Kenneth Atchity's Blog, page 115

July 26, 2018

July 24, 2018

Molly Wood Interviews Steve Alten On Pittsburgh's NPR

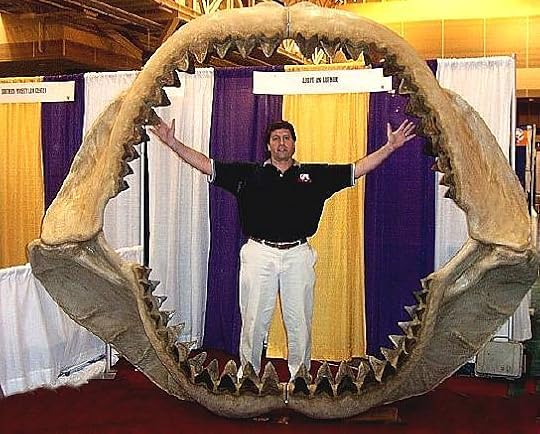

So long as sharks are terrifying, there will be shark content

In 1975, "Jaws" became the first movie to gross over $100 million. Its success made it the first summer blockbuster. This summer's shark offering is "The Meg," a story about Carcharodon megalodon, the largest shark that ever lived. The movie is based on a novel written by Steve Alten, who saw "Jaws" when it came out and became obsessed with sharks. It turned out to be a lucrative obsession — sharks are a moneymaker. See: "Jaws." And also Shark Week, starting up again this weekend, which launched in 1988 and is arguably the Discovery Channel's most lucrative annual event. Plus, there's a sixth "Sharknado" movie coming on Syfy in August. Alten's written six books on the meg — the latest drops this week on his website — and he talked to Marketplace host Molly Wood about his relationship to the giant, extinct shark. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Molly Wood: So you have essentially made an entire career out of shark stuff, so to speak. What is it about sharks that captivated you? What's your personal connection to the Megalodon story?

Steve Alten: Well, it sort of started when I was 15 and saw "Jaws" in theaters. And that got me to read Peter Benchley's book, and then I started reading everything I could find on great whites, true-life attack stories ... and there was always a little blurb about Carcharocles megalodon, the prehistoric cousin of the great white. Well, flash ahead 20 years and I'm 35 years old, struggling to support a family of five, and I happened to pick up a Time magazine article in August of '95 that featured the Mariana Trench, [once] the deepest part [of] the ocean. And the article talked about hydrothermal vents and life at the bottom of the ocean. And I thought, "You know, this would be a pretty cool place for that shark that I read about when I was younger to be hanging out. I wonder if it would be scientifically feasible." So I went to the library and did some research — because there was no internet back then — and found out that it was feasible and that there was a big mystery about how these sharks disappeared. And I thought, "You know, I think I'm going to write the book."

Wood: Why do you think that shark material, you know, from "Jaws" to Shark Week, now likely to this franchise, why is it such a consistent moneymaker?

Alten: Well, I mean, people like to be scared in the movies. And sharks are scary creatures, and great whites are the scariest of them all. Except for the megalodon, the big great white. So I think this movie is going to up the ante on it. But if it's done well, then it can make for a movie that people want to see over and over again.

Wood: You mention the science aspect and that you did the research to see if it would actually be possible. Which, thank you for verifying my absolute worst fear: that the megalodon might be down there.

Alten: Well, are you planning a trip to the Mariana Trench anytime soon?

Wood: It's going to come out! I already saw it in the trailer. So you mentioned the scientific aspect. A lot of criticism even of, for example, Shark Week and "Jaws" is that it's not always very scientifically based and ends up demonizing sharks. Do you worry about that? Or does this have an answer to that?

Alten: Well, if you read the books, you'll see that I'm very much into the ecology of the ocean and protecting sharks, and, in fact, in the book, they're trying to capture it, not trying to kill it. But, you know, back when Benchley wrote "Jaws," he got a lot of grief and felt horrible because sharks were being killed, you know, after "Jaws." I think we've woken up to the fact that sharks are an integral part of the ocean's ecology and health. And this ridiculous practice of killing these sharks for their fins to make soup, it's just got to stop. And I will assure you that no megalodons were hurt in the filming of this movie.

Read more

In 1975, "Jaws" became the first movie to gross over $100 million. Its success made it the first summer blockbuster. This summer's shark offering is "The Meg," a story about Carcharodon megalodon, the largest shark that ever lived. The movie is based on a novel written by Steve Alten, who saw "Jaws" when it came out and became obsessed with sharks. It turned out to be a lucrative obsession — sharks are a moneymaker. See: "Jaws." And also Shark Week, starting up again this weekend, which launched in 1988 and is arguably the Discovery Channel's most lucrative annual event. Plus, there's a sixth "Sharknado" movie coming on Syfy in August. Alten's written six books on the meg — the latest drops this week on his website — and he talked to Marketplace host Molly Wood about his relationship to the giant, extinct shark. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Molly Wood: So you have essentially made an entire career out of shark stuff, so to speak. What is it about sharks that captivated you? What's your personal connection to the Megalodon story?

Steve Alten: Well, it sort of started when I was 15 and saw "Jaws" in theaters. And that got me to read Peter Benchley's book, and then I started reading everything I could find on great whites, true-life attack stories ... and there was always a little blurb about Carcharocles megalodon, the prehistoric cousin of the great white. Well, flash ahead 20 years and I'm 35 years old, struggling to support a family of five, and I happened to pick up a Time magazine article in August of '95 that featured the Mariana Trench, [once] the deepest part [of] the ocean. And the article talked about hydrothermal vents and life at the bottom of the ocean. And I thought, "You know, this would be a pretty cool place for that shark that I read about when I was younger to be hanging out. I wonder if it would be scientifically feasible." So I went to the library and did some research — because there was no internet back then — and found out that it was feasible and that there was a big mystery about how these sharks disappeared. And I thought, "You know, I think I'm going to write the book."

Wood: Why do you think that shark material, you know, from "Jaws" to Shark Week, now likely to this franchise, why is it such a consistent moneymaker?

Alten: Well, I mean, people like to be scared in the movies. And sharks are scary creatures, and great whites are the scariest of them all. Except for the megalodon, the big great white. So I think this movie is going to up the ante on it. But if it's done well, then it can make for a movie that people want to see over and over again.

Wood: You mention the science aspect and that you did the research to see if it would actually be possible. Which, thank you for verifying my absolute worst fear: that the megalodon might be down there.

Alten: Well, are you planning a trip to the Mariana Trench anytime soon?

Wood: It's going to come out! I already saw it in the trailer. So you mentioned the scientific aspect. A lot of criticism even of, for example, Shark Week and "Jaws" is that it's not always very scientifically based and ends up demonizing sharks. Do you worry about that? Or does this have an answer to that?

Alten: Well, if you read the books, you'll see that I'm very much into the ecology of the ocean and protecting sharks, and, in fact, in the book, they're trying to capture it, not trying to kill it. But, you know, back when Benchley wrote "Jaws," he got a lot of grief and felt horrible because sharks were being killed, you know, after "Jaws." I think we've woken up to the fact that sharks are an integral part of the ocean's ecology and health. And this ridiculous practice of killing these sharks for their fins to make soup, it's just got to stop. And I will assure you that no megalodons were hurt in the filming of this movie.

Read more

Published on July 24, 2018 00:00

July 22, 2018

Guest post: IRRATIONAL FEARS by Lee Lindauer

by Lee Lindauer. International action / math thriller. (May 2018)

by Lee Lindauer. International action / math thriller. (May 2018)After witnessing the horrifying murder of her friend Tom Haley, Mallory Lowe, a cautious university mathematics professor, must emerge from her cocoon to become the gutsy and unpredictable woman she’s always dreamed of being. Running on the guilt of a past family tragedy that she blames on herself, Mallory is determined to find Tom’s now-missing daughter.Hard Math, Easy Read: Using a math-based plot to tell a great storyGuest post by Lee LindauerWhen I set out many years ago with the crazy idea to be a fiction writer, one of the first items on the agenda was to create a protagonist, one that was unique, multi-dimensional and complex. After my first novel, I realized my main protagonist was flat, a one-dimensional person I had a hard time fleshing out. What I needed was a protagonist that had a little bit of my interests and background. Having had a career in engineering, I decided to zero in on a protagonist who found math and science exciting. I settled on math. Mathematics is definitely an area that all engineers must experience during their college years. I then had an epiphany—this mathematician protagonist should be a woman—unique and complex—someone who goes against the perception that all math geeks are men. Thus the next three novels I wrote included Mallory Lowe, a tenured university mathematics professor. The third of these novels is titled IRRATIONAL FEARS, and can be found at Amazon.com.

Following the clues in a 300-year-old equation left by Tom, Mallory’s search propels her into the tangled threads of a ruthless corporate entity known as Möbius, bent on controlling the world’s most precious resource: fresh water. Mallory is propelled along a perilous journey from the southwest United States through the breathtaking landscape of Switzerland and into the inner workings of a massive hydroelectric dam in Turkey. She solves the riddle of the centuries old mathematics equation—only to discover something more ominous and deadly in the process.

Science in novels is not unique. Readers of ScienceThrillers.com will attest to that. What about mathematics? There have been several novels with mathematicians (crazy, brilliant, or both) written with themes centering on mathematical philosophies such as Neal Stephenson’s Anathem. The trouble with writing about math in novels is the misconception that the reader is not math-worthy—a reader who cringes when it comes to discussing mathematical concepts. These are people who hated math in school or feared it since it held an overbearing abstraction for them.

The key then was to write a math-centric novel that keeps the reader’s attention. Mathematical concepts must be written such that the layman should not be intimidated by them. This can be a tough chore, but one I believe can also be self-gratifying if the author can pull it off.

In IRRATIONAL FEARS, the plot revolves around a 300 year-old equation, THE BASEL PROBLEM, a very unique infinite series:

1 + 1/22 + 1/32 + 1/42 + 1/52 + 1/62 + … + 1/k2 + … = π2/6

The summation of reciprocals of squares on the left equals the odd π2/6 on the right. The more terms on the left that are added, the closer to the answer on the right—a subliminal relationship of inverse squares to circles. This is a fascinating problem in number theory, but the reader may ask, okay, I think I understand it, so what? Why is this important? No spoiler here. Read IRRATIONAL FEARS to find out why.

Let’s not forget—mathematics is the language of science. Let’s take for example, the constant e which equals 2.71828… Where does this seemingly non-descript number come from? In mathematical jargon, e =

In other words if n= 10, then e= 2.59374246… If n=1,000,000,000, then e = 2.71828183… As n approaches infinity, then e approaches a limit, that being the number e = 2.71828183… Why is e so important? Let’s talk finance. Bankers love e because it is the background of compound interest, and they love nothing more than charging you interest on a loan. In the scientific arena, e pops up in a variety of ways—determining population growth in humans, or in bacteria, in depletion of tuna fisheries, and so forth. And in physics e is used to calculate time frames of radioactive decay, in heat transfer phenomena, and shows up in all types of waves—light, sound, etc.

So when mathematical concepts pop up in fiction, don’t be intimidated. They are there to drive the plot. Don’t get hung up on equations and don’t get frustrated.

A good writer will assure the reader will not feel pressured to understand each math concept. The unsuspecting reader will then have fun.

“A smashing debut, Irrational Fears is an action-packed, globetrotting adventure, and Lee Lindauer is the heir apparent to adventure thrillers.” —Anthony Franze, author of The Outsider

“Irrational Fears weaves age-old mathematics and the world’s most essential resource with unique characters and unrelenting tension.”—Bob Mayer, NYT bestselling author

Support ScienceThrillers.com and the author by ordering Irrational Fears from amazon.com or Barnes and Noble

About the Author:

Lee Lindauer has a BS in Architectural Engineering and a MS in Civil Engineering and was a principal of a consulting structural engineering firm he founded in Western Colorado. It is hard to say what got him into writing but after thirty-some years of consulting, he decided a new diversion would be welcome. Thus, the writing bug took over. In 2009, he retired. When he’s not punching a keyboard, he takes advantage of the amazing public spaces that the West has to offer (he is a Colorado native), from camping, rafting, hiking (try Angel’s Landing in Zion National Park), to lazily enjoying the sunset as it drapes the ragged peaks of the San Juan Mountains in various shades of crimson (beer in hand, of course).

Lee Lindauer has a BS in Architectural Engineering and a MS in Civil Engineering and was a principal of a consulting structural engineering firm he founded in Western Colorado. It is hard to say what got him into writing but after thirty-some years of consulting, he decided a new diversion would be welcome. Thus, the writing bug took over. In 2009, he retired. When he’s not punching a keyboard, he takes advantage of the amazing public spaces that the West has to offer (he is a Colorado native), from camping, rafting, hiking (try Angel’s Landing in Zion National Park), to lazily enjoying the sunset as it drapes the ragged peaks of the San Juan Mountains in various shades of crimson (beer in hand, of course).Read more

Published on July 22, 2018 00:00

July 21, 2018

‘The Meg’ – An outrageously fun, pulse-pounding thrill ride

Something very big is about to rise from the ocean’s unfathomable depths to seriously rock Warner Bros. Pictures’ new sci-fi action thriller “The Meg.”

That very big something is the titular creature – a 75-foot-long prehistoric shark – in “The Meg,” a pulse-pounding thrill ride and outrageously fun movie event that combines action and humor and pits action superstar Jason Statham in a head-to-head battle with a mammoth megalodon.

Large-scale action is familiar territory to director Jon Turteltaub, who previously helmed blockbuster adventures like “National Treasure” and “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.”

The Meg — or, to give it its full name, Carcharocles megalodon — was a species of shark that lived on seals, giant turtles and whales until its extinction around 2.6 million years ago. It was a true monster, so huge it would have made the great white in Steven Spielberg’s seminal summer movie “Jaws” look like a minnow. It certainly captured the imagination of author Steve Alten, who wrote a science-fiction novel that envisioned the return of such a creature to modern-day waters, published in July 1997 as Meg: A Novel of Deep Terror. It was a success, and five sequels followed.

Instrumental in getting “The Meg” made into an event motion picture was producer Belle Avery, who after reading the novel instantly thought: “This is a great popcorn movie. People like to go see monster movies, but if those monsters are real creatures that actually existed, I think you’re much more ahead of the game, because people want to go and see what they looked like.”

Deciding what the Meg looked like was not quite as straightforward as you might imagine. “One school of thought was to make it look like a 75-foot-long great white,” says Turteltaub. “Because when you look at a great white, an audience instantly goes, ‘Uh oh!’ And a 75-foot ‘Uh oh!’ is pretty scary. But, I wanted to create a shark that was a little less developed, a little less perfect, a little uglier and more specific to what life might have been like deep in the ocean three million years ago.”

The novel theorized that megalodons could have survived extinction by moving to the warmer, high-pressure depths of ocean-floor ravines like the Mariana Trench. And in this movie, it is in such an abyss that the terrifying Meg is discovered by a high-tech Chinese deep-sea exploration operation named Zhang Oceanic, overseen by Li Bingbing’s character, Suyin. It won’t be long before the Meg finds its way back up to the surface waters, which are now filled with a tasty new snack: humanity.

For Turteltaub, the appeal was to sink his teeth into “an entire movie genre I’d never worked in. I get to play in a whole new sandbox, so to speak, with a whole bunch of different movie rules. I like the pure fun of it. And I also like the challenge of making a Jason Statham action movie with no car chases, no fist fights or guns,” he adds with a laugh.

“Jerry Bruckheimer warned me about making undersea movies,” says Turteltaub, referring to his producer on the “National Treasure” movies and “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” who had plenty experience of his own filming on water with the “Pirates of The Caribbean” movies. “As soon as you go underwater, everything moves very slowly and is not conducive to action. I’ve had Jerry’s voice in my head the whole time, ready to say, ‘I told you so’. So, we had to work out how to keep things exciting with that challenge. And the way to do that was to mix up what’s underwater and what isn’t, while also building on the element of surprise and playing on what you can’t see. At any moment something really, really scary can happen. And that keeps the audience on edge.”

Diving into Philippine cinemas nationwide August 8, The Meg will be released in 2D, 3D and 4D in select theaters, as well as in IMAX, Dolby Cinema, and other large premium formats. The film is distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures, a Warner Entertainment Company.

About “The Meg”

In the film, a deep-sea submersible—part of an international undersea observation program—has been attacked by a massive creature, previously thought to be extinct, and now lies disabled at the bottom of the deepest trench in the Pacific…with its crew trapped inside. With time running out, expert deep sea rescue diver Jonas Taylor (Jason Statham) is recruited by a visionary Chinese oceanographer (Winston Chao), against the wishes of his daughter Suyin (Li Bingbing), to save the crew—and the ocean itself—from this unstoppable threat: a pre-historic 75-foot-long shark known as the Megalodon. What no one could have imagined is that, years before, Taylor had encountered this same terrifying creature. Now, teamed with Suyin, he must confront his fears and risk his own life to save everyone trapped below…bringing him face to face once more with the greatest and largest predator of all time.

Rounding out the international main cast of “The Meg” are Rainn Wilson, Ruby Rose, Winston Chao, Page Kennedy, Jessica McNamee, Ólafur Darri Ólafsson, Robert Taylor, Sophia Shuya Cai, Masi Oka and Cliff Curtis.

Read more

Published on July 21, 2018 00:00

July 19, 2018

Film Courage: Quit Your Day Job and Live Out Your Dreams by Dr. Ken Atchity

Published on July 19, 2018 00:00

July 18, 2018

The Last Five Great Video Stores in Los Angeles

My journey to find the last great video store began at Cinefile Video in West Los Angeles. Even in LA, finding video stores in 2018 is harder than one might imagine — a number of stores like Video West and the last remaining Blockbusters have closed in the six years since I moved here, and information on what’s still open and functional isn’t always the best. But I’d visited Cinefile before, and was eager to check it out again.

In terms of curation, Cinefile can’t be beat. They have the most interesting director’s section I’ve ever seen — filmmakers like Martha Coolidge, Alan Rudolph, Bill Gunn, Ida Lupino, and Ed Wood are given an equal spotlight within. By presenting viewers with a director’s entire oeuvre, Cinefile makes it easy for renters to find their own personal entry point into a particular filmography. And Cinefile’s uniquely curated sections — Nunsplotation, Holiday Horror, Private Dicks, Southern Discomfort, and Cannibals were just a few of offerings the day I was there — help customers explore even the most niche genres.

Cinefile also highlights subgenres like made-for-TV movies, filmed plays, and musical documentaries that would get overlooked by lesser video stores. This is also precisely the kind of material that never makes it to streaming — Cinefile’s dedication to showcasing this work is not only exciting from a customer’s point of view, but essential from a preservationist’s.

An endcap section at Cinefile

I was the only person in Cinefile the Thursday I visited them, and it was tough not to get a little disheartened by the lack of traffic in the store. But, when I visited a few months later, after 11PM on a Friday night, the store was bustling with activity, patrons eager to check out titles before a long weekend. Cinefile showcases some fantastic memorabilia within the store too — velvet paintings, tchotchkes, and rare promo images line the walls, adding to the ambiance of a visit.

For buyers, a hearty stock of DVDs were on sale for 50% off, and VHS tapes were selling for a quarter. Cinefile’s signature auteur-directors-as-metal-bands shirts were also well-stocked alongside tote bags featuring filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard and Jim Jarmusch. Cinefile is an excellent option for film fans on LA’s west side — yearly, monthly, and pay-as-you go memberships are available to best suit your personal rental needs.

Cinefile Video, 11280 Santa Monica Blvd., Los Angeles, CA, 90025. Sunday-Thursday, 11AM-11PM, Friday-Saturday, 11AM-12AM. $5 pay as you go rentals; $30 monthly membership for four rentals at a time; $330 yearly membership — all memberships come with perks like 10% off American Cinematheque memberships.

Vidéothèque

For my second visit, I headed east to Vidéothèque. Immediately, I was struck by how vital Vidéothèque felt among a strip of other small businesses — it’s clearly a community hub for South Pasadena. Like Cinefile, Vidéothèque is all about exquisite curation: the impeccable but not at all sterile store makes browsing new releases and pre-code films feel equally essential.

Vidéothèque impressed me with their extensive sections for international TV and harder-to-find American shows (like THE WONDER YEARS with the original music intact) as well as a massive music doc section that emphasized rare girl punk bootlegs, Mingus performances, and classical concerts with the same level of enthusiasm.

With some groovy shoegaze playing while I browsed, I hung out while a dozen or so customers came through the store on a Sunday afternoon. A father extolled the virtues of Ray Harryhausen to his middle-school son (who just wanted to rent SHIN GODZILLA again) while I perused Vidéothèque’s excellent avant-garde and experimental section. Documentaries were sorted by director and by subject — especially helpful for those seeking materials for research purposes.

Vidéothèque’s focus on international titles is quite impressive — thirty-year old VHS tapes were stacked alongside new Blu Rays, providing access to films that aren’t available on DVD or Blu Ray in the US. I also really appreciated how diverse Vidéothèque’s children’s section was, with documentaries and foreign films presented to children alongside Pokémon and THE LITTLE MERMAID — Vidéothèque understands that children become voracious watchers as adults if they’re shown a wide array of films as kids.

The Cult section at Vidéothèque

While the dual sorting of American films by both director and actor (depending on the genre and title) might feel confusing to some, I enjoyed being able to peruse filmographies of actors like Barbara Stanwyck and Sidney Poitier alongside directors like Allison Anders and Sam Fuller. It’s just so much easier to fall in love with an actor or director when their entire filmography is laid out in front of you, not just a few random titles.

Vidéothèque also sells vinyl, t-shirts, buttons, and new and used DVDs, further bolstering their role as an important gathering place for South Pasadena. Even after one visit, I could tell fostering and nurturing a sense of community was one of Vidéothèque’s core values — the store is an essential hub for film lovers on the east side.

Vidéothèque, 1020 Mission Street, South Pasadena, CA, 91030. 11AM-11PM weekly (10AM on Saturdays.) All rentals $4.50, with option to pre-purchase rentals in packages for a discounted rate.

The next two stores I visited most reminded me of the Blockbusters and Hollywood Videos of my childhood: Star Video in Van Nuys and Odyssey Video in North Hollywood. These stores are catered towards the more casual viewer — lots of new releases and popular catalogue titles.

Star Video

Star Video felt almost exactly like a Blockbuster to me: new releases lined the outer edge of the store, with older titles sorted by genre in the middle. While there wasn’t any curation to speak of, Star Video does feature some very deep genre sections, particularly for late 90s/early 2000s titles — some sections were so full that titles were stacked on top of each other.

Star’s most impressive racks include a massive selection of thrillers, and a funky children’s section with titles like MAD HOT BALLROOM and THE LEGEND OF NATTY GANN. They’re also the only store I visited that’s still renting video games — that market has been squashed by Gamefly, so Star Video is meeting an important need for those who would prefer to rent in-person.

I was the only person in Star Video on a Sunday afternoon, but if I lived closer, I’d be stopping in for new release titles on Blu Ray since they’re just $2.50 each — catalogue titles rent for only a dollar.

Odyssey Video

Odyssey Video gave me some intense 1997 vibes — in absolutely the best way. VHS tapes were shelved alongside DVDs, and I noticed a lot of forgotten 90s cable classics like THAT NIGHT, SHAG! and THERE GOES MY BABY were still renting at the store. I was most struck by some of the rare children’s titles at Odyssey, like compilations that never made it to DVD from ANIMANIACS, BATMAN: THE ANIMATED SERIES, and THE SIMPSONS.

Like Star, there’s no curation at Odyssey outside of genre, but the store featured an extensive martial arts section (with titles from the 1970s still available on VHS) and a deep musicals rack, including some out-of-print compilations from major studios.

And, while almost every store I visited had an adult section, Odyssey’s behind-the-curtain titles are truly something to behold: they take up almost half the store, with a smattering big-box pornos from the 1980s still available to rent. Odyssey felt like a store out of time and space, but that’s not a bad thing: a visit there feels like a voyage back in time. And the prices reflect the retro vibe of the store as well — most of Odyssey’s extensive VHS collection rents for just $.99 a movie.

Star Video, 13644 Vanowen, Van Nuys, CA, 91405. 10AM-11PM daily. $2.50 for new release rentals, $1 for catalogue titles.

Odyssey Video, 4810 Vineland Avenue, North Hollywood, CA, 91601. 10AM-12AM daily. $1.99 for rentals, $.99 certain days of the week.

Eddie Brandt’s Saturday Matinee

I found what I was looking for when I visited Eddie Brandt’s Saturday Matinee in North Hollywood.

I figured I was in good hands when I saw “Mount Rushmonster” painted on the outside of the nondescript building, but once I walked in and saw the one-sheets, movie magazines, scripts, and laserdiscs for sale, I knew I’d found the video store I’d been searching for — the vibe was just right.

Eddie Brandt’s rental floor houses 80,000 VHS tapes — twenty times the number of films now streaming on Netflix. While there, I slipped into that glorious zen state only a concentrated browse can provide — I could’ve easily posted up there for the rest of the day. Eddie Brandt’s has countless rare and out-of-print titles I’d never laid eyes on before like early commercials compilations, classic Western and detective serials, multi-part television documentaries, and so much more.

The scope of Eddie Brandt’s rental catalogue cannot be understated: only the VHS tapes are out on display, but the store also rents over 20,000 DVDs and Blu Rays, including the newest releases, available to scan via their catalogue. Titles at Eddie Brandt’s are alphabetized, but with a catalogue of that size, one opts for simplicity over curation— and don’t worry, the clerks behind the counter and your fellow customers will be happy to recommend things once you start talking about the kind of movies you like.

While I was browsing, I struck up a conversation with Tony Nittoli, who was working the counter, and two patrons — one an older gentlemen in a WWII veteran hat; the other a young metalhead carrying his chihuahua. I told them I was working on a piece about video stores, and all three of them were eager to tell me about Eddie Brandt’s history.

Nittoli mentioned that Paul Thomas Anderson and Quentin Tarantino are still customers — not at all surprising given that Anderson and Tarantino are some of the most film-literate directors working today. The older gentleman (a patron of many years who asked not to be named in this piece) told me that most of the major studios keep contracts with Eddie Brandt’s, as it still provides the easiest pathway to find very old and obscure titles from their own catalogues. The four of us chatted about how much we all missed this exact moment of the video store experience: just shooting the shit on a Friday afternoon, talking about movies without a care about anything happening outside the store’s VHS-packed walls.

The Westerns section at Eddie Brandt’s

I had such a great afternoon at Eddie Brandt’s that I went back a few Saturdays later — Nittoli remembered me and asked how my piece turned out. He also insisted I take a donut from the open box on the counter — all patrons were cajoled into taking one before leaving, adding to the family feel of the store.

Both times I visited Eddie Brandt’s, there were multiple groups browsing, and conversation flowed between customers and counter staff — everything from to why THE EXECUTIONER’S SONG had been checked out for so long to where to find obscure skateboarding videos to why studio movies were so bad in the 1980s.

And, I was able to find four movies — LITTLE DARLINGS, DIARY OF A MAD HOUSEWIFE, LOOKING FOR MR. GOODBAR, and PLAY IT AS LAYS — that will never make it to DVD (thanks to, you guessed it, music licensing issues) on VHS in Eddie Brandt’s collection, a thrilling moment for me after being on the hunt for many years. I talked to Nittoli about needing a VCR again after discovering all Eddie Brandt’s offered me, and he mentioned how much harder they’d been to come by in the last few years. Nittoli said that he’d noticed an uptick in customers asking about VCRs as they began to realize how many titles weren’t (and would never be) available on streaming or DVD/Blu Ray.

Eddie Brandt’s Saturday Matinee is the most impressive video store I’ve ever visited — I’m scouring Goodwills for a working VCR so I can start a membership in earnest. In addition to their massive one-of-a-kind catalogue, the warm, welcoming atmosphere at the store made me feel like a member of their community after only two visits.

And the sensual experience of visiting the store — the pleasant library musk of dust and cardboard, the murmur of a mystery movie on an old TV mixing with customer chatter, the feel of well-worn, embossed letters on a shaggy shell case — kept me engaged throughout both of my visits. I felt so much more invested in the films I was looking at — holding them in my hands made the stakes of choosing something feel so much higher than when on streaming.

In addition to one of the most impressive rental catalogues in North America, the store also houses twenty-two tons of promotional photos, film stills, posters, and other movie memorabilia — and you can browse their entire catalogue online.

Eddie Brandt’s Saturday Matinee is an essential haven for cinema’s true believers, and should be preserved and protected at all costs. Next time you’re in the Valley, stop by, and you’ll see exactly what I’m talking about.

Eddie Brandt’s Saturday Matinee, 5006 Vineland Ave., North Hollywood, CA. 1–6PM Tuesday-Friday, 10AM-6PM Saturdays. One-time membership fee of $15, all rentals $3.

Read more

Published on July 18, 2018 00:00

July 16, 2018

In Search of the Last Great Video Store

A few months back, I had a very specific movie craving — I wanted to watch FRESH HORSES, a 1988 romantic drama most notable for reteaming Molly Ringwald and Andrew McCarthy after PRETTY IN PINK. It was a grey, chilly day in LA, and I was feeling nostalgic for spring in my hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio — FRESH HORSES was shot there. I was hoping I could capture some of the misty, late March vibes the movie evokes so well, and in doing so, take a cinematic field trip back home for a few hours.

So, I did what I usually do when looking for a movie in the year 2018: googled “FRESH HORSES streaming.” No results, not even for rental. So, I moved on to less legal methods, beginning with YouTube. After that failed, I pulled a maneuver I’ve been using for a decade: googling multiple variations of “watch FRESH HORSES online.” Even then, the best version of the movie I could find was a Polish dub.

FRESH HORSES isn’t a great movie, but that’s besides the point. Ben Stiller and Viggo Mortensen star alongside Ringwald and McCarthy, and the movie is only thirty years old — it should be available online with a few clicks. I definitely would’ve paid a few bucks to rent it via Amazon or Vudu, but those options weren’t available to me.

Why was it so difficult to stream or rent a thirty-year old movie with four major stars?

I remembered the last time I’d watched FRESH HORSES: I’d rented it from my local Blockbuster in Sharonville, Ohio as a teenager. Had there still been a Blockbuster (or any other video store) in my neighborhood, I would’ve jumped in the car, rented the movie, and been home in an hour. Instead, I had to settle for buying FRESH HORSES in a six-movie collection off of Amazon, which would come three days later.

But by then, the amorphous melancholy that inspired me to watch the movie in the first place had passed. Because I couldn’t access FRESH HORSES, I felt like I couldn’t fully process the restless nostalgia that spring always brings for me.

We all have our own FRESH HORSES: movies that transport us back to a specific location, time, and mood that only exists otherwise in the haziness of our own memories. When we can’t access these kinds of movies, it feels as if an essential pathway that connects us to our pasts — and our past selves — is lost too.

I think about the problems of how we watch movies now and “dead media” every day — and I have a house full of vinyl, VHS tapes, and Nintendo 64 games to prove it. I’ve been blessed (and cursed) by the collector gene — part of my drive to collect stems from an aesthetic appreciation, but there’s another more practical reason for my collecting too.

Whether it’s a twenty-five year old cassette of a WOXY radio broadcast or a permanently out-of-print Stephen King collection, I hold onto these physical objects because I know one day they just won’t be available elsewhere. Given the extremely fickle nature of online availability, I’m the rare person who’s doubled-down on physical media in the last few years: I sleep better at night knowing that my out-of-print DVD of GAS FOOD LODGING is tucked away on a shelf.

I’ve skipped out on a number of disc releases for films like POSSESSION (1981) and LADIES AND GENTLEMEN THE FABULOUS STAINS in the last few years, and those editions now go for around fifty bucks each. Sure, I can rent STAINS or buy it for the cloud, but who can say how long those options will remain available to me? And POSSESSION isn’t currently available anywhere to stream or buy online — it can be rented from MUBI, but for how long?

We all like to assume that the movies and television shows we love will be available with a click whenever we want them — one can now buy an Amazon button for Doritos, after all — but the stability of what media is available online (and how long it stays there) is quite tenuous. “You are not in control of what you have access to — you are picking from a small library that’s always rotating,” says Maggie Mackay, Board Chair and Executive Director of Vidiots.

Streaming Killed the (Chain) Video Store

“Once a video store owns a title, they have it for years, regardless of if it goes out of print or if the film’s rights holder goes out of business or sells their catalogue to another studio or service.” — Eric Allen Hatch

At the company’s peak in 2004, there were 9,000 Blockbusters operating in North America — today, only three remain open in Alaska. When Movie Gallery began to see a slump in sales in 2007, they were operating more than 4,500 locations in North America (including Hollywood Video, which they acquired in 2005 after an attempt at a hostile takeover from Blockbuster.) Movie Gallery filed for bankruptcy in 2010 — like Blockbuster, only three independently franchised locations remain open in Arkansas.

Rentrak estimates that 19,000 video stores were open across America during the industry’s peak. In December 2017, 24/7 Wall St. reported that 86% of the 15,300 video stores that were open in 2007 had closed, and the industry had lost more than 89% of its workforce, making video tape and disc rental the “top dying industry” in America.

Global chains like Rogers Plus, Video Ezy ,and Xtra-vision have folded as well, though Video Ezy still operates rental kiosks like Redbox. Only a few international chains — Le SuperClub Videotron in Canada, Culture Convenience Club in Japan, Civic Video in New Zealand and Australia — remain open.

Over five billion rentals have come through 40,000 Redbox kiosks since the company’s launch in 2002 — they now control 51% of the physical rental market in the US. But even the biggest Redbox machine only holds around 600 discs, covering up to 200 titles — no match for even a tiny video store.

...The idea that beloved, superlative films like CASABLANCA and CITIZEN KANE can only be accessed with a subscription to an arthouse/classic focused streaming service is quite frankly insane. THE GODFATHER trilogy is now available on Netflix, but that’s only been the case since January of 2018. Even something as ubiquitous as STAR WARS is only available in its first, unedited iteration as a VHS box set from 1995 — and the original trilogy isn’t currently streaming anywhere.

And of course, most major streaming platforms are deep into the original content game. Netflix has released 25 original films and added 7.4 million new subscribers thus far in 2018 — that’s as many releases as the six major studios combined. They plan to release 80 films by the end of the year. The focus on new content creation over the preservation of and access to catalogue titles for most streaming services is quite clear.

...How will we create new movie lovers when we’ve taken away one of the easiest entry points to learning about and loving film? When so few classic films are available to stream? When no one offers them a guide of how to understand cinema’s history? How do we assure that most films, even something like FRESH HORSES, are available to anyone who wants to watch them? What happens to Hollywood history when films aren’t being protected, preserved, and well-presented as we jump to each new technological platform?

These questions keep me up at night, and keep me worried about what the future of home-viewing (and the next generation of film fans) looks like.

So for me, there’s only one solution: we have to go in search of the last great video store.

Read more

Published on July 16, 2018 00:00

July 14, 2018

Film Courage: Three Biggest Mistakes New Screenwriters Make by Dr. Ken Atchity

RESPECT THE AUDIENCE!

Published on July 14, 2018 00:00

July 12, 2018

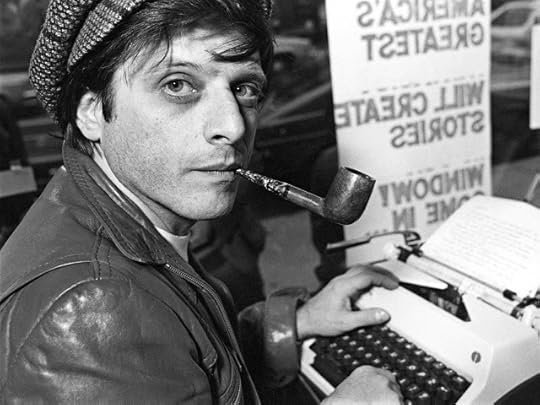

In Memoriam Harlan Ellison

Harlan Ellison in Boston in 1977. He looked at storytelling as a “holy chore,” which he pursued zealously for more than 60 years. CreditBarbara Alper/Getty Images

I only got to meet Harlan two or three times, and since it was in my position of VP for Los Angeles PEN it was somehow always antagonistic (by his selection, of course). He tried to shout me down when I was announcing something or other. I told him, Why don’t you stand up and defend yourself like the writer that you are instead of just interrupting obnoxiously. He jumped to his feet, stated his case, then sat down. And grinned. It gave me a good feeling.

I loved reading his words, but none more than what he sent me one day when I asked him what he did with “cranks & weirdos” he must deal with even more than I did as an editor. He sent me a mimeographed statement he sent to them, that went substantially like this:

SOME PRETERNATURALLY IMBECILIC ASSHOLE, USING YOUR NAME, SENT ME THE ENCLOSED PIECE OF SHIT USING THE UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE AND I AM RETURNING IT TO YOU HEREWITH IN THE KNOWLEDGE THAT YOU WILL NEED IT AS EVIDENCE WHEN YOU FILE A FEDERAL CASE AGAINST THE MORONIC FUCKER. GOOD LUCK WITH THAT!

Being a professor at the time, I didn’t have the balls to actually use it, but I never failed to think about it when I opened a crank missive. If only I could adopt it to email today!

R.I.P., Ellison. You rocked!

Read New York Times Obituary

Published on July 12, 2018 00:00