Inga Simpson's Blog, page 6

June 21, 2012

Foxfire

The Finns call the northern lights revontulet, or ‘foxfire,’ after a fabulous mythical fox who swept snow into the air with its tail and ignited it. According to legend, if you talk to the lights, they will come down and snatch you, and if you fail to wear a hat, you might find them clutching at your hair. Clearly, constant vigilance is necessary to survive in the arctic.

The Finns call the northern lights revontulet, or ‘foxfire,’ after a fabulous mythical fox who swept snow into the air with its tail and ignited it. According to legend, if you talk to the lights, they will come down and snatch you, and if you fail to wear a hat, you might find them clutching at your hair. Clearly, constant vigilance is necessary to survive in the arctic.

I picked this up in the travel section of the weekend papers, an extract from Lavinia Greenlaw’s entry in The New Granta Book of Travel. Greenlaw went to the Arctic because she had “lost her imagination.” She found it again there, thanks to long nights and northern lights.

Armchair travelling, too, is good for rekindling the imagination. As we settle in for winter here, in the southern hemisphere, this might be an ideal collection for fireside dreaming. Granta have a fine reputation for publishing quality writing, and for finding a new take on established genres, as they did with a nature writing collection in 2008.

Given the location, I’m sure it is an arctic fox painting the sky green. If I come back as an animal, I would like it to be as an arctic fox; imagine being able to change the colour of your fur to match the landscape!

June 6, 2012

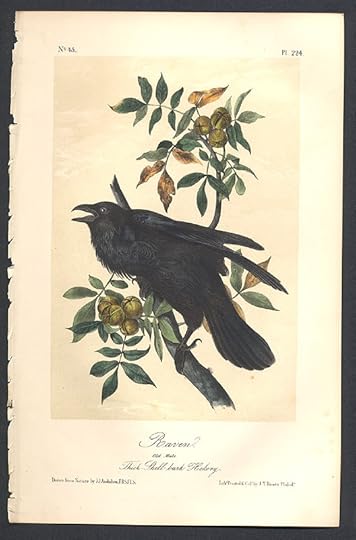

Audubon

[image error]Last but by no means least of the great naturalists who forged a path for nature writing was John James Audubon (1785-1851). He was a colourful character, which is reflected in his illustrations and writings.

The illegitimate son of a French slave trader and his Creole mistress, he arrived in America in 1803 to make a clean start. Mr Audubon was a self-made man; indeed, he almost made himself up. For a time, he ran dodgy financial schemes to make a living. John Keats’ younger brother, George, was caught up in one of these – investing in a sunken steamer – and both Keats and Audubon lost their money.

It was not until 1826 that Audubon made his debut in the artistic community. Over the next ten years his massive The Birds of America was published, with 435 plates. His drawings were criticised by some at the time for their bright colouring but praised for their exact detail and dramatic lifelike representations.

As Michael Branch argues, however, Audubon was also ”a talented writer whose colourful descriptions of life on the frontier deserve a permanent place in our literature… Like Bartram and Wilson, Audubon understood the role of natural historian to be complementary with that of romantic author” (293). Indeed, he cast himself in the role of hero - naturalist and explorer in the wilderness – and his writing is inclined to a little embellishment.

English was not his first language but, as his diaries show, he improved as he wrote. He didn’t often extend to philosophy but his essays, in particular, or ‘Episodes’, demonstrate lovely expression as well as fine observation skills. Above all he got out there in the field, and saw the country and its inhabitants – man and beast – first hand, traipsing all over America. He believed that wild animals should be observed and pictured in their natural habitats. Some of the most impressive pieces are his ‘Bird Biographies’:

Their usual places of resort are the mountains, the abrupt banks of rivers, the rooky shores of lakes, and the cliffs of thickly-peopled or deserted islands. It is in such places that these birds must be watched or examined, before one can judge of their natural habits, as manifested against their freedom… There, through the clear and rarified atmosphere, the Raven spreads his glossy wings and tail, and as he onward sails, rises higher and higher each bold sweep that he makes, as if conscious that the nearer he approaches the sun, the more splendent will become the tints of his plumage (‘The Raven’: 566).

Their usual places of resort are the mountains, the abrupt banks of rivers, the rooky shores of lakes, and the cliffs of thickly-peopled or deserted islands. It is in such places that these birds must be watched or examined, before one can judge of their natural habits, as manifested against their freedom… There, through the clear and rarified atmosphere, the Raven spreads his glossy wings and tail, and as he onward sails, rises higher and higher each bold sweep that he makes, as if conscious that the nearer he approaches the sun, the more splendent will become the tints of his plumage (‘The Raven’: 566).

One of the portraits of Audubon has him posing with a gun and indeed, was rather too keen a hunter; he shot many birds (and other animals) ostensibly in order to study and draw them. This means lots of cringing as you read if, like me, you’d rather all little birdies were all let live. One diary entry, from the 18th October 1870, records “We killed 2 Pheasants, 15 Partridges – 1 Teal, 1 T.T Godwit – one small Grebe … and one Barred Owl…”

Despite his predilection for hunting, Audubon showed early environmental nouse, frequently recording his anxiety for nature’s destruction:

Daily we see so many [Buffalo] we hardly notice them more than cattle in our pastures about our homes. But this cannot last; even now there is a perceptible difference in the size of the herds, and before many years the Buffalo, like the Great Auk, will have disappeared; surely this should not be permitted (341: Mississippi River Journal).

In his essays in particular, Audubon wrote of the “din of hammers and machinery” and “the woods … fast disappearing under the axe … and greedy mills”. He predicted that in a century, the forests would be gone.

Audubon had read and admired Wilson’s Ornithology, which was apparently hard to get at the time. He found fault with it at times, however, suggesting Wilson hadn’t actually seen some species himself, and aimed to better his work. When he met Wilson, although Wilson borrowed some of his paintings, he refused Audubon’s offer of friendship, which suggests a certain smallness of character.

[image error]Audubon’s drawings and writings brought the vanishing American wilderness to a popular audience. He was read with pleasure by Thoreau and John Muir, feeding the emerging writing imaginations of two of the great American nature writers.

Audubon, Wilson and Bartram foregrounded nature and wrote beautifully, blending science and romanticism and elevating natural history writing to literature. Change was on the wing, and the American nature writing tradition waiting not too far off, in the next clearing.

References:

Audubon, John James. Selected Journals and Other Writings. New York: Penguin, 1996.

Branch, Michael. “Indexing American Possibilities: the Natural History Writing of Bartram, Wilson, and Audubon.” The Ecocriticism Reader. Eds. Cheryll Glotfelty, and Harold Fromm.Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996. 52-68.

May 30, 2012

Ironbark (1)

Ironbarks, as their name suggests, are tough trees. Their outer covering is thick, rough and deeply furrowed. Dead bark is not shed but accumulates. As it dies, it is infused with kino, a dark red sap or gum. The kino ensures the bark is impervious to fire and heat, protecting the living tissue within: one of the many fire adaptations of eucalypts.

Ironbarks, as their name suggests, are tough trees. Their outer covering is thick, rough and deeply furrowed. Dead bark is not shed but accumulates. As it dies, it is infused with kino, a dark red sap or gum. The kino ensures the bark is impervious to fire and heat, protecting the living tissue within: one of the many fire adaptations of eucalypts.

It is this infusion of kino that gives the bark its dark colour, almost black. As if the trunks have already been burned. Or belong to another time. In places, deep red oozes through, like blood. Ironbarks grow in tough country, tolerating the dry. Their grey-green narrow leaves, turned sideways to the sun, are one of the features of the Australian landscape that early white explorers and settlers found so dreary and monotonous.

Ironbarks are my heartwood. They cling to the hilltops and paddock edges in the dry land of my childhood, in Central West New South Wales. Much of my family’s property is flat or gently rolling: wheat, cattle and sheep country. Most winters, the paddocks still run soft and green. Ghosts of big old yellowbox linger in the paddocks, dropping limbs.

The countryside was once covered with dense scrub and tall trees. By the 1890s, tree cover had receded to the hills, a part of the property we have always called ‘Up the Back’. It is stony and steep, which makes for poor farming, but thick with ironbarks, cyprus pine, wildflowers and wildlife. It was to these hills I was drawn as a child.

From twelve or thirteen, I camped out alone with the rocks, trees and stars. I would carry in everything I needed – at first on foot and, later, on my motorbike. To reach my campsite, I had to cross the main road and the neighbour’s paddocks, negotiating three difficult gates. The final leg was a tough climb over logs and rocks.

There was a flattish site for a tent and a large stone fireplace, overlooking crop and grazing land; straight boundary fences and lanes transecting the curves of tree-lined creekbeds and ridgelines. After sundown, my ironbark sentinels faded into the dark. The sky was bright and vast, sounds carried from far off, and I could just make out the glow of the next town.

By day I wandered, collecting itchy seedpod boats from beneath kurrajongs to sail on the dam, interrupting mistletoe-infected trees admiring their own reflections. Or sketching the delicate bluebells that appeared, as if from nowhere, in spring and summer. Below my campsite, on the cool side of the hill, there were a handful of boulders. They lay as if scattered by a giant. No matter how carefully I climbed down, the black wallabies thumped away at the first snap of a twig or scrape of my boot, leaving me to explore the ferns and mosses and orchids: a secret world of green.

I am made of ironbark. Formed on hills scraped back to their bones. It is to hills I have returned: a subtropical hinterland thick with trees and loud with birdsong. At first, blinded by chaotic green, I didn’t notice the ironbarks. After heavy rain, I recognised their black trunks standing among the brushbox, tallowwoods, bloodwoods, grey gums, and flooded gums.

These ironbarks are not the straggling things I first knew, eking out a living. They grow dead straight and tall. Saplings shoot up, gangly, competing for light. I cannot see their foliage unless I crane my neck and squint; they are all trunk. A verdigris of lichen clings to their southern sides.

Sometimes I see them with my father’s eye, calculating their diameter, the quantity of timber within, or dimensions of a bowl turned from a cross-section. There is one outside the bay windows of the lounge room, halfway down the slope to the dam, which must be sixty feet tall, and without a branch or blemish until at least thirty-five feet up.

It is by the big ironbarks that I orient myself, get my bearings. There are three around the studio, in a triangle, as if securing it to the slope. From the deck, there is a giant at twelve o’clock, at the end of our ‘garden’, looking towards the mountain range. It is the first tree I see from the loft in the morning, its dark trunk coming into focus before the others.

Australian nature writer, Alec Chisholm, saw something else in the ironbarks on his property, a shadow of its original owners and an expression of the ambivalence we all carry in relation to the Australian landscape:

This was the unhappy case, chiefly, when dusk enveloped the ridges and gullies on dull days in winter. The ironbarks had now shed their friendliness. They were, perhaps, revengeful phantoms of the black men who had once frequented these forests. Especially was I uneasy when passing a spot on a ridge top in which white pipeclay contrasted with the sombre colour of the trees (1964: 64).