuted or heavily attenuated by future studies — and that data tends to get printed in less prestigious journals. Newspapers, meanwhile, give lots of attention to those first, eye-catching results while spilling very little (if any) ink on the ongoing research that shows why people shouldn’t have gotten all hot and bothered in the first place. (I have a high degree of confidence that the same phenomenon occurs regardless of the medium, but the PLOS ONE study only examined print newspapers.) The result? ”[A]n almost complete amnesia in the newspaper coverage of biomedical findings.”

So, to summarize: one of our biggest stars was revealed as a fraud; publications that should be exemplars of nuanced, high-quality reporting are allowing confused speculation to clutter their pages; researchers and PIOs are nudging reporters towards overblown interpretations; and everything we write about will probably end up being wrong anyway — not that we’ll bother to let you know when the time comes.

***

And yet, and yet. Yes, the Times‘s hookworm-as-possible-miracle-cure piece was upsetting — but it also led to the indefatigable and invaluable Emily Willingham, who is both a biologist and a longtime autism expert, doing a wonderful job unpacking that piece and analyzing the sources its author used. Yes, Naomi Wolf made a mockery of what neuroscience can (and can’t) tell us, but she also sparked this excellent David Dobbs post on the “perils of neuro self-help.” (Wolf, Dobbs wrote, is just the latest writer whose “shallow sips from [the] fresh founts” of neuroscience and evolutionary psychology “generate[d] an epiphanous but unjustified confidence.”)

And yes, the ENCODE coverage highlighted some of deep-rooted flaws in how we value and communicate about science – but the snarled, labyrinthine debate also highlighted the incredible opportunities available to anyone interesting in reading, or writing, about complex scientific issues. Genetics is a subject I know precious little about — and one I hope to write about in the future. Five years ago, it would have been difficult to know where to start. Today, I turned to Princeton genomics and evolutionary biology professor Leonid Kruglyak‘s Twitter stream. Among the many places that directed me was biochemist Mike White’s posts at the Finch and Pea and evolutionary biologist T. Ryan Gregory’s posts on ENCODE at his blog, Evolver Zone: Genomicron. Once I began pulling on those threads, they lead me to computational biologist Sean Eddy’s “ENCODE says what?” post at Cryptogenomicon, the 4,900-word, “My own thoughts” post that Ewan Birney, the lead scientist on the ENCODE project, put up simultaneous to the ENCODE papers’ publication, and Birney’s response to the reactions/backlash that ensued.

It wasn’t until I sat down to write this post that I realized that those are all documents written by people who are not only working scientists but also experts in the fields in question. When I began searching out work by science writers, I found subtle, sedulous pieces like Ed Yong’s “ENCODE: The rough guide to the human genome” and Brendan Maher’s “Fighting about ENCODE and junk.”

The end result of all of my reading was manifold: I now have a good grasp of the ENCODE project; I’m aware of some of the big issues facing genetics; I understand why the initial coverage proceeded the way it did, why that coverage was criticized, and how to avoid similar mistakes in my own work in the future; and I have learned of, and in some cases made contact with, a range of dynamic scientists dealing with these issues.

Oh, also: I’ve been reminded, once again, of why the process of learning about the mysteries of the world, and having the privilege of occasionally explaining what we know about those mysteries to total strangers, is so exhilarating and energizing and, dare I say, sometimes even ennobling.

Seth Mnookin's Blog

- Seth Mnookin's profile

- 39 followers