Kenneth Atchity's Blog, page 139

May 26, 2017

"Selling Your Story to Hollywood: A Conversation with a Movie Producer" Audio Replay

“Selling Your Story to Hollywood: A Conversation with a Movie Producer” Audio Replay

I've had such a great response to my interview with Build Book Buzz's Sandra Beckwith on how to sell your story to Hollywood teleseminar that I'm sharing the replay link for those of you who missed it or want to revisit it.

I've had such a great response to my interview with Build Book Buzz's Sandra Beckwith on how to sell your story to Hollywood teleseminar that I'm sharing the replay link for those of you who missed it or want to revisit it.Here’s the audio recording for “Selling Your Story to Hollywood: A Conversation with a Movie Producer".

Click here for the audio REPLAY to Listen to Your Recording

Prefer to Download the Audio? Click Here to Download Your Recording

(If the recording opens in a new tab in your browser instead of downloading, simply right-click the link above and choose “Save File As” or “Save Target As” and choose your preferred save location.)

We hope you enjoy the recorded conversation about the book-to-movie process. Feel free to share this link with authors who want to know more about how to sell their stories to Hollywood.

Published on May 26, 2017 00:00

May 25, 2017

Talk about a high-concept ... Rihanna and Lupita Nyong’o are set to star in a buddy movie for director Ava DuVernay after a tweet of the two went viral.

The Pitch: “Rihanna looks like she scams rich white men and lupita is the computer smart best friend that helps plan the scams.”

The Grammy-winning singer and Oscar-nominated actor were pictured together at a Miu Miu fashion show in 2014, which was then used as part of a meme movie pitch on Twitter in April.

Both stars then expressed interest in the idea via Twitter, followed by Selma director DeVernay and Insecure writer Issa Rae.

Nyong’o acknowledged the tweet about the potential film, writing, “I’m down if you are @rihanna.” Rihanna responded, “I'm in Pit’z.” After that, it was suggested that Ava DuVernay (Selma, 13th) and “Insecure” creator/star Issa Rae get involved. Both showed interest.

Now, the Rihanna and Lupita Nyong’o buddy film could soon become a reality. Netflix reportedly bought the rights to the movie during a bidding war at Cannes.

The Grammy-winning singer and Oscar-nominated actor were pictured together at a Miu Miu fashion show in 2014, which was then used as part of a meme movie pitch on Twitter in April.

Both stars then expressed interest in the idea via Twitter, followed by Selma director DeVernay and Insecure writer Issa Rae.

Nyong’o acknowledged the tweet about the potential film, writing, “I’m down if you are @rihanna.” Rihanna responded, “I'm in Pit’z.” After that, it was suggested that Ava DuVernay (Selma, 13th) and “Insecure” creator/star Issa Rae get involved. Both showed interest.

Now, the Rihanna and Lupita Nyong’o buddy film could soon become a reality. Netflix reportedly bought the rights to the movie during a bidding war at Cannes.

Published on May 25, 2017 13:44

May 24, 2017

R.I.P. Roger Moore

Published on May 24, 2017 08:50

May 22, 2017

Women in Hollywood The more you know ...

Sometimes when you’re having a conversation — let’s say about how women are treated in Hollywood — it can be hard to come up with anything but generalizations. Even though it’s completely accurate to say, “Women TV characters are usually white,” or, “Female directors aren’t getting the same opportunities as men,” sometimes you need a number to really drive your point home.

Below is a Women and Hollywood-created infographic that provides the need-to-know facts about women in the entertainment industry in 2017. After compiling data from academics and researchers, Women in Hollywood.com put together an on-the-go reference about women onscreen and off, from the big screen to television. We hope it’s helpful.

Below is a Women and Hollywood-created infographic that provides the need-to-know facts about women in the entertainment industry in 2017. After compiling data from academics and researchers, Women in Hollywood.com put together an on-the-go reference about women onscreen and off, from the big screen to television. We hope it’s helpful.

Published on May 22, 2017 00:00

May 20, 2017

Guest Post: Reading is bad for your eyes but... by Jerry Amernic

When Jean Chretien was Prime Minister of Canada he once said something about the country’s founding in 1864, but Canada became a country in 1867. Every Canadian knows that. Right? Well, apparently not. By the same token U.S. President Donald Trump isn’t exactly up on American history.

When Jean Chretien was Prime Minister of Canada he once said something about the country’s founding in 1864, but Canada became a country in 1867. Every Canadian knows that. Right? Well, apparently not. By the same token U.S. President Donald Trump isn’t exactly up on American history.His interview the other day with The Washington Post revealed that he doesn’t know why the Civil War took place and that Andrew Jackson was “really angry” about it. This is quite a stretch when you consider that Jackson died in 1845 and the Civil War began in 1861.

One week earlier Trump was interviewed by Reuters. In that one, he wondered why the Israelis and Palestinians have been fighting all these years.

“There is no reason there’s not peace between Israel and the Palestinians – none whatsoever,” he said.

Uh-huh.

Isn’t it important for world leaders to know a thing or two about history? One would think it should be a prerequisite for office. How can a world leader make informed decisions if he or she doesn’t know anything about the past?

Welcome to the brave new world of the 21st century. It’s a world where we have more information at our fingertips than ever before and people seem to know less than ever. Why? Here are a few reasons.

1. The education system is sadly lacking (I’m being generous when I say this).

2. There is so much choice out there, in terms of what information we want and how we get it, that many take the easy route. Put another way, in the old days you went to the library, but now you go to Wikipedia.

3. Extension of point no. 2 – There is so much choice and so little time that people, by and large, no longer read anything of substance.

A 1968 film called Charly with Cliff Robertson was about a man who is intellectually slow and who undergoes a medical procedure that makes him a genius. He is asked what was raising the standard of living (this was 1968) and he said: “A TV in every room.” Then he is asked about the current state of education and he said: “A TV in every room.”

Which is kind of where we are today, only worse. For the record, here are a few items from my bookshelf that I recommend to young people and current world leaders.

• The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William L. Shirer

• Infidel by Ayaan Hirsi Ali

• Roots by Alex Haley

• The Source by James A. Michener (a novel)

• Three Day Road by Joseph Boyden (another novel).

It’s only a beginning. But it’s something.

Jerry Amernic is a Canadian writer of fiction and non-fiction books. He is the author of the Holocaust-related novel 'The Last Witness' and the biblical-historical thriller 'QUMRAN'

Published on May 20, 2017 00:00

May 19, 2017

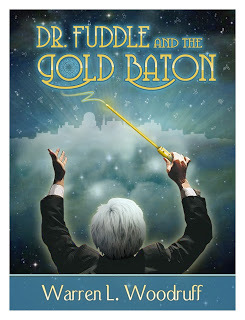

THE MUSIC MAN Turning children on to classical music

The Dr. Fuddle Music Scholarship has been officially established! This is the first step in moving forward with the goal of establishing tuition-free conservatories of music worldwide and The Dr. Fuddle Foundation for the Arts.

The Dr. Fuddle Music Scholarship has been officially established! This is the first step in moving forward with the goal of establishing tuition-free conservatories of music worldwide and The Dr. Fuddle Foundation for the Arts.

Dr. Warren Woodruff aka Dr. Fuddle shares his joy of classical music with children through scholarships and books.

Dr. Warren Woodruff aka Dr. Fuddle shares his joy of classical music with children through scholarships and books.Pianist, musicologist and author Dr. Warren Woodruff of Buckhead is a man on a mission: to instill a new generation with a love of classical music. A teacher for the last 30 years, he spreads his message wherever he goes and volunteers to help students with extraordinary talent.

In 2016, Woodruff endowed The Dr. Fuddle Music Scholarship to the Atlanta Music Club. The award was named after the hero of his children’s novels. Woodruff was instrumental in raising funds to develop a music therapy program at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta (CHOA), as well as helping the hospital’s Tower of Talent event raise more than $1 million.

“I’ve seen firsthand how transformative and healing classical music can be,” Woodruff says. “It gives children joy and carries them through tough times. The power of music is the most untapped resource on the planet.”

The Magic Piano, a play written by Woodruff, debuted in Atlanta in 1999 and was so well received that he expanded it into a fantasy novel and screenplay titled Dr. Fuddle and the Gold Baton. A sequel to the book, a feature film and toys will debut this year.

“In the story, children go to a magical land where the great composers live and learn how to solve real world problems through music and nonviolence,” Woodruff says.

Read more

For more information, visit drfuddle.com.

BY: Mickey Goodman

Photo: Tim Wilkerson Photography

Published on May 19, 2017 13:48

May 18, 2017

Great News for Indie Producers! Amazon Studios is bringing three award-winning indie production companies into the fold.

The company has signed exclusive first-look deals with Bona Fide Productions, Killer Films and Le Grisbi Productions, Variety has learned. The pacts put the streaming giant in business with the makers of such film classics as “Birdman” and “Far From Heaven.” They come just two weeks before the Cannes Film Festival where Amazon will be on hand to premiere Todd Haynes’ “Wonderstruck,” which Killer Films produced, and Lynne Ramsay’s “You Were Never Really Here.”

Bona Fide Productions is backed by Albert Berger and Ron Yerxa. The company is working with Amazon on Marc Webb’s “The Only Living Boy in New York,” a drama with Jeff Bridges, Callum Turner and Kate Beckinsale. Its credits include “Little Miss Sunshine” and “Nebraska.”

Related

Amazon Studios Variety Cover Story

Amazon, Retail Behemoth, Taking Smaller Steps Into Hollywood

Killer Films is the label of veteran producers Christine Vachon (pictured) and Pamela Koffler. In addition to “Wonderstruck,” which stars Julianne Moore, the company has produced “Still Alice,” “Carol,” and “Wiener-Dog” (an Amazon acquisition out of 2016’s Sundance Film Festival). The company also produced “Z: The Beginning of Everything,” a biography series about Zelda Fitzgerald, for Amazon’s original series arm.

Bona Fide Productions will have a first look deal and Killer Films will have an exclusive first-look deal in both film and television for two years.

Le Grisbi Productions is the shingle of John Lesher. Its credits include “Fury,” “Black Mass,” and “Birdman.” Upcoming releases include Scott Cooper’s “Hostiles,” a Western with Christian Bale and Rosamund Pike, and “White Boy Rick,” a crime drama with Matthew McConaughey and Jennifer Jason Leigh. The company will have an exclusive first-look deal for any “indie-sized” films it is making. The pact runs for two years.

Amazon has only been releasing movies theatrically for a little over a year, but it’s already made a splash, picking up three Oscars this year for “Manchester by the Sea” and “The Salesman,” as well as releasing movies from the likes of Woody Allen and Spike Lee. The deals are a sign that Amazon is increasingly interested in getting involved in films from their inception as opposed to simply acquiring completed films on the festival circuit. It’s also a signal of the company’s big ambitions. Like major studios, which routinely hand out production deals, it wants to forge enduring business relationships with top talent.

“Bona Fide Productions, Killer Films and Le Grisbi Productions each have a long history of making critically acclaimed and award-winning films with accomplished filmmakers,” said Roy Price, head of Amazon Studios in a statement. “We’re proud to be working with each of them and excited about our future creative collaborations.”

Read more

Published on May 18, 2017 00:00

May 16, 2017

Turn your book into a movie: 16 treatment tips by Kenneth Atchity

Turn your book into a movie: 16 treatment tips

By Kenneth Atchity

By Kenneth Atchity

Making a book into a film can cost producers anymore $1 million to $200 million, so this is clearly a major investment.

Talk to a story editor from any production company, studio, or agency “story department,” and they will tell you the weaknesses they see in novels submitted for film or television.

The story department’s report on the book’s potential for translation to film, referred to as “coverage,” is their feedback to the decision-making exec. It can make or break it for you — and it kills countless submissions.

The sad thing is, most writers will almost never even get as far as a coverage of their novel.

That’s often because of the book’s “treatment.”

What’s a treatment?A treatment is a relatively short, written pitch of a story intended for production as a motion picture or television program. Written in user-friendly, informal language and focused on action and events, it presents the story’s overall structure and primary characters. It presents three clear acts and shows how the characters change from beginning to end.

You can write a better treatment if you know about the typical weaknesses story editors find as they prepare each option’s “coverage” (see my book, Writing Treatments that Sell ). When you address these common weaknesses, you give your story a much better chance in the rooms where people decide whether, and how much, to spend on putting your story onto the screen.

). When you address these common weaknesses, you give your story a much better chance in the rooms where people decide whether, and how much, to spend on putting your story onto the screen.

Then you can use that treatment to market your story to Hollywood.

16 treatment tips that will help you turn your book into a movieHere are 16 things to know about what your treatment needs to include.

1. Make sure your primary characters are relatable (that’s also called sympathetic).

If we can’t relate to them, we don’t feel for them. This addresses the comment: “I can’t relate to anyone in the book.”

2. Trim the number of characters way back so the treatment’s reader isn’t boggled by the immensity of the cast.

Also, keep the treatment focused as much as possible on the protagonist (and his or her love interest and/or ally) and antagonist. Comment: “There are way too many characters, and it’s not clear till page 200 who the protagonist is.”

3. Build a strong protagonist in the 20 to 50 star age range, one we want to root for.

Comment: “We don’t know who to root for.”

4. Make sure your hero or heroine takes action based on his or her motivation and mission, and forces others in your story to react.

Comment: “The protagonist is reactive, instead of proactive.”

5. Offer a new twist in your story even if it’s a familiar story to avoid the comment: “There’s nothing new here.”

6. Write it so the story editor reading your treatment can see three well-defined acts: act one (the setup), act two (rhythmic development, rising and falling action), and act three (climax, leading to conclusive ending).

Comment: “I can’t see three acts here.”

7. Make sure the turning point into the third act of your story is well-marked with a major twist that takes us there.

Comment: “There’s no Third Act…it just trickles out.”

8. Create a well-pronounced theme for your story (sometimes called “the premise”) in the treatment, so that the reader (audience) walks away with the feeling they’ve learned something important.

Comment: “At the end of the day, I have no idea what this story is about.”

9. Be sure there’s plenty of action in your story.

Action means dramatic action, of which there are two kinds: action and dialogue. Action is obvious:

She slams the door in his face.The bullets find their target, and he slumps in his chair.The second plane crashes into the Pentagon.But good dialogue is also action:“Would you do something for me now?”“I’d do anything for you.”“Would you please please please please please please please stop talking?” (Hemingway, “Hills like White Elephants”)

10. Sprinkle character-revealing dialogue throughout, enough to let the reader know what your characters sound like—and that they all sound different.

Comment: “There’s no dialogue, so we don’t know what the characters sound like.”

11. Make sure the plot is hidden not overt, dropping clues act by act so the audience can foresee its possible outcomes.

Comment: “At the end, the antagonist lays out the entire plot to the protagonist before he’s killed.”

12. Ruthlessly go through your treatment and remove anything that even hints of contrivance.

The audience will allow any story one gimme, but rarely two, and never three, before they lose their belief. Everything needs to be grounded in the story’s integrity.

Comment: “The whole thing is overly contrived.”

13. Make it well-paced, with rising and falling action, twists and turns, cliffhangers ending every act, etc.

Comment: “There is no real pacing.”

14. Be able to pitch your story in a single punch line (aka “logline”), and put that line at the beginning of your treatment in bold face:

She’s a fish out of water—but she’s a mermaid (“The Little Mermaid,” “Splash”).He’s left behind alone. On Mars (“The Martian”).An inventor creates an artificial woman who’s so real she turns the table on her creator, locks him up, and escapes (“Ex Machina”).

This is also called “the high concept,” which means it can be pitched simply—on a poster or to a friend on the phone.

Comment: “How do we pitch it? There’s no high concept.”

15. Make sure your story feels like a movie, which includes taking us to places we’ve probably never been, or rarely been.

A movie transports us to locations we want to feel, like Antarctica, or the Amazon jungle, or a moon of Saturn, or, in movies I’ve done, a brothel in New Orleans (The Madams Family), the experimental lab of the inventor of the vibrator in Victorian England (Hysteria), a mountain cabin during a blizzard (Angels in the Snow), or the Amityville house in Long Island (Amityville: The Evil Returns).

Comment: “There are no set pieces, so it doesn’t feel like a movie.”

16. Get someone who knows the industry well to read your treatment and give you dramatic feedback on it before you send it out.

Comment: “The writer shows no knowledge of movies!”

Of course anyone with the mind of a sleuth can list films that got made despite one or more of these comments being evident. But for novelists frustrated at not getting their books made into films, that’s small consolation.

If you regard your career as a business instead of a quixotic crusade, plan your novel’s treatment to make it appealing to filmmakers–and to avoid the story department’s buzz-killing comments.

Read more

By Kenneth Atchity

By Kenneth AtchityMaking a book into a film can cost producers anymore $1 million to $200 million, so this is clearly a major investment.

Talk to a story editor from any production company, studio, or agency “story department,” and they will tell you the weaknesses they see in novels submitted for film or television.

The story department’s report on the book’s potential for translation to film, referred to as “coverage,” is their feedback to the decision-making exec. It can make or break it for you — and it kills countless submissions.

The sad thing is, most writers will almost never even get as far as a coverage of their novel.

That’s often because of the book’s “treatment.”

What’s a treatment?A treatment is a relatively short, written pitch of a story intended for production as a motion picture or television program. Written in user-friendly, informal language and focused on action and events, it presents the story’s overall structure and primary characters. It presents three clear acts and shows how the characters change from beginning to end.

You can write a better treatment if you know about the typical weaknesses story editors find as they prepare each option’s “coverage” (see my book, Writing Treatments that Sell

). When you address these common weaknesses, you give your story a much better chance in the rooms where people decide whether, and how much, to spend on putting your story onto the screen.

). When you address these common weaknesses, you give your story a much better chance in the rooms where people decide whether, and how much, to spend on putting your story onto the screen.Then you can use that treatment to market your story to Hollywood.

16 treatment tips that will help you turn your book into a movieHere are 16 things to know about what your treatment needs to include.

1. Make sure your primary characters are relatable (that’s also called sympathetic).

If we can’t relate to them, we don’t feel for them. This addresses the comment: “I can’t relate to anyone in the book.”

2. Trim the number of characters way back so the treatment’s reader isn’t boggled by the immensity of the cast.

Also, keep the treatment focused as much as possible on the protagonist (and his or her love interest and/or ally) and antagonist. Comment: “There are way too many characters, and it’s not clear till page 200 who the protagonist is.”

3. Build a strong protagonist in the 20 to 50 star age range, one we want to root for.

Comment: “We don’t know who to root for.”

4. Make sure your hero or heroine takes action based on his or her motivation and mission, and forces others in your story to react.

Comment: “The protagonist is reactive, instead of proactive.”

5. Offer a new twist in your story even if it’s a familiar story to avoid the comment: “There’s nothing new here.”

6. Write it so the story editor reading your treatment can see three well-defined acts: act one (the setup), act two (rhythmic development, rising and falling action), and act three (climax, leading to conclusive ending).

Comment: “I can’t see three acts here.”

7. Make sure the turning point into the third act of your story is well-marked with a major twist that takes us there.

Comment: “There’s no Third Act…it just trickles out.”

8. Create a well-pronounced theme for your story (sometimes called “the premise”) in the treatment, so that the reader (audience) walks away with the feeling they’ve learned something important.

Comment: “At the end of the day, I have no idea what this story is about.”

9. Be sure there’s plenty of action in your story.

Action means dramatic action, of which there are two kinds: action and dialogue. Action is obvious:

She slams the door in his face.The bullets find their target, and he slumps in his chair.The second plane crashes into the Pentagon.But good dialogue is also action:“Would you do something for me now?”“I’d do anything for you.”“Would you please please please please please please please stop talking?” (Hemingway, “Hills like White Elephants”)

10. Sprinkle character-revealing dialogue throughout, enough to let the reader know what your characters sound like—and that they all sound different.

Comment: “There’s no dialogue, so we don’t know what the characters sound like.”

11. Make sure the plot is hidden not overt, dropping clues act by act so the audience can foresee its possible outcomes.

Comment: “At the end, the antagonist lays out the entire plot to the protagonist before he’s killed.”

12. Ruthlessly go through your treatment and remove anything that even hints of contrivance.

The audience will allow any story one gimme, but rarely two, and never three, before they lose their belief. Everything needs to be grounded in the story’s integrity.

Comment: “The whole thing is overly contrived.”

13. Make it well-paced, with rising and falling action, twists and turns, cliffhangers ending every act, etc.

Comment: “There is no real pacing.”

14. Be able to pitch your story in a single punch line (aka “logline”), and put that line at the beginning of your treatment in bold face:

She’s a fish out of water—but she’s a mermaid (“The Little Mermaid,” “Splash”).He’s left behind alone. On Mars (“The Martian”).An inventor creates an artificial woman who’s so real she turns the table on her creator, locks him up, and escapes (“Ex Machina”).

This is also called “the high concept,” which means it can be pitched simply—on a poster or to a friend on the phone.

Comment: “How do we pitch it? There’s no high concept.”

15. Make sure your story feels like a movie, which includes taking us to places we’ve probably never been, or rarely been.

A movie transports us to locations we want to feel, like Antarctica, or the Amazon jungle, or a moon of Saturn, or, in movies I’ve done, a brothel in New Orleans (The Madams Family), the experimental lab of the inventor of the vibrator in Victorian England (Hysteria), a mountain cabin during a blizzard (Angels in the Snow), or the Amityville house in Long Island (Amityville: The Evil Returns).

Comment: “There are no set pieces, so it doesn’t feel like a movie.”

16. Get someone who knows the industry well to read your treatment and give you dramatic feedback on it before you send it out.

Comment: “The writer shows no knowledge of movies!”

Of course anyone with the mind of a sleuth can list films that got made despite one or more of these comments being evident. But for novelists frustrated at not getting their books made into films, that’s small consolation.

If you regard your career as a business instead of a quixotic crusade, plan your novel’s treatment to make it appealing to filmmakers–and to avoid the story department’s buzz-killing comments.

Read more

Published on May 16, 2017 00:00

May 15, 2017

Story Merchant Books May Amazon eBook Deals!

FREE May 16 - 20!

American Pathfinder (Pathfinders Series Book 1) by Frank Mitchell

In April of 1798, Napoleon appoints Lieutenant Charles MacDonald, a nineteen-year-old graduate geographical engineer, to be the pathfinder for his personal Brigade of Guides during the invasion of Egypt.

www.amzn.com/B01E9D14QC

FREE May 18 - 22!

FREE May 18 - 22!Karling Abbeygate's Debut Horror Novel The Fly King

Deft of wit and wicked as hell, Karling Abbeygate's The Fly King is a seductive and sinister debut.

--Richard Christian Matheson

Rachel lives a mundane life in Chicago. She doesn't know she has a murderous brother living in the slums of East London who is coming for her. She doesn't know about the ancient curse of the Fly King or the unthinkable events about to take place. What she does know is that she's being inexplicably drawn clear across country to a desolate little town in the wooded mountains of Washington and that her boyfriend Gavin is not happy about it.

www.amzn.com/B01N2MM3DO

FREE May 23 - 27!

FREE May 23 - 27!Assassins Don't Die In Bed by Michael Avallone, An Ed Noon Mystery

Ed Noon is the detective who reports directly to the President. He's got a dead man's job - play body shield to the VIP who mustn't know he's marked for murder!

www.amzn.com/B000V84656

Second Chances by Jeffrey Schiller

Second Chances by Jeffrey Schiller FREE May 25 - 29!

Set against the backdrop of a sport awash in billion dollar television contracts, multi-million dollar salaries for coaches and professional players, and kickbacks to agents and boosters, Second Chances explores the consequences of a corrupt and secretive culture where everyone is susceptible to the lure of fame and fortune…and also to the threat that their secrets and machinations will be revealed.

www.amzn.com/B015DFZ6ZA

FREE May 29 - June 2

FREE May 29 - June 2 Dragon Heart by Linda A. Malcor

There is a scrap of a boy who dreams of riding a dragon, but he feels his dreams are far away, especially in the land of Drumnonia where there are dragons, riders, AND demons, gods, and elves. In the end, he becomes a dragon rider, and not just an ordinary rider either: he is the Dragonheart!

www.amzn.com/B01AAZ1SZA

Published on May 15, 2017 00:00

May 14, 2017

What is “Coverage” and How Does It Affect Whether My Book Sells to Hollywood? by Kenneth Atchity

I read part of it all the way through.—Samuel Goldwyn

The Hollywood decision-maker who receives your story submission rarely has time to read it him- or herself. They assign it “for coverage” to the story department, and receive back a coverage. “Coverage” is the term used in Hollywood for the document that determines the fate of most story submissions. It’s a document, created by a story editor, in the story department of an agency, production company, studio, or broadcaster that analyzes your story’s film-worthiness. A typical coverage includes a “grading system” something like the following that suggests that the submission (screenplay, novel, nonfiction book, or treatment) is:

PASS— Nothing to spend more time on. So the executive who receives this recommendation returns the submission.

RECOMMEND— The grade you’re looking for. The executive reads at least part of the submission and, if he agrees with his story editor, contacts the writer to ask about its rights status.

RECOMMEND, W/DEVELOPMENT— Don’t let this one go, but it’s not perfect and needs fixing.

CONSIDER— The story editor isn’t sure. Usually this grade leads to a “second read,” from a different story editor.

CONSIDER, WITH DEVELOPMENT— Meaning it’s worth taking on for development, but not yet ready for production. In many cases this will lead to a pass because most companies are so swamped with production and development projects that they simply have no bandwidth for developing another one.

Sometimes an additional category might be included:

KEEP AN EYE ON THE WRITER? That’s a Yes, or No.

The coverage typically contains a number of analytical sections to make sure all aspects of the project are addressed:

The coverage typically contains a number of analytical sections to make sure all aspects of the project are addressed:TITLE and GENRE: The title of the submission is followed by a statement of what genre it falls into: Fantasy/Adventure, Action, Romance, Drama, Horror, Thriller, Comedy, True Story, etc.

TYPE: Screenplay? Manuscript? Nonfiction? Novel? Treatment?

LOGLINE: This is a one- or two-sentence summary of the story, sometimes referred to as the pitch-line. The best are the shortest: “A man is mistakenly left behind when his ships leaves in a hurry. On Mars.”

SYNOPSIS— This is a straightforward outline of your story, to give the executive an overview of what happens in it. It describes all main plot points and details necessary to understand the story. The preferred length of a synopsis is a page or two. When it’s longer, it’s usually a sign to the executive that the story is too complicated to make a good film.

MARKET POTENTIAL— This section is a comment on the audience the project is aimed at, and whether the story editor feels it fits that market or departs from its needs or expectations, whether it’s a fresh approach to an important story, whether the story is “elevated” by its theme to make it a worthy film or series. Often names successful films that resemble this one.

STRUCTURE— This is an overall comment on how well the structure of the story holds together and accomplishes its purpose, but also where it falters in doing so. Do events unfold cohesively? Are plot points used effectively? Does the story reveal a three-act structure? A typical comment, “There seems to be repetition of the same events over and over again throughout the story.”

CONFLICT— This crucial section indicates whether there is sufficient conflict, both external (in the events of the story) and internal (within the characters). Is the main external conflict of sufficient formidable force to hold audiences? Is it supported by smaller external conflicts, as well as by internal conflict on the part of the characters, especially protagonist and antagonist?

CHARACTER— Is the protagonist fully formed? Do we care about Does he or she have a back story, a mission, and does he or she experience change by the end? Are the supporting characters strong?

DIALOGUE— Is the dialogue unique to each character or do they all sound the same? Does the dialogue move the story along, providing information and containing subtext without being on-the-nose or unbelievable?

PACING— Are scenes or events an appropriate length for their purpose? Is there a sense of build-up, a balance between tension and release, mystery and discovery? Sufficient twists and turns, cliffhangers and surprises? Does each scene or event depend on what came before?

LOGIC— This section talks about plot holes or points lacking sufficient clarity? Do events make sense within the world of the story? For example, do science fiction and fantasy worlds remain consistent with their own set of rules?

CRAFT— Is the writing itself clear, concise, and descriptive? Is there an even balance of action and dialogue? Is proper formatting employed? Are there spelling or grammatical errors?

Yeah, it’s pretty thorough, isn’t it? And here’s the catch: the writer who submitted the story will rarely see the coverage that determines its fate. It’s a real philosophical dilemma. Given that the coverage is so important, and that you won’t see it, how should you behave?

The answer is to know that the coverage, like the troll under the bridge, is there lurking in wait for you–and to disarm it in advance by making sure your story addresses all the categories of expectation.

If, in its current form, it does not, write a treatment of your story and submit that instead.

About Sell Your Story to Hollywood:

Through the expanding influence of the Internet and the corporatization of both publishing and entertainment, the process of getting your book to the big screen has gotten more complicated, more eccentric, and more exciting.

Through the expanding influence of the Internet and the corporatization of both publishing and entertainment, the process of getting your book to the big screen has gotten more complicated, more eccentric, and more exciting.This little book aims to help you figure out how to get your story told on big screens or small. It’s not going to give you rules and regulations, because they simply don’t exist today. Any rule that could be promulgated has and will be broken. What this book offers instead is nearly thirty years of observation of how things happen in show business, the business of entertainment (better known around the world as Hollywood). Dr. Ken Atchity’s Hollywood experience ranges from writing to managing writers to producing their movies for television and theaters. He’s seen the Hollywood story market from nearly every angle, including legal and business affairs.

Ken Atchity spent his first career as a professor, a career he embarked upon innocently because he wanted to focus his efforts on understanding stories and helping writers get their stories told—and here he is thirty years later still pursuing the same goal—because it’s a worthy and never-ending goal.

He’s made films based on nonfiction books, and made deals for a number of nonfiction stories. But most of his experience lies in turning novels into films. As a lifelong story merchant, what Dr. Atchity develops and sells are “stories,” because he believes stories rule the world. Many of the observations outlined in this book are simply about selling stories to Hollywood.

This pocket guide will help you expedite the transformation of your show business dreams into realities.

Order your copy online here.

Published on May 14, 2017 00:00