Mark Stevens's Blog, page 52

March 30, 2012

Mark Coggins – "The Big Wake-Up"

March 17, 2012

Håkan Nesser – "Borkmann's Point"

March 11, 2012

There is No Point in Reviewing Lee Child

March 4, 2012

Terry Greene Sterling – "Illegal: Life and Death in Arizona's Immigration War Zone"

February 26, 2012

David Benioff – "City of Thieves"

February 12, 2012

John Galligan – "The Clinch Knot"

"I am the Dog now. I am a trout hound. I fish, I drive, I fish, I drive, I fish. I follow my nose. Not to wax poetic about it, but I dig holes. I scratch myself. I howl at the moon, and I know where I will go to die. I am also, for the record, a pretty decent fly fisherman."

"I am the Dog now. I am a trout hound. I fish, I drive, I fish, I drive, I fish. I follow my nose. Not to wax poetic about it, but I dig holes. I scratch myself. I howl at the moon, and I know where I will go to die. I am also, for the record, a pretty decent fly fisherman."

Ned Oglivie (a.k.a. the Dog) may claim that he doesn't "wax poetic" about things, but John Galligan takes care of business.

The Clinch Knot (my first Galligan, won't be my last) is packed with nifty imagery, sure-handed prose. The poetry is sly and understated. Galligan's style is quick and clean, pixilated dots of color and images as the story revs up and gets going.

The Dog is through-and-through a trout bum. But Galligan hardly romanticizes the Dog's life. There is an underlying bleakness and obvious squalor here, right down to Oglivie's favorite sipping beverage, vodka and Tang, and his favorite smokes, Swisher Sweets. The Dog's home is a Cruise Master RV. He is both at home and a long way from it.

However, the Dog is also open to friends and friendships and in Livingston, Montana—where he yearns to fish the Yellowstone River—he befriends a young black man named D'Ontario Sneed and his new squeeze, a white girl named Jesse Ringer. They give him a lift.

"I have come to care for them. Sneed and Jesse, and this state of sentimentality, I have lost focus and momentum. I am stuck and all too close to happy. And lately, I mis-read water. I miss takes. I fish the wrong flies, too distracted or too lazy to change. My loop collapses in the thinnest of breezes and I wrap line, daily, around my own dizzy head."

In fact, the Dog is confused by his own brief foray into happiness but, well, it doesn't last. Jesse is found dead and D'Ontario is found unconscious nearby. It's up to the Dog, as reluctant a sleuth as you'll come across, to pursue his own trail and theories, avoiding and sparring with the local law enforcement as he goes.

The start of The Clinch Knot is as sharp and finely drawn as a good mystery comes, but then in walks Aretha Sneed.

At that moment, for me, The Clinch Knot clicks up to a whole other level where a mystery becomes so much more, underpinned with questions about animals, humanity, life and death—all without being pushy about it. When Aretha enters the Dog's life, I found myself slowing way down on the page to watch these two interact. Pure joy.

Aretha is D'Ontario's mother and the Dog meets her on his way out of the town jail; she's just posted his bail. "In the reception area, waiting for me with unconcealed irritation, was a handsome black woman, thirty-five maybe, tallish and sturdy, dressed in tight jeans and a polo shirt that exploded pink-pink-pink off the dark brown of her skin."

Aretha Sneed is a firefighter with a fascination with the television western Bonanza. (Turns out she's partial to Hoss.) She has reinvented her life, too, and has been through a wringer that's different than the Dog's but still a wringer.

Galligan can pack as much information into dialogue as Elmore Leonard and these two both spar in a crackling, feisty manner. Their float trip presents myriad opportunities to bond and chat and analyze and Galligan milks them all beautifully.

The Clinch Knot involves white supremacists and there's a terrific environmental story at the heart of the plot that goes right to the issues of Big Wealth in the New West: fences, open ranges, water rights. A full array of quirky locals add flair to the scenery.

But at the emotional heart of this story is the teamwork of the Dog and Aretha. Their bonds reminded me of Galligan's description of a granny knot, held together "as some knots will, by sheer luck, and by copious looping and winding and threading and cinching."

The Clinch Knot requires the Dog to know fly fishing knots (duh) but the key to untangling the mystery is the Dog's ability to make utterly human connections—and trust his instincts. The Clinch Knot ties things up (sorry, couldn't help myself) beautifully. The last few paragraphs are utterly human, touching gems of prose and power.

Filed under: Books

February 1, 2012

Q & A With Ted Conover – "The Routes of Man"

I don't re-read books very often, but this time it was an easy decision. I had devoured the hardcover edition of The Routes of Man when it was first published (review here) and enjoyed it—immensely.

I don't re-read books very often, but this time it was an easy decision. I had devoured the hardcover edition of The Routes of Man when it was first published (review here) and enjoyed it—immensely.

When I found out Dick Hill had narrated the audio version of Ted Conover's latest book, I had to hear it. I listen to audio books frequently (okay, all the time) and enjoy Lee Child as much as anyone. I couldn't quite imagine the voice from so many taut Jack Reacher tales also taking me through the cultural immersions that comprise Routes.

But Hill's readings are crisp, precise and energetic and he quickly drew me into Ted's travels again like I was reading it for the first time. And there's some real-life tension in many of these pages that would give Jack Reacher pause – the unpredictable Area Boys in Lagos, Nigeria; the brittle ice road in Ladakh, India; hanging on for dear life along the "rules, what rules?" highway with the Beijing Target Auto Club at warp speed.

The Routes of Man is equal parts gripping, insightful and colorful and Conover's effortless style is made for story-telling. He has such an eye for detail and puts himself into such challenging and diverse situations that it's hard not to feel like you're along for the ride.

Ted is a friend (it's true) but I had three specific questions for him when I finished Dick Hill's narration of The Routes of Man.

If this isn't enough to whet your appetite, a few more thoughts follow this exchange:

Question: I'm fascinated by how you managed to keep such detailed notes on your travels – on riverboats in Peru, in cars going hair-raising speeds in China, in crammed danfos in Lagos, Nigeria. Can you describe your note-taking process? Were there were times when you were hesitant to conspicuously take notes (say, at a checkpoint in Jerusalem) and decided to rely on memory later?

Ted: The thing is, most of these experiences are so memorable, so different from my life at home, that they remain vivid in my mind even today. But I do take notes, all the time, to make sure I don't forget the telling details. Unlike with Newjack, these researches were not undercover, so I was free to write down most anything, at anytime. During the day this usually meant jotting in a small spiral notebook that fits in a back pocket. (I've posted a picture of some of my notebooks from The Routes of Man on this page.) But that's just the first step. Most days would end with me taking out my laptop and not simply transcribing those jottings but expanding on them. So in other words, I use the paper notebooks for writing down key details I might otherwise forget (e.g., names, jokes, numbers); then I use a laptop to elaborate on the larger picture and fill it in with subtler things I might be at risk of forgetting a week or month hence. The laptop is an important piece–I type a lot faster than I can write, for one thing. For another, typed notes are searchable, and easy to duplicate. On the road, whenever possible, I'd email notes files to myself so that I'd still have them if the laptop was stolen or the little notebooks were lost.

Question: When did the "good Samaritan" concept and its relationship to roads and travelling occur to you? Was that an idea you had before setting off on the reporting, or something that came later? Did you think ahead of your reporting that there is a "moral implication" to roads?

Ted: I'm glad you asked this — nobody has before. I had absolutely considered the moral dimensions of roads before setting off to do research. They are probably the aspect of roads that interests me more than any other. But the Samaritan angle didn't occur to me until the day I went to Nablus with the Israeli Defence Forces and the captain took me through a nearby village that he said belonged to "the Samaritans." At first I assumed he was speaking metaphorically–good people live here. But then I understood that he was speaking literally. These were the same Samaritans as the ones in the New Testament, their descendants a distinct group in that complicated hodgepodge that is the Holy Land. They have Judaic roots, but in their present incarnation they speak Arabic. Anyway, meeting Samaritans got me thinking about the parable of the Good Samaritan in the Bible. That's when it occurred to me that the parable took place on a road, and that roads are often the place where people decide how they're going to act toward strangers.

Question: In the chapter "The Road is Very Unfair," you return to Kenya and Tanzania and catch up with individuals you had met and written about previously. You point out that you made an effort to stay in touch with Obadiah Okello over the years since you first there in the early 1990's. Have you had any comments or feedback from any of the people in the other locations in this book since "The Routes of Man" came out? Have you stayed in touch with any others from Peru, Israel, India or China?

Ted: … or Denver?  I just tend to keep in touch with people. My Christmas card list is pretty long. The people I've met constitute, in many ways, my life; when possible, I'd rather keep connections alive. Anyway, to answer your question, yes, I'm in touch with people from all of those places. Li Lu, my translator in China, just had her first baby. Awni al-Khatib is now president of Hebron University. Dorjey Gyalpo in Zanskar finally received a copy of Routes last summer (sent through various intermediaries) and emailed me about it (again through an intermediary) last fall.

I just tend to keep in touch with people. My Christmas card list is pretty long. The people I've met constitute, in many ways, my life; when possible, I'd rather keep connections alive. Anyway, to answer your question, yes, I'm in touch with people from all of those places. Li Lu, my translator in China, just had her first baby. Awni al-Khatib is now president of Hebron University. Dorjey Gyalpo in Zanskar finally received a copy of Routes last summer (sent through various intermediaries) and emailed me about it (again through an intermediary) last fall.

The Internet makes all of this easier, of course. One of the great things about a personal website is that people I've met can use it to get back in touch. A couple of years ago I got an email from Tiberio Rivera, whom I traveled with in Coyotes. He was in Mission, Texas, visiting a cousin; he sent along a photo of his teenaged son. I live for this stuff.

+++

That "I live for this stuff" pervades every moment of the travels in The Routes of Man. Conover is an enthusiastic journalistic / anthropologist and that oozes through on every page.

On the surface, of course, it's not the Routes or the roads that fascinate Conover or make this book so compelling, it's the people he meets and the way their worlds are being changed by the new or being-altered infrastructure.

It's the people who form relationships and roads—routes—both expand our ability to get somewhere, to connect and also define who is not welcome, who is the stranger riding in from another land.

Read The Routes of Man for some terrific armchair travel and a stirring contemplation of what constitutes progress in this day and age in a variety of far-flung corners around the globe. The epilogue is a masterpiece all by itself.

What's the audio-version rave version of "I couldn't put it down" ?

I guess it's "I couldn't turn it off."

Filed under: Books

January 25, 2012

Colin Cotterill – "Slash and Burn"

Certainly Colin Cotterill's works prove (as if there's any doubt) that the "mystery" genre is a wide-open, anything-goes canvas.

Certainly Colin Cotterill's works prove (as if there's any doubt) that the "mystery" genre is a wide-open, anything-goes canvas.

Cotterill admits he wasn't writing "mysteries" or crime fiction or suspense or when he started out. He thought he was just writing "ripping yarns," as he told Publisher's Weekly.

A few pages into "Slash and Burn" or any of the Cotterill stories ("Slash and Burn" is only my second) and you'll realize you're into a whole new realm with all new rules.

Our "hero" is Dr. Siri Paiboun, a Loatian coroner who is pushing 80 years old. Not just a coroner, the country's coroner. And he doesn't exactly relish the role. He's feisty and irascible about just about everything, however, and that gives him the everyman quality that's easy to latch onto. (The stories are set in the late 1970's.)

Cotterill on how he developed the character: "I needed a character who was Lao, yet tainted by the West. As many Lao have done, Siri spent a great chunk of his life studying in Paris. He returned to his country with a pretty Lao nurse, a lot of Western ideas, and membership in the Communist Party. From then on, most of his life was spent fighting the French, the Americans, and the Lao royalists. By the time the wars were over, he was in his 70's and expecting to retire. But the old generals had something else lined up for him. He retains his Lao sense of humor, his staunch defense of Lao tradition, and his conviction that communism, in the hands of human beings, cannot possibly work. And as an elder statesman, he gets away with voicing such opinions." (Again, from the Publisher's Weekly interview.)

Dr. Siri is free to think or say anything—and he does. There is something loose and breezy in "Slash and Burn," a dollop of carefree, free-form fantasy with every page, thought, turn. Aiding and abetting this mood is the thousand-year-old Hmong shaman spirit who shares space with Dr. Siri. "I'm afraid we come as a set," he says.

Dr. Siri is pure attitude—still questioning authority with a youthful, feisty edge. He'd just as soon not play a Laotian version of charades as an ice-breaker. "For charades to be fun—if it ever truly was—you had to be three sheets to the wind, not hungover and stone cold sober at breakfast," he thinks. A few minutes later, he observes an American sergeant who leans into his walk "like a meatless Nebraska Man in a hurry to catch up with evolution."

Cotterill doesn't adhere anywhere close to the standard mystery arc. Wikipedia defines his stories as crime fiction stories and reviews refer to them as "whodunits," but the plot doesn't begin with clue-finding; it's more situational.

The writing is energetic and carefree. Cotterill says he writes each book, after he's done all his homework and research, in three or four weeks. (Yes, weeks.) The result is a rushing, breezy quality.

In "Slash and Burn," it takes quite awhile, however, for the gears of the plot to start grinding together. It's summer in Vientiane, Laos. Dr. Siri is chosen to go on a trip with a delegation from the United States in search of a downed American pilot. The "mystery" mounts as it's clear that something other than an unfortunate landing spot killed the downed pilot but even as events start to mean increased jeopardy for Dr. Siri, there are detours to make tea and deliver observations on marijuana as additive for food.

Don't be deceived by the "Slash and Burn" title. Yes, bullets fly at the end but the "slash and burn" here refers to villagers who burn off the top growth to prepare fields for planting, to allow the ash to fertilize the soil.

There are secrets, there are "mysteries," there is truth to be discovered. Just in a unique fashion with a unique, somewhat reluctant sleuth in an unusual setting. Call it a mystery or just call it a light, fun read. It's no wonder Dr. Siri has lasted so long.

Filed under: Books

January 15, 2012

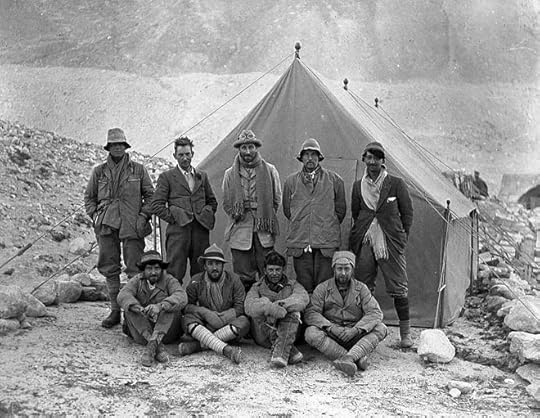

Wade Davis – "Into the Silence"

Big concept, big mountain, big danger and mountains—sorry—of detail.

Big concept, big mountain, big danger and mountains—sorry—of detail.

You feel every step in the long, cold, brutal climb up the "white fang" of Mt. Everest.

In fact, you feel every step as a nation sets its sights on a goal laden with "mystic patriotism."

"Into the Silence" is about the process of how Mt. Everest became a "distraction from the reality of the times" and how a nation embraced "a climbing expedition that would become the ultimate gesture of imperial redemption."

This is a terrific—and terrifically detailed—book about the first three attempts to climb Everest and the indefatigable and odd assortment of people behind them. But be forewarned that the mountain doesn't make an actual appearance in the telling of this conquest until page 236 of this 580-page epic.

Wade Davis spends many pages establishing the political and mental climate in the seven or eight years leading up to 1921. The first sections dive deep into the battlefield trenches in Europe as individuals emerge who will play a role in the Everest assaults. A nation's ability to embrace a challenge and steel itself to loss is a key theme.

So is the ability of the mountain climbers to evaluate risk and pursue goals. The "because it's there" comment from George Mallory, years after the war, almost makes sense when viewed through the weight and gravity and massive loss suffered.

In some ways, Davis is saying, the desire to climb Everest was part of a PR battle to restore the nation's confidence. It was spin from Propaganda Bureau. One information officer suggested that climbing Everest would help prevent the world from "slipping back into a dull materialism" and would serve as "vindication of the essential idealism of the human spirit."

Davis doesn't scrimp on detail anywhere on this journey.

The Great War. Thinking about Everest. Working through the politics and the culture clash of making the first treks into the Himalayas as the British quite literally brought their empire–and their champagne–with them.

It takes an army of porters and massive organizational effort to position the climbers and support them with provisions and, again, Davis treats these sections with as much care as he does the others. Every phase of the effort led to the next and every challenge came with risks.

You'll either relish in the fine-grain view or find it tedious. For me, I can't imagine the second half of "Into the Silence" without the first. The climbers come into view—like the mountain itself—with that much more relief. Davis invests considerable time in their background and personalities and the reward is a tremendous payoff when we're on the mountain making our way up.

Of course we know there is failure ahead but the early planners were supremely confident.

"In retrospect," writes Davis, "these were wildly ambitious, quixotic goals, revealing how little the climbers actually knew about the mountain, the scale of the endeavor, the danger of the undertaking, the power of Everest's wrath. They were like knights who had endured impossible hardships to reach the mouth of the dragon's cave, still to discover what it really means to enter and confront the creature."

The end is the most gripping as the climbers struggle with finding a route, learning what gear works or doesn't, and confronting issues over oxygen, weather patterns, wind and punishing, brutal conditions. It's in the last sections where George Mallory takes center stage and we follow him up and down the mountain through all three treks and, finally, his final climb followed by a thoughtful analysis of whether he reached the summit before perishing.

About the only thing that puzzled me was the odd title, "Into the Silence." It seemed a strange choice, an attempt to echo Jonathan Krakauer's masterpiece, "Into Thin Air." What silence? Certainly not the winds howling over the ridges of Everest.

About the only thing that puzzled me was the odd title, "Into the Silence." It seemed a strange choice, an attempt to echo Jonathan Krakauer's masterpiece, "Into Thin Air." What silence? Certainly not the winds howling over the ridges of Everest.

Aside from those three words, there are several hundred thousand others here that are fascinating and bring a faint story from history (at least to me) to life. I highly recommend the read and the ride.

Filed under: Books

January 7, 2012

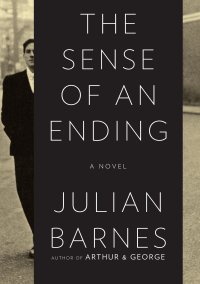

Julian Barnes – "The Sense of an Ending"

"History is a raw onion sandwich, sir."

"History is a raw onion sandwich, sir."

"For what reason?"

"It just repeats, sir. It burps."

And a moment later, a student states:

"History is that certainty produced at the point where the imperfections of memory meet the inadequacies of documentation."

Yes, well, that history thing will certainly return on one Anthony "Tony" Webster.

That certainty.

"The Sense of an Ending" is about putting together a story about your life, one that explains everything about the way things are today in your world. All the events and details and highlights and drama must fit that story, all other tidbits and non-conforming incidents jettisoned to the wayside, filed under "N" for non-conforming and, therefore, irrelevant.

But as far as the "inadequacies of documentation," there isn't much inadequate about what awaits Tony, a file from the aforementioned scrapheap and how it shatters his, well, narrative. The satisfying one.

What you need to know about Tony Webster is that he has a "certain instinct for self-preservation." Nonetheless, there are some issues to sort out.

"So when time delivered me all too quickly into middle age, and I began looking back over how my life had unfolded, and considering the paths untaken, those lulling, undermining what-ifs, I never found myself imagining—not even for worse, let alone for better—how things would have been with Veronica."

Ah, Veronica. Future source of "dim fantasies" and the spark in this story, the one whom Tony can't really forget. There's an early suicide and, later, an odd bequest that triggers events here. There is love, regret, jealousy, divorce, trust and time. There is also water—lots of water in the background here. Roman Polanski should make the movie.

This is a chiseled-in-granite, terse story that reminded me of Ian McEwan's last few – Saturday, Atonement and On Chesil Beach. Like those, The Sense of an Ending packs a wallop in novella fashion. The "voice" is serene and rock steady. The impact of events, unquestionable. The writing is beautiful. (And the ending is just a bit vague; Barnes does not switch to spoon-feeding here.)

And the mystery is delicious. Something is drawing Tony toward this information that will blow up in his face. We know it. Tony Webster may know it. There's an undertow, something tugging him back to check, back to Veronica, back to revisit key moments in the narrative and make sure all the threads are tightly woven, that the story works.

Yeah, I think you know. Not quite so fast, Tony, not quite so fast.

Filed under: Books