Steven Lyle Jordan's Blog, page 37

November 11, 2014

THE rap battle of the century!

November 10, 2014

Futurist’s review: Interstellar

Interstellar, the Christopher Nolan movie (co-written by himself and Jonathan Nolan), is the sort of science fiction movie that comes along very seldom these days… unfortunately for all of us. In an entertainment market that will go out of its way to throw boy wizards, zombies and Klingons at ravenous audiences—but turn up its nose when someone offers real scientific content—Interstellar strives to hit some notes that are rarely touched by Hollywood anymore. But as those science notes are nested within some of the more well-known notes preferred by Pop Movie 101 aficionados, this movie does a great job hitting the right notes at the right times.

Interstellar, the Christopher Nolan movie (co-written by himself and Jonathan Nolan), is the sort of science fiction movie that comes along very seldom these days… unfortunately for all of us. In an entertainment market that will go out of its way to throw boy wizards, zombies and Klingons at ravenous audiences—but turn up its nose when someone offers real scientific content—Interstellar strives to hit some notes that are rarely touched by Hollywood anymore. But as those science notes are nested within some of the more well-known notes preferred by Pop Movie 101 aficionados, this movie does a great job hitting the right notes at the right times.

(Spoiler-free review follows)

The basic premise is pure Pop Movie 101: Apocalypse. Simply, the Earth is losing its ability to feed humans, so the remnants of NASA decide to look for a new home for humanity, thanks to a wormhole that mysteriously appeared near Saturn. Explorers have already gone through to explore the planets on the other side, and this new mission is to find out what happened to them. Though the trip out there could take months for our heroes, it could take decades for those on Earth, so it’s a serious sacrifice for ex-pilot Cooper to leave his family in order to lead the mission to another galaxy.

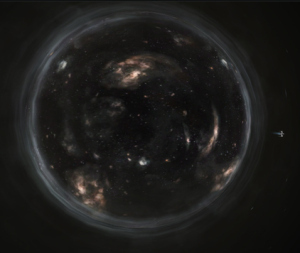

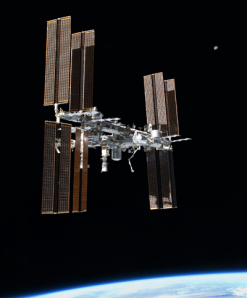

The Endurance orbits the wormhole in Interstellar.

Though much of the movie’s “action” tends to be more cerebral than physical, leading some to perceive it as slow in spots, in fact very little of this movie is wasted space. Elements of the movie are often introduced and, without a preamble or mini-exposition by a character explaining something to the audience, the story moves right along, forcing the audience to pretty much accept what they’re seeing and move right along with it.

And then, just when the lazier of the viewers are thinking about sneaking out for more popcorn, the movie will slap a very exciting physical moment in the middle of the drama, kicking everyone’s heart into gear and reeling them right back in.

Lest you think that this movie is all science and the occasional surprise, there is a wonderful side-story regarding the astronauts’ families back at home; not just whether they will see them again, but whether the astronauts’ efforts will actually help those at home, or leave them to die with a dying Earth. It is this side-story that ties everything together and hits the movie out of the park.

Here is where the Nolans shine: Taking what is essentially a simple premise, and crafting an excellent script, with strong and realistic characters, some interesting twists and turns, plenty of emotion and an incredible climax. Interstellar provides all of that in a very entertaining and satisfying story that left me thinking of Person of Interest, another Jonathan Nolan vehicle that wonderfully combines action with scientific conjecture and social examination.

The KipThorne-approved black hole in Interstellar. It’s design was rendered by the special effects crew based on Thorne’s calculations; and reputedly, when Thorne saw it, he said: “Yes, of course it would look like that!”

At this point, it’s worth mentioning that physicist Kip Thorne is the movie’s scientific advisor, and Nolan put him to excellent use working out the mechanics of wormholes, black holes and visiting other planets (the movie was given Neil deGrasse Tyson’s approval in this more spoiler-y article). The engineering is equally well-developed: The spacecraft look futuristic, but practical. Even the effectively non-anthropomorphic robot works, seeming very realistic while not projecting the usual kind of “man-in-a-suit” smoothness or “toy bot” cuteness that audiences are now fully acclimated to. At no point during the first two hours (yes, it’s a 2.5-hour flick) do you doubt the physics of anything seen in this movie; in this way, Interstellar is sure to be compared to movies like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Contact in bringing as realistic a scientific background to the screen as possible. (I wish I could add Gravity to that august list, but as its basic premise is based on much shakier physics, I’m sorry to say it doesn’t measure up here.)

I (and Tyson) were also glad to see that the main characters here are all scientists, engineers, astronauts, extending across generations. Like 2001, Contact and Gravity, Interstellar is a movie about nerds… and they handle themselves just fine, they don’t stutter or fret or step into the shadows when a heavily-muscled hero takes center stage. Those of us who feel like science, technology, engineering and mathematics are usually given short shrift in entertainment will be very happy to see them taking center stage here.

Though the bulk of Interstellar tends toward scientific accuracy, the climax is much less so, giving viewers a resolution that tends toward the “wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey” kind of sci-fi that fans of Doctor Who would appreciate. To be fair, though, the climax is centered around pure scientific speculation regarding space and time… and it’s not as if 2001 or Contact didn’t take a few liberties around theoretical physics for the sake of entertainment. Though the resolution is thoroughly Dues ex machina, it does serve to bring the audience to a much more satisfying ending (maybe even more logical than they expected to get).

Production-wise, the movie is nigh-meticulous. Parts of the movie were filmed in IMAX, and it shows, primarily in the space scenes. Most of the Earth-based scenes were not filmed in IMAX, and as the scenes often depict a gritty, dust-covered world, that’s just fine; but in a world that, it is suggested, is almost literally choking on dust, there were occasional scenes of beautiful sunny days, blue skies and a few wispy clouds, leaving the audience to wonder exactly how bad this Earth is supposed to be… because it often doesn’t look bad at all.

I saw Interstellar in an IMAX presentation; naturally, this meant the theater projectors felt it was their duty to shove the speaker volume up to 11 to fit this “big” movie. I was occasionally surprised to discover that the rumbling of a rocket engine or other similar sounds had my trouser legs vibrating. At times, the action or background score reached such a constant and unrelenting crescendo that people were leaving the theater for auditory preservation. (I’m old. I bring earplugs to movies now. Otherwise, I’d’ve left with the others.)

I could ask a question or two about the movie’s scientific elements… but of course, I’m no physicist (despite not being a Republican), and am in no position to tell Kip Thorne that he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. One thing I definitely wondered was: If this wormhole was “sent to humanity” by someone ostensibly helping us to find a new home, why did they need to put it all the way out by Saturn? Is there some reason it couldn’t have been a few weeks out beyond the Moon? But given the rest of the experience, I’m fully prepared to give that one a pass and move right along.

So, overall, I’d give Interstellar 5 stars, and I look forward to adding it to my DVD collection (I’ll take blu-ray, please) when it is available. If you like movies with plenty of scientific accuracy, check this one out. If you’re interested in more action, adventure and explosions… just sit tight, the next Star Wars movie is right around the corner.

November 9, 2014

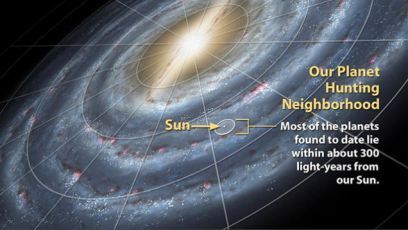

Go Interstellar? No—go Orbital

Interstellar opens in theaters this week. Its premise is that the Earth is becoming a global dustbowl, making it impossible to support the human race; so a band of astronauts heads out and through a wormhole to find another planet for human colonization. (I plan to do a review of the movie, soon.)

Interstellar opens in theaters this week. Its premise is that the Earth is becoming a global dustbowl, making it impossible to support the human race; so a band of astronauts heads out and through a wormhole to find another planet for human colonization. (I plan to do a review of the movie, soon.)

Would this be the best solution for human survival? Not necessarily. Physicists Gerard O’Neill and Tom Heppenheimer worked out a more practical solution four decades ago: Build artificial habitats and put them into orbit around the Earth or Sun. This idea was described in O’Neill’s book The High Frontier and Heppenheimer’s book Colonies in Space, and it’s the idea I used as the premise of my novel Verdant Skies.

Following O’Neill and Heppenheimer’s logic, I postulated a group of cities in Earth orbit, commissioned by the United Nations. The U.N. plan was to move most of the human race to the satellites, taking the immediate pressure of human life off of the planet. Earth would still be an immediate source of resources, but as life on the satellites would be more efficient in their use of resources, Earth would not be under as much pressure to support them. The intent would be to improve the state of the planet, severely restricting pollution and environmental damage, and restoring the planet to as close to a healthy and pristine condition as possible.

Following O’Neill and Heppenheimer’s logic, I postulated a group of cities in Earth orbit, commissioned by the United Nations. The U.N. plan was to move most of the human race to the satellites, taking the immediate pressure of human life off of the planet. Earth would still be an immediate source of resources, but as life on the satellites would be more efficient in their use of resources, Earth would not be under as much pressure to support them. The intent would be to improve the state of the planet, severely restricting pollution and environmental damage, and restoring the planet to as close to a healthy and pristine condition as possible.

Under this plan, a small population of workers on Earth (to limit their environmental impact) would handle the extraction and pre-processing of materials (including foods) that would be periodically sent to the satellites on ground-to-orbit transport rockets. The satellites would use Earth’s resources, but in a more efficient manner due to their enclosed ecosystem and need for efficiency. Resultant waste products from the satellites would be largely recycled and reused; that which could not be recycled could be jettisoned, to burn up in Earth re-entry and return, in its component elements, to Earth’s ecosystem; or, if deemed too hazardous, fired at the sun to burn up harmlessly there. The Moon could also be pressed into service, providing some materials for construction, and possibly more basic chemicals and elements for survival.

This makes sense, as we obviously know all the things humans need for survival are right here, on Earth. If we venture to another planet in another solar system, we may discover that it is lacking one or more of those needed elements, potentially jeopardizing or dooming our ability to survive on another world.

In Verdant Skies, the plan implemented by the U.N. found itself running out of funds before it could be finished. The result was the completion of two satellites by the U.N.—the satellites Verdant and Tranquil—a third by a cooperative deal between the U.N. and the countries of Africa and the Middle East—the satellite Fertile (with the idea that the satellite would be dedicated to the citizens of Africa and the Middle East exclusively)—and a fourth satellite—Qing (Chinese for “Lush”)—financed and constructed solely by China (and occupied only by Chinese citizens). In the end, only the four satellites were built and occupied, and though they could supported a large population, it was only a fraction of the human population that the U.N. had wanted to move to orbit.

In the novel, this puts humanity in a very tenuous position when the globe is threatened by the unexpected eruption of the Yellowstone Caldera. In an ideal situation, the successful completion of the U.N. plan, humanity would have been able to ride out the Earthly disaster from orbit, subsisting on its stored supplies, possibly in an emergency rationing state until the crisis was over; then return to Earth when the environmental disaster had calmed down. The much smaller support population on Earth would have hopefully been able to ride out the disaster (or even retreat to the satellites to wait it out), then rebuild damaged systems and resume support operations for the satellites. Even if environmental conditions on Earth were so serious that support workers had to wear protective gear in order to survive, Earth would still be accessible as needed.

In the novel, this puts humanity in a very tenuous position when the globe is threatened by the unexpected eruption of the Yellowstone Caldera. In an ideal situation, the successful completion of the U.N. plan, humanity would have been able to ride out the Earthly disaster from orbit, subsisting on its stored supplies, possibly in an emergency rationing state until the crisis was over; then return to Earth when the environmental disaster had calmed down. The much smaller support population on Earth would have hopefully been able to ride out the disaster (or even retreat to the satellites to wait it out), then rebuild damaged systems and resume support operations for the satellites. Even if environmental conditions on Earth were so serious that support workers had to wear protective gear in order to survive, Earth would still be accessible as needed.

But in Verdant Skies, the much larger population on Earth simply wants to escape the destruction of Earth’s ecosystem by evacuating to the four orbital satellites, even though those satellites don’t have the resources to hold any significant amount of refugees. This puts unworkable pressure on the satellites, and leads to the incredible chain of events in Verdant Skies and Verdant Pioneers.

But in Verdant Skies, the much larger population on Earth simply wants to escape the destruction of Earth’s ecosystem by evacuating to the four orbital satellites, even though those satellites don’t have the resources to hold any significant amount of refugees. This puts unworkable pressure on the satellites, and leads to the incredible chain of events in Verdant Skies and Verdant Pioneers.

Maybe someday we’ll see humanity attempting to build and occupy orbiting satellites like Verdant and the others… in real life, or at least, on the silver screen. (And hopefully in a manner that makes more sense than in Elysium).

In the meantime, we can watch Interstellar… then maybe read Verdant Skies, and decide which seems more likely.

(Yes: That was a challenge.)

November 7, 2014

Are we alone?

A few articles last week have tried to parse the comments of Dr. Brian Cox about the likelihood of extraterrestrial life. In an episode of BBC’s Human Universe, he said:

A few articles last week have tried to parse the comments of Dr. Brian Cox about the likelihood of extraterrestrial life. In an episode of BBC’s Human Universe, he said:

“There is only one advanced technological civilisation in this galaxy and there has only ever been one—and that’s us. We are unique. It’s a dizzying thought. There are billions of planets out there, surely there must have been a second genesis? But we must be careful because the story of life on this planet shows that the transition from single-celled life to complex life may not have been inevitable.”

Later, Cox tweeted:

What’s the story? Cox has been trying to make clear the fact that life, while exceedingly rare, is likely to have occurred elsewhere in the cosmos. He also contends that it is much less likely that one of those places has developed an advanced civilization like our own. But he insists that, in the unimaginable vastness of the cosmos, there probably are other civilizations (just, he thinks, not in this particular galaxy—so, maybe the next one over).

It may be that BBC has been slightly misinterpreting his remarks in promotion of the program, however unintentionally. But it’s actually hard to say, because Cox, like many other science media personalities, is a bit of a showman; and maybe this supposed controversy was planned all along. (Look: It got noticed by the trades and the web; mission accomplished.)

Here’s my two yen: Given that we’re on a planet with (by one estimate) 8.7 MILLION distinct species—and of those, only ONE offshoot of ONE species has developed a refined tool-making civilization, languages with abstract elements and advanced knowledge and ability to use science, technology, engineering and mathematics—the implication is clear that such advanced development is exceedingly rare.

But not impossible.

But since the many elements that made our civilization possible on Earth could have been duplicated on another planet—but we don’t know if it actually has—the only thing we can do is continue to look for any other signs of extraterrestrial life and development, with the intent to replace those abstract odds with hard numbers.

I do suspect, however, that humanity will never know whether it is, in fact, alone in the cosmos. By the time the last human descendant dies off, who knows how many millions or billions of years from now, we may have only managed to closely study the barest fraction of the volume of everything out there, which may even include parallel universes that we’ll never be able to access, or even observe. There is just too much of it out there to search, no matter how long-lived we turn out to be.

But as this is one of those endeavors that will certainly reap other benefits for our species’ knowledge and survival, it’s worth the pursuit. As many people, who like to travel about to see the world, are wont to say:

It’s not the destination; it’s the journey.

November 6, 2014

Solar freakin’ roadways… in action!

The world’s first solar bike path has been installed in the Netherlands, with further plans to embed solar panels into the country’s 140,000 km of road to power everything from traffic lights to electric cars. Read more here.

The world’s first solar bike path has been installed in the Netherlands, with further plans to embed solar panels into the country’s 140,000 km of road to power everything from traffic lights to electric cars. Read more here.

November 4, 2014

Logocracy: The next logical step in government

There was an interesting discussion on IO9, inspired by a post that sought to define a technocrat. The discussion, begun by me, was in response to the notion that technocrats could create a “technocracy,” a technocrat-run government:

There was an interesting discussion on IO9, inspired by a post that sought to define a technocrat. The discussion, begun by me, was in response to the notion that technocrats could create a “technocracy,” a technocrat-run government:

Though technocracy may not be capable of wholesale operation of an entire country—and I’m not so sure it would be much worse than the systems that operate today—it should at the very least be more of a part of existing political systems, more heavily factoring into some decisions. I’d go so far as to suggest it take an equal place in American government, placed beside the Executive, Legislative and Judicial branches. (And maybe outright replace the Legislative branch.)

Presently our U.S. government consists of three branches, Executive, Legislative and Judicial. Carefully designed by our Founding Fathers, the system was designed to allow laws to be created, but with a set of checks and balances in place to make sure no one group could completely dominate the government system. They also designed the system to be evolving, as the country grew and attitudes changed.

The Democratic system designed by our Founding Fathers mostly works… but in the last century or so, it has increasingly fallen into a pattern of outside influence and internal corruption causing the wheels of government to come almost to a standstill. Most of the seized wheels are in Congress, the House of Representatives and the Senate, whose members have increasingly been chosen according to who could wage the most successful media attacks on their competitors, and who make more of their decisions according to the wishes of wealthy lobbyists and their desires for comfortable retirement packages.

As well, the U.S. has become an increasingly populous, busy and complicated country, making the passage of laws and bills a much more intricate and involved process. Congresspeople do not have the time (nor, apparently, the inclination) to properly analyze and consider the laws that pass in front of them; as a result, bad laws are passed, or bad riders are added to laws, going unnoticed by politicians and eventually doing damage and making the system of laws even more convoluted than they need to be.

This sounds, to me, like an area of government in need of serious evolution in order to remain viable. And so, I proposed a system utilizing the full capacity of an invention originally created in wartime, which has served our government well for many years: The computer.

I suggested the replacement of the Legislative branch, specifically, the representatives in the House and the Senate, with a computer system, a logocratic system that would assume the voting role of the leaders of Congress. A Congressional Computer (or CC) would be placed in the position of enacting laws for the country. The computer would make up the new Logocrative branch of the government, taking its place alongside the Executive and Judicial branches.

To keep We The People connected, citizens would vote for the people who would supervise the state personnel who would collect and input data on each state’s conditions, resources, issues, needs, etc (data collectors and programmers, basically). The data they collect and process would be input into the CC, which would then evaluate the data from each state against those of all other states and territories. Then the CC, capable of analyzing that ocean of data better than any group of human politicians, would make the decisions and pass the laws for our country, much faster, much more fair and more impartial.

The administration of data collection and analysis would still be in The People’s hands to monitor and control by vote. This means the dangers of lobbying, bribery and corruption would still be a risk; but with the proper checks and balances to allow public analysis of the data input to the CC, it would be much harder to get away with “cooking the books.” And accuracy (or lack thereof) would directly impact the salaries, pensions and benefits of those in the data offices, who could be removed immediately if found to be underperforming by a set level.

And the President and the Judicial system would still be able to veto CC laws, much as they do Congressional laws, mostly based on whether the law was too far afield of the spirit of the union or did not properly address some issue that the CC’s programming was incapable of handling properly (such as the social or psychological impacts of a law, for instance).

Of the existing government branches that could potentially be replaced with a computer-based system, this strikes me as the most workable and providing the best improvement to the U.S. government system. This new Logocratic system, with humans overseeing a computer-run process of analyzing data and making laws, could be the next logical step in the evolution of the U.S. government.

The next step could be to begin development of such a computer system, a Congressional Computer that could be tested against the performance of the existing legislative branch until the achievement of certain performance milestones indicated the CC could do the job better than the existing Congress; whereupon, the reins of voting would be transferred from the representatives to the CC in short order.

I would not expect an idea like this to not be controversial; indeed, it’s a very significant step in the improvement of the U.S. government, but it would seem on its face to go against the idea of government “Of the People, By the People and For the People.” In fact, the application of a CC is merely an extension of the wealth of computers we use to run the country now; we’re simply giving the computers a higher role in the process, and still keeping it under our control. That’s why I think that evaluating it against the existing Congress would be crucial to establishing that the CC could indeed do the job better than a building full of professional politicians.

A story based on these notions has been in my notes for quite some time… a shame that I may never write it, because I think it would make for some interesting reading. I also saw no responses when I proposed this Logocratic system on IO9; so I wouldn’t mind hearing anyone’s opinion on the matter (consider this one of those rare times when it’s okay to discuss politics in polite company).

November 3, 2014

Space: Tourism’s setback is industry’s gain

Last week’s tragic crash of Scaled Composites’ Space Ship Two, the prototype short-hop orbital vehicle designed for Virgin Galactic, is a sober reminder that getting to space is, quite literally, rocket science; more than crossing oceans by boat, more than bisecting hemispheres by jet, travel to space is very hard and very hazardous.

Last week’s tragic crash of Scaled Composites’ Space Ship Two, the prototype short-hop orbital vehicle designed for Virgin Galactic, is a sober reminder that getting to space is, quite literally, rocket science; more than crossing oceans by boat, more than bisecting hemispheres by jet, travel to space is very hard and very hazardous.

When combined with the explosion and total loss of the unmanned Antares supply rocket, less than a week earlier, pundits are naturally predicting future hard times for commercial-based space rocketry. But that’s actually okay; for every setback is an opportunity to find the mistakes and improve the science and engineering, which will save lives in the future. It’s also an unsubtle reminder that space is never to be taken for granted.

But it’s not a reason to abandon our efforts to get to space. If anything, it’s a reason to rethink why we want to go to space.

Virgin Galactic, for instance, wants to provide a way for the richest people in humanity to part with their millions for what is essentially a joy ride. (Keep in mind, we are not talking about something akin to eco-tourism, where a portion of the tourist proceeds goes into preserving the ecosystem being visited. Though tourists may enjoy the view from up there, every dime paid to Virgin Galactic stays in Virgin Galactic’s coffers.) The crash of Space Ship Two will probably set back Richard Branson’s plans along those lines, albeit temporarily. But Branson’s plans are more showy and capitalistic than practical, affecting only himself… and there are much better reasons to go to space besides tourism.

Keeping the International Space Station functioning, for instance: The ISS, our primary orbital presence, carries on experiments vital to our understanding how various things, including the human body, can survive and thrive in space. And the results of those experiments could lead to new products and developments, including new manufacturing and fabrication processes that may be able to take advantage of the microgravity, hard vacuum, variable temperatures and radiation spectra available outside Earth’s atmosphere. New and better medicines, stronger and more versatile materials, better sensors, more efficient computers, better understanding of our planet and the Solar System, and many other things, stand to benefit from the advances possible from orbit.

Keeping the International Space Station functioning, for instance: The ISS, our primary orbital presence, carries on experiments vital to our understanding how various things, including the human body, can survive and thrive in space. And the results of those experiments could lead to new products and developments, including new manufacturing and fabrication processes that may be able to take advantage of the microgravity, hard vacuum, variable temperatures and radiation spectra available outside Earth’s atmosphere. New and better medicines, stronger and more versatile materials, better sensors, more efficient computers, better understanding of our planet and the Solar System, and many other things, stand to benefit from the advances possible from orbit.

And the lessons we learn from orbit will improve our knowledge of living in non-Earth environments… a very valuable lesson to learn, because someday, we may need to live in such non-Earth environments for extended periods, up to—potentially—forever. If, at some point in the future, Earth becomes inhabitable due to some natural (or man-made) disaster, a random strike from an asteroid, or a burst of gamma radiation from a dying star, etc, Mankind may need to be able to leave this planet and set up permanent shop elsewhere, or perish. The sooner we learn how to live in closed environments and hostile locations, therefore, the more likely we are to be able to survive such a catastrophe.

At some point, maybe soon, we may begin expanding our orbital presence with additional space platforms, perhaps carrying on expanded versions of experiments started on the ISS (or MIR, or even Skylab before them). Or maybe, the orbital platform will be put to specific use, say, setting up and operating a manufacturing facility that produces some valuable product better than it can be created in Earth’s atmosphere and gravity well. Or operating as a base for other space-based tasks, like launching satellites, cleaning up orbital debris, monitoring the solar system for incoming asteroids, or constructing space-based craft that will someday ply the Solar System and even beyond. An orbital platform (or a series of them) could provide an invaluable service to those living on the surface of the Earth… and may help us immensely when it’s time for us to leave.

Examination of the Space Ship Two malfunction will provide us further information on engine systems, safety systems connected to the engines, and the capsule itself. That will be added to the data compiled from other past missions, including the accidents that have resulted in everything from hardship to loss of life. All of that data will help us design and improve future rockets and engine systems, making the odds of our success in space that much better.

Industry, of course, weighs benefits versus risks in order to do business. When the risks are low enough versus the potential profit, industry will be ready to do business. Improved knowledge about engine and safety systems, therefore, will duly lower that risk and pave the way for industry to move into space and get busy.

So, let’s hope our efforts to achieve a stronger presence in orbit are not put off by these recent accidents, but informed by them instead. And perhaps more importantly, let’s hope that the Virgin Galactic crash clues some people to the fact that, while it’s important to go to space, there are much more important reasons to risk human lives than mere tourism.

October 31, 2014

Six Ways Franchises Go Terminal

I just want to go on record as loving this Observation Deck article about Six Ways Franchises Go Terminal. My favorite reason is #2, not only for itself but for the franchise they chose to illustrate the point:

2. The Creators Have No Frickin’ Clue What The Franchise Is About

And the example they chose: None other than Star Trek, and the J.J. Abrams-inspired clusterf**k of movies that totally manage to miss the point of the franchise and Gene Roddenberry’s vision (because all Abrams really wanted to do was make a Star Wars movie). I have especially warm feelings for this bit, about Star Trek Into Darkness‘ use of the character Khan:

And the example they chose: None other than Star Trek, and the J.J. Abrams-inspired clusterf**k of movies that totally manage to miss the point of the franchise and Gene Roddenberry’s vision (because all Abrams really wanted to do was make a Star Wars movie). I have especially warm feelings for this bit, about Star Trek Into Darkness‘ use of the character Khan:

The story makes no sense, and serves no purpose other than to reboot Khan and make him into a Dark Knight Joker-style übervillain, which he never was on the original series or in Wrath of Khan. (The thing about Montalban’s Khan is that despite his supposed genetic superiority he’s actually kind of a histrionic, swaggering dumbass, and not a cool Hannibal Lecter type.)

Nail head, meet hammer. Much more goodness in the article… go and see.

October 28, 2014

Concept For Future Aircraft Next Generation

October 27, 2014

An old show format for a modern SF TV show

In an earlier post or two, I’ve said that it’s time to move on from the Star Trek franchise and create a new SF TV franchise. Why? Because Star Trek was a show built around the concerns and issues of the latter half of the twentieth century; it is now time for a show that examines the issues of the nascent twenty-first century.

In an earlier post or two, I’ve said that it’s time to move on from the Star Trek franchise and create a new SF TV franchise. Why? Because Star Trek was a show built around the concerns and issues of the latter half of the twentieth century; it is now time for a show that examines the issues of the nascent twenty-first century.

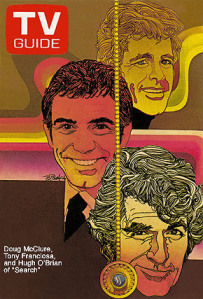

We’ve had a few SF shows come and go since then, and most of their formats have been pretty familiar (some of which because they were reboots). But I was recently reminded of a show format that hasn’t been used in science fiction television for literally forty years: That of the TV series Search. Maybe this particular format is due for a comeback.

Any readers here who are less than 50 years old will probably not remember Search. Produced by Leslie Stevens, and based on the format of an earlier show of his, , Search was a show about a high-tech investigations organization, connecting three field agents with a sophisticated Control Center of computer and communications experts and specialists. The field agents, played by Tony Franciosa, Doug McClure and Hugh O’Brien, all had distinct covers and methods of operation, and specialized in certain types of investigations each… and each carried a sophisticated scanner and communications device that linked them to the Control Center. With the help of the Control Center (headed by popular actor Burgess Meredith, post-Penguin and pre-Mickey), monitoring their actions and vitals and supplying them information in realtime, they solved their cases and brought in their men.

(In this way, it has a lot of similarities to a current TV show, Person of Interest: Agents in the field, being assisted in realtime by computers and connections to public and private networks and surveillance systems. Of course, no one at the time was worried about the “ubiquitous and pervasive” surveillance environment of the show that PoI highlights… maybe viewers assumed then that it could never really happen…)

Now here’s the unique format I mentioned: The show followed only one agent in each episode—one week it was Tony, the next it was Doug, then Hugh, then back to Tony, etc—with the Control Center being the common element in each episode. The field characters would even occasionally mention the others, since they’re all part of the same organization, but were rarely or never seen in the same episode together. (Tony Franciosa was also one of the stars of The Name of the Game… obviously Stevens and Franciosa thought they had a good thing going in recreating their earlier show with a new science fiction element.)

Now here’s the unique format I mentioned: The show followed only one agent in each episode—one week it was Tony, the next it was Doug, then Hugh, then back to Tony, etc—with the Control Center being the common element in each episode. The field characters would even occasionally mention the others, since they’re all part of the same organization, but were rarely or never seen in the same episode together. (Tony Franciosa was also one of the stars of The Name of the Game… obviously Stevens and Franciosa thought they had a good thing going in recreating their earlier show with a new science fiction element.)

This essentially allowed for extra time to produce each actor’s segment, as well as each of the three starring actors’ working a third as much to finish one season of shows (with most of the common element supporting actors working at a lower scale, this could potentially mean a significant cash savings to production—but it may have only meant the leads worked less for the same money). And the other advantage is having three starring actors, not one, creating more of an audience draw (most viewers might have one favorite, but they watched most of the shows with their non-favorites as well).

Here’s why I think this is a great format for a new SF series: Star Trek was essentially about a huge battleship full of every military and scientific expert possible, and that one big ship got into absolutely everything. In the latter half of the twentieth century, where the outside world held a lot of unknowns, including the potential for high-powered enemies and cold-war threats, showing up on an isolated and unknown island with a full military complement almost makes sense.

But today, we are much more familiar with the world out there. Our threats aren’t from big bads with A-bombs, they’re from terrorists with IEDs, hackers and corrupt politicians. We’re less concerned with who might jump out of the rocks behind us, and more concerned with who’s monitoring us from the cellphones in our hands. It’s a very different world, one in which it makes little sense to sail into every little port with a battleship looking for trouble.

This is the age of the small team of specialists, moving on advanced knowledge on where they’re going and what they expect to find. A modern SF series should be indicative of this: A universe where we already have some knowledge of the places we’ll visit, or what we expect to find there, and send specialized teams accordingly.

This new show could follow a different crew each week, with a common organization or coordinating body tying them all together, similarly to Search. Perhaps one team is made up of archeologists, searching for sings of alien civilizations (and occasionally finding them); another team might be geologists, searching for new fuel sources or other exotic elements; another team could be environmentalists, seeking new planets to settle, or new flora and fauna to add to our information; and another group is a military or police body, perhaps looking for relics of past wars, seeking out terrorist placements, or tracking down that idiot old soldier who doesn’t know the war ended fifty years ago. One could even be a one-person operation, a traveling troubleshooter dealing with smaller problems and helping out where needed.

Each team’s story would be different, based on the type of missions they embarked on, and their unique set of problems. The audience would get stories of a greater variety, and connecting elements would help connect the disparate story types together, keeping their attention during the weeks when the story types weren’t their favorite. Smaller groups tend to create more intimate relationships, enabling more personal stories that audiences respond favorably to.

There is admittedly one downside to this show format: Maintaining multiple groups, or units, of different actors, sets, etc, can be more costly than maintaining only one core group. Science fiction shows already tend to have larger-than-usual budgets, so this show could be inordinately expensive, not feasible for small-budget production at all.

On the other hand, science fiction is already notorious for needing extra production time, to handle special effects, elaborate sets and costumes, experimenting with makeup, etc. Giving each production group more time in which to produce their segments for airing might make for a better production, not to mention serving audiences by being able to get more shows on air at once, and not being forced to break into small mini-seasons to accommodate lengthy production demands. And having to rush through the work might even allow some financial savings to each episode.

This format brings with it a number of possibilities, both for the show setup and for the organization of its multiple units and the core element that ties them together. And being that this format hasn’t been used for so long, it automatically means creating a show that will feel fresh and innovative to its audience. Actors could be kept with their groups, or mixed and matched depending on the story’s need. This also allows more actors a chance to get a bit of the limelight by being part of smaller ensembles, a much better deal than being part of a large ensemble and possibly not getting meaty scenes for months apart. There may be budget short-cuts possible (do they all travel to other planets? Use the same ship, and change the name and a few external features for each group). It may even be feasible to “farm out” production to smaller or local groups looking to make a mark in Hollywood. It makes for some interesting organization and production possibilities.

Cost alone may prevent this from ever happening; but I, for one, would love to see the variety and innovation we’d get from a science fiction TV production set up along these lines.