John R. Fultz's Blog, page 67

December 26, 2012

Now’s the Time, the Time Is Now

The official theme song of my holiday–been following me around on the radio waves and describes the scene perfectly. “Such a pleasant stay…”

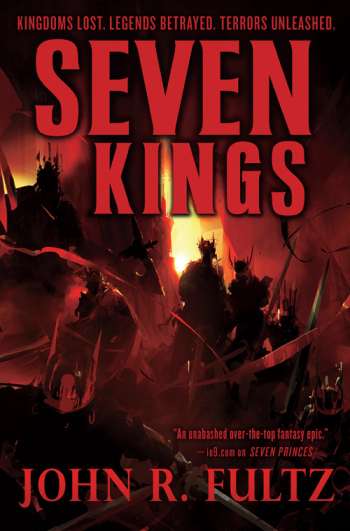

SEVEN KINGS

The Second Book of the Shaper

Available EVERYWHERE — January 15

December 16, 2012

One Month ’til SEVEN KINGS

Only one month until SEVEN KINGS arrives in the US, UK, and Australia. The Second Book of the Shaper hit stores on January 15th, and it takes the series to a whole new level.

Here’s how Orbit describes SEVEN KINGS on their official site:

In the jungles of Khyrei, an escaped slave seeks vengeance and finds the key to a savage revolution.

In the drought-stricken Stormlands, the Twin Kings argue the destiny of their kingdom: one walks the path of knowledge, the other treads the road to war.

Beyond the haunted mountains King Vireon confronts a plague of demons bent on destroying his family.

Iardu the Shaper weaves history like a grand tapestry, spinning sorceries into a vision of apocalypse.

Giants and Men march as one to shatter a wicked empire.

The fate of the known world rests on the swift blades of Seven Kings…

I’ll be doing an official book launch Saturday, January 19 @ 1:00 pm, at Borderlands Books in San Francisco—one of the coolest books stores on the planet. I was lucky enough to do the SEVEN PRINCES launch there last year, and the SEVEN KINGS launch will be even more fun.

If you don’t want to wait until January, Amazon is taking SEVEN KINGS pre-orders right here.

UPDATE: Orbit has posted a free excerpt from the book right here.

December 12, 2012

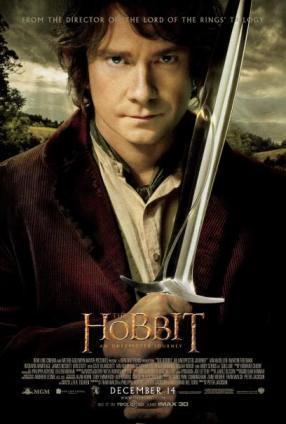

THE HOBBIT: Back to Middle-Earth

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

So it all began.

Peter Jackson’s THE HOBBIT is finally opening this weekend. Jackson is perhaps the only director who could bring J.R.R. Tolkien’s tale of Bilbo Baggins to life as well as Frodo’s tale was adapted in the LORD OF THE RINGS movies. Jackson’s return to Tolkien’s work is the main attraction for me. All the lessons he learned in bringing fantasy’s most beloved trilogy to life on the silver screen should make for an excellent adaptation of Tolkien’s first Middle-Earth novel.

My love affair with the works of Tolkien began in 3rd grade when I read THE HOBBIT. I probably was drawn to the book after seeing the Rankin-Bass animated version of the book on television in 1977. But I remember it was the first book I ever obsessed over, and it lead me eventually to THE LORD OF THE RINGS.

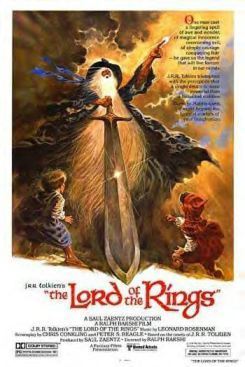

This was also about the time of Ralph Bakshi’s animated LORD OF THE RINGS (1978), which only adapted HALF of the trilogy, but completely blew my mind as a young moviegoer. It transported me directly into Middle Earth and forever influenced my personal view of Tolkien’s world. In order to get the rest of the epic story I had no other choice but to read the books.

There would eventually be an animated TV movie “Return of the King” telling the second half of the story—but I didn’t know that, and I wouldn’t have waited even if I had. I went straight to the books: big, black, gold-trimmed hardcovers that my mother checked out for me from the library of the school where she worked. They had huge, fold-out maps detailing Middle-Earth, and they were the most gorgeous books I’d ever seen—not to mention the greatest thing I had ever read. I didn’t realize how far above my grade level I was actually reading in those days. The story and characters and Middle-Earth itself captivated me, as it did again years later when I re-read the series as a teen, and then again when I read the trilogy for a third time in my twenties.

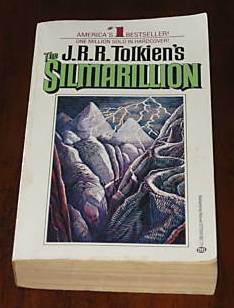

Reading THE HOBBIT and THE LORD OF THE RINGS as a child did not sate my appetite for fantasy. No, it only kindled the flame inside me, and made it burn hotter than ever. I discovered the vast treasure trove of lore that is THE SILMARILLION when I was in the fifth or sixth grade.

I was far too young to read this dense and complex work, but still it enchanted my young mind. I failed to get very far the first two or three times I tried to read it. I’ve heard that same thing from other Tolkien fans. But once you realize that THE SILMARILLION wasn’t a single work, but a combination of various stories, legends, and histories written over the decades of Tolkien’s life, then assembled posthumously by his son after J.R.R. passed away, you begin to realize why THE SILMARILLION is such a challenge. And such a treasure.

To this day my favorite of all Tolkien’s works is THE SILMARILLION, simply because it is the underpinning for all his other major works. The book is entirely unique: You don’t have to read it all in one pass. It’s perfect for reading in part, setting aside for awhile, then coming back to later. There are literally THOUSANDS of years of history and legend and adventure here to keep exploring. The entire history of Middle-Earth is here, as rich and colorful as any set of myth-histories to which you might compare it.

To this day my favorite of all Tolkien’s works is THE SILMARILLION, simply because it is the underpinning for all his other major works. The book is entirely unique: You don’t have to read it all in one pass. It’s perfect for reading in part, setting aside for awhile, then coming back to later. There are literally THOUSANDS of years of history and legend and adventure here to keep exploring. The entire history of Middle-Earth is here, as rich and colorful as any set of myth-histories to which you might compare it.

And that’s where my mind begins to boggle and the uber-fan in me begins to salivate: When I see what a solid job Jackson has done at bringing LOTR and THE HOBBIT into the medium of film, I start thinking about all those amazing stories inside THE SILMARILLION, just waiting for the same treatment. There are several decades’ worth of possible movies in the book. (Especially since movies tend to take so long to make.)

Just a few tales from THE SILMARILLION that would make great movies:

The Creation of Arda

The Chaining of Melkor

The Tragedy of Feanor

The Tale of Finrod Felagund

Beren and Lúthien

Túrin vs. Glaurung

The Children of Hurin

The Fall of Gondolin

The Voyage of Eärendil

The War of Wrath

And there are so many more!

Of course, no movie will ever live up to the sheer pleasure of reading these tales in their original form. The Book Is Always Better Than The Movie. But if there are movies based on Tolkien’s works—and there are bound to be more after THE HOBBIT—then I truly hope the producers, directors, and writers of those movies draw upon the deep store of wonder that is THE SILMARILLION. Meanwhile, there will be three HOBBIT movies to enjoy first. I plan to see the first one this weekend, along with a few million other Tolkien fans and curious moviegoers.

Bring on Bilbo and the Dwarves! Bring on Mirkwood! Bring on Smaug and the Battle of the Five Armies!

Middle-Earth, here we come again…

December 11, 2012

Get your BONES today!

The newest novel by Howard Andrew Jones, BONES OF THE OLD ONES, is finally out in stores today. Jones continues to wrack up impressive reviews and praise from all corners of the fantasy world.

The newest novel by Howard Andrew Jones, BONES OF THE OLD ONES, is finally out in stores today. Jones continues to wrack up impressive reviews and praise from all corners of the fantasy world.

His heroic due Dabir and Asim are once again the stars of his new book, and his Arabian Nights-inspired fantasy puts the sword back in Sword-and-Sorcery. He writes with a deep sense of character, tight plotting, and inventive settings.

BONES is the second book in the Swords and Sands Chronicles—get yourself a copy and thank me later…

Howard’s website can be found right here.

December 5, 2012

Entering THE SIREN DEPTHS

The talented Martha Wells is celebrating the release of her new novel THE SIREN DEPTHS this week. It’s the third volume in her heralded Books of the Raksura series (following The Cloud Roads and The Serpent Sea).

The talented Martha Wells is celebrating the release of her new novel THE SIREN DEPTHS this week. It’s the third volume in her heralded Books of the Raksura series (following The Cloud Roads and The Serpent Sea).

Here’s how Amazon describes the book:

“All his life, Moon roamed the Three Worlds, a solitary wanderer forced to hide his true nature — until he was reunited with his own kind, the Raksura, and found a new life as consort to Jade, sister queen of the Indigo Cloud court. But now a rival court has laid claim to him, and Jade may or may not be willing to fight for him. Beset by doubts, Moon must travel in the company of strangers to a distant realm where he will finally face the forgotten secrets of his past, even as an old enemy returns with a vengeance. The Fell, a vicious race of shape-shifting predators, menaces groundlings and Raksura alike. Determined to crossbreed with the Raksura for arcane purposes, they are driven by an ancient voice that cries out from . . . the siren depths.”

Martha’s blog can be found right here.

December 3, 2012

BONES OF THE OLD ONES: Jones Strikes Again

The great Howard Andrew Jones (Desert of Souls; Plague of Shadows) has a new fantasy novel THE BONES OF THE OLD ONES coming from Thomas Dunne Books next week (Dec. 11).

The great Howard Andrew Jones (Desert of Souls; Plague of Shadows) has a new fantasy novel THE BONES OF THE OLD ONES coming from Thomas Dunne Books next week (Dec. 11).

The book features his trademark pair of adventurers, Dabir and Asim (who were also the stars of Desert of Souls), and promises more Arabian-flavored sword-and-sorcery adventure than you can shake a scimitar at.

Howard is a friend of mine and one of the leading voices of the “new wave” of Sword and Sorcery. He keeps his own blog at www.howardandrewjones.com.

Black Gate.com has posted the first two chapters of the novel online for free reading right here.

November 27, 2012

My Theme Song: “More Human Than Human”

I’d like this song to start playing whenever I walk into a roomful of strangers. Why? Because it’s awesome. And because “I am the astro-creep, a demolition style hell American freak, yeah.”

And because White Zombie rules.

November 26, 2012

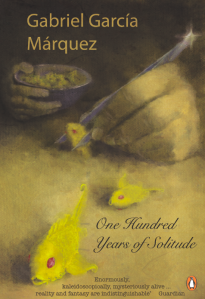

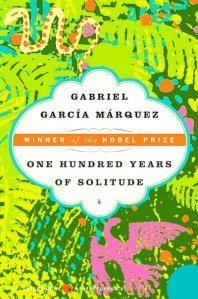

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE: Word Magic

One of the world’s greatest fantasies was published in 1967, won a Nobel Prize, and is still gaining praise and scholarly attention to this day. It was written in the Spanish language and translated into English for American audiences in 1970. The New York Times Book Review said it “should be required reading for the entire human race.” Yes, this is a book of Fantasy I’m talking about…

One of the world’s greatest fantasies was published in 1967, won a Nobel Prize, and is still gaining praise and scholarly attention to this day. It was written in the Spanish language and translated into English for American audiences in 1970. The New York Times Book Review said it “should be required reading for the entire human race.” Yes, this is a book of Fantasy I’m talking about…

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE by Gabriel Garcia Marquez is that book, and I can’t believe I reached the age of 43 before getting around to reading it. Considering the fact that it was published in the US one year after I was born, and that I remember fellow college students reading it in the late 80s, it’s a wonder that I wasn’t drawn to the book sooner. But I have long suspected that the greatest discoveries in life come to us only when we are ready to receive them. Such is the case with ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, which is unlike any book I have read in my entire life.

First, a word about the multi-generational fantasy. This type of fantasy is a story that involves descendants and their ancestors—the lineage of fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, the course of families over the duration of book, or a series. Tolkien’s THE SILMARILLION is perhaps the classic example of multi-generational fantasy, but there are many other fantasy epics that involve the fates of several generations as they unfold. Since we are all part of a generational continuum, these types of tales have tremendous appeal.

First, a word about the multi-generational fantasy. This type of fantasy is a story that involves descendants and their ancestors—the lineage of fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, the course of families over the duration of book, or a series. Tolkien’s THE SILMARILLION is perhaps the classic example of multi-generational fantasy, but there are many other fantasy epics that involve the fates of several generations as they unfold. Since we are all part of a generational continuum, these types of tales have tremendous appeal.

My own Books of the Shaper trilogy is precisely that: A multi-generational fantasy that spans three books, SEVEN PRINCES, SEVEN KINGS, and SEVEN SORCERERS. I plan to write more of this type of generation-spanning tale in the future—something about it is tailor-made for epic and heroic fantasy. Sometimes you get two or three generations in the same book or trilogy. Sometimes, as in the case of THE SILMARILLION, you get hundreds or thousands of years of generations involved with the shaping and history of the fantasy world in question.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE is a staggering achievement that breaks out of all genre classifications, but it is also a solid multi-generational fantasy. It follows the misadventures and exploits of the Buendia family over a period of 100 years, and at the same time it is also the chronicle of Macondo, the remote and mystical town founded by this family. The book chronicles the weird, magical, haunted—and quite possibly cursed—existence of six generations of Buendias. Marquez weaves an enchanting tapestry that reveals the ironic truth of the human condition. Macondo and the Buendia family are a microcosm of the greater world with all its striving, suffering, joyous, weeping, mad humanity.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE is a staggering achievement that breaks out of all genre classifications, but it is also a solid multi-generational fantasy. It follows the misadventures and exploits of the Buendia family over a period of 100 years, and at the same time it is also the chronicle of Macondo, the remote and mystical town founded by this family. The book chronicles the weird, magical, haunted—and quite possibly cursed—existence of six generations of Buendias. Marquez weaves an enchanting tapestry that reveals the ironic truth of the human condition. Macondo and the Buendia family are a microcosm of the greater world with all its striving, suffering, joyous, weeping, mad humanity.

So what makes the book so wonderful? Well, many, many things. At the top of the list is the great and powerful writing, as fueled by Marquez’s fantastic imagination and his keen understanding of the human heart-mind. The imagery that he conjures is consistently amazing, and there is an abiding sense of wonder that overwhelms the reader time and time again—even in the midst of creepy, tragic, or piteous circumstances. Here’s one tiny example of such imagery, which follows the death of the genius/madman and family patriarch Jose Arcadio Buendia:

“A short time later, when the carpenter was taking measurements for the coffin, through the window they saw a light rain of tiny yellow flowers falling. They fell on the town all through the night in a silent storm, and they covered the roofs and blocked the doors and smothered the animals who slept outdoors. So many flowers fell from the sky that in the morning the streets were carpeted with a compact cushion and they had to clear them away with shovels and rakes so that the funeral procession could pass by.”

“A short time later, when the carpenter was taking measurements for the coffin, through the window they saw a light rain of tiny yellow flowers falling. They fell on the town all through the night in a silent storm, and they covered the roofs and blocked the doors and smothered the animals who slept outdoors. So many flowers fell from the sky that in the morning the streets were carpeted with a compact cushion and they had to clear them away with shovels and rakes so that the funeral procession could pass by.”

Although dead, Jose Arcadio Buendia remains part of the narrative as a ghost who haunts his ancestral home—as do so many other characters who persist after death as restless spirits interacting with the living. Indeed, ghosts are essential to the story, and the living characters seem to accept these phantoms as a part of life in Macondo—except for the few who are blind to such wonders.

Overall, the story of the Buendias is an epic that chronicles the dysfunctional existence of an entire line. There is nothing else to compare it to in this respect but the tradition of Gothic Horror, wherein the last remnants of degenerate, inbred noble families persist in isolated, crumbing mansions and madness has replaced common sense. In this respect, ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE is as much about a magnificent haunted house as it is about a mad family and a mystical town doomed to renown and oblivion.

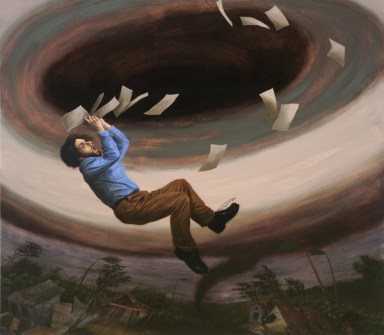

You might say that Marquez has written the South American answer to Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” yet he does not limit himself to the latter hours of this particular house. Instead he takes us all the way from the founding of Macondo—and genesis of the Buendia line—through generations of madness, calamity, adventure, wonder, and depravity, all the way to the very end when Macondo itself is wiped from the earth by a spell one hundred years in the casting. The novel is lyrical and eerie at the same time, with an emphasis on the blurring of the boundaries between life and death, as well as those between love and madness.

You might say that Marquez has written the South American answer to Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” yet he does not limit himself to the latter hours of this particular house. Instead he takes us all the way from the founding of Macondo—and genesis of the Buendia line—through generations of madness, calamity, adventure, wonder, and depravity, all the way to the very end when Macondo itself is wiped from the earth by a spell one hundred years in the casting. The novel is lyrical and eerie at the same time, with an emphasis on the blurring of the boundaries between life and death, as well as those between love and madness.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE is truly “weird” in the best sense of the word, with scads of unexplained miracles and mysterious curses. It is a blend of comedy and tragedy, horror and heroism, hate and love, defeat and triumph. At one point a curse of insomnia falls upon the town of Macondo, and nobody can sleep for months. Decades later a curse of rain begins, and the deluge lasts five years. A third curse is entirely socio-economical, manifesting in the invasion of a totalitarian banana company that dominates Macondo, exploiting its people in ways eerily reminiscent of the Nazi domination of Poland. There is a bloody massacre that everyone is convinced never happened—except for the lone survivor who may or may not be entirely mad. Marquez reminds us that history is written by those in power, and that mass denial can replace actual events, no matter how important or diabolical.

Madness is a common theme, although the definition of what is “mad” lies entirely with the reader. Marquez never makes personal judgments about his characters—even at their worst and most wicked, he simply “reports” what is occurring with an unwavering omniscient viewpoint. Loneliness is another theme, as you might expect from the title; so many of these characters create their own loneliness and misery that you can’t help but feel pity for them. Loneliness and isolation is a form of horror, and several characters meet horrifying fates, often through their own obsessions and refusal to adapt to a world that is changing around them.

Madness is a common theme, although the definition of what is “mad” lies entirely with the reader. Marquez never makes personal judgments about his characters—even at their worst and most wicked, he simply “reports” what is occurring with an unwavering omniscient viewpoint. Loneliness is another theme, as you might expect from the title; so many of these characters create their own loneliness and misery that you can’t help but feel pity for them. Loneliness and isolation is a form of horror, and several characters meet horrifying fates, often through their own obsessions and refusal to adapt to a world that is changing around them.

The original crime of the Buendia family was breaking an ancient taboo, and history repeats itself throughout the book. In fact, the idea of cyclical history is another major theme that Marquez deals with here. Yet only one or two of his wisest characters realize that old behaviors, tragedies, and mistakes keep happening over and over again. Madness or simple ignorance? The reader must decide, as Marquez never preaches. He only reveals the sordid, surreal, and often stupefying events of the bizarre-yet-traditional Buendias and the hapless folk of Macondo.

The characters Marquez creates are worthy of the best Greek tragedies. Chief among them is Colonel Aureliano Buendia, a miserable revolutionary who spends his life fighting pointless wars and never truly understanding why. Some consider him a hero, others a villain, yet only the reader knows the true depths of his sin and suffering. Marquez sums up the colonel’s life in this chapter-opening paragraph, before going into details about all of what he reveals:

“Colonel Aureliano Buendia organized thirty-two armed uprisings and he lost them all. He had seventeen male children by seventeen different women and they were exterminated one after the other on a single night before the oldest one had reached the age of thirty-five. He survived fourteen attempts on his life, seventy-three ambushes, and a firing squad. He lived through a dose of strychnine in his coffee that was enough to kill a horse. He refused the Order of Merit, which the President of the Republic awarded him. He rose to be Commander in Chief of the revolutionary forces, with jurisdiction and command from one border to the other, and the man most feared by the government, but he never let himself be photographed. He declined the lifetime pension offered him after the war and until old age he made his living from the little gold fishes that he manufactured in his workshop in Macondo. Although he always fought at the head of his men, the only wound that he received was the one he gave himself after signing the Treaty of Neerlandia, which put an end to almost twenty years of civil war. He shot himself in the chest with a pistol and the bullet came out through his back without damaging any vital organs. The only thing left of all that was a street that bore his name in Macondo.”

“Colonel Aureliano Buendia organized thirty-two armed uprisings and he lost them all. He had seventeen male children by seventeen different women and they were exterminated one after the other on a single night before the oldest one had reached the age of thirty-five. He survived fourteen attempts on his life, seventy-three ambushes, and a firing squad. He lived through a dose of strychnine in his coffee that was enough to kill a horse. He refused the Order of Merit, which the President of the Republic awarded him. He rose to be Commander in Chief of the revolutionary forces, with jurisdiction and command from one border to the other, and the man most feared by the government, but he never let himself be photographed. He declined the lifetime pension offered him after the war and until old age he made his living from the little gold fishes that he manufactured in his workshop in Macondo. Although he always fought at the head of his men, the only wound that he received was the one he gave himself after signing the Treaty of Neerlandia, which put an end to almost twenty years of civil war. He shot himself in the chest with a pistol and the bullet came out through his back without damaging any vital organs. The only thing left of all that was a street that bore his name in Macondo.”

One of the novel’s few flaws is exemplified in this description of its most perplexing character. Marquez writes the entire book in extremely large paragraphs. Most (but not all) of his paragraphs range from one to two pages in length. As the majority of the story is told in exposition rather than dialogue, this can be challenging for modern readers used to short, succinct paragraphs. This isn’t necessarily a “weakness,” in the novel itself, but more of a consistent challenge for the reader. (There is even a SINGLE SENTENCE at one point that is TWO PAGES long—obviously crafted this way for the precise effect that it creates.) It is a testament to the quality of Marquez’s writing that he draws the reader headlong through these massive paragraphs by delivering such a hypnotic narrative.

Another quality that may challenge today’s readers is Marquez’s tendency to narrate forward and backward through time; although the overall story is linear, moving from the first generation of Buendias to the last, the author jumps around inside characters’ individual lives, reminding you that HOW events happened is often more important than WHAT happened. Another common technique Marquez uses is to reveal a major plot point, then make you wait many chapters for the details. For example, on the very first page of the book he tells you that Colonel Aureliano Buendia will one day face a firing squad—yet at this point the character is only a small boy. This is a way of tantalizing the reader that may at first frustrate but ultimately fascinates.

Another challenge to readers is the manner in which various characters bear identical names from generation to generation, resulting in occasional confusion about which character is which. For example, Jose Arcadio Buendia is the father of Colonel Aureliano Buendia, who has seventeen sons named Aureliano. Meanwhile, Jose Arcadio is the father of Arcadio, who then becomes the father of Jose Arcadio Segundo and Aureliano Segundo. And these are just the MALE characters.

Another challenge to readers is the manner in which various characters bear identical names from generation to generation, resulting in occasional confusion about which character is which. For example, Jose Arcadio Buendia is the father of Colonel Aureliano Buendia, who has seventeen sons named Aureliano. Meanwhile, Jose Arcadio is the father of Arcadio, who then becomes the father of Jose Arcadio Segundo and Aureliano Segundo. And these are just the MALE characters.

The mind does indeed boggle at times, and yet the ongoing pattern of obsessions, adventures, and tragedies cycle through the Buendia family in such a way that WHAT happens is actually more important than WHO it happens to. The reader must be able to “sit back and enjoy the ride.” However, the Buendia Family Tree chart in the front of the book does help to keep the names and the lineage straight. This repetition of names is symbolic of how history repeats itself in ironic and tragic ways, which plays out in the lives of these characters.

Marquez never avoids challenging his reader in these and other subtle ways. Often he references previous story points without giving the reader any reminder of their details. In this way he is almost daring you to remember all the labyrinthine details of the storyline. Unless you have photographic memory, you probably won’t remember everything. Yet this effect only adds to the book’s raw sense of wonder and the effect of being overwhelmed by history.

The Buendia clan is composed of larger-than-life personalities, yet they are also completely believable and ultimately unforgettable. Ursula Iguaran is the indomitable matriarch who holds the entire family together for generations, raising most of children in the absence of their distracted, obsessed, or otherwise absent parents. Remedios the Beauty possesses an exquisite loveliness that is exceeded only by her simplemindedness. Fernanda del Carpio eventually replaces Ursula’s benign presence with her own neurotic madness, infesting the ancestral home with pretense and ruining the lives of everyone around her.

The Buendia clan is composed of larger-than-life personalities, yet they are also completely believable and ultimately unforgettable. Ursula Iguaran is the indomitable matriarch who holds the entire family together for generations, raising most of children in the absence of their distracted, obsessed, or otherwise absent parents. Remedios the Beauty possesses an exquisite loveliness that is exceeded only by her simplemindedness. Fernanda del Carpio eventually replaces Ursula’s benign presence with her own neurotic madness, infesting the ancestral home with pretense and ruining the lives of everyone around her.

Of all the compelling, disgusting, disturbing, pitiable, and captivating characters, perhaps the most mysterious of all is Melquiades the Gypsy, a wizard whose obscure sorcery transcends space and time. Melquiades is not a member of the Buendia family, but a friend to its progenitor Jose Arcadio Buendia. The magician is there from the start, leading his carnival band of gypsies into Macondo to display wonders of magic and science (which often blend together). In his old age, Melquiades comes to inhabit the Buendia household, where he begins writing obsessively, filling parchment after parchment with his indecipherable scrawl until the day he dies.

Melquiades can be seen as an analogy for the author himself, or for all authors, who weave their magic with the tools of language, but his presence in the narrative goes even deeper. For generations certain members of the Buendia family obsess over the writings of Melquiades, attempting to decipher their encoded secrets. Often they are guided by the ghost of Melquiades himself, whose spirit resides in a timeless room in the Buendia house.

The invisible presence of Melquiades is felt throughout the book, and his arcane wisdom shapes both the past and future of the family. Melquiades deserves a place among the all-time great wizards of fantasy fiction, right up there with Gandalf, Merlin, and Prospero. The secret of the Melquiades’ manuscript is ultimately revealed to the last member of the family line, the tormented and despairing Aureliano (the 21st of that name).

The invisible presence of Melquiades is felt throughout the book, and his arcane wisdom shapes both the past and future of the family. Melquiades deserves a place among the all-time great wizards of fantasy fiction, right up there with Gandalf, Merlin, and Prospero. The secret of the Melquiades’ manuscript is ultimately revealed to the last member of the family line, the tormented and despairing Aureliano (the 21st of that name).

There are so many stories told in this novel that its plot cannot truly be summarized. It must instead be experienced. Some of the characters will be seen as downright evil, others as tragic heroes, but Marquez presents them all with the same detached sense of objectivity. All of them are complex creatures, even in the depths of their own idiotic or brutish behavior. Marquez weaves a tapestry depicting everything that is laughable and lamentable about humanity. He makes some important statements about history, civilization, and the nature of the human soul, but you have to read closely or you might miss them. In fact, the book is perfect for multiple readings, offering several layers to explore, which is one reason why it is still celebrated and analyzed decades after its release.

It has been said that the only true themes in literature are Love and Death. Yet when you explore either of these concepts in depth, you find a house of mirrors, a chamber of infinite echoes, an endless variation on the duality of the human condition. Perhaps this is why Marquez, on the last page of ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, refers to Macondo as “the city of mirrors (or mirages).” What we see reflected herein are the spirits of our ancestors, ourselves, and our descendants.

It has been said that the only true themes in literature are Love and Death. Yet when you explore either of these concepts in depth, you find a house of mirrors, a chamber of infinite echoes, an endless variation on the duality of the human condition. Perhaps this is why Marquez, on the last page of ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, refers to Macondo as “the city of mirrors (or mirages).” What we see reflected herein are the spirits of our ancestors, ourselves, and our descendants.

In fact, the book may be a primer on what we’ve done wrong thus far in the history of humanity. A warning cry that offers us a chance to do something better next time, to wake up and understand ourselves and our inherited failings, to learn the lessons of history so we can break the curse of repetition. This book is an examination of humanity’s frailty through the lens of a magical world bursting with overlooked and ignored treasures. As the best art always does, it teaches us something about ourselves, and it does this by wrapping us in the ancient and magical spell of Story.

The work of Gabriel Garcia Marquez has often been called “magical realism,” but that term doesn’t quite describe the depth of his creation. There is magic here, and there is realism, as well as psychological depth, but the final product is far greater than the sum of these parts.

The work of Gabriel Garcia Marquez has often been called “magical realism,” but that term doesn’t quite describe the depth of his creation. There is magic here, and there is realism, as well as psychological depth, but the final product is far greater than the sum of these parts.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE proves that Fantasy Fiction can be every bit as important and enlightening as non-fantasy works of literature, whether they be classified as Realistic, Romantic, Journalistic, or any other label the world cares to apply. It is an immersive reading experience that defies genre classifications while spanning the gaps between fantasy, horror, adventure, comedy, tragedy, and romance.

It is a bizarre and wonderful journey that readers will never forget.

And for writers, it is pure inspiration, both vital and transcendent.

November 15, 2012

SEVEN KINGS: Two Months

Only two months from today until the worldwide release of SEVEN KINGS.

Amazon is taking pre-orders right here.

Below is an early preview of the UK version’s front and back covers

(click image to enlarge).

November 8, 2012

Seven Songs for SEVEN PRINCES

The ever-cool Nathan Long is celebrating the release of his new book SWORDS OF WAAR, the sequel to last March’s JANE CARVER OF WAAR.

The ever-cool Nathan Long is celebrating the release of his new book SWORDS OF WAAR, the sequel to last March’s JANE CARVER OF WAAR.

Jane Carver is a “hard-ridin’, hard-lovin’ biker chick and ex-Airborne Ranger” who is transported to the alien planet known as Waar, “a savage world of four-armed tiger-men, sky-pirates, slaves, gladiators, and purple-skinned warriors in thrall to a bloodthirsty code of honor and chivalry.” The series is both a tribute to and a parody of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ JOHN CARTER OF MARS books. But Carter never looked so dang sexy battling four-armed aliens. (BTW, I adore the Dave Dorman covers on both these books!)

In a blog post today, Nathan did something pretty nifty—he posted a “playlist” for his Harley-riding, sword-swinging heroine. Check out his post and Jane’s playlist here.

This has inspired me to create a playlist for the Books of the Shaper trilogy, beginning with SEVEN PRINCES.

This has inspired me to create a playlist for the Books of the Shaper trilogy, beginning with SEVEN PRINCES.

Now, while Nathan’s list of tunes is meant to represent “the songs Jane would be blasting as she headed out on the open road on her big ‘ol Harley,” the SEVEN PRINCES playlist is more about songs that capture the mood and atmosphere of the First Book of the Shaper.

So here we go—Seven Songs for SEVEN PRINCES:

The Sword – “Barael’s Blade”

Monster Magnet – “Cage Around the Sun”

Kyuss – “Gardenia”

Danzig – “Bound By Blood”

Led Zeppelin – “Kashmir”

Black Sabbath – “Lord of this World”

Judas Priest – “Beyond the Realms of Death”