Kenneth Atchity's Blog, page 73

September 8, 2020

Dealing with your Type-C Creative Mind – 3 Things Writers Do

For all storytellers—novelists, screenwriters, journalists, nonfiction writers, and children’s book writers.

Learn more about One-on-one coaching to help understand a Type-C personality and equip you with practical tools to make yourself more productive and less frustrated with storytelling.

Learn more at www.thewriterslifeline.com

Published on September 08, 2020 12:03

September 4, 2020

Ken's Weekly Book Recommendation: Grizzly Justice by April Christofferson

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

When Yellowstone backcountry ranger Will McCarroll is fired for breaking the rules one time too many, he disappears into the backcountry to continue his decades-long mission of protecting the park’s wildlife. Will is hell bent on saving a wounded grizzly bear whose fate is all but certain: euthanasia.

Published on September 04, 2020 10:00

September 3, 2020

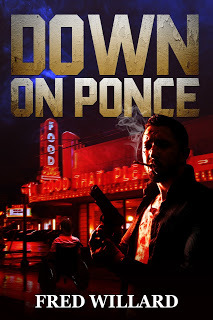

TRULY EXCELLENT WRITING: The Ghosts of Ponce De Leon Park by Fred Willard

Part Three

He woke up in the middle of the night breaking a fever. There was a bright full moon.

"I got to pee bad, man, and I can't move my legs," he said. "I need help getting up.”

Bob didn't answer so he pushed himself up a little bit on an elbow and saw the ground where Bob had been sleeping and had crushed the kudzu, but Bob and his bedroll were gone. Del felt for his money stash and it was gone, too. At least he left one of the pints.

There wasn't nothing he could do but lie there until somebody came along to help. He held the pee as long as he could then wet the bed. It felt uncomfortable as it soaked his pants and ran up his back. He didn't think he could go back to sleep, but that wasn't the worst part. Something much more frightening was happening because time was messing up somehow and he was also back in his parents’ little shack they had rented in West Atlanta when he was nine years old.

"I was thinking about taking the boy to a ball game," his father said.

Del pretended he wasn't paying attention but he hoped his mother would say yes. She was the one who had a job, and she always watched every penny she made. That's what his parents always fought about.

"I guess we ought to do something for him," his mother said. She walked back to her bedroom, where she kept her money, and closed the door so nobody could hear her hiding place. When she came out she handed a couple folded dollar bills to his father, and some change, too.

"Why don't y'all get yourself a hot dog? That way I don't have to cook nothing for you tonight."

She went back to her room and laid down. She worked so much she was always tired. Some days she went to bed as soon as she got home from work.

After a while his father said, "Okay, boy, it's time to go to that ball game."

He followed his father up to the trolley stop, trying to keep up with his funny bobbing walk. They sat on a hard bench for a few minutes till the trolley came.

"Mr. Driver, I need a transfer for me and my boy." He said it like they always did things together.

The driver tore off two scraps of paper, and handed them to him, and then his father made a big to do about handing one to Del.

"Now you hold onto this, Son. It's what makes you able to ride the second trolley."

They both sat down.

"I like this sideways seat the best," his father explained.

"Me too, " Del agreed.

After a few minutes his father pulled the cord that rang the bell and said, "Time to get off."

They were at another bus stop and Del sat on a bench like the other one.

"Now you sit here, till I get back. No matter what happens, just stay there."

He crossed the street and went in a liquor store and when he came out Del could see a bottle stuck in his front pants pocket. When he sat next to Del he took it out, and held it to his lips and swallowed three or four times.

"Here. You want some?"

He handed it to Del who took a sip but thought it tasted sour, like puke. He pretended to like it, though.

"Here comes the bus." His father put the bottle back in his pants.

"They don't like you to drink this stuff on the bus," he father explained.

Once they got on it seemed like they were at a party.

"Anybody going to see the Crackers?" his father asked.

A bunch of people laughed like his father had told a joke.

"Seems like most of us are," a woman said.

"Have a seat, son."

He sat Del down in the sideways seat, then walked back four or five rows to where there was a bunch of men sitting. He said something, they laughed, and a couple of them looked up toward the driver, then the bottle came out and they were passing it around.

Del looked out the window and watched the people on the street until they stopped next to this big brick building with a tower on top like a castle.

"That's the Sears and Roebuck."

A woman sitting next to him said this when she saw him looking at the building.

"Everybody off the bus," his father said. The men with him laughed like this was pretty funny.

People were already starting to line up to buy tickets, so his father ran ahead and bought two seats in the white bleachers. They went up this ramp into the park and he followed his father and the other men under the wooden seats to a refreshment stand where a man was cooking hot dogs on a grill.

Dell asked, "You going to get us some hot dogs, daddy?"

"Don't have no money left," he said. "But wait a minute here. I got something in my pocket."

He reached in his pocket and pulled out his white handkerchief. He bent down on one knee, and laid it out like a neat square, then stepped back and started doing a little dance like a buck and wing and giving out these little yelps.

He was pretty good at it, but Del didn't like to watch.

Pretty soon a crowd had gathered and people were dropping nickels and dimes, even a few quarters on the handkerchief.

"Thank you very much, folks." his father said. He scooped up the money and handed Del a quarter.

"You keep this in case you need it. Don't spend it on food or nothing. Just hold onto it. Now go on up and get us our seats and I'll be along in a little while."

The men from the bus had gathered around his father again and Del knew he wanted to drink with them, so he went to get their seats in the bleachers. A boy his own age tried to sit down next to him, but he held his hand out over the seat and said, "My daddy's going to be sitting there," so the boy moved over a space.

Pretty soon the teams took to the field and everybody cheered. Del didn't know much that was going on but he acted like he did, so nobody would think he was stupid. He didn't know how to play ball. His parents moved around so he never really got to have many friends and the few boys he knew didn't have the equipment. Still, it was real beautiful to watch. The lights made the field seem bright green and the uniforms stuck out like a cartoon in the newspaper. Out in the distance there was this dirt bank covered with kudzu and a big magnolia tree and over to the right, a railroad track. It didn't look like how he'd imagined a ballpark, but he liked it.

He actually started figuring out the game, at least part of it, and he'd get excited with every pitch, and cheer with the crowd when the players from Birmingham would swing at a pitch and miss.

He was having fun until he figured out that his father wasn't coming to his seat, and then he only watched the game because he knew he ought to be having fun since he probably wasn't going to get to come back.

The Crackers won. As the crowd left, he didn't see his father and he knew he wasn't here. In his pocket, he felt the quarter and wondered if this was the time he was supposed to save the money for, or if there would be another one. Finally he decided this must be the time, because spending it was the only way he was going to get home.

"I'd like a transfer, Mr. Driver." he said

The man gave him a funny look, but handed him the transfer.

Del was pretty sure he could spot the street where he lived, but he wasn't too sure about the stop by the liquor store, so he sat in the sideways seat twisted around with his face pressed against the window. It turned out to be easy to see because of the lights, so he rang the bell and got off the trolley.

He was quiet going in the house. He was starving and got a piece of bread. He hoped his mother wouldn't notice and get mad.

"That you boy?” she called from the bedroom.

"Yes ma'am."

"Is your father with you?"

"No ma'am, he ain't."

"I should have known," she said. "He don't care nothing about you. He just wanted the money so he could get a drink."

"He won't be coming back neither," she said. "I told him the next time he took to drinking he couldn't come back, but sometimes that man needs a drink so bad he'd trade his whole life for it."

A Note From the Editor

There is, in every city of some size, "a street of appetites" — a place where people with hungers congregate, a street where things happen in dark places. In Atlanta, The Bitter Southerner’s hometown, that street has always been Ponce de Leon Avenue. Ponce, as we call it, is home to the legendary Clermont Lounge, where strippers whose average age is 46.5 shake their moneymakers, and the Majestic Diner, which has been serving hangover prevention and cures 24/7 since 1929. Ponce always begs to be the setting of a novel. Back in 1997, an Atlanta writer named Fred Willard delivered a great one. “Down on Ponce” was hard-boiled crime fiction, solidly in the tradition of Raymond Chandler and Jim Thompson. “Down on Ponce” permanently planted itself in my brain. I was 36 years old when it came out, and I’ve gone back to reread it several times. For a guy like me, who loves crime fiction written with verve and feistiness, “Down on Ponce” was just the ticket, particularly because I knew its setting like the back of my hand. But in the last decade or so, the literary world hasn't seen much of Fred Willard's work. Then a few weeks ago, out of the blue, Willard sent The Bitter Southerner a short story. This made me a happy guy — happier still because his story is set once again on Ponce, Atlanta's “street of appetites,” as Willard so aptly describes it here. You'll experience two Ponces in this story. One is the Ponce of the 1990s, when the kudzu-shrouded, long-unused railroad tracks that bisect the street were still the home of much nefarious activity. Today, those tracks are a pedestrian trail called the BeltLine. The other is the Ponce of the mid-20th century, when the Negro League Atlanta Black Crackers and the minor-league Atlanta Crackers shared Ponce de Leon Park, an old baseball field now long gone. Today, a Whole Foods sits about where center field was. A crime does occur in this story, and the writing is as blunt as the best crime fiction, but in “The Ghosts of Ponce de Leon Park,” Willard is now exploring different characters with different hungers — the homeless. We meet Bob and Del soon after they arrive in Atlanta, having come to the city after Del “just wore out my welcome too many places” in Nashville. Speaking of welcomes, we’re happy to welcome one of our favorites, Fred Willard, to the pages of The Bitter Southerner. — Chuck Reece

Repost from the Bitter Southerner

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

Published on September 03, 2020 00:00

September 2, 2020

August 31, 2020

Dealing with your Type-C Creative Mind – Creative or Crazy?

For all storytellers—novelists, screenwriters, journalists, nonfiction writers, and children’s book writers. Learn more about One-on-one coaching to help understand a Type-C personality and equip you with practical tools to make yourself more productive and less frustrated with storytelling.

Learn more: http://www.thewriterslifeline.com/

Published on August 31, 2020 12:10

August 29, 2020

Dr. Meg Van Deusen Speaks with Jim Oliver on his Dancing with Grief Podcast

Our ability to create secure attachments to other people increases our resilience to stress, but our current American culture is creating barriers, not pathways, to human trust and closeness.

Jim Oliver sat down and had a chat with Dr. Meg Van Deusen about her insights regarding Stress in the US and how our stress levels are increasing while our interpersonal connections are decreasing.

In this insightful interview with Dr. Meg Van Deusen, we discuss topics such as:

• What is stress?

• What are different types of stress?

• What are some things that create stress?

• How does stress impact our lives?

• What can you do to cope with stress and loneliness?

In a time of great stress and disconnection in the U.S., she offers insights and solutions to help readers reconnect and live healthier lives.

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

Published on August 29, 2020 00:00

August 28, 2020

Ken's Weekly Book Recommendation: The Trial by Larry D. Thompson

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

A classic David-and-Goliath tale of a small-town lawyer fighting the incestuous relationship of a giant pharmaceutical company with the FDA. In this fast-moving legal thriller.

Published on August 28, 2020 10:00

August 26, 2020

Story Merchant Film Closet: Superheros

Published on August 26, 2020 00:00

August 25, 2020

TRULY EXCELLENT WRITING: The Ghosts of Ponce De Leon Park by Fred Willard

Part Two

When it came down to it, Del didn't know jack-shit about Bob. He thought Bob could just as easy take off with the money and not come back, buy himself a decent dinner and keep all the wine for himself. He had the look of someone who knew how to take care of himself, all right. His jeans, work shirt and heavy shoes were a lot newer than Del’s, whose clothes looked like they were about to rot off. Not that he cared anymore, but Del thought they smelled like it too.

At the shelter in Nashville, Bob had got hung with the name Normal Bob. He wasn't so damn normal, but he had the good luck to show up after Crazy Bob who got his instructions from a dog named Tick that nobody else could see. Mostly the dog told him to howl. So Bob became Normal Bob to tell him apart from Crazy Bob.

Normal Bob was going back to Atlanta so Del planned to tag along. Del had a little stash of money and Normal knew the city so it seemed like a good partnership.

Del laid out in his bedroll and put his head on his little bag of clothes and watched the puffy white clouds drift across the early evening sky. In a little while, the night would unzip its bag of tricks and spill the predators into the hundreds of pockets of darkness along this street of appetites, and by then Del hoped to be fed, drunk and sleeping unnoticed among the weeds.

Now that he'd got the weight off his legs, he noticed he was getting the shakes in his hands, but there wasn't nothing he could do about it till Bob got back with the wine. He lay like this about an hour, till twilight, when he heard a man approaching, looked up and saw Bob carrying a couple of sacks.

"I got us both a Chubby Decker Plate."

He handed Del a pint bottle. Del broke the seal, and took three or four gulps, and fought to keep them down. He didn't want to waste any of it.

"You going to eat anything with that?" Bob asked.

"First things first," Del said.

"You shouldn't have made this trip. It was too much for you," Bob said.

"Had to leave Nashville."

"It must have been big trouble," Bob said.

"No, I just wore out my welcome too many places. Life was getting too hard."

"Well, a lot of little trouble can be just as bad as big trouble," Bob said. "Tomorrow morning we can head up to St. Luke’s for breakfast. Talk to the guys there. See what's going on."

"I don't know if I can make it," Del said. "I don't think I'm going to be able to walk at all."

"I can call the Grady wagon then, they can take you to the hospital."

“I'm afraid they might have to cut my legs off."

Bob tried to change the subject.

"This place we're sitting is historic. It's the back end of the old Ponce de Leon Baseball Park. That magnolia tree would have been at dead center field. The Atlanta Crackers used to play here. I came to the games with my old man. They tore the place down when they built the new stadium for the Braves. Turned it into this parking lot."

"I never liked this place none," Del said.

"You been here then?"

"I lived in Atlanta a couple months when I was a kid. I came here with my father once," Del said. "What do they call that building across the street?"

"That would be the old Sears and Roebuck. It's got city offices now, so they call it City Hall East."

"I remember the Sears and Roebuck, you got of the trolley and walked across the street to the park."

"That's right, man, they still had the old electric trolleys when the Crackers played here."

"I never had no luck here. We shouldn't have stopped here."

"Hell, you were the one who wanted to stop, Del. You said your legs were bad. You never should have left Nashville with your legs like that."

"I know that, now," Del said. The memory of the old ball park pinned him to the ground like a stack of cement blocks on his chest.

A Note From the Editor

There is, in every city of some size, "a street of appetites" — a place where people with hungers congregate, a street where things happen in dark places. In Atlanta, The Bitter Southerner’s hometown, that street has always been Ponce de Leon Avenue. Ponce, as we call it, is home to the legendary Clermont Lounge, where strippers whose average age is 46.5 shake their moneymakers, and the Majestic Diner, which has been serving hangover prevention and cures 24/7 since 1929. Ponce always begs to be the setting of a novel. Back in 1997, an Atlanta writer named Fred Willard delivered a great one. “Down on Ponce” was hard-boiled crime fiction, solidly in the tradition of Raymond Chandler and Jim Thompson. “Down on Ponce” permanently planted itself in my brain. I was 36 years old when it came out, and I’ve gone back to reread it several times. For a guy like me, who loves crime fiction written with verve and feistiness, “Down on Ponce” was just the ticket, particularly because I knew its setting like the back of my hand. But in the last decade or so, the literary world hasn't seen much of Fred Willard's work. Then a few weeks ago, out of the blue, Willard sent The Bitter Southerner a short story. This made me a happy guy — happier still because his story is set once again on Ponce, Atlanta's “street of appetites,” as Willard so aptly describes it here. You'll experience two Ponces in this story. One is the Ponce of the 1990s, when the kudzu-shrouded, long-unused railroad tracks that bisect the street were still the home of much nefarious activity. Today, those tracks are a pedestrian trail called the BeltLine. The other is the Ponce of the mid-20th century, when the Negro League Atlanta Black Crackers and the minor-league Atlanta Crackers shared Ponce de Leon Park, an old baseball field now long gone. Today, a Whole Foods sits about where center field was. A crime does occur in this story, and the writing is as blunt as the best crime fiction, but in “The Ghosts of Ponce de Leon Park,” Willard is now exploring different characters with different hungers — the homeless. We meet Bob and Del soon after they arrive in Atlanta, having come to the city after Del “just wore out my welcome too many places” in Nashville. Speaking of welcomes, we’re happy to welcome one of our favorites, Fred Willard, to the pages of The Bitter Southerner. — Chuck Reece

Repost from the Bitter Southerner

AVAILABLE ON AMAZON

Published on August 25, 2020 00:00

August 24, 2020

Getting Your Story Straight: Intensity Chart

Professional coaching tips to help you figure out point of view, structure, and master all the elements of story. Learn more: http://www.thewriterslifeline.com/

Published on August 24, 2020 13:07