Centre for Policy Development's Blog, page 120

May 15, 2011

John Menadue: On the Malaysian solution with ABC's 7.30

The number of asylum seekers to reach Australia by boat has actually declined compared with this time last year. Not that you'd know it from the political debate raging here. CPD's John Menadue joins ABC TV's 7.30 to put some perspective back into a deeply divided public to debate.

View the full segment here.

John Quiggin | Gillard's Labor Has Lost Its Heritage

Wayne Swan's Budget speech opened with a commendation of 'this Labor budget' and closed with an invocation of the past Labor governments which 'managed the transition from a closed economy to an open economy competing in the world.' But does anything distinctively Labor remain in the Gillard government?

Wayne Swan's Budget speech opened with a commendation of 'this Labor budget' and closed with an invocation of the past Labor governments which 'managed the transition from a closed economy to an open economy competing in the world.' But does anything distinctively Labor remain in the Gillard government?

It's difficult, from a social democratic perspective, to find much to criticise in the 2011-12 Budget. The much-touted cuts turned out to be far milder than predicted (some successful expectations management on the part of the government's spin doctors!). Most of the savings measures were reasonable enough in themselves, focusing on welfare measures that favored the well-off and on absurd anachronisms like the dependent spouse tax offset.

Unfortunately, it's equally difficult to find anything much to praise, let alone anything that could be regarded as distinctively associated with the values of the labour movement. The provision of substantial assistance to improve mental health is long overdue, but Tony Abbott took the lead on this issue as far back as the last election.

There are also some useful initiatives to help long-term unemployed people find work. However, as under the Howard government, all such measures come wreathed in clouds of punitive rhetoric. Such rhetoric doubtless works well in the focus groups where it has been tested, but it undercuts any attempt to present the Budget in terms of Labor's traditional concerns.

The biggest problems, though, are inherent in the government's overall fiscal strategy of holding growth in public expenditure to 1 or 2 per cent, implying a reduction in real expenditure per person and in the share of public expenditure in national income. In effect, the commitment is to restore the fiscal settings inherited from the Howard government (to be fair, these were little changed from the time when Howard himself took office).

While Rudd was PM, there was a tension between these commitments, and the desire to make substantial changes for the better, exemplified by the 'Education Revolution'. The tension became even sharper as a result of the Global Financial Crisis, which showed up the limitations of neoliberalism (or in my preferred terminology, market liberalism), and undermined the case for constraining the public sector based on neoliberal ideology. Rudd's advocacy of a social democratic response to the crisis implied a much more active role for government, and a rejection of the growing inequality associated with an economy dominated by the financial sector.

These commitments were eroded over the final year of Rudd's leadership and have disappeared entirely under Gillard. Having championed the Education Revolution before her ascension to power, Gillard was quick to drop it as PM. An embarrassing illustration was a Cabinet reshuffle in which the very word 'education' disappeared as the department was split into several parts. The nomenclature was hastily modified, but not Gillard's lack of interest in her former portfolio. As with her role model, John Howard, Gillard is much more comfortable with 'training' than with education.

The Budget is, in some sense, marking time. The only real reform likely under this government is the introduction of a carbon tax. But while Labor can reasonably claim a strong record on the environment over the years, Gillard cannot, having forced Rudd to abandon the emissions trading scheme, and herself promised not to introduce a price on carbon. If we get a carbon tax, it will be entirely due to the Greens.

Despite its absence from the list of budget measures, the proposed carbon tax stood, like Banquo's ghost at the banqueting table, behind a number of the measures announced on Tuesday night. The abolition of the Green Car scheme along with earlier announcements ending the subsidy for rooftop solar photovoltaic systems make some sense on the basis of the government's argument that these are inefficient substitutes for a carbon price.

But if the government now backs away, or fails to get the legislation through Parliament, it will be left, in effect, with nothing.

The critical importance of the carbon tax was doubtless one of the factors behind the heavy emphasis on regional Australia, also present in more coded form in giveaways targeted at small business 'ute owners'. The government needs the support of the regional independents, not only on votes of confidence but for the passage of this complex and controversial legislation.

If they can manage this (and Gillard has been remarkably successful in steering legislation through Parliament so far), the prospects for re-election will improve dramatically. The tax will have none of the disastrous effects claimed by its opponents. Its effects will be hard to detect against the background noise of a volatile economy.

Coming back to the Budget speech, it is notable that the reference to past Labor governments went back only to the role of the Hawke and Keating governments in opening up the Australian economy. While Hawke and Keating broadly accepted the neoliberal agenda dominant in the 1980s, they sought to combine it with the commitment to equality and public sector activism that had formed the basis of the Labor tradition represented by previous Labor governments. Hawke regularly invoked Curtin as a personal role model and sought to identify his government with the tradition represented by Curtin and Chifley. By contrast, for Gillard these men, and the socialist or social democratic ideas they stood for, belong to the dead past.

Bizarrely, it's now Tony Abbott who is invoking 'the ghost of Ben Chifley'. It's safe to say that Chifley would not have recognised his 'light on the hill' in the Abbott's opportunistic pandering. But Labor's all too obvious abandonment of its own traditions and values has allowed Abbott to get away with it.

Perhaps, when the longed-for surplus is finally regained, the Gillard government will finally reveal its true social democratic culture. But it seems far more likely that any post-surplus largesse will take the form of income tax cuts, populist bribes and payouts to favored business interests.

John Quiggin is a CPD fellow and an ARC Federation Fellow in Economics and Political Science at the University of Queensland. He is the author of Zombie Economics: How Dead Ideas Still Walk among Us.

Like what you read? Dive deaper into debates.

Like what you read? Dive deaper into debates.

Sign up for more good ideas. Follow us on Twitter @centrepolicydev & join us on Facebook. Donate to help make good ideas matter.

John Quiggin | Gillard's Labor is Losing its Heritage

Wayne Swan's Budget speech opened with a commendation of 'this Labor budget' and closed with an invocation of the past Labor governments which 'managed the transition from a closed economy to an open economy competing in the world.' But does anything distinctively Labor remain in the Gillard government?

Wayne Swan's Budget speech opened with a commendation of 'this Labor budget' and closed with an invocation of the past Labor governments which 'managed the transition from a closed economy to an open economy competing in the world.' But does anything distinctively Labor remain in the Gillard government?

It's difficult, from a social democratic perspective, to find much to criticise in the 2011-12 Budget. The much-touted cuts turned out to be far milder than predicted (some successful expectations management on the part of the government's spin doctors!). Most of the savings measures were reasonable enough in themselves, focusing on welfare measures that favored the well-off and on absurd anachronisms like the dependent spouse tax offset.

Unfortunately, it's equally difficult to find anything much to praise, let alone anything that could be regarded as distinctively associated with the values of the labour movement. The provision of substantial assistance to improve mental health is long overdue, but Tony Abbott took the lead on this issue as far back as the last election.

There are also some useful initiatives to help long-term unemployed people find work. However, as under the Howard government, all such measures come wreathed in clouds of punitive rhetoric. Such rhetoric doubtless works well in the focus groups where it has been tested, but it undercuts any attempt to present the Budget in terms of Labor's traditional concerns.

The biggest problems, though, are inherent in the government's overall fiscal strategy of holding growth in public expenditure to 1 or 2 per cent, implying a reduction in real expenditure per person and in the share of public expenditure in national income. In effect, the commitment is to restore the fiscal settings inherited from the Howard government (to be fair, these were little changed from the time when Howard himself took office).

While Rudd was PM, there was a tension between these commitments, and the desire to make substantial changes for the better, exemplified by the 'Education Revolution'. The tension became even sharper as a result of the Global Financial Crisis, which showed up the limitations of neoliberalism (or in my preferred terminology, market liberalism), and undermined the case for constraining the public sector based on neoliberal ideology. Rudd's advocacy of a social democratic response to the crisis implied a much more active role for government, and a rejection of the growing inequality associated with an economy dominated by the financial sector.

These commitments were eroded over the final year of Rudd's leadership and have disappeared entirely under Gillard. Having championed the Education Revolution before her ascension to power, Gillard was quick to drop it as PM. An embarrassing illustration was a Cabinet reshuffle in which the very word 'education' disappeared as the department was split into several parts. The nomenclature was hastily modified, but not Gillard's lack of interest in her former portfolio. As with her role model, John Howard, Gillard is much more comfortable with 'training' than with education.

The Budget is, in some sense, marking time. The only real reform likely under this government is the introduction of a carbon tax. But while Labor can reasonably claim a strong record on the environment over the years, Gillard cannot, having forced Rudd to abandon the emissions trading scheme, and herself promised not to introduce a price on carbon. If we get a carbon tax, it will be entirely due to the Greens.

Despite its absence from the list of budget measures, the proposed carbon tax stood, like Banquo's ghost at the banqueting table, behind a number of the measures announced on Tuesday night. The abolition of the Green Car scheme along with earlier announcements ending the subsidy for rooftop solar photovoltaic systems make some sense on the basis of the government's argument that these are inefficient substitutes for a carbon price.

But if the government now backs away, or fails to get the legislation through Parliament, it will be left, in effect, with nothing.

The critical importance of the carbon tax was doubtless one of the factors behind the heavy emphasis on regional Australia, also present in more coded form in giveaways targeted at small business 'ute owners'. The government needs the support of the regional independents, not only on votes of confidence but for the passage of this complex and controversial legislation.

If they can manage this (and Gillard has been remarkably successful in steering legislation through Parliament so far), the prospects for re-election will improve dramatically. The tax will have none of the disastrous effects claimed by its opponents. Its effects will be hard to detect against the background noise of a volatile economy.

Coming back to the Budget speech, it is notable that the reference to past Labor governments went back only to the role of the Hawke and Keating governments in opening up the Australian economy. While Hawke and Keating broadly accepted the neoliberal agenda dominant in the 1980s, they sought to combine it with the commitment to equality and public sector activism that had formed the basis of the Labor tradition represented by previous Labor governments. Hawke regularly invoked Curtin as a personal role model and sought to identify his government with the tradition represented by Curtin and Chifley. By contrast, for Gillard these men, and the socialist or social democratic ideas they stood for, belong to the dead past.

Bizarrely, it's now Tony Abbott who is invoking 'the ghost of Ben Chifley'. It's safe to say that Chifley would not have recognised his 'light on the hill' in the Abbott's opportunistic pandering. But Labor's all too obvious abandonment of its own traditions and values has allowed Abbott to get away with it.

Perhaps, when the longed-for surplus is finally regained, the Gillard government will finally reveal its true social democratic culture. But it seems far more likely that any post-surplus largesse will take the form of income tax cuts, populist bribes and payouts to favored business interests.

John Quiggin is a CPD fellow and an ARC Federation Fellow in Economics and Political Science at the University of Queensland. He is the author of Zombie Economics: How Dead Ideas Still Walk among Us.

Like what you read? Dive deaper into debates.

Like what you read? Dive deaper into debates.

Sign up for more good ideas. Follow us on Twitter @centrepolicydev & join us on Facebook. Donate to help make good ideas matter.

May 13, 2011

John Menadue: Malaysia refugee deal a rare chance to end cruel treatment

CPD's John Menadue, a former Secretary of the Department of Immigration, tells us what he thinks about the Gillard government's latest policy offering on asylum seekers. Could the so-called Malaysian solution be the circuit breaker we need?

Read John's full article in The Age here.

May 12, 2011

Ben Eltham | The Devil's In the Details – And There Were None

The Opposition is meant to function as an alternative government. It should be able to provide the people with alternative policies and, at the time of the budget, alternative costings to fund its proposed policies. But what happens when all the details are lacking?

Ben Eltham gives his view on the Opposition's budget reply and explains why he thinks it is not a viable alternative government.

Read his article in New Matilda here

The Ben Eltham | The Devil's In the Details – And There Were None

The Opposition is meant to function as an alternate government. It should be able to provide the people with alternate policies and at the time of the budget, alternate costings and budget measures. But what happens when all the details are lacking?

Ben Eltham explains his view on the Opposition's budget reply and explains why he thinks they are not a viable alternate government.

Read his article in New Matilda here

John Menadue | Trampling on Human Rights is Expensive

Asyl um seekers continue to suffer because of poll driven pol icie s and their fate remains an enormous political problem for A ustralia. John Menadue & Kate Gauthier add up how expensive trampling on human rights really is. They find that a new approach is not only urgently needed but that it but saves money too.

Next year (2011-12) the Government will spend $709 million in asylum seeker detention and related costs. This is up $147 million on this year (2010-11). This is about $90,000 for every asylum seeker that comes to Australia.

The abolition of mandatory detention of asylum seekers, which means mainly boat people, could save between $150 and $425 million per annum.

In chiding the Chinese about their human rights, Julia Gillard said that 'we believe (in human rights) … it is us. It's an Australian value.' How can she say this when we have 6,819 asylum seekers in detention in Australia who are entitled to our legal protection and hopefully, our compassion. They have this human right because in 1954 the Menzies Government brought into Australian law the Refugee Convention of 1951 followed by the protocol of 1967. Very few have committed any crime. They are imprisoned and humiliated because we mistakenly believe they are a threat. It is also good politics to act tough. The riots and burnings are a symptom of the problem. The problem is inhumane and expensive Government policies and a cynical Opposition barking at the Government's heels.

Hundreds of millions of dollars could be saved through ending mandatory detention and allocating funds to community detention by supporting NGOs such as the Red Cross and others. Such a policy still requires mandatory processing to establish identity and conduct health and security checks. But once those checks are conducted most asylum seekers should be released into the community. Community alternatives are more humane and can be tailored to the security needs of each person.

What does our heavy reliance on mandatory detention cost? In March this year, there were 6,819 persons in detention. 4,292 were in Immigration Detention Centres, mainly Christmas Island (1,831) and Curtin (1,197). The balance were in various forms of residential, transit or community detention. Let's assume that say, 3,500 could be moved out of Immigration Detention Centres to community detention, leaving 792 in detention centres awaiting removal for breach of visa conditions, rejected claims or security or character risks.

The UNHCR in their research series in April this year on Legal and Protection Policy (page 85) shows the savings in costs in switching from mandatory to community detention. It found that in 2005/06, the potential savings per person per day in Australia ranged from $333 to $117, depending on assumptions about the particular form of mandatory detention (e.g. remote facility) or community detention.

Given say 3,500 persons who could be moved into community detention, the savings per annum to the taxpayer could range from $425 million. (3,500 x $333 x 365 days) to $150 million (3,500 x $117 x 365 days). This estimate is based on conservative assumptions. The costs are for 2005-06, so we could add another 10%. Neither do the costs include the delayed mental and other health costs that mandatory detention triggers. They also do not include the large scale capital program the Government has foolishly undertaken to build more and more immigration detention centres and facilities.

The case for change is compelling, not just on grounds of cost.

The UNHCR in its Legal and Protection Policy series (April 2011) says 'pragmatically, no empirical evidence is available to give credence to the assumption that the threat of being detained deters irregular migration'. It also found that '90% or more of asylum seekers … complied with release conditions'.

The report commissioned by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) from the Social Policy Research Centre at the University of NSW in November 2009 said 'conditional release programs – such as supervision and bail – have proven a cost-effective way to minimise the detention of non-citizens and ensure their compliance.'

Australia is quite exceptional with its mandatory detention policy.

Over 80% of those in detention in Australia will be recognised anyway as genuine refugees.

It varies over time, but the Australian Parliamentary Library advises that in most years 70% to 97% of asylum seekers come by air. It was 84% in 2008-09 and 53% in 2009-10. Yet very few of them are detained. In March this year, 6,507 boat arrivals were in detention, but only 56 were unauthorised air arrivals. With so many coming by air, many of whom are Chinese, it is noteworthy that they are living in the community. Somehow we remain fixated on the relatively small number of boat people.

Further, by keeping almost all boat arrivals in detention, we are penalising the most deserving. Boat arrivals have 'success' rates in refugee determination of about 80% whilst for arrivals by air, it is 20%.

In keeping boat people behind razor wire and tear gassing when deemed appropriate, we quite wrongly confirm in the public mind that these people, who have escaped war and persecution, are illegals, criminals and a danger to the community. They are nothing of the sort.

In 1988, the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission argued that the policy of mandatory detention breached international human rights standards.

Professor Patrick McGorry has said that international detention centres are 'factories for producing mental illness and mental disorder'.

In February this year, the Commonwealth Ombudsman proposed to DIAC that a person who has received a positive Refugee Status Assessment should in a timely manner be released from immigration detention on Christmas Island and be placed in community detention on the Australian mainland subject to strict reporting conditions.

We are wasting money on a trivial problem. As an island at the end of the line, we have few asylum seekers compared with other countries. The Government has failed to explain or manage the issue.

Despite its harsh treatment of boat people, which did not change asylum flows to Australia, the Howard Government showed what could be done to ease mandatory detention. Starting in 2005, the Community Care Pilot was successful in almost every respect – cases were resolved more quickly, it was cheaper and absconding was minimal. This program was transitioned into Community Assistance Support in 2009. Such community-based processing and treatment of asylum seekers resulted in better compliance and better outcomes for everyone. Where given the opportunity, community-based programs have proven a much better method, not just because it respects human rights, but also because it is cheaper and faster.

There are some encouraging signs that the Government is changing course on mandatory detention. It must move decisively to end the mandatory detention that the Hawke Government introduced. Unfortunately the Government's timidity, policy confusion and the unscrupulous behaviour of the Opposition stand in the way of sensible reform.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Sign up for more good ideas. Follow us onTwitter @centrepolicydev & join us on Facebook. Donate to help make good ideas matter.

John Menadue & Kate Gauthier | Trampling on Human Rights is Expensive

Asyl um seekers continue to suffer because of poll driven pol icie s and their fate remains an enormous political problem for A ustralia. John Menadue & Kate Gauthier add up how expensive trampling on human rights really is. They find that a new approach is not only urgently needed but that it but saves money too.

Next year (2011-12) the Government will spend $709 million in asylum seeker detention and related costs. This is up $147 million on this year (2010-11). This is about $90,000 for every asylum seeker that comes to Australia.

The abolition of mandatory detention of asylum seekers, which means mainly boat people, could save between $150 and $425 million per annum.

In chiding the Chinese about their human rights, Julia Gillard said that 'we believe (in human rights) … it is us. It's an Australian value.' How can she say this when we have 6,819 asylum seekers in detention in Australia who are entitled to our legal protection and hopefully, our compassion. They have this human right because in 1954 the Menzies Government brought into Australian law the Refugee Convention of 1951 followed by the protocol of 1967. Very few have committed any crime. They are imprisoned and humiliated because we mistakenly believe they are a threat. It is also good politics to act tough. The riots and burnings are a symptom of the problem. The problem is inhumane and expensive Government policies and a cynical Opposition barking at the Government's heels.

Hundreds of millions of dollars could be saved through ending mandatory detention and allocating funds to community detention by supporting NGOs such as the Red Cross and others. Such a policy still requires mandatory processing to establish identity and conduct health and security checks. But once those checks are conducted most asylum seekers should be released into the community. Community alternatives are more humane and can be tailored to the security needs of each person.

What does our heavy reliance on mandatory detention cost? In March this year, there were 6,819 persons in detention. 4,292 were in Immigration Detention Centres, mainly Christmas Island (1,831) and Curtin (1,197). The balance were in various forms of residential, transit or community detention. Let's assume that say, 3,500 could be moved out of Immigration Detention Centres to community detention, leaving 792 in detention centres awaiting removal for breach of visa conditions, rejected claims or security or character risks.

The UNHCR in their research series in April this year on Legal and Protection Policy (page 85) shows the savings in costs in switching from mandatory to community detention. It found that in 2005/06, the potential savings per person per day in Australia ranged from $333 to $117, depending on assumptions about the particular form of mandatory detention (e.g. remote facility) or community detention.

Given say 3,500 persons who could be moved into community detention, the savings per annum to the taxpayer could range from $425 million. (3,500 x $333 x 365 days) to $150 million (3,500 x $117 x 365 days). This estimate is based on conservative assumptions. The costs are for 2005-06, so we could add another 10%. Neither do the costs include the delayed mental and other health costs that mandatory detention triggers. They also do not include the large scale capital program the Government has foolishly undertaken to build more and more immigration detention centres and facilities.

The case for change is compelling, not just on grounds of cost.

The UNHCR in its Legal and Protection Policy series (April 2011) says 'pragmatically, no empirical evidence is available to give credence to the assumption that the threat of being detained deters irregular migration'. It also found that '90% or more of asylum seekers … complied with release conditions'.

The report commissioned by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) from the Social Policy Research Centre at the University of NSW in November 2009 said 'conditional release programs – such as supervision and bail – have proven a cost-effective way to minimise the detention of non-citizens and ensure their compliance.'

Australia is quite exceptional with its mandatory detention policy.

Over 80% of those in detention in Australia will be recognised anyway as genuine refugees.

It varies over time, but the Australian Parliamentary Library advises that in most years 70% to 97% of asylum seekers come by air. It was 84% in 2008-09 and 53% in 2009-10. Yet very few of them are detained. In March this year, 6,507 boat arrivals were in detention, but only 56 were unauthorised air arrivals. With so many coming by air, many of whom are Chinese, it is noteworthy that they are living in the community. Somehow we remain fixated on the relatively small number of boat people.

Further, by keeping almost all boat arrivals in detention, we are penalising the most deserving. Boat arrivals have 'success' rates in refugee determination of about 80% whilst for arrivals by air, it is 20%.

In keeping boat people behind razor wire and tear gassing when deemed appropriate, we quite wrongly confirm in the public mind that these people, who have escaped war and persecution, are illegals, criminals and a danger to the community. They are nothing of the sort.

In 1988, the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission argued that the policy of mandatory detention breached international human rights standards.

Professor Patrick McGorry has said that international detention centres are 'factories for producing mental illness and mental disorder'.

In February this year, the Commonwealth Ombudsman proposed to DIAC that a person who has received a positive Refugee Status Assessment should in a timely manner be released from immigration detention on Christmas Island and be placed in community detention on the Australian mainland subject to strict reporting conditions.

We are wasting money on a trivial problem. As an island at the end of the line, we have few asylum seekers compared with other countries. The Government has failed to explain or manage the issue.

Despite its harsh treatment of boat people, which did not change asylum flows to Australia, the Howard Government showed what could be done to ease mandatory detention. Starting in 2005, the Community Care Pilot was successful in almost every respect – cases were resolved more quickly, it was cheaper and absconding was minimal. This program was transitioned into Community Assistance Support in 2009. Such community-based processing and treatment of asylum seekers resulted in better compliance and better outcomes for everyone. Where given the opportunity, community-based programs have proven a much better method, not just because it respects human rights, but also because it is cheaper and faster.

There are some encouraging signs that the Government is changing course on mandatory detention. It must move decisively to end the mandatory detention that the Hawke Government introduced. Unfortunately the Government's timidity, policy confusion and the unscrupulous behaviour of the Opposition stand in the way of sensible reform.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Sign up for more good ideas. Follow us onTwitter @centrepolicydev & join us onFacebook. Donate to help make good ideas matter.

Ben Eltham | Picking Through the Scraps of Budget Arts Funding

The 2011 federal budget contained some modest announcements for the arts and culture.

In the Arts portfolio, the government delivered on its 2010 election promise for $10 million over five years in new grants for artists to create work. The funding will support "up to 150 additional artistic works, presentations and fellowships over the next five years through the New Support for the Arts program."

As well, $400,000 has been found for the federal government's Contemporary Music Touring Program, a successful program which supports popular mid-level contemporary music acts to tour regional areas.

In broadcasting, $12.5 million has been provided for the proverbially penurious community radio sector, an increase of 25% for a critical area of broadcasting that generally receives very little government support

There was also a package for the screen industry, with a headline figure of $66 million (as we will see, it is actually less than this). Much of the extra money goes to production subsidies through the tax system in the form of lower qualifying thresholds for the Screen Production Incentive. According to Screen Australia, the changes include:

Lowering the threshold for Producer Offset eligibility from $1 million to $500,000, for features, TV and online programs

Replacing the Producer Offset for low-budget docos with a Producer Equity payment

Converting the 65 episode cap to 65 commercial hours for TV

Exempting documentaries from the 20% above-the-line cap

A reduction in qualifying Australian production expenditure thresholds, and allowances for a broader range of expenses to be eligible for QAPE.

Some really good news is the restoration of the Australian Bureau of Statistics' screen industry survey, which provided gold-standard data on the state of the industry and which hasn't been performed since 2007-08 (shortly before the Rudd government slashed funding to the ABS in its first budget).

But how much new money for screen is really here? Go to Budget Paper 2 and you will find that the total extra funding is only $8 million. This is because, quoting from the budget papers, "these changes will be partly offset by $48 million in savings over four years from 2011-12 by removing the Goods and Services Tax (GST) amounts from [qualifying production expenditure] for the film tax offsets and increasing the minimum expenditure thresholds for documentaries to $500,000 in production (from the current threshold of $250,000)."

Money is also being clawed back from cultural agencies through the increased efficiency dividend. Rising to 1.5% in future years, the efficiency dividend hits smaller agencies much harder than big ones. And everything in the arts is small.

The efficiency dividend measures mean the Australia Council is being asked to save $3.3 million over the forward estimates, the Australian Film Television and Radio School will have to find $1 million, the National Film and Sound Archive $1.1 million, the National Gallery $1.4 million, the National Library $2.1 million, the National Museum $1.7, and Screen Australia $759,000. That's more than $12 million in funding cuts for cultural agencies over the forward estimates.

If we look a little closer at the portfolio budget statements, for instance from the Australia Council, we can see the effects of the efficiency dividend in falling support for artists and cultural organisations. This year there will be "a decrease of approximately $2.5 million in forecast grants expenses compared with 2010-11." Australia Council grants funding will be only 2% above 2010 levels in 2014-15. But CPI is forecast to run at 3% annually, meaning Australia Council support for artists and organisations will fall in real terms — by perhaps as much as 10%.

In other words, the "New Funding for the Arts" money announced in this budget will be almost completely clawed back by the effects of static funding and the increased efficiency dividend on the Australia Council.

The one really big-ticket spending item in culture was of dubious policy value: the $376 million spend on helping pensioners and senior Australians to make the switch to digital TV. Opposition leader Tony Abbott has already pilloried the program as "Building the Entertainment Revolution", while our own Bernard Keane and Glenn Dyer have pointed out "the political imperative of ensuring pensioners aren't left without television as analog signals switch off".

Personally, I'm sympathetic to the argument that television represents an important human service that allows older Australians to stay connected with the broader community. But the spending program should also be seen in the context of the broader budget, in which $211 million in spending is being "saved" from aged care itself. The government appears to be prioritising access to daytime television over places in aged-care facilities.

Money for art and culture is often spuriously disparaged by critics as diverting resources away from the critical services that governments provide. In reality, of course, the numbers are tiny compared to the investments annually in roads, schools and hospitals. But in this case it really does seem as though the owners of television networks are getting a subsidy at the expense of much-needed investment in aged care infrastructure.

As first published in Crikey here

Ian McAuley | A Glimmer of Vision to a Close Horizon

[image error]

Is the surplus fetish distracting the Government from the real economic challenges? Ian McAuley finds glimpses of Labor values in an otherwise short-sighted budget.

In the Budget is a glimmer of traditional Labor principles. Although it is tough on some welfare provisions, it is mildly re-distributive, and it acknowledges the need to make structural changes to the Australian economy. It has made some cautious moves to wind back middle class welfare payments and tax breaks, which have been putting pressure on other areas of public expenditure.

The Government could have been bolder however, much bolder. It seems unfortunately to be constrained by two obsessions: one to do with the cash deficit and the other to do with not raising taxes. These obsessions are limiting the Government's capacity to make much-needed public investments and to provide the public services needed in a prosperous and dynamic economy. One manifestation of our low-tax obsession is likely to be pressure on state services, because the GST revenue upon which states depend is growing very slowly.

It looks like a Labor Budget

To deal with the political vision first, there is a degree of re-distribution away from "middle-class welfare". The Dependent Spouse Tax Offset is to be phased out, income thresholds for family payments are to be frozen, the use of trusts to divert income to children is to be made less attractive, employer-provided company cars will be more reasonably taxed, and the Government retains its commitment to place a means test on the private health insurance rebate.

At the same time there is an emphasis on employment, particularly in raising labour force participation. Most attention is focussed on measures to move people from disability support payments to the workforce, but even the changes in the dependent spouse allowances can be seen in terms of workforce participation, for Australia, in contrast to other prosperous countries, has low workforce participation among women past child-bearing age.

This Budget therefore contains a set of incentives for workforce participation and for skills acquisition, with new training packages and incentives for young people to continue in education.

Transfer pa yments are crowding out direct spending

While these policies may appear to be a simple application of common sense in an economy approaching full employment, and which needs to lift its productivity performance, they do represent a break from the pattern which became so entrenched by the Howard-Costello administration when it used the windfall revenues from growth to support middle-class welfare.

Over the last thirty years, as the Australian economy has lost support mechanisms such as tariff protection and has become more exposed to foreign and domestic competition, income disparities have widened. The guiding economic philosophy has been to accept rising inequality as a by-product of market liberalization, and to use transfer payments to individuals to compensate those who are left behind, including people in the middle classes. This trend is shown strongly in Figure 1: until 1975 social assistance payments constituted only about five percent of household income, and they were concentrated on the very poorest. As the economy has opened up, they have risen, and they reached twelve to thirteen percent of income during the Howard-Costello years. (The 2009 blip results from the stimulus handouts.) Moreover, they now reach into a growing share of the population: last year seven million Australians were receiving some form of Centrelink payment.

A different and more sustainable policy is to develop a strong economy that can provide well-paid work for all, thus reducing the need for welfare payments to supplement people's earnings. For this to come about, we must invest in skills, and this seems to be the direction in which this Government is headed, albeit very tentatively. It is about reducing welfare dependence, providing social inclusion through meaningful work rather than welfare transfers, and freeing up public expenditure for other purposes.

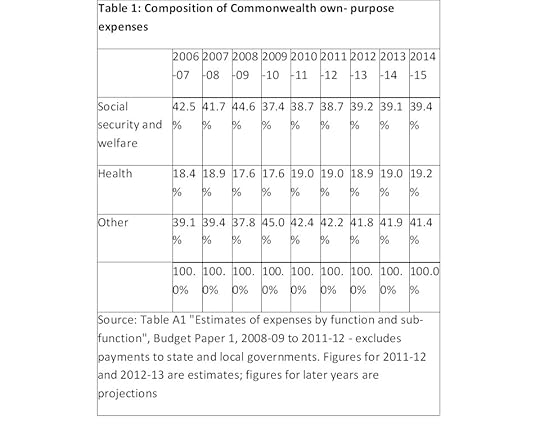

The way welfare transfers have been squeezing other areas of public expenditure is evident from an examination of the composition of recent budgets, presented in Table 1. This table shows a broad breakdown of Commonwealth outlays, separately identifying social security and welfare, and health, leaving a residual "other" category. This "other" category includes functions such as defence, education, housing and transport – a whole range of public goods provided by or funded by the Commonwealth.

This presentation reveals four fiscal developments:

This presentation reveals four fiscal developments:• In the final years of the Howard-Costello administration, social security and welfare reached high levels, crowding out other areas of expenditure.

• The big boost in social security and welfare in the first full year of the Rudd-Swan administration reflects the temporary stimulus payments to individuals.

• The boost in "other" in 2009-10, was for ongoing stimulus payments such as payments for school buildings.

• There is a reversion to a plateau of about 41 to 42 percent for "other" payments in the outer years.

What we are now seeing is a small re-allocation of budget priorities – to compensate for the reliance on welfare to mask inequalities that has developed over the last thirty years, and a stronger emphasis on government programs.

Tax expenditures are eating the budget

These figures on budgetary welfare payments, however, reveal only part of the story; what they do not reveal are missed opportunities for more fundamental reform. They do not show the ongoing generous tax concessions, mainly of benefit to the better-off. The Commonwealth will have raised $243 billion in tax in 2010-11, but it will have also forgone $49 billion in "tax expenditures" – taxes that are not collected because of various exemptions and deductions. These include the exemption of houses from capital gains tax, concessions for superannuation, GST exemptions for food, education, financial supplies and health care, and many other concessions.

[image error]

Some of these concessions are easy to justify, but many others have little, if any, justification in terms of equity or economic efficiency. Some concessions, such as the generous treatment of investment housing, or the low rate of capital gains tax on short-term investments, do not show up at all in budget papers.

There are other missed opportunities for revenue collection, many of which were suggested in the Henry Review, such as bequest taxes. The rate of excise tax on diesel and gasoline has been frozen in nominal terms since the Howard-Costello Government left it at 38 cents a litre in 2001; had indexation been applied we would be now raising another four to five billion dollars a year, and the transition to carbon pricing would be easier. Allowing the real rate of excise to fall has shielded us from the inevitability of higher energy prices.

What this means is that there is plenty of scope to raise tax revenue, without raising the basic rates of GST or income tax.

Taking the wrong ro ad to a surplus

Instead, the Government is to meet its budgetary commitment of a cash balance by 2012-13 through reliance on economic growth (including recovery from a summer of natural disasters), restoration of corporate taxes as reported profits rise, modest cuts to middle class welfare, and a set of nitpicking cuts in public services, including the misnamed "efficiency dividend" applied to the public service.

As long as the Government feels it cannot raise more revenue, and as long as it continues to provide a decent level of transfer payments, Australia is facing a continuation of severely constrained expenditure on public services, with the occasional short-lived boost from a Keynesian stimulus. Governments, state and federal, will either neglect public services, or will go on using expensive, inefficient and inequitable means of funding and providing services – such as public-private partnerships, privatization of natural monopolies, high user fees and private insurance for health care. "Social inclusion" will remain no more than a pious hope, as those who can afford to use private education, to live in gated communities, and to opt out of using public services, set themselves apart from other Australians.

The issue being avoided by this and previous administrations is that Australia is one of the lowest taxed countries in the developed world. Out of the 32 countries in the OECD, only Turkey, Mexico and the USA collect less tax as a proportion of their GDP. At 27 percent of GDP, our tax revenue compares with a 35 percent average for the OECD; the difference is about the same as the revenue forgone through our tax expenditures. And many of these OECD countries, particularly the USA, are going to have to raise their taxes to cope with high and unsustainable levels of government debt. Yet, the Government has specifically stated an aim to "keep taxation as a share of GDP below the level for 2007-08 (23.5 per cent of GDP), on average".

[image error]

Overstretched states could push for bolder approach

Perhaps the strongest immediate pressure for an increase in revenue will come from state governments, including the three non-Labor governments, which now hold office in states with 15 million of our 22 million population. States provide some of the most difficult and intrinsically labour-intensive public services, including school education, hospitals, and policing. But because of their dependence on GST for about 40 percent of their finances, they are facing strong revenue pressures.

In the years leading up to the global financial crisis, when Australians spent all they earned and more, GST receipts were strong, but we are now in a saving mode. Worse, for GST collection, spending has been sustained or increased in GST-exempt health care and food, while the cuts have been taken in other items that are subject to GST. The Budget papers cover this point, noting that just in the six months since the government prepared its mid year estimates, projections of GST payments to the states over the next four years are likely to fall by $5.9 billion, but there is no suggestion as to how such a funding gap may be filled. Admittedly there are some offsetting benefits for the states in health care and in grants for workforce training, but these come at a cost to state autonomy.

Some will call for an increase in the GST rate, or an abolition of GST exemptions, but politically these are unlikely to happen, particularly when the Commonwealth would suffer the odium and the states would get the benefit. States may seek to increase their own taxes, but most state taxes are costly to collect and are inequitable, for they have only a narrow taxation base. Cutting public services is not an appealing option, for the newly-elected governments of New South Wales and Victoria owe their electoral success, in large part, to dissatisfaction with the level and quality of public services. They don't have the luxury of their federal colleagues who, from opposition benches, can call for unspecified cuts in public expenditure.

Putting state revenues on a stronger footing is one of the neglected pieces of fiscal policy, and is likely to be a strong issue in coming months. It promises to produce an enlivened debate, particularly seeing it cuts across partisan boundaries. Perhaps that will be the source of pressure for doing something about tax expenditures.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Like what you've read? Dive into deeper debates.

Sign up for more good ideas. Follow us onTwitter@centrepolicydev & join us on Facebook. Donate to help make good ideas matter.

Centre for Policy Development's Blog

- Centre for Policy Development's profile

- 1 follower