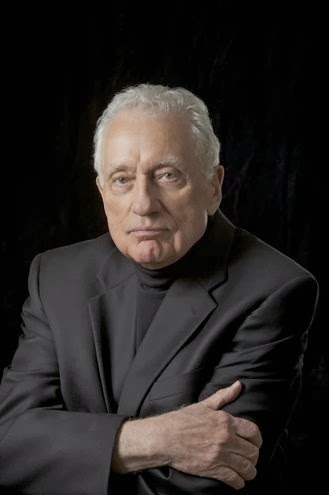

Kenneth Atchity's Blog, page 196

October 23, 2013

CONGRATULATIONS to Atchity-Wong Client Alan Roth - Nicholl Fellowship in Screenwriting Winner!

Academy Reveals Nicholl Fellowship in Screenwriting Winners

The $35,000 prizes will be presented at a

Nov. 7 event, which will include readings from the chosen screenplays

directed by Rodrigo Garcia.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has awarded Nicholl Fellowships in Screenwriting to four individual writers and one writing team.

our editor recommends

Academy Names 11 Finalists for Nicholl Fellowships

The winners, listed alphabetically by author, are Frank DeJohn & David Alton Hedges, Santa Ynez, Ca., for their screenplay Legion; Patty Jones, Vancouver, B.C., Canada, for Joe Banks; Alan Roth, Suffern, N.Y., for Jersey City Story; Stephanie Shannon, Los Angeles, for Queen of Hearts; and Barbara Stepansky, Burbank, Ca., for Sugar in My Veins.

Each winner will receive a $35,000 prize, the first installment of which will be distributed at an awards presentation on Nov. 7 at the Academy’s Samuel Goldwyn Theater in Beverly Hills. For the first time, the event also will feature a live read of selected scenes from the fellows’ winning scripts. Rodrigo Garcia is directing the event, which will include members of the actors’ branch and which will be produced by Julie Lynn and supported by Lexus.

The winners were selected from a record 7,251 scripts that were submitted.

Fellowships are awarded with the understanding that the recipients will each complete a feature-length screenplay during their fellowship year. The Academy acquires no rights to the works of Nicholl fellows and does not involve itself commercially in any way with their completed scripts.

The Academy Nicholl Fellowships Committee, chaired by producer Gale Anne Hurd, is composed of writers Naomi Foner, Daniel Petrie Jr., Tom Rickman, Eric Roth, Dana Stevens and Robin Swicord; actor Eva Marie Saint; cinematographer John Bailey; costume designer Vicki Sanchez; producers Peter Samuelson and Robert W. Shapiro; marketing executive Buffy Shutt; and agent Ronald R. Mardigian.

Published on October 23, 2013 00:00

October 22, 2013

Story Merchant Newsletter

Published on October 22, 2013 15:41

Story Merchant Newsletter

Published on October 22, 2013 15:41

October 21, 2013

November 7th Fundraiser will feature former Secret Service agent

Clint Hill was in car behind JFK's limo during assassination

By

Tom Vogt, Columbian

science, military history reporter

Clint Hill, left, and other Secret Service agents who guarded

President Kennedy on the day of his assassination leave during a break

in the 1964 presidential commission's investigation.

A former Secret Service agent who was in the Dallas motorcade when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated will headline a Nov. 8 fund-raising luncheon in Vancouver.

Clint Hill, who was assigned to first lady Jacqueline Kennedy's security detail, will be the featured speaker in an 11:30 a.m. benefit for CDM Services at the Hilton Vancouver Washington.

He will be joined by Lisa McCubbin, co-author of a book about Hill's time with the first family, "Mrs. Kennedy and Me."

Hill was riding in the car behind the presidential limousine on Nov. 22, 1963. After the president was shot, Hill jumped onto the back of the limousine and placed his body above the president and Mrs. Kennedy.

McCubbin met Hill several years ago when she and another writer collaborated on a book about Kennedy's Secret Service detail. McCubbin convinced Hill that his story deserved a book of its own, resulting in "Mrs. Kennedy and Me."

Hill and McCubbin also have a new book, "Five Days in November," which will be released as the world looks back on the 50th anniversary of Kennedy's death. The new book will

be available ahead of its official public release, and a book signing will follow the luncheon.

According to a news release, the book tells "how a Secret Service agent who started life in a North Dakota orphanage became the most trusted man in the life of the most captivating First Lady of our time."

The Nov. 8 luncheon is part of a two-day fundraising effort to support CDM Services, which assists veterans, seniors, families and children with in-home care.

On Nov. 7, Hill and McCubbin will take part in a 5:30 p.m. reception hosted by the Al Angelo Company at 400 E. Mill Plain Blvd.

Both events will feature auctions of archive photographs of members of the Kennedy family, including news photos acquired from media organizations.

This is the third in an series of annual "Symbol of Freedom" events to raise money for CDM Services. In addition to helping with in-home care, CDM Services operates an adult day health center that provides rehabilitation, socialization and meals.

Published on October 21, 2013 00:00

October 19, 2013

Screenwriting Advice, in Six Seconds or Less

The first Oscar for Best Original Screenwriting, awarded during a brisk fifteen-minute ceremony that took place over the clinking sounds of dinner in the Blossom Room of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel in 1929, went to Ben Hecht, though he very nearly did not win. Hecht, then thirty-five years old, won for “Underworld,” the first screen story he wrote after arriving in Hollywood from New York. Hecht’s eighteen-page treatment for the silent gangster film was populated with the sort of nefarious, grimy characters he once reported on for the metro desk of the Chicago Daily News. He wrote the story in defiance of traditional Hollywood tropes—his “Underworld” contained no heroes, just villains. If Hecht had learned anything as a newsman, it was that crime and gore sell more papers than virtue. Hecht was appalled, then, to learn that the director, Josef von Sternberg, had injected a dose of sentimentality by showing a mobster give charity to a beggar after robbing a bank. “You poor ham,” Hecht wrote to Sternberg in a telegram. “Take my name off the film.” His name stayed.

Hecht stayed, too, despite his ire at the system, becoming one of the most prolific screenwriters in town—and the highest paid. (His ability to churn out witty, fast-moving scripts in as little as two weeks, and never more than eight, is now legend; he is often called the “Shakespeare of Hollywood.”) But Hecht never really got comfortable. The man who wrote “His Girl Friday,” “Some Like it Hot,” “Scarface,” and “Notorious,” who became a favorite of Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, and David O. Selznick, hated Los Angeles. Or, rather, he hated what Los Angeles was doing to his brain. He used his show-business earnings to buy time away from show business—he spent the months he was not beholden to studio moguls in his native New York, writing novels, plays, essays, his serious work.

In 1954, ten years before he died, Hecht published his memoir, “A Child of the Century,” to wide acclaim from the New York literary establishment, a reception that likely meant far more to him than the Academy Award. In it, he savaged the industry that had given him a living. “A movie is never any better than the stupidest man connected with it,” he wrote. “Out of the thousand writers huffing and puffing through movieland there are scarcely fifty men and women of wit and talent … Yet, in a curious way, there is not much difference between the product of a good writer and a bad one. They both have to toe the same mark.”

Hecht recalled that most of his time as a screenwriter was spent sitting in a producer’s office wondering why he had to rewrite his best bits: “Why must I strip the hero of his few semi-intelligent remarks and why must I tack on a corny ending that makes the stomach shudder? Half of all the movie writers argue in this fashion. The other half writhe in silence, and the psychoanalyst’s couch or the liquor bottle claim them both.”

The historian David Thomson wrote that Hecht died, along with his friend and “Citizen Kane” co-writer Herman Mankciewitz, “morose and frustrated. Neither of them had written the great books they believed possible.” Theirs isn’t a unique story, at least in the studio-system era. Hollywood screenwriting was, in its early years, a profession populated by unhappy Eastern writers searching for a big paycheck out West and finding California deprived of intellect—a folly and a punch line.

But things have changed. Screenwriting has become a desirable outlet for artists, detached from the gruelling contract work of the big studios. Being a screenwriter is, today, deeply connected to a love of film and television (in the early days, they didn’t know yet to fully love it), and is no longer an occupation that serious writers merely deign to do. Instead, many dream of doing it, and that dream has become an entire industry. Whereas Hecht paid his fortunes to leave, many pay theirs to learn how to stay.

Ben Hecht is the first person that Brian Koppelman mentions to me when I visit him at his office, right off Central Park on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. The office, which he shares with a partner, is on the top floor of a brownstone, above a private bridge club that seems like a remnant of the Gilded Age, with its own dining room and white-napkin service. To get to Koppelman, one must take a rickety elevator with a cage door to the top floor, and climb one more flight of stairs, which open onto a decidedly modern space that could be anywhere in Los Angeles—a big oak conference-room table, framed movie posters, chunky scripts stacked at casual angles.

It’s easy to see why Koppelman cites Hecht as a spiritual writing mentor—he, too, got his start in his thirties (he is now forty-seven), and chooses to stay as far away from the slick Hollywood machine as possible when he’s not in production. He’s a plaid-shirt-and-jeans kind of guy. And, yet, Koppelman does not disdain the act of screenwriting, or feel that it has caused his brain to atrophy. He is proud of what he has done—he has written several studio films, including “Rounders,” “Oceans Thirteen,” and, most recently, the Ben Affleck vehicle “Runner, Runner”—and he does not plan to one day abandon screenwriting for some higher literary goal.

What he hates, he tells me, channelling Hecht’s twilight slash-and-burn attitude toward the business, is the industry that surrounds screenwriting, the world of how-to books and motivational retreats that cinch the craft like a belt. He hates the gurus, the seminars, the “For Dummies” guides that tell aspirants how to churn out popcorn hits. “If Ben Hecht woke up in a screenwriting genre seminar being taught in a conference room at the Radisson, I think he would puke all over everybody,” Koppelman says, with a boyish grin. “I mean, I have friends who do that, and I don’t want to sound like a jerk! But I think that, somehow, screenwriting became this golden cash cow that everyone wants a part of, and then, on top of that, the industry creates the feeling in people that there is some mystery to doing this work, and so in the end it can very easily prey on dreamers.”

Last month, Koppelman allowed these observations to bubble over into a side project, a series of short, forceful videos about screenwriting and the perils of the industry which have quickly gone viral online. He calls them Six-Second Screenwriting Lessons. Koppelman records his thoughts in tiny snippets using Vine, a social-media app that can record six seconds of video that play on a loop. As of this writing, he has made thirty-eight of them, posted almost daily, with thousands of likes, shares, and retweets. Koppelman records his lessons on the fly, usually while walking around New York, the city rushing by in the background. They are not formal or planned. He usually shoots in extreme close-up, with few blinks. His voice has the no-nonsense tone that some might describe as “real talk.”

Because of their short length and repetitive looping, his statements can take on the quality of zen koans, little mantras one might chant into belief. In Koppelman’s case, that belief is that the screenwriting-education industry is essentially fraudulent and confining, that good stories are personal and cannot be taught, and that learning how to write a script from a book is like learning how to build a rocket from a V.C.R. manual.

“For starters, what I am doing is not precious,” he says. “Vine allows me to make something disposable for free. I’m not renting out a conference room in some hotel and asking you to pay five grand to hear me speak. I’m not a gatekeeper, I don’t want to sell you anything. I just struggle every day to live in this business without cynicism, and I wanted to share that. And, suddenly, Vine came along, and it felt like a natural thing to do. The first one was an experiment, and then people seemed to really feel a desire for more. So I’m just going to keep at this.”

Koppelman’s statements on Vine are not complex. They are straightforward, simple, and affirmational, like something a quarterback might yell right before breaking the huddle:

Lesson No. 1: “All screenwriting books are bullshit, ALL. Watch movies, read screenplays, let them be your guide.”

Lesson No. 14: “Forget about contests, agents; focus on what you can control. Words, pages, and the intention behind them.”

Lesson No. 25: “When I’m stuck on a first draft, I remind myself that no one gets to see this until I say they can, which gives me permission to finish.”

Lesson No. 37: “Don’t stress about making your main characters likable or relatable. That’s development speak. Just make them fascinating, and we’ll care.”

The irony of Koppelman’s complaint, of course, is that any success that he enjoys with his mantras—and, so far, several celebrities and big-name writers, including Seth Meyers and Ed Norton, have endorsed the videos—spikes interest in Koppelman as a new kind of guru, the very kind of screenwriting-secrets-keeper that he wants to dethrone. “I’ve been asked to do a book of these things,” he says, “Or to write for some industry sites. And why would I do that? It’s hard to say, Don’t listen to anybody in this business, follow your heart and your truth, but in a public way. Because then, of course, you are sort of saying, Listen to me.”

Koppelman is big on the word “truth”—he uses it often on Vine, telling his viewers to focus inward, tell a true story, start from a truthful place. He feels, like many observers of the business, that Hollywood’s shift toward mega-franchises (and an increased reliance on foreign audiences) has led to less authentic storytelling. “And this is what I want people to get out of it,” he says. “That writing is scary, but much less scary when you do it with authentic intentions.”

“I’ve seen so many people sitting at coffee shops in L.A. reading ‘Save the Cat’ or Robert McKee’s ‘Story,’ ” he says, “And those are classic books. But they make you think only one thing is commercial, and commerce creates barriers. They think this writing is about cracking the code. My entire mission here is to say that, if you think there is a code to begin with, then you’ll never really create much of value.”

Screenwriting is a tricky medium. In its early days, writers were contract workers, word monkeys for the studios, and even the highest paid and most independent practitioners felt hamstrung by the churning maw of the studio system. The focus was on fast copy and snappy dialogue, low on intellectual challenge and high on action. Screenwriting, even now, rarely happens in a vacuum—there are producers’ notes, directors’ notes, executive notes, actor contributions. Unless the screenwriter is also the director, their work is the kind of writing over which they have the least possible control; a script is a pie with a hundred thumbs in it. So, naturally, it was not a medium that was initially given high regard by those who took writing seriously. It was a medium to fill the pocketbook. When Herman Mankiewicz lured Hecht to Hollywood, he sent a telegram that said, “Millions are to be grabbed out here and the only competition is idiots. Don’t let this get around.” It got around.

What screenwriting tends to offer the writer who is not an auteur is money, and a great deal of it. Koppelman says that he feels the economics of the profession—the branch of writing that promises riches far greater than fiction or poetry or even journalism—cause challenging, creative ideas to fester, or, worse, never make it to the page. He mentions a handful of writer-directors, like Woody Allen and Nicole Holofcener, who manage to overcome these obstacles, but says that quality screenwriting is a cause that continues to need firebrands.

“Look, if someone decides to sit down at a keyboard and tell the truth using this medium, then we are brothers and sisters. Those are my kindred spirits. But you can’t believe how many people start screenplays with calculations about what they think Hollywood wants, and that makes boring movies. If I can get one person to stop doing that with these Vine lessons, then I think the whole industry will be better for it.”

Koppelman’s Vines (along with wildly popular screenwriting-advice sites like the one by John August) occupy a strange writer-empowerment territory that has grown up on the Web, places where seasoned practitioners of the form try to assert to their followers that there is an art to what they do, and that the art can be gradually decoded. Perhaps discussing the work this way at all, in mantras or books or seminars, zaps the art from it—many independent auteurs already understand that the best way to work around the confines of the studios is simply not to write for them, that trying to learn the secrets of writing a blockbuster is in some way admitting that commerce does, in the end, matter as much as creativity. But Koppelman feels that the need for someone to do what he’s doing on Vine far outweighs the drawbacks. Every video he posts is met with people who are “grateful just to hear that someone else out there struggles, and wants it so bad, and has found a path through.”

“Screenwriting is like any other writing,” he says. “It’s lonely. It’s just you and a page. I am doing this for the people who stare at that page in fear. That was me for so long.” Film scribes don’t have to end up on the psychoanalyst’s couch or defeated by an industry that began by not valuing the writer. Koppelman, unlike Hecht, believes that screenwriting can be a writer’s most serious work. “Times have changed, and writers can run things,” he says. “But only if they are writing something honest and true and present. That’s really all I’m here to say.”

Reposted From The New Yorker

Published on October 19, 2013 00:00

October 18, 2013

Guest Post: 10 Mistakes Authors Make that Cost a Fortune (and how to avoid them) by Penny C. Sansevieri

When it comes to books, promotion, and book production I know that it can sometimes feel like a minefield of choices. And while I can't address each of these in detail, there are a number of areas that are keenly tied to a book's success (or lack thereof). Here are ten for you to consider:

1. Not Understanding the Importance of a Book Cover

I always find it interesting that authors will sometimes spend years writing their books and then leave the cover design to someone who either isn't a designer, or doesn't have a working knowledge of book design or the publishing industry. Or, worse, they create a design without having done the proper market research. Consider these facts for a minute: shoppers in a bookstore spend an average of 8 seconds looking at the front cover of a book and 15 seconds looking at the back before deciding whether to buy it. Further, a survey of booksellers showed that 75% of them found the book cover to be the most important element of the book. Also, sales teams at book distribution often only take the book cover with them when they shop titles into stores. And finally, please don't attempt to design your own book cover. Much like cutting your own hair this is never a good idea.

2. Sometimes You Get What You Pay For

There's an old saying that goes: You can find a cheap lawyer and a good lawyer, but you can't find a good lawyer who is cheap. Though this is a very different market, it's kind of the same thing. Yes, there are deals out there and that's not to say that you have to pay a good publicity person tens of thousands of dollars, but if you find someone who's willing to market you for $200 or something like that, I'd be asking questions about what you get for your money because while $200 dollars isn't much, it's $200 here and $99 there and eventually, it all adds up. So if a deal seems too good to be true, make sure that you're getting all the facts. Just because they aren't charging you a lot doesn't mean they shouldn't put it in writing. And by in writing I mean you should get a detailed list of deliverables. Finding a deal isn't a bad thing, but if you're not careful it might just be a waste of money so ask good questions before you buy.

3. Listening to People Who Aren't Experts

When you ask someone's opinion about your book, direction, or topic, make sure they are either working in your industry or know your consumer. If, for example, you have written a young adult (YA) book, don't give it to your co-workers to read and get feedback (yes, I know some YA books have adult market crossover appeal but this is different). If you've written a book for teens, then give it to teens to read. Same is true for self-help, diet, romance. Align yourself with your market. You want the book to be right for the reader, in the end that's all that matters.

4. Hope is Not a Marketing Plan

I love hope. Hope is a wonderful thing, but one thing it isn't is a marketing plan. Hoping that something will happen is one thing, but leaving your marketing to "fate" is quite another. Even though you wrote the book, even though you toiled hours making it perfect and even though you feel that you have enough people you know who will buy it and/or recommend it to friends, you still have to market it. More often than not authors tell me that they can't seem to get family or friends to buy their book. I know that sounds odd but it's true and even if they do, that's what? One hundred copies at the most? While family and friends do want to help, you shouldn't bank on them for success. So when it comes time to get your book out there, you need to have a solid plan in place or at the very least a set of actions you feel comfortable working on. Waiting on a miracle, a sale, or a sign from above will cost you a lot in terms of book aging. Once your book is past a certain "age" it gets harder and harder to get it reviewed so don't sit idly by and hope for something to happen. Make it happen. A book is not the field of dreams, just because you wrote it doesn't mean readers will beat a path to your door.

5. Work it, or Not

There's a real fallacy that exists in publishing and it's this: "instant bestseller." Anyone who has spent any amount of time in the industry knows there is no such thing as "instant" and certainly the words "overnight success" are generally not reserved for books. There is also the belief that a "miracle" will just happen to you when you publish. Personally I love miracles but they tend to not happen with books, sadly. Book promotion should be viewed as a long runway. Meaning that you should plan for the long term. Don't spend all your marketing dollars in the first few months of a campaign, make sure you have enough money or personal momentum to keep it going Whether or not you hire a firm you must "work it" - meaning working your marketing plan, working your goals, whatever. Publishing is a business. You'd never open up a store and then just sit around hoping people show up to buy your stuff. You advertise, you run specials, you pitch yourself to local media. You work it. But what does "working it" mean? Well, it means that if you have a full-time job you find time each week to push the book in some form or fashion. You find time, you make time. You should be engaged in your own success, even if you hire someone to do this for you, you should still be involved. Sometimes it doesn't take much, but it does take a consistent effort, whatever that is. I have a friend who is losing weight. She's lost 19 pounds over three months. Maybe that seems like pretty slow weight loss, right? I mean who wants to wait three months for a measly 19 pounds? Still, she's ahead, she's doing little things that make a big difference. Time will pass anyway. How will you use it?

6. Not Understanding Timing

While timing in publishing has essentially become obsolete, things like advanced reviews, advanced pitching and early sales into bookstores aren't the be-all-end-all they once were. Still, timing is important. While it's true that sometimes older books can see a surge of success it's not the rule. You'll want to be prepared with your marketing early. In fact, you should have a plan in place months before the book is out. That doesn't mean that you're sending 200 review copies out, that just means you have your ducks in a row so to speak and you know what your plan will be. Also, timing can affect things like book events (especially if you're trying to get into bookstores). Understand when you should pitch your book for review, start to get to know your market and the bloggers you plan to pitch. Create a list and keep close track of who to contact and when you need to get your review pitch out there. Though many things have changed in regards to timing, it doesn't mean you shouldn't plan. I recommend that you sit down with someone who can help you strategize timing so you can plan appropriately for your book launch. A missed date is akin to a missed opportunity.

7. Hiring People Who Aren't in the Book Industry

Let's face it, even to those of us who have been in this industry for a while it still doesn't always make sense. Hiring someone who has no book or publishing experience isn't just a mistake, it could be a costly error. With some vendors like web designers you can get away with that. But someone who has only designed business cards can't, for example, design a book cover. Make sure you hire the right specialist for the right project. Also, you've likely spent years putting together this project, make sure you make choices based on what's right and not what's cheapest. If you shop right you can often find vendors who are perfect for your project and who fit your budget.

8. Designing Your Own Website

You should never cut your own hair or design your own site. Period. End of story. But ok, let me elaborate. Let's say you designed your own site which saved you a few thousand dollars paying a web designer. Now you're off promoting your book and suddenly you're getting a gazillion hits to your site. The problem is the site is not converting these visitors into a sale. How much money did you lose by punting the web designer and doing it yourself? Hard to know. Scary, isn't it?

9. Becoming a Media Diva

Let's face it, you need the media more than they need you. I know. Ouch. But it's the unfortunate truth. So here's the thing: be grateful. Thank the interviewer, send a follow up thank-you note after the interview. Don't expect the interviewer to read your book and don't get upset if they get some facts wrong. Just gently, but professionally, correct them in such a way that they don't look bad or stupid. Never ask for an interview to be redone. Most media people don't have the time. I mention this because it actually happened to a producer friend of mine who did an interview with a guy and he decided he didn't like it and wanted a second shot. Not gonna happen. The thing is, until you get a dressing room with specially designed purple M&M's, don't even think about becoming a diva. The best thing you can do is create relationships. Show up on time, show up prepared, and always, always, always be grateful.

10. Take Advantage

In this instance, I mean take advantage in the best possible way. There are a ton of resources out there for you. Seriously. Compared to when I was first in business almost 13 years ago the resources and free promotional tools that are out there now are almost mind-numbing, and the fact that so many authors don't take advantage of them is even crazier. Things like social media - I know it's a time suck but you would be amazed at how many authors rock out their campaign by just being on Facebook, or Wattpad or even Goodreads. When I wrote a Goodreads article a while back I got some interesting feedback from people who said that there was a lot of negativity on there. Well, that may be so but I've never seen it and if I do, I ignore it. Point being, the stuff is out there. Find out for yourself what works and what doesn't. Yes it's fine to take advice from other authors but you should still experience this for yourself before you decide if it's right for you or not.

When it comes to marketing, the mistakes can cost you more than anything both in time and money. Knowing what to do to market your book is important, but knowing what to avoid may be equally as significant.

Published on October 18, 2013 00:00

October 17, 2013

Bookalicious Reviews The Messiah Matrix

Lisa Briggs-Hardy

Lisa Briggs-Hardy The Messiah Matrix by Kenneth John Atchity is a fast-paced contemporary thriller in which a young Jesuit priest becomes romantically entwined with a vivacious archaeologist as they pursue the hidden history that links Jesus Christ with Augustus Caesar. A year before it occurred, the novel predicted the resignation of the pope and the election of an Argentine Jesuit to succeed him. In a story that will leave readers breathless and hungry for more, Atchity weaves a compelling tale about the foundations of today’s Roman Catholic Church lying deep in the religious rituals of the ancient Roman Empire. From the first page to the last The Messiah Matrix takes the reader on a riveting adventure from the ancient city of Caesarea in Israel to Rome’s labyrinthine catacombs and beyond, and provides gripping evidence for all those who have ever wondered about the historical existence of the Christian Savior. The Messiah Matrix is a tour de force of modern drama and intrigue, classical scholarship, and early church history that will change the way you understand the birth of Christianity. The Messiah Matrix may prove to be one of the most controversial novels ever written. Graeco-Roman scholar, professor, and producer Dr. Atchity is perhaps the only author alive today capable of creating this ground-breaking work.

The Messiah Matrix by Kenneth John Atchity is a fast-paced contemporary thriller in which a young Jesuit priest becomes romantically entwined with a vivacious archaeologist as they pursue the hidden history that links Jesus Christ with Augustus Caesar. A year before it occurred, the novel predicted the resignation of the pope and the election of an Argentine Jesuit to succeed him. In a story that will leave readers breathless and hungry for more, Atchity weaves a compelling tale about the foundations of today’s Roman Catholic Church lying deep in the religious rituals of the ancient Roman Empire. From the first page to the last The Messiah Matrix takes the reader on a riveting adventure from the ancient city of Caesarea in Israel to Rome’s labyrinthine catacombs and beyond, and provides gripping evidence for all those who have ever wondered about the historical existence of the Christian Savior. The Messiah Matrix is a tour de force of modern drama and intrigue, classical scholarship, and early church history that will change the way you understand the birth of Christianity. The Messiah Matrix may prove to be one of the most controversial novels ever written. Graeco-Roman scholar, professor, and producer Dr. Atchity is perhaps the only author alive today capable of creating this ground-breaking work.

The Messiah Matrix

Published on October 17, 2013 00:00

October 16, 2013

Sarian Bouma at the Dole Institute of Politics

Published on October 16, 2013 00:00

Sarian Bouma at the Dole Institute of Politics

Published on October 16, 2013 00:00

October 15, 2013

Vic's Media Room Reviews The Messiah Matrix

Kenneth John Atchity in his new book, “The Messiah Matrix” published by Imprimatur Britannica/Story Merchant Books introduces us to Ryan McKeown and Emily Scelba .

Kenneth John Atchity in his new book, “The Messiah Matrix” published by Imprimatur Britannica/Story Merchant Books introduces us to Ryan McKeown and Emily Scelba .From the back cover: To what lengths would the Vatican go to suppress the secret origins of its power?

The Messiah Matrix is a myth-shattering thriller whose protagonists delve into the secrets of the past and expose those who hide them still.

A renowned scholar-monsignor is killed in a mysterious hit-and-run in Rome. A Roman coin is recovered from a wreck off the coast of ancient Judea. It’s up to his young American protegé–a Jesuit priest–and a vivacious, brilliant archaeologist to connect these seemingly disparate events and unravel the tapestry that conceals in plain view the greatest mystery in the ecclesiastical world.

Together they pursue their passion for truth while fighting to control their passion for each other. What they uncover is an ancient Roman imperial stratagem so controversial the Curia fears it could undermine the very foundations of the Roman Catholic faith.

From the ancient port of Caesarea to Rome’s legendary catacombs and the sacred caves of Cumae, this contemporary novel follows their exhilarating quest to uncover the truth about the historical existence of the real Christian Savior.

The Messiah Matrix may prove to be one of the most thought-provoking books ever written. Classical scholar and Yale Ph.D. Dr. Kenneth John Atchity is the only author alive today capable of creating this literary and historically-based masterpiece.

“All that is hidden must now be revealed.”

Let’s agree that “The Messiah Matrix” is a work of fiction written by an author of fiction. It is not truth nor does it represent itself to be truth. With this as my foundation this is one very exciting book. Ryan and Emily are running around trying to solve the few clues that they have while, simultaneously, trying to stay alive because there are assassins trying to stop them. Do I agree with the premise at the conclusion of this book? Of course not. But then I do not have to as this is fiction. ”The Messiah Matrix” is loaded with twists and turns that will leave you guessing all the while you are flipping pages to find out what happens next.

Mr. Atchity has provided us with a very exciting book with clever characters that I hope come back in this very talented author’s next book.

Reposted From Vic's Media Room

Published on October 15, 2013 12:15