Centre for Policy Development's Blog, page 43

October 26, 2015

Ian McAuley reviews the Future Business Council’s new report “The next boom: a surprise new hope for Australia’s economy?”

What could be a more reasonable basis for public policy than striking a “balance” between protecting the economy and the environment?

Our government must do something about climate change (we don’t want to look bad at the Climate Change Conference in Paris later this year), but in these times of economic uncertainty, with a possible recession looming, we cannot afford any more misadventures like a carbon tax and we must protect jobs in our local industries. That’s how the story goes.

Underlying that presentation of “balance” is the idea that there is some inevitable tradeoff between “the economy” and “the environment”. Under Tony Abbott, that’s how the Government framed it, and the Labor Opposition. Many who would call themselves “environmentalists” buy into the same idea, asserting that economic growth is the path towards destruction of the planet.

The idea of “balance” seems so reasonable, so appealing to those who want to come across as non-partisan, but it is a poor substitute for clear thinking. Is there inevitably such a tradeoff?

At first sight, there is. As Naomi Klein and many others point out, economic growth based on indiscriminate depletion of non-renewable natural resources (particularly the capacity of our atmosphere to shield the planet from global warming) is not sustainable.

But that’s only one pattern of economic growth – a pattern exemplified by Australia’s economic model as an Asian quarry. In fact, it’s only a quirk of national accounting that allows such an economy to record strong “growth”, because the cost of resource depletion is not brought into account.

We can have a strong and growing economy based on sustainable resource use. In fact the investment in making the transition to such an economic structure may be just the sort of measure we need to get us out of our current doldrums.

The Future Business Council shows us what that new economic structure may look like in its report The Next Boom – a surprise new hope for Australia’s economy?

It’s an optimistic but realistic work, helping us not only to re-shape our imagination of a future economy, but also to see that environmentally sustainable industries are already on a strong growth path.

We need only to wander around the suburbs to see the proliferation of rooftop photovoltaic installations and to drive in the countryside to see the wind turbines feeding into the grid. As the report shows, with hard figures and graphs, this growth has been from virtually a zero base at the beginning of this century.

Less obvious are energy-saving and water-conserving developments. Our dishwashers and refrigerators have become much more energy-efficient. The cars we buy in 2015 emit 25 per cent less CO2 per kilometre than the cars we bought in 2000. Our toilets, showers and washing machines use much less water than they did in earlier times.

And that’s all without any loss in our enjoyment of a hot shower, clean clothes or other comforts. Of course we have to go a lot further than we have come so far, but the message to draw from the FBC’s work is that saving the planet doesn’t require us to revert to a Palaeolithic life style.

Even less obvious are developments in production efficiencies. To take one industry as an example, steel production now uses just over half the amount of water per tonne that it required in 2001, and its use of recycled content has risen from 8 per cent to 33 per cent over the same period.

The report goes into explanations for these developments. The tumbling cost of photovoltaic panels is one obvious factor. Consumer demand is another. For example we pay attention to energy star ratings and similar information.

It’s not clear whether this simply reflects a rational concern to save utility bills or a strong concern for the environment, but some evidence for the latter has emerged with the Volkswagen scandal (which emerged after the FBC’s report was completed). Owners of VW diesel vehicles have suffered no personal cost as a result of the deception, but they have learned that they have been causing much more pollution than they had believed. If we were members of the species homo economicus, indifferent to all but our self-interest, that wouldn’t matter to us. But owners of VW diesel cars are understandably furious because they do care. There is support for the FBC idea that a sizeable number of consumers are willing to pay a premium for environmentally friendly goods.

The strongest explanations for these developments lie in government policies. A number of graphs in the report show dramatic turning points associated with policy initiatives, such as renewable energy targets. One of the most telling graphs shows rapid build-up in investment in large-scale clean energy following the introduction of carbon pricing and the 88 per cent drop when carbon pricing was abolished in 2014.

Of course some will say government intervention interferes with market forces, but that argument ignores the ways markets actually operate. Markets often need a nudge – sometimes a very strong nudge – to get them operating well.

For example, the decision whether one should buy an incandescent or an LED lightbulb should be a no-brainer, because, viewed as an investment decision, the relative return on an LED is around 80 to 150 per cent – it would be better to get a payday loan than to buy an incandescent bulb. But people needed the nudge in the form of Minimum Energy Performance Standards and eventually prohibitions to push them in that direction. Similarly the National Australian Built Environment Rating System has helped building owners and tenants alike become more conscious of the financial benefits of energy-efficient buildings.

As an engineer and industry analyst I found the FBC’s work convincing, but I wanted to return to the central question about action on climate change and economic growth. What has been the experience of other countries?

It is heartening to read in Tim Flannery’s Atmosphere of Hope (Text Publishing 2015), for example, that greenhouse gas emissions are decoupling from economic growth. But I was curious to see what’s been happening over the 25 years since 1990, when the IPCC made its First Assessment Report on Climate Change. What has been the experience of industrialised “developed” countries? Were there countries that had grown while reducing CO2 emissions?

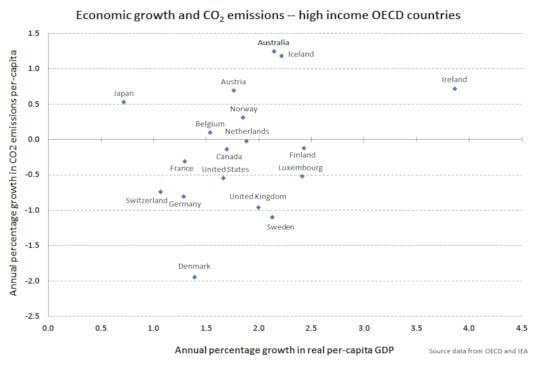

Using the 18 OECD countries with per capita incomes above $US35,000 (the same set as Miriam Lyons and I used in our work Governomics), I was somewhat disappointed. Those countries with higher emissions also enjoyed higher economic growth.

But there is an intervening variable – population growth. When I look at the relationship on a per capita basis, all that remains is a broad scatter diagram (see chart below). With the exception of Japan and Ireland, outliers on the low and high side, all countries have enjoyed per-capita growth between 1.0 and 2.5 per cent a year, and there is no evidence of a relationship between emissions and growth. A majority of countries – 11 out of the 18 – have enjoyed growth without increasing emissions. And, at the top of the pack for increasing emissions, but not for economic growth, is Australia.

The FBC policy agenda is about shifting us down to the other side of the axis, to sit alongside industrialised countries like Switzerland and Germany. They point out that there are opportunities waiting to be exploited, but will we miss the boom? They write:

“Australia has a once in a lifetime opportunity to not just catch the boom but lead it, however we need to implement the right incentives for business now.

Catching the boom will require a step change in Australia. Sustainable innovation was once seen as primarily a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) compliance consideration. No longer. In light of the clear trends here and overseas, it must now be seen for what it is – a growth opportunity and a magnet for investment.

Government has a critical role to play in creating the right market conditions for the growth of innovative sustainable business in Australia.”

Critics may accuse the FBC of “picking winners” (as if that’s a public policy atrocity). In fact, in its emphasis on establishing the right market conditions, its approach is quite the opposite. The market is there, and it’s up to governments to make sure they don’t get in the way.

Rhetoric aside, government policy, sometimes by design, sometimes by accident, has always favoured particular industries over others. Our decision to discontinue carbon pricing, I (and many others) argue, is no less an industry subsidy than a tariff or direct budgetary payment, for it gives firms free access to a scarce commodity, to the disadvantage of competing firms. Our decision to give concessionary capital gains tax treatment to short-term speculation while penalizing long-term investment has been to the benefit of the finance sector and at a cost to long-term investment (such as renewable energy).

The report makes a number of recommendations, many of which are about setting standards so as to provide certainty to producers and consumers, and others on the side of reducing red tape impediments to new industry development. The general theme of the report is about getting prices right (for example of greenhouse gas emissions and waste materials) and making sure nothing stands in the way of new markets developing.

Most notably, when we have been so conditioned to reading submissions from business organisations seeking extension of some unjustifiable privilege, or proposing that the path to prosperity lies in cutting wages and removing all regulations (other than those that protect economic rents), it’s refreshing to hear from a business organisation with a positive, optimistic vision.

Ian McAuley is a CPD fellow, and co-author of Governomics: Can we afford small government?

The post Ian McAuley reviews the Future Business Council’s new report “The next boom: a surprise new hope for Australia’s economy?” appeared first on CPD.

October 25, 2015

CPD roundtable with Ross Garnaut, Robyn Eckersley and Fergus Green on the path to, and beyond, COP21

On 21 October, CPD was delighted to convene a roundtable between some of Australia’s leading climate policy experts to discuss the state of play as we head towards the 2015 Paris Climate Conference (COP21).

The roundtable was moderated by CPD CEO Travers McLeod, and co-hosted by ANU in Melbourne. It featured contributions from Professor Ross Garnaut (Professorial Research Fellow in Economics, University of Melbourne), Professor Robyn Eckersley (Head of Political Science, University of Melbourne), and Mr Fergus Green (Policy Analyst and Research Advisor to Professor Nicholas Stern), and a broader discussion between a range of academic, business, NGO and government participants.

In his presentation, Professor Garnaut emphasised that major developments in projected emissions growth in the United States and China have radically changed the outlook for international negotiations. Emissions had peaked in the US as early as 2007. China’s shift away from investment-led growth and focus on renewables – motivated in part by concerns about air pollution and increased understanding of the longer-term implications of climate change – could see its emissions peak in 2020 or sooner. This radical and sustained change in emissions growth in China made the 2 degree target possible. Together with developments in US, this has established a much more favourable dynamic for international negotiations, and for maintaining momentum toward more ambitious abatement targets around the world.

Professor Eckersley, who is conducting a four-year study into the negotiations shaping the international climate regime under a grant from the Australian Research Council, said that the tone and ambition of ‘Intended Nationally Determined Commitments’ (or INDCs) varied significantly from country to country. While potential flash-points remained, domestic political roadblocks to more ambitious targets were weakening – thanks to the switch in emphasis away from legally-binding commitments, and to growing pressure for stronger policies at home thanks to the ‘show and tell’ process that was happening internationally. The key challenge for the Paris meetings is to design an agreement that can build in upward ratcheting ambition over time – and a review process to ensure that the INDCs have countries on track to meet post-2020 targets.

Fergus Green said the costs and benefits of action on climate change are becoming much more favourable over time – and that this would reinforce more ambitious policies domestically, and therefore greater cooperation at the international level. Recent work at the Grantham Research Institute had found that the vast majority of cuts needed to decarbonise the global economy could be done in ways that deliver domestic benefits that far outweigh the costs for individual countries, even before the risks and costs associated with avoided climate change were factored in. Costs for renewables would continue to shift down over time as their scale expanded and renewables-centered transport and distribution systems grew. There were also major non-climate benefits of action – not only in areas like improved air quality and energy security, but also through opening up new areas of comparative advantage and through the large spillovers associated with knowledge-intensive renewables technologies.

CPD would like to thank the roundtable participants for an excellent discussion, and extend special thanks to Gareth Evans and ANU for co-hosting the event.

To read more from the roundtable participants:

Ross Garnaut: ‘Australia: Energy Superpower of the Low-Carbon World‘, 2015 Luxton Memorial Lecture, University of Adelaide, June 2015.

Robyn Eckersley: ‘Anthropocene raises risks of Earth without democracy and without us‘, The Conversation, April 2015.

Fergus Green: ‘Nationally self-interested climate change mitigation: a unified conceptual framework‘, Grantham Research Institute, LSE, July 2015.

Rodney Boyd, Fergus Green and Nicholas Stern: “The road to Paris and beyond“, Grantham Research Institute, LSE, August 2015.

The post CPD roundtable with Ross Garnaut, Robyn Eckersley and Fergus Green on the path to, and beyond, COP21 appeared first on CPD.

October 22, 2015

The Two Admirals: rare insight from world experts on climate security

CPD’s report The Longest Conflict highlighted the significant impacts that a changing climate will have on Australia’s human security, including how it will affect our defence force and their ability to respond to scenarios at home and abroad.

In this video recorded at the time of the report’s launch, two of the world’s experts and chief advocates on climate security – former Australian Defence Force Chief Admiral Chris Barrie and former UK Climate and Energy Security Envoy, Rear Admiral Neil Morisetti – discuss their personal journey in understanding climate security. Admirals Barrie and Morisetti discuss how they were convinced about the seriousness of the threat, identify some of the key risks ahead of us, as well as advocate for immediate policy action by Australia and its allies and partners.

Admirals Barrie and Morisetti have almost 80 years of military experience and international security between them. They are two global leaders on the profound effects of climate change. Their perspectives, analysis and insight contribute significantly to this critical national discussion.

The video is licensed using the Creative Commons Licence: Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives CC BY-NC-ND http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

The post The Two Admirals: rare insight from world experts on climate security appeared first on CPD.

October 12, 2015

First Regional Dialogue meeting on Forced Migration in the Asia-Pacific

The first meeting of the Dialogue took place in late August, and the second meeting has been scheduled for early 2016.

Read below for a statement from Dialogue members and links to the background papers, participant profiles and the agenda.

A Track II Dialogue on Forced Migration in the Asia‑Pacific was held in Melbourne from 24-25 August.

Dialogue members are from Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and Australia, as well as the offices of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the International Organization for Migration.

Dialogue members will meet in person at least six times over the next three years, with the first three meetings to take place in Melbourne, Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur. Discussions will be conducted under the Chatham House Rule.

Dialogue members have come together to discuss improved policy responses to those forms of migration within, and into, the Asia-Pacific region, which are proving the most difficult for governments to manage. These migratory movements involve people in the most vulnerable of circumstances and raise complex challenges within national communities – the movement of asylum seekers, refugees and trafficked persons.

Dialogue members believe any discussion of ‘forced migration’ must cover, to a greater or lesser extent, related issues such as protection, durable solutions, irregular migration (whether by land or sea), economic migration, migrant smuggling, trafficking, statelessness and displacement. When considering these issues, Dialogue members will look at the capacities, policies and standards and regional structures necessary to respond more effectively.

Ultimately, improved policy responses can only come from governments. New responses at the national level require better understanding of, and insights into, the issues. They also require a commitment to better policy and law and greater investment in data and implementation capabilities.

Effective regional responses to forced migration must flow from a commitment from governments to improved consultative and decision-making mechanisms and, most of all, a sense of mutual trust.

Dialogue members believe no country in the region can unilaterally and satisfactorily address the escalating challenges posed by forced migration. They require regional cooperation, shared responsibility and distributed capacities.

Dialogue participation may change and grow. Broader engagement with individuals and organisations from Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Australia will be sought over time, as well as new members from civil society, other countries in the region and international organisations operating within it.

By meeting regularly, Dialogue members will seek to cultivate collaboration and creativity, forge deeper regional perspectives, develop trust and build commitment to the overall process. Where appropriate, ideas generated will be submitted to individual governments and regional organisations.

The Centre for Policy Development (CPD) is convening the Dialogue, with support from the Sidney Myer Fund, Planet Wheeler Foundation, Vincent Fairfax Family Foundation, Corrs Chambers Westgarth and individual donors.

To see the participants profiles for the first meeting click here.

To see the full agenda for the two-day Dialogue click here.

To view the briefing document for the first Track II Dialogue click here.

To find out more about the rationale behind the Track II Dialogue process click here.

Dialogue members in discussion during the Melbourne meeting

Travers McLeod with Paris Aristotle AM (Foundation House), Kirsty Allen (Sidney Myer Fund), Mark Cubit (Planet Wheeler Foundation) and Marcus Fazio (Planet Wheeler Foundation)

Bob Douglas AO (Australia21), Mohammad Ali Baqiri and Dato’ Steve CM Wong (Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia)

The post First Regional Dialogue meeting on Forced Migration in the Asia-Pacific appeared first on CPD.

October 8, 2015

Travers McLeod: Does apathy to the political system among young people point to a crisis in Australian democracy? | Meanjin, Spring 2015

The good ship of democracy is entering into uncharted waters.

A 2015 poll confirmed less than half of young Australians aged 18-29 think democracy is preferable to any other kind of government. Earlier data indicated Australians of all ages preferred democracy less than Indians and Indonesians, and only marginally more than Fijians. This was on top of a 2013 revelation that one in four Australians aged 18-25 was not enrolled to vote.

To conclude such indifference to democracy and democratic participation reflects a crisis in Australian democracy would confuse a symptom with the disease. Falling confidence in the engine room of Australia’s democracy – our democratic institutions and the policymaking process – is driving the erosion of support for democracy itself.

Democracy’s central problem is its institutional failure to safeguard the long term and manage hyperconnectivity.

We live in an era of path-dependent policymaking, where competent, future-focused and values-driven policy that reconciles expert and community opinion, gains and sustains a long-term consensus, and devolves or projects solutions within or across borders seems rarer by the day.

The result is a system ripe for disruption.

In 2013, the Oxford Martin Commission for Future Generations released Now for the Long Term. The report concluded short-termism triumphed the world over, in domestic politics and also across multilateral forums and business. Within the Commission’s policy team were two Australians: Natalie Day, a Melbournian, and me, a West Australian who would soon call Melbourne home.

The Commission was no academic exercise. Chaired by Pascal Lamy, then Director-General of the World Trade Organisation, the Oxford-based Commission featured practitioners from around the world, including Minister Liu He (China), Arianna Huffington (United States), Minister Trevor Manuel (South Africa), Nandan Nilekani (India) and Michelle Bachelet (Chile).

The Commissioners identified five shaping factors causing policy gridlock and a global knowledge-action gap.

Institutions increasingly unfit for purpose and not adapting to hyperconnectivity;

Time poor policy and business environments dominated by electoral and quarterly reporting cycles;

Political Engagement and public trust fading fast with declining membership and poor adoption of new methods to connect;

Growing Complexity whereby problems scale faster than solutions; and

Cultural biases amplified by globalization, which excludes key voices.

Australia is no stranger to these shaping factors. Our Senate is nowadays neither a house for states nor a thriving house of review. Our recent Intergenerational Report devoted less than 10 per cent of its pages to ‘preparing for the future’. Individual football clubs have more members than our major political parties and use social media more creatively to interact with fans. Our response to Ebola and global displacement is to pull up the drawbridge, not to construct long-term solutions. Our longest war, in Afghanistan, has been unaccompanied by debate about the core values fought for, or how those globalization has left behind can prosper in its wake.

Blaming our current political leaders or harking back to an earlier age of bipartisanship generates heat but little light. The problem runs deeper.

Indeed, Australia’s intransigence in dealing with climate change ‘has exposed the least obvious crisis of the 21st century: our system of democratic governance’.

Reversing this trend requires a system overhaul.

To be clear: this is not a call for autocracy.

Democracies in the international system have grown in number and quality since United States President Woodrow Wilson sought Congressional authorisation to enter the First World War to ‘make the world safe for democracy’. Whether we draw on Freedom House statistics or democratic peace theory, democracy was the success story of the 20th century. Its ongoing success depends on continued prosperity for established democracies, the trajectory of ‘strategic swing states’, and recognition of the growing gap between democratic institutions and the speed, scale and complexity of 21st century challenges.

The performance of democracies is now ‘deficient’. Our challenge is to deepen, enrich and renew democratic institutions and policymaking processes, not to turn away from democracy itself.

Renewal will be a long-term project with multiple dimensions. Australia is lucky because she can draw on efforts abroad, not least using technology to connect more citizens with the policymaking process. Let me suggest two other reforms. The first is deliberately disruptive. The second is boring but essential.

First, we should appoint some ministers from outside parliaments. This is an idea whose time has come, despite the structural challenges this would entail. Too many individuals with little experience beyond politics populate our parliaments. While we should respect those who devote a lifetime to public service, the result can be parliaments that poorly reflect society, and ministers with insufficient expertise. Less than one third of Australian parliamentarians are women. Over 80% of Cabinet Ministers from 1996-2010 under Prime Ministers Howard and Rudd were men. More than half in the same period were lawyers before entering parliament.

Appointing some ministers from outside parliaments would allow experts at the top of their game to lead some portfolios. A constitutional amendment would be required federally, but the move would not be inconsistent with the principle of responsible government. Experiments could happen faster in our states, such as under the Rann Government in South Australia. Imagine Tim Costello as Minister for International Development, Richard Goyder as Minister for Finance or Rosie Batty as Minister for Women. It’s a tantalizing prospect, one that could be a productive spanner in our ministerial workplace.

Second, we need regular Constitutional (or Democratic) Conventions to service our democratic machinery. Australia has only had five conventions, and just two since Federation. Four (1890, 1891, 1897-98 and 1998) were for a specific purpose. The 2020 Summit was an attempt at fashioning a long-term plan, but was mocked for its uniqueness.

Australia needs routine stocktakes of her Federation. White Papers and COAG Reform Councils come and go, hijacked by talking points and short-term politics. Regular, independent root and branch reviews of the engine room of our democracy are essential to ensure it can reach optimum horsepower.

Regular democratic conventions, say twice a decade, would allow the renewal process to connect the political class across the country with civil society, including young Australians. Institutional reforms, such as to constitutional preambles, electoral terms, ministerial appointments, or even Australia’s head of state, could be considered for collective impact. This would prevent one proposed change – such as that to a republic – becoming an inapt stalking horse for deeper democratic renewal. An Australian Head of State, for example, may be the final, not the initial, element of the first renewal phase.

Former Treasury Secretary, Ken Henry, recently said he couldn’t recall ‘a poorer quality public debate, on almost any issue’ than we have now. At the same time a poll found 94% of Australians believe we need a better plan for the long term. Such a plan can be found by embracing long-term democratic renewal as a core element of Australia’s nation-building infrastructure. Only then can Australia’s policy development process produce reforms to match the challenges presented by the 21st century. Only then can we connect the country around a plan with staying power beyond individual political cycles, and convince all Australians to prefer our democratic institutions with greater fervor.

***

This piece first appeared in the spring edition of Meanjin (volume 74, number 3) in September 2015 by Melbourne University Publishing. You can download a print version of this essay here.

The post Travers McLeod: Does apathy to the political system among young people point to a crisis in Australian democracy? | Meanjin, Spring 2015 appeared first on CPD.

Jennifer Doggett, Ian McAuley and John Menadue: No wonder we’re wasting money in health care – we got the incentives wrong

A recently-aired ABC Four Corners program aptly titled “Wasted” exposed three areas of unnecessary, ineffective and outright dangerous health interventions, in knee, spinal and heart surgery.

The show’s host, Norman Swan, presumably extrapolating from the findings in those three areas, claimed that waste could be as high as 30 percent of all health care expenditure.

Perhaps that’s an overstatement, but the point made by Swan and by most of the ten other clinical experts who appeared on the program is that we just don’t know how much waste there is in health care because we lack the processes for evaluating the effectiveness of various interventions.

We know what we pay for a knee replacement or a cardiac stent, but we do not systematically evaluate the outcomes of these procedures.

Identifying and reducing or eliminating funding for low value services would save our health system billions every year.

However, this would only address one area of waste and inefficiency within our health system. A less obvious but potentially more significant source of waste lies in the way in which health care is funded in Australia, in particular via fee-for-service payment mechanisms and private health insurance.

These funding processes are driving unsustainable growth in health services consumption without meeting the needs of the community for efficient, preventative and coordinated care.

Unless Australia’s health funding system is fundamentally reformed to discourage inefficient and provider-driven health expenditure, efforts to increase the efficiency and targeting of Medicare expenditure will be dwarfed by the growing waste associated with our current funding systems.

The big picture

Every year we spend around $160 billion on health care – two thirds through our taxes, and one third through private sources.

At a macro level we can claim we spend that money well. At around ten per cent of GDP it’s in line with expenditure in similar countries, and by gross indicators such as infant mortality and life expectancy we’re among the high achievers.

But within our health care arrangements – a complex mix of private and public funding and provision – there are areas of poor outcomes, such as indigenous health, youth suicide, and obesity, and there is evidence of resource misallocation, such as long waiting times for elective surgery in public hospitals while there are government subsidies encouraging queue-jumping for those with lesser needs to use private hospitals.

The role of data

It’s not that we fail to collect data in many areas of health care, but as Adam Elshaug, Associate Professor of Health Care Policy at Sydney University points out, all the data is kept in separate silos – some relating to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, some relating to the Medical Benefits Scheme (MBS), and some in state public hospitals just to name three of the non-interlinked sources.

While we lack a systematic method of data analysis and feedback (which was one of the original purposes of Medicare), there are a some studies of cost effectiveness in specific areas of health care, upon which the experts were able to draw. In these three areas of health care, that make up a large proportion of surgical admissions in private hospitals, all the experts were able to identify evidence of ineffective treatment and over-servicing and where resources could be put to better use. As an example Swan pointed out:

At least half of all back scans and X rays are of no value, and to put that into perspective, that’s at least half a billion dollars over ten years. Now that would buy you a regionally delivered national suicide prevention program that would save 1000 lives a year.

The experts offered a number of explanations for this waste. One strong message was that the vast majority of the 5700 items on the MBS schedule had never been subject to any rigorous cost-effectiveness evaluation. As Elshaug reminded us, the MBS schedule dates back to the 1960s (when it had only 300 items), when the idea of “evidence based policy” as a standard was still some decades off. It has been easy for advocates, mainly in the medical profession, to add new items to the schedule, but it is very hard to have any removed. Professor Rachelle Buchbinder, Director of the Department of Clinical Epidemiology at Monash University, recounted the great difficulty she had experienced in having just one item removed from the MBS. She was confronted by well-funded corporate interests, and was subject to ad hominem vilification. (We wish Minister Ley the best of luck in her taking on the MBS schedule.)

Drivers of growth

Many referred to the availability of imaging technology, referring, for example, to the fact that GPs can now order knee MRIs without going through a specialist. Often discussions about technology in health care degenerate into a romantic and unrealistic call for the clock of technological advancement to be turned back. But Paul Glasziou, Director of the Centre for Research and Evidence Based Practice at Bond University pointed out that imaging and other diagnostic technology is here to stay and is becoming more widely available (have you noticed that “health” app on your smartphone?). As the Productivity Commission pointed out in its 2005 report on medical technology, IT-based technologies in most industries have reduced unit costs, and there is no reason why it should not do so in health care if used properly.

The problem that Glasziou and others pointed out is that diagnostic technology has given us much more capacity to detect what is “abnormal” or supposedly “wrong” in our bodies. We misinterpret the normal changes associated with ageing, and, as a result otherwise healthy people are turned into “patients”. Our expectations and anxieties as consumers have interacted with GPs’ fear of missing a diagnosis and desire to do something tangible, in the form of delivering a “product” to the patient, leading to a detected abnormality and on to surgery, with all the attendant costs and the possibility of infection and other iatrogenic risks. (A similar motivation to provide some tangible product has been found to be a driver of pharmaceutical over-prescribing.) Doctors are generally dedicated professionals motivated by a strong desire to “do something” for those who turn up in their surgeries.

But as Robyn Ward, Chair of the Medical Services Advisory Committee said, “often the best medicine is no medicine at all, often the best intervention is no intervention at all”.

She said that if GPs could explain how certain procedures are ineffective, patients may make better decisions. And if GPs or other health professionals could help people understand that adopting a healthy lifestyle may be more effective (and certainly less costly) than going down the diagnosis-surgery path, there would be better outcomes all around.

The problem with our current funding system

But that’s not where the incentives lie in a fee-for-service system. Swan summarised the problem when he said “the way we pay for health services in Australia does not encourage good practice”. We pay for throughput, not for outcomes.

One perverse consequence of these incentives for over-servicing is that early intervention at the primary care level, which is supposed to result in better health outcomes and financial savings, can actually worsen outcomes and cost money when the incentives are wrong.

Cardiologists Richard Harper (of Monash University) and Andrew Macisaac (of St Vincent’s Hospital) noted that there was excessive use of angiograms (Harper suggested that up to 43 percent of invasive angiograms were unnecessary), and that these were most likely to occur in private hospitals. There is a confirmation of published findings by Monash University researchers that observed “startling variation” in the use of well-known procedures in Victorian hospitals. They found “in the 14 days following a heart attack, men and women admitted to a private hospital were 2.20 and 2.27 times more likely to receive angiography than their counter-parts in public hospitals”. They were 3.43 and 3.86 times more likely, respectively, “‘to undergo revascularisation” (coronary by-pass surgery, angioplasty and stent).

That study was published in 2000, around the same time the Commonwealth was strengthening subsidies for private health insurance, in a set of arrangements that de factolinked funding of private hospitals to private insurance. At no time has the Commonwealth evaluated that policy, but independent research suggests that while it has injected a large amount of new money into private hospitals, and into the incomes of medical specialists, it has done nothing to achieve its avowed objective of “taking pressure off public hospitals”, because where the funds have gone, so too have the specialists. If anything the subsidies have sucked resources out of public hospitals and have put pressure on public hospitals to try to match the incomes specialist can enjoy when they work in private hospitals.

If people who present to private hospitals get more treatment than those with similar conditions who present to public hospitals, then there is certainly some resource misallocation. Either public patients are being under-serviced, or private patients are being over-serviced. The Four Corners program strongly suggests the latter.

The funding honeypot – private health insurance

While there were frequent reference to the problems of fee-for-service medicine, the program only touched on the interaction of private health insurance and fee-for-service remuneration, which is where the root of the problem lies. Private health insurance is a major driver of resource misallocation and waste. But since 1997 the Commonwealth has had a policy of supporting private insurance, almost as an end in its own right.

It is notable that not since 1969 – when the Nimmo Report paved the way for universal public health insurance – have governments subjected private health insurance to policy scrutiny. The principle of evidence-based medicine, and the general bipartisan disdain for industry subsidies, do not seem to apply to private health insurance.

Although unquestioned support for private health insurance is normally associated with Coalition governments (“Private health insurance is in our DNA was Prime Minister Abbott’s justification), it has become bipartisan. When the Rudd Government set up the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission it specifically ruled out any scrutiny of private health insurance. The Gillard Government strengthened the Medicare Levy Surcharge penalties for those higher income people without private insurance, and removed the 20 per cent tax offset for those who incur expenses not covered by private health insurance. Only the Greens seem to be committed to the original principles of Medicare as a single national insurer.

Thanks to the Medicare Levy Surcharge, people on higher incomes (individuals with an income above $90 000 and families with an income above $180 000) are virtually conscripted into private insurance. Quite apart from the problem of promoting a two-tier health system, with the public system reduced to a residual “charity” system, the surcharge has strong incentives for people to use private insurance, and for opting out of sharing his or her health expenses with other Australians. Someone with an income of $150 000 can either buy top hospital cover for around $1300 or pay an extra $2250 in taxes, for example.

The subsidy to private health insurance comes to more than $8 billion a year according to Commonwealth Budget papers, and is growing strongly. That figure does not include the effect of the Surcharge, which, if it is re-framed as a subsidy for having private insurance (rather than as a penalty for not having it), results in revenue forgone of around $3 billion a year, or a total subsidy of around 11 billion dollars a year. As Jeff Richardson of Monash University once said, not even in the days of high support of manufacturing were the rich actually provided with a taxpayer-funded Holden with change left over.

With governments ready to provide such permissive access to public money to support private insurance, it is hardly surprising that private health insurance premiums have risen so strongly. Since 2000, while general prices (as measured by the CPI) have risen by 54 per cent, private health insurance premiums have risen by 133 percent – a 50 per cent real increase. As a source of ever-growing funds private insurance has been a honeypot for private hospitals and those who work in them (as well as directing public money that taxpayers may have believed were for health expenditure, to flybuy cards and Coles gift vouchers).

So long as we have a highly-subsidised private health insurance industry, fee-for-service medicine, and a private hospital system with its own privileged source of funding, these problems will remain. In time we could head to the US system, where private health insurance has resulted in health costs approaching 20 per cent of GDP, and with only mediocre outcomes by the standards of most prosperous countries. (“Obamacare” will solve some coverage problems, but it will not solve the cost problem.)

The real cost of private health insurance

There are several independent analyses of the costs of private health insurance – Jeff Richardson’s “Private Health Insurance and the PBS: How effective has recent government policy been?”, an analysis by Don Hindle and Ian McAuley “The effects of increased private health insurance: a review of the evidence”, a Centre for Policy Development paper “Private health insurance: High in cost, and low in equity”, an article for The Conversation by Terence Cheung of the University of Adelaide “Why it’s time to remove private health insurance rebates”, and a chapter in the recently-published book Governomics: can we afford small government?

A common theme of these works is that measures such as private health insurance, designed to shift costs off-budget, generally result in the public paying more for the same or worse services, with far less accountability or equity, and with much higher administrative costs as slimmed down public agencies (such as Medicare) are replaced by corporate bureaucracies duplicating competitors’ corporate bureaucracies.

In fact, in the USA, reliance on private health insurance, far from saving public money, has resulted in a blowout in public expenditure. Because health costs are set in an undisciplined market between powerful service providers and comparatively weak health insurers, even the publicly-funded programs (Medicare and Medicaid) are now costing more than the comprehensive single insurer models in place in Canada, the UK and the Scandinavian countries.

Outcomes, not volume

In the Four Corners program Robyn Ward called for a system that pays for value and outcomes rather than activity or volume. It’s a view shared by many others.

It is hard to see how such a system based on outcomes rather than outputs could be developed through any monetary incentive system. One basic problem is that in very few cases is it possible to link any specific health interventions unambiguously to outcomes. There are too many other variables leading to people’s health outcomes, and there is often a very large time lag between interventions and outcomes. When it comes to non-interventions (e,g, the decision not to have a knee reconstruction) the measurement and time lags are even more problematic.

It is even harder to see how any private insurance-based system can deliver satisfactory consumer outcomes or any significant degree of cost control. The economics textbooks claim that businesses seek profit, while the business textbooks, based on empirical studies of organizational behaviour, see growth and expansion as the prime objective of firms (with profit as a constraint to be satisfied). That growth objective would surely dominate in any scheme relying on financial incentives, leading to over-servicing. The Four Cornersprogram is an excellent exposition of the way private sector incentives lead to such poor outcomes. If costs rise because of over-servicing, the insurers can simply jack up their premiums.

The benefit of a single public insurer is that Commonwealth Treasurers will always sustain pressure to keep expenditure in control and to achieve value for money. It’s easier for insurers to raise premiums than for governments to raise taxes.

Public insurance, private and public delivery

That is not to say the private sector should not be involved. It is simply to point out that private insurance should have no role in funding health care.

There is clearly a role for personal out-of-pocket (i.e. uninsured) contributions to health care. In fact, such contributions are a feature even of the most generous single insurer models as operate in the Scandinavian countries, and, in a wealthy country such as Australia they should clearly pay their part. When Medicare was first designed we were much less prosperous, but now, on average, households now have around $300 000 in financial assets, a figure that has grown, in real terms, more than 60 per cent this century.

While we all need to be covered for high health care expenses, we don’t need the “first dollar cover” provided by so many private insurers – the cover that drives us to over-use of health services. Both public and public insurance comes with the same incentive for over-use (“moral hazard” in the quaint language of economics) – there is no difference in the notion “Medicare will pay for it” and “BUPA/Medibank Private/HCF will pay for it”, but, as pointed out above, Medicare comes with the discipline and accountability of public finance, and it is easy for governments to build in compulsory out-of-pocket contributions to lessen moral hazard.

Out-of-pocket payments provide some price signals to consumers, and they can be designed in such a way that most people who make light use of health services in any one year can be independent of any public funding support, so that public funding can be directed to serious acute and chronic conditions. We already spend around $27 billion a year in out-of-pocket contributions, but, as Jennifer Doggett points out, their incidence is haphazard, and do not adhere to good insurance principles: some health care programs are free at the point of service, while for some others the patient is left bearing open-ended risk. Ham-fisted ideas to bring in open-ended MBS co-payments, as proposed by the Abbott Government, understandably meet with community resistance.

In the delivery of services the private sector has always played a central role, and will go on doing so. Alarmists often interpret any criticism of private health insurance as an attack on the “private system”, but that’s bunkum. There is no reason why private hospitals cannot be involved in delivering publicly-funded services.

That model is already operating in Australia through the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, which acts as a single insurer for war veterans, while purchasing most services, including hospitalisation, from the private sector. At a state level there have been initiatives to break this dependence. Victoria, under the leadership of Premier Jeff Kennett first made the offer to private hospitals in the 1990s and the Tasmanian Government has recently offered of elective surgery cases to private providers. There’s nothing radical about such measures – in fact they are in line with national competition policy that calls for competitive neutrality between private and public sector providers.

Future dangers – Medicare Select

The Four Corners program has been a useful reminder of the problems we face in health care, particularly (but not only) the perverse outcomes when private insurance, fee-for-service payment, and a private hospital system separated from public hospitals interact. No doubt private insurers, who will be well aware of these perverse outcomes, will be presenting to government schemes which they claim will solve these problems. For example, arising out of the Health and Hospital Reform Commission’s work, the insurers put forward an idea called Medicare Select, which made great claims about consumer choice and cost control, but which was simply a way of churning even more public funds through health insurers, adding private sector administrative costs to public sector administrative costs, without demonstrating any value-added, other than offering consumers some “choice” of care plans – as if people are in a position to know their future health care needs.

We could well see the private insurers offer Medicare Select, or some similar proposal, as a “solution” to our problems. Even if such schemes are put forward in good faith, we should heed the lessons from the USA, however, where private health insurers have been quite unable to contain health costs – or perhaps unwilling.

There are too many parties – medical specialists, private hospital companies, appliance manufacturers, pharmaceutical firms – who would see cost containment as quite inimical to their interests. And there is the whole investment community – superannuation funds, banks stockbrokers, financial advisors – looking for a new growth industry, as profits in traditional industries such as airlines, newspapers and retailing are squeezed.

Only a strong government can protect us from the economic and health costs of health care becoming a growth industry.

***

Jennifer Doggett is a consultant in the health sector. Ian McAuley is a Adjunct Lecturer, Canberra University. John Menadue chaired Health Enquiries in NSW and SA and was involved with Gough Whitlam in the creation of Medicare. All three are Fellows of the Centre for Policy Development.

***

This article first appeared on John Menadue’s blog Pearls and Irritations: http://johnmenadue.com/blog/. Earlier this year John posted three articles on health reform as part of the Policy Series ‘Fairness, Opportunity and Security’ which he edited with Michael Keating:

Health Policy Reform: Part 1 – Why reform is needed.

Health Policy Reform: Part 3 – Principles for reform.

The post Jennifer Doggett, Ian McAuley and John Menadue: No wonder we’re wasting money in health care – we got the incentives wrong appeared first on CPD.

September 21, 2015

Is our Westminster system past its use by date? | Thought Starters

A short constitutional quiz:

What section of our Constitution defines the role of Cabinet?

How does the Constitution define the relationship between Executive Government and the Public Service?

Exactly what form of Westminster government is prescribed in the Constitution?

How does the Constitution define a “political party”?

A clue to the answers: in one of those management training exercises the trainer sets up a game of quoits, with a line drawn on the floor a couple of meters from the spike. The instruction to the participants is to get as many quoits on to the spike as possible, and there is no mention of the line. Almost all participants stand behind the line, and miss most shots.

Too often we assume the existence of constraining rules. The Constitution is silent on all these matters.

Yet by convention, we have taken on rules that shape our political decision-making. A government that does not have cabinet solidarity is in grave danger of collapse. The public service is loyal solely to Executive Government. Political parties must maintain their discipline. And so on.

These rules would be functional in a pure Westminster system, with two dominant party groupings each representing defined class interests. In the 1951 election, for example, the primary vote as we now say was 50 per cent for the Coalition and 48 per cent for Labor. There wasn’t much residual voter preference.

But the trend in the two party vote has been downwards for the last 75 years. In the 2013 election the combined Coalition/Labor vote was below 80 per cent. Some parties have come and gone, but by now the Greens seem to be fairly well entrenched. And that’s not to mention others in the Senate who would gain a quota even with more restrictive voting rules, and independents and Greens in the House of Representatives.

Political scientists offer a simple and compelling explanation for the slow death of the two party system: “class”, as we once understood it, has become less relevant to our political interests. It’s not that we have become a classless society – in fact by most measures Australia in the postwar years was more egalitarian than it is now. But there is no longer any reliability in assuming that our political interests are associated with our income or wealth.

In Australia Labor and the Greens have been chasing middle-class professional votes, while the Liberal Party has been chasing the “blue collar” vote and the National Party has found its constituency drifting from the squattocracy to hardscrabble farmers. In the US, states with higher average incomes tend to vote Democrat, while the poorer states vote Republican.

All this is well-known, but our governance arrangements have not kept pace with these changes.

The problem of this misfit is starkly clear in the Turnbull Government.

Two issues – allowing same-sex marriage and taking strong action on climate change – illustrate our policy bind.

Both have strong community support. And, it is almost certain, a majority of our elected representatives would be in support of these measures.

Standing in the way of a common sense solution are the supposed rules of our supposed “Westminster” system. By application of these rules a rump of the governing party can stymie reform. In fact, it can be shown with a little arithmetic that when a governing party has a formal factionalised system of representation (as is the case in the Labor Party and in the Coalition with the formal status of the National Party), at the limit 12.5 percent of parliamentary members could dictate how the legislature votes on policy, even if the other 87.5 percent of parliamentarians would vote differently.

So attached are we to these rules that we live in terror of a “hung parliament” – notwithstanding the demonstrated successes of so-called “minority” governments. The Gillard Government worked quite well without a majority in the House of Representatives, various state governments have operated in “minority” status, we rarely have a Senate in which the governing party has a working majority, and in most European democracies a majority government would be a rare phenomenon.

Similarly, when a politician votes against his or her own party’s positions, the media talk about disloyalty and we use the emotive term “crossing the floor”, conjuring images of soldiers in trench warfare running across no-man’s-land to betray their colleagues.

When there is a rumour of policy dissent in Cabinet, the media brings out the tired and overworked cliché “disunity is death”. It’s as if the ideal democracy is one led by an unimaginative bunch of men and women suffering from terminal groupthink.

And, of course, the public service is loyal to the governing party and the governing party only – providing advice, and, increasingly, de facto political support. No form of torture is so feared by public servants as having to appear before parliamentary committees where there may be politicians from other parties. Yet more and more legislation is being modified in the Senate, where so-called “opposition” and “crossbench” members have no access to the advice of the public service – a situation that can lead to very poor legislation. Senior public service would suffer stress-related breakdowns if they had to deal with a House of Representatives where each major issue required cross-party negotiation.

Our present “Westminster” system is past its use-by-date. There are two ways we can go.

One is to forget about party discipline. If Turnbull were to put up a bill on same sex marriage or climate change then obviously some in his own party would vote against it, but that is no different from the situation that has faced every US President, who can never take partisan support in Congress for granted. Some may say a loss of cabinet and party solidarity can lead to uncertainty, but is uncertainty any worse than blocked reform and a denial of the community’s wishes?

The other way is to see our main parties break up into more defined gatherings – for example with the Liberal Party breaking into a liberal party and a conservative party, the Labor Party breaking into a conservative trade-union party and a progressive “left” party, and the National Party going its own way (as has been the case in Western Australia at times). That would lead to a system more akin to those operating in mainland European countries. Those who deride such systems frequently refer to the instability of the Greek and Italian Governments, but neglect to mention Netherlands or Germany as successful and stable examples. In fact, the criticism of multi-party democracies is that in terms of policy they tend to be too stable, because it’s hard for one strong party to dominate. But anyone looking at some of our main policy arenas – taxation, climate change, health insurance, immigration, education – would say that our combative “Westminster” system has been a major source of policy instability.

Either way we can break from our self-imposed rules, without changing a word of our Constitution.

Ian McAuley is a CPD fellow, and co-author of Governomics: Can we afford small government?

The post Is our Westminster system past its use by date? | Thought Starters appeared first on CPD.

Is our Westminster system past its use by date?

A short constitutional quiz:

What section of our Constitution defines the role of Cabinet?

How does the Constitution define the relationship between Executive Government and the Public Service?

Exactly what form of Westminster government is prescribed in the Constitution?

How does the Constitution define a “political party”?

A clue to the answers: in one of those management training exercises the trainer sets up a game of quoits, with a line drawn on the floor a couple of meters from the spike. The instruction to the participants is to get as many quoits on to the spike as possible, and there is no mention of the line. Almost all participants stand behind the line, and miss most shots.

Too often we assume the existence of constraining rules. The Constitution is silent on all these matters.

Yet by convention, we have taken on rules that shape our political decision-making. A government that does not have cabinet solidarity is in grave danger of collapse. The public service is loyal solely to Executive Government. Political parties must maintain their discipline. And so on.

These rules would be functional in a pure Westminster system, with two dominant party groupings each representing defined class interests. In the 1951 election, for example, the primary vote as we now say was 50 per cent for the Coalition and 48 per cent for Labor. There wasn’t much residual voter preference.

But the trend in the two party vote has been downwards for the last 75 years. In the 2013 election the combined Coalition/Labor vote was below 80 per cent. Some parties have come and gone, but by now the Greens seem to be fairly well entrenched. And that’s not to mention others in the Senate who would gain a quota even with more restrictive voting rules, and independents and Greens in the House of Representatives.

Political scientists offer a simple and compelling explanation for the slow death of the two party system: “class”, as we once understood it, has become less relevant to our political interests. It’s not that we have become a classless society – in fact by most measures Australia in the postwar years was more egalitarian than it is now. But there is no longer any reliability in assuming that our political interests are associated with our income or wealth.

In Australia Labor and the Greens have been chasing middle-class professional votes, while the Liberal Party has been chasing the “blue collar” vote and the National Party has found its constituency drifting from the squattocracy to hardscrabble farmers. In the US, states with higher average incomes tend to vote Democrat, while the poorer states vote Republican.

All this is well-known, but our governance arrangements have not kept pace with these changes.

The problem of this misfit is starkly clear in the Turnbull Government.

To issues – allowing same-sex marriage and taking strong action on climate change – illustrate our policy bind.

Both have strong community support. And, it is almost certain, a majority of our elected representatives would be in support of these measures.

Standing in the way of a common sense solution are the supposed rules of our supposed “Westminster” system. By application of these rules a rump of the governing party can stymie reform. In fact, it can be shown with a little arithmetic that when a governing party has a formal factionalised system of representation (as is the case in the Labor Party and in the Coalition with the formal status of the National Party), at the limit 12.5 percent of parliamentary members could dictate how the legislature votes on policy, even if the other 87.5 percent of parliamentarians would vote differently.

So attached are we to these rules that we live in terror of a “hung parliament” – notwithstanding the demonstrated successes of so-called “minority” governments. The Gillard Government worked quite well without a majority in the House of Representatives, various state governments have operated in “minority” status, we rarely have a Senate in which the governing party has a working majority, and in most European democracies a majority government would be a rare phenomenon.

Similarly, when a politician votes against his or her own party’s positions, the media talk about disloyalty and we use the emotive term “crossing the floor”, conjuring images of soldiers in trench warfare running across no-man’s-land to betray their colleagues.

When there is a rumour of policy dissent in Cabinet, the media brings out the tired and overworked cliché “disunity is death”. It’s as if the ideal democracy is one led by an unimaginative bunch of men and women suffering from terminal groupthink.

And, of course, the public service is loyal to the governing party and the governing party only – providing advice, and, increasingly, de facto political support. No form of torture is so feared by public servants as having to appear before parliamentary committees where there may be politicians from other parties. Yet more and more legislation is being modified in the Senate, where so-called “opposition” and “crossbench” members have no access to the advice of the public service – a situation that can lead to very poor legislation. Senior public service would suffer stress-related breakdowns if they had to deal with a House of Representatives where each major issue required cross-party negotiation.

Our present “Westminster” system is past its use-by-date. There are two ways we can go.

One is to forget about party discipline. If Turnbull were to put up a bill on same sex marriage or climate change then obviously some in his own party would vote against it, but that is no different from the situation that has faced every US President, who can never take partisan support in Congress for granted. Some may say a loss of cabinet and party solidarity can lead to uncertainty, but is uncertainty any worse than blocked reform and a denial of the community’s wishes?

The other way is to see our main parties break up into more defined gatherings – for example with the Liberal Party breaking into a liberal party and a conservative party, the Labor Party breaking into a conservative trade-union party and a progressive “left” party, and the National Party going its own way (as has been the case in Western Australia at times). That would lead to a system more akin to those operating in mainland European countries. Those who deride such systems frequently refer to the instability of the Greek and Italian Governments, but neglect to mention Netherlands or Germany as successful and stable examples. In fact, the criticism of multi-party democracies is that in terms of policy they tend to be too stable, because it’s hard for one strong party to dominate. But anyone looking at some of our main policy arenas – taxation, climate change, health insurance, immigration, education – would say that our combative “Westminster” system has been a major source of policy instability.

Either way we can break from our self-imposed rules, without changing a word of our Constitution.

Ian McAuley is a CPD fellow, and co-author of Governomics: Can we afford small government?

The post Is our Westminster system past its use by date? appeared first on CPD.

September 17, 2015

Climate change through a sub-national lens | Thought Starters 18 September

With the Conference of the Parties (COP-21) session in Paris fast approaching, the issue of climate change is about to be centre-stage on the global policy agenda. Australian citizens can be forgiven for being pessimistic in the lead-up to COP-21; many remember the way in which the 2009 conference in Copenhagen saw several countries at loggerheads and the chances of a comprehensive, binding global agreement on climate change substantially undermined.

Australia’s major political parties continue to wage war over their favoured public policy response, as well as the degree to which they believe the science. Rigid partisanship and petty politicking have undoubtedly tainted the issue of climate change in Australia and have left those who care about the issue feeling deflated and disheartened.

However, Australians can find a great deal of encouragement, optimism and hope by examining climate policy outside the confines of Canberra. Local government is fast becoming a climate change leader in both the national and international spheres. Australia is home to a range of proactive local councils which are taking the issue into their own hands and combatting climate change regardless of the stalemate currently seen at the federal level.

Furthermore, local government authorities both here and abroad are increasingly looking to one another for inspiration and assistance in the development and implementation of locally directed sustainability initiatives. Around the globe, a range of international climate networks have formed including Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI), the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group (C40) and the R20 Regions of Climate Action (R20), which seek to bring together governments at the local, state and regional levels and prompt the sharing of ideas and expertise.

The role cities must play in combatting climate change should not be understated. C40 has asserted that by 2030, two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities, which will ultimately produce 75 percent of the globe’s greenhouse gas emissions. With this in mind, a range of sub-national networks have joined forces with the City of Paris to organise a “Summit of Local Governments for Climate” during COP-21 and have pushed for an entire day of the Paris conference to be devoted to the role of cities and local government in future climate action.

The emergence and continued growth of these intergovernmental networks represents a significant move towards global governance as a mechanism to address what is very clearly a global problem. The oft-heard phrase “think globally, act locally” is encapsulated by these attempts of local governments to come together, forge partnerships and exchange ideas of best practice unimpeded by national borders and stubborn national governments. Whilst the federal parliament has been and will remain the principal authority for Australia’s engagement with the international community, a number of cities across the country have seized the opportunity to bypass its power and work with those in other countries to achieve far-reaching, practical change in this policy space.

We can look to the Sydney and Melbourne City Councils as leading examples of local governments taking positive action on climate change. Both cities have taken a multi-pronged approach in relation to their planning efforts, focussing both on mitigation – implementing measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prevent future ecological hazards – and adaptation – minimising the risks associated with the unavoidable ramifications of climate change and ensuring that the cities are resilient to its effects in the long term. Both councils have developed a comprehensive climate change adaptation plan for their municipality, which lays out the precise risks facing Sydney and Melbourne if climatic alterations were to drastically accelerate in the future.

In these densely populated, highly urbanised cities, improving the energy efficiency and overall sustainability of major buildings has emerged as a high priority. Sydney City Council has completed a $6.9 million retrofit of city buildings and is progressively rolling out 5,500 solar panels across Council properties. Similarly, the City of Melbourne has introduced its 1200 Homes initiative, which oversees the provision of grants and rebates to building owners, managers and facility managers who are willing to install effective cool roof products and improve the energy efficiency of buildings all across the city.

The total number of undertakings of Sydney and Melbourne go beyond these significant initiatives, and such actions will prove essential in combatting climate change as the population of these cities grow substantially into the future.

The emergence of climate change as a major priority is not only limited to the cities of Sydney and Melbourne. Various local government bodies have sought to tackle this issue together. Local municipalities across South Australia have forged a climate-based partnership through the Eastern Region Alliance, consisting of cities such as Burnside, Campbelltown, Unley and Adelaide City Council. Victoria’s emphasis on the importance of local knowledge in this space has led to the Victorian Adaptation and Sustainability Partnership (VASP), a partnership between the state government and each of Victoria’s 79 local councils with the aim of effectively synchronising local efforts to tackle climate change.

Climate change action is also being seen in Australia’s regions, with Uralla having been selected by the New South Wales government to become the first zero net energy town in the state; having already used solar power in local aged care facilities and to heat the local swimming pool, Uralla’s win has secured $105,000 for a feasibility study to see what mix of renewables can convert the town to green power.

Of course we want to see a comprehensive and binding global agreement emerge from COP-21. It is crucial that our national leaders step up to face this increasingly urgent challenge. If Paris comes to be regarded as Copenhagen 2.0, it should be known that a vast array of cities, towns, states and regions across the globe are seeking to secure their municipalities against the impacts of climate change, and will continue to outmanoeuvre national governments on this issue. Although a leadership vacuum is currently on display in Canberra, there are a number of sub-national governments that deserve credit for the important steps they have taken to address this issue and make their economies viable for the long term.

Matthew Bowron is a CPD research intern and holds a Master of Public Policy. He is the author of CPD’s scoping paper ‘Global Problem, Local Solutions’.

Picture: Nicola Jones

The post Climate change through a sub-national lens | Thought Starters 18 September appeared first on CPD.

Climate change through a sub-national lens

With the Conference of the Parties (COP-21) session in Paris fast approaching, the issue of climate change is about to be centre-stage on the global policy agenda. Australian citizens can be forgiven for being pessimistic in the lead-up to COP-21; many remember the way in which the 2009 conference in Copenhagen saw several countries at loggerheads and the chances of a comprehensive, binding global agreement on climate change substantially undermined.

Australia’s major political parties continue to wage war over their favoured public policy response, as well as the degree to which they believe the science. Rigid partisanship and petty politicking have undoubtedly tainted the issue of climate change in Australia and have left those who care about the issue feeling deflated and disheartened.

However, Australians can find a great deal of encouragement, optimism and hope by examining climate policy outside the confines of Canberra. Local government is fast becoming a climate change leader in both the national and international spheres. Australia is home to a range of proactive local councils which are taking the issue into their own hands and combatting climate change regardless of the stalemate currently seen at the federal level.

Furthermore, local government authorities both here and abroad are increasingly looking to one another for inspiration and assistance in the development and implementation of locally directed sustainability initiatives. Around the globe, a range of international climate networks have formed including Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI), the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group (C40) and the R20 Regions of Climate Action (R20), which seek to bring together governments at the local, state and regional levels and prompt the sharing of ideas and expertise.

The role cities must play in combatting climate change should not be understated. C40 has asserted that by 2030, two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities, which will ultimately produce 75 percent of the globe’s greenhouse gas emissions. With this in mind, a range of sub-national networks have joined forces with the City of Paris to organise a “Summit of Local Governments for Climate” during COP-21 and have pushed for an entire day of the Paris conference to be devoted to the role of cities and local government in future climate action.

The emergence and continued growth of these intergovernmental networks represents a significant move towards global governance as a mechanism to address what is very clearly a global problem. The oft-heard phrase “think globally, act locally” is encapsulated by these attempts of local governments to come together, forge partnerships and exchange ideas of best practice unimpeded by national borders and stubborn national governments. Whilst the federal parliament has been and will remain the principal authority for Australia’s engagement with the international community, a number of cities across the country have seized the opportunity to bypass its power and work with those in other countries to achieve far-reaching, practical change in this policy space.

We can look to the Sydney and Melbourne City Councils as leading examples of local governments taking positive action on climate change. Both cities have taken a multi-pronged approach in relation to their planning efforts, focussing both on mitigation – implementing measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prevent future ecological hazards – and adaptation – minimising the risks associated with the unavoidable ramifications of climate change and ensuring that the cities are resilient to its effects in the long term. Both councils have developed a comprehensive climate change adaptation plan for their municipality, which lays out the precise risks facing Sydney and Melbourne if climatic alterations were to drastically accelerate in the future.

In these densely populated, highly urbanised cities, improving the energy efficiency and overall sustainability of major buildings has emerged as a high priority. Sydney City Council has completed a $6.9 million retrofit of city buildings and is progressively rolling out 5,500 solar panels across Council properties. Similarly, the City of Melbourne has introduced its 1200 Homes initiative, which oversees the provision of grants and rebates to building owners, managers and facility managers who are willing to install effective cool roof products and improve the energy efficiency of buildings all across the city.

The total number of undertakings of Sydney and Melbourne go beyond these significant initiatives, and such actions will prove essential in combatting climate change as the population of these cities grow substantially into the future.

The emergence of climate change as a major priority is not only limited to the cities of Sydney and Melbourne. Various local government bodies have sought to tackle this issue together. Local municipalities across South Australia have forged a climate-based partnership through the Eastern Region Alliance, consisting of cities such as Burnside, Campbelltown, Unley and Adelaide City Council. Victoria’s emphasis on the importance of local knowledge in this space has led to the Victorian Adaptation and Sustainability Partnership (VASP), a partnership between the state government and each of Victoria’s 79 local councils with the aim of effectively synchronising local efforts to tackle climate change.

Climate change action is also being seen in Australia’s regions, with Uralla having been selected by the New South Wales government to become the first zero net energy town in the state; having already used solar power in local aged care facilities and to heat the local swimming pool, Uralla’s win has secured $105,000 for a feasibility study to see what mix of renewables can convert the town to green power.