Centre for Policy Development's Blog, page 121

May 12, 2011

Jennifer Doggett | A Healthy Start, but it's Complicated

The new budget might seem to be groundbreaking, but what does it really mean for health? Jennifer Doggett cuts through the fat of the 2011 budget.

The new budget might seem to be groundbreaking, but what does it really mean for health? Jennifer Doggett cuts through the fat of the 2011 budget.

In Federal politics, as in MasterChef, a well-presented signature dish can give you the edge over the competition, even when everything else on your Budget night menu is bland and forgettable.

Treasurer Wayne Swan no doubt had this in mind as he dished up a health budget centring on a robust and satisfying mental health initiative comprising a total of $2.2 billion (over five years). This substantial offering is a more comprehensive and better integrated package than the Coalition's alternative policy and will win the Government some popular votes, even though the accompanying initiatives, served up with the mental health package, can best be described as garnishes.

Given the Government's health reform process, already underway, this Budget was never going to make major policy changes. The mental health initiative addresses a gap in the health reform agenda that had been widely criticised by the sector. It covers a wide range of mental health services and programs and provides the opportunity for the states and territories to enter into a National Partnership on Mental Health and work collaboratively on mental health issues.

A positive of this announcement is the establishment of a National Mental Health Commission in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. This gives mental health a high priority and the potential (at least) to take a more coordinated and inter-sectoral approach to mental health issues rather than just treating it as a health system problem. There is also funding for a new national mental health consumer body, which should improve consumer input into the development, implementation and evaluation of mental health policies, programs and services.

Mental health policy is a fraught area of health with the many and varied stakeholder groups continually debating the merits of their various constituencies and ideologies. A major challenge for the Government in the implementation of this initiative will be to balance the interests of the different groups and maintain a strong focus on the needs of consumers, rather than being swayed by the political influence of providers and interest groups.

Another challenge will be to ensure the funding is well-targeted. Mental health is an area in which it is very easy to spend a lot of money without reaching those who need help the most. The key to ensuring the funding delivers maximum value is to focus on programs and services where there is evidence of effectiveness and maintain a commitment to rigorous evaluation of new initiatives.

From a political perspective it's worth asking why mental health received such a substantial funding boost to the virtual exclusion of other areas of health care. Of course there are many reasons why mental health should be funded. Mental illness is a serious health and social issue which directly affects 20% of Australians each year (and many more indirectly). Australia's health system could easily spend this Budget allocation on mental health services and still come back for more.

However, mental health is not the only area of health care crying out for funds. A major gap in the Budget is the continuing failure to address the need for public dental services. Since the Howard government scrapped the Commonwealth Dental Program over a decade ago public dental services have languished, leaving many Australians on low incomes without access to affordable dental care. Responsibility for this cannot totally be laid at the Commonwealth's doorstep. The States and Territories have failed to adequately fund their own dental care programs, preferring instead to argue with the Commonwealth about where responsibility for dental care lies.

The end result of this Mexican standoff is that a generation of Australians are growing up without receiving even basic, preventive dental care. Not the bells-and-whistles orthodontic treatment that guarantees a perfect smile but the type of care which avoids unnecessary loss of teeth. Older Australians remember that it was not uncommon in the era before subsidised dental treatment for people to have lost all of their teeth by middle age. This is the situation we will be returning to unless something is done to provide access to dental services to the 30% of Australians who cannot currently access care.

Poor access to dental care is not just a cosmetic issue but one with profound health and social consequences. Dental problems left untreated can result in serious systemic health issues which require much more intensive (and therefore expensive) treatment. In fact, there are 68 000 avoidable admissions to hospital every year for dental problems which could have been treated in the community (2007-08 figures). This causes unnecessary pain and suffering to thousands of people every year and costs our community millions of dollars. It also causes significant downstream social and economic problems. People with untreated dental diseases often experience difficulties in participating in many aspects of everyday life, such as seeking employment and socialising.

Given these issues, why did the Government choose to provide such a large funding allocation to mental health and almost nothing to public dental care or to any of the other areas of need in the health system, such as indigenous health or rural health? It would have been simple to divide up the $2 billion funding pool for mental health between other priority areas of need to ensure that they all received a share of the funding on offer.

There may be good policy reasons why it's better to allocate a substantial amount of funding to one area, rather than spreading it more thinly throughout the portfolio. A decent funding allocation allows for more comprehensive and integrated reform rather than the development of more band-aid solutions. It also enables the establishment of infrastructure, such as the new National Mental Health Commission, which can play an ongoing leadership role in bringing together the multiple issues and stakeholders that are involved in mental health to effect long term changes in the approach to this complex area of health care.

However, it's hard to ignore the political dimension to Budgetary decisions such as this. The Government can never meet all areas of need in health and therefore it is a political reality that no matter what initiatives are funded, it will always be criticised for not doing more. Given this, the Government needs to decide how to minimise the beat-ups from the various interest groups in the health sector and how to maximise any potential for positive media. Spending a large amount of money in one area gives the Government a good chance of getting a positive response from that sector which will overshadow the negative response from other groups –at least to some extent. Spreading the funding around more equally will result in the Government being criticised from all angles and any positive messages being lost.

The mental health sector has run a vigorous and high profile campaign on mental health – aided by some powerful allies, such as Australian of the Year Patrick McGorry. By working with them behind the scenes to meet a significant number of their demands the Government could guarantee some good publicity on Budget night that would shut out the noise from other sectors disappointed that they missed out. The take-home message from this for health stakeholder groups is to never underestimate the power of a well-planned and executed lobbying campaign by a united (at least temporarily) sector.

Other than the mental health initiative, the Budget will have only a limited impact on the delivery of health care. There are a number of smaller funding allocations for hospitals, rural and remote health services and for indigenous health. All of these, while relatively modest, should go some way towards meeting demand for care in these areas. Additional funding for the new Medicare Local organisations will help support their role in coordinating primary health care at a community level and will ensure the momentum of health reform continues.

Another positive in the Budget is the means testing of the private health insurance rebate. While a preferable outcome would be to scrap the rebate altogether and use the funding to directly subsidise health services, any reduction in expenditure on this inefficient program is a positive. As the means-test takes effect it will be interesting to see whether the dire predictions from the industry about how many people will drop their cover will eventuate.

However, along with the failure to address the crisis in dental care (apart from funding for a voluntary internship year in areas of need), there are a number of major gaps in the Budget that reflect the piecemeal and provider-focussed approach of the Government to health policy. Apart from the bowel cancer screening initiative there is little in the Budget to support the Government's alleged commitment to preventive health. There is also no recognition of the importance of social determinants, such as employment and social status, in influencing health outcomes. No attempt has been made to systematically address the financial difficulties that many Australians face when accessing health care or to promoting greater health equity. Similarly, while public hospitals have received some funding there is no overall attempt to reduce the current high levels of preventable demand for their services. These gaps will all undermine the effectiveness of the Government's health reform agenda to deliver a more efficient and effective health system.

Overall, the Treasurer has delivered a predictable Budget for a Government in the middle of a health reform process in a non-election year. Other than the mental health initiative, the aim of this Budget is to keep the health system ticking over and the reform agenda progressing without making any major outlays. It will be a different story next year when Wayne Swan and his Cabinet colleagues will head back into the kitchen to cook up an election-year Budget to win over the electorate for another three years.

Like what you read? Dive deaper into debates.

Like what you read? Dive deaper into debates.

Sign up for more good ideas. Follow us on Twitter @centrepolicydev & join us on Facebook. Donate to help make good ideas matter.

Jennifer Doggett | Health

[image error] The new bugdet might seem to be groundbreaking, but what does it really mean for health? Jennifer Doggett cuts through the fat of the 2011 bugdet.

In Federal politics, as in MasterChef, a well-presented signature dish can give you the edge over the competition, even when everything else on your Budget night menu is bland and forgettable.

Treasurer Wayne Swan no doubt had this in mind as he dished up a health budget centring on a robust and satisfying mental health initiative comprising a total of $2.2 billion (over five years). This substantial offering is a more comprehensive and better integrated package than the Coalition's alternative policy and will win the Government some popular votes, even though the accompanying initiatives, served up with the mental health package, can best be described as garnishes.

Given the Government's health reform process, already underway, this Budget was never going to make major policy changes. The mental health initiative addresses a gap in the health reform agenda that had been widely criticised by the sector. It covers a wide range of mental health services and programs and provides the opportunity for the states and territories to enter into a National Partnership on Mental Health and work collaboratively on mental health issues.

A positive of this announcement is the establishment of a National Mental Health Commission in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. This gives mental health a high priority and the potential (at least) to take a more coordinated and inter-sectoral approach to mental health issues rather than just treating it as a health system problem. There is also funding for a new national mental health consumer body, which should improve consumer input into the development, implementation and evaluation of mental health policies, programs and services.

Mental health policy is a fraught area of health with the many and varied stakeholder groups continually debating the merits of their various constituencies and ideologies. A major challenge for the Government in the implementation of this initiative will be to balance the interests of the different groups and maintain a strong focus on the needs of consumers, rather than being swayed by the political influence of providers and interest groups.

Another challenge will be to ensure the funding is well-targeted. Mental health is an area in which it is very easy to spend a lot of money without reaching those who need help the most. The key to ensuring the funding delivers maximum value is to focus on programs and services where there is evidence of effectiveness and maintain a commitment to rigorous evaluation of new initiatives.

From a political perspective it's worth asking why mental health received such a substantial funding boost to the virtual exclusion of other areas of health care. Of course there are many reasons why mental health should be funded. Mental illness is a serious health and social issue which directly affects 20% of Australians each year (and many more indirectly). Australia's health system could easily spend this Budget allocation on mental health services and still come back for more.

However, mental health is not the only area of health care crying out for funds. A major gap in the Budget is the continuing failure to address the need for public dental services. Since the Howard government scrapped the Commonwealth Dental Program over a decade ago public dental services have languished, leaving many Australians on low incomes without access to affordable dental care. Responsibility for this cannot totally be laid at the Commonwealth's doorstep. The States and Territories have failed to adequately fund their own dental care programs, preferring instead to argue with the Commonwealth about where responsibility for dental care lies.

The end result of this Mexican standoff is that a generation of Australians are growing up without receiving even basic, preventive dental care. Not the bells-and-whistles orthodontic treatment that guarantees a perfect smile but the type of care which avoids unnecessary loss of teeth. Older Australians remember that it was not uncommon in the era before subsidised dental treatment for people to have lost all of their teeth by middle age. This is the situation we will be returning to unless something is done to provide access to dental services to the 30% of Australians who cannot currently access care.

Poor access to dental care is not just a cosmetic issue but one with profound health and social consequences. Dental problems left untreated can result in serious systemic health issues which require much more intensive (and therefore expensive) treatment. In fact, there are 68 000 avoidable admissions to hospital every year for dental problems which could have been treated in the community (2007-08 figures). This causes unnecessary pain and suffering to thousands of people every year and costs our community millions of dollars. It also causes significant downstream social and economic problems. People with untreated dental diseases often experience difficulties in participating in many aspects of everyday life, such as seeking employment and socialising.

Given these issues, why did the Government choose to provide such a large funding allocation to mental health and almost nothing to public dental care or to any of the other areas of need in the health system, such as indigenous health or rural health? It would have been simple to divide up the $2 billion funding pool for mental health between other priority areas of need to ensure that they all received a share of the funding on offer.

There may be good policy reasons why it's better to allocate a substantial amount of funding to one area, rather than spreading it more thinly throughout the portfolio. A decent funding allocation allows for more comprehensive and integrated reform rather than the development of more band-aid solutions. It also enables the establishment of infrastructure, such as the new National Mental Health Commission, which can play an ongoing leadership role in bringing together the multiple issues and stakeholders that are involved in mental health to effect long term changes in the approach to this complex area of health care.

However, it's hard to ignore the political dimension to Budgetary decisions such as this. The Government can never meet all areas of need in health and therefore it is a political reality that no matter what initiatives are funded, it will always be criticised for not doing more. Given this, the Government needs to decide how to minimise the beat-ups from the various interest groups in the health sector and how to maximise any potential for positive media. Spending a large amount of money in one area gives the Government a good chance of getting a positive response from that sector which will overshadow the negative response from other groups –at least to some extent. Spreading the funding around more equally will result in the Government being criticised from all angles and any positive messages being lost.

The mental health sector has run a vigorous and high profile campaign on mental health – aided by some powerful allies, such as Australian of the Year Patrick McGorry. By working with them behind the scenes to meet a significant number of their demands the Government could guarantee some good publicity on Budget night that would shut out the noise from other sectors disappointed that they missed out. The take-home message from this for health stakeholder groups is to never underestimate the power of a well-planned and executed lobbying campaign by a united (at least temporarily) sector.

Other than the mental health initiative, the Budget will have only a limited impact on the delivery of health care. There are a number of smaller funding allocations for hospitals, rural and remote health services and for indigenous health. All of these, while relatively modest, should go some way towards meeting demand for care in these areas. Additional funding for the new Medicare Local organisations will help support their role in coordinating primary health care at a community level and will ensure the momentum of health reform continues.

Another positive in the Budget is the means testing of the private health insurance rebate. While a preferable outcome would be to scrap the rebate altogether and use the funding to directly subsidise health services, any reduction in expenditure on this inefficient program is a positive. As the means-test takes effect it will be interesting to see whether the dire predictions from the industry about how many people will drop their cover will eventuate.

However, along with the failure to address the crisis in dental care (apart from funding for a voluntary internship year in areas of need), there are a number of major gaps in the Budget that reflect the piecemeal and provider-focussed approach of the Government to health policy. Apart from the bowel cancer screening initiative there is little in the Budget to support the Government's alleged commitment to preventive health. There is also no recognition of the importance of social determinants, such as employment and social status, in influencing health outcomes. No attempt has been made to systematically address the financial difficulties that many Australians face when accessing health care or to promoting greater health equity. Similarly, while public hospitals have received some funding there is no overall attempt to reduce the current high levels of preventable demand for their services. These gaps will all undermine the effectiveness of the Government's health reform agenda to deliver a more efficient and effective health system.

Overall, the Treasurer has delivered a predictable Budget for a Government in the middle of a health reform process in a non-election year. Other than the mental health initiative, the aim of this Budget is to keep the health system ticking over and the reform agenda progressing without making any major outlays. It will be a different story next year when Wayne Swan and his Cabinet colleagues will head back into the kitchen to cook up an election-year Budget to win over the electorate for another three years.

Like what you read? Dive deaper into debates.

Like what you read? Dive deaper into debates.

Sign up for more good ideas. Follow us on Twitter @centrepolicydev & join us on Facebook. Donate to help make good ideas matter.

Fiona Armstrong & Laura Eadie | Innovating For A Prosperous and Secure Future

Does Wayne Swan's budget capitalise on Australia'snatural advantages to rapidly scale up clean energy technologies? Fiona Armstrong & Laura Eadie look at the investments being made to green our economy and the options beyond that.

Does Wayne Swan's budget capitalise on Australia'snatural advantages to rapidly scale up clean energy technologies? Fiona Armstrong & Laura Eadie look at the investments being made to green our economy and the options beyond that.

When it comes to innovation policy, the Gillard government relies heavily on hot air to hide their lightweight commitment to Australia's long-term future. Back in February, the Prime Minister painted a vision for "a high tech, high skill, clean energy economy that is self-sustaining beyond our reliance on mineral exports". Yet the 2011-12 federal budget is light on detail about achieving this.

Given the rapid pace of clean-technology development in Europe and Asia and the pressure of the high dollar on manufacturers, developing a coherent set of policies to stimulate low emissions technology is an essential risk management tool for any government hoping to last beyond the next election, let alone beyond the current mining boom.

If Wayne Swan was serious about balancing Australia's long-run budget, he would have cut more than $1 billion from the Fringe Benefits Tax for cars. He would have claimed back the $2 billion in diesel tax concessions we shell out to mining companies every year and put it to better use funding clean-tech innovation. Who could argue with that as a "no-regrets" way to fund the innovation commitment Ross Garnaut says we need to transition to a low-emissions economy?.

Stuck in a holding pattern

Instead, Gillard's first budget leaves Australia in the same holding pattern as under Rudd and Howard. While the government pretends a carbon price will be enough to drive investment in renewable energy, crucial innovation policies remain an under-funded jumble of grants and rebates which don't align with each other and often place restrictive criteria on applicants, leading to under spending and under performance.

Neither a carbon price nor our only workable emissions reduction policy – the renewable energy target – will meet our manifestly inadequate 2020 target of a 5% reduction, let alone our 2050 target of a 60% reduction.

We urgently need serious policies to scale up alternative base-load renewable energy technologies, such as wave, geothermal and concentrating solar thermal. Yet at a tiny $108.7 million over 14 years, the commitments in the federal budget for venture capital for development and commercialisation of renewable technologies are laughably low. There is little thought to what will drive innovation in clean energy beyond the much mauled Solar Flagships program which has had its energy storage options knocked out, its funding cut, then restored, and now deferred for two years.

Reducing our emissions is not just a moral responsibility – Australia faces a significant risk of being left behind in the development of renewable technology globally. Investment in new renewable energy capacity first exceeded fossil fuels in 2008, and maintained this lead in 2009. In 2010, investment in wind, solar, biofuels and other renewable by G-20 countries surged 30 per cent to almost US$200 billion [PDF]. Despite current high upfront costs, a 2011 report from the Melbourne Energy Institute [PDF] demonstrates substantial cost reductions in base-load renewable energy technologies are possible, assuming specific policies are in place to support their roll out. Countries with a head start in these markets are likely to benefit from their rapid growth rates and generation of skilled jobs.

Building on existing comparative advantages, such as our abundant sunshine, is an important way to secure our place in the global green economy. But establishing new industries requires a coherent set of policies for innovation and commercialisation. We need to level the playing field for renewable energy, to commercialise strategically and start to innovate clean, not dirty.

Level the playing field

Australia's current energy policies tilt the playing field in favour of carbon intensive coal, gas and petroleum fuels. In 2010-11, an estimated $12 billion per year in subsidies and tax concessions went to these fuels. Levelling the playing field for renewable energy is essential to ensuring low-emissions innovation and commercialisation policies are effective.

For example, the diesel rebate applied under the Fuel Tax Credits program currently provides almost $2 billion/year to mining companies as credits to subsidise the use of diesel for off grid electricity generation and use in heavy vehicles. So while most of us pay a levy of 38c per litre for diesel, mining companies get this back as tax credits.

Cutting this subsidy alone would fund Ross Garnaut's recent call for a doubling of investment in clean-technology innovation and commercialisation. Removal of this impost on taxpayers would also encourage mining companies to shift from this very high emissions and costly alternative to clean renewable energy.

Commercialise strategically

To compete in a globalised market for clean technology, Australia needs to develop unique combinations of skills and industries. This requires a strategic approach to investing in technology commercialisation – one that builds on our natural comparative advantages without picking winners or losers.

Remote power generation for mines and communities not connected to the electricity grid is a potential area for such investment. Around ten per cent of Australia's installed power generation is currently off-grid [PDF], and this is set to expand due to the mining boom [PDF].

The current use of diesel for much off grid power generation in remote Australia is absurdly expensive. Existing alternative renewable technologies are already cost competitive in the long run, but suffer from high upfront costs. As an example [PDF], solar thermal with storage costs an estimated $270 per MWhr compared to $350 per MWhr for diesel at some sites. While the applications are not universal, there are substantial opportunities in many remote locations, such as the Midwest minerals province in WA.

Policies to achieve this might include grants for site specific feasibility studies and loan guarantees. By providing information and reducing risk, government can help address the difficulty faced in financing projects using new technologies, and increase investor confidence and the willingness of banks to lend.

Innovate clean, not dirty

Building competitive industries also requires investment at the beginning of the innovation chain. There are strong arguments for weighting government expenditure at the early stages of the research and development continuum toward renewable energy technologies, rather than betting on clean coal or carbon capture and storage.

As fuel costs and carbon prices inevitably rise, existing industries will fund innovation in fossil fuels to improve their efficiency, and potentially reduce their carbon emissions. Clearly, there are fewer vested interests willing to significantly invest in new renewable energy technologies.

As Garnaut says, public support for research, development and commercialisation of low-emissions technologies is one way of cutting the cost of reducing our emissions. At another level, it is our contribution to a global effort.

In light of the current political instability around our domestic carbon policy, Australia needs a better strategy to adapt to the rapidly changing global economy. We can do this by developing an innovation policy that builds on our comparative advantages, using the wealth generated by our natural resources to build new industries and provide for our own clean energy future.

Otherwise Australia risks remaining stuck in a holding pattern – while other countries ride the wave of clean-tech investment into the global green economy.

Fiona Armstrong is a Fellow at the Centre for Policy Development. Laura Eadie is the CPD's Sustainable Economy Program Director.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Sign up for more good ideas. Follow us on Twitter @centrepolicydev & join us on Facebook. Donate to help make good ideas matter.

Fiona Armstrong & Laura Eadie | Innovating for a prosperous and secure future

When it comes to innovation policy, the Gillard government relies heavily on hot air to hide their lightweight commitment to Australia's long-term future. Back in February, the Prime Minister painted a vision for "a high tech, high skill, clean energy economy that is self-sustaining beyond our reliance on mineral exports". Yet the 2011-12 federal budget is light on detail about achieving this.

When it comes to innovation policy, the Gillard government relies heavily on hot air to hide their lightweight commitment to Australia's long-term future. Back in February, the Prime Minister painted a vision for "a high tech, high skill, clean energy economy that is self-sustaining beyond our reliance on mineral exports". Yet the 2011-12 federal budget is light on detail about achieving this.

Given the rapid pace of clean-technology development in Europe and Asia and the pressure of the high dollar on manufacturers, developing a coherent set of policies to stimulate low emissions technology is an essential risk management tool for any government hoping to last beyond the next election, let alone beyond the current mining boom.

If Wayne Swan was serious about balancing Australia's long-run budget, he would have cut more than $1 billion from the Fringe Benefits Tax for cars. He would have claimed back the $2 billion in diesel tax concessions we shell out to mining companies every year and put it to better use funding clean-tech innovation. Who could argue with that as a "no-regrets" way to fund the innovation commitment Ross Garnaut says we need to transition to a low-emissions economy?.

Stuck in a holding pattern

Instead, Gillard's first budget leaves Australia in the same holding pattern as under Rudd and Howard. While the government pretends a carbon price will be enough to drive investment in renewable energy, crucial innovation policies remain an under-funded jumble of grants and rebates which don't align with each other and often place restrictive criteria on applicants, leading to under spending and under performance.

Neither a carbon price nor our only workable emissions reduction policy – the renewable energy target – will meet our manifestly inadequate 2020 target of a 5% reduction, let alone our 2050 target of a 60% reduction.

We urgently need serious policies to scale up alternative base-load renewable energy technologies, such as wave, geothermal and concentrating solar thermal. Yet at a tiny $108.7 million over 14 years, the commitments in the federal budget for venture capital for development and commercialisation of renewable technologies are laughably low. There is little thought to what will drive innovation in clean energy beyond the much mauled Solar Flagships program which has had its energy storage options knocked out, its funding cut, then restored, and now deferred for two years.

Reducing our emissions is not just a moral responsibility – Australia faces a significant risk of being left behind in the development of renewable technology globally. Investment in new renewable energy capacity first exceeded fossil fuels in 2008, and maintained this lead in 2009. In 2010, investment in wind, solar, biofuels and other renewable by G-20 countries surged 30 per cent to almost US$200 billion [PDF]. Despite current high upfront costs, a 2011 report from the Melbourne Energy Institute [PDF] demonstrates substantial cost reductions in base-load renewable energy technologies are possible, assuming specific policies are in place to support their roll out. Countries with a head start in these markets are likely to benefit from their rapid growth rates and generation of skilled jobs.

Building on existing comparative advantages, such as our abundant sunshine, is an important way to secure our place in the global green economy. But establishing new industries requires a coherent set of policies for innovation and commercialisation. We need to level the playing field for renewable energy, to commercialise strategically and start to innovate clean, not dirty.

Level the playing field

Australia's current energy policies tilt the playing field in favour of carbon intensive coal, gas and petroleum fuels. In 2010-11, an estimated $12 billion per year in subsidies and tax concessions went to these fuels. Levelling the playing field for renewable energy is essential to ensuring low-emissions innovation and commercialisation policies are effective.

For example, the diesel rebate applied under the Fuel Tax Credits program currently provides almost $2 billion/year to mining companies as credits to subsidise the use of diesel for off grid electricity generation and use in heavy vehicles. So while most of us pay a levy of 38c per litre for diesel, mining companies get this back as tax credits.

Cutting this subsidy alone would fund Ross Garnaut's recent call for a doubling of investment in clean-technology innovation and commercialisation. Removal of this impost on taxpayers would also encourage mining companies to shift from this very high emissions and costly alternative to clean renewable energy.

Commercialise strategically

To compete in a globalised market for clean technology, Australia needs to develop unique combinations of skills and industries. This requires a strategic approach to investing in technology commercialisation – one that builds on our natural comparative advantages without picking winners or losers.

Remote power generation for mines and communities not connected to the electricity grid is a potential area for such investment. Around ten per cent of Australia's installed power generation is currently off-grid [PDF], and this is set to expand due to the mining boom [PDF].

The current use of diesel for much off grid power generation in remote Australia is absurdly expensive. Existing alternative renewable technologies are already cost competitive in the long run, but suffer from high upfront costs. As an example [PDF], solar thermal with storage costs an estimated $270 per MWhr compared to $350 per MWhr for diesel at some sites. While the applications are not universal, there are substantial opportunities in many remote locations, such as the Midwest minerals province in WA.

Policies to achieve this might include grants for site specific feasibility studies and loan guarantees. By providing information and reducing risk, government can help address the difficulty faced in financing projects using new technologies, and increase investor confidence and the willingness of banks to lend.

Innovate clean, not dirty

Building competitive industries also requires investment at the beginning of the innovation chain. There are strong arguments for weighting government expenditure at the early stages of the research and development continuum toward renewable energy technologies, rather than betting on clean coal or carbon capture and storage.

As fuel costs and carbon prices inevitably rise, existing industries will fund innovation in fossil fuels to improve their efficiency, and potentially reduce their carbon emissions. Clearly, there are fewer vested interests willing to significantly invest in new renewable energy technologies.

As Garnaut says, public support for research, development and commercialisation of low-emissions technologies is one way of cutting the cost of reducing our emissions. At another level, it is our contribution to a global effort.

In light of the current political instability around our domestic carbon policy, Australia needs a better strategy to adapt to the rapidly changing global economy. We can do this by developing an innovation policy that builds on our comparative advantages, using the wealth generated by our natural resources to build new industries and provide for our own clean energy future.

Otherwise Australia risks remaining stuck in a holding pattern – while other countries ride the wave of clean-tech investment into the global green economy.

Fiona Armstrong is a Fellow at the Centre for Policy Development. Laura Eadie is the CPD's Sustainable Economy Program Director.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Sign up for more good ideas. Follow us on Twitter @centrepolicydev & join us on Facebook. Donate to help make good ideas matter.

James Whelan & Jennifer Doggett | Bean Counting is Compromising our Public Services

Can arbitrary cuts under the guise of efficiency deliver a better public service? James Whelan & Jennifer Doggett take a look at the political and policy failure that is the Efficiency Dividend.What will these continued cuts mean?

Can arbitrary cuts under the guise of efficiency deliver a better public service? James Whelan & Jennifer Doggett take a look at the political and policy failure that is the Efficiency Dividend.What will these continued cuts mean?

The Efficiency Dividend (ED) requires public sector agencies to calculate a potential saving every year by multiplying their departmental expenses from the previous budget by the efficiency dividend then indexing for inflation. The 1.25% efficiency dividend was originally introduced by the Hawke government in 1986 as a temporary measure. The Rudd administration temporarily increased this to 2 per cent in a 'hole in the wall' budgetary manoeuvre.

Politically, the Efficiency Dividend has a superficial attraction to governments as it allows them to cut public sector budgets under the guise of 'increasing efficiency'. This is a more attractive option than directly cutting services but its political effectiveness has a limited lifespan.

The problem with this strategy is that it relies on a continual supply of 'low hanging fruit' which public sector agencies can offer up as savings without reducing their output. In reality this does not occur. Over time savings become increasingly difficult to find until organisations need to reduce essential functions in order to meet savings targets.

This is the point at which continued imposition of the Efficiency Dividend is counter-productive. Twenty-six years on, the public service is under increasing pressure to effectively fulfil its functions. Increasing the ED will result in public sector agencies devoting scare resources to juggling budgets instead of delivering the high quality services the Australian public want and deserve.

Public sector agencies are now reporting that they are being forced to cut back functions in order to deliver continued savings.

This became clear during recent Senate Estimates hearings where Senator Humphries and his Liberal colleague Russell Trood pursued the impacts of the Efficiency Dividend during sustained interrogation of senior staff representing key APS agencies. The Senators' inquiries revealed the impact of the ED on cultural agencies with the National Gallery planning to freeze travelling exhibitions and the National Library winding back newspaper digitisation and scrapping their online reference service.

Public service funding and efficiency: Myth busting

Myth 1: The Australian public service is inefficient.

Reality: There is good evidence that overall the APS is very efficient. A 2009 KPMG study of government administration classed Australia's bureaucracy as 'highly efficient' and found that the main impediment to a more efficient government sector was a high regulatory burden.

Myth 2: Across-the-board funding cuts increase efficiency.

Reality: Untargeted funding cuts in an already efficient system will result in either outputs being reduced or quality compromised. This will impact upon the Australian community which relies on the public sector to provide many essential services.

Myth 3: Public sector agencies are responsible for any inefficiencies in their operations.

Reality: Public sector organisations often have to respond to external pressures which create inefficiencies that they cannot control. CPD research found that public servants identified Ministers and their offices as a significant source of inefficiency within their agencies. The blunt instrument of the efficiency dividend, however, is not wielded here.

Myth 4: Efficiency across public and private sector organisations can be compared by measuring budgets and outputs.

Reality: Public sector agencies often perform functions that their private sector counterparts cannot undertake, often because it is not profitable for them to do so. Macquarie builds urban toll roads and takes over capital city airports, but governments fund the country roads and local governments provide essential country airports.

Myth 5: The general public won't notice additional public sector funding cuts.

Reality: While initially there may have been scope within the public service to cut budgets without having a direct impact on the general public, the ongoing arbitrary imposition of the efficiency dividend has left public sector agencies with no room for making further cuts without reducing their functions. This will directly impact upon the community, in particular some of the most disadvantaged who rely on public sector services.

Myth 6: There are no alternatives to the Efficiency Dividend

Reality: There are a number of alternative strategies for supporting a high quality public sector which should be considered in preference to an increase in the ED. These include targeted measures, supported by systematic reviews of agency efficiency, which identify and address any areas of inefficiency within each agency (rather than setting an aggregate target across the APS). Another alternative would be to allow agencies themselves to identify potential savings and strategies to achieve these, over a longer period than 12 months to avoid incentives for short-term gaming. Both of these options allow for the real possibility that some agencies are already operating at maximum efficiency and do not currently have any scope for further savings. See CPD research for more.

The increase in the Efficiency Dividend announced in the Budget will place further pressure on the public sector and result in more agencies reducing their services to the general public. This risks creating an ongoing political headache for the Labor Government as every perceived failure in public sector performance can now be attributed to the Efficiency Dividend.

Like comedy, political strategy is all about the timing. The Howard Government could get away with the Efficiency Dividend because at that point there was some scope to find savings within departments without compromising output. That time has now passed and the politically smart move would be to quietly retire the ED and find other more effective ways of supporting a high performing public sector.

This is reflected in the findings of a number of reviews which have found that the ED is a blunt instrument that does not achieve its stated aim of increasing efficiency across the public service.

For example, the 2010 Moran Review, heralded as the most comprehensive review of the Australian Public Service in 35 years, raised issues about the effectiveness of this approach and recommended a review of the Efficiency Dividend. This review, coordinated by the Department of Finance and Deregulation, concluded that the efficiency dividend is an ineffective instrument to increase productivity and that agency outlays and workloads have increased during the last decade. Significantly, the review concluded that there is "no accepted or reliable way of measuring the relative efficiency of the public sector". How then can the Treasurer require agencies to demonstrate an annual 1.5% improvement in efficiency? Simply providing less funding while demanding the same or increased service delivery is a poor substitute for meaningful performance improvement.

Furthermore, the underlying motivation for continuing to impose the Efficiency Dividend – the desperate pursuit of a Budget surplus – is itself questionable. Ministers Wong and Swan primarily argue that public service cuts are an essential element of returning Australia to a budget surplus by 2012-13. This determination has been described by Reserve Bank board member and ANU economist Professor Warwick McKibben as a 'fetish' and is not based on a realistic assessment of Australia's economic strengths and weaknesses.

While Australia races back from a current deficit of just 3% of GDP, the United Kingdom and United States have deficits of 10% and 11% of GDP respectively and Treasury expects the world's major advanced economies to be in deficit by an average of 6% of GDP in 2015. We're hardly the economic basket case that the Gillard Cabinet and Opposition Leader assert.

Regardless of our budgetary situation, it does not make any sense to pursue strategies that compromise the performance of our public service agencies. Effective investment in the public sector is good for the economy – a truism acknowledged by Victorian Premier Ted Ballieu who recently observed that, "When the state grows, employment grows". In addition to its economic contribution, our public sector plays a vital role in improving the lives of individuals now and in building a more cohesive and sustainable future for our country.

The Government's decision to increase the ED in the Federal Budget will deliver short-term savings but result in long-term costs for Australians.

Dr James Whelan is the Public Service Program Research Director at the CPD. Jennifer Doggett is a Fellow at The Centre for Policy Development

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Sign up for more good ideas. Follow us on Twitter @centrepolicydev & join us on Facebook. Donate to help make good ideas matter.

James Whelan & Jennifer Doggett | Bean counting is compromising our public services

The Efficiency Dividend (ED) requires public sector agencies to calculate a potential saving every year by multiplying their departmental expenses from the previous budget by the efficiency dividend then indexing for inflation. The 1.25% efficiency dividend was originally introduced by the Hawke government in 1986 as a temporary measure. The Rudd administration temporarily increased this to 2 per cent in a 'hole in the wall' budgetary manoeuvre.

The Efficiency Dividend (ED) requires public sector agencies to calculate a potential saving every year by multiplying their departmental expenses from the previous budget by the efficiency dividend then indexing for inflation. The 1.25% efficiency dividend was originally introduced by the Hawke government in 1986 as a temporary measure. The Rudd administration temporarily increased this to 2 per cent in a 'hole in the wall' budgetary manoeuvre.

Politically, the Efficiency Dividend has a superficial attraction to governments as it allows them to cut public sector budgets under the guise of 'increasing efficiency'. This is a more attractive option than directly cutting services but its political effectiveness has a limited lifespan.

The problem with this strategy is that it relies on a continual supply of 'low hanging fruit' which public sector agencies can offer up as savings without reducing their output. In reality this does not occur. Over time savings become increasingly difficult to find until organisations need to reduce essential functions in order to meet savings targets.

This is the point at which continued imposition of the Efficiency Dividend is counter-productive. Twenty-six years on, the public service is under increasing pressure to effectively fulfil its functions. Increasing the ED will result in public sector agencies devoting scare resources to juggling budgets instead of delivering the high quality services the Australian public want and deserve.

Public sector agencies are now reporting that they are being forced to cut back functions in order to deliver continued savings.

This became clear during recent Senate Estimates hearings where Senator Humphries and his Liberal colleague Russell Trood pursued the impacts of the Efficiency Dividend during sustained interrogation of senior staff representing key APS agencies. The Senators' inquiries revealed the impact of the ED on cultural agencies with the National Gallery planning to freeze travelling exhibitions and the National Library winding back newspaper digitisation and scrapping their online reference service.

Public service funding and efficiency: Myth busting

Myth 1: The Australian public service is inefficient.

Reality: There is good evidence that overall the APS is very efficient. A 2009 KPMG study of government administration classed Australia's bureaucracy as 'highly efficient' and found that the main impediment to a more efficient government sector was a high regulatory burden.

Myth 2: Across-the-board funding cuts increase efficiency.

Reality: Untargeted funding cuts in an already efficient system will result in either outputs being reduced or quality compromised. This will impact upon the Australian community which relies on the public sector to provide many essential services.

Myth 3: Public sector agencies are responsible for any inefficiencies in their operations.

Reality: Public sector organisations often have to respond to external pressures which create inefficiencies that they cannot control. CPD research found that public servants identified Ministers and their offices as a significant source of inefficiency within their agencies. The blunt instrument of the efficiency dividend, however, is not wielded here.

Myth 4: Efficiency across public and private sector organisations can be compared by measuring budgets and outputs.

Reality: Public sector agencies often perform functions that their private sector counterparts cannot undertake, often because it is not profitable for them to do so. Macquarie builds urban toll roads and takes over capital city airports, but governments fund the country roads and local governments provide essential country airports.

Myth 5: The general public won't notice additional public sector funding cuts.

Reality: While initially there may have been scope within the public service to cut budgets without having a direct impact on the general public, the ongoing arbitrary imposition of the efficiency dividend has left public sector agencies with no room for making further cuts without reducing their functions. This will directly impact upon the community, in particular some of the most disadvantaged who rely on public sector services.

Myth 6: There are no alternatives to the Efficiency Dividend

Reality: There are a number of alternative strategies for supporting a high quality public sector which should be considered in preference to an increase in the ED. These include targeted measures, supported by systematic reviews of agency efficiency, which identify and address any areas of inefficiency within each agency (rather than setting an aggregate target across the APS). Another alternative would be to allow agencies themselves to identify potential savings and strategies to achieve these, over a longer period than 12 months to avoid incentives for short-term gaming. Both of these options allow for the real possibility that some agencies are already operating at maximum efficiency and do not currently have any scope for further savings. See CPD research for more.

The increase in the Efficiency Dividend announced in the Budget will place further pressure on the public sector and result in more agencies reducing their services to the general public. This risks creating an ongoing political headache for the Labor Government as every perceived failure in public sector performance can now be attributed to the Efficiency Dividend.

Like comedy, political strategy is all about the timing. The Howard Government could get away with the Efficiency Dividend because at that point there was some scope to find savings within departments without compromising output. That time has now passed and the politically smart move would be to quietly retire the ED and find other more effective ways of supporting a high performing public sector.

This is reflected in the findings of a number of reviews which have found that the ED is a blunt instrument that does not achieve its stated aim of increasing efficiency across the public service.

For example, the 2010 Moran Review, heralded as the most comprehensive review of the Australian Public Service in 35 years, raised issues about the effectiveness of this approach and recommended a review of the Efficiency Dividend. This review, coordinated by the Department of Finance and Deregulation, concluded that the efficiency dividend is an ineffective instrument to increase productivity and that agency outlays and workloads have increased during the last decade. Significantly, the review concluded that there is "no accepted or reliable way of measuring the relative efficiency of the public sector". How then can the Treasurer require agencies to demonstrate an annual 1.5% improvement in efficiency? Simply providing less funding while demanding the same or increased service delivery is a poor substitute for meaningful performance improvement.

Furthermore, the underlying motivation for continuing to impose the Efficiency Dividend – the desperate pursuit of a Budget surplus – is itself questionable. Ministers Wong and Swan primarily argue that public service cuts are an essential element of returning Australia to a budget surplus by 2012-13. This determination has been described by Reserve Bank board member and ANU economist Professor Warwick McKibben as a 'fetish' and is not based on a realistic assessment of Australia's economic strengths and weaknesses.

While Australia races back from a current deficit of just 3% of GDP, the United Kingdom and United States have deficits of 10% and 11% of GDP respectively and Treasury expects the world's major advanced economies to be in deficit by an average of 6% of GDP in 2015. We're hardly the economic basket case that the Gillard Cabinet and Opposition Leader assert.

Regardless of our budgetary situation, it does not make any sense to pursue strategies that compromise the performance of our public service agencies. Effective investment in the public sector is good for the economy – a truism acknowledged by Victorian Premier Ted Ballieu who recently observed that, "When the state grows, employment grows". In addition to its economic contribution, our public sector plays a vital role in improving the lives of individuals now and in building a more cohesive and sustainable future for our country.

The Government's decision to increase the ED in the Federal Budget will deliver short-term savings but result in long-term costs for Australians.

Dr James Whelan is the Public Service Program Research Director at the CPD. Jennifer Doggett is a Fellow at The Centre for Policy Development

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Sign up for more good ideas. Follow us on Twitter @centrepolicydev & join us on Facebook. Donate to help make good ideas matter.

May 11, 2011

Ian McAuley | A Mostly Harmless Budget

After all those warnings about a tough budget, Wayne Swan presented a document that breaks a little with economic policy of recent years but not enough to ring alarm bells, writes Ian McAuley.

Read Ian's article on how the Treasurer's attempt to trim back middle class welfare are constrained by a monomaniacal obsession with public debt, low taxes, and the welfare state. Originally published in New Matilda, here.

Conservatism is an easy path for we are more apt to criticise a government for what it does rather than for what it fails to do — that's why conservative parties get such an easy run in the media, and it's why, since its near-death experience in last year's election, conservatism has been a mark of the present government.

Yet the Treasurer did give some hints of a return to traditional Labor principles in Tuesday's budget. In making some cuts to "middle class welfare", it is mildly redistributive, and it takes a few steps toward economic reform in terms of getting more people into the workforce. It breaks a little from economic policy of recent years.

One of the developments of the last 30 years, as the Australian economy has opened up to competition, has been for disparities between rich and poor to widen. The dominant policy approach, seldom articulated, has been to use government transfer payments (social security) and tax concessions to overcome some of these disparities, and to keep the middle class committed to economic reform. Contrary to popular views, governments of neoliberal persuasion have tended to be more committed to welfare payments than left-leaning governments, not because they are more compassionate, but rather because they have to maintain some minimal degree of social cohesion. That is why around 15 per cent of household income is now in the form of welfare payments from government, and a third of the population receives some form of Centrelink payment. In times past, social security was much more directed, because those who had work had relatively well-paid work.

The tradition of the Labor Party and of similar parties in other democracies has been to strive for an ideal in which everyone who is capable of work is able to do so, and can attract a reasonable income without the need for welfare assistance.

Redistribution is achieved through progressive taxation and through universal provision of public services, particularly health care and education. Historically in Australia these ends were served with measures such as tariff protection and highly regulated labour markets. As these measures have reached their use-by dates, it makes sense for our Labor party to follow the lead of Labour and Social Democrat parties in mainland Europe in making the turn to developing and sustaining human capital.

In line with this tradition we see in this budget some winding back of middle class welfare. Eligibility for family benefits is to be tightened, mainly through a means test ceiling which is to be frozen in nominal terms. The absurd tax concessions for company cars are to be scaled back. Diverting income to children through family trusts is to become less attractive. And the Government will once again present to the Senate its proposal to apply a means test to the private health insurance rebate. On the human capital side there is progress, particularly in upgrading skills and in increasing workforce participation — although there is much more that can be done.

These modest cuts in middle class welfare are changes which all but those with a superhuman capacity for rationalising unearned privilege would support. Shadow Treasurer Hockey, obviously with a brief to criticise the Government for becoming dangerously redistributive, has been struggling to defend family tax benefits for households with $150,000 incomes.

But there remain untouched some very large and inequitable benefits for the well off. Generous tax provisions for superannuation contributions remain, and they are particularly attractive to some well off people, such as those who can live off an inheritance while using salary sacrificing to reduce their effective tax rate to 15 per cent. When superannuation funds become pension funds, on retirement, they are entirely tax-free. There remains a capital gains tax system which, with its 50 per cent discount, rewards short-term financial speculation, while, because of its lack of indexation, it penalises long-term productive investment. "Negative gearing" for property investment remains, with its allowance for double-counting depreciation and interest payments as tax deductions. These and other concessions do not show up in budgetary papers as welfare. Some show up as "tax expenditures", while others do not show up at all in budget documents.

When governments are gripped by political caution, however, governments will do no more than make marginal adjustments. In framing this budget the Government seems to have worked within three constraints, the first two of which are self-imposed.

The first constraint is an obsession with bringing the cash balance back to balance by 2012-13. It's an imperative without any economic basis, particularly in a country without significant debt. Public debt is expected to peak next year at 7.2 per cent of GDP and should be eliminated entirely in a few years.

At first sight that seems to be sensible counter-cyclical management; governments should retreat when the economy is in a strong growth phase. But it has become a monomaniacal obsession, fuelled by the hysteria of Opposition politicians and talk-back radio hosts, who give the impression that our public debt situation is about to send us into ruin, and who perpetrate stories about our public debt being the largest in history.

The truth is that our public debt peaked at 120 per cent of GDP just after the Pacific War, and the years in which we paid it off were ones of strong growth and prosperity. And by international comparison our public debt is minuscule: in the USA, for example, it's 60 per cent of GDP and growing.

What counts is not the level of public debt, but rather the use to which it is put. When a government tries to use debt as a means to finance consumption (other than as a temporary Keynesian stimulus), or, as in the case of Greece, as a substitute for collecting taxes, that is indeed irresponsible. As a contrast it is instructive to consider Germany, which is bearing public debt at around 50 per cent of GDP. But no one is criticising Germany for profligacy, for that debt is balanced by excellent public infrastructure.

In Australia's case our debt obsession has meant that we have avoided investing in productive assets, particularly surface transport and environmental restoration. We are too concerned with fiscal deficits and too unconcerned with our infrastructure deficits, as if our national balance sheet has only one side, the debt side. In this regard we are fortunate that the National Broadband Network can be funded as a specific capital item, but, for reasons to do with accounting conventions and ownership in a federation, we do not keep adequate accounts of public capital.

The second constraint is to "keep taxation as a share of GDP, on average, below the level for 2007-08 (23.5 per cent)". Why 23.5 per cent? It's not explained. Actually Australia is one of the lowest-taxed countries out of the 32 countries in the OECD; only Mexico, Turkey and the USA have lower rates, and even the USA doesn't provide a reasonable comparison, for American companies bear many imposts, such as private health insurance, which are covered by taxes in other countries, and with its debt projected to reach 100 per cent of GDP it will have to raise taxes before long.

The third constraint is the ongoing demand for social security and welfare payments, which take about 40 per cent of the budget, leaving any economies to be achieved in the other 60 per cent of the budget. Even within this 60 per cent almost a third is accounted for by health care, which inevitably keeps growing with an ageing population. (Shifting health financing off-budget is not an economically responsible option, as American experience shows.) Therefore savings, if they are to be found, are focussed on that remaining 40 per cent of the budget which covers services such as transport, education, defence and a range of other services. That's why this budget has so many nitpicking cuts and deferrals in program expenditures, and why investments in human capital, while welcome, are still modest.

So, with those constraints, the 2011-12 budget hardly comes as a surprise. If the Government could get over its debt constraint it could be much more relaxed about funding recovery from natural disasters, and would not be forever deferring investment in infrastructure. On the revenue side it could raise taxation revenue significantly by addressing some of the most generous tax concessions, particularly those relating to unearned income, all without raising tax rates.

It has been a budget on the right track, but it hasn't gone very far down that track. The Government seems to have been held back by its own failure to articulate its principles — how these relate to its own partisan traditions and how they differ from alternatives on offer.

May 10, 2011

Ben Eltham | A Strong Budget But Will It Bounce?

Ben Eltham congratulates Swan and Gillard for a sound budget but argues that it will not give them the boost they need in the polls. In the long-run however, it may reep subtle returns in terms of perceptions of the government's credibility.

Ben Eltham's article first published in New Matilda, here.

Wayne Swan's fourth and Julia Gillard's first budget is impressive — except in terms of politics. If we look at it in terms of the big picture balance sheet, or policy, or economically, it's a success.

Fiscally the budget will record a modest deficit of around $22 billion in cash terms, or about 1.5 per cent of GDP. To achieve this, Labor has made many small cuts in a number of programs, and a number of larger ones, including in renewable energy spending, in the defence department, and in family tax benefits. There is also an increase in the efficiency dividend of $1.5 billion, which puts the squeeze on the bureaucracy, particularly smaller departments. All up the government will spend about $362 billion in return for approximately $342 billion in tax receipts, including Future Fund earnings.

Much of the commentary last night and this morning has focused, as I predicted, on whether Swan's budget was "tough" enough. This is nonsense. Across a budget this big, a deficit of $20-odd billion is a manageable deficit. With the solid growth forecast by Treasury, there is little doubt that Swan will achieve Labor's cherished goal of a small surplus in 2012-13.

There was a lot of rhetoric in the lead up to the budget about middle class welfare, but Swan and Penny Wong have achieved some significant savings by paring back upper-class welfare. A tax offset for dependent spouses staying at home without children has been abolished, for instance. This was a notorious tax loophole that allowed high-income earners to claw back tax refunds simply because their spouses weren't in the workforce. Another tax lurk which mainly benefited the rich was the ability of rich parents to gift some of their investment earnings to their children; this has been closed off, saving $740 million. The Family Tax Benefit thresholds have also been frozen at $150,000, and the indexation of the FTB supplement has been halted, saving approximately $2 billion in total merely by the workings of that old friend of the finance minister, bracket creep.

However, some cuts will hurt more.

Given the dire state of Australian housing affordability, the decision to save $345 million by slowing down the rollout of the National Rental Affordability Scheme is a particularly cruel one. $211 million has been saved in aged care spending through providing more care to the elderly in their homes — ignoring the fact that there is still a huge need for investment in aged care infrastructure. And some of the mental health initiatives have actually been paid for by winding back Medicare payments for mental health consultations, a strategy that looks contradictory.

But in the main, this is a responsible budget in terms of its taxing and spending, as no less an authority than Ross Gittins has stated.

In policy terms, this is a classic Labor budget. If we look at the policy priorities, they are the sorts of things that Chifley or Hawke would have welcomed, as Greg Jericho has also pointed out. The big ticket items are in mental health, in vocational education and training, in regional infrastructure, and in workforce participation initiatives such as employer subsidies to give the long-term unemployed a job. Foreign aid has also won increases, for instance in AusAID grants to NGOs and volunteers.

The participation initiatives are particularly important and they must be viewed in the context of the broader economy.

In Budget Paper 1, Treasury has some important and fascinating things to say about Australia's "mining boom mark 2″ and the rapidly transforming composition of our economy. Yes, the mining boom is important, Treasury writes. Even given this, "the current transition that Australia faces is much broader than the mining boom."

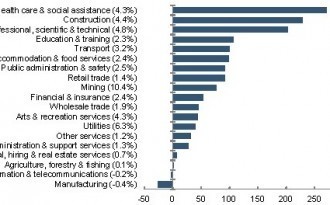

You can see the transformation in the graph below.

Australia's workforce is changing fast, as we lose manufacturing jobs but gain employment in industries such as healthcare, mining, construction and the professions. As Treasury observes, "two-thirds of the 1.5 million [jobs] added to total employment over 2003-4 to 2009-10 are highly skilled."

For those interested in these things, Treasury has also included a fascinating footnote on the economic history of resource booms. It examines the famous example of the rapid inflation and manufacturing decline supposedly suffered by the Netherlands (the so-called "Dutch disease") after the discovery of oil in the North Sea, and argues that the effect was much less severe than first thought. In contrast to those, such as myself, who think the negative impacts of the mining boom will be significant, Treasury is optimistic, even about the manufacturing sector. "International evidence suggests that these concerns around Dutch disease tend not to apply to advanced countries," Treasury concludes. Wayne Swan will certainly be hoping they're right.

Which brings us to the politics.

This was always going to be the sternest test for the government, particularly given the press gallery's continuing economic illiteracy (exemplified in this woefully ignorant pre-budget article by Fairfax's Peter Hartcher). Much of the commentary has of course focused on the deficit and whether Labor can indeed get back to surplus. There has also been a lot of ink spilled on the budget cuts, particularly to so-called middle-class welfare, and whether there were enough of them.

There seems little likelihood that Labor will get a "bounce" from this budget. But the longer-term effects may be subtly positive. With the 2011 budget, Wayne Swan has delivered a responsible, credible, progressive financial blueprint for the next three years of Julia Gillard's minority government. This can only help with the intangibles, such as backbench morale and the general perception of the government's credibility.

The Opposition's performance in response has also been woeful: Joe Hockey in several interviews last night was at his blustering and arrogant worst. The Opposition's one-dimensional tactics of single-minded opposition have certainly been effective so far, but they have been helped by a drifting and clueless government. This budget gives Labor something to rally around, and a coherent message to help carry forward the debate on the carbon tax. If Swan does indeed bring in a surplus next year, bedded down in a consolidated budget with the carbon tax, the Opposition's empty policy cupboard will be that much more apparent.

It's too early to see if the budget will staunch Labor's haemorrhaging in the polls, but here at least is some precious clean air for the government.

Ben Eltham | Money Where It's Needed In Mental Health

Ben Eltham writes it's been a long time coming but finally, some real funding has been found for mental health.

Read Ben Elthams article, originally published at New Matilda, here.

It's taken an awfully long time and some very determined lobbying, but this budget has finally delivered some real support for Australia's woefully under-funded mental health sector.

The reasons why mental health became the poor cousin of Australia's healthcare system are long and complex. They include a long-standing community stigma about mental health, inadequate training in mental health issues for medical students and doctors who aren't specialists in the field, an overall health policy mix overwhelmingly weighted towards acute care and away from chronic and primary care, and the sheer difficulty of addressing complex mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety and schizophrenia.

What we do know is that mental healthcare has been in crisis in this country for years. Talk to any doctor in an emergency department of a pubic hospital and they will tell just how much of their time is taken up dealing with acute psychiatric patients, many of whom present to our health system for the first time when they are admitted to an emergency department after a suicide attempt.

Even for those who do receive treatment, there is often no follow-up. According to John Mendoza, a Professor at the University of the Sunshine Coast and — until he resigned in frustration — the federal government's top advisor on mental health policy, "about a third of all suicides based on the current numbers are of people who have recently had contact with acute mental health services."

In his 2010 address to the National Press Club, former Australian of the Year Patrick McGorry outlined the dismal statistics of Australian mental illness. Six Australians kill themselves every day. Suicide kills more Australians than the road toll and is the single biggest killer for those under 40. The burden of mental ill-health is just as great. Nearly 1,000 Australians with mental ill-health present to hospitals for treatment every day, and many of our nation's homeless and unemployed are so in part because of their mental health problems. According to McGorry, mental health represents 13 per cent of the total disease burden, yet the mental health budget is just 6 per cent of the total funding mix.

So the need for mental health reform is large and pressing. Indeed, the federal government has always acknowledged this; it just hasn't done very much about it. This is particularly true for adolescent mental health. According to the government's budget document on the issue, "25 percent of people with a mental disorder experience their first episode before the age of 12 — half a million

children — and 64 per cent by age 21. Yet treatment rates for our young people are low: only 25 per cent for those aged 15 to 24 receive treatment."

The relevant budget document, issued by Ministers Roxon, Macklin and Butler, is rather long, but it's well worth a read. The "announceables", as Lindsay Tanner calls them, are impressive, including:

$571 million over five years for coordinated and integrated mental healthcare.

The idea here is a "no wrong door" approach which means eligible people will "will

now be able to access a comprehensive multidisciplinary assessment of their health and non-health needs, leading to a tailor-made care plan". The integrated care will feature "flexible funding … to fill gaps in clinical and non-clinical support for these consumers" and will be delivered at the local level through primary care providers such as Medicare Locals. There will be funding for some 24,000 mental health assessments

$220 million over five years for primary mental healthcare.

This is a welcome funding increase which targets one of the obvious gaps in our current healthcare system. The government says it will give Medicare Locals funding to connect to allied psychological services through the Access to Allied Psychological Services (ATAPS) program. This will support "over 180,000 people over five years, comprising 50,000 children and families, 18,000 Indigenous Australians and 116,000 other individuals in hard to reach groups."

$491.7 million over five years to expand and establish new youth focused mental health services.

This much-needed investment will fund things like new headspace centres, taking the national total to 90 headspace centres. There will also be support for an additional 12 Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centres (EPPIC), and an additional 40 Family Mental Health Support Services "to provide integrated prevention and early intervention services to over 30,000 children and young people at risk of mental illness, and their families."

$201 million to the states and territories to plug gaps in their own mental health services.

The government says these payments to the states will be a pooled grant fund that they can apply for funds to, in order "to focus on the priority areas of accommodation support and presentation, admission and discharge planning in emergency department."

However, as the Opposition (for once) correctly points out, only $571 million of this funding is actually new money provided in this budget. The rest has already been announced.

So far, the reaction to the package has been generally positive. Mendoza has praised it, telling the ABC that "I commend the Government for responding to not just the concerns of a few vocal advocates, but really the concerns across the Australian community."