Kenneth Atchity's Blog, page 91

September 2, 2019

J. E. Nicassio, Author of "From the Sky" receives coveted Book Excellence Award

J. E. Nicassio‘s "From the Sky" Trilogy Vol. 1 wins a Book Excellence Award in the Science fiction category.

Available on Amazon

Available on Amazon

Founded in Toronto, Ontario, the Book Excellence Awards is an international book awards competition dedicated to recognizing both independent and traditionally published authors and publishers for excellence in writing, design and overall market appeal. Previous Winners and Finalists of the Book Excellence Awards have doubled their book sales, garnered attention from film producers, received the distribution in bookstores, and increased their visibility and media attention.

“The Book Excellence Awards is highly recognized in the literary community. I was thrilled and honored to receive such a prestigious book award for my first novel. This will open many doors for me.”

From the Sky is a thrilling and poignant novel that is not only worthy of being read by all readers, but it will open their eyes to the possibility of life among the stars, which is why J. E, Nicassio wrote the book.

From the Sky is the story about Lucien Foster and Samantha Hunter. Lucien Foster never expected Samantha Hunter to live after he tried to save her from a car accident that killed her twin brother instantly. But, for some inexplicable reason, her body accepted his alien blood. Now, not only is she alive, she’s changing, becoming stronger. But there’s one problem: the rogue government agency MJ 12 that’s been after Lucien and his family from the start, knows her secret. Sam is the only human to thrive with alien DNA in her system, meaning she’s the one. Through her, MJ 12 can start to re-populate the planet with an alien/human hybrid, a superhuman.

J.E. Nicassio gives readers insight into the Roswell crash, government cover- ups, and the supernatural. The book helps readers learn more about the unusual and UFO’s and historical sighting, whether they are young adults or adults.

Nicassio’s book has already received some great reviews from industry leaders.‘I just wish I could figure all this out – An exceptional novel!'

Pennsylvania author Jennie E. Nicassio is a former freelance writer, MUFON (Mutual UFO Network) field investigator, and the author of ROCKY, LOUIS-JOSEPH’S OOH RAH, HAUNTING SHORT TALES OF TWILA, and SOUL WALKER the From the Sky Trilogy, of which FROM THE SKY is Volume 1. Her writing reflects her fascination with life on other planets, and she has become well known for her fascinating paranormal fantasy works. She lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The depth and sensitivity of Jennie’s projected trilogy are evident in the quotation she places at book’s opening: ‘Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe, or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.” – Arthur C. Clarke. Knowing her passion for UFOs and the probability of life on other planets, this book sails into the mind with surety and succeeds in transporting the reader into Jennie’s special realm.

The tale begins in Pittsburgh with an auto accident in which Samantha (aka Sam) survives while her twin brother Finn succumbs Sam is visited by a stranger who comforts her, saying she will not die, and then disappears. Months pass, Sam’s mother dies in a depressed state, and Sam once again views the stranger in the cemetery after her mother’s funeral. Moving to New Mexico with her father’s new university position as Dean of the Archaeology Department, Sam continues to encounter visions of the stranger. Gradually she learns the stranger is from another planet, and her life becomes more complex after meeting the strange but enchanting Lucien Foster. From this point on the story becomes a much a mystery thriller as a fantasy, so perfectly blended is the line that normally separates reality and the unknown – intrigue, alien conspiracies, and yes, romance.

Though written for the Young Adult audience, this book is so fine that it is equally irresistible for imaginative adults. Exceptional writing, this, and an outstanding opening chapter of Jennie’s successful trilogy. Highly recommended,” wrote Grady Harp, San Francisco Review of Books.

About the Book Excellence Awards – Founded in Toronto, Canada, the Book Excellence Awards is an international book awards competition dedicated to recognizing both independent and traditionally published authors for excellence in writing, design and overall market appeal. Previous Winners and Finalists of the Book Excellence Awards have been New York Times’ best-sellers, spoken at the United Nations and TEDx, and have had their books optioned by movie studios. To learn more, visit: https://www.bookexcellenceawards.com.

Media Contact

J. E. Nicassio jen3963@comcast.net https://www.jenicassio.com/

Available on Amazon

Available on AmazonFounded in Toronto, Ontario, the Book Excellence Awards is an international book awards competition dedicated to recognizing both independent and traditionally published authors and publishers for excellence in writing, design and overall market appeal. Previous Winners and Finalists of the Book Excellence Awards have doubled their book sales, garnered attention from film producers, received the distribution in bookstores, and increased their visibility and media attention.

“The Book Excellence Awards is highly recognized in the literary community. I was thrilled and honored to receive such a prestigious book award for my first novel. This will open many doors for me.”

From the Sky is a thrilling and poignant novel that is not only worthy of being read by all readers, but it will open their eyes to the possibility of life among the stars, which is why J. E, Nicassio wrote the book.

From the Sky is the story about Lucien Foster and Samantha Hunter. Lucien Foster never expected Samantha Hunter to live after he tried to save her from a car accident that killed her twin brother instantly. But, for some inexplicable reason, her body accepted his alien blood. Now, not only is she alive, she’s changing, becoming stronger. But there’s one problem: the rogue government agency MJ 12 that’s been after Lucien and his family from the start, knows her secret. Sam is the only human to thrive with alien DNA in her system, meaning she’s the one. Through her, MJ 12 can start to re-populate the planet with an alien/human hybrid, a superhuman.

J.E. Nicassio gives readers insight into the Roswell crash, government cover- ups, and the supernatural. The book helps readers learn more about the unusual and UFO’s and historical sighting, whether they are young adults or adults.

Nicassio’s book has already received some great reviews from industry leaders.‘I just wish I could figure all this out – An exceptional novel!'

Pennsylvania author Jennie E. Nicassio is a former freelance writer, MUFON (Mutual UFO Network) field investigator, and the author of ROCKY, LOUIS-JOSEPH’S OOH RAH, HAUNTING SHORT TALES OF TWILA, and SOUL WALKER the From the Sky Trilogy, of which FROM THE SKY is Volume 1. Her writing reflects her fascination with life on other planets, and she has become well known for her fascinating paranormal fantasy works. She lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The depth and sensitivity of Jennie’s projected trilogy are evident in the quotation she places at book’s opening: ‘Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe, or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.” – Arthur C. Clarke. Knowing her passion for UFOs and the probability of life on other planets, this book sails into the mind with surety and succeeds in transporting the reader into Jennie’s special realm.

The tale begins in Pittsburgh with an auto accident in which Samantha (aka Sam) survives while her twin brother Finn succumbs Sam is visited by a stranger who comforts her, saying she will not die, and then disappears. Months pass, Sam’s mother dies in a depressed state, and Sam once again views the stranger in the cemetery after her mother’s funeral. Moving to New Mexico with her father’s new university position as Dean of the Archaeology Department, Sam continues to encounter visions of the stranger. Gradually she learns the stranger is from another planet, and her life becomes more complex after meeting the strange but enchanting Lucien Foster. From this point on the story becomes a much a mystery thriller as a fantasy, so perfectly blended is the line that normally separates reality and the unknown – intrigue, alien conspiracies, and yes, romance.

Though written for the Young Adult audience, this book is so fine that it is equally irresistible for imaginative adults. Exceptional writing, this, and an outstanding opening chapter of Jennie’s successful trilogy. Highly recommended,” wrote Grady Harp, San Francisco Review of Books.

About the Book Excellence Awards – Founded in Toronto, Canada, the Book Excellence Awards is an international book awards competition dedicated to recognizing both independent and traditionally published authors for excellence in writing, design and overall market appeal. Previous Winners and Finalists of the Book Excellence Awards have been New York Times’ best-sellers, spoken at the United Nations and TEDx, and have had their books optioned by movie studios. To learn more, visit: https://www.bookexcellenceawards.com.

Media Contact

J. E. Nicassio jen3963@comcast.net https://www.jenicassio.com/

Published on September 02, 2019 00:00

J. E. Nicassio, Author of From the Sky receives coveted Book Excellence Award

J. E. Nicassio‘s From the SkyTrilogy Vol. 1 wins a Book Excellence Award in the Science fiction category.

Available on Amazon

Available on Amazon

Founded in Toronto, Ontario, the Book Excellence Awards is an international book awards competition dedicated to recognizing both independent and traditionally published authors and publishers for excellence in writing, design and overall market appeal. Previous Winners and Finalists of the Book Excellence Awards have doubled their book sales, garnered attention from film producers, received the distribution in bookstores, and increased their visibility and media attention.

“The Book Excellence Awards is highly recognized in the literary community. I was thrilled and honored to receive such a prestigious book award for my first novel. This will open many doors for me.”

From the Sky is a thrilling and poignant novel that is not only worthy of being read by all readers, but it will open their eyes to the possibility of life among the stars, which is why J. E, Nicassio wrote the book.

From the Sky is the story about Lucien Foster and Samantha Hunter. Lucien Foster never expected Samantha Hunter to live after he tried to save her from a car accident that killed her twin brother instantly. But, for some unexplainable reason, her body accepted his alien blood. Now, not only is she alive, she’s changing, becoming stronger. But there’s one problem: the rogue government agency MJ 12 that’s been after Lucien and his family from the start, knows her secret. Sam is the only human to thrive with alien DNA in her system, meaning she’s the one. Through her, MJ 12 can start to re-populate the planet with an alien/human hybrid, a superhuman.

• J.E. Nicassio gives readers insight into the Roswell crash, government cover- ups, and the supernatural. The book helps readers learn more about the unusual and UFO’s and historical sighting, whether they are young adults or adults.

Nicassio’s book has already received some great reviews from industry leaders.

“‘I just wish I could figure all this out’ – An exceptional novel!

Pennsylvania author Jennie E. Nicassio is a former freelance writer, MUFON (Mutual UFO Network) field investigator, and the author of ROCKY, LOUIS-JOSEPH’S OOH RAH, HAUNTING SHORT TALES OF TWILA, and SOUL WALKER the From the Sky Trilogy, of which FROM THE SKY is Volume 1. Her writing reflects her fascination with life on other planets, and she has become well known for her fascinating paranormal fantasy works. She lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The depth and sensitivity of Jennie’s projected trilogy are evident in the quotation she places at book’s opening: ‘Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe, or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.” – Arthur C. Clarke. Knowing her passion for UFOs and the probability of life on other planets, this book sails into the mind with surety and succeeds in transporting the reader into Jennie’s special realm.

The tale begins in Pittsburgh with an auto accident in which Samantha (aka Sam) survives while her twin brother Finn succumbs Sam is visited by a stranger who comforts her, saying she will not die, and then disappears. Months pass, Sam’s mother dies in a depressed state, and Sam once again views the stranger in the cemetery after her mother’s funeral. Moving to New Mexico with her father’s new university position as Dean of the Archaeology Department, Sam continues to encounter visions of the stranger. Gradually she learns the stranger is from another planet, and her life becomes more complex after meeting the strange but enchanting Lucien Foster. From this point on the story becomes a much a mystery thriller as a fantasy, so perfectly blended is the line that normally separates reality and the unknown – intrigue, alien conspiracies, and yes, romance.

Though written for the Young Adult audience, this book is so fine that it is equally irresistible for imaginative adults. Exceptional writing, this, and an outstanding opening chapter of Jennie’s successful trilogy. Highly recommended,” wrote Grady Harp, San Francisco Review of Books.

About the Book Excellence Awards – Founded in Toronto, Canada, the Book Excellence Awards is an international book awards competition dedicated to recognizing both independent and traditionally published authors for excellence in writing, design and overall market appeal. Previous Winners and Finalists of the Book Excellence Awards have been New York Times’ best-sellers, spoken at the United Nations and TEDx, and have had their books optioned by movie studios. To learn more, visit: https://www.bookexcellenceawards.com.

Media Contact

J. E. Nicassio jen3963@comcast.net https://www.jenicassio.com/

Available on Amazon

Available on AmazonFounded in Toronto, Ontario, the Book Excellence Awards is an international book awards competition dedicated to recognizing both independent and traditionally published authors and publishers for excellence in writing, design and overall market appeal. Previous Winners and Finalists of the Book Excellence Awards have doubled their book sales, garnered attention from film producers, received the distribution in bookstores, and increased their visibility and media attention.

“The Book Excellence Awards is highly recognized in the literary community. I was thrilled and honored to receive such a prestigious book award for my first novel. This will open many doors for me.”

From the Sky is a thrilling and poignant novel that is not only worthy of being read by all readers, but it will open their eyes to the possibility of life among the stars, which is why J. E, Nicassio wrote the book.

From the Sky is the story about Lucien Foster and Samantha Hunter. Lucien Foster never expected Samantha Hunter to live after he tried to save her from a car accident that killed her twin brother instantly. But, for some unexplainable reason, her body accepted his alien blood. Now, not only is she alive, she’s changing, becoming stronger. But there’s one problem: the rogue government agency MJ 12 that’s been after Lucien and his family from the start, knows her secret. Sam is the only human to thrive with alien DNA in her system, meaning she’s the one. Through her, MJ 12 can start to re-populate the planet with an alien/human hybrid, a superhuman.

• J.E. Nicassio gives readers insight into the Roswell crash, government cover- ups, and the supernatural. The book helps readers learn more about the unusual and UFO’s and historical sighting, whether they are young adults or adults.

Nicassio’s book has already received some great reviews from industry leaders.

“‘I just wish I could figure all this out’ – An exceptional novel!

Pennsylvania author Jennie E. Nicassio is a former freelance writer, MUFON (Mutual UFO Network) field investigator, and the author of ROCKY, LOUIS-JOSEPH’S OOH RAH, HAUNTING SHORT TALES OF TWILA, and SOUL WALKER the From the Sky Trilogy, of which FROM THE SKY is Volume 1. Her writing reflects her fascination with life on other planets, and she has become well known for her fascinating paranormal fantasy works. She lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The depth and sensitivity of Jennie’s projected trilogy are evident in the quotation she places at book’s opening: ‘Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe, or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.” – Arthur C. Clarke. Knowing her passion for UFOs and the probability of life on other planets, this book sails into the mind with surety and succeeds in transporting the reader into Jennie’s special realm.

The tale begins in Pittsburgh with an auto accident in which Samantha (aka Sam) survives while her twin brother Finn succumbs Sam is visited by a stranger who comforts her, saying she will not die, and then disappears. Months pass, Sam’s mother dies in a depressed state, and Sam once again views the stranger in the cemetery after her mother’s funeral. Moving to New Mexico with her father’s new university position as Dean of the Archaeology Department, Sam continues to encounter visions of the stranger. Gradually she learns the stranger is from another planet, and her life becomes more complex after meeting the strange but enchanting Lucien Foster. From this point on the story becomes a much a mystery thriller as a fantasy, so perfectly blended is the line that normally separates reality and the unknown – intrigue, alien conspiracies, and yes, romance.

Though written for the Young Adult audience, this book is so fine that it is equally irresistible for imaginative adults. Exceptional writing, this, and an outstanding opening chapter of Jennie’s successful trilogy. Highly recommended,” wrote Grady Harp, San Francisco Review of Books.

About the Book Excellence Awards – Founded in Toronto, Canada, the Book Excellence Awards is an international book awards competition dedicated to recognizing both independent and traditionally published authors for excellence in writing, design and overall market appeal. Previous Winners and Finalists of the Book Excellence Awards have been New York Times’ best-sellers, spoken at the United Nations and TEDx, and have had their books optioned by movie studios. To learn more, visit: https://www.bookexcellenceawards.com.

Media Contact

J. E. Nicassio jen3963@comcast.net https://www.jenicassio.com/

Published on September 02, 2019 00:00

August 30, 2019

August 29, 2019

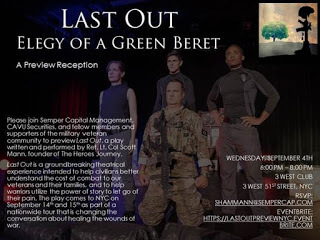

Lt. Col. Scott Mann's "Last Out- Elegy of a Green Beret' September 14th and 15th at the Kraine Theater in NYC

After terrorists launched an attack on the United States on September 11, 2001, Lt. Col. Scott Mann and his teammates in the 7th Special Forces Group were fueled by a sense of purpose. "We were pushing a much more kinetic path to get at the bad guys and put scalps on the barn," he said. "It is safe to say a large part of our regiment did the same thing until about 2009, 2010. There were more Taliban than we started, and we lost our way."

When Lt. Col. Mann came home, he found it hard to shed that purpose and to readjust to civilian life. He spent a few years in a dark place. "What I found in my own transition is I became dark after a couple of years, and it was only through learning to tell my story, my hero’s journey I guess, that I started to reconnect with my purpose and find my way home." During an improv class about two years ago, Scott was given the assignment to talk for 5 minutes on the subject of grief. At the end of the 5 minutes, with the whole class was in tears, the teacher (a professional playwright himself) remarked that this was the beginning of a powerful play. Scott and his teacher spent the next 2 years crafting the story that is now a play, Last Out- Elegy of a Green Beret.

When Lt. Col. Mann came home, he found it hard to shed that purpose and to readjust to civilian life. He spent a few years in a dark place. "What I found in my own transition is I became dark after a couple of years, and it was only through learning to tell my story, my hero’s journey I guess, that I started to reconnect with my purpose and find my way home." During an improv class about two years ago, Scott was given the assignment to talk for 5 minutes on the subject of grief. At the end of the 5 minutes, with the whole class was in tears, the teacher (a professional playwright himself) remarked that this was the beginning of a powerful play. Scott and his teacher spent the next 2 years crafting the story that is now a play, Last Out- Elegy of a Green Beret.Underwritten by my firm, the play debuted last year in Tampa, FL on Veterans Day and is now on a nationwide tour of over 16 cities.

On September 14th and 15th, we are bringing Scott’s play, (click here for a trailer produced by the American Veterans Center) to the Kraine Theater in NYC, with a VIP showing on September 14th at 7 pm, and we are working to bring several key influencers to this performance.

Tickets can be purchased here for $30 with all funds going to The Heroes Journey's mission to help veterans find their voice and tell their story as a powerful tool in overcoming obstacles along the difficult journey from combat to civilian life.

https://lastoutpreviewnyc.eventbrite.com

Click here for an interview of Scott Mann on Huckabee’s Heroes, and here for a clip featuring a Gold Star family. If you are interested in sponsorship or donating to Last Out, click here.

Published on August 29, 2019 00:00

August 25, 2019

Nicole Conn's "More Beautiful For Having Been Broken" Wins Best Picture at the Los Angeles Independent Film Festival Awards

Congratulations to NicoleConn, Writer/Director and Lissa_Forehan for Picking up BEST PICTURE for "More Beautiful For Having Been Broken" (https://ecs.page.link/t1upv) Los Angeles Independent Film Festival Award!

Published on August 25, 2019 11:51

August 18, 2019

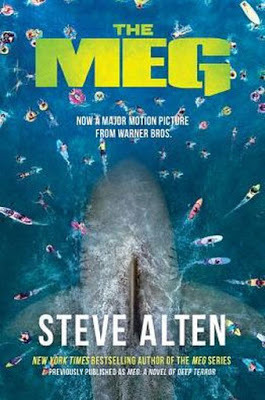

The Meg Review - GET OUT OF THE WATER

What would be better than a 20 foot shark like in the book Jaws

What would be better than a 20 foot shark like in the book Jaws Steve Alten goes one better and writes this novel about the great and terrible 65 foot megalodon - aka

The Meg

I learned about this because of all the hype of the movie release in summer of 2018 starring Jason Statham and Li Bingbing. When I watched the movie, I really enjoyed it! I love a good shark film, probably because my husband is terrified of the ocean and sharks, so I suppose that makes sharks my new best friend! When I learned this was based on a book of the same name, I was pumped because I love delving into stories and getting as much detail as possible which I know movies can never do in their limited time frame. Let’s take a swim into the book!

Book Summary:

Jonas was working with the United States Navy to try and confirm the existence of the megalodon when they ventured into the Mariana Trench in 1997. During this expedition, the Meg surfaces and attacks them so Jonas tries to save everyone by surfacing the vessel, but a few are killed due to this. When explaining to the Navy what he saw, they brushed it off as the ramblings of a madman which causes Jonas to become obsessed for years with proving the existence of the megalodon. This causes tension in his marriage which leads to his wife having an affair with his best friend.

Jonas is approached by Masao Tanaka to help venture into the Mariana Trench in order to retrieve one of their lost submarines, which Jonas immediately accepts as an opportunity to find the Meg and prove he wasn’t crazy. Jonas and Tanaka’s son , DJ, both venture into the trench when DJ is attacked and killed by a male megalodon. As Jonas looks on in horror, a larger megalodon - the Meg - rises from the depths, attacks the male megalodon (#Yasqueen, you don’t need a man boo), and surfaces out of the mariana trench into open waters. Well, it sounds like Jonas can finally prove he wasn’t crazy - as long as he doesn’t get eaten first.

Thus begins the wild shark chase! They hunt and search the ocean as the Meg leaves behind a trail of death. They shoot the Meg with a tranquilizer to try and capture her alive until she wakes up and attacks several bystanders. Jonas drives his submersible into her throat and stomach and cuts through her stomach lining, while inside her, and cuts out the heart. Who else is volunteering to be in the Meg’s stomach? With the Meg finally dead and gone, everyone can finally breathe a sigh of relief - or can they?

Here are the main differences between the book and the movie:

Meg vs. T. Rex

Do you remember the scene in the movie with the T. Rex? Probably not because it was not in the movie at all. The opening sequence of the book is in the late Cretaceous Period, when a T. Rex pursues a herd of dinosaurs and ends up waist deep in the ocean. While there, all of a sudden a huge chunk of his gut is bitten into which confuses the T. Rex until the Meg surfaces and devours the rest of him. Really now - it was no contest. I wish I could have seen the T. Rex swatting his baby arms at the Meg.

The Meg is White in the Book

While in the movie they portrayed the Meg as a giant Great White Shark, in the book the Meg has a bio-luminescent white hide. This is because there is no sunlight in the trench where it has been residing, which only makes it that more menacing looking. Imagine a giant 60 foot long shark all white with charcoal black eyes - I think I just peed my pants a little. The meg also only hunts and surfaces at night in the book due to it’s eye sensitivity to sunlight. This occurs only till the end when it is blinded - then it’s fair game to hunt day or night.

Male and Female Meg Smack Down in Trench

In the movie, there is a scene when they finally killed off the megalodon shark and suspend it on the back of the boat - until the female Meg jumps out of the water, twice as large as the one killed, and bites a huge chunk out of the dead male megalodon. While that was a terrifying site - we actually get to read about the female Meg attacking the male megalodon in the trench right in front of Jonas! I wouldn’t have wanted to get in the middle of that fight. The female Meg being twice the size of the male, not only tears him apart, she actually uses him as a warm bloody shield to escape the trench as it protects her from the extremely cold cloudy barrier that kept her trapped down there all along. Yikes!

Jonas’ Wife Eaten in Shark Cage

In the movie, Jonas is rescuing his ex-wife and her crew from their expedition into the trench. In the book however, Jonas is still married (till death do us part right), even though he does discover his wife is having an affair. She is a popular news reporter and when news of the terrifying Meg surfaces, she decides to go into a shark cage in order to capture videos of the Meg giving birth underwater - read my review on Jaws to see how well it went for Hooper when he did the same. The Meg decides she looks like a tasty snack and attacks the shark cage, swallowing it whole thus killing off Jonas’ wife.

Pregnant Meg

This is the biggest difference from the movie and the book. While in the movie, she is just a lethal shark with a giant destructive appetite, in the book she is actually pregnant and gives birth to 3 megalodon pups. This just takes the book into a whole new level of anxiety because it’s bad enough hunting down one giant 60 foot long shark, but now they have to hunt down 4! While in the end they managed to kill 2 of the pups and the mom… 1 pup was not killed and ends up being the main character in the next book, the Trench. Maybe the movie will mimic this for a sequel due to the success of the movie.

Final Rating & Thoughts: 8/10

I loved loved loved

I loved loved loved The Meg

From the beginning of the book to the end, I was on the edge of my seat wondering how things could possibly get worse until things start to get worse. If a shark could be a villain, I don’t think there is a better one than the Meg herself. She is menacing, terrifying, and will mow down anyone in her way. Even when you notice the characters making dumb decisions by getting in the water, you are rooting for the Meg to show them who’s boss! I loved when they let one of her pups live to set-up for a sequel because I know I definitely needed more megalodons in my life. I also think they did make the Meg seem truly terrifying, at least for me. With it being 60 feet long and albino white, I could only imagine how terrifying that looks charging at you in the water. I actually had nightmares for a while about being chased by the Meg. I won’t be exploring any underwater trenches EVER just in case the Meg really is waiting down there for a moment to shine.

I would have loved to give this book a 10 but there are a few flaws in the book. The way the Meg escaped the trench, in my opinion, was just way too easy. They made it seem like they have been stuck down there for thousands of years but she just randomly ate the right male megalodon that just so happened to cocoon her enough to escape the trench? I am sorry but I’m not buying it. I also didn’t much care for the drama with Jonas and his wife because I really didn’t think it added anything to the story and just set us up to dislike her so when she was eaten, I really wasn’t all that bothered by it. Lastly, I think this is definitely a rip off of it’s inspiration movie: Jaws. The shark attacks, the shark cage, the cheating wife - it just felt like things I read before. Even though

I would have loved to give this book a 10 but there are a few flaws in the book. The way the Meg escaped the trench, in my opinion, was just way too easy. They made it seem like they have been stuck down there for thousands of years but she just randomly ate the right male megalodon that just so happened to cocoon her enough to escape the trench? I am sorry but I’m not buying it. I also didn’t much care for the drama with Jonas and his wife because I really didn’t think it added anything to the story and just set us up to dislike her so when she was eaten, I really wasn’t all that bothered by it. Lastly, I think this is definitely a rip off of it’s inspiration movie: Jaws. The shark attacks, the shark cage, the cheating wife - it just felt like things I read before. Even though The Meg managed to use those same features and make it better, it almost feels like I am reading Jaws 2: Big Daddy.

With that said, I still love this book and would reread it again. It was a really fun and exciting read and they managed to get us to root for the Meg and Jonas at the same time. Maybe if they work out their differences, they could be friends? Even though I felt like this copied Jaws, I still think they did it in a much more entertaining way. For those that read my review on Jaws - you know how I feel on that one. I think The Meg is definitely the best shark book I have ever read. I would recommend this to fellow shark lovers or those looking for an ocean thrill!

For those ready to take a Meg sized bite out of this tale, this is available for purchase on

Amazon in Paperback or via Kindle

Read more

Published on August 18, 2019 00:00

August 16, 2019

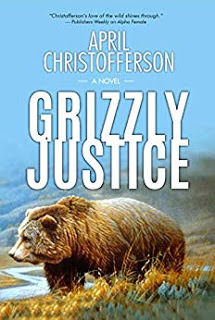

New From Story Merchant Books: Grizzly Justice by April Christofferson

When Yellowstone backcountry ranger Will McCarroll is fired for breaking the rules one time too many, he disappears into the backcountry to continue his decades-long mission of protecting the park’s wildlife. Will is hell bent on saving a wounded grizzly bear whose fate is all but certain: euthanasia.

When Yellowstone backcountry ranger Will McCarroll is fired for breaking the rules one time too many, he disappears into the backcountry to continue his decades-long mission of protecting the park’s wildlife. Will is hell bent on saving a wounded grizzly bear whose fate is all but certain: euthanasia.In his quest, Will stumbles onto a secret meeting of the Alliance, a political movement determined—at any cost—to force the transfer of public lands into state hands. Blackfeet wolverine biologist Johnny Yellow Kidney has taken a forced hiatus from his work in Glacier National Park to head a project born of a high-profile journalist’s loss from a highway tragedy. The goal: to construct safe highway crossings for Montana’s wildlife. Once again, Johnny and Will’s paths cross, not only through both men’s romantic connection to Yellowstone Magistrate Judge Annie Peacock, but also in each man’s race to save the two- and four-leggeds they’ve sworn to protect. Time is running out in Yellowstone Country—and for Will, Johnny, and those they’ve dedicated their careers to defending, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

“A gorgeous book. Grizzly Justice is a riveting read, the majesty and magic of its landscapes and wildlife illuminating every page. I couldn’t put the book down and closed the last page with a deep sense of gratitude for our national parks and profound respect for those who fight to protect them. This book will bring transformational awareness to its readers. It certainly did for me.”

-Ruth Wariner New York Times bestselling author of The Sound of Gravel.

“April Christofferson weaves together her knowledge of the cadences of the natural world, the complexity of behavior that enables injustice, the redemption that passion provides to individual initiative, and the foibles of the human heart.”

-Jeff Hull, bestselling author of Broken Field: A Novel

“Guaranteed to make any reader late for dinner, or even breakfast.”

-Booklist on Clinical Trial

Available on Amazon

Published on August 16, 2019 00:00

August 14, 2019

ETA's ‘Echo Boomers’ Crime-Drama Pic

Patrick Schwarzenegger (Midnight Sun), Gilles Geary (The I-Land) and Hayley Law (Riverdale) are among cast to join Michael Shannon and Alex Pettyfer in feature crime-drama Echo Boomers, which is now under way in Utah.

Based on a true story, the film follows a group of disillusioned twentysomethings who break into and steal from the homes of the rich. Also among cast are Oliver Cooper, Jacob Alexander and Kate Linder.

Seth Savoy is making his directorial debut on the movie which he scripted with Kevin Bernhardt and Jason Miller. Producers are James Langer, Mike D. Ware, Matthew G. Zamias, Lucas Jarach, Byron Wetzel and Sean Kaplan. Nadine de Barros, Jeff Waxman, Frankie Ordoubadi, Eric Brenner and Sandra Siegal are executive producers, as are James Ireland and Alex Pettyfer via their company Dark Dreams Entertainment which is co producing.

Financing is provided by Three Point Capital, with its principals David Gendron and Ali Jazayeri also serving as executive producers. Fortitude International holds foreign rights and launched the project last year at the AFM. CAA Media Finance reps domestic.

Published on August 14, 2019 00:00

August 11, 2019

The History of Plot

The History of Plot

Let’s start from the beginning (the Western beginning, anyway).

PREHISTORY TO 500 BCE: The Creation Story (the Hebrew Bible, Sumerian tablets). How we first started to explain the world, relying mostly on supernatural explanations.

2100–400 BCE: The Epic Poem (the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Iliad). Episodic narratives in which the gods interact with people, with man at the center of the story.

500–400 BCE: Classical Tragedy (The Oresteia, Oedipus the King, Medea). Murder, incest, revenge, and the tragic flaw. Aristotle wrote in Poetics that they ideally preserved “the three unities” — of action (one story), time (one day), and place (one location).

1350–1450: Framed Vernacular Stories (The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales). With the breakup of Latin and the very beginning of “modern” Europe, writers began compiling often bawdy, irreverent stories under baggy framing devices.

1450–1550: The Chivalric Romance (The Death of Arthur, Amadís de Gaula). A marriage of heroic saga and earthy romance, these were the first stories written mostly in prose.

16TH CENTURY: The Picaresque (Don Quixote). Technically, this loose structure of roving misadventures was born with the anonymous novella Lazarillo de Tormes; Cervantes popularized the style (while also satirizing the chivalric romance).

1590S: Parallel Plots Shakespeare didn’t invent modern drama — or really most of his plots — but he pioneered the practice of moving several stories through the same place and time.

1700–1750: The “True” Novel (Robinson Crusoe, Pamela, Tom Jones). The first fully coherent realist plots — rise, climax, and fall — often pretended to be even realer than they were.

MID-18TH CENTURY: The Comic Metastory (Tristram Shandy, Candide). Satire and experiment predated modern formal play by a couple of centuries.

1764: The Supernatural (Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto).

1813: The Marriage Plot Pride and Prejudice was the Ur–marriage plot — the winding tale of a woman’s road to saying “yes” — but Jane Austen’s entire body of work points to her larger (quite modern) project of capturing (and gently satirizing) the mores of the day.

MID-19TH CENTURY: Urban Social Panorama (Balzac, Dickens, Hugo): Ambition was the primal drive and a core subject of capacious plots that traveled up and down the social strata of industrial cities.

MID-19TH CENTURY: The Detective Story (“The Murders in the Rue Morgue,”The Woman in White). Following Edgar Allan Poe, Wilkie Collins pioneered the mystery genre at novel length, and Arthur Conan Doyle later introduced the procedural with Sherlock Holmes.

1860S–1870S: The Moral-Anguish Plot (Crime and Punishment, Anna Karenina). Two very different thick Russian novels move the realist plot inward.

LATE-19TH CENTURY: Science Fiction (Journey to the Center of the Earth, War of the Worlds). 1910S–1920S: Stream of Consciousness (Ulysses, To the Lighthouse, In Search of Lost Time). A new avant-garde redefined plot as the not-always-linear progress of a mind as it processes the world.

1920S–1930S: Noir (Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler). Hardboiled and noir fiction complicated Agatha Christie’s neat puzzles.

1930S–1940S: Dystopia (Brave New World, 1984). Aldous Huxley and George Orwell helped bring the premises of sci-fi to bear on the question of how the individual interacts with society at its future worst.

1950S: The Fantasy Quest (The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings). The quest goes into worlds never seen before, though they may resemble medieval and ancient folklore.

1960S: Autofiction (Marguerite Duras, Karl Ove Knausgaard). This term for thinly veiled autobiography was only coined decades after Marguerite Duras wroteHiroshima Mon Amour and decades before Knausgaard made it his own.

1967: Modern Folklore (One Hundred Years of Solitude). Jorge Luis Borges and other Latin American writers spent the preceding decades marrying supernatural native folklore to European realism, but Gabriel García Márquez’s best seller made “magical realism” a big thing.

1960S–1970S: Metafiction (Robert Coover,Slaughterhouse-Five, Gravity’s Rainbow). Postmodernism opened plots up to elements that winked at the reader in self-conscious ways.

1984: Cyberpunk(Neuromancer): This subset of sci-fi juxtaposes the picaresque with the dystopian and sets up a world in which technology outpaces society’s ability to cope with it.

~ Sadie Stein

Read more

Let’s start from the beginning (the Western beginning, anyway).

PREHISTORY TO 500 BCE: The Creation Story (the Hebrew Bible, Sumerian tablets). How we first started to explain the world, relying mostly on supernatural explanations.

2100–400 BCE: The Epic Poem (the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Iliad). Episodic narratives in which the gods interact with people, with man at the center of the story.

500–400 BCE: Classical Tragedy (The Oresteia, Oedipus the King, Medea). Murder, incest, revenge, and the tragic flaw. Aristotle wrote in Poetics that they ideally preserved “the three unities” — of action (one story), time (one day), and place (one location).

1350–1450: Framed Vernacular Stories (The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales). With the breakup of Latin and the very beginning of “modern” Europe, writers began compiling often bawdy, irreverent stories under baggy framing devices.

1450–1550: The Chivalric Romance (The Death of Arthur, Amadís de Gaula). A marriage of heroic saga and earthy romance, these were the first stories written mostly in prose.

16TH CENTURY: The Picaresque (Don Quixote). Technically, this loose structure of roving misadventures was born with the anonymous novella Lazarillo de Tormes; Cervantes popularized the style (while also satirizing the chivalric romance).

1590S: Parallel Plots Shakespeare didn’t invent modern drama — or really most of his plots — but he pioneered the practice of moving several stories through the same place and time.

1700–1750: The “True” Novel (Robinson Crusoe, Pamela, Tom Jones). The first fully coherent realist plots — rise, climax, and fall — often pretended to be even realer than they were.

MID-18TH CENTURY: The Comic Metastory (Tristram Shandy, Candide). Satire and experiment predated modern formal play by a couple of centuries.

1764: The Supernatural (Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto).

1813: The Marriage Plot Pride and Prejudice was the Ur–marriage plot — the winding tale of a woman’s road to saying “yes” — but Jane Austen’s entire body of work points to her larger (quite modern) project of capturing (and gently satirizing) the mores of the day.

MID-19TH CENTURY: Urban Social Panorama (Balzac, Dickens, Hugo): Ambition was the primal drive and a core subject of capacious plots that traveled up and down the social strata of industrial cities.

MID-19TH CENTURY: The Detective Story (“The Murders in the Rue Morgue,”The Woman in White). Following Edgar Allan Poe, Wilkie Collins pioneered the mystery genre at novel length, and Arthur Conan Doyle later introduced the procedural with Sherlock Holmes.

1860S–1870S: The Moral-Anguish Plot (Crime and Punishment, Anna Karenina). Two very different thick Russian novels move the realist plot inward.

LATE-19TH CENTURY: Science Fiction (Journey to the Center of the Earth, War of the Worlds). 1910S–1920S: Stream of Consciousness (Ulysses, To the Lighthouse, In Search of Lost Time). A new avant-garde redefined plot as the not-always-linear progress of a mind as it processes the world.

1920S–1930S: Noir (Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler). Hardboiled and noir fiction complicated Agatha Christie’s neat puzzles.

1930S–1940S: Dystopia (Brave New World, 1984). Aldous Huxley and George Orwell helped bring the premises of sci-fi to bear on the question of how the individual interacts with society at its future worst.

1950S: The Fantasy Quest (The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings). The quest goes into worlds never seen before, though they may resemble medieval and ancient folklore.

1960S: Autofiction (Marguerite Duras, Karl Ove Knausgaard). This term for thinly veiled autobiography was only coined decades after Marguerite Duras wroteHiroshima Mon Amour and decades before Knausgaard made it his own.

1967: Modern Folklore (One Hundred Years of Solitude). Jorge Luis Borges and other Latin American writers spent the preceding decades marrying supernatural native folklore to European realism, but Gabriel García Márquez’s best seller made “magical realism” a big thing.

1960S–1970S: Metafiction (Robert Coover,Slaughterhouse-Five, Gravity’s Rainbow). Postmodernism opened plots up to elements that winked at the reader in self-conscious ways.

1984: Cyberpunk(Neuromancer): This subset of sci-fi juxtaposes the picaresque with the dystopian and sets up a world in which technology outpaces society’s ability to cope with it.

~ Sadie Stein

Read more

Published on August 11, 2019 00:00

August 9, 2019

Is It Story That Makes Us Read?

Photo: Bobby Doherty/New York Magazine

Photo: Bobby Doherty/New York MagazineRecite a plot backward and you’ll discover some things. Try it with a classic you haven’t read in years. You remember the green light on the last page of The Great Gatsby, of course, and probably Gatsby’s corpse in the pool a chapter earlier. Do you remember who killed him? It was Wilson, the husband of Tom Buchanan’s lover, Myrtle, who was run over by Gatsby’s car with Daisy at the wheel. It was Tom who told Wilson, a man with a few screws loose, that the car belonged to Gatsby, so you could make a case that Gatsby’s death was all Tom’s fault — that he was the real killer and had plenty of motive. You could also argue that Fitzgerald’s end plot is a shambolic mess heaped on a pile of coincidence, though there’s a beauty to the end of the novel that does express one of its great themes: that Gatsby was a careful man who involved himself with careless people and died as a martyr to their carelessness.

But my point here isn’t to pronounce on that novel’s worthiness. What I mean to get across are the thin traces the plots of even the most memorable, near universally read books can leave in our minds. If a work of fiction has any force to it, we close the book with a head full of images, lines, and emotions.

We’ve gotten to know characters and may think of them the way we think of the heroes and villains of our own lives. That sense of them can stay with us for years, even if we forget their names. A good prose style will stay in our ears the way memorable music does. But there’s something that goes away quickly when we close a book, or the screen goes dark, or the curtain falls: the memory of just what happened, in what order, and why. Plots are ghostly things in our brains. It can be hard to keep a grasp of them even as you’re reading a novel or watching a film or a play. I sometimes fret that I have a better memory of the font certain novels were printed in than the incidents that riveted me as I was reading them.

But it’s plot that keeps us turning pages, even when we feel no sympathy or the opposite of sympathy for a fiction’s characters and animating ideas. Nell Zink has said that when she wanted people to read a book about avian conservation and militant environmental activism, the logical way to do it was to embed those elements in the sex-farce plot of The Wallcreeper. Yet a summary of that novel wouldn’t tell you much about why it’s so good. The late Robert Belknap points out in his study Plots (a work largely devoted to close readings of King Lear and War and Peace) that some argue that the only adequate summary of War and Peace is the text of War and Peace, the implication being that you can never really know the novel unless you memorize the text, something that’s possible with a play but not so with Tolstoy’s masterpieces. Others hold that “the summary of a book is the plot of the book,” since the act of summarizing a plot mimics the way our mind grasps a story as it unfolds. On this view, we are all critics when we read, unconsciously adding emphasis to certain events, flattening out ambiguities, lending our loyalties to some characters over others. Some readers want plots that will sweep them away. Others want to keep their distance and examine plots the way a doctor might look down a patient’s throat. In between is a style of reading that takes temporary possession of a text, creating a new work of art that exists only in the reader’s head.

It was Aristotle who first called plot “the first principle, and, as it were, the soul of a tragedy.” (The elements of less importance for him are character, diction, thought, spectacle, and song.) He was writing about Greek drama, but we can apply his ideas to novels, though he considered narrative works, particularly epic ones, inferior to tragedy. There’s something hostile to the bagginess of the novel in Aristotle’s notion that the best works are those in which nothing can be subtracted without the meaning being lost. A more generous theory of plot arrived about a century ago in Russia. The Formalists Vladimir Propp and Victor Shklovsky held that every work of fiction has a fabula and a syuzhet. The fabula is the set of fictional events related within or implied by the work; the syuzhet is the manner in which the fictional information of the fabula is conveyed to the reader. Together they constitute the plot.

There’s something beautiful to me about the concept of the fabula. Every narrative implies an entire world beyond the confines of the narrative, and another history stretching backward and forward in time forever. Thus books proliferate that enter into other books’ fabula to fill in backstories, portray familiar events from other perspectives, and see characters on to further escapades. Television spinoffs and movie-franchise universes operate within shared fabula, and great care is taken not to violate the illusion of a consistent fictional world. Lots of people, after all, are keeping track.

Theorists of plot tend to think of the concept elastically. If plot is the arrangement of incident, each incident itself is also a plot in miniature. The crucial question is the level of causality linking the incidents — or if not causality, the appearance of design, as in Aristotle’s example of the murderer of Mitys dying when a statue of Mitys falls on him. Paradoxically, he says, tragic wonder is greater when it happens by accident.

Aristotle scorned the epic, but he would have hated television. “Of all plots and actions the episodic are the worst,” he wrote. An episodic structure tends to do away with any causal link between the episodes. It’s a string of plots where all the conditions are reset between episodes, and each character returns to his or her mean. Of course, seriality is something else: an episodic structure nested within larger plot arcs — more a linked chain than a string of beads.

Prestige television inherited this structure from the 19th-century novel. Many are enthralled by this development — novelists like Jonathan Franzen among them — but the parallel development of binge-watching has exposed some of the seams of the serial television drama. Binge-watch Breaking Bad and you’ll notice that Walter and Jesse will often reverse their stances on the meth-cooking business every few hours. What would the writers do with them if they weren’t constantly getting out and then being pulled, or jumping, back in? Even The Sopranos shows its reliance on formula if you watch it quickly enough. Rapid rotation of personnel within Tony’s crew means there’s always some problem capo around whom it’ll take a season for somebody to whack. Aristotle thought a tragedy should unfold over the natural course of a day — so perhaps he would have been a fan of 24.

to put plot in its grave, and tried to replace it with intellectual or aesthetic dazzle, but it always returns zombielike, and suddenly we’re again reading books that end with weddings. “All plots tend to move deathward,” Jack Gladney says in Don DeLillo’s White Noise. “This is the nature of plots.” Of course, a marriage is its own kind of death, the death of the individual in the union of a couple. That’s the sort of death that gives people hope for the future, and it’s a plot’s power to trigger the emotional release — catharsis — that Aristotle values. Tragedy’s power rested in its ability to stir feelings of terror and pity in an audience. Unlike Plato, who thought the emotional manipulations of poets a danger to society, Aristotle saw emotional release as a healthy thing — a way to purge the heart of pity and terror before going to war, where such feelings are a liability.

What sort of feelings do we look for from plots today? On television, it’s been well documented, we’ve watched an era of criminal males enacting power fantasies at a time when patriarchy seems to be waning. I’ve seen a different pattern, another prevailing feeling recently in literature, both in novels I’ve admired and many I’ve detested. The feeling is shame. Many fictions these days are animated by a shameful trauma lurking in the fabula, but typically undisclosed until the reader is half or three-quarters of the way through the work. The strange thing about such shame-inducing secrets is that they exist apart and without a direct causal link to the rest of the fictional events but still exert an overpowering distortionary force on subsequent events: Plots become sand castles washed away in a tide of shame. Jay Gatsby had a shameful secret too — that his fortune was criminal. He wanted to get rich in order to marry Daisy. He ended up a corpse floating in a pool.

By Christian Lorentzen

*A version of this article appears in the August 8, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.

Read more

Published on August 09, 2019 00:00