Mark Stevens's Blog, page 53

December 31, 2011

2011: Favorite Reads

Fiction:

The Marriage Plot – Jeffrey Eugenides

The Last Werewolf – Glen Duncan

Hell Is Empty – Craig Johnson

Tunneling to the Center of the Earth – Kevin Wilson

Guards – Ken Bruen

Matterhorn – Karl Marlantis

Non-Fiction:

Into the Silence – Wade Davis (review coming soon)

Extremophilia – Fred Haefele

Wichita Divide – Stephen Singulaar

The Death of Josseline – Margaret Regan

Finding Everett Reuss – David Roberts

Unbroken - Lauren Hillenbrand

The Third Miracle – Bill Briggs

Zeitoun – Dave Eggers

The Last Season – Eric Blehm

Filed under: Books

December 30, 2011

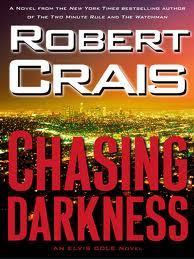

Robert Crais – "Chasing Darkness"

A hard-working detective procedural with a nifty set-up, "Chasing Darkness" doesn't push any stylistic boundaries or shatter the barriers of the genre.

A hard-working detective procedural with a nifty set-up, "Chasing Darkness" doesn't push any stylistic boundaries or shatter the barriers of the genre.

Rather, it respects them, cherishes them.

This is power-packed with plot, hard work and clue finding. Detective Elvis Cole is at the wheel and partner Joe Pike is riding the figurative shotgun seat.

The story gets a jump start with the discovery of a body in a house that's part of a neighborhood being evacuated due to wildfires. The body is that of one Lionel Byrd, who Elvis Cole helped exonerate, three years earlier, from charges he had murdered a young prostitute. Byrd's body is found with a photo album in his lap—a photo album full of grizzly photographs—that make it look as if Cole helped clear a man who should have been convicted.

The strength of "Chasing Darkness" is in the intricate—but easy to follow—plot. That's always a delicate balance, in my mind: putting enough players on the stage to make it interesting but not getting overly complicated, either. This allows Crais to pop a nice surprise on readers at the end and it's a beauty.

Cole works hard and nothing comes easy (always a good combination) as Cole pursues matters deep into the heart of politics and power. "Chasing Darkness" is missing some of Cole's earlier snappy attitude and the story is told with a dry, straightforward style.

To me, it's as if Crais just wanted to step out of the way and let Elvis and Joe take over. And they do.

Filed under: Books

SXSW 2011 Second Hour

(For the top list of songs and an explanation of this list, go here. Suffice it to say these are songs 21-40 out of 1,700 sampled from the annual SXSW juke box.)

1. Elephant Stone – Strangers

http://www.myspace.com/elephantstoneonline

Gorgeous pop with a psychedelic touch.

2. April Smith and the Great Picture Show – Colors

http://www.aprilsmithmusic.com/

@aprilsmithmusic

This one jumped out at my daughter. "I need that," she said. I think we all do. Love the way this one builds. And what a voice.

3. Matthew and the Atlas: Come out of the Woods

http://matthewandtheatlas.com/

I'm not opposed to this whole Mumford & Sons trend, but it better be good.

Nice version here, too: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K42pMUP7fuE

3. Who Made Who: Keep Me in My Plane

In that whole Daft Punk – LCD Soundsystem vein but from the Scandanivian underground, whatever that is. Great groove. Make me feel sane, keep me in my plane. Snappy video too.

4. Tecla: Good Hair

@RebelTec

"Like the asian with the perm, foreheads curled and then they're burned…

Just like everybody always wants what they don't have.."

Attitude to spare, she of the three-tiered wedding cake of keyboards.

5. Broncho: Try Me Out Sometime

http://bronchoband.com/

@BRONCHOBAND

Clash Light with a ringing guitar come-on.

6. Lindi Ortega: Little Lie

http://www.myspace.com/lindimusic

From Toronto with Mexican-Irish roots. Channeling Austin, TX.

7. Wonfu: Do Re Mi

@wonfutour

From Taiwan, channeling Shonen Knife or something more poppy? Don't give up on this track until you hear the shimmering guitar lead toward the end. Not the lick, the lead.

8. Lucy and the Popsonics: Fred Astaire

http://www.myspace.com/lucyandthepopsonics

It's their description: Fuzz-Pop-rock-indie-electronic sound. And they cite as influences: Kraftwerk, the Monks, the Knife, REM, Radiohead, Talking Heads, Devo, the XX.

9. Capsula: Under the Woods

@capsula_band

http://www.capsula.org/band.html

They said it: "They love guitars, fuzz, distortion. Their name comes from David Bowie's song Space Oddity, in spanish means capsule. They sound like mars, dreaming hawaii, a karate fight, flower crowns, vulcano, caramel, gigant waves, turtles in chile, kitten ears. They want to touch your lives and kiss your bones." From Argentina.

10. Brooke Fraser: Something in the Water

http://www.brookefraser.com/

@brookefraser

A light ditty? Maybe. From New Zealand.

11. The Moondoggies: It's a Shame, It's a Pity

http://moondoggiesmusic.com/

@TheMoondoggies

I get a CSNY vibe. The early stuff.

12. Suzanna Choffel: Animal

@SuzannaChofel

http://www.suzannachoffel.com/

Jazzy poppy stuff. Almost mainstream. Almost. Is Austin just thick with talent? I suppose.

13. Sallie Ford & The Sound Outside; Danger

@salliefordmusic

http://www.sallieford.com/lyrics.html

From their website: "Sallie Ford & The Sound Outside vigorously mines a sweet spot between modern and vintage. Sallie's voice has elicited comparisons to classic jazz and blues icons, yet it is stoked with the fire of youth and rebellion, too, an instrument capable of conveying raw emotion and nuanced artistry in the same breath." Yeah, pretty raw emotion.

14. Bell Gardens: Through the Rain

https://www.facebook.com/BellGardens

Beach Boys meets chamber pop and joins forces with Phil Spector. Gorgeous, seductive, surreal pop. Why is this not on the radio? I don't know, either.

15. J-Live: The Way That I Rhyme

@J_Live3TP

"Baby all I got sayin'

I'll walk up in a show and my song starts playin'

I'm like dude…..hell is gonna do that tonight

DJ is looking like: Yeah, my bad, screw that

But all the .. the way that I rhyme

Someone asking: could you play some J-live?

I told them .. skip on that stress

Tell them real DJ don't take request…"

And so on. Fantastic.

16. Leatherbag: Lines

Refugees from Houston now live in….wait for it….Austin. A power trio. From, yes, Austin. Again, Austin. I do not pre-screen "from" information when I listen to these 1,700 songs but Austin shows up over and over again, even on some of the so-called "International" flavor stuff. Not here. This is American rock and roll. From Austin.

17. Sinamantes: The Frog

http://www.reverbnation.com/sinamantes

@sinamantes

From their site: "Created in the middle of the hot and rainy brazilian summer of 2010 by two brazilians and one argentinian, SINAMANTES comes to shorten and enhance connections between different aspects of latin-american pop music."

Mission accomplished. And, please, don't swallow the frog.

18. Cobirds Unite: Crown of Thorns

Good live clip: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iw_pg5u15N4

http://www.reverbnation.com/rustywilloughby

I guess this is really "Rusty Willoughby" and he looks to be one talented individual. From his site: "Largely known for his work with the rock/pop bands Pure Joy, Flop and Llama, Willoughby's mostly lo-key, often lo-fi and decidedly lo-electricity records have flown well under the radar for the last decade or so. Influenced by everything from Woody Guthrie to Jacques Brel…"

Note: not the Pearl Jam Song…

Filed under: Books

December 22, 2011

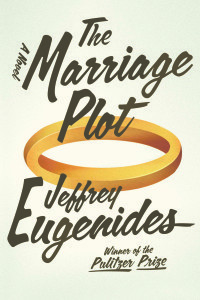

Jeffrey Euginedes – "The Marriage Plot"

"We're trying to find out why the progeny of a given cell division can acquire different developmental fates."

"We're trying to find out why the progeny of a given cell division can acquire different developmental fates."

This statement comes from Leonard, one of three in this wonderfully odd and oddly wonderful novel about a love triangle (of sorts).

Leonard's concern about "developmental fates" comes about half-way through the tale. Leonard goes on to chat about pheromones, haploid cells and asymmetry. It turns out there are two types of haploid cells, Leonard explains. Some are mother cells that can bud and create new cells and others are daughter cells that can't.

There are a "million possible reasons for this asymmetry," Leonard explains. And he is determined to identify what it is.

Just as Leonard Bankhead is studying yeast cells (and watching haploid cells elongate prior to mating—yes, elongate) so is Jeffrey Eugenides pouring through the fine-grain, microscopic detail of the great love novels and turning them inside out, probing for the precise reason why they work.

The Marriage Plot, in fact, works. (Yes, I liked his other two books better, Middlesex and The Virgin Suicides, but here also Eugenides' effortless imagination is on full display.)

The Marriage Plot plays with literature, toys with story arcs (and almost tells you it's doing so) and teases with heaps of literary references. There's not quite the author-voice intrusion of, say, John Fowles in French Lieutenant's Woman but you can almost sense Euginedes turning to the camera and saying, "now, watch this."

These are three full-blown people: Madeline Hanna, Leonard Bankhead and Mitchell Grammaticus. They interact, overlap, influence each other's lives. They push and pull, repel and attract, elongate and shrink back. The bulk of the action here takes place in 1982—such an in-between year, a transition point. The list of topics touched in The Marriage Plot would be a long one but start with depression, motherhood, traditions, religion, rites, love, lust, desire, marriage (duh), Big Medicine and fiction and its role in our lives.

Euginedes stitches these three characters' lives together and then watches the threads strain, fray and snap. The structure of the book is a treat—seeing the same scene from multiple perspectives, gaining insights with each new telling. The ending is near magic, down to the final few words. It's a final confirmation, in case there was any question, that we readers are happily manipulated creatures.

We follow these three in various combinations from Rhode Island to Cape Cod, Paris, Calcutta and back. (For me, the Calcutta seems started to drag and Euginedes pushed the envelope of believability.) The story simultaneously circles the globe and caves in on itself and we see three individuals crash back toward each other, electrons orbiting the same atom and unable to pull themselves away. There's a whole world out there, a "million possible reasons" for why these people are the way they are. You can look all you want, Euginedes seems to be saying, and sometimes people are just the way they are—willing to go to another party and hope for a chance encounter with love.

At the end, I had the feeling that college graduation day is almost a permanent state of being for these three—its own bizarre form of peculiar and permanent purgatory. Euginedes lets us watch these three try on new skins, test out new wings and try to find new ways to fly.

Key word: try.

Filed under: Books

December 19, 2011

Paul Doiron – "Trespasser"

Paul Doiron warned us in "The Poacher's Son" that Maine game warden Mike Bowditch is not a happy camper. We learned in the debut mystery that sadness is a "perpetual condition" for Bowditch.

Paul Doiron warned us in "The Poacher's Son" that Maine game warden Mike Bowditch is not a happy camper. We learned in the debut mystery that sadness is a "perpetual condition" for Bowditch.

Bowditch doesn't de-gloom in "Trespasser."

He's still a brooder. There's a "gnawing uncertainty" to his world. He hasn't quite settled into his place in town, his place in the community, in his relationship, his workplace. With himself. He's prone to impulsive decisions and knocking back a few whiskeys to drown his sorrows. He's going through counseling and he's visited with a psychologist. He ignores good advice, goes his own way. He adores his school teacher girlfriend but doesn't treat her well.

Throughout "Trespasser," I wanted to slip him some happy pills and give him a lesson in how to lighten up. But he understands his job: "Ultimately, my job wasn't about animals at all. It was about people—and the cruelties they will commit when no one is watching."

Anytime you have a non-cop protagonist around a murder investigation, the trick is how do you keep the non-ahead of the cops? How can he outwit the work of the official investigators and figure things out before they do? And keep the plot credible?

Not only does Bowditch discover several bodies in the course of "Trespasser," he's right there at key moments to debrief the right people and glean key bits of information. A bit too convenient? Maybe.

Much of "Trespasser" revolves around a years-old murder investigation and this allows Bowditch to dive back through an old case—with few looking over his shoulder—and look for similarities and conflicts with the central crime that propels the story along. Bowditch plunges through 1,334 pages of the trial transcript of the old case and picks up a trail of inconsistencies and then goes back to the scene where the earlier "culprit" was apprehended only to find….okay, no need to put in a spoiler alert alarm.

It turns out the years-old crime has a passionate cult of followers who believe the wrong guy is in prison. This troupe includes some surprising characters who play a critical role in keeping Bowditch on track and fired-up, making for some good twists at the end.

I assume the "Trespasser" is Bowditch, working in the cop's world and showing them a thing or two. Doiron does a good job of giving Bowditch an edge and a reason to be a few steps ahead of the official investigation. I just wish I felt more compelled to get in his corner and root for his cause. Bowditch is chased by demons and I stopped caring, after awhile, because he didn't seem like he wanted to help himself.

Next time out, I wouldn't mind if Bowditch found a way to dump the dark clouds and just bear down on human cruelties, no brooding involved.

Filed under: Books

December 10, 2011

Craig Johnson – "Junkyard Dogs"

Some books nail the character so well you can't get enough. It's the mood. You know precisely the sensations author will produce. Visceral sensations. It's like returning to your favorite cabin in the woods. If you put the reading the chair in just the right place, the sunshine on the back porch will hit you just so.

Some books nail the character so well you can't get enough. It's the mood. You know precisely the sensations author will produce. Visceral sensations. It's like returning to your favorite cabin in the woods. If you put the reading the chair in just the right place, the sunshine on the back porch will hit you just so.

I enjoyed Craig Johnson's "Hell Is Empty" so much I had to back up a step to "Junkyard Dogs." I was not disappointed.

"Junkyard Dogs" is a smile waiting to happen.

Walt Longmire is a quintessential combo pack of love and cynicism, toughness and tenderness. Walt is bewildered yet doesn't judge. He views his crew with head-scratching pleasure and mild amusement. He's a sheriff with a real-world understanding of the endless variety of human beings that could run through his life and run through Absaroka County and, well, ruin his day. He doesn't really want to change anything or anybody, just keep order.

The world Johnson has created seems only marginally impacted by civilization's alleged progress. The cars are old, the town is, um, well-preserved. What's on the menu at the Busy Bee Café won't cause sleeplessness for Tom Colicchio. The crime-solving methods don't need CSI. Walt Longmire is as cool as Clint Eastwood in an old spaghetti western but more prone to apply brainpower than yank out his .45.

Longmire keeps his world view to himself, treats his staff as equals and marvels at their peculiarities. Enjoys their peculiarities. They are human beings and he's one, too. I could quote a few lines here or a few lines there, but the Walt Longmire experience emerges over time in the welcoming space that exists between Walt and his town—the doctors, the dimwits, the bartenders, the lowlifes and animals too. We learn Longmire's view of the world through the slow accumulation of brisk, punchy observations and the way he engages the world. Johnson is right there with Tony Hillerman. Like Hillerman, there is mystery but the suspense-fear-factor needle is well below the speed limit. In my mind, this makes for readability.

(OK, I'll quote a couple of lines.)

A chapter starter:

"It was a two-gallon Styrofoam cooler—one of the cheap ones that you can pick up at any service station in the summer season and then listen to it squeak to the point of homicidal dementia."

"The sarcasm in his reply was wader deep."

"There was a five-inch layer of snow on the swings that silently shifted in the slight wind, and I tried to think of something more depressing than empty playgrounds in the middle of winter but couldn't come up with anything."

"Junkyard Dogs" involves developers, "a little 4-H project" and mutts of all kinds, human and canine. Some are "wagging companions," some snarl. Running undercurrents involve Sheriff Longmire's physical ailments (especially of the ocular variety) and a low-simmering dispute with the foul-mouthed Vic, Longmire's deputy and source of "smoldering attraction that had bloomed into a stoked furnace," over buying real estate. Johnson weaves in sub-plots with subtlety and effortlessness.

Take a spin in Absaroka County. You're going to want to hunker down and hang out.

Filed under: Books

December 4, 2011

Taylor Stevens – "The Informationist"

"Blazingly brilliant." – Publisher's Weekly

"Blazingly brilliant." – Publisher's Weekly

"A thriller of the highest caliber." - Colin Harrison

"Utterly smashing debut." – Tess Gerritsen

"Could have used a rewrite." – me.

The hype. The hype. I'm sure I read "The Informationist" with the hype rattling around in the back of my head. And several times while reading it I thought about starting a new pledge form. A simple on-line seal-of-approval pledge form that would guarantee to the innocent reading public that the reviewer or blurb writer had read every word of the book. Every word.

Publisher's Weekly went onto to call it "The Informationist" a "high-octane page turner."

Maybe you're turning the pages so fast you don't read the details?

I don't mean to be so negative—and certainly the set-up of "The Informationist" holds plenty of appeal. An unusual setting, an international search for a missing teenager, intrigue about those who are bankrolling the hunt. "The Informationist" features Vanessa "Michael" Munroe and she is one-note angry.

"The Informationist" is strong on action—with many slower parts interspersed. I may not know what constitutes a "high-octane" restaurant scene. "The conversation had already been interrupted several times by the attentive waitstaff, and it took a longer pause with the arrival of the main course. The discussion strayed from small talk to the similar aspects of their work to small talk again…"

I never felt grounded in the world of Vanessa "Michael" Munroe. I was told lots of "information" about Munroe, never understood her talents. I was told lots of information about what motivates her, never felt connected to her seething anger.

And when she Munroe gets angry, the men in her way better get out of the way. It's in the action scenes where I wished—hoped—for plausibility.

"She struck like a mamba. Deadly. Silent. Fast. Without a sound the keys tore through the man's neck, replacing his trachea with a gaping hole." Without a sound?

"She gritted her teeth, yanked her right thumb out of its socket, squeezed the hand free of the restraint, and then relocated the thumb with a silent, painful snap." Isn't a "snap" (by definition?) a sound? How can it be silent?

A few moments later, she is thrown overboard with a boat anchor wrapped around her legs. (This not a small boat.) "The plunge stopped ten yards below the boat, and still the anchor held tight around her left ankle. Her lungs ached for air, and in panic she clawed at the chain. No time. Think. She forced her fingers between her foot and the chain, bought an inch, and then was free. She kicked off the ocean floor…."

I have such a hard time picturing the action. She "bought an inch?" She was ten yards below the boat but suddenly on the ocean floor? (These kinds of passages wouldn't fly at the fiction-writing critique groups I've attended.)

The head-scratching moments add up. And the bigger plot wends and weaves and meanders and you have to go along with Munroe's ability to cross international borders, speak a zillion languages and anticipate every violent moment that's just around corner.

"The Informationist" is fluffy and light, not built for thinking or word-by-word reading.

Questions:

Who wants to take the pledge?

Any suggestions for "high-octane" thrillers where the action-sequence details are perfect?

Filed under: Books

November 25, 2011

Glen Duncan – "The Last Werewolf"

Literary rejection fuels the heart of The Last Werewolf. No, not the heart of the grizzled old seen-it-all anti-hero Jake Marlowe. Literary rejection, it turns out, motivated Glen Duncan as he let this gripping story pour out.

Literary rejection fuels the heart of The Last Werewolf. No, not the heart of the grizzled old seen-it-all anti-hero Jake Marlowe. Literary rejection, it turns out, motivated Glen Duncan as he let this gripping story pour out.

Duncan was in a "foul mood," he said in an interview. He had written seven "overtly literary novels that had been read by virtually no one." And his agent let him know that his chance of finding a publisher for an eighth were "nil."

Yes, literary rejection.

I really had to laugh when I came across that interview with Duncan and think I better understood the seething, slow-burn feeling. Grrrr.

In the same interview, Duncan acknowledges that the "filmic antecedent" for The Last Werewolf is "An American Werewolf in London" with its similar mix of "horror, humour, sex, gore, pathos, moral quandary and believable love story."

That just about covers it, though Duncan of course doesn't tout his ability to marry a precise character with a powerful voice. As a reader devouring (sorry) The Last Werewolf, you are suddenly on the helpless end of a tractor beam.

The violence and sex are graphic. The descriptions are blunt in an unflashy way but also consistent with Jake Marlowe's view of the world. This is the way Jake views his whole odd life. He's jaded Jake, seen-it-all Jake, getting-tired-of-it-the-monthly-werewolf-thing Jake. He'd just as soon have another glass of old Macallan and a Camel Filter. Ending it all might be one option but he finds a reason to keep going. But they are coming after him, to wipe out the last werewolf so action here is Jake trying to stay one step ahead of his pursuers and trying to decide when to turn around and take them on. Or not. He's tired, he's turning 201 years old soon and he's prone to depression.

Because Jake is so grounded in human emotions, I felt completely connected with this particular werewolf's world-weary woes. He's wary of many things, particularly vampires, and this gives Duncan a chance to continue to stir the pot with wry tidbits about how life for this particular werewolf is going down. "This has been of the great vampiric contentions, that they constitute a civilization: They have art, culture, division of labour, political and legal systems. There's no lycanthropic parallel." But Marlowe has an explanation to cut werewolves some slack. "After a few transformations your human self starts to lose interest in books. Reading begins to give you a blood-brown headache. People describe you as laconic. Getting the sentences out feels like a giant impure labour. I've heard tell of howlers going decades barely uttering a word."

But for Jake, language is morality and his girl-du-jour Jacqueline helps Jake see that his "real curse" is that he can't stop caring about real beauty.

As he corners victims and stampedes women, we are shown his likable, smart and terribly analytic side, too. It's a delectable combination.

The plot rocks along–with leisurely intermissions here and there as Jake contemplates his situation or lies in bed with a woman. But it's the writing and imagery that kept me going. Snow falls with the "implacability of an Old Testament plague." Daybreak comes on like the "slow development of a daguerreotype." He gazes out on his city and "London goes about its business like a virile degenerate old man."

A compelling story told in a powerful voice, pumped up by a writer who ran smack into a brutal marketplace where his straight literary fiction had lost favor. (A sequel, however, is in the works…)

Filed under: Books

November 15, 2011

Fred Haefele – "Extremophilia"

The brief essay "Slime and Transfiguration" offers a perfect metaphor for the 16 other slices of Montana life that Fred Haefele offers up in "Extremophilia."

The brief essay "Slime and Transfiguration" offers a perfect metaphor for the 16 other slices of Montana life that Fred Haefele offers up in "Extremophilia."

The focus of "Slime…" is the now highly toxic Lake Berkeley.

"On its best day," writes Haefele, "Lake Berkeley looks more like an impact crater on the back side of Uranus. The steep walls that encircle it are a chthonic, sulfurous hue. Its waters are implacable, calm and dark."

(Before we continue: how much do you like that word 'chthonic'? I had to look it up. From the Greek. "Pertaining to the Earth; earthy subterranean. Designates or pertains to deities or spirits of the underworld.")

Lake Berkeley is "a kind of Mojito of heavy metals," writes Haefele. "A monument to the towering indifference of the mining industry."

It's here that Haefele finds biochemist Andrea Stierle and organic chemist (and husband) Don Stierle. They have studied the vile substance that industry has left behind in the "lake." In the water samples, they have discovered nearly fifty "odds-defying organisms" that are thriving in the slime. "Some are fungal, some bacterial."

They are extremophiles.

The Stierles find beneficial elements in the stew of organisms. (I'm going to encourage you to read this tight little series of essays to find out what they are.) And it's here that Haefele finds a telling contradiction. He asks: "What are the odds that the very place that nearly drowned in its own poisons would generate the source of its own redemption?"

"Extremophilia" is a series of love letters, in a way, to the Montana landscape that offers up the kind of rugged landscape and fewer-rules-than-most society that allow Haefele and the others he writes about to carve their own identities and mark their own territory with a rich flair for non-conformity.

"Extremophilia" is brilliant. It's tight, bright, frequently hilarious and treats readers as if time is precious. The book measures 145 pages (including introduction) and leaves a trail of dust. You want more.

By the way, one of the longer accounts here is "The Lost Tribe of Indian" about Haefele's affection for the products of the Indian Motorcycle Company. If you are hungry for more about this particular breed of motorcyles, there is Haefele's earlier "Rebuilding The Indian" to explore.

Aall the other pieces are brisk snapshots and Haefele interweaves his own life and his own career, if that's the right word. You get to know Haefele and his family but this is hardly a memoir. They are other characters in the landscape.

A kiss in a dangerous swimming hole. Felling timber. Fighting fires. Montana's role as a Petri dish for writers. Paddling whitewater. Deer hunting. Evel Knieval's curious funeral. And a flashback to Ken Kesey and a memorable moment in time that takes Haefele back to Stanford University in 1964.

It all connects, it all works.

The writing is razor-sharp, the scenes are relentlessly colorful.

"Extremeophilia" finds Haefele discovering the creatures that thrive in Montana—against all odds.

(By the way, if you want to have some fun, do a Google Image search for "extremophilia" and then stand back.)

Filed under: Books

November 13, 2011

Philip Connors – "Fire Season"

"The Fire Season" is a flashpoint for comments, observations, mini-essays and background on life and wilderness in the American West.

"The Fire Season" is a flashpoint for comments, observations, mini-essays and background on life and wilderness in the American West.

It's ostensibly a "life as a fire lookout" tale but stop for a second and think: how long (or interesting) a book could that be unless flames repeatedly lapped and licked at the base of the tower? Yes, "The Fire Season" has a few moments of fire-related excitement, including one nasty lightning storm, but for the most part Philip Connors follows trails of breadcrumbs off in dozens of different directions. He's a smoke watcher, not a fire fighter.

I'm not saying it's not interesting or worthwhile, but readers should be cautioned that some of the material will be familiar if you've read Timothy Egan's The Big Burn or, say, Edward Abbey's Desert Solitaire. There's a long section on Aldo Leopold and another on Jack Kerouac and another long and charming diversion about Connors and how he met his wife.

It's clear Connors is a big fan of the writers who have gone before him and he does a good job downloading their spirit and explaining the tricky balance between humans and the vast, delicate western landscape. He has particular wrath for the cattle ranchers and the deals they manage to strike with government authorities to allow for grazing. "Yet given the power and persistence of the cattlemen's lobby, they continue to graze on the public domain, tramping riparian areas, hastening erosion, pulverizing wildlife habitat, disturbing the fire regimen, and generally wreaking havoc on the land wherever they can." Connors laments the impact of cattlemen's "mercenary hired guns" and their impact on the grizzly bear and the gray wolf and he attacks the construction of the North Star Road, built in part to improve access for deer hunters.

If you took away these issues, "The Fire Season" might be enough for a magazine essay because the "glue" of the book is calm and reflective. Connors has a good eye for detail (any smoke spotter probably does) and, in those sections that he turns over to his nature journal, a clear style. "The wind dies, bees hover outside the open tower windows, the cinquefoil blooms butter yellow in the meadow. Clark's nutcrackers flutter their black and white wings as they move from tree to tree. Lenticular clouds dot the highest peaks, their elliptical shapes and striated edges bringing news of howling winds a few thousand feet above me."

You will feel what it's like to be alone. You will feel what it's like to watch hour after hour for a faint wisp of smoke. You will learn about the western wilderness and the ongoing effort to protect the wilderness. And you will realize that if you're going to be alone for a very long time, you better have something to think about.

Filed under: Books