Kenneth Atchity's Blog, page 102

February 17, 2019

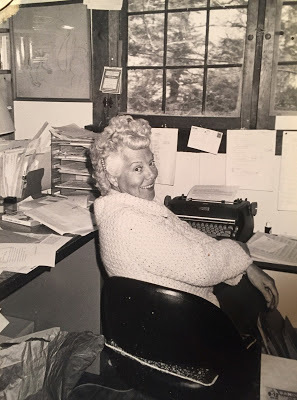

Betty Ballantine, Who Helped Introduce Paperbacks, Dies at 99

Betty Ballantine, who with her husband helped transform reading habits in the pre-internet age by introducing inexpensive paperback books to Americans, died on Tuesday in Bearsville, N.Y. She was 99.

Betty and Ian Ballantine established the American division of the paperback house Penguin Books in 1939. They later founded Bantam Books and then Ballantine Books, both of which are now part of Penguin Random House.

In those early years the challenge for purveyors of high quality, inexpensive paperbacks was enormous. At the time, Americans mainly read magazines or took out books from libraries; there were only about 1,500 bookstores in the entire country, according to the Ballantines, who wrote about the origins of their business in The New York Times in 1989.

With a $500 wedding dowry from Ms. Ballantine’s father, the couple established Penguin U.S.A. by importing British editions of Penguin paperbacks, starting with “The Invisible Man” by H. G. Wells and “My Man Jeeves” by P. G. Wodehouse.

They were not alone in seeing the potential of the paperback market in the United States. Pocket Books had just started publishing quality paperbacks, breaking in with Emily Brontë’s “Wuthering Heights” and James Hilton’s “Lost Horizon.”

Both companies charged just 25 cents per book, making books easily affordable for people unable or unwilling to pay for hardcover books, which cost $2 to $3 each (about $45 in today’s money). And they overcame the distribution problem by making books available almost everywhere, including in department stores and gas stations and at newsstands and train stations.

The paper shortage during World War II put a crimp in the business, but that was temporary.

In short order, paperback books were flying off the racks and shelves, with readers able to buy two or three at once and more companies starting to publish them. The Ballantines were making good on Ian Ballantine’s stated goal: “To change the reading habits of America.”

They left Penguin in 1945 to start Bantam Books, a reprint house. Having purchased the paperback rights for 20 hardcovers, their first round of titles included Mark Twain’s “Life on the Mississippi,” John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby.”

They started Ballantine Books in 1952, publishing reprints as well as original works in paperback.

While Ian Ballantine, who died in 1995, was the better known of the publishing duo, Betty Ballantine, who was British, quietly devoted herself to the editorial side. She nurtured authors, edited manuscripts and helped promote certain genres — Westerns, mysteries, romance novels and, perhaps most significantly, science fiction and fantasy.

Her love for that genre and knowledge of it helped put it on the map.

“She birthed the science fiction novel,” said Tad Wise, a nephew of Ms. Ballantine’s by marriage. With the help of Frederik Pohl, a science fiction writer, editor and agent, Mr. Wise said, “She sought out the pulp writers of science fiction who were writing for magazines and said she wanted them to write novels, and she would publish them.”

In doing so she helped a wave of science fiction and fantasy writers emerge. They included Joanna Russ, author of “The Female Man” (1975), a landmark novel of feminist science fiction, and Samuel R. Delany, whose “Dhalgren” (1975) was one of the best-selling science fiction novels of its time.

The Ballantines also published paperback fiction by Ray Bradbury, whose books include “The Martian Chronicles” and “Fahrenheit 451”; Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote “2001: A Space Odyssey”; and J.R.R. Tolkien, author of “The Hobbit” and the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy.

“Betty was succinct and to the point and had a steely eye and was a respected editor,” Irwyn Applebaum, the former president and publisher of the Bantam Dell Publishing Group, now part of Penguin Random House, said in a telephone interview.

“Most people who knew the Ballantines would say that much of the editorial vision and brilliance, from variety to quality, that Bantam and Ballantine were known for were due to Betty,” Mr. Applebaum said. “Ian was the proselytizer for their brand of books, but Betty was the identifier, the nurturer, the editor.”

Elizabeth Norah Jones was born on Sept. 25, 1919, in Faizabad, India, during the British rule on the subcontinent. She was the youngest of four children of Norah and Hubert Arnold Jones.

Sign up for Breaking News

Sign up to receive an email from The New York Times as soon as important news breaks around the world.

Her father was an assistant opium agent who oversaw quality control of the crop before it was exported to Britain, where it was used for medicinal purposes. He often traveled to remote farms to inspect crops and would take along his family, who would live in tents with full linen and silver service, Ms. Ballantine, Betty’s granddaughter, said in an email.

Betty learned to read at 3 by following her father’s finger as he read aloud. At 8 she was sent to school in Mussoorie, in northern India in the foothills of the Himalayas, where the heat was less stifling than at home.

When she was 13, the family moved to the British island of Jersey in the English Channel, where she completed high school. She did not attend college; instead she took a job as a bank teller on Jersey, where she met Ian Ballantine, an American. They were married in 1939 and sailed for New York.

After building Ballantine, the couple sold the business to Random House in 1974, at which point Mr. Ballantine returned to Bantam in an emeritus status and Ms. Ballantine continued to work with authors, including the pilot Chuck Yeager and the actress Shirley MacLaine. The couple also published art books through their Rufus Publications.

Over time Ms. Ballantine earned a reputation as a shrewd and insightful editor.

“She was very traditional, and she put authors through their paces,” said Stuart Applebaum, a longtime publishing executive with Penguin Random House and the brother of Irwyn. “She understood that her job was to make the author’s work as good as it could be — in the author’s own words.”

Read more

Published on February 17, 2019 12:06

How The MEG Should Have Ended

How It Should Have Ended has released its latest fun take on Jason Statham's shark-hunting adventures in The Meg Movie!

Clocking in at just under three minutes, the clip runs through the various ways Statham's team could have and should have killed the shark.

Clocking in at just under three minutes, the clip runs through the various ways Statham's team could have and should have killed the shark.

Published on February 17, 2019 00:00

February 15, 2019

You made a movie. Now what?

1. Making a good film isn’t enough.

Congrats! You made a good film. Sorry to say, that isn’t enough. “Of course, we want good films, but we are looking for a combination of elements that make it really stand out and give it a clear path to market. Having a film selected by a prestige festival gives a film an obvious path to market That’s part of the role of festivals, sales agents, marketing professionals and entertainment attorneys.” That said, sometimes films off the beaten track find their way to audiences. Just to say ‘it’s a good film’ is almost a meaningless description at this point. It’s totally subjective. If it's an advocacy documentary, is there a core audience or organizational value that will bring people out who will, in effect, vote their politics by buying a movie ticket? With a narrative film, there should be some approach to genre that makes it stand out stylistically. How is it unique?"

2. Determine your goals.

Before you set out to make your film, decide what your distribution goals are. “It’s really important to think about who you’re making the movie for and familiarize yourself with the marketplace. Do you care how your film is seen? On the big screen or at home? Socially or in isolation? Do you want a small, rabid group of people to see and love it or would you rather reach as many people as possible regardless of whether or not they appreciate it? Do you want to persuade a group of people to change their minds about an issue, or preach to your choir? Any and all of these are worthy goals in my view. It’s just important to decide upfront what’s important to you and then align your collaborators (and budget) accordingly. What are the goals and what do we want to accomplish? For most filmmakers, she said “the goals are to reach as wide an audience as possible, to pay back investors and to be in the position of making another film. When you're working with a distributor the goal is going to be money for the most part, but some want prestige or an awards campaign or visibility. When it comes to making those decisions, it's important that filmmakers have a holistic view and what are the sacrifices you're willing to make. If you want visibility, that may stand in the way of making money.

3. It’s never too early to start thinking about your distribution strategy.

Filmmakers should be considering festival and distribution strategy before they shoot. What kind of film are you making?

There are other steps filmmakers can take in pre-production that could benefit them when it’s time to seek distribution. “What can you do to enhance the marketability of your film? Maybe find someone with a social media following and put them in your film. During production, in addition to hiring a photographer to take set photos, you might consider additional original content that will help with marketing.

Research the market and develop a plan early in the process. Know what movies like yours have been doing in the market for the last five years and have a plan that you put in place before you start shooting. Distribution is work and time and planning and some money and it’s not going to be done for you. You don’t have a God-given right to make a movie and have it distributed, so be prepared for that not to happen and have a game plan.”

5. There is no “one size fits all” in distribution.

One film might benefit from a grassroots campaign with live events and another might do better going directly to VOD. Distribution is a strategy, not a formula.What works for a horror film is not necessarily going to work the same as a romantic comedy. Bbuild distribution campaigns that are specific to the film. Each film follows a unique path to distribution and it's up to the filmmaker to lead the way. Filmmakers have to understand that every film is different.The new equation is 50/50. 50 percent of your time, money and resources should go into making the film and 50% should go to connecting your film to an audience.

Read more

Published on February 15, 2019 00:00

February 13, 2019

Russell Baker on Writing...

“The only thing I was fit for was to be a writer, and this notion rested solely on my suspicion that I would never be fit for real work, and that writing didn't require any.”

“The only thing I was fit for was to be a writer, and this notion rested solely on my suspicion that I would never be fit for real work, and that writing didn't require any.” ~ Russell Baker

Published on February 13, 2019 00:00

February 12, 2019

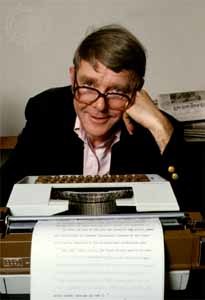

R.I.P. RUSSELL BAKER 1925-2019

Russell Baker (You might recognize his face if you watched Masterpiece Theater on PBS) died in January a few days after my birthday, and I recall with fond nostalgia our lunch at the New York City Yale Club about the same time in 1984--some months after The Los Angeles Times Book Review nominated his Growing Up for its Biography Award and asked me to do the write-up:

We share a gentler world in Russell Baker’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Growing Up (Congdon & Weed: $15, hardcover; Plume: $5.95, paperback), a book that casts the spell of honesty on narcissism and turns it into sweet nostalgia. Baker frames his autobiography with the recent death of his mother: “It was useless now to ask for help from my mother. The orbits of her mind rarely touched present interrogators for more than a moment.”

His father died when he was five, and his memories of the wake have that family vividness that makes us realize how our memories are formed, “‘Do you want to kiss you daddy?’ Annie asked, ‘Not now,’ I said.”

Interwoven with gossip, insight and deeply moving letters from his mother’s Depression suitor, the texture of Baker’s reminiscence transforms deferred pain to present poignancy. We end at his mother’s deathbed: “Her eyelids closed again. ‘You remember Russell,’ I said. ‘And Mimi. You remember Mimi.’ Her mind seemed about to surface again. She got her eyes open.

‘Who?” ‘Russell,’ I said. ‘Russell and Mimi.’ She glared at me the way I had so often seen her glare at a dolt. ‘Never heard of them,’ she said, and fell asleep.”

The life of a human being is a million moments of action. Character is decision, a signpost along the way. Biographers serve us by revealing how human beings design for themselves the characteristic force that gives life meaning. They offer models for emulation or avoidance…

He’d written to thank me for the review, and I suggested the lunch because I’d considered him a mentor in my journalism career. During lunch we discovered dozens of what my friend the late Denise Levertov called “Interweavings,” those connections discovered only when human beings actually sit down to talk about nothing in particular, just life in general. If I recall, we talked about the creative energy caused by deadlines and word-count restrictions, Richard Nixon, and solitude vs loneliness. I walked out feeling exalted by being in the presence of a fully engaged human being. Even today I savor trips to New York, one of the cities, other than in my native South, where just plain talking is still considered the best that it gets and where many of this country’s just plain good talkers like Russell hang out.

He made it to 93, died of “complications from a fall,” as so many do, including my brother Fred this past July.

I’m sorry I can’t report massive insights from the lunch. What I can report is the gentleness of spirit that informed his writing and his life, and that made me want the genial conversation to go on forever. And so it will.

Published on February 12, 2019 09:52

February 11, 2019

Congratulations to our friend and colleague Nancy Nigrosh who Joins The Partos Company To Head Motion Picture & TV Division!

Nancy Nigrosh, the industry veteran who has worked repping directors and writers as a talent and literary agent at Innovative Artists and running the lit department at Gersh, has joined The Partos Company. She has been tapped to head the Motion Picture & Television department at the Santa Monica-based agency, which is known for its representation of artists behind the camera.

Nigrosh previously ran the consulting firm Literary Business and taught at UCLA Extension’s Writers’ Program. During her career she has repped clients including helmers Kathryn Bigelow, Peter Bogdanovich, Chris Eyre, John Cameron Mitchell and Leslye Headland and scribes Barry Morrow, Amanda Brown, Luke Davies, Albert Magnoli and Stuart Beattie.

Partos, run by Walter Partos, reps clients including costume designers Albert Wolsky (Bugsy), Natalie O’Brien (Honey Boy) and Heidi Bivens (Mid90s); cinematographers Scott Cunningham (Kendrik Lamar’s “Humble”) and Maxime Alexandre; and producer Hartley Gorenstein (The Boys).

“Every agency has the same information, knows the same people and pursues the same projects,” Partos said. “Nancy has an incredible eye for material and, at the end of the day, choosing the right material is the difference between a great career and a good one. It is an honor to collaborate with her.”

Read more

Published on February 11, 2019 00:00

How The MEG Should Have Ended

How It Should Have Ended has released its latest fun take on Jason Statham's shark-hunting adventures in The Meg Movie!

Clocking in at just under three minutes, the clip runs through the various ways Statham's team could have and should have killed the shark.

Clocking in at just under three minutes, the clip runs through the various ways Statham's team could have and should have killed the shark.

Published on February 11, 2019 00:00

February 8, 2019

Fall in Love With Time...

Film Courage: One of your many books Ken is WRITE TIME? And in the forward you say that the world can be divided into two people, productive people and non-productive people. And you say that productive people have a love affair with time. I’ve love to know what makes someone on the right side of time and what make someone where time is their enemy?

Dr. Ken Atchity, Author/Producer: Well that’s a very good question put in a very intelligent way that makes it hard to get a handle on it because time is…time doesn’t really exist. Time is a human construct, we created time. Squirrels and chipmunks don’t have much idea of time. They know that the sun rises and the sun goes down and they know that it rains but they don’t think the way that we do and they don’t keep track of their birthdays for example, only humans do that. And it’s unfortunate because you’re only as old as you think you are. And that’s the way a squirrel looks at it and nobody is arguing with the squirrel about it but humans know better.

Some people look at time as the enemy and some people look at it as a friend. There is an old Spanish saying that is “There is more time than life,” which I always thought was a wonderful way of looking at it because that is what a productive person would say “there is more time than life.” And another Spanish or Italian saying says that “Life is short, but wide.” And that’s another way of productively looking at it. Like people say “How can you do as much stuff as you do?” Well that’s because that’s what I do. I don’t do anything else. And I used to give classes on time management and do a lot of studies on it, in fact WRITE TIME is filled with time management theories. And one of the things I noticed about people was they had no idea where their time went. And they go “I don’t know where you find all the time.” And I would say “I don’t know where you lose it.”

I mean we all have the same amount of time and they go “How much time do we have by the way? How much time is in a week?” And 2 out of 10 people can ask the question right off the top of their heads because they’ve never really multiplied 25 by 7 and realized exactly how many hours there are in a week.

Everybody has the same amount of time. So what I would do in a time management class at UCLA or elsewhere is I would say let’s chart your time this week. I just want you to make a chart of what you do with your time and let’s come in and talk about it next week when we come back together. And they would come back in and that was before I asked them how many hours there were in a week I would wait for the third week to ask that question.

And some people would come in with 98-hour weeks and some people would come in with 62-hour weeks and nobody seem to agree in general how many hours there were in a week because the hours they gave me didn’t add up, they didn’t make sense. They’d say “I sleep six hours a day.” But it turned out in the third week of analysis that instead of 6 hours a day they were actually sleeping 10 hours. They just were telling themselves they were sleeping 6 hours a day.

How much time do you spend talking on the telephone? Most people thought they maybe spent 15 minutes a day, when in fact it might be an hour a day. And watching television (of course). Some people said they were only watching an hour a day when they were actually watching three hours a day.

But a productive person knows exactly how long it takes to do something. Like when I write a screenplay or a book, I can tell you how many hours it takes to do it and so I know that I can get it done in a certain amount of time. Agatha Christie apparently wrote as many as 10 books a year. She had to use four or five pen names because she just kept writing. When you think about it writing is a function of how fast you type. Because I always say (in my writing book including that one) if you’re making a rule not to sit down to write if you don’t know what you’re going to write then you’ll never waste any time and you’ll never have writer’s block. So simply don’t sit down until you know what you’re going to write. It’s just a matter of how fast can you type. So it’s better to be walking along the beach thinking about the structure of your story then it is to be wasting a lot of time sitting in front of the computer typing stuff and throwing it away and all that stuff. Just figure it all out in your head. “Well what if I forget it?” Well guess what? If you forget it that’s probably good. You are forgetting forgettable things? You won’t forget it when it starts getting really good. Because then it will do what Faulkner said, it will start haunting you and you won’t be able to forget it and then you’ll just write it down.

William Saroyan was asked once how long it took him to write the Human Comedy because somebody had told the journalist it had took him three days and he said “No, it took me all my life to write it. It just took me a few days to type it out.”

Published on February 08, 2019 00:00

February 5, 2019

How To Book Meetings With Studio Heads And Get Into The Story Market - Dr. Ken Atchity With Alex Berman

With more than forty years’ experience in the publishing world, and twenty-five years in entertainment, Dr. Ken Atchity is a self-defined “Story Merchant” – author, professor, producer, career coach, teacher, and literary manager, responsible for launching dozens of books and films. Ken’s life passion is finding great storytellers and turning them into commercial authors and screenwriters.

In this episode you’ll learn:

[01:14] Dr. Ken’s first deal was for 8 movies

[05:25] No one knows anything in Hollywood [06:14] Entertainment business is based on wild ideas

[06:36] What stops someone from thinking outside the box

[08:40] It took 22 years for Meg to get to the screen

[12:13] Story market is very volatile

[15:14] How is Dr. Ken setting up the meetings with studio heads

[17:55] How to stay memorable

[19:50] Pitching is an art

[23:00] Difference between amateur and veteran pitching

[23:55] What makes for a good film story

[28:55] It’s hard to get in the story market at a national level

Brought to you by Experiment 27. Find them on Youtube.If you’ve enjoyed the episode, please subscribe to The Alex Berman Podcast on iTunes and leave us a 5-star review.

Published on February 05, 2019 00:00

February 3, 2019

Let me help you make your career take off!

Whether you're a novelist seeking to break into publishing or film, a screenwriter seeking to be discovered in a volatile marketplace, an expert in your field ready for the global stage, or a published author in need of a smarter strategy, Story Merchant Dr. Ken Atchity provides dynamic personally-tailored coaching (and representation, in select cases) to take your career to the next level.

Visit www.StoryMerchant.com

Visit www.StoryMerchant.com

Published on February 03, 2019 00:00