Freda Lightfoot's Blog, page 19

June 30, 2011

What do we know about sheep?

My journey as a writer continued. I now had sufficient confidence to try for the mainstream fiction market. Luckpenny Land was the first full length historical saga I ever wrote. We were still living on the small-holding, out on Shap Fell in Cumbria. And as I trekked up the fellside in the dark of a freezing night to check if our sheep were about to lamb, or to feed a pet lamb, I'd be thinking: 'There must be a book in this. But who would want to read about a middle-aged mum, with arthritis, being so stupid as to choose to live in a place where the pantry was colder than her wonderful Zanussi fridge, where the winter snows freeze the mains water supply in the field below the house every winter, as well as the battery in her car as it stands buried in snow in the yard.

My journey as a writer continued. I now had sufficient confidence to try for the mainstream fiction market. Luckpenny Land was the first full length historical saga I ever wrote. We were still living on the small-holding, out on Shap Fell in Cumbria. And as I trekked up the fellside in the dark of a freezing night to check if our sheep were about to lamb, or to feed a pet lamb, I'd be thinking: 'There must be a book in this. But who would want to read about a middle-aged mum, with arthritis, being so stupid as to choose to live in a place where the pantry was colder than her wonderful Zanussi fridge, where the winter snows freeze the mains water supply in the field below the house every winter, as well as the battery in her car as it stands buried in snow in the yard. So I used those wonderful two words that writers love: What if? What if I wrote about a girl who wanted to be a sheep farmer, it was World War II and her very Victorian father thought that it wasn't women's work. I could then use many of the amusing incidents and anecdotes my family had experienced living this life, but write it as fiction. Snag number one: running a smallholding with a few sheep and a couple of dozen hens didn't qualify me to write knowledgeably about running a proper sheep farm, let alone during WWII, so I would need to do considerable research.

I began by interviewing Cumbrian farmers, who are a breed apart. Stoic, strong, taciturn, and distrustful of strangers, particularly of people who have not lived in the Lake District for three generations. It's not that they are unfriendly, only that they're more used to the company of themselves and their animals rather than a nosy, would-be author. At this point in my career having published only short stories, articles, and 5 Mills and Boon historicals, the prospect of a full-length saga was daunting. And I'd never done an interview in my life.

When I rang the first name on my list, a farmer out in the Langdales, I spoke first to his wife to ask if he would see me. 'Happen', she said, which I took as a yes. To be on the safe side I took my husband with me as he was used to dealing with Lakeland farmers, and it worked like a charm. I asked the farmer a question, and he told David the answer. I was so nervous I didn't even dare to switch on the brand new tape recorder I'd taken with me, so I scribbled notes like mad, and then even more later. I didn't make that mistake again, but he was marvellous. He took me through his farming year, explained everything most carefully, and showed me pictures of his dogs. Not his family, his dogs. All the farmers I interviewed did that. It's a nonsense to say farmers don't care about their working dogs. Mr G's dog appeared in the book, much to his delight, although the accident the fictional dog suffered was far more dramatic to that of the real dog, even if it had the same outcome. And no, I can't say anymore without spoiling it.

Some of the farmers I spoke to were women. Although farming was a reserved occupation during the war, many men opted to join up and leave their wives to run the family farm. I learned from them how to kill and scald a pig, how to wring a chicken's neck and pluck it. (my hens all lived to a ripe old age) Plus all the various wangles they got up to during the war, such as dressing up a pig as a person in the car so they wouldn't be caught out selling one. Talking to these women inspired many plot incidents and ideas, many based on real life, including the most dramatic which takes place in Luckpenny Land. And I won't spoil it by telling you that either. Armed with the research, I started to weave a love story and plan the lives of my characters.

Some of the farmers I spoke to were women. Although farming was a reserved occupation during the war, many men opted to join up and leave their wives to run the family farm. I learned from them how to kill and scald a pig, how to wring a chicken's neck and pluck it. (my hens all lived to a ripe old age) Plus all the various wangles they got up to during the war, such as dressing up a pig as a person in the car so they wouldn't be caught out selling one. Talking to these women inspired many plot incidents and ideas, many based on real life, including the most dramatic which takes place in Luckpenny Land. And I won't spoil it by telling you that either. Armed with the research, I started to weave a love story and plan the lives of my characters.So how did I go about selling it? I met an agent at a weekend conference and told him all about my idea, and he asked to see it when it was finished. It took 9 months, just like a baby. Weeks later, I got The Call. There were offers from three publishers and I went with Hodder & Stoughton, now part of the Hatchette group. I loved writing this series of books, now available in ebook on Amazon, etc. Selling Luckpenny Land on a fantastic three book contract deal proved to me that persistence pays. I was on a high. What could go wrong? Well, everything, that's what. It's called Life.

Now available as an ebook. Buy it from Amazon.

Published on June 30, 2011 05:59

June 23, 2011

What do we know about sheep?

I now had sufficient confidence to try for the mainstream fiction market. Luckpenny Land was the first full length historical saga I ever wrote. We were still living on the small-holding, out on Shap Fell in Cumbria. And as I trekked up the fellside in the dark of a freezing night to check if our sheep were about to lamb, or to feed a pet lamb, I'd be thinking: 'There must be a book in this. But who would want to read about a middle-aged mum, with arthritis, being so stupid as to choose to live in a place where the pantry was colder than her wonderful Zanussi fridge, where the winter snows freeze the mains water supply in the field below the house every winter, as well as the battery in her car as it stands buried in snow in the yard.

I now had sufficient confidence to try for the mainstream fiction market. Luckpenny Land was the first full length historical saga I ever wrote. We were still living on the small-holding, out on Shap Fell in Cumbria. And as I trekked up the fellside in the dark of a freezing night to check if our sheep were about to lamb, or to feed a pet lamb, I'd be thinking: 'There must be a book in this. But who would want to read about a middle-aged mum, with arthritis, being so stupid as to choose to live in a place where the pantry was colder than her wonderful Zanussi fridge, where the winter snows freeze the mains water supply in the field below the house every winter, as well as the battery in her car as it stands buried in snow in the yard. So I used those wonderful two words that writers love: What if? What if I wrote about a girl who wanted to be a sheep farmer, it was World War II and her very Victorian father thought that it wasn't women's work. I could then use many of the amusing incidents and anecdotes my family had experienced living this life, but write it as fiction. Snag number one: running a smallholding with a few sheep and a couple of dozen hens didn't qualify me to write knowledgeably about running a proper sheep farm, let alone during WWII, so I would need to do considerable research.

I began by interviewing Cumbrian farmers, who are a breed apart. Stoic, strong, taciturn, and distrustful of strangers, particularly of people who have not lived in the Lake District for three generations. It's not that they are unfriendly, only that they're more used to the company of themselves and their animals rather than a nosy, would-be author. At this point in my career having published only short stories, articles, and 5 Mills and Boon historicals, the prospect of a full-length saga was daunting. And I'd never done an interview in my life.

When I rang the first name on my list, a farmer out in the Langdales, I spoke first to his wife to ask if he would see me. 'Happen', she said, which I took as a yes. To be on the safe side I took my husband with me as he was used to dealing with Lakeland farmers, and it worked like a charm. I asked the farmer a question, and he told David the answer. I was so nervous I didn't even dare to switch on the brand new tape recorder I'd taken with me, so I scribbled notes like mad, and then even more later. I didn't make that mistake again, but he was marvellous. He took me through his farming year, explained everything most carefully, and showed me pictures of his dogs. Not his family, his dogs. All the farmers I interviewed did that. It's a nonsense to say farmers don't care about their working dogs. Mr G's dog appeared in the book, much to his delight, although the accident the fictional dog suffered was far more dramatic to that of the real dog, even if it had the same outcome. And no, I can't say anymore without spoiling it.

Some of the farmers I spoke to were women. Although farming was a reserved occupation during the war, many men opted to join up and leave their wives to run the family farm. I learned from them how to kill and scald a pig, how to wring a chicken's neck and pluck it. (my hens all lived to a ripe old age) Plus all the various wangles they got up to during the war, such as dressing up a pig as a person in the car so they wouldn't be caught out selling one. Talking to these women inspired many plot incidents and ideas, many based on real life, including the most dramatic which takes place in Luckpenny Land. And I won't spoil it by telling you that either. Armed with the research, I started to weave a love story and plan the lives of my characters.

Some of the farmers I spoke to were women. Although farming was a reserved occupation during the war, many men opted to join up and leave their wives to run the family farm. I learned from them how to kill and scald a pig, how to wring a chicken's neck and pluck it. (my hens all lived to a ripe old age) Plus all the various wangles they got up to during the war, such as dressing up a pig as a person in the car so they wouldn't be caught out selling one. Talking to these women inspired many plot incidents and ideas, many based on real life, including the most dramatic which takes place in Luckpenny Land. And I won't spoil it by telling you that either. Armed with the research, I started to weave a love story and plan the lives of my characters.So how did I go about selling it? I met an agent at a weekend conference and told him all about my idea, and he asked to see it when it was finished. It took 9 months, just like a baby. Weeks later, I got The Call. There were offers from three publishers and I went with Hodder & Stoughton, now part of the Hatchette group. I loved writing this series of books, now available in ebook on Amazon, etc. Selling Luckpenny Land on a fantastic three book contract deal proved to me that persistence pays. I was on a high. What could go wrong? Well, everything, that's what. It's called Life.

Now available as an ebook. Buy it from Amazon.

Published on June 23, 2011 09:28

June 10, 2011

An Ill Wind

I was happily running my book shop but began to suffer from debilitating headaches which were laying me low for two or three days each week. Diagnosed as 'stress' I was forced to sell the business and we decided that it would be a good idea to buy a cottage in the country. My husband was by this time well established in his small town solicitor's practice, so I could take some time off and just be a mum. The 'Good Life' was on TV at the time, a comedy about a young couple trying out self-sufficiency, which seemed like a good idea. We bought a half derelict house high on the fells in the Lake District, together with one hectare of land, and doing it up would be a great stress-buster, then I'd write The novel.

However, when the snows came that first Christmas, the truth of my problems finally became clear. I had cervical spondylitis, a form of osteo-arthritis. Since I'd convinced myself that I had a brain tumour, this was great news. However, for several months I was overwhelmed by pain but then, slowly, I began to improve and while doing so, made an amazing discovery. Writing is the best therapy of all. It takes you out of yourself, above pain; a fact which remains true for me to this day. With the help of an electronic typewriter, (still no computer) and propped up by cushions, I was able to type despite a neck collar and one arm in a sling. I must have looked hilarious.

However, when the snows came that first Christmas, the truth of my problems finally became clear. I had cervical spondylitis, a form of osteo-arthritis. Since I'd convinced myself that I had a brain tumour, this was great news. However, for several months I was overwhelmed by pain but then, slowly, I began to improve and while doing so, made an amazing discovery. Writing is the best therapy of all. It takes you out of yourself, above pain; a fact which remains true for me to this day. With the help of an electronic typewriter, (still no computer) and propped up by cushions, I was able to type despite a neck collar and one arm in a sling. I must have looked hilarious.

Osteo-arthritis is a condition, not an illness, and a strange one at that. I worked on my yoga, ate what I thought was the right food, took my fish oil tablets and various homeopathic remedies, although I couldn't say which worked best, gradually I got better. I learned to 'read' my body, to know when it needed to rest, when to move and be active. On good days when I felt marvellous, euphoric even when the pain had subsided, I would feed my hens, look after our few sheep and their lambs, grow fruit and vegetables. I even planted a small wood and learned how to make jam. All great material for amusing articles, which I wrote on the wet days when confined to the house, of which there were plenty. The first success was a Cackle of Hens, which was how not to do it. Write about what you know, they say. I wrote about what I didn't know about running a small-holding, ably assisted by my animal friends.

Osteo-arthritis is a condition, not an illness, and a strange one at that. I worked on my yoga, ate what I thought was the right food, took my fish oil tablets and various homeopathic remedies, although I couldn't say which worked best, gradually I got better. I learned to 'read' my body, to know when it needed to rest, when to move and be active. On good days when I felt marvellous, euphoric even when the pain had subsided, I would feed my hens, look after our few sheep and their lambs, grow fruit and vegetables. I even planted a small wood and learned how to make jam. All great material for amusing articles, which I wrote on the wet days when confined to the house, of which there were plenty. The first success was a Cackle of Hens, which was how not to do it. Write about what you know, they say. I wrote about what I didn't know about running a small-holding, ably assisted by my animal friends.

With my family at work and school, I wrote short stories, serials, a children's novel, picture scripts, a couple of Mills & Boon contemporaries, and articles galore. The aim was to send them out faster than they were coming back. Unfortunately, my scatter-gun approach didn't work very well, as most came winging back. Selling short articles was one thing, but I still hadn't cracked fiction. Postman Pat would bring what he thought to be exciting stuff for me each day in his little red van, but were really big fat rejection parcels. I started taking courses, read everything I could about the art of writing, learned about market study.

With my family at work and school, I wrote short stories, serials, a children's novel, picture scripts, a couple of Mills & Boon contemporaries, and articles galore. The aim was to send them out faster than they were coming back. Unfortunately, my scatter-gun approach didn't work very well, as most came winging back. Selling short articles was one thing, but I still hadn't cracked fiction. Postman Pat would bring what he thought to be exciting stuff for me each day in his little red van, but were really big fat rejection parcels. I started taking courses, read everything I could about the art of writing, learned about market study.

I finally sold my first short story to D.C.Thompson. What a red letter day that was, also the name of the magazine, now defunct. Following this breakthrough I seemed to have discovered the knack, or I'd learned to target my markets more affectively, and I went on to sell several more short stories to My Weekly and People's Friend, also several true confessions for My Story magazine.

I finally sold my first short story to D.C.Thompson. What a red letter day that was, also the name of the magazine, now defunct. Following this breakthrough I seemed to have discovered the knack, or I'd learned to target my markets more affectively, and I went on to sell several more short stories to My Weekly and People's Friend, also several true confessions for My Story magazine.

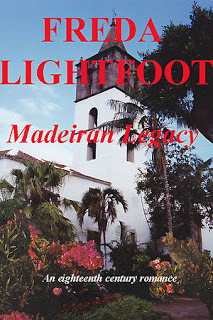

Best of all I'd regained my confidence. I'd realised that you don't have to be a genius to be published. I tried again for Mills & Boon, this time with a historical. Two more rejections came, both with sufficient editorial help to encourage me to keep trying. They accepted the third, Madeiran Legacy. (Now available on Amazon as an ebook) I was jubilant. With my first advance I bought a computer and went on to sell them four more of these.

I'd served a long apprenticeship but during it I'd learned how to build strongly motivated characters, how to structure a story, put emotion on the page and make every word count. But then my romances began to get longer, and more complex, and I knew it was time to move on. I tried my hand at a saga, but that didn't prove to be as easy as I'd expected either.

However, when the snows came that first Christmas, the truth of my problems finally became clear. I had cervical spondylitis, a form of osteo-arthritis. Since I'd convinced myself that I had a brain tumour, this was great news. However, for several months I was overwhelmed by pain but then, slowly, I began to improve and while doing so, made an amazing discovery. Writing is the best therapy of all. It takes you out of yourself, above pain; a fact which remains true for me to this day. With the help of an electronic typewriter, (still no computer) and propped up by cushions, I was able to type despite a neck collar and one arm in a sling. I must have looked hilarious.

However, when the snows came that first Christmas, the truth of my problems finally became clear. I had cervical spondylitis, a form of osteo-arthritis. Since I'd convinced myself that I had a brain tumour, this was great news. However, for several months I was overwhelmed by pain but then, slowly, I began to improve and while doing so, made an amazing discovery. Writing is the best therapy of all. It takes you out of yourself, above pain; a fact which remains true for me to this day. With the help of an electronic typewriter, (still no computer) and propped up by cushions, I was able to type despite a neck collar and one arm in a sling. I must have looked hilarious. Osteo-arthritis is a condition, not an illness, and a strange one at that. I worked on my yoga, ate what I thought was the right food, took my fish oil tablets and various homeopathic remedies, although I couldn't say which worked best, gradually I got better. I learned to 'read' my body, to know when it needed to rest, when to move and be active. On good days when I felt marvellous, euphoric even when the pain had subsided, I would feed my hens, look after our few sheep and their lambs, grow fruit and vegetables. I even planted a small wood and learned how to make jam. All great material for amusing articles, which I wrote on the wet days when confined to the house, of which there were plenty. The first success was a Cackle of Hens, which was how not to do it. Write about what you know, they say. I wrote about what I didn't know about running a small-holding, ably assisted by my animal friends.

Osteo-arthritis is a condition, not an illness, and a strange one at that. I worked on my yoga, ate what I thought was the right food, took my fish oil tablets and various homeopathic remedies, although I couldn't say which worked best, gradually I got better. I learned to 'read' my body, to know when it needed to rest, when to move and be active. On good days when I felt marvellous, euphoric even when the pain had subsided, I would feed my hens, look after our few sheep and their lambs, grow fruit and vegetables. I even planted a small wood and learned how to make jam. All great material for amusing articles, which I wrote on the wet days when confined to the house, of which there were plenty. The first success was a Cackle of Hens, which was how not to do it. Write about what you know, they say. I wrote about what I didn't know about running a small-holding, ably assisted by my animal friends. With my family at work and school, I wrote short stories, serials, a children's novel, picture scripts, a couple of Mills & Boon contemporaries, and articles galore. The aim was to send them out faster than they were coming back. Unfortunately, my scatter-gun approach didn't work very well, as most came winging back. Selling short articles was one thing, but I still hadn't cracked fiction. Postman Pat would bring what he thought to be exciting stuff for me each day in his little red van, but were really big fat rejection parcels. I started taking courses, read everything I could about the art of writing, learned about market study.

With my family at work and school, I wrote short stories, serials, a children's novel, picture scripts, a couple of Mills & Boon contemporaries, and articles galore. The aim was to send them out faster than they were coming back. Unfortunately, my scatter-gun approach didn't work very well, as most came winging back. Selling short articles was one thing, but I still hadn't cracked fiction. Postman Pat would bring what he thought to be exciting stuff for me each day in his little red van, but were really big fat rejection parcels. I started taking courses, read everything I could about the art of writing, learned about market study. I finally sold my first short story to D.C.Thompson. What a red letter day that was, also the name of the magazine, now defunct. Following this breakthrough I seemed to have discovered the knack, or I'd learned to target my markets more affectively, and I went on to sell several more short stories to My Weekly and People's Friend, also several true confessions for My Story magazine.

I finally sold my first short story to D.C.Thompson. What a red letter day that was, also the name of the magazine, now defunct. Following this breakthrough I seemed to have discovered the knack, or I'd learned to target my markets more affectively, and I went on to sell several more short stories to My Weekly and People's Friend, also several true confessions for My Story magazine.Best of all I'd regained my confidence. I'd realised that you don't have to be a genius to be published. I tried again for Mills & Boon, this time with a historical. Two more rejections came, both with sufficient editorial help to encourage me to keep trying. They accepted the third, Madeiran Legacy. (Now available on Amazon as an ebook) I was jubilant. With my first advance I bought a computer and went on to sell them four more of these.

I'd served a long apprenticeship but during it I'd learned how to build strongly motivated characters, how to structure a story, put emotion on the page and make every word count. But then my romances began to get longer, and more complex, and I knew it was time to move on. I tried my hand at a saga, but that didn't prove to be as easy as I'd expected either.

Published on June 10, 2011 00:00

An Ill Wind

I was happily running my book shop but began to suffer from debilitating headaches which were laying me low for two or three days each week. Diagnosed as 'stress' I was forced to sell the business and we decided that it would be a good idea to buy a cottage in the country. My husband was by this time well established in his small town solicitor's practice, so I could take some time off and just be a mum. The 'Good Life' was on TV at the time, a comedy about a young couple trying out self-sufficiency, which seemed like a good idea. We bought a half derelict house high on the fells in the Lake District, together with one hectare of land, and doing it up would be a great stress-buster, then I'd write The novel.

However, when the snows came that first Christmas, the truth of my problems finally became clear. I had cervical spondylitis, a form of osteo-arthritis. Since I'd convinced myself that I had a brain tumour, this was great news. However, for several months I was overwhelmed by pain but then, slowly, I began to improve and while doing so, made an amazing discovery. Writing is the best therapy of all. It takes you out of yourself, above pain; a fact which remains true for me to this day. With the help of an electronic typewriter, (still no computer) and propped up by cushions, I was able to type despite a neck collar and one arm in a sling. I must have looked hilarious.

However, when the snows came that first Christmas, the truth of my problems finally became clear. I had cervical spondylitis, a form of osteo-arthritis. Since I'd convinced myself that I had a brain tumour, this was great news. However, for several months I was overwhelmed by pain but then, slowly, I began to improve and while doing so, made an amazing discovery. Writing is the best therapy of all. It takes you out of yourself, above pain; a fact which remains true for me to this day. With the help of an electronic typewriter, (still no computer) and propped up by cushions, I was able to type despite a neck collar and one arm in a sling. I must have looked hilarious.

Osteo-arthritis is a condition, not an illness, and a strange one at that. I worked on my yoga, ate what I thought was the right food, took my fish oil tablets and various homeopathic remedies, although I couldn't say which worked best, gradually I got better. I learned to 'read' my body, to know when it needed to rest, when to move and be active. On good days when I felt marvellous, euphoric even when the pain had subsided, I would feed my hens, look after our few sheep and their lambs, grow fruit and vegetables. I even planted a small wood and learned how to make jam. All great material for amusing articles, which I wrote on the wet days when confined to the house, of which there were plenty. The first success was a Cackle of Hens, which was how not to do it. Write about what you know, they say. I wrote about what I didn't know about running a small-holding, ably assisted by my animal friends.

Osteo-arthritis is a condition, not an illness, and a strange one at that. I worked on my yoga, ate what I thought was the right food, took my fish oil tablets and various homeopathic remedies, although I couldn't say which worked best, gradually I got better. I learned to 'read' my body, to know when it needed to rest, when to move and be active. On good days when I felt marvellous, euphoric even when the pain had subsided, I would feed my hens, look after our few sheep and their lambs, grow fruit and vegetables. I even planted a small wood and learned how to make jam. All great material for amusing articles, which I wrote on the wet days when confined to the house, of which there were plenty. The first success was a Cackle of Hens, which was how not to do it. Write about what you know, they say. I wrote about what I didn't know about running a small-holding, ably assisted by my animal friends.

With my family at work and school, I wrote short stories, serials, a children's novel, picture scripts, a couple of Mills & Boon contemporaries, and articles galore. The aim was to send them out faster than they were coming back. Unfortunately, my scatter-gun approach didn't work very well, as most came winging back. Selling short articles was one thing, but I still hadn't cracked fiction. Postman Pat would bring what he thought to be exciting stuff for me each day in his little red van, but were really big fat rejection parcels. I started taking courses, read everything I could about the art of writing, learned about market study.

With my family at work and school, I wrote short stories, serials, a children's novel, picture scripts, a couple of Mills & Boon contemporaries, and articles galore. The aim was to send them out faster than they were coming back. Unfortunately, my scatter-gun approach didn't work very well, as most came winging back. Selling short articles was one thing, but I still hadn't cracked fiction. Postman Pat would bring what he thought to be exciting stuff for me each day in his little red van, but were really big fat rejection parcels. I started taking courses, read everything I could about the art of writing, learned about market study.

I finally sold my first short story to D.C.Thompson. What a red letter day that was, also the name of the magazine, now defunct. Following this breakthrough I seemed to have discovered the knack, or I'd learned to target my markets more affectively, and I went on to sell several more short stories to My Weekly and People's Friend, also several true confessions for My Story magazine.

I finally sold my first short story to D.C.Thompson. What a red letter day that was, also the name of the magazine, now defunct. Following this breakthrough I seemed to have discovered the knack, or I'd learned to target my markets more affectively, and I went on to sell several more short stories to My Weekly and People's Friend, also several true confessions for My Story magazine.

Best of all I'd regained my confidence. I'd realised that you don't have to be a genius to be published. I tried again for Mills & Boon, this time with a historical. Two more rejections came, both with sufficient editorial help to encourage me to keep trying. They accepted the third, Madeiran Legacy. (Now available on Amazon as an ebook) I was jubilant. With my first advance I bought a computer and went on to sell them four more of these.

I'd served a long apprenticeship but during it I'd learned how to build strongly motivated characters, how to structure a story, put emotion on the page and make every word count. But then my romances began to get longer, and more complex, and I knew it was time to move on. I tried my hand at a saga, but that didn't prove to be as easy as I'd expected either.

However, when the snows came that first Christmas, the truth of my problems finally became clear. I had cervical spondylitis, a form of osteo-arthritis. Since I'd convinced myself that I had a brain tumour, this was great news. However, for several months I was overwhelmed by pain but then, slowly, I began to improve and while doing so, made an amazing discovery. Writing is the best therapy of all. It takes you out of yourself, above pain; a fact which remains true for me to this day. With the help of an electronic typewriter, (still no computer) and propped up by cushions, I was able to type despite a neck collar and one arm in a sling. I must have looked hilarious.

However, when the snows came that first Christmas, the truth of my problems finally became clear. I had cervical spondylitis, a form of osteo-arthritis. Since I'd convinced myself that I had a brain tumour, this was great news. However, for several months I was overwhelmed by pain but then, slowly, I began to improve and while doing so, made an amazing discovery. Writing is the best therapy of all. It takes you out of yourself, above pain; a fact which remains true for me to this day. With the help of an electronic typewriter, (still no computer) and propped up by cushions, I was able to type despite a neck collar and one arm in a sling. I must have looked hilarious. Osteo-arthritis is a condition, not an illness, and a strange one at that. I worked on my yoga, ate what I thought was the right food, took my fish oil tablets and various homeopathic remedies, although I couldn't say which worked best, gradually I got better. I learned to 'read' my body, to know when it needed to rest, when to move and be active. On good days when I felt marvellous, euphoric even when the pain had subsided, I would feed my hens, look after our few sheep and their lambs, grow fruit and vegetables. I even planted a small wood and learned how to make jam. All great material for amusing articles, which I wrote on the wet days when confined to the house, of which there were plenty. The first success was a Cackle of Hens, which was how not to do it. Write about what you know, they say. I wrote about what I didn't know about running a small-holding, ably assisted by my animal friends.

Osteo-arthritis is a condition, not an illness, and a strange one at that. I worked on my yoga, ate what I thought was the right food, took my fish oil tablets and various homeopathic remedies, although I couldn't say which worked best, gradually I got better. I learned to 'read' my body, to know when it needed to rest, when to move and be active. On good days when I felt marvellous, euphoric even when the pain had subsided, I would feed my hens, look after our few sheep and their lambs, grow fruit and vegetables. I even planted a small wood and learned how to make jam. All great material for amusing articles, which I wrote on the wet days when confined to the house, of which there were plenty. The first success was a Cackle of Hens, which was how not to do it. Write about what you know, they say. I wrote about what I didn't know about running a small-holding, ably assisted by my animal friends. With my family at work and school, I wrote short stories, serials, a children's novel, picture scripts, a couple of Mills & Boon contemporaries, and articles galore. The aim was to send them out faster than they were coming back. Unfortunately, my scatter-gun approach didn't work very well, as most came winging back. Selling short articles was one thing, but I still hadn't cracked fiction. Postman Pat would bring what he thought to be exciting stuff for me each day in his little red van, but were really big fat rejection parcels. I started taking courses, read everything I could about the art of writing, learned about market study.

With my family at work and school, I wrote short stories, serials, a children's novel, picture scripts, a couple of Mills & Boon contemporaries, and articles galore. The aim was to send them out faster than they were coming back. Unfortunately, my scatter-gun approach didn't work very well, as most came winging back. Selling short articles was one thing, but I still hadn't cracked fiction. Postman Pat would bring what he thought to be exciting stuff for me each day in his little red van, but were really big fat rejection parcels. I started taking courses, read everything I could about the art of writing, learned about market study. I finally sold my first short story to D.C.Thompson. What a red letter day that was, also the name of the magazine, now defunct. Following this breakthrough I seemed to have discovered the knack, or I'd learned to target my markets more affectively, and I went on to sell several more short stories to My Weekly and People's Friend, also several true confessions for My Story magazine.

I finally sold my first short story to D.C.Thompson. What a red letter day that was, also the name of the magazine, now defunct. Following this breakthrough I seemed to have discovered the knack, or I'd learned to target my markets more affectively, and I went on to sell several more short stories to My Weekly and People's Friend, also several true confessions for My Story magazine.Best of all I'd regained my confidence. I'd realised that you don't have to be a genius to be published. I tried again for Mills & Boon, this time with a historical. Two more rejections came, both with sufficient editorial help to encourage me to keep trying. They accepted the third, Madeiran Legacy. (Now available on Amazon as an ebook) I was jubilant. With my first advance I bought a computer and went on to sell them four more of these.

I'd served a long apprenticeship but during it I'd learned how to build strongly motivated characters, how to structure a story, put emotion on the page and make every word count. But then my romances began to get longer, and more complex, and I knew it was time to move on. I tried my hand at a saga, but that didn't prove to be as easy as I'd expected either.

Published on June 10, 2011 00:00

June 3, 2011

Is Running a Book Shop good for a writer?

Running a book shop must be every writer's dream, or at least to be let loose in one to freely enjoy its spoils. It was certainly one of mine. Sitting behind the counter reading the latest hot sellers, or re-reading all those favourite Georgette Heyer and Jean Plaidy novels was surely an essential part of any bookseller's life, wasn't it, if I was to successfully advise customers? I could run my shop, mind my children, and work on my novel in between customers. Of such stuff are dreams made.

It didn't quite work out that way. It was true that at the end of a busy day, in the wee small hours, I could still be found scribbling away, although rarely did I send anything out. Something was happening to me. But something wasn't quite right. This was the moment I was going to discover the secret of all these famous authors and emulate them so that I could turn into one myself. I gobbled up such delights as Scruples, Hollywood Wives, Lace, The Thorn Birds, Love Story, Jonathan Livingston Seagull, The French Lieutenant's Woman. I was like a food addict let loose in a chocolate shop.

These authors were sending out a powerful message. They had brilliant, original ideas, a way with words which proved their skill with prose, their characters lived on in my mind, the stories were compulsive, the settings fabulous and far removed from anything I could relate to in my humble life. How could I ever dream up anything half so good? Why would anyone wish to read anything I wrote? I was intimidated by their greatness, and terrified of copying these masters.

I put my pen away.

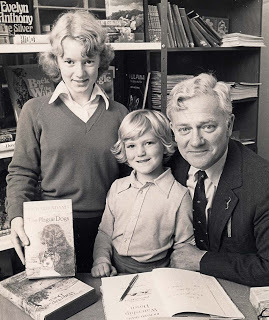

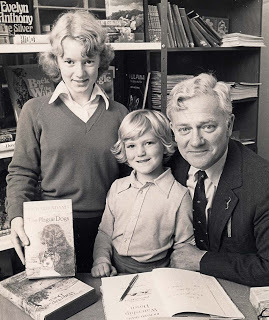

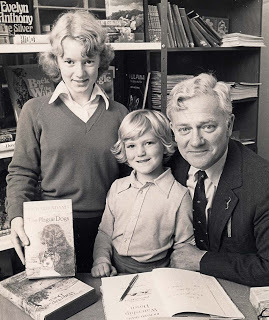

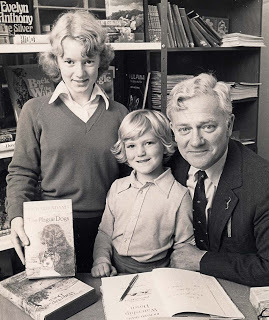

Ten years were to go by in this way. The children, and the book shop, grew surprisingly well. We had Richard Adams (Watership Down) come to our small shop in the English Lake District for a signing of Plague Dogs, and sold well over 100 copies. We became school and library suppliers, I gave talks, ran book clubs, and soon became absorbed in reading masses of book catalogues instead of bestsellers, and each night painstakingly wrote out the orders by hand in those pre-computer days. Not to mention unpacking, checking, making up the orders and getting them delivered on time. Those magical days of reading behind the counter were now a nostalgic memory.

Ten years were to go by in this way. The children, and the book shop, grew surprisingly well. We had Richard Adams (Watership Down) come to our small shop in the English Lake District for a signing of Plague Dogs, and sold well over 100 copies. We became school and library suppliers, I gave talks, ran book clubs, and soon became absorbed in reading masses of book catalogues instead of bestsellers, and each night painstakingly wrote out the orders by hand in those pre-computer days. Not to mention unpacking, checking, making up the orders and getting them delivered on time. Those magical days of reading behind the counter were now a nostalgic memory.

As was any writing of my own.

Most of all I helped customers to find just the book they wanted to read, by an author they couldn't remember but the book had a girl and a child on the jacket. they wanted the War and Peace that was on the telly and not that big thick Penguin edition; and whatever that story was that had been read on Radio Four the other afternoon. It was fun, it was challenging, it taught me a great deal about the publishing industry, about books and people, but left me no time to write. Not that it mattered any more, as my confidence had entirely drained away, and I knew in my heart that I could never join these luminaries that graced our shelves. Maybe I'd get back to that when I was a better writer. Sadly, it didn't cross my mind that I never would achieve that blissful state if I didn't practise my craft.

It wasn't until after I'd sold the buisness that I began to take my writing seriously, and yes, I did find that having spent those years in the book trade did help me in many ways. I was aware of what book buyers were looking for, what was commercial, how genres worked, but the craft of turning out a good story cannot be learnt. You can either do that or you can't. So how did I get started? How did I find the confidence? Well, it was an ill wind that blew me some good. I'll tell you more about that next time.

It didn't quite work out that way. It was true that at the end of a busy day, in the wee small hours, I could still be found scribbling away, although rarely did I send anything out. Something was happening to me. But something wasn't quite right. This was the moment I was going to discover the secret of all these famous authors and emulate them so that I could turn into one myself. I gobbled up such delights as Scruples, Hollywood Wives, Lace, The Thorn Birds, Love Story, Jonathan Livingston Seagull, The French Lieutenant's Woman. I was like a food addict let loose in a chocolate shop.

These authors were sending out a powerful message. They had brilliant, original ideas, a way with words which proved their skill with prose, their characters lived on in my mind, the stories were compulsive, the settings fabulous and far removed from anything I could relate to in my humble life. How could I ever dream up anything half so good? Why would anyone wish to read anything I wrote? I was intimidated by their greatness, and terrified of copying these masters.

I put my pen away.

Ten years were to go by in this way. The children, and the book shop, grew surprisingly well. We had Richard Adams (Watership Down) come to our small shop in the English Lake District for a signing of Plague Dogs, and sold well over 100 copies. We became school and library suppliers, I gave talks, ran book clubs, and soon became absorbed in reading masses of book catalogues instead of bestsellers, and each night painstakingly wrote out the orders by hand in those pre-computer days. Not to mention unpacking, checking, making up the orders and getting them delivered on time. Those magical days of reading behind the counter were now a nostalgic memory.

Ten years were to go by in this way. The children, and the book shop, grew surprisingly well. We had Richard Adams (Watership Down) come to our small shop in the English Lake District for a signing of Plague Dogs, and sold well over 100 copies. We became school and library suppliers, I gave talks, ran book clubs, and soon became absorbed in reading masses of book catalogues instead of bestsellers, and each night painstakingly wrote out the orders by hand in those pre-computer days. Not to mention unpacking, checking, making up the orders and getting them delivered on time. Those magical days of reading behind the counter were now a nostalgic memory.As was any writing of my own.

Most of all I helped customers to find just the book they wanted to read, by an author they couldn't remember but the book had a girl and a child on the jacket. they wanted the War and Peace that was on the telly and not that big thick Penguin edition; and whatever that story was that had been read on Radio Four the other afternoon. It was fun, it was challenging, it taught me a great deal about the publishing industry, about books and people, but left me no time to write. Not that it mattered any more, as my confidence had entirely drained away, and I knew in my heart that I could never join these luminaries that graced our shelves. Maybe I'd get back to that when I was a better writer. Sadly, it didn't cross my mind that I never would achieve that blissful state if I didn't practise my craft.

It wasn't until after I'd sold the buisness that I began to take my writing seriously, and yes, I did find that having spent those years in the book trade did help me in many ways. I was aware of what book buyers were looking for, what was commercial, how genres worked, but the craft of turning out a good story cannot be learnt. You can either do that or you can't. So how did I get started? How did I find the confidence? Well, it was an ill wind that blew me some good. I'll tell you more about that next time.

Published on June 03, 2011 00:00

Is Running a Book Shop good for a writer?

Running a book shop must be every writer's dream, or at least to be let loose in one to freely enjoy its spoils. It was certainly one of mine. Sitting behind the counter reading the latest hot sellers, or re-reading all those favourite Georgette Heyer and Jean Plaidy novels was surely an essential part of any bookseller's life, wasn't it, if I was to successfully advise customers? I could run my shop, mind my children, and work on my novel in between customers. Of such stuff are dreams made.

It didn't quite work out that way. It was true that at the end of a busy day, in the wee small hours, I could still be found scribbling away, although rarely did I send anything out. Something was happening to me. But something wasn't quite right. This was the moment I was going to discover the secret of all these famous authors and emulate them so that I could turn into one myself. I gobbled up such delights as Scruples, Hollywood Wives, Lace, The Thorn Birds, Love Story, Jonathan Livingston Seagull, The French Lieutenant's Woman. I was like a food addict let loose in a chocolate shop.

These authors were sending out a powerful message. They had brilliant, original ideas, a way with words which proved their skill with prose, their characters lived on in my mind, the stories were compulsive, the settings fabulous and far removed from anything I could relate to in my humble life. How could I ever dream up anything half so good? Why would anyone wish to read anything I wrote? I was intimidated by their greatness, and terrified of copying these masters.

I put my pen away.

Ten years were to go by in this way. The children, and the book shop, grew surprisingly well. We had Richard Adams (Watership Down) come to our small shop in the English Lake District for a signing of Plague Dogs, and sold well over 100 copies. We became school and library suppliers, I gave talks, ran book clubs, and soon became absorbed in reading masses of book catalogues instead of bestsellers, and each night painstakingly wrote out the orders by hand in those pre-computer days. Not to mention unpacking, checking, making up the orders and getting them delivered on time. Those magical days of reading behind the counter were now a nostalgic memory.

Ten years were to go by in this way. The children, and the book shop, grew surprisingly well. We had Richard Adams (Watership Down) come to our small shop in the English Lake District for a signing of Plague Dogs, and sold well over 100 copies. We became school and library suppliers, I gave talks, ran book clubs, and soon became absorbed in reading masses of book catalogues instead of bestsellers, and each night painstakingly wrote out the orders by hand in those pre-computer days. Not to mention unpacking, checking, making up the orders and getting them delivered on time. Those magical days of reading behind the counter were now a nostalgic memory.

As was any writing of my own.

Most of all I helped customers to find just the book they wanted to read, by an author they couldn't remember but the book had a girl and a child on the jacket. they wanted the War and Peace that was on the telly and not that big thick Penguin edition; and whatever that story was that had been read on Radio Four the other afternoon. It was fun, it was challenging, it taught me a great deal about the publishing industry, about books and people, but left me no time to write. Not that it mattered any more, as my confidence had entirely drained away, and I knew in my heart that I could never join these luminaries that graced our shelves. Maybe I'd get back to that when I was a better writer. Sadly, it didn't cross my mind that I never would achieve that blissful state if I didn't practise my craft.

It wasn't until after I'd sold the buisness that I began to take my writing seriously, and yes, I did find that having spent those years in the book trade did help me in many ways. I was aware of what book buyers were looking for, what was commercial, how genres worked, but the craft of turning out a good story cannot be learnt. You can either do that or you can't. So how did I get started? How did I find the confidence? Well, it was an ill wind that blew me some good. I'll tell you more about that next time.

It didn't quite work out that way. It was true that at the end of a busy day, in the wee small hours, I could still be found scribbling away, although rarely did I send anything out. Something was happening to me. But something wasn't quite right. This was the moment I was going to discover the secret of all these famous authors and emulate them so that I could turn into one myself. I gobbled up such delights as Scruples, Hollywood Wives, Lace, The Thorn Birds, Love Story, Jonathan Livingston Seagull, The French Lieutenant's Woman. I was like a food addict let loose in a chocolate shop.

These authors were sending out a powerful message. They had brilliant, original ideas, a way with words which proved their skill with prose, their characters lived on in my mind, the stories were compulsive, the settings fabulous and far removed from anything I could relate to in my humble life. How could I ever dream up anything half so good? Why would anyone wish to read anything I wrote? I was intimidated by their greatness, and terrified of copying these masters.

I put my pen away.

Ten years were to go by in this way. The children, and the book shop, grew surprisingly well. We had Richard Adams (Watership Down) come to our small shop in the English Lake District for a signing of Plague Dogs, and sold well over 100 copies. We became school and library suppliers, I gave talks, ran book clubs, and soon became absorbed in reading masses of book catalogues instead of bestsellers, and each night painstakingly wrote out the orders by hand in those pre-computer days. Not to mention unpacking, checking, making up the orders and getting them delivered on time. Those magical days of reading behind the counter were now a nostalgic memory.

Ten years were to go by in this way. The children, and the book shop, grew surprisingly well. We had Richard Adams (Watership Down) come to our small shop in the English Lake District for a signing of Plague Dogs, and sold well over 100 copies. We became school and library suppliers, I gave talks, ran book clubs, and soon became absorbed in reading masses of book catalogues instead of bestsellers, and each night painstakingly wrote out the orders by hand in those pre-computer days. Not to mention unpacking, checking, making up the orders and getting them delivered on time. Those magical days of reading behind the counter were now a nostalgic memory.As was any writing of my own.

Most of all I helped customers to find just the book they wanted to read, by an author they couldn't remember but the book had a girl and a child on the jacket. they wanted the War and Peace that was on the telly and not that big thick Penguin edition; and whatever that story was that had been read on Radio Four the other afternoon. It was fun, it was challenging, it taught me a great deal about the publishing industry, about books and people, but left me no time to write. Not that it mattered any more, as my confidence had entirely drained away, and I knew in my heart that I could never join these luminaries that graced our shelves. Maybe I'd get back to that when I was a better writer. Sadly, it didn't cross my mind that I never would achieve that blissful state if I didn't practise my craft.

It wasn't until after I'd sold the buisness that I began to take my writing seriously, and yes, I did find that having spent those years in the book trade did help me in many ways. I was aware of what book buyers were looking for, what was commercial, how genres worked, but the craft of turning out a good story cannot be learnt. You can either do that or you can't. So how did I get started? How did I find the confidence? Well, it was an ill wind that blew me some good. I'll tell you more about that next time.

Published on June 03, 2011 00:00

May 30, 2011

Suffragettes

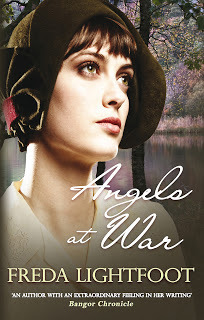

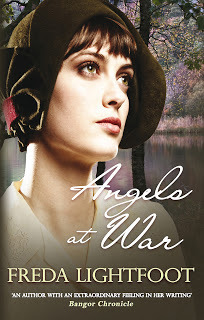

My latest title, Angels at War, out this month in paperback, is the sequel to House of Angels, although the story will stand alone. Again this book is set in the Lake District, partly in the beautiful Kentmere Valley around the time of the First World War It's a beautiful quiet corner of England which hasn't changed much since. The nearest village is Staveley, situated between Kendal and Windermere, and the hills can offer some of the best walking the Lakes. Here is picture to tempt you to visit.

But this book is also about suffragettes. The suffragette movement in Great Britain was focused around Manchester as that is where Emeline Pankhurst and her family lived. The general election of 1905 brought it to the attention of the wider nation when Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenny interrupted Sir Edward's speech with the cry: 'Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?'

They were charged with assault and arrested. The women further shocked the world by refusing to pay the shilling fine, and were consequently thrown in jail. Never before had English suffragists resorted to violence, but it was the start of a long campaign. Their headquarters were transferred from Manchester to London and by 1908, and now dubbed the suffragettes, they were marching through London, interrupting MP's speeches, assaulting policemen who attempted to arrest them, chaining themselves to fences, even sending letter bombs and breaking the windows of department stores and shops in Bond Street. They went on hunger-strikes while incarcerated, brutalised in what became known as the 'Cat and Mouse Act.' This 'war' did not end until 1928 when women were finally granted the vote in equal terms with men. They showed enormous courage and tenacity, were prepared to make any sacrifice to achieve their ends.

Livia is one such woman. She is fiercely independent – a 'modern' woman in her eyes, and having suffered at the hands of a brutal father, she is reluctant to give up her independence and subject herself to the control of any male. She dreams of bringing back to life the neglected drapery business, but standing in her way is the wealthy and determined Matthew Grayson who has been appointed to oversee the restoration of the business. His infuriating stubbornness clashes with Livia's tenacity and the pair get off to a bad start. She then joins the Suffragette Movement which puts further strain on her relationship with Jack, the other man in her life, who she has promised to marry one day.

Livia is one such woman. She is fiercely independent – a 'modern' woman in her eyes, and having suffered at the hands of a brutal father, she is reluctant to give up her independence and subject herself to the control of any male. She dreams of bringing back to life the neglected drapery business, but standing in her way is the wealthy and determined Matthew Grayson who has been appointed to oversee the restoration of the business. His infuriating stubbornness clashes with Livia's tenacity and the pair get off to a bad start. She then joins the Suffragette Movement which puts further strain on her relationship with Jack, the other man in her life, who she has promised to marry one day.

I've written about suffragettes before, as the subject fascinates me. How passionate these women must have felt to put their lives at risk in the way they did. Here is a description from the book of the force feeding ritual.

Excerpt:

This morning when the cell door banged open, instead of the tempting tray of food brought to plague them, came a small, stocky man with side whiskers and a mole on his chin. The wardress shook Livia awake.

'Get up girl, the doctor needs to examine you. We can't have you die on us for lack of food.'

There followed a humiliating examination in which she was again poked and prodded, a stethoscope held to her chest, her pulse taken. When he was done he turned to the wardress and gave a nod. The wardress smiled, as if he'd said something to please her. 'If you will not eat of your own accord, then we must find a way to make you.

There were four of them now crowding into the cell, huge Amazonian women with muscles on them like all-in wrestlers, and they brought with them such a bewildering assortment of equipment that even Mercy paled.

'Dear lord, they're going to force feed us.'

They dealt with Mercy first. She fought like a tiger while Livia cried and begged them to stop, and finally sobbed her heart out as her protests were ignored. The four women held Mercy down, shoved in the tube and poured the liquid mixture into her stomach. When they were done they dropped her limp body back on the bed.

Then it was Livia's turn.

She tried to run but there was no escape. They picked her up bodily and strapped her into a chair by her wrists, ankles and thighs, then tied a sheet under her chin. The sour breath and stale sweat of the women's armpits made her want to vomit; their heavy breasts suffocating her as they held her down. The wardress was panting with the effort of trying to force open her mouth, while another woman held her nose closed. Livia did her utmost to resist, heart racing, teeth clenched, but she could scarcely breathe.

Then she felt the cold taste of metal slide between her lips. The implement, whatever it was, cut into her gums as the wardress attempted to prise them open. Livia tried to jerk her head away but it was held firmly by one of the women standing behind her. Once again pictures flashed into her mind of the tower room at Angel House, the place where her father had carried out unspeakable tortures upon the three sisters, bullying one in order to control the other

Livia hadn't been able to escape then, and she couldn't now.

The constant stabbing at her gums and teeth was every bit as painful as having one drawn. The steel probe scraped against her gums, and Livia tasted the iron saltiness of her own blood, felt it trickle down her throat. She heard the rasp of a screw, felt the inexorable pressure of a lever. Either she opened her teeth beneath the unrelenting pressure of the steel instrument, or they would shatter. That's if she didn't die of suffocation first.

As Livia snatched at a breath a tube was instantly shoved down into her stomach. 'Gocha!' the woman cried in triumph.

It scraped down her dry throat, causing the muscles to convulse. Then the screw, or lever, whatever it was, jammed firmly between her teeth so that she could resist no more as a curdled mix of milk and egg was poured into her.

Livia felt as if she were choking, as if her entire body were filling up with the liquid and drowning her. When the tube was finally pulled out, the whole mess seemed to explode out of her, spraying the clean aprons and hard, unyielding faces of her assailants. They were furious and flung her on to the hard bed, gathered up their equipment and left her blessedly in peace, stinking of sour milk and vomit.

Angels at War, published by Allison & Busby £7.99 paperback - now released.

But this book is also about suffragettes. The suffragette movement in Great Britain was focused around Manchester as that is where Emeline Pankhurst and her family lived. The general election of 1905 brought it to the attention of the wider nation when Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenny interrupted Sir Edward's speech with the cry: 'Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?'

They were charged with assault and arrested. The women further shocked the world by refusing to pay the shilling fine, and were consequently thrown in jail. Never before had English suffragists resorted to violence, but it was the start of a long campaign. Their headquarters were transferred from Manchester to London and by 1908, and now dubbed the suffragettes, they were marching through London, interrupting MP's speeches, assaulting policemen who attempted to arrest them, chaining themselves to fences, even sending letter bombs and breaking the windows of department stores and shops in Bond Street. They went on hunger-strikes while incarcerated, brutalised in what became known as the 'Cat and Mouse Act.' This 'war' did not end until 1928 when women were finally granted the vote in equal terms with men. They showed enormous courage and tenacity, were prepared to make any sacrifice to achieve their ends.

Livia is one such woman. She is fiercely independent – a 'modern' woman in her eyes, and having suffered at the hands of a brutal father, she is reluctant to give up her independence and subject herself to the control of any male. She dreams of bringing back to life the neglected drapery business, but standing in her way is the wealthy and determined Matthew Grayson who has been appointed to oversee the restoration of the business. His infuriating stubbornness clashes with Livia's tenacity and the pair get off to a bad start. She then joins the Suffragette Movement which puts further strain on her relationship with Jack, the other man in her life, who she has promised to marry one day.

Livia is one such woman. She is fiercely independent – a 'modern' woman in her eyes, and having suffered at the hands of a brutal father, she is reluctant to give up her independence and subject herself to the control of any male. She dreams of bringing back to life the neglected drapery business, but standing in her way is the wealthy and determined Matthew Grayson who has been appointed to oversee the restoration of the business. His infuriating stubbornness clashes with Livia's tenacity and the pair get off to a bad start. She then joins the Suffragette Movement which puts further strain on her relationship with Jack, the other man in her life, who she has promised to marry one day.I've written about suffragettes before, as the subject fascinates me. How passionate these women must have felt to put their lives at risk in the way they did. Here is a description from the book of the force feeding ritual.

Excerpt:

This morning when the cell door banged open, instead of the tempting tray of food brought to plague them, came a small, stocky man with side whiskers and a mole on his chin. The wardress shook Livia awake.

'Get up girl, the doctor needs to examine you. We can't have you die on us for lack of food.'

There followed a humiliating examination in which she was again poked and prodded, a stethoscope held to her chest, her pulse taken. When he was done he turned to the wardress and gave a nod. The wardress smiled, as if he'd said something to please her. 'If you will not eat of your own accord, then we must find a way to make you.

There were four of them now crowding into the cell, huge Amazonian women with muscles on them like all-in wrestlers, and they brought with them such a bewildering assortment of equipment that even Mercy paled.

'Dear lord, they're going to force feed us.'

They dealt with Mercy first. She fought like a tiger while Livia cried and begged them to stop, and finally sobbed her heart out as her protests were ignored. The four women held Mercy down, shoved in the tube and poured the liquid mixture into her stomach. When they were done they dropped her limp body back on the bed.

Then it was Livia's turn.

She tried to run but there was no escape. They picked her up bodily and strapped her into a chair by her wrists, ankles and thighs, then tied a sheet under her chin. The sour breath and stale sweat of the women's armpits made her want to vomit; their heavy breasts suffocating her as they held her down. The wardress was panting with the effort of trying to force open her mouth, while another woman held her nose closed. Livia did her utmost to resist, heart racing, teeth clenched, but she could scarcely breathe.

Then she felt the cold taste of metal slide between her lips. The implement, whatever it was, cut into her gums as the wardress attempted to prise them open. Livia tried to jerk her head away but it was held firmly by one of the women standing behind her. Once again pictures flashed into her mind of the tower room at Angel House, the place where her father had carried out unspeakable tortures upon the three sisters, bullying one in order to control the other

Livia hadn't been able to escape then, and she couldn't now.

The constant stabbing at her gums and teeth was every bit as painful as having one drawn. The steel probe scraped against her gums, and Livia tasted the iron saltiness of her own blood, felt it trickle down her throat. She heard the rasp of a screw, felt the inexorable pressure of a lever. Either she opened her teeth beneath the unrelenting pressure of the steel instrument, or they would shatter. That's if she didn't die of suffocation first.

As Livia snatched at a breath a tube was instantly shoved down into her stomach. 'Gocha!' the woman cried in triumph.

It scraped down her dry throat, causing the muscles to convulse. Then the screw, or lever, whatever it was, jammed firmly between her teeth so that she could resist no more as a curdled mix of milk and egg was poured into her.

Livia felt as if she were choking, as if her entire body were filling up with the liquid and drowning her. When the tube was finally pulled out, the whole mess seemed to explode out of her, spraying the clean aprons and hard, unyielding faces of her assailants. They were furious and flung her on to the hard bed, gathered up their equipment and left her blessedly in peace, stinking of sour milk and vomit.

Angels at War, published by Allison & Busby £7.99 paperback - now released.

Published on May 30, 2011 09:15

Suffragettes

My latest title, Angels at War, out this month in paperback, is the sequel to House of Angels, although the story will stand alone. Again this book is set in the Lake District, partly in the beautiful Kentmere Valley around the time of the First World War It's a beautiful quiet corner of England which hasn't changed much since. The nearest village is Staveley, situated between Kendal and Windermere, and the hills can offer some of the best walking the Lakes. Here is picture to tempt you to visit.

But this book is also about suffragettes. The suffragette movement in Great Britain was focused around Manchester as that is where Emeline Pankhurst and her family lived. The general election of 1905 brought it to the attention of the wider nation when Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenny interrupted Sir Edward's speech with the cry: 'Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?'

They were charged with assault and arrested. The women further shocked the world by refusing to pay the shilling fine, and were consequently thrown in jail. Never before had English suffragists resorted to violence, but it was the start of a long campaign. Their headquarters were transferred from Manchester to London and by 1908, and now dubbed the suffragettes, they were marching through London, interrupting MP's speeches, assaulting policemen who attempted to arrest them, chaining themselves to fences, even sending letter bombs and breaking the windows of department stores and shops in Bond Street. They went on hunger-strikes while incarcerated, brutalised in what became known as the 'Cat and Mouse Act.' This 'war' did not end until 1928 when women were finally granted the vote in equal terms with men. They showed enormous courage and tenacity, were prepared to make any sacrifice to achieve their ends.

Livia is one such woman. She is fiercely independent – a 'modern' woman in her eyes, and having suffered at the hands of a brutal father, she is reluctant to give up her independence and subject herself to the control of any male. She dreams of bringing back to life the neglected drapery business, but standing in her way is the wealthy and determined Matthew Grayson who has been appointed to oversee the restoration of the business. His infuriating stubbornness clashes with Livia's tenacity and the pair get off to a bad start. She then joins the Suffragette Movement which puts further strain on her relationship with Jack, the other man in her life, who she has promised to marry one day.

Livia is one such woman. She is fiercely independent – a 'modern' woman in her eyes, and having suffered at the hands of a brutal father, she is reluctant to give up her independence and subject herself to the control of any male. She dreams of bringing back to life the neglected drapery business, but standing in her way is the wealthy and determined Matthew Grayson who has been appointed to oversee the restoration of the business. His infuriating stubbornness clashes with Livia's tenacity and the pair get off to a bad start. She then joins the Suffragette Movement which puts further strain on her relationship with Jack, the other man in her life, who she has promised to marry one day.

I've written about suffragettes before, as the subject fascinates me. How passionate these women must have felt to put their lives at risk in the way they did. Here is a description from the book of the force feeding ritual.

Excerpt:

This morning when the cell door banged open, instead of the tempting tray of food brought to plague them, came a small, stocky man with side whiskers and a mole on his chin. The wardress shook Livia awake.

'Get up girl, the doctor needs to examine you. We can't have you die on us for lack of food.'

There followed a humiliating examination in which she was again poked and prodded, a stethoscope held to her chest, her pulse taken. When he was done he turned to the wardress and gave a nod. The wardress smiled, as if he'd said something to please her. 'If you will not eat of your own accord, then we must find a way to make you.

There were four of them now crowding into the cell, huge Amazonian women with muscles on them like all-in wrestlers, and they brought with them such a bewildering assortment of equipment that even Mercy paled.

'Dear lord, they're going to force feed us.'

They dealt with Mercy first. She fought like a tiger while Livia cried and begged them to stop, and finally sobbed her heart out as her protests were ignored. The four women held Mercy down, shoved in the tube and poured the liquid mixture into her stomach. When they were done they dropped her limp body back on the bed.

Then it was Livia's turn.

She tried to run but there was no escape. They picked her up bodily and strapped her into a chair by her wrists, ankles and thighs, then tied a sheet under her chin. The sour breath and stale sweat of the women's armpits made her want to vomit; their heavy breasts suffocating her as they held her down. The wardress was panting with the effort of trying to force open her mouth, while another woman held her nose closed. Livia did her utmost to resist, heart racing, teeth clenched, but she could scarcely breathe.

Then she felt the cold taste of metal slide between her lips. The implement, whatever it was, cut into her gums as the wardress attempted to prise them open. Livia tried to jerk her head away but it was held firmly by one of the women standing behind her. Once again pictures flashed into her mind of the tower room at Angel House, the place where her father had carried out unspeakable tortures upon the three sisters, bullying one in order to control the other

Livia hadn't been able to escape then, and she couldn't now.

The constant stabbing at her gums and teeth was every bit as painful as having one drawn. The steel probe scraped against her gums, and Livia tasted the iron saltiness of her own blood, felt it trickle down her throat. She heard the rasp of a screw, felt the inexorable pressure of a lever. Either she opened her teeth beneath the unrelenting pressure of the steel instrument, or they would shatter. That's if she didn't die of suffocation first.

As Livia snatched at a breath a tube was instantly shoved down into her stomach. 'Gocha!' the woman cried in triumph.

It scraped down her dry throat, causing the muscles to convulse. Then the screw, or lever, whatever it was, jammed firmly between her teeth so that she could resist no more as a curdled mix of milk and egg was poured into her.

Livia felt as if she were choking, as if her entire body were filling up with the liquid and drowning her. When the tube was finally pulled out, the whole mess seemed to explode out of her, spraying the clean aprons and hard, unyielding faces of her assailants. They were furious and flung her on to the hard bed, gathered up their equipment and left her blessedly in peace, stinking of sour milk and vomit.

Angels at War, published by Allison & Busby £7.99 paperback - now released.

But this book is also about suffragettes. The suffragette movement in Great Britain was focused around Manchester as that is where Emeline Pankhurst and her family lived. The general election of 1905 brought it to the attention of the wider nation when Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenny interrupted Sir Edward's speech with the cry: 'Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?'

They were charged with assault and arrested. The women further shocked the world by refusing to pay the shilling fine, and were consequently thrown in jail. Never before had English suffragists resorted to violence, but it was the start of a long campaign. Their headquarters were transferred from Manchester to London and by 1908, and now dubbed the suffragettes, they were marching through London, interrupting MP's speeches, assaulting policemen who attempted to arrest them, chaining themselves to fences, even sending letter bombs and breaking the windows of department stores and shops in Bond Street. They went on hunger-strikes while incarcerated, brutalised in what became known as the 'Cat and Mouse Act.' This 'war' did not end until 1928 when women were finally granted the vote in equal terms with men. They showed enormous courage and tenacity, were prepared to make any sacrifice to achieve their ends.

Livia is one such woman. She is fiercely independent – a 'modern' woman in her eyes, and having suffered at the hands of a brutal father, she is reluctant to give up her independence and subject herself to the control of any male. She dreams of bringing back to life the neglected drapery business, but standing in her way is the wealthy and determined Matthew Grayson who has been appointed to oversee the restoration of the business. His infuriating stubbornness clashes with Livia's tenacity and the pair get off to a bad start. She then joins the Suffragette Movement which puts further strain on her relationship with Jack, the other man in her life, who she has promised to marry one day.

Livia is one such woman. She is fiercely independent – a 'modern' woman in her eyes, and having suffered at the hands of a brutal father, she is reluctant to give up her independence and subject herself to the control of any male. She dreams of bringing back to life the neglected drapery business, but standing in her way is the wealthy and determined Matthew Grayson who has been appointed to oversee the restoration of the business. His infuriating stubbornness clashes with Livia's tenacity and the pair get off to a bad start. She then joins the Suffragette Movement which puts further strain on her relationship with Jack, the other man in her life, who she has promised to marry one day.I've written about suffragettes before, as the subject fascinates me. How passionate these women must have felt to put their lives at risk in the way they did. Here is a description from the book of the force feeding ritual.

Excerpt:

This morning when the cell door banged open, instead of the tempting tray of food brought to plague them, came a small, stocky man with side whiskers and a mole on his chin. The wardress shook Livia awake.

'Get up girl, the doctor needs to examine you. We can't have you die on us for lack of food.'

There followed a humiliating examination in which she was again poked and prodded, a stethoscope held to her chest, her pulse taken. When he was done he turned to the wardress and gave a nod. The wardress smiled, as if he'd said something to please her. 'If you will not eat of your own accord, then we must find a way to make you.

There were four of them now crowding into the cell, huge Amazonian women with muscles on them like all-in wrestlers, and they brought with them such a bewildering assortment of equipment that even Mercy paled.

'Dear lord, they're going to force feed us.'

They dealt with Mercy first. She fought like a tiger while Livia cried and begged them to stop, and finally sobbed her heart out as her protests were ignored. The four women held Mercy down, shoved in the tube and poured the liquid mixture into her stomach. When they were done they dropped her limp body back on the bed.

Then it was Livia's turn.

She tried to run but there was no escape. They picked her up bodily and strapped her into a chair by her wrists, ankles and thighs, then tied a sheet under her chin. The sour breath and stale sweat of the women's armpits made her want to vomit; their heavy breasts suffocating her as they held her down. The wardress was panting with the effort of trying to force open her mouth, while another woman held her nose closed. Livia did her utmost to resist, heart racing, teeth clenched, but she could scarcely breathe.