Freda Lightfoot's Blog, page 16

August 16, 2012

Southport Flower Show 2012

What a glorious day! After all the rain, particular yesterday when the rain sheeted down, today was warm and sunny with not a drop. Wonderful! And what a relief for the organisers. We had a great day, together with our daughter and her friend. We watched the display dog team, the falconry display and the Knights of the damned doing their jousting. Ate ice cream, marvelled at the flower displays and gardens, and bought a bit of bling from the local craft fair. Perfect. The show continues for the rest of this week. Here are some pictures to delight you.

Published on August 16, 2012 09:36

August 10, 2012

The Renaissance Betrothal.

Popular since the Middle Ages, betrothal ceremonies frequently involved some sort of ceremony or symbolic act. This is believed to date back to the time of ancient Rome. In Anglo-Saxon England the joining of hands to seal the betrothal was common as we know from the term ‘handfasting’ to signify a betrothal. In fourteenth and fifteenth century Italy, the betrothal was sealed by a handshake between the parents, or at best the father of the bride and the prospective groom. In sixteenth century France this ritual was known as les accords.

There would be the giving of a ring, often a gimmel ring which was in two parts, one to be worn by the prospective groom, the other by the bride, the two joined together to form the wedding ring. Records indicate the drinking of wine to toast the agreement, or taking part in a sumptuous feast ‘in the name of marriage’, or simply be sealed with a kiss.

There would be the giving of a ring, often a gimmel ring which was in two parts, one to be worn by the prospective groom, the other by the bride, the two joined together to form the wedding ring. Records indicate the drinking of wine to toast the agreement, or taking part in a sumptuous feast ‘in the name of marriage’, or simply be sealed with a kiss.

The betrothal ceremony confirmed that these two people promised to marry one another, an agreement which could be considered more legally binding than the marriage ceremony itself. Once betrothed, if a couple had sexual intercourse, then they were considered married. And a betrothal contract could only be broken if both parties agreed.

Not that the young woman concerned had much say in the matter. Marriage was less about love and more about wealth, position and power, which meant, as we romantic novelists know, plenty of opportunity for extra-curricular activity in the way of affairs. Henry IV is reputed to have enjoyed at least 60 mistresses with whom he sired numerous illegitimate children, and three or four maîtresse-en-titre.

But with Henriette de’Entragues he perhaps took on more than he’d bargained for she had set her sights on nothing less than marriage, and with it a crown. She therefore insisted upon a promesse de matrimonio before agreeing to surrender her maidenhead, allegedly still intact, and becoming his mistress. In a weak moment of overwhelming desire, Henry agreed that if she could give him a son, then he would marry her. A decision which was to create untold problems in the years ahead, and leave Henriette fighting a battle for what she perceived as her rights, at whatever the cost.

But with Henriette de’Entragues he perhaps took on more than he’d bargained for she had set her sights on nothing less than marriage, and with it a crown. She therefore insisted upon a promesse de matrimonio before agreeing to surrender her maidenhead, allegedly still intact, and becoming his mistress. In a weak moment of overwhelming desire, Henry agreed that if she could give him a son, then he would marry her. A decision which was to create untold problems in the years ahead, and leave Henriette fighting a battle for what she perceived as her rights, at whatever the cost.

Next came the fiançailles when the bans were published. The parents, bride and bridegroom would visit the curé together to attend to this important matter. Then came the Epousailles which of course took place in church. The bridegroom was not allowed to enter without giving a considerable sum in alms, and guests were chosen to attend the wedding breakfast with an eye to the money they’d be likely to give. A bowl was handed round at dinner into which donations for a ‘nest-egg’ for the couple could be dropped.

Henry left such traditions to the bourgeoisie, but provided well for all his children, whatever their status, and was a loving father. Those he had with Henriette shared the royal nursery with the legitimate heirs he had with his queen, Marie de Medici, much to that lady’s displeasure. But Henry loved to play with them, and it was so much more practical to keep them all together in one place. The people of Paris were highly entertained by the fact that his mistress and queen were often enceinte at the same time.

The Queen and the Courtesan, published 29 June, can be found as a paperback or ebook here:

Amazon

There would be the giving of a ring, often a gimmel ring which was in two parts, one to be worn by the prospective groom, the other by the bride, the two joined together to form the wedding ring. Records indicate the drinking of wine to toast the agreement, or taking part in a sumptuous feast ‘in the name of marriage’, or simply be sealed with a kiss.

There would be the giving of a ring, often a gimmel ring which was in two parts, one to be worn by the prospective groom, the other by the bride, the two joined together to form the wedding ring. Records indicate the drinking of wine to toast the agreement, or taking part in a sumptuous feast ‘in the name of marriage’, or simply be sealed with a kiss.The betrothal ceremony confirmed that these two people promised to marry one another, an agreement which could be considered more legally binding than the marriage ceremony itself. Once betrothed, if a couple had sexual intercourse, then they were considered married. And a betrothal contract could only be broken if both parties agreed.

Not that the young woman concerned had much say in the matter. Marriage was less about love and more about wealth, position and power, which meant, as we romantic novelists know, plenty of opportunity for extra-curricular activity in the way of affairs. Henry IV is reputed to have enjoyed at least 60 mistresses with whom he sired numerous illegitimate children, and three or four maîtresse-en-titre.

But with Henriette de’Entragues he perhaps took on more than he’d bargained for she had set her sights on nothing less than marriage, and with it a crown. She therefore insisted upon a promesse de matrimonio before agreeing to surrender her maidenhead, allegedly still intact, and becoming his mistress. In a weak moment of overwhelming desire, Henry agreed that if she could give him a son, then he would marry her. A decision which was to create untold problems in the years ahead, and leave Henriette fighting a battle for what she perceived as her rights, at whatever the cost.

But with Henriette de’Entragues he perhaps took on more than he’d bargained for she had set her sights on nothing less than marriage, and with it a crown. She therefore insisted upon a promesse de matrimonio before agreeing to surrender her maidenhead, allegedly still intact, and becoming his mistress. In a weak moment of overwhelming desire, Henry agreed that if she could give him a son, then he would marry her. A decision which was to create untold problems in the years ahead, and leave Henriette fighting a battle for what she perceived as her rights, at whatever the cost.Next came the fiançailles when the bans were published. The parents, bride and bridegroom would visit the curé together to attend to this important matter. Then came the Epousailles which of course took place in church. The bridegroom was not allowed to enter without giving a considerable sum in alms, and guests were chosen to attend the wedding breakfast with an eye to the money they’d be likely to give. A bowl was handed round at dinner into which donations for a ‘nest-egg’ for the couple could be dropped.

Henry left such traditions to the bourgeoisie, but provided well for all his children, whatever their status, and was a loving father. Those he had with Henriette shared the royal nursery with the legitimate heirs he had with his queen, Marie de Medici, much to that lady’s displeasure. But Henry loved to play with them, and it was so much more practical to keep them all together in one place. The people of Paris were highly entertained by the fact that his mistress and queen were often enceinte at the same time.

The Queen and the Courtesan, published 29 June, can be found as a paperback or ebook here:

Amazon

Published on August 10, 2012 00:30

August 3, 2012

Writers Holiday

Enjoyed a wonderful week at Writers Holiday at Caerleon in South Wales. The weather was glorious, the talks and workshops stimulating, and the company most relaxing and friendly. Thanks to Gerry and Ann for such a successful week. I'm already looking forward to next year.

Here are the medieval dancers who most regally entertained us one evening, giving us some fascinating information not only about dancing, but also about costume.

And here is Jane Wenham-Jones entertaining us in her own inimitable style.

And on the last night is the wonderful Male voice choir, which I missed this year as I had to leave early, but they are a star act.

For more information check out their website:

http://www.writersholiday.net/

Here are the medieval dancers who most regally entertained us one evening, giving us some fascinating information not only about dancing, but also about costume.

And here is Jane Wenham-Jones entertaining us in her own inimitable style.

And on the last night is the wonderful Male voice choir, which I missed this year as I had to leave early, but they are a star act.

For more information check out their website:

http://www.writersholiday.net/

Published on August 03, 2012 07:49

July 31, 2012

Tatton Park Flower Show

We had a lovely day at Tatton Park Flower Show. As I've been away all week at Writers Holiday (I'll post about that next) this is my first opportunity to upload my photos. Here are a few of the best to inspire you with your own gardens. I love the Votes for Women one, and the ones done by the schools. Here's Thomas the Tank Engine. Since it's Olympics year we'll start with the pole vaulter, worked in wicker.

Published on July 31, 2012 03:03

July 27, 2012

Inspiration and Research

Writers are always on the look out for ideas. I find inspiration from many sources: family memories, history of the places I’ve lived in such as the beautiful English Lake District and Cornwall. I pick up ideas from day time TV, snippets in newspapers and magazines, dinner parties, and even ear-wigging the next table in a restaurant, as all writers do. I’ve dipped into the more interesting parts of my own life, such as when we had a smallholding and tried the ‘good life’. And having fully exploited those, moved on to interviewing people for more fascinating stories.

However, with the current historicals I’m writing, there are no people alive to interview as they take place in sixteenth century France. For these I’ve needed to delve into the archives. I’m one of those oddballs who find such research fascinating, and have hundreds of books and magazines, memoirs and documents of all kinds that I squirrel away in case they come in handy one day.

It was finding an old book on my shelf that set me on the quest of writing about Marguerite de Valois in the first place. It was a biography of her called ‘The Queen of Hearts’. I’d bought it second hand years ago in Hay-on-Wye at the book festival. I was looking for an interesting subject and happened to spot it on my shelves so picked it up to read one night on my way to bed.

I discovered Margot, as she was known, was the daughter of Catherine de Medici and was instantly intrigued by the fascinating life she led, the scandal and intrigue that surrounded her, and the dangers she faced. All grist to the mill for a romantic novelist.

It set me on the trail of finding out more about her, about Catherine, and the French court at that time, collecting or downloading many books. I started reading and researching for what turned out to be a trilogy, starting with ‘Hostage Queen’, then ‘Reluctant Queen’, and finally ‘The Queen and the Courtesan’.

Researching Gabrielle (seen left) was equally fascinating.

It was easy to feel overwhelmed at times by all the information I found, so I learned to constantly ask myself if it was relevant to my heroine. It was how her actions affected history that mattered most, I decided. More, perhaps, than how history affected her. But as we all know history is written by the victors, I needed to read widely to gain other viewpoints too, and to decide what was true and what political propaganda.

In this last of the trilogy, the story is that of Henriette d’Entragues, who wasn’t satisfied with simply being the mistress of Henry IV of France, she wanted a crown too. Before agreeing to surrender her maidenhead, which she artfully claimed was still intact, she insisted upon a written promise. Ever weak where women were concerned, Henry agreed that if she provided him with a son, he would make her his queen. His advisers and ministers, not surprisingly, were very much against the idea, as they had an Italian princess, Marie de Medici, in mind, so consequently began their own plotting to seal the match. France was in sore need of the money she could bring to the marriage. Henriette rather unkindly called her the ‘fat banker’.

Henriette was a fascinating character to write as her greed and ambition didn’t make her particularly likeable, so she was in a way an anti-heroine, if there is such a thing. I wanted the reader to disapprove of her, but not so badly that they switched off and closed the book. She also had to be true to her time and yet appeal to the modern reader. Quite a challenge.

Marie de Medici, was not an easy women either, but then she did have a mistress and an ex-wife to deal with. In this kind of historical you can’t just make your characters or the story up, but I found it fascinating searching for details on what these people were like, how they related to each other, and discovering how Henriette set about her quest for a crown.

The Queen and the Courtesan, published 29 June, can be found as a paperback or ebook here:

Amazon

Most of my back titles are now available as ebooks on Amazon, Kobo, Smashwords etc. Links to them can be found on my website:

http://www.fredalightfoot.co.uk

However, with the current historicals I’m writing, there are no people alive to interview as they take place in sixteenth century France. For these I’ve needed to delve into the archives. I’m one of those oddballs who find such research fascinating, and have hundreds of books and magazines, memoirs and documents of all kinds that I squirrel away in case they come in handy one day.

It was finding an old book on my shelf that set me on the quest of writing about Marguerite de Valois in the first place. It was a biography of her called ‘The Queen of Hearts’. I’d bought it second hand years ago in Hay-on-Wye at the book festival. I was looking for an interesting subject and happened to spot it on my shelves so picked it up to read one night on my way to bed.

I discovered Margot, as she was known, was the daughter of Catherine de Medici and was instantly intrigued by the fascinating life she led, the scandal and intrigue that surrounded her, and the dangers she faced. All grist to the mill for a romantic novelist.

It set me on the trail of finding out more about her, about Catherine, and the French court at that time, collecting or downloading many books. I started reading and researching for what turned out to be a trilogy, starting with ‘Hostage Queen’, then ‘Reluctant Queen’, and finally ‘The Queen and the Courtesan’.

Researching Gabrielle (seen left) was equally fascinating.

It was easy to feel overwhelmed at times by all the information I found, so I learned to constantly ask myself if it was relevant to my heroine. It was how her actions affected history that mattered most, I decided. More, perhaps, than how history affected her. But as we all know history is written by the victors, I needed to read widely to gain other viewpoints too, and to decide what was true and what political propaganda.

In this last of the trilogy, the story is that of Henriette d’Entragues, who wasn’t satisfied with simply being the mistress of Henry IV of France, she wanted a crown too. Before agreeing to surrender her maidenhead, which she artfully claimed was still intact, she insisted upon a written promise. Ever weak where women were concerned, Henry agreed that if she provided him with a son, he would make her his queen. His advisers and ministers, not surprisingly, were very much against the idea, as they had an Italian princess, Marie de Medici, in mind, so consequently began their own plotting to seal the match. France was in sore need of the money she could bring to the marriage. Henriette rather unkindly called her the ‘fat banker’.

Henriette was a fascinating character to write as her greed and ambition didn’t make her particularly likeable, so she was in a way an anti-heroine, if there is such a thing. I wanted the reader to disapprove of her, but not so badly that they switched off and closed the book. She also had to be true to her time and yet appeal to the modern reader. Quite a challenge.

Marie de Medici, was not an easy women either, but then she did have a mistress and an ex-wife to deal with. In this kind of historical you can’t just make your characters or the story up, but I found it fascinating searching for details on what these people were like, how they related to each other, and discovering how Henriette set about her quest for a crown.

The Queen and the Courtesan, published 29 June, can be found as a paperback or ebook here:

Amazon

Most of my back titles are now available as ebooks on Amazon, Kobo, Smashwords etc. Links to them can be found on my website:

http://www.fredalightfoot.co.uk

Published on July 27, 2012 00:30

July 13, 2012

The Oppression of Women in Historical Fiction.

Women’s oppression across history has been written about constantly, even during the 60s, in an age of strong feminism. The desire for power, male domination, violence and control, and captive women, have been recurring themes from Jane Eyre to the present day. Drabble, Byatt, and Jean Rhys in her retelling of Jane Eyre in Wide Sargossa Sea have all used this theme. As have countless gothic and romantic suspense novels. Is this because women fear reliving the fates of their mothers?

Women’s oppression across history has been written about constantly, even during the 60s, in an age of strong feminism. The desire for power, male domination, violence and control, and captive women, have been recurring themes from Jane Eyre to the present day. Drabble, Byatt, and Jean Rhys in her retelling of Jane Eyre in Wide Sargossa Sea have all used this theme. As have countless gothic and romantic suspense novels. Is this because women fear reliving the fates of their mothers?‘Happy women, like happy countries, they say, have no histories,’ says Harriet in Victoria Holt’s Menfreya in the Morning.

Eleanor Hibbert, in her different incarnations, as Jean Plaidy, Holt, and Philippa Carr used this theme constantly. Her Plaidy novels were written in the 3rd person, which gave them a rounder, more objective viewpoint, if slightly distanced. Her others were in 1st and therefore more personal and emotional.

Gregory too writes about the lot of women. About primogeniture and how women are ignored. Even her biographical fiction is about exploited women, forced to marry for political reasons, or used by their political ambitious fathers. Her early novels also deal with the theme of exploitation in other ways, such as the agricultural peasant after the enclosures. Writing these novels in the 1980s, during the time of the miners’ strikes, this would strike a chord with readers, as it tuned in with the radical political consciousness of the time.

As with Gregory, so with Susan Howatch, who wrote about wealth and inheritance, stating that women were considered a possession as was a house or land. But she plunders history for her stories: Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine for Penmarrick, and Edward I, II and III for Cashelmara. She is saying that nothing changes. She used history itself as her inspiration, disguised and relocated while echoing the universal truth of her theme of exploitation of women in dysfunctional families. Both Howatch and Gregory teach us that history does not exist in a vacuum, that nothing really changes about human nature, despite progress in other fields.

Perhaps it is easier for us to view these problems through the prism of nostalgia. Class/sexual inequalities/social differences/violent abuse/illegitimacy and other strong themes, are often best viewed at a distance. They work because they don’t have to be defended, criticised or judged. People like to think - ah yes, that’s how it was back then. They are aware the issue still has a resonance today, yet it is easier to think of it with the benefit of hindsight. Its awfulness is often stressed quite strongly, yet as it is safely in the past, this allows a slight air of unreality or fantasy in the way the subject is depicted.

In the 1970s the theme of exploited women was turned on its head and the liberation of women became a popular theme in racy historicals. Known as bodice rippers these started with Kathleen Woodiwise: The Flame and the Flower. Rosemary Rogers: Sweet Savage Love. They depicted accurate sex in inaccurate history. History was pure fantasy, a mere backdrop. Women were still incarcerated, degraded, violated, and yet they maintained their sense of adventure and spirit of defiance and independence. The strength of the abused woman resonated throughout, giving women the right to enjoy sex, and to exploit men just as they had exploited women throughout history. Ultimately they tamed the hero. They conquered evil with love, a theme which was picked up by Mills & Boon at the time, and has featured strongly in romantic fiction ever since.

Marguerite de Valois in ‘Hostage Queen’ was most certainly an oppressed woman, bullied by her mother, Catherine de Medici, and imprisoned by her husband, Henry of Navarre, but never defeated. She remained a strong woman, a feminist before her time demanding equal rights, and far more intelligent than her mad brothers. She was the Queen that France needed but never got.

Gabrielle d’Estrées who takes the lead in Reluctant Queen, was sold by her mother, twice, to different men, so quite a different sort of oppression. Fortunately she was adored by Henry IV, whose mistress she became, so things improved, at least for a time.

In ‘The Queen and the Courtesan’, I set out giving Henriette d’Entragues the benefit of the doubt, that she was used by her father and brother. But while they were certainly complicit in all the intrigue in which they were engaged, I soon decided that she was no innocent victim. She was the very opposite of an oppressed woman, one who manipulated events to win herself the crown she craved. But did she succeed?

The Queen and

the Courtesan, published 29 June, can be found as a paperback or ebook here:

Amazon

Published on July 13, 2012 00:30

June 29, 2012

The History of the Humble Apron

Do our daughters, I wonder, appreciate the value and history of the humble apron? My gran wore one of the overall variety, a floral wrapover that completely covered her dress, and she thought little of the frilly version my mother wore. Yet they both served the same purpose, or rather multi-purpose. The principal use of both was primarily to protect the dress they wore underneath, because they had very few of those and many aprons. It was also far easier to wash aprons than dresses, particularly at a time when fancy washing machines were in short supply.

But an apron had many other uses. It served as a potholder for removing hot pans from the oven, or to place a hot apple pie to cool on the window sill. It was perfect for drying children’s tears, rubbing clean a dirty face, or for a child to hide behind when confronted by strangers. It could be knelt on while scrubbing a step, and it was surprising how much furniture an apron could dust in a matter of seconds if unexpected company suddenly called, or how quickly it could vanish and leave Mum looking clean as a new pin.

Within the mysteries of its pocket could be found a boiled sweet, a few pegs for the washing line, a handkerchief for a child’s runny nose, a hair grip, scissors, and a bit of string in case something should need tying up or ‘fettling’ as my gran would say.

An apron often came in useful when a bag or basket wasn’t to hand. It could be used for carrying eggs from the hen coup, or vegetables picked from the garden. Logs and kindling would be brought into the kitchen in that apron, and after the peas had been shelled sitting on a stool at the kitchen door, it would carry out the hulls to the compost heap.

Mum would use it to wipe a perspiring brow as she bent over the hot fire or cooker, to wipe her hands on if called unexpectedly to the door. And when the weather turned cold she’d wrap it around her arms while she stood on the doorstep enjoying a bit of crack with a neighbour.

And on top of all this, it could also be seen as a sex symbol, as shown in this Lucille Ball picture.

Our daughters, not to mention ‘elf and safety’, would surely have a fit at the thought of all the germs that no doubt could be found upon that apron. But I don't think I ever caught anything infectious from any of them, only a great deal of love.

Published on June 29, 2012 12:30

June 15, 2012

The History of Washing and Ironing

Dollies & possers

I can well remember watching my grandmother using a posser, and even helping on occasion. It comprised a long stick with a heavy copper disc on the end. Those with three wooden legs were called Dollies: a feminine name perhaps emphasising the woman’s place in the kitchen, just as we often call a drying rack a clothes maiden.

Their purpose was to agitate the cloth in a wash-tub or dolly-tub as it was often called, although there were regional variations on styles and names. They were particularly suitable for cotton sheets or towels which needed to steep in boiling hot water then be pumped up and down with the stick to circulate them and presumably dislodge the dirt. The cotton fabric needed to be fairly robust to take the beating. I should think the woman concerned would develop strong arm muscles as a result. But then washerwomen were expected to be tough and strong, and were considered very much at the bottom of the ladder when it came to class. The finer clothes in a large household were the responsibility of the lady’s maid.

Mangles

Strong muscles were also a necessity to push and pull the earliest box mangle back and forth with the leather straps or wooden handles. I would surmise that two laundry maids would be required for this task, one at each side. The weight of the box filled with stones, or sand, pressed household linens that were spread flat beneath the rollers, or else were wound about them. The early 19th century saw a variety of newly invented mangles with a system of gears, wheels, and handles which were meant to lighten the laundry maid’s task by helping her to move this box. You could almost view it as an early rotary iron.

An advertisement stated it was “An important improvement in the construction of the common mangle ... by Mr. Baker, of Fore Street, London, by which the otherwise unwieldy heavy box was moved with great facility backwards and forwards, by a continuous motion of the handle in one direction; and by the addition of a fly wheel to equalize the motion, a great amount of muscular exertion is saved to the individual working the machine.”

By 1823 we saw the invention of the upright mangle, which took up much less space and was therefore available for use in more humble homes. Mangles also became known as wringers, as rather than smoothing the cloth, they were now mainly expected to simply rid the clothes of water.

Irons:

Clothes then needed to be ironed. No-one can say exactly when people started to press cloth smooth, but we know that the Chinese were using pans filled with hot coals for the purpose more than a thousand years ago. Blacksmiths started making simple flat irons in the late Middle Ages, which continued to be in use for hundreds of years. I remember my grandma heating her flat irons on the hearth plate of her Lancashire range, warming one while she used the other. She had several, in fact, of various weights but all of them extremely heavy.

This is a picture of an ironing stove used to heat irons in the laundry of a large country house. Having tested one myself, I’d say the laundry maids would indeed need to have strong arms to even lift one, let alone swish it back and forth over a sheet.

Flat irons were often called sad iron (or sadiron) an old word meaning solid. In Scotland people used gusing (or goosing) irons, the name coming from the goose-neck curve in the handle.

The charcoal or box iron had a hinged lid which you lifted so that you could fill the container with hot coals. The air holes kept the charcoal smouldering. They generally came with their own stand.

Then there were goffering, crimping and fluting irons which were meant for frilled cuffs and collars, and for the many ribbons, trimmings and intricate ruffles on a Victorian gown, which were, of course, a sign of status. No well-dressed infant could be seen out without her bonnet trimmed with double frills. This is an Italian goffering iron for that very purpose.

Irons had to be kept immaculately clean and polished, and regularly greased to avoid rusting. The temperature had to be constantly checked otherwise the fabric could be scorched. My Gran used to spit on hers, not being a lady of quality. Some would hold it close to their cheek, a somewhat risky procedure described in The Old Curiosity Shop.

I can well remember watching my grandmother using a posser, and even helping on occasion. It comprised a long stick with a heavy copper disc on the end. Those with three wooden legs were called Dollies: a feminine name perhaps emphasising the woman’s place in the kitchen, just as we often call a drying rack a clothes maiden.

Their purpose was to agitate the cloth in a wash-tub or dolly-tub as it was often called, although there were regional variations on styles and names. They were particularly suitable for cotton sheets or towels which needed to steep in boiling hot water then be pumped up and down with the stick to circulate them and presumably dislodge the dirt. The cotton fabric needed to be fairly robust to take the beating. I should think the woman concerned would develop strong arm muscles as a result. But then washerwomen were expected to be tough and strong, and were considered very much at the bottom of the ladder when it came to class. The finer clothes in a large household were the responsibility of the lady’s maid.

Mangles

Strong muscles were also a necessity to push and pull the earliest box mangle back and forth with the leather straps or wooden handles. I would surmise that two laundry maids would be required for this task, one at each side. The weight of the box filled with stones, or sand, pressed household linens that were spread flat beneath the rollers, or else were wound about them. The early 19th century saw a variety of newly invented mangles with a system of gears, wheels, and handles which were meant to lighten the laundry maid’s task by helping her to move this box. You could almost view it as an early rotary iron.

An advertisement stated it was “An important improvement in the construction of the common mangle ... by Mr. Baker, of Fore Street, London, by which the otherwise unwieldy heavy box was moved with great facility backwards and forwards, by a continuous motion of the handle in one direction; and by the addition of a fly wheel to equalize the motion, a great amount of muscular exertion is saved to the individual working the machine.”

By 1823 we saw the invention of the upright mangle, which took up much less space and was therefore available for use in more humble homes. Mangles also became known as wringers, as rather than smoothing the cloth, they were now mainly expected to simply rid the clothes of water.

Irons:

Clothes then needed to be ironed. No-one can say exactly when people started to press cloth smooth, but we know that the Chinese were using pans filled with hot coals for the purpose more than a thousand years ago. Blacksmiths started making simple flat irons in the late Middle Ages, which continued to be in use for hundreds of years. I remember my grandma heating her flat irons on the hearth plate of her Lancashire range, warming one while she used the other. She had several, in fact, of various weights but all of them extremely heavy.

This is a picture of an ironing stove used to heat irons in the laundry of a large country house. Having tested one myself, I’d say the laundry maids would indeed need to have strong arms to even lift one, let alone swish it back and forth over a sheet.

Flat irons were often called sad iron (or sadiron) an old word meaning solid. In Scotland people used gusing (or goosing) irons, the name coming from the goose-neck curve in the handle.

The charcoal or box iron had a hinged lid which you lifted so that you could fill the container with hot coals. The air holes kept the charcoal smouldering. They generally came with their own stand.

Then there were goffering, crimping and fluting irons which were meant for frilled cuffs and collars, and for the many ribbons, trimmings and intricate ruffles on a Victorian gown, which were, of course, a sign of status. No well-dressed infant could be seen out without her bonnet trimmed with double frills. This is an Italian goffering iron for that very purpose.

Irons had to be kept immaculately clean and polished, and regularly greased to avoid rusting. The temperature had to be constantly checked otherwise the fabric could be scorched. My Gran used to spit on hers, not being a lady of quality. Some would hold it close to their cheek, a somewhat risky procedure described in The Old Curiosity Shop.

Published on June 15, 2012 00:30

June 10, 2012

A Visit to Madrid

Earlier in the spring we enjoyed a short break in Madrid. Since then I've been so busy writing that this is the first chance I've found to put up the pictures.Rather pathetic, I know, but I need a clone for these jobs.

I loved the architecture with elements of Baroque and Roccoco style.

Strolling through the streets in an evening in search of a meal is always pleasant.

How about hanging out your washing on the roof, as this guy is doing in the Plaza Mayor.

It made me giddy just watching him.

Below is the bronze statue of Philip III, created by Italian sculptors Giovanni de Bologna

and his apprentice Pietro Tacca in 1616.

Still a centre for festivities Plaza Mayor is also a pleasant place to sit and drink coffee or a glass of wine to watch the world go by.

And here is the royal palace where King Carlos and Queen Sofia reside. You can view most of it save for those rooms currently used for formal business.

Madrid is a beautiful city well worth a visit. With wonderful parks such as Retiro Park.

The Cathedral

Fountains

Busy streets, theatres, shops, and markets.

We visited the Prado Art Gallery, and the Queen Sofia gallery for more modern art including Guernica by Picasso. Absolutely amazing. We stayed at a hotel in the centre and found it very easy to walk around and explore.

I loved the architecture with elements of Baroque and Roccoco style.

Strolling through the streets in an evening in search of a meal is always pleasant.

How about hanging out your washing on the roof, as this guy is doing in the Plaza Mayor.

It made me giddy just watching him.

Below is the bronze statue of Philip III, created by Italian sculptors Giovanni de Bologna

and his apprentice Pietro Tacca in 1616.

Still a centre for festivities Plaza Mayor is also a pleasant place to sit and drink coffee or a glass of wine to watch the world go by.

And here is the royal palace where King Carlos and Queen Sofia reside. You can view most of it save for those rooms currently used for formal business.

Madrid is a beautiful city well worth a visit. With wonderful parks such as Retiro Park.

The Cathedral

Fountains

Busy streets, theatres, shops, and markets.

We visited the Prado Art Gallery, and the Queen Sofia gallery for more modern art including Guernica by Picasso. Absolutely amazing. We stayed at a hotel in the centre and found it very easy to walk around and explore.

Published on June 10, 2012 08:52

March 16, 2012

The San Francisco earthquake of 1906

The San Francisco earthquake of 1906 struck San Francisco and surrounding towns over a distance of almost three hundred miles on the coast of California at 5:12 a.m. on Wednesday, April 18, 1906. The tremors were felt as far north as Oregon and as far south as Los Angeles.

Due to the San Andreas fault, and the Hayward and San Jacinto faults.

San Francisco had always been prone to earthquakes. The city suffered countless tremors each year as the plates constantly shifted against each other and stress built up, and still does. But nothing of this magnitude had been experienced for almost half a century before 1906. And strict codes on construction had been put into place. Sadly it wasn't enough to save them.

Even more devastating than the earthquake itself was the fire that followed which ruptured gas mains, destroyed approximately 25,000 buildings, and 3000 lives were lost.

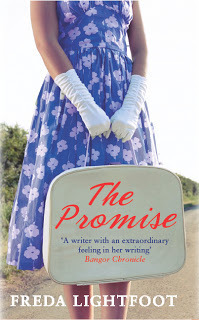

In this short extract from The Promise we see Georgia attempting to escape and save the lives of her mother and sister.

All night the city burnt. By dawn the sky was blood-red, marred by a thick pall of smoke in shades of ochre, rose and lavender. There seemed little hope of ever seeing the sun again. Whole buildings were broken, tilting at impossible angles; twisted columns and pillars stood as if petrified by the flames.

And over all lay a brooding air of silence.

I'd never witnessed anything like it. With not enough water to fight it, and the dynamite blasts to create firebreaks often making matters worse as surrounding buildings couldn't be damped down, the fire had swept the entire district below Sansome. We heard that it had jumped Kearny then devoured Chinatown, gobbling up shops and houses with their pretty balconies with as much ease as it did the paper lanterns and carved wooden dragons which gave the district its unique character.

Hand in hand, we stumbled on. As did hundreds of others, many dragging their trunks and luggage, their children and themselves, up and down San Francisco's unforgiving hills, only to meet a wall of flame at the top and have to run for their lives in the opposite direction, often leaving everything behind.

The fire scorched down the corridors of Frisco's long streets, destroying all in its path and leaving gutted ruin in its wake. The very heat of the flames cracked solid stone, crumbled great pillars, and bent iron and steel into a newly sculpted art form.

Finally we reached Union Square where we managed to grab a few hours sleep huddled together on the grass, along with our fellow refugees. The lucky ones slept in government tents, cooking supper on stoves they'd salvaged from their homes.

'No point in trying for the ferry yet,' they told us. 'The roads are blocked all around with hundreds of refugees desperate to get a boat for Oakland.'

'And the authorities are being hampered by crowds of sightseers pouring off the ferry,' someone else put in. 'Coming to gawp at the scenes of horror and cluttering up the roads and sidewalks. "Earthquake tourists", they're calling them. And tempers are growing ugly.'

I had no wish to have Mama caught up in an affray, and my fragile sister was suffering yet another fit of weeping that might never stop. I thought her close to a breakdown and certainly too exhausted to walk another yard. It seemed that for now we must stay put.

Ten days later we had set up camp in Golden Gate Park. The fires had died at last, leaving our city a smoking ruin, in parts little more than heaps of ash. Some streets were already being cleared of rubble and trailing wires, burst pipes mended, but few buildings were safe to enter, so here we were, sleeping in makeshift shelters or government-issued tents, our throats parched with the acrid taint of smoke, our clothes blackened. Every morning I would stand patiently in the bread queue while Prue did the same in the soup line, and Maura would go off to find a grocery store that might be open and bargain for a scrap of meat or fish. Even if she was successful the task always took her hours, but she was so restless she persisted in her daily search, quite unable to sit still.

Mama sat beneath a piece of corrugated iron atop a pile of boxes and broken chairs, demanding that Prudence, Maura and myself wait on her hand, foot and finger, in lieu of the servants she'd lost.

'I am bored with fish soup,' she would complain, as if we might conjure up a little caviar for her instead.

'And do find me a proper bed, dear. I really cannot tolerate lying on this heap of old coats for much longer.'

'There are no beds, Mama. The fire burnt them all, remember?'

'Then something must be done.'

Poor Cecilia Briscoe. Not a woman accustomed to making do, or suffering any sort of discomfort. Her life had been near perfect until the quake, one of the city's well-to-do with impeccable European bloodlines. More importantly, her daughter Georgia's life too was about to change for ever.

I began to research the earthquake following a wonderful holiday we'd enjoyed in the town. I discovered that people do strange things in the face of disaster, such as marry in haste, or commit atrocities. Life goes on, babies are still born even as people are dying. And keeping track of your loved ones when the world is falling about your ears could not have been easy.

It was with these thoughts in mind that I began to dream up the plot of The Promise. I have set part of the story some fifty or so years on, in post war Lakeland where Chrissie is struggling to understand why she has no contact with her grandmother, and what is the big family secret that her mother refuses to reveal.

SAN FRANCISCO 1904

Georgia Briscoe, in love with British sailor Ellis Cowper, is unwillingly betrothed to Drew Kemp. Her husband is mired in the San Francisco underworld, with a penchant for gambling and other women. Georgia plans to escape to be with the man she loves but Drew has other ideas. And then comes the earthquake…

LONDON, 1948

Kemp travels to the Lake District to meet her grandmother for the first time, only to discover a shocking family secret. As the truth unfurls, the passion, emotion and astounding love that blossomed in San Francisco is revealed forty years earlier, and three generations of one family are tested to their limits.

ebook available from Amazon

Paperback published by Allison & Busby coming in September.

Published on March 16, 2012 16:22

Freda Lightfoot's Blog

- Freda Lightfoot's profile

- 210 followers

Freda Lightfoot isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.