Centre for Policy Development's Blog, page 41

December 10, 2015

Jen Robinson: Protecting human rights is not a gift

Back in 2008, one thousand of Australia’s “best and brightest brains” met at the 2020 Summit to map out a strategy for Australia’s long-term future. They made three key recommendations for constitutional reform: Indigenous recognition, becoming a republic and the creation of a bill of rights. All three are essential for Australia to come of age as a modern and independent democracy that lives its values — respecting and protecting the rights of all its citizens.

A referendum on indigenous recognition is promised for 2017 and — thankfully — has the support of the vast majority of Australians. We don’t yet know if our new pro-republican Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull will unshackle us from the monarchy, but the ALP has committed to it and this too seems to have majority support.

Yet, a bill of rights seems to be off the political table. It is time we put it back on.

We had an opportunity: after the 2020 summit 87.5 percent of over 35,000 written submissions to the 2009 National Human Rights Consultation supported a bill of rights. The recommendation for a national bill of rights was reinforced.

Despite overwhelming public support, the federal government squandered this opportunity and rejected even a statutory bill of rights. Instead, we got the muted “Framework for Human Rights”: a non-binding, routinely ignored system.

Australia remains the only liberal democracy in the world without a national bill of rights. Our Constitution’s framers cut and pasted from the US Constitution, but stopped short when it came to adopting a US-style bill of rights. Why? Our founding fathers were concerned this would interfere with laws designed to discriminate against racial minorities: the Indigenous population and migrants. For good measure, they included clauses to constitutionally mandate such discrimination.

The vast majority of Australians now want to change our Constitution to remove these clauses and to provide our Indigenous population the recognition they have always deserved. This must happen. But if we really care about protecting Indigenous rights, we should go further and place their basic rights — and ours — beyond government interference.

Although Australia has signed up to international human rights treaties, such rights have not been properly implemented in domestic law. Even the limited anti-discrimination protections we have aren’t constitutionally protected, so are subject to change — and limitation — by Parliament at any time. Absent a constitutional bill of rights, parliamentary sovereignty means that there is no limitation on the power of the legislature to take away our rights.

The majority of Australia’s constitutional framers believed that representative and responsible government would suffice to protect our rights (at least, if you were white). This is a proven myth, but one perpetuated today by Australia’s answers to persistent international criticism over our failure to implement a bill of rights.

In the minority who then supported a US-style bill of rights for Australia was one of our first High Court justices, Richard O’Connor. He pointed out:

We are making a Constitution which is to endure, practically speaking, for all time. We do not know when some wave of popular feeling may lead a majority in the parliament of a state to commit an injustice by passing a law that would deprive citizens of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.

His words were prophetic. We have seen increasing erosion of rights and protections for all Australians and the most vulnerable: from the indefinite detention of asylum seekers and the mentally ill, to counter-terrorism laws imposing disproportionate restrictions on free speech and association, to laws cancelling citizenship without due process. Data retention laws breach the privacy of each and every Australian. Successive, so-called responsible and representative governments have allowed this, and successive “Oppositions” — whether ALP or Liberal — have rolled over. These laws would be struck down if we had a constitutional bill of rights.

Arguing for the more politically achievable option of a statutory bill of rights — such as in New Zealand and the UK — seems to have become the accepted wisdom of what comes next for Australia: a comprehensive statement of rights, but one which would preserve the power of Parliament to override our rights whenever they make that intention clear.

The ACT and Victoria have had this model in place for years — and Queensland looks likely to follow. Nationally, this would be a step up from the current, lackluster Framework. But as the UN Human Rights Committee has made clear, the statutory model does not pass muster because human rights have “no higher status than ordinary legislation”.

Perhaps something is better than nothing. But when it comes to protecting the basic rights of Australians, it is not good enough. We cannot allow what is politically possible today to define what is, in principle, the correct course of action.

We need to provide a democratically-mandated, authoritative statement of Australian rights that puts our fundamental rights beyond political party debate. The US, Canada, India, South Africa and many other democracies have constitutional bills of rights (even the UK is now debating it).

But in the end this is not about what other democracies do or don’t do. This is about us. A constitutional bill of rights would provide an enduring statement of values to reflect the independent, mature and tolerant and dignified nation we want Australia to be.

Let’s start the movement needed to make it happen.

—

Jennifer Robinson is an Australian lawyer and the director of legal advocacy for the Bertha Foundation in London.

This is the ninth piece in CPD’s ‘Secret Santas for Australia’ series. Each day we will reveal one ‘gift’ of good ideas from a prominent Australian on a policy issue close to their heart. You can see the full set here.

The post Jen Robinson: Protecting human rights is not a gift appeared first on CPD.

December 9, 2015

Janet Holmes à Court: A new strategy for Corporate Australia’s gifts to the arts

Coming as I do from a state that periodically suffers the boom and bust cycle inherent in the resources sector, I am only too aware of the impact that philanthropy and corporate sponsorship can have on the arts sector in Australia.

It can be a great blessing during times of plenty, and its withdrawal can be a real curse during downturns such as today.

For example, one arts organisation with which I’m involved has lost over $200,000 in sponsorship from two resource ‘giants’ in response to either the GFC in their home country or to the mining downturn here. As with any other enterprise, amounts far smaller than this can make the difference between an artistic success and an abject failure.

How did we come to be so reliant on corporate sponsorship and private philanthropy, that its withdrawal can have such an impact on an arts organisation, large or small?

Back in the 1990s, the swelling ranks of Australians who had lived and worked in the United States came back and held politicians in thrall with stories of how corporate sponsorship and philanthropy keeps the arts, education, medical research — you name it — going in the USA, with government playing an almost subsidiary role.

On the other hand, Australia, like Great Britain, had a somewhat reverse situation where governments were the major funders for the arts.

Prompted by this discussion, the Australia Council, the Federal Government’s arts funding body, commissioned some research into philanthropy in Australia. The research, undertaken by an expat American, confirmed the impressions of the importance of corporate sponsorship and private philanthropy in the United States, but also underlined the importance of the taxation regime in place there.

Unfortunately, governments in Australia seem to have grabbed the first element without bothering with the second. Equally importantly, they did so without really having a dialogue with both the arts and business sectors as to the feasibility, viability, and sustainability of having a sector increasingly funded by anyone other than government.

In most states, and federally, there has been static or declining funding allocated for the arts, including to the state-funded galleries and museums that are the pride and joy of many of our state capitals. For example, in Western Australia, public funding fell from 1.2 percent of overall government expenditure in 2001 to 0.7 percent in 2014-15.

“Cut expenditure accordingly”, some will say (like the person who wrote to The West Australian in the 1940s regarding the West Australian Symphony Orchestra to say that, if they knew what they were doing, they wouldn’t need a conductor).

However, it’s not that easy. Taking the orchestra example, the number of musicians or choristers can’t be cut without seriously undermining its very existence — an orchestra of less than 60 or 70 players really can’t make Tchaikovsky’s music sound convincing (no more Swan Lake or Nutcracker Suite), and can’t even attempt to play Mahler with any credibility.

From the largest orchestra to the smallest artistic start-up, declining or static government funding can cause serious problems for an arts company. Hence the push to increase corporate sponsorship and private philanthropy on the part of boards of arts companies, and an equal push in future planning documents by governments.

However, the arts and cultural sectors are being forced to build these new, volatile revenue streams in very difficult economic conditions, and without a safety net due to declining funding. This issue was never really canvassed in a coherent way. No government ever said: “Now, over the next 10 years, we’re going to reduce your funding by X percent and we expect you to generate a replacement funding stream yourselves”.

Nor, crucially, did they say to corporate Australia: “We expect you to play an increasing role in sustaining the arts and cultural sectors in Australia, and let’s discuss the best tax plan to encourage this”. Instead, it’s been trial and error, for all parties. Large corporates who have won awards for their sponsorship in one year will suddenly cut their sponsorship in another, if the going gets tough in their industry.

Neither have we ever had a discussion about a desirable percentage of federal or state outlays that the arts should consume. Quite rightly we focus a lot on health and education, and defence (where it’s always about going up), but less frequently the arts and culture.

It is time that our business sector, which is being expected to assume more and more responsibility for the arts, requested a dialogue with federal and state governments and the arts sector, to set some ground-rules here. Some of the issues canvassed could include:

What are governments’ expectations of corporate Australia as regards funding for the arts?

What are the incentives for corporate Australia to be involved with supporting the arts?

What happens during the periodic economic downturns we continue to face, and the booms?

Are there areas where arts organisations feel they cannot accept corporate support (e.g. tobacco interests) and what are governments’ response to these?

What should corporate expect from their sponsorship dollars? There is a danger of prescriptive demands taking arts companies away from their mission.

If an arts company refuses corporate support, what should a government’s response be?

With a new Prime Minister who firmly believes “culture is the essence of who we are“, may I suggest this as a project for the Business Council of Australia?

—

Janet Holmes à Court is an Australian businesswoman and philanthropist.

This is the eighth piece in CPD’s ‘Secret Santas for Australia’ series. Each day we will reveal one ‘gift’ of good ideas from a prominent Australian on a policy issue close to their heart. You can see the full set here.

The post Janet Holmes à Court: A new strategy for Corporate Australia’s gifts to the arts appeared first on CPD.

December 8, 2015

Fiona Sharkie: Giving people with a disability the opportunity to shine

Imagine for a moment that everyone you interacted with on a daily basis only saw you for your shortfalls, and never for your potential. For the one billion people in the world living with a disability, including those on the autism spectrum, this is often their everyday experience.

The reality is we neglect the voices of people with disability. We often speak for them, decide what’s best for them and expect they will just fit into our world, all of which has the result of sidelining them as the ‘other’ in our society.

This inherent discrimination applies to people with both physical and non-physical disability — from unfairly judging the mother whose child on the autism spectrum is having a meltdown in a shopping centre, to letting down the person in the wheelchair who can’t access a building to get to a job interview.

Our aspiration is for a world where people with physical and non-physical disability are understood, embraced and offered the same opportunities afforded to you and me in everyday life. Where they complete their education and get jobs and/or volunteer, where they can enjoy all the social and recreational pursuits they choose and their contributions are appreciated. Where they are valued members of a society that embraces their participation, rather than just accepts or tolerates it.

The leaps our society has made to be more inclusive of people with a disability should be recognised. We have come a long way in the past decade, but there’s a considerable way to go before these people are genuinely welcomed and valued.

We need to work harder to embrace the human form in all its diversity, recognising that people are people first, and that differences should not be an excuse to exclude or place judgment.

The shift to the kind of society we’d like to see is one where a person on the autism spectrum feels empowered to ask for the adaptations to their surroundings they require — such as dimming the lights or simply asking them one question at a time. An inclusive society is one where we enable ways for communities to create inclusion for all.

In many cases a small change can make a huge difference. Heather, a woman living with autism, asked staff at a fish and chip shop to turn the TV off before she could place her order because the competing noise from the TV made this simple task challenging for her. This simple accommodation by the staff made it possible for a person with disability to have her needs met in her community. And the owner of this business learnt more about the needs of people on the autism spectrum: that they can experience sensory overload and may need quiet spaces without bright lights, loud noise and crowds.

We all need to recognise that every individual with a disability has different needs. Before you jump to stereotype a person with a disability, talk to them. Get informed about the huge variety of disabilities, many of which you can’t always see, including the diversity of the autism spectrum.

Most importantly, simply asking a person with a disability what they need is a huge step forward. Ask respectfully and with good intentions and be supportive and willing to help.

Nicole Antonopoulos, whose five-year-old son Greg is on the autism spectrum, says people want to be supportive of her son but they don’t really know what it means and what they can do.

“In my experience there is so much more awareness and willingness from others to help,” Nicole said. “The challenge is for people to build their skills to know what to do and to understand that it’s okay to ask. They don’t have to be an expert in autism. What they can do is to be supportive and try to engage, interact and make a child’s experience on that day a good one.”

Daniel Giles is a graphic designer and photographer and is on the autism spectrum. “I wish people would stop seeing the stereotypes of autism, such as our apparent lack of empathy,” he said. “Not that any of us are perfect but I’d like to see those myths and misconceptions busted.

“We are gifted individuals. We’ve all got the potential to make the world a better place. I’d like everyone to focus less on our challenges and focus more on the gifts and talents we have to offer. I’d like to see more job opportunities for people with autism. We should be given the opportunity to shine.”

People with disability have the same dreams and aspirations as all of us. It comes back to human rights and how the wider world can step up to better support people with disability to take their rightful place in the world.

The shift towards real inclusion starts with each of us. Try speaking to someone with disability and share your experiences. People with disability are not the ‘other’, they’re part of the diverse world we live in and make a huge contribution to its richness.

—

Fiona Sharkie is CEO of AMAZE (formerly Autism Victoria).

This is the seventh piece in CPD’s ‘Secret Santas for Australia’ series. Each day we will reveal one ‘gift’ of good ideas from a prominent Australian on a policy issue close to their heart. You can see the full set here.

The post Fiona Sharkie: Giving people with a disability the opportunity to shine appeared first on CPD.

December 7, 2015

Glyn Davis: Universities – translating the gift of good ideas across society at large

The talk around universities has changed much in recent months.

For the past two years we have been arguing about how to fund the system. Budget cuts were proposed, students marched, senators blocked.

A new prime minister, a new minster for education, and as of yesterday, a new innovation statement. Suddenly it is a different conversation.

Now the moment is about innovation – why is Australia so poor at commercial development of new ideas, and how can universities help?

It is a welcome change of topic, a discussion worth serious attention. The latest UNESCO and OECD data about the Australian innovation effort are not encouraging, so the new policy push is timely.

Fortunately, while this new impetus is very welcome, there is much already in place to build on. Business enjoys a generous research and development tax concession, while universities can access schemes designed to foster collaboration. New funds and incentives to support venture capital and early-stage commercialisation of research and innovation can take us a step closer to the ‘ideas boom’ Australia needs to make our economy more innovative, more productive, and more diverse.

Alongside these national initiatives, and many state-based programs to encourage start-up businesses, there is a great untapped national resource: students and recent graduates who will carry new ideas from the classroom into businesses. Strong demand for incubator programs on campus suggests a new generation has embraced the start-up aspiration.

Across the nation new companies are forming around innovative technologies. Nurtured by university accelerator programs and volunteer entrepreneur mentors, the start-up movement sees many of our best and brightest put aside traditional professional pathways for the world of invention.

Here is a big part of the future – brilliant minds, encouraged on campus to think about a start-up future, supported through programs to instill business skills, helped by willing angels.

Not just universities but medical research institutes, hospitals and private consortia have created incubation space, prizes to support winning teams to develop their ideas, and networks of support for promising business ideas.

These emerging companies join a growing number of university spin-outs – technologies developed over the past decade and now in the market. New vaccines, pharmaceuticals, dentistry products, supplements for animals, materials and IT programs have been supported by investors to foster growth, or sold outright and the proceeds reinvested in university-run seed funds.

In an ideal world, the precincts around Australian universities would already resemble those of Silicon Valle or Cambridge. In time they might. More likely, we will develop distinctive local patterns that reflect the broader realities of the Australian economy – a predominance of small to medium firms, clustered around universities and public agencies, all contributing to the local innovation ecosystem.

Australia could benefit also from welcoming home more of the diaspora – the million or more talented people living abroad, many with the managerial experience to help foster the emerging generation of entrepreneurs.

Translating research into social outcomes is an extension of the traditional university mission. Teaching young engineers, scientists, social entrepreneurs and professionals has always been the role of campus, and continues. Students are exposed to the research of academic staff through teaching, and some take ideas they encounter to create new industries.They may be joined by professors who combine academic work with a role in enterprise.

This model of academic engagement so well-established we often fail to notice the practice. But reflect for a moment on health research. Around half of all Australian research money is distributed to medical and health projects. Much of this research in turn goes to clinical practice, in which academics treat patients while pursuing research, with direct benefits to health outcomes. Not all research returns are measured in new patents. Much of our best medical research tests, informs and improves clinical work. The very high quality of health outcomes in Australia, among the best in the world, reflects an excellent return on this research investment.

In medicine, teaching, research and engagement are closely related. So too across the public sector. Already many linkage grants are awarded to consortia involving government agencies. As in health, research outcomes translate into policy interventions and better program design. Such benefit is not measured in OECD and UNESCO data on commercial translation, but matter for the society we want to be.

Our challenge is to take this model of the contemporary university to other sectors, so that academic engineers also work with industry, and industry in turn values working with universities around new technologies and production techniques.

Universities can train a new generation of business innovators, share existing research platforms, and work closely with commercial, government and community partners. If the new conversation around innovation moves us closer to this vision, it will be a worthwhile discussion indeed.

—

Glyn Davis is the Vice Chancellor at the University of Melbourne.

This is the sixth piece in CPD’s ‘Secret Santas for Australia’ series. Each day we will reveal one ‘gift’ of good ideas from a prominent Australian on a policy issue close to their heart. You can see the full set here.

The post Glyn Davis: Universities – translating the gift of good ideas across society at large appeared first on CPD.

December 6, 2015

Tanya Hosch: Recognition – the greatest gift for all Australia’s children

As most things perhaps should, this discussion begins and ends with our kids. Don’t tune out if you don’t happen to have children of your own — I mean ‘our kids’ in the broadest sense possible. We all share a joint responsibility for all Australian children. They are the embodiment of our future, the people who will comprise this nation after we’ve all passed through.

Every one of us owes every one of them a duty of care; to ensure they are not harmed, to allow them to grow and experience childhood in an environment of safety and harmony and to let them live in a country which respects their individual backgrounds, family histories and cultural lives. We are responsible to ensure they are protected from disease, educated, kept healthy, properly fed and, ideally, each allowed to achieve their individual potential.

And we have a further responsibility: to work for improvements to the nation itself, piece by piece to fix the place up, to leave it better than we found it, to pass on to our children the gift of a nation materially improved on the one in which we ourselves were raised.

We delegate to our governments many of these tasks necessary to the wellbeing of our kids and their preparation for taking the reins when their time comes. We’ve built a society that is like a vast extended family. We elect representatives to government, we pay taxes to fund it, and for that we expect government to provide all those schools and clinics and police officers to take care of our kids. All of our kids.

But some of the larger national maintenance tasks, the ‘home improvements’ we need before passing the place on, fall back on us directly. Constitutional change is a good example. We all need to take part, we need to vote in favour of a referendum proposal in overwhelming numbers, and right across the country. Otherwise it can’t happen.

If we had to hand this country over to the next generation of our children right now, they would be justified in thinking that it was less a gift than a burden. That we had badly neglected our responsibility to render it fit to take its place as a modern nation in the early 21st Century. Here’s why:

This is a nation of people that has been established for at least 40,000 years and only recently experienced several waves of immigration. I mean, very, very recently. Compared to the time span of the original human settlement of this continent, the first — British — wave of migrants dropped anchor a couple of heartbeats ago.

These people went on to set up the legal architecture of modern Australia a mere century or so ago, federating a bunch of British colonies into a more-or-less independent Commonwealth governed by a Parliament. They were quickly followed by new waves of people from pretty much every corner of the planet, resulting in the diverse and culturally gifted country we enjoy today.

But there’s a problem. When those British colonials drew up that national blueprint, they left out the people who were here all along. The Constitution they drafted purports to describe a nation that only popped into existence with the first migrant wave.

In doing so they not only committed a grave injustice to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, they did all Australians a huge disservice. They robbed us of this rich and unimaginably long history and cultural legacy, in which, as modern Australians, we should all take enormous pride and ownership. The oldest living cultures on earth are here, they are as intrinsic to the landscape as eucalypt forest and they have been so for what in human terms is an eternity.

Yet you can’t learn that by reading the Australian Constitution. This has to be rectified if we are to acquit our responsibilities to the generations following us.

What you can learn, sadly, is something of the attitudes 19th Century Europeans brought to their task of creating a new national blueprint and the place indigenous Australians occupied in their thinking. Two sections in particular — one added later — allow for flat-out racial discrimination.

Well, what else should we expect from the 19th Century? The far more important question is: what should we expect of ourselves in the 21st? What should we tell our children to say if an overseas visitor asks: “Is it true your Constitution lets governments discriminate against people based on race?”

We need a better answer than the one we have at present.

RECOGNISE is campaigning to raise awareness of these problems with our Constitution and build support for a successful referendum to fix them. Hearteningly, the more that awareness grows, the more support grows with it.

It’s really quite simple — child’s play, you could say. Earlier generations bequeathed us a Constitution with some flaws so serious we simply can’t carry them any longer. They are a dead weight impeding us, holding us back, as we continue our national journey together.

When it comes time to hand over to all these brilliant Australian kids, we should look them in the eye and say: “Here is your gift, we’ve fixed that for you, now let’s see what you can do.”

—

Tanya Hosch is Joint Campaign Manager of RECOGNISE.

This is the fifth piece in CPD’s ‘Secret Santas for Australia’ series. Each day we will reveal one ‘gift’ of good ideas from a prominent Australian on a policy issue close to their heart. You can see the full set here.

The post Tanya Hosch: Recognition – the greatest gift for all Australia’s children appeared first on CPD.

Tanya Hosch: Recognition – the greatest gift for Australia’s children

As most things perhaps should, this discussion begins and ends with our kids. Don’t tune out if you don’t happen to have children of your own — I mean ‘our kids’ in the broadest sense possible. We all share a joint responsibility for all Australian children. They are the embodiment of our future, the people who will comprise this nation after we’ve all passed through.

Every one of us owes every one of them a duty of care; to ensure they are not harmed, to allow them to grow and experience childhood in an environment of safety and harmony and to let them live in a country which respects their individual backgrounds, family histories and cultural lives. We are responsible to ensure they are protected from disease, educated, kept healthy, properly fed and, ideally, each allowed to achieve their individual potential.

And we have a further responsibility: to work for improvements to the nation itself, piece by piece to fix the place up, to leave it better than we found it, to pass on to our children the gift of a nation materially improved on the one in which we ourselves were raised.

We delegate to our governments many of these tasks necessary to the wellbeing of our kids and their preparation for taking the reins when their time comes. We’ve built a society that is like a vast extended family. We elect representatives to government, we pay taxes to fund it, and for that we expect government to provide all those schools and clinics and police officers to take care of our kids. All of our kids.

But some of the larger national maintenance tasks, the ‘home improvements’ we need before passing the place on, fall back on us directly. Constitutional change is a good example. We all need to take part, we need to vote in favour of a referendum proposal in overwhelming numbers, and right across the country. Otherwise it can’t happen.

If we had to hand this country over to the next generation of our children right now, they would be justified in thinking that it was less a gift than a burden. That we had badly neglected our responsibility to render it fit to take its place as a modern nation in the early 21st Century. Here’s why:

This is a nation of people that has been established for at least 40,000 years and only recently experienced several waves of immigration. I mean, very, very recently. Compared to the time span of the original human settlement of this continent, the first — British — wave of migrants dropped anchor a couple of heartbeats ago.

These people went on to set up the legal architecture of modern Australia a mere century or so ago, federating a bunch of British colonies into a more-or-less independent Commonwealth governed by a Parliament. They were quickly followed by new waves of people from pretty much every corner of the planet, resulting in the diverse and culturally gifted country we enjoy today.

But there’s a problem. When those British colonials drew up that national blueprint, they left out the people who were here all along. The Constitution they drafted purports to describe a nation that only popped into existence with the first migrant wave.

In doing so they not only committed a grave injustice to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, they did all Australians a huge disservice. They robbed us of this rich and unimaginably long history and cultural legacy, in which, as modern Australians, we should all take enormous pride and ownership. The oldest living cultures on earth are here, they are as intrinsic to the landscape as eucalypt forest and they have been so for what in human terms is an eternity.

Yet you can’t learn that by reading the Australian Constitution. This has to be rectified if we are to acquit our responsibilities to the generations following us.

What you can learn, sadly, is something of the attitudes 19th Century Europeans brought to their task of creating a new national blueprint and the place indigenous Australians occupied in their thinking. Two sections in particular — one added later — allow for flat-out racial discrimination.

Well, what else should we expect from the 19th Century? The far more important question is: what should we expect of ourselves in the 21st? What should we tell our children to say if an overseas visitor asks: “Is it true your Constitution lets governments discriminate against people based on race?”

We need a better answer than the one we have at present.

RECOGNISE is campaigning to raise awareness of these problems with our Constitution and build support for a successful referendum to fix them. Hearteningly, the more that awareness grows, the more support grows with it.

It’s really quite simple — child’s play, you could say. Earlier generations bequeathed us a Constitution with some flaws so serious we simply can’t carry them any longer. They are a dead weight impeding us, holding us back, as we continue our national journey together.

When it comes time to hand over to all these brilliant Australian kids, we should look them in the eye and say: “Here is your gift, we’ve fixed that for you, now let’s see what you can do.”

—

Tanya Hosch is Joint Campaign Manager of RECOGNISE.

This is the fifth piece in CPD’s ‘Secret Santas for Australia’ series. Each day we will reveal one ‘gift’ of good ideas from a prominent Australian on a policy issue close to their heart. You can see the full set here.

The post Tanya Hosch: Recognition – the greatest gift for Australia’s children appeared first on CPD.

December 3, 2015

Richard McLellan: Gifting a sustainable food future requires a radical rethink

At this time of year we’re accustomed to reflecting on the 12 months that have gone by and lining up our resolutions for the 12 months ahead. But Australia’s farmers will only get what we really want for Christmas — a productive, profitable and sustainable rural sector — if we start thinking not in years, but in decades.

A decade doesn’t seem like a long time. But by the second half of the 2020s we’ll be experiencing some of the challenging climate scenarios that experts have been warning about for years — including in the recent report by the Climate Council of Australia Feeding a Hungry Nation: Climate Change, Food and Farming in Australia.

Twelve years doesn’t sound very long, but my Dad could tell you how much productivity changed on our farm in the West Australian Wheatbelt in the 12 years immediately after he changed from teams of horses to mechanised tractors. Or after the introduction of superphosphate. Or how many more grey hairs he grew as the winter rains and run-off in Southwest Australia markedly diminished within 10 to 12 years in the 1970s.

Fortunately, he and many other farmers across the WA Wheatbelt adapted to that change. Aussie farmers like my Dad have always been good at dealing with changing circumstances, and have been among the most innovative and adaptive in the world.

But I’m not so convinced they’ll be able to keep-up with the speed, scale and intensity of the climate change impacts that are predicted to affect agriculture across Australia in the years ahead. As clearly spelled out in the recent Australian National Outlook report by CSIRO: “the types of adaptation that have previously served Australian farmers well may simply not be enough in the future.”

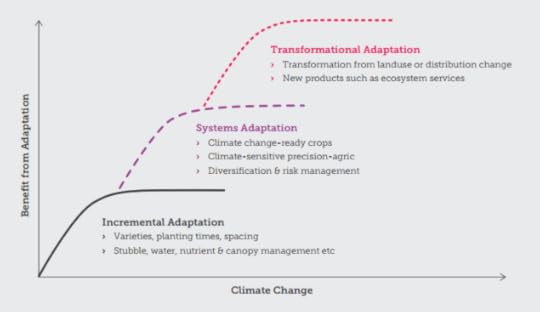

Incremental change probably won’t be enough to address the immense challenges of a changing climate, or provide sufficient guarantees for the future sustainability of farms and rural communities. The authors of Feeding a Hungry Nation instead called for “Transformational Adaptation” (see chart below), which would require new farming products such as ecosystem services and wholesale translocation of farming sectors, and developing new skills for farmers; new markets and supply chains; and new infrastructure.

I’m also convinced that only transformational change will be enough to ensure our agricultural sector survives, and indeed thrives — as we all want it to. To meet current and projected challenges of rising temperatures, increasing drought frequency, and water insecurity, paradigm shift is essential. Changes to stubble management will not be enough.

The International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) believes we need to go even further. It calls for “radical adaptation” involving comprehensive preparation for possible future scenarios and a “fundamental sector-wide re-think of policy.”

Whatever you choose to call it, that’s pretty much the conclusion I’ve arrived at. Edging ahead with incremental change simply won’t guarantee a sustainable farming future. It’s time for a radical re-think.

“Business as usual” and small-scale testing the waters are not solutions. Solutions need to be big and bold, and bloody quick.

Farming has changed a lot in the past few decades, but this is nothing compared to the ‘radical’ changes needed to ensure our farming regions are still profitable and sustainable at the end of the century. Now is the time for a huge increase in investment in funds and ambitious policy change to prepare the country for a very different future.

By all means, let’s keep up the incremental changes: new crops and varieties, rotations, minimum/no tillage, soil optimisation, and the like. But this won’t get us far unless we really start thinking, planning and acting longer-term to catalyse “new generation” diversified and sustainable farm income opportunities.

This must start with ambitious policy and economic incentives.

Let’s provide the policy arena to drive a “clean and green” future.

Let’s seriously invest in innovation, and in integrated research and development, policy and practice that aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions across the agricultural sector. Let’s radically rethink our energy system — not only in terms of production but also in delivery and consumption.

Let’s start paying farmers for investing in and protecting biodiversity, for foregoing land clearing, for providing ecosystem services, for sequestering carbon, for changing land uses and food production systems to what will be truly sustainable.

Let’s stop simply reacting to drought, and instead incentivise real, long-term, climate-smart systems that can cope with our challenging environments and climates.

Let’s provide sufficient government-supported funds and schemes — such as a climate-smart, “future fund”, paid for by a carbon tax or the diversion of current fossil fuel subsidies to help facilitate this outcome.

Let’s invest in producers, supply chains and markets that are prepared to demand and trade in truly sustainable agricultural produce.

Ultimately, let’s provide the policies and economic drivers that will ensure the Australian countryside is still filled with profitable, productive and sustainable farmers in a century’s time.

We need farmers in the bush. They are potentially our “best-bet” resident bush conservation rangers and land stewards, and best-placed to manage our country’s natural assets while providing essential ecosystem services that benefit everyone.

—

Richard McLellan is Chief Executive of the Northern Agricultural Catchments Council.

This is the fourth piece in CPD’s ‘Secret Santas for Australia’ series. Each day we will reveal one ‘gift’ of good ideas from a prominent Australian on a policy issue close to their heart. You can see the full set here.

The post Richard McLellan: Gifting a sustainable food future requires a radical rethink appeared first on CPD.

December 2, 2015

Helen Szoke: Gender equality can’t be a token gift

We shouldn’t have to keep talking about women, but we need to.

We need to because despite all the rhetoric, the studies and initiatives, all the knowledge we have about the inequalities, discrimination, lack of participation, harassment and violence women are subject to, we continue to fail them.

We are failing women around the world despite knowing women can be the single greatest solution to poverty, economic growth and prosperity. We need to do more, and talk less,

Today women remain underrepresented and underpaid in the public and private sectors. Globally, women hold only 19% of Parliamentary seats and only 16% of ministerial posts. Only one quarter of senior officials or managers are women.

At the current rate of progress, women won’t be paid as much as men for equal work for another 75 years.

In Australia and beyond, women do most of the unpaid labour, are over-represented in part-time work and are discriminated against in the household, markets and institutions.

Around the world, women are in crisis. The epidemic of violence against women continues to escalate. One in every three women globally has been beaten, coerced into sex or otherwise abused in her lifetime.

If you are a woman, you are more likely to be poor. The majority of the 1.3 billion people who live in extreme poverty are women and girls. More than 350,000 women die each year from complications during pregnancy and childbirth – 99% of these are in developing countries.

But none of this is new. It’s time for us all, in the public, private and development sectors, to stop talking and do something to ensure women everywhere are empowered, and most importantly, equal.

The private sector is very good at speaking the language of gender equality in the workplace. Corporations are doing a great deal in Australia to make sure women are represented and protected. But often these efforts are not being translated into their global operations.

Supply chains and labour conditions may be exploiting women or creating environments that negatively impact the rights, lives and livelihoods of local communities who are already vulnerable. In these communities women often bear the brunt of these pressures, while receiving few, if any, benefits the business brings.

It’s vital the private sector looks deeper into their practices to ensure they are part of the global effort to help empower rather than add to the vulnerabilities and inequalities women already face.

In the extractives industry alone, research by Oxfam found that only nine of 38 oil, gas and mining companies made any mention of consultation of women and men in any policy or guideline documents that are publicly available.

Corporate Australia must continue to remind itself that the battle for equality is far from won, and must continue to instill policies and frameworks that attract and retain women and provide the same opportunities as men, at all levels, wherever they operate around the world.

The development sector must also do better and hold ourselves to the same standard. Gender must be front and center of everything we do; from self-imposed quotas and employment opportunities to advancement and board representation.

In the field, we must start every single activity by considering how we can work with women to ensure their voices are heard. It’s challenging. All too often, because of culture or capacity, we have to determine how hard we can push to guarantee women will have a place at the table, but it’s vital we keep pushing.

I was recently in Nepal to see first-hand the recovery from the recent earthquake. In a meeting with community leaders in a village high in the mountains near the Tibetan border, the room was almost entirely full of men. One by one they spoke, while the woman who were there sat silently. I insisted that they too must be given the opportunity to speak.

One woman stood and shared her thanks for the relief that had been provided, her family’s challenges and the concerns she had for the future as reconstruction continued.

It was so important to give these women the opportunity to represent themselves. . In everything we do, from a small schoolhouse high in the Himalayas to our head offices here in Australia, we must keep checking ourselves so women are given every opportunity to thrive.

Gender equity is a work in progress, and every organisation needs to have targets, milestones, policies and reminders to keep us in check.

The evidence is clear: strong development, inclusive growth and women’s rights are fundamentally bound together, in everything from economic growth, access to education, food and health security to the environment, and good governance.

—

Helen Szoke is Chief Executive of Oxfam Australia.

This is the third piece in CPD’s ‘Secret Santas for Australia’ series. Each day we will reveal one ‘gift’ of good ideas from a prominent Australian on a policy issue close to their heart. You can see the full set here.

The post Helen Szoke: Gender equality can’t be a token gift appeared first on CPD.

Grand alibis: how declining public sector capability affects services for the disadvantaged | REPORT | December 2015

Today CPD has released a new report called Grand alibis: how declining public sector capability affects services for the disadvantaged.

In the report, authors Kelly Farrow, Robert Sturrock and Sam Hurley argue that government’s role in designing and delivering integrated, flexible and holistic human services is more important than ever, but that the capabilities it needs to do so are under threat.

Summary

Grand Alibis is built around one key question: has contracting out services improved the public sector’s capability to address persistent disadvantage and meet complex needs? It argues that outsourcing has eroded the experience, skills and policy toolkits that the public sector needs to develop the best policy responses – whether these are deployed publicly, privately or as part of mixed models.

The report examines Australia’s outsourced employment services system as a case study. Despite continued efforts to improve outcomes for the most disadvantaged jobseekers, better results remain elusive. As with other key services, designing and delivering more effective employment services is a formidable and complex task. There are no easy answers or off-the-shelf solutions. But the report argues that some consequences of the current model, such as barriers to collaboration and flexibility, make delivering well-funded, integrated and responsive services even more difficult than it needs to be. The disconnection between policy makers in government and the experience, expertise and capabilities needed to develop and deploy better alternatives makes the challenge even greater.

Grand Alibis argues that blurred responsibility for underperforming services means that no one organisation is held accountable when these problems become entrenched. But while government can temporarily avoid blame, its fundamental long-term accountability for advancing wellbeing and addressing disadvantage means it cannot afford to lose the capabilities needed for these tasks.

The report says it is time for a strengthened, ongoing and transparent framework for making decisions about how to design and deliver effective government services – especially in cases of complex, entrenched disadvantage. Following the Harper Review, reforms to increase choice and contestability in human services must acknowledge and protect the public sector capability needed for government to play a range of design, commissioning and delivery roles in an increasingly complex human services landscape.

The report recommends that governments:

Build public sector capability by resourcing government departments to act as effective, persistent policy entrepreneurs, including by trialling different service models, with the skills and staff to develop the evidence and analytics base on an ongoing basis.

Ensure outsourcing passes a Net Public Impact Test, which examines as appropriate the financial, economic, social and administrative impact, including reputational risks, loss of capability and public accountability.

Improve the evidence base by ensuring that the forthcoming Productivity Commission review of human services considers public sector capability to act on disadvantage, and by empowering the the Australian National Audit Office and state counterparts to review confidentiality clauses in outsourcing contracts before execution.

Key links

Links and related material

In March 2015, CPD hosted a high-level social service delivery roundtable to explore some of the more challenging aspects of designing and implementing services to assist vulnerable Australians. The Grand Alibis report draws heavily on invaluable and diverse viewpoints expressed at the roundtable, and on subsequent consultations with many roundtable participants and other experts and stakeholders.

Click here for an illustration of how Australia’s employment services system has evolved since the early 1990s.

The post Grand alibis: how declining public sector capability affects services for the disadvantaged | REPORT | December 2015 appeared first on CPD.

December 1, 2015

Bob May: Learning to think for ourselves is the most powerful gift of all

The best gift I ever received came from a most unexpected source — a high school teacher named Lenny Basser.

It is beyond any doubt that I owe my own happy (and hopefully useful) career to Lenny Basser, my chemistry teacher at Sydney Boys High School in the early 1950’s.

I was then a member of Sydney Boys’ excellent debating team, and we won essentially every inter-school competition we entered into. This meant all the advice I received from the school’s career advisers was that I should become a lawyer.

That all changed with a chemistry class that set my life and career on a different path.

Lenny Basser began his chemistry course by doing something I suspect many teachers would like to do even today — throwing out the textbook (metaphorically of course). He suggested all the people in the honours class were likely to go to university, and therefore his job was not primarily to teach a syllabus but to teach each of us how to ask the right questions and go about fully educating ourselves.

He taught us by not teaching us. Or, more specifically, he taught us not by asking us to memorise knowledge, but by challenging us to learn how to think.

You will, of course, recognise that this is a most unfamiliar way of approaching teaching, and some students really disliked it. Others, like me, thought it was excellent.

I loved it so much I gave up the prospect of what I saw as a much less interesting career in law.

Instead, I pursued life as a scientist, doing work in the spirit suggested by Lenny Basser’s teaching. In his way, he guided me — or allowed me to guide myself — along the first steps of a journey that led to my becoming President of the Royal Society, and to many wonderful people, places and subjects.

This is not just my story. Years later I learned Lenny Basser had taught eight fellows of the Royal Society. One was Australian Nobel Laureate John Cornforth — who, when accepting the Nobel Prize in 1975, highlighted the singular influence of one man, Lenny Basser, in inspiring him to pursue a career in science instead of one in law.

By the way, Lenny Basser wasn’t just a chemistry teacher. For 28 years he also coached the track team. Whether it was sport or the stock market, Lenny Basser was ahead of the curve in new techniques and motivating people.

I do realise that this “gift from Santa” may seem a bit oddly-put, if narcissistic. But what I wish to convey is that, in later years at high school, very systemic thought should be given to the way we teach. We should not simply teach a syllabus and ask students to memorise facts, but rather teach students to think for themselves, and to ask themselves questions about what they’re being taught.

Albert Einstein wrote that schooling is not “simply the instrument for transferring a certain maximum quantity of knowledge to the growing generation” but should develop “those equalities and capabilities which are of value for the welfare” of the community at large. Einstein wanted education to grow minds so that one didn’t become “a mere tool of the community, like a bee or an ant”.

In Australia we can sometimes be a bit like Einstein’s bees and ants, too fixated by what is on the syllabus. We can undervalue teachers and overestimate powerpoints — not just at school, but at TAFE and university too.

Education is about more than debating points and the syllabus. It is about facts, of course. But these facts can change. Climate change wasn’t on my school syllabus and is now the most important question we face.

What is really needed in good schools is more people like Lenny Basser. That is to say, teachers who do not simply regurgitate the textbooks, but those who motivate students to think for themselves.

To put it another way, I believe it is hugely important for students to be guided towards going outside the box, to ask questions about what is going on, not only in science but more generally as well.

Teachers like Lenny Basser have prompted people not just to think, but to act — and perhaps to devote careers to things that enhance the greater good.

These lessons are more important than ever. The world will always need lawyers, as it will need scientists. But for Australia to flourish this century we will also need students prompted to ask difficult questions about the world and our role in it.

Most of all, we will need self-sufficient learners (and thinkers) in an ever-growing sea of information.

This would be the most powerful gift of all.

–

Lord Robert May is a former President of the Royal Society and Chief Scientific Adviser to the UK Government. He is currently Professor at Oxford University, and a member of the UK Government’s Climate Change Committee.

This is the second piece in CPD’s ‘Secret Santas for Australia’ series. Each day we will reveal one ‘gift’ of good ideas from a prominent Australian on a policy issue close to their heart. You can see the full set here.

The post Bob May: Learning to think for ourselves is the most powerful gift of all appeared first on CPD.

Centre for Policy Development's Blog

- Centre for Policy Development's profile

- 1 follower