Steven Lyle Jordan's Blog, page 19

December 24, 2016

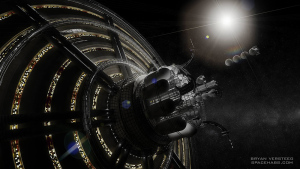

Simulating the high frontier

Neel Patel has posted a great article related to orbital colonies: He and Joe Strout, a software engineer, took the city-building software of Sim City and translated it into an orbital colony in space, said software called High Frontier. Then Neel operated it as administrator, to see what it would take to run such a colony.

Though there were significant engineering challenges, one of the biggest problems Neel had was getting people to come to his colony… and stay. In fact, I had the distinct impression that Neel and Joe had spent all their time conceiving of the colony from an engineering standpoint, with the attitude of “if you build it, they will come.” Not that that’s their fault; it’s the basis behind Sim City’s programming regarding social activity.

[image error]Neel, Joe and Sim City didn’t take into account that that premise applies primarily to tourist attractions (like Disney parks, ballfields in Iowa and pyramids in Vegas). They did add typically Sim City elements like stadiums, museums, parks and other city infrastructure, and saw public activity as a result. But once the novelty has worn off, you need a lot more to make people stick around… and more importantly, to make it a home.

For instance, what was the jobs situation? Were there fun and lucrative jobs to be had there? Were any major corporations setting up residence in the colony and offering desirable employment? Or at least job opportunities that were attractive to people who couldn’t get jobs on Earth? Did they consider offering residents a universal basic income, so they’d be free to work major jobs, lightweight jobs, or just live there with no job? Those are major attractors to a stable population base, and must be considered up-front.

And speaking of attractors: Were stadiums, parks and museums enough? If the amenities aren’t that different from those on Earth, they won’t be enough to attract anyone beyond tourists. An orbital colony should have elements that can’t be had on Earth—such as low- and no-gravity sections, and facilities that take advantage of that for entertainment, science and manufacturing, health, sports and education.

[image error]And none of that will attract people, unless they know about it, which brings up the issue of advertisement: How much time and money would be spent advertising your colony? With celebrities and other beautiful people in glamorous or lucrative activities, gorgeous scenery and relocation packages no one can resist? The uniqueness of the colony needs to be highlighted for potential residents, as much as its viability as a long-term residence.

When I wrote Verdant Agenda, I described such an orbital colony years after it was constructed, with plenty of jobs, regular visitors and permanent residents. I didn’t describe many recreational facilities, but then, my story was centered around a disaster and occupation… and no one thinks about Disneyland when lives are at stake. Still, these things are important to create a place that people will want to visit, find jobs or put down roots.

[image error]And speaking of Disney: Many have forgotten that Walt Disney’s original design of Disney World’s EPCOT Center in Florida was to be a city or workers and residents, a living example of modern life. But even Disney couldn’t get it past the amusement park stage… and he knew showmanship and advertising better than most. (To be fair, EPCOT had a lot of engineering problems that couldn’t quite keep up with Walt’s conceptions.) Instead, Disney World remained a tourist attraction, though it helped build the neighboring city of Orlando to support it. Bending the will of the people to your way of thinking is always tricky, and Walt Disney stands as a reminder that even the greatest ideas and the best of intentions don’t always work out as you intended.

Though the simulation had its flaws, Neel and Joe should be given credit where credit is due, experimenting with the simulation as a first step. Further simulations that take into account the elements Sim City does not, like social dynamics based on advertisement, job availability and colony uniqueness, should continue to provide useful data on how to build a colony, and how to settle it.

Neel’s article can be read on Inverse.

December 2, 2016

Kestral: My biggest mistake ever.

For years, I wanted to create a sci-fi series… a sort of “comfort project” that I would enjoy working on over time. The Kestral Voyages became that series, a unique combination of serious science fiction and adventure elements designed to make a fun read. But how it came together is a story in itself, because it was originally supposed to be an entirely different series.

For years, I wanted to create a sci-fi series… a sort of “comfort project” that I would enjoy working on over time. The Kestral Voyages became that series, a unique combination of serious science fiction and adventure elements designed to make a fun read. But how it came together is a story in itself, because it was originally supposed to be an entirely different series.

And if I’d played my cards differently, it might have been the series that would’ve made me famous. (Shows what I know about card playing.)

During the last season of Star Trek: Voyager, Paramount studios announced that they would be making a new Trek series, but wanted to take ideas from Trek fans on what the setting of that new series would be. Trek fans were quick to respond to the challenge, and I was no exception.

I started upon designing a new Trek series, but not another space-warship discovering monsters and riddling out esoteric physics phenomena, as all the past series had done. I wanted a series that would show the civilian side of the Federation, something we’d gotten only in tiny spoonfuls over the years. I wanted a series about regular people, carving out a living (and hopefully having some cool adventures) in Federation space.

Television has plenty of examples of such shows, which I won’t enumerate here; but interestingly, where the original Star Trek was described as “Wagon Train to the Stars,” my series would be a lot like “Rawhide to the Stars.”

I took my inspiration from the Star Trek novel Prime Directive, in which James Kirk was introduced to Anne Gauvreau, a former Starfleet officer who, tired of her superiors refusing to give her a major command of her own by virtue of her simply being female, resigned her Starfleet commission to become a freighter captain instead. She was capable, intelligent and shrewd, but she was also perfectly happy captaining her own freighter and going wherever time, tide and freight shipments carried her.

I took my inspiration from the Star Trek novel Prime Directive, in which James Kirk was introduced to Anne Gauvreau, a former Starfleet officer who, tired of her superiors refusing to give her a major command of her own by virtue of her simply being female, resigned her Starfleet commission to become a freighter captain instead. She was capable, intelligent and shrewd, but she was also perfectly happy captaining her own freighter and going wherever time, tide and freight shipments carried her.

I based Captain Carolyn Kestral on Anne Gauvreau. I also altered Kestral’s reason for leaving Starfleet, since discrimination in the Star Trek universe isn’t quite what it used to be: Instead of having her quit from frustration of not being given a ship of the line, Commander Kestral was dosed with an alien virus during battle, a virus that was supposed to turn her into a berserker killing machine, a space-Hulk intended to wipe out as much of her surroundings (and fellow officers) as possible before her body burned out and killed her.

But as sometimes happened with humans, the virus didn’t take. She was rushed to a medical facility, and treated to remove the virus. But, as also sometimes happened with humans, not all of the virus could be removed. Because a trace of the virus remained in her, her fellow officers and crew were always concerned about the possibility of her being triggered by a moment of stress or anger (though her medical record did not indicate that as a possibility at all). Concern became discrimination, and she was unable to rise to Captain or command a ship. So she resigned her commission, and bought a freighter.

Having established my main character, I went about creating members of her small crew. First was a pilot, possibly an alien, possibly from Mars, also an ex-Starfleet man, who had disobeyed orders to save civilians; and was given an honorable discharge so a superior could save face. He was wrongly treated, but since ultimately he did the right thing, he wasn’t concerned about how others saw him. His character would give Kestral a connection to their former service, as well as someone who could remind her that they were civilians now, but through no fault of their own.

Next I wanted a couple, a burly engineer from Earth, and an alien wife. Their being married was most significant here: Inter-species marriage is something Star Trek has mostly paid lip-service to, but rarely shown in its various series. I wanted them to help ground the series as well as representing Trek’s credo of infinite diversity in a family dynamic.

And finally, I added a character who would take over some of the cargo holds and grow their own food on-board. I saw this as a further way to return to humanity’s roots—so to speak—and give an ecologically-minded audience the familiar look of farm-grown foods and sit-down dinners in a galley-kitchen. Thus, I had created an extended family unit, working together, bringing different perspectives to situations they encountered, and getting into as many domestic scrapes as external adventures.

So, here’s the thing: I’d created all of this, with the original idea of sending it to Paramount to see if they’d bite at a new series, and achieve fame, fortune, all that stuff. When I suddenly came to my senses. I realized that the whole “choose our next series!” bit was exactly the kind of thing a studio would do to keep audience excitement high while they readied their next series. In fact, I was willing to bet everything I had that at the time of the initial announcement, Paramount had known for some time exactly what they intended to do for the next series, were probably already setting everything up and building set pieces, and were only shy of actual cast members to begin production.

(As proof of my theory, I offer Star Trek: Enterprise, a premise that was so much lamer than I-don’t-know-how-many other series pitches I heard in online forums and such. You guys at Paramount had some great ideas sent to you. That you chose to do Enterprise clearly demonstrates that you had no intention to even look at all the other ideas out there. More’s the pity.)

I further reasoned that a studio that would pull this stunt on Trek fans would also not be above stealing an idea I sent to them and not giving me credit—or payment—for it. Faced with this reasoning, I decided not to send Paramount my idea; it was too good to be wasted by them.

But the premise I’d cooked up had good bones, and I didn’t see any reason to waste it myself. I would write my own stories. However, I couldn’t write Star Trek stories, because I didn’t have the rights to them, which meant I couldn’t sell them. So I decided to make alterations to the names, places, races and universes depicted in my premise, and create an original universe for the characters to cavort within. I wrote The Kestral Voyages: My Life, After Berserker, set in a universe that was similar to the Trek universe (though really more similar to the Firefly universe… that’s another story) and released it to comments and reviews that were decent enough to convince me I should write more.

This was, quite probably, the biggest mistake of my life.

What I should’ve done was to write the stories set in the Star Trek universe, then offered them online to everyone for free. It would have earned me no income… but as free Star Trek fanfic, the stories could have garnered more attention from the world’s many Trek fans, in much the same way that 30 Shades of Grey, originally written as Twilight fanfic, became a worldwide phenom. If my books had become popular, they could have earned me a fan base that might’ve propelled my non-Star Trek novels… and that might’ve actually made me some coin.

To date, I have sold more of the three Kestral books than any other series or standalone novel I’ve written. Not that that’s saying much: The grand total of sales from the Kestral series wouldn’t get me and my wife a single meal in a decent restaurant. But it suggests they would have been even more popular as free commodities. In short, taking out the Trek elements and selling the novels only served to rob me of the best opportunity to become known in science fiction circles.

I effectively self-strangled my own writing career.

I effectively self-strangled my own writing career.

And coming to that realization, I’m still wondering whether I can do anything about it. As in: Should I rewrite the Kestral novels back into the Trek universe and offer them free to anyone who wants them? Is there a possibility that the series could still take off and gain big popularity? Is this a good time to do it, with a new Trek series right around the corner?

Or is it already too late? Is the Karma train long gone, never to come back this way again?

As I’m presently busy trying to lock down a long-term or permanent job (anyone need a front-end web developer? Drop me a line), I won’t be doing any writing anytime soon. But assuming I find a job in time to continue living in the manner in which I’m accustomed, it’s entirely possible that I’ll eventually go completely insane and decide to write once more. And if so, the rewrites of the Kestral books are one possible project. Feel free to weigh in on the matter; unlike Paramount, I haven’t made up my mind yet.

November 27, 2016

Black Mirror: A world I want no part of

I’ve been watching Black Mirror, that highly-acclaimed SF series on Netflix, for the past few weeks (I’m too busy to binge-watch anything). Not quite done with season 3, I can easily see why it’s so acclaimed; but alas, I don’t have as high an opinion of the series as others seem to.

I’ve been watching Black Mirror, that highly-acclaimed SF series on Netflix, for the past few weeks (I’m too busy to binge-watch anything). Not quite done with season 3, I can easily see why it’s so acclaimed; but alas, I don’t have as high an opinion of the series as others seem to.

As the name implies, the show offers a mirror to the dark side of our society, and it does a great job, production-wise, of doing that. Except that it really doesn’t. This show offers us a mirror into an alternate universe, where absolutely everything and everyone is intentionally designed to be evil.

Does anyone out there remember the Star Trek original series episode “Mirror Mirror,” where everything and everyone was an evil version of the main characters? The Federation enslaved entire planets, or destroyed them if they didn’t comply; Star Fleet officers did Nazi salutes, and attrition was by assassination. And if you thought about it, none of it made a lick of sense—that evil Federation wouldn’t have lasted a decade—but it made for good, dramatic TV to see tyrannical Kirk, Sulu with a nasty battle-scar, scheming Chekov, knife-wielding Uhura and Spock with a beard.

Does anyone out there remember the Star Trek original series episode “Mirror Mirror,” where everything and everyone was an evil version of the main characters? The Federation enslaved entire planets, or destroyed them if they didn’t comply; Star Fleet officers did Nazi salutes, and attrition was by assassination. And if you thought about it, none of it made a lick of sense—that evil Federation wouldn’t have lasted a decade—but it made for good, dramatic TV to see tyrannical Kirk, Sulu with a nasty battle-scar, scheming Chekov, knife-wielding Uhura and Spock with a beard.

Well, that’s what Black Mirror is. In fact, I’d go so far to say that the world of Black Mirror is the one that eventually became the alternate universe in “Mirror Mirror.”

As I’ve watched the show, intended to be a cautionary look at our love affair with technology in general and social media in particular, I’ve been fascinated by the forms of technology that the show has concocted: Memory-saving and playback chips apparently implanted in users’ heads; eye-cameras that identify someone or put data up in your line of vision; memory chips that learn your every habit, in order to be your personal “servant” and tend to your needs; these are among the most notable of technologies introduced by the series.

And I can think of any number of ways in which these technologies could be used to enrich our lives and our world. But Black Mirror doesn’t show those to you; in fact, it goes well out of its way to show you every negative possibility associated with that technology, to present nightmare scenarios of people isolated from human contact, memory chips that think they are humans trapped in virtual reality hells, and social media systems in the hands of—well, assholes—that can control your life and crash your career.

And I can think of any number of ways in which these technologies could be used to enrich our lives and our world. But Black Mirror doesn’t show those to you; in fact, it goes well out of its way to show you every negative possibility associated with that technology, to present nightmare scenarios of people isolated from human contact, memory chips that think they are humans trapped in virtual reality hells, and social media systems in the hands of—well, assholes—that can control your life and crash your career.

And in so many episodes, it’s been so incredibly obvious to me how the contentious beats of the stories could have been effectively handled by people actually talking to each other, working together to solve problems and help each other. But in every case, the moment was dominated by an asshole, exactly the kind of person who would make everything worse, just because they could… and did.

Okay—So maybe this is just me, seeing yet another TV show filled with the unnecessary and over-the-top melodrama that audiences seem to gravitate to like moths around a flame. Maybe this is just me, resisting the urge to stare at the train wreck that’s got everyone else’s attention, and trying to move on to better things. Maybe this is just me, wishing we could have television that shows good people who want to help each other, societies that work when people want them to, and happy endings whenever possible… or at least acceptable endings when we know no one’s going to actually win.

Maybe I’m just too old to appreciate nightmares any more.

Maybe I’m just too old to appreciate nightmares any more.

And so, as well-produced as Black Mirror is, the series simply frustrates and depresses me. Not just because of its downbeat, Twilight-Zone-ish stories where nobody lives happily ever after; but for its tacit admission that nothing, and I mean nothing, will ever be good about technology… or any of its users.

November 19, 2016

Not starships… orbital satellites

Physicist Stephen Hawking argues that Mankind must build starships and spread itself throughout the galaxy in order to survive, since Earth’s years are clearly finite. Hawking has made this case many times, being convinced that even a smallish catastrophe (like a massive meteor strike) could render Earth uninhabitable for humans, and it could do so at any time.

Physicist Stephen Hawking argues that Mankind must build starships and spread itself throughout the galaxy in order to survive, since Earth’s years are clearly finite. Hawking has made this case many times, being convinced that even a smallish catastrophe (like a massive meteor strike) could render Earth uninhabitable for humans, and it could do so at any time.

I wouldn’t presume to contradict Hawking; in fact, I agree with his assessment of the fragility of our ecosystem and its prospects for long-term viability. But when it comes to his opinion that we should leave Earth for our own survival, I have another option. I don’t think we need to leave Earth; I believe we can stay longer, even through a catastrophe, if we apply proper husbandry to the Earth. And we can do that better if we move the bulk of our population into orbital satellites.

Hawking suggests that we essentially use what we can here on Earth, then pack up and abandon it… much like our nomadic ancestors would use up a region, hunting out its game and farming its land into sand, then move on. He postulates either generation ships, or starships that can exceed the speed of light, to take us to distant planets in other star systems. He assumes that we will be able to find such a planet or planets, Earth-similar bodies in the “Goldilocks” zone of habitability, ready for life but apparently without established life of its own, just waiting for us to arrive and plant our flags (and then, presumably, our figs).

Let’s make sure this remains a game fantasy… shall we?

Let’s make sure this remains a game fantasy… shall we?This assumes a lot. For one thing, since we don’t know how to build an FTL drive, it assumes we can build ships capable of sustaining us for decades or even centuries in open space, far from any source of supplies replenishment or aid… which would be a damned impressive engineering feat (if even possible); but perhaps more importantly, it assumes that we have the right to take over any planets we reach that suit us, even if they have their own established life—for any planet capable of sustaining life almost certainly will have some sort of life of its own when we arrive—much as we have occupied regions already occupied by other humans and creatures and pushed them out for our own purposes. This intergalactic “manifest destiny” sounds too much like what we’ve done on our own planet, and it’s only brought environmental and social damage to our own history. Is that really something we want to take to the stars?

I say that with wiser husbandry, we can last much longer on our chosen range. First in our agenda should be making Earth more sustainable for us, right now. In much the same way that our agricultural ancestors learned to properly tend farmland, rotating crops and replenishing soils with needed nutrients, we can learn how to slow the process of turning our own planet into a dustbowl. We can better use resources, better avoid damage to the environment, and better make sure the environment is capable of being restored (and restoring itself) from our manipulations.

We could much better do that by moving the bulk of our population off of Earth, and into orbiting city-satellites like those touted by Gerard O’Neill’s book The High Frontier. We are on the verge of learning enough about using available resources, recycling used resources and being more efficient in our energy and waste usage to be able to enclose our ecosystems almost completely, removing ourselves from the fragile environment around us. Habitats orbiting in space can take full advantage of the wealth of solar energy pouring out around us to power themselves, and will have the opportunity to use centripetal force selectively, rotating in areas to provide simulated gravity where humans and other organisms need it, and maintaining gravity-free areas that can aid manufacturing, heavy machinery operation and other activities. Freed of gravitic and geological constraints, we can design and build our satellites in any configuration we see fit, making sure they are organic and flexible enough to be modified as the population changes over time.

We could much better do that by moving the bulk of our population off of Earth, and into orbiting city-satellites like those touted by Gerard O’Neill’s book The High Frontier. We are on the verge of learning enough about using available resources, recycling used resources and being more efficient in our energy and waste usage to be able to enclose our ecosystems almost completely, removing ourselves from the fragile environment around us. Habitats orbiting in space can take full advantage of the wealth of solar energy pouring out around us to power themselves, and will have the opportunity to use centripetal force selectively, rotating in areas to provide simulated gravity where humans and other organisms need it, and maintaining gravity-free areas that can aid manufacturing, heavy machinery operation and other activities. Freed of gravitic and geological constraints, we can design and build our satellites in any configuration we see fit, making sure they are organic and flexible enough to be modified as the population changes over time.

We will still need resources from Earth, of course; no orbital system should be assumed to be completely closed (at least, not for the foreseeable future). But our new living arrangement will demand that we apply much more sensible and efficient practices in gathering what we need and using it wisely. Small populations will probably remain on the ground, mostly tending to what mechanical or robotic equipment we use to collect raw resources and prepare them for shipment into space. We will truly become Earth’s shepherds, tending our charge without doing damage to it, and making sure it will serve us into the future.

We will still need resources from Earth, of course; no orbital system should be assumed to be completely closed (at least, not for the foreseeable future). But our new living arrangement will demand that we apply much more sensible and efficient practices in gathering what we need and using it wisely. Small populations will probably remain on the ground, mostly tending to what mechanical or robotic equipment we use to collect raw resources and prepare them for shipment into space. We will truly become Earth’s shepherds, tending our charge without doing damage to it, and making sure it will serve us into the future.

And what will result from any “smallish catastrophe?” If something like a significant meteor strike (or, as I fear is more likely, a major volcanic eruption like the Yellowstone Caldera is expected to give us… well, any time now) occurs, the Earth will suffer from major physical and ecological damage that may take decades, centuries, or even longer to properly recover from. But if humans are mostly in orbit, we will be in a much better position to weather out such a catastrophe, orbiting above the upheaval and returning to Earth only when it is safe or absolutely necessary. If we are living efficiently in space, we will hopefully be able to monitor the disaster and determine when and where it will be safe to return for supplies and resources. Small ground-based populations would be much more capable of quick evacuation (to the satellites, presumably) in an emergency, leaving our robotics to continue ground-based tasks if necessary. A significant geologic disaster may even upturn and reveal long-buried resources, making it easier to detect and collect them. We may need to wear protective gear or take other survival steps on Earth where, in the past, we did not; but we will ultimately still have access to the resources of the planet that birthed us.

And what will result from any “smallish catastrophe?” If something like a significant meteor strike (or, as I fear is more likely, a major volcanic eruption like the Yellowstone Caldera is expected to give us… well, any time now) occurs, the Earth will suffer from major physical and ecological damage that may take decades, centuries, or even longer to properly recover from. But if humans are mostly in orbit, we will be in a much better position to weather out such a catastrophe, orbiting above the upheaval and returning to Earth only when it is safe or absolutely necessary. If we are living efficiently in space, we will hopefully be able to monitor the disaster and determine when and where it will be safe to return for supplies and resources. Small ground-based populations would be much more capable of quick evacuation (to the satellites, presumably) in an emergency, leaving our robotics to continue ground-based tasks if necessary. A significant geologic disaster may even upturn and reveal long-buried resources, making it easier to detect and collect them. We may need to wear protective gear or take other survival steps on Earth where, in the past, we did not; but we will ultimately still have access to the resources of the planet that birthed us.

This would allow humankind to live much longer off of the bounty of the Earth, whilst simultaneously being less of a burden on it by making ourselves more efficient and self-sufficient. It would also give us more time to prepare for the next stage of human exploration… for, assuming we live long enough, we will eventually see the Sun go nova, then die, and we will have to leave the Solar System whether we like it or not. Maybe before then, we will have moved some of our orbiting habitats to the outer planets, perhaps living off the resources of Jupiter’s or Saturn’s moons, or the asteroids, and extend our stay in the Solar System as long as possible before our forced eviction.

This would allow humankind to live much longer off of the bounty of the Earth, whilst simultaneously being less of a burden on it by making ourselves more efficient and self-sufficient. It would also give us more time to prepare for the next stage of human exploration… for, assuming we live long enough, we will eventually see the Sun go nova, then die, and we will have to leave the Solar System whether we like it or not. Maybe before then, we will have moved some of our orbiting habitats to the outer planets, perhaps living off the resources of Jupiter’s or Saturn’s moons, or the asteroids, and extend our stay in the Solar System as long as possible before our forced eviction.

And most likely, we will have to stay in our self-contained homes, because—even if we should figure out how to get them to other stars—it is still highly unlikely that we’ll find a planet conveniently similar to our own biological needs, but also conveniently devoid of competing life, to allow us to simply land and move in. I wouldn’t want to see us landing and taking over another species’ planet, like a bunch of Europeans arriving in the New World and crowding the natives into reservations (or just plain wiping them out). I’m also not assuming that terraforming an entire planet will ever really be more than a pie-in-the-sky notion… and even if it was, terraforming would take longer to accomplish than actually travelling to the planet from the Solar System.

More likely is that we’ll find planets with the useful resources we can use to help sustain us in orbit, just as we will have used the Earth’s resources while staying in orbit; we will settle in orbit around those new worlds and begin the process of shepherding them to help sustain us. Maybe we’ll stay long enough to replenish our resources, then continue our travels, becoming a true interstellar nomadic species.

Which way will Mankind go? Off in starships to other worlds, as Hawking suggests? Remaining in the Solar System in space habitats? Or moving those habitats to other stars? Only time will tell.

November 17, 2016

“Ghost” and Hollywood whitewashing

Masamune Shirow’s anime series Ghost in the Shell is the latest to be made into a live-action feature film by director Rupert Sanders (due out in 2017). Unfortunately, the significance of such a groundbreaking work being developed for live cinema is being overshadowed by an unfortunate element of Hollywood film-making generally referred to as whitewashing.

Masamune Shirow’s anime series Ghost in the Shell is the latest to be made into a live-action feature film by director Rupert Sanders (due out in 2017). Unfortunately, the significance of such a groundbreaking work being developed for live cinema is being overshadowed by an unfortunate element of Hollywood film-making generally referred to as whitewashing.

In creating American versions of foreign films or other media, Hollywood will often take characters originally envisioned as being of a different race, such as the Asian character Major Motoko Kusanangi in Ghost in the Shell, and re-cast them with white actors (usually actors who are popular with the viewing audience). In theory, this is to make the character more palatable to what Hollywood views as a predominantly white audience—or an audience that they believe have a greater acceptance of whites in certain roles—which they believe will guarantee a larger box office audience, and larger profit on the film. The practice goes back literally to the beginning of the film industry, and has been commonly applied to Black, Asian, Latin, Indian and Native American roles in Hollywood movies.

But in the past decades viewers have been increasingly seeing this as a blatant attempt to erase minorities and foreign faces from American media (and the Hollywood machine in general), and they see it as less acceptable than it was considered decades ago. And the casting of (very-noticeably-not-Asian) Scarlett Johansson as the Major in Ghost in the Shell has inflamed the old controversy once again.

Whitewashing is controversial, but it’s not simple. After all, when you get down to it, there really is only one race—Human. So, on one hand, what’s the big deal? Many prominent white Hollywood stars and character-actors have appeared in originally-non-white roles; they’ve even been made up with prosthetics to actually resemble non-whites (more often caricatures of non-whites), to satisfy contracts or casting offices. And the practice has occasionally been reversed, with non-white actors being given roles originally written for white characters (so I suppose you could wrap the whole thing into a convenient label like race-swapping).

Whitewashing is controversial, but it’s not simple. After all, when you get down to it, there really is only one race—Human. So, on one hand, what’s the big deal? Many prominent white Hollywood stars and character-actors have appeared in originally-non-white roles; they’ve even been made up with prosthetics to actually resemble non-whites (more often caricatures of non-whites), to satisfy contracts or casting offices. And the practice has occasionally been reversed, with non-white actors being given roles originally written for white characters (so I suppose you could wrap the whole thing into a convenient label like race-swapping).

There’s no denying that Hollywood has been guilty of institutionalized racism since its inception. But does Hollywood care about this controversy? Put simply, NO; Hollywood is in the business of making money off of movies, the more money the better, end of line. In Hollywood, any element that can be changed, with the expectation of increasing the profit of the movie, is fair game. And that includes race-swapping wherever and whenever it’s convenient.

In Ghost in the Shell, they see an opportunity to insert a big box office superstar into a high-tech looking action movie, a genre they think very little of beyond raw profitability anyway. Placing Scarlett Johansson into the movie will increase box office through her name recognition, and increase their expected profits.

Okay, fine, Hollywood is changing a role’s race to improve profits; but could Hollywood have worked a bit harder at this, if it were just for profit’s sake? There are popular Asian actresses, familiar to American audiences, who could have been cast in the role of the Major. Maybe they are not as well-known as Johansson, but they would be recognizable enough to attract audiences. And many of them have done action films, giving them further cred with the audience. Hollywood is also experienced with using and promoting pretty faces who don’t have familiar names. (Hey, no star starts at the top, right?)

Asian actresses in Hollywood? There’s a few…

Asian actresses in Hollywood? There’s a few…Nothing against ScarJo, but many (including me) feel Hollywood could have found an Asian actress who would have suited this role just fine. Maybe it would have knocked a few bucks off the bottom line… but would it have killed them to bite the bullet and lose a few bucks out of the millions they can expect to make? And since a highly successful movie could help to propel a new actress into the A-list spotlight, giving Hollywood another big box office superstar… why not take the chance?

And how should the audience react to all this? It’s up to you: If you are okay with a movie in which you know changes have been made by an all-about-profit industry for sheer profit’s sake, accept the whitewashing as what it is, and go enjoy a movie. If you believe whitewashing is an intentionally-racist treatment of the source material, don’t watch the movie (and feel free to publicize on social media just how you feel; after all, if Hollywood thinks they’ll make a bigger profit by not whitewashing, you may help change things).

For myself, I’ll see the movie, probably in the theater. I don’t blame Scarlett Johansson for being the lead, nor do I dislike her as an actress; so I’ll watch, and hope she does a bang-up job in the role. But I will look sourly on Hollywood’s casting practices, and hope the future of Hollywood’s institutionalized racism is getting dimmer by the day.

November 16, 2016

Passions are for carrying… not following

On a Facebook group I recently discovered, an author decided it would be a good idea for other authors to post links to their FB pages, so the other authors could like their pages and generate increased interest. I decided to play along, and added my novels page to the group. Then I started going through the other links, in order to bestow my likes.

On a Facebook group I recently discovered, an author decided it would be a good idea for other authors to post links to their FB pages, so the other authors could like their pages and generate increased interest. I decided to play along, and added my novels page to the group. Then I started going through the other links, in order to bestow my likes.

That’s when I noticed a major difference between my pages and most of the other pages. Other authors had 300 likes… 600 likes… 1,200 likes… more. And these are authors who are fighting for sales of their books.

I had 28 likes. 28.

I’ve recently used paid Facebook ads to get my site out to over 2,000 people. Out of those, I got 28 likes. Out of those, I got 7 shares. And on Amazon, I got zero sales.

Despite the encouraging words of a few authors or other people I know, I’m just not seeing anything encouraging about those numbers. Further, I’m just not seeing the long game here; I can’t see how my strategy—how any strategy I could apply with my present resources—is going to succeed in a year, 10 years or 100 years. This writing thing has been—and continues to be—a bust.

Which brings to mind a commencement speech given by Mike Rowe last spring at Prager University. The host of the ground-breaking show Dirty Jobs, in his most eloquent way, pointed out to the recent grads that your personal passion, however enjoyable it may be, may not be something you can make a living at… heck, it may not even be something you’re any good at. And sometimes the most important part about being an adult is recognizing the difference between your passion and your actual aptitude towards it.

Which brings to mind a commencement speech given by Mike Rowe last spring at Prager University. The host of the ground-breaking show Dirty Jobs, in his most eloquent way, pointed out to the recent grads that your personal passion, however enjoyable it may be, may not be something you can make a living at… heck, it may not even be something you’re any good at. And sometimes the most important part about being an adult is recognizing the difference between your passion and your actual aptitude towards it.

But there are other opportunities out there, many of which match your actual skillset. These are the opportunities that should be pursued, because these are the opportunities that will allow you to make an actual living. Then, once that living is made, you can see if you can find a place to fit your passions into your life. “Never follow your passion; but always bring it with you.”

Good, practical advice, from a good, practical man. And as I look back at writing science fiction novels, an avocation that I thought would be an important part of my life, I now find I have to agree with Mike that it is, in fact, another passion that will not lead me through life, but may instead tag along behind me as I do other good works to make a living and provide for my family. (I say “another,” because it follows my first passion, pen-and-ink illustration, which I long ago found I had to relegate to a tagalong role in my life as well.)

Presently I’m between jobs, and while I’ve been pursuing other opportunities, I thought that maybe now was the time to bring my passion forward and see if it could sustain me through the future. But after a few weeks of consideration, I have to admit to myself that it’s still not ready for prime time, and in fact, creating an unwelcome distraction from what should be my primary duty, landing a new job.

And so, back to the closet it goes, to be brought back out someday when I have the luxury of time to pursue it.

Maybe.

Here’s Mike’s address, if you are interested.

November 9, 2016

Tomorrowland is closed for the season.

I wish I could say I have no words for what has happened in the USA today.

I wish I could say I have no words for what has happened in the USA today.

Unfortunately, I have quite a few. Only some of which are printable.

Yeah, I get that Americans want change… Americans always want change, because nothing is ever good enough for them. Foreign fears, domestic fears, personal fears… they are always there, at least with 99+% of the people. I also get that America almost never votes in the same political party after an 8-year term. That explains a lot of the election season we’ve just endured.

But it obviously goes far deeper than that. Americans are afraid of their neighbors, and still label people by their skin color. Americans are afraid of their law enforcement—either going too far to protect them, or not going far enough. Americans are afraid of countries they’ve chosen to never try to understand. Americans are afraid of a world that has changed since 1950, apparently the gold standard for an America that was considered G-rated and acceptable to the Andy Griffeth crowd.

And Americans have not only neglected their education, but they’ve spent so much time in front of television that they think reality shows, and their casts, are real people.

This combination allowed the most fearful of us to be taken in by a con man, a cheap carny huckster who knows all about manipulating the TV generation, but nothing about how to run a country. They swallowed his bilious lies about a woman who has served this country well for decades, ultimately turning against her simply, literally, because she was a woman.

Where the other 47% spent the election

Where the other 47% spent the electionAnd just as significantly, 47% of Americans did not vote at all, clearly deciding that the only reason to vote for a President is if you’d like them enough to invite them to your weekend barbeque. The verbal smear campaigns turned each candidate into cartoon villains in the eyes of half of the public, which then decided they were better off sticking their heads in the sand than voting. By not voting at all, they abdicated their responsibility to be part of the democratic process that is central to this country’s precepts and ideology. There’s a reason that “Of the People, By the People and For the People” is so significant to Americans, and why it’s so tragic when it is forgotten.

By doing so, Americans have openly and globally condemned everything the US has done in the last 75 years, from technological developments, to social improvements, to political systems. And you can expect every effort will be made to turn most of those improvements back, turning quite a significant number of Americans into thieves, monsters, deviants, outcasts, and—probably—corpses.

Clearly, this is not the America I signed up for. It’s not the optimistic, forward-thinking leader of the free world. It’s not the icon of technological progress and seeker of truth. It’s not the protector of the environment. It’s not the receiver of the tired, poor, huddled masses, yearning to be free.

It is the country that has shunned the intelligent science fiction I’ve written for it, in favor of moronic sitcoms and slasher films, Fox News, Star Wars, Harry Potter and porn. It is the country that has decided whatever race I am, it’s not the right one. It is the country that has demonstrated that it would rather spit in my food than welcome me at its table. And half of my country has decided that, when the going gets tough, they would rather hide than act.

In short, it’s a country that I am more afraid of than I’ve ever been in my life.

Tomorrowland is closed for the season. The idiocracy has spoken.

This isn’t my country.

I wish I could say I have no words for what has happened in the USA today.

I wish I could say I have no words for what has happened in the USA today.

Unfortunately, I have quite a few. Only some of which are printable.

Yeah, I get that Americans want change… Americans always want change, because nothing is ever good enough for them. Foreign fears, domestic fears, personal fears… they are always there, at least with 99+% of the people. I also get that America almost never votes in the same political party after an 8-year term. That explains a lot of the election season we’ve just endured.

But it obviously goes far deeper than that. Americans are afraid of their neighbors, and still label people by their skin color. Americans are afraid of their law enforcement—either going too far to protect them, or not going far enough. Americans are afraid of countries they’ve chosen to never try to understand. Americans are afraid of a world that has changed since 1950, apparently the gold standard for an America that was considered G-rated and acceptable to the Andy Griffeth crowd.

And Americans have not only neglected their education, but they’ve spent so much time in front of television that they think reality shows, and their casts, are real people.

This combination allowed the most fearful of us to be taken in by a con man, a cheap carny huckster who knows all about manipulating the TV generation, but nothing about how to run a country. They swallowed his bilious lies about a woman who has served this country well for decades, ultimately turning against her simply, literally, because she was a woman.

By doing so, Americans have openly and globally condemned everything the US has done in the last 75 years, from technological developments, to social improvements, to political systems. And you can expect every effort will be made to turn most of those improvements back, turning quite a significant number of Americans into thieves, monsters, deviants, outcasts, and—probably—corpses.

Clearly, this is not the America I signed up for. It’s not the optimistic, forward-thinking leader of the free world. It’s not the icon of technological progress and seeker of truth. It’s not the protector of the environment. It’s not the receiver of the tired, poor, huddled masses, yearning to be free.

It is the country that has shunned the intelligent science fiction I’ve written for it, in favor of moronic sitcoms and slasher films, Fox News, Star Wars, Harry Potter and porn. It is the country that has decided whatever race I am, it’s not the right one. It is the country that has demonstrated that it would rather spit in my food than welcome me at its table.

In short, it’s a country that I am more afraid of than I’ve ever been in my life.

Tomorrowland is closed for the season. The idiocracy has spoken.

November 7, 2016

The architecture of a Verdant satellite

Maybe it’s due to the political landscape and the upcoming US elections… maybe it’s because of an uncertainty in the future of our ecological state, or a concern that an unexpected meteor could end civilization as we know it… maybe it’s just because people want a fresh start… but it’s become an opportune time for scientists, SF fans and everyone else to discuss the possibilities of living in space.

Maybe it’s due to the political landscape and the upcoming US elections… maybe it’s because of an uncertainty in the future of our ecological state, or a concern that an unexpected meteor could end civilization as we know it… maybe it’s just because people want a fresh start… but it’s become an opportune time for scientists, SF fans and everyone else to discuss the possibilities of living in space.

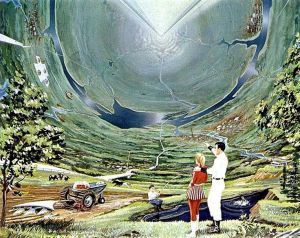

A lot of people have envisioned living in orbiting satellites, either writing novels (like myself), commissioning studies on how to actually do it, or just creating cool artwork about them. The idea is to live more lightly upon the land by putting the populations into a controlled environment off Earth, and incidentally, to give people a haven from environmental disasters. A quick search on Space Habitats will turn up an incredible variety of studies and art, with many different styles of satellites imagined. It’s interesting to compare them to the satellites I envisioned in Verdant Agenda and Verdant Pioneers, and note the similarities and differences.

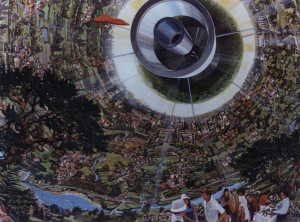

When I first saw Spacehab’s Kalpana One Space Settlement (below left), I realized it had a lot of similarities to my conception of the city-satellites in my novels, most notably the very popular idea of rotating the main structure to simulate a standard Earth gravity on the interior, making sure residents would not suffer the debilitating effects of low- or no-gravity (0-gee) on the human body.

Spacehab’s art also features a central column, running from pole to pole, providing light to the satellite interior. I agree with Spacehab that this is a better idea than the other popular concept of opening mirrors to direct light through massive glass panes to the satellite’s interior: The Sun is simply too intense to give direct (even reflected) access to the interior of a satellite; between the raw energy and the radiation from the Sun’s glare, the interior would be an irradiated hell in no time. Shielding the interior from direct sunlight makes much more sense, and the exterior can be fitted with solar cells to capture all that energy pretty efficiently. And the light pole can be varied in intensity to simulate the natural day and night cycles of Earth, to which all Earth life is strongly accustomed.

Spacehab’s art also features a central column, running from pole to pole, providing light to the satellite interior. I agree with Spacehab that this is a better idea than the other popular concept of opening mirrors to direct light through massive glass panes to the satellite’s interior: The Sun is simply too intense to give direct (even reflected) access to the interior of a satellite; between the raw energy and the radiation from the Sun’s glare, the interior would be an irradiated hell in no time. Shielding the interior from direct sunlight makes much more sense, and the exterior can be fitted with solar cells to capture all that energy pretty efficiently. And the light pole can be varied in intensity to simulate the natural day and night cycles of Earth, to which all Earth life is strongly accustomed.

A significant difference between Spacehab’s design and my concept is the overall length of the satellite: Whereas they envision a can shape, not much longer than it is in diameter, the satellites in the Verdant series are kilometers long, presenting a distinct cylindrical shape. They are more similar in size and shape to the satellites envisioned by Gerard O’Neill’s concepts in The High Frontier. The Verdant satellites are supposed to equal the land mass of a small country, or at least a megacity or two. It would be large enough to require the use of public transportation to cover its significant distances from pole to pole.

The bulk of living in a Verdant satellite takes place on the interior of the outer hull, the main floor. To my satellites I added terraced structures at the north pole, a ring of levels designed to rotate independently of the main floor at certain rates to simulate 1-gee at the lower levels, a fraction of a gee at mid-levels (for those recovering from health issues where a lessened gravity would aid healing), and 0-gee close to the hub (for handling of heavy cargo, and for experimentation and manufacturing that would benefit from 0-gee). Most of the satellite’s control and administrative offices are in this ring of buildings.

The bulk of living in a Verdant satellite takes place on the interior of the outer hull, the main floor. To my satellites I added terraced structures at the north pole, a ring of levels designed to rotate independently of the main floor at certain rates to simulate 1-gee at the lower levels, a fraction of a gee at mid-levels (for those recovering from health issues where a lessened gravity would aid healing), and 0-gee close to the hub (for handling of heavy cargo, and for experimentation and manufacturing that would benefit from 0-gee). Most of the satellite’s control and administrative offices are in this ring of buildings.

In order to maximize space for the populace, I assumed very few would have free-standing private homes, and instead would live in flats of various sizes in common buildings on the main floor. Verdant features an abundance of natural areas, woods and parks, sports fields and lakes, a preponderance of green and open public areas that will encourage outdoor activities and take the edge off of living in a giant cylinder in space. The trees and other greenery will also contribute to the cleaning of the atmosphere, scrubbing carbon dioxide and adding oxygen to the air, as well as providing natural fragrance and supporting some wildlife (including the insects and small critters that help maintain plant life by their activities).

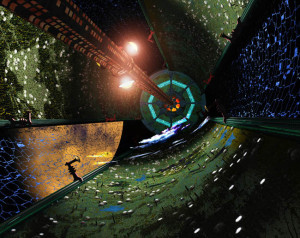

A great deal of spaceship traffic would travel through the hub, taking advantage of 0-gee to move large ships and heavy cargo. Due to the greater size and requisite population, however, the hub could not handle all of the ship traffic and cargo; so I devised a system of scaffolds around the outer hull, designed to move along the hull counter to the satellite’s rotation on tracks, allowing them to capture ships at 0-gee; then the scaffolds would slow on their tracks to match the satellite’s rotation, bringing the ships up to the same 1-gee of the interior, and transfer the ships into docking bays in sub-floors along the outer hull. Being docked at 1-gee would make it easier for passengers to debark and board at normal gravity, and more maneuverable cargo could be loaded by hand. And when ships were ready to depart, they could be taken outside just as they were taken in, or could simply “drop” out of the bay, using the boost from centrifugal force to start them on the way home.

A great deal of spaceship traffic would travel through the hub, taking advantage of 0-gee to move large ships and heavy cargo. Due to the greater size and requisite population, however, the hub could not handle all of the ship traffic and cargo; so I devised a system of scaffolds around the outer hull, designed to move along the hull counter to the satellite’s rotation on tracks, allowing them to capture ships at 0-gee; then the scaffolds would slow on their tracks to match the satellite’s rotation, bringing the ships up to the same 1-gee of the interior, and transfer the ships into docking bays in sub-floors along the outer hull. Being docked at 1-gee would make it easier for passengers to debark and board at normal gravity, and more maneuverable cargo could be loaded by hand. And when ships were ready to depart, they could be taken outside just as they were taken in, or could simply “drop” out of the bay, using the boost from centrifugal force to start them on the way home.

I envisioned Verdant and its sister satellites to be fully independent territories, filled with administrators, residents and businesspeople, trading with businesses on Earth for the essentials and incidentals required for a comfortable life. Verdant was designed to feel as real as possible, so the events in the story would have a real impact for the reader. The detail I put into Verdant Agenda and Verdant Pioneers provided that realism.

Allkey™: Look to the horizon

Company Tech4Use recently released a video of Ōllkē, an “innovative key system” that’s designed to be a one-unit device for everything you own that needs locking or secure storage. It features a control screen that will allow you to lock and unlock things, like a car fob, and also to store digital files as a USB key. And although I admire their innovation and their design, there’s still one area in which they, like so many innovators, are still lacking: They refuse to give up past technology.

Company Tech4Use recently released a video of Ōllkē, an “innovative key system” that’s designed to be a one-unit device for everything you own that needs locking or secure storage. It features a control screen that will allow you to lock and unlock things, like a car fob, and also to store digital files as a USB key. And although I admire their innovation and their design, there’s still one area in which they, like so many innovators, are still lacking: They refuse to give up past technology.

In this case, their innovative key system continues to include a holder for the old-fashioned metal key, the device (along with locks) that we have been using, virtually unchanged, for centuries… and which has given us plenty of time to figure out ways around it.

We should be getting rid of the little pieces of shaped metal that we lug around and stick into shaped holes filled with springs and pins. Metal keys can be lost, stolen, easily copied or mimicked with lockpicks. And the locks themselves can be defeated with lockpicks, stiff plastic cards (I repeat for emphasis: stiff plastic cards!) or good ol’ brute force. It’s a system that can defeat the casual person, but rarely deters or defeats the person who is serious about getting into your stuff.

Scanning the veins and blood flow under your skin is the future of biometric security.

Scanning the veins and blood flow under your skin is the future of biometric security.We have developed better systems, more secure systems, over the last few decades. Instead of an easily copied or spoofed metal key, we can use biometric data, guaranteeing that the one in possession of that biometric data is the only one who should be accessing a secure store. And by biometrics, we don’t just mean an image of a fingerprint or retina scan; modern biometrics can not only make out 3-D images under the skin, but can detect blood flow and actual signs of life, effectively defeating those who apparently watch too many bad espionage thrillers and think they can take a high-definition picture, sever someone’s finger or steal an eyeball and get access to all their stuff using dead body parts.

We can embed that data in a sealed fob the size of a couple of quarters, and add security encryption that would take even an experienced programmer days to hack. In this security-conscious world, we should be replacing all of our metal key systems with more secure systems, whether they use biometric data, or just a heavily-encrypted digital code. Such systems are in use today to admit employees into their workspaces; there is no reason why they can’t be applied to a household.

Here’s how it could work: Everyone would have a private fob (an ALLKEY™, if you will). The best design would incorporate an external sensor that could read a biometric signature, such as a fingerprint (it could store all of your fingerprints, and maybe be unlocked with one or a specific combination of fingers). This one fob would store the digital access codes for everything you own.

It would be programmed by professionals using registered, certified and secured equipment. Say you just bought a car: You would hand your Allkey™ to a certified lock technician at the dealership, who would use their secured equipment to add the car’s access code to the fob (and the fobs of anyone permitted to drive the car). Suppose you’ve also replaced your old lock to your house with a digital lock: A technician at the lock store would use their equipment to encode the door lock to your Allkey™.

Now the one Allkey™ can open your house or your car. One Allkey™ could potentially hold the lock codes to hundreds of locks… no more rings of keys and multiple fobs to carry around everywhere you go. The Allkey™ could be easily secured to your person, or worn on an unobtrusive-looking piece of jewelry, a ring, wristband or necklace. As it can’t be used without your live biometric data, there’s no point to stealing it. If it’s lost, returning it to any registered Allkey™ programmer will allow them to identify the owner and contact them.

All of this has been technologically possible for about a decade, and our need for this has been around far longer. Though I applaud the efforts of companies like Tech4Use, when it comes to security we should be looking beyond the next street and clear to the horizon.