Centre for Policy Development's Blog, page 31

March 4, 2018

CPD Board member Sam Mostyn on the evolving role of company directors

Influential independent director and CPD Board Member Sam Mostyn delivered the keynote at the Australian Institute of Company Directors’ 2018 Governance Summit on ‘’The evolving role of directors.”

Full text of Sam Mostyn’s remarks available here.

Sam argued that expectations for Australian companies and business leaders to provide better leadership on longer-term economic, social and environmental issues were growing – and that in many cases boards and directors had been too slow to respond.

“One of the reasons we are seeing a transfer of expectation on leadership and change to business, and to organisations outside the political and policy environment, is that we are all living through some of the most complex, global, and interconnected challenges imaginable. This necessarily impacts the role of directors.”

“The confluence of the impacts of climate change, social and economic inequality in its many forms, tens of millions of migrants and refugees on the move across the world, stress on our natural environment and food sources, the rise of small and large artificial intelligence, the future of work, rapid demographic shifts and new geo-political tensions as the world rebalances…

All these sustainability problems, and more, have exposed governments, and our traditional ways of governing and organising, as inadequate to solve these wicked problems and navigate successful futures for our communities.”

Influential non-executive director @sammostyn says there is an opportunity for board directors to step up and take more leadership on issues.

Tune in to see the full interview at 2pm AEST today on Sky News Business Channel 602. #GovSummit18 pic.twitter.com/1cLSPfdlu5

— Sky News Business (@SkyBusiness) March 1, 2018

To live up to these rising expectations, Sam said that boards and directors must cultivate the diversity, culture and expertise they need to grapple with contemporary challenges and build trust and long-term value.

“I believe we are simply not moving fast enough in building effective diversity and inclusion in governance, and embracing qualities like humility, curiosity, the capacity to deal with complexity, a comfort with uncertainty, and a genuine interest in the culture of organisations.

Despite good intentions, and some undoubted leadership from many of our leading companies, our overall progress is frustratingly slow.

This poses both a great risk, and more importantly, leads to missed opportunities.

…Increasingly, our board rooms are needing to create safe spaces for complex and difficult conversations, and a comfort with challenge and engaging with the broader world – getting insights which reduce risk of future problems.

In addition to our commitment to the success of the organisation, and demonstrated competence and expertise, directors need to be able to be independent, authentic, prepared to speak up, and prepared to learn.”

There is a significant shift underway. Good stewardship will be enacted by diverse and inclusive boards who avoid groupthink.

The evidence of gender #diversity is well established. Reaching 30% targets for women on boards is unlikely to be met by end of this year @sammostyn pic.twitter.com/TrAIuLQHrd

— AICD (@AICDirectors) February 28, 2018

Sam highlighted climate-related risks as one prominent issue where boards had been slow to respond, despite mounting evidence about the economic and environmental impacts of climate change.

“When it comes to the changing world we live in, there is one conversation I believe boards weren’t having enough of in recent years – the topic of climate-related risks.

Few boards have laid strong foundations for measuring and disclosing these risks.

It has generally taken intervention by regulators – Bank of England Governor Mark Carney in the UK, and more recently APRA’s Deputy Chair Geoff Summerhayes, joined now by RBA Deputy Governor Guy Debelle – who have asked uncomfortable questions and opened up a new conversation about the risks and opportunities presented by climate-related financial risks.

Boards didn’t need to wait for the lawyers and the regulators to open up this conversation, but many did.

I observed at close range the role of the Centre for Policy Development in the past year in bringing together a diverse group of business leaders, legal experts and regulators, to start a conversation about climate risk and director’s duties in order to be better prepared as the issues come into sharper focus.

This reinforced to me that boards should be more discerning and strategic in how they engage in the policymaking process. Boards shouldn’t hesitate to take the road less travelled and break away from the ‘safe’ political options, where there is a clear imperative for engagement by the company, and a belief that good policy can be assisted by broader perspectives.”

Media coverage

Sam’s remarks were covered in the SMH and AFR.

She also spoke about the key themes in her remarks with Sky News Business Editor James Daggar-Nixon.

Related reading

Legal opinion and roundtable on directors duties and climate risk – CPD, October 2017

Can democracy deliver? – CPD Menadue Oration by Marty Natalewgawa, November 2017

A sense of purpose – BlackRock Chair Larry Fink’s 2018 letter to CEOs, January 2018

The post CPD Board member Sam Mostyn on the evolving role of company directors appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

February 18, 2018

A Creeping Indigenous Separation | DISCUSSION PAPER | February 2018

Over the past two years, CPD has highlighted inequity in the funding of Australia’s schools and a growing concentration of disadvantaged students in poorer schools. Uneven Playing Field (2016) and Losing the Game (2017) used My School data to reveal how our shared schooling experience in Australia was slipping away.

In a Class of Their Own is a new series that extends this analysis, firstly in relation to Indigenous students. It does so a week after we observed the 10th Anniversary of the Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples and consider how well our country is closing the gap of Indigenous disadvantage.

Some inroads have been made in recent years in achieving better educational outcomes for Indigenous students. This paper does not devalue these achievements or the political and policy vision that underpins them. Notwithstanding, My School and other data point to gradual but significant trends that will shape the education of Indigenous students over the long term.

While most schools have increased their enrolment of Indigenous students in both absolute and percentage terms, the proportion of Indigenous students is far greater in disadvantaged (lower Socio-educational Advantage – SEA) schools.

These trends are magnified in regional areas where the majority of Indigenous students attend school. Higher SEA schools are not enrolling an increasing share of the Indigenous student population. In fact, they also have a lower proportion of the most disadvantaged students.

Where schools and school sectors are in competition, the more advantaged (higher SEA) schools have reduced their share of Indigenous students, while two-thirds of less advantaged (lower SEA) schools have increased their share.

Closer analysis shows that the number of Indigenous students at many schools does not reflect the size of the local Indigenous population. Lower SEA schools have disproportionately more Indigenous enrolments, higher SEA schools in all sectors have (with some exceptions) disproportionately fewer.

In short, the dynamics of our school system – rather than promoting inclusion and equity – are increasingly putting Indigenous students in a ‘class of their own’.

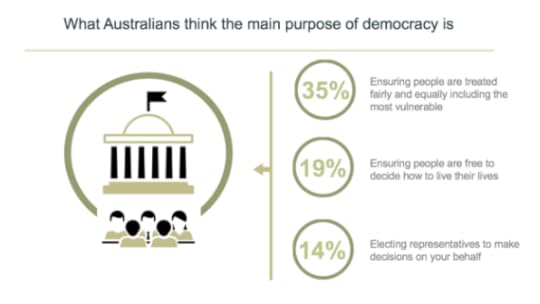

Why might this matter? CPD’s research on renewing Australia’s democracy, conducted throughout 2017, found that one in three Australians believe the main purpose of democracy is about “ensuring that all people are treated fairly and equally, including the most vulnerable in the community”.

Schools are critical to this and play a pivotal role in fostering a more equal and inclusive society. For schools to be effective in promoting cohesion through shared experience, understanding and opportunity, the networks they support and cultivate must reach across social and racial divides. In this way, schools mitigate social and cultural dynamics that might otherwise create and reinforce structural difference and discrimination between groups and individuals.

The evidence presented in this discussion paper suggests that the capacity of our school system to act as catalyst for inclusion, equity and opportunity for Indigenous students is weakening. Rather than being places which bring people and communities together, evidence suggests that schools are yet another place where children grow further apart.

In addition to the negative impacts on individual achievement and opportunity, the increasing separation of Indigenous students from other Australian school students has broader societal implications.

The paper does not offer specific policy prescriptions but aims to provide a conceptual first step and pointers for future policy action that might address what is a significant and concerning challenge to an equitable and inclusive Australia.

Key Documents

Full report

Introduction

Op-ed

Media coverage

Progress made on Indigenous retention rates masks growing racial divide at schools, The Guardian, Michael McGowan.

Most Indigenous students consigned to schools with least capacity to help, The Guardian, Chris Bonnor.

Key links and related reading

Losing The Game: State of our Schools in 2017, CPD Report 2017, Chris Bonnor and Bernie Shepherd

Chris Bonnor and Bernie Shepherd published a piece on their latest findings in The Guardian.

The Australian Financial Review’s Tim Dodd spoke with report co-author Chris Bonnor

Is Gonski 2.0 skilful trickery or chance to get schools funding right? Expert panel responds, The Guardian, Chris Bonnor

Uneven playing field: the state of Australia’s schools, CPD Report 2016, Chris Bonnor and Bernie Shepherd

The local school is in decline and stratification is to blame, Sydney Morning Herald, Ross Gittins

‘The inequity is worsening’: a tale of two schools and a school funding debate, The Age, Henrietta Cook

The post A Creeping Indigenous Separation | DISCUSSION PAPER | February 2018 appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

Most Indigenous students consigned to schools with least capacity to help

CHRIS BONNOR published in The Guardian

19 February 2018

Layers are being created within and between Indigenous communities, making closing the gap ever more difficult

Most Indigenous children attend schools well down the socio-educational ladder. Photograph: Helen Davidson for the Guardian

We are now into the tenth anniversary of the strategy to close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia. Last week saw a report on progress, a subdued celebration on scattered achievements and copious hand-wringing over endemic failures.

It seems that amongst the Closing the Gap target areas it is school education where some celebration is justified – with some gains in numeracy, reading and school retention. There is still a long way to go but any progress will be a welcome boost for schools more used to wearing all the blame for low levels of student achievement.

Indigenous education has more than its share of set-backs but we also hear about heroic efforts by teachers to turn the numbers around. The work done by Chris Sarra and the Stronger Smarter Institute is deservedly well-known. Many schools are stand-outs and new learning designs are challenging what schools should do, and what success should really look like.

But alongside our efforts to close the gap our school system operates in a way which keeps it as wide as ever, in the process almost mocking efforts at the school level. Most concerning is how we are consigning most Indigenous students, especially the strugglers, to the schools with the least capacity to address their pre-existing disadvantage.

These are the schools at the bottom end of the school socio-educational (SEA) ladder which we have created in Australia. It is a regressive hierarchy, affecting the disadvantaged in general but very visibly so with most Indigenous students. We are now creating layers within and between Indigenous communities, just as we are with other Australians. Those who can will scramble up the ladder; those who can’t will struggle – increasingly in a class of strugglers, a class of their own.

How does this play out on the ground? Schools with students who are advantaged accumulate the social, cultural and even financial capital of their supportive and resourceful parents. Schools which enrol an increasing proportion of disadvantaged students gradually lose the resource of higher-performers and role models. Teacher experiences and expectations, as well as curriculum offerings and access, can change and resources might be scarce. Teachers increasingly have to consolidate skills and knowledge already traversed. The odds against making the much-needed breakthroughs mount up.

This is what we are especially doing to Indigenous students. Most attend schools well down that socio-educational ladder: lower SEA government and Catholic schools and some remote Independent schools. The government schools face the biggest challenge because the two private sectors enrol the more advantaged from Indigenous communities. As always, some students emerge as winners and the schools can sometimes tick an equity box, while compounding bigger problems elsewhere.

There are urban-regional contrasts: the trend to residualise Indigenous students is magnified in regional areas where a majority of them attend school. The most disadvantaged regional schools continue to have high Indigenous enrolments. The reality for these schools is that there is no one below them on the school ladder. They don’t win the more advantaged students from the higher rungs and must accept anyone on the way down.

This is also more noticeable outside the cities because the successful and the strugglers live almost side-by-side, but their children often go to very different schools. Centres such as Coffs Harbour, Orange, Tamworth-Gunnedah and Wagga Wagga offer a considerable choice of schools. What is sometimes a black-white divide is not so much a matter of active discrimination; it is the level of school fees which sorts everyone out. There are very few Indigenous students in Anglican schools, more in community Christian, Catholic and higher SEA government schools – but most are in other government schools.

Why does it all matter? It impedes what could be progress towards closing the gap. It highlights an unhappy racial aspect atop longstanding, if loose, layers of social class. It inhibits the development of interpersonal understanding and social harmony. It limits the development of social and cultural capital. Schools become less able to address the most intractable problems faced by many Indigenous families. We just won’t improve equity for all if we persist in compounding disadvantage.

While an experience of schooling is shared by all, Indigenous and non-Indigenous children increasingly don’t share the same school. Closing this gap needs to be part of the obligation of every school: we will only do it if we increase the number and proportion of our schools which are obliged to be open to children from every family in every circumstance in every part of Australia.

It seems that concerns about slow progress towards targets have triggered an overhaul of the Closing the Gap strategy. They will reshape the targets, maybe broaden their reach, widen the consultation and be happy enough with a job well done. Little will change unless they come to grips with a framework of schools intent on widening the gaps.

Chris Bonnor is a Fellow of the Centre for Policy Development and a director of Big Picture Education Australia.

The post Most Indigenous students consigned to schools with least capacity to help appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

February 4, 2018

Big, impersonal and opaque: how Jobactive is failing jobseekers

ROB STURROCK published in Inside Story

1 FEBRUARY 2018

A new strategy would start by recognising that the market alone can’t help many jobless Australians find work

What is government’s role? Labor frontbencher Anthony Albanese with prime minster Malcolm Turnbull. Mick Tsikas/AAP Image

A decade and a half ago, in mid 2003, the federal government stoppeddoing something that governments have done continuously since 1946. It would no longer help unemployed people find jobs, and would instead give the task to a group of charities and private providers. Justifying this transition to a scheme it called Job Network, the Howard government argued that finding jobs for the unemployed wasn’t core government business. “If that’s not a core responsibility,” responded Labor’s Anthony Albanese, “then what is?”

The question is still timely. The multi-billion-dollar employment services market offers very patchy results for the hundreds of thousands of jobseekers in the system. Through Jobactive, the post-2015 version of the scheme, the federal government pays $7.3 billion over five years to sixty-five private and not-for-profit service providers to assist about 750,000 jobseekers each year in over 1700 locations. With that amount of public money, and with fifteen years in which to fine-tune the service, Jobactive should be an exemplar of how outsourced human services should work in a mature market.

A big, standardised system churning through the unemployed and rewarding short-term placements with individual payments will not help produce a skilled, entrepreneurial, resilient workforce.

But like its predecessors Job Network and Job Services Australia, Jobactive is a big, impersonal system struggling to deliver high-quality services for the individuals using it. Despite the occasional media report criticising elements of the program, it largely escapes scrutiny. It is a system, replete with grand alibis, for which none of the mutually dependent participants inside and outside government takes overall responsibility.

The Department of Jobs and Small Business will soon consider the successor to Jobactive. Simply creating Jobactive II would be a mistake and a missed opportunity: both the government and the opposition need to develop policies that put jobseekers’ livelihoods and aspirations first, and that means working out the best role for government in helping the unemployed, including learning from promising initiatives here and overseas.

Removing human services from direct government control and embedding them in competitive marketplaces was a key element of the microeconomic reforms of the 1990s. That wave of deregulation, privatisation and competition-based reform was kickstarted by Labor and intensified under the Coalition. In the process, we bade farewell to the Commonwealth Employment Service and welcomed Job Network.

Much was promised when the employment-services market was created. Government and industry saw it as a more cost-effective way of delivering social services. Private and non-government organisations, they reasoned, had better on-the-ground knowledge of the labour market and smarter ways of “activating” jobseekers. The new market would keep the long jobless queue moving by finding “real” jobs for the unemployed.

By 2015, according to an analysis I prepared with colleagues at the Centre for Policy Development, the system was operating at two speeds. For unemployed people with comparatively good skill sets and little disadvantage, the results were okay. For the disadvantaged jobseekers struggling to overcome multiple and often complex personal barriers, the outcomes were poor.

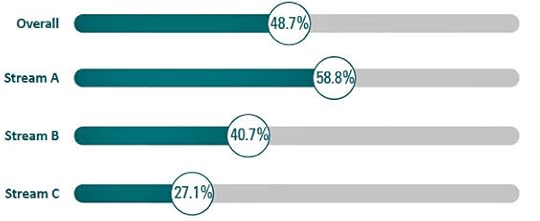

The most recent Jobactive data from the Department of Employment, which covers the twelve months to March 2017, confirms that story. Jobseekers are classified into Streams A, B or C — Stream A being those who are most employable and C being those most in need of assistance because of disadvantage. Across the three streams, 49 per cent of jobseekers are employed three months after participating in Jobactive. For the unemployed in Stream A (those with the least disadvantage), the average rate is 59 per cent; for jobseekers in Streams B and C, as the chart shows, this drops off sharply.

Employment outcomes by stream, three months after Jobactive

Source: Department of Employment, April 2016 to March 2017

Stream B jobseekers need more assistance to find a job because they lack skills or suffer from other difficulties. Stream C takes in the hardest-to-place jobseekers, including the most disadvantaged long-term unemployed, people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, sole parents and poorly educated applicants. Only 27 per cent of people in Stream C found work in the twelve months to March 2017. Almost 44 per cent remained unemployed, and 29 per cent had left the labour force.

Where they do find work through Jobactive, it tends to be insufficient for their needs. Of the 27 per cent in Stream C who did find work, 25 per cent found a permanent role and 62 per cent found a casual, temporary or seasonal role. On average, 53 per cent of Stream C job-getters are seeking more work. The number is highest for those with part-time work, two-thirds of whom want more hours.

Why, fifteen years after the introduction of a fully outsourced system, are we left with an expensive, two-speed system? It’s no mystery: the system is not built for jobseekers, it is built for government to keep the jobless queue moving while reducing long-term welfare dependency.

The Department of Employment purchases services from for-profit and not-for-profit providers whose operations are prescribed in confidential, highly detailed contracts. Although the department has the job of monitoring service providers, poor performance is often overlooked. The loads of compliance data it collects from the providers track the behaviour of jobseekers more than the effectiveness of providers or their long-term impact on their clients.

Nor does the funding model encourage a continued investment in jobseekers. The department pays providers largely on the basis of outcomes achieved for individual jobseekers, with payments varying according to the type and length of job placement. Regional locations have higher loadings, and providers also receive payments for placing jobseekers in work-for-the-dole projects. With a focus on getting the cheapest rate per jobseeker, the department proudly claims that the 2016–17 target of $2500 per outcome was significantly outdone by the actual figure, $1453 per outcome.

Most providers rely on low margins and high turnover, focusing on easier-to-place clients while side-lining the too-hard cases despite the offer of higher incentives. This has been a longstanding problem in the system: providers are naturally looking for the most efficient way to allocate resources, and investigations have shown that some of them cut corners and rort the system. The recent collapse of one of Britain’s major public contractors, Carillion, offers a cautionary tale about misplaced faith in contracting, and the perils of focusing on costs over outcomes.

The system churns through jobseekers like customers at a fast-food cafe, with frontline staff relying mostly on standardised services and support options. Research from 2016 shows that the average caseload for surveyed staff was 147.8 clients, with each of them seeing nearly nineteen clients per day on average, either individually or in groups. Thirty-six per cent of frontline staff have no more than a TAFE qualification or vocational certificate, the research found, and almost a quarter have no post-secondary qualifications.

Among the biggest failures of the employment-services market is that different providers offer similar services, leaving jobseekers with little genuine choice. This standardisation is exacerbated by the fact that Jobactive lacks specialist service provision. When the Refugee Council of Australia examined the program’s operation in key migrant communities in August 2017, it found that refugees with no English-language skills are being incorrectly placed in Stream A, where the lowest level of support is provided. The creation of the Jobs Victoria Employment Network was partly a response to the lack of specialist federal help for vulnerable jobseekers.

Jobseekers’ negative comments about Jobactive in satisfaction surveys aren’t surprising. In the latest surveys, covering the year to March 2017, only 55 per cent of all jobseekers were “satisfied or very satisfied” with the overall quality of service. Only 38 per cent were satisfied or very satisfied with the help they received in finding a job, and 37 per cent with the help they received in gaining skills for work. A shade over half of these jobseekers didn’t believe that the service was suited to their personal circumstances. No private business would tolerate such low customer satisfaction levels, but for Jobactive agencies it is the satisfaction of government that matters.

Even though these providers deliver public services, and even though obvious problems exist, they are shielded from public scrutiny by the commercial-in-confidence provisions in their contracts with the department, which also protect them from freedom of information requests.

With a federal election looming, both major parties must come up with new, compelling answers to Albanese’s question, which lingers like Banquo’s ghost. Just what is the role of government in helping people find and keep a job? What does the government owe the citizens it serves, especially the vulnerable and disadvantaged?

Members of the public already have their own answers. In October last year the Centre for Policy Development ran an online survey designed to understand community attitudes to government. The sample was representative of community demographics. The 1025 responses collected by Essential Media included clear messages that the major parties should consider carefully.

People think that providing health, education, social security and other essential services, and ensuring shared economic prosperity, are among the most important tasks of the federal government. They think that job policies should be a major priority for the federal government. And they are deeply sceptical about outsourcing social services.

In fact, more than four out of five respondents thought it was important for the government to retain the skills and capability needed to directly deliver social services. Why? Because respondents thought government was a “better provider” of social services than charities or not-for-profits in terms of cost efficiency, accessibility, accountability and affordability for users. This wariness of outsourcing social services is deeply held: credible attitudes research from 1994, conducted by the Economic Planning Advisory Commission for prime minister Paul Keating, shows similar sentiments.

None of this is any surprise. Unemployment might be relatively low at the moment but underemployment is high. A growing number of Australians are moving into the gig economy, with its agile but insecure work. Inequality is on the rise and, faced with stagnant wage growth, people are placing a higher premium on receiving quality services. Automation and the use of artificial intelligence will change, destroy and create jobs, but our capacity to harness this disruption is nascent. If Australians genuinely believe that government has a role in the labour market and in creating shared prosperity, then it is only fair that we revise the way we provide social services.

A new strategy for reform begins with a statement of the obvious: markets alone will not produce the social gains we need. A big, standardised system churning through the unemployed and rewarding short-term placements with individual payments will not help produce a skilled, entrepreneurial, resilient workforce. Nor will it help the most disadvantaged. Government has a larger and better role to play, and some in the business community already agree.

Which leads us to how we can use public sector values and talents more effectively. Public and private capabilities should not be viewed as competing: they are essential components that should work together. Australia’s public sector remains unique in its mission and its public service values. The Department of Jobs and Small Business has a sound understanding of the labour market but could offer more services with the right re-investment in skills and capacity. It could improve accountability and transparency, and steward a system to produce results in the community interest. But its own memory of alternative service models will need strengthening; its policy and leadership capability have been run down over two decades by imposed efficiency dividends.

Promising initiatives at home and abroad offer valuable principles for improving services for jobseekers. The best way to make services personal is to make them local: a national framework for helping the unemployed will be more effective if it links to organisations that understand economic conditions in local areas, including local employers, associations and providers. Local service delivery also allows strong partnerships and networks to be built on the ground, integrating services better than market incentives ever could. Effective local programs include the Brotherhood of St Laurence’s Given the Chance scheme; with over 300 refugees having found work since 2013, it outperforms Jobactive.

It’s also important to experiment with new ways of delivering services that can scale up over time. A German program for mature-age workers has used grant-based funding and lower caseloads to invest in clients in a more personalised manner. What began as a small, voluntary program expanded organically to become an almost nationwide endeavour, with the job take-up rate moving from 26 per cent to 35 per cent over four years. Many German job centres are shared municipal and federal government facilities, showing the benefit of collaboration across levels of government.

There is no reason this could not be done in Australia. Parramatta’s Socially Sustainable Framework identifies how the city council can help with social and economic challenges, including assisting disadvantaged jobseekers. In the right mix, local intelligence combined with the resources of the federal government could work wonders. The Department of Employment could embed itself in local offices around the country, collaborating with its local government counterparts to deliver tailored services using the best service-design principles. It could start with a focus on the most disadvantaged postcodes in Australia, where unemployment is most rife.

Assistance must also be enduring. Existing services focus on the unemployed or those who have very recently lost their jobs in specific manufacturing sectors. Government should develop a national policy framework that addresses unemployment, underemployment and insecure work as a whole. In Sweden, Job Security Councils are a “continuous presence” in the labour market, helping workers through career transitions and redundancy rather than waiting for them to appear in the unemployment queue. Swedish unions and industry work in concert to create a resilient workforce that can transition through tough times.

The most effective way to reform the system is to evolve it over time. The National Disability Insurance Scheme provides a cautionary tale of the problems created when a big rollout is rushed. Pilot programs should be allowed to work quietly and calmly in target communities, helping specific groups, investing over a long period, and collecting good-quality data to compare with Jobactive. Direct involvement would make the Department of Employment a smarter purchaser of services, and improve its policy-development capacity. The department already uses pilot programs to test new services: its ParentsNext trials help parents currently out of the workforce to find jobs and education.

This evolutionary approach should lead to a comprehensive national service framework that ties together new pilots and other initiatives into a proper strategy for assisting jobseekers. One viable medium-term alternative could be greater public provision of services to the most disadvantaged jobseekers, leaving market-based providers to assist the less disadvantaged. With more trials, we’ll have more data and better options for reform.

Employment services play a pivotal role in ensuring that all Australians have fair and equitable access to economic opportunity. For too long we’ve focused services on managing the unemployment queue rather than the individuals in it. We’ll limit our own future prosperity and exacerbate social divisions if we don’t fix a service that is obviously not working. ●

The post Big, impersonal and opaque: how Jobactive is failing jobseekers appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

Terry Moran AC, CPD’s Chair and Former Head of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet discussed the leaked cabinet documents with Leigh Sales

TRANSCRIPT:

LEIGH SALES, PRESENTER: The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet has now launched an urgent investigation into what happened. Terry Moran headed that department from 2008 to 2011, a period covered by these papers.

He joined me moments ago from Melbourne. Terry Moran, what’s your reaction to this huge security breach?

TERRY MORAN, DEPT OF PRIME MINISTER AND CABINET, 2008-2011: Great surprise, and it had to have come from somewhere within the public service because it spans governments of both sides.

And whoever was responsible for selling a couple of filing cabinets, which I think were locked, that must have been heavy with all the papers in them, without checking what was in the filing cabinets. Apart from anything else, you ought to be found and sacked.

LEIGH SALES: Is there any precedent for this sort of thing? Do people normally take it upon themselves to sell government furniture for example?

TERRY MORAN: Well, I can recall a few instances in the past where personnel files in filing cabinets have ended up on tips, but I’ve never heard of, as I think the ABC is putting it, thousands of pages of Cabinet documents being left in a filing cabinet and put out in this way.

LEIGH SALES: Well, you used to be the top public servant in Canberra as the head of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. What would you do now if you were there running this place and this had happened on your watch?

TERRY MORAN: Well, sad I would to have to say Leigh, I’d ring up the ABC and ask for the Commonwealth property back.

But getting past that point, because it remains Commonwealth property. I would probably bring the AFP in to do a major investigation. And I can’t know what sort of documents they are. They might have numbers on them that would identify them in terms of the people who received them. And then, having got the investigation under way, if this hadn’t already happened recently, I would have hastened efforts to switch the Commonwealth entirely to a digital system for dispatching papers to Minister and authorised recipients.

LEIGH SALES: How difficult or otherwise do you think it will be for authorities to actually track down the path for these documents?

TERRY MORAN: If they are Cabinet documents they should have some identifier as to who it was intended would receive that particular copy of the document. But then if you work back from the sale records of whatever department disposed of the filing cabinet, you might also be able to find out who put the collection of papers together and failed to surrender them upon a change of government or a change of minister, as they’re supposed to do.

LEIGH SALES: These documents reveal some of the inner workings of governments that were in our quite recent past. The normal rule is that Cabinet documents are only released 20 years after the time that the events took place. Why is there that 20-year rule?

TERRY MORAN: Well, in Australia, our Cabinet system, and it’s similar in this respect to the British system, the Canadian system and the New Zealand system.

Our Cabinet system depends upon ministers around the table being able to have very frank conversations about what they think of particular proposals, sometimes disagreeing very strongly with each other about what should be done and if an insight into that free speech so to speak, at that level was available, that would inhibit the sort of discussion that good decision-making I think, actually requires.

LEIGH SALES: There is always a tension between the Government’s need for secrecy, as you just explained it, and the public’s right to know what their leaders do behind closed doors in their name. Where do you come down on the issue of the publication of this material?

TERRY MORAN: Well, I think John Faulkner’s reforms to shift us from 30 years to 20 years were a very, very good idea – although I was a bit cautious about them at the time – and having got there I think we should keep going.

Because I don’t think that there is any magic number about 20 years. Why not go to 15 over time? Secondly, there are many things that go into the Cabinet process. This is not in the national security area, it is not in economic policy, but mainly in spending areas, there are many things that are really little more than business cases or feasibility studies. And the quality of those documents should be tested by releasing them after the Government has made any decision it does make to go ahead with those initiatives.

And then people can say, “Oh, well now I understand what was intended with this particular piece of transport infrastructure”, for example.

LEIGH SALES: Terry Moran, many thanks for your insights this evening.

TERRY MORAN: Thanks Leigh.

The post Terry Moran AC, CPD’s Chair and Former Head of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet discussed the leaked cabinet documents with Leigh Sales appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

December 11, 2017

What Do Australians Want? Active and Effective Government Fit for the Ages | DISCUSSION PAPER | December 2017

Today CPD releases its latest research – a new discussion paper called “What do Australian’s Want? Active and Effective Government Fit for the Ages.”

This paper draws on new attitudes research commissioned by CPD on Australian attitudes to democracy and to government. It also features insights from a special roundtable on Australia’s democracy convened by CPD in November, as part of our 10th Anniversary Event Series.

We think this work is important and comes at a vital time. There are reminders every day that our democracy is struggling under the strain of both new and old challenges. The arduous and painful path to marriage equality despite broad public support is one example. The rolling crisis over the citizenship status of parliamentarians is another. And this isn’t a temporary blip or a recent phenomenon. For a decade or more we’ve been treading water while the big challenges of our time – climate, inequality, innovation, growth – have gathered steam. We need better answers, and we don’t have any more time to lose.

What is clear from this research is that Australians think reinvigorating our democracy is a pressing and overdue task. This is not just a matter of reforming the system of government and its processes. It also means ensuring the best contemporary policy ideas rise to the top.

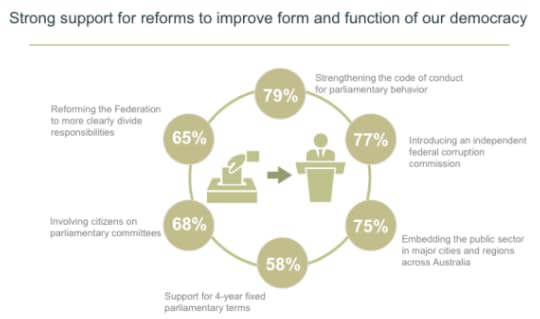

Reforms to the form and function of Australia’s democracy strongly backed by Australians include a federal anti-corruption commission (77%), four-year parliamentary terms at the national level (58%), more diversity in the parliament (59%) and a tougher code of conduct for parliamentarians (79%), embedding the public sector in more parts of Australia (75%), putting citizens on parliamentary committees (68%), giving public agencies more independence from the government of the day (55%), and a constitutional convention on how we can update the Australian Constitution for the 21st Century (57%).

Reforms to the form and function of Australia’s democracy strongly backed by Australians include a federal anti-corruption commission (77%), four-year parliamentary terms at the national level (58%), more diversity in the parliament (59%) and a tougher code of conduct for parliamentarians (79%), embedding the public sector in more parts of Australia (75%), putting citizens on parliamentary committees (68%), giving public agencies more independence from the government of the day (55%), and a constitutional convention on how we can update the Australian Constitution for the 21st Century (57%).

These ideas are important – and in a sense, they are the easy part of renewing Australia’s democracy, because Australians want these reforms. The more difficult challenge is developing an agreed vision and purpose for our future which can breath new life into our democracy. But CPD’s research shows there is fertile ground here, too. Australians also want a rejuvenated public sector that plays an active and effective role in policy development and the delivery of human services. They want business to invest in building shared, sustainable value. They care about the wealth of nature, not growth at all costs, and want community-led change on our biggest policy challenges. They want a stable democracy, but not a static one that refuses to change with the times. They want programs that work and are rigorously evaluated by government, not outsourced systems like Jobactive that aren’t helping Australia’s most vulnerable job seekers. Above all, they believe in Australia and believe we can and must do better if democracy is to deliver for all.

It’s time to respond to a clear community desire to reform our democratic system and processes, and for fresh policies driven by better ideas, not ideology.

As part of the research, CPD partnered with Professor Glenn Withers from the Australian National University and Essential to replicate two previous studies on public attitudes to government. Professor Withers was the lead researcher on both these studies, and advised on the third study conducted exclusively for CPD by Essential in October 2017 (online survey based on 1,025 respondents).

Key Documents

Full discussion paper

Foreword

Media release

Media coverage

Laura Tingle, Australian Financial Review

Doug Dingwall, The Canberra Times

Anne Davies, The Guardian

David Donaldson, The Mandarin

Harley Dennett, The Mandarin

We would love to hear your feedback on our discussion paper:

Name

First

Last

Feedback

This iframe contains the logic required to handle Ajax powered Gravity Forms.

Key links and related reading

Special roundtable on Australia’s democracy convened by CPD, 10 November, Melbourne

Full agenda, CPD’s Roundtable on Democracy, 10 November, Melbourne

Participant list, CPD’s Roundtable on Democracy, 10 November, Melbourne

Rapporteur Summary, CPD’s Roundtable on Democracy, 10 November, Melbourne

Terry Moran AC, CPD’s Chair, addressed some of the themes of CPD’s attitudes research in a speech for IPAA Victoria on 21 November 2017. Read the speech here, along with the coverage in The Guardian and The Mandarin.

Can Democracy Deliver?, John Menadue Oration by Marty Natalegawa, 2 November, Melbourne

Democracy as a piano, Robert Menzies

Still lucky – why you should feel optimistic about Australia and its people, Rebecca Huntley, Communities in Control Conference 2017

How People Vote, Niko Kolodny, Boston Review

20 of America’s top political scientists gathered to discuss our democracy. They’re scared, Sean Illing, Vox

The post What Do Australians Want? Active and Effective Government Fit for the Ages | DISCUSSION PAPER | December 2017 appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

November 29, 2017

Building a Sustainable Economy | PUBLIC FORUM | November 2017

Sam Mostyn, Geoff Summerhayes, Christina Tonkin & Steven Skala.

On 29 November, CPD hosted the final event in our special 10th anniversary series – a public forum in Sydney tomorrow on the theme ‘Building a sustainable economy.’

CPD’s Sustainable Economy Program focusses on the need to build a fair, sustainable and prosperous economy, including by properly considering the long-term drivers of risk, prosperity and wellbeing.

Some of the most pressing challenges involve preventing and responding to climate change. Last year we commissioned and released an influential legal opinion on company directors’ obligations to consider climate risk. In November 2017 we kicked off a new research stream with a discussion paper on how business and investors can go about scenario-based analysis of climate risks.

Our Building a Sustainable Economy event was a chance to reflect on these issues and broader challenges and opportunities around climate and sustainability. We were joined by four high-profile speakers with a unique perspective to provide on these issues:

Geoff Summerhayes, Executive Member at APRA, gave a ground-breaking speech on the financial implications of climate change earlier this year – the first of its kind in Australia

Christina Tonkin, Managing Director of Loans and Specialised Finance at ANZ, the first Australian bank to commit to climate disclosures in line with the new global Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures framework

Steven Skala AO, newly appointed Chair of the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, the specialist clean energy financier established by the Australian government

Sam Mostyn, a leading independent director and sustainability leader and member of the global Business and Sustainable Development Commission.

After providing some opening remarks, our speakers were joined by Bloomberg’s Emily Cadman for a panel discussion and Q&A. They spoke about climate and broader sustainability challenges – including the need to better understand the financial impacts of sustainability-related risks and opportunities; the growing importance of reputational risks and social license; the global relevance of the importance of the Sustainable Development Goals; and the important role business leaders can play by speaking out and supporting better policy responses to these long-term challenges.

Extracts from our speakers prepared remarks are below, along with links to full versions and media coverage. A recording of the panel discussion and Q&A will be available shortly.

CPD would like to thank Sarah Barker, Maged Girgis and the team at MinterEllison for hosting the event, and panellists who contributed to an engaged and candid discussion.

Media coverage

APRA quizzes financial sector over climate change risk preparations, Alice Uribe, Australian Financial Review

APRA stress tests for climate change, Michael Roddan, The Australian

APRA’s Summerhayes says weight of money now driving response to climate change, Peter Hannam, Sydney Morning Herald / The Age

Banks warned of regulatory action as climate change bites global economy, Michael Slezak, The Guardian

Banks and insurers must prepare for climate-related risks: APRA, Penny Timms, ABC Radio (Transcript here)

Key links

The weight of money: A business case for climate risk resilience, Geoff Summerhayes, 29 November 2017

Climate horizons: next steps for scenario analysis in Australia, Sam Hurley and Kate Mackenzie, CPD Discussion Paper, 28 November 2017

Final Recommendations Report, Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, June 2017

Key quotes and speech extracts

Geoff Summerhayes, APRA

“Shifts in market sentiment have increased the risk of asset value volatility, and the potential for stranded assets. Institutions that fail to adequately plan for this transition put their own futures in jeopardy, with subsequent consequences for their account holders, members or policyholders.

…the transition to a low carbon economy is underway, and that means the so-called transition risks are unavoidable: changes to market sentiment, new financial or environmental regulations, or the emergence of new technologies with the potential to prompt a reassessment of the value of a large range of assets, and consequently the value of capital and investments. But that doesn’t mean these risks are unmanageable, or that the impacts on businesses and the wider economy need be negative.”

“APRA supervisors have begun to ask questions of regulated entities. Initially, these have related primarily to awareness: is the entity aware of APRA’s comments about climate-related risks? Has it investigated or planned to investigate the issues raised? And if it has investigated them, is action required?”

“Increasingly, APRA will expect more sophisticated answers, especially from well-resourced and complex entities. As APRA identifies entities with better practices, we will further engage those institutions to gain a deeper understanding of how they approach, measure and manage these risks, and share this as industry guidance.”

“Externally, APRA has commenced discussions with Treasury, as well as fellow regulators ASIC and the RBA, on the sustainability and financial risk dimensions of the economy related to climate change. Through the creation of an interagency initiative, we intend to focus on information-sharing and improving our understanding in this area.”

Christina Tonkin, ANZ

“Our stakeholders are increasingly interested in a broader view – a more-holistic story about how we are creating value over time and the opportunities and challenges impacting our future.”

“We’ve been spending a lot of time reflecting on our purpose as an organisation, and how we can best use our skills, capabilities and relationships to have a positive impact. This inevitably means taking a stand on important issues – even when it comes at a cost… We want to be known as an organisation that shapes a future where people and communities thrive by helping to create a balanced, sustainable economy in which everyone can take part and build a better life.”

S teven Skala AO

“It is the view of our Board is that we must make each dollar go further, to have a much larger impact on decarbonising our economy, to further fill the gaps where it is needed. I can report to you that businesses have watched first movers in their industry cut costs and improve productivity using CEFC finance and are now coming to us to do the same.”

“Our objective is to continue to play a serious role in stimulating the reduction of carbon emissions, by ensuring the benefits of cleaner generation are delivered across the economy, alongside a much stronger focus on reduced energy consumption.”

The post Building a Sustainable Economy | PUBLIC FORUM | November 2017 appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

Building a sustainable economy | PAST EVENT | November 2017

Sam Mostyn, Geoff Summerhayes, Christina Tonkin & Steven Skala.

On 29 November, CPD hosted the final event in our special 10th anniversary series – a public forum in Sydney tomorrow on the theme ‘Building a sustainable economy.’

CPD’s Sustainable Economy Program focusses on the need to build a fair, sustainable and prosperous economy, including by properly considering the long-term drivers of risk, prosperity and wellbeing.

Some of the most pressing challenges involve preventing and responding to climate change. Last year we commissioned and released an influential legal opinion on company directors’ obligations to consider climate risk. In November 2017 we kicked off a new research stream with a discussion paper on how business and investors can go about scenario-based analysis of climate risks.

Our Building a Sustainable Economy event was a chance to reflect on these issues and broader challenges and opportunities around climate and sustainability. We were joined by four high-profile speakers with a unique perspective to provide on these issues:

Geoff Summerhayes, Executive Member at APRA, gave a ground-breaking speech on the financial implications of climate change earlier this year – the first of its kind in Australia

Christina Tonkin, Managing Director of Loans and Specialised Finance at ANZ, the first Australian bank to commit to climate disclosures in line with the new global Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures framework

Steven Skala AO, newly appointed Chair of the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, the specialist clean energy financier established by the Australian government

Sam Mostyn, a leading independent director and sustainability leader and member of the global Business and Sustainable Development Commission.

After providing some opening remarks, our speakers were joined by Bloomberg’s Emily Cadman for a panel discussion and Q&A. They spoke about climate and broader sustainability challenges – including the need to better understand the financial impacts of sustainability-related risks and opportunities; the growing importance of reputational risks and social license; the global relevance of the importance of the Sustainable Development Goals; and the important role business leaders can play by speaking out and supporting better policy responses to these long-term challenges.

Extracts from our speakers prepared remarks are below, along with links to full versions and media coverage. A recording of the panel discussion and Q&A will be available shortly.

CPD would like to thank Sarah Barker, Maged Girgis and the team at MinterEllison for hosting the event, and panellists who contributed to an engaged and candid discussion.

Media coverage

APRA quizzes financial sector over climate change risk preparations, Alice Uribe, Australian Financial Review

APRA stress tests for climate change, Michael Roddan, The Australian

APRA’s Summerhayes says weight of money now driving response to climate change, Peter Hannam, Sydney Morning Herald / The Age

Banks warned of regulatory action as climate change bites global economy, Michael Slezak, The Guardian

Banks and insurers must prepare for climate-related risks: APRA, Penny Timms, ABC Radio (Transcript here)

Key links

The weight of money: A business case for climate risk resilience, Geoff Summerhayes, 29 November 2017

Climate horizons: next steps for scenario analysis in Australia, Sam Hurley and Kate Mackenzie, CPD Discussion Paper, 28 November 2017

Final Recommendations Report, Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, June 2017

Key quotes and speech extracts

Geoff Summerhayes, APRA

“Shifts in market sentiment have increased the risk of asset value volatility, and the potential for stranded assets. Institutions that fail to adequately plan for this transition put their own futures in jeopardy, with subsequent consequences for their account holders, members or policyholders.

…the transition to a low carbon economy is underway, and that means the so-called transition risks are unavoidable: changes to market sentiment, new financial or environmental regulations, or the emergence of new technologies with the potential to prompt a reassessment of the value of a large range of assets, and consequently the value of capital and investments. But that doesn’t mean these risks are unmanageable, or that the impacts on businesses and the wider economy need be negative.”

“APRA supervisors have begun to ask questions of regulated entities. Initially, these have related primarily to awareness: is the entity aware of APRA’s comments about climate-related risks? Has it investigated or planned to investigate the issues raised? And if it has investigated them, is action required?”

“Increasingly, APRA will expect more sophisticated answers, especially from well-resourced and complex entities. As APRA identifies entities with better practices, we will further engage those institutions to gain a deeper understanding of how they approach, measure and manage these risks, and share this as industry guidance.”

“Externally, APRA has commenced discussions with Treasury, as well as fellow regulators ASIC and the RBA, on the sustainability and financial risk dimensions of the economy related to climate change. Through the creation of an interagency initiative, we intend to focus on information-sharing and improving our understanding in this area.”

Christina Tonkin, ANZ

“Our stakeholders are increasingly interested in a broader view – a more-holistic story about how we are creating value over time and the opportunities and challenges impacting our future.”

“We’ve been spending a lot of time reflecting on our purpose as an organisation, and how we can best use our skills, capabilities and relationships to have a positive impact. This inevitably means taking a stand on important issues – even when it comes at a cost… We want to be known as an organisation that shapes a future where people and communities thrive by helping to create a balanced, sustainable economy in which everyone can take part and build a better life.”

S teven Skala AO

“It is the view of our Board is that we must make each dollar go further, to have a much larger impact on decarbonising our economy, to further fill the gaps where it is needed. I can report to you that businesses have watched first movers in their industry cut costs and improve productivity using CEFC finance and are now coming to us to do the same.”

“Our objective is to continue to play a serious role in stimulating the reduction of carbon emissions, by ensuring the benefits of cleaner generation are delivered across the economy, alongside a much stronger focus on reduced energy consumption.”

The post Building a sustainable economy | PAST EVENT | November 2017 appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

November 28, 2017

Climate horizons: next steps for scenario analysis in Australia | DISCUSSION PAPER AND PUBLIC FORUM | November 2017

Today CPD releases a new discussion paper on how business and investors can use scenario analysis in order to better understand and respond to climate-related risks and opportunities.

The paper, Climate horizons: next steps for scenario analysis in Australia, is co-authored by CPD Policy Director Sam Hurley and new CPD Fellow Kate Mackenzie.

It is now very clear that Australian companies and investors should consider and disclose the financial and economic risks that climate change poses. Scenario analysis – which considers how risks and opportunities might evolve under different climate and policy trajectories – is emerging as a crucial part of global best practice for identifying climate risks, disclosing them to markets, and responding to them through strategy and risk management.

The Financial Stability Board’s Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures recommended that scenario analysis should be a key priority for firms and investors around the world, while APRA’s Geoff Summerhayes emphasized the importance of scenario analysis to guide Australian responses to climate risks in his ground-breaking speech on climate change and the financial sector earlier this year.

However, achieving robust, consistent scenario analysis will be challenging, particularly while new practices and standards are emerging. There is a risk that inconsistent or flawed approaches could obscure more than they reveal, and that different users and stakeholders might develop very different expectations about what good scenario analysis looks like.

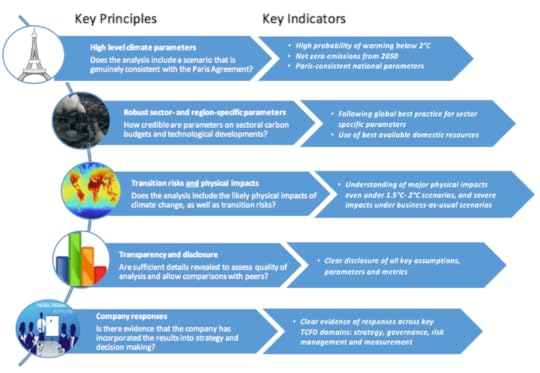

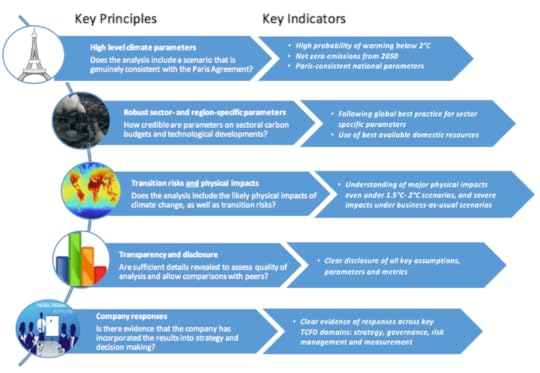

Climate horizons suggests five key principles that stakeholders can focus on as hallmarks of robust scenario analysis, as Australian responses to the TCFD take shape. Scenarios should:

be genuinely consistent with Paris targets – incorporating a high probability of limiting warming to well below 2°C.

include both transition risks and physical impacts from climate change. The latter is likely to be significant even if warming is kept be below 2°C.

engage with the best available resources for understanding the sectoral or regional impacts of climate change.

be transparent about assumptions and parameters used.

show clear evidence not just of analysis of climate risks, but of responses to them through strategy, governance and risk management.

The paper also recommends key priorities for regulators: encouraging wide adoption of the TCFD framework in Australia, boosting their own capabilities to understand scenario analysis and climate risk, and co-operating more effectively to manage and monitor system-wide risks and impacts.

The paper is released to coincide with CPD’s Public Forum on Building a Sustainable Economy, where APRA’s Geoff Summerhayes, the CEFC’s Steven Skala, ANZ’s Christina Tonkin and new CPD board member Sam Mostyn will discuss how different organisations can help shape better near- and long-term responses to climate risk and other sustainability challenges.

CPD will use Climate horizons as a basis for stakeholder engagement and further research on scenario analysis over the next few months, leading towards a full report on this issue in mid-2018.

Key documents

Full discussion paper

Executive summary

Media release

Media coverage

Australia’s top companies ignore climate change, and we let them, Julien Vincent, The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 December 2017

Australian shareholders should be told of climate risks to profits, says think tank, Gareth Hutchens, The Guardian, 29 November 2017

Key links and related reading

CPD roundtable on directors duties, climate risks and sustainability, October 2016

Legal opinion on directors duties and climate change, Noel Hutley SC and Sebastian Hartford-Davis, October 2016

Australia’s new horizon: Climate change challenges and prudential risk, Geoff Summerhayes, February 2017

Carbon risk: a burning issue, Senate Economics References Committee report, April 2017

Final Recommendations Report, Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, June 2017

The wealth of nature: Increasing national wealth and reducing risk by measuring and managing natural capital, Institute of New Economic Thinking, Oxford Martin School and Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford.

The post Climate horizons: next steps for scenario analysis in Australia | DISCUSSION PAPER AND PUBLIC FORUM | November 2017 appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

Climate horizons: next steps for scenario analysis in Australia | DISCUSSION PAPER | November 2017

Today CPD releases a new discussion paper on how business and investors can use scenario analysis in order to better understand and respond to climate-related risks and opportunities.

The paper, Climate horizons: next steps for scenario analysis in Australia, is co-authored by CPD Policy Director Sam Hurley and new CPD Fellow Kate Mackenzie.

It is now very clear that Australian companies and investors should consider and disclose the financial and economic risks that climate change poses. Scenario analysis – which considers how risks and opportunities might evolve under different climate and policy trajectories – is emerging as a crucial part of global best practice for identifying climate risks, disclosing them to markets, and responding to them through strategy and risk management.

The Financial Stability Board’s Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures recommended that scenario analysis should be a key priority for firms and investors around the world, while APRA’s Geoff Summerhayes emphasized the importance of scenario analysis to guide Australian responses to climate risks in his ground-breaking speech on climate change and the financial sector earlier this year.

However, achieving robust, consistent scenario analysis will be challenging, particularly while new practices and standards are emerging. There is a risk that inconsistent or flawed approaches could obscure more than they reveal, and that different users and stakeholders might develop very different expectations about what good scenario analysis looks like.

Climate horizons suggests five key principles that stakeholders can focus on as hallmarks of robust scenario analysis, as Australian responses to the TCFD take shape. Scenarios should:

be genuinely consistent with Paris targets – incorporating a high probability of limiting warming to well below 2°C.

include both transition risks and physical impacts from climate change. The latter is likely to be significant even if warming is kept be below 2°C.

engage with the best available resources for understanding the sectoral or regional impacts of climate change.

be transparent about assumptions and parameters used.

show clear evidence not just of analysis of climate risks, but of responses to them through strategy, governance and risk management.

The paper also recommends key priorities for regulators: encouraging wide adoption of the TCFD framework in Australia, boosting their own capabilities to understand scenario analysis and climate risk, and co-operating more effectively to manage and monitor system-wide risks and impacts.

The paper is released to coincide with CPD’s Public Forum on Building a Sustainable Economy, where APRA’s Geoff Summerhayes, the CEFC’s Steven Skala, ANZ’s Christina Tonkin and new CPD board member Sam Mostyn will discuss how different organisations can help shape better near- and long-term responses to climate risk and other sustainability challenges.

CPD will use Climate horizons as a basis for stakeholder engagement and further research on scenario analysis over the next few months, leading towards a full report on this issue in mid-2018.

Key documents

Full discussion paper

Executive summary

Media release

Media coverage

Australian shareholders should be told of climate risks to profits, says think tank, Gareth Hutchens, The Guardian, 29 November 2017

Key links and related reading

CPD roundtable on directors duties, climate risks and sustainability, October 2016

Legal opinion on directors duties and climate change, Noel Hutley SC and Sebastian Hartford-Davis, October 2016

Australia’s new horizon: Climate change challenges and prudential risk, Geoff Summerhayes, February 2017

Carbon risk: a burning issue, Senate Economics References Committee report, April 2017

Final Recommendations Report, Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, June 2017

The wealth of nature: Increasing national wealth and reducing risk by measuring and managing natural capital, Institute of New Economic Thinking, Oxford Martin School and Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford.

The post Climate horizons: next steps for scenario analysis in Australia | DISCUSSION PAPER | November 2017 appeared first on Centre for Policy Development.

Centre for Policy Development's Blog

- Centre for Policy Development's profile

- 1 follower