Inga Simpson's Blog, page 5

May 2, 2013

first review of Mr Wigg

from Bookseller and Publisher:

Mr Wigg (Inga Simpson, Hachette, July) reviewed by John Purcell

The book that comes to mind on having finished Inga Simpson’s Mr Wigg is Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. They share nothing much in common; Mr Wigg is set in country Australia in 1970, is about a man at the end of his long life, and the most contentious issue touched on is the sacking of Bill Lawry as captain of the Australian cricket team. But even so, that warm feeling that comes from having read something that has strengthened or even reawakened a sense of what is right and good about the world overwhelmed me on closing the book. And also, I suspect, though it isn’t actually true of Mr Wigg, both stories are from the point of view of the child. I know nothing of Inga Simpson, and I may easily have been tricked by her wonderful art, but I think this book is in some way an account of someone, and somewhere, she loved as a young person. Whatever its genesis, Mr Wigg is beautiful. A strange word to use, I know, but it is what it is.

March 7, 2013

March 5, 2013

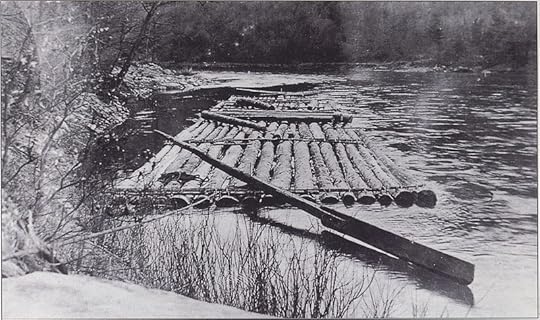

In the Wake of the Raftsmen

A short story of mine, In the Wake of the Raftsmen’, appears in the current volume of the Review of Australian Fiction. I’m featured alongside Mary-Rose MacColl, which is a huge honour. Here’s how it begins …

They lashed the logs together with the vines they had cut from the forest. Laney and Gill held them steady in the shallow water, while she and Dean wound the lengths around, securing each one to the next until nine logs formed a raft. Dean had brought rope, not trusting the traditional methods, but he didn’t take it from his pack. Together, the logs were strong.

It was how the raftsmen had first cleared the forests, dragging and sliding all those cedars and bunyas to the river’s edge and lashing them together to float them to the sawmill.

February 12, 2013

Canberra’s Aboretum

I passed through Canberra recently and visited its newly opened Aboretum. It’s in its infancy, really, the majority of the trees too small to cast much shade. The project has had its detractors: it’s a major investment, features non-natives, and will use plenty of water … but I love it. Forty thousand trees in a hundred forests!

Canberra’s aboretum fills the space once occupied by pine plantation and burnt out ten years ago in Canberra’s bushfires. I lived in Canberra then, though I was away with work at the time. It was worse, if anything, to watch it all on a TV screen, making and receiving worried calls, and unable to get home. My place, in the inner north, was fine in the end, but plenty weren’t, and Canberra was much changed. I used to ride around the lake to Scrivener Dam and fly down a winding section of track through part of that pine forest most evenings in summer. It was one of the best things about living there. I only did that ride once again, to find miles and miles of blackened wasteland. It was lovely to see something new and wonderful growing in its place.

An aboretum was included in the Walter Burley and Marion Mahony Griffin’s original design for Canberra, which they envisioned as a city of trees. So it’s nice to see their plans come into fruition. It’s not quite where they intended, but in a fitting spot, two hundred and fifty hectares with wonderful views over the lake and out to the Brindabella Mountains.

But the point is the trees - ‘every tree has a story’ as the brochure puts it. There are lots of rare and intersting species from around the world, like the Monkey Puzzle, as well as plenty of locals, including the wollemi, bunya and hoop pines, with genetic memories reaching back to the jurassic period.

But the point is the trees - ‘every tree has a story’ as the brochure puts it. There are lots of rare and intersting species from around the world, like the Monkey Puzzle, as well as plenty of locals, including the wollemi, bunya and hoop pines, with genetic memories reaching back to the jurassic period.

The aboretum is to be a centre of tree education and research as well as a tourist attraction.

I took the Himalayan cedars walk and sat by the bbq/picnic area provided, which is high-set and relaxing, catching lovely breezes and views.

The sculptures are a highlight, particularly the eagle’s nest; everything seems to come with a forest and a vista!

I also checked out the visitor’s centre, which is a looks a bit like a giant armadillo rising out of the landscape. Its insides are large-scale timber and steel – gorgeous and high quality. There are tasteful displays with quotes from John Muir and others, talks from Indigenous guides, lots of information about trees and the site, and interactive bits for kids. There’s a bonsai display – one of the best I’ve seen – featuring plenty of Australian natives.

In something of a Canberra public institution tradition, despite getting nearly everything right (except perhaps pay-parking miles from the city) the centre’s cafe is all wrong. With all that space, atmosphere, and dramatic views, it’s poky one-counter service, average everything, and a mile-long queue clogging up the main entrance on a Monday morning, are a joke. My tip: pack a picnic.

Canbera’s aboretum is a work in progress, but what a wonderful vision for the future.

“When we tug at a single thing in nature, we find it attached to the rest of the world.” ~John Muir

January 30, 2013

The Next Big Thing – I answer ten questions

The Next Big Thing is a blog chain where writers answer ten questions about their writing, then tag other writers to do the same. I was tagged by Lisa Walker, the fabulous author of the funny yet heartwarming Sex, Lies & Bonsai and Liar Bird.

1. What is the title of your current book?

Mr Wigg

2. Where did the idea come from?

The name, Wigg, came from an ancestor, a French journalist who fled to England because of some sort of persecution, and then emigrated to New South Wales when things got too hot in London. Initially I had wanted to do something with his story, paralleling it with that of a present-day descendant. I spent some time in rural France, and the village gardens, walled orchards, and whole way of life (based around good fresh food) reminded me of the way my paternal grandfather - a quarter French (Wigg) – tried to live his life in rural NSW, even though he had never been to Europe – as if from genetic memory. ‘Slow food’ and organic gardening was peaking at the time I was travelling, too, and it dawned on me that none of that was really new. The character of another Mr Wigg altogether began to take shape.

3. What genre does your book fall under?

Literary realism, I guess. Though there is a magical element to the story.

4. What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

That’s a bit tough, especially for Mr Wigg himself. Leo McKern would have been good. What about Peter Cundall – he can act, surely? Or perhaps he wouldn’t need to. Robyn Nevin for Mrs Wigg, and for Mr Wigg’s son, maybe Sam Worthington.

That’s a bit tough, especially for Mr Wigg himself. Leo McKern would have been good. What about Peter Cundall – he can act, surely? Or perhaps he wouldn’t need to. Robyn Nevin for Mrs Wigg, and for Mr Wigg’s son, maybe Sam Worthington.

5. What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

Mr Wigg is the story of the final year in one man’s life.

6. Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

Mr Wigg will be published by Hachette in July 2013.

7. How long did it take you to write the first draft?

About a year. Another year to edit and polish.

8. What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

Perhaps Bracelet Honeymyrtle by Judith Fox. It’s most like – and partly inspired by, now that I think of it - a short story by Anna Tambour about a man retreating to the country to grow an orchard of medlar apples, called ‘Valley of the Sugars of Salt’ from Monterra’s Deliciosa & Other Tales &. I had Tim Winton’s Blueback in mind, too, a kind of contemporary fable, but mine’s a long way from the ocean.

9. Who or what inspired you to write this book?

Nostalgia for my grandfather’s home-grown peaches.

10. What else about the book might pique the reader’s interest?

It’s set in rural NSW during the early 1970s, and manages to encompass cooking, cricket, blacksmithing, winegrowing, a magical orchard, and … the colour aqua.

~

I would now like to introduce you to three talented writers to watch:

Melissa Ashley, author of the luscious The Hospital for Dolls (2003), is considered “one of the most promising of a new generation of Australian poets.” Melissa is currently working on a fictional memoir of Elizabeth Gould (bird man John Gould’s undercredited wife), the research for which includes studying taxidermy.

Ellen van Neerven-Currie is an emerging Brisbane writer. Her novel, Hard, was shortlisted for the 2012 Unaipon Award, and her story, ‘S&J’, published in McSweeny’s 41.

Bec Jessen was the winner of the 2012 State Library of Queensland Young Writers Award. Her writing has been published in Voiceworks, Stilts and Rex. She is currently working on a verse novel (inviting comparisons to Dotty Porter!) titled Gap.

Melissa, Bec and Ellen will be posting their answers to The Next Big Thing next week!

Rupetta lives

Nike Sulway’s wonderful novel, Rupetta, about a partly mechanical woman who lives four hundred years, hits the stands next month, published by Tartarus Press, in the UK.

If you don’t know Tartarus, they publish beautifully bound books in the specualtive fiction genre. (Angela Slatter’s short story collection, Sourdough, is also on their list). Get your hands on a hard copy of Rupetta if you can.

The book is beautifully written – sentences to die for – and the story rich with wisdom, historical texture, and gorgeous detail. I have to warn you, though; it’s a little heartbreaking.

Rupetta will be launched at the The Golden Fleece in York, on 9 February, if you are mobile or in the neighbourhood.

Rupetta will be launched at the The Golden Fleece in York, on 9 February, if you are mobile or in the neighbourhood.

You can read an extract here:

And some background about the novel on nike’s website here:

October 31, 2012

Discovering Lauren Groff

David Vann, speaking on a panel at the Brisbane Writer’s Festival in September this year, said that he only reads books which contain beautiful sentences.

David Vann, speaking on a panel at the Brisbane Writer’s Festival in September this year, said that he only reads books which contain beautiful sentences.

I read more widely, up to a thousand pages a week – for my research, work and pleasure. I enjoy it (nearly) all, and get something out of every book, story and essay. I have been trained to read critically, too critically sometimes; even when reading for pleasure, I find it hard not to focus on flaws and faults, and all the things I would have done differently.

I find myself hunting for beautiful sentences. The perfectly executed novel. A book I can actually lose myself in. Works that challenge me, writers who I admire and aspire to emulate in some way. Who raise the bar. The bar I set for myself.

I ‘find’ one or two a year. Who write the sort of books I wish I had written. The sort of books I wish I could live in. I remember the Christmas I discovered Sarah Hall (The Carhullan Army) and Per Petterson (Out Stealing Horses). I read them both on Boxing day: one of the best days of my life. I’ve read those two books – and everything else Hall and Petterson have published – several times since. Vann’s Legend of a Suicide, recommended by at least a dozen people before I read it, was another. In quiet ways, each of these books changed my life.

This week, I discovered a new (to me, anyway) writer I’d put in this category: Lauren Groff. I’ve just finished Arcadia, a gorgeous, intelligent, lightly dystopian novel. It’s beautifully written; the sort of book you find yourself writing down sentences from, or reading aloud (eg. Miles later he slows and sees the island turtling out of the stream). The sort of book where, about half way down the first page, you realise that you are in very safe hands. That you will enter, willingly, this gorgeous fictional world and live it for a while. That is it is a world you want to inhabit, and that you will come out changed.

James Bradley praised Arcadia in his review of another (less successfully executed) novel, and I looked Groff up. I’m not sure how I had managed not to hear of her; she is much lauded and awarded. There is a short story collection, Delicate Edible Birds, in a lovely hardcover, which I ordered for my Nike’s birthday, to justify getting Arcadia for myself.

It is a risk to try and introduce Nike to a new writer: wonderful when it comes off, terrible when it fails. I have made poor choices before; books have been left unfinished. Not mentioned. She read Groff‘s collection in a day (two train trips) and walked in the door raving about it. “So good,” she said. “That woman sure can write.”

Nike put her hand on Arcadia the next morning but I shook my head, despite the sad face she pulled. It had been sitting in a high pile for a while, but I didn’t want it heading out on the morning train; I wanted to read it first. I wanted to share in that thrill of discovery. After all, it was me who found her.

The best part is, there’s more: I still have the short stories to read, and Groff‘s first novel, Monsters of Templeton, A New York Times best seller (!), which I ordered today.

I don’t want to say too much about Arcadia; part of its pleasure is in entering the world of its story, and the surprising, yet inevitable, way it unfolds. The main character, Bit, and Arcadia itself, are with me still.

Here’s the opening paragraph:

The women in the river, singing.

This is Bit’s first memory, although he hadn’t been born when it happened. Still, the road winding through the mountains is clear to him, the rest stop with the yellow flowers that closed under the children’s touch. It was dusk when the Caravan saw the river greening around the bed and stopped there for the night. It was a blue spring evening, and cold.

October 2, 2012

Mr Wigg in the World

I’m thrilled to announce that my novel, Mr Wigg, will be published by Hachette in July this year.

The publication has come about as a result of the 2011 QWC/Hachette Manuscript Development Program, of which I was a finalist. It’s a great program, and I’m thankful not only to Hachette and the team at the Queensland Writers Centre, but to the other talented authors who made our retreat so productive and pleasurable – and have been wonderful support and company since.

What’s Mr Wigg about? Well, it’s about Wigg and his orchard – the final year of one man’s life.

There were stories that the Peach King was a magic tree, older than time. Others said he had once been a great man, ruling over fertile lands and gentle people with a beautiful queen. Whatever the whispers, he was one of them now; his fruit – though a little larger and sweeter – formed just as theirs did.

It’s the summer of 1971, not far from the stone fruit capital of New South Wales, where Mr Wigg lives alone on what is left of his family farm. Mrs Wigg has been gone a few years now but he thinks of her every day. His daughter, too.

Mr Wigg spends his days tending his magnificent orchard, harvesting the fruits of his labours and, when it’s on, listening to the cricket. Things are changing though, with Australia and England playing a one-day match, and his new neighbours, the Traubners, planting grapes for wine.

His son is on at him to move into town – it’s true a few little things are starting to go wrong every now and then – but Mr Wigg has his fruit trees, chooks, and garden to care for. His grandchildren visit often: to cook, eat, and hear his old stories. And there’s a special project he has to finish.

Mr Wigg’s hammer sounded on the anvil like the village bell, each stroke sending off a spray of burning sparks. He beat on, shaping the branches of the tree that had come to him in his dreams.

September 4, 2012

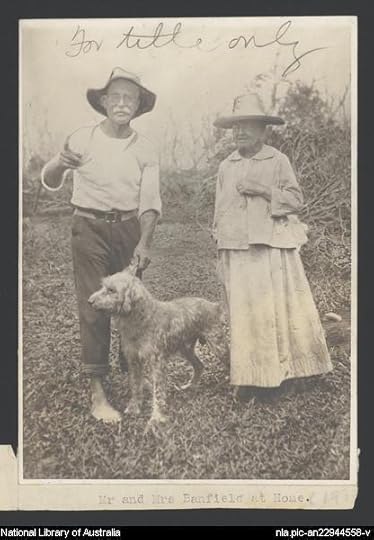

E.J. Banfield: man writes island

One of  Australia’s most significant (and successful) early nature writers was Edmund James Banfield (1852-1923). Born in England, Banfield followed in his father’s footsteps and became a journalist, initially in Melbourne and Sydney but then in Townsville, where he became sub-editor of the Townsville Daily Bulletin. Banfield soon got involved in local politics, too, advocating for the separation of north Queensland as a separate state, arguing that there were two Queenslands: the south, almost entirely within the temperate zone and the north, within the tropics and that the voice of the tropic half was “drowned in the torrent of the temperate” (Confessions, 77).

Australia’s most significant (and successful) early nature writers was Edmund James Banfield (1852-1923). Born in England, Banfield followed in his father’s footsteps and became a journalist, initially in Melbourne and Sydney but then in Townsville, where he became sub-editor of the Townsville Daily Bulletin. Banfield soon got involved in local politics, too, advocating for the separation of north Queensland as a separate state, arguing that there were two Queenslands: the south, almost entirely within the temperate zone and the north, within the tropics and that the voice of the tropic half was “drowned in the torrent of the temperate” (Confessions, 77).

In 1897, Banfield was given three to six months to live. He retreated to Dunk Island, where he recovered and lived for another 23 years. He and his wife, Bertha established a home and planted fruit trees and vegetables. Goats and jersey cattle provided milk, butter and meat. Tom, one of the four remaining descendants of the island’s four hundred original inhabitants – wiped out in clashes with whites – welcomed the Banfields and taught them how to live from produce of island.

Banfield’s accounts of island life, in The Confessions of a Beachcomber (1908), My Tropic Isle (1911), Tropic Days (1918) and Last Leaves from Dunk Island (1925) received popular and critical acclaim in Australia and overseas when they were initially published, prompting comparisons to H.D. Thoreau and Robert Louis Stevenson. Banfield’s exotic location and seemingly idyllic lifestyle – “the absolute freedom of sites uninhabited, shores untrodden” (Confessions: 53) – contributed to his popularity, readers accompanying Banfield on his exploration of:

the states and moods of all the bays and coves of all the isles; the location and form of rocks and reefs; the character of shrubs and trees; the nature of the jungle-covered hilltops; the features of bluffs and precipices; to understand style and manner and conversation of unfamiliar birds; to discover where the turtle most do congregate; the favourite haunts of fishes (Confessions: 53).

Tropical Queensland’s landscape is not that of the stereotypical Australian bush, and has not been as prominent in the national imagination or the canon of Australian literature. While tropical Queensland has tended to be represented, in literature, as either heaven or hell, Banfield showed it was possible to live self-sufficiently, and in harmony with nature. His works chart his growing love for the island, where he is increasingly at home. As the Times Literary Supplement noted in a review of Tropic Days, Banfield “gives the impression of having absorbed its sunshine and seawater until he has become part of it”.

Banfield’s nature writing is based on real lived-in experience of place. As well as Thoreau, critics have compared Banfiedl to John Burroughs and William Henry Hudson, partly for his capacity for close observation and description, like the following garden-like images of the reef: “On the rocks rest stalkless mushrooms, gills uppermost, which blossom as pompom chrysanthemums; rough nodules, boat- and canoe-shaped dishes of coral” (Confessions: 130).

Sydney’s The Daily Telegraph commented that Banfield as fond of solitude as Thoreau pretended to be, though Banfield was far from alone in his island, accompanied of course by his wife, several Aboriginal servants, and as he became increasingly famous, streams of visitors. Banfield was also rather more self-sufficient than Thoreau, and his life in nature more long-lasting.

It is a little ironic that Banfield was such a detailed observer of nature. He had only one eye, the other damaged in a bike accident as a young man and eventually removed after it became infected. His wife, Bertha, was deaf in one ear, and had some sort of trumpet-like hearing aid, which must have made for some comical scenes on the island as they aged.

It is a little ironic that Banfield was such a detailed observer of nature. He had only one eye, the other damaged in a bike accident as a young man and eventually removed after it became infected. His wife, Bertha, was deaf in one ear, and had some sort of trumpet-like hearing aid, which must have made for some comical scenes on the island as they aged.

Banfield was also an early advocate of wildlife protection. The third chapter of Confessions is titled ‘Birds and their Rights’ – at a time when the rights of animals was not at all in our consciousness. He secured protection for birds on the island, preventing any shooting or collecting. The sanctuary was made official by the Queensland government and Banfield an honorary warden.

Banfield died on Dunk Island of peritonitis in 1923. Bertha had to wait, alone, for three days before she was able to flag down a passing steamer. He was buried on the island and a cairn was later built over his and Bertha’s graves. Dunk Island, of course, has since become a resort, which would not have pleased the Banfields, though most of its infrastructure was destroyed during cyclone Yasi in 2010. A campsite and 10km walking track are due to reopen by the end of this month.

Although largely forgotten today, Banfield is one of Australia’s most significant nature writers. He put far north Queensland on the map and introduced Australia’s tropical landscapes, flora and fauna to an international consciousness, particularly the Great Barrier Reef. As the Sydney Mail review of Last Leaves enthused: “… no better, more humane, more finely descriptive, or more enticing books have been written by an Australian of Australia, or, indeed, by any writer of any portion of the earth’s surface.”

August 17, 2012

Winning the 2012 Eric Rolls Nature Essay Prize

I found out recently that the winner of the 2012 Eric Rolls Nature Essay Prize is … me!

The award means a great deal, not just for the recognition of my essay, ‘Triangulation’, in the field of Australian nature writing, but becasue Eric Rolls – sometimes called the Father of Australian Nature Writing for his A Million Wild Acres, They all Ran Wild and many other titles – was born near Grenfell, where I grew up. His books were well-read fixtures in my childhood home, as they are in my own home today.

So, many thanks to the Watermark Literary Society and this year’s judges for the prize. I am really looking forward to the Watermark Literary Muster, in lovely Port Macquarie, 18-20 October, 2013. Perhaps I’ll see some of you there.

You’ll find extracts from the essay in a previous post, Ironbark.