Kenneth Atchity's Blog, page 160

March 17, 2016

Imagination is its own form of courage.—Francis Underwood...

Published on March 17, 2016 00:00

March 16, 2016

Man’s value is in the few things he creates and not in th...

Man’s value is in the few things he creates and not in the many possessions he amasses. ~ Kahil Gibran

Published on March 16, 2016 00:00

March 15, 2016

There’s one common thing that connects all successful peo...

There’s one common thing that connects all successful people: They never quit. Just because you do not quit does not ensure success, but quitting will ensure lack of success.—Todd Robinson

Published on March 15, 2016 17:00

March 14, 2016

Courage is resistance to fear, mastery of fear, not absen...

Published on March 14, 2016 00:00

March 11, 2016

March 9, 2016

There is no native criminal class except Congress.—Mark T...

Published on March 09, 2016 00:00

March 8, 2016

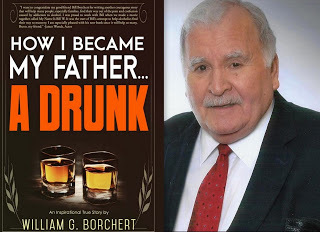

Guest Post: Is A Relapse From Sobriety Inevitable or Preventable? by William G. Borchert

It was around the middle of March, 1961 when my drinking got so bad I was finally lured into one of those Twelve Step recovery meetings in a local church basement. I remember like it was yesterday the room being filled with the thick aroma of coffee and cigarette smoke.

As I glanced around, I saw a bunch of old geezers, some with bulbous noses and others with cauliflower ears and pock-marked cheeks, swapping war stories about their bad days of boozing—drinking Sneaky Pete, sleeping in doorways and shaking so hard their teeth would almost fall out.

I’m sure there were others at the meeting who were less down on their luck, but for some reason I ignored them and focused on what I considered the real alcoholics. I was 27 at the time, the youngest there by 30 years or more and I felt completely out of place.

However, I found the war stories quite entrancing and entertaining so I continued coming for some weeks. Then one night I was asked to say a few words about my own drinking. As I spoke, I got the feeling that I was on my way down the same road these old timers had traveled and it frightened me. What made it worse was when they told me I had an incurable disease called alcoholism that could only be arrested but not cured if I stopped drinking one day at a time.

I thought to myself, are they kidding or what? Okay, so I let my drinking get out of hand for awhile but there’s no way I’m anything like these guys. In fact, I almost felt insulted by their outrageous suggestions.

Actually, as I recall it now, I grinned rather self-righteously at these old fogies while saying to myself, “Even if I do drink too much at times and get into some trouble now and then, I have a very long way to go before I could possibly become anything like these poor drunks.” That’s when my screwed up brain told me I was in the wrong place with the wrong people at the wrong time in my life.

So I finished my coffee and left. I think on the way out I smugly patted myself on the back for spending all those weeks in that church basement giving that Twelve Step program what I thought was an honest to goodness try. That very same night, this phony started drinking again.

Would you call that a relapse? I don’t think so because, looking back on that false start on the road to my eventual recovery, I had never really gotten sober. I had simply cut back on my physical drinking for a very short period of time but never lost my mental obsession for alcohol.

I would simply call that initial experience a rejection of the idea that I could ever get as bad as those old geezers. I was still convinced that a little more willpower and self-control would do the trick.

Then What Is An Actual Relapse? Most experts in the addiction recovery field consider an actual relapse to be the return to the abusive use of alcohol and/or drugs following a serious period of abstinence.

According to Dr. James Garbutt, a professor of psychiatry at The University of North Carolina:

“Relapse has different definitions. Some would say it is the return to any amount of substance abuse while others would say it is a return to heavy use. The generally accepted belief in the medical profession is that an actual relapse is a return to the heavy, destructive use of alcohol and/or drugs after a rather prolonged period of sobriety.”

To put it in sharper focus… if you drink one beer on one occasion, you’ve had what the recovery community calls “a slip.” However, if you’ve been attending meetings in a recovery program on a regular basis, have been working the Twelve Steps and have enjoyed a stable period of sobriety for some time and then return to drinking and its serious consequences in your life, that would be considered a serious relapse.

Such a relapse often requires medical treatment and sometimes psychiatric counseling as well. Then to stay sober once again, it is also vital that one makes an even stronger commitment to a Twelve Step recovery program like Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous as soon as possible. The longer one delays returning to the kind of treatment a support group offers, the more serious the impact of the physical, mental, and spiritual parts of the disease will have on the addict.

Why Does Relapse Occur In Addiction? Dr. Stephen Gilman, an addiction specialist in New York City, says:

“Relapse can occur because an addictive disorder is a chronic disorder. Since there is no cure, there is always the potential for relapse if the addict doesn’t manage his or her disease through a proven program of some type.”

He, like others in the field, notes that “slips,” unlike a serious relapse, generally occur very early in sobriety when people are still not convinced they are truly addicted. It’s called “the investigational period” similar to my observing those old geezers in that church basement. A relapse occurs when one is essentially convinced they can no longer drink or drug safely but then after some period of time, begin to rest on their laurels and take the need for treatment less seriously.

Perhaps that’s one of the reasons why a growing number of folks in the recovery community these days view relapsing as the rule rather than the exception when it comes to addiction treatment. Also a great majority no longer see it as a catastrophic event but rather as an opportunity for learning more and better strategies for overcoming urges and for identifying the moods and situations that used to be difficult to face without a drink.

Many experienced experts in the field will tell you that what Is most inappropriate is the kind of black and white thinking that a serious slip-up turns seemingly successful recovery into sheer disaster and defeat. They say it is not the end of the world as the addict may think or the loss of everything he or she had striven for. They must come to understand that it takes time to change all the mental apparatus that supports any particular habit—the memories and all the situations that can trigger craving—and that sobriety can be rather tenuous until many of those changes take place.

In other words, the disease of addiction greatly affects the brain and it can take a considerable period of time to change the brain back to normal, rational thinking that can reduce the mental obsession and compulsion for an addictive substance.

Suggestions On Avoiding A Relapse There is general agreement in the medical community that over the first two to three years of recovery there is a 40-60 percent chance that alcoholics my experience at least one relapse. For drug addicts, the rate of relapse over that same period of time can run as high as 70 percent. And for those addicted to opiates, there’s an 85-90 percent chance of relapse after two or more years of receiving some form of treatment.

After being sober more than 50 years, I’ve learned from my own experience and of others’ that there are a number of warning signs and symptoms to watch for to prevent a relapse.

First of all, the relapse process begins long before alcohol and/or drugs enter the picture. It starts when the addict slowly begins to withdraw from treatment, whether it be cancelling appointments with an addiction counselor or missing fellowship meetings at Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous. Most people who relapse are not consciously aware that this is putting them in danger. Their disease is telling them they have now learned enough to keep themselves sober.

If these individuals are successful in the eyes of the world, it is easy for them to become complacent. They may become less rigorous about applying all the coping skills they developed when they first learned how to stay sober.

Then, when problems and stress arise as they do in most lives, their disease reminds them what takes away those feelings of fear and anxiety, immediately and effectively. So they pick up a drink or a drug and everyone around who had admired their sobriety wonders how this could have happened.

There is also the mistaken belief that people who start drinking again haven’t really “hit bottom” and therefore need more pain in their lives to reach out once more for help. That’s what makes the disease of addiction so cunning, baffling, and powerful. This is never more evident than when someone whose life is so good returns to a destructive lifestyle.

No alcoholic or drug addict really wants more pain in their lives or a lower bottom that may well cost them everything they had just gotten back in sobriety. In most cases they relapsed simply because they stopped doing the things that were keeping them sober in the first place.

There is one other mistaken belief that is essentially based on being judgemental. It is the belief or perhaps accusation that those who relapse over and over again are “constitutionally incapable” of getting sober since it requires some degree of self-honesty. Alcoholics Anonymous has proven that belief to be wrong time and time again as members who have squandered their sobriety many times over eventually find whatever it is they have been missing and stay sober for the rest of their lives.

Strangely, more relapses occur when life is going well than when it is not. When they do occur, it’s a clear indication that something is missing in the recovery process even if it appears intact to those who associate with the one involved. That’s why it’s essential to remain aware of some of the following symptoms and warning signs.

Warning Signs Of Relapse Resentment ranks high on the symptoms list. Many say it should be in the number one spot. When someone refuses to forgive and forget once they’ve been slighted, mistreated or harmed in some way, that rigid, unhealthy attitude can lead to anger, rage and an almost uncontrollable desire to get even. When not dealt with in a rational, sober way, there’s usually another destructive, drunken spree waiting right around the corner. Don’t get hungry, angry, lonely, or tired. Any of these symptoms can create the kinds of mood swings that used to lead to a drink. In recovery groups, we can find people to socialize with, have lunch or dinner with and go to meetings with and thus avoid these four dangerous symptoms that could trigger a relapse. Hanging out with old drinking buddies is often a sign that an addict’s built-in forgetter is leading him down the wrong path. It’s recalling the old days as being filled with pleasantries and fun rather than all the pain and shame drinking brought into our lives. To prevent relapsing, it’s essential to avoid people, places, and things that could lead us back to alcohol and/or drugs. Self-pity is something else to avoid like a plague. While it may seem at times that the whole world is against us, that we can’t get a break and that life is just not fair, that kind of negative thinking can only lead to disaster. We must use the tools we’ve learned at Twelve Step meetings along with the well-known Serenity Prayer to cope with the curve balls life has a tendency to throw at us.

“God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.” Avoid trying to make up for the things we lost while drinking by working too hard and too long. This can often lead to impatience, tension, and anger particularly when the family doesn’t seem to be showing us enough appreciation for all we’re doing for them. The truth is, it’s usually our own greed that’s driving us together with the refusal to wait for things to improve in God’s time. That can get an alcoholic frustrated and thirsty. Stress is another symptom addicts must constantly be aware of since it comes from all types of sources—family responsibilities, demands on the job, health problems, past debts, and other financial pressures. We should look for ways to relieve stress through such things as hobbies, exercise, seeing comedy shows and even being of greater service in our recovery support group. Complacency is yet another big danger sign. We must be careful when life in sobriety gets too good. That’s when we can rationalize that just one glass of wine at dinner or a small cocktail to celebrate a happy event would be alright. After all, we now have more knowledge and self-control to prevent our drinking from ever getting out of hand again. Right. The problem is, that’s the cunning way our disease talks to us.

The Simple Solution To Preventing Relapse Dr. William Silkworth, the well-known physician who cared for Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder Bill Wilson when his drunken sprees would wind him up in old Towns Hospital in New York City, recommended a very simple solution for avoiding relapse many years ago.

He would tell a story that related an alcoholic who had a relapse to a man who had just suffered a serious heart attack. The cardiologist explained to his patient the heart attack was caused by being seriously overweight, out of shape, eating fatty foods, and smoking three packs of cigarettes a day. After the patient recovered, his physician put him on a special diet, an exercise regimen and insisted he stop smoking so he could stay in good health.

Since the heart patient naturally wanted to live, he went home and did exactly what the cardiologist prescribed, including running two miles three times a week. At the end of six months he had never felt so healthy in his whole life. By the end of the first year, however, he began getting a bit bored with the strict regimen. He felt so good he thought some fried foods and ice cream once in a while wouldn’t really hurt. Then he started cutting back on his exercise, particularly the running. One day he was having lunch with a friend who offered him a cigarette. How could one cigarette hurt he thought?

Soon he was back to not exercising, eating fatty foods and smoking three packs of cigarettes a day. He had now stopped doing the things that had been keeping him well. The result was predictable. He had another major heart attack and almost died.

Dr. Silkworth explained the very same thing can happen with alcoholics and drug addicts. They find a regimen or program that gets them sober and keeps them sober. Then they begin to feel so good they gradually stop doing those things that got them sober in the first place—and they relapse. Some make it back into the treatment that got them well. Others don’t and die.

Dr. Silkworth’s solution to preventing a relapse is that simple. Keep on doing the very same things that got you sober in the first place and you will stay well and sober one day at a time and have a great life.

I know the good doctor’s solution works because I’ve been following his advice for the last 53 years.

Reposted from Rehabcenter.net

Published on March 08, 2016 12:42

March 4, 2016

That which makes you sick, if harnessed, can be that whic...

Published on March 04, 2016 15:11

March 3, 2016

Why Would I Want To Read Another Book About Addiction? Larry Sagen Reviews Bill Borchert's How I Became My Father ... A Drunk!

If there is one book on your recovery booklist for 2016, I’d recommend William (Bill) Borchert’s newest jewel, How I Became My Father…A DRUNK. It’s a well-written, heartfelt story about the unfolding drama of generational addiction and recovery and the influential role of the family. It’s a great read not just for students and young adults who are struggling with addiction, but also for their families and extended families who can support them in recovery.

The book is engaging, entertaining, and offers hope. Borchert is an excellent writer. Through his personal stories he shares both the horrific tragedy and paradoxical humor of growing-up with his alcoholic father and enabling mother.

The unfolding drama provides many enlightening, ‘ahaa’ moments, as Borchert comes to grips with the fact that as much as he despised his parents for his painful childhood, he then went on to create the same horrific dilemmas for his wife and children.

If you don’t know about author Bill Borchert, he’s written a number of best-selling books and award winning movie screenplays including My Name is Bill W and Lois Wilson’s story about founding Al-Anon, When Love Is Not Enough. My Name is Bill W is the most watched TV movie ever made and was nominated for a number of Emmy’s and Golden Globes. Renowned actor James Woods won the Emmy Award for his role as Bill W.

In reading How I Became My Father…A DRUNK, I got the sense that it was a very personal and touching venture for the seasoned Borchert. I interviewed him for this review and he explained that the previous books he’s written were about other peoples’ lives. This was his first writing journey into his own dark journey (and soul).

Borchert helps readers understand the generational impact of addiction. He clearly articulates how addiction not only influences, but lives deep in the genes, beliefs, and behaviors of future generations. It’s supportive and freeing to see and understand that although we are each personally responsible and accountable for our choices, there are also familial patterns that make each of us more vulnerable.

Although the book title alludes to issues between fathers and sons, I must say that after reading it the story is certainly not gender specific. How I became My Father…A DRUNK speaks to all genders, family positions, and ages. Borchert’s writing style and story are both engaging and illuminating. I wish that it was required reading for all college students, whether they’re struggling with addiction or not.

Borchert’s book has gotten rave reviews from Award-winning actor James Woods, Emmy and Peabody Award-winning producer Norman Stephens, Oscar and Grammy Award-winning songwriter and actor Paul Williams and Andrew Pucher, President of the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence.

I give How I became My Father…A DRUNK a strong five stars. The paperback and Kindle version are available at Amazon.com. For more information about William (Bill) Borchert, please visit his website: williamborchert.com/.

Reviewed by Larry Sagen, MSW (retired)

Larry Sagen was originally trained as a family therapist. Over the last 20+ years he founded and directed two North American nonprofits. In “retirement” Sagen has founded reFrame Entertainment, producing and publicizing films, books, music, and events that help people to overcome personal and systemic challenges.

Published on March 03, 2016 00:00

March 2, 2016

Story Merchant Books Launches Ms. Brae MacKenzie - A Romance of Mythic Identity

READ THE FIRST TWO CHAPTERS!

ONE

The fog, on this chilly July morning, lingered at the Golden Gate. Brae was oblivious to everything except the sea below. Her eyes, dark green in sunlight like the sea now was in the fog, were at this moment a shrouded gray. She stared down from the bridge, hypnotized by the water, dizzied—her elegant figure swaying to the alien rhythm of its own inner tide.

The passing tugboat whistled its warning; a huge back crow shrieked at eye-level; a trans-ocean jet droned above. But Brae, on that bridge, heard nothing. The bright red of bulwarks, cables’ steel blue, golden reflections from windows and glass buildings on crowded hills, sun rising to dismiss the fog—a night cloak with no color, just gray, a precise match to her hooded eyes. Which was the source, which the reflection? Her vision was failing.

A motorist touched his brakes in alarm, then, looking in his mirror, was relieved to see the striking young woman with auburn hair wasn’t about to jump after all. She seemed authorized, standing at the forbidden railing to accomplish a licensed purpose. He lost sight of her in his rearview mirror but kept her eyes in mind until lunchtime, an alluring image of mysterious intent.

The spell was broken for her now. Brae reached down into her straw bag and removed what looked like an ancient lace handkerchief, carefully folded. She opened it quickly, cupping its contents in her hand: two gold rings, intertwined. She turned the rings to catch the tentative rays of sunlight and, when none obliged her, bit her lip, kissed the rings, and without hesitating further, flung them from the cloth into the crow’s air. Holding her breath, she ignored his raucous outcry, watched the rings hit the surface of the water and disappear. She breathed deeply as though an immense barrier, whose shape and purpose were still unknown, had now been crossed.

She cocked her head to one side, holding her left arm at the wrist with her right hand in the gesture she knew she had inherited from her father. She heeded the crow now, heard the tugs, and registered the jet— all on their ways to organize the day the way they needed to. The clue she sought was not in them, and she tilted her head, filtering out their sounds again as she had already filtered out the sounds of the traffic on the bridge.

The ceaseless traffic. Surely that was the problem. How could you hear what you needed to hear through this infernal clamor that had claimed the paradise of San Francisco for its own? The noise of the traffic washed over her now, washed through her, threatening to make her fall. It was overpowering. Of course she wouldn’t hear anything in this cacophonous place.

Brae looked at the imaginary patch of water where her immediate past had disappeared so readily, and walked slowly toward the Sausalito shore. The noise of the traffic, the tug boat’s whistles, even the crows and the jet were gone. She didn’t smell the fumes from the double-trailer truck roaring by her or feel the rude wind of its passing. Does sensation fade with memory? Then why do I remember my childhood now? Tears started to sting her eyes. Something broken inside her told her that the past she had discarded was not her true past. She didn’t even notice the sun had vanquished the fog.

“I don’t know what’s wrong.” She handed Tommy his lunch bag. “But it’s all on me, not you, honey. Just ignore your silly mother, and have a good time.” Her voice was cheerful.

The seven-year-old boy looked at her with his dark blue eyes and blinked. He gave her a quick kiss and darted off to the waiting van.

“See you!” he shouted.

Brae held back her tears until the day-camp van pulled away. What was wrong with her? She’d done it now. Now it was supposed to be better. Symbols require action—and she had taken the action they required this morning on the bridge. She should be free now. People die, other people survive their deaths. I’m not the first young widow—even on my block. Marita’s husband, three years ago—killed absurdly in the Colombian consulate because he happened to stop that hour for a surprise visit to his old buddy the Consul General. But Marita had soldiered on. She was living a happy, normal, productive life. She still had purpose.

After a year I still feel nothing, care about nothing, understand nothing about why I don’t feel and don’t care. Was it Tom or is it me? Brae recited her daily litany of self-criticism as she started the mechanical chores of the morning: arranging old brushes, arranging new brushes, stacking and restacking cardboard and canvas squares and triangles and oblongs. I’m losing it, losing my mind, losing my friends, losing my son, and losing my life—because no one wants to hear it any longer. Even my psychoanalyst dismissed me. Imagine that, in California! “Excessive and self-indulgent and unwilling to help yourself.” Damn. She threw a dishtowel at the neighbor’s tabby who, still licking his lips, jumped nimbly across the spilled milk glass that Tommy’d left undrunk.

Brae’s tears slowed as she poured boiling water into her favorite teapot, its oak-leaf gilding nearly worn away. The one relic—aside from the lace handkerchief—she owned of her Scottish grandmother. Thank God I decided not to cancel the London exhibit. Even if it doesn’t help me, it will be a relief for Tommy, Jason, Marita, and the few other friends she still saw. She felt like her work was an illusion done with mirrors, but as long as Jason was able to make a living pushing it, it gave her something to do. What a laugh. One more Sunset on the Golden Gate and she would throw up. She kept painting what she could no longer see—perhaps had never really seen. Brae wrenched the curtain closed, shutting out the radiant engineering and tourist marvel. She bit her lip.

Her iPhone rang.

“Yes?” she answered, with a tentative relief that, she was sure, made her callers laugh to themselves. It was Marita.

“I’m fine.” Brae bit her lip again, determined to sound fine. “I’m over it finally—on my way.”

Marita, who didn’t sound like she believed her, didn’t press the matter this morning. She was, for once, more business than counsel. Yes, she was still willing to take care of Tommy for three whole weeks after camp. Jeff would be overjoyed for the company. Yes, she could manage quite well, thank you—and would have plenty of help, since Brad, her trial spouse, had just announced he was taking children more seriously and wanted to see how they worked at close hand.

“How ingenious of him,” Brae remarked.

Marita’s silence put her back on track.

“Sorry. I was just joking, you know. Brad is perfect for you—and this is a major shift in his position.”

Marita’s voice accepted Brae’s retraction. She could leave for New York with full assurance that Tommy would be safe and sound.

“I didn’t say sane,” Marita added.

Brae laughed. Saturday morning would be fine.

On the way to SFO, with the boys wrestling in the back of Marita’s station wagon, Brae was grim; her silence the only defense she knew against the future that she feared was shaped by the failure of last week’s determination. Marita could do without one last sob session anyway. Silence was a much better going away present.

Marita accepted it until they passed Candlestick Park. “Look,” she demanded, reaching across to touch her old college roommate on the shoulder. “I am alive. I am young. I am beautiful. I have a son. I have time. I am wonderful. Say it after me.”

“I am selfish. I am spoiled. I am superficial. I am a mixed-up bitch.” Brae recited, brushing angrily at her eyes with her sleeve. “I know your catechism by heart. I wish with all my heart it were mine. It sounds so good—“

“You think it’s nonsense?”

“No,” Brae said softly, smiling at her earnest little friend. “If one thing in my dense inner fog is visible, it’s that you do not speak nonsense, your life is not fake, and your advice is the real thing. It’s me—I’m the fraud. I don’t belong on this planet with real people.”

Marita’s reply was a look of long-suffering understanding, and she shook her head to show that words failed between them. Silence was better.

Here was a woman who—despite the admitted tragedy of losing the perfect husband to cancer—had the whole wide world at her feet. At her still quite delicate and pretty feet. Brae was well-off, both from her husband and from the untold holdings that would someday come to her as Davis Mackenzie’s only child. She was enviously attractive—Marita’s gnawing envy was the proof. Her self-image had become resigned from the very day they decided to room together at Bryn Mawr. No matter what she ate, Marita’s body came out looking not quite properly balanced in the runway image. Thank God they were starting to outlaw ridiculous body-fat ratios. Brae’s healthy complexion and trim figure never really changed, whether she was starving herself for a role in a stage production or stuffing herself with designer pizza when the production ended.

Now Brae was one of the most popular and talented painters in the Bay Area—in all of California—with a Knightsbridge exhibit only two years after her first showing at MOMA. Brae was selfish, Marita thought. Unbelievably selfish, when you stopped and thought about it. How could you possibly sympathize with a woman who, with all these riches, insisted on feeling that she somehow missed the boat? Sorry over something that, while it lasted, was beautiful and happy.

At least Brae never denied the perfection of her marriage to Tom. He had been the dream husband—dashing genes, perfect teeth, a politician’s smile but the conscience of a judge, a smooth dancer—and one of the most capacious hollow legs in the Irish Catholic drinking community of Marin County. Tom and Brae were the perfect couple—the beheld of all beholders. When their son was born—Tom had ordered a male heir—Marita felt the old pangs of jealousy for what she, and everyone else, considered the enviable fate of Brae Mackenzie. Even her goddamned breasts were the perfect size—not too flat, and not too ample like her own. It wasn’t fair for one woman to have the whole shooting match.

Especially one woman who could not seem to appreciate her own good fortune.

“In one way,” she tried to explain to Brae two months after Tom’s celebrity funeral, “even Tom’s death adds to the beauty of your life.” Brae looked startled at this declaration. “I know it sounds terrible, but it gives you depth, a touch of tragedy.”

Brae began to protest that she didn’t feel Tom’s death was a tragedy, didn’t feel it had anything to do with her at all, any more than this admirably cluttered life had to do with her life. Because her life, not Tom’s death, was the tragedy.

Marita wouldn’t listen. “Look at it this way,” she explained, trying another tack. “If he’d lived, with his kind of high-pressure pace, you’d have probably ended up in divorce like everyone else in this screwed up society. This way no one can ever take the memory of your perfect marriage away from you.”

Brae didn’t argue with Marita then, because it was futile. Marita was a die-hard romantic. How could she make anyone understand that Marita was right for the wrong reasons? The memory could never be taken from her, true enough. Because the reality was never hers, never a real part of her, in the first place. She had kept silent then, as she did now as they approached the airport.

Marita commended herself, as she had more than once since becoming Brae’s good friend, on her own simplicity. “You can have your brooding complexities,” she told Brae once. “They’re all that stand between you and what, by anyone else’s standards, should be an extraordinarily happy life.”

The trouble was, Marita did feel sorry for her friend. Sorry because Brae couldn’t appreciate herself, couldn’t enjoy the beauty of her life and art as much as those around her did. She’d known Brae long enough to know her friend wasn’t faking her unhappiness. Baffling it might be, but not an act like the anxiety of every other neurotic at a given cocktail party. Brae was different from those around her, different even from Tom, Marita knew. She acted perpetually at a loss. Tom—a gregarious optimist from the word hello—seemed like he’d always just discovered something or someone terrific.

Even the shrink Marita sent her to last fall couldn’t help. She terminated Brae’s visits—rare even for a Berkeley psychotherapist—because, she concluded, the patient wasn’t willing to help herself. The funk Brae fell into after Tom’s death turned her into an empty shell of her former self. Made her question the validity of that self. From the day they’d met in the Bryn Mawr dorm room, when she showed up lugging every imaginable form of luggage except a normal suitcase, Brae seemed like a whirlwind that would cut its path through life without opposition, touching earth only rarely to make a friendship or accept a marriage. But at Tom’s funeral Marita could see the wind go out of her friend. “I thought I knew where I was going,” Brae had commented enigmatically, refusing to say more.

Even though she claimed she was now a zombie inside, Brae looked the same. If Marita hadn’t heard what Brae’s self-talk was like, she wouldn’t have guessed in a million years at the uncertainties that dogged her. How could any number of sessions be enough to unravel it?

“My life is flashing before my eyes all the time,” Brae moaned, “and it’s nothing but a blur!”

“It’s natural to review the past at times like this,” the stout psychotherapist remarked. “It’s how we deal with death, reorganizing life by putting the dead away from us, in their proper place in memory.”

That made Brae protest all the louder. “You don’t understand. My life is what I’m reviewing, not Tom’s. Not ours. I know he’s dead, dammit, and I know the marriage is over.”

“You feel you’re dead, too?”

“I realize I’ve been that way all my life,” she nearly shouted. It’s why she married Tom, hoping for a fix. All this prime-time confession was no help at all.

Once she’d gotten over the annual disappointment of childhood Christmases, when the tree never matched the splendor of what she expected a tree might be, Brae awaited adulthood instead of the annual holiday; going for the gold ring she called it, knowing—trusting—in her heart that maturity would bring her the satisfaction she longed for. While she waited, she learned to draw, then to paint, throwing her spirit into her fingers to distract herself from the darkness gnawing at its root. People encouraged her “art,” saying she had “vision.” Brae knew they were wrong. She had accurate observation, not vision. She hungered for vision. Adulthood brought her California, Tom, fame, and then Tommy.

Looking across the seat at her competent and contented friend, Brae wondered why life had culled her out as the butt of one of its lousiest jokes. Marita had so much less—and so much more. She enjoyed life and herself, coming to terms with both almost instinctively. Like Tom. No questions: just embrace it and love it to death. Brae’s longing for the depths of experience was probably just a perversion of her nature, a suicidal delusion. What made her think those depths existed or that, finding them, she would be any happier than Marita and Tom were on what she called the surface? Marita loved her paintings, ones Brae considered mechanical and thin. Marita loved them because “they’re vibrant and uplifting.” Brae thought them flat and soulless. They depressed her, and she was always happy to see them go out the door.

Well, what did she know? Her work was wildly successful by any struggling artist’s measure. Who was Brae to say all those happy buyers were wrong? Maybe they see something that she doesn’t. Or was it enough that the colors complimented their designer sofas?

As the car pulled up in front of the United terminal, Brae snapped herself out of it. She pressed Marita’s hand.

“Hey, you’re the best. I don’t know how you’ve put up with me all these years. I want you to know two things. I appreciate you and—”

She was interrupted by a tumbling body as Tommy hurled himself into her lap from the back seat. He is hysterical, Brae thought, in a sudden panic. She loathed departures.

Tommy was not hysterical. He was giggling, from Jeff’s latest tickling assault.

“Will you be okay, honey?” she asked her son.

His bear hug was answer enough.

“Bring me—and Jeff—a Bobby from London,” he yelled, as she passed her luggage to a baggage attendant.

Brae laughed, and looked at Marita with relief.

“Don’t worry about us,” Marita shouted. “We won’t go crazy, but we can’t promise sanity either!” She waved and pulled the station wagon into traffic.

Brae’s window seat allowed a last glimpse of the tips of the Golden Gate rising above the fog as the jet climbed into yet another cloud layer. Then the city, like her life, seemed no more than the final wisps of an uneasy dream.

TWO

She was remembering a time when she was four years old, and the fog across Long Island lured her away—until her frantic father called for the police. His daughter was missing! They located her in a willow tree less than a half-mile from the cemetery. She put up no resistance when they brought her back to where the long, sleek limousine awaited and her father paced under the huge oak tree. When he saw her, he rushed her into his arms and, without a word, tipped his hat to the policeman and bundled her into the dreadful car.

Brae awakened with a start. Her plane was making its final approach to JFK and, according to the flight attendant whose hand was still on her shoulder, it was time to fasten her seatbelt. Brae dreaded the hour to come. Once she was safe at her father’s penthouse on Sutton Place, she loved being back in New York. But she hated the transition that began at the airport.

“Sorry I couldn’t meet your plane,” Davis Mackenzie was saying. He took her bag from the doorman first, then turned to her with a smile. “Get your fanny inside, young lady.”

She laughed. Davis would never change. She adored her father’s presence—for that’s what it was, an almost tangible presence. Intensity and eternity rolled into one, as though everything important in her life was happening right now, in his immediate vicinity. And as though, regardless of what that important thing might be, he would handle it as easily as he handled all the important things before.

The transition forgotten, Brae allowed herself the luxury of burying her head in her father’s strong shoulder, holding on a moment longer than they both knew was socially acceptable.

“Where’s Valerie?” Brae asked.

“I know you’ll be broken-hearted, dear, but she’s in Connecticut and couldn’t make it back. She sent you her very best.”

They both laughed because they both knew what the other was thinking.

“Besides,” Davis added, “we have much to talk about.” He looked into his daughter’s green eyes. “Don’t we?”

Brae nodded. It was great to be home, but the last thing she wanted to do was talk. Her father understood that without words, and lugged her bags into the same bedroom she’d always slept in when she visited Manhattan. The narrow cot underneath the window that looked out at the East River and the 69th Street Bridge had as firm a place in her imagination as Heidi’s loft, and Brae saw with satisfaction that Valerie’s touch had not extended here: the room and the cot remained unchanged.

That’s a laugh, she corrected herself. They didn’t look changed. But they were now part of Valerie’s territory and, of course, that changed everything. There’s always more than meets the eye. Brae felt again the deep pang that came from recognizing, in a part of her being that knew nothing of reason, that she would never marry her father—her longest-lasting childhood fantasy.

ONE

The fog, on this chilly July morning, lingered at the Golden Gate. Brae was oblivious to everything except the sea below. Her eyes, dark green in sunlight like the sea now was in the fog, were at this moment a shrouded gray. She stared down from the bridge, hypnotized by the water, dizzied—her elegant figure swaying to the alien rhythm of its own inner tide.

The passing tugboat whistled its warning; a huge back crow shrieked at eye-level; a trans-ocean jet droned above. But Brae, on that bridge, heard nothing. The bright red of bulwarks, cables’ steel blue, golden reflections from windows and glass buildings on crowded hills, sun rising to dismiss the fog—a night cloak with no color, just gray, a precise match to her hooded eyes. Which was the source, which the reflection? Her vision was failing.

A motorist touched his brakes in alarm, then, looking in his mirror, was relieved to see the striking young woman with auburn hair wasn’t about to jump after all. She seemed authorized, standing at the forbidden railing to accomplish a licensed purpose. He lost sight of her in his rearview mirror but kept her eyes in mind until lunchtime, an alluring image of mysterious intent.

The spell was broken for her now. Brae reached down into her straw bag and removed what looked like an ancient lace handkerchief, carefully folded. She opened it quickly, cupping its contents in her hand: two gold rings, intertwined. She turned the rings to catch the tentative rays of sunlight and, when none obliged her, bit her lip, kissed the rings, and without hesitating further, flung them from the cloth into the crow’s air. Holding her breath, she ignored his raucous outcry, watched the rings hit the surface of the water and disappear. She breathed deeply as though an immense barrier, whose shape and purpose were still unknown, had now been crossed.

She cocked her head to one side, holding her left arm at the wrist with her right hand in the gesture she knew she had inherited from her father. She heeded the crow now, heard the tugs, and registered the jet— all on their ways to organize the day the way they needed to. The clue she sought was not in them, and she tilted her head, filtering out their sounds again as she had already filtered out the sounds of the traffic on the bridge.

The ceaseless traffic. Surely that was the problem. How could you hear what you needed to hear through this infernal clamor that had claimed the paradise of San Francisco for its own? The noise of the traffic washed over her now, washed through her, threatening to make her fall. It was overpowering. Of course she wouldn’t hear anything in this cacophonous place.

Brae looked at the imaginary patch of water where her immediate past had disappeared so readily, and walked slowly toward the Sausalito shore. The noise of the traffic, the tug boat’s whistles, even the crows and the jet were gone. She didn’t smell the fumes from the double-trailer truck roaring by her or feel the rude wind of its passing. Does sensation fade with memory? Then why do I remember my childhood now? Tears started to sting her eyes. Something broken inside her told her that the past she had discarded was not her true past. She didn’t even notice the sun had vanquished the fog.

“I don’t know what’s wrong.” She handed Tommy his lunch bag. “But it’s all on me, not you, honey. Just ignore your silly mother, and have a good time.” Her voice was cheerful.

The seven-year-old boy looked at her with his dark blue eyes and blinked. He gave her a quick kiss and darted off to the waiting van.

“See you!” he shouted.

Brae held back her tears until the day-camp van pulled away. What was wrong with her? She’d done it now. Now it was supposed to be better. Symbols require action—and she had taken the action they required this morning on the bridge. She should be free now. People die, other people survive their deaths. I’m not the first young widow—even on my block. Marita’s husband, three years ago—killed absurdly in the Colombian consulate because he happened to stop that hour for a surprise visit to his old buddy the Consul General. But Marita had soldiered on. She was living a happy, normal, productive life. She still had purpose.

After a year I still feel nothing, care about nothing, understand nothing about why I don’t feel and don’t care. Was it Tom or is it me? Brae recited her daily litany of self-criticism as she started the mechanical chores of the morning: arranging old brushes, arranging new brushes, stacking and restacking cardboard and canvas squares and triangles and oblongs. I’m losing it, losing my mind, losing my friends, losing my son, and losing my life—because no one wants to hear it any longer. Even my psychoanalyst dismissed me. Imagine that, in California! “Excessive and self-indulgent and unwilling to help yourself.” Damn. She threw a dishtowel at the neighbor’s tabby who, still licking his lips, jumped nimbly across the spilled milk glass that Tommy’d left undrunk.

Brae’s tears slowed as she poured boiling water into her favorite teapot, its oak-leaf gilding nearly worn away. The one relic—aside from the lace handkerchief—she owned of her Scottish grandmother. Thank God I decided not to cancel the London exhibit. Even if it doesn’t help me, it will be a relief for Tommy, Jason, Marita, and the few other friends she still saw. She felt like her work was an illusion done with mirrors, but as long as Jason was able to make a living pushing it, it gave her something to do. What a laugh. One more Sunset on the Golden Gate and she would throw up. She kept painting what she could no longer see—perhaps had never really seen. Brae wrenched the curtain closed, shutting out the radiant engineering and tourist marvel. She bit her lip.

Her iPhone rang.

“Yes?” she answered, with a tentative relief that, she was sure, made her callers laugh to themselves. It was Marita.

“I’m fine.” Brae bit her lip again, determined to sound fine. “I’m over it finally—on my way.”

Marita, who didn’t sound like she believed her, didn’t press the matter this morning. She was, for once, more business than counsel. Yes, she was still willing to take care of Tommy for three whole weeks after camp. Jeff would be overjoyed for the company. Yes, she could manage quite well, thank you—and would have plenty of help, since Brad, her trial spouse, had just announced he was taking children more seriously and wanted to see how they worked at close hand.

“How ingenious of him,” Brae remarked.

Marita’s silence put her back on track.

“Sorry. I was just joking, you know. Brad is perfect for you—and this is a major shift in his position.”

Marita’s voice accepted Brae’s retraction. She could leave for New York with full assurance that Tommy would be safe and sound.

“I didn’t say sane,” Marita added.

Brae laughed. Saturday morning would be fine.

On the way to SFO, with the boys wrestling in the back of Marita’s station wagon, Brae was grim; her silence the only defense she knew against the future that she feared was shaped by the failure of last week’s determination. Marita could do without one last sob session anyway. Silence was a much better going away present.

Marita accepted it until they passed Candlestick Park. “Look,” she demanded, reaching across to touch her old college roommate on the shoulder. “I am alive. I am young. I am beautiful. I have a son. I have time. I am wonderful. Say it after me.”

“I am selfish. I am spoiled. I am superficial. I am a mixed-up bitch.” Brae recited, brushing angrily at her eyes with her sleeve. “I know your catechism by heart. I wish with all my heart it were mine. It sounds so good—“

“You think it’s nonsense?”

“No,” Brae said softly, smiling at her earnest little friend. “If one thing in my dense inner fog is visible, it’s that you do not speak nonsense, your life is not fake, and your advice is the real thing. It’s me—I’m the fraud. I don’t belong on this planet with real people.”

Marita’s reply was a look of long-suffering understanding, and she shook her head to show that words failed between them. Silence was better.

Here was a woman who—despite the admitted tragedy of losing the perfect husband to cancer—had the whole wide world at her feet. At her still quite delicate and pretty feet. Brae was well-off, both from her husband and from the untold holdings that would someday come to her as Davis Mackenzie’s only child. She was enviously attractive—Marita’s gnawing envy was the proof. Her self-image had become resigned from the very day they decided to room together at Bryn Mawr. No matter what she ate, Marita’s body came out looking not quite properly balanced in the runway image. Thank God they were starting to outlaw ridiculous body-fat ratios. Brae’s healthy complexion and trim figure never really changed, whether she was starving herself for a role in a stage production or stuffing herself with designer pizza when the production ended.

Now Brae was one of the most popular and talented painters in the Bay Area—in all of California—with a Knightsbridge exhibit only two years after her first showing at MOMA. Brae was selfish, Marita thought. Unbelievably selfish, when you stopped and thought about it. How could you possibly sympathize with a woman who, with all these riches, insisted on feeling that she somehow missed the boat? Sorry over something that, while it lasted, was beautiful and happy.

At least Brae never denied the perfection of her marriage to Tom. He had been the dream husband—dashing genes, perfect teeth, a politician’s smile but the conscience of a judge, a smooth dancer—and one of the most capacious hollow legs in the Irish Catholic drinking community of Marin County. Tom and Brae were the perfect couple—the beheld of all beholders. When their son was born—Tom had ordered a male heir—Marita felt the old pangs of jealousy for what she, and everyone else, considered the enviable fate of Brae Mackenzie. Even her goddamned breasts were the perfect size—not too flat, and not too ample like her own. It wasn’t fair for one woman to have the whole shooting match.

Especially one woman who could not seem to appreciate her own good fortune.

“In one way,” she tried to explain to Brae two months after Tom’s celebrity funeral, “even Tom’s death adds to the beauty of your life.” Brae looked startled at this declaration. “I know it sounds terrible, but it gives you depth, a touch of tragedy.”

Brae began to protest that she didn’t feel Tom’s death was a tragedy, didn’t feel it had anything to do with her at all, any more than this admirably cluttered life had to do with her life. Because her life, not Tom’s death, was the tragedy.

Marita wouldn’t listen. “Look at it this way,” she explained, trying another tack. “If he’d lived, with his kind of high-pressure pace, you’d have probably ended up in divorce like everyone else in this screwed up society. This way no one can ever take the memory of your perfect marriage away from you.”

Brae didn’t argue with Marita then, because it was futile. Marita was a die-hard romantic. How could she make anyone understand that Marita was right for the wrong reasons? The memory could never be taken from her, true enough. Because the reality was never hers, never a real part of her, in the first place. She had kept silent then, as she did now as they approached the airport.

Marita commended herself, as she had more than once since becoming Brae’s good friend, on her own simplicity. “You can have your brooding complexities,” she told Brae once. “They’re all that stand between you and what, by anyone else’s standards, should be an extraordinarily happy life.”

The trouble was, Marita did feel sorry for her friend. Sorry because Brae couldn’t appreciate herself, couldn’t enjoy the beauty of her life and art as much as those around her did. She’d known Brae long enough to know her friend wasn’t faking her unhappiness. Baffling it might be, but not an act like the anxiety of every other neurotic at a given cocktail party. Brae was different from those around her, different even from Tom, Marita knew. She acted perpetually at a loss. Tom—a gregarious optimist from the word hello—seemed like he’d always just discovered something or someone terrific.

Even the shrink Marita sent her to last fall couldn’t help. She terminated Brae’s visits—rare even for a Berkeley psychotherapist—because, she concluded, the patient wasn’t willing to help herself. The funk Brae fell into after Tom’s death turned her into an empty shell of her former self. Made her question the validity of that self. From the day they’d met in the Bryn Mawr dorm room, when she showed up lugging every imaginable form of luggage except a normal suitcase, Brae seemed like a whirlwind that would cut its path through life without opposition, touching earth only rarely to make a friendship or accept a marriage. But at Tom’s funeral Marita could see the wind go out of her friend. “I thought I knew where I was going,” Brae had commented enigmatically, refusing to say more.

Even though she claimed she was now a zombie inside, Brae looked the same. If Marita hadn’t heard what Brae’s self-talk was like, she wouldn’t have guessed in a million years at the uncertainties that dogged her. How could any number of sessions be enough to unravel it?

“My life is flashing before my eyes all the time,” Brae moaned, “and it’s nothing but a blur!”

“It’s natural to review the past at times like this,” the stout psychotherapist remarked. “It’s how we deal with death, reorganizing life by putting the dead away from us, in their proper place in memory.”

That made Brae protest all the louder. “You don’t understand. My life is what I’m reviewing, not Tom’s. Not ours. I know he’s dead, dammit, and I know the marriage is over.”

“You feel you’re dead, too?”

“I realize I’ve been that way all my life,” she nearly shouted. It’s why she married Tom, hoping for a fix. All this prime-time confession was no help at all.

Once she’d gotten over the annual disappointment of childhood Christmases, when the tree never matched the splendor of what she expected a tree might be, Brae awaited adulthood instead of the annual holiday; going for the gold ring she called it, knowing—trusting—in her heart that maturity would bring her the satisfaction she longed for. While she waited, she learned to draw, then to paint, throwing her spirit into her fingers to distract herself from the darkness gnawing at its root. People encouraged her “art,” saying she had “vision.” Brae knew they were wrong. She had accurate observation, not vision. She hungered for vision. Adulthood brought her California, Tom, fame, and then Tommy.

Looking across the seat at her competent and contented friend, Brae wondered why life had culled her out as the butt of one of its lousiest jokes. Marita had so much less—and so much more. She enjoyed life and herself, coming to terms with both almost instinctively. Like Tom. No questions: just embrace it and love it to death. Brae’s longing for the depths of experience was probably just a perversion of her nature, a suicidal delusion. What made her think those depths existed or that, finding them, she would be any happier than Marita and Tom were on what she called the surface? Marita loved her paintings, ones Brae considered mechanical and thin. Marita loved them because “they’re vibrant and uplifting.” Brae thought them flat and soulless. They depressed her, and she was always happy to see them go out the door.

Well, what did she know? Her work was wildly successful by any struggling artist’s measure. Who was Brae to say all those happy buyers were wrong? Maybe they see something that she doesn’t. Or was it enough that the colors complimented their designer sofas?

As the car pulled up in front of the United terminal, Brae snapped herself out of it. She pressed Marita’s hand.

“Hey, you’re the best. I don’t know how you’ve put up with me all these years. I want you to know two things. I appreciate you and—”

She was interrupted by a tumbling body as Tommy hurled himself into her lap from the back seat. He is hysterical, Brae thought, in a sudden panic. She loathed departures.

Tommy was not hysterical. He was giggling, from Jeff’s latest tickling assault.

“Will you be okay, honey?” she asked her son.

His bear hug was answer enough.

“Bring me—and Jeff—a Bobby from London,” he yelled, as she passed her luggage to a baggage attendant.

Brae laughed, and looked at Marita with relief.

“Don’t worry about us,” Marita shouted. “We won’t go crazy, but we can’t promise sanity either!” She waved and pulled the station wagon into traffic.

Brae’s window seat allowed a last glimpse of the tips of the Golden Gate rising above the fog as the jet climbed into yet another cloud layer. Then the city, like her life, seemed no more than the final wisps of an uneasy dream.

TWO

She was remembering a time when she was four years old, and the fog across Long Island lured her away—until her frantic father called for the police. His daughter was missing! They located her in a willow tree less than a half-mile from the cemetery. She put up no resistance when they brought her back to where the long, sleek limousine awaited and her father paced under the huge oak tree. When he saw her, he rushed her into his arms and, without a word, tipped his hat to the policeman and bundled her into the dreadful car.

Brae awakened with a start. Her plane was making its final approach to JFK and, according to the flight attendant whose hand was still on her shoulder, it was time to fasten her seatbelt. Brae dreaded the hour to come. Once she was safe at her father’s penthouse on Sutton Place, she loved being back in New York. But she hated the transition that began at the airport.

“Sorry I couldn’t meet your plane,” Davis Mackenzie was saying. He took her bag from the doorman first, then turned to her with a smile. “Get your fanny inside, young lady.”

She laughed. Davis would never change. She adored her father’s presence—for that’s what it was, an almost tangible presence. Intensity and eternity rolled into one, as though everything important in her life was happening right now, in his immediate vicinity. And as though, regardless of what that important thing might be, he would handle it as easily as he handled all the important things before.

The transition forgotten, Brae allowed herself the luxury of burying her head in her father’s strong shoulder, holding on a moment longer than they both knew was socially acceptable.

“Where’s Valerie?” Brae asked.

“I know you’ll be broken-hearted, dear, but she’s in Connecticut and couldn’t make it back. She sent you her very best.”

They both laughed because they both knew what the other was thinking.

“Besides,” Davis added, “we have much to talk about.” He looked into his daughter’s green eyes. “Don’t we?”

Brae nodded. It was great to be home, but the last thing she wanted to do was talk. Her father understood that without words, and lugged her bags into the same bedroom she’d always slept in when she visited Manhattan. The narrow cot underneath the window that looked out at the East River and the 69th Street Bridge had as firm a place in her imagination as Heidi’s loft, and Brae saw with satisfaction that Valerie’s touch had not extended here: the room and the cot remained unchanged.

That’s a laugh, she corrected herself. They didn’t look changed. But they were now part of Valerie’s territory and, of course, that changed everything. There’s always more than meets the eye. Brae felt again the deep pang that came from recognizing, in a part of her being that knew nothing of reason, that she would never marry her father—her longest-lasting childhood fantasy.

Published on March 02, 2016 10:38