Steven Lyle Jordan's Blog, page 58

July 2, 2013

Babies expensive? Don’t have one. Duh.

A recent New York Times article has proven to be very popular among the news media: It outlines the high cost of having babies in the United States, more than twice as high as the cost in the next-costliest country (Switzerland—and three times the cost if you have a Caesarian as opposed to traditional birth).

A recent New York Times article has proven to be very popular among the news media: It outlines the high cost of having babies in the United States, more than twice as high as the cost in the next-costliest country (Switzerland—and three times the cost if you have a Caesarian as opposed to traditional birth).

Far be it from me to debate the costs of our medical system in this country. There’s no need. We all know how absolutely messed up it is, so I won’t get into it. What I will get into is the fact that, among all of the steps people are suggesting to deal with this issue, the one thing I don’t hear much of is the most obvious solution: Don’t have a kid.

No one seems to be too concerned about the fact that we are living on a spaceborne rock with fairly finite resources… and that there are already upwards of seven billion humans, and assorted other creatures, on it. But in the U.S., the ultimate Entitlement country, everyone believes it’s their right to have kids, no matter how ill-considered the notion may be. Let’s face it: Many couples essentially set their lives back years, by sacrificing the time and resources they have, however meager, to providing for a child soon after marriage. Some of them ruin their lives outright. Many families that cannot properly support their children create problem children, who can become problem adults. Financial problems create malnutrition, which impacts health well into adulthood, or lack of education, which often creates unemployed or criminal adults.

I’m not saying that these are absolute realities… but they happen. To a lot of people. Yet, somehow, most people don’t seriously consider any of this before they consider bringing a child into the world. At best, those who do simply decide that it won’t happen to them. I’m sure a lot of poor, disenfranchised, divorced and violent families assumed it wouldn’t happen to them.

Many people also still believe that their only hope for a future old age is to have children take care of them. In the past, yes, this was important… but today it’s not as vital of an issue as it once was. Intelligent and healthy adults can continue to be functional and vital well into old age, and right up to their deaths, especially if they’ve set up decent pensions or insurances for themselves. Old age without supportive children is no longer the early death sentence it used to be.

So, maybe the solution to the problem of expensive babies is: Don’t have any. I’m sure the planet won’t criticize you for not adding to the overpopulation problem. Or, at least, wait a while until prices come down… or you can better afford it. Exercise your right to live your own life, and consider your viable alternatives. Spend your money elsewhere. Put it in a savings account. Take a vacation. And bring condoms, just in case.

June 19, 2013

Audi’s E-bike concept: We should all want this

Audi’s beautiful e-bike concept may be what the future of bicycling—and, indeed, most non-highway single person transportation—ought to be aspiring to: It gets people out of cars they don’t need to be pushing and buying so much gas for; it is great for city and suburban use; it has built-in safety features; it still allows the rider to pedal if desired; but it also offers an electric motor that will take you at close to car-speeds wherever you need to go.

Audi’s beautiful e-bike concept may be what the future of bicycling—and, indeed, most non-highway single person transportation—ought to be aspiring to: It gets people out of cars they don’t need to be pushing and buying so much gas for; it is great for city and suburban use; it has built-in safety features; it still allows the rider to pedal if desired; but it also offers an electric motor that will take you at close to car-speeds wherever you need to go.

Take a good look at the bike (ignore the seat, for now) and you’ll see what I mean. The bike is made of carbon fiber frame, and even the spokes, giving it high strength and light weight, as well as looking incredibly cool (if you like grey, I guess… but I’ve heard of a great invention called “paint”…). The bike can accommodate a standard derailleur, giving the user multiple gearing options. The bike comes equipped with shocks front and rear, and even has built-in head and taillights for safety. Front and back tires sport hydraulic disk brakes, much more efficient when the roads get wet. This model was designed for Audi to show off, so it even includes a digital speedo, thumbprint-lock with anti-tamper alarm, and fob-enabled locking.

But most innovative here is the electric motor, placed at the low center of gravity, and designed to turn the rear wheel through the front pedal gear and allowing the rider to ride effortlessly. This is a prototype, so there’s no point in going through specs and figures here… but you can see lots of close-up shots of the bike at ElectricBike.com.

Again, this particular vehicle is a prototype. It is also designed for off-road and BMX-use, as opposed to suburban or city riding (which explains the pretty-much decoration-only seat). But that’s a matter of tweaking the design and layout of the bike… the components will stay largely the same. And mass production could bring the price down significantly (though those of us who experience sticker shock when looking at modern bikes today will probably not feel much better).

But whether or not this particular bike ever makes it to market, it can still serve as the template for a unique and much-needed new segment of transportation vehicle for the masses: The Portable Powered Vehicle. Though we like portable vehicles, especially bikes, many people don’t see many advantages to them in crowded urban areas, or when traveling long distances, or when the weather is not so accommodating (mainly, when too hot or too wet). Audi’s prototype demonstrates that many of those obstacles can be easily overcome, giving riders the option of riding a bike to places further away than they would normally consider, or allowing them to get there without being sweaty or smelly at the other end. They also satisfy the need of some to get to places quicker than a standard bike, even with multiple gears and Armstrong-rated legs to pump them, can get you. As those constitute a significant number of the reasons Americans give for not riding bikes more often, you can see the great potential in a vehicle that solves those problems.

Environmentally speaking, this is one of the best uses of power for transportation, given that it’s electric, sparing everyone from gas emissions, and that its significantly lower weight (even with a rider aboard) will allow an electric motor to power it more than adequately… vigorously, in fact. Electrics can be plug-in charged, which means less emissions per mile pumped into the air from the plant that supplies the power, and if that plug you just connected it to happens to be supplied by clean technology, you’re cutting back on even more emissions. And of course, there’s no reason why you can’t pedal yourself, giving you much-needed exercise, possibly running a generator that will recharge the battery, and saving on even more power use.

As these bike designs neatly coincide with research into better battery technology and the ever-constant effort to create more efficient motors, I expect to see many more Portable Personal Vehicles of this type appearing and giving us more and more alternatives to cars and trucks for everyday use. We could finally be getting a glimpse of the post-automobile world; a retro turnabout back to the improved simplicity of the lowly bicycle.

June 16, 2013

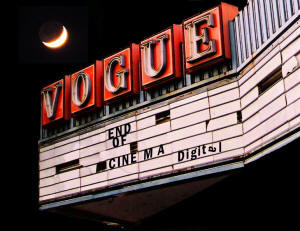

The movie blockbuster bubble

At the opening of a new building at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts in Los Angeles, Steven Spielberg was quoted as saying that the era of the movie blockbuster may soon be over:

At the opening of a new building at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts in Los Angeles, Steven Spielberg was quoted as saying that the era of the movie blockbuster may soon be over:

“There’s eventually going to be an implosion, or a big meltdown… where three or four or maybe even a half-dozen mega-budget movies are going to go crashing into the ground, and that’s going to change the paradigm.”

George Lucas—between he and Spielberg, producers of most of the biggest movie blockbusters in American history—agreed that the movie industry was due for a reversal of fortune, where the huge movies of the past will no longer carry the mega audiences they once did, and studios will be stricken by the sudden unprofitability of big movies. Both of them also lamented about the “lesser” movies they made, which almost weren’t accepted by the studios for theatre releases because of their non-blockbuster status. That’s right: Spielberg and Lucas both had trouble getting their movies into the theatres.

And what they are suggesting is that, at present, lesser movies are hard to produce for movies… but that in the near future, big blockbusters won’t get the automatic greenlight either. Does this mean Hollywood will have to turn back to the lesser movies, and a different profit expectation? If so, what should we expect?

In the past, Hollywood wouldn’t throw all its eggs in one basket; it would produce many movies at once, with carefully-trimmed budgets, throw them all out there, and hope they’d attract a large enough segment of the population to make profit for the studio. The odds were longer for any single movie to be a hit… but the studio’s odds to make profit were still pretty good, because of the number of flicks they produced.

This is in contrast to today’s films, which are fewer and less diverse than those of the past, designed to hit all the hot-buttons of their target audience—in other words, today’s movies don’t try to target just those comedy fans who like screwball comedies… they are designed (or marketed) to draw all of the comedy fans. But if a movie flops, you don’t just lose a segment of a genre’s fans… you lose all of them.

So it might seem that Hollywood would do well to go back to the “studio factory” system of knocking out movie after movie, and overwhelming us with choices… right?

Not so fast—because there’s a new aspect of movie selling that alters the old paradigm totally… home video. Once Hollywood had gained control of television stations to provide an in-home source for their entertainment, they began to develop to-buy versions of their products for home use. Studios have already discovered new audiences for old films that they couldn’t even get on television anymore, thanks to videotape, DVDs, On-Demand and rental services, and now, digital delivery. Movies that are deemed not good enough to make it in theatres are being produced direct-to-DVD, making them available to genre audiences and still bringing a profit to the studios.

So, if Hollywood can no longer make the big bucks on blockbusters, the most sensible thing for them to do is to evolve towards smaller and more direct-to-DVD productions, which can be more reliably targeted at lower cost. Those productions will likely see lower production values than their predecessors. Thank goodness those TV screens, tablet screens, cellphone screens, etc, are a lot more forgiving than movie screens.

But what about Hollywood’s life-long partner in crime, the movie theatre? Theatres these days see thinner and thinner profit margins, and practically live from blockbuster to blockbuster as they suffer through the lean times with special productions, renting out their spaces to meeting promoters and evangelists, and hosting birthday parties. And theatregoers are more likely these days to reconsider the cost of seeing a movie on the big screen, especially if it doesn’t take advantage of that big screen to present big, impressive cinematography and special effects, and opt to see it at home or on their portable devices when it becomes available. Without the big blockbuster, do those theatres stand a chance of surviving?

For most of them, the answer will unfortunately by “no,” or to be more specific, “not as theatres.” The end of the blockbuster will bring about the end of the theatre—or most of them, at any rate. While some will transform completely into meeting places for any groups willing to pay for the space, most will fade away.

This might turn out to be a good thing for live entertainment, however. A theatre space is well-suited for any number of things, like live theatre, music venues, presentations, clubs, theme restaurants, gyms… a multi-screen theatre could conceivably offer all of these things, and more. The old theatre could evolve into a multi-venue entertainment complex, offering something for almost everyone to enjoy. They could even reserve a room for showings of old blockbusters… if enough people will come to see them.

Though Spielberg and Lucas’ comments are not gospel, there is a strong likelihood that they are not wrong, and that Hollywood is on the way to its biggest change since they broke into television. That change may even involve finally leaving behind the big screen, a long-time-coming divorce that will be messy and painful… but mostly for them. There’s a good chance the public won’t bat an eye.

June 10, 2013

PRISM and public overreaction

The news of the past week has been filled with the revelation by an ex-CIA employee of the project called PRISM, in which the government has unfettered access to Americans’ phone calls, emails, Facebook messages, etc, in order to catch threats to national security.

The news of the past week has been filled with the revelation by an ex-CIA employee of the project called PRISM, in which the government has unfettered access to Americans’ phone calls, emails, Facebook messages, etc, in order to catch threats to national security.

As I suggested in a previous post, Americans have short memories. Even this close to the Boston Marathon bombing, after which we were treated to the sight of the Tsarnevs killed or captured by police and federal authorities, to the standing ovations of Boston citizens… those same citizens now cry “Big Brother!” and cite privacy issues in our government’s monitoring our communications.

The two things that strike me as the most significant here are: The idea that the government is somehow actually monitoring all of these calls, emails and messages; and the fact that PRISM didn’t just start yesterday. In terms of the former, people seem to think there’s someone actually sitting in a government desk and reading and/or listening to all of this stuff. Nothing could be further from the truth. Instead, computers search for key words, phrases and combinations of traffic that suggest plots against Americans, and pass any suspicious data to a few reviewers to process. In order to directly, physically monitor all of those calls, emails and messages, the government would have to hire so many people that it could single-handedly wipe out unemployment. Globally.

And to address the latter, PRISM was launched in 2007. PRISM has been credited by authorities as having provided information that has prevented incidents, for instance, the plot to blow up backpacks in the New York subway system in 2009… just as it was designed to do. And I’d be willing to bet that if the subway bombing had happened, New Yorkers would have no trouble okaying any efforts the government and law enforcement agencies would have to use to catch the people responsible and bring them to justice.

Despite these facts, much of the American public is critical of PRISM and the idea that it is “spying” on American citizens. Memories are indeed short.

So, for Americans that are debating the question of “privacy vs security” right now, I’d like to say:

Don’t overreact. PRISM is designed to catch terrorists, not tax cheaters or speeders. Relax.

If PRISM saves a single human life (and, oh yeah, it has), it is worth every cent.

This does not make the government over-reaching; it makes them proactive and protective.

Remember Boston.

Remember 9/11.

Remember Columbine.

Remember Newtown.

Remember Virginia Tech.

Remember Aurora.

June 5, 2013

Pleasuring myself

Over the years, I’ve been concentrating so much on entertaining others that I’ve slipped in my efforts to entertain myself; and right now, I have a yen to improve my life by re-immersing myself in the many forms of entertainment media I’ve collected over the years. But because of their formatting and my need to upgrade my collection, that will require digitization. (Don’t ask. It’s all my stuff, reformatted for me alone. No copyright infringement here. Move along.)

Over the years, I’ve been concentrating so much on entertaining others that I’ve slipped in my efforts to entertain myself; and right now, I have a yen to improve my life by re-immersing myself in the many forms of entertainment media I’ve collected over the years. But because of their formatting and my need to upgrade my collection, that will require digitization. (Don’t ask. It’s all my stuff, reformatted for me alone. No copyright infringement here. Move along.)

I have totally embraced digital storage, backup and delivery of my media content: It is much more efficient than filling rooms with reams of paper and vinyl that are difficult to consume in any quantity anywhere else but in that room. I want my collection of media to be capable of traveling with me… all of it. All the time. I haven’t bought a new printed book in years, and precious few CDs… which I have quickly converted into MP3s soon after purchase. It’s time for the rest of my collection to get the same treatment, and become the totally portable source of pleasure that it yearns to be.

Foremost is my music collection, a great deal of which is jazz from the 50s and 60s that I inherited from my Dad (when he decided not to take them to his retirement in Florida). I’ve got a ton of albums, some of which I still haven’t even listened to, and all of which needs to be turned into digital files. I used to hook up my laptop to the stereo system and use third-party software to digitize the songs, one by one; but the software I used is dated, and the setup needs improvement as well. I’ll probably buy a turntable that has a USB output, so I can go directly to computer with it, and update my editing software to make it easier to break an album side into multiple cuts, massage them to get out artifacts, adjust fades, etc. Once I’m done, I may never have to buy an old song again. Well, I probably will… I don’t have everything. But I won’t need much!

Next will be my novels. I’ve still got novels on shelves and in boxes, many of which were my favorites, but which I haven’t touched in awhile due to switching to an almost totally digital reading habit. So I need to start digitizing my existing novels (and probably throwing out any that I discover I don’t want to digitize). That will free up a lot of space on the shelves, which, these days, are beginning to compete with my growing DVD collection.

Novel digitization is tricky, because it’s so easy for available software to do a bad job translating physical text to digital files, wrongly translating letters and entire words, screwing up punctuation and spacing, etc. Each book really needs a proofing pass to catch those anomalies, so it takes a lot more personal effort to digitize a book. But with a significant amount of the books I have, the effort will be well worth it.

There are a few devices that are designed to ease the novel digitization process, mostly using multiple cameras or mirrors and special mounts to hold the books… some can be assembled yourself, if you’re a decent builder. (I may have to buy.) I could also use my flatbed scanner, though that can be incredibly slow and involve more steps to digitization. With all the stuff I have, I’m probably better off spending on the new equipment and making my life easier.

And finally, there are my many graphic novels. The good news is, you don’t need to do any proofing of a digital image file. The bad news is, you still have to scan each page separately… and I have a LOT of GNs. They also take up a lot of digital space at good resolutions, so I may find myself buying a dedicated hard drive just to hold them. But again, if it means I spend more time enjoying all of that choice content… it’s well worth it.

Don’t think I haven’t considered that some of this material has already been digitized by someone out there, and that it’s just a matter of getting online and downloading copies of many of these books and albums. Personally, I prefer not to do that; I consider that as part of the reason I have been unsuccessful as a new writer. So I will resist the temptation as much as I am able, and do the work myself.

So at least I don’t have to worry about being bored as I bring my writing sideline to a close. I’ll get back to enjoying the reams of fantastic content I’ve enjoyed over the years, most of which is better than anything I was ever able to produce. And after all, literature and art aren’t worth a damn if someone isn’t actually enjoying them. Right?

May 30, 2013

What is Star Trek… really?

The recent release of Star Trek Into Darkness has stirred up a lot of debate in the fanspace: Its action-packed but not particularly intelligent script is being challenged as to whether or not it adheres to the “spirit of Star Trek,” and therefore whether it should be considered a good movie vehicle. Other movies have been pulled up to compare it to, including Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan, a movie deserving of the exact same scrutiny as Into Darkness.

The recent release of Star Trek Into Darkness has stirred up a lot of debate in the fanspace: Its action-packed but not particularly intelligent script is being challenged as to whether or not it adheres to the “spirit of Star Trek,” and therefore whether it should be considered a good movie vehicle. Other movies have been pulled up to compare it to, including Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan, a movie deserving of the exact same scrutiny as Into Darkness.

But base to all of this debate is the fundamental question that needs to be addressed: What is Star Trek, exactly? We can’t reliably say whether or not the movies are or are not Trek without coming to a full understanding of what Trek is.

(Note: This commentary will restrict itself to the Star Trek movie and television productions, as there is simply too much in other media to be intelligently included here.)

In the mid-1960s, TV producer Gene Roddenberry conceived of a new science-fiction-based television show to present to the networks. He sold it to them as “Wagon Train to the stars,” an allusion to a popular western TV show about a group of people who traveled from place to place and had interesting and exciting adventures. (Even today, the best way to sell a new TV show is to compare it to another successful TV show… “CSI in Seattle”… “Survivor in space”… “Galactica across the Alps”… etc. TV execs get that.)

He got an okay to produce a pilot, into which he tried to introduce a galaxy-spanning starship (part of a military police force, ala Forbidden Planet) and some (at the time) groundbreaking concepts, like a cool, logical woman in second-of-command, an alien crewmember that wasn’t there for horror or comic relief, and a fairly integrated and liberated crew. His pilot episode featured science-fiction-standby elements like advanced aliens, mind-control, humans caged like animals in a zoo… then went them one better, by presenting a compassionate and sympathetic reason for the aliens’ actions, depicting them in the end as not evil at all.

The execs didn’t like the pilot. “Too cerebral,” they said. They wouldn’t buy a female executive officer… because she was female, or because she was cool and logical… take your pick. And the alien crewmember looked “devilish.” No sale.

So Roddenberry did another pilot. This time, the female exec was replaced by the alien crewmember, who was now presented as the cool and logical one. Most of the other lead characters were replaced, and the new storyline involved an officer who is zapped by a strange energy field and becomes a powerful threat to the crew, and whom the Captain must dispatch in an epic battle of yelling, energy blasts and phaser-fire.

The execs went for that. Star Trek had its green light for production.

Although Roddenberry was mindful of the TV heads’ disdain for “cerebral” material, he was also a smart writer, and mindful of the period he found himself working in. The 1960s was a unique era in television, wherein shows were taking advantage of the medium to explore other, more controversial subjects in the news at the time: Race and gender equality; political ideologies; war and morality; American values; environmental issues. Westerns, anthologies and historical dramas had begun to tell these stories, hidden behind the trappings of genre. Roddenberry hoped to do the same.

With his guidance, Star Trek became one of the best known and most successful TV series to explore those controversial subjects, and break new ground regarding characters and their roles and relationships, as well as delving into subjects hitherto only seen between the pages of serious science fiction novels, exploring concepts like human psychology, intolerance and prejudice, might and right, morals and psychology, pain and loss… the very the definitions of humanity and our efforts to be the best species we could be. Its original tagline—To boldly go where no Man has gone before—referred to the exploration (and improvement) of the human condition as much as the exploration of the galaxy. And to this day, the original Star Trek series is still lauded as the most shining example of such television.

Not that Star Trek was perfect: Besides its legendary budgetary constraints, it found itself warring with censors on a regular basis. Stories often lost much of their flair by the time they reached the small screen, and the shortcuts that had to be taken to depict a high-minded concept often came out trite, even outright laughable. And Trek still often resorted to good old-fashioned fisticuffs and battles to win the day, proving that American might always makes right in the end. As much as Star Trek was lauded for its high morality, so was its star, William Shatner, regularly lampooned for his melodramatic dialog and torn-shirt-flying-kick “cowboy diplomacy.” Cowboy diplomacy notwithstanding, Trek was always held up to a high moral standard that few shows could be said to match.

Unfortunately for Star Trek, the audience that valued such material was never as large as the audience that liked sitcoms, action and more familiar genres like Westerns and War. Trek only managed to get through three seasons before being cancelled. Though efforts were made to revive the show, Paramount showed no real interest in the project… until a little movie called Star Wars broke box office records worldwide, and Paramount wondered how they could get in on the good thing that 20th Century Fox had unexpectedly tapped into.

You can almost hear the echoes bouncing through the corridors of history: “Hey, check it out… we have a sci-fi thing too! It was called Star Trek.” “Sounds like the same thing as Star Wars… good deal! Get this into the pipeline, stat!” “stat… stat… stat…“

And so began Paramount’s revival of the Star Trek franchise, first in the theatres, then back on television. But Paramount was seeking a different audience for the movies… a Star Wars audience. And Trek was not a Star Wars vehicle, as the release of Star Trek: The Motion Picture clearly illustrated. Movie audiences generally panned their attempt to explore “higher states of being” and allegorical Creators as so much snooze-fest. So Paramount brought in directors and producers who knew nothing about Star Trek… but knew how to make action movies with big scores and cool special effects. Instead of stories that hit on iconic Trek elements, they went with attacking Trek icons… especially the starship Enterprise, which eventually became the most-repeatedly-destroyed ship ever in a science fiction franchise. The next Star Trek movie, The Wrath of Khan, squarely hit the buttons Paramount was aiming at, and won over moviegoers who hadn’t even seen the original episode from which the movie was based; as far as the studio was concerned, this was the formula for Star Trek movies forever more.

Khan had little in common with what had always been the intent of the original Star Trek series… or even the original Khan episode, Space Seed. Problem was, no one at Paramount, and precious few moviegoers, cared.

With the success of the movies came more television series, The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager and Enterprise; which, in general, made a more concerted effort to be more faithful to the original intent of Star Trek. Unfortunately, television is controlled by ratings more than ever before, and the new Trek series found themselves struggling to maintain audience share. Though they were buoyed by movie and general franchise popularity, the TV series found themselves resorting to heavily action-oriented plots—generally season-spanning wars between the Federation and one of the many other empires or races they encountered over the years—and elements designed for titillation (something the original Trek series was also not unfamiliar with, but which had been generally used as background elements; in later series, sexy main cast members designed as eye-candy became featured foreground elements).

The wars and eye-candy made the shows very popular, as the movies featuring the same morals-free action and effects-laden conflicts continued to win box-office… which, depending on your point of view, was either great or galling. For Paramount, a company devoted above all to making money off of media entertainment, there was no question how they felt. And as the clear majority of TV watchers and moviegoers were right behind them, they had no reason to doubt their direction.

But in the midst of all this, the original intent of Star Trek has been loudly bulldozed over by the profitability of flashy mediocrity. And with J.J. Abrams’ reboot of the movies in 2009 and 2013, Star Trek‘s morality, philosophy and ideology has been completely obscured by profit-inducing sleight-of-hand: The misdirection of a young cast aping established character archetypes; and the blinding effect of lens flare.

If Q, the nigh-omnipotent pan-dimensional being introduced in The Next Generation series, were able to see what had become of the franchise known as Star Trek, from its ground-breaking beginnings to its common-denominator-pandering present, he would be reduced to tears of laughter at our expense, guffawing at the high-minded humans who finally, by their own hand, proved themselves to be no more than ground-scratching apes after all.

And in the case of Star Trek, he wouldn’t be wrong.

May 27, 2013

The lysine contingency

In Jurassic Park, when it looked like the park was about to go tits-up with rampaging loose dinosaurs, Mr. Hammond asked his game warden: “Mr. Muldoon, would you please prepare the lysine contingency?” That was the plan that would starve the dinos of lysine, a genetically-engineered requirement to be delivered through their food, thereby killing them off, and saving everyone’s necks.

In Jurassic Park, when it looked like the park was about to go tits-up with rampaging loose dinosaurs, Mr. Hammond asked his game warden: “Mr. Muldoon, would you please prepare the lysine contingency?” That was the plan that would starve the dinos of lysine, a genetically-engineered requirement to be delivered through their food, thereby killing them off, and saving everyone’s necks.

Well, if my novel-writing sideline doesn’t work out, it will be time for a lysine contingency of my own. (Oh, don’t worry… there’s always the second island.) I’ll be weaning myself off of the writing and promotional part of my life, which has proven over ten years to be a complete failure, and moving on to something new (probably something that doesn’t depend on pleasing other people).

The trick, of course, is to totally abandon the novels, the web sites, the Facebook pages and Twitter feeds, the pages on independent author sites, the Amazon and Barnes & Noble pages… and the constant fretting about how to promote all that. I’ll have to decide whether or not to leave the novels available online, or to take them all down and never put them back. It’s been a never-ending part of my thought-stream for the past decade, so you might think it would be impossible to forget all that.

But I have a secret to tell you: More than a decade ago, I was putting all of my efforts into being an illustrator. I wanted to work in commercial art, and sideline in graphic novels of my own design. Unfortunately for me, my art skills peaked way too soon… and way before they were good enough to support a career. And I had to accept that. It took me a while, but one day I managed to ditch the tools, take down the art I’d created, throw away most of it, and put myself upon a new path that didn’t include illustration.

And it looks like I may have to do it again.

To be sure, it’s frustrating and even embarrassing to have to admit to myself, and to the world, that I’m not good enough to hack it as a writer. Or maybe I’m fine as a writer, but not good enough a promoter… whatever. It comes out the same, either way: If I can’t sell my books, it’s time to own up to my own mediocrity and go.

But I won’t be going out with my tail between my legs. Maybe I failed as a writer. Who cares? Ultimately, nobody. Statistically, less than .00000001% of the population of this planet even knew I existed, which means less than .00000001% of this planet even knows I failed. Actually, it’s even less than that, as a significant part of that .00000001% doesn’t even know I write novels. So no big, right?

If you think about it, it becomes nearly as insignificant if I’d succeeded as a writer. Not much larger than that .00000001% would notice or care… perhaps .0000001%. Perhaps .000001%. A hundred-thousandth of a percent of the population. My “success” would statistically not mean a damned thing.

You see, this is what my lysine does for me: It starves me of my hubris. It reminds me how small and insignificant I am in the scheme of things, and therefore how small and insignificant is my failure. It puts things into proper perspective, and reduces me to a single atom in a candy bar… a single cell somewhere in a human body. It keeps me from losing any sleep over this, as it assures me that no one else is losing any sleep over me.

At this moment, Balticon is winding down to a close. The 2000 promotional cards I seeded at the convention have so far not created even a noticeable spike of hits on my web site, and no sales of the book. So I’m looking at a symbolic representation of my desire to forget the last decade ever happened, my lysine contingency, and go back to my idyllically-clueless life of entertaining myself for a change.

Looks like a little blue pill. How appropriate.

May 23, 2013

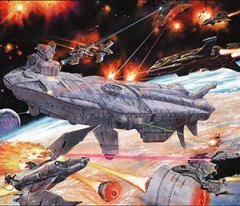

SF has cycled back to the “Star Wars” era. Again.

Science fiction, like many other things, enjoys cycles. In SF’s case, those cycles usually involve the relative popularity of science itself: Exploring physics and extrapolating on reality, to discover or speculate more about ourselves and the universe we live in. When the science part of SF is up, we get novels by scientist-authors like Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov; we get movies like 2001: A Space Obyssey, The Andromeda Strain and Soylent Green; we get TV series like Star Trek.

Science fiction, like many other things, enjoys cycles. In SF’s case, those cycles usually involve the relative popularity of science itself: Exploring physics and extrapolating on reality, to discover or speculate more about ourselves and the universe we live in. When the science part of SF is up, we get novels by scientist-authors like Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov; we get movies like 2001: A Space Obyssey, The Andromeda Strain and Soylent Green; we get TV series like Star Trek.

When science is down, we get space battles. We see an abandonment of concepts like science and physics, in exchange for showy action and eye-candy. We get movies like Star Wars and TV shows like Battlestar Galactica, and we see video games that are devoted to first-person shooters. More cerebral content, like the movie Solaris or the TV series Caprica, quickly get dumped in favor of The Fifth Element, Aliens or Warehouse 13.

We even see science-embracing shows, like Star Trek, rebooted as science-ignorant shows.

I was discussing one of my novels with a relative last year, and she interrupted me to ask me when I would be turning my book into a game. “What?” I asked. “All the kids play video games,” she said. “You need to turn it into a video game, and you’ll do great.” But my book (Verdant Pioneers, for the record) was about people in deep space, prospecting for minerals and supplies to keep themselves alive… not attacking killer aliens and shooting at armed robots, as the most popular games run. I wouldn’t have made a dime.

A recent article on IO9.com brings the message home in discussions about the latest Star Trek movie, Into darkness. The movie is science-free, the script is not particularly great, and the actors are mostly caricatures of their 1960s counterparts… but the movie has insane effects, explosions and action, so who cares? Apparently not most SF fans. Into Darkness is also compared to The Wrath of Khan, another science-free, battle-heavy Star Trek movie which fans seem to lionize as the best Trek ever. In both cases, science is relegated to irrelevance, and that’s apparently just fine… even for a franchise that prided itself upon so much more when it debuted almost 50 years ago.

Pundits like to look for blame for these trends. Supposed “authorities” will say that the public is getting “burned out” by science’s impact on our lives—by constant global communications, security threats, hackers, drones, phishing, self-drive cars, IEDs, Google, nanobots, global warming, iPods, etc, etc—and that the public yearns for a simpler, understandable, familiar world. A world with no future-shock. A world in which a problem is clear-cut, and can be eliminated by a good old-fashioned fist or a better marksman when necessary.

Others blame the educational system and media for downplaying science and its importance in our lives. Industries encourage future workers to accept the status quo and avoid rational questioning, so science in schools is downplayed and ignored. Without a proper grounding in science, people don’t know that there are questions to ask, much less why such questions would be important. Science is not more than the toys that surround us, and they’ll get better on their own—ultimately we will defeat nature—so why think about it?

Either way, listening to other comments on SF-based sites, watching the box-office reports, and noting the books that get the maximum discussion and recommendation, seem to make it clear: Science Fiction is on the low end of the science cycle right now. SF fans right now don’t want to think about reality or consider the real properties and possibilities of physics; they just want to lose themselves in fantasy and power nostalgia, to see cool stuff and blow s#!t up.

This is especially disheartening to me, because I write SF stories that are much heavier in science than in explosions. I prefer stories about intelligent people who think their way out of a problem, rather than future super-soldiers who shoot their way through it. It might readily explain why my own books have not caught on in the marketplace, as they are not the type of SF that readers are currently looking for. In fact, I’m not sure how well I could write such a story; and if my livelihood depended on my being able to turn out sci-fi shoot-em-ups, I think I’d be in serious trouble.

But if this is the current phase of SF, so be it. These cycles come and go; and eventually, people will be more interested in exploration and discovery, and less in battle and explosions. And when they do swing back, I for one will be waiting with plenty of material to satisfy them.

Excerpt from Verdant Pioneers

In Verdant Pioneers, second in the Verdant series, the residents of the city-satellite Verdant—recently escaped from the environmental disaster caused by the eruption of the Yellowstone Caldera on Earth—are trying to make it on their own in deep space, seeking sources for supplies, and possibly even a habitable planet to resettle on if Earth proves unwilling or unable to allow them to return.

In Verdant Pioneers, second in the Verdant series, the residents of the city-satellite Verdant—recently escaped from the environmental disaster caused by the eruption of the Yellowstone Caldera on Earth—are trying to make it on their own in deep space, seeking sources for supplies, and possibly even a habitable planet to resettle on if Earth proves unwilling or unable to allow them to return.

In this excerpt, geologist Brooke Adams hurries to return to the freighter Makalu, on a prospecting mission near the Gliese system, with a find that she knows will astound her colleagues… and the world.

“Brooke, I need a sitrep.” Roy Grand paused over the com in the main bay, just forward of the shuttle bays. Most of the rest of the crew, including Bob and Arnold, but not including Val and Nick, were crowded around him, looking at each other nervously. “I have you as twenty minutes from hitting your emergency supply. Where are you?”

“I know,” came Brooke’s voice over the com, “and I’m coming as fast as I can! But this rock is very brittle, and I absolutely don’t want to break it! My ETA—” there was a significant pause at her end, before she finished, “—is close.”

Arnold tapped Roy on the shoulder. “I’ll suit up, in case she needs help.” With that, he pushed off for the shuttle bays.

Bob also floated nearby, saying to no one in particular, “Why can’t she tell us what she found? If it’s so important that she couldn’t take a break, and we couldn’t go back out after our break—I mean, if it’s hazardous or something, why’s she bringing it in?”

“Hey,” Roy said, “You’ve been right here, just like me. I don’t know any more about it than you do.” He seemed to consider the question, though, and spoke into the com: “Brooke, can you confirm that whatever you’ve got isn’t hazardous?”

“It’s not hazardous,” Brooke responded instantly. “But, I repeat, you do not want me to break this!”

“I also don’t want you to asphyxiate!” Roy protested. “Best speed back in here, rock-hound! Leave the rock if you have to!”

“Not gonna happen, boss. Just hold the door for me!”

The crew exchanged glances again. Brooke had been as vague as she had been adamant that she would stay out and chisel away at the chunk of asteroid she’d found, beyond the point at which standard procedure demanded she come in for a midday break. She had also told Roy it was important to keep Bob and Arnold from going back out, but not why. Roy had reluctantly agreed, partially because of Brook’s reputation as one of Verdant’s best geologists, partially because she’d insisted she only needed an extra hour or so to finish, and partially because of the difficulty of sending Bob or Arnold back out in another monkey shuttle to assist her—the ungainly shuttles were more often too much of a hazard to each other to risk using in close quarters.

But when Brooke had exceeded her estimate by two additional hours, then started back so slowly that it threatened to drain her life support system before she could make it back, Roy had come to realize that they might pay dearly for his decision to let her stay and work.

“Captain.” Everybody turned to see Val floating into the bay, and allowing Calvin to catch her. “I scanned the asteroid fragment she’s got. It’s multiple layers of unremarkable ores, with trace readings of various elements, including complex carbons. Nothing radioactive, toxic or otherwise dangerous.” She shrugged. “I have no idea what the big deal is.”

“And she won’t tell us,” Roy muttered. “This had better be good.”

It was a painfully drawn-out twelve minutes later when Brooke’s com opened up. “I just switched to emergency air supply. I must have been more active than I thought… or more excited.”

“Brooke,” Roy said, “I want you to drop the rock and get in here. Arnie’ll retrieve it once you’re clear—”

“No! I’m taking it straight to cargo!” Brooke replied. “Once it’s down, I’ll hop off the shuttle, and you pressurize the bay.”

Roy’s jaw clenched and shifted… he was clearly unhappy about the suggestion. But eventually, he switched to the intercom. “Arnie, when you’re suited up, get to cargo. Brooke’ll drop off the rock and get out of the shuttle, you’ll help her in, then you bring in the shuttle. Understand?”

“Got it.”

Roy nodded at Bob. “Cargo.” The both of them pushed off and headed for the main cargo section, the others getting out of their way, then following behind them. When they reached the cargo bay hatch, Bob activated the monitor screens as Roy glanced inside through the inner hatch port, to make sure the bay was ready.

“I see her,” Bob announced, and everyone looked at the monitor screen. In fact, what they saw was the edges of the monkey shuttle, the rest of it mostly obscured by the rock it was pushing along ahead of it. Brooke, between the rock and the shuttle, could not be seen at all. She was approaching the ship, but very slowly.

“Open the bay,” Roy ordered.

Bob pointed out, “It’s not fully depressurized—”

“Open,” Roy repeated, and without further protest, Bob triggered the outer hatch.

When the outer doors were open enough that Roy could see the shuttle and the rock through the inner hatch port, he swore. They seemed to be barely moving. Roy swung over to the com and slapped at it. “Christ almighty, woman, will you get your ass in here!”

“Shut up! I’m almost there!”

Roy’s nostrils flared, but he said nothing more.

Finally, they could see Brooke in the shuttle’s cockpit as she eased the asteroid into the bay. Momentarily, they saw Arnold drift into view, coming up beside Brooke as she guided the rock in. She continued to work slowly and deliberately, and driving Roy crazy as she ignored her low air reserves.

All at once, the rock was in place, the monkey shuttle began backing out of the bay, and they could see Brooke struggling out of the harness. When she was clear, Arnold gave her a push back into the bay, then began to strap himself into the shuttle.

As soon as Brooke was clear of the outer doors, Roy shouted, “Close hatch and emergency pressurize!” Bob worked the controls, while Roy watched through the hatch port, and the others looked on. Even now, when Brooke could have allowed herself to go limp and rest, she was busy collecting straps to secure the rock. “Relax! Leave it!” Roy shouted through the glass, but Brooke ignored him.

Finally, the green light over the door snapped on, and Roy wrested the hatch open and launched himself inside. Brooke saw him coming, and put out her arms as if making sure he wouldn’t collide with the asteroid fragment. Roy ignored her efforts, and grabbed at her helmet locks. In seconds, he had her helmet off; and as soon as it was clear, Brooke took a deep breath, and her eyes went wide. “Oh, my God! That air was going stale!”

“No shit,” Roy snapped as he tossed her helmet behind him. “Now, you better have a damned good reason for this, to keep me from grounding you for the rest of your life—”

“Yeah,” Bob said as he floated in behind everyone else. “What the hell’s so special about this rock?”

“Oh, it’s special, all right,” Brooke said, taking deep, cleansing breaths as she started to undo her suit. “But before I show you,” she went on as Roy began to help her out of the torso, “let’s wait until Arnold gets here. He deserves to see this, too.”

“See… what?” Calvin asked, staring at the rock in confusion.

Brooke smiled widely and replied, “Something beautiful.”

When Arnold had the monkey shuttle back in the bay, and the bay pressurized, the inner hatch opened, and Bob floated inside. Arnold had just taken off his helmet, and Bob practically wrestled him out of his suit. “She won’t show us anything until you’re there!” he explained as he helped Arnold shuck his gear. Then the two of them floated back to the cargo bay as fast as they could manage it.

By the time they got there, Nick had also arrived from the pilot’s station, making it the entire crew complement in the bay. As soon as Roy saw the other geologists arrive, he said to Brooke: “Now… give.”

Brooke had been standing by the asteroid, keeping everyone from touching it, but allowing them to look as closely as they wanted. So far, no one had noticed anything unusual about the rock. She had retrieved a flashlight from a toolbox, and she turned it on at that point. “Henri,” she addressed the engineer, who happened to be standing closest to the bay control panel, “would you kill the bay lights please?”

The engineer regarded her suspiciously, and Arnold said, “What is this, ghost stories?”

Brooke considered his words. “Interesting way of putting it,” she said, and nodded at Henri again. At Roy’s confirming nod, the engineer shut off the lights. At that moment, the flashlight was the only thing providing light to the bay, and Brooke held it up so that it illuminated her head from below her chin. “Ooooooooo,” she teased. Then, she started to move, floating above the asteroid.

“Yeah, I know it seems theatrical, but this is about the only way I can show you what I saw. I almost missed it, myself, when I cracked the asteroid open… I had to get just the right angle of light on it to see it in shadow.”

“Shadow?” Calvin repeated. “What are we talking about, an impression? I didn’t see anything.”

“Right,” Brooke nodded, as she moved close to the asteroid, peering down the edge of the upright face carefully. “That’s what I’m saying… it’s so shallow as to be almost invisible.” She began to cast the flashlight beam along the upright edge, trying different directions and angles. “Even now, when I know what I’m looking for, I can’t really see it. But at the right angle, it’ll come out…” She paused, looked at the rock, then at the others. “Tell you what: Why don’t you all float up to the top of the bay, there (she waved her flashlight in that direction), and wait for me to find it.”

The crew looked up at the ceiling foolishly for a moment, then at Roy. Roy simply shrugged, and pushed off for the ceiling. Moments later, so did the rest of them. And in the meantime, Brooke went back to work studying the asteroid.

“Once I saw it,” she continued as she played the flashlight about, “I wasn’t surprised at the composition of the rest of the asteroid. Its makeup suggests part of the crust of a planet, all right. Whoever guessed that it was probably blown out of its system by some major event, a collision or something, I think they were ri—aha. Gotcha.”

She looked upward at her audience. “Everybody ready?”

Roy held out his hands, and said, “Go ahead.”

Brooke turned back to the rock, shining the flashlight against one side, low enough that none of the light touched the upward edge. Slowly, she raised the light, allowing it to shine the barest amount of light across the edge, like a sunrise slowly illuminating a plain. At first, nothing happened… most of it was still in shadow. Then Brooke found the right glancing angle, which revealed the long, thin sliver of one shadow, with numerous shorter, thinner slivers fanning out from the long shadow in various directions.

It took about a second… then the crew gave out a simultaneous gasp of shock. There was no questioning, and no debate. What they could see, cast by Brooke’s flashlight beam in the dark of the cargo bay, was undoubtedly the thin but clear impression of a giant, fern-like leaf.

~

“I never thought I’d see this day,” Bob mused, with a wide, childlike smile across his face. “I mean, not in my lifetime did I think we’d ever find irrefutable signs of complex life on other planets.”

“Heck,” Arnold added, “I never thought we’d see it, period! I mean, even if there was life out there, I was sure we’d never, ever find any of it.”

“Why not?” Nick asked, pausing just before biting into a sandwich. “Did you think we’re not smart enough to get out there and find it?”

“It’s not that,” Brooke interjected, and she and Arnold shared knowing looks. Brooke had discussed matters like this with Arnold in the past, and knew his opinion on the subject. “It’s the likelihood that we’d manage to find signs of life, when it was around to be found. You see, the universe is billions of years old, and stars and planets have come and gone during that time. Some of them may have harbored life… and others may in the future. But sooner or later, those planets die, those stars go cold, and any life on them will die, too. That leaves a finite window in which to find that life… perhaps on the order of a few million years, out of billions.

“Now, Man has only been around for a few hundred thousand years, and has been searching for signs of life off Earth for only a few centuries. We’ve actually been out here for only a year. Chances are, we’re too late to discover millions of examples of life in the universe… and when we are no more, we will miss discovering millions more.”

“Right,” Arnold said, hooking a thumb in the direction of the cargo bay, and the asteroid. “We obviously missed discovering the planet where that life originated, perhaps by millions of years. That’s a piece of a dead planet in there… whatever shattered it like that would be classified an extinction-level event. Even if it managed to survive whatever did that to it, there’s little-to-no chance any life that was on it at the time survived.”

“Certainly no higher forms of life, at least,” Calvin added. “But plant life can be very hardy. There’s a good chance, I think, that there might still be similar vegetation on the remnant of that planet.” He looked significantly at the others. “If any of it is still there.”

Roy looked at Calvin. “Are you suggesting what I think you’re suggesting?”

Nick seemed to catch Calvin’s drift, and his eyes lit up. “We’ve got enough fuel and supplies to last us for at least two weeks, maybe three if we want to stay out.”

“And do what?” Roy asked. “Are you telling me you want to go find what’s left of that planet… of that star system? How are we supposed to do that?”

Calvin turned to Val, who thought about it a moment. “We may be able to reverse-compute the trajectory of the asteroid field, before it was captured by Gliese, and backtrack along those lines to see where it came from. Then we can translate along that course, to see what we can find.”

She looked to Nellie, who nodded in agreement. “True, there’s no reason we can’t. In fact, we can limit the number of exploratory translations further by sending the probe ahead to scout around. But what, exactly, do you hope to find?”

“Okay,” Brooke said, putting her hands out to virtually encompass her vision to them. “We follow the trail to see if we can find the planetary remnant. Maybe we’ll luck out and find signs of whatever life evolved there after the cataclysm. Earth had at least one extinction-level event, and we evolved from that. Who knows what we may find?”

“And even if we don’t find higher life,” Bob added, “and personally, I doubt we will, for the same reasons Brooke described—a planet that was fertile enough to grow plants on, even a remnant, must have been similar to Earth in makeup, and may provide a great many of the ores and elements we’ve been out here looking for. And a cataclysmic event may have turned it inside out, to the extent that many of the elements that are usually buried deep underground may be exposed to the surface, and easier to reach.”

Val and Arnold nodded. “I think,” Val said, looking at Roy, “that the last point is a good enough reason to go. It may be the best chance we have to find an Earth-like planet, and the elements Verdant needs to survive.”

“Still sounds like a crap-shoot to me,” Roy said. When the others started to protest, he held up his hand. “Hey, we’re talking about trying to back-trace an asteroid field, whose course may have been altered by a close pass to any celestial object… we don’t know how long it’s traveled, so we have no way of knowing how far to go… and we don’t know if there’s even a planet left where it came from! If someone here doesn’t think that’s a crap shoot… remind me to play craps with you sometime.”

If Roy expected to see understanding, agreeable faces… he didn’t get them. In fact, everyone in the crew deck looked back at him in silent disbelief. Roy looked at each of them in turn, and realized he didn’t have an ally in the entire group. Presently, he sighed. “Well… I suppose it wouldn’t kill us to try.”

“Yes!” Brooke shouted, and intentionally sent herself into a tight barrel roll of celebration. The others also cheered and danced in the micro-gravity, until Roy put out his hands for attention.

“Need I remind you,” he said, “that the decision isn’t mine to make? We have to get an authorization from CnC, or we’re not going anywhere.” Everyone got quiet at that, a few of them visibly upset at the possibility that they might not get the chance to go. Brooke seemed most upset of all, and considering it had been her discovery and her suggestion to follow the back-trail, that was very understandable. Roy took note of that, too, as he considered their next move.

“Obviously, the thing we do next is to notify Verdant, include a recording of our findings, and ask for instructions. We’ll also include the ship’s recordings of this conversation, so CnC knows our thinking on this.” Roy turned to the scientists of the group. “Brooke, better arrange for an image to send back with the probe… that should help sell them on it.”

Brooke smiled. “So… you want to go, too?”

Roy shrugged. “How could I not? Hey, I’d love to go down in history as Captain of the first Earth vessel to find life on another planet!” He suddenly leveled a finger at Brooke. “Which means you’d better find it, young lady, or incur my wrath!” He waved at them all. “Now, get going! Get your image, and collect your data! Nellie, prepare the probe to return to Verdant.”

As the scientists floated off, Roy called Nick and the engineers together. “Boys, let’s confirm our operating capacity, so we know how long we can stay out. We’re including that in the probe’s recording. Go!”

~

“Ceo, I have a signal… it’s from an unscheduled probe.”

Julian and Reya, who had been conferring in the corner, turned when they heard the communications tech’s announcement. Julian frowned, and asked, “Whose probe is it, Pani?”

The girl at communications checked her board, and replied, “It’s the Makalu, sir. The probe…” She paused, as she listened to her monitor and studied her readouts. “They’re sending two messages, sir… one is standard voice, the other looks like a lot of data.”

“Data?” Reya repeated. She looked at Julian. “Did they find something?”

Before Julian could respond, Pani advised them, “The probe just translated back, after it finished transmitting.”

Julian nodded at Pani, then looked at Reya. “Only one way to find out,” he said finally. “Pani, play the voice message.” The tech worked over her board, and CnC went quiet as everyone listened to the message on the room speakers.

“Verdant, this is Captain Grand on the Makalu. We’ve made a significant find here, and require instruction as to how to proceed. I won’t go into details here, but our findings, and a recording of our own conversations about it, are included with the probe transmission. Please go over the material, and send a response by probe when you’re ready. We will hold station until then. Our suggestion is to review the image data first. We think you’ll be… impressed. Makalu, out.”

Pani confirmed, “That’s all of the voice transmission, sir.”

“All right,” Julian said. “Send the data recordings to the center console, please.”

“Yessir.”

Julian and Reya moved to the center console, and Julian called up the data files on the control board. He found the image files, and opened them in the display column.

Upon seeing the very first image, his jaw went slack. Reya’s mouth also fell open, and around them, those who immediately saw the image in the column gasped in shock. CnC went completely silent as everyone who hadn’t looked at first, responded to everyone else’s reactions and looked up, too.

Reya was the first to speak. “Qué va. Qué-mother-fucking-va.”

~

“Probe is back, Captain,” Nellie advised Roy.

“Okay,” Roy nodded, and turned to everyone else. “Regardless of their decision, we won’t be going anywhere right away… except maybe back to Verdant, I suppose. So, as of now, field work is done for today. Rock-hounds, go and get your gear properly stowed. Then, we knock off for the day.”

As Brooke, Arnold and Bob floated off, Calvin turned to Roy. “Captain, if Verdant tells us to come back, would you really do it?”

“Yes, I would,” Roy said, and gave him a stern look. “We’re out here to do a job, at Verdant’s suffrage… they are our home base. You don’t do anything to tick off home base. If they decide that someone else can do the job better—or that no one should do the job at all—that’s their decision to make, and we’ll abide by it.” He placed a hand on Calvin’s shoulder. “Besides, we’ve already made history just by being here and finding this. I’m not greedy.”

Calvin nodded thoughtfully, and headed off. Roy watched him go, then decided to help the scientists stow their equipment, especially Brooke, who had been forced to abandon her monkey shuttle, and her suit, on unusually short notice, after pushing them to their limits. He pushed off for the shuttle bay, where he expected to find Brooke at work.

He came upon her before he got there. She was hovering in place on the side of the corridor, in the approaching-fetal-position that was common for people at rest in microgravity. She didn’t seem to notice he’d come up behind her, or she was paying no attention to him, so he reached out and touched her shoulder. “Brooke?”

Brooke turned and looked at Roy, and he clearly saw a smear of wetness on her cheek. He knew it for what it was: Tears had no place to “run” in microgravity, and usually built up until they were wiped away. “What’s wrong?”

Brooke smiled bravely and wiped at her face again. “I was just thinking: I wish Anise had been here to see this… to share this with me.”

“She’ll find out soon enough,” Roy told her softly.

Verdant Pioneers is available at my website, at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

May 21, 2013

Making novels feel real

I recently heard from a reader who wanted me to know how much he’d enjoyed how my stories had drawn him into the narrative. He specified Verdant Pioneers, and described a scene where one of the female characters is reunited with a beau that appeared in Verdant Skies. He described the moment with a series of words from the book, which I immediately recognized, and then lamented that not only did he strongly feel that moment, but he felt bad that he’d never felt such a powerful emotion directed at himself!

I recently heard from a reader who wanted me to know how much he’d enjoyed how my stories had drawn him into the narrative. He specified Verdant Pioneers, and described a scene where one of the female characters is reunited with a beau that appeared in Verdant Skies. He described the moment with a series of words from the book, which I immediately recognized, and then lamented that not only did he strongly feel that moment, but he felt bad that he’d never felt such a powerful emotion directed at himself!

(Yeah, join the club. We have T-shirts.)

I’m not writing about this to brag, but to point out the difference between different writing styles, and how they affect readers. Every so often I come across a book that features what I call “formal dialogue,” a lot of large words and melodramatic prose clearly written to impress the reader with the author’s thesauric prowess. Characters don’t talk; they speak, eloquently and demonstrably, as if delivering a soliloquy at every opportunity. And indeed, many readers love exactly that kind of writing; they say it transforms them to another level, to a heightened state or a super-reality that serves to draw them into a narrative like a star draws its planets to it.

On the other hand, there are those readers for whom expansive, flowery and demonstrative prose tends to leave them cold, in fact pushes them out of the narrative, distracting them like a bad smell in a restaurant. Some of those people react so because they may not be as familiar with words and sentences that they do not encounter “on the street”… though many more of them are very familiar with the words and sentences, but because they are not used “on the street,” they sound false and unreal. They do not sound natural to the ear, and the mental effort of “translating” flowery prose to natural language distracts the mind from the narrative.

I’ve always been of the “straight talk” variety of reader and writer. I prefer reading words that someone next to me might have used if I’d just asked him how to get to the corner store, or what just happened down the street where he worked. For me, natural, colloquial speech allows me to fully immerse myself in the story, and get the most out of a dramatic or emotional moment… as my reader did reading Verdant Pioneers.

In science fiction, colloquial speech can be vital to holding an audience. Sci-fi tends to be filled with exotic locations and concepts, scientific gadgetry and advanced engineering ideas… many readers have to struggle just to keep up with some sci-fi content. Add to that overly-demonstrative prose, and a reader can quickly get frustrated, lost, and disinterested in the book. Colloquial speech ensures that, whatever else you throw at your reader, they don’t have to wrestle with your words, too.

This, perhaps, is why I haven’t found myself able to fully enjoy any of the Steampunk novels I’ve so far tried. Most SP novelists write in some semblance of the formal, flowery and verbose Victorian era prose, a great deal of which was intentionally embellished by the writers of the day—who, it should be noted, were often paid by the word by their publishers—to the extent that today’s readers believe the haute Victorians actually spoke that way all the time, and not just during special meetings and occasions. But Victorians did not speak on a daily or regular basis in the sort of language and grammar that we find in the writings of the day, any more than we speak today in the same language and grammar we might read in today’s newspaper articles.

And though none of the words are unfamiliar to me, they still grate on my ears, distracting me to the extent that I am pulled, still sopping, from the narrative pool, and wishing I could fully immerse myself before the joy of the story was lost. Or, to put another way—my way—over-the-top prose spoils the moment, and I can’t fully get into the story.

Now, that’s just me. I don’t presume to tell someone which style is better, nor which they should prefer; it’s a matter of preference, and whatever works for you. Most importantly, the reader should enjoy the story. If they are most comfortable with demonstrative prose, great; if they prefer street talk, that’s great, too. If they are comfortable with both, so much the better.

But I’m glad that my writing, which tends to be in the colloquial voice, works for people who value that voice and enjoy my novels because of it.